Abstract

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has exposed long-standing fragmentation in health systems strengthening efforts for health security and universal health coverage while these objectives are largely interdependent and complementary. In this prevailing background, we reviewed countries’ COVID-19 Preparedness and Response Plans (CPRPs) to assess the extent of integration of non-COVID-19 essential health service continuity considerations alongside emergency response activities. We searched for COVID-19 planning documents from governments and ministries of health, World Health Organization (WHO) country offices and United Nations (UN) country teams. We developed document review protocols using global guidance from the WHO and UN and the health systems resilience literature. After screening, we analysed 154 CPRPs from 106 countries. The majority of plans had a high degree of alignment with pillars of emergency response such as surveillance (99%), laboratory systems (96%) and COVID-19-specific case management (97%). Less than half considered maintaining essential health services (47%); 41% designated a mechanism for health system–wide participation in emergency planning; 34% considered subnational service delivery; 95% contained infection prevention and control (IPC) activities and 29% considered quality of care; and 24% were budgeted for and 7% contained monitoring and evaluation of essential health services. To improve, ongoing and future emergency planning should proactively include proportionate activities, resources and monitoring for essential health services to reduce excess mortality and morbidity. Specifically, this entails strengthening subnational health services with local stakeholder engagement in planning; ensuring a dedicated focus in emergency operations structures to maintain health systems resilience for non-emergency health services; considering all domains of quality in health services along with IPC; and building resilient monitoring capacity for timely and reliable tracking of health systems functionality including service utilization and health outcomes. An integrated approach to planning should be pursued as health systems recover from COVID-19 disruptions and take actions to build back better.

Keywords: Public health, health systems, health systems strengthening, health systems resilience, health policy

Key messages.

Current emergency response planning does not have adequate coverage to maintain health systems functionality for essential health service delivery alongside emergency-specific interventions and healthcare.

There is a need for greater participation of stakeholders responsible for non-emergency health service delivery, and disease-specific and life-course-specific programmes, in emergency preparedness and response planning and associated coordination structures.

There are country examples with good planning practices for budgeting and monitoring and evaluation as well as explicit consideration for maintaining essential health services. However, a large proportion of countries do not apply a systematic and integrated approach to planning, and there are gaps in strengthening capacities for subnational service delivery.

The findings from this study can enable national authorities and partners including academia, international organizations and donors to better align health emergency planning with broader population health needs and consider strengthening health systems components for delivery of both emergency and non-emergency health services in tandem.

Introduction

The health and socioeconomic effects of the pandemic of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) are being felt globally and demonstrate that, while some countries are facing more devastating effects than others, no single health system was fully prepared to meet this challenge. Essential health services such as those for communicable and noncommunicable disease, mental health, sexual and reproductive health, maternal and child health, nutrition and immunization have been disrupted in countries of all income levels and across all geographic regions (World Health Organization, 2020a; Woolf et al., 2020).

A resilient health system is one that can prepare for, respond and adapt to disruptive public health events while ensuring the continuity of quality, essential health services at all levels of the health system (World Health Organization, 2020b; Kruk et al., 2015). This requires aligning health emergency planning with broader health sector strategy and vice versa, including appropriate budgets and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) frameworks for planned as well as unexpected interventions. Although there has been significant discourse on the need for health systems resilience (Haldane et al., 2021), fragmentations between health system strengthening, emergency preparedness and response, and disease-specific efforts continue to hinder progress towards the major global health objectives of health security and universal health coverage (Kluge et al., 2018; Spicer et al., 2020). Evidence on the extent of integration and a resilience perspective within planning has thus far been limited in the COVID-19 and broader health systems discourse (Lal et al., 2021; Tumusiime et al., 2020).

In response to the pandemic, countries developed COVID-19 Preparedness and Response Plans (CPRPs) to support national action and resource mobilization. The WHO Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan (SPRP) (World Health Organization, 2020c,d,e,f) and operational guidance for maintaining essential health services (World Health Organization, 2020g,i) and their respective updates outline measures to plan and address the COVID-19 situation in countries and its associated disruptions. The SPRP contains thematic pillars (Box 1) for emergency preparedness and response and includes maintenance of non-COVID-19 health services. The COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan (GHRP) (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2020a,b,c) and the UN framework for the immediate socioeconomic response to COVID-19 (United Nations, 2020) also serve to inform national COVID-19 planning. These documents set distinct yet complementary objectives and cover populations’ health needs (including maintaining non-COVID-19 essential health services) under pandemic, humanitarian and development contexts and highlight the need for integrated planning. Analysing CPRPs offers useful insights to understand the extent of integration of health systems resilience considerations into emergency management planning in the current COVID-19 crisis.

Box 1.

Major pillars outlined in WHO COVID-19 SPRP dated 22 May 2020

Pillar 1: Country-level coordination, planning and monitoring.

Pillar 2: Risk communication and community engagement.

Pillar 3: Surveillance, rapid response teams and case investigation.

Pillar 4: Points of entry.

Pillar 5: National laboratories.

Pillar 6: Infection prevention and control.

Pillar 7: Case management.

Pillar 8: Operational support and logistics.

Pillar 9: Maintaining essential health services during an outbreak.

UN GHRP Strategic Priorities (SPs)

SP 1: Contain the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic and decrease morbidity and mortality.

SP 2: Decrease the deterioration of human assets and rights, social cohesion and livelihoods.

SP 3: Protect, assist and advocate for refugees, internally displaced persons, migrants and host communities particularly vulnerable to the pandemic.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the content of CPRPs in the context of global planning guidance and assess the extent of integration of non-COVID-19 essential health service continuity considerations within the plans alongside emergency response activities. The specific objectives were as follows:

To assess the alignment of CPRPs with the WHO SPRP thematic pillars and UN GHRP strategic priorities (for countries identified in the GHRP).

-

To evaluate considerations for health service continuity in the context of COVID-19 preparedness and response. Specific areas assessed under this objective were as follows:

Inclusion of SPRP Pillar 9 maintaining essential health services in the CPRPs and triangulation of findings with data from the WHO’s Pulse Survey on Continuity of Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 pandemic

Presence of a dedicated structure or mechanism for integrating health systems-wide participation and maintaining essential health services activities in CPRPs;

Considerations for the impact of COVID-19 on health service disruption at subnational levels and

Presence of quality of care considerations for essential health services alongside infection prevention and control (IPC).

To ascertain whether the CPRPs included general costing and M&E of identified activities and whether there was a dedicated budget line and M&E component within the plans for maintaining essential health services.

Materials and methods

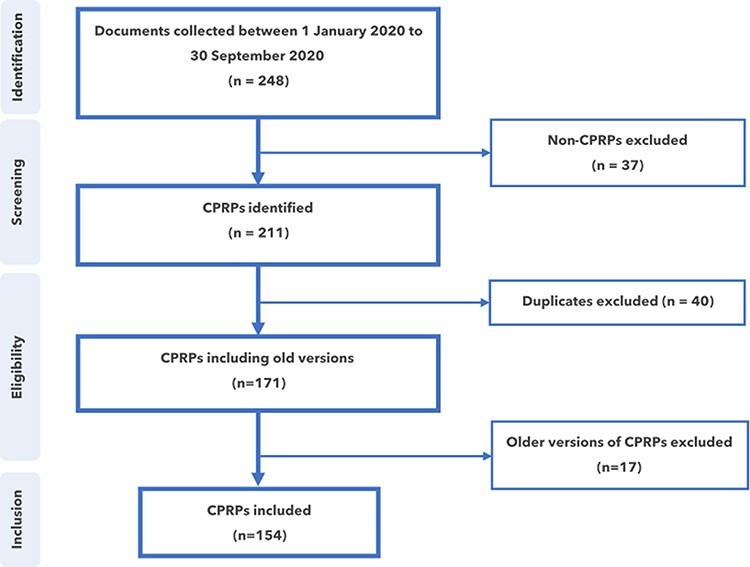

We searched for COVID-19 planning documents from national governments and ministries of health, WHO country offices and UN country teams between 1 January 2020 and 30 September 2020. A total of 248 COVID-19 planning documents from 125 countries were collected and screened following defined criteria (Box 2) to include only CPRPs for analysis.

Box 2.

CPRP criteria

A document was considered as a CPRP if:

It explicitly listed a set of activities to prepare for and respond to COVID-19;

The activities had a focus on public health interventions;

It was developed at the national level or state level and

It was prepared by national governments, WHO country offices and/or UN country teams.

After initial screening, 211 documents were identified as CPRPs. CPRPs with the same content but reproduced in different languages were counted as one CPRP. Different versions of CPRPs by the same ownership authority were counted as one CPRP. The most up-to-date version available was included in the analysis, and older versions were reviewed to understand changes over time. After eligibility screening, 154 CPRPs from 106 countries were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). There were countries that had more than one plan from different authorities (e.g. the government or ministry of health, WHO country office or UN country team) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

The process of screening CPRPs

Table 1.

Number of countries, territories and areas included in this study by World Bank income group classifications (World Bank, 2020) and CPRPs identified by ownership authority

| CPRPs by ownership authority for the 106 countries | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World Bank income group (gross national income per capita) |

Total number of countries, territories and areas classified by World Bank | Total number of countries, territories and areas included in this study | Government or ministry of health (as % of total CPRPs included in this study) |

UN country team (as % of total CPRPs included in this study) |

WHO country office (as % of total CPRPs included in this study) |

Number of CPRPs (as % of total CPRPs included in this study) |

| LIC (US$1035 or less) | 29 | 29 | 29 | 7 | 10 | 46 (30%) |

| LMIC (US$1036–$4045) | 50 | 37 | 33 | 11 | 13 | 57 (37%) |

| UMIC (US$4046–$12 535) | 56 | 32 | 18 | 11 | 11 | 40 (26%) |

| HIC (US$12 536 or more) | 83 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 11 (7%) |

| Total | 218 | 106 | 86 (56%) | 31 (20%) | 37 (24%) | 154 (100%) |

First-tier review

The 154 CPRPs were analysed using a protocol (Annex 1) based on the review objectives. This observed alignment of CPRPs with the WHO SPRP pillars (including maintaining essential health services) and GHRP strategic priorities (if CPRPs belonged to priority countries listed in the GHRP). The protocol further assessed the plans’ coverage of or considerations for

A dedicated mechanism for maintaining essential health services in the national coordination structure for COVID-19;

Quality of essential health services (alongside IPC considerations);

Essential health service delivery at the subnational level including primary health care and

A dedicated budget and defined M&E for activities for maintaining essential health services.

Second-tier review and triangulation of findings

A further detailed review using a second protocol (Annex 2) was conducted on plans that had considerations for maintaining essential health services. This was based on the 14 key functions of maintenance of essential health services (Box 3) as outlined in the WHO operational guidance (World Health Organization, 2020f). In addition, a crosswalk of countries with plans published by national authorities that considered maintaining essential health services was conducted to compare with data from the WHO Pulse Survey on Continuity of Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 pandemic (World Health Organization, 2020a). In the survey, informants from ministries of health or WHO country offices responded to key performance indicator 9.3, ‘Has your country identified a core set of essential health services to be maintained during the COVID-19 pandemic?’.

Box 3.

The 14 key functions of maintenance of essential health services

Context considerations

Adjust governance and coordination mechanisms to support timely action;

Prioritize essential health services and adapt to changing contexts and needs;

Optimize service delivery setting and platforms;

Establish safe and effective patient flow at all levels;

Rapidly optimize health workforce capacity;

Maintain the availability of essential medications, equipment and supplies;

Fund public health and remove financial barriers to access;

Strengthen communication strategies to support the appropriate use of essential services;

Strengthen the monitoring of essential health services;

Use digital platforms to support essential health service delivery;

Life-course stages considerations (maternal and new-born health; child and adolescent health; older people; sexual and reproductive services);

Nutrition, noncommunicable diseases and mental health considerations and

Communicable diseases considerations (human immunodeficiency virus, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections; tuberculosis; immunization; neglected tropical diseases; malaria).

Global synthesis with income group analysis

The analysis of the plans was conducted using a phased approach in consultation with WHO regional offices and respective country offices starting with the African Region and then Eastern Mediterranean Region, South East Asian Region, European Region, Western Pacific Region and Region of the Americas. Following this, the findings were synthesized globally and analysed by country income group.

Results

Overview

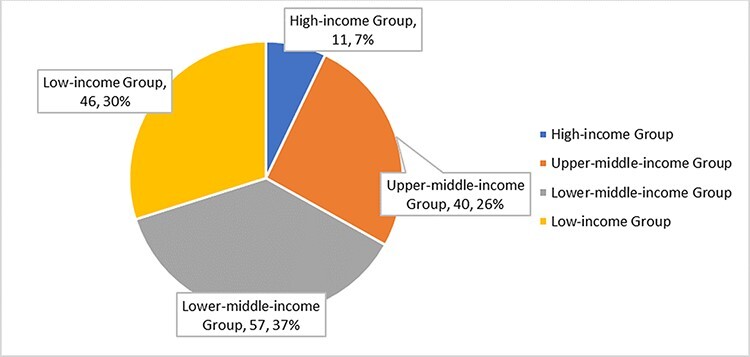

Of the 154 CPRPs reviewed in this study, 7% were from high-income countries (HICs), 26% from upper-middle-income countries (UMICs), 37% from lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) and 30% from low-income countries (LICs) (Figure 2 and Table 1). A breakdown of the countries, territories and areas for which CPRPs were reviewed by the World Bank income group classification is provided in Table 1 (World Bank, 2020).

Figure 2.

CPRPs included in this review, by World Bank income group (n = 154)

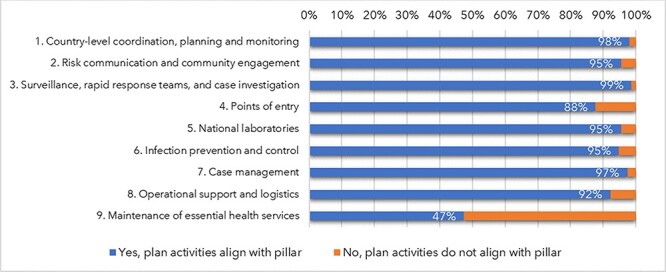

Alignment of plans with global guidance

The proportion of CPRPs that aligned with the first eight SPRP pillars (Box 1) ranged between 88% and 99%. Just under half (47%) of CPRPs were in alignment with Pillar 9 maintaining essential health services (Figure 3). This constituted 73 CPRPs. Of these, 14% (22) had consideration for maintenance of essential health services prior to WHO releasing its first operational guidance dated 25 March 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020g). Between 25 March 2020 and 22 May 2020, when the maintenance of essential health services was incorporated as a dedicated pillar (Pillar 9) in the updated version of WHO’s SPRP (World Health Organization, 2020e), another 20% of CPRPs (31) were found to have considered the maintenance of essential health services.

Figure 3.

Proportion of CPRPs in alignment with each pillar outlined in the WHO SPRP, May 2020 (n = 154)

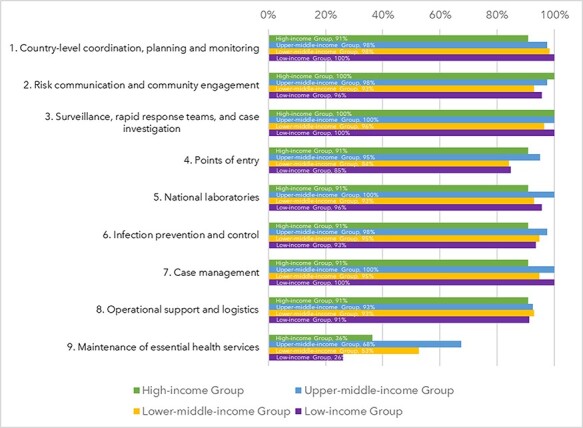

While there were no notable differences in alignment with the initial eight SPRP pillars across income groups (Figure 4), differences were observed in the proportion of plans covering maintaining essential health services (Pillar 9), with higher proportions observed in both UMICs (68%) and LMICs (53%) when compared to HICs (36%) and LICs (26%).

Figure 4.

Proportion of CPRPs in each income group that are in alignment with each pillar of COVID-19 emergency preparedness and response outlined in the WHO SPRP, May 2020 (n = 154)

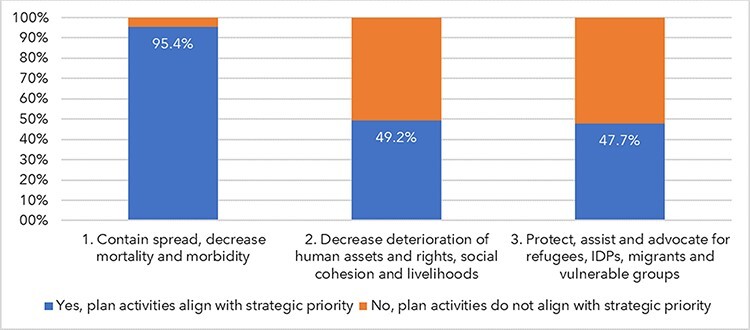

Among priority countries identified in the July 2020 GHRP, 95% of their plans covered SP 1, 49% incorporated SP 2 and 48% incorporated SP 3 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Alignment of humanitarian context countries’ CPRPs with UN GHRP strategic priorities (n = 65) (IDP: internally displaced persons)

Essential health service considerations in plans

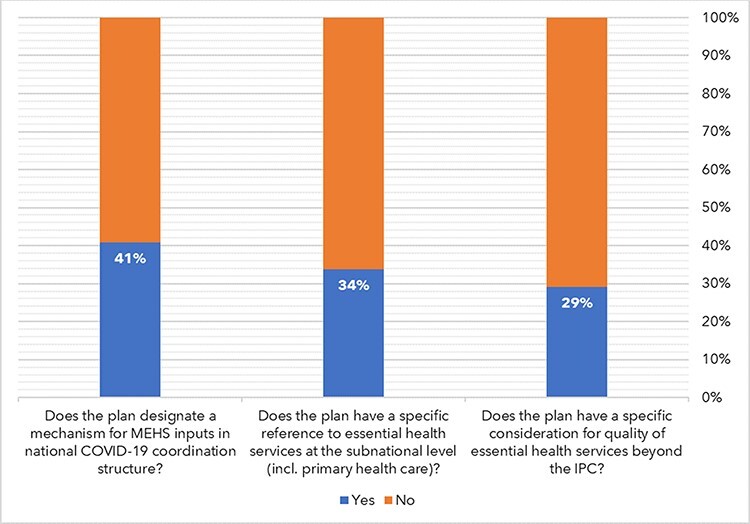

The majority of the plans (98%) included ‘country-level coordination, planning and monitoring’ (Pillar 1) for COVID-19-specific activities (Figure 3), but less than half (41%) mentioned dedicated structures or mechanisms for maintaining non-COVID-19 essential health services within coordination structures such as a focal person or entity (Figure 6). No significant difference across income groups was observed.

Figure 6.

CPRP considerations for maintenance of essential health services: in national coordination structures, at the subnational level and quality (n = 154) (MEHS: maintenance of essential health services; IPC: infection prevention and control)

Overall, 34% of the plans considered the impact of COVID-19 on essential health services or contained mitigation measures at subnational levels including in primary health care (Figure 6). This varied widely by income group from 9% of HICs to 44% of LICs.

While the majority of the plans (95%) considered IPC (Figure 3), less than one-third (29%) had explicit consideration for quality of service delivery (e.g. patient safety or effectiveness) beyond IPC (Figure 6). This ranged between 18% in HICs and 37% in LMICs.

Although most of the plans (88%) had a budget component, only 24% identified clear budget lines for maintaining essential health services activities (Figure 6). UMICs and LMICs were more likely (45% and 23%, respectively) than LICs and HICs to do so (11% and 9%, respectively).

Overall, 53% included an M&E framework or had considered M&E for activities in the plan (e.g. listing indicators for activities or outlining an approach to M&E). Overall, 7% of the plans specified M&E for essential health service activities (Figure 5). Of note, none of the plans from HICs and LICs specified M&E for maintaining essential health services, while 17% of the plans from UMICs and 7% from LMICs did.

Of the 47% of plans that considered maintaining non-COVID-19 essential health services, 6% considered funding public health and removing financial barriers to access, 21% considered using digital platforms to support service delivery, 28% considered strengthening communication strategies to support the appropriate use of essential services, 31% considered strengthening the monitoring of essential health services, 37% considered maintaining services related to communicable diseases (human immunodeficiency virus, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections; tuberculosis; immunization; neglected tropical diseases; malaria) and 44% considered adjusting governance and coordination mechanisms to support timely action.

Discussion

The findings in this paper indicate that globally CPRPs were broadly aligned with global guidance and the associated thematic pillars for preparedness and response but with limited inclusion of explicit activities for maintaining essential non-COVID-19 health services (examples of good planning practices observed are provided in Box 4). A number of factors may have contributed to this including the unprecedented and rapid increase in cases and deaths from COVID-19 that led planners to focus on acute response and COVID-19-specific healthcare. Policymakers and health leaders, at the initial stage of the pandemic, failed to anticipate the extent or duration of health service disruptions and the longer-term impacts on non-COVID-19 health outcomes indicative of limited health systems resilience (GAVI, 2020). It has now become evident that COVID-19 is persisting in most countries and without appropriate planning for non-COVID-19 service delivery and recovery from COVID-19 disruptions, excess morbidity and mortality will increase (Barach et al., 2020; Kumar and Kumar, 2021). In addition, the initial WHO COVID-19 preparedness and response guidance released on 4 February 2020 did not explicitly include the maintenance of essential health services as a distinct pillar. The temporal analysis conducted in this study highlights that there were CPRPs under development before the update on 22 May 2020 and some incorporated maintenance of non-COVID-19 health services as distinct pillars or within other pillars of emergency response such as case management. Countries that were found to have updated their plans during and throughout the pandemic showed improved alignment with updates in global COVID-19 planning guidance, including for the maintenance of routine service delivery. Incorporation of activities for maintaining essential health services prior to the explicit inclusion of Pillar 9 in global guidance can, in many cases, be related to previous experience of public health, humanitarian and socioeconomic shocks causing health service disruptions. For example, declines in outpatient visits, malaria treatment, vaccination and primary medical consultation that were observed during the 2014–15 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreaks in West Africa led to the early positioning of essential health service continuity in COVID-19 emergency management planning (e.g. in Liberia and Sierra Leone) (Global Delivery Initiative, 2019; Government of Sierra Leone, 2015; World Health Organization, 2020j). It is too early to tell whether countries’ considerations of early planning for health service continuity had significant impacts on excess mortality and morbidity in the current context. It is also outside the scope of this review to determine the impact of the operationalization of CPRPs on excess mortality and morbidity, which given the limitations in functional health information systems and the quality of epidemiological information available will likely be difficult during the ongoing context and prioritization of COVID-19 mitigation, preparedness and response activities.

Box 4.

A snapshot of good planning practices

While the findings from this review suggest the majority of plans have varying degrees of limitations in their considerations to maintain essential non-COVID-19 health services, there are examples of good practices.

Pakistan’s CPRP strongly aligned with global planning guidance incorporating both emergency response and routine service delivery considerations in tandem. The plan included specific activities for the continuity of essential health services for non-COVID-19 high-priority diseases and safe delivery of primary health care services in the emergency context (Government of Pakistan, 2020). The plan also contained specific and prioritized health system–wide activities beyond the scope of immediate emergency response such as reporting mechanisms for gender-based violence and ensuring service delivery for communicable diseases, vaccination, nutrition, reproductive health including child health and child vaccination, care of vulnerable populations and provision of essential medical products for chronic diseases. The plan also clearly identified its relationship with other multisectoral COVID-19 plans and initiatives such as those related to humanitarian and/or refugee population needs and addressing the socioeconomic consequences of COVID-19. Monitoring, evaluation and reporting arrangements for the planned activities and subactivities (e.g. with indicators) and specific funding requirements with activity breakdowns (e.g. by subactivity linked to indicators) were provided, and responsible entities for the delivery of the activities were identified.

The Federated States of Micronesia’s Ministry of Health’s CPRP released in April 2020 incorporated considerations for the identification and maintenance of non-COVID-19 essential health services with the pillars of emergency response (Government of the Federated States of Micronesia, 2020). The plan adopted a ‘whole-of-government’ approach and clearly identified coordination structures, across government, to enable the capacities and resources required to both respond to COVID-19 and provide routine health services, maintain the operation of hospitals and health facilities and ensure availability of necessary health workforce requirements. The plan outlined measures for moving essential health service delivery to alternative sites out of hospitals if needed. It also linked its activities with other plans, for example, the country’s COVID-19 and Vulnerable Population Mitigation Plan, which considered the essential health services requirement of vulnerable populations including those with noncommunicable diseases, comorbidities, mental health conditions, the elderly and people with disabilities. The Federated States of Micronesia’s CPRP outlined activities to periodically assess the adequacy and quality of services provided to individuals with noncommunicable disease and then address and resolve any issues identified. Specific budgets with line items are identified and categorized by national and subnational regions and by different government departments

The findings from this review were, however, triangulated with available data including results from the WHO’s pulse survey on continuity of essential health services conducted in 2020. We found that 53% (n = 62 countries) of the survey responses to the question, ‘Has your country identified a core set of essential health services to be maintained during the COVID-19 pandemic?’, were consistent with our findings from the CPRPs.

This study indicated HICs and LICs were less likely to consider maintaining essential health services when compared to U/LMICs in CPRP (Figure 5). While the number of HICs represented in this study is small, growing global evidence suggests there were limited consideration for maintaining essential health services in HICs early on in the pandemic (World Health Organization, 2020a; Mansfield et al., 2021). Emerging analysis from 29 HICs with available data indicates that excess mortality substantially exceeded reported deaths from COVID-19 in 2020 with cited factors including substantial increases in non-COVID-19 deaths, which could be the result of disruptions to service delivery (Islam et al., 2021).

From the study, it is observed that there are 35 countries with more than one active CPRP developed by either the government or ministry of health, UN country team and/or WHO country office. No readily discernible trend was observed among countries with multiple plans in relation to their income groups. Plans across different ownership authorities broadly focused on the priorities highlighted within WHO’s SPRP guidance. UN country team plans appeared to consider the maintenance of non-COVID-19 health services more, compared to plans produced by the government or ministry of health and WHO country office, although the proportion of UN country team and WHO country office CPRPs reviewed were small (Table 1). Although there is the perceived risk of inefficiency in the use of limited resources, the actual effect of the presence of multiple CPRPs was not clear. In particular, data extracted from the CPRPs were not adequate to ascertain the implications for coordination, budgeting, accountability and monitoring in the context of multiple active plans in the same country. This could be an area of interest for further studies. Moving forward, national authorities should appraise the utility of multiple CPRPs and consider bringing them together with operational arrangements that draw on the comparative advantages from different allied stakeholders and partners.

Approximately 2 months before the world’s first suspected case of COVID-19 was announced, the Global Health Security Index broadly ranked HICs highly for preparedness and response. To date, many of the same HICs have reported the highest numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths and service disruptions (Nuclear Threat Initiative and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2019; World Health Organization, 2021). An often cited exception is New Zealand, with its relatively limited COVID-19-related disruptions to essential services and reportedly lower than expected excess deaths from both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 causes in 2020 (Islam et al., 2021). Factors that contribute to limited planning for maintaining essential health services include the political context in which health systems are governed, initial misperception of the magnitude of disruptions, adoption of early mitigation and elimination strategies, ability to rapidly deploy a whole-of-government approach, and chronic disinvestment and limited attention to the importance of essential public health functions and establishing linkages between public health response and clinical care at subnational levels (e.g. local communities and primary care) (Baker et al., 2020; Wenham, 2021).

The ongoing pandemic also revealed limitations between and within countries in translating the lessons learned from past events (SARS in 2002, MERS in 2012 and EVD in 2014–15) into actions that could have supported the capacity of health systems to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. This applies to prepositioning stock and effective supply chain management for personal and protective equipment and essential medicines, diagnostics, therapeutics and medical devices as well as timely sharing of information. The findings from this study do, however, indicate areas of good practice in the context of planning. For example, 92% of CPRPs considered operational support and logistics for essential medical products and 95% included activities related to COVID-19 risk communication to communities and strengthening national laboratories including sharing of laboratory information. Further study is warranted to understand the true impact of these planning considerations, and the application of lessons from past experiences of emergencies, on national and subnational actions and health outcomes.

Country-level response coordination was reflected in almost all the reviewed CPRPs; however, designation of focal points for inputs from the broader health system needed for essential health service delivery was found in less than half. This is for both individual healthcare service delivery and population-based public health services such as immunization and screening. Plans can be improved by ensuring well-defined roles and responsibilities for ensuring broader health services and public health input in emergency coordination structures (e.g. the incident management systems). Coordination structures should also promote the participation of other key actors, including the for-profit and not-for-profit private sectors. Such an approach can reduce COVID-19-related disruptions within and outside the health sector.

The limited reference of CPRPs in ensuring subnational health services, including primary health care, may be indicative of a limited bottom-up and integrated approach to planning. This limits the visibility of gaps in capacities that are present in health systems and public health functions between capital cities’, subnational and district health administration and services. This compromises service provision to hard-to-reach communities and leads to delays in early surveillance, testing, reporting and contact tracing in the context of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases. Integrated, whole-of-society approaches at the national level should be replicated at subnational levels to maximize the contributions of responsible stakeholders (Tanner, 2005). Improved integration of HSS efforts focusing on service delivery at all levels into emergency management planning is key for developing and sustaining resilient health services as well as timely response. Improving subnational level capacity can be supported by service continuity planning in health facilities.

CPRPs widely referred to the IPC measures concerning COVID-19 response. However, quality of health services more broadly was less represented, including aspects of safety (e.g. medication safety), domains of quality beyond safety (e.g. effectiveness or people-centredness) or quality improvement. Ensuring the quality of health services is as important as ensuring their availability (World Health Organization, 2018). A resilient health system has the capacity to maintain quality services to mitigate direct and indirect health impacts of emergencies (Kruk et al., 2015). During the 2014–15 EVD outbreaks in West Africa, there was a dearth of attention to occupational health and safety and quality of services leading to hundreds of health worker deaths, breakdown in community trust in health services, and excess morbidity and mortality (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016; Woskie and Fallah, 2019). Planning in the COVID-19 context and beyond can be improved by covering all pertinent domains of quality in service delivery and strengthening and ensuring linkages with existing quality improvement structures.

A core function of the CPRPs, particularly in low resource settings, was to rapidly mobilize and utilize domestic (whole-of-government and society) and external financial resources for COVID-19 preparedness and response activities. The limited and varied incorporation of dedicated budgets for maintaining essential health services across CPRPs may be reflective of the initially perceived limited risk of health systems in high-resource settings collapsing, while in the LIC context, acute response priorities were the predominant focus to ensure recovery to baseline health service delivery as quickly as possible. Other factors may include limited health systems–wide input in the planning process, including for financing and administrative structures relating to service delivery and contingency planning. Improvements in planning can be made through advocacy and support for a more integrated approach and resource mobilization that will have proactive considerations for reducing service disruptions rather than being reactive to events. The role of the private sector (both for-profit and not-for-profit) and allied departments to the ministry of health (e.g. ministries of finance, defence and/or foreign affairs) can bring in surge capacity in terms of complementary infrastructure, funding and services, which was the case in many countries during the pandemic.

M&E is another critical aspect of planning for the effective and accountable implementation of activities. It can also raise the confidence of the public, taxpayers and donors on planning and response. However, a limited proportion of plans (53%) considered M&E, with many being indicative of ongoing developments of an M&E framework rather than including clearly defined indicators that should be improved upon in updates to plans.

The findings from this study highlight the need for greater focus on strengthening subnational level capacities for service delivery. Consideration for maintaining essential health services at the community or primary care level within plans is limited and predominantly in reference to the provision of COVID-19-related healthcare or a specific type of service (e.g. noncommunicable diseases or mental health). National planning can support local decision-making and enable the maintenance of essential health services at the subnational levels incorporating a primary health care approach. These considerations should be part of the policy process throughout emergency planning and can enable learning towards health systems resilience (World Health Organization, 2020h). Local and participatory decision-making should also feed into recovery planning and broader health and multisectoral efforts for building resilience during and beyond COVID-19. This necessitates continuing multisectoral collaboration, technical support and investment to address persisting gaps in capacities at all levels of the public health and healthcare system.

Study limitations

While this study provides key perspectives on health systems strengthening for non-COVID-19 service delivery and resilience considerations within CPRPs, we recognize the document analysis method deployed has limitations. First, there may be discrepancies between plans and intended actions on the ground. To evaluate this, findings from the CPRPs were triangulated with corresponding data from the WHO pulse survey on continuity of essential health services conducted in 2020, which showed a good degree of consistency with our findings from the CPRPs. This highlights the need for further inquiry and analysis from different sources (e.g. health service utilization data and morbidity and mortality rates) to better understand the reasons behind discrepancies in documents, informants and the impact of planning on health outcomes. Second, the authorship and quality of CPRPs was variable. To limit the effects of this, CPRPs from authoritative sources (i.e. national authorities, WHO country offices and UN country teams) and their updates were analysed. Third, there is the potential for biases both within CPRPs and from the researchers. Where possible, CPRPs were critically evaluated and the subjectivity of the findings tested, for example, by conducting temporal analysis and comparing findings in plans of the same country produced by different authorities. The study protocols were designed to reduce researcher subjectivity, and all findings were verified by at least one other researcher.

Conclusion

This study provides pertinent findings based on a review of 106 countries’ CPRPs, developed in response to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic that has caused significant disruptions to health services worldwide. Although many CPRPs are largely aligned with the relevant global guidance, there is a need to promote operational integration between health service continuity and emergency response through proactive planning with health systems resilience considerations in countries across all income groups. This contributes to reducing health services disruptions and the associated excess mortality and morbidity during emergencies.

In ongoing and future emergency planning, national authorities and their partners should consider the following:

Embedding context-specific considerations for the maintenance of quality, routine and essential, health services within emergency preparedness and response plans and activities. This should consider the local epidemiology, identified gaps and vulnerabilities in health systems capacity and the severity of disruption based on lessons learned from past and ongoing public health emergencies including relevant assessments and multisectoral reviews. Integrated planning, aligned with the local context and evidence base, requires effective implementation at all service delivery levels in order to reap the benefits. This is an area that should be explored through further operational research as part of post-COVID-19 multisectoral reviews.

The current practices in planning suggest that the dedicated participation of entities and persons responsible for health systems strengthening in emergency management and operations are largely ad-hoc and reactive. This should be addressed by defining their roles and mechanisms for engagement in pre-emergency national planning and in the development of response plans. In the long term, national policies should be oriented to build health systems resilience for maintenance of essential health services in all contexts including disruptive emergencies.

The protection of population health cannot be ensured if planning does not address prevailing gaps in health service delivery between national and subnational levels due to variability in investment and public health infrastructure. This also corroborated with our study findings that suggested limited explicit planning consideration for subnational health services in CPRPs. Focused attention is needed to maintain essential health services at subnational levels including primary health care and community-based services through equitable investment and effective participation of local stakeholders (e.g. communities, civil society and the private sector—both for-profit and non-profit).

Due to the acute infectious nature of COVID-19, the explicit focus of planning was on IPC. Consideration of other domains of quality and safety in health services is necessary to ensure improved community engagement, trust and utilization of essential health services.

Given the severity of the impact of COVID-19, countries have been limited in their ability to maintain functional, integrated health information systems and to monitor excess mortality and morbidity. There is also reduced demand for and ability to access essential health services. Moving forward, planning and frontline activities for maintaining essential health services should have proportionate considerations and M&E indicators that will track the maintenance of essential health services alongside emergency-specific healthcare.

COVID-19 presents both an immense challenge and an opportunity. National authorities and their partners should systematically appraise the performance of their policies, planning, resources and structures in place before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. An integrated approach to planning should be pursued as health systems recover from COVID-19 disruptions. Given the anticipated reductions in funding availability due to widespread economic downturn, there is a need to bring synergies in investment and planning so that the health system can effectively serve its multiple purposes, i.e. progress towards achieving universal health coverage, improved health security, and better health and well-being. By using the current political impetus and the whole-of-society approach to health that COVID-19 has brought about, there is a window of opportunity for all to build better, fairer health systems ready for the complex and diverse health needs of the twenty-first century.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for providing comments and suggestions.

We appreciate WHO member states, country and regional offices, and UN country teams for developing, sharing and/or making CPRPs publicly available. We thank the following colleagues from the WHO country offices, regional offices and headquarters for their support in the study: Rajesh Sreedharan, Dave Lowrance, Nana Mensah Abrampah, Dirk Horemans, Paul Rogers, Mazuwa Banda, Alaka Singh, Awad Mataria, Bente Mikkelsen, Denis Porignon, Devora Kestel, Erin Kenney, Felicitas Zawaira, Gabriele Pastorino, Gerard Schmets, James Fitzgerald, Jonas Gonseth-Garcia, Jorge Castro, Manoj Jhalani, Kathryn O’Neill, Martin Taylor, Matthew Neilson, Meg Doherty, Melanie Cowan, Melitta Jakab, Natasha Azzopardi Muscat, Nedret Emiroglu, Ogochukwu Chukwujekwu, Olga Fradkina, Peter Cowley, Prosper Tumusiime, Rana Hajjeh, Ruitao Shao, Shams Syed, Suraya Dalil, Stella Chungong, Wagawatta Liyanage Sugandhika Padmini Perera and Zsuzsanna Jakab.

Annex 1

First-tier review protocol

The protocol was developed to guide the review of countries’ COVID-19 Preparedness and Response Plans (CPRPs). The guiding questions were used to gather information on the alignment of CPRPs with SPRP pillars and GHRP strategic priorities, consideration of maintenance of essential health services in COVID-19 preparedness and response activities, including budgeting and monitoring and evaluation in the plans.

Review based on the questions can be completed by (1) answering if the main question is addressed; (2) indicating the details that how the question was addressed in the plan (if applicable) and (3) providing original text in the plan that supported the answer for verification by different reviewers.

Annex 2

Second-tier essential health services review protocol

The protocol was developed to guide the deep dive review of CPRPs that considered maintenance of essential health services. The questions can be used to gather information on the alignment of CPRPs with the 14 components in ‘Maintaining Essential Health Services: Operational Guidance for the COVID-19 Context’.

Review based on the questions can be completed by (1) answering if the main question is addressed; (2) indicating the details that how the question was addressed in the plan (if applicable) and (3) providing original text in the CPRP that supported the answer for verification by different reviewers.

Contributor Information

Saqif Mustafa, Universal Health Coverage and Life Course, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Yu Zhang, Universal Health Coverage and Life Course, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Zandile Zibwowa, Universal Health Coverage and Life Course, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Redda Seifeldin, Universal Health Coverage and Life Course, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Louis Ako-Egbe, World Health Organization Country Office, Monrovia, Liberia.

Geraldine McDarby, Universal Health Coverage and Life Course, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Edward Kelley, Universal Health Coverage and Life Course, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Sohel Saikat, Universal Health Coverage and Life Course, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Funding

None declared.

Contributors

S.S. and S.M. conceptualized and designed the study. S.M. led the data searches, data extraction, quality appraisal and synthesis. S.M., Y.Z., L.K.E., Z.Z. and R.S. conducted the document reviews and analysis and verified the data. S.M. and Y.Z. drafted the manuscript. G.M., R.S., E.K., Z.Z. and L.K.E. provided reviews of the manuscript. S.S. reviewed the manuscript and provided key intellectual input to the synthesis and interpretation of findings and supervised the entire study process.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this type of study is not required.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The perspectives expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the decisions or the policies of the World Health Organization.

References

- Baker MG, Wilson N, Anglemyer A. 2020. Successful elimination of Covid-19 transmission. New England Journal of Medicine 383: e56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barach P et al. 2020. Disruption of healthcare: will the COVID pandemic worsen non-COVID outcomes and disease outbreaks? Progress in Pediatric Cardiology 59: 101254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2016. Impact of Ebola on the Healthcare System. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- GAVI . 2020. Overcoming the COVID-19 Disruption to Essential Health Services. 30 October 2020. https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/overcoming-covid-19-disruption-essential-health-services, accessed 26 May 2021.

- Global Delivery Initiative . 2019. Building a More Resilient Health System after Ebola in Liberia. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Pakistan . 2020. Pakistan Preparedness & Response Plan COVID-19, Islamabad: Government of Pakistan. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/PAKISTAN-Preparedness-and-Response-Plan-PPRP-COVID-19.pdf, accessed 1 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Sierra Leone . 2015. National Ebola Recovery Strategy for Sierra Leone. Freetown: Government of Sierra Leone. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Federated States of Micronesia . 2020. FSM COVID-19 Response Framework. COVID-19 Contingency Plan for Federated States of Micronesia. Palikir: Government of the Federated States of Micronesia. https://gov.fm/files/FSM_COVID-19_Response_Framework.pdf, accessed 1 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Haldane V et al. 2021. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from 28 countries. Nature Medicine 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam N, Shkolnikov VM, Acosta RJ et al. 2021. Excess deaths associated with Covid-19 pandemic in 2020: age and sex disaggregated time series analysis in 29 high income countries. BMJ 373: n1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluge H, Martín-Moreno JM, Emiroglu N et al. 2018. Strengthening global health security by embedding the International Health Regulations requirements into national health systems. BMJGlobalHealth 3: e000656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk ME, Myers M, Varpilah ST, Dahn BT. 2015. What is a resilient health system? Lessons from Ebola. The Lancet 385: 1910–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J, Kumar P. 2021. COVID-19 pandemic and health-care disruptions: count the most vulnerable. The Lancet 9: E722–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal A, Erondu NA, Heymann DL et al. 2021. Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. The Lancet 397: 61–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield KE, Mathur R, Tazare J et al. 2021. Indirect acute effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health in the UK: a population-based study. The Lancet Digital Health 3: e217–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuclear Threat Initiative and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health . 2019. Global Health Security Index: Building Collective Action and Accountability, October 2019. New York: Nuclear Threat Initiative and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer N, Agyepong I, Ottersen T et al. 2020. ‘It’ s far too complicated’: why fragmentation persists in global health. Globalization and Health 16: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner M. 2005. Strengthening district health systems. Bulletin of the WHO 83: 403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumusiime P, Karamagi H, Titi-Ofei R, Amri M. 2020. Building health system resilience in the context of primary health care revitalization for attainment of UHC: proceedings from the Fifth Health Sector Directors’ Policy and Planning Meeting for the WHO African region. BMCProceedings 14: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . 2020. A UN Framework for the Immediate Socio-Economic Response to COVID-19, April 2020. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs . 2020a. Global Humanitarian Response Plan for COVID-19, 28 March 2020. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs . 2020b. Global Humanitarian Response Plan for COVID-19: July Update, 16 July 2020. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs . 2020c. Global Humanitarian Response Plan for COVID-19: May Update, 11 May 2020. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Wenham C. 2021. What went wrong in the global governance of Covid-19? BMJ 372: n303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf SH et al. 2020. Excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes, March-July 2020. JAMA 324: 1562–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . 2020. New World Bank Country Classifications by Income Level: 2020–2021. https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2020-2021, accessed 1 October 2020.

- World Health Organization . 2018. Handbook for National Quality Policy and Strategy: A Practical Approach for Developing Policy and Strategy to Improve Quality of Care. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020a. Pulse Survey on Continuity of Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Interim Report, 27 August 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020b. Maintenance of Routine and Essential Health Services During Emergencies. https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/health-service-resilience/essential-services-during-emergencies, accessed 1 September 2020.

- World Health Organization . 2020c. 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-ncov): Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan, 4 February 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020d. COVID-19 Strategic Preparedness and Response: Monitoring and Evaluation Framework, Draft Updated on 5 June 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020e. COVID-19 Strategic Preparedness and Response: Operational Planning Guidance to Support Country Preparedness and Response, Draft Updated on 22 May 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020f. COVID-19 Strategy Update, 14 April 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020g. COVID-19: Operational Guidance for Maintaining Essential Health Services during an Outbreak: Interim Guidance, 25 March 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020h. Maintaining Essential Health Services: Operational Guidance for the COVID-19 Context: Interim Guidance, 1 June 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020i. What Is Early Recovery? Ebola: Health Systems Recovery. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020j. Investing in and Building Longer-term Health Emergency Preparedness during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Interim Guidance for WHO Member States, 6 July 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2021. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/, accessed 26 May 2021.

- Woskie L, Fallah M. 2019. Overcoming distrust to deliver universal health coverage: lessons from Ebola. BMJ 366: l5482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.