Abstract

This study presents a methodology to predict the child poverty impact of COVID-19 that can be readily applied in other country contexts where similar household data are available—and illustrates this case using data from Turkey. Using Household Budget Survey 2018, the microsimulation model estimates the impact of labour income loss on household expenditures, considering that some types of jobs/sectors may be more vulnerable than others to the COVID-19 shock. Labour income loss is estimated to lead to reductions in monthly household expenditure using an income elasticity model, and expenditure-based child poverty is found to increase in Turkey by 4.9–9.3 percentage points (depending on shock severity) from a base level of 15.4%. Among the hypothetical cash transfer scenarios considered, the universal child grant for 0–17 years old children was found to have the highest child poverty reduction impact overall, while schemes targeting the bottom 20–30% of households are more cost-effective in terms of poverty reduction. The microsimulation model set out in this paper can be readily replicated in countries where similar Household Budget Surveys are available.

Keywords: COVID-19, Child poverty, Microsimulations, Cash transfers, Turkey

Résumé

Cette étude présente une méthodologie pour prédire l'impact de la COVID-19 sur la pauvreté infantile et que l’on peut aisément appliquer dans d'autres pays où des données similaires sur les ménages sont disponibles. L’étude illustre ce point en utilisant des données venant de Turquie. À l'aide de l'Enquête sur le budget des ménages de 2018, le modèle de microsimulation estime l'impact de la perte de revenus professionnels sur les dépenses des ménages, en prenant en compte le fait que certains types d'emplois/secteurs peuvent être plus vulnérables que d'autres au choc provoqué par la COVID-19. On estime que la perte de revenus professionnels entraîne des réductions au niveau des dépenses mensuelles des ménages, selon un modèle d'élasticité du revenu, et que la pauvreté infantile – sur la base des dépenses - augmente en Turquie entre 4,9 à 9,3 points de pourcentage (en fonction de la gravité du choc) à partir d'un niveau de base de 15,4 %. Parmi les scénarios hypothétiques de transferts monétaires envisagés, l'allocation universelle pour les enfants de 0 à 17 ans s'est avérée être la mesure qui a l'impact global le plus important sur la réduction de la pauvreté des enfants, tandis que les programmes ciblant les 20 à 30 % des ménages les plus pauvres sont les plus coût-efficaces en terme de réduction de la pauvreté. Le modèle de microsimulation présenté dans cet article peut être facilement reproduit dans les pays où des enquêtes similaires sur le budget des ménages sont disponibles.

Introduction

COVID-19 pandemic, apart from the health-related challenges, has a serious socio-economic impact on households and children. The pandemic is predicted to cause the worst economic recession in decades, with a forecasted 5.2% contraction in global GDP (World Bank 2020b). ILO recently estimated that the pandemic would cause job losses equal to 195 million full-time jobs (ILO 2020a, 2020b). Due to the contraction in economic activities, an estimated 42–66 million children could fall into poverty (UN 2020).

This study presents a methodology to estimate the monetary child poverty impact of the COVID-19 pandemic through a shock on the labour income of the individuals using an ex-ante microsimulation model. The model and the methodology could be applied in any country with available household-level data. The study focuses on the case of Turkey, providing poverty predictions along with an estimation of the impact of possible hypothetical cash transfer scenarios to alleviate the negative impact on households. The study focuses on the impact of the shock on household expenditures and hence on expenditure-based poverty.1 The model estimates the possible impact of COVID-19 on household labour income and then on household expenditure that will decrease as a result of loss of jobs or reduced labour income. After estimating the impact of the shock on household income and expenditures, the same model is used to estimate the possible impact of cash transfers distributed to various target groups to alleviate this negative income effect. The impact of cash transfers on outcomes such as overall poverty and child poverty are estimated along with the total cost and cost-effectiveness of each scenario.

Ex-ante microsimulation models have been used to estimate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on monetary poverty for several countries. Uruguay (Brum and De Rosa 2021), Mynmar (Diao and Mahrt 2020), Colombia (Cuesta and Pico 2020), Brazil (Cereda et al. 2020), Argentina and Mexico (Lustig et al. 2020a, 2020b), Australia (Phillips et al. 2020; Li et al. 2020), Ecuador (Jara et al. 2021), Ghana (Dzigbede and Pathak 2020), Ethiopia (Nechifor et al. 2020), Kenya (Nafula et al. 2020), United States (Giannarelli 2020a, 2020b), East Asia and Pasific countries (World Bank 2020e), South Africa (Chitiga‐Mabugu et al. 2020; Chitiga et al. 2020), Bolivia (Escalante and Maisonnave 2021), Malawi (Baulch et al. 2020), Bangladesh (Genoni et al. 2020), the Western Balkan countries, (World Bank 2020d), the United Kingdom (Bronka et al. 2020; Brewer and Tasseva 2020) and Iraq (World Bank 2020a) are among the countries for which microsimulation models were used to estimate the impact of COVID-19 on poverty. However, expenditure-based absolute poverty rates are estimated only for Ghana, Ethiopia, Kenya and Bangladesh, while income-based relative poverty estimations are used in the studies for other countries. In addition to the impact of the pandemic on poverty, many of these studies also estimate the possible impact of existing policies and different scenario proposals to mitigate this negative impact. Nonetheless, none of these studies estimates the impact of COVID-19 and different scenarios on child poverty, except the study of Brewer and Tasseva (2020).

Microsimulation models are also applied for the European Union countries. Kneewshaw et al. (2021), Almeida et al. (2020) and Palomino et al. (2020) estimate the impact of COVID-19 on poverty for all European Union countries. In addition, country-specific studies have been conducted for Ireland (Doorley et al. 2020; Regan and Maître 2020), Italy (Figari and Fiorio 2020), Finland (Kyyrä et al. 2021), Germany (Bruckmeier et al. 2020), and Malta (Vella and Misfud 2020). In all these studies, income-based poverty estimates are used. As in other countries mentioned above, the possible mitigating impact of existing policies and different scenario proposals are also examined in many of these studies for the EU countries. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child poverty is included in the studies conducted for the EU countries more frequently. Kneewshaw et al. (2021), Figari and Fiorio (2020), Vella and Misfud (2020), and Regan and Maitre (2020) are among these studies, estimating child poverty rates using income-based data.

This paper contributes to the literature by providing an easily adaptable methodology for estimating expenditure-based and absolute child poverty rates in countries where Household Budget Surveys are collected. The paper also contributes to the policy debate in Turkey by providing estimates on the impact of COVID-19 on child poverty and looking at the relative effectiveness of social protection measures, where no such papers have been published looking specifically at the child poverty impact of COVID-19. By providing cash transfer mitigation options for reducing the impact of COVID-19, specifically on households with children, the paper provides some evidence-base for the policy debate in Turkey.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: the data used for the analysis (Household Budget Survey 2018) is described, and the methodology of the micro-simulation model is explained in the “Data and Methodology” section. This section is followed by the “Main Results” section explaining the findings of the model. Lastly, the article ends with the conclusions.

Data and Methodology

Data

The microsimulation model uses the Household Budget Survey (HBS) 2018 collected annually by TURKSTAT, as the primary data source (TURKSTAT 2019). 2018 Turkey Household Budget Survey, which is the latest HBS available at the time of the study had an effective sample size of 11,828 households and is representative at the national level. HBS is composed of three datasets, individual, household and consumption expenditure of the household. The survey provides information on monthly household consumption and individual information on employment and income received during the last 12 months. The survey also includes information on household demographics, sector and type of employment of employed individuals and social assistance income received by the household.

HBS is selected for this exercise in Turkey because it is the only data set that includes information on household expenditure, income, and employment of household members in the same survey.2 The main variables used in our model are household expenditure, household members’ income, sector, employment status, occupation and all these variables are also typically included in the Household Budget Surveys of other countries. Therefore, the methodology provided by this study can be used by the countries with household budget surveys by making different assumptions according to the countries’ own situations for the shock created by the COVID-19 pandemic. Along with the impact of this pandemic on expenditure-based poverty and child poverty, the possible mitigating impact of transfers designed in various ways to alleviate this negative impact can be predicted.3

Background on COVID-19 Impact in Turkey

Similar to many countries across the world, Turkey has also experienced a significant recession as a result of the pandemic. As labour market parameters for the model, we use the latest published Labour Force Statistics Report by Turkish Statistical Institute (TURKSTAT) at the time of preparation of this study. These data were released on September 10, 2020 and give the most up to date information on the effect of COVID-19 on employment for the period June 2020.4 According to the report, although the unemployment rate is 13.4% and is only slightly more than the unemployment rate at the same time a year ago (13%), sharp decreases in the number of employed and the rate of employed can be observed. The total number of employed individuals decreased by 1 million 981 thousand compared to the same time a year ago, corresponding to a 6.9% decrease.

In the past, changes in household labour income have been instrumental in pushing people into poverty in Turkey. Şeker and Dayıoğlu (2015) show that the primary reason triggering a fall into poverty is first a change in household head’s labour income (43.5%) followed by changes in other members’ labour income (21%). Changes in rental or property income (16.1%), changes in social assistance income (7.8%) and demographic events (5.1%) all come after labour income changes. Focusing on child poverty, Dayıoğlu and Şeker (2016) also show that 71.9% of exits from and 73.8% of entries into poverty originate from household members’ labour income. This is the case, indeed, given the fact that household labour market earnings constitute the majority of the household income for both poor and non-poor households.

Several studies report findings on the relationship between COVID-19 and employment, income, poverty, or inequality for Turkey. Demir Seker et al. (2020) develop an Employment Vulnerability Index to identify the sectors that are more vulnerable to the COVID-19 crisis in Turkey. They find that (i) textile and apparel, (ii) accommodation and food, and (iii) leather sectors are the most vulnerable sectors, while ICT and finance sectors are the least vulnerable. The effects of the COVID-19 on the income of households are simulated for Turkey by the World Bank recently, using Household Budget Survey (HBS) 2018 (World Bank 2020c). In the report, the income-based poverty rate is estimated to increase from 10.4 to 14.4% after the labour income shock due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies prepared in Turkey so far do not focus on changes in expenditure-based measures of poverty and also do not focus on child poverty as an outcome.

Turkey implemented several measures as a response to alleviate the shock by the COVID-19 crisis, including one-off cash transfers. First, a TRY 100-billion economic policy package “Economic Stability Shield Program” that includes credits, tax and labour incentives, was announced in March 2020 (EY 2020). The government continued introducing other measures or extending the already introduced ones upon need. The social protection responses among the introduced measures by the government include social assistance, social insurance and labour market measures (Gentilini et al. 2020). Social insurance responses of Turkey targeted pensioners while labour market responses aimed to compensate for the lost income of workers and amounts of certain social assistance programs were increased. Social assistance measures included a one-time cash transfer of 1000 TL to families who are already receiving social assistance in the first two phases and then in a later phase to families in need and applying for social assistance, reaching a total of 6.11 million households (World Bank 2020c). Most recently in early May 2021, in a fourth phase, a second instalment of 1100 TL is announced to be made to those households that received transfers in the third phase (MoFSS 2021).

Methodology and Application to Turkish Household Data

In this section, we outline the main steps we took in modelling the impact of COVID-19 on poverty, child poverty, and inequality using HBS dataset.

Simulating the Poverty (Increasing) Impact of COVID-19

In this study, we focus on the transmission mechanisms through a loss of jobs and reduced labour income to show the impact of COVID-19 on households. We use the expenditure information collected in HBS 2018 to construct the monthly household and per capita expenditure and calculate baseline expenditure poverty measures prior to the COVID-19 shock.5 After the calculation of baseline poverty, child poverty and inequality rates, new poverty and inequality levels are calculated after introducing an income shock to the labour income of the individuals which is then reflected on monthly household expenditure.

The latest Labour Force Statistics Report published by TURKSTAT, at the time of writing this paper, in September 2020 (for June 2020) provides information with regards to the jobs/sectors that may be more vulnerable than others to this shock by providing statistics on the rate of reduction in the total number of employed by sector, job status and occupation type compared to the same time previous year (TURKSTAT 2020). Since the report provides information about the loss of jobs compared to the same time previous year, we make use of this information on the vulnerability of sectors and occupations and come up with assumptions on the level of income loss for the individuals in each sector and occupation. 6

Using this information from the Labour Force Statistics Report, we first construct a sectoral based labour income loss coefficient ranging between 0% (no loss) and 100% (total loss of income, i.e. unemployment) in the HBS dataset. The labour income loss coefficient uses sector of employment, employment status and occupation type information. In doing this, we first assign a prior income loss coefficient by sector to each working individual (See Table 1). We assume two levels of shock, mild and severe. In the mild shock, we assume the degree of income loss to be ordinally aligned with the level of reduction in employment in these sectors as of June 2020 (See Table 1). The severe shock assumes that the sectors will be hit twice as hard in terms of employment within a year. Since the highest contraction in the number of employed was in the service sector in the latest Labour Force Statistics Report, we assign the highest prior income loss coefficients in this sector. However, since this report does not provide the information on the rate of reduction in the total number of employed in the sub-sectors of the service sector and that we think that the income shock effect differs in these sub-sectors, we assign differing prior income loss coefficients to these sub-sectors. Since the sectors such as wholesale and retail trade, transportation and storage, and accommodation and food service activities can be affected the most from this shock, the highest prior income loss coefficients are assigned to these sectors. Additionally, the sectors such as financial and insurance activities, public administration, education, information and communication, and human health and social work activities can be affected the least, we assign the lowest prior income loss coefficients to these sectors.7

Table 1.

Prior income loss coefficient based on sector of the main job of the individual

| Sector | Subsector (NACE Rev 2) | Income shock on wage workers—Mild (% wages) | Income shock on wage workers—severe (% wages) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing | 15 | 30 |

| Industry | Mining and Quarrying | 15 | 30 |

| Manufacturing | 15 | 30 | |

| Electricity, Gas, Steam and Air Conditioning Supply | 0 | 0 | |

| Water Supply, Sewerage, Waste Management and Remediation Activities | 0 | 0 | |

| Construction | 15 | 30 | |

| Services | Wholesale and Retail Trade; Repair of Motor Vehicles, Motorcycles and Personal and Household Goods | 25 | 50 |

| Transportation and Storage | 25 | 50 | |

| Accommodation and Food Service Activities | 25 | 50 | |

| Information and Communication | 5 | 10 | |

| Financial and Insurance Activities | 0 | 0 | |

| Real Estate Activities | 5 | 10 | |

| Professional, Scientific and Technical Activities | 5 | 10 | |

| Administrative and Support Service Activities | 5 | 10 | |

| Public Administration and Defence, Compulsory Social Security | 0 | 0 | |

| Education | 5 | 10 | |

| Human Health and Social Work Activities | 0 | 0 | |

| Arts, Entertainment and Recreation | 25 | 50 | |

| Other Service Activities | 10 | 20 | |

| Activities of Households as Employers | 25 | 50 | |

| Activities of Extraterritorial Organisations and Bodies | 0 | 0 |

As the contraction in the number of employed in other sectors other than the service sector (i.e. agriculture, industry, and construction) is smaller and similar to each other in the TURKSTAT report, we assign the same and smaller prior income loss coefficients to these sectors compared to the service sector. Besides, we assign the lowest prior income loss coefficient to the two sub-sectors in the industry sector (i.e. electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply and water supply, sewerage, waste management and remediation activities), since these sub-sectors can be affected the least from the income shock.

Next, the income loss is amplified or reduced by the employment status of each worker accounting for differences across regular employees, casual employees and self-employed. For regular employees, occupation type of the individuals within each sector is also taken into account (See Table 2). In this respect, employers, unpaid family workers, and regular waged employees who are craft and related trade workers and service and sales workers are the most vulnerable in each sector in terms of wage loss while regular waged employees who are managers, clerical support workers, and skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers are the least vulnerable (in line with the contraction in the number of employed as reported in TURKSTAT Labour Force Statistics Report, June 2020). Hence, we assign the employment status and occupation multiplier accordingly. Even though regular waged employees who are professionals have an increase in the number of employed in the report, we still assign a larger than 0 employment status and occupation multiplier since they may still be vulnerable to income losses, although smaller. The other employment statuses and occupations in each sector have medium-vulnerability in terms of contraction in the number of employed according to TURKSTAT Labour Force Statistics Report, so we assign a moderate employment status and occupation multiplier for them.8

Table 2.

Employment status and occupation multiplier

| Employment status and occupation multiplier | |

|---|---|

| Regular employee (wage earner) | |

| Managers | 1 |

| Professionals | 0.25 |

| Technicians and Associate Professionals | 1.5 |

| Clerical Support Workers | 1 |

| Service and Sales Workers | 2 |

| Skilled Agricultural, Forestry and Fishery Workers | 1 |

| Craft and Related Trades Workers | 2 |

| Plant and Machine Operators and Assemblers | 1.5 |

| Elementary Occupations | 1.5 |

| Casual employee (seasonal workers or daily work) | 1.5 |

| Employer | 2 |

| Self-employed | 1.5 |

| Unpaid family worker | 2 |

Following this adjustment, the income loss coefficient is calculated for each working individual as follows:

| 1 |

In this respect, the after shock, individual labour income is calculated for each employed person as follows9:

| 2 |

In the 2018 HBS, there are 14,320 employed individuals out of a total of 30,737 individuals aged 15 or above.10 For all of those individuals, baseline labour income is calculated as a sum of in-cash labour income, in-kind labour income, in-cash entrepreneurial income, in-kind entrepreneurial income and agricultural income.11,12

Baseline labour income is 0 for 1286 employed individuals and missing for 108 employed individuals out of 14,320. 90 out of these 108 employed individuals whose baseline labour income information is missing are unpaid family workers and their baseline labour incomes are assumed as 0. For the other 18 individuals who are working as a regular or casual employee, self-employed or employer and who do not have a reported income in the data, baseline labour income is imputed based on the following regression model:

| 3 |

After the regression, the income information for 1 individual is less than 0 in the data, and her income is changed as 0.

The after-shock individual labour income is calculated for each employed individual according to the Eq. (2) stated above for mild shock and severe shock separately. For those employed individuals without health insurance (910 individuals out of 14,320), after shock labour income was taken as 0 for both shock levels as they are assumed to be working informally and to be unemployed after the shock.

Next, the `after shock` total household labour income is calculated by adding up the total labour income of each working individual in the household for both shock levels.13 The proportion of the total household labour income lost after shock (i.e. household income loss coefficient) compared to the baseline level is calculated as follows:

| 4 |

The household income loss coefficient is calculated for both the mild and the severe shock.

Lastly, the loss of household labour income is mapped to a decrease in household expenditures using income elasticities calculated from the baseline data. In most cases, the loss in income is not equal to a one-to-one decline in expenditures, and this “income elasticity” is calculated in this analysis using the cross-sectional data. Hence the loss of household labour income is mapped to a decrease in household expenditures using income elasticities calculated through a regression model in the baseline prior to the shock:

| 5 |

where Expenditureİ and Incomeİ represent the monthly household expenditure and monthly household labour income for household i.

Hence total monthly household expenditure after the shock is equal to:

| 6 |

where the household income loss coefficient ranges between 0 and 1 and changes based on mild or severe shock and types of sector and employment status of individuals in the household as depicted in Tables 1 and 2. And is found to be equal to 0.382 (See Table 3 for the regression results) and can be interpreted as a 100% reduction in household income being associated with a 38.2% reduction in household expenditures.14 The after-shock household expenditure is calculated for both levels of the shock.

Table 3.

Regression results

| Variables | ln(before shock monthly household expenditure) |

|---|---|

| ln(before shock monthly household income) | 0.382*** |

| (0.010) | |

| Household size | 0.014*** |

| (0.004) | |

| Constant | 5.187*** |

| (0.082) | |

| Observations | 9165 |

| R-squared | 0.296 |

| Robust standard errors in parentheses |

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1

After estimating the monthly household expenditure, the outcome variables like expenditure-based poverty, child poverty and inequality are recalculated in the occurrence of a mild or severe shock. The poverty lines used for the analysis are the 1.9 USD, 3.2 USD and 5.5 USD per capita per day poverty lines.15 Since the labour income loss coefficient is constructed based on “TURKSTAT Labour Force Statistics Report, June 2020”, the impact of shocks could be taken as of June 2020.

Simulating the Poverty (Reducing) Impact Under Various Cash Transfer Policy Scenarios

After the household level shocks occur, and poverty rates are re-estimated based on the model, various targeting cash transfer scenarios are applied to see their poverty alleviating impact.

We simulate seven different cash transfer scenarios in two different transfer levels (low and high). The transfer can be per household or per child, and the targeted groups change from being universal to targeting by household baseline expenditure level.16 The full list of policy scenarios considered for the exercise is listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Cash transfer scenarios

| Transfer level | Scenario number | Scenario explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Low transfer | 1 | Per child transfer of 150 TL to all families with children (0–5 years old) (Universal Child Grant) |

| 2 | Per child transfer of 150 TL to all families with children (0–17 years old) (Universal Child Grant) | |

| 3 | Per household transfer of 300 TL to families with children in the bottom 20% | |

| 4 | Per household transfer of 300 TL to all households in the bottom 20% | |

| 5 | Per household transfer of 300 TL to families with children in the bottom 30% | |

| 6 | Per household transfer of 300 TL to all households in the bottom 30% | |

| 7 | Per household transfer of 300 TL to all households who already receive social assistance as income | |

| High transfer | 1 | Per child transfer of 250 TL to all families with children (0–5 years old) (Universal Child Grant) |

| 2 | Per child transfer of 250 TL to all families with children (0–17 years old) (Universal Child Grant) | |

| 3 | Per household transfer of 500 TL to families with children in the bottom 20% | |

| 4 | Per household transfer of 500 to all households in the bottom 20% | |

| 5 | Per household transfer of 500 TL to families with children in the bottom 30% | |

| 6 | Per household transfer of 500 to all households in the bottom 30% | |

| 7 | Per household transfer of 500 TL to all households who already receive social assistance as income |

We assume that the cash transfers will be spent directly rather than saved since this is a crisis and households are already impoverished and the transfer amounts are much smaller compared to average loss in household labour income.17 Hence the transfers are directly added to after shock monthly household expenditure, and the outcomes such as poverty, child poverty and inequality are re-calculated using the increased household expenditure levels.,18,19 The total monthly cost of each scenario, coverage and benefit incidence (targeting) performance of each scenario as well as cost-effectiveness of the scenarios are provided in the set of simulation results.20

Main Results

In this section, the results of the micro-simulation model are presented and explained. The section first starts with the estimated impact of the shocks on poverty, child poverty and inequality. Next, the impact of various cash transfer scenarios after the shocks is estimated and presented in the second part of the section.

Simulating the Poverty (Increasing) Impact of COVID-19

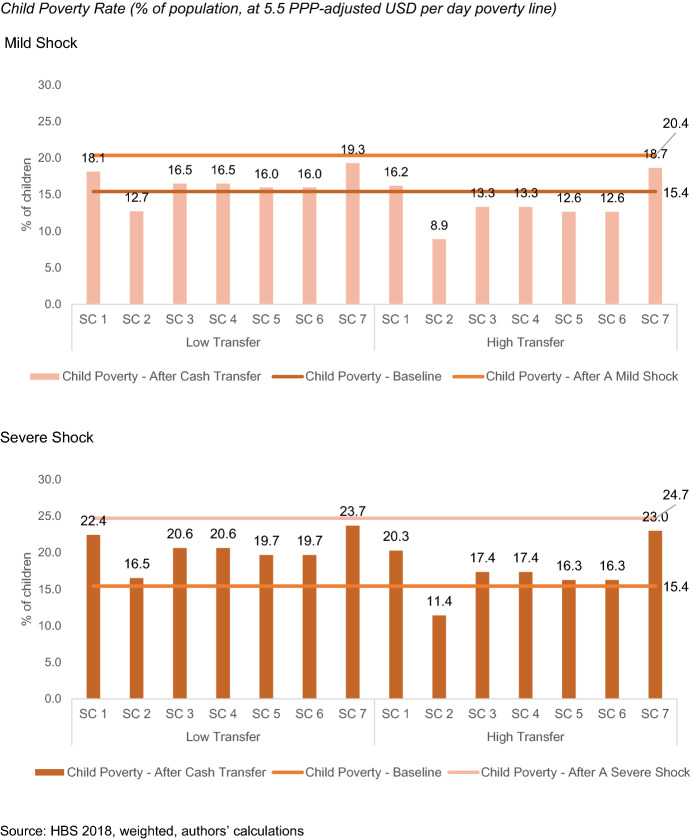

As a result of the simulated labour income shock that is experienced by households, monthly per capita expenditure shrinks for the households receiving the income shock (See Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Monthly per capita expenditure shrinks for the households in Turkey receiving an income shock, pushing some households below the poverty lines.

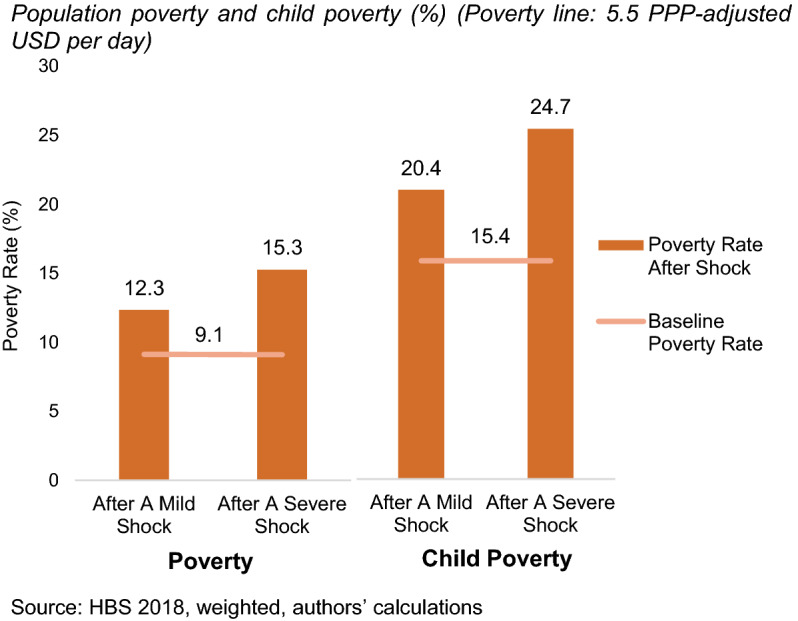

Reductions in monthly household expenditure lead to significant increases in expenditure-based poverty and child poverty. Child poverty gives the percentage of children living in poor households. In the baseline, 9.1% of the population and 15.4% of children are living below the 5.5 PPP-adjusted USD per capita per day poverty line (i.e. 372 TL per month).21 Population poverty rate increases to 12.3% after a mild shock and to 15.3% after a severe shock. Similarly, child poverty increases to 20.4% and to 24.7% after a mild and a severe shock, respectively (See Fig. 2). Not only the poverty headcount rate but also the poverty gap (P1) and the poverty severity (P2) indicators increase after the shocks (See Table 5).

Fig. 2.

Reductions in the household expenditure lead to significant increases in poverty and child poverty.

Table 5.

Poverty and inequality in the baseline and after each shock

| Baseline | After A Mild Shock | After A Severe Shock | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poverty line: 1.9 USD per day (129 TL per month) | |||

| Number of poor people (millions)a | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.30 |

| Poverty rate (P0) | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Poverty gap (P1) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Poverty severity (P2) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Number of poor children (millions)b | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.15 |

| Child poverty rate | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Poverty line: 3.2 USD per day (217 TL per month) | |||

| Number of poor people (millions)a | 1.18 | 2.05 | 2.88 |

| Poverty rate (P0) | 1.4 | 2.5 | 3.5 |

| Poverty gap (P1) | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| Poverty severity (P2) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Number of poor children (millions)b | 0.62 | 1.03 | 1.41 |

| Child poverty rate | 2.7 | 4.5 | 6.2 |

| Poverty line: 5.5 USD per day (372 TL per month) | |||

| Number of poor people (millions)a | 7.49 | 10.13 | 12.51 |

| Poverty rate (P0) | 9.1 | 12.3 | 15.3 |

| Poverty gap (P1) | 2.1 | 3.2 | 4.2 |

| Poverty severity (P2) | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.6 |

| Number of poor children (millions)b | 3.54 | 4.67 | 5.66 |

| Child poverty rate | 15.4 | 20.4 | 24.7 |

| Gini | 41.9 | 43.1 | 44.0 |

aSince we use the 2018 HBS in our analysis, we use the 2018 population. The total population in 2018 is 82 million. Retrieved from: http://www.tuik.gov.tr/PreIstatistikTablo.do?istab_id=1588

bThe child population between the ages of 0–17 in 2018 is 22.9 million. Retrieved from: http://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/medas/?kn=206&locale=tr

As poverty rates severely increase, inequality also increases considerably. Initially, the Gini index was calculated as 41.9 using households’ monthly per capita expenditure levels. This rate increases to 43.1 after a mild shock and to 44.0 after a severe shock (See Table 5).

Simulating the Poverty (Reducing) Impact Under Cash Transfer Policy Scenarios

To combat the poverty impact of the COVID-19, a number of different cash transfer scenarios are modelled as described in the “Data and Methodology” section. Seven scenarios with two different transfer levels are modelled after a mild and a severe shock separately, making a total of 14 scenarios for each shock (See Table 4). Outcome variables including poverty, child poverty, and inequality after the transfers and total monthly cost of the scenarios and their cost-effectiveness are calculated (See Tables 6 and 7 for the results in detail). All poverty calculations use the 5.5 PPP-adjusted USD per capita per day poverty line and household’s per capita monthly expenditure is used in the calculations.

Table 6.

Outcomes of cash transfer scenarios when transfers are distributed after a mild shock (Poverty Line: 5.5 PPP-adjusted USD per day)

| Baseline | After a mild shock | Low transfer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | Scenario 4 | Scenario 5 | Scenario 6 | Scenario 7 | |||

| Per child transfer of 150 TL to all families with children (0–5 years old) (Universal Child Grant) | Per child transfer of 150 TL to all families with children (0–17 years old) (Universal Child Grant) | Per household transfer of 300 TL to families with children in the bottom 20% | Per household transfer of 300 TL to all households in the bottom 20% | Per household transfer of 300 TL to families with children in the bottom 30% | Per household transfer of 300 TL to all households in the bottom 30% | Per household transfer of 300 TL to all households who already receive social assistance as income | |||

| Poverty and inequalitya | |||||||||

| Number of poor people (millions) | 7.49 | 10.13 | 9.17 | 6.83 | 8.22 | 7.95 | 7.97 | 7.67 | 9.66 |

| Poverty rate (P0) | 9.1 | 12.3 | 11.2 | 8.3 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 9.4 | 11.8 |

| Poverty gap (P1) | 2.1 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 3.0 |

| Poverty severty (P2) | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.1 |

| Number of poor children (millions) | 3.54 | 4.67 | 4.16 | 2.91 | 3.78 | 3.78 | 3.66 | 3.66 | 4.42 |

| Child poverty | 15.4 | 20.4 | 18.1 | 12.7 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 19.3 |

| Gini | 41.9 | 43.1 | 42.5 | 41.4 | 42.3 | 42.2 | 42.1 | 41.9 | 42.9 |

| Coverage | |||||||||

| Population coverage | 35.4 | 67.0 | 18.6 | 20.0 | 27.1 | 30.0 | 5.6 | ||

| Coverage of children | 58.3 | 100.0 | 31.6 | 31.6 | 44.0 | 44.0 | 9.7 | ||

| Q1 | 59.9 | 92.9 | 92.9 | 100.0 | 92.9 | 100.0 | 18.1 | ||

| Q2 | 41.7 | 81.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 42.3 | 49.9 | 5.5 | ||

| Q3 | 32.8 | 68.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.6 | ||

| Q4 | 22.5 | 51.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | ||

| Q5 | 20.0 | 40.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | ||

| Bottom 40% | 50.8 | 87.0 | 46.5 | 50.0 | 67.6 | 75.0 | 11.8 | ||

| Benefit incidence | |||||||||

| Q1 | 31.2 | 31.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 65.4 | 62.3 | 56.0 | ||

| Q2 | 24.0 | 23.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 34.6 | 37.7 | 21.9 | ||

| Q3 | 18.8 | 19.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.0 | ||

| Q4 | 13.5 | 14.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.8 | ||

| Q5 | 12.5 | 10.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 | ||

| Costsa | |||||||||

| Cost per child reached (TL) | 86.8 | 150.0 | 104.0 | 121.8 | 114.0 | 140.3 | 118.7 | ||

| Cost per person reached (TL) | 41.0 | 64.2 | 50.6 | 55.1 | 53.2 | 59.0 | 58.8 | ||

| Total additional monthly cost (billion TL) | 1.16 | 3.43 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 1.15 | 1.41 | 0.26 | ||

| Total additional annual cost (% of GDP)b | 0.29 | 0.85 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.07 | ||

| Total additional annual cost (% of social protection expenditures)b | 2.43 | 7.21 | 1.58 | 1.85 | 2.41 | 2.97 | 0.55 | ||

| Cost effectiveness (per Billion TL)a | |||||||||

| % Point headcount poverty reduction (P0) | 1.0 | 1.2 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | ||

| % Point poverty gap reduction (P1) | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | ||

| % Point child poverty reduction | 1.9 | 2.2 | 5.1 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 3.1 | 4.1 | ||

| Baseline | After a mild shock | High transfer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | Scenario 4 | Scenario 5 | Scenario 6 | Scenario 7 | |||

| Per child transfer of 250 TL to all families with children (0–5 years old) (Universal Child Grant) | Per child transfer of 250 TL to all families with children (0–17 years old) (Universal Child Grant) | Per household transfer of 500 TL to families with children in the bottom 20% | Per household transfer of 500 to all households in the bottom 20% | Per household transfer of 500 TL to families with children in the bottom 30% | Per household transfer of 500 to all households in the bottom 30% | Per household transfer of 500 TL to all households who already receive social assistance as income | |||

| Poverty and inequalitya | |||||||||

| Number of poor people (Millions) | 7.49 | 10.13 | 8.34 | 5.05 | 6.75 | 6.38 | 6.43 | 6.03 | 9.35 |

| Poverty rate (P0) | 9.1 | 12.3 | 10.2 | 6.2 | 8.2 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 11.4 |

| Poverty gap (P1) | 2.1 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 2.8 |

| Poverty severty (P2) | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| Number of poor children (Millions) | 3.54 | 4.67 | 3.72 | 2.04 | 3.05 | 3.05 | 2.90 | 2.90 | 4.27 |

| Child poverty | 15.4 | 20.4 | 16.2 | 8.9 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 12.6 | 12.6 | 18.7 |

| Gini | 41.9 | 43.1 | 42.1 | 40.3 | 41.9 | 41.7 | 41.4 | 41.1 | 42.8 |

| Coverage | |||||||||

| Population coverage | 35.4 | 67.0 | 18.6 | 20.0 | 27.1 | 30.0 | 5.6 | ||

| Coverage of children | 58.3 | 100.0 | 31.6 | 31.6 | 44.0 | 44.0 | 9.7 | ||

| Q1 | 59.9 | 92.9 | 92.9 | 100.0 | 92.9 | 100.0 | 18.1 | ||

| Q2 | 41.7 | 81.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 42.3 | 49.9 | 5.5 | ||

| Q3 | 32.8 | 68.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.6 | ||

| Q4 | 22.5 | 51.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | ||

| Q5 | 20.0 | 40.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | ||

| Bottom 40% | 50.8 | 87.0 | 46.5 | 50.0 | 67.6 | 75.0 | 11.8 | ||

| Benefit incidence | |||||||||

| Q1 | 31.2 | 31.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 65.4 | 62.3 | 56.0 | ||

| Q2 | 24.0 | 23.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 34.6 | 37.7 | 21.9 | ||

| Q3 | 18.8 | 19.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.0 | ||

| Q4 | 13.5 | 14.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.8 | ||

| Q5 | 12.5 | 10.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 | ||

| Costsa | |||||||||

| Cost per child reached (TL) | 144.7 | 250.0 | 173.4 | 203.0 | 190.0 | 233.8 | 197.9 | ||

| Cost per person reached (TL) | 68.4 | 107.0 | 84.4 | 91.9 | 88.6 | 98.4 | 98.1 | ||

| Total additional monthly cost (Billion TL) | 1.93 | 5.72 | 1.25 | 1.47 | 1.91 | 2.35 | 0.44 | ||

| Total Additional Annual Cost (% of GDP)b | 0.48 | 1.42 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.11 | ||

| Total additional annual cost (% of social protection expenditures)b | 4.06 | 12.02 | 2.63 | 3.08 | 4.02 | 4.95 | 0.92 | ||

| Cost effectiveness (per Billion TL)a | |||||||||

| % Point headcount poverty reduction (P0) | 1.1 | 1.1 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.2 | ||

| % Point poverty gap reduction (P1) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | ||

| % Point child poverty reduction | 2.1 | 2.0 | 5.6 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 3.3 | 3.9 | ||

aSince we use the 2018 HBS in our analysis, we moved the cash transfer values from 2020 to 2018 by using the average monthly CPI for 2018 for the poverty-reducing impact of the cash transfer scenarios. However, since these cash transfers are given in 2020, we use the cash transfer values in 2020 when calculating the total cost and cost-effectiveness of these cash transfers

bAs the latest information on GDP is for 2019, and the most recent information on social protection expenditures is for 2018, we use the 2019 GDP and the 2018 social protection expenditures values. However, using the CPI, we moved the total additional monthly cost from 2020 to the respective years of GDP and social protection expenditures

Table 7.

Outcomes of cash transfer scenarios when transfers are distributed after a severe shock (Poverty Line: 5.5 PPP-adjusted USD per day)

| Baseline | After a severe shock | Low transfer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | Scenario 4 | Scenario 5 | Scenario 6 | Scenario 7 | |||

| Per child transfer of 150 TL to all families with children (0–5 years old) (Universal Child Grant) | Per child transfer of 150 TL to all families with children (0–17 years old) (Universal Child Grant) | Per household transfer of 300 TL to families with children in the bottom 20% | Per household transfer of 300 TL to all households in the bottom 20% | Per household transfer of 300 TL to families with children in the bottom 30% | Per household transfer of 300 TL to all households in the bottom 30% | Per household transfer of 300 TL to all households who already receive social assistance as income | |||

| Poverty and inequalitya | |||||||||

| Number of poor people (Millions) | 7.49 | 12.51 | 11.46 | 8.82 | 10.48 | 10.17 | 10.01 | 9.65 | 12.06 |

| Poverty rate (P0) | 9.1 | 15.3 | 14.0 | 10.8 | 12.8 | 12.4 | 12.2 | 11.8 | 14.7 |

| Poverty gap (P1) | 2.1 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.9 |

| Poverty severty (P2) | 0.7 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.5 |

| Number of poor children (Millions) | 3.54 | 5.66 | 5.14 | 3.78 | 4.73 | 4.73 | 4.51 | 4.51 | 5.43 |

| Child poverty | 15.4 | 24.7 | 22.4 | 16.5 | 20.6 | 20.6 | 19.7 | 19.7 | 23.7 |

| Gini | 41.9 | 44.0 | 43.4 | 42.1 | 43.2 | 43.1 | 42.9 | 42.7 | 43.8 |

| Coverage | |||||||||

| Population coverage | 35.4 | 67.0 | 18.6 | 20.0 | 27.1 | 30.0 | 5.6 | ||

| Coverage of children | 58.3 | 100.0 | 31.6 | 31.6 | 44.0 | 44.0 | 9.7 | ||

| Q1 | 59.9 | 92.9 | 92.9 | 100.0 | 92.9 | 100.0 | 18.1 | ||

| Q2 | 41.7 | 81.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 42.3 | 49.9 | 5.5 | ||

| Q3 | 32.8 | 68.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.6 | ||

| Q4 | 22.5 | 51.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | ||

| Q5 | 20.0 | 40.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | ||

| Bottom 40% | 50.8 | 87.0 | 46.5 | 50.0 | 67.6 | 75.0 | 11.8 | ||

| Benefit incidence | |||||||||

| Q1 | 31.2 | 31.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 65.4 | 62.3 | 56.0 | ||

| Q2 | 24.0 | 23.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 34.6 | 37.7 | 21.9 | ||

| Q3 | 18.8 | 19.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.0 | ||

| Q4 | 13.5 | 14.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.8 | ||

| Q5 | 12.5 | 10.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 | ||

| Costsa | |||||||||

| Cost per child reached (TL) | 86.8 | 150.0 | 104.0 | 121.8 | 114.0 | 140.3 | 118.7 | ||

| Cost per person reached (TL) | 41.0 | 64.2 | 50.6 | 55.1 | 53.2 | 59.0 | 58.8 | ||

| Total additional monthly cost (Billion TL) | 1.16 | 3.43 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 1.15 | 1.41 | 0.26 | ||

| Total additional annual cost (% of GDP)b | 0.29 | 0.85 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.07 | ||

| Total additional annual cost (% of social protection expenditures)b | 2.43 | 7.21 | 1.58 | 1.85 | 2.41 | 2.97 | 0.55 | ||

| Cost effectiveness (per Billion TL)a | |||||||||

| % Point headcount poverty reduction (P0) | 1.1 | 1.3 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.1 | ||

| % Point poverty gap reduction (P1) | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | ||

| % Point child poverty reduction | 2.0 | 2.4 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 3.6 | 3.9 | ||

| Baseline | After a severe shock | High transfer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | Scenario 4 | Scenario 5 | Scenario 6 | Scenario 7 | |||

| Per child transfer of 250 TL to all families with children (0–5 years old) (Universal Child Grant) | Per child transfer of 250 TL to all families with children (0–17 years old) (Universal Child Grant) | Per household transfer of 500 TL to families with children in the bottom 20% | Per household transfer of 500 to all households in the bottom 20% | Per household transfer of 500 TL to families with children in the bottom 30% | Per household transfer of 500 to all households in the bottom 30% | Per household transfer of 500 TL to all households who already receive social assistance as income | |||

| Poverty and inequalitya | |||||||||

| Number of poor people (Millions) | 7.49 | 12.51 | 10.57 | 6.61 | 8.93 | 8.48 | 8.39 | 7.89 | 11.75 |

| Poverty rate (P0) | 9.1 | 15.3 | 12.9 | 8.1 | 10.9 | 10.3 | 10.2 | 9.6 | 14.3 |

| Poverty gap (P1) | 2.1 | 4.2 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 3.7 |

| Poverty severty (P2) | 0.7 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.4 |

| Number of poor children (Millions) | 3.54 | 5.66 | 4.65 | 2.62 | 3.98 | 3.98 | 3.73 | 3.73 | 5.27 |

| Child poverty | 15.4 | 24.7 | 20.3 | 11.4 | 17.4 | 17.4 | 16.3 | 16.3 | 23.0 |

| Gini | 41.9 | 44.0 | 43.0 | 41.0 | 42.7 | 42.6 | 42.2 | 41.9 | 43.7 |

| Coverage | |||||||||

| Population coverage | 35.4 | 67.0 | 18.6 | 20.0 | 27.1 | 30.0 | 5.6 | ||

| Coverage of Children | 58.3 | 100.0 | 31.6 | 31.6 | 44.0 | 44.0 | 9.7 | ||

| Q1 | 59.9 | 92.9 | 92.9 | 100.0 | 92.9 | 100.0 | 18.1 | ||

| Q2 | 41.7 | 81.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 42.3 | 49.9 | 5.5 | ||

| Q3 | 32.8 | 68.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.6 | ||

| Q4 | 22.5 | 51.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | ||

| Q5 | 20.0 | 40.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | ||

| Bottom 40% | 50.8 | 87.0 | 46.5 | 50.0 | 67.6 | 75.0 | 11.8 | ||

| Benefit incidence | |||||||||

| Q1 | 31.2 | 31.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 65.4 | 62.3 | 56.0 | ||

| Q2 | 24.0 | 23.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 34.6 | 37.7 | 21.9 | ||

| Q3 | 18.8 | 19.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.0 | ||

| Q4 | 13.5 | 14.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.8 | ||

| Q5 | 12.5 | 10.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 | ||

| Costsa | |||||||||

| Cost per child reached (TL) | 144.7 | 250.0 | 173.4 | 203.0 | 190.0 | 233.8 | 197.9 | ||

| Cost per person reached (TL) | 68.4 | 107.0 | 84.4 | 91.9 | 88.6 | 98.4 | 98.1 | ||

| Total additional monthly cost (Billion TL) | 1.93 | 5.72 | 1.25 | 1.47 | 1.91 | 2.35 | 0.44 | ||

| Total additional annual cost (% of GDP)b | 0.48 | 1.42 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.11 | ||

| Total additional annual cost (% of social protection expenditures)b | 4.06 | 12.02 | 2.63 | 3.08 | 4.02 | 4.95 | 0.92 | ||

| Cost effectiveness (per Billion TL)a | |||||||||

| % Point headcount poverty reduction (P0) | 1.2 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.1 | ||

| % Point poverty gap reduction (P1) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | ||

| % Point child poverty reduction | 2.3 | 2.3 | 5.9 | 5.0 | 4.4 | 3.6 | 3.9 | ||

aSince we use the 2018 HBS in our analysis, we moved the cash transfer values from 2020 to 2018 by using the average monthly CPI for 2018 for the poverty-reducing impact of the cash transfer scenarios. However, since these cash transfers are given in 2020, we use the cash transfer values in 2020 when calculating the total cost and cost-effectiveness of these cash transfers

bAs the latest information on GDP is for 2019, and the most recent information on social protection expenditures is for 2018, we use the 2019 GDP and the 2018 social protection expenditures values. However, using the CPI, we moved the total additional monthly cost from 2020 to the respective years of GDP and social protection expenditures

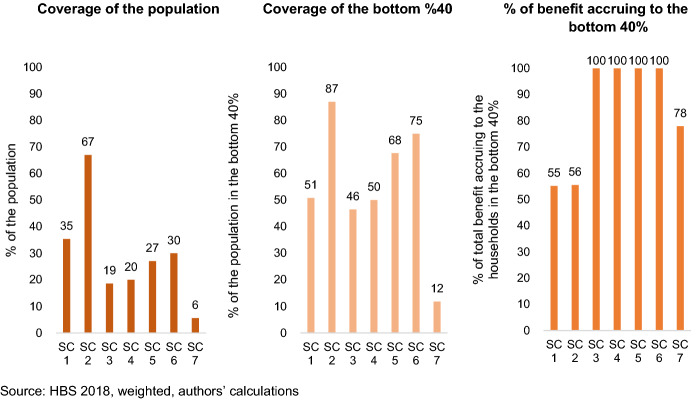

Impact on Child Poverty

After a mild shock, except for Scenario 2 (universal child grants for 0–17 year olds), none of the low transfer scenarios is able to achieve a return back to the baseline child poverty rate. However, most of the high transfer scenarios achieve poverty rates much lower than the baseline child poverty rate (i.e. poverty rate before shock) (See Fig. 3). While Scenario 2 (universal child grants for 0–17 year olds) is the scenario that achieves the highest reduction in child poverty rate whether a high or a low transfer is provided, the scenarios targeting the bottom 30% of households with or without children (Scenario 5 and Scenario 6) achieve getting close to the baseline child poverty rate—or even a lower rate, for high transfer, than the baseline child poverty rate as well (and they are less costly, as will be seen in the rest of the section). The scenarios targeting the bottom 20% of households with or without children (Scenario 3 and Scenario 4) have a similar but relatively lower impact on child poverty reduction compared to Scenario 5 and Scenario 6 for both transfer levels.

Fig. 3.

Child poverty reduction impact of different cash transfer scenarios present similar results with the general poverty trends.

Source: HBS 2018, weighted, authors’ calculations

In the occurrence of a severe shock, none of the cash transfer scenarios is enough to return back to the baseline child poverty rate whether in low transfer or high transfer cases, except for Scenario 2 (universal child grants for 0–17 year olds) in high transfer (See Fig. 3). After a severe shock child poverty increases to 24.7%, down from 15.4%. As in the occurrence of a mild shock, the universal child grant to 0–17 year old children scenario (Scenario 2) is the scenario that achieves the highest reduction in child poverty rates, both in the case of a high and low transfer. Universal child grant achieves a poverty rate much lower than the baseline child poverty rate in the case of high transfer (11.4%) and reduces child poverty to 16.5% with a low transfer. In the occurrence of a severe shock, again, the same scenarios as in the case of the mild shock are the most successful in poverty reduction after Scenario 2, which are Scenario 5 and Scenario 6 (targeting the bottom 30%).

The marginal transfer scenario (Scenario 7) that targets households who already receive social assistance income is the least effective scenario in terms of child poverty reduction for both transfer levels and in the occurrence of both shocks due to its low coverage. Targeting only the social assistance beneficiaries (Scenario 7) does not bring sufficient child poverty reduction. For instance, after a mild shock targeting only the social assistance beneficiaries with a low transfer (300 TL per household) leads to a poverty reduction of only 1.1 percentage points, and it leads to a poverty reduction of only 1.7 percentage points with a high transfer (500 TL per household).

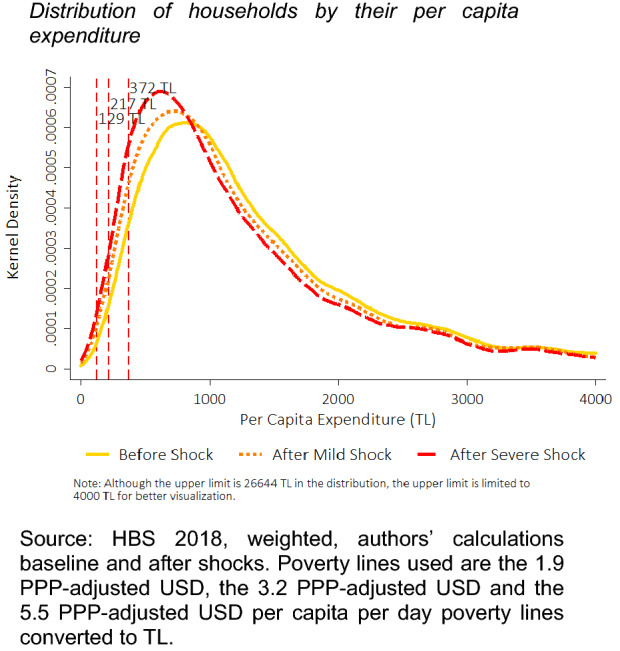

Coverage and Benefit Incidence (Targeting)

Among the cash transfer scenarios, coverage of the population and coverage of the bottom 40% are both highest in the universal child grant for 0–17 year olds scenario (Scenario 2), by far (See Fig. 4). Scenario 2 covers 67% of the population, 100% of the children, and 87% of the bottom 40%. After Scenario 2, the universal child grant for 0–5 year olds (Scenario 1) has the second-highest population coverage and the child population coverage (35% and 58%, respectively). But its coverage for the bottom 40% is relatively lower (51%). The scenarios targeting the bottom 20% and the 30% of households with or without children (Scenario 3, Scenario 4, Scenario 5, and Scenario 6) cover the population ranging between 19% and 30%, the child population ranging between 32% and 44%, and the bottom 40% ranging between 46% and 75%. Lastly, the marginal transfer scenario (Scenario 7) covers the smallest per cent of the population, the child population, and the bottom 40% with 6%, 10%, and 12%, respectively (See Tables 6 and 7).

Fig. 4.

Coverage and benefit incidence differ for different cash transfer scenarios.

Scenarios have varying levels of being pro-poor in targeting. Scenario 3, Scenario 4, Scenario 5, and Scenario 6 are the most pro-poor scenarios since they are already targeting the bottom 40% (See Fig. 4). In these scenarios, 100% of the benefit is accrued to the bottom 40% with no leakage. These scenarios are followed by Scenario 7, which targets households who already receive social assistance income. With this scenario, 78% of the total benefit is accrued to the bottom 40%. The universal child grant scenarios (Scenario 1 and Scenario 2) do not have as sharp targeting performance as the others, and that is natural due to their universality.22 With Scenario 1, 55.2% and with Scenario 2, 55.5% of the benefit goes to the bottom 40%.

Fiscal Costs and Cost-Effectiveness

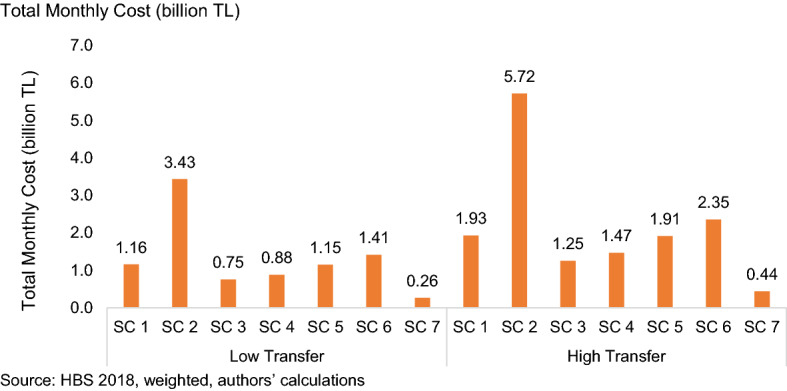

The universal child grant to all children younger than 18 years old (Scenario 2) is the costliest scenario (See Fig. 5). In the case of transferring 150 TL per child, this scenario costs 3.43 billion TL per month (or its total annual cost is 0.85% of 2019 GDP and 7.21% of social protection expenditures in 2018)23 and when transferring 250 TL per child, it costs 5.72 billion TL per month (or its total annual cost is 1.42% of GDP and 12.02% of social protection expenditures). This scenario is followed by the scenario targeting the bottom 30% of all households (Scenario 6) in terms of the total cost it generates. Scenario 6 costs 1.41 billion TL a month (or its total annual cost is 0.35% of GDP and 2.97% of social protection expenditures) when 300 TL per household is transferred, and it costs 2.35 billion TL a month (or its total annual cost is 0.58% of GDP and 4.95% of social protection expenditures) when 500 TL per household is transferred. The universal child grant for 0–17 year olds has the highest coverage (67% of the population) as well as the highest child poverty reduction impact (7.7 percentage points, with the low transfer in the case of a mild shock), but in terms of costs, it is the most expensive one. On the other hand, the latter scenario targeting all households in the bottom 30% (Scenario 6) also has a considerable child poverty reduction effect (4.4 percentage points, with the low transfer in the case of a mild shock) with a much lower cost (2.02 billion TL a month) than Scenario 2 even though it has a comparatively lower coverage (30% of the population).

Fig. 5.

The universal child grants for 0–17 year olds scenario (Scenario 2) is the most expensive scenario while the marginal transfer scenario (Scenario 7) is the least expensive one.

The least costly scenario is the marginal transfer scenario (Scenario 7), targeting households who already receive social assistance income, hence targeting a specific segment in the population and thus has low coverage. Scenario 7 costs 0.26 billion TL per month (or its total annual cost is 0.07% of GDP and 0.55% of social protection expenditures) when 300 TL is transferred per household who already receive social assistance as income and 0.44 billion TL per month (or its total annual cost is 0.11% of GDP and 0.92% of social protection expenditures) when 500 TL is transferred per social assistance receiving household. Yet this scenario is also the one with the lowest coverage and the lowest child poverty reduction impact.

Some scenarios lead to higher poverty reduction with the money spent, and are, therefore, more cost-effective. The scenarios that target the bottom 20 percent of households in terms of welfare, all or only the ones with children, turn out to be the most cost-effective programmes (in terms of reducing poverty or child poverty per TL spent). Specifically, Scenario 3 that provides 300 TL (in the low transfer case) or 500 TL (in the high transfer case) to all families with children in the bottom 20% of the distribution turns out to be the most cost-effective scenario in terms of poverty or child poverty reduced (in percentage points) per 1 billion TL spent for different levels of the shock.

In contrast, the transfer scenario (Scenario 7) that targets households who already receive social assistance income is not very effective in terms of poverty reduction due to its low coverage.

Conclusion

This study presented a methodology for estimating the poverty impact of COVID-19 through the labour market channel and estimated the possible household and child poverty impact of COVID-19 in Turkey using this methodology. The potential impact of COVID-19 on households through the labour channel is modelled by taking into account sector, employment status, and occupation type of each working individual and then reflecting the estimated decrease in labour income into a contraction in household expenditures.

As a result of the simulated labour income shock, monthly per capita expenditure decreases and subsequently, from a baseline rate of 9.1%, poverty increases to 12.3% after a mild shock, and to 15.3% after a severe shock. Child poverty is estimated to increase to 20.4% after a mild shock and to 24.7% after a severe shock, up from a baseline child poverty rate of 15.4%. Inequality also increases considerably after the shocks. Initially, the Gini index was calculated as 41.9 using households’ monthly per adult expenditure levels while it increases to 43.1 after a mild shock and to 44.0 after a severe shock.

Cash transfers are helpful in alleviating child poverty with differing impact levels and cost-effectiveness. After simulating the poverty impact of seven different hypothetical scenarios (and two benefit levels for each scenario), this paper finds that universal child grants for 0–17 years old children (Scenario 2) has the highest child poverty reduction impact overall while also being the most expensive scenario. On the other hand, the scenarios that target the bottom 20% of households in terms of welfare, and especially households with children among those, turn out to be the most cost-effective programmes in the simulation (in terms of reducing child poverty per TL spent).

Administratively, both a targeted and a universal approach could be applied relatively easily in Turkey. Turkey is advanced in terms of targeting for social assistance, using a combined database of rich administrative data and also providing household visits through district-level Social Assistance and Solidarity Foundation offices. Hence a targeted approach could be applied at first using the integrated social assistance database and will be less costly compared to a universal approach. While the universal child grants are overall more poverty-reducing, they are also a more expensive policy option. Given Turkey's experience and capacity in social assistance targeting, it may be better and fiscally more achievable to start with a targeted child grant and in the future, expand to a more universal grant.

The methodology developed in this paper is applicable in countries where surveys are collected in a similar format. The methodology note highlighted the differentiation of households by sector of employment and type of employment of all workers in the household, when generating the household level income shock. The income shock is then translated into an expenditure shock using income elasticities calculated in the baseline. The poverty, child poverty and inequality figures are re-calculated based on this shock to the income of the households. The cash transfer scenarios presented here are quite generic and, while proposed for the Turkish case, can also be applied in other country contexts with adjustments in order to assess the country-level distributional impact of COVID-19 and proposed cash transfer income support scenarios for households with children.

Acknowledgements

The material included in this article has been developed from the report “Estimating the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Child Poverty in Turkey and Social Protection Policy Options for Better Coverage of Children” that was prepared for UNICEF Turkey Country Office by Development Analytics, not yet publicly available online (Aran et al. 2021). This study does not reflect the official views of UNICEF, and any errors in the text remain that of the authors.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

We preferred to use an expenditure-based poverty measurement approach for a number of reasons. Our choice of expenditure-based poverty measurement is aligned with the literature suggesting that expenditures are more likely to be used in poverty measurement in developing countries as they tend to be measured more accurately than income (Haughton and Khandker 2009). While Turkey is an upper middle-income country, it has a high incidence of informal employment (30.6% in 2020), increasing the likelihood of underreporting of income. Turkey also has a significant employment rate in the agriculture sector (17.4% in 2020), increasing the likelihood of subsistence agriculture. In this respect, to better predict the welfare of the households, we preferred using expenditure-based poverty. We also wanted to benchmark our results using the baseline poverty figure as reported by the World Bank, which is expenditure-based reported using Household Budget Survey.

Other surveys collected at the national level, such as the Survey of Income and Living Conditions (SILC), and Labour Force Survey (LFS) were also examined by the authors. However, while SILC and LFS provide detailed information on income and employment of household members, they do not include information on expenditures, and hence was not found to be useful for modelling a shock through the labour market on household expenditures and hence expenditure-based poverty in the country.

Since the HBS collected by TURKSTAT provides information on income subgroups of household members, we calculate labour income by adding up the income subgroups related to employment. Therefore, this methodology can be applied by using this total income, or if the information about income subgroups is also collected in the country of study, these additional variables can also be requested and applied in the same way as in this study.

The periodic report of TURKSTAT for June 2020 covers 18th–30th weeks of 2020 in May, June and July. (TURKSTAT, June, 2020).

World Bank poverty lines of 5.5 USD as upper-middle-income country line, 3.2 USD as lower-middle-income country line, and 1.9 USD as extreme poverty line are used for calculating poverty rates.

The rates provided by the TURKSTAT on the per cent change in the number of employed in June 2020 compared to June 2019 are as follows by each sector: Agriculture − 5.1%, Industry − 5.7%, Construction − 5.6% and Services − 8.7%. And the rates by occupation type are as follows: Managers − 2.0%, Professionals 4.5%, Technicians and Associate Professionals − 8.6%, Clerical Support Workers − 2.7%, Service and Sales Workers − 12.9%, Skilled Agricultural, Forestry and Fishery Workers − 5.4%, Craft and Related Trades Workers − 10.0%, Plant and Machine Operators and Assemblers − 8.6%, Elementary Occupations − 8.0%. Lastly, the rates are as follows by employment status: Regular or casual wage employee − 5.4, Employer − 10.2%, Self-Employed − 8.2% and Unpaid Family Worker − 13.2%. Source for TURKSTAT rates: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Isgucu-Istatistikleri-Haziran-2020-33790#:~:text=%C4%B0%C5%9Fg%C3%BCc%C3%BC%202020%20y%C4%B1l%C4%B1%20Haziran%20d%C3%B6neminde,%49%2C0%20olarak%20ger%C3%A7ekle%C5%9Fti

These assigned values are compatible with the study of Demir Seker et al. (2020) published in June, which estimates vulnerability of jobs to COVID-19 in Turkey.

In the 2018 HBS, the income variables used in estimating the total individual labour income are positive for unpaid family workers as well. And since they have labour income, we assume that unpaid family workers can be affected as well by the labour income shock.

For those individuals who are working and who do not have a reported income in the data, income is imputed based on a regression model.

The variable related to employment status in the 2018 HBS is asked for the survey month. Therefore, the impact of the income shock is valid for the individuals who are working in the survey month.

There is only 1 person whose labour income is less than 0 in the data, and her baseline labour income is changed to 0.

According to the HBS 2018, none of the members of households in 21.8% of households (or 2639 out of 11,828 households in the sample) in Turkey is working.

In the 2018 HBS, while the expenditure variable is monthly, income variables used in the calculation of labour income is annual. Therefore, the baseline household labour income is turned into monthly household income by dividing it into 12 while calculating the income elasticities.

We checked the robustness of the model with adding variables such as presence of children in the household, house ownership and number of working adults in the household. The coefficient changed only slightly, i.e. at the third decimal point.

Poverty lines for Turkey were obtained from the World Bank’s PovcalNet, which calculates the poverty lines in TL using international poverty lines and corrects for P.P.P. The poverty lines’ corresponding TL amounts as reported in PovcalNet were 129 TL, 217 TL and 372 TL respectively per month per capita for 1.9 USD, 3.2 USD and 5.5 USD lines and were taken as such in our model (retrieved from http://iresearch.worldbank.org/PovcalNet/povOnDemand.aspx on August 4, 2020).

The analysis presented here provides results on the immediate impact of COVID related income losses and poverty alleviating effect of cash transfers provided in the short run. In Turkey, targeting of social assistance is largely done using information on asset ownership among other variables including income and employment status. Asset ownership is more sticky and will not change as quickly as income. To reflect this stickiness while targeting poor households and also being in line with targeting in the Turkish social assistance system, the targeting takes into account baseline expenditure levels which are a better reflection of households’ baseline asset ownership than aftershock expenditure levels.

Cash transfers are relatively small compared to average monthly household income loss. In case of a high transfer per household, the transfer amount of 500 TL for instance, corresponds to 54.3% of the average monthly household income loss of 921 TL in the case of a mild shock and 29.9% of the average monthly household income loss of 1673 TL in the case of a severe shock. Since it is a comparatively small amount, we assumed it to be consumed fully rather than saved.

These cash transfer values are for the year 2020. Since we use the 2018 HBS in our analysis, to see the poverty and inequality impact of the transfers, we moved the cash transfer values from 2020 to 2018 using CPI as follows:

to calculate their impact on poverty. The CPI values are taken from TURKSTAT. While CPI for July 2020 is 468.56, the average monthly CPI for the year 2018 equals 363.13. Totals costs or cost-effectiveness measures are reported for 2020 values of the transfers.

In the scenarios targeting the bottom 20% (or the bottom 30%), the population is divided into 5 categories based on household’s monthly per capita expenditure in the baseline (i.e. before shocks) and the bottom 20% (or the bottom 30%) corresponds to the poorest 20% of the population (or the poorest 30% of the population). This categorization stays the same whether there is an income shock or there is a cash transfer to the household since it is based on the baseline expenditure levels.

Social assistance income in the last scenario is described in the 2018 HBS as “benefits from social assistance fund and other family allowances”. Hence the targeted households are those who report receiving this type of income in the previous year.

Since we use the 2018 HBS in our analysis, the population in 2018 is used in the calculations. In 2018, total population is reported as 82.0 million and the child population between the ages of 0–17 is reported as 22.9 million in TURKSTAT’S website (Source: http://www.tuik.gov.tr/PreIstatistikTablo.do?istab_id=1588 and http://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/medas/?kn=206&locale=tr).

While in most developing countries, a universal child grant tends to be automatically progressive, given the household demographics and distribution across quintiles, in Turkey it seems a universal child grant (as in Scenario 1 and Scenario 2) would only reach 31.2% and 31.6% of the bottom quintile (20%) of the population, respectively, which is only mildly progressive. (See Table 6 and Table 7 for a detailed Benefit Incidence Analysis for each scenario.).

GDP 2019 and Social Protection Expenditures 2018 (which are the latest statistics reported) are obtained from TURKSTAT website (http://www.tuik.gov.tr/PreIstatistikTablo.do?istab_id=2506, http://www.tuik.gov.tr/PreHaberBultenleri.do?id=30625). Social protection expenditures provided by TURKSTAT are inclusive of pensions.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Meltem A. Aran, Email: meltem.aran@developmentanalytics.org

Nazli Aktakke, Email: nazli.aktakke@developmentanalytics.org.

Zehra Sena Kibar, Email: sena.kibar@developmentanalytics.org.

Emre Üçkardeşler, Email: euckardesler@unicef.org.

References

- Almeida, V., S. Barrios, M. Christl, S. De Poli, A. Tumino, and W. van der Wielen. 2020. Households’ income and the cushioning effect of fiscal policy measures during the Great Lockdown, JRC Working Papers No. 2020-06.

- Aran MA, Aktakke N, Çolak H, Kibar S. Estimating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child poverty in Turkey and social protection policy options for better coverage of children. Ankara: UNICEF; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Baulch, B., R. Botha, and K. Pauw. 2020. The short-term impacts of COVID-19 on the Malawian economy, 2020–2021: A SAM multiplier modeling analysis. MaSSP Report November 2020. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Brewer, M., and I. Tasseva. 2020. Did the UK policy response to Covid-19 protect household incomes? EUROMOD Working Paper 12/20. Essex, UK: Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bronka, P., D. Collado, and M. Richiardi. 2020. The Covid-19 crisis response helps the poor: The distributional and budgetary consequences of the UK lock-down, EUROMOD Working Papers Series No. EM 11/20.

- Bruckmeier, K., A. Peichl, M. Popp, J. Wiemers, and T. Wollmershäuser. 2020. Distributional effects of macroeconomic shocks in real-time: A novel method applied to the Covid-19 crisis in Germany, IAB-Discussion Paper, 36/2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brum M, De Rosa M. Too little but not too late: nowcasting poverty and cash transfers’ incidence during COVID-19’s crisis. World Development. 2021;140:105227. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereda F, Rubiao RM, Sousa LD. COVID-19, labor market shocks, poverty in Brazil: A microsimulation analysis. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chitiga, M., M. Henseler, R. Mabugu, and H. Maisonnave. 2020. How COVID-19 pandemic worsens the economic situation of women in South Africa. Working Papers hal-02976171, HAL. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/EDEHN/hal-02976171v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chitiga-Mabugu M, Henseler M, Mabugu R, Maisonnave H. Economic and distributional impact of COVID-19: Evidence from macro-micro modelling of the South African economy. South African Journal of Economic. 2020;89:82–94. doi: 10.1111/saje.12275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta J, Pico J. The gendered poverty effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in Colombia. The European Journal of Development Research. 2020;32(5):1558–1591. doi: 10.1057/s41287-020-00328-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayioğlu M, Şeker S. Social policy and the dynamics of early childhood poverty in Turkey. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities. 2016;17(4):540–557. doi: 10.1080/19452829.2016.1225700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demir Seker, S., S.E. Nas Ozen, and A. Acar Erdogan. 2020. Jobs at risk in Turkey: Identifying the impact of COVID-19. Social Protection and Jobs Discussion Paper, No: 2004. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/553971597208649040/Jobs-at-Risk-in-Turkey-Identifying-the-Impact-of-COVID-19.

- Diao, X., and K. Mahrt. 2020. Assessing the impacts of COVID-19 on household incomes and poverty in Myanmar. A microsimulation approach. Myanmar Strategy Support Program Working Paper 02. Yangon: International Food Policy Research Institute. https://www.ifpri.org/publication/assessing-impacts-covid-19-household-incomes-and-poverty-myanmar-microsimulation.

- Doorley, K., C. Keane, A. McTague, S. O’Malley, M. Regan, B. Roantree, and D. Tuda. 2020. Distributional impact of tax and welfare policies: COVID-related policies and Budget 2021. Quarterly Economic Commentary 47.

- Dzigbede K, Pathak R. COVID-19 economic shocks and fiscal policy options for Ghana. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting and Financial Management. 2020;32(5):903. doi: 10.1108/JPBAFM-07-2020-0127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Escalante, L., and H. Maisonnave. 2021. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women’s welfare and domestic burdens in Bolivia. HAL. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03118060/document.

- EY. 2020. Turkey introduces Economic Stability Shield Package to reduce the impact of COVID-19. https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/Turkey_introduces_Economic_Stability_Shield_Package_to_reduce_the_impact_of_COVID-19/$FILE/2020G_001308-20Gbl_Turkey%20-%20Economic%20Stability%20Shield%20Package%20re%20COVID-19.pdf.

- Figari, F., and C.V. Fiorio. 2020. Welfare resilience in the immediate aftermath of the covid-19 outbreak in Italy. EUROMOD Working Papers Series No. EM 06/20.

- Genoni, M.E., A.I. Khan, N. Krishnan, N. Palaniswamy, and W. Raza. 2020. Losing livelihoods: The labor market impacts of COVID-19 in Bangladesh. Washington, DC.: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/34449/Losing-Livelihoods-The-Labor-Market-Impacts-of-COVID-19-in-Bangladesh.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Gentilini, U., M.B.A. Almenfi, P. Dale, R.J. Palacios, H. Natarajan, G.A. Galicia Rabadan, and I.V. Santos. 2020. Social protection and jobs responses to COVID-19: A real-time review of country measures. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/295321600473897712/Social-Protection-and-Jobs-Responses-to-COVID-19-A-Real-Time-Review-of-Country-Measures-September-18-2020. Accessed 18 Sept 2020.

- Giannarelli, L., L. Wheaton, and G. Acs. 2020a. 2020 poverty projections: Initial US Policy Response to the COVID-19 pandemic’s economic effects is projected to blunt the rise in annual poverty. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102521/2020-poverty-projections.pdf.

- Giannarelli, L., L. Wheaton, K. Werner, I. Dehry, and G. Acs. 2020b. 2020 poverty projections: Assessing three pandemic-aid policies. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102605/2020-poverty-projections-assessing-three-pandemic-aid-policies-projections-of-heroes-act-policies-by-race-and-by-state-august-through-december.pdf.

- Gürsel, Ş., and M.C. Şahin. 2020. Korona Salgınının İşgücü Piyasasına Etkisi: Öncü Göstergeler Ne Söylüyor? BETAM Araştırma Notu, 20/250. İstanbul: BETAM. https://betam.bahcesehir.edu.tr/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ArastirmaNotu250-1.pdf.

- Haughton, Jonathan, Shahidur R. Khandker. 2009. Handbook on poverty and inequality. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11985. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- I.L.O. 2020a. I.L.O. Social protection monitor.https://www.social-protection.org/gimi/ShowWiki.action?id=3417. Accessed 21 Sept 2020.

- I.L.O. 2020b. I.L.O. Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work, 2 nd edn. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_740877.pdf. Accessed Apr 2020.

- Jara, H.X., L. Montesdeoca, and I. Tasseva. 2021. The role of automatic stabilizers and emergency tax-benefit policies during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ecuador, No. 2021/4, WIDER Working Paper. https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/229405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kneewshaw, J., D. Collado, N. Framarin, K. Gasior, H.X. Jara Tamayo, C. Leventi, K. Manios, D. Popova, and I. Iva Tasseva. 2021.Baseline results from the EU28 EUROMOD: 2017–2020, EUROMOD Working Paper EM01/21, Colchester: University of Essex. https://www.euromod.ac.uk/publications/baseline-results-eu28-euromod-2017-2020.

- Kyyrä T, Pirttilä J, Ravaska T. The Corona crisis and household income: The case of a generous welfare state. Helsinki: VATT Institute for Economic Research; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., Y. Vidyattama, H. Anh, R. Miranti, and D. Sologon. 2020. The Impact of COVID-19 and Policy Responses on Australian Income Distribution and Poverty, Papers 2009.04037, arXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.04037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lustig, N., V. Martinez Pabon, F. Sanz, and S.D. Younger. 2020a. The impact of Covid-19 lockdowns and expanded social assistance on inequality, poverty and mobility in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico. Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) Covid Economics: Vetted and Real-Time Papers, 46.

- Lustig, N., G. Neidhöfer, and M. Tommasi. 2020b. Short and long-run distributional impacts of COVID-19 in Latin America, No. 2013. Tulane University, Department of Economics. http://repec.tulane.edu/RePEc/pdf/tul2013.pdf.

- Ministry of Family and Social Services (MoFSS). 2021. Announcement on Social Assistance Program during the full lock-down. https://www.aile.gov.tr/haberler/bakan-yanik-2-milyonun-uzerinde-ihtiyac-sahibi-haneye-tam-kapanma-sosyal-yardim-programi-ile-1100-tl-tutarinda-nakdi-destek-saglayacagiz/.

- Nafula, N., D. Kyalo, B. Munga, and R. Ngugi. 2020. Poverty and distributional effects of COVID-19 on households in Kenya, AERC Working Paper. Nairobi:African Economic Research Consortium. http://publication.aercafricalibrary.org/bitstream/handle/123456789/1266/03_Kenya-Covid-19-Nov-29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Nechifor V., O. Boysen, E. Ferrari, K. Hailu, and M. Beshir. 2020. Socioeconomic COVID-19 impacts and recovery in Ethiopia. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/361363475.pdf.

- Palomino JC, Rodríguez JG, Sebastian R. Wage inequality and poverty effects of lockdown and social distancing in Europe. Covid Economics. 2020;25:186–229. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2020.103564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]