ABSTRACT

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV) is a virus that causes severe liver dysfunctions and hemorrhagic fever, with high mortality rate. Here, we show that CCHFV infection caused a massive lipidation of LC3 in hepatocytes. This lipidation was not dependent on ATG5, ATG7 or BECN1, and no signs for recruitment of the alternative ATG12–ATG3 pathway for lipidation was found. Both virus replication and protein synthesis were required for the lipidation of LC3. Despite an augmented transcription of SQSTM1, the amount of proteins did not show a massive and sustained increase in infected cells, indicating that degradation of SQSTM1 by macroautophagy/autophagy was still occurring. The genetic alteration of autophagy did not influence the production of CCHFV particles demonstrating that autophagy was not required for CCHFV replication. Thus, the results indicate that CCHFV multiplication imposes an overtly elevated level of LC3 mobilization that involves a possibly novel type of non-canonical lipidation.

Abbreviations: BECN1: Beclin 1; CCHF: Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever; CCHFV: Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus; CHX: cycloheximide; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; GFP: green fluorescent protein; GP: glycoproteins; MAP1LC3: microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3; MOI: multiplicity of infection; n.i.: non-infected; NP: nucleoprotein; p.i.: post-infection; SQSTM1: sequestosome 1

KEYWORDS: Autophagy, CCHFV, epithelial cells, LC3 lipidation, viral infection

Introduction

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV) belongs to the Bunyavirales order, Nairoviridae family and Orthonairovirus genus. It is a tick-borne virus that is highly pathogenic in humans, causing a severe hemorrhagic disease (CCHF) due to vascular leakage as well as multiple organ failure with a rate of mortality up to 30% [1 2–4]. Viral transmission takes place through tick bites or via contacts with body fluids from infected patients or animals [3]. Current vaccines and etiologic treatments able to prevent or treat disease remain limited and even debated [5,6]. As for other hemorrhagic fever viruses, the liver is a primary target organ. CCHFV efficiently infect hepatocytes leading to necrosis and release of liver enzymes. Clinical and in vitro studies revealed that mononuclear phagocytes and endothelial cells are also important targets of the virus [7]. During CCHFV infection, immune parameters are strongly modulated depending on the severity and outcome of disease [1–4]. The understanding of the mechanisms involved in CCHF pathogenesis is fragmentary as CCHFV research remains limited, most certainly because the virus requires a level 4 environment context for its handling. CCHFV replicates to high titers and induces a cytopathic effect in Huh7 hepatic cells after 2–3 d of infection [8]. Apart from inducing mitochondria-related apoptotic responses and production of acute inflammatory mediators, CCHFV infection triggers an important endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress both by initiating an unfolded protein response and by increasing the transcription of factors involved in the PMAIP1 (phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1)/Noxa-BBC3 (BCL2 binding component 3)/PUMA ER stress pathway [8].

Autophagy is a hierarchized, multistep pathway that ensures the steady state lysosomal degradation of cytosolic components such as aggregated proteins or senescent organelles and allows for the maintenance of cellular homeostasis under various conditions of changes in the micro-environment [9 10–11]. Autophagy can also contribute to cell intrinsic defense against invading pathogens by efficiently degrading whole microorganisms such as intracellular bacteria, by targeting microbial factors such as components of viruses which are obligate intracellular parasites [12 15–16] and by contributing to regulation of immune and inflammatory cell responses [17,18]. Autophagy relies on the biogenesis of double membraned vesicles called autophagosomes that encapsulate the cytoplasmic components targeted for elimination prior to fusion with endo/lysosomal vesicles to form autolysosomes where degradation occurs. Briefly, autophagosome formation involves 2 ubiquitin-like conjugation systems. The ATG (autophagy related) 5 factor is conjugated to ATG12 prior to interaction with ATG16L1 in the presence of ATG7 and ATG10. The ATG12–ATG5-ATG16L1 complex then promotes the conjugation of Atg8-family proteins (e.g. MAP1LC3/LC3 [microtubule-associated protein 1-light chain 3]) with phosphatidylethanolamine for the anchoring of such lipidated forms into the membrane of phagophores, the precursors of autophagosomes. Newly synthetized LC3 (pro-LC3) must be processed by the ATG4B protease and interact with ATG7 and ATG3 proteins in order to become a substrate (LC3-I) for lipidation. Once lipidated (LC3-II), LC3 cooperates with additional proteins to promote phagophore elongation. LC3 also interacts with autophagy receptors to selectively recruit cargoes prior to autophagosome closure and progression along the flux [11].

No information is currently available on the autophagic status of host cells during CCHFV infection. Since cellular modifications associated with ER stress are susceptible to modulate the autophagic activity of cells [19,20] and because diverse and complex relationships have evolved between the autophagy machinery and viruses [13,14,21,22], we examined the possible impact of CCHFV infection on the autophagic activity of host cells as well as the possible impact of autophagy on the life cycle of the virus. We found that CCHFV infection induced a marked and sustained lipidation of LC3 in epithelial cells. The accumulation of LC3-II was found independent of ATG5, ATG7 and BECN1/beclin 1 core autophagy proteins and could not be described by classical pathways of lipidation, pointing to a possible novel mode of LC3-II production. Importantly, autophagy influenced neither negatively, nor positively, the production/release of infectious particles by infected cells.

Results

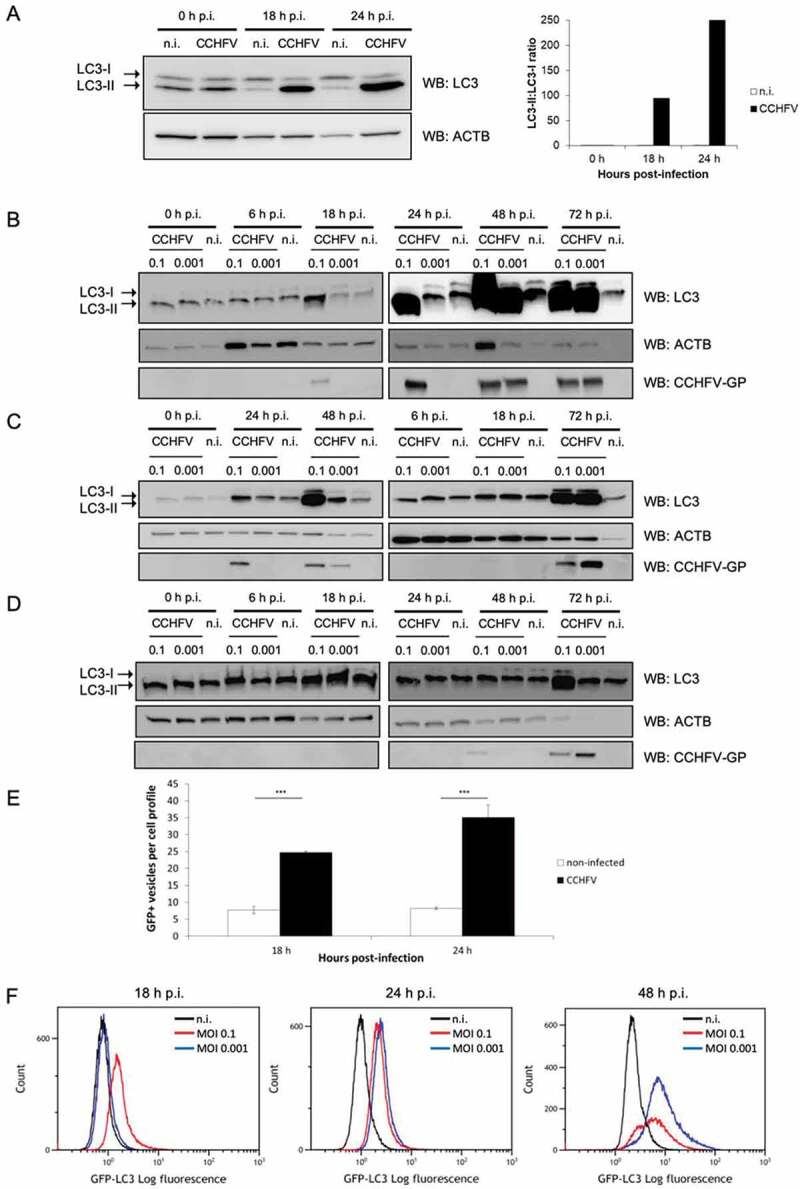

CCHFV infection induces overt LC3 lipidation and LC3-positive, punctiform structures in epithelial cells

MAP1LC3/LC3 is a ubiquitin-like protein whose phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated form (LC3-II) is classically used to monitor autophagic activity of cells. As hepatocytes are key target cells of CCHFV, the infection-associated status of LC3 was first examined by using Huh7 hepatic cells. After infection at multiplicity of infection (MOI) 0.1, a simple 3-points kinetic analysis revealed that CCHFV infection caused a marked increase in the level of LC3-II relative to non-infected cells, as assessed by western blot (Figure 1A). The magnitude of this increase was drastic compared to that induced by the autophagy inducer trehalose (Fig. S1A). A more complete kinetic conducted with 6 time points and 2 MOIs (0.1 and 0.001) revealed that the increase observed at MOI 0.1 was obvious as early as 18 h of infection (Figure 1B), a time point previously found to be associated with a 5% rate of infection [8]. LC3-II level further increased at 24 h (associated with a 12% rate of infection), reached its maximum at 48 h (associated with 100% of infection) and was maintained at 72 h post-infection. Lowering the MOI to 0.001 clearly delayed the induction of LC3-II (Figure 1B). LC3-II induction by CCHFV infection was also marked, albeit not as strong, in HepG2 hepatocytes that are also permissive for CCHFV infection, with however a slightly different kinetic as a certain delay seemed to take place relative to the Huh7 profile (Figure 1C). Since HeLa cells are commonly used to study mammalian autophagy, the impact of CCHFV infection on LC3 status was examined in these cells as well. Like hepatocytes, HeLa cells displayed LC3-II accumulation upon CCHFV infection with a profile/kinetic resembling that of HepG2 cells (Figure 1D). Of interest was the fact that accumulation of LC3-II correlated well with detectable expression of viral glycoproteins in all analysis (Figure 1B–D and Fig. S1B). To determine whether the observed LC3 lipidation is associated with the formation of LC3-positive punctiform structures, Huh7 cells were transfected with a GFP (green fluorescent protein)-LC3 reporter construct and used for regular fluorescence microscopy analysis after viral infection. While the level of LC3-positive puncta was limited and stable over time in non-infected cells, it was clearly elevated already at 18 h in infected cells and further increased at 24 h post-infection (Figure 1E and Fig. S1C). Immuno-staining experiments indicated that both viral glycoprotein (GP) and nucleoprotein (NP) were detectable in Huh7 cells harboring GFP-LC3-positive puncta indicating that occurrence of puncta accumulation was effectively associated with CCHFV infection (Fig. S2A). HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 also showed accumulation of LC3-positive puncta at 48 h post-infection (Fig. S2B) in accordance with the time course result observed in the biological analysis of regular HeLa cells (Figure 1D). Since the fine morphology of puncta could not be examined by confocal microscopy in the biosafety level 4 facility and because ectopically expressed GFP-LC3 may in some instances, generate background signals due to LC3 recruitment to protein aggregates [23], it was difficult to determine whether CCHFV infection-induced puncta effectively corresponded to autophagosomal vesicles. However, CCHFV infection also induced puncta accumulation in GFP-LC3 stably transfected HeLa cells (Fig. S2B) for which formation of GFP-LC3 aggregates is reported as marginal [23]. In addition, the flow cytometry analysis of infected GFP-LC3 HeLa cells after saponin permeabilization revealed that the retained fluorescence of GFP-LC3 increased in a MOI-dependent fashion as early as 18 h post-CCHFV infection (Figure 1F), indicating that viral infection caused the formation of non-soluble, i.e. likely membrane-associated, GFP-LC3 puncta. Collectively, our data indicate that CCHFV infection induces a marked lipidation of the autophagy factor LC3 in all epithelial cell lines tested and is associated with the accumulation of non-soluble, punctiform LC3-positive structures in GFP-LC3 reporter cells.

Figure 1.

Marked LC3 lipidation and induction of LC3-positive punctiform structures in epithelial cells infected with CCHFV. (A–D) Huh7 (A and B), HepG2 (C) and HeLa (D) cells were infected with CCHFV at MOI 0.1 (A) or MOI 0.1 and 0.001 (B), or left uninfected, and analyzed by western blot for LC3, ACTB/β-ACTIN and CCHFV-GP at 0, 18 and 24 h (A) or 0, 6, 18, 24, 48 and 72 h (B-D) after infection. Note that the order of sample loading might differ between cell lines. Quantification in A represents the LC3-II:LC3-I ratio. Both the massive LC3-II signal and the light LC3-I signal made difficult the calculation of an LC3-II:LC3-I ratio in panel B to D. (E) Fluorescence microscopy analysis of GFP-LC3-transfected Huh7 cells infected, or not, with CCHFV (MOI 0.1). GFP-LC3 puncta were quantified after 18 h and 24 h of infection. Results are expressed as the number of puncta per cell (mean ± SD). At least 150 cells were examined for each condition. Representative images are presented in Fig. S1C. (F) Non-infected or CCHFV-infected (MOI 0.1 and 0.001) GFP-LC3 HeLa cells were permeabilized by using saponin for evacuation of soluble forms of GFP-LC3 and analyzed by flow cytometry at 18, 24 and 48 h after infection. Histograms represent the log fluorescence intensity of non-soluble GFP-LC3 (x-axis) relative to cell number (y-axis). 50 000 events were collected per conditions. Experiments were carried out 3 times (A-D) or twice (F).

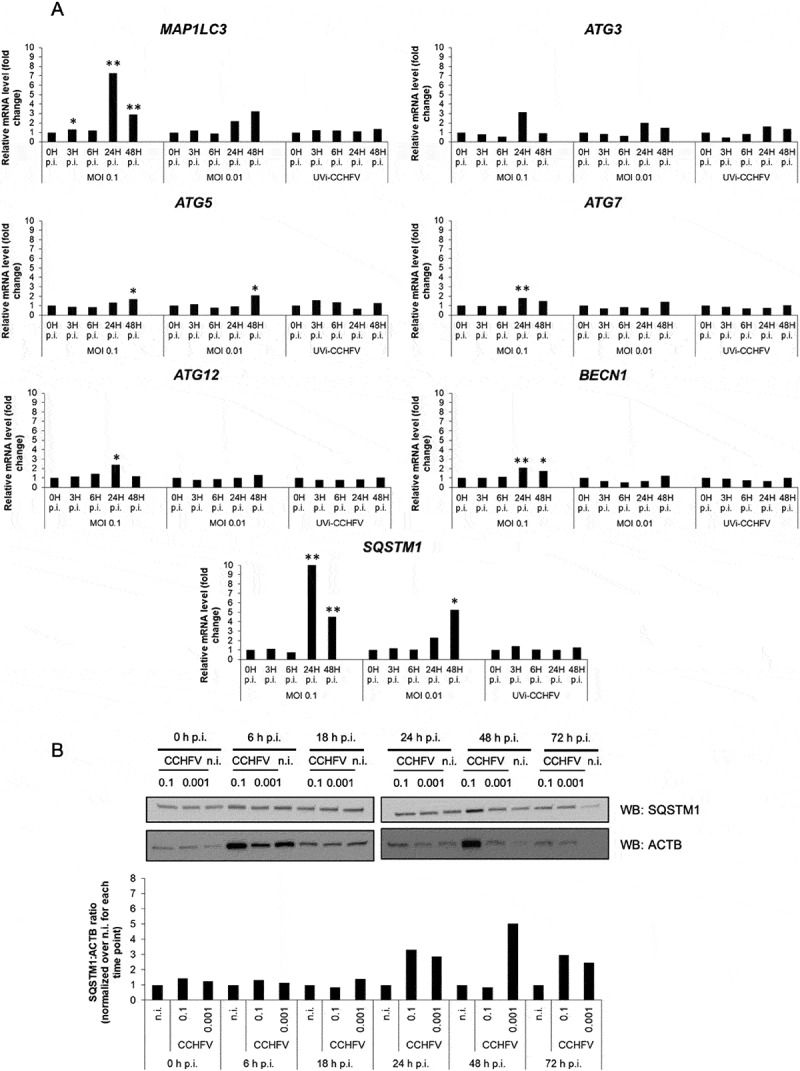

Changes in the expression profile of key autophagy factors during CCHFV infection

The elevated level of LC3-II in CCHFV-infected cells made us wonder whether such a level reflected the lipidation of the available pool of LC3 molecules or whether it could involve LC3 originating from an augmented transcription of MAP1LC3 genes. To explore this issue, we performed a reverse transcription-coupled quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis to monitor the level of MAP1LC3A/B transcripts during infection of Huh7 cells. To gain insights into the expression level of a few additional key autophagy genes important for the generation of LC3-II, we simultaneously studied ATG3, ATG5, ATG7, ATG12 and BECN1. In addition, we also examined SQSTM1 as its transcription often shows modulation in cells exposed to various stress factors. Relative to expression levels observed in the presence of a non-replicative UV-inactivated CCHFV (see control in Fig. S3A), the transcripts of ATG3, ATG5, ATG7, ATG12 and BECN1 all showed some slight but detectable levels of upregulation at 24 h and 48 h post-infection. In contrast, MAP1LC3 transcripts were strongly up regulated at 24 h. Such an up-regulation was massive in the case of MOI 0.1 and more moderate and progressive in the case of MOI 0.01 (Figure 2A). Thus, the transcription of MAP1LC3A/B was markedly increased during CCHFV infection, suggesting that the massive pool of LC3-II seen in virally infected Huh7 cells could originate from newly produced LC3 molecules.

Figure 2.

Status of autophagy-related gene expression and SQSTM1 in CCHFV-infected cells. (A) Transcripts of MAP1LC3A/B, ATG3, ATG5, ATG7, ATG12, BECN1 and SQSTM1 autophagy genes were quantified by RT-qPCR by using total RNA from Huh7 cells (histograms) infected with CCHFV (MOI 0.1 and 0.01) at 0, 3, 6, 24 and 48 h after infection. UV-inactivated CCHFV (MOI 0.1) was used in parallel as non-replicative control. GAPDH, HMBS and ACTB were used as house-keeping genes. Fold changes were calculated after deriving ΔΔCt. (B) Huh7 cells were infected with CCHFV at MOI 0.1 and 0.001 and analyzed by western blot for SQSTM1 and ACTB levels at 0, 6, 18, 24 and 72 h after infection. The companion histograms represent the SQSTM1:ACTB ratio normalized to non-infected cells (combining two independent experiments). The ACTB signals are the same as in Figure 1A due to simultaneous analysis of LC3 and SQSTM1. The quantification was not done for the 72 h condition due to faint ACTB signal. All experiments were carried out at least twice.

Similar to MAP1LC3A/B, we clearly observed an upregulated transcription of SQSTM1 at 24 h and 48 h post-infection. By its magnitude, this increase in transcription was indeed higher than that observed for MAP1LC3A/B. Again, the highest increase was in the presence of the highest MOI (0.1) and a lowered MOI revealed a delayed maximal effect (Figure 2A). Hence, in CCHFV-infected Huh7 cells, SQSTM1 undergoes a burst in transcription 24 h post-infection. SQSTM1 (sequestosome 1)/p62 is a long-lived protein that is degraded by autophagy [24,25] and whose expression level may reveal changes in the autophagic activity of host cells. To monitor SQSTM1 protein level during infection, we performed a western blot kinetic analysis of Huh7 cells which showed the fastest and strongest induction of LC3-II when exposed to infectious CCHFV (see Fig. S1B for concomitant analysis of the 3 cell lines). Consistent with the RT-qPCR analysis, we found that SQSTM1 level was unchanged during the first hours of infection (up to 18 h) and suddenly increased at 24 h by 2–3 folds (Figure 2B). Importantly, the modulation of SQSTM1 was remarkably consistent with that of its transcript: there was an important increase at 24 h that clearly declined by 48 h in the case of MOI 0.1 and a more progressive augmentation seen between 24 h and 48 h in the case of the lowest MOI. As mentioned above, the rate of infected Huh7 cells is about 5% at 18 h, 12% at 24 h and 100% at 48 h when using MOI 0.1. Thus, a nearly ten-fold increase in the percentage of infection (24 h vs 48 h) was not associated with a sustained accumulation of the SQSTM1 protein in the Huh7 culture, suggesting that SQSTM1 undergoes an efficient degradation in the homogenously infected culture. When analyzing HepG2 cells by western blot, we found a clear increase in SQSTM1 at 48 h in the case of the highest MOI that resolved later, suggesting that the cells normalized the level of SQSTM1 through degradation (Fig. S3B). In support of the notion of a functional degradation of SQSTM1 in CCHFV-infected HepG2 cells, a separate study showed that SQSTM1 was not found among proteins whose level was differentially expressed at the peak of viral replication obtained with MOI 1 (24 h) [26]. In the latter study, the protein profiles of control and CCHFV-infected HepG2 cells were examined by using two quantitative approaches: 2D-DIGE and iTRAq. As to HeLa cells, we did not observe substantial changes of the SQSTM1 expression level by western blot, including at late time points (Fig. S3C).

Collectively, the results on the expression profile of key autophagy genes during CCHFV infection revealed that: (I) several core autophagy genes show a subtle and concomitant up-regulation of transcription 24 h post-infection in Huh7 cells, (II) CCHFV infection caused a burst in the expression level of both SQSTM1 and MAP1LC3A/B autophagy genes in Huh7 cells, (III) the changes in transcription level of SQSTM1 correlated closely with the expression level of SQSTM1 in Huh7 cells. Thus, despite variations of the level of SQSTM1 at some time points in some of the cells analyzed, there was no obligate and sustained accumulation of SQSTM1 in CCHFV-infected epithelial cells, suggesting that the CCHFV-infection status was compatible with occurrence of functional SQSTM1 degradation/recycling.

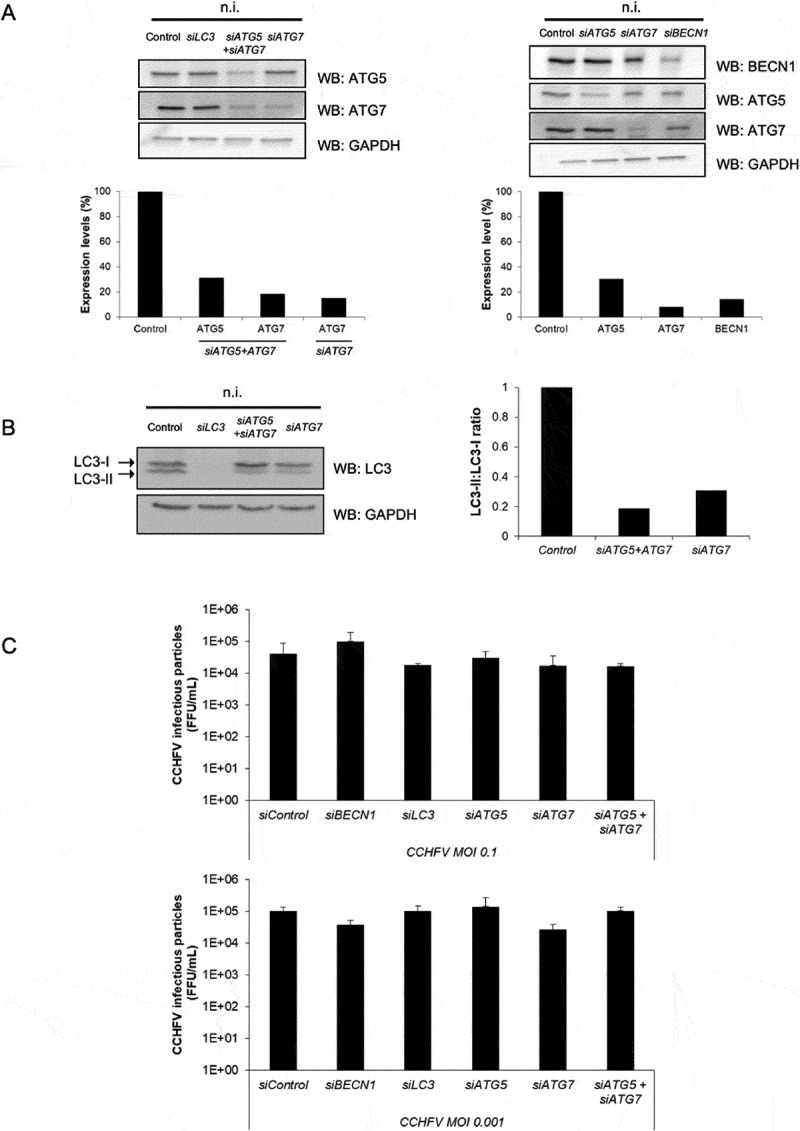

The autophagic status of host cells does not influence CCHFV particle production

To study the influence of the autophagic activity on the outcome of CCHFV infection, the expression of genes important for autophagy was impaired prior to viral infection by using specific siRNAs. ATG5, ATG7, MAP1LC3s and BECN1 were targeted for silencing during 48 h. As ATG5 down regulation tended to be partial in some instances, siRNAs targeting both ATG5 and ATG7 were also used in combination (Figure 3A). That silencing effectively impacted the autophagic activity of Huh7 cells was illustrated by the diminished degree of LC3 lipidation as assessed by western blot (Figure 3B). We then evaluated the impact of autophagy gene silencing on the capacity of Huh7 cells to produce infectious viral particles by performing plaque assay on VeroE6 cells with serial dilutions of cell supernatant harvested 48 h post-infection. The results revealed no significant differences for both MOI used (0.1 and 0.001), indicating that none of the BECN1/ATG5/ATG7/LC3 core autophagy proteins were required for an efficient production/release of infectious CCHFV particles by Huh7 cells (Figure 3C). When the expression pattern of CCHFV-GP and NP associated with the silencing of ATG5, ATG7, MAP1LC3s and BECN1 was examined by western blot, we did not observe any substantial variations regardless of the MOI used (Fig. S4), indicating that silencing these autophagy genes did not impact the CCHFV protein synthesis.

Figure 3.

CCHFV particle production is independent of canonical autophagy. Huh7 cells were treated with siRNA targeting ATG5, ATG7, MAP1LC3A-C and BECN1 genes for 48 h. Cells were then infected (MOI 0.1 and 0.001), or not (n.i.), with CCHFV and analyzed for their capacity to release infectious viral particles after 48 h of infection. (A) Expression levels of ATG5, ATG7, BECN1 and GAPDH after 48 h of siRNA-mediated silencing (i.e. prior to infection with CCHFV). (B) Status of LC3 after 48 h of treatment with siRNA targeting MAP1LC3A-C, ATG7 and ATG5+ ATG7 in the absence of infection. Quantification represents the LC3-II:LC3-I ratio. (C) Measurement of the production of CCHFV viral particles by siRNA-treated Huh7 cells after 48 h of infection. The values represent the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. No differences reached statistical significance.

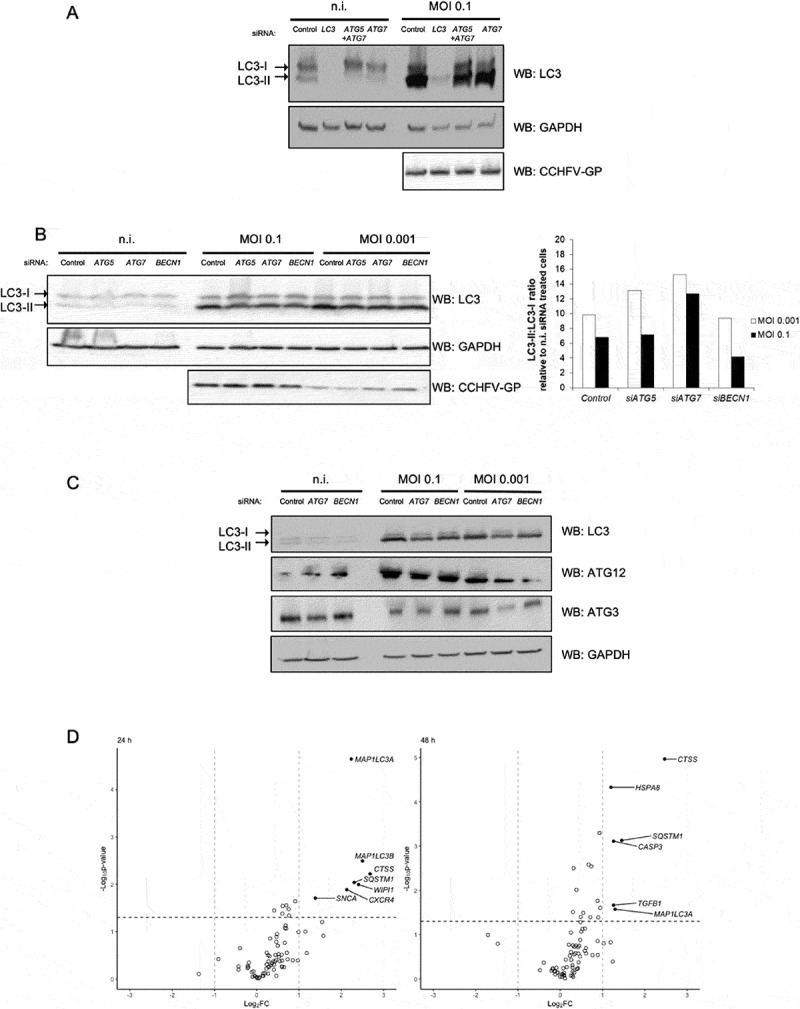

CCHFV-induced LC3 lipidation involves neither ATG5, ATG7 and BECN1 core autophagy proteins nor the ATG12–ATG3 alternative pathway

Silencing experiments were used to examine whether CCHFV-induced LC3 lipidation was dependent or not on the autophagy factor mentioned above. Importantly, preventing the expression of LC3 proteins extinguished LC3 signals in CCHFV-infected cells (Figure 4A), demonstrating that the marked induction of LC3-II seen during CCHFV infection did not reflect cross-reactivity of anti-LC3 antibodies to either viral protein(s) or to newly expressed endogenous protein(s). As expected, silencing ATG5, ATG7 or BECN1 inhibited LC3-II formation in non-infected cells (Figures 3B and 4A,B). In contrast, silencing BECN1, ATG5 and/or ATG7 did not prevent the overt lipidation of LC3-II in CCHFV-infected Huh7 cells regardless of the MOI used (Figure 4A,B). Thus, in Huh7 cells, LC3 lipidation associated with CCHFV infection did not require ATG5, ATG7 or BECN1 core autophagy proteins, suggesting the occurrence of a non-canonical form of LC3 lipidation. An ATG5/ATG7 independent LC3 lipidation process has been reported during Vaccinia virus infection of ATG5 deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts with a massive level of LC3-II seen at 24 h post-infection [27]. In that instance, a complex made of ATG12 conjugated to the E2-like enzyme ATG3 was the main driver of LC3 lipidation in response to infection. With respect to ATG12 and ATG3 proteins, we indeed noticed a slight and transient up regulation of their levels of transcription 24 h after infection of Huh7 cells at MOI 0.1 (Figure 2A). To determine whether an ATG12–ATG3 complex could be induced upon CCHFV infection of Huh7 cells, an immuno-blot analysis of ATG12 and ATG3 was performed. The results revealed that only the regular monomeric 37 kDa form of ATG3 could be detected at 48 h post-infection at the 2 MOI tested (Figure 4C). The presence of the ATG12-associated form of ATG3 (49 kDa) could not be found, including in the absence of ATG7. The results suggest that, in contrast to Vaccinia virus infection of mouse fibroblasts, ATG12–ATG3 complex-driven lipidation of LC3 is unlikely to underlie the elevated LC3 lipidation activity that occurred during CCHFV infection of epithelial cells. As the results pointed to a novel, non-conventional mode of LC3 lipidation, we tried to obtain a more complete view of the changes that occur in the expression profile of autophagy-related genes during CCHFV infection. We used a RT-Profiler PCR array that covered 84 genes involved in the constitution of the autophagy machinery or contributing to the regulation of its functioning in response to changes in the cell micro-environment. Huh7 cells were infected with CCHFV at MOI 0.1 and analyzed after 24 h and 48 h of infection (Figure 4D). The results indicated that there was no overt down regulation of expression among the autophagy genes analyzed. CCHFV infection induced an up-regulation of several transcripts. Consistent with the RT-qPCR data, SQSTM1, MAP1LC3A and MAP1LC3B transcripts were clearly upregulated at 24 h. ATG4B transcription was not strongly modified during CCHFV infection (the transcript level was 1.35 at 24 h and 1.08 at 48 h relative to non- infected cells) suggesting that the newly synthetized pool of LC3 molecules relied on a nearly normal level of ATG4B for its conversion to LC3-I. Other genes revealed some degrees of enhanced transcription. They included CTSS (cathepsin S), WIPI1 (WD repeat domain-phosphoinositide interacting 1), CXCR4 (C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4), CASP3 (caspase 3) and HSPA8 (heat shock protein family A [Hsp70] member 8). Because the above-mentioned factors are not currently known to regulate the production of LC3-II in mammalian cells, it was difficult to better delineate the basis of the unusual LC3 lipidation process at work in CCHFV-infected cells. Nevertheless, the transcript analysis further documented the marked changes that affect the expression level of SQSTM1 and MAP1LC3s genes during Huh7 cells infection with CCHFV.

Figure 4.

Neither ATG5, ATG7 and BECN1 core autophagy proteins, nor the ATG12–ATG3 complex are involved in CCHFV-induced LC3 lipidation. (A) Huh7 cells were treated with siRNA targeting MAP1LC3A-C, ATG5+ ATG7 or ATG7 genes for 48 h, infected or not with CCFV at MOI 0.1 and analyzed by western blot for LC3, CCHFV-GP and GAPDH levels 48 h after infection. (B) Huh7 cells were treated with siRNA targeting ATG5, ATG7 or BECN1 genes for 48 h, infected with CCHFV at MOI 0.1 vs 0.001, and analyzed by western blot for LC3, CCHFV-GP and GAPDH levels 48 h after infection. Quantification represents the LC3-II:LC3-I ratio normalized to that of the corresponding siRNA-treated, non-infected cells. (C) Huh7 cells were treated with siRNA targeting ATG7 or BECN1 genes for 48 h, infected with CCFV at MOI 0.1 vs 0.001, and analyzed by western blot for LC3 (17 and 15 kDa), ATG12 (55 kDa due to conjugation to ATG5), ATG3 (36 kDa) and GAPDH levels 48 h after infection. The presence of a 49 kDa complex could not be detected by either anti-ATG12 or anti-ATG3 antibodies. (D) Volcano plot representation of fold change of transcript level for 84 genes involved in autophagy execution or regulation (RT-Profiler PCR array) after infection of Huh7 cells with CCHFV (MOI 0.1). Changes are relative to non-infected control cells. Calculations and normalization were performed as described by SABiosciences using 5 house-keeping genes (ACTB, B2M [beta-2-microglobulin], GAPDH, RPLP0 (ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P0) and HPRT1 (hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1)). Experiments were carried out twice (A-C) and 3 times (D).

CCHFV-induced LC3 lipidation depends on viral replication and protein synthesis

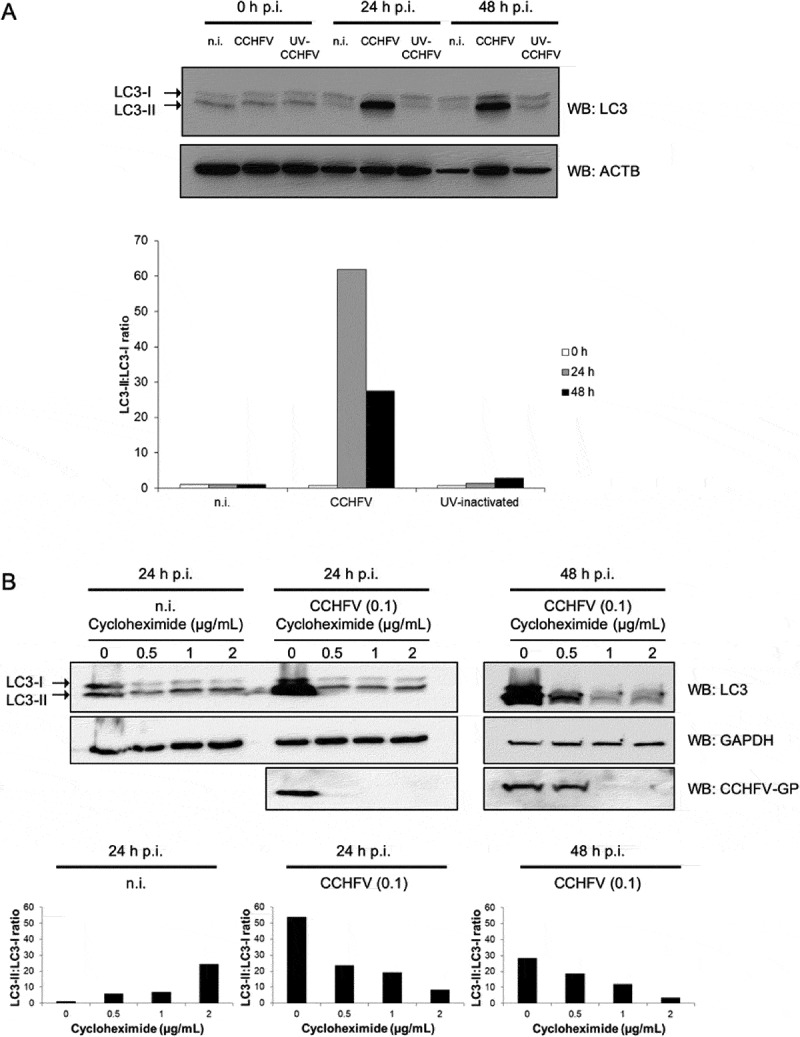

CCHFV replication is known to occur as soon as 3 h post-infection and to intensify up to 24 h post-infection. Thus, in Huh7 cells, the virus has already undergone several cycles of replication when a marked LC3-II signal is observed by western blot at the 18 h time point. To evaluate the contribution of viral entry to LC3-II induction, Huh7 cells were exposed to an ultraviolet (UV)-inactivated CCHFV which is devoid of replicative capacity as assessed by qPCR analysis (Fig. S3A). We observed that in contrast to its infectious counterpart, UV-inactivated CCHFV was unable to induce a substantial level of LC3-II (Figure 5A). Thus, molecular events associated with viral entry played no role in the induction of LC3-II during CCHFV infection. To establish the role of viral protein synthesis in induced LC3 lipidation, de novo protein synthesis was inhibited by using cycloheximide (CHX). CHX, which effectively blocked viral GP synthesis, inhibited the accumulation of LC3-II both at 24 h and 48 h post-infection (Figure 5B). Consistent with this notion, a lower dose of CHX (0.5 μg/ml) that failed to restrict CCHFV-GP protein synthesis beyond the 24 h time point, was effectively associated with detectable LC3-II induction. The results indicate that in Huh7 cells infected with CCHFV, the marked lipidation of LC3 is independent of entry-associated events such as attachment, clathrin-mediated endocytosis or uncoating and instead, requires both the replicative potential of the virus and protein synthesis activity.

Figure 5.

Both CCHFV replicative capacity and protein synthesis are necessary for sustained LC3 lipidation in infected epithelial cells. (A) Huh7 cells were exposed to infectious CCHFV (CCHFV), UV-irradiated CCHFV (UV-CCHFV) (MOI 0.1) or left uninfected (n.i.) for 24 h and 48 h. Cell lysates were western blotted for detection of LC3 and ACTB. Quantification represents the LC3-II:LC3-I ratio. (B) Huh7 cells were treated with 0, 0.5, 1, or 2 μg/ml cycloheximide, infected or not with CCHFV (MOI 0.1), lysed at 24 h or 48 h after infection and analyzed by western blot for detection of LC3, CCHFV-GP and GAPDH. Quantification represents the LC3-II:LC3-I ratio. Experiments were carried out twice.

Discussion

In the present study, we report the first analysis of the relationship between autophagy and the life cycle of the class 4 pathogen CCHFV in human epithelial cells. We found that CCHFV infection induced an elevated and sustained level of LC3 lipidation in both hepatic and HeLa epithelial cells with a particularly striking intensity in Huh7 hepatic cells. This augmented lipidation was MOI dependent, correlated with virus GP or NP expression, increased over time and culminated at 48 h/72 h post-infection. The elevated level of LC3-II correlated with an augmented number of LC3-positive punctiform structures as assessed by the microscopy analysis of GFP-LC3 reporter cells when infected with CCHFV. Unexpectedly, the overt lipidation of LC3 was independent of the core autophagy proteins BECN1, ATG5 and ATG7 indicating that a non-classical mode of LC3 lipidation is operating in CCHFV-infected cells. Importantly, the overt lipidation of LC3 was dependent on both the intact capacity of the virus to replicate and the proper functioning of the protein synthesis machinery. We believe that the strong LC3 signal observed during CCHFV infection does not correspond to the truncated form of LC3 (LC3-T) that can be generated by 20S proteasome-mediated cleavage of LC3 even in the absence of ATG7 [28]. The reason for this is that LC3-I and LC3-II species run slightly distinctively on SDS-PAGE and in the case of CCHFV-infected cells, this difference could not be observed when looking at blots where the induced LC3 signal was mild enough to be compared carefully to LC3-II from non-infected cells (e.g. MOI 0.001 after 48 h infection of HepG2 cells [Figure 1C] or MOI 0.001 at 72 h in HeLa cells [Figure 1D]).

Marked lipidation of LC3 has already been observed during mammalian cell infection by distinct viruses. For instance, infection of monkey epithelial cells with Rotavirus augmented the level of LC3-II in a replication-dependent fashion without inducing autophagosome formation [29]. Such a LC3 lipidation, whose mechanism was not delineated, was required for an optimal production of viral particles. Another example of enhanced LC3 lipidation relates to the life cycle of Vaccinia virus in mouse embryonic fibroblast [27]. In that instance, LC3-II biogenesis was independent of ATG5 and ATG7 and instead, strictly relied on complexation of ATG12 with the E2-like enzyme ATG3 that is required for conjugation of LC3-I to phosphatidylethanolamine. However, such an enhanced lipidation was not required for the efficient production of virus particles. Of note, Vaccinia virus replication was associated with a complete block of the autophagy process. While investigating a possible role for ATG3 in CCHFV-induced lipidation of LC3, we could not detect the presence of the 49 kDa ATG12–ATG3 complex in CCHFV-infected cells suggesting that assembly/recruitment of this complex was unlikely to drive LC3-II formation in CCHFV-infected human epithelial cells. Thus, the detailed mechanism(s) underlying the marked and sustained LC3 lipidation seen in epithelial cells infected with CCHFV remains to be elucidated.

The amount of the long-lived autophagy protein SQSTM1 showed some augmentation during CCHFV infection of Huh7 hepatic epithelial cells. However, such an augmentation was not massive given the highly concomitant increase in the amount of the corresponding transcript and was clearly decoupled from the infection rate of the culture, suggesting that SQSTM1 autophagic degradation could still be efficient in Huh7 cells undergoing CCHFV infection. Variations in the level of SQSTM1 appeared also to resolve over time in HepG2 cells. Consistent with this notion, SQSTM1 was found to not significantly accumulate in HepG2 cells infected with CCHFV as assessed by two distinct quantitative proteomic analysis [26]. Finally, we found that SQSTM1 remained at its background level in CCHFV-infected HeLa cells suggesting again that its autophagic degradation remained operative during infection.

The functionality of the autophagy machinery of CCHFV-infected epithelial cells contrasted with the situation of mouse embryonic fibroblast infected with Vaccinia virus where the overt lipidation of LC3 was associated with a complete block of the autophagic activity as no biogenesis of autophagosome could be observed even upon induction [27]. The autophagy machinery required to recruit LC3 to punctiform structures appeared functional in CCHFV-infected cells as we noticed an increase in the number of LC3-positive dots after infection. These punctiform structures that were not affected by membrane permeabilization, could reasonably correspond to autophagic vesicles although a definitive clarification of their nature would require ultrastructural analysis.

Atypical LC3 mobilization/redistribution is not rare in mammalian cells infected by viruses. For instances, double-membrane vesicles coated with LC3-I can contribute to the replication of the Coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus [30]; LC3-I molecules are present in replication complexes that are part of the replication cycle of the Flavivirus Japanese encephalitis virus [31]; LC3 is re-localized to the plasma membrane in host cells infected with influenza A virus [32]; LC3-positive organelles deriving from nuclear membranes and bearing viral proteins are assembled during HSV-1 infection [33]; LC3 decorates unusually large compartments that are associated with autophagic response during Coxsackievirus B3 infection of pancreatic cells [34]; LC3-II positive vesicles get concentrated at the viral assembly compartment that promotes the final assembly of human cytomegalovirus virions [35]. Viral proteins can also directly interact with both pro-LC3 and LC3-I/II to interfere with autophagy [36]. In the case of CCHFV, the nature of putative functional consequences of the high level of LC3 lipidation on the outcome of infection is not obvious. A possibility could have been that some degrees of autophagic responses are capable of interfering with CCHFV replication and that directing the available pool of LC3 toward an obligate and sustained lipidation step could significantly perturbate the dynamic of such an opposition. However, it was clear that neutralizing core autophagy proteins such as BECN1, ATG5, ATG7 or even LC3A/B had no detectable effect on the assembly/release of infectious CCHFV particles making this hypothesis unlikely. Results from the silencing experiments also invalidated another possibility which was a promoting role for lipidated LC3 in the assembly/envelopment of newly formed CCHFV particles; since the silencing of all LC3 isoforms did not impact the production of infectious CCHFV virions, one can conclude that an abundant level of LC3-II was not necessary for their assembly/release. Finally, we believe that elevated LC3-II is unlikely to reflect mobilization of LC3 for anchoring onto some phagosome-like compartments as occurrence of LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP) is dependent on ATG5 and CCHFV-induced increase of LC3-II was found independent of ATG5 in silencing experiments. At this point, the possible consequences of the overt lipidation of LC3 on the whole infection process appear rather marginal. Possibly, overt LC3 lipidation may, at least in part, represent a consequence of the ER-stress response associated with CCHFV infection [8].

In summary, we found that in human epithelial cells infected with the Orthonairovirus CCHFV, autophagy was not involved in restricting or promoting viral replication. Regarding the impact of viral replication on the autophagy machinery, CCHFV caused a subtle and coordinated increase in the transcription level of several core autophagy genes (ATG5, ATG7, ATG3, ATG12 and BECN1) and a marked burst in the transcription level of both MAP1LC3s and SQSTM1. Unlike during Vaccinia virus infection of mouse fibroblasts [27], there was no evidence for a marked blockade of the autophagy flux, at least in the case of SQSTM1 degradation-related autophagy. Nevertheless, CCHFV infection caused a sharp non-classical lipidation of LC3 that was dependent on both protein synthesis and the capacity of the virus to replicate. Such a massive and atypical lipidation could proceed in the absence of ATG5, ATG7 and BECN1. As mentioned above, it is also distinct from the ATG12–ATG3 complex-dependent LC3 lipidation that occurs during Vaccinia virus infection of mouse cells. Importantly, the ATG12–ATG3 complex can modulate the functioning of the autophagy machinery in the absence of infection. Although it appears not to contribute to starvation-induced autophagy, it is involved in the steady-state autophagy flux of mammalian cells by promoting autophagosome maturation [37,38]. Thus, Vaccinia virus infection is associated with recruitment of a complex that is part of constitutive autophagy. Because viruses mainly perturbate cellular functions by manipulating/highjacking pathways that preexist in host cells, we speculate that elucidating the pathway involved in CCHFV-induced LC3 lipidation may uncover a novel mode of LC3-II synthesis that may be functional in host cells and possibly, participate to some form of autophagic activity at steady state.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The experiments reported in this article were performed at Biological Safety Level 4 in accordance with the regulations set forth by the national French committee of genetic (commission de génie génétique).

Cell culture

Huh7, HepG2 and VeroE6 cells were maintained in DMEM (Life Technologies, 31966–021) supplemented with 50 U/mL of penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies, 15070–063), and non-essential amino-acids for Huh7 cells (Life Technologies, 11140–035). HeLa and GFP-LC3-HeLa cells [39] were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, 61870–010) with 50 µg/mL gentamicin. All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies, 10270–106) and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2.

CCHFV strains and viral particle titration

Cells were infected using CCHFV isolate IbAr10200 (obtained from Pasteur Institute) produced on VeroE6 cells. Absence of Mycoplasma from cells and virus aliquots was confirmed using MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection kit (Lonza, LT07-710). CCHFV was inactivated by UV-light for 30 min (UV Mineral light lamp, UVG-54, 254 nm, Upland, USA). Infections were carried out at two MOI for 1 h in DMEM without FBS, before adding complete media. After the indicated period of time of infection, infectious viral particles were quantified by limiting dilution on confluent Vero cells: cells were infected with serial dilutions of CCHFV-infected cells supernatants for 1 h. DMEM supplemented with 2.5% final FBS and 3.2% carboxymethylcellulose (VWR, 22525.296) was then added and cells were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 5 days. VeroE6 cells were then fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, 252549) and were incubated with a mouse hyper-immunized ascetic fluid specific to CCHFV (obtained from Pasteur Institute) for 1 h followed by a 45 min incubation with a goat anti-mouse peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 115-035-146), at 37°C, 5% CO2. Foci of infected cells were detected using 3.3ʹ-diaminobenzidine (Sigma, D4293). Titrations were determined as FFU/mL.

siRNA transfection

Cells (0.1 x 106) were plated in 6-well plates 24 h prior to transfection with 100 pmol siRNA/well (Stealth siRNA for Life Technologies) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Life Technologies, 13800–075), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Media was changed 4 h later using DMEM containing 2.5% FBS and cells were infected 48 h after siRNA transfection. Protein expression level was assessed by western-blot two days post-transfection.

Western blot

Cells were collected in RIPA buffer (Sigma, R0278) for western blot analysis. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (Mini-Protean TGX Precast Gels; Bio-Rad, 456–1083) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad, 170–4156). Blots were incubated with primary antibodies with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBS-0.1% Tween 20 overnight at 4°C. HRP-linked secondary antibodies were used for 1 h at room temperature and antigen-antibody complexes were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare, RPN2209; Luminol-based Enhanced Chemiluminescent [ECL] western blotting detection reagents); quantification were assessed using ImageQuant LAS4000 imager software (GE Healthcare).

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies to ACTB/β-ACTIN (clone 13E5, 4970S), GAPDH (clone D16H11, 5174S), MAP1LC3B (clone D11, 3868S), SQSTM1 (5114S), ATG3 (3415), ATG5 (clone D5F5U, 12994), ATG7 (2631), ATG12 (clone D88H11, 4180) and BECN1 (clone D40C5, 3495), and HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse (7074S and 7076S, respectively) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-CCHFV-NP was provided by the Armed Biomedical Research Institute/IRBA and anti-CCHFV-GP was produced in the lab (mouse monoclonal antibody). CHX (Sigma, C4859) was used at the indicated concentration and incubated 1 h post-viral infection. Trehalose (Sigma, T0167) was used at 100 mM starting 2 h before infection and maintained during infection.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR analysis

Viral RNAs were extracted either from infected-cell supernatant using QIAamp viral RNA mini kit (Qiagen, 52906) or from infected-cells by using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, 74106). Genomic strains were quantified using a quantitative one-step RT-PCR assay targeting S segment of CCHFV as previously described [40] using iTaq Universal Probes Supermix (Bio-Rad, 172–5132) and Bio-Rad CFX96. Total RNAs were extracted from infected cells as mentioned above, and expression of several mRNA was assessed with the following forward and reverse primers (5ʹ-3ʹ): MAP1LC3A/B (TGTCCGACTTATTCGAGAGCAGCA, TGTGTCCGTTCACCAACAGGAAGA); SQSTM1 (ATCGGAGGATCCGAGTGT, TGGCTGTGAGCTGCTCTT); BECN1 (GAGGGATGGAAGGGTCTAAG, GCCTGGGCTGTGGTAAGT); ATG3 (CCAACATGGCAATGGGCTAC, ACCGCCAGCATCAGTTTTGG); ATG5 (TGAAAGGGAAGCAGAACCA, TGCAGAAGGTCTTTTTCTGGA); ATG12 (CGAACCATCCAAGGACTCAT, CCATCACTGCCAAAACACTC); GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) (AGAAGGCTGGGGCTCATTT, CAGGAGGCATTGCTGATGA); ACTB/β-ACTIN (CTCTTCCAGCCTTCCTTCCT, AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG); HMBS (hydroxylmethylbilane synthase)/PBGD (TGCCAGAGAAGAGTGTGGTG; ACTGAACTCCTGCTGCTCGT), and DDIT3 (DNA damage inducible transcript 3)/CHOP (ATGGCAGCTGAGTCATTGCCTTTC; AGAAGCAGGGTCAAGAGTGGTCAA). Reverse transcription was carried out using ImPromII Reverse Transcription kit (Promega, A3800), iTaq universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, 170–8882) and Bio-Rad CFX96.

Gene expression profile

Total mRNAs were extracted using RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, 74106). Reverse transcription was performed using RT2 First Strand Kit (QIAGEN, 52906) and qPCR was carried out using RT2 SYBR Green qPCR Mastermix (QIAGEN) and Human Autophagy RT2 Profiler PCR Array (SABiosciences, PAHS-084Z), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The ΔΔCt method was used to calculate fold changes in genes expression for each gene of interest, in infected condition compared to uninfected condition, using housekeeping genes for normalization and RT2 Profiler PDR Array Data Analysis software (SABiosciences).

GFP-LC3 transfection

MAP1LC3B was amplified by RT-PCR from Huh7 cell cDNA, using LC3-forward primer 5ʹ–ATGCCGTCGGAGAAAACCTTCA–3ʹ and LC3-reverse primer 5ʹ–TTACACTGACAATTTCATCCCGA–3ʹ, and cloned into the expression plasmid pCAGGs-eGFP (obtained from Institut de Recherche Biomédicale des Armées [IRBA]). The pCAGGs-GFP-LC3 plasmid was used to transfect Huh7 cells 24 h prior CCHFV infection.

Fluorescence microscopy

CCHFV-infected and non-infected pCAGGs-GFP-LC3-transfected Huh7 or GFP-LC3 HeLa cells were fixed 20 min in 4% PFA and permeabilized with PBS (Life Technologies, 10010-015)-0.5% Triton X-100 (ACROS organics, 3273372500) for 5 min. Cells were eventually incubated with primary antibodies (anti-CCHFV-GP or anti-CCHFV-NP) for 1 h at 37°C and with Alexa Fluor 488 or −594 goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG (H + L) (Life Technologies, A11029, A11032, A11008, A11012) conjugated secondary antibody, for 45 min at 37°C. Cells were analyzed using Axio Observer Z.1 (Zeiss) and MetaMorph® software (Molecular Devices, MetaMorph 7.5). The number of GFP+ dots was numerated from one single plan section per cell.

Flow cytometry

HeLa-GFP-LC3 cells were detached and washed once in PBS. The cells were then incubated 5 min on ice either with saponin 0.05% in PBS or PBS alone. The cells were finally washed twice with PBS and 50 000 events were acquired on a Gallios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, A94303) in the Biosafety Laboratory Level 4 (BSL4). The data were analyzed using Kaluza software (Beckman Coulter, B16409).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were carried out at least 3 times unless indicated otherwise. All p-values were calculated using a two-tailed Welch T-test (Student’s T-test assuming non-equal variances of the samples); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lucile Espert (IRIM Montpellier) for critical reading of the manuscript. All experiments using CCHFV were carried out in the Laboratoire Jean Mérieux-INSERM biosafety laboratory level 4 (BSL4) facility. We are grateful to the BSL4 team members for support while performing the experiments. We also acknowledge the framework of the LABEX ECOFECT (ANR-11-LABX-0042) of Université de Lyon operated by the French National Research Agency (ANR-11-IDEX-0007), within which this work was performed.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the French Armed Forces Health Service, the Direction Générale pour l’Armement (DGA) and Fondation Merieux, and by Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM), ANR-14-CE14-0022, Institut Universitaire de France (IUF) and intramural CIRI projects.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary Material:

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- [1].Ergonul O.Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6(4):203–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Whitehouse CA.Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Antiviral Res. 2004;64(3):145–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bente DA, Forrester NL, Watts DM, et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: history, epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical syndrome and genetic diversity. Antiviral Res. 2013;100(1):159–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Vorou R, Pierroutsakos IN, Maltezou HC. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20(5):495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Papa A, Mirazimi A, Köksal I, et al. Recent advances in research on Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. J Clin Virol. 2015;64:137–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mendoza EJ, Warner B, Safronetz D, et al. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus: past, present and future insights for animal modelling and medical countermeasures. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65(5):465–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Burt FJ, Swanepoel R, Shieh WJ, et al. Immunohistochemical and in situ localization of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) virus in human tissues and implications for CCHF pathogenesis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121(8):839–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rodrigues R, Paranhos-Baccalà G, Vernet G, et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus-infected hepatocytes induce ER-stress and apoptosis crosstalk. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Codogno P, Meijer AJ. Autophagy and signaling: their role in cell survival and cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(Suppl 2):1509–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Boya P, Reggiori F, Codogno P. Emerging regulation and functions of autophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(7):713–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Levine B, Kroemer G. Biological functions of autophagy genes: a disease perspective. Cell. 2019;176(1–2):11–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Levine B. Eating oneself and uninvited guests: autophagy-related pathways in cellular defense. Cell. 2005;120(2):159–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jordan TX, Randall G. Manipulation or capitulation: virus interactions with autophagy. Microbes Infect. 2012;14(2):126–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dong X, Levine B. Autophagy and viruses: adversaries or allies? J Innate Immun. 2013;5(5):480–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Petkova DS, Viret C, Faure M. IRGM in autophagy and viral infections. Front Immunol. 2012;3:426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Richetta C, Faure M. Autophagy in antiviral innate immunity. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15(3):368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Faure M, Lafont F. Pathogen-induced autophagy signaling in innate immunity. J Innate Immun. 2013;5(5):456–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cadwell K. Crosstalk between autophagy and inflammatory signalling pathways: balancing defence and homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(11):661–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hernandez-Gea V, Hilscher M, Rozenfeld R, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces fibrogenic activity in hepatic stellate cells through autophagy. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Digaleh H, Kiaei M, Khodagholi F. Nrf2 and Nrf1 signaling and ER stress crosstalk: implication for proteasomal degradation and autophagy. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(24):4681–4694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shoji-Kawata S, Levine B. Autophagy, antiviral immunity, and viral countermeasures. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793(9):1478–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Paul P, Munz C. Autophagy and mammalian viruses: roles in immune response, viral replication, and beyond. Adv Virus Res. 2016;95:149–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kuma A, Matsui M, Mizushima N. LC3, an autophagosome marker, can be incorporated into protein aggregates independent of autophagy: caution in the interpretation of LC3 localization. Autophagy. 2007;3(4):323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(33):24131–24145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Komatsu M, Waguri S, Koike M, et al. Homeostatic levels of p62 control cytoplasmic inclusion body formation in autophagy-deficient mice. Cell. 2007;131(6):1149–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fraisier C, Rodrigues R, Vu Hai V, et al. Hepatocyte pathway alterations in response to in vitro Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever virus infection. Virus Res. 2014;179:187–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Moloughney JG, Monken CE, Tao H, et al. Vaccinia virus leads to ATG12-ATG3 conjugation and deficiency in autophagosome formation. Autophagy. 2011;7(12):1434–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gao Z, Gammoh N, Wong P-M, et al. Processing of autophagic protein LC3 by the 20S proteasome. Autophagy. 2010;6(1):126–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Arnoldi F, De Lorenzo G, Mano M, et al. Rotavirus increases levels of lipidated LC3 supporting accumulation of infectious progeny virus without inducing autophagosome formation. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Reggiori F, Monastyrska I, Verheije MH, et al. Coronaviruses Hijack the LC3-I-positive EDEMosomes, ER-derived vesicles exporting short-lived ERAD regulators, for replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7(6):500–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sharma M, Bhattacharyya S, Nain M, et al. Japanese encephalitis virus replication is negatively regulated by autophagy and occurs on LC3-I- and EDEM1-containing membranes. Autophagy. 2014;10(9):1637–1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Beale R, Wise H, Stuart A, et al. A LC3-interacting motif in the influenza A virus M2 protein is required to subvert autophagy and maintain virion stability. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15(2):239–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].English L, Chemali M, Duron J, et al. Autophagy enhances the presentation of endogenous viral antigens on MHC class I molecules during HSV-1 infection. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(5):480–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Alirezaei M, Flynn C, Wood M, et al. Pancreatic acinar cell-specific autophagy disruption reduces coxsackievirus replication and pathogenesis in vivo. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11(3):298–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Taisne C, Lussignol M, Hernandez E, et al. Human cytomegalovirus hijacks the autophagic machinery and LC3 homologs in order to optimize cytoplasmic envelopment of mature infectious particles. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Borel S, Robert-Hebmann V, Alfaisal J, et al. HIV-1 viral infectivity factor interacts with microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 and inhibits autophagy. Aids. 2015;29(3):275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Murrow L, Malhotra R, Debnath J. ATG12-ATG3 interacts with Alix to promote basal autophagic flux and late endosome function. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(3):300–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Radoshevich L, Murrow L, Chen N, et al. ATG12 conjugation to ATG3 regulates mitochondrial homeostasis and cell death. Cell. 2010;142(4):590–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Richetta C, Grégoire IP, Verlhac P, et al. Sustained autophagy contributes to measles virus infectivity. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(9):e1003599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Peyrefitte CN, Perret M, Garcia S, et al. Differential activation profiles of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus- and Dugbe virus-infected antigen-presenting cells. J Gen Virol. 2010;91(1):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.