Abstract

With an aging world population, there is an increased risk of fracture and impaired healing. One contributing factor may be aging-associated decreases in vascular function; thus, enhancing angiogenesis could improve fracture healing. Both bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) and thrombopoietin (TPO) have pro-angiogenic effects. The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of treatment with BMP-2 or TPO on the in vitro angiogenic and proliferative potential of endothelial cells (ECs) isolated from lungs (LECs) or bone marrow (BMECs) of young (3–4 month) and old (22–24 month), male and female, C57BL/6J mice. Cell proliferation, vessel-like structure formation, migration, and gene expression were used to evaluate angiogenic properties. In vitro characterization of ECs generally showed impaired vessel-like structure formation and proliferation in old ECs compared to young ECs, but improved migration characteristics in old BMECs. Differential sex-based angiogenic responses were observed, especially with respect to drug treatments and gene expression. Importantly, these studies suggest that NTN1, ROBO2, and SLIT3, along with angiogenic markers (CD31, FLT-1, ANGPT1, and ANGP2) differentially regulate EC proliferation and functional outcomes based on treatment, sex, and age. Further, treatment of old ECs with TPO typically improved vessel-like structure parameters, but impaired migration. Thus, TPO may serve as an alternative treatment to BMP-2 for fracture healing in aging owing to improved angiogenesis and fracture healing, and the lack of side effects associated with BMP-2.

Keywords: Endothelial Cells, Thrombopoietin, Bone Morphogenetic Protein, Sex-based Differences, Aging

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Bone fractures are painful and disabling injuries that are prevalent in older populations, particularly in patients with osteoporosis. With an aging world population, bone fracture prevalence is expected to increase in the coming years. Similarly, increasing age is also a primary risk factor for impaired fracture healing and elevated pain following fracture repair1,2. Furthermore, delayed fracture healing is associated with increased morbidity and mortality3–5.

Lower bone quality and delayed fracture healing in the elderly can be attributed to numerous physiologic changes caused by aging, especially in the function of peripheral nerves, kidneys, and vasculature1,6,7. Vascular function is known to be crucial for the proper regeneration of bone7,8. Newly formed blood vessels provide the oxygen, nutrients, and key cellular players required by the highly metabolically active callus to achieve bone healing8. Additionally, vascular endothelial cells (ECs) themselves can release osteogenic factors that support osteoblast differentiation, as well as contribute to the maintenance and differentiation of bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells9,10. These interactions emphasize the importance of normal vascular function to bone health and healing.

Within elderly patient populations, impaired fracture healing has been attributed to diminished mesenchymal stem cell differentiation and angiogenesis, which are directly involved with endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs)1. Thus, a decrease in the number or functionality of EPCs, leading to a decrease in angiogenic potential, may be a mechanism behind impaired fracture healing in elderly populations11. In studies of non-elderly populations, increased angiogenic potential has been found to lead to improved fracture healing12,13. One example is the biologic agent bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2), which is FDA approved for stimulating bone healing. In large bone defect models, the induction of neovascularization has been implicated as an additional method by which BMP-2 stimulates bone regeneration14,15. BMP-2 has also been well characterized as a regulator of EC function, proliferation, migration, and vessel formation in various settings, such as postnatal neovascularization, tissue repair, and tumor-associated angiogenesis16–20. However, BMP-2 treatment is associated with a concerning array of clinical side effects in humans, such as postoperative inflammation, heterotopic callus formation, and increased risk of cancer21. Thrombopoietin (TPO), the main megakaryocyte growth factor, has emerged as a novel therapeutic alternative to BMP-2 as it can stimulate bone healing without this side effect profile22. Furthermore, TPO has previously been shown to induce EC motility and angiogenesis through a platelet-activating factor (PAF)-dependent mechanism23. Therefore, both BMP-2 and TPO may have potential therapeutic value in the elderly as angiogenesis-stimulating agents during the fracture repair process.

While it is generally accepted that age and sex influence angiogenic function24–26, it is unclear if the comparative effects of BMP-2 and TPO on EC function are altered in the aging systemic milieu or as a result of sex, and whether there are site-specific differences. Therefore, we investigated the effects of aging, sex, and BMP-2 or TPO administration on the proliferative and angiogenic potential of ECs obtained from multiple sites (lung and bone marrow). Here we characterize and stimulate ECs with BMP-2 or TPO in vitro. Through EC stimulation, the contribution of angiogenic factors and novel bone healing agents can be evaluated in future bone healing models in aged male and female mice.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Animals

Young (3–4 month-old) and old (22–24 month-old), male and female, C57BL/6J mice were provided by the National Institute on Aging. All of the studies described were approved by the Indiana University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2 |. Endothelial Cell Isolation from Lungs and Bone Marrow

ECs from lungs and bone marrow were isolated as previously described27,28. In brief, using aseptic technique, lung tissue was isolated, finely minced, and digested with 225 U/ml collagenase type 2 solution (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ, USA) for 1 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. After digestion, the tissue was filtered through a 70 μm mesh strainer. Subsequently, the cell suspension was incubated with biotin rat anti-mouse CD31-conjugated (BD Pharmingen™, San Jose, CA, USA) Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 1 h at 4°C. Next, the Dynamag 2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to separate CD31+ cells. The CD31+ cells were plated in a collagen I coated 6-well plate (Corning®, Corning, NY, USA), at a density of 3 × 105 cells/ml, in EC Growth Medium 2 (PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany) supplemented with Growth Medium 2 Supplement Mix (PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany) and Penicillin-Streptomycin-Glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Lung ECs (LECs) at passage 2 were used in all experiments.

Bone marrow ECs (BMECs) were isolated and cultured as previously described27. Briefly, bone marrow was isolated from tibiae and humeri of all mice. After stripping bones of all skin, muscle, and connective tissue, distal and proximal epiphyses of each bone were removed. Each bone was then inserted into a punctured 0.5 mL tube placed inside a 1.5 mL tube containing 750 μL of α-MEM (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biowest, Riverside, MO, USA). Bone marrow was extracted by centrifugation (14,000 g for 3 minutes). The resulting pellets were resuspended and cells were plated in a 12-well plate coated with 4 μg/mL fibronectin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in 1–2 mL of Complete EC Growth Media, containing FBS, EC growth supplements, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution. BMECs were cultured for 7 days prior to use in downstream assays.

2.3 |. In Vitro BMP-2 and TPO Treatment

LECs and BMECs were plated as described below. The cells were treated with control (no treatment), recombinant human BMP-2 (50, 100, or 200 ng/mL, Medtronic Sofamor Danek Inc, Memphis, TN, USA), or recombinant human TPO (25, 50, or 100 ng/mL, PeproTech Inc, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA).

2.4 |. Endothelial Cell Immunofluorescence

ECs were cultured to 70–80% confluence and fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (IBI Scientific, Cubuque, IA, USA), cells were stained overnight with anti-CD31/PECAM-1, DyLight 488, Clone: MEC 7.46, antibody (Novus Biologicals™, Centennial, CO, USA) at 4°C at a dilution of 1:500 or anti-N-cadherin recombinant rabbit monoclonal antibody (MA5-32088, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). EC nuclei were stained with 1 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Imaging was performed with the EVOS® FL Cell Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.5 |. Proliferation Analysis

LECs were seeded at a density of 5 × 102 cells/well in a 96 well plate. Cells were fixed in 10% NBF at room temperature for 10 minutes and stained with DAPI (1 μg/ml) for 5 minutes at days 1, 2, and 3. The cells were imaged with the EVOS® FL Cell Imaging System and DAPI positive nuclei were manually counted.

BMECs were seeded in at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well in a 96 well plate, to assess proliferation on days 1, 2, and 3. BMECs were fixed with 5% NBF at room temperature for 20 min, stained with 0.05% crystal violet for 30 minutes, and washed under tap water before drying overnight. Imaging was done with the EVOS® FL Cell Imaging System and counted using ImageJ.1.52a software29.

2.6 |. Vessel-like Structure Formation Assay

EC vessel-like structure formation was assessed as previously described15. In brief, 50 μl/well of Matrigel basement membrane matrix (Corning®, Corning, NY, USA) was added to 96 well plates and incubated for 45 minutes at 37°C before ECs were plated and cultured. At each respective passage/growth duration previously mentioned, ECs were plated on the Matrigel, suspended in their respective growth medium, at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well (or in some studies at higher densities of 2 × 104 and 4 × 104). Cells were then incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2. Imaging was done after 6 hours or 8 hours for LECs and BMECs, respectively. ImageJ.1.52a software was used to quantify vessel-like formation. The following data parameters were collected: number of nodes, number of meshes, number of complete vessels, and total vessel-like structure length. Angiogenesis Analyzer, an automated plugin of ImageJ.1.52a, analyzed the number of nodes and the number of meshes. Simple Neurite Tracer, a plugin of ImageJ.1.52b Fiji software30,31, facilitated manual measurement for the number of complete vessels and the total vessel length by three independent readers blinded to group identity.

2.7 |. Wound Migration Assay

ECs were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well in a 96-well plate and grown for 24 hours until they were 100% confluent. The IncuCyte® WoundMaker (Essen BioScience, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was used to create a wound in the middle of each well. The IncuCyte ZOOM® Live-Cell Analysis System (Essen BioScience, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) imaged ECs at time 0 and every 2 hours for 50 hours at 10X magnification. The IncuCyte™ Scratch Wound Cell Migration Software (Essen BioScience, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was used to analyze the images.

2.8 |. Gene Expression

Total RNA isolation was performed using the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Subsequently, cDNA was prepared using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The prepared cDNA was analyzed by quantitative PCR using Power SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) on a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The genes analyzed include: CD31 Antigen (CD31), Fms Related Tyrosine Kinase (FLT-1), Angiopoietin 1 (ANGPT1), Angiopoietin 2 (ANGPT2), Netrin-1 (NTN1), Roundabout Guidance Receptor 2 (ROBO2), and Slit Guidance Ligand 3 (SLIT3) (Table 1). GAPDH served as an internal control. Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

TABLE 1.

Quantitative PCR primer sequences.

| Reverse | ||

|---|---|---|

| CD31 | 5′-ACGCTGGTGCTCTATGCAAG-3′ | 5′-TCAGTTGCTGCCCATTCATCA-3′ |

| FLT-1 | 5′-CCACCTCTCTATCCGCTGG-3′ | 5′-ACCAATGTGCTAACCGTCTTATT-3′ |

| ANGPT1 | 5′-CACATAGGGTGCAGCAACCA-3′ | 5′-CGTCGTGTTCTGGAAGAATGA-3′ |

| ANGPT2 | 5′-CCTCGACTACGACGACTCAGT-3′ | 5′-TCTGCACCACATTCTGTTGGA-3′ |

| NTN1 | 5’-GTGAGGGGCAGAATGTCCAGA-3’ | 5’-CTTGCGGCAGTAGATGAGGA-3’ |

| ROBO2 | 5’-ATTCGGAAGGTGACTGCTGG-3’ | 3’-TTACAACGAAATGTGGCGGC-5’ |

| SLIT3 | 5’-GCTAAGATCCCTCCGAGTGC-3’ | 3’-CCAGGTGGGAAAGGGATGTC-5’ |

| GAPDH | 5′-CGTGGGGCTGCCCAGAACAT-3′ | 5′-TCTCCAGGCGGCACGTCAGA-3′ |

2.9 |. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 8.0.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com). Where appropriate, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test was used to identify statistically significant differences between groups. Alternatively, a Student’s t-test was performed to find the mean difference between the two groups. Statistical significance was determined as p<0.05 and data is represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of the biological replicates (separate experiments with cells from different animals). All experiments were conducted with 3 or more biological replicates (n=3–11, as detailed in each figure legend) and triplicate or quadruplicate wells/technical replicates were averaged for each biological replicate.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. EC Characterization

LECs and BMECs were assessed for mRNA expression of CD31 as a result of treatment, age, and/or sex. As expected, CD31 expression was observed in all groups (Supplemental Figure 1A&B). The ECs also expressed the characteristic CD31 marker on their cell membranes as demonstrated by immunocytochemistry (Supplemental Figure 1C). Further, ECs were able to form vessel-like structures as illustrated in Supplemental Figure 1D, demonstrating that these sets of primary cells exhibit properties of ECs in vitro.

3.2 |. Proliferation of ECs Isolated from Lungs and Bone Marrow

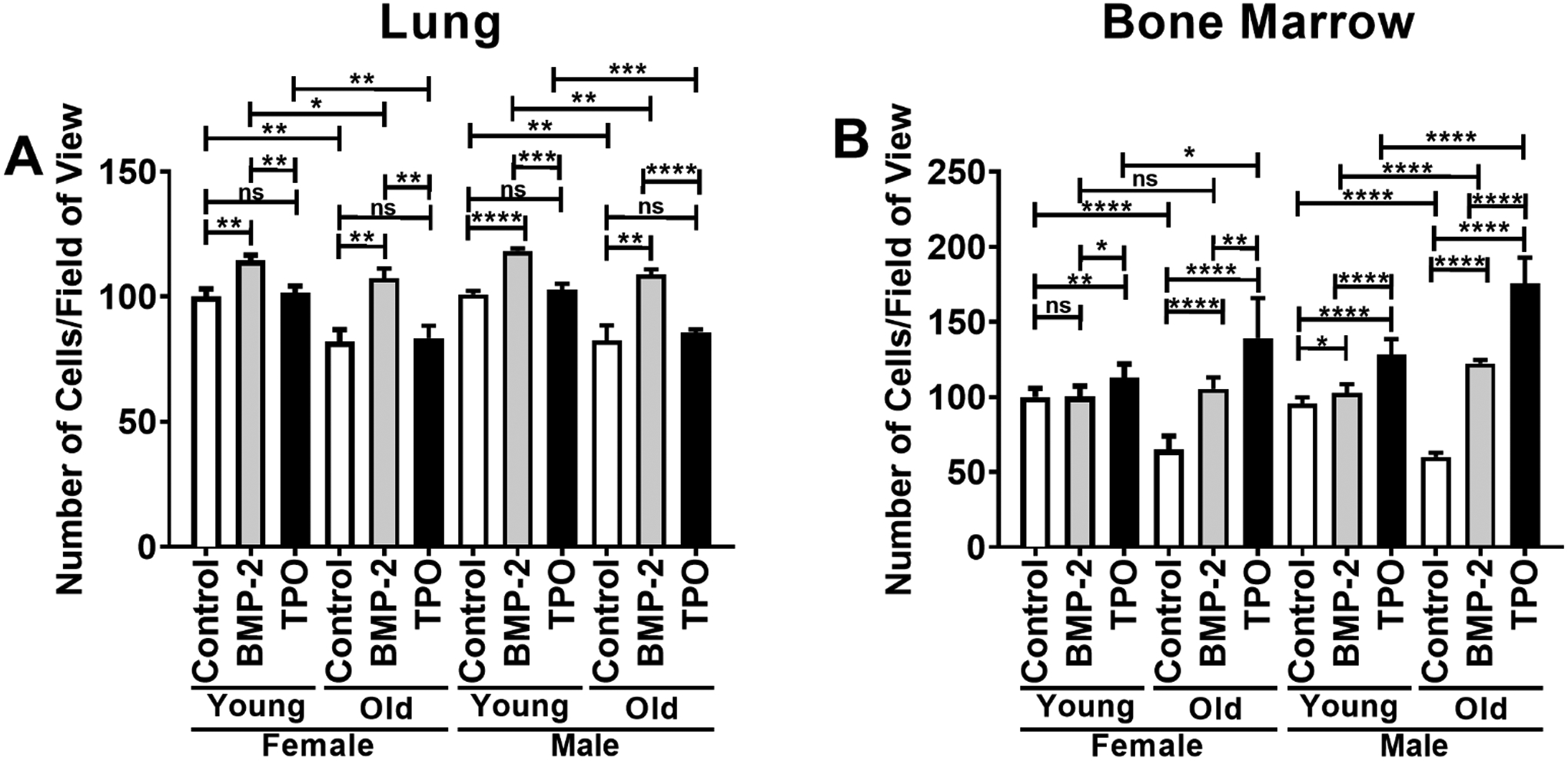

LECs and BMECs were cultured for 24 hours and the number of cells counted/field of view was used as a proxy for EC proliferation. A dosing study was completed in which male and female BMECs were treated with 0, 50, 100, or 200 ng/ml of BMP-2 or were treated with 0, 25, 50, or 100 ng/ml of TPO. The dosing study results are shown in Supplemental Figure 2. These studies showed that the highest concentration examined resulted in essentially equivalent or better changes from control than the lower concentrations studied. Thus, for the remainder of the studies, we treated cells with 200 ng/ml of BMP-2 or 100 ng/ml of TPO. These concentrations have also been used in previously published in vitro studies15,32,33. As shown in Figure 1A, for LECs, BMP-2 significantly increased cell number irrespective of age or sex from which LECs were isolated, whereas no effects were observed with TPO treatment. Additionally, irrespective of treatment or sex, cell number was significantly reduced in old as compared to young LECs. In BMECs, as illustrated in Figure 1B, trends were more variable compared to those observed in LECs. BMP-2 significantly increased cell number in young and old male BMECs as well as old female BMECs but did not impact cell number in young female BMECs. On the other hand, TPO treatment significantly increased cell number in all groups. With respect to age, for both male and female BMECs, fewer cells were present in control old BMECs as compared to control young BMECs. Treatment with BMP-2 increased BMEC numbers in old versus young cultures for male but not female BMECs, whereas treatment with TPO increased old versus young BMEC numbers for both sexes.

FIGURE 1.

Proliferation of ECs isolated from the lungs (A) or bone marrow (B) of young (3–4 mo) or old (22–24 mo) C57BL/6J mice. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n=3 biological replicates/LEC group, n=7 biological replicates/BMEC group). Young female control parameters were set to 100 and parameters in all other samples are shown relative to the young female control. An unpaired Student’s t-test was used to identify statistically significant differences. ns = not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, and ****p<0.0001.

3.3 |. Angiogenesis of ECs In Vitro

The Matrigel vessel-like structure formation assays were completed to evaluate the angiogenic potential of the ECs. The number of nodes, number of meshes, number of vessel-like structures, and total vessel path length were measured (Figure 2 A–H, Supplemental Figure 1 D, Supplemental Figure 3 A–C). A pilot vessel-like structure assay was completed to identify the optimal seeding concentration of ECs. For this pilot study, we only examined automated parameters including the number of nodes and the total vessel path length. As shown in Supplemental Figure 3 A–C, male and female BMECs were seeded at 1 × 104, 2 × 104, and 4 × 104 cells/well in a 96-well plate. These data show similar trends among all concentrations tested, and in some cases, significant differences were more readily identified in the lowest cell concentration, 1 × 104 cells/well, which was used in the remaining studies. Because N-cadherin is a well-known cell adhesion molecule whose expression can be modified by cell concentration, immunocytochemistry was used to examine N-cadherin expression in BMECs seeded at 1 × 104 and 4 × 104 cells/well. Supplemental Figure 3D shows cytoplasmic N-cadherin expression in cultures seeded at both concentrations, but aside from changes in cell number/vessel-like formation, no noticeable changes were observed.

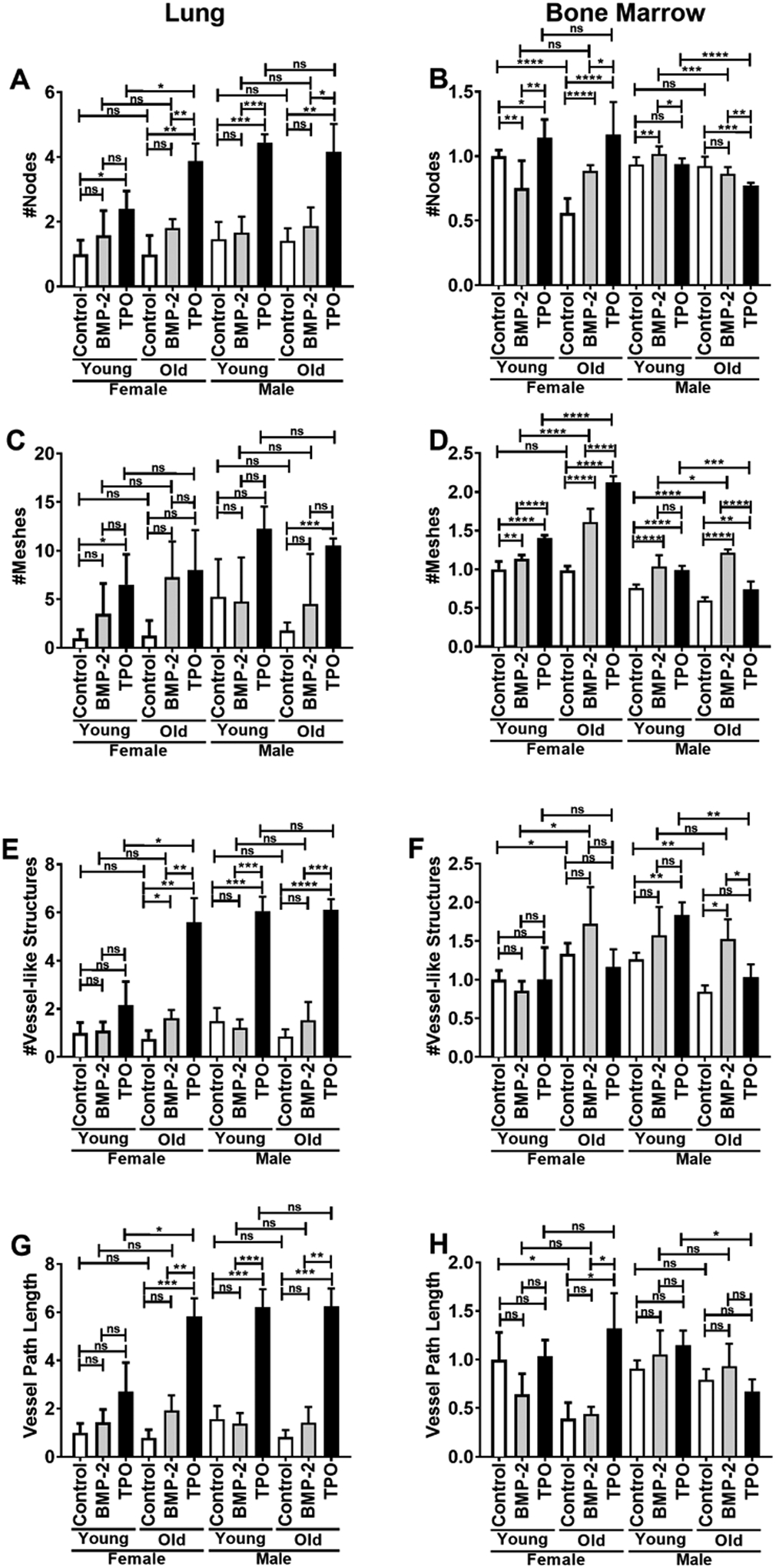

FIGURE 2.

Matrigel vessel-like structure parameters of ECs isolated from lungs (A, C, E, G) or bone marrow (B, D, F, H) of young (3–4 mo) or old (22–24 mo) C57BL/6J mice. The number of nodes (A, B), the number of meshes (C, D), the number of vessel-like structures (E, F), and the vessel path length (G, H) were quantified. Young female control parameters were set to 1.0 and parameters in all other samples are shown relative to the young female control. Data are expressed as means ± SD (n=3 biological replicates/LEC group, n=6–11 biological replicates/BMEC group). An unpaired Student’s t-test was used to identify statistically significant differences. ns = not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, and ****p<0.0001.

When determining changes in angiogenic potential, the number of nodes, number of meshes, number of vessel-like structures, and total vessel path length were considered. In females, LECs from young and old mice exhibited no difference in baseline angiogenic potential. BMP-2 treatment had no significant effect on LECs from young females, although there were non-significant trending increases observed in all of the parameters. Likewise, BMP-2 treatment of old female LECs resulted in a non-significant increase in all parameters, except a significant increase in the number of vessel-like structures. Comparatively, TPO induced an increase from baseline in the number of nodes and meshes formed by LECs from young females, but this effect was not found to be significantly different from the changes induced by BMP-2. However, in LECs from old females, TPO treatment significantly increased the number of nodes, number of vessel-like structures, and total vessel-like structure path length compared to both controls and BMP-2 treatment. The TPO-induced increases in angiogenesis were also found to be greater in the LECs from old females compared to young females, suggesting that TPO’s angiogenic effects are modulated by age in female LECs. BMP-2 treatment failed to induce any changes in LEC vessel-like formation properties in either young or old males, while TPO treatment induced significant improvements in the number of nodes, number of vessel-like structures, and total vessel-like structure path length. Notably, unlike in the female mice, TPO’s effects on angiogenesis in ECs derived from male mice did not differ based on age.

BMECs exhibited different baseline angiogenic potentials and responses to BMP-2 and TPO treatment. In females, untreated BMECs from old mice displayed a significant decrease in the number of nodes and total vessel-like structure path length, no change in the number of meshes, and an increase in the number of vessel-like structures. BMP-2 treatment in BMECs from young females decreased the number of nodes, but in old females, BMP-2 increased the number of nodes. With regard to BMP-2 treatment, in both young and old females, BMP-2 treatment significantly increased the number of meshes. No significant differences were observed in vessel-like structure number or vessel path length based on BMP-2 treatment in BMECs derived from either young or old mice. TPO treatment resulted in a significant increase in the number of nodes and meshes in young and old female BMECs. No differences in vessel-like structure were observed from TPO treatment in BMECs generated from young or old female mice. Likewise, no differences were detected in vessel path length for young female BMECs; however, a robust increase in vessel path length was observed when old female BMECs were treated with TPO.

In males, baseline BMEC angiogenic potential appeared to be slightly less in cells isolated from old mice (a reduction in the number of vessel-like structures). Both BMP-2 and TPO treatment seemed to exert variable effects BMEC node number, but both resulted in significant increases in mesh number, irrespective of age, sex, or treatment. Of note, BMP-2 treatment did not alter vessel path length in either young or old male BMECs. On the other hand, TPO increased the number of vessel-like structures and total vessel-like structure path length in BMECs from young males, but these effects were notably absent in BMECs derived from old males.

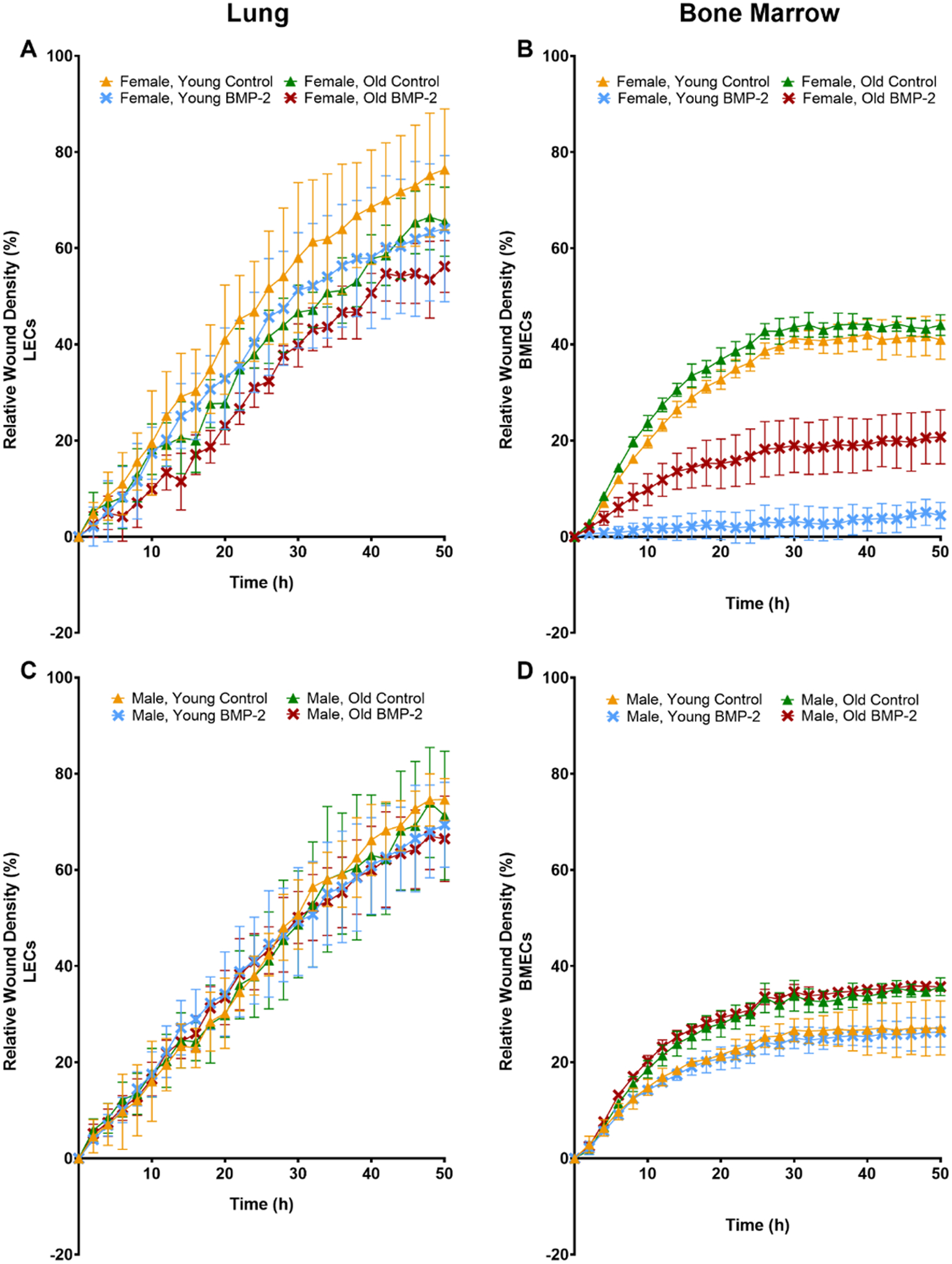

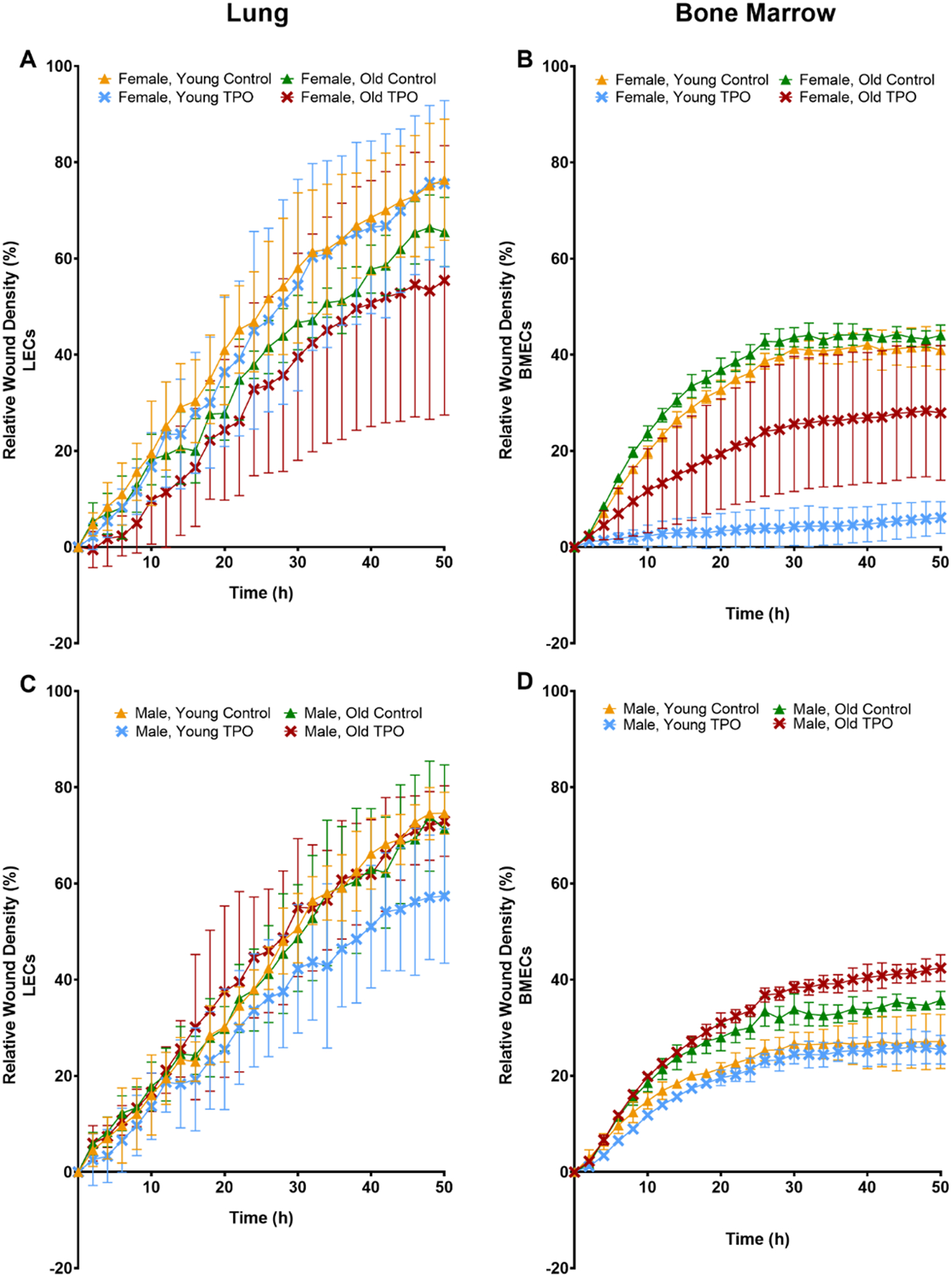

3.4 |. EC Migration

Migration was evaluated in LECs and BMECs to further examine the effects of age, sex, and TPO or BMP-2 treatment on EC function. Overall, LECs demonstrated a higher migration potential when compared to BMECs (Figure 3A vs 3B, Figure 3C vs 3D, Figure 4A vs 4B, Figure 4C vs 4D). LECs showed no differences with respect to relative wound density (Figure 3A, 3C, 4A, 4C) or wound width (Supplemental Figures 4A, 4C, 5A, 5C). ANOVA results for BMECs showed that time, age, gender, and treatment all had significant effects on migration parameters. In females, untreated BMECs from the young and old mice showed the highest migration. With old female BMECs exhibiting higher migration than young females BMECs. Both BMP-2 and TPO treatment resulted in decreased migration in both young and old female mice. In males, BMECs from old mice also showed higher migration than BMECs from young mice, but minimal differences based on treatment were observed.

FIGURE 3.

Migration (relative wound density) of ECs isolated from lungs (A, C) or bone marrow (B, D) of young (3–4 mo) or old (22–24 mo) C57BL/6J mice. ECs were isolated from female (A, B) and male (C, D) mice. Some ECs were treated with 200 ng/ml of BMP-2. The graphs represent data collected for all the groups every 2 h for 50 h. Data are expressed as means ± SD (n=3 biological replicates/group). A two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test was used to identify statistically significant differences.

FIGURE 4.

Migration (relative wound density) of ECs isolated from lungs (A, C) or bone marrow (B, D) of young (3–4 mo) or old (22–24 mo) C57BL/6J mice. ECs were isolated from female (A, B) and male (C, D) mice. Some ECs were treated with 100 ng/ml of TPO. The graphs represent data collected for all the groups every 2 h for 50 h. Data are expressed as means ± SD (n=3 biological replicates/group). A two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test was used to identify statistically significant differences.

3.5 |. Expression of Angiogenic Factors and Markers in ECs

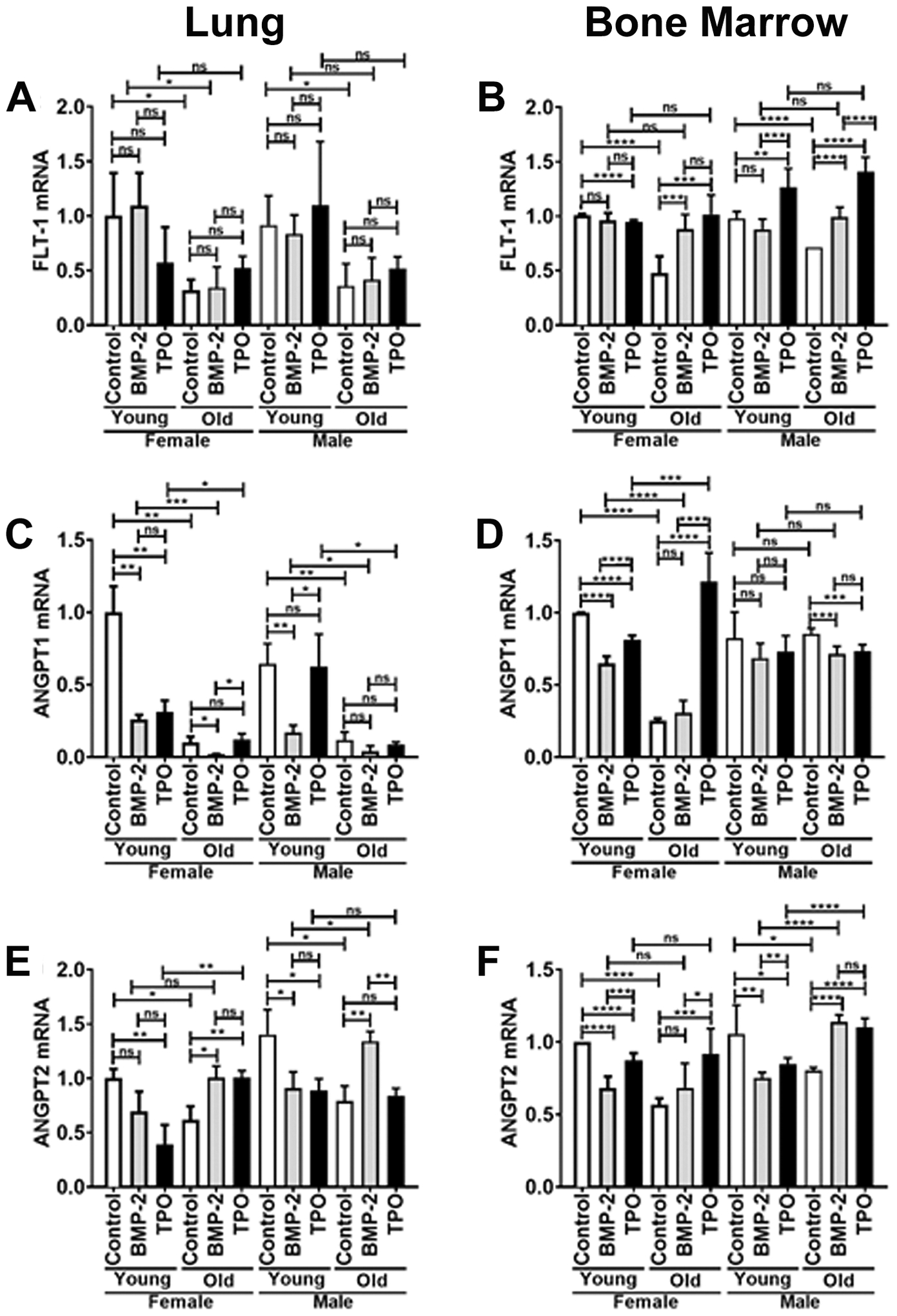

In ECs isolated from the lungs as well as the bone marrow of the tibiae and humeri, mRNA expression of FLT-1, ANGPT1, and ANGPT2 was examined (Figure 5). Within LECs, overall gene expression of FLT-1, ANGPT1, and ANGPT2 was decreased when comparing control groups of young versus old mice, in both male and female cohorts. Within BMECs, overall gene expression of FLT-1, ANGPT1, and ANGPT2 was diminished in control groups of female young versus old mice. FLT-1 and ANGPT2 expression were similarly diminished in the BMECs isolated from young versus old male mice; however, no difference was detected in ANGPT1 expression as a function of aging.

FIGURE 5.

Real-time PCR analysis of ECs isolated from lungs (A, C, E) or bone marrow (B, D, F) of young (3–4 mo) or old (22–24 mo) C57BL/6J mice. Relative mRNA expression was measured for the following genes: FLT-1 (A, B), ANGPT1 (C, D), and ANGPT2 (E, F). Young female control expression was set to 1.0 and expression in all other samples are shown relative to the young female control. Data are expressed as means ± SD (n=3 biological replicates/LEC group, n=6 biological replicates/BMEC group). An unpaired Student’s t-test was used to identify statistically significant differences. ns = not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, and ****p<0.0001.

Within LECs, control versus BMP-2 treatment resulted in no significant change in FLT-1 mRNA, irrespective of sex. There was a marked decrease in ANGPT1 mRNA expression within young female and male LECs as well as old female LECs, and a trend in old male LECs. However, there was a notable increase in ANGPT2 mRNA expression within old female and male LECs. Control versus TPO treatment similarly resulted in no significant change in FLT-1 mRNA expression of LECs isolated from old female and male mice. With regard to ANGPT1, there was no statistically significant difference in mRNA expression in old LECs derived from female or male mice treated with or without TPO. However, there was a marked reduction in ANGPT1 in young female LECs treated with TPO compared to young female controls. Interestingly, TPO treatment resulted in a decrease in ANGPT2 expression within LECs isolated from young female and male mice, but a marked increase in ANGPT2 expression was observed with TPO treatment in LECs from old female mice. However, no difference was seen in TPO-treated LECs isolated from old male mice compared to control LECs from old male mice.

In BMECs isolated from old female mice, control versus BMP-2 treatment resulted in no change in ANGPT1 or ANGPT2 expression, but a significant increase in FLT-1 expression. In BMECs isolated from old male mice, control versus BMP-2 treatment resulted in a reduction in ANGPT1 expression, but a significant increase in both FLT-1 and ANGPT2 expression. For young female BMECs, BMP-2 treatment resulted in a significant reduction in ANGPT1, and ANGPT2 expression, but no difference was observed in FLT-1 expression. For young male BMECs, BMP-2 treatment resulted in no differences in FLT-1 or ANGPT1 expression and a significant reduction in ANGPT2 expression. With respect to TPO treatment of BMECs isolated from old female mice, FLT-1, ANGPT1, and ANGPT2 expression were all significantly increased. For old male BMECs, TPO significantly increased expression of FLT-1 and ANGPT2 but decreased the expression of ANGPT1. For young female BMECs, TPO decreased the expression of FLT-1, ANGPT1, and ANGPT2. For young male BMECs, TPO did not impact the expression of ANGPT1, but it increased FLT-1 expression while decreasing ANGPT2 expression.

As SLIT/ROBO and NETRIN signaling have been reported to be involved in angiogenesis34–38, we then sought to examine the expression of these genes in young and old, male and female BMECs treated with or without BMP-2 or TPO. Several genes in these pathways had expression levels below quantitative thresholds (Ct values >35), including E-cadherin, CD41, and Matrix Gla protein (MGP); therefore, expression was compared only for genes reaching quantitative thresholds (NTN1, ROBO2, and SLIT3, see Supplemental Figure 6). In untreated cells, no differences were observed in NTN1 expression in young or old, male or female BMECs. In untreated cells, ROBO2 expression decreased with age in both male and female BMECs. On the other hand, compared to young, sex-matched BMECs, SLIT3 expression was higher in untreated, old, male BMECs, but was lower in untreated, old female BMECs.

Next, we examined the effects of BMP-2 or TPO treatment on gene expression. BMP-2 treatment increased NTN1 expression in young and old female BMECs, but reduced expression in young male BMECs, and did not alter expression in old male BMECs. TPO treatment significantly increased NTN1 expression in old female and male BMECs, but lowered expression in young female and male BMECs. Interestingly, when comparing same-sex and treatment groups, both BMP-2 and TPO treatment resulted in significant or trending increases in NTN1 expression with age. BMP-2 treatment did not impact ROBO2 expression in young female or male cells; however, BMP-2 significantly increased ROBO2 expression in old female BMECs, but significantly reduced ROBO2 expression in old male BMECs. TPO treatment did not impact ROBO2 expression in young or old female BMECs, but differentially impacted expression in male BMECs (increased ROBO2 expression in young male BMECs and decreased ROBO2 expression in old male BMECs). When comparing same-sex and treatment groups, both BMP-2 and TPO treatment resulted in a significant decrease in ROBO2 expression with age. With respect to SLIT3 expression, BMP-2 treatment significantly increased expression in young and old female BMECs. No changes in SLIT3 expression were observed with BMP-2 treatment in young male BMECs, although statistically significant, only a minor increase in SLIT3 expression was observed in old male BMECs treated with BMP-2. For TPO treatment, no significant differences in SLIT3 expression were observed in all groups except that a decrease was observed when young male BMECs were treated with TPO.

4 |. DISCUSSION

The purpose of this research is multi-faceted, including studying the effects of both sex and age on LEC and BMEC function; examining how age and sex alter the effects of BMP-2 and TPO treatment on EC function; and lastly, studying organ/tissue differences between LECs and BMECs. To accomplish this, LECs and BMECs isolated from young and old, male and female mice were treated with BMP-2 or TPO or were untreated, and studied in vitro. These cells were then examined to determine their proliferation, angiogenic potential, migration/wound closure, and gene expression. The results discussed in this section are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

TABLE 2.

Summary of LEC results.

| Outcome Measures | Results | Sex | Age | Treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Young | Old | Control | BMP-2 | TPO | |||

| Proliferation | ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ⁃⁃⁃⁃ | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Vessel-Like Structure Formation | ⁃⁃⁃⁃ | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| ⁃⁃⁃⁃ | X | X | X | X | |||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | ||||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Migration | ⁃⁃⁃⁃ | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| RT PCR | CD 31 | ▼▼ | X | X | X | ||||

| FLT-1 | ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ANGPT1 | ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | |||||

| ▼▼ | X | X | X | ||||||

| ▼▼ | X | X | X | ||||||

| ANGPT2 | ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | X | |||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | ||||||

For the results column, down arrow=decrease, up arrow=increase, and the dashes=no change. An “X” in the sex, age, or treatment columns indicate changes in the outcome measure. For example, the first row demonstrates that proliferation was decreased in both male and female, old control LECs, when compared to respective male or female, young LECs.

TABLE 3.

Summary of BMEC results.

| Outcome Measures | Results | Sex | Age | Treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Young | Old | Control | BMP-2 | TPO | |||

| Proliferation | ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | X | |||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | ||||||

| Vessel-Like Structure Formation | ▼▼ | X | X | X | |||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | ||||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | X | |||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | ||||||

| Migration | ▲▲ | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| RT PCR | CD 31 | ▲▲ | X | X | X | ||||

| ▼▼ | X | X | X | ||||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | ||||||

| ▼▼ | X | X | X | ||||||

| FLT-1 | ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | ||||||

| ANGPT1 | ▼▼ | X | X | X | |||||

| ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | |||||

| ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | |||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | ||||||

| ANGPT2 | ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | |||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | ||||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | X | |||||

| NTN1 | ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | X | |||||

| ▼▼ | X | X | X | ||||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | X | |||||

| ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | |||||

| ROBO2 | ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | ||||||

| ▼▼ | X | X | X | X | |||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | ||||||

| SLIT3 | ▲▲ | X | X | X | |||||

| ▲▲ | X | X | X | X | |||||

| ▼▼ | X | X | X | ||||||

For the results column, down arrow=decrease, up arrow=increase. An “X” in the sex, age, or treatment columns indicate changes in the outcome measure. For example, the first row demonstrates that proliferation was decreased in both male and female, old, control BMECs, when compared to respective male and female, young BMECs. Similarly shaded rows indicate the same observed pattern of marked (“X”) groups in which the outcome measure was significantly changed.

Several studies have implicated the role of the BMP signaling pathway in EC proliferation16,39–41. Specifically, BMP-2, BMP-4, and BMP-6 are known to increase EC proliferation. On the other hand, numerous studies have shown that aging-induced EC senescence leads to various impairments in EC function39–41. One study reported that knockout of Sirtuin 6 (Sirt6), a regulator of EC senescence, resulted in decreased proliferation and the ability to form vessel-like structures in Matrigel42. Consistent with these observations, age significantly reduced both lung and bone marrow derived EC proliferation. Notably, in LECs, BMP-2 consistently improved proliferation, irrespective of age or sex, whereas TPO did not alter LEC proliferation. On the other hand, for BMECs, BMP-2 and TPO both increased the proliferation of old female BMECs, but only TPO increased proliferation in young female BMECs, whereas both BMP-2 and TPO increased the proliferation of both young and old male BMECs (compared to age- and sex- matched untreated BMECs). These observations revealed the complex changes that sex, age, tissue type, and drug treatment can have on EC proliferation.

ECs and successful angiogenesis are crucial for the bone repair process8,43. Therefore, we measured angiogenic potential based on the ability of the ECs to form vessel-like structures in a Matrigel assay. Importantly, ECs seeded at multiple concentrations showed similar results in terms of the number of nodes and the vessel path length, suggesting the confluence appears to have limited impact with regard to TPO and BMP-2 treatment, sex, or age (Supplemental Figure 3A–C).

In our study, aging and BMP-2 treatment did not appear to influence angiogenic potential of LECs regardless of sex. In BMECs, there was an apparent increase in vessel-like structure formation in female BMECs, but a robust decrease in male BMECs with age. BMP-2 treatment in old male BMECs returned vessel-like structure formation to levels observed with young male BMECs with or without BMP-2 treatment. BMP-2 has been well-characterized as a promoter of EC vessel formation in settings of postnatal neovascularization, tissue repair, and tissue-associated angiogenesis16–20. A speculative explanation for why BMP-2 treatment had minimal effects on LEC angiogenesis may be due to higher expression of matrix Gla protein (MGP), which is found in higher amounts in lungs and kidneys and is known to have an inhibitory effect on BMP-2 associated angiogenesis44.

Comparatively, TPO increased angiogenesis in both male and female LECs. TPO’s effect appeared to be greater in old female LECs, old male LECs, and young male LECs. In BMECs, TPO’s positive effects on angiogenesis were seen in BMECs derived from young male mice. Further investigation of how these effects are mediated is warranted; one possible explanation may be age- or sex-related differences in EC expression of the TPO receptor c-mpl or signaling proteins involved in the PAF-signaling cascade. Overall, these findings indicate that both the source of the ECs and the sex of the cells influence the phenotypic changes induced by aging, BMP-2, and TPO.

We further evaluated migration in lung and bone marrow derived ECs to determine the effects of age, sex, and BMP-2 or TPO treatment on wound healing potential. While no significant differences were observed in LEC cultures, several interesting differences were observed in BMEC cultures. With regard to age, one interesting trend was that irrespective of sex, migration was greatest for BMECs derived from old mice as compared to young mice (untreated cells). As proliferation was reduced in old ECs, these data may suggest that migration is improved at the expense of proliferation. With reference to sex-based differences, another trend observed was that migration was greater for untreated BMECs derived from female mice as compared to male mice of the same age (note Y-axis in Figure 3B vs 3D and 4B vs 4D). Our findings of sex-based differences in ECs are consistent with other studies. For example, one study reported that identically isolated ECs from male and female mice expressed significant phenotypic heterogeneity in vitro, despite identical culture conditions and levels of reproductive hormones45. Moreover, Zhang et al.46 showed that female ECs displayed greater migration and angiogenesis in normoxic conditions compared to male counterparts. Furthermore, female ECs treated with either BMP-2 or TPO resulted in impaired migration. This was not the case for treated male ECs. Thus, it appears that while migration is improved in aged BMECs, treatment with either BMP-2 or TPO inhibits migration in old female BMECs. As EC migration is important in successful fracture repair processes, these data may suggest that use of BMP-2 or TPO for fracture treatment would allow for better results in old males compared to old females. Future studies that investigate the impacts of treatment, age, and/or sex on directional migration (via cytokine-driven chemotaxis) using transwell assays would be needed to further elucidate these mechanisms.

The expression of several angiogenesis-related genes was also examined. FLT-1 is one of two tyrosine kinase receptors of VEGF that plays a critical role in the promotion of angiogenesis and vasculogenesis53–55. Our data indicate a decrease in FLT-1 expression in LECs and BMECs of old mice. Supplementation of TPO resulted in an increase in FLT-1 expression in old BMECs, which is consistent with previous literature on the positive effects of TPO on VEGF signaling56.

ANGPT1 and ANGPT2 are members of the angiopoietin family of growth factors. ANGPT1 functions as an agonist to the tyrosine kinase receptors, Tie-2 and Tek. ANGPT1 functions in vasculogenesis and EC migration57–59. The expression of ANGPT1 was diminished in male and female LECs and female BMECs derived from old mice compared to their young counterparts. TPO treatment in BMECs resulted in an increased expression of ANGPT1 in old female mice.

The relationship between ANGPT2 and ECs is contextual. Indeed, within the circulatory system, ANGPT2 functions as an antagonist to ANGPT1 mediated Tie-2 expression. Whereas, within the lymphatic system, ANGPT2 functions as an agonist to Tie-2 expression60,61. Here, ANGPT2 expression was reduced in both lung and bone marrow derived ECs from old versus young mice. This appears to contradict the findings of Hohensinner et al.62, where they observed increased ANGPT1 and decreased ANGPT2 in old ECs compared to their young counterparts. However, with TPO-treatment, a significant increase in ANGPT2 expression was observed in old female LECs and old female and male BMECs. Therefore, our studies support the idea that ANGPT2 expression in ECs varies based on factors associated with tissue-specific microenvironments.

To further extend the mechanisms by which TPO and BMP-2 treatment, sex, and aging impact genes known to be involved with angiogenesis, we examined some axon guidance signals, including SLIT/ROBO and NTN, which have recently been found to be involved in angiogenesis34–38. However, these signaling molecules have not been examined in BMECs, and their expression levels have not been compared between young and old mice. We measured the mRNA levels of those genes and examined their mRNA expression levels in ECs associated with aging. Our data demonstrate that NTN1 and ROBO2 expression decreased with age in both male and female control BMECs, whereas SLIT3 expression increased with age in male BMECs, suggesting that NTN1, ROBO2, and SLIT3 may all be associated with aging. NTN1 expression was upregulated by BMP-2 treatment in young and old female BMECs, and NTN1 expression was upregulated by TPO treatment in male and female old BMECs. Overall, these in vitro data suggest the potential role of NTN and SLIT/ROBO signaling in angiogenesis in skeletal tissues associated with aging and treatment with BMP-2 and TPO.

Therefore, to better understand the possible biological impacts of these genes on EC function, we examined patterns between functional outcomes and mRNA expression (Table 3). One observed trend (gray highlighted lines) is that untreated, old male and female BMECs have increased migration at the expense of decreased proliferation. Notably, FLT-1, ANGPT2, NTN1, and ROBO2 mRNA expression are also decreased in these cells, suggesting that these genes may regulate proliferation and inhibit migration. Another observed trend (blue highlighted lines) is that vessel-like structure formation decreases in untreated, old male BMEC cultures, while both CD31 and SLIT3 mRNA expression increase. On the other hand, as highlighted in orange, vessel-like structure formation increases in untreated, old female BMEC cultures, whereas both CD31 and ANGPT1 mRNA expression decreases. These observations suggest that in old BMECs, regulation of vessel-like structure formation may be sex-dependent, as evidenced by the inverse correlation of SLIT3 and ANGPT1 expression with vessel-like structure formation in males and females, respectively. Finally, vessel-like structure formation increased in TPO treated, young male BMECs which corresponded with an increase in FLT-1 and ROBO2, but decreased with SLIT3 mRNA expression, suggesting these genes may play an important role in this process.

Next, we sought to examine the role of EC-cell junctions to investigate whether they contributed to the observed effects on ECs produced by TPO and BMP-2 treatment, sex, and aging. EC-cell junctions have become more well-known as important and dynamic regulators of angiogenesis, playing key roles in steps such as sprouting, anastomosis, lumen formation, remodeling, and maintenance.63 In the present study, we attempted to measure the mRNA levels of E-cadherin and CD41 to assess the level of true EC-cell junction formation. However, in all treatment groups, these genes were not detected in our analyses. We further tested higher cell concentrations and observed that N-cadherin expression via immunocytochemistry remained unchanged in treated or untreated, young or old, male BMECs (Supplementary Figure 3D). These data suggest that junctions were indeed formed irrespective of cell concentration. In general, the molecular mechanisms that govern the exact role of EC-cell junctions throughout the various stages of angiogenesis is a growing field of research and requires more sophisticated methods that are beyond the scope of the present study.

In conclusion, our study contributes to the collective body of literature demonstrating that the source and sex from which ECs are derived have important effects on EC function and responses to changes such as aging and drug treatment. Taken together, these data demonstrate the importance of understanding vascular changes in the elderly in order to optimize treatments that can promote better vascular functioning during fracture healing. Despite in vitro studies being limited in their ability to perfectly predict what occurs in vivo, these data showcase an important method of testing drugs that can improve EC function. In vitro testing may provide opportunities to predict which drugs will be most successful in certain groups of people, such as male versus female and the young versus elderly, thus contributing to the development of more optimized treatment algorithms based on patients’ physical and medical conditions. This will only become more important as the world population continues to age, and the burden of bone fractures continues to increase.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the Indiana University Angiogenesis Core for assisting with wound migration studies. This project was supported, in part, by the Cooperative Center of Excellence in Hematology (CCEH) Award, funded in part by NIH 1U54DK106846 (MAK, SS), NIH T32 DK007519 (UCD), NIH T32 HL007910 (ODA) NIH R01 AG060621 (MAK, JL, ODA), and National Science Foundation Grant No. 1618-408 (ODA). In addition, the results of this work were supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN: VA Merit #BX003751 (MAK). This work was also supported by an Indiana University Collaborative Research Grant (MAK, JL).

Nonstandard Abbreviations:

- ANGPT1

angiopoietin 1

- ANGPT2

angiopoietin 2

- BMEC

bone marrow endothelial cell

- BMP-2

bone morphogenetic protein 2

- CD31

cluster of differentiation 31

- EC

endothelial cell

- EPC

endothelial progenitor cell

- FLT-1

fms related tyrosine kinase

- LEC

lung endothelial cell

- NTN

Netrin

- PAF

platelet activating factor

- ROBO

roundabout guidance receptor

- SLIT

slit guidance ligand

- TPO

thrombopoietin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policy of any of the aforementioned agencies.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

Dr. Kacena is a co-inventor on a patent for the use of thrombopoietic agents in bone healing. All other authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gruber R, Koch H, Doll BA, Tegtmeier F, Einhorn TA, Hollinger JO. Fracture healing in the elderly patient. Experimental gerontology. 2006;41(11):1080–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blyth FM, Cumming R, Mitchell P, Wang JJ. Pain and falls in older people. European journal of pain (London, England). 2007;11(5):564–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim DH, Vaccaro AR. Osteoporotic compression fractures of the spine; current options and considerations for treatment. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2006;6(5):479–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huntjens KMB, Kosar S, van Geel TACM, et al. Risk of subsequent fracture and mortality within 5 years after a non-vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(12):2075–2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lau E, Ong K, Kurtz S, Schmier J, Edidin A. Mortality following the diagnosis of a vertebral compression fracture in the Medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(7):1479–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foulke BA, Kendal AR, Murray DW, Pandit H. Fracture healing in the elderly: A review. Maturitas. 2016;92:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bahney CS, Zondervan RL, Allison P, et al. Cellular biology of fracture healing. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2019;37(1):35–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hankenson KD, Dishowitz M, Gray C, Schenker M. Angiogenesis in bone regeneration. Injury. 2011;42(6):556–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grosso A, Burger MG, Lunger A, Schaefer DJ, Banfi A, Di Maggio N. It Takes Two to Tango: Coupling of Angiogenesis and Osteogenesis for Bone Regeneration. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2017;5:68–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ugarte F, Forsberg EC. Haematopoietic stem cell niches: new insights inspire new questions. EMBO J. 2013;32(19):2535–2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner DR, Karnik S, Gunderson ZJ, et al. Dysfunctional stem and progenitor cells impair fracture healing with age. World J Stem Cells. 2019;11(6):281–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu C, Hansen E, Sapozhnikova A, Hu D, Miclau T, Marcucio RS. Effect of age on vascularization during fracture repair. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 2008;26(10):1384–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandrasekhar KS, Zhou H, Zeng P, et al. Blood vessel wall-derived endothelial colony-forming cells enhance fracture repair and bone regeneration. Calcified tissue international. 2011;89(5):347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao L, Wang J, Hou J, Xing W, Liu C. Vascularization and bone regeneration in a critical sized defect using 2-N,6-O-sulfated chitosan nanoparticles incorporating BMP-2. Biomaterials. 2014;35(2):684–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearson HB, Mason DE, Kegelman CD, et al. Effects of Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 on Neovascularization during Large Bone Defect Regeneration. Tissue Engineering - Part A. 2019;25(23–24):1623–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langenfeld EM, Langenfeld J. Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 stimulates angiogenesis in developing tumors. Molecular Cancer Research. 2004;2(3):141–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finkenzeller G, Hager S, Stark GB. Effects of bone morphogenetic protein 2 on human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Microvascular Research. 2012;84(1):81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dyer LA, Pi X, Patterson C. The role of BMPs in endothelial cell function and dysfunction. In. Vol 25: Elsevier Inc.; 2014:472–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.García de Vinuesa A, Abdelilah-Seyfried S, Knaus P, Zwijsen A, Bailly S. BMP signaling in vascular biology and dysfunction. In. Vol 27: Elsevier Ltd; 2016:65–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen WC, Chung CH, Lu YC, et al. BMP-2 induces angiogenesis by provoking integrin α6 expression in human endothelial progenitor cells. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2018;150:256–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.James AW, LaChaud G, Shen J, et al. A Review of the Clinical Side Effects of Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews. 2016;22(4):284–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kacena MAZ, IN, US), Chu T-mGC, IN, US), Inventors; Osteofuse, Inc. (Zionsville, IN, US: ), assignee. Use of Compounds with Thrombopoietic Activity to Promote Bone Growth and Healing. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brizzi MF, Battaglia E, Montrucchio G, et al. Thrombopoietin stimulates endothelial cell motility and neoangiogenesis by a platelet-activating factor-dependent mechanism. Circulation research. 1999;84(7):785–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sieveking DP, Lim P, Chow RWY, et al. A sex-specific role for androgens in angiogenesis. J Exp Med. 2010;207(2):345–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodges NA, Suarez-Martinez AD, Murfee WL. Understanding angiogenesis during aging: opportunities for discoveries and new models. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md : 1985). 2018;125(6):1843–1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moriya J, Minamino T. Angiogenesis, Cancer, and Vascular Aging. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2017;4:65–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mulcrone PL, Campbell JP, Clément-Demange L, et al. Skeletal Colonization by Breast Cancer Cells Is Stimulated by an Osteoblast and β2AR-Dependent Neo-Angiogenic Switch. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2017;32(7):1442–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Niu N, Xu S, Jin ZG. A simple protocol for isolating mouse lung endothelial cells. Scientific reports. 2019;9(1):1458–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rueden CT, Schindelin J, Hiner MC, et al. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2017;18(1):529–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longair MH, Baker DA, Armstrong JD. Simple Neurite Tracer: open source software for reconstruction, visualization and analysis of neuronal processes. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(17):2453–2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meijome TE, Baughman JT, Hooker RA, et al. C-Mpl Is Expressed on Osteoblasts and Osteoclasts and Is Important in Regulating Skeletal Homeostasis. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2016;117(4):959–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bethel M, Barnes CLT, Taylor AF, et al. A novel role for thrombopoietin in regulating osteoclast development in humans and mice. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230(9):2142–2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suchting S, Freitas C, le Noble F, et al. The Notch ligand Delta-like 4 negatively regulates endothelial tip cell formation and vessel branching. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(9):3225–3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tammela T, Zarkada G Fau -Wallgard E, Wallgard E Fau -Murtomäki A, et al. Blocking VEGFR-3 suppresses angiogenic sprouting and vascular network formation. (1476–4687 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Larrivée B, Prahst C, Gordon E, et al. ALK1 signaling inhibits angiogenesis by cooperating with the Notch pathway. Dev Cell. 2012;22(3):489–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu M-F, Liao C-Y, Wang L-Y, Chang JT. The role of Slit-Robo signaling in the regulation of tissue barriers. Tissue Barriers. 2017;5(2):e1331155–e1331155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bardin N, Murthi P, Alfaidy N. Normal and pathological placental angiogenesis. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:354359–354359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tian X-L, Li Y. Endothelial Cell Senescence and Age-Related Vascular Diseases. Journal of Genetics and Genomics. 2014;41(9):485–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bochenek ML, Schütz E, Schäfer K. Endothelial cell senescence and thrombosis: Ageing clots. Thrombosis Research. 2016;147(1879–2472 (Electronic)):36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hebb JH, Ashley JW, McDaniel L, et al. Bone healing in an aged murine fracture model is characterized by sustained callus inflammation and decreased cell proliferation. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2018;36(1):149–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cardus A, Uryga AK, Walters G, Erusalimsky JD. SIRT6 protects human endothelial cells from DNA damage, telomere dysfunction, and senescence. Cardiovascular Research. 2012;97(3):571–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carulli C, Innocenti M, Brandi ML. Bone vascularization in normal and disease conditions. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2013;4:106–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yao Y, Watson Andrew D, Ji S, Boström Kristina I. Heat Shock Protein 70 Enhances Vascular Bone Morphogenetic Protein-4 Signaling by Binding Matrix Gla Protein. Circulation Research. 2009;105(6):575–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huxley VH, Kemp SS, Schramm C, et al. Sex differences influencing micro- and macrovascular endothelial phenotype in vitro. The Journal of physiology. 2018;596(17):3929–3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y, Dong X, Shirazi J, Gleghorn JP, Lingappan K. Pulmonary endothelial cells exhibit sexual dimorphism in their response to hyperoxia. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2018;315(5):H1287–H1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang S, Graham J, Kahn JW, Schwartz EA, Gerritsen ME. Functional roles for PECAM-1 (CD31) and VE-cadherin (CD144) in tube assembly and lumen formation in three-dimensional collagen gels. Am J Pathol. 1999;155(3):887–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cao G, Fehrenbach ML, Williams JT, Finklestein JM, Zhu J-X, Delisser HM. Angiogenesis in platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1-null mice. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(2):903–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newman PJ. The biology of PECAM-1. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;99(1):3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DeLisser HM, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Strieter RM, et al. Involvement of endothelial PECAM-1/CD31 in angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151(3):671–677. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsumura T, Wolff K, Petzelbauer P. Endothelial cell tube formation depends on cadherin 5 and CD31 interactions with filamentous actin. The Journal of Immunology. 1997;158(7):3408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee JH, Bhang DH, Beede A, et al. Lung stem cell differentiation in mice directed by endothelial cells via a BMP4-NFATc1-thrombospondin-1 axis. Cell. 2014;156(3):440–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nesmith JE, Chappell JC, Cluceru JG, Bautch VL. Blood vessel anastomosis is spatially regulated by Flt1 during angiogenesis. Development. 2017;144(5):889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ho VC, Fong G-H. Vasculogenesis and Angiogenesis in VEGF Receptor-1 Deficient Mice. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ). 2015;1332:161–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shibuya M. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (VEGFR-1/Flt-1): a dual regulator for angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2006;9(4):225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kirito K, Fox N, Komatsu N, Kaushansky K. Thrombopoietin enhances expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in primitive hematopoietic cells through induction of HIF-1alpha. Blood. 2005;105(11):4258–4263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koblizek TI, Weiss C Fau -Yancopoulos GD, Yancopoulos Gd Fau -Deutsch U, Deutsch U Fau -Risau W, Risau W. Angiopoietin-1 induces sprouting angiogenesis in vitro. Current Biology. 1998;8(0960–9822 (Print)):529–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fagiani E, Christofori G. Angiopoietins in angiogenesis. Cancer Letters. 2013;328(1):18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jeansson M, Gawlik A, Anderson G, et al. Angiopoietin-1 is essential in mouse vasculature during development and in response to injury. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121(6):2278–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Souma T, Thomson BR, Heinen S, et al. Context-dependent functions of angiopoietin 2 are determined by the endothelial phosphatase VEPTP. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2018;115(6):1298–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hegen A, Koidl S, Weindel K, Marmé D, Augustin Hellmut G, Fiedler U. Expression of Angiopoietin-2 in Endothelial Cells Is Controlled by Positive and Negative Regulatory Promoter Elements. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2004;24(10):1803–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hohensinner PJ, Ebenbauer B, Kaun C, Maurer G, Huber K, Wojta J. Reduced Ang2 expression in aging endothelial cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2016;474(3):447–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Szymborska A, Gerhardt H. Hold Me, but Not Too Tight-Endothelial Cell-Cell Junctions in Angiogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10(8):a029223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.