Abstract

Study Design:

The Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic has disrupted oral and maxillofacial (OMF) surgeons’ practice globally. We implemented a cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey among the OMF surgeons of India.

Objective:

The objectives of the study were (1) gathering data among the maxillofacial surgeons in terms of their occupational exposure and access to adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and (2) to estimate how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the practice of OMF surgeons in India.

Materials and Methods:

Complete responses of 178 OMF surgeons were included in the study. Descriptive and analytic statistics were computed. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Binary logistic regression models were created to assess the predictors of the impact of the COVID-19.

Results:

Out of the 178 respondents of the study, most (37.1%) were following their hospital's guidelines. Most had access to adequate PPE (89.9%), whereas 93.8% had COVID-19 testing available. One hundred and thirty-three (74.7%) surgeons were involved in teleconsultation. Ninety-two (51.7%) and 166 (93.3%) were involved in elective surgery and emergency surgeries, respectively. Median outpatient department cases and number of surgeries done per week reduced by 73.9% and 66.7% (P < 0.001), respectively. Most surgeons (86%) experienced that cost of treatment had increased during the COVID. Over 75% were afraid to get infected with COVID, whereas 44.9% were anxious to lose the income. More than 56% of the OMF surgeons reported a fall in income and 94% reported decreased productivity in academic research. Most surgeons (93.8%) believed that COVID had a positive impact on human behavior in terms of hand hygiene.

Conclusion:

The impact of COVID-19 among OMF surgeons has adversely affected clinical practice, personal lives, and academic productivity and has catalyzed an exponential increase of telemedicine. Future surveys should capture the long-term impact of COVID-19.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease-19, impact, oral and maxillofacial, pandemic, practice, surgeons

INTRODUCTION

The outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV2) has crippled the health-care systems around the world. The disease that it caused was officially announced as coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) on the February 11, 2020, by the World Health Organization (WHO).[1] This disease which originated from bats and pangolins from Wuhan, China, manifests as symptoms of fever, dry cough, and dyspnea. Extrapulmonary, atypical symptoms can be seen in four-fifth, which include anosmia/hyposmia, dysgeusia, and diarrhea to name a few. The role of asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers was highlighted in an Italian village by conducting blanket testing.[2] According to the WHO weekly update on the pandemic, as of November 30, 2020, more than 62 million cases and 1.4 million deaths were reported worldwide. Countries that recorded the most cases over the past 3 weeks were India, USA, and France.[3]

The virus is predominantly seen in the secretions of the nasopharynx and saliva.[4] The proximity to the oral cavity along with the fact that oral and maxillofacial (OMF) procedures involve an exorbitant amount of aerosol production puts the OMF surgeons at the greatest risk of infection among the health-care workers’ spectrum.[5] Following occupational exposure to the virus, many health workers may develop no symptoms and unintentionally act as a source of contagion. OMF surgeons around the world have resorted to safety measures to curb the spread of nosocomial infections by canceing elective surgeries and aerosol-generating procedures along with the use of personal protective equipment (PPE). Guidelines for the safe practice of OMF surgery have been proposed by various national and international OMF organizations. Despite all these guidelines and safety norms, a drastic fall in the number of patients in the OMF outpatient department (OPD) and surgeries has been witnessed. Various aspects of COVID-19 such as epidemiology, microbiology, and care of the patients affected with COVID-19 have been published recently.[6] However, the literature evaluating its impact on the OMF surgeons’ practice is deficient.

This survey was conducted with an aim of gathering data on the current state of affairs among the maxillofacial surgeons in India during the pandemic in terms of their occupational exposure and access to PPE and compare it with the available global data. The purpose of this study was to estimate how the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted and changed the practice of maxillofacial surgery in different regions of India in terms of change in the number of OPD, surgeries performed, and academic and financial impact.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To achieve the above goal, we executed a cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey among the OMF surgeons of India. The study was conducted after prior ethical approval from the bioethics cell of our institute IEC Code-2020–261-IP-EXP-28.

We used both convenience and snowball sampling methods. The OMF surgeons who have got their postgraduate degrees and are practicing in India were included in the study. Those who are not practicing in India or still under training were excluded from the study.

A consent form was filled by all the participants before commencing the questionnaire, giving an overview of the survey and agreement to the use of data for scientific research. A set of 35 questions were to be answered to complete the survey which included demographic data, patient care and availability of infrastructure to support patient care during the pandemic, impact on research and training, and financial impact.

Six faculty members validated the questionnaire contents by rating the questionnaire for simplicity, clarity, ambiguity, and its relevance on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1was worst and 5 was best. There was a good score observed (observed score regarding maximum score expressed in %) for each of the measurements, i.e., simplicity (89%), clarity (81%), free of ambiguity (78%), and relevance (84%). We assessed the internal consistency of the questionnaire using Cronbach's alpha (0.883) which was also showing a good correlation between the questions, with maximum questions showing correlation with each other.

The questionnaire was sent to the registered OMF surgeons of India by using various social media platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp, and e-mails using the SurveyMonkey platform. We conducted the survey after the upliftment of lockdown in August and September 2020 and the duration of the survey was 1 month.

All the participants were explained about the study, and informed consent was obtained. Only those who agreed to take part in the study could take the survey. To avoid duplication of submission, we kept e-mail ID as a mandatory part of the questionnaire.

The responses of participants in the pilot study and incomplete responses were not included in the study. The data thus collected was then compiled in Microsoft Excel.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of the continuous variable are presented as mean ± standard deviation/median (interquartile range) while categorical data in frequency and percentage as appropriate. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the medians between pre COVID and during COVID, whereas Chi-square test/Fisher's exact test was used to compare the proportions between the groups. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to assess the predictors of impacts of the COVID. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical package for social sciences version 23 (SPSS-23, IBM, Chicago, USA), was used for the data analysis.

RESULTS

A total of 210 registered OMF surgeons practicing in India took part in the survey. Complete response was obtained from 178 OMF surgeons and included in the data analysis. In total, around two-third of OMF surgeons were male (n = 131/178, 73.6%). About 58.5% of the surgeons were in the age group of 31–40 years, followed by 24.7% and 10.7% in the age group of <30 years and 41–50 years, respectively, and only 6.1% were in the age group of >50 years.

From the total study participants, 28.1% (n = 50) belonged to Uttar Pradesh, 26.4% (n = 47) from western states, 21.3% (n = 38) belonged to South India, 5.6% (n = 10) belonged to northeastern states, and the rest (n = 33, 18.5%) belonged to other areas (central and Northern) of India. Most of the OMF surgeons (n = 154, 86.5%) were working in the urban area. About 26.4% of OMF surgeons were private practitioners, whereas 24.2% and 23.6% were consultant and faculty, respectively. More than half of the respondents (n = 98, 55.1%) were working on salary, whereas the rest (n = 80, 44.9%) were self-employed. Most of the OMF surgeons were working in private hospital/nursing home (n = 75, 42.1%), followed by working in government institute (n = 62, 34.8%) and private practice (n = 41, 23%) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of demographic variables (n=178)

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| <30 | 44 (24.7) |

| 31-40 | 104 (58.5) |

| 41-50 | 19 (10.7) |

| 51-60 | 7 (3.9) |

| >60 | 4 (2.2) |

| Male, sex | 131 (73.6) |

| Area of practice | |

| Rural | 24 (13.5) |

| Urban | 154 (86.5) |

| Designation | |

| Faculty | 42 (23.6) |

| Consultant | 43 (24.2) |

| Practitioner | 47 (26.4) |

| Senior resident | 27 (15.2) |

| Others | 19 (10.7) |

| Type of employment | |

| Self-employed | 80 (44.9) |

| Salaried | 98 (55.1) |

| Type of practitioner | |

| Private practitioner | 41 (23.0) |

| Private institutes/nursing home | 75 (42.1) |

| Government institute | 62 (34.8) |

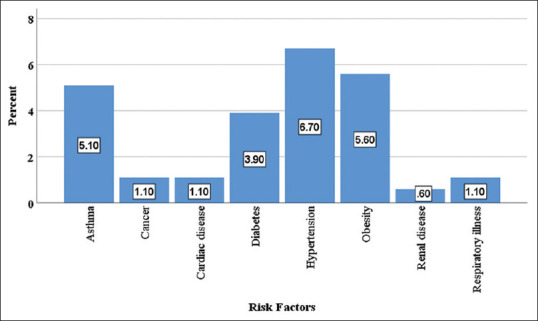

In our survey, 17.4% (n = 31) of OMF surgeons had some kind of medical ailments, 6.7% surgeons had hypertension followed by 5.6% had obesity, 5.1% had asthma, 3.9% had diabetes, 1.1% each had cancer, cardiac disease, and respiratory illness, whereas 0.6% had renal disease [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Distribution of the risk factors among the study participants

Guideline being followed for prevention of coronavirus disease transmission

Out of the 178 respondents of the study OMF surgeons, 37.1% (n = 66) were following their hospital's own guidelines, followed by 25.8% (n = 46) WHO guidelines, 24.7% (n = 44) AOMSI guideline, 10.1 (n = 18) AOCMF, whereas 2.2% (n = 4) were following other guidelines. In rural and urban, the highest number of hospitals followed their own guideline (45.8% vs. 35.7%), WHO guideline (29.2% vs. 25.3%), AOMSI (12.5% vs. 26.6%), AOCMF (4.2% vs. 11%), and others (8.3% vs. 1.3%) although no overall association was obtained between the type of guidelines being followed and area of the hospital (P = 0.095). Similarly, maximum hospital belonged to southern states those followed their own guidelines (25.8%), WHO guideline (western states and UP each 30.4%), AOMSI (31.8% by UP), and AOCMF (33.3% by western), whereas other guidelines were maximum followed in the central and northern states (75%), although no overall association was noted between the type of guidelines and regions of the hospitals (P = 0.511) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Hospital guideline, preparation, and hospital services during coronavirus disease (n=178)

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Which guideline | |

| Hospital | 66 (37.1) |

| WHO | 46 (25.8) |

| AOMSI | 44 (24.7) |

| AOCMF | 18 (10.1) |

| Others | 4 (2.2) |

| Access adequate PPE | 160 (89.9) |

| COVID testing available | 167 (93.8) |

| Teleconsultation (yes) | 133 (74.7) |

| Can telecommunication replace physical | 44 (24.7) |

| Elective surgeries during COVID | 92 (51.7) |

| Emergency surgeries during COVID | 166 (93.3) |

COVID: Coronavirus disease, WHO: World Health Organization, AOMSI: Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons of India, AOCMF: Association of Craniomaxillofacial Trauma, PPE: Personal protective equipment

Availability of personal protective equipment, teleconsultations, and elective surgeries

In our survey, most of the respondents had access to adequate PPE (n = 160, 89.9%). There was no statistically significant difference noted in the availability of the PPE between rural and urban areas (83.3% vs. 90.9%, P = 0.273) and between government, private, and both types of institutions (87.1% vs. 95.1% vs. 89.3%, P = 0.436).

Whereas 93.8% (n = 167) had COVID-19 testing available, 74.7% (n = 133) were involved in teleconsultation, 51.7% (n = 92) and 93.3% (n = 166) were involved in elective surgery and emergency surgeries, respectively, during COVID. About 24.7% (n = 44) were willing to replace physical OPD with teleconsultations [Table 2].

Impact on outpatient departments and surgeries

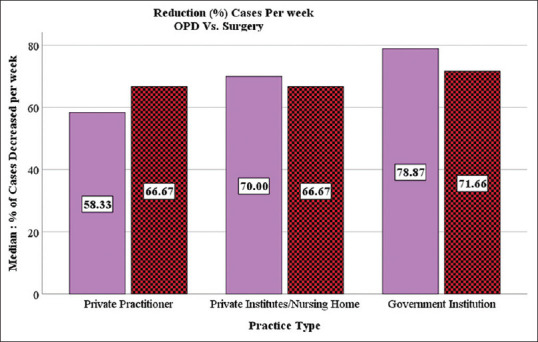

The number of OPD cases per week and number of surgery done per week between pre-COVID time and during the COVID time are presented in Table 3. The result showed that median OPD cases were decreased from 58 to 15 per week (73.9%, P < 0.001). Similarly, the median number of surgery done per week was decreased from 6 to 2 per week (66.7%, P < 0.001) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Impact of the coronavirus disease on outpatient department and surgery cases (n=178)

| Variable’s | Median | Q1 | Q3 | Decrease in percentage | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of OPD cases/weeks | |||||

| Pre-COVID | 58 | 20 | 150 | 73.90 | <0.001 |

| During COVID | 15 | 7 | 35 | ||

| Number of surgery/weeks | |||||

| Pre-COVID | 6 | 3 | 10 | 66.67 | <0.001 |

| During COVID | 2 | 1 | 4 |

*P<0.05 significant. Wilcoxon signed-rank test used to compare the cases between pre and during COVID. OPD: Outpatient department, COVID: Coronavirus disease

There was no statistically significant difference observed in the median reduction (%) in OPD and surgery cases (73.3% vs. 66.7%, P = 0.694). Similarly, there was no significant association obtained between the type of practice and percentage reduction in OPD cases (P < 0.001) as well as surgery cases per week (P = 0.042). There was a significant reduction in OPD cases between each of the pairs of three types of practitioners (each P < 0.05), whereas in surgery cases, the difference was statistically significant between government and private institutions/nursing homes only (P < 0.05) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Adjacent bar graph showing the reduction (%) in OPD and surgery cases between pre and during corona virus disease time

The financial burden of performing the procedure

The result showed that 86% (n = 153) of surgeons experienced that cost of treatment had increased during the COVID. Out of these, 38.9% experienced 1%–25% increment, 36.5% by 26%–50%, 8.4% by 51%–75%, and 2.2% had increased burden by 76%–100%.

From the total study surgeons, 75.3% (n = 134) were afraid to get infected with COVID, whereas 44.9% (n = 80) were feeling the anxiety of losing the income [Table 4].

Table 4.

Impact of coronavirus disease on financial burden (n=178)

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Financial burden increased (yes) | 153 (86.0) |

| If increased how much (%) | |

| 1-25 | 69 (38.9) |

| 26-50 | 65 (36.5) |

| 51-75 | 15 (8.4) |

| 76-100 | 4 (2.2) |

| Afraid to infect with COVID | 134 (75.3) |

| Feeling anxiety to losing the income | 80 (44.9) |

| Reported decreased in income (%) | |

| ≤20 | 12 (6.7) |

| 21-60 | 69 (38.8) |

| >60 | 20 (11.2) |

| Income either unchanged or increased | 77 (43.3) |

| Doctors on salary | 99 (56.7) |

| Reported reduction in salary | 29 (16.3) |

| Self-employed doctors | 79 (43.2) |

| Self-employed doctors reported loss of income | 72 (40.4) |

COVID: Coronavirus disease

Financial impact

Out of total (n = 178), most of the OMF surgeons (n = 101, 56.7%) reported decreased income. Nearly 6.7% (n = 12) surgeons reported decreased income by ≤20%, 38.8% (n = 69) reported decreased income by 21%–60%, 11.2% (n = 20) reported income loss of >60%, whereas (n = 77, 43.3%) OMF surgeons reported no change in income during COVID as compared to pre COVID.

There were 98/178 (55.1%) surgeons on salary, out of them, 71/98 (72.4%) had no impact on income, and the rest (28.6%, 28/98) reported reduction or loss of income through salary. Similarly, from the 80 (44.9%) self-employed surgeons, 74/80 (92.5%) had reported a loss in income. 39/41 (95.1%) private practitioners, 58/75 (77.3%) both types of practitioners, and 4/62 (6.5%) government employees reported a loss of income. There was a significant association observed between loss of income and type of practices (P < 0.001) [Table 4].

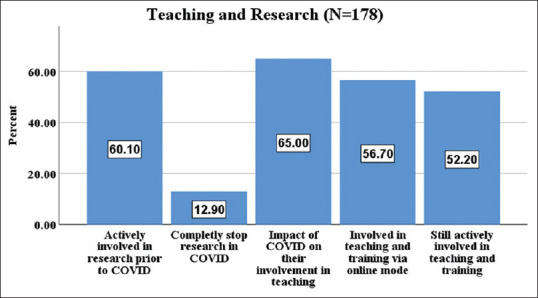

Impact on teaching and training

Out of the total, n = 93 (52.2%) OMF surgeons were actively involved in teaching and training, whereas 65% (n = 117) reported the impact of COVID on their involvement in teaching and training. About 56.7% (n = 101) told that they are involved in teaching and training via online mode. Nearly 60.1% (n = 107) told that they were actively involved in research prior to COVID-19. Out of the total, 94 (52.8%) reported decreased productivity in academic research, 20 (11.2%) reported increased productivity, 12.9 (n = 23) completely stopped, whereas 23% (n = 41) reported no change in their academic activity [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Bar graph showing the status of the teaching and research during coronavirus disease-19 pandemic

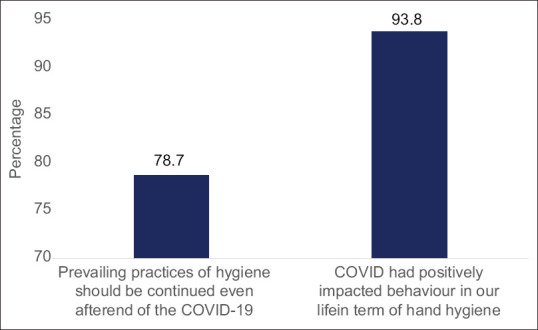

The good impact of the coronavirus disease on human behavior

One hundred and forty (78.7%) think that prevailing practices of hygiene should be continued even after the end of the COVID. One hundred and sixty-seven (93.8%) think that COVID had positively impacted behavior in our life in terms of hand hygiene [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Good impact of the coronavirus disease-19 on human behaviors

DISCUSSION

COVID-19 is a disease caused by the Cov-2 virus which belongs to the genus Betacoronavirus.[7] Viruses of the Betacoronavirus genus have a specific tropism for the respiratory system, causing mild flu-like illnesses or severe illnesses such as fatal pneumonia in humans and vertebrates.[8] The incubation period of COVID-19 ranges from 2 to 14 days (mean of 5 or 6 days).[9]

This virus predominantly spreads directly from the infected patient's cough and/or sneeze, then inhaling droplets and aerosol containing the virus, as the nasopharynx and nose are the major reservoirs of the virus.[10] Contact transmissions via virus-contaminated surfaces and then touching the oral, nasal, or conjunctival mucous membranes might cause infection.[7] Thus, practitioners like maxillofacial surgeons, dentists, and otorhinolaryngologists are at a much higher risk of being exposed to and infected by COVID-19.[10]

The Government of India confirmed India's first case of COVID-19 on January 30, 2020, in the state of Kerala. Since then, there has been an exponential increase in infections. The nationwide lockdown was announced on March 24, 2020, which continued in its fifth phase until June 30, 2020, with some relaxations in no infection areas[11] and promoting social distancing, hand sanitization, use of facial masks, the establishment of new dedicated COVID-19 hospitals, contact tracing, and quarantine facilities became the new normal.[12]

The disease has not only contributed to the immense loss of lives but also has secondarily brought economic unrest around the globe. The government's directives to stop routine OPDs paralyzed health-care delivery in the country during the lockdown and left all the patients in a poignant situation.

The disease has not only contributed to the immense loss of lives but also has secondarily brought economic unrest around the globe. The government's directives to stop routine OPDs paralyzed health-care delivery in the country during the lockdown and left all the patients in a poignant situation. All elective surgical procedures were canceled and rescheduled until the protocols to limit occupational exposure have been identified. Surgeons working in the OMF field were no exception to this.[13]

The purpose of this study was to (1) gathering data on the current state of affairs among the maxillofacial surgeons in India during the pandemic, in terms of their occupational exposure and access to PPE and (2) to estimate how the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted and changed the practice of maxillofacial surgeons in India considering number of OPD, surgeries performed, and academic and financial impact.

The following outcomes were studied:

To what guideline do surgeons adhere?

A worldwide survey conducted by CMF surgeons in the Netherlands pointed out that there is no single guideline followed by most surgeons all around the globe. Individual hospital guidelines were used in Europe, whereas in North America, a mix of guidelines was used from their hospital, local governments, and national associations. Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and South Africa used the guidelines of the WHO and in the Middle East, AO CMF guidelines were preferred. However, differences were not significant.[14] Most of the surgeons in our study followed their hospital's own guidelines and the rest followed WHO, AOMSI, and AO CMF guidelines, and regional differences with the guidelines followed were not significant. It is of paramount importance that international societies like AO CMF continue to disseminate the updated guidelines along with support from WHO and national health authorities.

Is adequate personal protective equipment available for health-care workers?

Personal safety in health-care workers became a hot topic because of the high transmission rates of SARS-CoV-2. OMF surgeons perform aerosol-generating procedures which mandate wearing adequate PPE during working hours.[15] Overall, AO CMF community globally feels that adequate PPE to the frontline health-care workers (HCWs) is lacking, although regional differences exist. A global survey pointed out that in Africa (79.2%), Asia (54.0%), Europe (54.0%), and South America (66.7%), most of the surgeons indicate that adequate PPE was not provided to their frontline HCWs, whereas in Australia (60.0%) and the Middle East (57.7%), the surgeons report their HCWs to receive adequate PPE.[14] The demand for PPE has escalated multiple folds to keep up the supply. The first systematic survey on the status of PPE for HCWs revealed that almost all components of PPE were found to be inadequately available or unavailable in most hospitals in India.[16]

Surprisingly, most of the respondents in our study (89.9%) had access to adequate PPE, COVID testing with no significant regional or practice differences which can be attributed to a different timeline and sample size of the survey.

What is the effect on clinical practice and earnings?

As the resources have been maneuvered toward the care of COVID-19, drawing an exact boundary between the real emergency cases, the semi-elective and elective ones have been the need of the hour. Like other medical and surgical specialties, OMF surgeons all over the world deferred elective surgeries till the pandemic is over.[14,17,18] Our study too showed that most CMFs performed emergency surgeries (93.3%) as compared to elective surgeries (51.7%) during the pandemic.

Telemedicine has enabled access to much-needed medical care. It decreases costs and saves time while conserving PPE supply and minimizing exposure to pathogens. It was not broadly used in health care before the COVID-19 pandemic.[19] This change was noted in our study too as approximately two-third of the surgeons were using teleconsultation and others were willing to replace physical OPD with teleconsultations. We believe that the practice of telemedicine can be helpful and relevant for the present scenario and should be continued beyond.

Doctors and patients have deferred physical OPD because of the fear of infection. Government organizations called for a nationwide OPD shutdown during the lockdown period. We observed a drastic loss in maxillofacial trauma cases as vehicles were not allowed on road. A reduction in OPD and operation numbers was expected. Questionnaire results showed a significant reduction in both OPD cases (73.9%) and surgery cases (66.7%) when compared to pre-COVID time. We expect these numbers to change soon as OPDs are been allowed to open systematically after the upliftment of lockdown.

The financial burden of performing procedures during COVID was increased as stated by most surgeons in our study, which can be accounted for the extra measure taken to prevent the spread of infection. As the economic growth of the country going in negative, we cannot expect ourselves to remain unharmed. The results from a worldwide survey by Van der Tas et al. showed that most CMF surgeons are suffering from severe negative economic loss.[14] As expected, loss of income was experienced more in self-employed and private practitioners as compared to salaried ones.

Globally, maxillofacial surgery departmental staff was reported to have been cut by 55% during the emergency.[20] Considering the unprecedented public health crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is highly vital to acknowledge the psychological impact of this escalating threat on health-care professionals. Reduction in income and fear of losing their job has become the cause of anxiety among all professionals, including maxillofacial surgeons.

What is the impact on academic research and human behavior?

The replacement of in-person classes with online equivalents is an obligation at this time but creates a loss of collaborative experiences that has the potential to be a significant disadvantage to education. We believe this shift in teaching has affected the resident students the most. A survey on the OMF surgery residency program reported that residents scheduled to graduate in 2022 were most concerned with the completion of graduation requirements and with decreased operative experience. About 52.8% of our participants reported decreased productivity in academic research.[21]

The important role of human behavior in managing the 2001–2002 Ebola outbreak in Uganda and during the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918–1919 is already counted valuable. Cancellation of large gatherings, social distancing, and simple hand washing helped to control the spread of these diseases. Studies have shown that hand hygiene is the single most important stratagem for preventing and reducing the spread of microorganisms.[22] Most participants in our study advocated that prevailing practices of hand hygiene should be continued even after the end of the pandemic and COVID-19 has positively affected behavior in our life.

Limitations

The cross-sectional design of the survey only provides an overview of a single snapshot at a particular time. Therefore, further follow-up surveys are necessary to understand the long-term impact of the changes made during the pandemic. Since no information about the nonresponders is known, we can only speculate on how this may have affected our outcomes of the survey.

CONCLUSION

This study, we believe, is the first of its kind done in India outlining the adverse effects of COVID-19 pandemic on OMF practice. Major findings from the survey are (1) most surgeons followed their hospital's guidelines to manage patients under the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) most of the respondents had access to adequate PPE and COVID testing, (3) most surgeons performed emergency surgeries as compared to elective surgeries, (4) the practice of telemedicine has gained popularity and is relevant for the present scenario and should be continued beyond, (5) COVID-19 has adversely affected the practice of OMF surgery and has led to anxiety due to significant reduction in both OPD and surgery cases, an economic crisis among surgeons experienced more in self-employed and private practitioners as compared to salaried ones, increased treatment cost, and decreased productivity in academic research, and (6) practice of hand hygiene should be continued to further control.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to all 178 respondents who answered the questionnaire. The time you have dedicated to this survey will be beneficial for the whole OMF community.

REFERENCES

- 1.Naming the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and The Virus that Causes It. [Last accessed on 2020 Oct 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirusdisease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it .

- 2.Day M. Covid-19: Identifying and isolating asymptomatic people helped eliminate virus in Italian village. BMJ. 2020;368:m1165. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weekly Epidemiological Update – November 30 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Dec 01]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiologicalupdate--30-november-2020 .

- 4.Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, Liang L, Huang H, Hong Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1177–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ather A, Patel B, Ruparel NB, Diogenes A, Hargreaves KM. Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19): Implications for clinical dental care. J Endod. 2020;46:584–95. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, Cheng L, Zhou X, Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12:9. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0075-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desai AN, Patel P. Stopping the spread of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323:1516. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai CC, Shih TP, Ko WC, Tang HJ, Hsueh PR. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges? Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55:105924. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Givi B, Schiff BA, Chinn SB, Clayburgh D, Iyer NG, Jalisi S, et al. Safety recommendations for evaluation and surgery of the head and neck during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146:579–84. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lockdown in India: Lockdown Till May 31 Can Stall Coron-Avirus Pandemic, Says Study | India News-Times of India. [Last accessed on 2020 May 11]. Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/lockdown-till-may-31-can-stall-coronavirus-pandemic-says-study/articleshow/75653149.cms .

- 12.Lancet T. India under COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet. 2020;395:1315. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30938-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant M, Schramm A, Strong B, Buchbinder D, Dodson TB, Fusetti S, et al. AO CMF International Task Force recommendations on best practices for maxillofacial procedures during COVID-19 pandemic. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2020;13:151–6. doi: 10.1177/1943387520948826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van der Tas J, Dodson T, Buchbinder D, Fusetti S, Grant M, Leung YY, et al. The global impact of COVID-19 on craniomaxillofacial surgeons. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2020;13:157–67. doi: 10.1177/1943387520929809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO Team. Rational Use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). WHO Team. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 19]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331498/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPCPPE_use-2020.2-eng.pdf .

- 16.Availability of PPE Kits Still a Major Issue in Indian Hospitals: Survey | The New Indian Express. [Last accessed on 2020 Nov 25]. Available from: https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2020/jun/24/availability-of-ppe-kits-stilla-major-issue-in-indian-hospitals-survey-2160628.html .

- 17.Zimmermann M, Nkenke E. Approaches to the management of patients in oral and maxillofacial surgery during COVID-19 pandemic. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2020;48:521–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barca D, Cordaro R, Kallaverja E, Ferragina F, Cristofaro MG. Management in oral and maxillofacial surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: Our experience. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;58:687–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teledental Practice and Teledental Encounters: An American Association of Teledentistry Position Paper. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 May 07]. Available from: https://www.americanteledentistry.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/ATDA_TeledentalPracticePositionPaper.pdf .

- 20.Maffia F, Fontanari M, Vellone V, Cascone P, Mercuri LG. Impact of COVID-19 on maxillofacial surgery practice: A worldwide survey. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;49:827–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2020.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huntley RE, Ludwig DC, Dillon JK. The early effect of COVID-19 on oraland maxillofacial surgery residency training – Results from a national survey. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;78:1257–67. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luangasanatip N, Hongsuwan M, Limmathurotsakul D, Lubell Y, Lee AS, Harbarth S, et al. Comparative efficacy of interventions to promote hand hygiene in hospital: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;351:h3728. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]