Abstract

Background

The spread of severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) among active workers is poor known. The aim of our study was to evaluate the seroprevalence of immunoglobulin G (IgG) among a convenience sample of workers and to identify high-risk job sectors during the first pandemic way.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study among workers tested for SARS-CoV-2 between 28 March and 7 August 2020, recorded by a private healthcare center located in North-West Italy. Association among seroprevalence and demographic and occupational variables was evaluated using chi square test and the seroprevalence and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated.

Results

We collected the results for 23568 serological tests from a sample of 22708 workers from about 1000 companies. Median age was 45 years and about 60% of subjects were male. The overall seroprevalence was 4.97% [95%CI 4.69–5.25]. No statistical difference was found among gender while seroprevalence was associated with subjects’ age, geographical location, and occupational sector. Significantly higher values of positivity were observed for the logistics sector (31.3%), weaving factory (12.6%), nursing homes (9.8%), and chemical industry (6.9%) workers. However, we observed some clusters of cases in single companies independently from the sector.

Then, a detailed focus on 940 food workers shown a seroprevalence of 5.21% [95%CI 3.79–6.63] and subjects who self-reported COVID-19 symptoms and who worked during lockdown had a higher probability of being infected (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Data obtained might be useful for future public health decision; more than occupation sector, it seems that failure on prevention system in single companies increase the SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Keywords: seroprevalence, workers, SARS-CoV-2

What’s Important About This Paper?

The effect of severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral circulation among active workers is poor known. Between March 28 and August 7 in North-West Italy, the proportion of SARS-CoV-2 positive workers was 4.97%, and significant differences were found among occupational sectors, with the highest seroprevalences in logistics (31.25%). However, single companies (independently of the sectors) may have had an important role in SARS-CoV-2 transmission, as clusters were detected. This indicates the need for infection prevention in workplaces.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was identified in December 2019, as the cause of the illness designated Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (Zhu et al., 2020). Due to its rapid spread across the world, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global pandemic on 11 March 2020. On March 9, while the rate of diagnoses was steeply rising, the Italian Government decided to shut down all unnecessary activities, and to apply a strict lockdown order (Presidente del consiglio dei Ministri, 2020). During lockdown periods, many non-essential companies temporarily reduced or completely stopped their production. After 2 months of lock-down, a ‘2nd phase’ started on May the 4th, with partial reopening of commercial activities, and less stringent restrictions to mobility.

To allow for safe and sustained re-opening, the antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 can play an important role in providing epidemiological information and understand how many workers are potentially immune. Moreover, they can help to estimate the burden of SARS-CoV-2 among different sector and identify jobs with higher risk of infection. Despite general population-based seroepidemiological surveys were done (Chen et al., 2021) and many studies were conducted focusing on healthcare workers (Galanis et al., 2020), few studies were available on the other specific worker sectors (Alali et al., 2020; Caban-Martinez et al., 2020; Chughtai et al., 2020; Halatoko et al., 2020; Lopez et al., 2020; Payne et al., 2020; Jerković et al., 2021; Lewnard et al., 2021; Ortiz-Prado et al., 2021). In Italy, a seroprevalence survey involving 64660 subjects was conducted between May 25 and July 15 by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) and reported an overall seroprevalence of 2.5%, even if there is high variability among regions, with values of 3.0% [95% CI 2.2–3.8] and 7.5% [95%CI 6.8–8.3] of positive proportion in Piedmont and Lombardy, respectively (Northern western Italian regions) (Istat, 2020). ISTAT investigated also the differences among jobs, and they found that healthcare workers were the most affected (5.6%), followed by those involved in the food sector (4.2%). However, no more details were available and specific sector categorization was not reported.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin G (IgG) among a convenience sample of workers at multiregional level, and to identify the high-risk job sectors during the first pandemic wave. Secondary aim was to evaluate seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in the food sector, with particular attention to the Italian coffee industry.

Methods

This study analyzed the data of more than 220000 workers tested for SARS-CoV-2 between 28 March and 7 August 2020, recorded by the private healthcare center ‘Centro Polispecialistico Privato Medicina del Lavoro’ (CDC) that is located in North-West Italy (Piedmont region). Particularly, during the first pandemic wave, several firms organized screening programs for their employees including also people who worked from home. Workers who volunteering decided to participate were firstly interviewed by medical doctor who recorded demographic data, secondly a blood sample was obtained and analyzed in the laboratories.

Anonymous demographic (age and gender) and occupational data (company name, address, occupational sector) were available for all subjects. Moreover, each industry was classified by two local experts into different occupational sectors. For people who worked in a big coffee company we also recorded the presence of symptoms (headache, cough, congestion, nausea, loss of taste/smell, fever or chills, fatigue, shortness of breath/difficulty breathing, muscle/body aches, diarrhea, sore throat), previous personal and familial COVID-19 diagnosis, children cohabitation, specific occupational information such as opening during lockdown or contact with the public.

The anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies were assessed using the ZEUS ELISA SARS-CoV-2 IgG Test System, that is an Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) intended for the qualitative detection of IgG antibodies to the SARSCoV-2 virus in human serum and plasma (dipotassium EDTA, lithium heparin, and sodium citrate) (Pérez-López and Mir, 2021). Positive or negative results were established by the following cut-off: ≤0.9 and ≥1.10, and sensitivity and specificity were 93.3% [95% CI 78.7–98.2] and 100% [95%CI 94.8–100], respectively. Workers could have more than one test, the repetition was performed if an equivocal result was obtained or for other reasons. If subject had both positive and negative tests, the positive one was considered. Finally, for some workers, data on Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) on nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs, was recorded.

Descriptive statistical analyses were conducted for the results of serological tests in separate categories of workers. We reported absolute and relative frequencies (%) for categorical variables while mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) were used for numerical ones based on normality assumption. To compare associations between test positivity and other variables, the chi-square/Fisher tests were used, as appropriate. The seroprevalence 95% confidence intervals [95% CI] were also calculated for all subjects and separately for each occupational sector. A map based on distribution of seroprevalence among provinces was drawn. Significance level was set at p < 0.05 and data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and R software.

Results

From 28 April to 7 August 2020, we collected the results for 23568 serological tests from a convenience sample of 22708 workers from about 1000 companies; for 463 individuals more than one test was performed. About 60% (n = 13613) of the participants were men with median age of 45 [IQR 36–52] years. The majority of subjects worked in Torino (41.0%), Biella (14.1%), Cuneo (12.2%), and Novara (8.0%); while the remaining were located in other Piedmont or North-Western Italian counties.

Overall, 1129 workers had SARS-CoV-2 IgG positive measurements and the estimated seroprevalence was 4.97% [IC 95% 4.69–5.25]. Seroprevalences by general demographic characteristics are reported in Table 1. No statistical difference was found between genders (p-value 0.5005), while seroprevalence significantly increased with subjects’ age (p-value 0.0019).

Table 1.

Seroprevalence (and 95% confidence intervals) of SARS-CoV-2 IgG among workers by demographic and occupational characteristics.

| Variable | Number of participants (N = 22708) | Positive (N = 1129) | Seroprevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N | Prevalence [95% CI] | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 9’095 (40.1) | 463 | 5.09 [4.64–5.54] |

| Male | 13613 (59.9) | 666 | 4.89 [4.53–5.25] |

| Age, years | |||

| <20 | 166 (0.7) | 5 | 3.01 [0.41–5.61] |

| 20–29 | 2590 (11.4) | 144 | 5.56 [4.68–6.44] |

| 30–39 | 4697 (20.7) | 213 | 4.53 [3.94–5.13] |

| 40–49 | 7355 (32.4) | 345 | 4.69 [4.21–5.17] |

| 50–59 | 6225 (27.4) | 318 | 5.11 [4.57–5.68] |

| 60–69 | 1353 (6.0) | 73 | 5.40 [4.19–6.60] |

| 70–79 | 263 (1.2) | 24 | 9.13 [5.65–12.61] |

| 80+ | 59 (0.3) | 7 | 11.86 [3.61–20.12] |

| Province | |||

| Other | 426 (1.9) | 7 | 1.64 [0.44–2.85] |

| Aosta | 475 (2.1) | 13 | 2.74 [1.27-0.75] |

| Varese | 36 (0.2) | 1 | 2.78 [0.07–14.53] |

| Asti | 888 (3.9) | 31 | 3.49 [2.28–4.70] |

| Cuneo | 2769 (12.2) | 108 | 3.90 [3.18–4.62] |

| Biella | 3205 (14.1) | 127 | 3.96 [3.29–4.64] |

| Milano | 1211 (5.3) | 60 | 4.95 [3.73–6.18] |

| Torino | 9310 (41.0) | 466 | 5.01 [4.56–5.45] |

| Verbania | 256 (5.4) | 15 | 5.86 [2.98–8.74] |

| Genova | 46 (0.2) | 3 | 6.52 [1.37–17.90] |

| Novara | 1805 (8.0) | 121 | 6.70 [5.55–7.86] |

| Alessandria | 995 (4.4) | 67 | 6.73 [5.18–8.29] |

| Vercelli | 1234 (5.4) | 99 | 8.02 [6.51–9.54] |

| Brescia | 20 (0.1) | 3 | 15.00 [0.00–30.65] |

| Bergamo | 32 (0.1) | 8 | 25.00 [11.46–43.40] |

| Occupational sector | |||

| Printing house | 115 (0.5) | 3 | 2.61 [0.00–5.52] |

| Agriculture | 359 (1.6) | 10 | 2.79 [1.08–4.49] |

| Food services | 205 (0.9) | 6 | 2.93 [0.62–5.23] |

| Information technology | 489 (2.2) | 17 | 3.48 [1.85–5.10] |

| Other manufacturing | 2061 (9.1) | 75 | 3.64 [2.83–4.45] |

| Mechanical engineering | 2577 (11.4) | 102 | 3.81 [3.08–4.53] |

| Iron and steel industry | 284 (1.3) | 12 | 4.23 [1.89–6.56] |

| Publishing industry | 46 (0.2) | 2 | 4.35 [0.00–10.24] |

| Transportation | 275 (1.2) | 12 | 4.36 [1.95–6.78] |

| Holding and insurance company | 4123 (18.2) | 192 | 4.66 [4.01–5.30] |

| Public administration | 235 (1.0) | 11 | 4.68 [1.98–7.38] |

| Construction industry | 976 (4.3) | 46 | 4.71 [3.38–6.04] |

| Plant engineering | 546 (2.4) | 26 | 4.76 [2.98–6.55] |

| Trade | 1183 (5.2) | 57 | 4.82 [3.60–6.04] |

| Other services | 2893 (12.8) | 145 | 5.01 [4.22–5.81] |

| Food industry | 1994 (8.8) | 101 | 5.07 [4.10–6.03] |

| Health services | 1115 (4.9) | 58 | 5.20 [3.90–6.51] |

| Mechanic workshop | 553 (2.4) | 29 | 5.24 [3.39–7.10] |

| Cleaning company | 75 (0.3) | 4 | 5.33 [0.25–10.42] |

| Education | 147 (0.7) | 9 | 6.12 [2.25–10.00] |

| Municipality | 16 (0.1) | 1 | 6.25 [0.00–18.11] |

| Chemical industry | 1025 (4.5) | 71 | 6.93 [5.37–8.48] |

| Food industry—meat | 14 (0.1) | 1 | 7.14 [0.00–20.63] |

| Sports | 111 (0.5) | 9 | 8.11 [3.03–13.19] |

| Clergy | 43 (0.2) | 4 | 9.30 [0.62–17.98] |

| Nursing home | 757 (3.3) | 74 | 9.78 [7.66–11.89] |

| Weaving factory | 373 (1.7) | 47 | 12.60 [9.23–15.97] |

| Logistics | 16 (0.1) | 5 | 31.25 [8.54–53.96] |

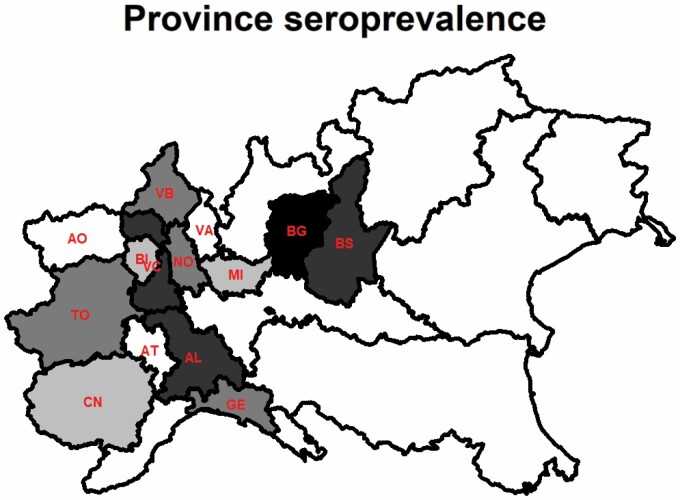

Geographical location was significantly associated with the presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (p < 0.001); details on seroprevalence across provinces are reported in Fig. 1. Despite few workers came from the provinces of Bergamo (n = 32) and Brescia (n = 20), these were the most affected areas, with prevalences of 25% and 15%, respectively. Significantly higher prevalences were observed for workers from Novara (6.70%, 95%CI 5.55–7.86), Alessandria (6.73%, 95%CI 5.18–8.29), and Vercelli (8.02%, 95%CI 6.51–9.54).

Figure 1.

Map of seroprevalence of workers. Colors indicate lower and higher prevalence based on quartiles.Province abbreviation: AO = Aosta, Varese = VA, Asti = AT, Cuneo = CN, Biella = BI, Milano = MI, Torino = TO, Verbania = VB, Genova = GE, Novara = NO, Alessandria = AL, Vercelli = VC, Brescia = BS, Bergamo = BG. .

A significant association was also found between seroprevalence and occupational sectors (p < 0.0001). Significantly higher values of seroprevalence were observed for the logistics sector (31.25%, IC95% 8.54–53.96) and weaving factory (12.6%, IC95% 9.23–15.97) workers. However, in the first group the 95% CI were very wide due to low numbers of subjects analyzed (n = 16), whereas in the second group possible clusters of infected cases were suggested, since in two weaving companies 41.5% and 9.9% of subjects (27/65, 9/91) were IgG positive. The health care workers, involved in private health services and private nursing homes, had IgG positive proportions of 5.20% [95%CI 3.90–6.51] and 9.78% [95%CI 7.66–11.89], respectively. In three nursing homes serological positivity was higher than 25% with 22/57 (38.6%), 10/32 (31.3%) and 7/28 (25.0%) positive subjects. Also in the chemical industry widespread of infection was observed with a prevalence of positive IgG of 6.93% [95%CI 5.37–8.48], with peaks of 81.8% and 46.2% in two small companies (9/11, 6/13). Conversely, significant low prevalences were found in agriculture (2.79%, 95%CI 1.08–4.49), mechanical engineering (3.38%, 95%CI 2.59–4.16), and other manufacturing sector (3.64 95%CI 2.83–4.45). Finally, subjects involved in the food industry had a mean seroprevalence close to 5%, with important differences, since in some plants we observed more than 13% of positive workers (14/106 = 13.2% and 14/99 = 14.1%).

Four thousand three hundred sixty-six NP swabs were performed for the search of SARS-CoV-2 virus after the result of the serological test: 1101 (97.5%) in positive subjects and 3265 (15.1%) in negative ones. Interestingly, only among 15 (1.4%) subjects out of 1101 positive to the serological test, the virus was found in NP swabs.

A more detailed focus on 940 coffee manufacturing workers was also performed. Among 49 subjects, SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were detected with an estimated prevalence of 5.21% [IC 95% 3.79–6.63]. Data on NP swabs was also available for all subjects, but the virus was detected only in one case. [Table 2]. No statistical difference was observed comparing test results separately by gender, age, familial COVID-19 diagnosis, cohabitation with children and contact with the public (p-value > 0.05). However, the 629 subjects who self-reported COVID-19 symptoms (p-value < 0.0001) and the 274 who worked during the lockdown (p-value 0.0049), had a higher probability of being infected. Nineteen workers without symptoms were positive, indicating that they were probably asymptomatic carriers; interestingly 8 of them (8/19, 42.1%) worked during the lockdown period. When we considered the self-declaration of previous COVID-19 diagnosis we observed that: among the subjects who declared COVID-19 diagnosis (n = 2), only one had positive results while in the remaining 937 workers, 47 (5.0%) tested positive. Finally, considering the different branches of this food company, 4 (20.0%) of 20 subjects who worked in catering services were positive to the serological test.

Table 2.

Seroprevalence (95% confidence intervals) of SARS-CoV-2 IgG among 940 coffee manufacturing workers by demographic, clinical, and occupational characteristics.

| Variable | Number of participants (N = 940) | Positive (N = 49) | Seroprevalence [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 410 (43.6) | 19 | 4.63 [2.60–6.67] |

| Male | 530 (56.4) | 30 | 5.66 [3.69–7.63] |

| Age (years) | |||

| 20–29 | 133 (14.2) | 10 | 7.52 [3.04–12.00] |

| 30–39 | 281 (29.9) | 13 | 4.63 [2.49–7.78] |

| 40–49 | 290 (30.9) | 14 | 4.83 [2.36–7.29] |

| 50–59 | 214 (22.8) | 9 | 4.21 [1.52–6.89] |

| 60–69 | 22 (2.3) | 3 | 13.64 [0–27.98] |

| COVID-19 symptoms | |||

| No | 671 (71.4) | 19 | 2.83 [1.58–4.09] |

| Yes | 269 (28.6) | 30 | 11.15 [7.39–14.91] |

| COVID-19 diagnosis (N = 939) | |||

| No | 937 (99.8) | 47 | 5.02 [3.62–6.41] |

| Yes | 2 (0.2) | 1 | - |

| Familiar COVID-19 diagnosis | |||

| No | 920 (97.9) | 47 | 5.11 [3.69–6.53] |

| Yes | 20 (2.1) | 2 | 10.00 [0.00–23.15] |

| Children cohabitation | |||

| No | 511 (54.5) | 26 | 5.09 [3.18–6.99] |

| Yes | 426 (45.5) | 22 | 5.16 [3.06–7.27] |

| Working during lockdown | |||

| No | 666 (70.9) | 26 | 3.90 [2.43–5.37] |

| Yes | 274 (29.2) | 23 | 8.39 [5.11–11.68] |

| Public contact | |||

| No | 925 (98.4) | 47 | 5.08 [3.67–6.50] |

| Yes | 15 (1.6) | 2 | 13.33 [0.00–30.54] |

Discussion

The objective of the present study was to describe the distribution of prevalence of immunoglobulins for SARS-CoV-2 in a convenience sample of more than 22000 workers in a North-North-Western Italian region. The proportion of positive workers between 28 April and 7 August 2020 was 4.97% [95% CI 4.69–5.25]. Significant differences were found among occupational sectors: higher seroprevalences were recorded in logistics, weaving factories, nursing home workers and chemical industry, while agriculture, mechanical engineering and other manufacturing industries showed lower prevalence values. However, when we conducted in-depth analyses, we observed that single companies (independently of the sectors) may have had an important role in SARS-CoV-2 transmission, as clusters of cases were detected.

Despite using a convenience sample that cannot be considered representative of the Italian worker population, we are working with data provided by a very large health company surveying. Similarly to the national survey (3% in Piedmont and 7.5% in Lombardy), our overall seroprevalence estimate was 4.97% and we found that occupation is an important factor associated with presence of IgG antibodies (Istat, 2020). Furthermore, we identified the healthcare sector (nursing homes workers—9.78% and healthcare assistants—5.20%) as high-risk categories, and we observed that the seroprevalence in food industry was higher than other sector (5.07%). Other national studies were conducted among hospital healthcare workers in the same Italian provinces and the prevalence ranged from 5.13% to 8.62% (Amendola et al., 2020; Paderno et al., 2020; Sotgiu et al., 2020; Calcagno et al., 2021), coherent with our estimates. Only in one study an extreme value of 17.11% was observed (Airoldi et al., 2021). Finally, in an Italian study (Vena et al., 2020) conducted in March–April 2020 (n = 3609) in close geographical area, the authors observed that occupational exposures and living in a long-term care facility increased the probability of being seropositive with Odds Ratios of 2.60 [95%CI 1.76–3.88] and 7.56 [95%CI 5.58–10.23], respectively. These results support the idea that our sample was representative of the study population investigated, with both occupational sectors and geographical gradient related to seroprevalence.

Comparisons with international studies could be done with more attention, to avoid risk of bias and misinterpretation of data. Particularly, an important role in seroprevalence among workers was played by geographical location, timing, different measures taken to contain the news peaks in infections and deaths (West et al., 2020). Workers in agriculture and the food sector across the supply chain were deemed essential to assure continuity of public health and safety, and therefore have continued in-person work (Nakat and Bou-Mitri, 2021). Interestingly, in our sample a significant lower prevalence of 2.79% [95%CI 1.08–4.49] was estimated indicating that this occupational sector was less affected by COVID-19. While in a similar Californian study among farmworkers a higher prevalence of 10.5% was estimated between June–August 2020 (Lewnard et al., 2021), we think that our lower seroprevalence is related to different farm structure. Indeed, USA agriculture draws on a predominantly Latin immigrant workforce with high levels of household poverty, whereas the Northern Italy farms are generally small and family-run. We also analyzed separately the workers in meat industry as prior reports indicated a prevalence of 9.1% of COVID-19 cases among meat and poultry processing facilities (Waltenburg et al., 2020). However, only 14 subjects worked in the meat industry and one of them (7.14%) tested positive. Seroprevalence in the food industry was 5.07% (95%CI 4.10–6.03), but no data on supermarket workers were available, while a high seroprevalence of 36.8% was observed in a study conducted in Kuwait (n = 525) among migrant supermarket workers.(Alali et al., 2020) Other workers not considered in our research were the food delivery riders despite high prevalence of infection (n = 15.2%) was found in bike and motorbike riders in Ecuador (Ortiz-Prado et al., 2021). We noted that people involved in logistics had an increased probability of having SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (31.25%). Possible cause of this high infection rate is the direct contact with multiple people through the journey and handing money, that are considered as a potential risk of virus transmission.(Harbourt et al., 2020) Finally, we identified two occupational sectors at high risk of infection: chemical industry (6.93%) and weaving factories (12.60%). Despite no comparable studies were available in the literature, we suppose that these companies were open during the lockdown period and a minimum social physical distancing was not maintained. Moreover, we assume that notwithstanding workers in chemical industry were generally more used to wear protective equipment regardless of the pandemic, the social interactions during breaks were a possible occasion of infection. Also, after excluding the four industries identified as possible clusters of disease, the prevalence decreased significantly.

Sami et al. conducted a serological survey in public service agencies in New York City during May–June 2020.(Sami et al., 2021) Among 22647 participants, 22.5% had specific SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Despite this prevalence was 4-fold higher than we observed in our sample (4.97%), the two estimates were similar to the seroprevalence for residents in the same area at a comparable date (19.5% in New York City and 3.0/7.5% in Piedmont and Lombardy). Seropositivity was higher among those with exposure to a household member who was positive for SARS-CoV-2. In our analysis data on familial exposure was available only for 940 workers: we found that subjects with familial COVID-19 diagnosis had prevalence twice as high as other subjects, but statistical significance was not attained. No difference was observed in the case of children cohabitation; this result can be explained by the fact that during the lock-down phase, schools were closed and all activities involving children were interrupted. Coherent with our sample, in Sami et al. seroprevalence also varied by occupation; the job categories were slightly different, but a large range of values was observed ranging from 10.1% to 39.2%. In terms of educational sector, in our research 147 teachers were analyzed and a prevalence of 6.12% was observed. Lower values of individuals testing positive (2.9, 95%CI 1.8–4.4) were obtained in a study conducted in the staff of a Public School System in Midwestern United States in July 2020 (Lopez et al., 2020). However, no data on type of school was available (elementary, middle, high, or other) so no inference can be drawn about their contacts with students. Finally, seroprevalence obtained in a study conducted in Togo was completely different as the IgG antibodies were detected in less than 1% of the sample (n = 955). Participants were recruited from five professional sectors (healthcare, air transport, police, road transport, and informal) between April and May 2020 (Halatoko et al., 2020). This difference could be explained by the delayed spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Togo (98 cases was confirmed on April 26) and the various measures taken by the government.

We assumed that the role of companies on SARS-CoV-2 transmission is in part related to the specific internal measures introduced by each industry as for example hand disinfection stations and regular workstation cleaning protocols, plus restrictions in communal coffee and food vending stations. A study conducted in 1494 adults employed in a Croatian company, showed a seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies of 1.27% [95% CI 0–3.37] (Jerković et al., 2021). They demonstrated that the epidemic situation within the company could be controlled by the timely implementation of adequate national and corporate measures. Finally, the discordant found among NP swabs and serological test could be explained by different characteristic of tests and they ability to detect presence of SARS-CoV-2 and antibodies, respectively. Moreover, the time course of NP positivity and seroconversion may vary and it’s related to the time of first infection (Sethuraman et al., 2020).

Our study has some limitations. First, the population included was not representative of the general workers as only people who were followed by the CDC centers were included in the analysis. We cannot exclude selection bias in our convenience sample due to the recruitment methods. We had more participants from some sectors (for example from holding and insurance companies) while others were under-represented or not represented at all, probably due to differences in company policies. Second, a possible geographic gradient can be suspected, and a part of high/low prevalence values can be explained by industry location. Particularly, high number of seropositive subjects were observed in Brescia and Bergamo, that were two of the most affected Italian provinces. Third, no data on clinical history and appropriate use of personal protective equipment was available. However, ours is a huge sample and all industries were in North-Western Italian regions, with a similar spread of SARS-CoV-2.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge this is the first Italian study that analyzed different occupational sectors and it contributes to our knowledge in terms of prevalence in a population sub-group, as recommended by WHO. Some sectors appear to be at high risk, consistently with international literature, and have to be considered for more intensive surveillance and prevention intervention are needed in order to reduce viral transmission. However, we observed some clusters of cases independently from industrial sector and it could be related to ineffective prevention measures taken in singular company. Future public health decision-making on emergency lockdowns or return-to-work policies could benefit from our data; they may be used for informing health authorities on the role of work environment in the spread of COVID-19.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicity for the privacy of individuals.

References

- Airoldi C, Patrucco F, Milano Fet al. (2021) High seroprevalence of sars-cov-2 among healthcare workers in a North Italy hospital. Int J Environ Res Public Health; 18. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alali WQ, Bastaki H, Longenecker Jet al. (2020) Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in migrant workers in Kuwait. J Travel Med. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amendola A, Tanzi E, Folgori Let al. (2020) Low seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among healthcare workers of the largest children hospital in Milan during the pandemic wave. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol; 1–2. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caban-Martinez AJ, Schaefer-Solle N, Santiago Ket al. (2020) Epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among firefighters/paramedics of a US fire department: a cross-sectional study. Occup Environ Med. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2020-106676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcagno A, Ghisetti V, Emanuele Tet al. (2021) Risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection in healthcare workers, Turin, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis; 27: 7–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Chen Z, Azman ASet al. (2021) Serological evidence of human infection with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(21)00026-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chunghtai OR, Batool H, Khan MDet al. (2020) Frequency of COVID-19 IgG antibodies among special police squad Lahore, Pakistan. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. doi: 10.29271/jcpsp.2020.07.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanis P, Vraka I, Fragkou Det al. (2021) Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and associated factors in healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Infect. 108:120–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halatoko WA, Konu YR, Gbeasor-Komlanvi FAet al. (2020) Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among high-risk populations in Lomé (Togo) in 2020. PLoS One. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbourt DE, Haddow AD, Piper AEet al. (2020) Modeling the stability of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) on skin, currency, and clothing. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Istat (2020) Primi risultati dell’indagine di sieroprevalenza sul SARS-CoV-2. Available at https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/246156

- Jerković I, Ljubić T, Bašić Žet al. (2021) SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence in industry workers in Split-Dalmatia and Šibenik-Knin County, Croatia. J Occup Environ Med. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewnard JA, Mora AM, Nkwocha Oet al. (2021), Prevalence and clinical profile of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection among farmworkers, California, USA, June-November 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 27: 1330–42. doi: 10.3201/eid2705.204949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez L, Nguyen T, Weber Get al. (2021) Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in the staff of a public school system in the midwestern United States. PLoS One. 10;16: e0243676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakat Z, Bou-Mitri C. (2021) COVID-19 and the food industry: readiness assessment. Food Control. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Prado E, Henriquez-Trujillo AR, Rivera-Olivero IAet al. (2021) High prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among food delivery riders. A case study from Quito, Ecuador. Sci Total Environ. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paderno A, Fior M, Berretti Get al. (2020) SARS-CoV-2 infection in health care workers: cross-sectional analysis of an otolaryngology unit. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. doi: 10.1177/0194599820932162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne DC, Smith-Jeffcoat SE, Nowak Get al. (2020) SARS-CoV-2 infections and serologic Responses from a Sample of U.S. Navy Service Members - USS Theodore Roosevelt, April 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 69:714–21. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-López B, Mir M (2021) Commercialized diagnostic technologies to combat SARS-CoV2: advantages and disadvantages. Talanta; 225(July). doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2020.121898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presidente del consiglio dei Ministri (2020) Italy measures in response to COVID-19, Gazzetta ufficiale. Available at https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/03/09/20A01558/sg. Accessed 1 February 2021.

- Sami S, Akinbami LJ, Petersen LRet al. (2021) Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in first responders and public safety personnel, New York City, New York, USA, May–July 2020. Emerg Infect Dis; 27. doi: 10.3201/eid2703.204340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethuraman N, Jeremiah SS, Ryo A. (2020) Interpreting diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotgiu G, Barassi A, Miozzo Met al. (2020) SARS-CoV-2 specific serological pattern in healthcare workers of an Italian COVID-19 forefront hospital. BMC Pulm Med; 20: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vena A, Berruti M, Adessi Aet al. (2020) Prevalence of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in Italian adults and associated risk factors. J Clin Med. doi: 10.3390/jcm9092780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltenburg MA, Victoroff T, Rose CEet al. (2020) Update: COVID-19 among Workers in Meat and Poultry Processing Facilities - United States, April-May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 69:887–92. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6927e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West EA, Anker D, Amati Ret al. ; Corona Immunitas Research Group. (2020) Corona Immunitas: study protocol of a nationwide program of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and seroepidemiologic studies in Switzerland. Int J Public Health; 65: 1529–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang Wet al. (2020) A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicity for the privacy of individuals.