Abstract

This study examined whether fathers’ and mothers’ spanking contributed to development of child aggression in the first 5 years of life. We selected parents (N =1,298) who were married or cohabiting across all waves of data collection. Cross-lagged path models examined fathers’, mothers’, and both parents’ within-time and longitudinal associations between spanking and child aggression when the child was 1, 3, and 5 years of age. Results indicated that mothers spanked more than fathers. When examining fathers only, fathers’ spanking was not associated with subsequent child aggression. When examining both parents concurrently, only mothers’ spanking was predictive of subsequent child aggression. We found no evidence of multiplicative effects when testing interactions examining whether frequent spanking by either fathers or mothers was predictive of increases in children’s aggression. This study suggests that the processes linking spanking to child aggression differ for mothers and fathers.

Keywords: Corporal punishment, Physical punishment, Fatherhood, Child/ parent relationship, Parental discipline, Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study

1. Introduction

Most American parents use spanking, defined as “the use of physical force with the intention of causing a child to experience pain, but not injury, for the purpose of correcting or controlling a child’s behavior,” (Donnelly & Straus, 2005, p. 3) to discipline children. Studies show that spanking often begins early and occurs frequently. In one study that used the dataset examined in the present study (Fragile Families and Child Well-Being Study, or FFCWS), approximately one-third of mothers reported that they had spanked their 1-year-old child in the past month (Maguire-Jack, Gromoske, & Berger, 2012). Other research showed that 70% of mothers indicated they had spanked their child at least once by the time he or she was 2-years-old (Zolotor, Robinson, Runyan, Barr, & Murphy, 2011). In another FFCWS study that examined frequency of spanking by both mothers and fathers, the majority of three-year-olds (68%) were spanked at least once in the previous month by a parent, with a third of children spanked 1 to 2 times and two thirds of children spanked 3 or more times in the previous month (Lee, Taylor, Altschul, & Rice, 2013). By age 9 or 10, up to 94% of children have been spanked at least once in their lifetime (Straus & Stewart, 1999). For the most part, prior studies examining the effects of spanking on child wellbeing have focused on mothers’ use of the practice (for exceptions see Lee, Taylor, Altschul, & Rice, 2013; MacKenzie, Nicklas, Waldfogel, & Brooks-Gunn, 2013); much less is known about the potential impacts of fathers’ use of discipline. In the current study we address this gap and utilize a transactional parent-child framework to extend prior research regarding the nature of mother, father, and child relationships in the first five years of life.

1.1. Transactional models across the first five years

A growing body of empirical research indicates that spanking is associated with the development of children’s aggressive and antisocial behavior (Berlin et al., 2009; Gershoff, 2002; Grogan-Kaylor, 2004; Lansford et al., 2011; MacKenzie et al., 2013; Maguire-Jack et al., 2012). A recent FFCWS study showed that early maternal spanking is linked to children’s behavioral problems through the first decade of life (MacKenzie et al., 2013). One reason for this link may be that parents’ use of spanking models the use of aggression to solve problems (Bandura, 1973), and children imitate their parents’ use of aggression to solve their own conflicts or disagreements with peers and siblings. Furthermore, family coercion theory suggests that when parents use aggression or other forms of coercion to deal with problems, children may, over time, become resistant to its effects. As a result, the use of spanking is likely to escalate in frequency and severity, partly in response to children’s increased misbehavior, whether real or perceived by the parent (Patterson, 1982).

Such coercive family processes are developed and maintained through transactional processes between parent and child that unfold over time (Sameroff, 2009). Indeed, empirical evidence supports the presence of transactional mechanisms. First, after accounting for the child’s initial level of aggressive behavior or difficult temperament, prior studies using the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study’s Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K) and FFCWS have shown that spanking is associated with subsequent increases in child aggression in the first few years of life (Gershoff, Lansford, Sexton, Davis-Kean, & Sameroff, 2012; Gromoske & Maguire-Jack, 2012; Lee, Altschul, & Gershoff, 2013; Maguire-Jack et al., 2012). This is true in studies with direct pathways accounting for the influence of child behavior on mothers’ parenting (Gershoff et al., 2012; Maguire-Jack et al., 2012) and in the context of a parenting relationship high in maternal warmth (Lee, Altschul, & Gershoff, 2013). Similar transactional processes have been shown in studies of the Child Development Project and the Pitt Mother-Child Project with respect to the use of spanking and harsh discipline and increased risk for child antisocial behavior during the elementary and middle school years (Lansford et al., 2011).

Second, mothers appear to use more spanking with children whom they rate as having difficult temperaments, and mothers increase their use of spanking over time in response to children’s increased aggression. A study by Berlin et al. (2009) showed that child fussiness at age 1 was related to more spanking and verbal punishment of the child at age 3. Similarly, negative child emotionality at age 1 has been associated with increased maternal spanking at age 3, and higher levels of child aggression at age 3 have been found to predict maternal spanking at age 5 (Lee, Altschul, & Gershoff, 2013; Maguire-Jack et al., 2012). Such studies provide evidence supporting the basic tenets of the coercive family-process model (Patterson, 1982). Children respond to mothers’ greater use of physical discipline by becoming more aggressive, and it appears that mothers subsequently increase their reliance on spanking in response to children’s aggressive misbehavior.

However, prior transactional processes studies of spanking and the development of child aggression have not included fathers (e.g., Berlin et al., 2009; Gershoff et al., 2012; Gromoske & Maguire-Jack, 2012; Lee, Altschul, & Gershoff, 2013; Maguire-Jack et al., 2012). This is problematic for a number of reasons. First, children in two-parent families are likely to be spanked by both parents (Lee, Taylor, Altschul, & Rice, 2013; Straus & Stewart, 1999; Taylor, Lee, Guterman, & Rice, 2010). In addition, there is reason to believe that fathers’ disciplinary practices have a significant influence on children’s wellbeing. For example, one study showed fathers’ permissive discipline, but not mothers’, was associated with preschool children’s higher levels of externalizing behavior problems (Jewell, Krohn, Scott, Carlton, & Meinz, 2008). In two prior studies that examined fathers separately (i.e., not accounting for maternal influences), fathers’ spanking was associated with increased child aggression in pre-school (Lee, Taylor, Altschul, & Rice, 2013) and adolescence (Prinzie, Onghena, & Hellinckx, 2006). However, these studies did not examine mothers’ and fathers’ spanking together, and so could not isolate the relative contribution of each parent. Since mothers’ and fathers’ use of spanking is correlated (Lee, Taylor, Altschul, & Rice, 2013) not estimating the effects of both together may potentially overestimating the influence of one or the other parent’s use of spanking.

Furthermore, although traditional gender roles position mothers as nurturing caregivers and fathers as breadwinners and disciplinarians (Ferrari, 2002), studies suggest that mothers spank more frequently than fathers (Day, Peterson, & McCracken, 1998; Straus & Stewart, 1999). This may be due to the fact that mothers spend more time with young children (Craig, 2006; Yeung, Sandberg, Davis-Kean, & Hofferth, 2001) and therefore have more opportunities to engage in discipline than do fathers. However, even though fathers seem to spank less than mothers, it is not known whether fathers’ use of spanking has equal salience given the perception of their roles as differing from that of mothers—particularly the perception of their role as disciplinarian within the family context.

1.2. The current study

Given that the literature on spanking has almost exclusively focused on mothers, our primary research question was to examine whether paternal spanking predicts increased child aggression over time, and whether paternal spanking is reactive to children’s aggression in the same way that maternal spanking has been found to be (Lee, Altschul, & Gershoff, 2013; Maguire-Jack et al., 2012). Our first step was to extend prior studies that showed links between fathers’ spanking and child aggression by analyzing the extent to which father-child associations may be transactional or reciprocal, that is, the extent to which fathers’ use of spanking is influenced by changes in child aggression. We used cross-lagged path models to examine whether changes in fathers’ use of spanking between ages 1 and 3 had a significant influence on the development of child aggression at age 3 and changes in child aggression between ages 3 and 5, and the extent to which child aggression at age 3 influenced changes in fathers’ use of spanking between ages 3 and 5. We control for child temperament because even in infancy some parents react to difficult or “fussy” child temperament with spanking and harsh punishment (Martorell & Bugental, 2006). Guided by theory and prior studies showing strong evidence of transactional processes in mother-child associations, we hypothesized that fathers’ use of spanking would be associated with increased child aggression at subsequent ages, and that higher levels of child aggression would be predictive of fathers’ more frequent use of spanking at subsequent ages.

We also show these transactional processes for mothers in our sample of two-parent families. We present this model as a point of comparison for our father models, noting that our model replicates prior research that has established the existence of transactional mother-child processes (e.g., Lee, Altschul, & Gershoff, 2013; Maguire-Jack et al., 2012). The current sample differs from prior studies in that it included only mothers who were in two-parent families.

In our final research question, we examined whether spanking by fathers had associations with child aggression that explained unique variance in child aggression beyond effects of maternal influences. To answer this question, we tested a model that included cross-lags between paternal and maternal spanking and children’s aggression over time. We also examined multiplicative and additive effects of fathers’ and mothers’ spanking, specifically whether frequent spanking by either parent was predictive of increases in children’s aggression and whether more spanking by both parents lead to more child aggression. With very little prior research examining both fathers’ and mothers’ spanking and potential differential effects by gender of parent, our analyses were guided by the expectation that the influence of fathers and mothers would be similar.

Even in two-parent households, mothers spend more time with children (Craig, 2006; Yeung et al., 2001), and mothers and fathers may differ in their estimates of fathers’ involvement (Mikelson, 2008). Therefore, we control for fathers’ and mothers’ self-reports of their involvement in daily activities with the child, including routine caregiving and play. We control for symptoms of depression as well as parenting stress and alcohol consumption because studies of mothers (Farmer & Lee, 2011; Silverstein, Augustyn, Young, & Zuckerman, 2009; Taylor, Guterman, Lee, & Rathouz, 2009) and fathers (Davis, Davis, Freed, & Clark, 2011; Lee, Perron, Taylor, & Guterman, 2011; Reeb et al., 2014; Wilson & Durbin, 2010) have linked these factors to poorer parenting and physical punishment of young children. Furthermore, maternal distress and depression (Ciciolla, Gerstein, & Crnic, 2013; Goodman et al., 2011; Taylor, Manganello, Lee, & Rice, 2010) are direct and mediating factors linked to the development of child aggression. Given the nature of our sample, which consisted of two-parent families, we also controlled for parental IPV, or the presence of psychological aggression between parents. Studies show that psychological aggression between parents (Taylor et al., 2010) and lower overall parental relationship quality (Taylor et al., 2010; Verhoeven, Junger, van Aken, Dekovic, & van Aken, 2010) are associated with greater spanking and punishment of children; these factors have also been linked to higher levels child aggression (Ehrensaft & Cohen, 2012; Kim, Lee, Taylor, & Guterman, 2014). To the extent possible with the FFCWS data, we used fathers’ report of his behavior. Although mothers are mostly accurate in their estimates of fathers’ parenting behaviors, there is some evidence that mothers underestimate the frequency of fathers’ parenting aggression (Lee, Lansford, Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 2012).

2. Method

2.1. Data and participants

This study used data from fathers and mothers who participated in the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS) core interviews and the add-on In-Home Longitudinal Study of Pre-School Aged Children. The FFCWS is a birth-cohort study conducted in 20 U.S. cities with populations over 200,000. Respondents were recruited at hospitals and over the telephone at the time of the child’s birth. Both verbal and written informed consent were obtained from participants at each interview, and respondents were informed of the interviewers’ obligation to report observations of child abuse. A detailed description of the sampling strategy is published elsewhere (Reichman, Teitler, Garfinkel, & McLanahan, 2001).

Core FFCWS interviews were conducted with mothers and fathers of 4,898 index children at baseline, near the time of the target child’s birth, (Wave 1) and at 1 year (Wave 2), 3 years (Wave 3), and 5 years (Wave 4) following the target child’s birth. In addition, some mothers were selected to participate in the In-Home Longitudinal Study of Pre-School Aged Children, which was an add-on to the core interview and included in-home assessment of child behavior problems. In order to examine the research questions in this study we included in our analyses all fathers who indicated that they were married to or cohabitating with the target child’s mother across all waves (father and mother pairs, N =1,298). We only included data from parents who were in the same household across all time points because we were especially interested in how the associations between paternal spanking and child aggression develop during early childhood, while taking into account the effects of spanking by mothers.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Spanking child at 1, 3 and 5 years of age

Fathers and mothers responded to two questions, assessed when the child was age 1, age 3, and age 5: “Sometimes children behave pretty well and sometimes they don’t. In the past month, have you spanked (child) because (he/ she) was misbehaving or acting up?” (1 = no, 2 = yes). If the mother or father reported spanking the child in the past month, the parent was then asked, “Did you do this … 1 = every day or nearly every day, 2 = a few times a week, 3 = a few times this past month, or 4 = only once or twice)?” Consistent with prior studies, parents’ responses to these two questions were combined to create an ordinal variable of spanking (0 = never in the past month, 1 = only once or twice in the past month, 2 = a few times a month, a few times a week, or nearly every day in the past month).

2.2.2. Child aggression

The Child Behavior Checklist 1 1/2–5 (CBCL) (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) was administered to mothers only (i.e., not fathers) who participated in the In-Home Longitudinal Study of Pre-school Children interviews when their child was age 3 and age 5. When the child was age 3, mothers were asked to respond to 19 items from the CBCL aggressive behavior subscale such as “(He/she) is defiant” and “(He/she) gets in many fights” (α = .87). When the child was age 5, mothers were asked to respond to 20 items from the CBCL aggressive behavior subscale (α = .83). All questions were measured on an ordinal scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very true or often true). The CBCL aggressive behavior subscale items administered at age 5 were slightly modified to reflect the developmental changes that take place in early childhood. Items such as “showing off or clowning around” and “is easily jealous” were added to the subscale, whereas items such as “can’t wait turn” and “selfish/won’t share” were removed.

2.2.3. Parenting stress

At each core interview, fathers and mothers self-reported parenting stress based on items from the Parental Distress Subscale of the Parenting Stress Index–Short Form (PSI-SF) (Abidin, 1995) to indicate their agreement (1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree) with four statements, among them, “Being a parent is harder than I thought it would be” (α = .59 - .63 for fathers and α = .59 - .65 for mothers).

2.2.4. Parent daily caregiving involvement

At each core interview, fathers and mothers self-reported involvement in daily activities, assessed by number of days in one week that the mother or father self-reported that they engaged in activities such as playing games with child, reading to child, and showing affection toward child. They responded to 8 items when the child was age 1 and age 5, and 13 items when the child was age 3 (α = .69 - .74 for fathers and α = .60 - .69 for mothers). Number of items varied slightly among the three ages to reflect shifts in child development. For example, parents were asked about assisting the child with eating at age 3 and watching TV or videos together at age 5.

2.3. Parenting risk factors

Our analyses included fathers’ and mothers’ reports of psychosocial risk factors, assessed during core interviews when the target child was age 1. These included depression symptoms, heavy drinking day, and psychological intimate partner aggression. These factors can influence parental spanking as well as the development of children’s behavior problems. Therefore, they are potential confounds in the association between spanking and child aggression.

2.3.1. Major depression symptoms

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form (CIDI-SF), Section A (Kessler, Andrews, Mroczek, Ustun, & Wittchen, 1998), was used to measure parent self-report of depressive symptoms. The CIDI-SF is a standardized instrument that uses the criteria set forth in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) to determine probability that the respondent would be diagnosed with major depression if given the full CIDI interview. Major depression is indicated by feelings of depression or anhedonia experienced for most of the day, every day, for at least two weeks. Participants were classified as likely to have major depression if they endorsed the screening items and three or more depressive symptoms, among them losing interest, feeling tired, and change in weight (0 = no, 1 = yes).

2.3.2. Heavy drinking day

A dichotomous variable indicated whether the parent had a “heavy drinking day” in the past 12 months, based on self-report of having consumed four or more drinks in one day (0 = consumed 0-3 drinks in 1 day in the past year, or 1 = consumed ≥4 drinks in 1 day in the past year). This operationalization of heavy drinking day is based on criteria set forth by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, which defines a heavy drinking as ≥5 drinks in a single day for men and ≥4 drinks in a single day for women (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2005).

2.3.3. Psychological intimate partner aggression

Each spouse reported how often they were subject to psychological aggression from their partner using four items adapted from the Spouse Observation Checklist (Lloyd, 1996; Weiss & Margolin, 1977), for example, “He tries to keep you from seeing or talking with your friends or family.” This variable was dichotomized for analysis (0 = none, 1 = any).

2.4. Child control variables

Child temperament at age 1 was used as an early proxy for whether mothers found the child’s behavior difficult and was assessed with the Emotionality, Activity, and Sociability (EAS) Temperament Survey for Children (Mathieson & Tambs, 1999). Mothers indicated (1 = not at all like my child to 5 = very much like my child) the extent to which their child “often fusses and cries,” “gets upset easily,” and “reacts strongly when upset” (α = .59). Mothers also reported child gender at baseline (indicated by 0 = girl, 1 = boy).

2.5. Demographic control variables

The following demographic control variables were assessed at the time of the child’s birth: fathers’ and mothers’ age, fathers’ and mothers’ education level (1 = less than high school, 2 = high school degree or GED, 3 = some college/technical school, 4 = college degree or higher), fathers’ and mothers’ race/ ethnicity (1 = White, 2 = Black, 3 = Hispanic, 4 = Other race/ethnicity), and household income.

2.6. Analysis plan

All analyses were conducted in Mplus 7.11. The χ2 test, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used to evaluate fit between the hypothesized models and observed data, with values of .95 for CFI and .06 for RMSEA establishing good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The cluster option within Mplus was used to account for the sampling design in which respondents were clustered in cities.

Across all control variables data were missing in 0 to 3.8% of cases. Fathers’ spanking variables were missing in 1.0%, 0.4%, and 0.2% of cases at ages 1, 3, and 5, respectively. Mothers’ spanking variables were missing in 1.2%, 1.9%, and 2.1% of cases at ages 1, 3, and 5, respectively. The CBCL composite of child aggression at age 3 was missing in 18.0% of cases and the CBCL composite of child aggression at age 5 was missing in 27.3% of cases; the higher level of missing data for these variables is due to the fact that these variables were drawn from the In-Home Longitudinal Study of Pre-school Children interview, which was not administered to all families. In order to maximize sample size and to avoid biasing the sample by removing cases with missing data, we followed a procedure used in prior studies and estimated all models using full information maximum likelihood estimation in Mplus, which along with multiple imputation is considered a preferred method for handling missing data (Graham, 2009). Other studies have found that FFCWS longitudinal sub-samples with data available on all variables differ from sub-samples with some missing data in terms of socio-economic indicators (Cooper, McLanahan, Meadows, & Brooks-Gunn, 2009), thus using all available data is preferable.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for key study variables, as reported by mothers and fathers. More mothers than fathers reported spanking their child at all three ages. At age 1, 21.3% of mothers and 19.4% of fathers reported that they had spanked their child at least once in the past month. At age 3, 52.8% of mothers and 43.9% of fathers reported that they had spanked their child at least once in the past month. At age 5, 45.7% of mothers and 35.2% of fathers reported that they had spanked their child at least once in the past month.

Table 1.

Description of Sample and Bivariate Statistics.

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1298 (100%) | n = 1298 (100%) | |||||

| Variable (Range) | % or M(SD) | % or M(SD) | t(df) or χ2(df) | |||

| Use of Spanking | ||||||

| When child is 1-year-old (0–2)‡ | χ2(2) = 2.39 | |||||

| No spanking in past month (0) | 78.7 | 80.6 | ||||

| Once or twice in past month (1) | 11.2 | 10.9 | ||||

| A few times to nearly every day (2) | 9.1 | 7.5 | ||||

| When child is 3-years-old (0–2)‡ | χ2(2) = 18.16 | *** | ||||

| No spanking in past month (0) | 47.2 | 56.1 | ||||

| Once or twice in past month (1) | 28.8 | 25.5 | ||||

| A few times to nearly every day (2) | 22.3 | 18.0 | ||||

| When child is 5-years-old (0–2)‡ | χ2(2) = 24.25 | *** | ||||

| No spanking in past month (0) | 54.3 | 64.8 | ||||

| Once or twice in past month (1) | 29.3 | 23.3 | ||||

| A few times to nearly every day (2) | 14.5 | 11.7 | ||||

| Child Variables (Maternal Report) | ||||||

| EAS child temperament at 1-year-old (1–5)a | 2.70 | (0.98) | ||||

| CBCL aggression at 3-years-old (0–1.95)a | 0.58 | (0.33) | ||||

| CBCL aggression at 5-years-old (0–1.65)a | 0.48 | (0.28) | ||||

| Child gender (% boy) | 52.2 | |||||

| Psychosocial Variables | ||||||

| Parenting stress at 1-year-old (1–4)a | 2.10 | (0.63) | 2.04 | (0.66) | t(1105) = 2.68 | ** |

| Parenting stress at 3-years-old (1–4)a | 2.23 | (0.63) | 2.05 | (0.64) | t(1276) = 7.67 | *** |

| Parenting stress at 5-years-old (1–4)a | 2.14 | (0.64) | 1.98 | (0.66) | t(1273) = 6.91 | *** |

| Caregiving involvement at 1-year-old (0–7)a | 5.33 | (0.94) | 4.77 | (1.20) | t(1106) = 13.18 | *** |

| Caregiving involvement at 3-years-old (0–7)a | 5.00 | (0.88) | 4.50 | (1.05) | t(1277) = 14.05 | *** |

| Caregiving involvement at 5-years-old (0–7)a | 4.62 | (1.15) | 4.02 | (1.23) | t(1273) = 14.33 | *** |

| Depression symptoms at 1-year-old (% yes) | 11.3 | 5.9 | χ2(1) = 25.47 | *** | ||

| Heavy drinking day at 1-year-old (% yes) | 4.8 | 25.5 | χ2(1) = 215.57 | *** | ||

| Psychological IPA at 1-year-old (% yes) | 40.8 | 54.4 | χ2(1) = 38.79 | *** | ||

| Demographic Variables | ||||||

| Household income at baseline (0–133,750) | $46,091 | (38,766) | $47,608 | (39,088) | t(1297) = 4.77 | *** |

| Education level at baseline: | χ2(3) = 1.22 | |||||

| Less than high school (%) | 24.1 | 25.3 | ||||

| High school degree or GED (%) | 26.2 | 26.2 | ||||

| Some college/tech. school (%) | 26.4 | 26.8 | ||||

| College or higher (%) | 23.2 | 21.5 | ||||

| Race/ ethnicity: | ||||||

| White (comparison group; %) | 34.2 | 32.8 | χ2(1) = 0.625 | |||

| Black (%) | 30.7 | 32.6 | χ2(1) = 0.947 | |||

| Hispanic (%) | 29.7 | 30.2 | χ2(1) = 0.068 | |||

| Other (%) | 5.1 | 4.3 | χ2(1) = 0.885 | |||

| Age at child’s birth (15–61) | 27.3 | (6.14) | 29.7 | (6.78) | t(1297) = 18.33 | *** |

Note: CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist, EAS = Emotionality, Activity, and Sociability Temperament Survey for Children, IPA = Intimate partner aggression from other parent.

Higher scores indicate higher levels of the construct.

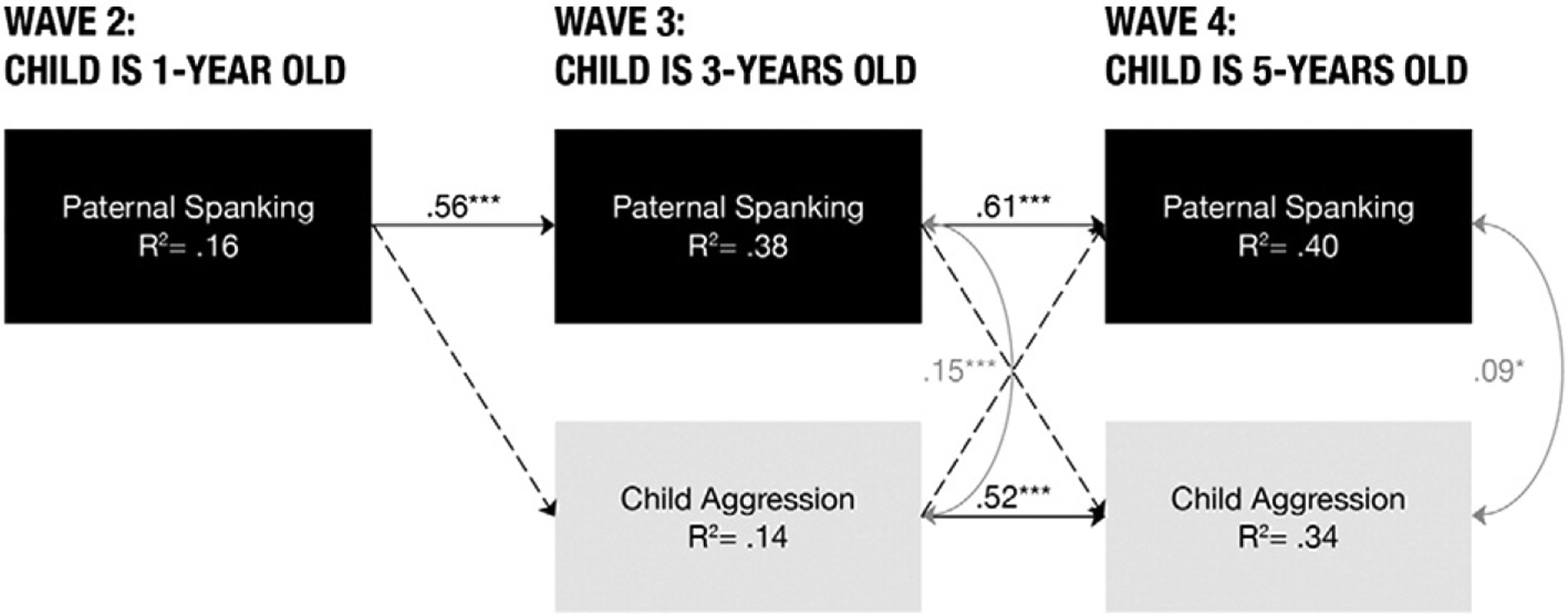

3.1. Cross-lag model of fathers’ spanking and children’s aggression

The first path model (Fig. 1) assessed the associations of fathers’ spanking at age 1, age 3, and age 5 with CBCL child aggression at age 3 and age 5 and fit the data adequately (χ2(29) =104.70, p = .000; CFI = .940; RMSEA = .045; n =1297). Paternal spanking was correlated with child aggression within the same time point when children were age 3 (r = .15, p < .001) and when they were age 5 (r = .09, p < .05). However, paternal spanking at age 1 did not predict level of child aggression at age 3, and change in paternal spanking between ages 1 and 3 did not predict change in child aggression between ages 3 and 5. Similarly, child aggression at age 3 did not predict changes in paternal spanking between ages 3 and 5. This model, including all control variables, accounted for 14% of variance in child aggression at age 3 and 34% of variance in child aggression at age 5.

Fig. 1. Reciprocal Effects Between Paternal Spanking and Child Aggression.

Fig. 1 Note. All variables were regressed on a full set of controls: fathers’ parenting stress, fathers’ involvement with child at age 1, age 3, and age 5, fathers’ major depression symptoms, fathers’ heavy drinking day, fathers’ psychological aggression from child’s mother at age 1, child gender, child temperament, fathers’ race, fathers’ age, fathers’ education level, and family income. Dotted lines indicate non-significant relationships. *** p ≤ .001, ** p ≤ .01, * p ≤ .05.

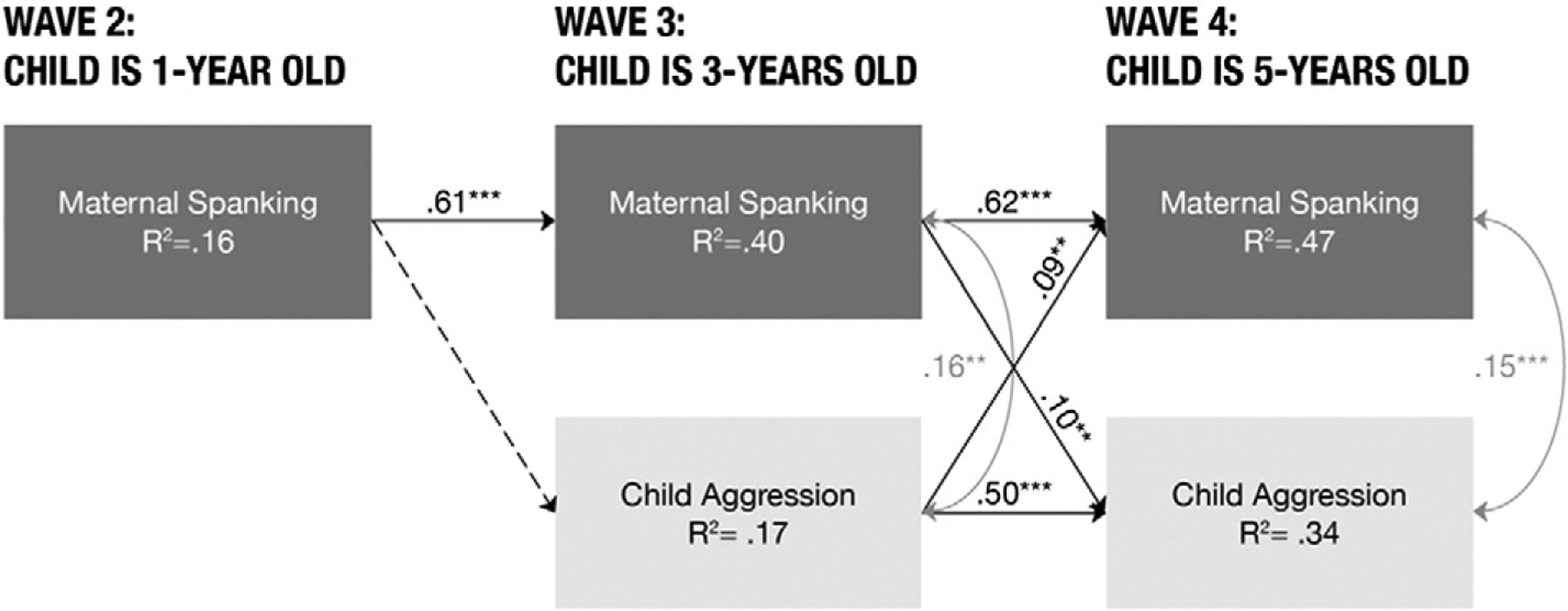

3.2. Cross-lag model of mothers’ spanking and children’s aggression

We present a second path model (Fig. 2) that assessed the associations of mothers’ spanking with child aggression across three waves of data. This model replicates several prior studies (e.g., Lee, Altschul, & Gershoff, 2013; Maguire-Jack et al., 2012), albeit the current sample differs in that we included only mothers in two-parent families. As expected based on prior research, this model fit the data well (χ2(29) = 70.99, p = .000; CFI = .970; RMSEA = .033; n = 1,294). This model shows that maternal spanking at age 3 was predictive of increased child aggression between ages 3 and 5 (ß = .10, p < .01). At the same time, child aggression at age 3 was predictive of increased maternal aggression between ages 3 and 5 (ß = .09, p < .01). In addition, maternal spanking at Waves 3 and 4 was correlated with child aggression within the same time point (r = .16, p < .01, and r = .15, p < .001, respectively). This model accounts for 17% of variance in child aggression at age 3 and 34% of variance in child aggression at age 5.

Fig. 2. Reciprocal Effects between Maternal Spanking and Child Aggression.

Fig. 2 Note. All variables were regressed on a full set of controls: mothers’ parenting stress, mothers’ involvement with child at age 1, age 3, and age 5, mothers’ major depression symptoms, mothers’ heavy drinking day, mothers’ psychological aggression from child’s mother at age 1, child gender, child temperament, mothers’ race, mothers’ age, mothers’ education level, and family income. *** p ≤ .001, ** p ≤ .01, * p ≤ .05.

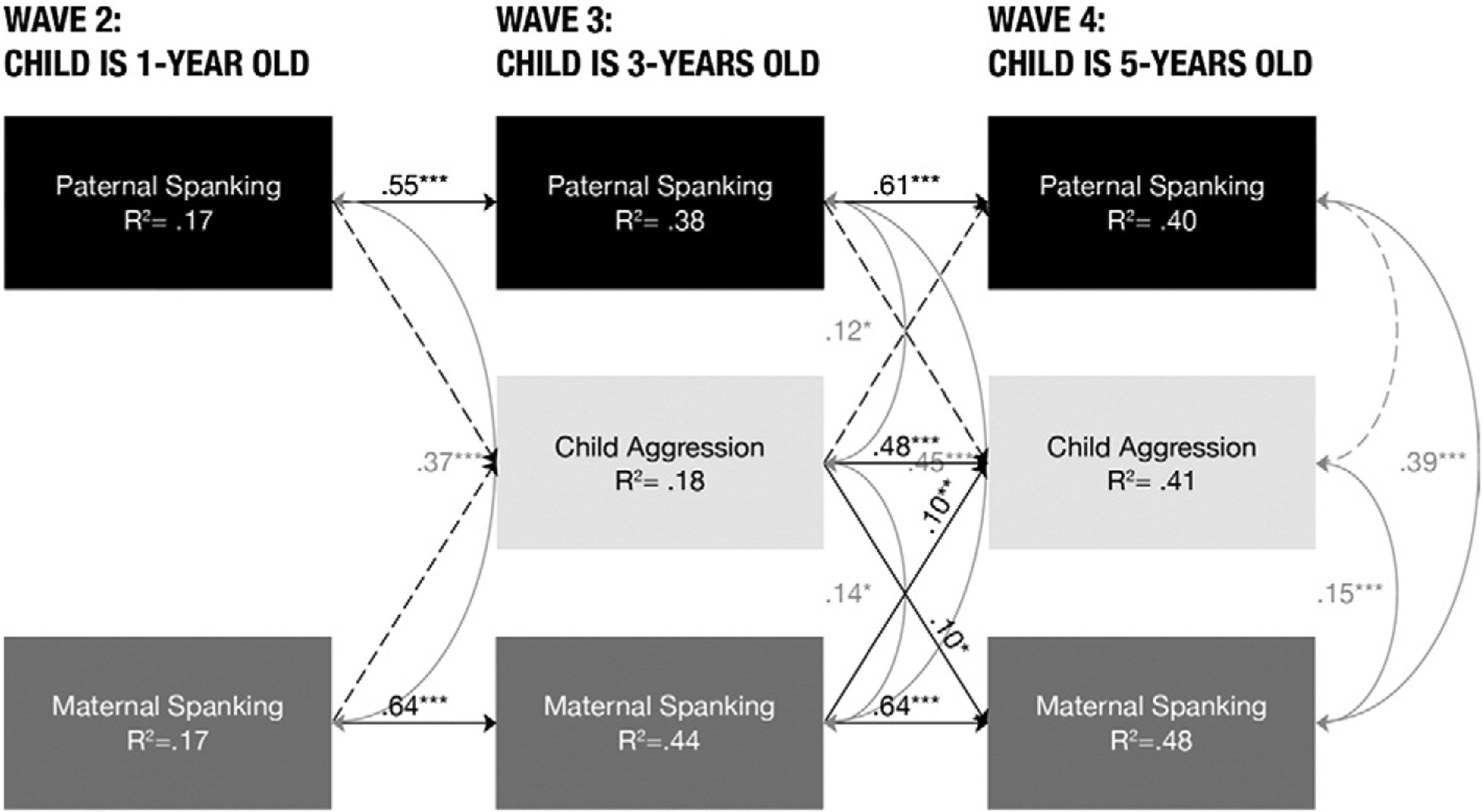

3.3. Cross-lag model of fathers’ and mothers’ spanking and children’s aggression

In our final path model (Fig. 3), we examined the associations of fathers’ and mothers’ spanking with change in children’s aggression across time, controlling for covariates as reported by both parents. This model fit the data reasonably well (χ2 (184) =289.14, p = .000; CFI = .943; RMSEA = .021; n =1,298). In this combined model, fathers’ spanking was still not significantly predictive of children’s aggression at age 3, nor was fathers’ spanking significantly predictive of increases in children’s aggression between ages 3 and 5. Neither was fathers’ spanking reactive to children’s aggression; the paths from children’s aggression to fathers’ spanking were both not significant. In contrast, mothers’ use of spanking at age 3 predicted increases in children’s aggression between age 3 and age 5 (ß = .10, p < .05). Children’s aggression at age 3 in turn predicted increases in maternal spanking between age 3 and age 5 (ß = .10, p < .01). Despite these differential associations with children’s aggression, fathers’ spanking and mothers’ spanking were significantly correlated with one another at each child age (rage 1 = .37, p < .001; rage 3 = .45, p < .001; rage 5 = .39, p < .001). Fathers’ spanking was only associated with children’s aggression within the same time point at age 3 (r = .12, p < .01), while mothers’ spanking was correlated with children’s aggression at each age (rage 3 = .14, p < .05) and (rage 5 = .15, p < .001). This combined model accounted for 18% of the variance in children’s aggression at age 3 and 41% of the variance in the change in children’s aggression between age 3 and age 5.

Fig. 3. Reciprocal Effects Between Paternal and Maternal Spanking and Child Aggression.

Fig. 3 Note. All variables were regressed on a full set of controls: fathers’ and mothers’ parenting stress, fathers’ and mothers’ involvement with child at age 1, age 3, and age 5; fathers’ and mothers’ major depression symptoms, fathers’ and mothers’ heavy drinking day, fathers’ and mothers’ psychological aggression from partner at age 1, child gender, child temperament, child’s race, parents’ averaged age, highest level of parent education, and family income. Dotted lines indicate non-significant relationships. *** p ≤ .001, ** p ≤ .01, * p ≤ .05.

3.4. Interaction of fathers’ and mothers’ spanking

We conducted additional analyses to test whether fathers’ and mothers’ spanking interacted with one another to have an amplifying effect on children’s aggression. In these analyses we included an additive and multiplicative interaction term of fathers’ spanking and mothers’ spanking in the model at age 1, age 3, and age 5. None of these interactions predicted children’s aggression at age 3 or change in aggression between age 3 and age 5. The models with these interaction terms were not better-fitting models than the previous model without the interactions. We thus concluded that there was no evidence of an interaction effect between fathers’ and mothers’ spanking.

4. Discussion and conclusion

In multiple studies using data from longitudinal, diverse samples of parents and children, research continues to build a strong case that spanking is detrimental to children and is associated with children’s greater aggressive behavior (Berlin et al., 2009; Gershoff, 2002; Gershoff, 2013; Gershoff et al., 2012; Grogan-Kaylor, 2004; Lansford et al., 2011; Lee, Altschul, & Gershoff, 2013; MacKenzie et al., 2013; Maguire-Jack et al., 2012). However, prior studies of spanking that included fathers have generally examined predictors of fathers’ spanking (Lee, Guterman, & Lee, 2008; Lee et al., 2011); fathers’ spanking separately from mothers (Lee, Taylor, Altschul, & Rice, 2013; Prinzie et al., 2006); or did not examine the transactional nature of parent child interactions (Lee, Taylor, Altschul, & Rice, 2013). The current study is unique because the separate and simultaneous use of transactional models to examine fathers’ and mothers’ use of physical punishment permits us to identify whether fathers’ use of spanking has any unique influence after accounting for mothers’ spanking. This close examination helps to disentangle the relative contribution of mothers and fathers in this important domain of child development.

We used longitudinal models during the first five years of life to examine hypotheses related to whether paternal spanking predicted increased child aggression over time and whether paternal spanking was reactive to children’s aggression, essentially seeking to replicate prior studies examining maternal spanking (e.g., Lee, Altschul, & Gershoff, 2013; Maguire-Jack et al., 2012). Similar to prior studies, we found that mothers reported that they spanked children more frequently than fathers (Day et al., 1998; Straus & Stewart, 1999).

Our hypotheses pertaining to the father-child transactional processes were not supported. In contrast to prior studies of maternal spanking and child aggression (e.g., Lee, Altschul, & Gershoff, 2013; Maguire-Jack et al., 2012), fathers’ spanking was not predictive of increases in children’s aggression over time. Furthermore, we found no evidence that fathers changed their rate of spanking as a result of their children’s prior aggression, leading us to conclude that the transactional processes observed between mothers and their children in prior studies were not replicated between fathers and their children in this sample. Thus, it was not surprising that, when we included the effects of both parents, only maternal spanking at age 3 was associated with children’s significantly increased aggression at age 5.

These results may be influenced by the fact that overall fathers used spanking less than did mothers. As seen in Table 1, at age 1 fathers and mothers did not differ significantly in their use of spanking (18.4% of fathers and 20.3% of mothers self-reported spanking at least once in the past month). However, at age 3 and at age 5, the gap between fathers’ and mothers’ use of spanking increased significantly (43.5% of fathers and 51.1% of mothers, and 35% of fathers and 43.8% of mothers respectively). Even though large mean differences existed at two ages, with fathers spanking less than mothers, it is still possible that fathers’ punishment may exacerbate or hasten the development of child aggression, following the old adage, “Just wait until your father gets home!” We examined this possibility by testing an interaction term within the cross-lagged path models, and we found no evidence that fathers’ spanking amplified or exacerbated the influence of maternal spanking, or vice versa. Overall, these results suggest that fathers’ influence may be reduced mainly through their relatively lower levels of use of spanking during this time period.

Even in two-parent families, fathers are generally less involved in the daily care of infants and toddlers (Craig, 2006). As a result, mothers may engage in more nurturing and disciplinary behaviors, and thus may have more opportunities to positively or negatively influence their child. Cognizant of this fact, we controlled for each parent’s self-reported involvement in daily caregiving to strengthen the validity of our models. Bivariate analyses (Table 1) indicated that mothers in our sample did indeed report more engagement in these activities across all waves of data collection. Because we minimized the possibility that any observed effects were explained by greater parental involvement or time spent with the child, it seems unlikely that the results were driven primarily by fathers’ and mothers’ differential time spent caring for their young child. Nonetheless, there are notable limitations of the measure used to indicate parents’ daily involvement. By asking parents to report only the number of days in one week spent in activities, this measure of involvement may miss important variation in mothers’ and fathers’ actual time (minutes and hours) spent in these activities. Also, the caregiving involvement scale asks about a limited set of activities focused primarily on play and less on routine caregiving, another factor that may underestimate differences in mothers’ and fathers’ routine caregiving of young children.

Another potential explanatory factor for the lack of strong findings regarding the influence of paternal spanking on the development of child aggression relates to the nature of the study subsample. We selected families in which mothers and fathers were the biological parents of the child and were married or cohabiting at each wave of data collection. As a result, our selection criteria biased the sample toward more advantaged families (Carlson & McLanahan, 2010; Guzzo & Lee, 2008). Parents in stable married and cohabiting families have lower levels of depression (Meadows, McLanahan, & Brooks-Gunn, 2007), lower levels of parenting stress (Cooper et al., 2009), lower levels of inter-parental aggression, and better relationship quality than those who are not in stable married and cohabitating relationships. Furthermore, there are lower levels of child aggression in two-parent families (Sourander & Helstelä, 2005). For example, one prior study using FFCWS data showed that children in two-parent households had a lower mean level of aggression when compared to children in a sample that combined one-parent and two-parent households (Lee, Taylor, Altschul, & Rice, 2013). Therefore, it is possible that our findings may stem in part from the relatively advantaged nature of our subsample of two-parent families.

Much remains to be understood about the mechanisms and processes by which fathers impact child wellbeing. In the case of discipline, it may be that fathers’ roles are more nuanced than the effects we have examined in the current study. Future research into the joint impacts of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting on children’s development may thus need to examine interactions of maternal discipline with other aspects of paternal parenting behavior.

4.1. Approaches to reduce spanking

Although the results of this study did not suggest a strong influence for fathers’ spanking behavior, and, consistent with prior studies, the correlations linking maternal spanking to child aggression were modest, it is important to note that spanking by either parent did not improve children’s behavior over time. When these findings are viewed in light of prior research on this topic, there is reason to believe that spanking is an ineffective method for reducing problematic child behaviors (Gershoff, 2013). There are a number of practical avenues for practitioners and clinicians who are interested in helping parents reduce spanking. One recent study showed that exposing parents to research findings on spanking can reduce positive attitudes toward the use of spanking (Holden, Brown, Baldwin, & Caderao, 2013), suggesting that simply educating parents about the research findings may be an effective first step for reducing use of corporal punishment. Pediatricians are a trusted source of advice on discipline, and another promising approach to reduce spanking is through the use of parent education in health care settings. Research suggests that brief, structured parent education, delivered via short video segments in the pediatrician’s office, reduces parents’ support for and planned use of spanking (Scholer, Hudnut-Beumler, & Dietrich, 2010). Another study showed that mothers of young children who were exposed to messages about spanking that were embedded in simple educational baby books were less likely to spank their children (Reich, Penner, Duncan, & Auger, 2012), suggesting that non-intrusive messaging can reduce mothers’ actual usage of corporal punishment.

4.2. Study strengths and limitations

This study uses longitudinal data across the first five years of life to examine the relative contribution of fathers’ and mothers’ spanking to the development of child aggression. The findings of this study are strengthened by the fact that we used a large, diverse, community-based sample of fathers and mothers of young children. However, there are several limitations of this study. First, results from this subsample of married or cohabiting mothers and fathers living in urban areas may not be generalizable to parents living in non-urban geographic locations. Moreover, we selected a subsample of parents who were married or cohabiting during the first five years of their children’s lives. Thus, the results of this study do not generalize to non-married or non-cohabiting parents, nor do the results speak to the potential influences of nonresidential fathers. Second, we only had mother-ratings of child aggression available in the dataset; thus, it is possible that shared-rater variance accounts for the stronger associations between maternal spanking and mother-rated child aggression. Future studies that use both mother and father-reports of child aggression or non-parent reporters (such as teachers or observers) will be needed to confirm that our findings are robust to shared rater variance.

4.3. Conclusions

Contrary to our prediction, spanking by fathers is not predictive of changes in child aggression over time, although it is correlated with child aggression within time. We found no evidence supporting potential interaction effects between mothers’ and fathers’ spanking on child aggression. Rather, mothers’ spanking had a main effect on increases in children’s aggression over time, as has been found in several prior studies. Spanking by either parent did not improve children’s behavior over time, adding to the existing literature linking spanking with detrimental rather than beneficial child outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study is funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) through grants R01HD36916, R01HD39135, and R01HD40421, as well as a consortium of private foundations. The analyses reported herein were the result of secondary data analysis supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF; Grant # BCS 0818478) through the Developmental Learning Science-IRADS Collaborative on the Analysis of Pathways from Childhood to Adulthood at the University of Michigan. We would like to thank Margaret Chen for her assistance in creating the figures for this manuscript.

References

- Abidin R (1995). Parent Stress Inventory (3rd ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessments Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2000). Manual for the ASEBA Preshool Forms and Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1973). Aggression: A social learning analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Ispa JM, Fine MA, Malone PS, Brooks-Gunn J, Brady-Smith C, et al. (2009). Correlates and consequences of spanking and verbal punishment for low-income White, African American, and Mexican American toddlers. Child Development, 80(5), 1403–1420. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MJ, & McLanahan SS (2010). Fathers in fragile families. In Lamb ME (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (pp. 241–269) (5th ed.). CITY, NJ: Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Ciciolla L, Gerstein ED, & Crnic KA (2013). Reciprocity among maternal distress, child behavior, and parenting: Transactional processes and early childhood risk. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–14. 10.1080/15374416.2013.812038 (ahead-of-print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CE, McLanahan SS, Meadows SO, & Brooks-Gunn J (2009). Family structure transitions and maternal parenting stress. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 71, 558–574. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig L (2006). Does father care mean fathers share? A comparison of how mothers and fathers in intact families spend time with children. Gender and Society, 20, 259–281. 10.1177/0891243205285212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RN, Davis MM, Freed GL, & Clark SJ (2011). Fathers’ depression related to positive and negative parenting behaviors with 1-year-old children. Pediatrics, 127(4), 611–619. 10.1542/peds.2010-1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day RD, Peterson GW, & McCracken C (1998). Predicting spanking of younger and older children by mothers and fathers. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60(1), 79–94. 10.2307/353443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly M, & Straus MA (2005). Corporal punishment of children in theoretical perspective. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, & Cohen P (2012). Contribution of family violence to the intergenerational transmission of externalizing behavior. Prevention Science, 13, 370–383. 10.1007/s11121-011-0223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer AY, & Lee SK (2011). The effects of parenting stress, perceived mastery, and maternal depression on parent-child interaction. Journal of Social Service Research, 37(5), 516–525. 10.1080/01488376.2011.607367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari AM (2002). The impact of culture upon child rearing practices and definitions of maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 26, 793–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 539–579. 10.1037//0033-2909.128.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET (2013). Spanking and child development: We know enough now to stop hitting our children. Child Development Perspectives, 7, 133–137. 10.1111/cdep.12038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Lansford JE, Sexton HR, Davis-Kean PE, & Sameroff AJ (2012). Longitudinal links between spanking and children’s externalizing behaviors in a national sample of White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian American Families. Child Development, 83(3), 838–843. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, & Heyward D (2011). Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 1–27. 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham GW (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Pyschology, 60, 549–576. 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan-Kaylor A (2004). The effect of corporal punishment on antisocial behavior in children. Social Work Research, 28(3), 153–162. 10.1093/swr/28.3.153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gromoske AN, & Maguire-Jack K (2012). Transactional and cascading relations between early spanking and children’s social-emotional development. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 74, 1054–1068. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01013.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB, & Lee H (2008). Couple relationship status and patterns in early parenting practices. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 70(1), 44–61. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00460.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW, Brown AS, Baldwin AS, & Caderao KC (2013). Research findings can change attitudes about corporal punishment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 38(5), 902–908. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L-T, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modelling, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jewell JD, Krohn EJ, Scott VG, Carlton M, & Meinz E (2008). The differential impact of mothers’ and fathers’ discipline on preschool children’s home and classroom behavior. North American Journal of Psychology, 10(1), 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, Ustun B, & Wittchen HU (1998). The World Health Organization composite international diagnostic interview short-form (CIDI-SF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 7(4), 171–185. 10.1002/mpr.47. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Lee SJ, Taylor CA, & Guterman NB (2014). Dyadic profiles of parental disciplinary behavior and links with parenting context. Child Maltreatment, 19, 79–91. 10.1177/1077559514532009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Criss MM, Laird RD, Shaw DS, Pettit GS, Bates JE, et al. (2011). Reciprocal relations between parents’ physical discipline and children’s externalizing behavior during middle childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 225–238. 10.1017/S0954579410000751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Altschul I, & Gershoff ET (2013). Does warmth moderate longitudinal associations between maternal spanking and child aggression in early childhood? Developmental Psychology, 49(11), 2017–2028. 10.1037/a0031630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Guterman NB, & Lee Y (2008). Risk factors for paternal physical child abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect, 32, 846–858. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Lansford JE, Pettit GS, Bates JE, & Dodge KA (2012). Parental agreement of reporting parent to child aggression using the Conflict Tactics Scales. Child Abuse and Neglect, 36, 510–518. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Perron BE, Taylor CA, & Guterman NB (2011). Paternal psychosocial characteristics and corporal punishment of their 3-year-old children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(1), 71–87. 10.1177/0886260510362888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Taylor CA, Altschul I, & Rice J (2013). Parental spanking and subsequent risk for child aggression in father-involved families of young children. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(9), 1476–1485. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd S (1996). Physical aggression, distress, and everyday marital interaction. In Cahn DD, & Lloyd SA (Eds.), Family violence from a communication perspective (pp. 177–198). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie MJ, Nicklas E, Waldfogel J, & Brooks-Gunn J (2013). Spanking and child development across the first decade of life. Pediatrics, 132(5), e1118–e1125. 10.1542/peds.2013-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Jack K, Gromoske AN, & Berger LM (2012). Spanking and child development during the first five years of life. Child Development, 83(6), 1960–1977. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01820.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martorell GA, & Bugental DB (2006). Maternal variations in stress reactivity: Implications for harsh parenting practices with very young children. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(4), 641–647. 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson KS, & Tambs K (1999). The EAS temperament questionnaire—Factor structure, age trends, reliability, and stability in a Norwegian sample. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(3), 431–439. 10.1111/1469-7610.00460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows SO, McLanahan SS, & Brooks-Gunn J (2007). Parental depression and anxiety and early childhood behavior problems across family types. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 69(5), 1162–1177. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00439.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikelson KS (2008). He said, she said: Comparing mother and father reports of father involvement. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 70, 613–624. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00509.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2005). Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide (updated 2005 edition). Available from: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/guide.pdf

- Patterson GR (1982). Coercive Family Process. Eugene, OR: Castalia. [Google Scholar]

- Prinzie P, Onghena P, & Hellinckx W (2006). A cohort-sequential multivariate latent growth curve analysis of normative CBCL aggressive and delinquent problem behavior: Associations with harsh discipline and gender. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30(5), 444–459. 10.1177/0165025406071901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reeb BT, Wu EY, Martin MJ, Gelardi KL, Chan SY, & Conger KJ (2014). Long-term effects of fathers’ depressed mood on youth internalizing symptoms in early adulthood. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 10.1111/jora.12112 (Advance online publication). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich SM, Penner EK, Duncan GJ, & Auger A (2012). Using baby books to change new mothers’ attitudes about corporal punishment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 36, 108–117. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, & McLanahan SS (2001). Fragile families: Sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review, 32, 303–326. 10.1016/S0190-7409(01)00141-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ (2009). The transactional model. In Sameroff AJ (Ed.), The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other (pp. 3–21). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 10.1037/11877-000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scholer SJ, Hudnut-Beumler J, & Dietrich MS (2010). A brief primary care intervention helps parents develop plans to discipline. Pediatrics, 125, e242–e249. 10.1542/peds.2009-0874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Augustyn M, Young R, & Zuckerman B (2009). The relationship between maternal depression, in-home violence and use of physical punishment: What is the role of child behaviour? Archives of Disease in Childhood, 94, 138–143. 10.1136/adc.2007.128595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sourander A, & Helstelä L (2005). Childhood predictors of externalizing and internalizing problems in adolescence. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 14(8), 415. 10.1007/s00787-005-0475-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, & Stewart JH (1999). Corporal punishment by American parents: National data on prevalence, chronicity, severity, and duration, in relation to child and family characteristics. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 2, 55–70. 10.1023/A:1021891529770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CA, Guterman NB, Lee SJ, & Rathouz P (2009). Intimate partner violence, maternal stress, nativity, and risk for maternal maltreatment of young children. American Journal of Public Health, 99(1), 175–183. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.126722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CA, Lee SJ, Guterman NB, & Rice J (2010). Use of spanking for 3-year-old children and associated intimate partner aggression or violence. Pediatrics, 126(3), 415–424. 10.1542/peds.2010-0314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CA, Manganello JA, Lee SJ, & Rice J (2010). Mothers’ spanking of 3-year-old children and subsequent risk of children’s aggressive behavior. Pediatrics, 125(5), e1057–e1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven M, Junger M, van Aken C, Dekovic M, & van Aken MAG (2010). Mothering, fathering, and externalizing behavior in toddler boys. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 72(2), 307–317. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00701.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RL, & Margolin G (1977). Assessment of marital conflict and accord. In Ciminero AR, Calhoun KD, & Adams HE (Eds.), Handbook of behavioral assessment (pp. 555–602). New York: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson W, & Durbin CE (2010). Effects of paternal depression on fathers’ parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 167–180. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung WJ, Sandberg JF, Davis-Kean PE, & Hofferth SL (2001). Children’s time with fathers in intact families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 63, 136–154. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00136.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotor AJ, Robinson TW, Runyan DK, Barr RG, & Murphy RA (2011). The emergence of spanking among a representative sample of children under 2 years of age in North Carolina. Frontiers in Psychiatry: Child and Neurodevelopmental Psychiatry, 2, 1–8. 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]