Abstract

When it emerged in late 2019, COVID-19 was carried via travelers to Germany, France and Italy, where freedom of movement accelerated its transmission throughout Europe. However, effective non-pharmaceutical interventions introduced by European governments led to containment of the rapid increase in cases within European nations. Electronic searches were performed to obtain the number of confirmed cases, incident rates and non-pharmaceutical government measures for each European country. The spread and impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions throughout Europe were assessed and visualized. Specifically, heatmaps were used to represent the number of confirmed cases and incident rates for each of the countries over time. In addition, maps were created showing the number of confirmed cases and incident rates in Europe on three different dates (15 March, 15 April and 15 May 2020), which allowed us to assess the geographic and temporal patterns of the disease.

Keywords: COVID-19, Europe, non-pharmaceutical interventions, pandemic, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

A lethal viral pneumonia initially linked to animal-to-human transmission was first reported in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)1 and resulting in a disease now more commonly known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The WHO declared COVID-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on 30 January 2020.2 Imported cases to European Union (EU) countries via travelers from countries outside Europe contributed to the disease spreading in EU countries. The Maastricht Treaty (1993) guaranteed free movement for the citizens of Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, the UK and all European signatory countries, and this freedom of movement led to an acceleration in transmission of the disease throughout Europe. The earliest imported confirmed cases (in Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden and the UK) were reported in January 2020.3–6 COVID-19 spread rapidly through Lombardy and then into Lombardy's neighbors of Piedmont, Veneto and Emilia-Romagna.7 Because the ski resort of Ischgl was identified as the focus of Austria's COVID-19 outbreak, Austrian authorities introduced restrictions on the Italian border and placed Ischgl under quarantine, to contain the spread of the outbreak.8–10 The Nordic countries of Denmark, Norway and Iceland also experienced cases resulting from tourists returning from Ischgl.11 Furthermore, a late suspension of European sporting events contributed to the rapid spread of the disease. For example, 2500 Valencia fans traveled to Milan to attend a Champions League football match at the very moment Lombardy was the European epicenter of COVID-19.12 Consequently, one third of the team and staff returning to Valencia tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.13 Additionally, Spanish scientists analyzing SARS-CoV-2 from Spain identified the Atlanta and Valencia football match as the most likely origin of the Spanish outbreak.14 The late response of the UK government to closing their borders led to 1356 independent SARS-CoV-2 lineages arriving in the UK. The majority of these early COVID-19 introductions came from three EU countries, namely, Italy, Spain and France.15 Here, we conducted detailed searches of COVID-19 cases through electronic databases, local government websites and newspapers to elucidate a granular narrative and history regarding the emergence of COVID-19 in Europe in 2019 and its subsequent spread across the continent in 2020.

Methodology

Electronic searches were undertaken to obtain daily cases that were then transformed to incident cases using PubMed and Google Scholar, as well as government websites and newspapers in English and local European languages. The searches consisted of two terms used in combination utilizing the format ‘Term 1’ AND ‘Term 2’. Term 1 included ‘Covid-19’, ‘coronavirus’, ‘epidemic’, ‘pandemic’ and ‘outbreak’. Term 2 included ‘interventions’, ‘measures’, ‘cases’ and ‘case fatality’. COVID-19 data were gathered from 20 February 2020 to 31 May 2020 from EU countries, as well as the UK, Norway, Switzerland and Iceland. Daily cases were then transferred to incidence rates per 100 000 people. Government measures are included in the figures with case numbers to determine their impact on COVID-19 virus transmission in each country. Countries were categorized according to geographical region: southwest Europe; northern Europe: Germany and Nordic; the UK and The Republic of Ireland; Alps mountains: Austria, Switzerland and Liechtenstein; northwest Europe: The Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg; Baltic; central Europe; and Greece, Cyprus and Balkan. We created a graph for countries of low population. Countries with a population greater than 1.5 million were compared with their neighbors in a single graph. We visualized COVID-19 data by using heatmaps representing the number of confirmed cases and incidence rates for each of the countries over time. We also created maps showing the numbers of confirmed cases and incidence rates in Europe on three different dates (15 March, 15 April and 15 May 2020), which enabled us to assess the geographic and temporal patterns of the disease. Plots were created with the R package ggplot2.16

The entry of COVID-19 into European countries

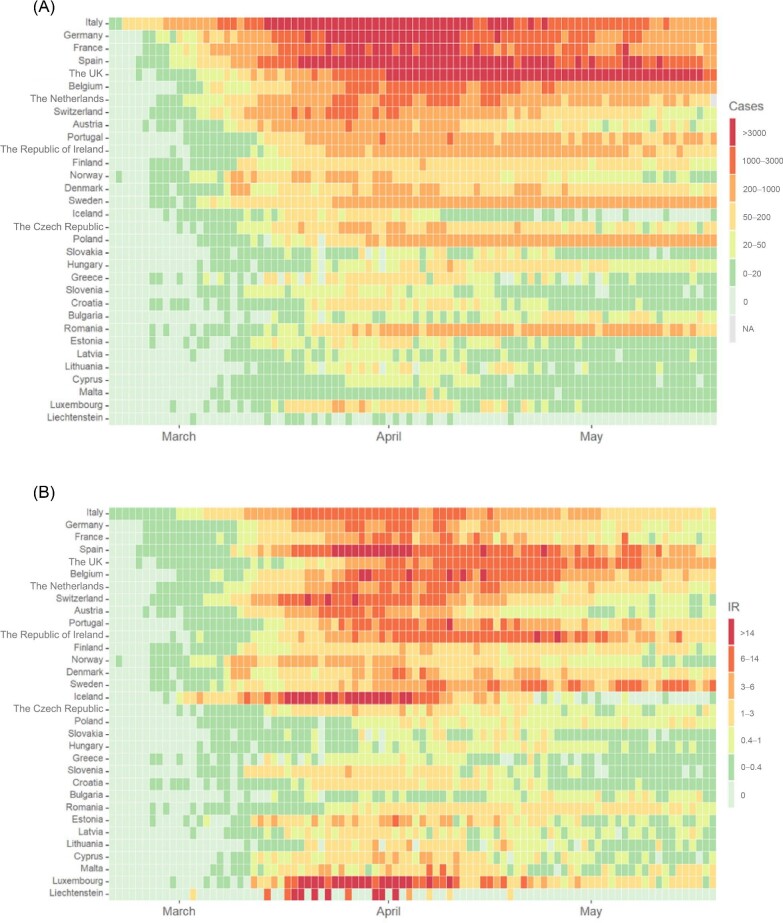

Prior to the Chinese travel restrictions introduced by European countries, multiple Chinese COVID-19 cases were introduced into Italy, France, Germany, the UK and Spain. Although the first reported local cases began in Italy in the second half of February, silent transmission is assumed to have begun earlier than that date. The disease spread dramatically in Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, Belgium, Luxembourg and Iceland (Figure 1). COVID-19 entered central Europe and the Balkan states 1–2 wk after the first reported cases in western Europe. It is assumed that COVID-19 entered Poland, The Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, Greece, Slovenia, Croatia, Bulgaria and Romania from western European countries (Figure 1). COVID-19 also arrived in the Nordic countries (Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway and Estonia) earlier than in their neighbors Latvia and Lithuania.

Figure 1.

Heatmaps representing (A) the number of confirmed cases per 100 000 people and (B) incidence rates (IR) in Europe.

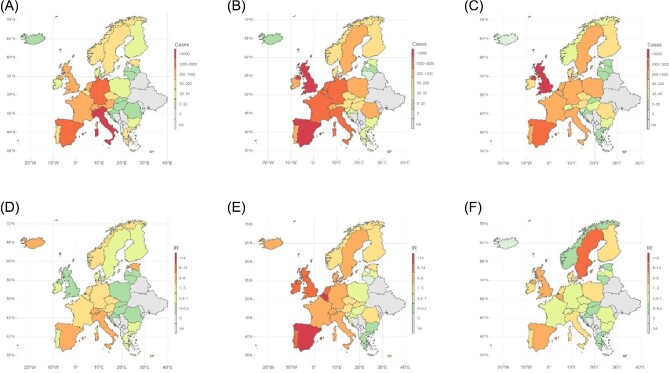

Three time points are shown on the map for COVID-19 outbreaks in European countries; during mid-March, COVID-19 particularly affected western Europe, while it appears that COVID-19 had not yet affected central Europe and the Balkans to the same extent (Figure 2). By mid-April, European countries from western to central Europe and the Balkans were under strict measures, consisting of either lockdown or strict social distancing measures, or a combination of both. By mid-May the European countries had started to contain COVID-19. The incidence rate declined to <5 cases per 100 000 people in all European countries by mid-May, with the exceptions of the UK and Spain (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Maps representing the number of confirmed cases per 100 000 people on (A) 15 March, (B) 15 April and (C) 15 May 2020 and incidence rates (IR) on (D) 15 March, (E) 15 April and (F) 15 May 2020 in Europe.

The impact of COVID-19 measures on European countries

Four central European countries—Poland, The Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia—successfully intervened early to contain COVID-19, leading to very low levels of virus circulation. Similarly, Greece, Cyprus, Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia and Slovenia introduced measures during the first week of detected cases in each country to minimize the impact of the virus. Latvia, Lithuania and the Balkan countries responded early and succeeded in controlling COVID-19, while Estonia responded within 2 wk of the first cases and also succeeded in effectively containing the virus. In western Europe, The Netherlands, Belgium, Luxemburg, Austria and Switzerland all introduced strict measures during the third week after the first detected cases of COVID-19, while cases were increasing rapidly. Although the Nordic countries, Denmark, Finland, Norway and Iceland, only responded in the third week of the pandemic, each effectively flattened the epidemiological curve. By contrast, Sweden relied on softer and less stringent measures, while cases remained high. Germany introduced measures gradually and contained the virus effectively. In the UK, strict government measures were not introduced until 5 wk after the first week of detected cases. On the neighboring Republic of Ireland, the virus was effectively contained with an earlier intervention. The European region most badly affected by COVID-19 consisted of the southwestern countries, namely, France, Italy and Spain. Both silent transmission and a late response led to rapid increases of cases in Italy and France while the late response in Spain led to one of the worst COVID-19 outbreaks in Europe.

Southwestern European countries

After Italy reported its first local cases on 20 February, cases increased dramatically, to the extent that Italy became the epicenter of the pandemic in Europe.17,18 Of Italy's population of 60 million, 23% are aged >65 y and, despite all the efforts made to contain the increase of COVID-19, there were >34 000 deaths in Italy after 110 d of the pandemic.17 France, with the largest population in southwest Europe, introduced measures 3 wk after the first cases,18 but deaths reached >30 000 among the French population by the end of the first wave.19 In Portugal, 22.4% of its 10.28 million inhabitants are aged >65 y.20 The Portuguese relied on early intervention to contain COVID-19 and thus avoided a catastrophic situation among their older population.20,21 By contrast, Spain introduced strict measures only after 8000 cases had been reported, at a point when there had been 300 deaths out of a population of 47 million (Supplementary Figure 1).22 Malta, to the south of Italy in the Mediterranean Sea, introduced intervention measures early in the first week of reported cases. Restrictions at the borders were applied and all returning travelers, along with people who had developed symptoms, were required to self-isolate.23,24 Public events were cancelled and schools were closed.25 Further measures were introduced, in which social distancing was applied and the whole of Malta was placed under quarantine.26,27 The Maltese epidemiological curve then flattened and cases decreased to <1 per 100 000 people (Supplementary Figure 2).28

After a cluster of cases broke out in the town of Codogno, Italian authorities placed the town under quarantine, in an attempt to contain the pandemic,7 but this did not prevent cases from increasing dramatically in Lombardy.17 The Italian government then ordered the quarantine of three Northern regions (Lombardy, Veneto and Emilia-Romagna) in an attempt to control their epidemiological curve. A rapid increase in COVID-19 cases led to the introduction of strict measures. Social distancing measures were introduced and mandated, public gatherings were cancelled and schools and universities were closed, while further restrictions at the border were introduced and returning travelers were asked to quarantine. People with COVID-19 symptoms were also required to self-isolate. The government then decided to introduce a national lockdown to contain the pandemic.17 Following the introduction of a national lockdown, 2 wk were required to flatten the epidemiological curve.29 Face masks were then made compulsory, bringing the number of cases down to 5 per 100 000 people within 2 wk (Supplementary Figure 1).30 The French government responded during the third week of the first detected cases of COVID-19 by cancelling public events.31 Then schools and universities were closed, further travel restrictions were introduced and all returning travelers were asked to self-isolate.31,32 Suspected cases were home-isolated and social distancing was introduced. A national lockdown was then introduced to contain the rapid increase in cases.33 After the lockdown was imposed, it took 1 wk to flatten the epidemiological curve (Supplementary Figure 1). Furthermore, a level of just 5 COVID-19 cases per 100 000 people was achieved after 2 wk of lockdown.19

Thousands attended the Women's Day parade in early March in Madrid, as well as Spanish football league matches, which continued to be held until COVID-19 cases were reported among players and spectators.34 The Spanish government then decided to cancel all public events in an attempt to control the sharp increase in cases. Spain introduced further restrictions at its borders, social distancing measures were applied and schools and universities were closed.35 A national lockdown was introduced to contain the virus.35,36 The Spanish government flattened the epidemiological curve after 3 wk of national lockdown. Cases then declined to <5 per 100 000 people after 8 wk of strict measures (Supplementary Figure 1).22 This relatively late Spanish intervention led to a catastrophic situation, where 250 000 COVID-19 cases and 28 385 deaths were reported after 110 d of the pandemic, approximately half of which were reported in care homes (Supplementary Figure 1).22,37 By contrast, Portugal introduced strict measures at a point when only 112 cases had been reported, thus became successful at containing COVID-19 transmission.38 Social distancing measures were introduced and all public events were cancelled.21 Schools and universities were closed at a national level and further restrictions were applied at the border.39,40 Further measures were introduced as Portugal went into national lockdown.20 Portugal controlled the epidemiological curve after 3 wk of national lockdown. Cases then went below 5 per 100 000 people (achieving an average of just 2 COVID-19 cases per 100 000 people after 7 wk of strict measures [Supplementary Figure 1]).38 These early Portuguese interventions resulted in 43 659 cases after 110 d of the pandemic, with just 1605 deaths reported among one of the highest populations of older people in the world (Supplementary Figure 1).38

Germany and the Nordic countries

Germany, with Europe's largest population (83 million), introduced measures gradually.41 The government asked all people with symptoms to self-isolate, and then the German authorities cancelled all major public events to contain the virus, which had spread throughout North Rhine–Westphalia.30,41,42 Cases increased during the third week after the first detected cases of COVID-19, whereupon the German government closed schools and universities.43 Although the government introduced measures in an effort to contain super-spreader events in the first 3 wk, cases nevertheless continued to increase rapidly after 3 wk of the pandemic.42 The government then decided to introduce further restrictions at the border, along with stricter social distancing, and a national lockdown was undertaken to contain the epidemiological curve.41,42,44 After the introduction of these strict measures, Germany flattened its COVID-19 epidemiological curve in 1 wk, and after 2 wk the number of cases was reduced to <5 per 100 000 people.42 Furthermore, a federal law was introduced to make the wearing of face masks compulsory in public places.30 Among 83 million Germans, 9000 deaths have occurred and 200 000 cases of COVID-19 have been reported from the first case to the end of the first wave (Supplementary Figure 3).42

To the north of Germany, where the Nordic countries are situated, different approaches were taken to contain COVID-19. Denmark reported a higher number of deaths compared with Norway and Finland, with 10.14 deaths per 100 000 people (Supplementary Figure 4). Denmark, Norway, Finland and Iceland all introduced strict measures from the third week of the appearance of COVID-19. However, Sweden decided to impose fewer restrictions, so that university and upper secondary school students transferred to distance learning, while primary and lower secondary school pupils were allowed to continue as normal (Supplementary Figure 4).45 Nordic countries introduced restrictions on borders and public events were cancelled. Schools and universities were closed from the third week onwards of the pandemic in all four of the Nordic countries.46–58 In Denmark, whose population is approximately 6 million, a national lockdown was introduced after a rapid increase in cases during the third week after the first detected cases of COVID-19.46–48,55 The Danish lockdown brought the virus under control after 3 wk. Furthermore, the Danish lockdown and other control measures led to achieving <2 cases per 100 000 people.55

The Finnish government was also successful, being able to control the epidemiological curve at a level of <4 cases per 100 000 people. Denmark, which was more seriously affected by virus transmission, with the curve reaching 8 per 100 000 people. Finland introduced a regional lockdown in Uusimaa, where the country's highest population density and capital city are situated.52,53,57,58 Three weeks after the Uusimaa quarantine was imposed, the epidemiological curve had flattened, and after 8 wk, cases had been reduced to 1 per 100 000 people (Supplementary Figure 4). After the fifth week, Finland introduced quarantine conditions for everyone aged >70 y, as Finland has one of the highest populations of older people in the world.52,57 Although 22.1% of the Finnish population are aged >65 y, the government succeeded in protecting many older people, as just 5.9 deaths per 100 000 were reported.53 More than 5 million Norwegians were placed under a quarantine order with other control measures applied in the third week after the first detected cases of COVID-19. These measures were highly effective and the epidemiological curve was flattened within 2 wk of the intervention (Supplementary Figure 1).49–51 The incidence rate reached <1 per 100 000 people after 6 wk of lockdown.56 These interventions were applied to minimize the impact of circulation of the virus and, consequently, the number of deaths among Norwegians was 4.5 per 100 000, which was relatively low compared with its neighbor Finland (Supplementary Figure 4).

In Iceland, situated in the North Atlantic with a population of only 360 000, various measures were introduced during the third week after the first detected cases of COVID-19. Self-isolation was necessary for all returning travelers and all public events were cancelled. Secondary school and university students were instructed to study from home.59–61 After the fourth week, the epidemiological curve increased rapidly when cases were detected among tourists, returning travelers and their contacts, and therefore the government introduced stricter border measures. Several deaths occurred in Vestmannaeyjar, off the south coast of Iceland, leading to the introduction of stricter measures on that island.62,63 Stricter social distancing measures were also introduced to contain the rapid increase in COVID-19 cases.64 After the Vestmannaeyjar quarantine, and the introduction of stricter border measures and social distancing measures, the epidemiological curve was brought under control within 2 wk. A level of 1 case per 100 000 people was achieved after 4 wk of the application of these stricter measures (Supplementary Figure 5).53,64,65

In complete contrast to its Nordic neighbors, Sweden decided to opt for fewer restrictions, aiming to achieve herd immunity, a strategy which intended that at least 55% of the population would develop antibodies.66,67 Limited public gatherings, with <50 participants, were permitted, even although public gatherings had been banned by Sweden's Nordic neighbors.68 Primary schools were closed, while secondary schools and universities were ordered to switch to online learning.45 The Swedish epidemiological curve rose to 5–8 cases per 100 000 people69 and, consequently, Sweden reported the worst COVID-19 virus transmission among the Nordic nations, with 49 deaths per 100 000 people reported after 110 d of the pandemic. This figure is far in excess of the equivalent figures for Denmark (10.14 per 100 000), Finland (5.9) and Norway (4.5).

The UK and The Republic of Ireland

Unlike the UK, The Republic of Ireland, with approximately 5 million inhabitants, introduced social distancing the second week after the first reported cases, closing schools and universities while cases still numbered <100. Public events were banned to keep the number of cases at a low level.70–72 Because the government noticed an increase in COVID-19 cases, they introduced further restrictions at the border and required all returning travelers and those who developed symptoms to self-isolate.73 Although early intervention measures were applied, the number of cases nevertheless continued to increase rapidly.71,74 A national lockdown was then introduced to control the pandemic, even before the country had reported 1000 cases.71,74 Four weeks of lockdown were required to flatten the epidemiological curve.74 Cases then declined after 5 wk to less than an average of 5 cases per 100 000 people. The Republic of Ireland thus controlled COVID-19 and reported 1742 deaths after 110 d of the pandemic (Supplementary Figure 6).71,74

The UK response to COVID-19 pandemic was very slow and late.71 The UK government started with a ‘herd immunity’ strategy similar to Sweden's, but pivoted soon after to suppression due to a public backlash against that policy. The British authorities asked people who developed symptoms to voluntarily self-isolate in the third week after the first detected cases of COVID-19.75 They stopped testing and tracing symptomatic individuals on 12 March. They took the decision to cancel public events very late, following an increase in cases, and this was followed by the introduction of social distancing and the closure of schools and universities.76 After approximately 8500 cases were reported, the government decided to introduce a national lockdown to contain the rapid increase in transmission.77,78 This late government response made controlling the epidemiological curve much more difficult, so that it took 5 wk to control the virus, leading to one of the worst death rates among European countries.79 The delayed response led to >44 000 deaths in the first wave of the pandemic (Supplementary Figure 6).79

Austria, Switzerland and Liechtenstein

Although Switzerland intervened earlier than Austria, cases increased in Switzerland almost twofold compared with Austria (Supplementary Figure 7).80,81 Liechtenstein, situated between Austria and Switzerland, with a population of only 38 000, reported a sudden increase in COVID-19 cases.82 Liechtenstein responded immediately in the third week, with the introduction of restrictions at the border and by asking all returning travelers to self-isolate. Public events were cancelled and all schools were closed. Social distancing was applied and all older people were advised to stay at home.83,84 It took 1 wk to flatten the epidemiological curve and control the virus, such that cases were reduced to <1 per 100 000 people after 3 wk of measures (Supplementary Figure 8).82 In Austria, with 8.86 million inhabitants, restrictions were introduced at the beginning of the third week after the first detected cases of COVID-19, with border restrictions, the closure of schools and universities and the cancellation of all public events.85,86 A quarantine was imposed in Tyrol, where the Alpine ski resorts are located, to contain the dramatic increase in cases among the local population.10 Social distancing was applied and a national lockdown was introduced to contain the sudden increase in cases.80,85,87,88 Once the Austrian government applied these measures, it took 2 wk to control the epidemiological curve (Supplementary Figure 7).80 Five weeks after the national lockdown was imposed, the Austrian government had contained the virus and cases were reduced to <1 per 100 000 people, with 705 deaths after 110 d of the pandemic.80,85

Switzerland, home to most of the United Nation institutions in Europe, was highly affected by COVID-19. Following the first reported cases, the Swiss government cancelled public events and all returning travelers were asked to self-isolate.89–91 However, cases increased in the second week, whereupon the government decided to close schools and introduced further border restrictions.90,92 Although the government introduced these measures, a dramatic increase occurred in the third week, and so they decided to introduce social distancing measures and place the country under quarantine.89,90,92 After 2 wk, the epidemiological curve was still showing >10 cases per 100 000 people (Supplementary Figure 7).81,93 Switzerland reported <1 case per 100 000 people 8 wk after the national lockdown order and 1685 deaths were reported after 110 d of the pandemic.93

The Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg

Although The Netherlands and Luxembourg reported COVID-19 cases earlier than Belgium, Belgium recorded one of the worst rates of COVID-19 cases and deaths among all European countries.94,95 COVID-19 cases increased rapidly during the third week after the first detected cases of COVID-19 in all three countries.94–96 Strict government interventions were introduced 3 wk after the first reported cases.97 The Netherlands, with >17 million inhabitants, was not convinced by the introduction of a strict lockdown, and so an ‘intelligent lockdown’ was introduced instead.98 Moreover, The Netherlands government decided to introduce strict social distancing measures in North Brabant to contain the rapid increase in COVID-19 cases.97,98 The Netherlands then introduced various measures at national level to contain COVID-19.96,97 These national measures were introduced in the third week (while The Netherlands was reporting 5 cases per 100 000 people) and led to a flattening of the epidemiological curve (Supplementary Figure 9).97 The Netherlands implemented strict social distancing measures in the fourth week of the pandemic and the curve started to decline, 3 wk after their first intervention. Thereafter, there was <1 case per 100 000 people and the government decided to ease restrictions and reopen schools.99 Although The Netherlands eventually contained the virus, they reported relatively high mortality rates among the population, of 35 deaths per 100 000 people after 110 d of the pandemic.94

Belgium, with 11 million inhabitants, intervened during the second week after the first reported cases, while the country was reporting <2 COVID-19 cases per 100 000 people.100 Although the country imposed a national lockdown, rapid increases in case numbers were recorded in the fourth, fifth and sixth weeks of the pandemic.95,100 Although the government contained that rapid increase after 3 wk of national lockdown, Belgium reported one of the worst death rates, with >85 deaths per 100 000 people after 110 d of the pandemic.101 Effective government measures to contain COVID-19 cases then led to the country having <2 cases per 100 000 people after 8 wk of national lockdown, and the government decided to ease restrictions 10 wk after the first reported cases (Supplementary Figure 9). Belgium's neighbor, Luxembourg, was also highly affected by COVID-19. Cases increased rapidly during the second week of the pandemic, at which point the government decided to introduce non-pharmaceutical measures to contain the virus.102–104 A national lockdown was implemented in the third week after the first reported cases, when a sharp increase occurred. Transmission was then contained after 2 wk of government measures. Then, 6 wk after national lockdown, Luxembourg achieved <1 case per 100 000 people (Supplementary Figure 10) and decided to ease lockdown after 7 wk of restrictions.105

Baltic countries

The Baltic countries of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia successfully flattened their epidemiological COVID-19 curves by means of early and effective interventions.106–108 Their records of very low mortality led to them being considered as among the most successful in controlling COVID-19. Latvia, with 1.9 million inhabitants, introduced early intervention measures while cases numbered <100.109 All returning travelers were required to self-isolate, all public gatherings were banned and border restrictions were introduced.110,111 During the fourth week, Latvia decided to introduce even stricter social distancing measures to reduce the COVID-19 curve, bringing cases down to <1 per 100 000 people, which was achieved after just 1 wk of stricter social distancing.112 Latvia's early intervention was intended to avoid overwhelming local health facilities. Latvia has 450 ICU beds, with the capacity to utilize a further 1500 beds during the pandemic to alleviate the ICU bed shortage.113 While the Latvian government was planning for the worst, these effective measures led to a low level of viral circulation among the community and a very low number of COVID-19 cases, with just 1110 reported during 110 d of the pandemic (Supplementary Figure 11).106

The Lithuanian government also intervened effectively at an early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, with similarly successful results. From the first week after the first reported cases, public events were banned, all returning travelers were asked to self-isolate, schools were closed, border restrictions were imposed and social distancing was introduced.107,110,114–117 A nationwide quarantine was announced during the first weeks of the pandemic, to avoid the number of cases increasing.118 Transmission was effectively contained in Lithuania, where 1–2 cases were reported per 100 000 people.115 However, the Lithuanian government was not satisfied by those achievements and so wearing a face mask was made compulsory during the fourth week of the pandemic. This effectively suppressed the epidemiological curve to <1 case per 100 000 within 2 wk of the face-mask ruling (Supplementary Figure 11).119 Estonia, with 1.329 million inhabitants, intervened in the third week after the first reported cases, while Lithuania and Latvia had intervened in the first and second week after the first reported cases, respectively.108,120 The Estonian intervention followed a sudden increase in COVID-19 cases in the third week. Further restrictions on travel were installed at the Estonian border, all returning travelers were required to self-isolate, public events were cancelled, all care home visits were banned and schools were closed.121,122 Social distancing measures were introduced during the following week. Quarantine was introduced in the regions of Saaremaa and Muhumaa due to the sudden increase in COVID-19 cases (Supplementary Figure 11).123

Central Europe

Poland, The Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia also successfully controlled COVID-19 transmission through very early intervention measures. In Poland, with approximately 38 million inhabitants, the following early intervention measures were taken: school closures, social distancing and partial lockdown, self-isolation for all returning travelers and tighter border restrictions.124,125 Poland's stringent early interventions were made while the country was still reporting <100 cases, enabling the epidemiological curve to be maintained at a very low level, with an average of 1 case per 100 000 people.124,125 Six weeks after the first case, wearing a face mask covering became compulsory in public places in Poland, which led to keeping the epidemiological curve at an average of 1 case per 100 000 people.126 Thus virus transmission was contained, with 1680 deaths reported after 110 d (Supplementary Figure 12).124,127,128

The Czech Republic decided to cancel all public events and to close all schools as early intervention measures, prior to the country reporting 100 cases.129,130 The Czech Republic thus prevented the spread of COVID-19 among its 10.7 million people and the government introduced social distancing measures and a national lockdown before they reported 300 cases.129–131 Further to these measures, The Czech Republic made the wearing of face masks compulsory in all public places.130–132 With the application of all these measures, The Czech Republic took just 3 wk to crush the epidemiological curve, keeping numbers below 1 case per 100 000 people, as shown in Supplementary Figure 12. Consequently, the number of COVID-19 deaths was very low compared with most other European countries, and just 336 deaths were reported after 110 d of the pandemic (Supplementary Figure 12).133

Hungary introduced a range of measures prior to reporting 100 COVID-19 cases.134 All returning travelers were asked to self-isolate and further restrictions were introduced at the borders. Public events were cancelled and all schools were closed, in addition to the introduction of social distancing measures.135–137 Further to these measures, the Hungarian government also introduced a national lockdown 3 wk after the first reported cases, which flattened Hungary's COVID-19 curve, reducing cases to an average of 1 per 100 000 people during the pandemic.138 The Hungarian government made wearing a face mask compulsory after 7 wk of the pandemic, prior to a gradual easing of restrictions.139,140 This resulted in only 4100 cases and just 572 deaths reported after 110 d of the pandemic among 9.773 million Hungarians (Supplementary Figure 12).

Strict and early intervention led Slovakia to success in confining COVID-19 cases to just 1588 after 110 d of the pandemic, with 28 deaths reported.141,142 Prior to reporting 100 cases, Slovakia had already closed schools and cancelled all public events, while all returning travelers were asked to self-isolate, restrictions were introduced at the borders and the country entered quarantine.143,144 In addition, wearing a face mask was made compulsory in public places from the third week onwards of the pandemic.145 Furthermore, the Slovakian government introduced a lockdown on the Roma communities and active surveillance was carried out to contain the transmission of COVID-19.146,147 After the first Slovakian case, the epidemiological curve was reduced to an average of <1 case per 100 000 people.141 Although Slovakia eased restrictions after 8 wk of the pandemic, they reported a very low level of incidence per 100 000 people (Supplementary Figure 12).141

Greece, Cyprus and the Balkan countries

Early intervention measures were applied in Greece, the southern Balkans, Croatia and Slovenia in the northwest Balkans, Romania and Bulgaria in the eastern Balkans and Cyprus in the Mediterranean Sea, leading in all cases to very low levels of COVID-19. The epidemiological curves for these countries remained below an average of 2 cases per 100 000 people.148–152 Greece has one of the world's largest populations of older people (21.9% of 10.72 million Greeks are aged >65 y) and it was one of the most successful countries in containing COVID-19 transmission.148 Greece introduced travel restrictions prior to reporting 100 cases.153 Then further restrictions were applied: social distancing was introduced, schools and universities were closed, all returning travelers were asked to self-isolate and all public gatherings were banned. The northern city of Kozani, where deaths were reported, was placed under quarantine to control the spread of infection.148,154–157 The whole country was placed under national lockdown before Greece reported 1000 cases.158 Refugee camps were also placed under quarantine once cases were detected among refugees.159 These measures helped Greece to flatten the epidemiological curve, with the average number of weekly cases remaining <1 per 100 000 people (Supplementary Figure 13).148 In Cyprus, with just over 1 million inhabitants, restrictive measures were introduced from the first week, with the cancellation of all public events and the closure of all schools.160,161 However, the number of cases continued to increase, forcing the government to introduce further border restrictions during the third week of the pandemic,162,163 followed by social distancing, and eventually all of Cyprus was placed in lockdown.161,164 These measures led to the flattening of Cyprus's epidemiological curve, immediately after lockdown.162,164 COVID-19 cases decreased to <1 per 100 000 people after 2 wk of lockdown (Supplementary Figure 14).162

Croatia, with 4.08 million inhabitants, closed schools and all returning travelers were asked to self-isolate, prior to reporting 100 cases.165,166 However, a sudden increase in cases forced the Croatian government to introduce further measures and a national lockdown before 400 cases had been reported.167,168 One week of these measures flattened the epidemiological curve. Although a further sudden increase occurred, the average number of weekly cases remained <2 cases per 100 000 people (Figure 15).149 Slovenia, which borders Italy, introduced border restrictions from the first week to protect 2 million Slovenians from the virus crossing the Slovenian–Italian border close to where COVID-19 had first emerged in Europe.169 Furthermore, the Slovenian government cancelled all public events.170 However, 1 wk after the first reported case, the epidemiological curve increased sharply.150 The Slovenian government responded immediately, by closing schools and universities and introducing social distancing.170–172 Although these measures were applied, an uncontrollable increase in case numbers forced the government to impose a national lockdown during the third week.170,173 Wearing a face mask was then made compulsory in public indoor places from the fourth week of the pandemic.174 Slovenia flattened its epidemiological curve once wearing a face mask was made compulsory and the lockdown was imposed, along with other measures. The number of cases then declined to <2 per 100 000 people and then after 2 wk dropped again to <1 per 100 000 people (Supplementary Figure 13).150

Romania, with 19 million inhabitants, imposed several measures before 100 cases had been reported: social distancing was applied, all public events were cancelled and schools and universities were closed.175–177 Further restrictions were introduced at the borders and all returning travelers were asked to self-isolate.178 The Romanian government imposed a national lockdown to control the epidemiological curve at the point when 1258 cases had been reported.151,179 After the lockdown was introduced, it took 4 wk to flatten the curve. A level of 1 case per 100 000 people was reached after 6 wk of national lockdown. These measures led to 1600 deaths among its 19 million people after 110 d of the pandemic (Supplementary Figure 15).

The Bulgarian government decided to impose early intervention measures although <100 cases had been reported.152,180 Travel restrictions were introduced, public gatherings were cancelled and social distancing was applied.180,181 The government decided to close schools and universities when cases rose to >200.182 Wearing a face mask was made compulsory indoors in public places during the fifth week of the pandemic.183 Restrictions were imposed in the Bulgarian capital of Sofia, which was placed under lockdown.184 Once all these measures had been introduced, it took 2 wk to flatten the epidemiological curve. Very low incidence was reported after 5 wk of the pandemic, with just 219 deaths after 110 d of the pandemic among its 7 million people (Supplementary Figure 15).152

Discussion and Conclusion

More than 500 y ago, human plague originated in China, before Mongol armies brought Black Death across central Asia into the Crimea via ancient Silk Road routes. From there it entered Sicily before spreading across Europe.185 Similarly, human movement from China to European countries 2020 initiated the first European COVID-19 foci. Additionally, free movement between European countries exacerbated the spread of COVID-19 among EU countries, as well as the UK, Switzerland, Norway and Iceland.186 In January 2020, COVID-19 was carried by travelers from China to Italy, Germany and France.5,19,187,188 Italy was the original epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak in Europe. COVID-19 cases were introduced from Italy to neighboring countries.15,17 The majority of COVID-19 cases introduced to Spain were associated with travelers returning from Italy.12 Moreover, multiple COVID-19 introductions from Italy, Spain and France resulted in the first COVID-19 cases in the UK.15 Furthermore, free movement between European countries led to rapid virus transmission throughout European countries. Late travel restrictions imposed by the Spanish government were possibly a major factor behind the introduction of multiple COVID-19 cases to Spain, whereas early government intervention by the Portuguese government (including travel restrictions and closing the border with Spain) controlled the level of virus transmission in Portugal.20,36

National lockdowns proved a very effective measure in all European countries where they were applied. European countries took 1–4 wk to apply a lockdown, resulting in a flattening of the epidemiological curve in all cases. Social distancing, school closures, cancellation of all public gatherings and national lockdowns all helped to flatten the COVID-19 epidemiological curve. Germany, France, Italy, Austria, Switzerland, Norway and Estonia all reported >5 cases per 100 000 people during the peak of the pandemic, but each was able to flatten the epidemiological curve in <3 wk.17,19,42,55,80,81,108 However, Spain, The Netherlands, Belgium, Portugal and Denmark, where >5 COVID-19 cases per 100 000 were reported during the peak of the pandemic, each took >3 wk of lockdown to flatten the epidemiological curve.22,38,55,94,95 Similarly, it took 4 wk for each of the UK and The Republic of Ireland to flatten the epidemiological curve.74,79 Thus, Europe's most severe COVID-19 epidemics resulted when virus transmission was allowed to accelerate for weeks before implementing lockdown or other containment measures. Similar observations were made for Chinese urban areas in January 2020, where the severity of hospital surges was determined by how quickly lockdown measures were implemented following virus importation.189 Such findings may also explain the devastating COVID-19 epidemic in New York City in March–April 2020, where virus transmission went undetected for weeks following its importation from Europe in early February.190

A high incidence of COVID-19 cases was recorded in several European countries, each with a population of <1 million. Luxembourg, Iceland and Liechtenstein each reported an average of 10–25 weekly cases because of the effect of COVID-19 on their relatively small populations.54,82,104 Two weeks of strict measures led to a flattening of the epidemiological curve in Luxembourg, Iceland and Liechtenstein.61,83,104 By contrast, Malta, with 0.5 million inhabitants, effectively restricted the number of cases to <5 per 100 000.23,26,28,191 Effective and early government response measures in some Nordic and Baltic countries (Finland, Norway, Latvia and Lithuania) led to a low weekly average number of cases during the European peak, with <5 per 100 000 people reported.49,53,56,57,106,107,118,192 Once strict government measures were applied, Finland and Norway reported <2 cases per 100 000 people, while <1 case per 100 000 was recorded in Latvia and Lithuania.48,56,112,118

Notably, wearing a face mask was made compulsory in public places in central Europe and the Balkans, which led to very low numbers of average weekly cases.126,129,145,174,183 In the central European countries of Poland, The Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia, as well as in the Balkan countries of Slovenia and Bulgaria, 1–2 cases per 100 000 people were reported during the European peak.124,126,133,141,150,152 Compulsory face mask wearing was introduced in The Czech Republic and Slovakia 2 wk after the first reported cases.129,145 Slovenia reported zero cases after very effective government measures in the first 3 wk, then introduced compulsory face mask wearing as an additional control measure 3 wk after the first cases.174,193 Furthermore, compulsory face mask wearing proved effective when introduced in Italy 6 wk after the first reported cases, which led to other government measures to contain COVID-19 in Italy.30 Compulsory face mask wearing was introduced in Germany 8 wk after the first reported cases, which led to limiting the number of cases to <1 per 100 000 people 3 wk after their introduction.30

The European countries with the highest percentages of older people (aged ≥65 y) are Italy (23%), Portugal (22.4%), Finland (22.1%), Greece (21.9%), Germany (21.6%), Bulgaria (21.3%), Croatia (20.9%), Malta (20.8%), France (20.4%) and Latvia (20.3%), followed by Sweden, Slovenia and Lithuania (all 20.2%), then Estonia and Denmark (both 20%).194 Effective and early intervention helped Portugal, Finland and Greece to curb the mortality rate among their older people.20,57,148 Finland introduced quarantine conditions for people aged >70 y, while Sweden reported a very high mortality rate among its older people.57,58,66,69 The Swedish government attempted a strategy with fewer restrictions and prevented care home visits in an attempt to address the mortality rate.45,66,68,69 Moreover, the sudden increase in COVID-19 cases in Italy led to a high mortality rate among older people.17 Although Spain (19.6%) and the UK (18.5%) have populations with <20% of people aged >65 y, their mortality rates were the highest among European countries as a consequence of their late interventions.22,79,194

The strategies adopted by countries in regard to containing COVID-19 are diverse. Successful East Asian countries like South Korea and Taiwan relied on the closure of their borders with China early in the pandemic instead of implementing lockdowns. Moreover, enhancing laboratory testing capability helped early case identification. Modern technology was implemented during the isolation of COVID-19 patients to help trace their contacts. Although Japan recorded the highest number of deaths in older people, the overall number of deaths related to COVID-19 was very low. Japan, without active surveillance and limited COVID-19 testing, contained the pandemic and eased lockdown measures. Very well designed strategies in the southern hemisphere countries Australia and New Zealand, where all imported cases and their contacts were traced under national lockdowns, accelerated containment of COVID-19; 62% of cases in Australia were imported while 70% of total cases in New Zealand were either imported or were related to imported cases. Early identification of imported cases supported Australia and New Zealand in rapid containment of COVID-19. COVID-19 laboratory testing enhanced active surveillance, identifying symptomatic and asymptomatic cases in New Zealand and Australia. A successful strategy to contain COVID-19 involves controlling the free movement of EU citizens, as well as those of Switzerland, Norway and the UK. Therefore, restricting free movement will be required to control future disease epidemics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Umm Al Qura University for their support and encouragement.

Contributor Information

Waleed Al-Salem, Department of Public Health, Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Paula Moraga, Computer, Electrical and Mathematical Sciences and Engineering Division, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Thuwal, Saudi Arabia.

Hani Ghazi, School of Medicine, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia.

Syra Madad, Special Pathogens Program, NYC Health, New York, USA; Harvard Kennedy School, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, New York, USA.

Peter J Hotez, Texas Children's Hospital Center for Vaccine Development, Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, Texas, USA; Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA; Department of Molecular Virology and Microbiology, National School of Tropical Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA.

Author contributions

WS, PM and HG collected article data. WS, PM, SM and PH analyzed data. WS, PM, HG, SM and PH drafted the review.

Funding

None.

Competing interests

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Data availability

None.

References

- 1.Riou J, Althaus CL.. Pattern of early human-to-human transmission of Wuhan 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), December 2019 to January 2020. Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 2020;25(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O'Neill N, et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). International journal of surgery. 2020;76:71–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deslandes A, Berti V, Tandjaoui-Lambotte Y, et al.SARS-COV-2 was already spreading in France in late December 2019. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020:106006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Covid-19 confirmed cases in Finland and other countries. Helsenki Times, 2020. Available at https://www.helsinkitimes.fi/finland/finland-news/domestic/17271-first-case-of-wuhan-corona-virus-confirmed-in-finland.html [accessed July 2020].

- 5.Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, et al.Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):970–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spiteri G, Fielding J, Diercke M, et al.First cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the WHO European Region, 24 January to 21 February 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(9):2000178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horowita J.Italy locks down much of the country's north over the coronavirus. The New York Times, 2020. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/07/world/europe/coronavirus-italy.html [accessed July 2020].

- 8.Austria to close border to arrivals from Italy over coronavirus. Politico, 2020. Available at https://www.politico.eu/article/austria-to-close-border-to-arrivals-from-italy-over-coronavirus/ [accessed July 2020].

- 9.How an Austrian ski paradise became a COVID-19 hotspot. EURACTIV,, 2020. Available at https://www.euractiv.com/section/coronavirus/news/ischgl-oesterreichisches-skiparadies-als-corona-hotspot/ [accessed July 2020].

- 10.Hruby D.Coronavirus infected apres-ski in the Austrian Alps; criminal probe and litigation now follow. The Washington Post, 2020. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/austria-coronavirus-alps-ischgl-ski-resort-investigation-lawsuit/2020/05/17/d54fa5fa-93bf-11ea-87a3-22d324235636_story.html [accessed July 2020].

- 11.Ischgl was the secret virus hub in Europe. T-online Deutsch, 2020. Available at https://www.t-online.de/nachrichten/panorama/id_87525436/coronavirus-von-ischgl-verbreitete-sich-covid-19-in-ganz-europa.html [accessed July 2020].

- 12.Critchley M. A biological bomb’: The story of the Champions League game which sparked Italy's coronavirus crisis. The Independemt, 2020. Available at https://www.independent.co.uk/sport/football/european/coronavirus-news-latest-atalanta-valencia-champions-league-italy-crisis-bergamo-a9448541.html [accessed July 2020].

- 13.Verschueren G.Valencia announce 35% of players, staff tested have coronavirus. Bleacher Report, 2020. Available at https://bleacherreport.com/articles/2881322-valencia-announce-35-percent-of-players-staff-tested-have-coronavirus [accessed July 2020].

- 14.Taylor L.Genetic study of the coronavirus in Spain suggests the virus arrived Mid-February and the notion of a ‘Patient Zero’ is discarded. Euro Weekly, 2020. Available at https://www.euroweeklynews.com/2020/04/23/genetic-study-of-the-coronavirus-in-spain-suggests-the-virus-arrived-mid-february-and-the-notion-of-a-patient-zero-is-discarded/ [accessed July 2020].

- 15.Pybus O, Rambaut A, Plessis Ld, et al.Preliminary analysis of SARS-CoV-2 importation & establishment of UK transmission lineages. Oxford University, 2020. Available at https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/publications/preliminary-analysis-of-sars-cov-2-importation-establishment-of-uk-transmission-lineages/ [accessed July 2020].

- 16.Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer; 2016.

- 17.Covid-19, situation in Italy. Italian Ministry of Health, 2020. Available at http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=english&id=5367&area=nuovoCoronavirus&menu=vuoto [accessed July 2020].

- 18.Pisano G, Sadun R, Zanini M. Lessons from Italy's response to coronavirus. Harvard Business Review, 2020. Available at https://hbr.org/2020/03/lessons-from-italys-response-to-coronavirus [accessed July 2020].

- 19.Covid-19 Situation in France. French Ministry of Health, 2020. Available at https://www.gouvernement.fr/en/coronavirus-covid-19 [accessed July 2020].

- 20.Ames P. How Portugal became Europe's coronavirus exception. Politico, 2020. Available at https://www.politico.eu/article/how-portugal-became-europes-coronavirus-exception/ [accessed July2020].

- 21.Jones S.Swift action kept Portugal's coronavirus crisis in check, says minister. The Guardian, 2020. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/19/swift-action-kept-portugals-coronavirus-crisis-in-check-says-minister [accessed July 2020].

- 22.Official Covid-19 Cases in Spain Spanish Goverment. Ministry of Health, 2020. Available at https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov-China/situacionActual.htm [accessed July 2020].

- 23.Malta: Government announces new travel restrictions March 11. Garda World, 2020. Available at https://www.garda.com/crisis24/news-alerts/321756/malta-government-announces-new-travel-restrictions-march-11-update-2 [accessed July 2020].

- 24.Malta bans travel from four more european countries because of coronavirus. US News, 2020. Available at https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2020-03-11/malta-bans-travel-from-four-more-european-countries-because-of-coronavirus [accessed July 2020].

- 25.Malta Union of Teachers and government agree on school closure details. Malta Union of Teachers, 2020. Available at https://mut.org.mt/mut-and-government-agree-on-school-closure-details/ [accessed July 2020].

- 26.Gaffarena D.Malta: partial lockdown in malta to have effect from 28 March 2020. Mondaq, 2020. Available at https://www.mondaq.com/human-rights/912314/partial-lockdown-in-malta-to-have-effect-from-28-march-2020 [accessed July 2020].

- 27.The do's and don'ts of social distancing in Malta. UM Newspoint, 2020. Available at https://www.um.edu.mt/newspoint/news/2020/03/social-distancing-1 [accessed July 2020].

- 28.Malta Covid-19 official data. Maltese Government, 2020. Available at https://deputyprimeminister.gov.mt/en/health-promotion/covid-19/Pages/covid-19-infographics.aspx [accessed July 2020].

- 29.Italy locks down the country's north to fight coronavirus. The Wall Street Journal, 2020.

- 30.Mitze T, Kosfeld R, Rode J, Wälde K. Face Masks considerably reduce Covid-19 cases in Germany, 2020. Available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/italy-plans-large-scale-lockdown-in-countrys-north-to-fight-coronavirus-11583613874 [accessed July 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Nossiter A. For France, coronavirus tests a vaunted health care system. The New York Times, 2020. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/27/world/europe/coronavirus-france-health-care.html [accessed July 2020].

- 32.Coronavirus: ‘Closing French schools was right move, but parents are not ready’. The Local, 2020. Available at https://www.thelocal.fr/20200313/closing-french-schools-was-right-move-but-we-are-not-ready [accessed July2020].

- 33.French lockdown comes into force in bid to curtail spread of deadly virus. France 24, 2020. Available at https://www.france24.com/en/20200317-french-lockdown-comes-into-force-in-bid-to-curtail-spread-of-deadly-virus [accessed July 2020].

- 34.Rodriguez E.Thousands march in Spain on women's day despite coronavirus fears. Reuters, 2020. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-womens-day-spain/thousands-march-in-spain-on-womens-day-despite-coronavirus-fears-idUSKBN20V0ZJ [accessed July 2020].

- 35.Orea L, Álvarez IC.. How effective has the Spanish lockdown been to battle COVID-19? A spatial analysis of the coronavirus propagation across provinces. Documento de Trabajo, 2020:03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Minder R, Peltier E. Spain, on lockdown, weighs liberties against containing coronavirus. The New York Times, 2020. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/15/world/europe/spain-coronavirus.html [accessed July 2020].

- 37.Bachega H. Coronavirus: Inside story of Spain's care home tragedy. BBC, 2020. Available at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-52188820 [accessed July 2020].

- 38.COVID-19 Cases in Portugal . Portuguese Government, 2020. Available at https://covid19.min-saude.pt/ponto-de-situacao-atual-em-portugal/ [accessed July 2020].

- 39.Portugal orders schools, night clubs shut due to coronavirus . Reuters, 2020. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-portugal/portugal-orders-schools-night-clubs-shut-due-to-coronavirus-idUSKBN20Z3OP [accessed July 2020].

- 40.Demony C. Tourism between Spain, Portugal to be suspended due to coronavirus. Reuters, 2020. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-portugal-spain/update-1-tourism-between-spain-portugal-to-be-suspended-due-to-coronavirus-portuguese-govt-idUSL8N2B8194 [accessed July 2020].

- 41.Hartl T, Wälde K, Weber E. Measuring the impact of the German public shutdown on the spread of COVID-19. Voxeu CEPR, 2020. Available at https://voxeu.org/article/measuring-impact-german-public-shutdown-spread-covid-19 [accessed July 2020].

- 42.Current situation report of the RKI on COVID-19 . The Robert Koch Institute, 2020. Available at https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Situationsberichte/Gesamt.html [accessed July 2020].

- 43.Germany to shut most schools to slow coronavirus spread. Reuters, 2020. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-germany-schools-idUSKBN2100SA [accessed July 2020].

- 44.Bennhod K, Eddy M.. Germany bans groups of more than 2 to stop coronavirus as Merkel Self-Isolates. The New York Times, 2020. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/22/world/europe/germany-coronavirus-budget.html [accessed July 2020].

- 45.Nikel D.Denmark closes border to all international tourists for one month. Forbes, 2020. Available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidnikel/2020/03/13/denmark-closes-border-to-all-international-tourists-for-one-month/#4868974b726d [accessed July 2020].

- 46.Hjollund M.The government's main actions against coronavirus. Denmark Finans. 2020. Available at https://finans.dk/politik/ECE12003566/her-er-regeringens-vigtigste-tiltag-mod-coronavirus/?ctxref=ext [accessed July 2020].

- 47.Ging JP. Coronavirus: Denmark and Norway further relax COVID-19 restrictions. Euronews. 2020. Available at https://www.euronews.com/2020/05/08/coronavirus-denmark-and-norway-further-relax-covid-19-restrictions [accessed July 2020].

- 48.Nikel D.Norway closes all airports to foreigners as coronavirus cases mount. Forbes. 2020. Available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidnikel/2020/03/14/norway-closes-all-airports-to-foreigners-as-coronavirus-cases-mount/#1c95521a1913 [accessed July 2020].

- 49.Fouche G, Klesty V.. Norway to ease curbs ‘little by little’ after coronavirus lockdown: PM. Reuters, 2020. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-norway/norway-to-ease-curbs-little-by-little-after-coronavirus-lockdown-pm-idUSKBN21P2G4 [accessed July 2020].

- 50.Fouche G, Klesty V. Norway to reopen high schools, bars and most of society by mid-June. Reuters, 2020. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-norway/norway-to-reopen-high-schools-bars-and-most-of-society-by-mid-june-idUSKBN22J2O4 [accessed July 2020].

- 51.Finland to lift lockdown in region around Helsinki. Reuters, 2020. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-finland/update-1-finland-to-lift-lockdown-in-region-around-helsinki-idUSL5N2C31X8 [accessed July 2020].

- 52.Confirmed coronavirus cases (COVID-19) in Finland . Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, 2020. Available at https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/92e9bb33fac744c9a084381fc35aa3c7 [accessed July 2020].

- 53.Covid-19 official data in Iceland. Directorate of Health, 2020. Available at https://www.covid.is/data [accessed July 2020].

- 54.SST D. Official Danish Covid-19. Cases Report. Sundhedsstyrelsen, 2020. Available at https://www.sst.dk/da/corona/tal-og-overvaagning#2 [accessed July 2020].

- 55.NIPH . Daily report and statistics about coronavirus and COVID-19. Norwegian Institute of Public Health, 2020. Available at https://www.fhi.no/en/id/infectious-diseases/coronavirus/daily-reports/daily-reports-COVID19/ [accessed July 2020].

- 56.Muhonen T, Nalbantoglu M.. The Finnish government's exceptional efforts to contain the coronavirus. Helsingin Sanomat, 2020. Available at https://www.hs.fi/politiikka/art-2000006441020.html [accessed July 2020].

- 57.Finnish Government . Government extends measures related to emergency conditions until 13, May. 2020. Available at https://valtioneuvosto.fi/artikkeli/-/asset_publisher/10616/hallitus-jatkaa-poikkeusoloihin-liittyvia-toimia-13-toukokuuta-saakka?_101_INSTANCE_LZ3RQQ4vvWXR_languageId=en_US [accessed July 2020].

- 58.Swedish PMlofven says high schools, universities should switch to distance learning. Reuters, 2020. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-sweden/swedish-pm-lofven-says-high-schools-universities-should-switch-to-distance-learning-idUSKBN2141D3 [accessed July 2020].

- 59.Iceland DoIi. Travel restrictions and 14-day quarantine upon entry to Iceland. 2020. Available at https://utl.is/index.php/en/about-directorate-of-immigration/news/1085-travel-restrictions-to-iceland-and-14-day-quarantine-for-all-residents [accessed July 2020].

- 60.Bjornsson IB.There will be a ban on assembly and schooling limited (Icelandic). RUV, 2020. Available at https://www.ruv.is/frett/samkomubanni-verdur-komid-a-og-skolastarf-takmarkad [accessed July 2020].

- 61.Response to COVID-19 in Iceland. Iceland Government, 2020. Available at https://www.government.is/diplomatic-missions/embassy-article/2020/03/09/response-to-COVID-19-in-Iceland/ [accessed July 2020].

- 62.Hafstað V. COVID-19 Update in Iceland. Iceland Monitor, 2020. Available at https://icelandmonitor.mbl.is/news/news/2020/04/21/covid_19_update/ [accessed July 2020].

- 63.McGwin K.Iceland readies for a gradual end to coronavirus measures. Arctic Today, 2020. Available at https://www.arctictoday.com/iceland-readies-for-a-gradual-end-to-coronavirus-measures/ [accessed July 2020].

- 64.Omarsdottir A. Tight ban: No more than 20 may meet. RUV, 2020. Available at https://www.ruv.is/frett/hert-samkomubann-ekki-fleiri-en-20-mega-koma-saman [accessed July 2020].

- 65.Hafstað V.Two people die of Covid-19 in Iceland. Iceland Monitor, 2020. Available at https://icelandmonitor.mbl.is/news/news/2020/04/03/two_people_die_of_covid_19_in_iceland/ [accessed July 2020].

- 66.Kim TH.Why Sweden is unlikely to make a U-turn on its controversial Covid-19 strategy. The Guardian, 2020. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/may/22/sweden-u-turn-controversial-covid-19-strategy [accessed July 2020].

- 67.Randolph HE, Barreiro LB. Herd immunity: understanding COVID-19. Immunity. 2020;52(5):737–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.The Police: Limited possibilities for public gatherings and events. Krisinformation, 2020. Available at https://www.krisinformation.se/en/news/2020/march/the-government-has-decided-to-limit-public-gatherings-and-events-in-sweden [accessed July 2020].

- 69.Confirmed cases in Sweden - daily update. The Swedish Public Health Agency, 2020. Available at https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/smittskydd-beredskap/utbrott/aktuella-utbrott/covid-19/bekraftade-fall-i-sverige/ [accessed July 2020].

- 70.Statement from the National Public Health Emergency Team - Tuesday 26 May. Irish Governemtn. Available at https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/78916-statement-from-the-national-public-health-emergency-team-tuesday-26-may/ [accessed July 2020].

- 71.Secon H. England's coronavirus death rate is nearly 3 times higher than Ireland's. Proactive social-distancing measures made the difference. Business Insider, 2020. Available at https://www.businessinsider.com/england-ireland-coronavirus-response-compared-2020-4 [accessed July 2020].

- 72.Coronavirus: Republic of Ireland to close schools and colleges. BBC, 2020. Available at https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-51850811 [accessed July 2020].

- 73.Irish Government warns against all non-essential travel including to UK. ITV, 2020. Available at https://www.itv.com/news/utv/2020-03-16/irish-government-warns-against-all-non-essential-travel-including-to-uk/ [accessed July 2020].

- 74.Covid-19 cases in Ireland. Irish Governemtn, 2020. Available at https://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/respiratory/coronavirus/novelcoronavirus/casesinireland/ [accessed July 2020].

- 75.COVID-19: guidance for households with possible coronavirus infection. British Government, 2020. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-stay-at-home-guidance [accessed July 2020].

- 76.COVID-19 Timeline in United Kingdom. British Foreign Policy Group, 2020. Available at https://bfpg.co.uk/2020/04/covid-19-timeline/ [accessed July 2020].

- 77.Government announces further measures on social distancing British Government, 2020. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-announces-bfurther-measures-on-social-distancing[accessed July 2020].

- 78.Stewart H, Mason R, Dodd V. Boris Johnson orders UK lockdown to be enforced by police. The Guardian, 2020. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/23/boris-johnson-orders-uk-lockdown-to-be-enforced-by-police [accessed July 2020].

- 79.Covid-19 situation in United Kingdom. Public Health England. Available at https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/ [accessed July 2020].

- 80.Official COVID-19 cases in Austria. Austrian Government, 2020. Available at https://info.gesundheitsministerium.at/ [accessed July 2020].

- 81.Coronavirus: The situation in Switzerland. Swiss Information, 2020. Available at https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/covid-19_coronavirus–the-situation-in-switzerland/45592192 [accessed July 2020].

- 82.Liechtenstein - Covid 19 current situation. Liechtenstein Government, 2020. Available at https://www.sciencedz.net/covid19/index.php?country=Liechtenstein [accessed July 2020].

- 83.Taken in Liechtenstein in Response to the Coronavirus Pandemic. Liechtenstein Government, 2020. Available at http://www.liechtensteinusa.org/article/measures-taken-in-liechtenstein-in-response-to-the-coronavirus-pandemic [accessed July 2020].

- 84.Liechtenstein governmental measures. Furstentum Liechtenstein, 2020. Available at https://www.regierung.li/media/attachments/120-corona-massnahmen-verschaerft-0316.pdf?t=637203447788083667 [accessed July 2020].

- 85.Official Covid-19 Austrian information. Austrian Government, 2020. Available at https://www.sozialministerium.at/Informationen-zum-Coronavirus/Neuartiges-Coronavirus-(2019-nCov).html [accessed July 2020].

- 86.Austria will reopen schools with split classes next month. Reuters, 2020. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-austria-education/austria-will-reopen-schools-with-split-classes-next-month-idUSKCN2261LS [accessed July 2020].

- 87.One day after the country went on lockdown, a makeshift emergency hospital was completed in Vienna to treat incoming coronavirus patients. Business Insider, 2020. Available at https://www.businessinsider.com/how-austria-reacted-quickly-and-firmly-to-tackle-coronavirus-crisis-2020-4#one-day-after-the-country-went-on-lockdown-a-makeshift-emergency-hospital-was-completed-in-vienne-to-treat-incoming-coronavirus-patients-7 [accessed July 2020].

- 88.Roache M. Austria requires masks to be worn amid plans to Ease coronavirus lockdown. The Time, 2020. Available at https://time.com/5816129/austria-rollback-lockdown/ [accessed July 2020].

- 89.Revill J.Switzerland to start easing Covid-19 restrictions from April 27. Reuters, 2020. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-swiss/switzerland-to-start-easing-covid-19-restrictions-from-april-27-idUSZ8N2AZ02O [accessed July 2020].

- 90.Federal Council declares state of emergency, shuts down the country and mobilizes the army Tagesanzeiger, 2020. Available at https://www.tagesanzeiger.ch/schweiz/standard/bundesrat-erklaert-notstand-riegelt-das-land-ab-und-mobilisiert-die-armee/story/17921807?utm_source=twitter&utm_campaign=Ed_Social_Post&utm_medium=Ed_Post_TA [accessed July 2020].

- 91.Coronavirus: Federal Council bans large-scale events. The Federal Swiss Council, 2020. Available at https://www.admin.ch/gov/en/start/documentation/media-releases.msg-id-78289.html [accessed July 2020].

- 92.Fleming S.Dinner with friends: How Switzerland is relaxing its coronavirus lockdown. World Economic Forum, 2020. Available at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/switzerland-relaxing-its-coronavirus-lockdown-measures/ [accessed July 2020].

- 93.Coronavirus: the latest numbers in Switzerland. Swiss Information, 2020. Available at https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/swiss-stats_coronavirus–the-latest-numbers-/45674308 [accessed July 2020].

- 94.RIVM . Official Covid-19 cases in Netherlands, RIVM., 2020. Available at https://www.rivm.nl/coronavirus-covid-19/grafieken [accessed July 2020].

- 95.Official Belgian Covid-19 cases. L'institut belge de santé Sciensano. Available at https://covid-19.sciensano.be/sites/default/files/Covid19/Derni%C3%A8re%20mise%20%C3%A0%20jour%20de%20la%20situation%20%C3%A9pid%C3%A9miologique.pdf [accessed July 2020].

- 96.New measures to stop spread of coronavirus in the Netherlands. Government of Netherlands, 2020. Available at https://www.government.nl/latest/news/2020/03/12/new-measures-to-stop-spread-of-coronavirus-in-the-netherlands [accessed July 2020].

- 97.Newmark Z. Dutch to start fining groups defying pandemic rules. Netherlands Time, 2020. Available at https://nltimes.nl/2020/03/23/dutch-start-fining-groups-defying-pandemic-rules-stop-said-rutte [accessed July 2020].

- 98.Tullis P.Dutch cooperation made an ‘Intelligent Lockdown’ a success. Bloomberg, 2020. Available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2020-06-05/netherlands-coronavirus-lockdown-dutch-followed-the-rules [accessed July 2020].

- 99.Wouw Pvd . Plastic shields in place, Dutch schools to reopen amid coronavirus. Reuters, 2020. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-netherlands-school/plastic-shields-in-place-dutch-schools-to-reopen-amid-coronavirus-idUSKBN22K242 [accessed July 2020].

- 100.Barbiroglio E. COVID-19 emergency measures in Belgium to avoid Italian-Style lockdown. Forbes, 2020. Available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/emanuelabarbiroglio/2020/03/13/covid-19-emergency-measures-in-belgium-to-avoid-italian-style-lockdown/#d820b7f39fda [accessed July 2020].

- 101.Covid-19 official Belgian cases. Belgian Government Covid-19, 2020. Available at https://covid-19.sciensano.be/sites/default/files/Covid19/Derni%C3%A8re%20mise%20%C3%A0%20jour%20de%20la%20situation%20%C3%A9pid%C3%A9miologique.pdf [accessed July 2020].

- 102.Luxembourg R.University of Luxembourg and European Schools of Kirchberg and Mamer suspend classes. RTL Luxembourg, 2020. Available at https://today.rtl.lu/news/luxembourg/a/1482214.html [accessed July 2020].

- 103.Council LG.Government Council - New measures taken in response to the Coronavirus, 2020. Available at https://gouvernement.lu/en/actualites/toutes_actualites/communiques/2020/03-mars/15-nouvelles-mesures-coronavirus.html [accessed July 2020].

- 104.Council LG.Measures taken by the Government Council on 12 March 2020 in response to the Coronavirus, 2020. Available at https://gouvernement.lu/en/actualites/toutes_actualites/communiques/2020/03-mars/12-cdg-extraordinaire-coronavirus.html [accessed July 2020].

- 105.Gradual easing of lockdown in Luxembourg VDL, 2020. Available at https://www.vdl.lu/en/news/gradual-easing-lockdown [accessed July 2020].

- 106.Covid-19 official Latvian data. Latvian Government, 2020. Available at https://infogram.com/covid-19-izplatiba-latvija-1hzj4ozwvnzo2pw [accessed July 2020].

- 107.Lithuania Covid-19 situation report. Lithuanian Government, 2020. Lithuania Covid-19 situation report Accessed on July 2020].

- 108.Covid-19 official Estonian data. Estonian Government, 2020. Available at https://koroonakaart.ee/en [accessed July 2020].

- 109.Covid-19 official Latvian website. Latvian Government, 2020. Available at https://covid19.gov.lv/ [accessed July 2020].

- 110.Lithuania and Latvia close schools, ban large public gatherings over coronavirus. Reuters, 2020. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-lithuania/lithuania-and-latvia-close-schools-ban-large-public-gatherings-over-coronavirus-idUSKBN20Z25W [accessed July 2020].

- 111.Panorāma R. Latvian infectious diseases specialists: returning travelers must self-isolate for 14 days. LSM Latvia, 2020. Available at https://eng.lsm.lv/article/society/health/latvian-infectologist-returning-travelers-must-self-isolate-for-14-days.a351880/ [accessed July 2020].

- 112.Health alert: latvia implements further restrictions to promote social distancing. United States Embassy Riga, 2020. Available at https://lv.usembassy.gov/health-alertlatvia-implements-further-restrictions-to-promote-social-distancing/ [accessed July 2020].

- 113.Sander G.Facing pandemic latvia follows the lead of its experts. Foreign Policy, 2020. Available at https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/13/coronavirus-pandemic-latvia-follows-lead-medical-experts-science/ [accessed July 2020].

- 114.Lithuania Covid-19 updated report. Lithuanian Government, 2020. Available at https://koronastop.lrv.lt/en/ [accessed July 2020].

- 115.Confirmed Lithuanian cases over time in World Health Organization. World Health Organization, 2020. Available at https://covid19.who.int/region/euro/country/lt [accessed July 2020].

- 116.Important information regarding the COVID-19 Lithuanian restrictions. Vilnius Government,, 2020. Available at https://www.govilnius.lt/media-news/important-information-regarding-the-coronavirus [accessed July 2020].

- 117.Important information regarding the Coronavirus (COVID-19). MOFA Lithuania, 2020. Available at https://urm.lt/default/en/important-covid19 [accessed July 2020].

- 118.Quarantine announced throughout the territory of the Republic of Lithuania Lithuanian Government, 2020. Available at https://lrv.lt/en/news/quarantine-announced-throughout-the-territory-of-the-republic-of-lithuania-attached-resolution-3 [accessed July 2020].

- 119.Jačauskas I. Lithuanian government extends quarantine, makes facemasks mandatory. LRT, 2020. Available at https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1161456/lithuanian-government-extends-quarantine-makes-facemasks-mandatory [accessed July 2020].

- 120.Sytas A. Coronavirus: Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia create ‘travel bubble’ to ease restrictions. World Economic Forum, 2020. Available at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/baltic-states-to-create-travel-bubble-as-pandemic-curbs-eased/ [accessed July 2020].

- 121.March: Coronavirus in Estonia. Estonian World, 2020. Available at https://estonianworld.com/life/march-blog-coronavirus-in-estonia/ [accessed July 2020].

- 122.All Estonian schools to close on Monday, additional border controls introduced. ERR, 2020. Available at https://news.err.ee/1063221/all-schools-to-close-on-monday-additional-border-controls-introduced [accessed July 2020].

- 123.April: Coronavirus in Estonia. Estonian World, 2020. Available at https://estonianworld.com/knowledge/april-blog-coronavirus-in-estonia/ [accessed July 2020].

- 124.Polish Goverment . Coronavirus in Poland: information and recommendations. Polish Goverment, 2020. Available at https://www.gov.pl/web/coronavirus [accessed August 2020].

- 125.POlish Government . Restriction of activity in the field of spa treatment. Polish Goverment, 2020. Available at https://www.gov.pl/web/zdrowie/ograniczenie-dzialalnosci-w-zakresie-lecznictwa-uzdrowiskowego [accessed August 2020].

- 126.Coronavirus in Poland: Continuation of restrictions, mandatory masks. Wrocławia Poland, 2020. Available at https://www.wroclaw.pl/en/coronavirus-in-poland-continuation-of-restrictions-mandatory-masks [accessed August 2020].

- 127.McLaughlin D.Poland to ease virus lockdown ahead of contentious election. Irish Times, 2020.

- 128.Poland announces stage 3 of lifting lockdown measures. EURACTIV, 2020. Available at https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/europe/poland-to-ease-virus-lockdown-ahead-of-contentious-election-1.4241127 [accessed August 2020].

- 129.State of emergency in Czech Republic. Resolution: The government of the Czech Republic of 15 March 2020 no. on the adoption of a crisis measure. The Government of the Czech Republic, 2020. Available at https://www.mvcr.cz/mvcren/article/state-of-emergency.aspx [accessed August 2020].

- 130.COVID-19: Overview of the current situation in the Czech Republic. Czech Republic Government, 2020. Available at https://onemocneni-aktualne.mzcr.cz/covid-19 [accessed August 2020].

- 131.Henley J. UK said to be studying Czech exit plan where shops now reopening. The Guardian, 2020. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/27/czech-republic-shops-reopen-as-part-of-gradual-coronavirus-lockdown-exit [accessed August 2020].

- 132.Tait R, Walker S.. How far? How soon? Czechs grapple with how to ease Covid-19 lockdown. The Guardian, 2020. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/19/czechs-grapple-with-how-to-ease-covid-19-lockdown [accessed August 2020].

- 133.COVID-19: Epidemiological information in Czech Republic Czech Republic Government, 2020. Available at https://www.uzis.cz/index.php?pg=covid-19 [accessed August 2020].

- 134.A state of emergency and a state of emergency were ordered for the entire territory of the country (Hungary). HVG Hungary, 2020. Available at https://hvg.hu/itthon/20200311_Koronavirus_kihirdette_a_veszelyhelyzet_a_kormany [accessed August 2020].