Abstract

Objectives

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) has accumulated increasing evidence-base for a broad range of mental health issues. Considering that ACT encourages broad and flexible patterns of behaviour and neutralizes the pervasive psychological processes proposed to be caused by most individuals' distress, such a modality may be effective for ADHD. This review aimed to give a synthesis of the studies, so far, focusing on the usefulness of ACT approaches among individuals having ADHD.

Design/Methods

This scoping review searched studies exploring the effectiveness of ACT approaches for individuals with ADHD across eight electronic databases (Medline, Embase, PsycInfo, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Emcare, Scopus, and Google Scholar). This review was based on a total of two quasi-experimental and four experimental studies.

Results

A thematic analysis was suggested based on the PRISMA guidelines. Overall, the review presented preliminary evidence demonstrating the use of ACT among individuals with ADHD. It was found that the ACT was used to treat a variety of behavioural and psychosocial outcomes, which included reducing ADHD symptoms (e.g., impulsivity, inattention, inflexibility, etc.) and other sequelae related to the ADHD diagnosis such as poor quality of life, academic procrastination, depression and anxiety symptoms, and psychological maladjustment.

Conclusions

This review revealed that ACT was a flexible approach that could be adapted to deliver both targeted treatment of ADHD symptomatology and more general psychosocial issues. It could also be delivered in group or individual formats. Nevertheless, although the findings of the present scoping review indicate promising results, more research is needed.

Keywords: Acceptance and commitment therapy, Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Psychosocial treatment, Scoping review

Acceptance and commitment therapy; attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; psychosocial treatment; Scoping review

1. Introduction

The roots of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), frequently termed as a third wave psychotherapy can be located in functional contextualism (Hayes, 2004), relational frame theory (Hayes et al., 2001) as well as in the Applied Behavioural Analysis (ABA) (Byrne et al., 2020). Despite substantial differences between the ACT and other traditional therapies for instance, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), ACT considers the role as well as context of psychological experiences (Blackledge et al., 2009). The nurturing of psychological flexibility is assisted through focusing on six processes in mindfulness, acceptance, defusion, self-as-context, committed action, and values (Luoma et al., 2007).

Various reviews have assessed the usefulness of ACT in managing various mental health problems in individuals ranging from chronic pain (Graham et al., 2016), imprisoned people battling aggression (Byrne and Ghráda, 2019), and to parents of children with various psychological and physical symptoms (Byrne et al., 2020). Despite methodological limitations in various studies assessing the efficacy of ACT (Öst, 2014), meta-analytical and systematic reviews have steadily demonstrated the effectiveness of ACT over control groups (A-tjak et al., 2015; Hayes et al., 2006; Öst, 2008; Swain et al., 2013).

1.1. Why might ACT have utility for individuals with ADHD?

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a neurodevelopmental disorder has a elevated worldwide occurrence ranging from 2% to 7%, averaging around 5% (Polanczyk et al., 2007). ADHD is distinguished by intense and impairing problems of inattention, impatient overactivity, as well as poor impulse control (Tosto et al., 2015). The International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10; WHO, 1993) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5; APA, 2013a, APA, 2013b) are extensively utilized to diagnose individuals having ADHD. The same 18 symptoms criteria is mentioned in the ICD-10 and DSM-5 based on two major areas; inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive behaviours. The problems persist throughout the growth of person majorly impact the adaptive functioning. Various people are recognised by the DSM criteria, involving persons depicting primarily symptoms of inattentiveness and late age of occurrence. There are three clinical presentations of ADHD based on predominant characteristics: primarily inattentive (ADHD-I), primarily hyperactive-impulsive (ADHD-H), and combined (ADHD-C) type (APA, 2013a, APA, 2013b). However, despite these primary presentations, ADHD is extremely diverse and linked to various deficiencies involving mental and behavioural limitations (Tosto et al., 2015).

Usually, a variety of treatment modalities are used to manage symptoms of ADHD (Conners, 2002; Sayal et al., 2018). In this regard, considerable studies have recognized the short-term use of stimulant medication and are proposed as main treatment among children and adolescents, particularly for more severe cases (Conners, 2002; Faraone et al., 2006; Pliszka and Issues, 2007). For instance, the American Academy of Paediatrics recommendations strongly support the stimulant medications for elementary- and adolescent-aged children with ADHD (AAP, 2011). Recent findings have shown the superiority of behavioural therapies employed with stimulants, compared to the use of stimulants or behavioural therapy alone (Catalá-López et al., 2017). Nevertheless, utility of cognitive-based therapies (CBTs) such as the ACT for ADHD is ambiguous and understudied, and this is also manifested in professional guideline suggestions (Faraone et al., 2006).

Adaptations of ACT are performed for persons with anxiety as well as depressive disorders (Bai et al., 2020; Eifert and Forsyth, 2005; Zettle, 2007). In this regard, experimental studies have demonstrated usefulness of ACT for anxiety and depressive disorders (Bai et al., 2020; Bond and Bunce, 2000; Forman et al., 2007; Kelson et al., 2019; Lappalainen et al., 2007; Twohig and Levin, 2017; Zettle and Hayes, 1986), physical health issues (González-Fernández and Fernández-Rodríguez, 2019; Gregg et al., 2007; Taheri et al., 2020; Vowles et al., 2007), other mental health issues (Gaudiano and Herbert, 2006; Gratz and Gunderson, 2006), and neurodevelopmental disorders particularly among children autism spectrum disorders (Byrne et al., 2020; Pahnke et al., 2019).

ACT favors a wide and flexible array of behaviors and neutralizing psychological practices speculated to be accountable for much of the individuals’ suffering, and as such may be superior to more traditional behavioral practices. The present review, based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009) standards, offers an overall review of the studies focusing on the usefulness of ACT approaches for individuals with ADHD. The present study is deliberately wide as ACT is called a transdiagnostic model that tackles multiple problems (Dindo et al., 2017). The disparate literature will be searched and analysed to assist clinicians in assessing the application of these approaches with people having ADHD.

1.2. Review question

The present review aims to tackle this question: Is acceptance and commitment therapy useful and effective in the treatment of individuals with ADHD? Based on suggestions of Schardt et al. (2007), this question can be depicted as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Review question classified based on the PICO(R) mnemonic.

| P | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| I | ACT |

| C | Ø |

| O | Symptom alleviation |

| R | Quantitative, qualitative, correspondences, case report, letter to editors, and mixed-methods |

ACT—acceptance and commitment therapy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Methodological approach

This scoping review was conducted following the guidelines of the Joanna Briggs Institute (Peters et al., 2015). This method was used as it required a replicable database search with no the requirement for a stringent question, which would have been contradictory with the present dearth of literature (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005; Mays et al., 2001; Weeks et al., 2019). This review is called scoping review as it swiftly and comprehensively evaluates research studies on the area of interest. Scoping reviews are aimed to spontaneously investigate the main concepts in specific field and to analyse the existing main sources and findings (Mays et al., 2001). Scoping and systematic reviews differ due to the former's exploratory nature and broader inclusion criterion (Mason & O'rinn, 2014).

2.2. Quality assessment

As a formal quality appraisal is not usually conducted in scoping reviews (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005; Munawar et al., 2020; Peters et al., 2015; Pham et al., 2014), hence, quality appraisal of the short-listed studies was not conducted in this review. Nevertheless, efforts were made to discuss the methodological and clinical limitations in the discussion section.

2.3. Information sources and search strategy

To reduce the publication bias, one author (KM) independently searched and extracted relevant literature from eight electronic databases, Medline, Embase, PsycInfo, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Emcare, Scopus, and Google Scholar (from inception to January 2021). Nevertheless, the publication bias was not visually assessed through funnel plot, Egger's test of funnel plot asymmetry or sensitivity analysis to exclude studies with high risk of bias owing to restricted access to statistical data of the included studies.

Specific filters were used for Medline and Embase and applied adaptations of these to the other databases. Moreover, the reference lists of retrieved publications and reviews were manually searched. Using the Boolean operators, truncation, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms as well as wildcard features suitable for each database's indexing reference (Dinet et al., 2004), synonymic keywords were also explored in all databases (see Table 2: Showing search terms). The MeSH thesaurus is a hierarchically organized vocabulary created by the National Library of Medicine, to record and list health-related literature (MeSH, 2019). The search terms were designed through past research and theory. Forward and backwards searching of the reference lists of all short-listed studies was also performed. The suitable references were subsequently exported to the EndNote reference management software (Endnote X9, Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, U.S.A.).

Table 2.

Showing search terms.

| Concept 1: ADHD |

|---|

| ADHD OR adhd OR attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity OR syndrome hyperkinetic OR hyperkinetic syndrome OR hyperactivity disorder OR hyperactive child syndrome OR childhood hyperkinetic syndrome OR attention deficit hyperactivity disorders OR attention deficit hyperactivity disorder OR attention deficit hyperactivity disorder OR addh OR overactive child syndrome OR attention deficit hyperkinetic disorder OR hyperkinetic disorder OR attention deficit disorder hyperactivity OR child attention deficit disorder OR hyperkinetic syndromes OR syndromes hyperkinetic OR hyperkinetic syndrome childhood |

| AND |

| Concept 2: ACT |

| ACT∗ OR acceptance and commitment therapy |

2.4. Study selection

The articles were screened based on the inclusion criteria shown in Table 3. The quantitative, qualitative, correspondences, case report, letter to editors, and mixed-methods studies in the English language were included. Moreover, to guarantee that the review was comprehensive, all empirical research designs were included. Summaries, discussion papers, book chapters and literature reviews were excluded but used to recognize additional articles not found in the original search.

Table 3.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria |

| 1. Articles needed to report on empirical data obtained from ACT treatment on individuals having ADHD. 2. Published studies that used ACT or a combination of ACT and other therapies. 3. ACT treatment based on at least 2 of the 6 core ACT processes: acceptance, contact with the present moment, cognitive defusion, self-as-context, values, and committed action. 4. Studies that specifically focused on individuals having ADHD. 5. Studies that had at least one outcome measure to assess effectiveness of intervention. 6. Studies that were based on quantitative, qualitative, correspondences, case report, letter to editors, and mixed-methods. 7. Studies completed in English. |

| Exclusion criteria |

| 1. Summaries, discussion papers, book chapters and literature reviews 2. Studies published in languages other than English. 3. Did not clearly use ACT techniques. |

Studies were reviewed according to title and abstract. The full-texts of all the short-listed articles were subsequently screened by two authors (KM and FRC) autonomously. The causes of excluding the full-texts articles were considered and discrepancies were settled unanimously. No limit was set regarding publication year or study size.

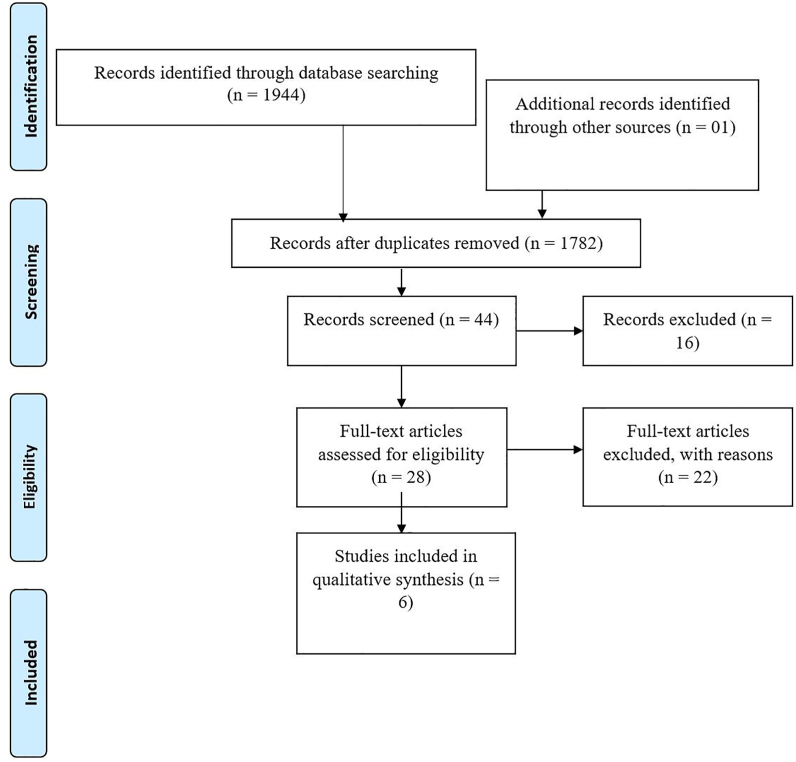

Figure 1 depicts the flow chart for this review. After deleting duplicates, an initial scrutiny of the databases returned 1782 articles published in English-language. One of the authors (KM) short-listed the titles and abstracts. This resulted in 44 potentially related studies. No articles were identified by manually exploring the reference lists of articles. Next, each study was examined full-length, and this stage retained 6 appropriate papers for inclusion. The entire process was repeated independently by another author (FRC) and disagreements were settled through mutual discussion (See Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram showing the process of study selection for inclusion in the scoping review).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing the process of study selection for inclusion in the scoping review.

2.5. Coding of studies/Data extraction

After the inclusion of all relevant studies (i.e., 6), two authors (KM and FRC) autonomously performed data extraction. A pre-designed coding table was used to list data from each of the 6 included studies based on: First Author, Year, Country, Objective, Study Design/Type, Sample Size and Age Range (whole sample), Sex (whole sample), Descriptive Statistics by Group, Setting, Treatment Characteristics (Type: single, group based), Length (Duration in terms of hours, number of sessions), Follow-up, Outcome Measures, and Results/Outcomes (see Table 4 showing the characteristics of included studies). KM and FRC independently coded the studies and settled disagreements through mutual accord. All studies were included.

Table 4.

Characteristics of included studies (n = 6).

| Sr. No | First Author, year | Country | Objective | Study Design/Type | Sample size and age range (whole sample) | Sex (whole sample) | Descriptive statistics by group |

Setting | Treatment characteristics (Type: single, group based) | Length (Duration in terms of hours, number of sessions) | Follow-up | Outcome measure | Results/Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (mean age, SD age) | ||||||||||||||

| ADHD group | Comparison/Control Group (if any) | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Bayat et al., 2019 | Iran | To compare the effectiveness of dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) with acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) on quality of life and to reduce the symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) | Experimental study | N = 45 (15 in ACT, 15 in DBT and 15 in control group) | __--- | 15 | 15 | Azad University of Zanjan | Single | 12 sessions | __---_ | self-reported attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ASRS) World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire |

The results of both ACT and DBT treatments on ADHD and quality of life were more effective than control group. In the follow up phase, the LSD test showed that DBT was more effective than ACT in reducing impulsivity/hyperactive symptoms (P < 0.002) and attention deficit (P < 0.001). Comparison of these two treatments on quality of life was found in the components of overall quality of life (P < 0.008), mental health (P < 0.001), quality of life (p < 0.000) and environmental quality of life (P < 0/000) ACT has a more favorable efficacy than DBT. While they have had the same effect on the subscale of social life quality. |

| 2 | Fullen et al., 2020 | UK | The outcomes of a remotely delivered manualised form of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) to adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) during the COVID-19 imposed “lockdown” | Experimental study | N = 12 | 4 F, 8 M | 12 (M age = 21.92, SD = 1.93) | __---____ | South West Yorkshire Partnership Foundation Trust Adult ADHD and Autism Service case load | Single; administered remotely via telephone and video conferencing | 3 sessions; varied in length ranging from 45 - 90 min | two weeks follow-up | Public Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) Brief Adjustment Scale-6 (BASE-6) |

Preliminary findings suggest this cost effective and remotely delivered psychotherapeutic approach might be one appropriate method for supporting the well-being and adjustment of adults with ADHD during future COVID-19 or other pandemic related lockdowns. |

| 3 | Gholipour et al., 2019 | Iran | To investigate the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on ADHD symptoms and academic procrastination of ADHD adolescents | quasi-experimental design | N = 16 | __---_ | 8 | 8 | Psychiatric and Psychological Service centers | ___---___ | 10 session | ____ | Child Symptom Index (CSI-4) Savari’ s Academic Procrastination Scale |

The ACT intervention had no significant effect on inattentiveness, but it was effective on hyperactivity/impulsivity. Also, the results showed that interventions reduced deliberate procrastination, caused by physical-mental fatigue and lack of schedule, and the total score of procrastination. |

| 4 | Murrell et al., 2015 | USA | The feasibility of using acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) to foster increases in congruence between values and behaviors pertinent to those values | quasi-experimental design | N = 9 (11–15 years; M = 11.78, SD = 1.30) | 5 F, 4 M | 9 | ____---__ | charter school in an urban, South-central area of the United States (school was designed specifically for children with ADHD) | Group | __--- | __--- | Avoidance and Fusion Questionnaire for Youth (AFQ-Y) Behavior Assessment System for Children, second edition (BASC-2) comprising: the Teacher Rating Scales (TRS), the Parent Rating Scales (PRS), the structured developmental history (SDH) form, the student observation system (SOS), and the self-report of personality (SRP) |

The data suggests that acceptance and mindfulness based treatments may be feasible and effective for use with children and adolescents with ADHD, LD's, and comorbid behavior problems. |

| 5 | Vanzin et al., 2020 | Italy | To evaluate the effectiveness of an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)-based training protocol, in adjunct to token economy and previous parent training, in a sample of children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). | explorative single-arm open-label study | N = 31 (8–13 years; Mage = 10.7 years, SD = 1.4) | 2 F, 29 M | 31 | ___---___ | Child Psychopathology Unit of the Institute for ADHD treatment | Group | 9-month ACT training programme | ____ | Conners' Parent Rating Scale -Revised: Long version (CPRS-R:L) Clinical Global Impression -Severity (CGI-S) |

At the end of the ACT protocol, children showed significant improvement in global functioning and behavioural symptoms. There were significant improvements in the CPRS subscales Cognitive Problems (p = 0.005), Hyperactivity (p = 0.006), Perfectionism (p = 0.017), ADHD Index (p = 0.023), Global Index: Restless–Impulsive (p = 0.023), Global Index: Total (p = 0.036), DSM IV Inattentive (p = 0.029), DSM IV Hyperactive–Impulsive (p = 0.016), and DSM IV Total (p = 0.003). When controlling for the confounding effect of pharmacological therapy, comorbidities and socio-economic status, treatment maintained a significant effect on the CPRS subscales Perfectionism (partial η2 = 0.31, p < 0.01), Global Index: Restless–Impulsive (partial η2 = 0.29, p < 0.01), Global Index: Total (partial η2 = 0.31, p < 0.01), DSM IV Hyperactive–Impulsive (partial η2 = 0.20, p = 0.02). Symptom severity as rated by CGI-S scores decreased in 74.2% of the children. |

| 6 | Vanzin et al., 2020 | Italy | To investigate the efficacy of a cognitive-behavioural group training based on acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) on cognition in drug-naïve children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) | explorative single-arm open-label study | N = 29 (8–13 years; Mean age = 10.25, SD = 1.35) | F 5, M 24 | 29 | 25; Mage = 10.91, SD = 1.42 (F2, M23) | recruited from the Child Psychopathology Unit | Group | 9-month ACT training programme; 26 weekly sessions of group therapy lasting 90 min each | Amsterdam Neuropsychological Tasks Conners' Parent Rating Scale-R ADHD Rating Scale IV Parent Version — Investigator completed (ADHD-RS) Clinical Global Impression-Severity Scale |

The cognitive outcome of children receiving ACT-group intervention was compared to that of an external untreated control group of children with ADHD. No significant improvements were observed in any of the cognitive measures. This preliminary study suggests that the 9-month ACT-group training programme might not have positive effects on cognitive difficulties usually occurring in ADHD. | |

2.6. Analysis strategy

Standard methods of thematic analysis (Liamputtong and Ezzy, 2005) were conducted to analyze the included studies.

2.7. Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis was not conducted owing to heterogeneity in the included studies. Furthermore, no additional subgroup or sensitivity analyses were conducted, as they were not in line with the aims of this review.

3. Results

3.1. Study characteristics

The characteristics of the 6 articles are mentioned in Table 3. Included studies were published between 2015 and 2020. Two studies were conducted in Iran and Italy, respectively followed by the USA and the UK. The studies were based on quasi-experimental (n = 2) and experimental designs (n = 4). Additionally, three studies provided the ACT in a group therapy format while two studies in an individual therapy format with variation in terms of number and duration of sessions.

3.2. Sample and participant characteristics

The sample size of participants in the articles differed from 9 to 45. Furthermore, the participants ranged in age from 8 to 23 years. A total of 142 participants took part, based on the data mentioned in the included studies, out of which 63 males and 16 females. There was no clear information in the studies if the included participants were on any medications. However, one of the included studies specifically mentioned that participants who were on stimulant medication with methylphenidate were excluded from the analyses (Vanzin et al., 2020). Additionally, the study by Vanzin et al. (2019) for possible confounding variables such as medication/pharmacotherapy.

3.3. Psychological assessment tools

As shown in Table 4, a variety of assessment measures were used in the included studies. For instance, the Conners' Parent Rating Scale-R (Conners et al., 1998) as well as Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long version (CPRS-R:L; Conners, 1997) were administered in two studies. Likewise, two studies used the Clinical Global Impression-Severity Scale (CGI-S; Busner and Targum, 2007). Some other scales were, Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001), Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006), Brief Adjustment Scale-6 (BASE-6; Peterson, 2015), and Self-Reported Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ASRS; Kessler et al., 2005).

3.4. Themes

3.4.1. Comparison of ACT with other treatments

To ascertain the effectiveness of ACT, two studies compared it with token economy and past parent training (see details in following section), and dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), respectively (Bayat et al., 2019; Vanzin et al., 2019). A study by Bayat et al. (2019) in Iran recruited 45 participants with ADHD and randomly allocated an equal number of participants to ACT, DBT and the control group. They aimed to gauge improvements in quality of life (QoL) as well as reduction in ADHD symptoms. The ACT was provided for 12-sessions in individual sessions and findings revealed that both the ACT and DBT were effective in reducing ADHD symptoms as well as improving QoL as compared to the control group. Furthermore, in the follow-up phase, the post-hoc analysis revealed that DBT had higher effectiveness than ACT in reducing impulsivity/hyperactive symptoms and attention deficit. Nonetheless, ACT was found to be more effective than DBT in the comparison of these two treatments on overall QoL, mental health, QoL, and environmental QoL.

Likewise, the explorative single-arm open-label study by Vanzin et al. (2019) ascertained the usefulness of ACT with token economy and past parent training as every parent attended an ACT-based Cognitive Behavioural Parent Training for at least three months prior to assessing children. The authors recruited 31 children with ADHD and administered a nine-month ACT group-training programme in Italy. The findings demonstrated statistically significant results across all the CPRS-R:L (Conners, 1997) and the CGI-S (Busner and Targum, 2007). Specifically, there were significant improvements in all the CPRS subscales (i.e., Cognitive Problems, Hyperactivity, Perfectionism, ADHD Index, Global Index: Restless–Impulsive, Global Index: Total, DSM IV Inattentive, DSM IV Hyperactive–Impulsive, and DSM IV total). These effects were maintained even after controlling the effects of the confounding and other socio-demographic variables. Additionally, there was a substantial reduction in symptom severity in the children.

3.4.2. ADHD symptoms based on pre-test post-test designs

A total of four studies assessed the improvements in ADHD symptoms and reduction in their severity based on different Pre-test post-test designs (i.e., the experimental, quasi-experimental, and explorative single-arm open-label study design). For instance, Fullen et al. (2020) assessed the potential viability of a cost-effective brief psychotherapeutic manual informed by the ACT approach to facilitate the psychosocial adjustment of persons with ADHD to the COVID-19 and the restrictions implemented following the lockdown. A total of 12 adults with ADHD were recruited and three sessions of a manualised form of ACT was delivered remotely via telephone and video conferencing followed by a two-week follow-up. The findings demonstrated that the cost-effective and remotely administered ACT was an adequate way to sustain the mental health and adjustment of adults having ADHD during future COVID-19 or other epidemic-related-lockdowns (Fullen et al., 2020).

Specifically, substantial improvements were found on measures associated to self-reported mood, anxiety, psychosocial adjustment and treatment acceptability was good (Fullen et al., 2020). Likewise, another study evaluated the viability of ACT among school-going individuals with comorbid ADHD, learning disorders, and disruptive behavior issues. A total of nine children attended 1-hour group sessions, once a week for 8 weeks and it was found that nearly one-third of them had a significant difference in wide behavioral symptoms or value-consistent behavior (Murrell et al., 2015).

Additionally, a single-arm, open-label study compared usefulness of ACT-based group child training course across various cognitive domains (i.e., focused, and sustained attention, inhibition, and flexibility) in 29 school-aged individuals with ADHD (Vanzin et al., 2020). However, the findings of this 9-month ACT group training programme, comprising 26 weekly sessions, did not demonstrate a conclusive indication regarding usefulness of ACT-based group child training on cognitive performance of children with ADHD (Vanzin et al., 2020). A similar evaluation was conducted to assess the usefulness of 10-session ACT for ADHD symptoms as well as academic procrastination of 16 adolescents (Gholipour et al., 2019). At the end of the intervention, it was found that the ACT was useful in lowering hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms as well as procrastination.

4. Discussion

This scoping review examined effectiveness of ACT approaches for individuals with ADHD. The small number of studies (N = 6) and their recency (published from the year 2015 onwards) suggests that the use of ACT among individuals with ADHD is still a new modality that may benefit from further exploration of its effectiveness on this population.

The results also indicated that ACT was used as a treatment modality for individuals with ADHD for a variety of behavioural and psychosocial domains, which included reducing ADHD symptoms (e.g., behaviour, focussed and sustained attention, inflexibility, etc.; Bayat et al., 2019; Gholipour et al., 2019; Vanzin et al., 2020; Murrell et al., 2015; Vanzin et al., 2019; Vanzin et al., 2020) and other sequelae related to the ADHD diagnosis such as quality of life, academic procrastination, depression and anxiety symptoms, and psychological adjustment (Bayat et al., 2019; Fullen et al., 2020; Gholipour et al., 2019). This shows that ACT was a flexible approach that could be adapted to deliver both targeted treatment of ADHD symptomatology and more general psychosocial issues, and also that it could be delivered in group or individual formats. Elsewhere, ACT had been used as an adjunct therapy to improve young adults with ASD's athletic performance (Szabo et al., 2019) and psychological distress symptoms (Pahnke et al., 2019). The flexibility of the ACT bodes well for further exploration of its effectiveness in ADHD individuals.

In terms of its effectiveness, the studies explored in this scoping review revealed that ACT was effective in reducing ADHD cognitive symptoms (Bayat et al., 2019; Vanzin et al., 2020) and behavioural symptoms (Bayat et al., 2019; Gholipour et al., 2019; Murrell et al., 2015; Vanzin et al., 2020). The effectiveness of ACT was extended to psychosocial and QoL outcomes (Bayat et al., 2019; Fullen et al., 2020). One study using group training but failed to record significant improvements in the cognitive domain (Vanzin et al., 2020). Nevertheless, it should be considered that these articles suffered from methodological weaknesses such as using experimental, quasi-experimental, and explorative single-arm open-label study designs and none of them were randomized controlled trials. The small sample sizes of the studies (ranging from 9 to 45) also precluded a wider generalization of study findings.

4.1. Clinical implications and future directions

Scoping review methodology does not aim to assess the quality of evidence or integrate the selected records based on efficacy of the various kinds of intervention. Still, present scoping review verifies a paucity of literature around the use of ACT among individuals with ADHD. The findings of the current review suggest that our understanding of whether ACT is effective for individuals having ADHD is still quite limited. Although the findings suggest an encouraging start, it is still quite soon to be certain that ACT is the best possible psychological intervention. In view of the largely positive findings in the application of ACT among ADHD children and adolescents, methodologically rigorous studies involving randomization, controlling for medication status, type and dosage, and larger sample size would be required to confirm its effectiveness. Furthermore, there is a need for future experiments evaluating the effectiveness of ACT on ADHD versus placebo conditions. In this regard, the direct comparison of the effectiveness of different types of therapies with ACT would be appropriate, considering how different variables (i.e., clinical and baseline psychological) could influence the treatment approaches. Also, meta-analysis should be conducted in future placebo-controlled experiments to really assess the effect of ACT on ADHD.

4.2. Limitations

Several shortcomings should be kept in mind when taking the findings from this scoping review. The exclusion of unpublished literature as well as studies in languages other than English and Persian may have prejudiced the usefulness of ACT interventions and increased chances of publication bias. This is because this review was restricted to English/Persian articles showed in electronic databases; studies in other languages may have been overlooked. Furthermore, owing to a high heterogeneity of the included papers, meta-analysis couldn't be run. Additionally, other limitations were related to the including three studies (Bayat et al., 2019; Fullen et al., 2020; Gholipour et al., 2019) published in non-credible journals (i.e., not indexed in the acceptable databases) should also be taken into account when pooling the results. Nevertheless, the findings of remaining studies (Murrell et al., 2015; Vanzin et al., 2019, 2020) still point towards the same conclusion regarding effectiveness of using ACT among individuals with ADHD.

Considering the afore-mentioned limitations, the findings of this scoping review can be used by health care providers with caution. The findings demonstrated that the application of ACT among individuals with ADHD (adolescents or adults) is comparatively a new modality. Nonetheless, as ACT encourages broad and flexible ranges of behavior and neutralizing psychological processes suggested to cause many human issues, these approaches may be effective. Further exploration is needed to gauge the usefulness of the approach for individuals with ADHD. Additionally, the initial findings raised the need of replications and more comparisons against active treatment conditions to ascertain if these treatments are less or equally effective compared to ACT. Also, while the findings of the this review suggest promising findings, more research is needed.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

Acceptance_Supplementary table 1_PRISMA Checklist

References

- A-tjak J.G., Davis M.L., Morina N., Powers M.B., Smits J.A., Emmelkamp P.M. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy for clinically relevant mental and physical health problems. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015;84(1):30–36. doi: 10.1159/000365764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AAP ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1007–1022. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA . American Psychiatric Association: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- APA . Author; Arlington, VA: 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bai Z., Luo S., Zhang L., Wu S., Chi I. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) to reduce depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;260:728–737. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayat M., Fekri S.M., Soraya T.D.K., Dedar T.M.A.F. Comparing the effectiveness of dialectical behavioral therapy with acceptance-based therapy and commitment to quality of life and reducing symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Med. J. Mashhad Univ. Med. Sci. 2019;62(4):1671–1683. https://www.sid.ir/en/Journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=723382 [Google Scholar]

- Blackledge J.T., Ciarrochi J., Deane F.P. Australian Academic Press; 2009. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Contemporary Theory Research and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Bond F.W., Bunce D. Mediators of change in emotion-focused and problem-focused worksite stress management interventions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000;5(1):156. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busner J., Targum S.D. The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa. : Township)) 2007;4(7):28–37. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20526405 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2880930/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne G., Ghráda Á.N. The application and adoption of four ‘third wave’psychotherapies for mental health difficulties and aggression within correctional and forensic settings: a systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019;46:45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne G., Ghráda Á.N., O'Mahony T., Brennan E. A systematic review of the use of acceptance and commitment therapy in supporting parents. Psychol. Psychother. Theor. Res. Pract. 2020 doi: 10.1111/papt.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalá-López F., Hutton B., Núñez-Beltrán A., Page M.J., Ridao M., Macías Saint-Gerons D., Catalá M.A., Tabarés-Seisdedos R., Moher D. The pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review with network meta-analyses of randomised trials. PloS One. 2017;12(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners C. CRS–R, Conners’ rating scales–revised: instruments for use with children and adolescents. Multi-Health Syst. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Conners C.K. Forty years of methylphenidate treatment in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Atten. Disord. 2002;6(1_suppl):17–30. doi: 10.1177/070674370200601s04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners C.K., Sitarenios G., Parker J.D.A., Epstein J.N. The revised Conners' parent rating scale (CPRS-R): factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1998;26(4):257–268. doi: 10.1023/a:1022602400621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dindo L., Van Liew J.R., Arch J.J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: a transdiagnostic behavioral intervention for mental health and medical conditions. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(3):546–553. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0521-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinet J., Favart M., Passerault J.M. Searching for information in an online public access catalogue (OPAC): the impacts of information search expertise on the use of Boolean operators. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2004;20(5):338–346. [Google Scholar]

- Eifert G.H., Forsyth J.P. New Harbinger Publications; 2005. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Anxiety Disorders: A Practitioner's Treatment Guide to Using Mindfulness, Acceptance, and Values-Based Behavior Change. [Google Scholar]

- Faraone S.V., Biederman J., Spencer T.J., Aleardi M. Comparing the efficacy of medications for ADHD using meta-analysis. Medsc. Gen. Med. 2006;8(4):4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman E.M., Herbert J.D., Moitra E., Yeomans P.D., Geller P.A. A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. Behav. Modif. 2007;31(6):772–799. doi: 10.1177/0145445507302202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullen T., Galab N., Abbott K.A., Adamou M. Acceptance and commitment therapy for adults with ADHD during COVID-19: an open trial. Open J. Psychiatr. 2020;10(4):205. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudiano B.A., Herbert J.D. Acute treatment of inpatients with psychotic symptoms using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: pilot results. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006;44(3):415–437. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholipour K.S., Livarjani S., Hoseyninasab D. Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on the symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and academic procrastination of adolescents with ADHD. Sci. J. Rehab. Med. 2019;8(2):106–118. https://www.sid.ir/en/Journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=723456 [Google Scholar]

- González-Fernández S., Fernández-Rodríguez C. Acceptance and commitment therapy in cancer: review of applications and findings. Behav. Med. 2019;45(3):255–269. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2018.1452713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham C.D., Gouick J., Krahe C., Gillanders D. A systematic review of the use of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in chronic disease and long-term conditions. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016;46:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz K.L., Gunderson J.G. Preliminary data on an acceptance-based emotion regulation group intervention for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behav. Ther. 2006;37(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg J.A., Callaghan G.M., Hayes S.C., Glenn-Lawson J.L. Improving diabetes self-management through acceptance, mindfulness, and values: a randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007;75(2):336. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behav. Ther. 2004;35(4):639–665. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C., Barnes-Holmes D., Roche B. Springer; 2001. Relational Frame Theory: A post-Skinnerian Account of Human Language and Cognition. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C., Luoma J.B., Bond F.W., Masuda A., Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006;44(1):1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelson J., Rollin A., Ridout B., Campbell A. Internet-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy for anxiety treatment: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019;21(1) doi: 10.2196/12530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R., Adler L., Ames M., Demler O., Faraone S., Hiripi E., Howes M., Jin R., Secnik K., Spencer T. The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med. 2005;35(2) doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen R., Lehtonen T., Skarp E., Taubert E., Ojanen M., Hayes S.C. The impact of CBT and ACT models using psychology trainee therapists: a preliminary controlled effectiveness trial. Behav. Modif. 2007;31(4):488–511. doi: 10.1177/0145445506298436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liamputtong P., Ezzy D. Second. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. Qualitative Research Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Luoma J.B., Hayes S.C., Walser R.D. New Harbinger Publications; 2007. Learning ACT: an Acceptance & Commitment Therapy Skills-Training Manual for Therapists. [Google Scholar]

- Mason R., O'rinn S.E. Co-occurring intimate partner violence, mental health, and substance use problems: a scoping review. Glob. Health Action. 2014;7(1):24815. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.24815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays N., Roberts E., Popay J. Vol. 220. Routledge; 2001. (Synthesising Research Evidence). [Google Scholar]

- MeSH . U.S. National Library of Medicine; 2019. Medical Subject Headings.www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/meshhome.html [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munawar K., Choudhry F.R., Hadi M.A., Khan T.M. Prevalence of and factors contributing to glue sniffing in the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) region: a scoping review and meta-analysis. Subst. Use Misuse. 2020;55(5):752–762. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2019.1701036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrell A.R., Steinberg D.S., Connally M.L., Hulsey T., Hogan E. Acting out to ACTing on: a preliminary investigation in youth with ADHD and Co-morbid disorders. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015;24(7):2174–2181. [Google Scholar]

- Öst L.-G. Efficacy of the third wave of behavioral therapies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2008;46(3):296–321. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öst L.-G. The efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2014;61:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahnke J., Hirvikoski T., Bjureberg J., Bölte S., Jokinen J., Bohman B., Lundgren T. Acceptance and commitment therapy for autistic adults: an open pilot study in a psychiatric outpatient context. J. Context. Beh. Sci. 2019;13:34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Peters M.D.J., Godfrey C.M., Khalil H., McInerney P., Parker D., Soares C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implementat. 2015;13(3):141–146. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson A.P. 2015. Psychometric Evaluation of the Brief Adjustment Scale-6 (BASE-6): A New Measure of General Psychological Adjustment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham M.T., Rajić A., Greig J.D., Sargeant J.M., Papadopoulos A., McEwen S.A. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res. Synth. Methods. 2014;5(4):371–385. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliszka S., Issues A.W. G.o.Q. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2007;46(7):894–921. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318054e724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanczyk G., De Lima M.S., Horta B.L., Biederman J., Rohde L.A. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2007;164(6):942–948. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayal K., Prasad V., Daley D., Ford T., Coghill D. ADHD in children and young people: prevalence, care pathways, and service provision. Lancet Psychiatr. 2018;5(2):175–186. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schardt C., Adams M.B., Owens T., Keitz S., Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Making. 2007;7(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B., Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain J., Hancock K., Hainsworth C., Bowman J. Acceptance and commitment therapy in the treatment of anxiety: a systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013;33(8):965–978. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo T.G., Willis P.B., Palinski C.J. Watch me try: ACT for improving athletic performance of young adults with ASD. Adv. Neurodev. Dis. 2019;3:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Taheri A.A., Foroughi A.A., Mohammadian Y., Ahmadi S.M., Heshmati K., Hezarkhani L.A., Parvizifard A.A. The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on pain acceptance and pain perception in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy: a randomized controlled trial. Diab. Therapy. 2020;11(8):1695–1708. doi: 10.1007/s13300-020-00851-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosto M.G., Momi S.K., Asherson P., Malki K. A systematic review of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and mathematical ability: current findings and future implications. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0414-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twohig M.P., Levin M.E. Acceptance and commitment therapy as a treatment for anxiety and depression: a review. Psychiatr. Clin. 2017;40(4):751–770. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanzin L., Crippa A., Mauri V., Valli A., Mauri M., Molteni M., Nobile M. Does ACT-group training improve cognitive domain in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder? A single-arm, open-label study. Behav. Change. 2020;37(1) [Google Scholar]

- Vanzin L., Mauri V., Valli A., Pozzi M., Presti G., Oppo A., Ristallo A., Molteni M., Nobile M. Clinical effects of an ACT-group training in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019;29:1070–1080. [Google Scholar]

- Vowles K.E., McNeil D.W., Gross R.T., McDaniel M.L., Mouse A., Bates M., Gallimore P., McCall C. Effects of pain acceptance and pain control strategies on physical impairment in individuals with chronic low back pain. Behav. Ther. 2007;38(4):412–425. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks K.R., Gould R.L., Mcdermott C., Lynch J., Goldstein L.H., Graham C.D., McCracken L., Serfaty M., Howard R., Al-Chalabi A. Needs and preferences for psychological interventions of people with motor neuron disease. Amyotr. Lat. Scler. Frontotemp Degen. 2019;20(7-8):521–531. doi: 10.1080/21678421.2019.1621344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 1993. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Geneva. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zettle R. New Harbinger Publications; 2007. ACT for Depression: A Clinician's Guide to Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in Treating Depression. [Google Scholar]

- Zettle R.D., Hayes S.C. Dysfunctional control by client verbal behavior: the context of reason-giving. Anal. Verbal Behav. 1986;4(1):30–38. doi: 10.1007/BF03392813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Acceptance_Supplementary table 1_PRISMA Checklist

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.