Abstract

Lipid nanoparticle SNAs (LNP-SNAs) have been synthesized for the delivery of DNA and RNA to targets in the cytoplasm of cells. Both the composition of the LNP core and surface-presented DNA sequences contribute to LNP-SNA activity. G-rich sequences enhance the activity of LNP-SNAs compared to T-rich sequences. In the LNP core, increased cholesterol content leads to greater activity. Optimized LNP-SNA candidates reduce the siRNA concentration required to silence mRNA by 2 orders of magnitude compared to liposome-based SNAs. In addition, the LNP-SNA architectures alter biodistribution and efficacy profiles in mice. For example, mRNA within LNP-SNAs injected intravenously is primarily expressed in the spleen, while mRNA encapsulated by LNPs (no DNA on the surface) was expressed primarily in the liver with a relatively small amount in the spleen. These data show that the activity and biodistribution of LNP-SNA architectures are different from those of conventional liposomal SNAs and therefore potentially can be used to target tissues.

Keywords: Spherical nucleic acids, lipid nanoparticles, drug delivery, RNA

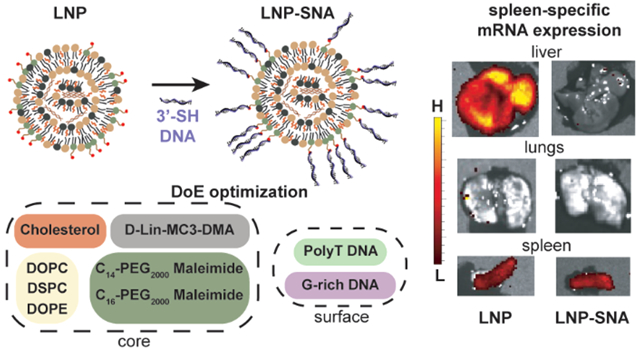

Graphical Abstract

Effective delivery at clinically relevant doses is a challenge limiting the implementation of DNA and RNA therapeutics. Nucleic acids can be used in gene silencing,1–4 genome editing,5–7 gene replacement,8,9 immune system modulation,10–12 and theranostics.13–15 While significant progress has been made in each of these areas, therapy development often requires extensive modification of both the encapsulated DNA and RNA sequence and its carrier to prevent nuclease degradation and enhance tissue and cellular uptake. The spherical nucleic acid (SNA) addresses some of the challenges of nucleic acid delivery without the need for extensive sequence modifications. In these structures, the oligonucleotides, DNA or RNA, are radially oriented around a spherical nanoparticle template. This dense three-dimensional arrangement improves DNA and RNA delivery by increasing nuclease resistance and accumulation in many cell types, through scavenger receptor engagement.16 In cellular assays, the SNA architecture increases the degradation half-life and cellular uptake in a sequence-dependent manner.17–19 SNA structures generated using modular nanoparticle cores such as liposomes can be tuned for greater tissue-specific delivery. For instance, in wild-type mice, SNAs are distributed on the basis of the DNA sequence’s affinity for the liposome core. Here, the hydrophobicity of the sterol or lipid anchoring the DNA sequences to the nanoparticle surface determines the number of SNAs that will be delivered to the liver, spleen, or lungs.19–21 SNAs also enhance the function of the nucleic acids compared to their equivalent linear form. Antisense oligonucleotides formulated into liposome-based SNAs enter cells and inhibit gene expression at micromolar concentrations.22,23 Consequently, SNAs delivering both DNA and RNA are showing promising results in the clinic.24–26

While clinically relevant activity is one requirement, nanocarriers must achieve sufficient delivery to the target while avoiding potentially harmful effects in other organs. Thus, a structure that can control the distribution and enhance the activity of the nucleic acids is needed. SNA architectures based on nanoparticles used for escape from cellular compartments may increase potency while retaining the SNA structure-dependent biodistribution properties. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are a modular class of nanoparticles that can effectively encapsulate many types of nucleic acids and rely on endogenous lipid-trafficking pathways for delivery.27 Advances in LNP chemistry enable siRNA and mRNA delivery at therapeutically relevant concentrations. For this reason, LNPs are the nanocarriers used in a variety of FDA approved RNA therapeutics.28 Although SNA architectures based upon LNP cores have the potential to deliver encapsulated nucleic acids at relevant concentrations as well as enhance tissue retention and sequence-specific targeting, they have yet to be synthesized and studied. To synergize the advantages of both LNPs and SNAs, a large parameter space of both LNP nanoparticle cores and DNA sequences must be explored. This requires an efficient optimization process as well as benchmarking LNP-SNA activity with that of previously studied SNAs and bare LNPs that have no surface-conjugated DNA. Finally, to assess the potential of LNP-SNAs as genetic medicines, it is necessary to determine how adding conjugated DNA to the surface of LNP-SNAs alters the activity and targeting ability in mice after intravenous injection.

Here, we report a strategy that employs Design of Experiment (DoE) methodologies29 such as definitive screening designs and fractional factorials to generate SNAs from LNP structures (LNP-SNAs). This approach hastens the discovery of optimal LNP-SNA formulations by reducing the number of conditions required to assess the effects of each factor and the two-factor effects. Large-scale experiments in the initial stages of LNP-SNA development are time- and material-prohibitive. For screening purposes, we synthesized LNP-SNAs with a 45 base-pair (bp) DNA sequence designed to bind cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS), activating the cytosolic cGAS-STING pathway. This pathway, while a useful proof-of-concept for DNA delivery to bind cytosolic proteins, is also therapeutically relevant.30,31 STING activation in the tumor microenvironment leads to a significant regression of solid tumors. Double-stranded (ds) DNA binding to cGAS leads to the activation of transcription factors such as IRF3.32–34 Thus, with a cell line engineered to secrete luciferase as a result of IRF3 induction, we can use luminescence as an output for DNA delivery.

RESULTS

LNP-SNA Synthesis and Library A Screening Using a Definitive Screening Design.

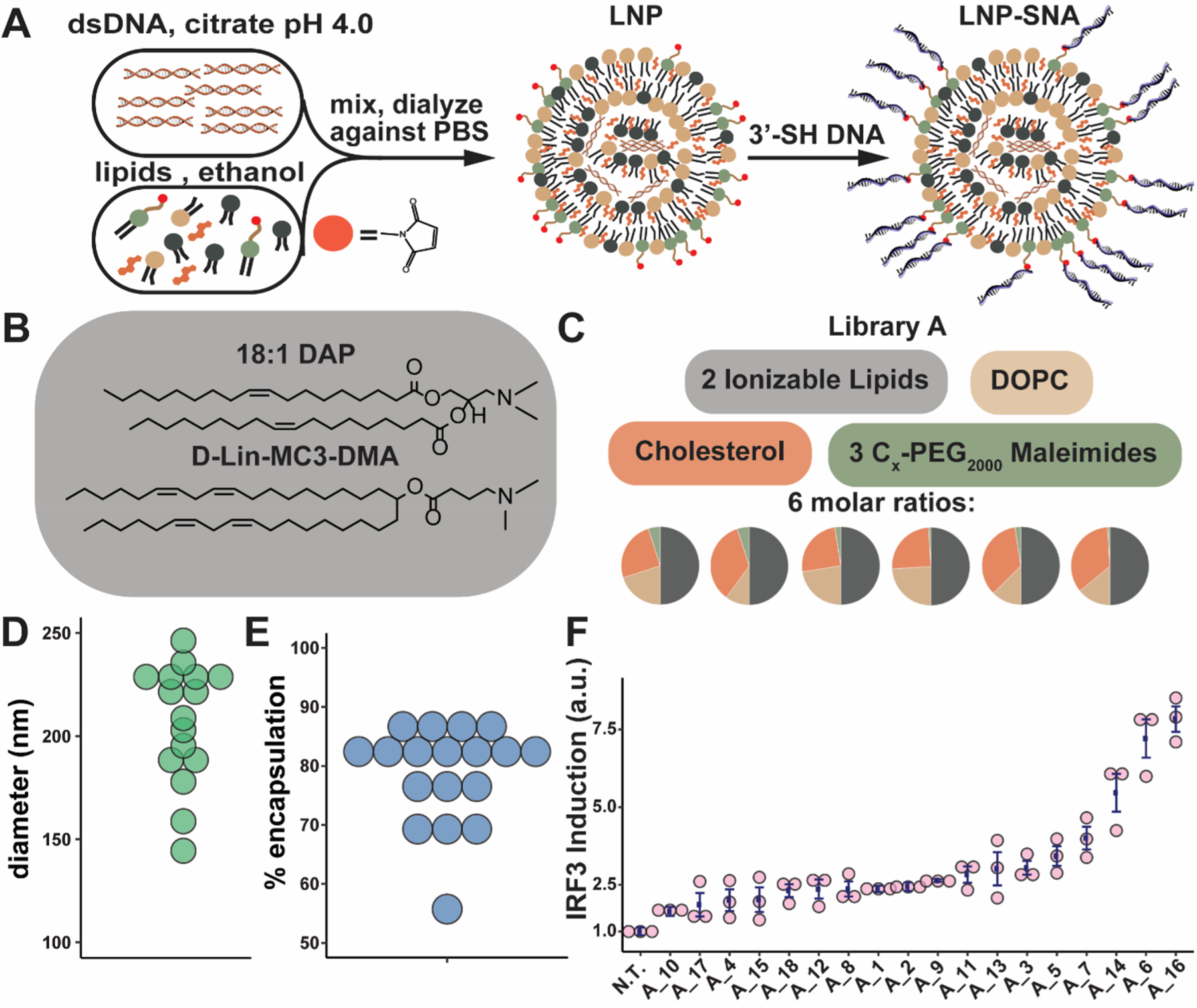

LNPs were synthesized using the ethanol dilution method,35 where the aqueous phase containing the nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 4) was mixed with the ethanol phase containing the various lipids, including an ionizable lipid (Figure 1A,B), phospholipid, lipid-PEG, and cholesterol (Figure 1C). The phospholipid is designed to support the structure and may aid in endosomal escape.36,37 The cholesterol enhances LNP stability and promotes the fusion of LNPs with biological membranes.38,39 The ionizable lipids are positively charged at endosomal pH, which aids in cytosolic delivery and nucleic acid loading.27,36,40–42 Lipid-PEGs are used to prevent nanoparticle aggregation and increase blood circulation times.27 Lipid-PEG(2000)-maleimides coat the surfaces of our LNPs and provide a conjugation site for sulfhydryl-terminated DNA. In library A, we used 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) as the phospholipid. In addition, we tested two different commercially available ionizable lipids, 1,2-dioleoyl-3-dimethylammonium-propane (18:1 DAP) and dilinoleylmethyl-4-dimethylaminobutyrate (DLin-MC3-DMA) (Figure 1B), and three different lipid-PEG(2000)-maleimides which differed in the length of the lipid’s diacyl tail (Figure 1C). Six different molar ratios of these components were used (Table S1).

Figure 1.

Characterization of LNP-SNA library A. (A) Synthesis of LNP-SNAs. LNPs loaded with nucleic acids are formed via the ethanol dilution method. DNA or mRNA dissolved in a pH 4.0 citrate buffer is mixed with lipids and cholesterol in ethanol. Next, the LNPs, which contain lipid-PEG-maleimides (red circles), are mixed with 3′-SH DNA (blue) overnight at RT, resulting in LNP-SNAs. DNA and LNPs are not drawn to scale. (B) Ionizable lipids used in library A. (C) library A components are mixed at six different molar ratios, and resulting LNPs are functionalized with a T21 DNA sequence. (D) Diameter of LNP-SNAs in library A. (E) Encapsulation efficiency of LNP-SNAs in library A. (F) IRF3 induction of each formulation in Raw 264.7-Lucia ISG cells treated for 24 h with 100 nM DNA (N.T. = not treated, error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3 biologically independent replicates).

Following dialysis against PBS, the diameter of the LNPs was characterized by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), and their encapsulation efficiency was determined using a fluorescence-based assay (Table S1). The LNP-SNAs in library A had a median hydrodynamic diameter of 221 nm (Figure 1D) and a median encapsulation efficiency of 82% (Figure 1E). To form SNAs from the LNPs, the LNPs were mixed with 3′-sulfhydryl-terminated DNA to facilitate conjugation to the surface-presented lipid-PEG(2000)-maleimides (Table S2). LNP-SNA formation was confirmed by agarose gel electro-phoresis (Figure S1). In library A, we used a poly(T) DNA sequence (T21-SH) because it does not form secondary structures. To confirm that the outer DNA sequence used to form LNP-SNA structures does not cause background cGAS-STING pathway activation, we transfected each DNA sequence used in screening experiments. Only the 45 bp dsDNA sequence specific for cGAS recognition resulted in detectable IRF3 induction (Figures S2 and S3).

To estimate both the main effects of each parameter and second-order effects between parameters, we employed a definitive screening design.29 This ensures that (1) the main effects are not confounded with two-factor effects, (2) we can detect nonlinear correlations, and (3) we can eliminate unimportant formulation parameters for subsequent screening experiments. The IRF3 induction screen of library A yielded five LNP-SNAs that significantly activated the cGAS-STING pathway (p < 0.05 compared to untreated (N.T.), Figure 1F). These five LNP-SNAs contained either C14 or C16 lipid-PEGs, 1–2.5% lipid-PEGs, and DLin-MC3-DMA as the ionizable lipid. These compositions are similar to those found in the LNP literature, where lower lipid-PEG mol % and shorter diacyl tails on lipid-PEGs often lead to greater activity.43,44 Additionally, DLin-MC3-DMA, one of the most frequently used lipids in clinical trials, is known to be effective for the delivery of siRNA and mRNA.41,45 From these findings, we eliminated unimportant compositions including the 18:1 DAP ionizable lipid and the C18 lipid-PEG and expanded the design space around the top five LNP-SNA formulations to create a second library.

Library B Screening Using a Fractional Factorial Design.

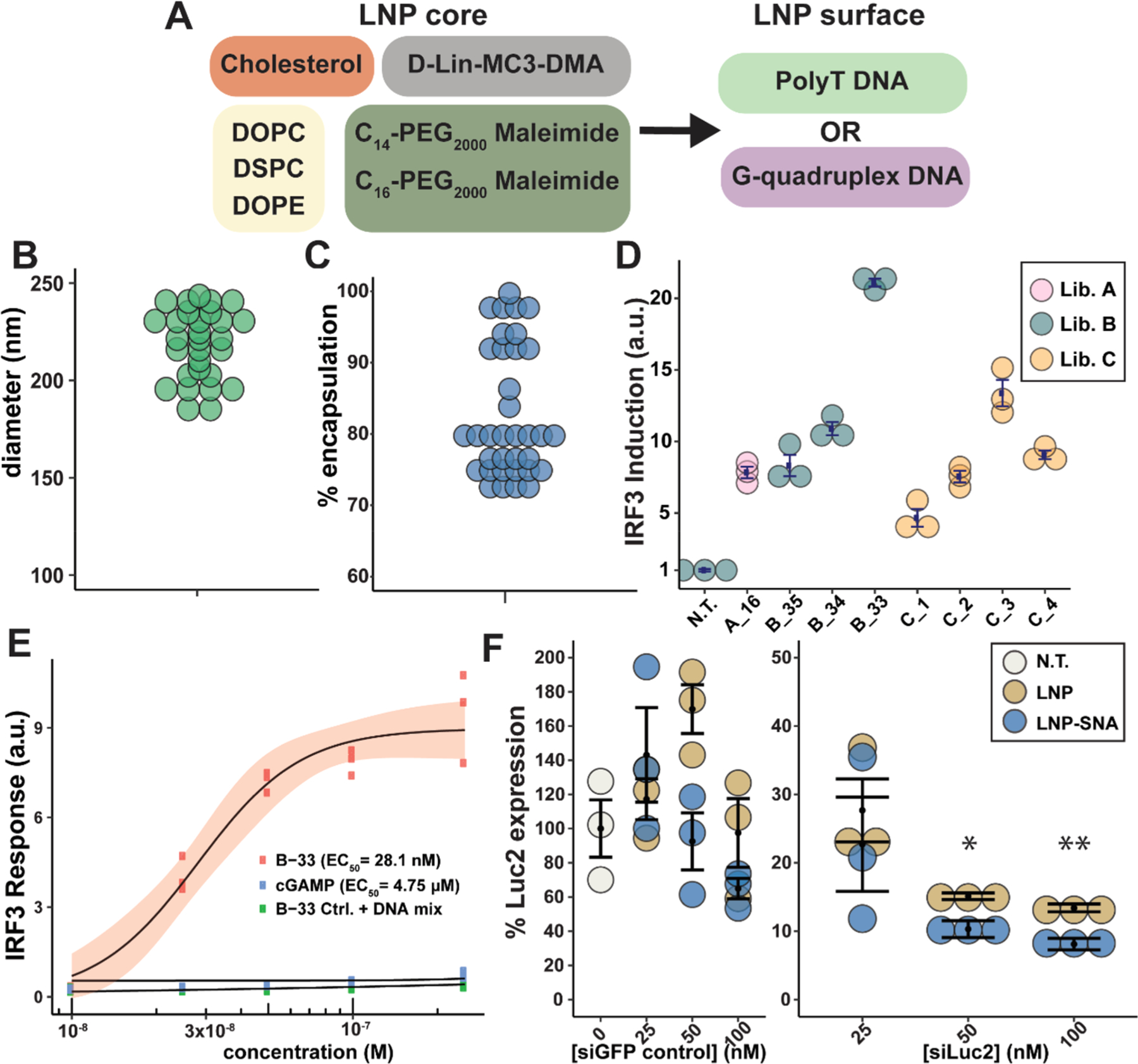

In library B, we investigated two additional phospholipids to test whether the structure of the phospholipid’s tail or head group changes the LNP-SNA function (Figure 2A). 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC) has the same headgroup as DOPC but has a saturated lipid tail. 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE) has a primary amine in its headgroup instead of the quaternary amine present in phosphatidylcholine. Because LNPs with shorter lipid-PEG-maleimides exhibited greater IRF3 induction, we limited library B to C14 and C16 maleimide-PEG(2000)-lipids. In addition to the T21-SH sequence, we included a G-rich (GGT × 7 -SH) DNA sequence, which forms a G-quadruplex secondary structure,46,47 as these structures are known to enhance the uptake of SNA structures via class A scavenger receptor-mediated endocytosis.18,47 We hypothesized that increasing the number of LNP-SNAs taken up by cells may lead to greater cytosolic delivery if LNP-SNAs of the same percent escape endosomal compartments. To test the effects of each component as well as their interactions, we designed a resolution IV fractional factorial experiment. The full factorial design contained 5 factors, 3 with 3 levels and 2 with 2 levels (3 × 3 × 3 × 2 × 2), or 108 possible LNP-SNA compositions. With a resolution IV fractional factorial experiment, only 37 of the 108 possible LNP-SNAs structures are required to estimate the main effects and 2-factor effects.

Figure 2.

DoE optimization process improves DNA and RNA delivery in vitro. (A) Core compositions and surface DNA sequences used in library B. (B) Diameter of library B LNPs. (C) Encapsulation efficiency of LNP-SNAs in library B. (D) IRF3 induction measured in a RAW 264.7-Lucia ISG cell line of candidates in libraries A–C normalized to untreated samples (error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3 biologically independent replicates). (E) IRF3 induction of B-33 LNP-SNA, 2′3′-cGAMP, and B-33 LNP-SNA mixed with free dsDNA (the red ribbon represents 95% C.I., n = 3 biologically independent replicates). (F) U87-Luc2 cells were treated for 24 h with LNPs or LNP-SNAs encapsulating a siGFP control sequence or a siLuc2 targeting sequence (error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3 biologically independent replicates, one-tailed t test comparing LNP and LNP-SNA, * = p ≤ 0.05, and ** = p ≤ 0.01).

LNP-SNAs in library B exhibited a median diameter of 229 nm (Figure 2B) and a median encapsulation efficiency of 79% (Figure 2C). As before, transfection was used to ensure that the surface-presented G-rich sequence does not activate the cGAS-STING pathway (Figure S3). The IRF3 induction of the LNP-SNAs in library B revealed that the highest-activating nanoparticle is B-33 (Figure S4), which contained 45 mol % cholesterol and the G-rich sequence. To evaluate which factors best predicted LNP-SNA activity, we used a bootstrap forest algorithm (Table S3). We found that, from highest to lowest portions, mol % cholesterol, DNA sequence, and mol % lipid-PEG were the three most important predictors of IRF3 induction (Table S4 and Figure S5). Increasing the mol % of cholesterol also had a positive interaction with lower levels of lipid-PEGs and for LNP-SNAs presenting the G-rich DNA sequence (Figure S6). The cholesterol may enhance the endosomal escape of LNP-SNAs through membrane fusion.48,49 The second most important predictor of activity in library B was the outer DNA sequence. Because of its secondary structure, the G-rich DNA sequence increases the uptake of the associated nanoparticles in SNA form compared to a poly(T) sequence,47,50 which may be responsible for this effect. The observed sequence-dependent function of LNP-SNAs bodes well for the future use of different DNA or RNA secondary structures to enhance LNP-SNA function and targeting.

Library C: One-at-a-Time Design.

A limitation of fractional factorial design is that the maximum activity obtained in the screening is a local maximum, not a global maximum. To determine whether B-33 is the global maximum of the design space in library B, we changed the lipid-PEG mol % and the phospholipid factors one at a time and observed whether the activity improved. Importantly, neither increased the activity, indicating that B-33 was in fact the maximum of this design (Figure 2D). With B-33 identified as the optimal design, we proceeded to benchmark its activity against the free DNA sequence and 2′3′-cGAMP, which activates STING downstream of cGAS and has been explored as a therapeutic. The median effective concentration (EC50) by the concentration of DNA in B-33 was 28.1 ± 2.9 nM, compared to 4.75 ± 0.13 μM for 2′3′-cGAMP (Figure 2E). As a control for nonspecific activation from the delivery vehicle, we compared B-33 to the same formulation with an encapsulated T45 control sequence mixed with free STING dsDNA. We observed no nonspecific IRF3 induction from B-33 structures without the encapsulated STING agonist.

siRNA Delivery with cGAS-STING Pathway Induction Optimized LNP-SNAs.

While the cGAS-STING pathway was a useful screening tool for LNP-SNA optimization, we sought to more thoroughly benchmark nanoparticle activity using gene silencing. We quantified the activity of LNP-SNAs containing the siRNA silencing luciferase gene (Luc2) as a model system. One of the benefits of LNPs is that they can effectively encapsulate a variety of nucleic acid cargos, including siRNA, mRNA, and Cas9 mRNA/single-guide RNA.45,51,52 Because differently sized nucleic acids may be packaged differently within LNPs-SNAs, we performed an initial test using the top five LNP-SNAs from Libraries B and C. The test revealed that a slightly different structure, B-35 (Table S1), silenced Luc2 the most without affecting cell viability (Figure S7). Therefore, we tested B-35 over a range of concentrations. In a U87-MG-Luc2 cell line, B-35 effectively silenced the constitutive Luc2 expression by up to 92% after 24 h and at a concentration of as low as 25 nM (Figure 2F). While the surface-presented G-rich DNA sequence had a significant effect on cGAS-STING pathway activation versus the poly(T) sequence, we sought to determine whether LNP-SNAs enhance the activity of the equivalent LNP. At the same siRNA treatment concentration, the B-35 LNP-SNA increased the gene-silencing activity of the equivalent LNP by ~5% at 50 nM (p < 0.05) and 100 nM (p < 0.01) siRNA concentrations (Figure 2F).

LNP-SNAs Exhibit Spleen-Specific mRNA Expression.

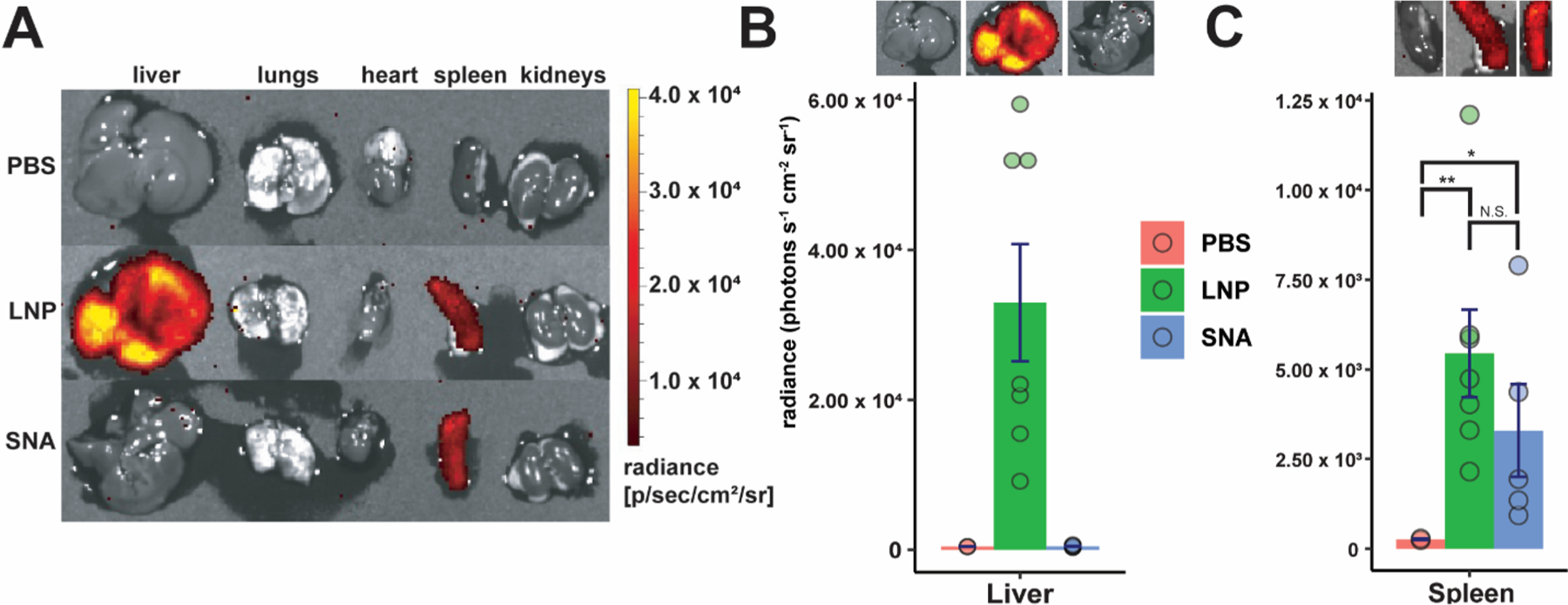

Finally, we investigated the ability of these designs to deliver nucleic acids in vivo. For this, we used luciferase (Luc) mRNA so that we could detect luciferase protein production after the injection of d-luciferin. Since the mRNA sequence is much longer than either the siRNA or the 45-bp STING DNA sequence, it may be packaged differently within LNP-SNA formulations. For this reason, we quantified the mRNA encapsulation efficiencies of the top three LNP-SNA candidates from the cGAS-STING pathway activation screening (B-19, B-33, and B-35). Of the three, B-19 exhibited the greatest encapsulation efficiency (Table S5), lowest polydispersity (Figure S8), and a zeta potential of −1.46 ± 0.44 mV. Therefore, we used this formulation to evaluate Luc mRNA expression 6 h after the intravenous injection of LNPs and LNP-SNAs into C57BL/6J mice (0.1 mg kg−1). Comparing LNPs to LNP-SNAs, we observed significant differences in organ-level mRNA expression. In the liver, we observed that B-19 LNPs exhibited high levels of Luc mRNA expression, while the equivalent LNP-SNA had no expression (Figure 3A,B). In the spleen, however, both LNPs and LNP-SNAs exhibited roughly equal levels of mRNA expression (Figure 3C, N.S., two sample t tests), although both exhibited significantly greater expression than the control PBS-treated mice. Differences between LNP and LNP-SNA functional distribution may be due to the differences in receptors used for the endocytosis of each nanoparticle. LNP uptake is largely mediated by the LDL receptor,53 while SNA uptake is mainly mediated by class A scavenger receptors,54,55 which recognize DNA. Because highly phagocytic cells in the liver are responsible for the sequestration of injected nanoparticles,56–58 differences in the accumulation of LNPs and SNAs in these cell types are likely the cause of these differences. We have previously observed a sequence-dependent biodistribution with gold-based SNA structures. With the same poly(T) and G-rich DNA motifs used in this communication, we observed greater accumulation of SNAs with G-rich DNA sequences in the liver and spleen shortly after injection, as well as different proteins coating the nanoparticle surface.19,47 To determine whether spleen-specific mRNA expression is dependent on the sequence present on the LNP-SNA surface, we compared poly(T) LNP-SNAs to G-rich LNP-SNAs. We observed spleen-specific mRNA expression only in the G-rich LNP-SNA structures (Figure S9), suggesting that this is a G-rich DNA-specific effect.

Figure 3.

LNP-SNAs effectively deliver mRNA with organ-specific function. (A) Luc mRNA expression in major organs by treatment. Luminescence was detected in harvested organs 6 h after the administration of 0.1 mg kg−1 Luc mRNA. (B, C) LNP-SNAs exhibit organ-specific function in the context of mRNA expression. Luminescence was detected in harvested organs 6 h after the administration of 0.1 mg kg−1 Luc mRNA. (One-tailed student’s t test, * = p < 0.05, each dot represents a biologically independent replicate, with 4–7 biologically independent replicates per treatment).

DISCUSSION

Synthesizing LNP-SNAs with a library of different compositions allows for multivariate analysis of the effects of both the sequence and lipid nanoparticle composition. We have observed that both the surface-presented DNA sequence and the LNP composition determine the activity of LNP-SNAs in cellular assays. From screening a series of LNP-SNA libraries, we determined that the mol % cholesterol and DNA sequence were the two most important predictors of cytosolic delivery. While we initially screened libraries of LNP-SNA structures for the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway mediated by dsDNA delivery, nanoparticles that were able to encapsulate dsDNA were also effective at delivering similarly sized siRNA. Compared to the liposomal SNA,22,23 LNP-SNAs demonstrated a 100-fold reduction in the oligonucleotide concentration required to achieve gene silencing. In addition, LNP-SNAs increased gene silencing by 5% compared to the bare LNP with no DNA on its surface in cellular assays.

The optimized LNP-SNA formulations from in vitro screening were modified to encapsulate a larger, ~2 kb mRNA encoding firefly luciferase (Luc). We identified an LNP-SNA formulation that was able to effectively encapsulate Luc mRNA while producing detectable mRNA expression in C57BL/6 mice. LNP-SNAs functionalized with G-quadruplex DNA exhibited organ-selective function in the spleen while avoiding the high degree of liver mRNA expression shown from the bare LNP. This effect is possibly due to the influence of G-quadruplexes on the proteins that adsorb to nanoparticle structures. We have previously observed that G-rich SNA structures have more total protein adsorbed to their surfaces, and the composition of the protein corona also changes.47 This shift in the protein corona toward proteins such as factor H and C3b enhances the uptake of G-quadruplex containing SNAs into macrophages in cellular assays.19 Because organs such as the spleen contain many cell types that take up materials via the complement pathway,59,60 this may be partially responsible for this effect.

Organ-specific mRNA expression observed using LNP-SNAs bodes well for applications such as delivering a mixture of single-guide RNA (sgRNA) and mRNA coding for a base editor. Others have measured high levels of off-target edits in both RNA and DNA with base editors,61–63 thus the use of a carrier with organ-specific activity may increase safety and efficacy. Specifically, targeting the spleen has the potential to use mRNA for genome editing in important cell populations which regulate the immune response to pathologies such as cancers.64 Future studies are necessary to elucidate the immune cell populations in which LNP-SNAs have the greatest editing efficiency in vivo. We envision that the structure-dependent biodistribution and activity of LNP-SNAs may become a powerful tool for creating safer and more efficacious genetic medicines.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under awards R01CA208783 and P50CA221747. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. J.P. was supported in part by the Chicago Cancer Baseball Charities and the H Foundation at the Lurie Cancer Center of Northwestern University, M.E. was partially supported by the Dr. John N. Nicholson Fellowship, and Z.H. acknowledges support by the Northwestern University Graduate School Cluster in Biotechnology, Systems, and Synthetic Biology, which is affiliated with the Biotechnology Training Program funded by NIGMS grant T32 GM008449.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c01973.

Materials and methods, list of nanoparticle formulations, list of DNA sequences used, general nanoparticle characterization data, control experiments for library A and B screening experiments, statistical analysis of library B screening, mRNA LNP-SNA characterization, and other mRNA expression data (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c01973

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Jungsoo Park, International Institute for Nanotechnology and Interdisciplinary Biological Sciences Graduate Program, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States;.

Ziyin Huang, International Institute for Nanotechnology and Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States;.

Chad A. Mirkin, International Institute for Nanotechnology and Department of Chemistry, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States;.

REFERENCES

- (1).Whitehead KA; Langer R; Anderson DG Knocking down Barriers: Advances in SiRNA Delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2009, 8, 129–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).McCaffrey AP; Meuse L; Pham TTT; Conklin DS; Hannon GJ; Kay MA RNA Interference in Adult Mice. Nature 2002, 418, 38–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Morrissey DV; Lockridge JA; Shaw L; Blanchard K; Jensen K; Breen W; Hartsough K; Machemer L; Radka S; Jadhav V; Vaish N; Zinnen S; Vargeese C; Bowman K; Shaffer CS; Jeffs LB; Judge A; MacLachlan I; Polisky B Potent and Persistent in Vivo Anti-HBV Activity of Chemically Modified SiRNAs. Nat. Biotechnol 2005, 23, 1002–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Elbashir SM; Harborth J; Lendeckel W; Yalcin A; Weber K; Tuschl T Duplexes of 21-Nucleotide RNAs Mediate RNA Interference in Cultured Mammalian Cells. Nature 2001, 411, 494–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Doudna JA; Charpentier E The New Frontier of Genome Engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 2014, 346, 1258096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Wang HX; Li M; Lee CM; Chakraborty S; Kim HW; Bao G; Leong KW CRISPR/Cas9-Based Genome Editing for Disease Modeling and Therapy: Challenges and Opportunities for Nonviral Delivery. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 9874–9906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Sander JD; Joung JK CRISPR-Cas Systems for Editing, Regulating and Targeting Genomes. Nat. Biotechnol 2014, 32, 347–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hajj KA; Whitehead KA Tools for Translation: Non-Viral Materials for Therapeutic MRNA Delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater 2017, 2, 17056. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Sahin U; Karikó K; Türeci Ö mRNA-Based Therapeutics-Developing a New Class of Drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2014, 13, 759–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Motwani M; Pesiridis S; Fitzgerald KA DNA Sensing by the CGAS–STING Pathway in Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Genet 2019, 20, 657–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Ishii KJ; Coban C; Kato H; Takahashi K; Torii Y; Takeshita F; Ludwig H; Sutter G; Suzuki K; Hemmi H; Sato S; Yamamoto M; Uematsu S; Kawai T; Takeuchi O; Akira S A Toll-like Receptor-Independent Antiviral Response Induced by Double-Stranded B-Form DNA. Nat. Immunol 2006, 7, 40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Stetson DB; Medzhitov R Recognition of Cytosolic DNA Activates an IRF3-Dependent Innate Immune Response. Immunity 2006, 24, 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kim E; Yang J; Park J; Kim S; Kim NH; Yook JI; Suh JS; Haam S; Huh YM Consecutive Targetable Smart Nanoprobe for Molecular Recognition of Cytoplasmic MicroRNA in Metastatic Breast Cancer. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 8525–8535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Park YK; Jung WY; Park MG; Song SK; Lee YS; Heo H; Kim S Bioimaging of Multiple PiRNAs in a Single Breast Cancer Cell Using Molecular Beacons. MedChemComm 2017, 8, 2228–2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Ke G; Wang C; Ge Y; Zheng N; Zhu Z; Yang CJ L-DNA Molecular Beacon: A Safe, Stable, and Accurate Intracellular Nano-Thermometer for Temperature Sensing in Living Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 18908–18911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Choi CHJ; Hao L; Narayan SP; Auyeung E; Mirkin CA Mechanism for the Endocytosis of Spherical Nucleic Acid Nanoparticle Conjugates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2013, 110, 7625–7630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Rosi NL; Giljohann DA; Thaxton CS; Lytton-Jean AKR; Han MS; Mirkin CA Oligonucleotide-Modified Gold Nanoparticles for Intracellular Gene Regulation. Science (Washington, DC, U. S.) 2006, 312, 1027–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Cutler JI; Auyeung E; Mirkin CA Spherical Nucleic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 1376–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Chinen AB; Guan CM; Ko CH; Mirkin CA The Impact of Protein Corona Formation on the Macrophage Cellular Uptake and Biodistribution of Spherical Nucleic Acids. Small 2017, 13, 1603847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Jensen SA; Day ES; Ko CH; Hurley LA; Luciano JP; Kouri FM; Merkel TJ; Luthi AJ; Patel PC; Cutler JI; Daniel WL; Scott AW; Rotz MW; Meade TJ; Giljohann DA; Mirkin CA; Stegh AH Spherical Nucleic Acid Nanoparticle Conjugates as an RNAi-Based Therapy for Glioblastoma. Sci. Transl. Med 2013, 5, 209ra152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ferrer JR; Sinegra AJ; Ivancic D; Yeap XY; Qiu L; Wang JJ; Zhang ZJ; Wertheim JA; Mirkin CA Structure-Dependent Biodistribution of Liposomal Spherical Nucleic Acids. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 1682–1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Banga RJ; Chernyak N; Narayan SP; Nguyen ST; Mirkin CA Liposomal Spherical Nucleic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 9866–9869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Sprangers AJ; Hao L; Banga RJ; Mirkin CA Liposomal Spherical Nucleic Acids for Regulating Long Noncoding RNAs in the Nucleus. Small 2017, 13, 1602753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Exicure announces data for topical anti-TNF compound AST-005 in patients with mild to moderate psoriasis https://investors.exicuretx.com/news/news-details/2018/Exicure-Announces-Data-for-Topical-Anti-TNF-Compound-AST-005-in-Patients-with-Mild-to-Moderate-Psoriasis/default.aspx (accessed Sept 5, 2019).

- (25).Exicure, Inc. Reports Full Year 2018 Financial Results and Corporate Progress https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1698530/000169853019000014/a8k3819exhibit991.htm (accessed Sept 5, 2019).

- (26).Kumthekar P; Ko CH; Paunesku T; Dixit K; Sonabend AM; Bloch O; Tate M; Schwartz M; Zuckerman L; Lezon R; Lukas RV; Jovanovic B; McCortney K; Colman H; Chen S; Lai B; Antipova O; Deng J; Li L; Tommasini-Ghelfi S; Hurley LA; et al. A First-in-Human Phase 0 Clinical Study of RNA Interference-Based Spherical Nucleic Acids in Patients with Recurrent Glioblastoma. Sci. Transl. Med 2021, 13, No. eabb3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Maier MA; Jayaraman M; Matsuda S; Liu J; Barros S; Querbes W; Tam YK; Ansell SM; Kumar V; Qin J; Zhang X; Wang Q; Panesar S; Hutabarat R; Carioto M; Hettinger J; Kandasamy P; Butler D; Rajeev KG; Pang B; et al. Biodegradable Lipids Enabling Rapidly Eliminated Lipid Nanoparticles for Systemic Delivery of RNAi Therapeutics. Mol. Ther 2013, 21, 1570–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Rizk M; Tüzmen Ş Update on the Clinical Utility of an RNA Interference-Based Treatment: Focus on Patisiran. Pharmacogenomics Pers. Med 2017, 10, 267–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Montgomery DC Two-Level Fractional Factorial Designs. In Design and Analysis of Experiments, 8th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, 2013; pp 320–393. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Corrales L; Glickman LH; McWhirter SM; Kanne DB; Sivick KE; Katibah GE; Woo SR; Lemmens E; Banda T; Leong JJ; Metchette K; Dubensky TW; Gajewski TF Direct Activation of STING in the Tumor Microenvironment Leads to Potent and Systemic Tumor Regression and Immunity. Cell Rep. 2015, 11, 1018–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Yum S; Li M; Frankel AE; Chen ZJ Roles of the CGAS-STING Pathway in Cancer Immunosurveillance and Immunotherapy. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol 2019, 3, 323–344. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Ishikawa H; Barber GN STING Is an Endoplasmic Reticulum Adaptor That Facilitates Innate Immune Signalling. Nature 2008, 455, 674–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Sun L; Wu J; Du F; Chen X; Chen ZJ Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase Is a Cytosolic DNA Sensor That Activates the Type I Interferon Pathway. Science (Washington, DC, U. S.) 2013, 339, 786–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Chen Q; Sun L; Chen ZJ Regulation and Function of the CGAS-STING Pathway of Cytosolic DNA Sensing. Nat. Immunol 2016, 17, 1142–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Akinc A; Zumbuehl A; Goldberg M; Leshchiner ES; Busini V; Hossain N; Bacallado SA; Nguyen DN; Fuller J; Alvarez R; Borodovsky A; Borland T; Constien R; de Fougerolles A; Dorkin JR; Narayanannair Jayaprakash K; Jayaraman M; John M; Koteliansky V; Manoharan M; et al. A Combinatorial Library of Lipid-like Materials for Delivery of RNAi Therapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol 2008, 26, 561–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Kanasty R; Dorkin JR; Vegas A; Anderson D Delivery Materials for SiRNA Therapeutics. Nat. Mater 2013, 12, 967–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Zuhorn IS; Bakowsky U; Polushkin E; Visser WH; Stuart MCA; Engberts JBFN; Hoekstra D Nonbilayer Phase of Lipoplex-Membrane Mixture Determines Endosomal Escape of Genetic Cargo and Transfection Efficiency. Mol. Ther 2005, 11, 801–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Allen TM; Cullis PR Liposomal Drug Delivery Systems: From Concept to Clinical Applications. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2013, 65, 36–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Lu JJ; Langer R; Chen J A Novel Mechanism Is Involved in Cationic Lipid-Mediated Functional SiRNA Delivery. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2009, 6, 763–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Semple SC; Akinc A; Chen J; Sandhu AP; Mui BL; Cho CK; Sah DWY; Stebbing D; Crosley EJ; Yaworski E; Hafez IM; Dorkin JR; Qin J; Lam K; Rajeev KG; Wong KF; Jeffs LB; Nechev L; Eisenhardt ML; Jayaraman M; et al. Rational Design of Cationic Lipids for SiRNA Delivery. Nat. Biotechnol 2010, 28, 172–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Jayaraman M; Ansell SM; Mui BL; Tam YK; Chen J; Du X; Butler D; Eltepu L; Matsuda S; Narayanannair JK; Rajeev KG; Hafez IM; Akinc A; Maier MA; Tracy MA; Cullis PR; Madden TD; Manoharan M; Hope MJ Maximizing the Potency of SiRNA Lipid Nanoparticles for Hepatic Gene Silencing in Vivo. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51, 8529–8533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Love KT; Mahon KP; Levins CG; Whitehead KA; Querbes W; Dorkin JR; Qin J; Cantley W; Qin LL; Racie T; Frank-Kamenetsky M; Yip KN; Alvarez R; Sah DWY; De Fougerolles A; Fitzgerald K; Koteliansky V; Akinc A; Langer R; Anderson DG Lipid-like Materials for Low-Dose, in Vivo Gene Silencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2010, 107, 1864–1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Sago CD; Lokugamage MP; Islam FZ; Krupczak BR; Sato M; Dahlman JE Nanoparticles That Deliver RNA to Bone Marrow Identified by in Vivo Directed Evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 17095–17105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Lokugamage MP; Sago CD; Gan Z; Krupczak BR; Dahlman JE Constrained Nanoparticles Deliver SiRNA and SgRNA to T Cells In Vivo without Targeting Ligands. Adv. Mater 2019, 31, 1902251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Cheng Q; Wei T; Farbiak L; Johnson LT; Dilliard SA; Siegwart DJ Selective Organ Targeting (SORT) Nanoparticles for Tissue-Specific MRNA Delivery and CRISPR-Cas Gene Editing. Nat. Nanotechnol 2020, 15, 313–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Pearson AM; Rich A; Kriegers M Polynucleotide Binding to Macrophage Scavenger Receptors Depends on the Formation of Base-Quartet-Stabilized Four-Stranded Helices. J. Biol. Chem 1993, 268, 3546–3554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Chinen AB; Guan CM; Mirkin CA Spherical Nucleic Acid Nanoparticle Conjugates Enhance G-Quadruplex Formation and Increase Serum Protein Interactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2015, 54, 527–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Arteta MY; Kjellman T; Bartesaghi S; Wallin S; Wu X; Kvist AJ; Dabkowska A; Székely N; Radulescu A; Bergenholtz J; Lindfors L Successful Reprogramming of Cellular Protein Production through MRNA Delivered by Functionalized Lipid Nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2018, 115, E3351–E3360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Pozzi D; Marchini C; Cardarelli F; Amenitsch H; Garulli C; Bifone A; Caracciolo G Transfection Efficiency Boost of Cholesterol-Containing Lipoplexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr 2012, 1818, 2335–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Kusmierz CD; Bujold KE; Callmann CE; Mirkin CA Defining the Design Parameters for in Vivo Enzyme Delivery through Protein Spherical Nucleic Acids. ACS Cent. Sci 2020, 6, 815–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Ramishetti S; Hazan-Halevy I; Palakuri R; Chatterjee S; Naidu Gonna S; Dammes N; Freilich I; Kolik Shmuel L; Danino D; Peer D A Combinatorial Library of Lipid Nanoparticles for RNA Delivery to Leukocytes. Adv. Mater 2020, 32, 1906128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Kauffman KJ; Mir FF; Jhunjhunwala S; Kaczmarek JC; Hurtado JE; Yang JH; Webber MJ; Kowalski PS; Heartlein MW; DeRosa F; Anderson DG Efficacy and Immunogenicity of Unmodified and Pseudouridine-Modified MRNA Delivered Systemically with Lipid Nanoparticles in Vivo. Biomaterials 2016, 109, 78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Akinc A; Querbes W; De S; Qin J; Frank-Kamenetsky M; Jayaprakash KN; Jayaraman M; Rajeev KG; Cantley WL; Dorkin JR; Butler JS; Qin L; Racie T; Sprague A; Fava E; Zeigerer A; Hope MJ; Zerial M; Sah DW; Fitzgerald K; et al. Targeted Delivery of RNAi Therapeutics with Endogenous and Exogenous Ligand-Based Mechanisms. Mol. Ther 2010, 18, 1357–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Patel PC; Giljohann DA; Daniel WL; Zheng D; Prigodich AE; Mirkin CA Scavenger Receptors Mediate Cellular Uptake of Polyvalent Oligonucleotide-Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010, 21, 2250–2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).PrabhuDas MR; Baldwin CL; Bollyky PL; Bowdish DME; Drickamer K; Febbraio M; Herz J; Kobzik L; Krieger M; Loike J; McVicker B; Means TK; Moestrup SK; Post SR; Sawamura T; Silverstein S; Speth RC; Telfer JC; Thiele GM; Wang X-Y; et al. A Consensus Definitive Classification of Scavenger Receptors and Their Roles in Health and Disease. J. Immunol 2017, 198, 3775–3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Ouyang B; Poon W; Zhang YN; Lin ZP; Kingston BR; Tavares AJ; Zhang Y; Chen J; Valic MS; Syed AM; MacMillan P; Couture-Senécal J; Zheng G; Chan WCW The Dose Threshold for Nanoparticle Tumour Delivery. Nat. Mater 2020, 19, 1362–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Zhang YN; Poon W; Tavares AJ; McGilvray ID; Chan WCW Nanoparticle–Liver Interactions: Cellular Uptake and Hepatobiliary Elimination. J. Controlled Release 2016, 240, 332–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Proffitt RT; Williams LE; Presant CA; Tin GW; Uliana JA; Gamble RC; Baldeschwieler JD Liposomal Blockade of the Reticuloendothelial System: Improved Tumor Imaging with Small Unilamellar Vesicles. Science (Washington, DC, U. S.) 1983, 220, 502–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Nagayama S; Ogawara K.-i.; Fukuoka Y; Higaki K; Kimura T Time-Dependent Changes in Opsonin Amount Associated on Nanoparticles Alter Their Hepatic Uptake Characteristics. Int. J. Pharm 2007, 342, 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Taylor PR; Martinez-Pomares L; Stacey M; Lin HH; Brown GD; Gordon S Macrophage Receptors and Immune Recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol 2005, 23, 901–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Rees HA; Liu DR Base Editing: Precision Chemistry on the Genome and Transcriptome of Living Cells. Nat. Rev. Genet 2018, 19, 770–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Grünewald J; Zhou R; Garcia SP; Iyer S; Lareau CA; Aryee MJ; Joung JK Transcriptome-Wide off-Target RNA Editing Induced by CRISPR-Guided DNA Base Editors. Nature 2019, 569, 433–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Zhou C; Sun Y; Yan R; Liu Y; Zuo E; Gu C; Han L; Wei Y; Hu X; Zeng R; Li Y; Zhou H; Guo F; Yang H Off-Target RNA Mutation Induced by DNA Base Editing and Its Elimination by Mutagenesis. Nature 2019, 571, 275–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Khalil DN; Smith EL; Brentjens RJ; Wolchok JD The Future of Cancer Treatment: Immunomodulation, CARs and Combination Immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 2016, 13, 273–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.