Abstract

Background and aims

To evaluate the prevalence and prognostic value of metabolic syndrome (MetS) in patients admitted for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Methods and results

In this monocentric cohort retrospective study, we consecutively included all adult patients admitted to COVID-19 units between April 9 and May 29, 2020 and between February 1 and March 26, 2021. MetS was defined when at least three of the following components were met: android obesity, high HbA1c, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and low HDL cholesterol. COVID-19 deterioration was defined as the need for nasal oxygen flow ≥6 L/min within 28 days after admission.

We included 155 patients (55.5% men, mean age 61.7 years old, mean body mass index 29.8 kg/m2). Fifty-six patients (36.1%) had COVID-19 deterioration. MetS was present in 126 patients (81.3%) and was associated with COVID-19 deterioration (no-MetS vs MetS: 13.7% and 41.2%, respectively, p < 0.01). Logistic regression taking into account MetS, age, gender, ethnicity, period of inclusion, and Charlson Index showed that COVID-19 deterioration was 5.3 times more likely in MetS patients (95% confidence interval 1.3–20.2) than no-MetS patients.

Conclusions

Over 81.3% of patients hospitalized in COVID-19 units had MetS. This syndrome appears to be an independent risk factor of COVID-19 deterioration.

Keywords: COVID-19 deterioration, Metabolic syndrome, Prevalence, Prognosis

Abbreviations: BMI, Body mass index; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; CRP, C-reactive protein; ICU, Intensive care unit; MetS, Metabolic syndrome; MetSFPG, Metabolic syndrome defined according to fasting glycemia instead of HbA1c; PCR, Polymerase chain reaction

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) first appeared as a contagious respiratory viral emerging pathology in Hubei region in December 2019. In the subsequent three months, it grew into a pandemic and has not been stopped yet even after a global vaccine policy. By July 2021, more than 181 million people had been infected, with over 3.9 million deaths [1]. Severe forms of COVID-19 occur in 15% of patients [2]. Many risk factors of severe infection have been identified including male gender [3], advanced age [4], and cardiovascular risk factors [5] such as hyperglycemia [5], hypertension [6], and lipid disorders [7]. Furthermore, obesity seems to be predictive of COVID-19 deterioration; patients with grade 2 obesity are seven times more likely to be admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) than patients with lean body weight [8]. In one study, the prevalence of mechanical ventilation in ICU was 81% for patients with obesity compared with 41% for patients with lean body weight [9].

There are different phenotypes of obesity. Android obesity might be a key prognostic factor of severe COVID-19 through inflammatory mechanisms [10].

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is defined by the coexistence of between 3 and 5 of the following components: android obesity, high glucose level, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and low levels of HDL cholesterol [11]. In this context, we hypothesized that MetS diagnosis (as per this Definition but using HbA1c to define hyperglycemia) is associated with deterioration of patients admitted to non-ICUs with COVID-19, and that the higher the number of components, the more frequent the deterioration of COVID-19 infection. The poor prognosis of metabolic syndrome, defined by obesity instead of high waist circumference and diabetes instead of fasting hyperglycemia, was recently described [12,13]. The aim of our study was to evaluate in patients admitted to four COVID-19 hospital departments (excluding ICU), (i) the prevalence of MetS and (ii) whether MetS is associated with COVID-19 deterioration.

Methods

Study design, setting, and participants

We conducted a retrospective observational study in Avicenne Hospital, Bobigny, France. All consecutive patients admitted between April 9 and May 29, 2020 and between February 1 and March 26, 2021, and in one of the hospital's, four in-patient's departments receiving COVID-19-infected patients directly from the emergency room were included. COVID-19 was confirmed by nasal polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Non-inclusion criteria were (i) pregnancy and (ii) ineligibility to be subsequently transferred to an ICU in case of disease deterioration.

In Avicenne hospital, all patients (COVID or not) are informed at admission that their medical records could be used for research unless they indicate their opposition. For the present study, no patient indicated any opposition. Approval for the use of patient data was provided by the local ethics committee (approval number: CLEA-2020-121). Data were analyzed anonymously.

Data collection

Data were extracted from patients’ medical files and collected in a secure health database. General data included routinely prescribed treatments, health insurance coverage, and ethnicity.

Medical history data including diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia were self-reported or inferred from blood glucose, blood pressure, or lipid-lowering agents, respectively. Cancer, chronic bronchopneumopathy, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, sleep apnea and non alcoholic steatosis hepatitiswere self-reported or recorded from patients’ medical files. Additionally, we collected data for any comorbid conditions to calculate the Charlson Index [14]. Obesity was defined by body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2. Weight and height were measured within 24 h following emergency unit admission.

Chest computed tomography scan data included the extent of typical COVID-19 lesions was classified into two groups: minimal to moderate (<25%) and extended to critical (≥25%). Treatment received during hospitalization was collected.

Biomarkers data included (i) metabolic biomarkers as fasting plasma glucose, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and HbA1c and (ii) inflammation biomarkers as C-reactive protein (CRP) and fibrinogen. All these biomarkers were routinely measured on plasma from fasting individuals. A Cobas 6000 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics) was used for all biomarkers except fibrinogen (chronometry—Dade Thrombin), where a Siemens analyzer was used. SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR was performed on nasopharyngeal samples collected in virus transport medium, using the SARS-CoV-2 Amp Kit on the automated device Alinity that strictly following the recommendations from the manufacturer.

Metabolic syndrome

We adapted the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP)–Adult Treatment Panel III (ATPIII) to define MetS [11]. Because fasting glycemia values can be higher during infection, we decided to define MetS replacing the component ‘fasting glycemia ≥6 mmol/L’ with ‘HbA1c ≥ 5.7%’ which reflects hyperglycemia independently of stress. More specifically, patients meeting at least three of the following five MetS components [11] were categorized as having the syndrome: (i) android obesity (i.e., waist circumference measured with a plastic anthropometric tape placed at half distance between the coastal edge and the iliac crest, in the standing position, exceeding 88 cm for women and 102 cm for men), (ii) HbA1c ≥ 5.7% or pharmacologic treatment or already diagnosed diabetes, (iii) medical history of hypertension or evidence of a repeated measurements of high blood pressures leading to the introduction of antihypertensive medication during hospitalization, (iv) triglycerides level ≥1.6 mmol/L or fibrate usual medication, and (v) HDL cholesterol level <1 mmol/L in males or < 1.6 mmol/L in females or routine prescribed fibrate medication. We tallied the number of MetS components in patients for whom the status for all five components was known.

We made a sensitivity analysis defining metabolic syndrome using fasting hyperglycemia instead of Hb1ac: MetSFPG (hereafter called).

Definition of COVID-19 deterioration and associated standard of care

COVID-19 deterioration was defined as the need for nasal oxygen flow at or above 6 L/m during hospitalization within 28 days after admission. We also considered the non-invasive ventilation requirement as a secondary outcome.

International standards of care were followed according to a local guideline which was updated as necessary on a daily basis.

Statistical analyses

For power calculation, we estimated that 40% of the inpatients in the hospital's four COVID-19 departments (i.e., excluding the emergency unit and ICU) would be diagnosed with MetS. We presumed that 30% of the MetS group would have COVID-19 deterioration vs 10% of the no-MetS group. Accordingly, we calculated that a minimum study population of 120 patients would be needed to show a significant difference in the rate of COVID-19 deterioration between the two groups (alpha risk of 5% and power of 80%).

Baseline continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies (percentages). Missing data were not replaced. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare continuous variables, while Pearson's chi-squared (X 2) test or Fisher's exact test was used (depending on the number of patients within each group) for categorical variables. The correlation between the number of MetS components and COVID-19 deterioration was assessed by the exact Cochran–Armitage test for trend.

The associations between MetS and COVID-19 deterioration (model 1) and between MetSFPG (sensitivity analysis) and COVID-19 deterioration (model 2) were computed using logistic regression, taking into account the following variables: age, gender, ethnicity, period of inclusion, and Charlson Index. All tests were two-sided and used a significance level p-value of 0.05. Analyses were conducted with SAS 9.4 software.

Results

Study population characteristics

A total of 223 patients were admitted to the four hospital units after being transferred from the emergency department. Twenty-two of these were excluded because they were not eligible to be subsequently transferred to ICU in case of deterioration. A further 17 were excluded because any positive COVID-19 PCR was available. Finally, we could not characterize a possible MetS for 29 patients. This was because, all patients combined, we did not have enough information for all MetS components. More specifically, a patient could not be classified (i.e., MetS or no-MetS) if she/he did not have data for at least three components. Therefore, 155 patients (i.e., the study population) were included (flowchart in Additional Figure 1).

Table 1 shows the general and medical characteristics of the study population. Additional Table 1 shows patients’ main clinical, biological, and radiological characteristics. A total of 56 patients (36.1%) experienced COVID-19 deterioration, 25 patients (16.1%) needed non-invasive ventilation, and 22 patients (14.1%) were subsequently transferred to ICU. Mean hospitalization stay was 10.2 ± 6.5 days. Nine patients (5.8%) died.

Table 1.

Population characteristics.

| Avalaible data | Total | No COVID-19 deterioration n = 99 |

COVID-19 deterioration n = 56 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | n = 155 | 61.7 ± 14.8 | 58.9 ± 13.9 | 66.6 ± 15.1 | <0.01 |

| Male gender | n = 155 | 86 (55.5) | 50 (50.5) | 36 (64.3) | 0.10 |

| Ethnicity | n = 149 | 0.13 | |||

| Caucasian | 46 (30.9) | 30 (30.9) | 16 (30.8) | ||

| Arabic | 57 (38.3) | 32 (33.0) | 25 (48.1) | ||

| Afro-Caribbean | 26 (17.4) | 18 (18.6) | 8 (15.4) | ||

| Asian | 20 (13.4) | 17 (17.5) | 3 (5.8) | ||

| Socioeconomic data | n = 146 | 0.30 | |||

| Health insurance coverage | 142 (97.3) | 90 (95.7) | 52 (100.0) | ||

| No health insurance coverage | 4 (2.7) | 4 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Current smoker | n = 148 | 3 (2.0) | 3 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.55 |

| Medical history | |||||

| Cancer | n = 155 | 16 (10.3) | 9 (9.1) | 7 (12.5) | 0.50 |

| HIV infection | n = 154 | 7 (4.5) | 6 (6.1) | 1 (1.8) | 0.42 |

| Obstructive chronic bronchitis | n = 153 | 11 (7.2) | 5 (5.1) | 6 (10.9) | 0.20 |

| Charlson score | n = 155 | 0.88 | |||

| 0 | 66 (42.6) | 44 (44.4) | 22 (39.3) | ||

| 1-2 | 77 (49.7) | 48 (48.5) | 29 (51.8) | ||

| 3-4 | 9 (5.8) | 5 (5.1) | 4 (7.1) | ||

| ≥5 | 3 (1.9) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (1.8) | ||

| Period of inclusion | n = 155 | 0.09 | |||

| April–May 2020 | 94 (60.6) | 65 (65.7) | 29 (51.8) | ||

| February–March 2021 | 61 (39.4) | 34 (34.3) | 27 (48.2) | ||

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables are expressed as number of patients (percentage). N: number of patients with available data. COVID-19 deterioration was defined as a need for nasal oxygen flow at or above 6 L/min.

COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus.

Prevalence of MetS and MetSFPG

Seventy-six patients (46.6%) and 118 (77.6%) patients were obese and overweight/obese (BMI ≥25 kg/m2), respectively, while 126 (81.3%) were defined as having MetS. As shown in Table 2 , 102 (72.3%) patients had android obesity, 135 (89.4%) had a high HbA1c level, 112 (73.7%) had fasting hyperglycemia, 93 (60.0%) had high blood pressure, 66 (43.7%) had high triglycerides levels, and 128 (85.9%) had low HDL cholesterol levels. The specific characteristics for each MetS component are shown in Table 2. The prevalence of MetSFPG was 78.8%.

Table 2.

Metabolic parameters description.

| N | Total | No COVID-19 deterioration n = 99 |

COVID-19 Deterioration n = 56 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waist circumference-related parameters | |||||

| Android obesity | n = 141 | 102 (72.3) | 63 (67.7) | 39 (81.3) | 0.09 |

| Waist circumference in males (cm) | n = 80 | 107 ± 13 | 105 ± 14 | 109 ± 12 | 0.07 |

| Waist circumference in females (cm) | n = 61 | 104 ± 16 | 103 ± 15 | 105 ± 18 | 0.63 |

| Overweightness or obesity | n = 152 | 118 (77.6) | 76 (78.4) | 42 (76.4) | 0.78 |

| Obesity | n = 152 | 70 (46.6) | 48 (49.5) | 22 (40.0) | 0.26 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | n = 152 | 29.8 ± 6.1 | 30.2 ± 6.2 | 29.2 ± 6.1 | 0.42 |

| Glycaemia-related parameters | |||||

| Fasting hyperglycemia | n = 152 | 112 (73.7) | 66 (67.3) | 46 (85.2) | 0.02 |

| Fasting glycemia (mmol/l) | n = 150 | 7.5 ± 3.2 | 7.0 ± 2.6 | 8.3 ± 3.9 | 0.02 |

| Known diabetes | n = 155 | 62 (40.0) | 38 (38.4) | 24 (42.9) | 0.59 |

| HbA1c level ≥5.7% | n = 151 | 135 (89.4) | 83 (85.6) | 52 (96.3) | 0.04 |

| HbA1c (%) | n = 149 | 7.2 ± 2.2 | 7.1 ± 2.2 | 7.5 ± 2.3 | 0.11 |

| Blood pressure –related parameters | |||||

| High Blood pressure | n = 155 | 93 (60.0) | 55 (55.6) | 38 (67.9) | 0.13 |

| Known hypertension | n = 155 | 91 (58.7) | 55 (55.6) | 36 (64.3) | 0,29 |

| Lipid-related parameters | |||||

| Low HDL-cholesterol level | n = 149 | 128 (85.9) | 82 (85.4) | 46 (86.8) | 0.82 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) | n = 149 | 0.85 ± 0.27 | 0.87 ± 0.28 | 0.82 ± 0.27 | 0.30 |

| High triglycerides level | n = 151 | 66 (43.7) | 34 (35.4) | 32 (58.2) | <0.01 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | n = 151 | 1.75 ± 0.83 | 1.72 ± 0.93 | 1.81 ± 0.6 | 0.04 |

| Other parameters | |||||

| Known obstructive sleep apnea | n = 152 | 15 (9.9) | 12 (12.2) | 3 (5.6) | 0.19 |

| Known non-alcoholic steatosis hepatitis | n = 151 | 11 (7.3) | 9 (9.3) | 2 (3.7) | 0.33 |

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables are expressed as number of patients (percentage). N: number of patients with available data.

COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019. Deterioration defined as a need for nasal oxygen flow at or above 6 L/min.

The five components of metabolic syndrome are (i) large waist circumference: waist circumference exceeding 88 cm for women and 102 cm for men, (ii) high HbA1c level (≥5.7%) or fasting hyperglycemia (fasting glycemia ≥6.0 mmol/)L or pharmacologic treatment or known diabetes, (iii) high blood pressure: medical history of hypertension or antihypertensive medication introduced during hospitalization, (iv) high triglycerides level: triglycerides level ≥1.6 mmol/L or routine prescribed fibrate medication, and (v) low HDL-cholesterol level: HDL-cholesterol level <1 mmol/L in males or < 1.6 mmol/L in females or routine prescribed fibrate medication.

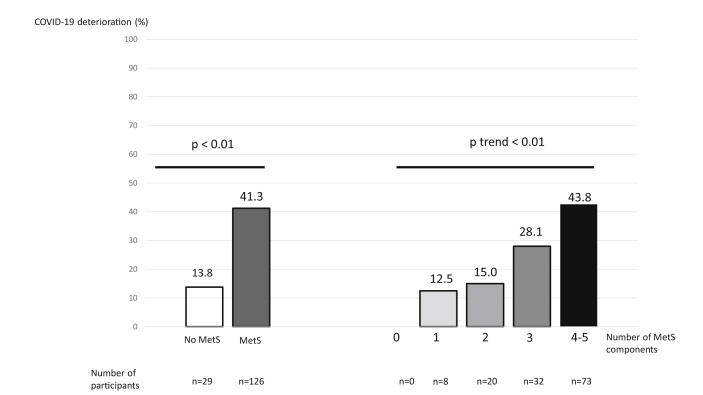

Parameters associated with COVID-19 deterioration

MetS was associated with COVID-19 deterioration (no-MetS vs MetS, 13.8% vs 41.3%, respectively, p < 0.01, Fig. 1 ) and with non-invasive ventilation (3.1% vs 19.1%, respectively, p = 0.05). MetSFPG was also associated with COVID-19 deterioration (no-MetSFPG vs MetSFPG, 15.6% vs 42.0%, respectively, p < 0.01) and with non-invasive ventilation (3.1% vs 19.3%, respectively, p = 0.01). High HbA1c (p = 0.04) (and fasting hyperglycemia, p = 0.02) and high triglycerides level (p = 0.04) were the only MetS components associated with COVID-19 deterioration when analyzed individually (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of COVID-19 deterioration by metabolic syndrome and number of components of metabolic syndrome. COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019. COVID-19 deterioration was defined as a need for nasal oxygen flow at or above 6 L/m.

Patients who experienced COVID-19 deterioration were older and more likely to be male (Table 1).

Logistic regression accounting for MetS, age, gender, ethnicity, period of inclusion, and Charlson Index showed that people in the MetS group were 5.3 times more likely to have COVID-19 deterioration (95% confidence interval 1.3–20.2) than those in the no-MetS group (Table 3 ). Logistic regression accounting for MetSFPG, gender, ethnicity, period of inclusion, and Charlson Index showed that people in the MetSFPG group were 5.2 times more likely to have COVID-19 deterioration (95% confidence interval 1.5–18.4) than those in the no-MetSFPG group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable analyses explaining COVID-19 deterioration.

| Odds Ratios [95% confidence interval] | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (n = 149) | ||

| Metabolic syndrome defined with high HbA1c level | 5.3 [1.4; 20.2] | 0.01 |

| Age (per 10-year interval) | 1.7 [1.2; 2.4] | 0.02 |

| Female gender | 0.5 [0.2; 1.04] | 0.06 |

| Period of inclusion (ref = April May 2020) | 1.5 [0.7; 3.3] | 0.27 |

| Charlson score (by 1 unit) | 0.9 [0.6; 1.2] | 0.5 |

| Afro-Caribbean-Asian ethnicity (ref = Arabic) | 0.7 [0.3; 1.9] | 0.4 |

| Caucasian ethnicity (ref = Arabic) | 0.5 [0.2; 1.3] | 0.4 |

| Model 2 (n = 146) | ||

| Metabolic syndrome defined with fasting hyperglycemia | 5.2 [1.5; 18.5] | <0.01 |

| Age (per 10-year interval) | 1.8 [1.3; 2.6] | <0.001 |

| Female gender | 0.4 [0.2; 0.9] | 0.03 |

| Period of inclusion (ref = April May 2020) | 1.4 [0.6; 3.2] | 0.4 |

| Charlson score (by 1 unit) | 0.8 [0.6; 1.2] | 0.3 |

| Afro-Caribbean-Asian ethnicity (ref = Arabic) | 0.7 [0.3; 1.9] | 0.3 |

| Caucasian ethnicity (ref = Arabic) | 0.5 [0.2; 1.2] | 0.3 |

COVID-19 deterioration was defined as a need for nasal oxygen flow at or above 6 L/min.

Data for all five components of MetS were available for 133 patients. The higher the number of components, the more frequent the deterioration of COVID-19 infection (p trend ≤0.01) (Fig. 1).

Discussion

The main results of our observational study in a multiethnic population admitted to the four COVID-19 departments (excluding ICU) in Avicenne Hospital after transfer from the hospital's emergency department were (i) the very high prevalence of MetS (>80%) and (ii) the fact that patients with MetS were five times more likely to have COVID-19 deterioration than patients without MetS, after multivariable adjustment. Our results also suggest that the higher the number of MetS components, the more frequent the deterioration of the infection. Accordingly, MetS should be considered a composite predictor of COVID-19 deterioration.

Two studies from the USA, which instead of waist circumference considered BMI to measure the obesity component, reported a prevalence of MetS of 66% in 287 hospitalized COVID-19 patients in New Orleans, LA [12], and of 30.6% in 1871 patients [13]. Another study, which took place in a ICU in Teheran, Iran, reported a prevalence of MetS of 47.1% in 157 patients [15].

In our study sample, more than 14.2% of patients met all five components of MetS. The prevalences of each component (i.e., taken individually) have not been studied equally in the literature for COVID-19 patients. In studies in Europe and the USA, pre-diagnosed type 2 diabetes prevalence in patients admitted to COVID-19 units (excluding ICU) was between 30 and 60% [16]. The few available data on fasting hyperglycemia suggest a prevalence of between 50% and 62% [17,18]. Hypertension was much more prevalent in our study (60.0%) than in the literature (approximately 17%) [19]. We did not find any other study exploring the prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia. One previous study reported that approximately 20% of its study population had low HDL cholesterol [20].

Our results suggest that MetS was independently associated with COVID-19 deterioration. In two different studies, it was associated with mortality, invasive mechanical ventilation, and ICU transfer for COVID-19 [12,13]. In the study from Iran having included only patients admitted in ICU, the patients with MetS as compared to those without had a 3.3-fold increased risk of death [15].

In our study and as in another one [15], we found an association between a higher number of MetS components and more frequent COVID-19 deterioration. It would suggest that inter-association between all five MetS components, and their association with the disease, should be taken into account in order to identify patients most at risk of COVID-19 deterioration. Elsewhere, plasma glucose levels and obesity at hospital admission have been associated with poor prognosis in COVID-19 patients with diabetes [21]. Interestingly, another study highlighted that COVID-19 prognosis associated with type 1 diabetes was better than that for type 2 diabetes after adjustment for age [22], probably because individuals with type 1 diabetes rarely meet the criteria for MetS, especially android obesity.

COVID-19 deterioration is characterized by late and sudden respiratory deterioration (day 7–10) driven by a cytokine storm, resulting in lung infiltration and hyperactivation of innate immune cells [23]. Visceral fat, which characterizes MetS, is a well-known trigger of low-grade systemic and chronic inflammation [24,25]. This permissive inflammatory environment increases the COVID-19 cytokine inflammatory storm and induces acute respiratory distress syndrome [24]. Furthermore, obesity is associated with leptin resistance [26]. It impacts T-cells and natural killer cell differentiation and alters T CD8 and regulatory T-cells’ number and function, inducing immunodepression [27].

One limitation of our work is that the study population was not representative of all COVID-19-infected patients as we only investigated patients admitted for infection. Therefore, our results only apply to patients whose symptoms were too severe for them to be released home—either because of respiratory symptoms or severe comorbidities—but not severe enough to warrant being transferred to ICU or directly intubated. We had considered that waist circumference would have been difficult to measure in patients in ICU. The study is small but we recruited 155 patients when 120 were necessary according to power calculation. The retrospective nature of our study exposed to risk for bias due to its and potential for missing or misclassified data. The strengths of our study include a multiethnic cohort likely to be translatable to different populations, despite single center lacking generalizability, and a pragmatic guidance-based approach. Finally, we defined MetS with its classical definition, considering especially waist circumference and triglycerides/HDL cholesterol measurements. But we used HbA1c instead of fasting plasma glucose, as the latter may increase due to stress [28]. However, we found similar results for MetS and MetSFPG.

Conclusion

Approximately 80% of patients admitted to Avicenne Hospital, Bobigny, France, for COVID-19 who had MetS. The patients with MetS might present with five times the risk of deterioration as compared to patients without MetS. Identifying metabolic syndrome at admission could improve capacity of caregivers to predict COVID-19 deterioration.

Contributors

EO, LA, OB, and EC conceived and designed this study and had full access to all of the study data. They take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses. JM, CB, and HB helped design the study and searched existing literature. EO, LA, IR, and EC collected the data, and EO, LA, and EC drafted the paper. LA, EO, EC, and CJ performed the analyses. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and gave final approval for the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy and integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Sources of funding

LVL medical partly funded this study

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Acknowledgments

Our thanks to LVL Medical who partly funded this study. They were not involved in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data. Neither were they involved in writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

We also thank Rachida Mazouzi, Flory Mfutila Kaykay, Phuc Thu Trang Nguyen, Dr. Fatma Kort, and Dr. Julien Caliez for their help in collecting data. Furthermore, we thank SANOÏA-Real World Digital CRO for digital data collection and data management services and Jude Sweeney (Milan, Italy) for the English editing and revision of the manuscript.

Handling Editor: A. Siani

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2021.08.036.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Multimedia component 2

References

- 1.Santé Publique France . Santé Publique France; 2021. Chiffres clés et évolution de la covid 19 en France et dans le monde.https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/dossiers/coronavirus-covid-19/coronavirus-chiffres-cles-et-evolution-de-la-covid-19-en-france-et-dans-le-monde [Internet] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cegolon L., Pichierri J., Mastrangelo G., Cinquetti S., Sotgiu G., Bellizzi S. Hypothesis to explain the severe form of COVID-19 in Northern Italy. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kragholm K., Andersen M.P., Gerds T.A., Butt J.H., Østergaard L., Polcwiartek C. Association between male sex and outcomes of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) - a Danish nationwide, register-based study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Jul 8 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walter L.A., McGregor A.J. Sex- and gender-specific observations and implications for COVID-19. West J Emerg Med. 2020 10;21(3):507–509. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.4.47536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang I., Lim M.A., Pranata R. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia - a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020 Aug;14(4):395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kulkarni S., Jenner B.L., Wilkinson I. COVID-19 and hypertension. J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst JRAAS. 2020 Jun;21(2) doi: 10.1177/1470320320927851. 1470320320927851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu X., Chen D., Wu L., He G., Ye W. Declined serum high density lipoprotein cholesterol is associated with the severity of COVID-19 infection. Clin Chim Acta. 2020 Jul 10;510:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamara A., Tahapary D.L. Obesity as a predictor for a poor prognosis of COVID-19: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020 Aug;14(4):655–659. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simonnet A., Chetboun M., Poissy J., Raverdy V., Noulette J., Duhamel A. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity. 2020 Apr 9 doi: 10.1002/oby.22831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiappetta S., Sharma A.M., Bottino V., Stier C. COVID-19 and the role of chronic inflammation in patients with obesity. Int J Obes. 2020;44(8):1790–1792. doi: 10.1038/s41366-020-0597-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang P.L. A comprehensive for metabolic syndrome. Dis Model Mech. 2009 Jun;2(5–6):231–237. doi: 10.1242/dmm.001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie J., Zu Y., Alkhatib A., Pham T.T., Gill F., Jang A. Metabolic syndrome and COVID-19 mortality among adult black patients in new Orleans. Diabetes Care. 2020 Aug 25 doi: 10.2337/dc20-1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lohia P., Kapur S., Benjaram S., Pandey A., Mir T., Seyoum B. Metabolic syndrome and clinical outcomes in patients infected with COVID-19: does age, sex, and race of the patient with metabolic syndrome matter? J Diabetes. 2021 Jan 16 doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.13157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charlson M.E., Pompei P., Ales K.L., MacKenzie C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alamdari N.M., Rahimi F.S., Afaghi S., Zarghi A., Qaderi S., Tarki F.E. The impact of metabolic syndrome on morbidity and mortality among intensive care unit admitted COVID-19 patients. Diabetes & Metab Syndr: Clin Res Rev. 2020 Nov;14(6):1979–1986. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh A.K., Gupta R., Ghosh A., Misra A. Diabetes in COVID-19: prevalence, pathophysiology, prognosis and practical considerations. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020 Aug;14(4):303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Q., Chen H., Li J., Huang X., Lai L., Li S. Fasting blood glucose predicts the occurrence of critical illness in COVID-19 patients: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. J Infect. 2020;81(3):e20–e23. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu J., Huang J., Zhu G., Wang Q., Lv Q., Huang Y. Elevation of blood glucose level predicts worse outcomes in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrera F.J., Shekhar S., Wurth R., Moreno-Pena P.J., Ponce O.J., Hajdenberg M. Prevalence of diabetes and hypertension and their associated risks for poor outcomes in covid-19 patients. J Endocr Soc. 2020 Sep 1;4(9):bvaa102. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvaa102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang G., Zhang Q., Zhao X., Dong H., Wu C., Wu F. Low high-density lipoprotein level is correlated with the severity of COVID-19 patients: an observational study. Lipids Health Dis. 2020 Sep 7;19(1):204. doi: 10.1186/s12944-020-01382-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cariou B., Hadjadj S., Wargny M., Pichelin M., Al-Salameh A., Allix I. Phenotypic characteristics and prognosis of inpatients with COVID-19 and diabetes: the CORONADO study. Diabetologia. 2020;63(8):1500–1515. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05180-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wargny M., Gourdy P., Ludwig L., Seret-Bégué D., Bourron O., Darmon P. Type 1 diabetes in people hospitalized for COVID-19: new insights from the CORONADO study. Diabetes Care. 2020 Aug 26 doi: 10.2337/dc20-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J., Jiang M., Chen X., Montaner L.J. Cytokine storm and leukocyte changes in mild versus severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: review of 3939 COVID-19 patients in China and emerging pathogenesis and therapy concepts. J Leukoc Biol. 2020;108(1):17–41. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3COVR0520-272R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mauvais-Jarvis F. Aging, male sex, obesity, and metabolic inflammation create the perfect storm for COVID-19. Diabetes. 2020;69(9):1857–1863. doi: 10.2337/dbi19-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McArdle M.A., Finucane O.M., Connaughton R.M., McMorrow A.M., Roche H.M. Mechanisms of obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance: insights into the emerging role of nutritional strategies. Front Endocrinol. 2013;4:52. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meckenstock R., Therby A. [Modifications of immunity in obesity: the impact on the risk of infection] Rev Med Interne. 2015 Nov;36(11):760–768. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ibrahim M.M. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: structural and functional differences. Obes Rev. 2010 Jan;11(1):11–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z., Liu G., Wang L., Liang Y., Zhou Q., Wu F. From the insight of glucose metabolism disorder: oxygen therapy and blood glucose monitoring are crucial for quarantined COVID-19 patients. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020 01;197:110614. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multimedia component 2