Abstract

Background

The impact of obesity on outcomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is not well understood and remains controversial. Recent studies suggest that obesity might be associated with higher morbidity and mortality in respiratory disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19 disease). Our objective was to evaluate the association between obesity and hospital mortality in critical COVID-19 patients.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study in a tertiary academic center located in Montréal between March and August 2020. We included all consecutive adult patients admitted to the ICU for COVID-19-confirmed respiratory disease. Our main outcome was hospital mortality. We estimated the association between obesity, using the body mass index as a continuous variable, and hospital survival by fitting a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

We included 94 patients. Median [q1, q3] body mass index (BMI) was 29 [26–32] kg/m2 and 37% of patients were obese (defined as BMI > 30 kg/m2). Hospital mortality for the entire cohort was 33%. BMI was significantly associated with hospital mortality (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.49 per 10 units BMI; 95% CI, from 1.69 to 3.70; p < 0.001) even after adjustment for sex, age and obesity-related comorbidities (adjusted HR = 3.50; 95% CI from 2.03 to 6.02; p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Obesity was prevalent in hospitalized patients with critical illness secondary to COVID-19 disease and a higher BMI was associated with higher hospital mortality. Further studies are needed to validate this association and to better understand its underlying mechanisms.

Subject terms: Risk factors, Obesity

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity is increasing both in the general and the critically-ill population, where one out of five hospitalized patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) is obese [1–5]. While obesity is usually associated with unfavorable clinical outcomes in many clinical settings, observational data suggest that obese patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) may have better outcomes [6]. This phenomenon has been named the “obesity paradox” by some authors [2, 3]. However, the protective effect of obesity in ARDS is not well understood and remains controversial [2, 7].

Recent studies suggest that obesity might be associated with a higher risk of developing severe COVID-19 respiratory disease [8–16]. A population-based analysis of a large UK biobank even suggests a dose-response relationship between the risk of severe COVID-19 disease and increasing BMI, waist circumference, or waist-to-hip ratio [8]. Similar findings were also reported in a meta-analysis involving over 100,000 patients and suggesting an increased risk of critical COVID-19 disease (odds ratio [OR] = 1.09; 95% CI, from 1.04 to 1.14; n = 3825; six studies) and mortality (OR = 1.06; 95% CI, from 1.02 to 1.10; n = 2704; four studies) with each 1 kg/m2 increase in BMI [17]. Other studies also report higher mortality in hospitalized obese COVID-19 patients than in nonobese ones [11, 18].

In the subset of patients with the most severe forms of COVID-19 (critical COVID-19 disease, as defined by the World Health Organization [19]), limited data are available. Few studies measured the association between obesity and hospital mortality in this patient population, and among those who did, most included both critically ill and hospitalized patients with a less severe form of the disease [11, 20–22]. Among studies that focused on critically-ill patients, a significant harmful association between obesity and hospital mortality has not been observed consistently [18, 23–29]. A recent systematic review of predictors of in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 concluded that obesity was only associated with mortality in studies that included fewer critically-ill patients [24]. However, these studies used ill-specified multivariable models that did not focus on the association between obesity and hospital mortality and used heterogeneous obesity categorizations [14, 18, 25, 30–32]. Thus, the association between obesity, defined as a high body mass index (BMI), and hospital mortality specifically in critical COVID-19 patients is not yet well-defined.

To better define this association in the subgroup of critically ill COVID-19 patients, we conducted a retrospective cohort study. Our primary objective was to measure the association between the BMI and hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 respiratory disease requiring ICU admission. Our main hypothesis was that higher BMI would be associated with lower hospital survival. Our secondary objective was to describe a sample of critically-ill patients with COVID-19 from an urban academic center in Montréal, Canada.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a retrospective cohort study at the Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM), a 800-bed tertiary academic center located in Montréal. The CHUM’s ICU is a 66-bed mixed medical and surgical unit with 24 h staff coverage, and serves as a regional reference center for advanced respiratory support. This study was approved by the CHUM research ethics board.

Study population

We included all consecutive adult patients (over 18 years old) admitted to the ICU during their hospital stay for a COVID-19-related respiratory disease between March and August 2020. This time period corresponds to the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. We included patients who were admitted directly from the emergency department, transferred from a regular hospital ward for progressive respiratory failure, or referred from another hospital. All included patients had pneumonia as diagnosed by an attending physician and SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by PCR performed on either a nasopharyngeal swab or an endotracheal specimen. We excluded patients admitted to the ICU with a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR for any indication other than pneumonia.

At the beginning of the study period, local criteria to consider an ICU admission were oxygen supply exceeding 5 L/min, increased work of breathing after evaluation by the treating physician, or requirement for advanced respiratory support (high-flow nasal cannula, bi-level non-invasive ventilation, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), in addition to usual criteria for admission to a critical care unit (hypotension, altered state of consciousness, among others). As the first wave progressed, indications to transfer patients to the ICU became more conservative, and high-flow nasal cannula was offered as a treatment on the wards. A long-lasting need for bi-level non-invasive mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory failure always required an ICU admission.

Data measurements and variables

Our exposure of interest was BMI. Weight and height used to calculate BMI were measured at the ICU admission, and collected retrospectively by chart review. For the description of our cohort, we defined obesity as BMI exceeding 30 kg/m2 and dichotomized patients accordingly, although we used BMI as a continuous variable for our statistical analyses. We also collected baseline demographics and comorbidities, organ-support interventions and hospital length of stay. Hospital length of stay was defined as the time elapsed between hospital admission and hospital discharge, in days.

Our main outcome was survival at hospital discharge. Patients discharged alive were censored at discharge, and patients still hospitalized were censored at the date of data collection (November 11, 2020). We extracted data from manual chart review.

Statistical analysis

We described baseline patient characteristics and comorbidities using mean (standard deviation) or median (quartiles 1 and 3) for continuous variables, and proportions for categorical variables. We reported all variables descriptively in obese and nonobese patients as defined previously. Height was missing for seven observations, and was imputed using the mean population value for Canadians (161 cm for women, 175 cm for men) [33].

We estimated the association between BMI and survival at hospital discharge using a Cox proportional hazards models (where the main independent variable was BMI expressed as a continuous variable to maximize statistical power). Based on clinical relevance, we included age (as a continuous variable), sex, hypertension, and diabetes as potential confounders. We tested the proportionality assumption with visual inspection of a Schoenfeld residuals graph and by a Harrel and Lee test. Since the proportionality assumption did not hold for the BMI variable, we fitted a linear time-dependent coefficient [34]. The relation between age and survival was not linear and was best fitted using restricted cubic splines with four knots, based on a visual inspection of the Martingale residuals and the lowest Akaike Information Criterion [35]. As a visual exploratory analysis, we plotted stratified Kaplan–Meier survival curves to estimate survival at 30 and 60 days according to obesity status (dichotomized as BMI ≤ or >30 kg/m2). We also explored the effect of the calendar date of admission on our main outcome. Finally, as a post-hoc exploratory analysis, we fitted a multivariable Cox model to analyze the effects of organ support initiated on the first day of hospital admission on mortality after validation that the risk proportionality assumption was met. We set out alpha level at 0.05 and reported results with 95% Wald confidence intervals. We used R (R foundation, version 3.6.2) for all analyses.

Results

A total of 94 adult patients were included. The median [q1, q3] age of the cohort was 61 [46,76] years old and 66% (n = 63) of patients were men. Median [q1, q3] BMI was 29 [26, 32] kg/m2 and 37% (n = 35) of patients were obese (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Variable | Whole cohort (n = 94) | BMI < 30 (n = 59) | BMI > 30 (n = 35) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 60 (15) | 63 (14) | 57 (16) |

| Sex (female) (%) | 31 (33) | 19 (32) | 12 (34) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29 [26, 32] | 27 [23, 28] | 35 [32, 40] |

| Diabetes (%) | 25 (27) | 16 (27) | 9 (26) |

| Hypertension (%)a | 43 (46) | 22 (37) | 21 (60) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease (%) | 9 (10) | 5 (8) | 4 (11) |

| Chronic kidney disease (%) | 21 (22) | 11 (19) | 10 (29) |

Data are reported as mean (standard deviation), count (proportion, expressed in %) or median [quartiles q1, q3].

BMI body mass index.

aTwo missing values in the BMI < 30 kg/m2 group.

On the first day of their hospital admission, 60% of patients needed oxygen therapy, 41% were intubated, and prone positioning was initiated in 15% of patients (Table 2). During their overall ICU stay, 66% (n = 62) of patients required invasive mechanical ventilation. Prone positioning was performed at least once in 48% of patients (n = 45). Almost all patients received antibiotics during their ICU stay (97%), and 32% were given corticosteroids. Two patients received an antiviral drug combination (lopinavir/ritonavir) in the context of a research protocol. No patients were given remdesivir or hydroxychloroquine. The median [q1, q3] duration of mechanical ventilation was 20 [9, 32] days (Table 2) and the overall median [q1, q3] hospital length of stay was 26 [11, 47] days (Tables 2 and S1). Obese patients had numerically longer ICU length of stay and duration of mechanical ventilation (Table 2). A numerically higher proportion of obese patients received vasopressors, oxygen therapy, invasive mechanical ventilation and prone positioning on the day of admission and a numerically higher proportion of obese patients received vasopressors and invasive mechanical ventilation during their hospital stay (Table 2). No important difference was observed on the use of pharmacological therapies between groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hospital and ICU stay characteristics.

| Variable | Whole cohort (n = 94) | BMI < 30 (n = 59) | BMI > 30 (n = 35) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital LOS | 26 [11, 47] | 25 [13, 44] | 26 [8, 53] |

| ICU LOS | 13 [6, 29] | 12 [6, 24] | 14 [3, 35] |

| Organ support on the day of hospital admission | |||

| Any vasopressor (%) | 37 (39) | 20 (34) | 17 (49) |

| Any oxygen therapy (%) | 56 (60) | 30 (51) | 26 (74) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation (%) | 39 (41) | 19 (32) | 20 (57) |

| Prone positioning (%) | 14 (15) | 6 (10) | 8 (23) |

| ECMO (%) | 4 (4) | 1 (2) | 3 (9) |

| Treatments during the ICU stay | |||

| Antibiotics (%) | 91 (97) | 57 (97) | 34 (97) |

| Antiviralsa (%) | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) |

| Corticosteroids (%) | 30 (32) | 19 (32) | 11 (31) |

| Organ support during the ICU stay | |||

| Any vasopressor (%) | 70 (74) | 40 (68) | 30 (86) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation (%) | 62 (66) | 36 (61) | 26 (74) |

| Duration of invasive mechanical ventilation (days) | 20 [9, 32] | 19 [9, 28] | 25 [9, 34] |

| Prone positioning (%) | 45 (48) | 28 (47) | 17 (49) |

| ECMO (%) | 4 (4) | 1 (2) | 3 (9) |

Data are reported as mean (standard deviation), count (proportion, expressed in %) or median [quartiles q1, q3].

ECMO extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ICU intensive care unit.

aLopinavir/ritonavir.

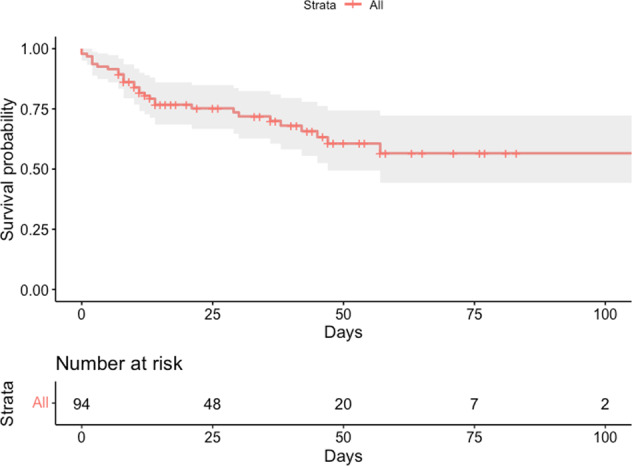

Hospital mortality was 33% (n = 31) for the entire cohort, 43% in obese patients and 27% in nonobese patients (Table 3, Figs. 1 and S1). A higher BMI was significantly associated with higher hospital mortality (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.49 per ten units of BMI increase; 95% CI, from 1.69 to 3.70; p < 0.001) (Table 4). After adjusting for age, sex, diabetes and hypertension, BMI remained associated with hospital mortality (adjusted HR = 3.50, 95% CI 2.03–6.02; p < 0.001), with a significant decremental effect over time after hospital admission (HR = 0.97 per ten units of BMI increase and any passing day; 95% CI, from 0.94 to 0.99; p = 0.043) (Table 4 and Fig S2). As an exploratory analysis, the calendar date of hospital admission had no effect on overall survival (HR = 1.00; 95% CI, from 0.99 to 1.02; p = 0.99). Organ support therapies initiated on the day of hospital admission (oxygen therapy, vasopressors, invasive mechanical ventilation, prone positioning, ECMO) were variably associated with hospital mortality (Table S2).

Table 3.

Hospital mortality and estimates of survival.

| Outcome | Whole cohort (n = 94) | BMI < 30 (n = 59) | BMI > 30 (n = 35) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital mortality (%) | 31 (33) | 16 (27) | 15 (43) |

| 30-day survival [95% CI]a | 0.72 [0.63–0.82] | 0.80 [0.69–0.91] | 0.60 [0.45–0.80] |

| 60-day survival [95% CI]a | 0.57 [0.44–0.72] | 0.59 [0.42–0.83] | 0.51 [0.35–0.74] |

BMI body mass index.

aKaplan–Meier survival (S) estimates with 95% confidence intervals. Mortality may be computed by 1 – S.

Fig. 1. Kaplan–Meier curve for hospital survival.

Unadjusted Kaplan–Meier curve of hospital survival probability for the entire cohort (n = 94) until 100 days. 95% confidence intervals illustrated as shaded areas.

Table 4.

Multivariable Cox model of hospital survival.

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | ||

| BMI (per 10 units) | 2.49 (1.69–3.70) | <0.001 |

| BMI*time (days) | 0.97 (0.95–1.00) | 0.05 |

| Adjusted | ||

| BMI (per 10 units) | 3.50 (2.03–6.02) | <0.001 |

| BMI*time (days) | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | 0.043 |

| Age | Non-linear | 0.119 |

| Sex (female) | 1.26 (0.56–2.85) | 0.568 |

| Diabetes | 0.55 (0.23–1.32) | 0.183 |

| Hypertension | 1.38 (0.59–3.24) | 0.448 |

Hazard ratios are presented with their 95% confidence intervals.

BMI body mass index, HR hazard ratio.

Discussion

This study is the first report of a large Canadian cohort specifically investigating the effect of obesity on hospital survival of critical COVID-19 patients using BMI as a continuous variable. We found a significant association between BMI and hospital mortality that remained significant after adjustment for some potential confounders.

Our findings are consistent with a recent meta-analysis of 30 observational studies in which a subgroup analysis on seven studies reporting mortality and including 17,646 patients reported similar results in a population of patients with COVID-19 of varying severity (OR = 1.49; 95% CI, from 1.20 to 1.85; I2 = 69%; n = 17,646) [36]. As previously mentioned, these results came mostly from non-critically ill patients. Interestingly, a similar trend was also observed during the H1N1 influenza pandemic, where epidemiological studies reported an association between obesity and worse clinical outcomes in a general and non-critically ill population [37, 38]. Our data support similar effects of obesity in critical COVID-19 patients, albeit characterized by BMI instead of obesity categories.

Obese patients needed more organ support therapies on the day of admission and throughout their hospital stay. These observations might suggest that they were either sicker or treated more aggressively by physicians. The former would be concordant with the observed higher mortality among obese patients while the latter would suggest that some of the supportive therapies were potentially deleterious. Such organ support are thus potential markers of a more severe disease in obese patients or potential mediators of the association between a higher BMI and a higher mortality. These effects should be further studied.

Our study seems to be externally valid. The 30-day mortality in our cohort (28%; 95% CI, from 18 to 37%) was similar to the 28-day mortality reported in contemporary cohorts of critically-ill patients with COVID-19 (25–29%) [39–42]. These mortality rates, and our overall hospital mortality of 33%, are also comparable to those reported in the LUNG-SAFE trial (hospital mortality ranging from 34.9 to 46.1%, depending on ARDS severity), which suggests that patients with critical COVID-19 have a similar survival compared to other patients with ARDS [43]. Sixty-six percent of the patients in our cohort were intubated during their ICU stay, which is comparable to other cohorts in Montréal (57%) [41], New York City (79%) [42] and Washington state (71%) [44], but lower than in France (80%) [39] or Italy (88%) [45]. Thus, our patients had similar mortality than many other reported cohorts, but a lower incidence of mechanical ventilation than European cohorts. We also reported a prevalence of obesity among critical COVID-19 patients of 37%, which is higher than the general Canadian population (24%) [1], but comparable to a large French cohort of critical COVID-19 patients (41% of patients with a BMI > 30 kg/m2) [39]. These observations may suggest that obesity is over-represented in critical COVID-19, although this association should be validated in a population-based study.

The association we observed between a higher BMI and excess mortality in critical COVID-19 seems in contradiction with the “obesity paradox” previously described in “classic” ARDS patients [2, 4]. Possible explanations for this survival benefit are that obese patients might present a higher fraction of atelectasis than nonobese patients for the same degree of hypoxia (offering more ‘treatable’ profile), and that there might be a bias toward early ICU admission of obese ARDS patients, due to clinicians’ fear of an unfavorable evolution [4]. Such a potential bias toward improved survival from preemptive admission in obese patients may come from more aggressive and earlier interventions and monitoring in these patients compared with nonobese patients [2]. These potential advantages for obese patients may have been lost during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, since an early ICU admission policy was applied to all patients requiring relatively low levels of oxygen supplementation (~5 L/min or estimated FiO2 > 40%). Previous studies in ARDS included a heterogeneous patient population, since many etiologies of ARDS were considered. If obesity itself was associated with the incidence of ARDS, and some factors also associated with ARDS had a stronger effect on mortality than obesity, a conditioned analysis may have suggested a biased protective effect of obesity on mortality through a collider-stratification bias. Such bias has been reported in other highly selected populations, such as patient with cardiovascular diseases [46]. By selecting a homogeneous population of patients with critical COVID-19, we may have prevented such a bias.

Our study has some limitations. We did not include ventilator data and arterial blood gas results to further describe ventilator settings and lung physiology, which may limit the face comparability of our study. We did not use esophageal manometry in any patient, a technique that suggested some benefits in obese patients, but did not improve overall outcomes in ARDS patients [47]. Relatively few patients received steroids, since the majority of the patients were enrolled before the publication of the RECOVERY trial [48]. Even though there is no biological rationale to purport that steroids could have a differential effect in obese patients, such an intervention may have decreased overall mortality and reduced the potential risk associated with obesity. We also explored the effect of potential mediators, such as organ support therapies initiated on the day of admission, on hospital mortality using an outcome determination model. This model has several limitations. First, to better define the mediating role of these therapies in the association between BMI and mortality, formal mediation analyses would have been required. Such a causal inference approach is beyond the current work’s objectives [49]. Thus, we did not include BMI in our aforementioned model to prevent the estimation of a direct effect (without estimating properly the complementary indirect effect) as well as to prevent collider-stratification bias [50]. Second, invasive mechanical ventilation may have been offered only to patients with a better baseline prognosis, limiting the interpretation of our estimated coefficients. Moreover, our results are limited by the overall small sample size and the limited available degrees of freedom to adjust for all potential confounders. Thus, we may not exclude potential residual confounding, such as previous fitness and other comorbidities. However, we included all patients requiring an ICU admission in one of the largest Canadian cohort of critical COVID-19 patients during the first wave of the pandemic and used well-specified models to measure the effect of a higher BMI on hospital mortality. The use of BMI as a continuous variable increased statistical power compared to any obesity categorization previously published [18, 25, 30–32].

Conclusion

Obesity was prevalent in our cohort of hospitalized patients presenting a critical COVID-19 and was independently associated with higher hospital mortality. Further studies are needed to better understand the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying this observation and to identify potential interventions to improve outcomes in this population.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our research assistants who worked hard during the pandemic to collect high-quality data as well as every critical care physician who took care of these patients and contributed to clinical data collection.

Author contributions

GP participated in the performance of the research, in data analysis and in writing the paper. EFR participated in research design, in the performance of the research, in data acquisition, and in writing the paper. HTG participated in data acquisition and in writing the paper. LAM participated in data analysis and in writing the paper. MC participated in research design and in writing the paper. FMC participated in research design, in the performance of the research, in data acquisition, in data curation, in data analysis and in writing the paper.

Funding

Drs FMC and MC are recipients of a research career award from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec—Santé. This work was funded by local funds.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41366-021-00938-8.

References

- 1.Agence de la santé publique du Canada. Obésité au Canada—Prévalence de l’obésité chez les adultes [Internet]. aem. 2011 [cited 2020 Dec 16]. https://www.canada.ca/fr/sante-publique/services/promotion-sante/modes-vie-sains/obesite-canada/adultes.html.

- 2.Ball L, Serpa Neto A, Pelosi P. Obesity and survival in critically ill patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a paradox within the paradox. Crit Care. 2017;21:114.. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1682-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schetz M, De Jong A, Deane AM, Druml W, Hemelaar P, Pelosi P, et al. Obesity in the critically ill: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:757–69. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05594-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Jong A, Verzilli D, Jaber S. ARDS in obese patients: specificities and management. Crit Care. 2019;23:74. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2374-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan DH, Ravussin E, Heymsfield S. COVID 19 and the Patient with Obesity – The Editors Speak Out. Obesity. 2020;28:847–847. doi: 10.1002/oby.22808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ni Y-N, Luo J, Yu H, Wang Y-W, Hu Y-H, Liu D, et al. Can body mass index predict clinical outcomes for patients with acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome? A meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2017;21:36.. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1615-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwok S, Adam S, Ho JH, Iqbal Z, Turkington P, Razvi S, et al. Obesity: a critical risk factor in the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Obes. 2020;10:e12403. doi: 10.1111/cob.12403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu Z, Hasegawa K, Ma B, Fujiogi M, Camargo CA, Liang L. Association of obesity and its genetic predisposition with the risk of severe COVID-19: analysis of population-based cohort data. Metabolism. 2020;112:154345. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Földi M, Farkas N, Kiss S, Zádori N, Váncsa S, Szakó L, et al. Obesity is a risk factor for developing critical condition in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2020;21:e13095. doi: 10.1111/obr.13095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pietri L, Giorgi R, Bégu A, Lojou M, Koubi M, Cauchois R, et al. Excess body weight is an independent risk factor for severe forms of COVID-19. Metabolism. 2021;117:154703. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yates T, Zaccardi F, Islam N, Razieh C, Gillies CL, Lawson CA, et al. Obesity, Ethnicity, and Risk of Critical Care, Mechanical Ventilation, and Mortality in Patients Admitted to Hospital with COVID-19: analysis of the ISARIC CCP-UK Cohort. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29:1223–30. doi: 10.1002/oby.23178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu X, Li C, Chen S, Zhang X, Wang F, Shi T, et al. Association of body mass index with severity and mortality of COVID-19 pneumonia: a two-center, retrospective cohort study from Wuhan, China. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13:7767–80. doi: 10.18632/aging.202813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Zhu L, Liu L, Zhao X-A, Zhang Z, Xue L, et al. Overweight and Obesity are Risk Factors of Severe Illness in Patients with COVID-19. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;28:2049–55. doi: 10.1002/oby.22979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chetboun M, Raverdy V, Labreuche J, Simonnet A, Wallet F, Caussy C, et al. BMI and pneumonia outcomes in critically ill COVID-19 patients: an international multicenter study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021. Online ahead of print. 10.1002/oby.23223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Pérez-Cruz E, Castañón-González JA, Ortiz-Gutiérrez S, Garduño-López J, Luna-Camacho Y. Impact of obesity and diabetes mellitus in critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2021;15:402–5. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2021.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soeroto AY, Soetedjo NN, Purwiga A, Santoso P, Kulsum ID, Suryadinata H, et al. Effect of increased BMI and obesity on the outcome of COVID-19 adult patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metabol Syndr: Clin Res Rev. 2020;14:1897–904. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du Y, Lv Y, Zha W, Zhou N, Hong X. Association of Body mass index (BMI) with Critical COVID-19 and in-hospital Mortality: a dose-response meta-analysis. Metabolism. 2020;117:154373.. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomson RJ, Hunter J, Dutton J, Schneider J, Khosravi M, Casement A, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of critically ill patients with COVID-19 admitted to an intensive care unit in London: a prospective observational cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0243710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Clinical management of COVID-19 [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jan 20]. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/clinical-management-of-covid-19.

- 20.Palaiodimos L, Kokkinidis DG, Li W, Karamanis D, Ognibene J, Arora S, et al. Severe obesity, increasing age and male sex are independently associated with worse in-hospital outcomes, and higher in-hospital mortality, in a cohort of patients with COVID-19 in the Bronx, New York. Metabolism. 2020;108:154262. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pettit NN, MacKenzie EL, Ridgway JP, Pursell K, Ash D, Patel B, et al. Obesity is Associated with Increased Risk for Mortality Among Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;28:1806–10. doi: 10.1002/oby.22941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Filardo TD, Khan MR, Krawczyk N, Galitzer H, Karmen-Tuohy S, Coffee M, et al. Comorbidity and clinical factors associated with COVID-19 critical illness and mortality at a large public hospital in New York City in the early phase of the pandemic (March-April 2020) PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0242760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parikh R, Garcia MA, Rajendran I, Johnson S, Mesfin N, Weinberg J, et al. ICU outcomes in Covid-19 patients with obesity. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2020;14:1753466620971146. doi: 10.1177/1753466620971146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mesas AE, Cavero-Redondo I, Álvarez-Bueno C, Sarriá Cabrera MA, Maffei de Andrade S, Sequí-Dominguez I, et al. Predictors of in-hospital COVID-19 mortality: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis exploring differences by age, sex and health conditions. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0241742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolf M, Alladina J, Navarrete-Welton A, Shoults B, Brait K, Ziehr D, et al. Obesity and Critical Illness in COVID-19: respiratory Pathophysiology. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29:870–8. doi: 10.1002/oby.23142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kooistra EJ, de Nooijer AH, Claassen WJ, Grondman I, Janssen NAF, Netea MG, et al. A higher BMI is not associated with a different immune response and disease course in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Int J Obes (Lond). 2021;45:687–94. doi: 10.1038/s41366-021-00747-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman AN, Guirguis J, Kapoor R, Gupta S, Leaf DE, Timsina LR, et al. Obesity, Inflammatory and Thrombotic Markers, and Major Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19 in the US. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021. Online ahead of print. 10.1002/oby.23245. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Pouwels S, Ramnarain D, Aupers E, Rutjes-Weurding L, van Oers J. Obesity May Not Be Associated with 28-Day Mortality, Duration of Invasive Mechanical Ventilation and Length of Intensive Care Unit and Hospital Stay in Critically Ill Patients with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2: a Retrospective Cohort Study. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:674. doi: 10.3390/medicina57070674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Salameh A, Lanoix J-P, Bennis Y, Andrejak C, Brochot E, Deschasse G, et al. The association between body mass index class and coronavirus disease 2019 outcomes. Int J Obes (Lond). 2021;45:700–5. doi: 10.1038/s41366-020-00721-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossi AP, Gottin L, Donadello K, Schweiger V, Nocini R, Taiana M, et al. Obesity as a risk factor for unfavourable outcomes in critically ill patients affected by Covid 19. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;31:762–8. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halasz G, Leoni ML, Villani GQ, Nolli M, Villani M. Obesity, overweight and survival in critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia: is there an obesity paradox? Preliminary results from Italy. Eur J Prevent Cardiol. 2020;0:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Dana R, Bannay A, Bourst P, Ziegler C, Losser M-R, Gibot S, et al. Obesity and mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients with respiratory failure. Int J Obes (Lond). 2021. Online ahead of print. 10.1038/s41366-021-00872-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Table 1 Mean height, weight, body mass index (BMI) and prevalence of obesity, by collection method and sex, household population aged 18 to 79, Canada, 2008, 2007 to 2009, and 2005 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 16]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2011003/article/11533/tbl/tbl1-eng.htm.

- 34.Zhang Z, Reinikainen J, Adeleke KA, Pieterse ME, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM. Time-varying covariates and coefficients in Cox regression models. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:121. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.02.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gauthier J, Wu QV, Gooley TA. Cubic splines to model relationships between continuous variables and outcomes: a guide for clinicians. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55:675–80. doi: 10.1038/s41409-019-0679-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang Y, Lu Y, Huang Y-M, Wang M, Ling W, Sui Y, et al. Obesity in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism. 2020;113:154378. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Louie JK, Acosta M, Samuel MC, Schechter R, Vugia DJ, Harriman K, et al. A Novel Risk Factor for a Novel Virus: obesity and 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) Clin Infect Diseases. 2011;52:301–12. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun Y, Wang Q, Yang G, Lin C, Zhang Y, Yang P. Weight and prognosis for influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 infection during the pandemic period between 2009 and 2011: a systematic review of observational studies with meta-analysis. Infect Diseases. 2016;48:813–22. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2016.1201721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt M, Hajage D, Demoule A, Pham T, Combes A, Dres M, et al. Clinical characteristics and day-90 outcomes of 4244 critically ill adults with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020. Online ahead of print. 10.1007/s00134-020-06294-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Quah P, Li A, Phua J. Mortality rates of patients with COVID-19 in the intensive care unit: a systematic review of the emerging literature. Crit Care. 2020;24:285.. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cavayas YA, Noël A, Brunette V, Williamson D, Frenette AJ, Arsenault C, et al. Early experience with critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Montreal. Can J Anaesth. 2021;68:204–13. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01816-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, Jacobson SD, Meyer BJ, Balough EM, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1763–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Fan E. The LUNG SAFE study: a presentation of the prevalence of ARDS according to the Berlin Definition! Crit Care. 2016;20:268.. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1443-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, Lokhandwala S, Riedo FX, Chong M, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of 21 Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323:1612–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A, et al. Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of 1591 Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 Admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1574. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Banack HR, Kaufman JS. The obesity paradox: understanding the effect of obesity on mortality among individuals with cardiovascular disease. Prev Med. 2014;62:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beitler JR, Sarge T, Banner-Goodspeed VM, Gong MN, Cook D, Novack V, et al. Effect of Titrating Positive End-Expiratory Pressure (PEEP) With an Esophageal Pressure–Guided Strategy vs an Empirical High PEEP-F io2 Strategy on Death and Days Free From Mechanical Ventilation Among Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:846. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.The RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.VanderWeele TJ. Mediation analysis: a practitioner’s guide. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37:17–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vanderweele TJ, Vansteelandt S. Conceptual issues concerning mediation, interventions and composition. Stat Interfac. 2009;2:457–68. doi: 10.4310/SII.2009.v2.n4.a7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.