Abstract

Therapies that synergistically stimulate immunogenic cancer cell death (ICD), inflammation, and immune priming are of great interest for cancer immunotherapy. However, even multi-agent therapies often fail to trigger all of the steps necessary for self-sustaining anti-tumor immunity. Here we describe self-replicating RNAs encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles (LNP-replicons), which combine three key elements: (1) an LNP composition that potently promotes ICD, (2) RNA that stimulates danger sensors in transfected cells, and (3) RNA-encoded IL-12 for modulation of immune cells. Intratumoral administration of LNP-replicons led to high-level expression of IL-12, stimulation of a type I interferon response, and cancer cell ICD, resulting in a highly inflamed tumor microenvironment and priming of systemic anti-tumor immunity. In several mouse models of cancer, a single intratumoral injection of replicon-LNPs eradicated large established tumors, induced protective immune memory, and enabled regression of distal uninjected tumors. LNP-replicons are thus a promising multifunctional single-agent immunotherapeutic.

Although checkpoint blockade therapies have demonstrated the potential of the immune system to achieve durable cancer regression, only a minority of patients exhibit complete responses1–3. Treatments that prime de novo T cell responses against tumors are thus of interest for their potential to increase immunotherapy response rates and synergize with checkpoint blockade. Successful anti-tumor immunity is thought to be linked to the induction of a self-sustaining “cancer-immunity cycle”, where immunogenic destruction of cancer cells and activated dendritic cells initially leads to priming of anti-tumor T cell responses in draining lymph nodes. These T cells then traffic to disease sites and, together with other immune cells, promote continued cancer cell killing and remodeling of the tumor microenvironment (TME)4. However, a series of interlinked events are needed to initiate this cycle – including induction of immunogenic cancer cell death, activation of dendritic cells, recruitment of immune cells tο the tumor bed, reversion of immunosuppressive cues in the TME, and production of pro-immunity inflammatory factors. Therapeutically inducing all of these changes in tumors remains a challenge.

“In situ vaccination” therapies that utilize the tumor itself as a source of antigen to drive the cancer-immunity cycle are an attractive approach as such treatments obviate the need to explicitly identify antigen targets within the tumor, and a number of such strategies are in preclinical and clinical testing5–9. The initiation of ICD and tumor microenvironment remodeling via the delivery of nucleic acids encoding immunomodulatory genes is one promising approach toward in situ vaccination. Examples include delivery of genetic payloads using oncolytic viruses10, viral replicon particles11,12, or in vitro-transcribed mRNA13. However, these approaches often only elicit high levels of curative responses when treating early stage and/or highly inflamed tumors.

We hypothesized that there could be advantages to an approach based on concepts from non-viral gene delivery, where an engineered nucleic acid payload is packaged in a synthetic nanoparticle to protect the payload and promote its entry into target cells. Ionizable lipid formulations that electrostatically complex with nucleic acids and form lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) to promote cytosolic delivery of DNA or RNA have been used extensively for the delivery of siRNA, mRNA, and DNA into cells, with successful translation to clinical applications14. However, LNPs are also often toxic and can promote cell death15. In the setting of in situ vaccination, we envisioned that the tendency of ionizable lipids to promote cell death could be exploited to create a carrier formulation that not only promotes intracellular delivery of a nucleic acid payload, but also actively promotes immunogenic cancer cell death. Here we show that an ionizable lipid formulation encapsulating self-replicating RNAs (replicons) that encode a cytokine fusion protein is able to successfully combine robust immunogenic cancer cell death, inflammatory cytokine expression, and innate immune stimulation following intratumoral injection. A single administration of LNP-replicons encoding IL-12 led to rejection of large established tumors. Fusion of IL-12 to the matrix-binding protein lumican helped avoid toxicity by virtue of enhanced retention of the cytokine in the tumor microenvironment via the lumican domain. The strong synergy of lipid-mediated tumor cell transfection and ICD with replicon-mediated gene expression and innate immune stimulation provides a facile strategy for promoting anti-tumor immunity and immune memory.

Results

Nanoparticles incorporating an ionizable lipid deliver replicon RNA into cancer cells, leading to payload gene expression, activation of innate immunity pathways, and immunogenic cell death

We sought to test whether a synthetic gene delivery formulation comprised of lipids and nucleic acids could be used to synergistically promote expression of an exogenous payload gene, innate immune stimulation, and immunogenic cell death (Fig. 1a). As a nucleic acid cargo, we selected an alphavirus-derived self-replicating RNA (replicon), where the viral structural proteins are replaced by a cargo gene of interest. We recently engineered a Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis virus-derived replicon with mutations identified by an in vitro evolution strategy to achieve higher and more durable expression from its subgenomic promoter while retaining the innate immune stimulatory properties of the RNA16. We first encoded on this mutant replicon a reporter gene green fluorescent protein (GFP) and encapsulated the engineered replicon into several different lipid formulations including commercial lipofectamine, a DOTAP-containing formulation we previously employed for in vivo replicon delivery16, and a formulation containing an ionizable lipid called TT3 we previously developed for mRNA delivery17 (Supplementary Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1a-g). When added to murine B16F10 melanoma cells in vitro, TT3 LNPs uniquely among these formulations triggered signs of cell death following 1 day (Fig. 1b) and led to killing of nearly all of the cells by 3 days (Fig. 1c). Early signatures of cell death were synergistically increased when either an active or point mutant non-functional replicon was encapsulated in TT3 LNPs (TT3-Rep or TT3-deRep, respectively) compared to “empty” TT3 LNPs (TT3) or naked replicon RNA electroporated into the cancer cells (Electro-rep). Maximal cell killing after 3 days was achieved when an active replicon (TT3-Rep) was delivered by the particles. Despite the rapid onset of cell death, analysis of reporter gene expression 12 hr after addition of LNPs revealed that ~56% of TT3 LNP-treated cells were expressing GFP, with the majority of these transfected cells expressing high levels of the subgenomic promoter transgene (Fig. 1d). Hallmarks of ICD including cell surface calreticulin18, extracellular ATP19–21, and extracellular HMGB122,23 were all elevated within 1 day of treatment of B16F10 cells with TT3-Rep (Fig. 1e-g). Robust ICD induction by TT3-Rep particles was also observed in several human cancer cell lines (Extended Data Fig. 2a-c).

Figure 1 |. Lipid nanoparticle-replicon formulations induce high levels of payload gene expression and immunogenic cell death.

a, Design of lipid nanoparticle/replicon system comprised of a cancer cell-killing lipid formulation encapsulating self-replicating RNA encoding an immunomodulatory gene payload. ICD: immunogenic cell death, TME: tumor microenvironment, TAA: tumor associated antigen. b, Percentages of PI+Annexin V+ B16F10 cells one day post treatment with DOTAP nanoparticles (DOTAP), Lipofectamine (Lipo), TT3 nanoparticles (TT3), Electroporation, DOTAP, Lipo, or TT3 nanoparticles encapsulating replicon RNA (DOTAP-Rep, Lipo-Rep, TT3-Rep) or mutant dead replicon (DOTAP-deRep, Lipo-deRep, and TT3-deRep), or treated with electroporation in the presence of replicon RNA or dead replicon (Electro-Rep and Electro-deRep, respectively). Lipid nanoparticle formulations were added at 10 μg/mL RNA (corresponding to 100 μg/mL TT3 lipids). Shown are mean (box) of different treatments from 3 technical cell culture replicates from one of two independent experiments. c, Viability of B16F10 cells after 3 days incubation with LNP or RNA treatments as indicated (RNA, naked replicon RNA). Shown are mean (box) of different treatments from 3 technical cell culture replicates from one of two independent experiments. d, GFP expression in B16F10 cells at 12-hours post treatment with indicated formulations. Shown are representative flow cytometry plots and mean (box) frequencies of transfected cells from 3 technical cell culture replicates in a single experiment. e-g, B16F10 cells were treated as indicated. Shown are percentages of CRT+ cells (e) and levels of extracellular ATP (f) and HMGB1 (g) at 1 day post transfection. Shown are mean (box) of different treatments from 3 technical cell culture replicates from one of two independent experiments. h-i, HEK-blue TLR reporter and RAW-Lucia-ISG cells were transfected with nanoparticles with or without encapsulated replicon RNA (10 μg/mL RNA). TLR2, 3, 4, 7 and 9 activation as indicated by secreted alkaline phosphatase reporter was assessed by absorbance (h) and secretion of luciferase for Raw-Lucia-ISG was determined by luminescence (i). Shown are mean (box) of different treatments from 3 technical cell culture replicates from one of two independent experiments. j, Quantitative analysis of Stat1, Stat2, IRF9, IRF3, and cGAS mRNA transcripts by qPCR in B16F10 cells at 12 hours post transfection with formulations as indicated. Shown are mean (box) of different treatments from 3 technical cell culture replicates from one of two independent experiments. The source data of Fig. 1a-1j are found in Li_SourceData_Fig.1.

To gain insight into the engagement of innate immune sensing pathways by TT3-Rep particles, we assessed activation of a panel of TLR (Toll-like receptor) reporter cells: TT3 LNPs carrying active or “dead” replicons triggered Toll-like receptor-3 and interferon stimulated genes (ISGs, Fig. 1h-i, Supplementary Table 2). B16F10 cancer cells expressed low levels of TLR3 at steady state, but significantly upregulated both TLR3 and expression of the nucleic acid sensor MDA-5 in response to LNPs carrying replicon (Extended Data Fig. 2d). However, reporter cells expressing or lacking MDA-5 showed equivalent activation of type I interferon in response to TT3-Rep treatment, suggesting that MDA-5 is not required for activation of interferon responses arising from LNP-replicon recognition (Extended Data Fig. 2e). Since TLR3 signaling through TRIF (TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β) for type I interferon production24 leads to activation of the ISG factor 3 (ISGF3) complex25, we assayed mRNA transcript levels of the ISGF3 components STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9, as well as the STING pathway genes, IRF3 and cGAS by qPCR in B16F10 cells. TT3 nanoparticles encapsulating Rep or deRep substantially increased the levels of STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9 expression over untreated controls, but showed no effect on IRF3 and a weaker effect on cGAS (Fig. 1j). Altogether, these data suggest that TT3-Rep particles are capable of transfecting cells for a burst of payload gene expression, while simultaneously activating innate immune sensing pathways and inducing robust immunogenic cell death in cancer cells.

LNP-replicons transfect tumor cells and promote immunogenic cell death in vivo

We next evaluated the effect of intratumorally administering TT3-Rep in the aggressive B16F10 melanoma model. We first used replicons encoding mCherry as a reporter gene to establish the effects of the LNP/Replicon in the absence of a therapeutic gene payload (hereafter, for clarity we refer to the TT3 particles as LNPs and indicate the subgenome payload in parentheses, e.g., LNP-Rep(mCherry)). A single injection of LNP-Rep(mCherry) or LNP-deRep (mCherry) into large established B16F10 tumors induced a delay in tumor progression and extended survival (Fig. 2a-b). By contrast, empty LNPs elicited no tumor regression or survival benefit (Fig. 2a-b). These findings suggest that immunogenic cell death induced by the LNP alone was insufficient to impact large tumors, but when combined with innate immune stimulation provided by the replicon RNA (LNP-Rep and LNP-deRep), could provide a modest therapeutic benefit even without expression of a therapeutic payload. Replicon treatment induced a large influx of granulocytes into tumors (Fig. 2c). In addition, monocytes, NK cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells were recruited to treated tumors, with greater infiltration when the LNPs carried active replicons (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 3a, though this enhanced infiltration did not translate to increased therapeutic benefit compared to LNPs carrying “dead” replicon RNA). Injection of LNP-Rep(mCherry) where the RNA was labeled with Cy5 showed at 12 hr post injection that uptake of the particles was primarily in myeloid cells and CD45- cancer cells but expression of the mCherry cargo gene was primarily found in transfected cancer cells (Fig. 2e-f and Extended Data Fig. 3a). While large B16F10 tumors contained a substantial necrotic core, intratumoral LNP-Rep(mCherry) treatment increased cell death and induced calreticulin exposure on dying cells (Fig. 2g-h and Extended Data Fig. 3b). LNP-Rep(mCherry) administration was also accompanied by a burst of type I interferon expression in tumors and the upregulation of ISGF3 transcripts (Fig. 2i, j). Thus, similar to our findings in vitro, TT3 LNP-replicons both transfected tumor cells in vivo and induced immunogenic cancer cell death.

Figure 2 |. TT3 lipid nanoparticles carrying replicon RNA induce immunogenic cell death and immune infiltration of tumors in vivo.

a-b, Groups of C57Bl/6 mice were inoculated with 106 B16F10 cancer cells in the flank and treated when tumors reached 50 mm2 with a single injection of empty LNP (n=8 mice/group), 10 μg LNP-Rep (n=9 mice/group), 10 μg LNP-deRep (n=9 mice/group), or left untreated (n = 8 mice/group). Shown are average tumor growth (mean ± s.d.) (a) and overall survival (b) over time. c-d, Enumeration (mean ± s.e.m.) of tumor-infiltrating granulocytes (c) and other leukocyte populations (d) 3 days after injection of various formulations as indicated (n = 5 mice/group). e, Uptake (mean ± s.e.m. from n = 5 mice/group) of Cy5-labeled TT3 LNP-Rep by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and cancer cells assessed by flow cytometry 12 hr post injection. f, Expression (mean ± s.e.m. from n = 5 mice/group) of mCherry 12 hours post injection in CD45- cancer cells and TILs. g, Cell viability (mean ± s.e.m. from n = 5 mice/group) in tumors 3 days after TT3 LNP-Rep injection. h, Percentages (mean ± s.e.m. from n = 5 mice/group) of CRT+ cells in tumors at 1 and 3 days post injection as indicated. i, IFN-α2 expression (mean ± s.e.m. from n = 5 mice/group) in tumors at day 1 and day 3 post injection of LNP-Rep as measured by ELISA. j, qPCR analysis (mean ± s.d. from n = 8 (4 mice/group and two technical replicates/mouse) of Stat1, Stat2, IRF9, IRF3, and cGAS mRNA transcripts in tumors at 1 day post LNP-Rep injection. P values were determined by one-sided Tukey’s multiple comparison test (Fig. 2a), or by Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) test (Fig. 2b), or by one-way (Fig. 2c) or two-way (Fig. 2d, 2e, 2f, 2h, 2i and 2j) ANOVA analysis, or by two-sided Student’s T-test (2g) using GraphPad PRISM Software and exact P values were indicated. The source data of Fig. 2a-2j are found in Li_SourceData_Fig. 2.

LNP-replicons encoding a matrix-binding IL-12 molecule remodel the tumor microenvironment and elicit potent tumor rejection

To enhance the anti-tumor activity of the LNP-replicon, we tested the introduction of two different forms of IL-12 as candidate payload genes. We recently generated recombinant IL-12-alb-lumican, a fusion of a single-chain IL-12 with the collagen-binding protein lumican, employing albumin as an expression-promoting spacer. Intratumoral injection of IL-12-alb-lumican protein elicited potent anti-tumor immunity, while avoiding the systemic toxicity of parental IL-12-alb via enhanced retention in tumors through binding to the tumor extracellular matrix26. Motivated by these findings and the roles of IL-12 in stimulating CD4, CD8, and NK cells27, we compared the effects of replicons encoding IL-12-alb-lumican or IL-12-alb vs. mCherry. Substantial levels of IL-12 could be detected in the supernatants of B16F10 cells transfected in vitro with IL-12-encoding replicons, and IL-12-alb-lum produced from replicon-transfected cells bound to collagen as expected (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 4a). Following injection in B16F10 tumors, both forms of IL-12 expressed at high levels for several days, though IL-12-alb was detected at ~8-fold higher levels (Fig. 3b). Animals treated with LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) but not LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb-lum) exhibited elevated serum levels of IL-12, IFN-γ and a number of other cytokines and chemokines for at least 3 days after injection, coincident with transient weight loss (Fig. 3c-d). However, serum levels of liver enzymes (ALT, AST) remained within normal ranges (Extended Data Fig. 4b-c). Treatment with both IL-12-encoding replicons induced a massive influx of granulocytes into tumors, together with substantial increases in CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3e). The three LNP-Rep treatments also induced upregulation of a broad range of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in tumors, and the IL-12-encoding replicons particularly elicited IFN-γ production, which is directly induced by IL-12 (Fig. 3f, Extended Data Fig. 4d). Histological analysis of tumors treated with LNP-Rep(mCherry) or LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) showed a striking collapse of the vasculature in the core of B16 tumors, though vessels remained intact at the tumor periphery (Fig. 3g). Thus, LNP-replicon treatment induced a major remodeling of the tumor microenvironment.

Figure 3 |. LNP-replicons encoding IL-12-alb or IL-12-alb-lum remodel the tumor microenvironment.

a, 0.5×106 B16F10 cells were transfected with LNP-Rep encoding mCherry, IL-12-alb, or IL-12-alb-lum and cultured in 1 ml media. Shown are concentrations (mean ± s.e.m.) of IL-12 (ng/ml) in the supernatants of 3 technical cell culture replicates at 24 hr from one of two independent experiments. b-g, C57Bl/6 mice (n = 5 mice/group) were inoculated with B16F10 tumors and treated with LNP-Rep encoding mCherry, IL-12-alb, or IL-12-alb-lum when tumors were ~50 mm2 as in Fig. 2. b, IL-12 levels (mean ± s.e.m.) in tumors were assessed at 1, 3, or 7 days post replicon injection. c, Cytokines and chemokine in serum at 1 and 3 days post injection with LNP-Reps encoding mCherry, IL-12-alb, or IL-12-alb-lum as measured by Luminex ELISA. d, Changes in body weight (mean ± s.e.m.) over time post tumor inoculation. e, Immune composition (mean ± s.e.m.) of leukocytes in tumors at day 3 post replicon injection. f, Luminex analysis of protein expression in tumors at 1 and 3 days post replicon injection. Shown are clustered protein levels as a heat map. g, Representative images of tumor sections at 3 days post replicon injection as indicated from one of two independent experiments. Shown is staining for nuclei (DAPI, blue) and CD31 (green). Red boxes at left highlight regions in the interior and border of the tumors shown in the high magnification images at right. Scale bars used in global and zoom in images are 1000 and 100 μm as indicated. P values were determined one way (Fig. 3a) or two way (Fig. 3b, 3e) ANOVA analysis or one-sided Tukey’s multiple comparison test (Fig. 3d) using GraphPad PRISM Software and exact P values were indicated. The source data of Fig. 3a-3f are found in Li_SourceData_Fig. 3. The source data of Fig. 3g are stored in Figshare42.

Strikingly, a single injection of IL-12 replicons into large established B16F10 tumors induced tumor rejection and long-term survival in a majority of animals (Fig. 4a-b). Similar high levels of complete responses were observed for YUMMER1.7 melanomas driven by mutant Braf and Pten loss and CT26 colon carcinomas (Fig. 4c-f). In contrast, repeated intratumoral injection of recombinant IL-12-alb-lum protein, which we have previously shown to delay tumor progression as a monotherapy, here prolonged survival but elicited no cures (Extended Data Fig. 5a-b). This data suggests that IL-12 signaling alone is insufficient for tumor rejection. We noted that for tumors such as CT26 that had a lower complete response rate following a single dosing with LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb-lum), repeat dosing increased the frequency of complete tumor rejections (Extended Data Fig. 5c-d). As replicons encoding IL-12-alb outperformed IL-12-alb-lum in some of these models, we hypothesized this reflected the more efficient expression of the IL-12-alb transgene (Fig. 3b). Titrating the dose of LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb), we found that 1.25 μg of this LNP-Rep gave intratumoral IL-12 expression levels in tumor matched to that achieved by 10 μg IL-12-alb-lum replicon RNA (Extended Data Fig. 5e). A head-to-head comparison of the two replicon constructs under these dose-matched conditions revealed a trend toward enhanced therapeutic efficacy for replicons encoding matrix-binding IL-12 (Extended Data Fig. 5f-g).

Figure 4 |. A single injection of LNP-replicons encoding IL-12-alb or IL-12-alb-lum can eradicate large established tumors.

a-f, Tumor area (mean ± s.e.m.) (a, c, e) and mouse survival (b, d, f) over time after one intratumoral injection of 10 μg LNP-replicon into ~50 mm2 B16F10 (a-b, Untreated n=10 mice/group, LNP-Rep n=9 mice/group, LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) n=12 mice/group, LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb-lum) n=11 mice/group), YUMMER1.7 (c-d, Untreated n=7 mice/group, LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb-lum) n=8 mice/group), or CT26 tumors (e-f, Untreated n=7 mice/group, LNP-Rep n=7 mice/group, LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) n=8 mice/group, LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb-lum) n=8 mice/group), respectively. P values were determined by one-sided Tukey’s multiple comparison test (Fig. 4a, 4e), or by one-sided Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) test (Fig. 4b, 4d, and 4f) using GraphPad PRISM Software and exact P values were indicated. The source data of Fig. 4a-4f are found in Li_SourceData_Fig. 4.

The efficacy of intratumoral immunotherapy in treating metastatic cancer is predicated on the development of a systemic anti-tumor immune response to eliminate tumors that are not directly treated. To evaluate systemic immunity, B16F10 tumors were inoculated on opposite flanks of mice, followed by a single injection of LNP-Rep in one tumor (Fig. 5a). Animals were simultaneously treated with systemic anti-PD-1 therapy, mimicking a likely clinical scenario where checkpoint blockade is standard of care and can be used to enhance the efficacy of newly primed systemic T cell responses. In this setting, both LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) and LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb-lumican) induced regression of both treated and untreated tumors, but a greater proportion of complete responses was obtained with the IL-12-alb construct, likely due to the higher intratumoral levels achieved for IL-12-alb compared to IL-12-alb-lumican (Fig. 5b-d). In the absence of anti-PD-1 co-treatment, a single dose of LNP-Rep still elicited substantial anti-tumor activity in the two-tumor model, though with slightly fewer long-term survivors (Extended Data Fig. 5h-j). To assess the capacity of local therapy to eliminate metastases, we injected 0.25 million B16F10 cells intravenously 2 days after implantation of 106 B16 cells in the flank. The flank tumors were then treated with a single i.t. injection of LNP-Rep(IL-12) when they reached ~50 mm2 in size (Fig. 5e). Untreated tumors reached euthanasia criteria on day 15 (Fig. 5f); the lungs of these animals showed numerous large tumor nodules at sacrifice (Fig. 5g-h). By contrast, LNP-Rep-treated animals were sacrificed at day 30, when the treated flank tumors had disappeared. At this time point, few if any small tumor nodules were detected in the LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) group and very low tumor burden was detectable in animals treated with LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb-lum) (Fig. 5g-h). These results indicate the potential of LNP-Rep(IL-12) to induce protective systemic immunity in tandem with ablation of the injected lesion.

Figure 5 |. Local LNP-replicon therapy regresses distal untreated tumors and eliminates metastases.

a-d, C57Bl/6 mice (Untreated n=7 mice/group, Untreated + α-PD1 n=8 mice/group, LNP-Rep (IL-12-alb) n=8 mice/group, LNP-Rep (IL-12-alb-lum) + α-PD1 n=8 mice/group) were inoculated s.c. with 106 and 0.3×106 B16F10 cells in the left and right flanks, respectively. When the left flank tumor reached ~50 mm2 in size, this lesion was injected with 10 μg of the indicated LNP-replicon and systemic anti-PD-1 antibody was initiated, dosed every 3 days. Shown is the experimental setup (g), tumor area (mean ± s.d.) in each flank (h, i), and animal survival over time (j). e-h, C57Bl/6 mice (Untreated (s.c.) n= 12 mice/group, Untreated (s.c. + i.v.) n= 12 mice/group, LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) (s.c.) n= 10 mice/group, LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb-lum) (s.c.) n= 10 mice/group) were injected with 1 million B16F10 cells s.c. in the flank. Two days later, an additional 0.25 million B16F10 cells were injected i.v. On day 7, flank tumors were injected with 10 μg LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) or LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb-lum) as indicated. Shown is the experimental setup (e), tumor area (mean ± s.d.) of the treated flank tumor (f), enumeration of tumor nodules (mean ± s.e.m.) in the lungs at the indicated times (g), and representative images of lungs at indicated time points (h). Scale bars (1 cm) are as indicated. P values were determined by one-sided Tukey’s multiple comparison test (Fig. 5b, 5c, and 5f), or by one-sided Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) test (Fig. 5d), or by one way ANOVA analysis (Fig. 5g) using GraphPad PRISM Software and exact P values were indicated. The source data of Fig. 5b-5d, 5f-5g are found in Li_SourceData_Fig. 5. Source data of Fig. 5h are found in SourceData_Li_Fig.5h-Lungimages.pdf and also stored in Figshare43.

LNP-Rep(IL-12) therapy induces a protective T cell response and depends on STING and Myd88 signaling in host cells for efficacy

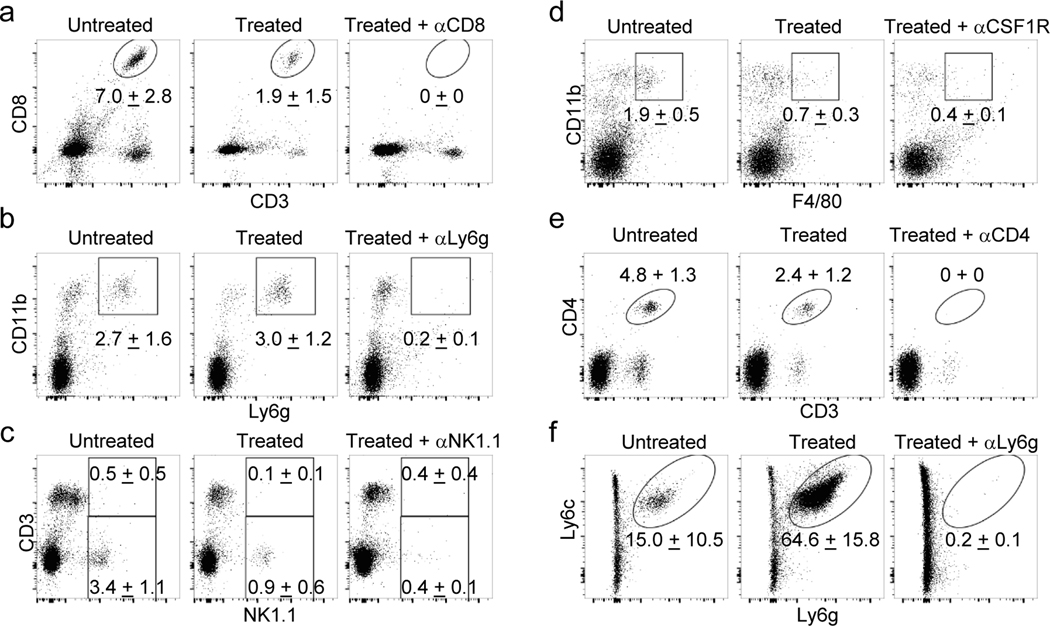

To evaluate the role of different lymphocyte populations on treatment efficacy, LNP-Rep therapy was carried out in animals treated with antibodies to deplete different cell populations (Extended Data Fig. 6a-f). Depletion of NK cells, granulocytes, or macrophages during therapy had minor effects on the outcome of treatment with IL-12-alb-lum replicons (Fig. 6a-b). CD4+ cell depletion led to slightly enhanced therapeutic responses to LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb-lum) treatment, likely due to elimination of regulatory T cells (Fig. 6c-d). By contrast, efficacy was highly dependent on CD8+ T cells, as CD8 depletion led to limited tumor regression and no long-term survivors (Fig. 6c-d). In addition, mice that had rejected primary tumors following LNP-Rep therapy also rejected cancer cells on re-challenge, and CD8+ T cells were critical for the rejection (Fig. 6e and Extended Data Fig. 7a). Induction of CD8+ T cell responses is driven by the action of cross-presenting cDC1 dendritic cells. LNP-Rep treatment with or without an effector gene payload was accompanied by an increase in migratory CD11c+CD11b-MHC-II+CD24+CD64-CD103+XCR1+ cDC1 cells in the tumor-draining lymph nodes (TDLNs) 24 hr after injection (Fig. 6f and Extended Data Fig. 8a). Co-culture of lymph node cells with Pmel T cells expressing a transgenic T cell receptor recognizing the melanoma antigen gp100 revealed a marked elevation in tumor antigen presentation in the TDLNs one day after treatment with LNP-Rep encoding either form of IL-12 (Fig. 6g and Extended Data Fig. 8b). Consistent with an important role for antigen presentation by these cells, the efficacy of LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) treatment was largely abrogated in Batf3−/− animals lacking cDC1 cells (Fig. 6h and Extended Data Fig. 7b). Dying cancer cells are known to activate STING in host dendritic cells28 and release of HMGB1 can activate Myd88 innate immune signaling in host cells9. Interestingly, maximal LNP-Rep efficacy required these pathways, as revealed by loss of tumor control in Myd88−/− and STING−/− hosts (Fig. 6i-j). Altogether, these results indicate that LNP-Rep(IL-12) treatment triggers DC migration and antigen presentation in TDLNs, priming a systemic anti-tumor T cell response that is important for durable complete responses to therapy.

Figure 6 |. Cellular and molecular pathways governing LNP-replicon therapeutic efficacy.

a-d, C57Bl/6 mice bearing B16F10 tumors (a-b, Untreated n=9 mice/group, Treated n=10 mice/group, Treated + α-NK1.1 n=9 mice/group, Treated + α-Ly6g n=10 mice/group, Treated + α-CSF1R n=10 mice/group; c-d, n=10 mice/group) were administered the indicated depleting antibodies beginning one day prior to injection with 10 μg LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb-lum) and every 3 days thereafter. Shown are tumor areas (mean ± s.e.m.) (a, c) and mouse survival over time (b, d). e, Mice treated as in Fig. 3h that rejected their primary tumor (n=9 mice/group) were rechallenged with 0.1×106 B16F10 cells, and observed for survival. f, Mice bearing B16F10 tumors (n=5 mice/group) were treated as in Fig. 3h, and cDC1 (mean ± s.e.m.) were enumerated in TDLNs 1 day after replicon injection. g, Mice bearing B16F10 tumors (n=4 mice/group) were treated as in Fig. 3h, and 3 days post replicon injection, TDLN cells were recovered and co-cultured with Pmel reporter CD8 T cells. Shown is CD69 (mean ± s.e.m.) upregulation on responding pmel CD8 T cells. h-j, B16F10 cancer cells were inoculated in WT, Batf3−/−, Myd88−/−, or STING−/− mice (h, B6-Untreated n=5 mice/group, B6-LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) n=7 mice/group, Batf3−/−-Untreated n=5 mice/group, Batf3−/−- LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) n=6 mice/group; i-j, B6-Untreated n=7 mice/group, B6-LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) n=8 mice/group, Myd88−/−-Untreated n=6 mice/group, Myd88−/−-LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) n=6 mice/group, STING−/−-Untreated n=8 mice/group, STING−/−-LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) n=9 mice/group), and treated when tumors reached 50 mm2 with a single injection of the indicated LNP-replicons. Shown is tumor area (mean ± s.e.m.) or animal survival over time. P values were determined by one-sided Tukey’s multiple comparison test (Fig. 6a, 6c, and 6i), or by one-sided Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) test (Fig. 6b, 6d, 6e, 6h, and 6j), or by one way ANOVA analysis (Fig. 6f and 6g) using GraphPad PRISM Software and exact P values were indicated. Source data of Fig. 6a-6j are found in Li_SourceData_Fig. 6.

Discussion

Here we show that a lipid nanoparticle formulation of self-replicating RNAs can effectively induce an efficient tumor killing cycle by combining robust immunogenic cancer cell death with immunostimulation derived from innate recognition of the RNA and expression of IL-12 as a potent driver of anti-tumor T cell responses. Cancer cell killing by LNP-replicons was accompanied by TLR3 and type I interferon signaling, which have previously been shown to be an important component of productive immunogenic cell death29. A single injection of LNP-replicons was capable of eradicating large established tumors in several syngeneic tumor models, and induced systemic anti-tumor immunity leading to elimination of distal untreated tumors.

The potent anti-tumor activity of IL-12 in preclinical models has motivated a diverse array of strategies to deliver this cytokine in tumors. To obtain sustained exposure, strategies based on local expression of IL-12 from intratumorally-administered DNA or viral vectors have been extensively investigated30–36. Early preclinical and clinical studies reported no notable toxicities from DNA-delivered IL-12, but expression levels measured in tumors were very low and anti-tumor activity was modest32–34. The replicon platform described here achieved much higher levels of IL-12 in tumors than reported in these prior studies, which we expect to enhance efficacy but also raise the potential for toxicity: in clinical studies where recombinant protein or more potent expression vectors have been used in patients, high levels of intratumoral IL-12 have correlated with dissemination of cytokine into the blood35,37, leading to induction of high levels of systemic IFN-γ and toxicities35. To counter this issue, we recently reported an approach to prevent leakage of therapeutics from the TME by fusing cytokines to the natural collagen-binding protein lumican26. This approach effectively promoted retention of IL-12 in tumors when administered as recombinant protein. Here we show that this strategy is also effective in enhancing the safety profile of LNP-replicon-expressed IL-12 and is equally or more effective in tumor rejection than replicon-encoded “free” IL-12 when expression levels are normalized, suggesting an approach that may be useful in a variety of gene delivery vectors.

Preclinical studies of treatments focused solely on delivery of IL-12 have generally reported therapeutic success only in treating tumor burdens substantially smaller than reported here, likely due to the inability of a single cytokine to drive all aspects of the cancer-immunity cycle29,30,32–34. Similarly, we found that single injection of LNP-rep(IL-12-alb-lumican) was more effective in treating large tumors than repeated injections of IL-12-alb-lumican protein. Clinical trials of oncolytic viruses demonstrate the promise of a therapeutic strategy targeting cancer cell killing together with local cytokine expression38–41. The “synthetic oncolytic virus” used here may have advantages over repurposed natural viruses, as physical tumor cell killing by the lipid nanoparticle vector should be independent of tumor cell type or specific tumor phenotypes.

In summary, we demonstrate here a potent single agent multifactorial strategy for in situ vaccination of tumors, employing a synthetic nanoparticle formulation comprised of engineered self-replicating RNAs delivered by an immunogenic cell death-inducing lipid nanoparticle. By combining rapid immunogenic cancer cell death induced by the LNP, innate immune stimulation, and transient payload gene expression from the replicon RNA, a cascade of rapid tumor microenvironment remodeling and antigen presentation is induced. This leads to a systemic anti-tumor immune attack that can be induced by a single injection in several large established tumor models, which also regresses distal untreated lesions. This approach provides a platform technology for engineering immune rejection of tumors that could be readily adapted to target other immune pathways via the selection of additional/alternate payload genes.

Methods

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper.

Constructs, In Vitro Transcription, Capping/Methylating for Replicon RNA, and Neon Transfection

VEE replicon plasmid DNA was prepared based on mutant constructs previously described16. The sequence of the newly discovered mutant “dead” replicon deRep are shown in Supplementary Table 2. mCherry, EGFP or firefly luciferase were cloned after the subgenomic promoter for reporter constructs to generate reporter constructs as previously described16. IL-12-alb and IL-12-alb-lum fusion payload genes with sequences as previously described26 were cloned after the subgenomic promoter to generate therapeutic replicons. Replicon RNAs were in vitro transcribed (IVT) from the templates of linearized VEE DNA constructs using the MEGAscript™ T7 Transcription Kit (ThermoFisher) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting replicon RNAs were capped and methylated using the ScriptCap™ m7G Capping System and ScriptCap™ 2’-O-Methyltransferase Kit (Cellscript) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA purity was assessed by gel electrophoresis. In vitro transfections were carried out using electroporation with 5 μg RNA per 500,000 cells in 100 μl R buffer using a NEON electroporation kit (ThermoFisher) at 1200 V, 20 milliseconds, and 1 pulse.

Formulations of lipid nanoparticles and encapsulation of replicon RNA.

For encapsulating replicon RNA into DOTAP nanoparticles, a lipid mixture composed of 16.94 μl DOTAP (Avanti, Cat #890890, 10 mg/ml in ethanol), 15.97 μl DSPC (Avanti, Cat# 850365, 3 mg/ml in ethanol), 18.77 μl cholesterol (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# C8667, 6 mg/ml in ethanol), and 13.6 μl DSPE-PEG2000 (Avanti, Cat# 880128, 2.5 mg/ml in ethanol) was prepared to provide a molar ratio of 40:10:48:2 of the 4 lipids. The lipid solution was evaporated under dry nitrogen until one third of the total initial volume remained. Then 10 μg replicon RNA (1 mg/ml) in 11.8 μl of 0.1M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) was added with pipetting, followed by a second addition of an additional 22 μl 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) with pipetting. The mixture was shaken for an hour at 100 rpm on a VWR Standard Analog Shaker and then dialyzed against PBS for another hour at 25°C in a 3,500 MWCO dialysis cassette.

Encapsulating replicon RNA into Lipofectamine™ MessengerMAX™ nanoparticles was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher).

To encapsulate replicon RNA into TT3 nanoparticles, a lipid mixture composed of 10 μl TT3 (10 mg/ml in ethanol) 17, 8.04 μl DOPE (Avanti, Cat# 850725, 10 mg/ml in ethanol), 5.57 μl cholesterol (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# C8667, 10 mg/ml in ethanol), and 3.45 μl C14-PEG2000 (Avanti, Cat# 880150, 2 mg/ml in ethanol) was prepared in 10.44 μl ethanol to attain a molar ratio of 20:30:40:0.75 between the lipids. The mixture was added to 4.17 μl citrate buffer (pH 3.0, 10 mM). Then 10 μg replicon RNA (1 mg/ml) in 31.67 μl citrate buffer (pH 3.0, 10 mM) was added with pipetting. The mixture was dialyzed against PBS for 80 minutes at 25°C in a 3,500 MWCO dialysis cassette.

Transfections of lipid nanoparticles in vitro and in vivo.

For in vitro transfection, 5 μg replicon RNA was formulated in lipid nanoparticles as described above. The formulated nanoparticles were added to 0.5 ml media in a well of 12-well plate with 500,000 cells. At 12, 24, 72 hours post transfection, the cells and supernatants were collected for various assays.

For in vivo transfection, 10 μg replicon RNA was formulated as above and intratumorally injected for various assays in the paper.

Annexin V/PI staining, ATP assay, and HMGB1 analysis.

Annexin V/PI staining was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions (Biolegend, Cat# 640932). Extracellular ATP was assayed by the ENLITEN® ATP Assay System (Promega). HMGB1 levels were measured using the Chondrex HMGB1 kit (Cat #6010) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell lines and Animals.

Cell lines B16F10 (ATCC® CRL-6475™), CT26 (ATCC® CRL-2638™), HEK-blue-TLR2 (Invivogen), HEK-blue-TLR3 (Invivogen), HEK-blue-TLR4 (Invivogen), HEK-blue-TLR7 (Invivogen), HEK-blue-TLR9 (Invivogen), Raw-Lucia ISG (Invivogen), A549-Dual™ Cells (Invivogen), A549-Dual™ KO-MDA5 Cells (Invivogen), A549 (ATCC® CCL-185™), Hela (ATCC® CCL-2™), and SK-MEL-5 (ATCC® HTB-70™) were cultured following vendor instructions. YUMMER 1.7 cells were a gift from Prof. Marcus Bosenberg at Yale University and followed the procedures for culture described previously44. Female C57BL/6J (JAX Stock No. 000664), Balb/C (JAX Stock No. 000651), Pmel Thy1.1 (JAX Stock No. 005023), MyD88−/− (JAX Stock No. 009088), STING−/− (Jax Stock No. 025805), and Batf3−/− (JAX Stock No. 013755) mice 6–8 weeks of age were purchased and maintained in the animal facility at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). All animal studies and procedures were carried out following federal, state, and local guidelines under an IACUC-approved animal protocol by Committee of Animal Care at MIT.

Tumor inoculation and tumor therapy.

One million B16F10, CT26, or YUMMER1.7 cells in 50 μl sterile PBS were subcutaneously (s.c.) injected in the flank of mice. Seven to nine days later when tumors reached 50 mm2 in size, animals were injected intratumorally (i.t.) with PBS (control) or lipid nanoparticles in ~100 μL of PBS as indicated.

Antibodies, Staining, and FACS Analysis.

Antibodies against mouse Ly6c (clone HK1.4), CD11b (clone M1/70), CD11c (clone N418), F4/80 (clone BM8), MHC-II (clone M5/114.15.2), CD45 (clone 30-F11), CD3 (clone 17A2), CD4 (clone GK1.5), CD4(clone H129.19), CD8 (clone 53–6.7), NK1.1 (clone PK136), NK1.1 (clone S17016D) CD45.2 (clone 104), CD24 (clone 30-F1), XCR1 (clone ZET), CD64 (clone X54–5/7.1), Thy1.1 (clone Ox-7), Th1.2 (clone 30-H12), CD69 (clone H1.2F3), CD31 (clone MEC13.3) were from Biolegend. Antibodies against mouse Ly6g (clone 1A8), CD16/32 (clone 2.4G2) and CD103 (clone M290) were from BD Biosciences. All of the antibodies from Biolegend and BD Biosciences are diluted as 1:100. Antibodies against mouse Calreticulin (Cat. No. ab196159) were from Abcam (diluted as 1:300). The live/dead dye Aqua (Cat. No. L34966) was from ThermoFisher (diluted as 1:300).

Tumor-bearing mice were sacrificed and the tumors were sliced and digested by collagenase IV (1 mg/ml, Thermo Scientific Cat. 17104019) for one hour at 37°C, and tumor draining lymph nodes were ground to make single cell suspensions. The single cells suspensions were filtered by 70 μm nylon strainers and stained as described45. Stained samples were analyzed using a FACS analyzer (LSR-II or LSR-II-Fortessa) from BD Biosciences. All flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Flowjo LLC).

Elisa and Luminex analysis.

Tumors were collected and ground in tissue protein extraction reagent (T-PERTM, Thermo Scientific, Cat. No. 78510) in the presence of 1% proteinase and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Scientific Cat. No. 78442). The lysates were incubated at 4°C for 30 minutes with slow rotation then centrifuged to remove debris. The supernatants were transferred to a clean tube for ELISA or Luminex analysis. IFN-α2, IL-12, and IFN-γ in tumor tissue supernatants or in serum were measured by ELISA kits from Abcam (Cat. No. ab215409) and ThermoFisher (Cat. No. 88–7121-88, IL-12; Cat#88–7314-88, IFN-γ), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Part of the supernatants were sent to Eve Technology for Luminex analysis. Cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors were measured by luminex and levels were clustered by Cluster 3.0 developed by Michael Eisen at Stanford University46. The supernatants of the cells transfected in vitro were for detections of IL-12 and HMGB-1 as described above, for Collagen I binding assay as described26.

Immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, image, and processing.

Tumors with different treatments were necropsied and incubated overnight on swivel shaker in 50 mM pH7.4 Phosphate buffer with 1% paraformaldehyde, 100 mM Lysine, 2 mg/ml sodium periodate. The samples were washed in PBS for 10 minutes in room temperature for three times. The samples were incubated in PBS with 30% sucrose on swivel shaker for 6–10 hours, then quickly rinsed in PBS and dried completely with a paper towel. Samples were embedded in OCT in tissue cassettes and frozen on dry ice for cutting as 8–10 μm sections on slides. The slides were dried in room temperature for at least 60 minutes, then washed for 5 minutes three times, dried on paper towels and incubated in Rat Immunomix (PBS with 10% Rat serum, 0.05% sodium azide, 0.5% Triton-X-100, and 2 mg/ml BSA for 30 minutes). Then sections were applied in Rat Immunomix overnight with primary antibody anti-CD31 (clone MEC13.3, 1:100). Slides were washed in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 for 5 minutes three times, washed in PBS for 5 minutes once and fixed in PBS with 1% paraformaldehyde for 2 minutes, washed twice in PBS for 5 minutes and covered by VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Lab, Cat. No. H-1200–10). The stained slides were imaged using a DeltaVision™ Ultra microscope from GE Life Sciences and the images were processed by NIH Image J.

CryoTEM.

DOTAP lipid nanoparticles (DOTAP), DOTAP lipid nanoparticles encapsulated replicon RNA (DOTAP-Rep), TT3 lipid nanoparticles (TT3), TT3 lipid nanoparticles encapsulated replicon RNA (TT3-Rep) were prepared as above. Three μL of DOTAP, DOTAP-Rep, TT3, TT3-Rep, and buffer containing solution was dropped on a lacey copper grid coated with a continuous carbon film and blotted to remove excess sample without damaging the carbon layer using a Gatan Cryo Plunge III. The grid was mounted on a Gatan 626 single tilt cryo-holder equipped in the TEM column. The specimen and holder tip were cooled by liquid-nitrogen and imaged on a JEOL 2100 FEG microscope operated at 200 kV and with a magnification in the ranges of 10,000~60,000 for assessing particle size and distribution. All images were recorded on a Gatan 2kx2k UltraScan CCD camera.

Liver enzyme measurements.

Serum was isolated from B16F10 tumor bearing mice at 1 and 3 days post treatment. AST and ALT levels were quantified using the Aspartate Aminotransferase activity kit (Sigma Aldrich, Cat. No. MAK055–1KT) and Alanine Aminotransferase activity kit (Sigma Aldrich, Cat. No. MAK052–1KT) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative PCR Analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from cells or tumors transfected with LNP-replicon RNA as indicated and reverse transcribed by a TaqMan® Reverse Transcription Kit (ABI Cat. No. N8080234), followed by amplification with Sybr Green Master Mix (Roche) and specific primers for Stat1 (Cat. No. MP215434), Stat2 (Cat. No. MP215434), IRF9 (Cat. No. MP206708), IRF3 (Cat. No. MP206702), and cGAS (Cat. No. MP214711), from Origene and detected by a Roche LightCycler 480. The Ct values were normalized with housekeeping gene mouse Actin B for comparison.

Depletions.

Depletions of cellular subsets in vivo were carried out using antibodies against CD8α (clone 2.43, BioXCell, 400 μg i.p. twice weekly), NK1.1 (clone PK136, BioXCell, 400 μg i.p. twice weekly), Ly6g (clone 1A8, BioXCell, 400 μg i.p. twice weekly), CSF-1R (clone AFS98, BioXCell, 300 μg i.p. every other day), or CD4 (clone GK1.5, BioXCell, 400 μg i.p. twice weekly) as previously described47.

Activation of Pmel CD8 T cells ex vivo.

Pmel CD8 T cells were isolated from lymph nodes of Pmel Thy1.1 mice using the EasySep™ Mouse CD8+ T Cell Isolation Kit from StemCell Technologies (Cat. No. 19853) following the vendor’s instructions. In parallel, naïve or B16F10 tumor-bearing mice with or without injections of LNP-Rep RNA were sacrificed and inguinal lymph nodes were processed into single cell suspensions. Pmel Thy1.1+CD8+ T cells (0.2×106) were incubated in 12-well plates with 4×106 cells from the test inguinal lymph nodes in 1 ml complete RPMI with 2 ng/ml IL-2 (Peprotech, Cat. No. 212–12). Activation of Thy1.1+ Pmel T cells or endogenous Thy1.2+CD8+ T cells was assessed by flow cytometry one day later using fluorophore conjugated antibodies against CD8α, CD69, Thy1.1, Thy1.2, and live/dead dye Aqua.

Statistics and Reproducibility.

Data were statistically analyzed by one-way or two-way ANOVA, or by Student’s T-test using GraphPad Prism. Based on results from preliminary studies, we used at least n=8 animals/group for tumor growth and survival studies, aiming to obtain 80% power to detect at least a 20% difference between treatment conditions. Animals were randomized to treatment groups once the mean tumor size of 50 mm2 was reached by the tumor-implanted cohort. No data were excluded from the analyses. The Investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment. The samples sizes for in vitro analysis were 3 (triplicates) and for in vivo analysis are annotated in Figure legends. The details of statistical analysis for Figures and Extended Data Figures are included in the Source data files.

Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The source data for Figs. 1–6 and Extended Data Figs. 1–2, Figs. 4-7 have been provided as Source data files. The source data of Fig. 3g are stored in Figshare42. The source data of Fig. 5h are found in SourceData_Li_Fig.5h-Lungimages.pdf and are also stored in Figshare43. The source data for Extended Data Fig. 1d-1g are found in Li_SourceData_ED_Fig.1d-1g, and are also stored in Figshare48. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Comparison of size, zeta potential, RNA encapsulation efficiency, and morphology for the nanoparticles.

a-b, Mean diameter (a) (nm) and Zeta potential (b) (mv) of different nanoparticles with or without encapsulation of replicon RNA (n = 3 /group; error bars are mean ± s.d.). (c) RNA encapsulation efficiency of DOTAP, Lipofectamine, and TT3 nanoparticles (n = 3 /group; error bars are mean ± s.d. n.d. means non-detectabsle. d-g, morphologies of DOTAP and TT3 lipid nanoparticles without (d, f) or with replicon RNA (e, g) were imaged by Cryo-TEM. Shown are representative images from one of two independent experiments. Scale bar (100 nm) is indicated.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Immunogenic cell death in human cancer cells and pathways of interferon stimulation in response to treatments with TT3 or TT3-Rep.

a-c, Human A549 lung carcinoma (a), SK-MEL-5 melanoma (b), or Hela cervical cancer cells (c) were treated with 10 μg/mL empty TT3 LNPs (TT3), TT3 LNPs carrying replicons encoding GFP (TT3-Rep), or left untreated as indicated. Three days post treatment, the percentage of viable cells was enumerated (left column). One day post treatment, the ICD markers extracellular ATP (second column), CRT+ cells (third column), extracellular HMGB1 (fourth column) were measured. d, Twelve hours post treatment of 10 μg/mL TT3 LNP (LNP) or TT3 LNP carrying replicons encoding mCherry (LNP-Rep), levels of MDA-5 and TLR3 mRNA in B16F10 cells were assessed by qPCR. Shown are fold changes of MDA-5 and TLR3 expression in different treatments in comparison to untreated cells normalized by actin B expression. e, One day post treatment of A549 type I interferon reporter cells or MDA-5 knockout A549 reporter cells with 10 μg/mL TT3 LNP (LNP) or TT3 LNP carrying replicons encoding mCherry (LNP-mCherry), the supernatants were collected and incubated to detect stimulation the expression of the luciferase reporter. Shown are relative luminescence units. Throughout error bars are mean ± s.d. from a-c (n = 3 /group), d (n = 6 /group), e (n =4 /group); P values were determined by one way (a, b, c) or two way ANOVA (d, e) using PRISM Software and exact P values were indicated.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Typical gating strategy for FACS analysis.

C57Bl/6 mice bearing established B16F10 tumors and TDLNs were necropsied and prepared as single cells suspension. The cells were stained with antibodies against cell surface makers as indicated and followed with flow cytometry (see methods). a. Shown are typical gating strategies of granulocytes, M-MDSCs, monocytes, macrophages, CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, NK cells, NKT cells, mCherry positive cells in tumor cells for Fig. 2d-2g and Fig. 3e. b. Shown are typical gating strategies of CRT positive cells in SSChi FSChi live tumor cells from B16F10 tumor bearing mice treated without or with LNP-Rep for Fig. 2h.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Treatments of LNP-Rep encoding mCherry, IL-12-alb, or IL-12-alb-lum reprogrammed tumor and systemic microenvironments with low toxicity.

a, IL12-alb-lum produced by LNP-replicon-transfected tumor cells binds to collagen I. B16F10 cells were transfected with LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb-lum) and the supernatants of the transected cells were added to collagen-coated plates for analysis of binding by ELISA in comparison of standards protein IL12-alb-lum. Shown are the ELISA absorbance for IL-12 detection versus concentration of added IL-12-alb-lum using the supernatants of B16F10 cells that were transfected with LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb-lum) or left untreated (error bars are mean ± s.d. from n = 3 /group). b-c, Comparison of AST (b) and ALT (c) levels in serum at day 1 and 3 after the indicated treatments (error bars are mean ± s.e.m. from n = 5 mice/group). d, Comparison of CXCL9 and CXCL10 levels in tumor at day 1 and 3 after the indicated treatments (error bars are mean ± s.e.m. from n = 5 mice/group). P values were determined by two way ANOVA analysis using PRISM Software and exact P values were indicated.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Therapeutic efficacy of LNP-Rep encoding IL-12 in distinct treatment models.

a-b, Groups of C57Bl/6 mice (n=10/group) bearing established B16F10 tumors were treated when tumors reached 50 mm2 with a single injection of 10 μg LNP-rep(IL-12-alb-lum) on day 7 (indicated by red arrows) or with 2.3 μg recombinant IL-12-alb-lum on days 5, 11, and 17 (indicated by blue arrows). Shown are average (mean + s.d.) tumor growth (a) and overall survival (b) over time. c-d, Groups of Balb/c mice bearing established CT26 tumors were treated when tumors reached 50 mm2 with a single injection on day 7 or 3 injections (day 7, 10, 13) of 10 μg LNP-rep(IL-12-alb-lum) start from day 7 (untreated n=6 animals/group, other groups n=8 animals/group). Shown are average (mean + s.e.m.) tumor growth (c) and overall survival (d) over time. e-g, Groups of C57Bl/6 mice bearing established B16F10 tumors were treated when tumors reached 50 mm2 with a single injection of different dosages of the LNP-encapsulated replicon RNA as indicated. Shown are IL-12 levels (mean + s.e.m.) in tumors at one day post injection as measured by ELISA (n=5/group) (e), average (mean + s.d.) tumor growth (f) and overall survival (g) over time with the treatments as indicated (untreated n=6 animals/group, other groups n=8 animals/group). n.d., non-detectable. h-j, C57Bl/6 mice (untreated n=12 mice/group, other groups n=14 mice/group) were inoculated s.c. with 106 and 0.3x106 B16F10 cells in the left and right flanks, respectively. When the left flank tumor reached ~50 mm2 in size, this lesion was injected with 10 μg of the indicated LNP-replicon. Shown is tumor area (mean + s.d.) in each flank (h, i), and animal survival over time (j). P values were determined by one-sided Turkey’s multiple comparison test (Fig. 5f, 5h, and 5i), or by one-sided Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) test (Fig. 5b, 5d, 5g, and 5j) using PRISM Software and exact P values were indicated.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Depletion efficiency in peripheral blood (a-e) and in tumors (f).

C57BL/6J mice bearing B16F10 tumors were administered the indicated depleting antibodies beginning one day prior to injection with 10 μg LNP-Rep(IL12-alb-lum). Then the depletion efficiency in peripheral blood (a-d, Untreated n = 4 mice, treated and untreated n = 5 mice/group; e, n=10 mice/group) and in tumor (f, n=5 mice/group) were determined by flow cytometer. Shown are typical FACS plots from the groups of Untreated, Treated (LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb-lum), and Treated with depleting antibodies as indicated. The mean and standard deviation of gated populations are indicated.

Extended Data Fig. 7. CD8 T cells and Batf3 are critical for therapeutic efficacy.

a, The cured mice lost protection while depletion of CD8 T cells. Mice treated as in Fig. 4b that rejected their primary tumor (Naïve n=12 mice/group, Cured (LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb)) n=14 mice/group, Cured (LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb-lum)) n=14 mice/group) were administered antibodies against CD8a beginning one day prior to rechallenge with 0.1x106 B16F10 cells. Then antibody against CD8a was administrated every 3 days and followed for survival mice were observed. b, B16F10 tumor bearing mice in absence of Batf3 decreases responses to treatment of LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb). Shown are tumor areas over time after intratumoral injection of LNP-Rep encoding IL-12-alb into B16F10 tumors (mean + s.e.m.) in C57BL/6J or Batf3−/− mice (B6-Untreated n=5 mice/group, B6-LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) n=7 mice/group, Baft3−/− -Untreated n=5 mice/group, Baft3−/− -LNP-Rep(IL-12-alb) n=6 mice/group). Throughout, P values were determined by one-sided Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) test (a), or by one-sided Tukey’s multiple comparison test (b) using PRISM Software and exact P values were indicated.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Typical gating strategy for FACS analysis.

C57Bl/6 mice bearing established B16F10 tumors and TDLNs were necropsied and prepared as single cells suspension. The cells were stained with antibodies against cell surface makers as indicated and followed with flow cytometry (see methods). a. Shown are typical gating strategies of conventional DC1 and DC2 in TDLN cell for Fig. 6f. b. Shown are gating strategies of naïve Pmel CD8 T cells activation by cells from inguinal lymph nodes for Fig. 6g.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Koch Institute Swanson Biotechnology Center for technical support, especially the Flow Cytometry Facility, Animal Facility, Microscopy Facility, Histology Facility, and Nanotechnology Materials Core Facility. We also thank Glenn A. Paradis, Jeffrey Kuhn, DongSoo Yun, and members of Irvine lab and members of Weiss lab for their discussions and suggestions. This work was supported in part by the Grant P30-CA14051 from National Cancer Institute in support of Koch Institute core facilities, the NIH (award CA20618 to R.W. and D.J.I.), the Marble Center for Nanomedicine, and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard. D.J.I. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Y.D. acknowledges support from the Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award R35GM119679 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. W.Z. acknowledges the support from the Professor Sylvan G. Frank Graduate Fellowship.

Footnotes

Competing interests

D.J.I., K.D.W., R.W., Y.L., N.M., and Y.D. are named as inventors on patent applications filed by MIT related to the data presented in this work (US Patent 16/739,407).

References

- 1.Sharma P & Allison JP The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science 348, 56–61, doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8172 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zou W, Wolchok JD & Chen L PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: Mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations. Sci Transl Med 8, 328rv324, doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7118 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolchok JD et al. Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med 377, 1345–1356, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709684 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen DS & Mellman I Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer-immune set point. Nature 541, 321–330, doi: 10.1038/nature21349 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammerich L et al. Systemic clinical tumor regressions and potentiation of PD1 blockade with in situ vaccination. Nat Med 25, 814–824, doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0410-x (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammerich L, Binder A & Brody JD In situ vaccination: Cancer immunotherapy both personalized and off-the-shelf. Mol Oncol 9, 1966–1981, doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.10.016 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aznar MA et al. Intratumoral Delivery of Immunotherapy-Act Locally, Think Globally. J Immunol 198, 31–39, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601145 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marabelle A, Kohrt H, Caux C & Levy R Intratumoral immunization: a new paradigm for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res 20, 1747–1756, doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2116 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galluzzi L, Buque A, Kepp O, Zitvogel L & Kroemer G Immunogenic cell death in cancer and infectious disease. Nat Rev Immunol 17, 97–111, doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.107 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Twumasi-Boateng K, Pettigrew JL, Kwok YYE, Bell JC & Nelson BH Oncolytic viruses as engineering platforms for combination immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 18, 419–432, doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0009-4 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quetglas JI et al. Virotherapy with a Semliki Forest Virus-Based Vector Encoding IL12 Synergizes with PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade. Cancer Immunol Res 3, 449–454, doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0216 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez-Madoz JR et al. Semliki forest virus expressing interleukin-12 induces antiviral and antitumoral responses in woodchucks with chronic viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Virol 83, 12266–12278, doi: 10.1128/JVI.01597-09 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewitt SL et al. Durable anticancer immunity from intratumoral administration of IL-23, IL-36gamma, and OX40L mRNAs. Sci Transl Med 11, doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat9143 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moss KH, Popova P, Hadrup SR, Astakhova K & Taskova M Lipid Nanoparticles for Delivery of Therapeutic RNA Oligonucleotides. Mol Pharm 16, 2265–2277, doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b01290 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xue HY, Liu S & Wong HL Nanotoxicity: a key obstacle to clinical translation of siRNA-based nanomedicine. Nanomedicine (Lond) 9, 295–312, doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.204 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y et al. In vitro evolution of enhanced RNA replicons for immunotherapy. Sci Rep 9, 6932, doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43422-0 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li B et al. An Orthogonal Array Optimization of Lipid-like Nanoparticles for mRNA Delivery in Vivo. Nano Lett 15, 8099–8107, doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b03528 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Obeid M et al. Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death. Nat Med 13, 54–61, doi: 10.1038/nm1523 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghiringhelli F et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in dendritic cells induces IL-1beta-dependent adaptive immunity against tumors. Nat Med 15, 1170–1178, doi: 10.1038/nm.2028 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iyer SS et al. Necrotic cells trigger a sterile inflammatory response through the Nlrp3 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 20388–20393, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908698106 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selzner N et al. Water induces autocrine stimulation of tumor cell killing through ATP release and P2 receptor binding. Cell Death Differ 11 Suppl 2, S172–180, doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401505 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Apetoh L et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med 13, 1050–1059, doi: 10.1038/nm1622 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scaffidi P, Misteli T & Bianchi ME Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature 418, 191–195, doi: 10.1038/nature00858 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawai T & Akira S TLR signaling. Cell Death Differ 13, 816–825, doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401850 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McComb S et al. Type-I interferon signaling through ISGF3 complex is required for sustained Rip3 activation and necroptosis in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, E3206–3213, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407068111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Momin N et al. Anchoring of intratumorally administered cytokines to collagen safely potentiates systemic cancer immunotherapy. Sci Transl Med 11, doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw2614 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lasek W, Zagozdzon R & Jakobisiak M Interleukin 12: still a promising candidate for tumor immunotherapy? Cancer Immunol Immunother 63, 419–435, doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1523-1 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahn J, Xia T, Rabasa Capote A, Betancourt D & Barber GN Extrinsic Phagocyte-Dependent STING Signaling Dictates the Immunogenicity of Dying Cells. Cancer Cell 33, 862–873 e865, doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.027 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sistigu A et al. Cancer cell-autonomous contribution of type I interferon signaling to the efficacy of chemotherapy. Nat Med 20, 1301–1309, doi: 10.1038/nm.3708 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang P et al. Re-designing Interleukin-12 to enhance its safety and potential as an anti-tumor immunotherapeutic agent. Nat Commun 8, 1395, doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01385-8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barrett JA et al. Regulated intratumoral expression of IL-12 using a RheoSwitch Therapeutic System((R)) (RTS((R))) gene switch as gene therapy for the treatment of glioma. Cancer Gene Ther 25, 106–116, doi: 10.1038/s41417-018-0019-0 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daud AI et al. Phase I trial of interleukin-12 plasmid electroporation in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 26, 5896–5903, doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6794 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lucas ML, Heller L, Coppola D & Heller R IL-12 plasmid delivery by in vivo electroporation for the successful treatment of established subcutaneous B16.F10 melanoma. Mol Ther 5, 668–675, doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0601 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mukhopadhyay A et al. Characterization of abscopal effects of intratumoral electroporation-mediated IL-12 gene therapy. Gene Ther 26, 1–15, doi: 10.1038/s41434-018-0044-5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiocca EA et al. Regulatable interleukin-12 gene therapy in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma: Results of a phase 1 trial. Sci Transl Med 11, doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw5680 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhatia S et al. Intratumoral Delivery of Plasmid IL12 Via Electroporation Leads to Regression of Injected and Noninjected Tumors in Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res, doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0972 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herpen, v., Huijbens, R., Looman, M. & de Vries, J. Pharmacokinetics and Immunological Aspects of a Phase Ib Study with Intratumoral Administration of Recombinant Human Interleukin-12 in Patients with …. Clinical Cancer … (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andtbacka RH et al. Talimogene Laherparepvec Improves Durable Response Rate in Patients With Advanced Melanoma. J Clin Oncol 33, 2780–2788, doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3377 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ribas A et al. Oncolytic Virotherapy Promotes Intratumoral T Cell Infiltration and Improves Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy. Cell 170, 1109–1119 e1110, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.027 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim MK et al. Oncolytic and immunotherapeutic vaccinia induces antibody-mediated complement-dependent cancer cell lysis in humans. Sci Transl Med 5, 185ra163, doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005361 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaufman HL, Kohlhapp FJ & Zloza A Oncolytic viruses: a new class of immunotherapy drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 14, 642–662, doi: 10.1038/nrd4663 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li YI, Darrell J; Weiss, Ron Source Data of Fig. 3g. Figshare. Online resource, doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.12502007 (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li YI, Darrell J; Weiss, Ron. Source Data of Fig. 5h. Figshare. Online Resources, doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.12502124 (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang J et al. UV-induced somatic mutations elicit a functional T cell response in the YUMMER1.7 mouse melanoma model. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 30, 428–435, doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12591 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y et al. Persistent Antigen and Prolonged AKT-mTORC1 Activation Underlie Memory CD8 T Cell Impairment in the Absence of CD4 T Cells. J Immunol 195, 1591–1598, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500451 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO & Botstein D Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 14863–14868, doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moynihan KD et al. Eradication of large established tumors in mice by combination immunotherapy that engages innate and adaptive immune responses. Nat Med, doi: 10.1038/nm.4200 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li YI, Darrell J; Weiss, Ron Morphology of DOTAP and TT3 lipid nanoparticles with or without self-replicating RNA. Figshare. Online resource, doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.12498047 (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The source data for Figs. 1–6 and Extended Data Figs. 1–2, Figs. 4-7 have been provided as Source data files. The source data of Fig. 3g are stored in Figshare42. The source data of Fig. 5h are found in SourceData_Li_Fig.5h-Lungimages.pdf and are also stored in Figshare43. The source data for Extended Data Fig. 1d-1g are found in Li_SourceData_ED_Fig.1d-1g, and are also stored in Figshare48. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.