ABSTRACT

Mitophagy, the elimination of damaged mitochondria through autophagy, promotes neuronal survival in cerebral ischemia. Previous studies found deficient mitophagy in ischemic neurons, but the mechanisms are still largely unknown. We determined that BNIP3L/NIX, a mitophagy receptor, was degraded by proteasomes, which led to mitophagy deficiency in both ischemic neurons and brains. BNIP3L exists as a monomer and homodimer in mammalian cells, but the effects of homodimer and monomer on mitophagy are unclear. Site-specific mutations in the transmembrane domain of BNIP3L (S195A and G203A) only formed the BNIP3L monomer and failed to induce mitophagy. Moreover, overexpression of wild-type BNIP3L, in contrast to the monomeric BNIP3L, rescued the mitophagy deficiency and protected against cerebral ischemic injury. The macroautophagy/autophagy inhibitor 3-MA and the proteasome inhibitor MG132 were used in cerebral ischemic brains to identify how BNIP3L was reduced. We found that MG132 blocked the loss of BNIP3L and subsequently promoted mitophagy in ischemic brains. In addition, the dimeric form of BNIP3L was more prone to be degraded than its monomeric form. Carfilzomib, a drug for multiple myeloma therapy that inhibits proteasomes, reversed the BNIP3L degradation and restored mitophagy in ischemic brains. This treatment protected against either acute or chronic ischemic brain injury. Remarkably, these effects of carfilzomib were abolished in bnip3l-/- mice. Taken together, the present study linked BNIP3L degradation by proteasomes with mitophagy deficiency in cerebral ischemia. We propose carfilzomib as a novel therapy to rescue ischemic brain injury by preventing BNIP3L degradation.

Abbreviations: 3-MA: 3-methyladenine; AAV: adeno-associated virus; ATG7: autophagy related 7; BCL2L13: BCL2-like 13 (apoptosis facilitator); BNIP3L/NIX: BCL2/adenovirus E1B interacting protein 3-like; CCCP: carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone; CFZ: carfilzomib; COX4I1: cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4I1; CQ: chloroquine; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GFP: green fluorescent protein; I-R: ischemia-reperfusion; MAP1LC3A/LC3A: microtube-associated protein 1 light chain 3 alpha; MAP1LC3B/LC3B: microtube-associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta; O-R: oxygen and glucose deprivation-reperfusion; OGD: oxygen and glucose deprivation; PHB2: prohibitin 2; pMCAO: permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion; PRKN/PARK2: parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin protein ligase; PT: photothrombosis; SQSTM1: sequestosome 1; tMCAO: transient middle cerebral artery occlusion; TOMM20: translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20; TTC: 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium hydrochloride.

KEYWORDS: BNIP3L/NIX, carfilzomib, cerebral ischemia, mitophagy, ubiquitin-proteasome pathway

Introduction

Cerebral ischemia results in high mortality and disability and remains one of the most refractory human diseases [1,2]. Besides being the source of bioenergy, mitochondria function directly in regulating programmed cell death [3] and mitochondrial damage has been well-documented as a cause of neuronal death in ischemic neurons [4]. Mitochondrial elimination by autophagy, termed mitophagy, is essential in controlling mitochondrial quality [5]. Autophagic machinery eliminates damaged mitochondria and prevents mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in ischemic neurons [6]. Enhanced mitophagy has thus been proposed as a therapeutic strategy to protect neurons from ischemic insults [7–9]. Unfortunately, few drugs can modulate mitophagy in ischemic brains [10]. Mitophagy deficiency leads to accumulation of damaged mitochondria in brains, causing bioenergetic dysfunction and neuronal inflammation [11]. Notably, mitochondria accumulate in a variety of hypoxic and/or ischemic neuronal injury models [12,13], suggesting the insufficiency of mitophagy in ischemia [7]. In particular, our previous studies showed that mitophagy can be activated by ischemia-reperfusion, while ischemia alone did not trigger mitophagy in spite of autophagy activation [7,14]. These results implied that ischemic brains without reperfusion might be rescued by restoring mitophagy. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying neuronal mitophagy deficiency in ischemic neurons remain largely unclear.

BNIP3L/NIX is located on the mitochondrial outer membrane, where it serves as a mitophagy receptor in either cell development or pathological conditions [15,16]. We previously found that Bnip3l gene deletion significantly blocked ischemia-reperfusion-induced neuronal mitophagy and consequently exacerbated ischemic brain injury. These results highlighted BNIP3L as a potential target of mitophagy for stroke intervention [6,8,17]. Nevertheless, it remained unclear how to manipulate mitophagy in ischemic neurons by regulating BNIP3L. Intriguingly, BNIP3L was reduced along with the differentiation of either erythroblast [16] or cardiac progenitor cells [18]. Likewise, reduced BNIP3L was found in several disorders with insufficient mitophagy, e.g., traumatic brain injury [19], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [20] and acute myeloid leukemia [21]. These findings implied the potential association of reduced BNIP3L with lower mitophagy activity. However, whether the abundance of BNIP3L controls the duration of mitophagy remains unclear, and how BNIP3L was reduced under pathological conditions is also ambiguous. BNIP3L forms either a monomer or homodimer in mammalian cells [22,23] and it seems that a homodimer of BNIP3L is required for its proapoptotic effects in tumor cells [24,25]. However, the contributions of homodimer and monomer of BNIP3L to mitophagy have not been clarified [26,27]. Therefore, further characterization of the molecular regulation of BNIP3L in ischemic brains may provide novel therapies for cerebral ischemia.

In the present study, we aimed to explore how neuronal BNIP3L was regulated in ischemic neurons. We unexpectedly found that BNIP3L was degraded by proteasomes, which led to mitophagy deficiency. Carfilzomib, a proteasome inhibitor for multiple myeloma therapy, protected brains from ischemic injury by rescuing BNIP3L degradation.

Results

Ischemia alone leads to neuronal mitophagy deficiency

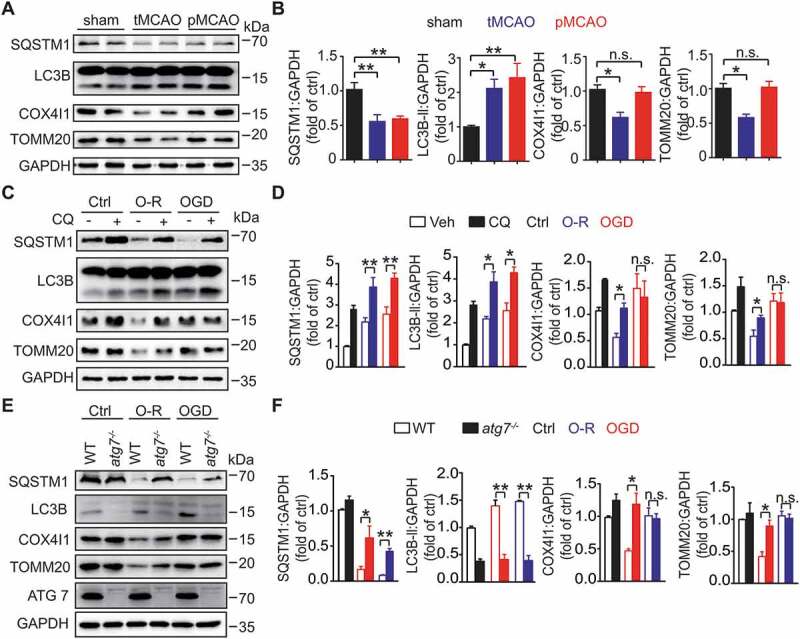

To identify mitophagy induction in ischemic brains, we determined the expression of mitophagy-related proteins in mice subjected to either transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) or permanent MCAO (pMCAO). Both tMCAO and pMCAO led to increased LC3B-II and reduced SQSTM1, indicating autophagy activation. The mitochondrial proteins COX4I1 and TOMM20, which reflect mitochondrial content, decreased in tMCAO- but not in pMCAO-treated mice brains (Figure 1A,B). These data were in line with previous observations [4,7,12,14] and implied deficiency in neuronal mitophagy with ischemia alone. To confirm this phenotype, primary cultured cortical neurons were subjected to oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD) or OGD-reperfusion (O-R) treatment. Similarly, both O-R and OGD alone caused LC3B lipidation and reduced SQSTM1. However, OGD alone failed to cause mitochondrial loss as in O-R treated neurons. We confirmed the autophagic mitochondrial loss because of chloroquine treatment resulted in further accumulation of LC3B-II and reversed the degradation of SQSTM1, TOMM20, and COX4I1 [28] (Figure 1C,D).

Figure 1.

Ischemia alone leads to neuronal mitophagy deficiency. (A) Mice were subjected to 1 h of occlusion followed by 3 h of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) or 4 h of permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (pMCAO). The expression of SQSTM1, LC3B, COX4I1, and TOMM20 in ischemic penumbra was detected by western blot. Duplicate lanes are shown for each grou(B) Semi-quantitative analyses are shown (n = 5 mice for each group). (C) Primary cultured mice cortical neurons were subjected to 1 h of oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD) followed by 1 h of reperfusion (O-R) or 2 h of OGD. The neurons were incubated with 20 μM chloroquine for 4 h prior to the OGD procedure. The protein expression of SQSTM1, LC3B, COX4I1, and TOMM20 was detected by western blot, and (D) relative protein markers were analyzed (n = 3 from independent experiments). Ctrl, control; Veh, vehicle; CQ, chloroquine. (E) Primary cultured cortical neurons of WT and Atg7fl/fl; hSyn-Cre were subjected to 1 h of OGD followed by 1 h of reperfusion (O-R) or 2 h of OGD. The protein levels of SQSTM1, LC3B, COX4I1, TOMM20, and ATG7 were detected by western blot, and (F) relative protein markers were analyzed (n = 3 from independent experiments). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed as follows: one-way ANOVA for (B, D, and F). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; n.s. vs. the indicated group

To further identify mitophagy deficiency, atg7 (autophagy related 7) knockout primary cortical neurons (Atg7fl/fl; hSyn-Cre) [29] were used. atg7 knockout blocked the mitophagy in O-R neurons but not neurons after OGD alone (Figure 1E,F). We transfected neurons with mCherry-LC3B and Mito-GFP, which labeled autophagosomes and mitochondria, respectively. Both O-R and OGD treatment increased the number of autophagosomes. OGD alone did not promote the overlap of autophagosomes with mitochondria (Fig. S1A and S1B). As an alternative approach to identify mitophagy, primary cultured neurons were transfected with Mito-QC, which is widely used to monitor mitophagy [30]. Consistent with the western blot data, O-R treatment enhanced the mitochondria ratio in mCherry-alone. In contrast, OGD alone reduced mitochondria fusion with lysosomes (Fig. S1C and S1D). Together, these data revealed that ischemia alone compromised neuronal mitophagy despite the activation of autophagy.

BNIP3L relates to mitophagy deficiency in cerebral ischemia

Since ischemia did not compromise autophagy activation either in vivo or in vitro, we thus assumed a mitophagy-specific mechanism deficiency. We examined the protein levels of PRKN/PARK2, BNIP3L, FUNDC1, BCL2L13, PHB2 (prohibitin 2) and BNIP3 in pMCAO brains [6,31–34]. The results showed significant BNIP3L reduction with pMCAO treatment while the expression of PRKN, FUNDC1, BCL2L13, PHB2 and BNIP3 remained intact. These results suggested that these mitophagy receptors, excepting BNIP3L, may have little impact on mitophagy deficiency in ischemic brains (Fig. S2). To confirm the involvement of BNIP3L loss in mitophagy deficiency, we infected the mice brain cortex and striatum with adeno-associated viruses carrying the cDNA of GFP-BNIP3L (AAV-GFP-Bnip3l) two weeks prior to pMCAO. The mitophagy deficiency was rescued by ectopic expression of BNIP3L as revealed by loss of mitochondrial markers COX4I1 and TOMM20 (Figure 2A,B).

Figure 2.

BNIP3L relates to mitophagy deficiency in cerebral ischemia. (A) Mice were infected with AAV-GFP-Bnip3l or AAV-GFThe mice were subjected to pMCAO for 4 h, then the protein levels of GFP, SQSTM1, LC3B, COX4I1 and TOMM20 in brain tissues were determined by western blot. Empty arrows indicate exogenous BNIP3L. Duplicate lanes are shown for each grou(B) Semi-quantitative analyses of SQSTM1, LC3B, COX4I1 and TOMM20 protein levels are shown (n = 3 mice for each group). (C) Primary neurons were subjected to OGD for 1 h. The expression of BNIP3L and TOMM20 were detected by western blot. Semi-quantitative analyses are shown (n = 3 from independent experiments). (D) The neurons overexpression Flag-BNIP3L were subjected to OGD for 1 h, and the expression of Flag-BNIP3L and TOMM20 were detected by western blot (n = 3 from independent experiments). (E) Mice were subjected to 1, 3 or 6 h of pMCAO. The BNIP3L, PRKN, FUNDC1, BCL2L13, PHB2, SQSTM1, LC3B, COX4I1 and TOMM20 protein levels were determined by western blot. Black arrows indicate endogenous BNIP3L. Duplicate lanes are shown for each grou(F-I) Analyses of the correlations between BNIP3L, PRKN, FUNDC1, BLC2L13, PHB2, and mitochondrial proteins are shown (n = 3 mice for each group). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed as follows: one-way ANOVA for (B and F-I) and t-test for (C and D). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s. vs. the indicated group

In line with these findings, we found that endogenous BNIP3L decreased after OGD treatment in primary cultured neurons, while the mitochondrial content was not significantly affected (Figure 2C). These phenotypes were rescued by overexpression of Flag-BNIP3L (Figure 2D). The immunostaining showed the same results (Fig. S3). Because the abundance of mitophagy receptors cannot reflect the mitochondrial mass [35–37], we determined the COX4I1, TOMM20, and expression of BNIP3L along with the duration of pMCAO (Figure 2E). Results showed mitochondrial accumulation (mitophagy deficiency) and BNIP3L loss along with pMCAO duration. These data indicated an increasing duration of mitophagy deficiency. The expressions of PRKN, FUNDC1, BCL2L13 and PHB2 were not significantly altered after pMCAO. Abundance analysis of the correlations of PRKN, FUNDC1, BCL2L13 and PHB2 with mitochondrial marker COX4I1 showed no significant changes (Figure 2F).

BNIP3L can be detected at 40 and 80 kDa, representing the monomer and homodimer of BNIP3L, respectively [38]. The quantification of opti-density of immunoblots showed that the BNIP3L dimer decreased significantly and the monomeric form decreased at a slower rate along with the duration of pMCAO (Figure 2G). We then determined the correlation of BNIP3L dimer/monomer with mitochondrial content in each individual sample with distinct pMCAO duration. The results clearly indicated a higher correlation of BNIP3L dimer loss than monomer loss with the increased mitochondrial content (Figure 2H,I). Overall, we found that BNIP3L dimer loss was related to mitophagy deficiency in cerebral ischemia.

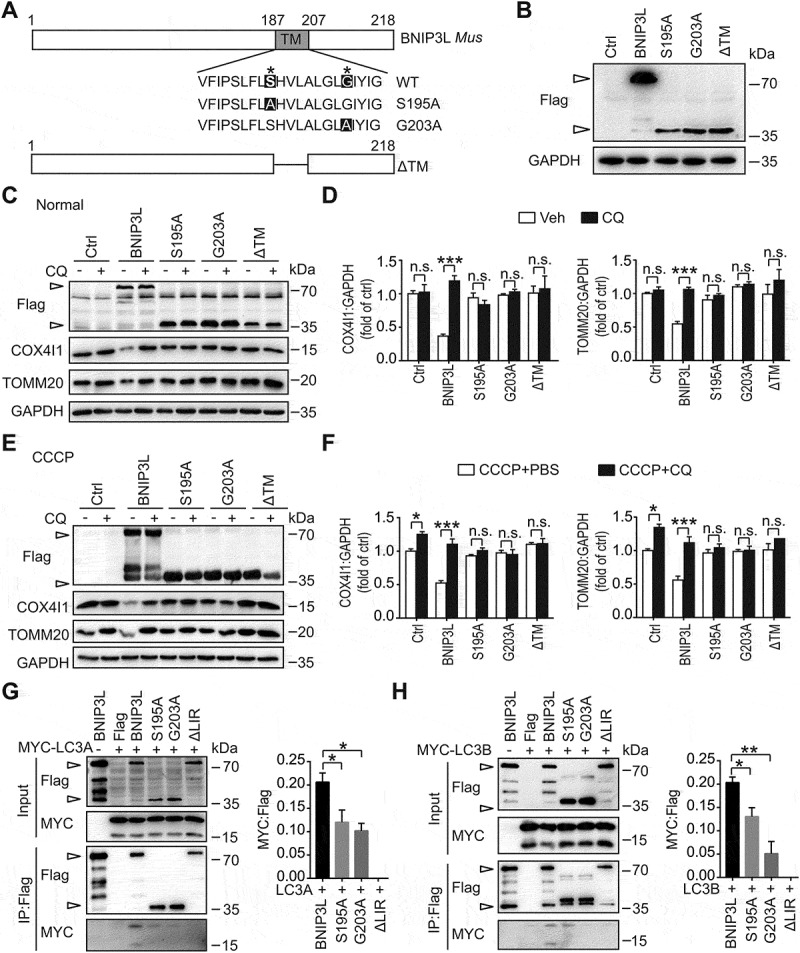

BNIP3L rescues mitophagy deficiency and protects against cerebral ischemia

The aforementioned results raised questions about the requirement of BNIP3L dimer and monomer in mitophagy activation. To investigate this, we constructed the BNIP3L monomer by mutating the transmembrane (TM) domain of BNIP3L (S195A, G203A) [39] (Figure 3A). Constructs of the single site-specific BNIP3L mutants (S195A, G203A) showed only a monomer form in the immunoblot (Figure 3B). Moreover, these mutants remained localized to the mitochondria in COS7 cells and primary neurons while the TM domain deletion mutant (ΔTM) lost mitochondrial distribution [25] (Fig. S4A and S4B). We then transfected HeLa cells with 3× Flag-fused BNIP3L or its mutants (S195A, G203A and ΔTM). Results showed that the mitochondrial contents (COX4I1 and TOMM20) were significantly reduced after wild-type BNIP3L overexpression, while treatment of S195A and G203A mutants had a minor effect in inducing mitochondrial loss in normal conditions (Figure 3C,D). The wild-type BNIP3L still induced mitochondrial reduction under CCCP treatment. In contrast, both S195A and G203A mutation failed to reinforce CCCP-induced mitochondrial loss (Figure 3E,F).

Figure 3.

BNIP3L monomeric mutants failed to induce mitophagy in HeLa cells. (A) Structural diagram of mouse BNIP3L and mutants of the transmembrane (TM) domain were shown. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with Flag, Flag-Bnip3l, Flag-Bnip3lS195A, Flag-Bnip3lG203A, or Flag-Bnip3lΔTM for 24 h. The relative protein levels in HeLa cells were determined by western blot. Empty arrows indicate exogenous BNIP3L. (C) Hela cells were transfected with Flag, Flag-Bnip3l, Flag-Bnip3lS195A, Flag-Bnip3lG203A, or Flag-Bnip3lΔTM for 24 h. Cells were treated with PBS as a control or 20 μM chloroquine for 4 h. The expression of Flag, COX4I1, TOMM20 and GAPDH were determined by western blot. (D) Semi-quantitative analyses of COX4I1 and TOMM20 protein levels are shown (n = 3 from independent experiments). (E) HeLa cells were transfected with Flag, Flag-Bnip3l, Flag-Bnip3lS195A, or Flag-Bnip3lG203A, Flag-Bnip3lΔTM for 24 h. Cells were treated with PBS as a control or 20 μM chloroquine for 4 h and then incubated with CCCP (10 μM) for 6 h. The exogenous expression of BNIP3L and mitochondrial markers in HeLa cells were assessed by western blot. (F) Semi-quantitative analyses of COX4I1 and TOMM20 protein levels are shown (n = 3 from independent experiments). (G-H) Protein-protein interactions of MYC-LC3 with Flag, Flag-BNIP3L, Flag-BNIP3LS195A, Flag-BNIP3LG203A, Flag-BNIP3LΔLIR were confirmed by immunoprecipitation in BNIP3L KO HeLa cells. Plasmids were co-transfected for 24 h. After 6 h of 10 μM CCCP incubation, the expression of LC3s and BNIP3L were assessed by western blot. Empty arrows indicate exogenous BNIP3L. Semi-quantitative analyses of IP: MYC-LC3-I/IP: Flag are shown (n = 3 from independent experiments). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed as follows: one-way ANOVA for (D, F, G and H). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s. vs. the indicated group

Furthermore, exogenous BNIP3L reduced COX4I1 and TOMM20 levels, which was reversed by chloroquine, indicating mitophagic degradation. However, the BNIP3L monomer mutants were not able to reduce the mitochondrial contents (Figure 3C-F). MitoTracker Red was used to visualize the mitochondrial mass after BNIP3L and mutant transfection in HeLa cells (Fig. S4 C). Compared with BNIP3L, the monomer mutants failed to decrease the mitochondrial area (Fig. S4D). BNIP3L interacts with ATG8-family proteins (LC3 and GABARAP subfamilies) and thus induces mitophagy [15]. By carrying out immunoprecipitation in HeLa cells with BNIP3L gene deletion by CRISPR-Cas9, we recapitulated the interaction of wild-type BNIP3L with either lipidated forms of LC3A or LC3B. However, the interaction of mutant BNIP3Ls with unlipidated LC3s was weaker (Figure 3G,H). Taken together, these data indicated the incompetency of BNIP3 L monomer for inducing mitophagy and suggested the requirement of BNIP3L dimer to activate mitophagy.

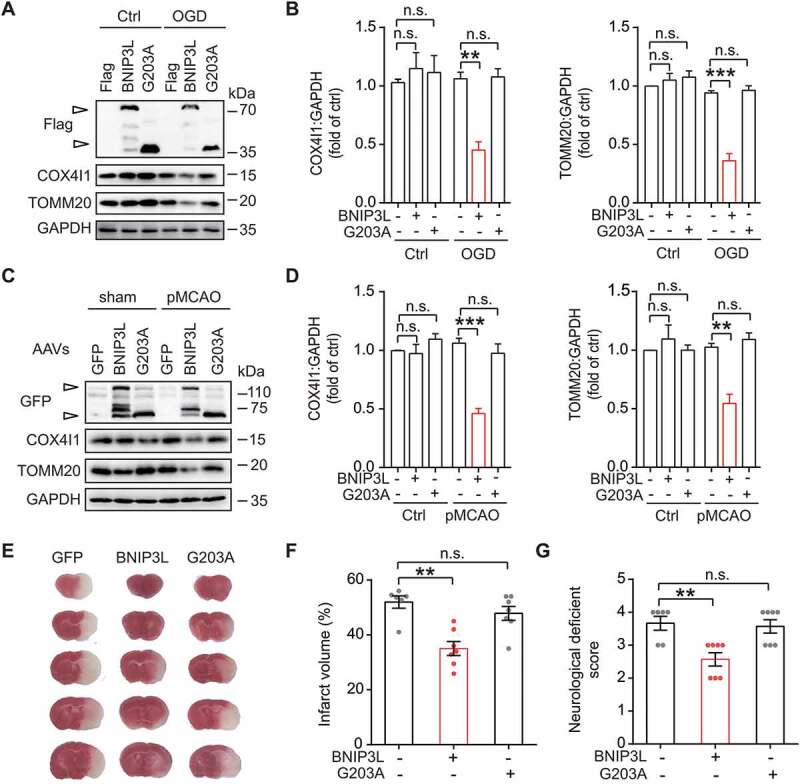

We next asked whether wild-type BNIP3L may rescue neuronal mitophagy deficiency in cerebral ischemia. After being subjected to OGD, the primary neurons transfected with Flag-BNIP3L significantly reduced mitochondrial content by measuring COX4I1 and TOMM20 immunoblots. The BNIP3LG203A mutant construct, however, failed to reduce mitochondrial mass in OGD-treated neurons (Figure 4A,B). The neuron immunostaining showed the same results (Fig. S5). These data provided evidence supporting the involvement of wild-type BNIP3L in mitophagy activation in ischemia. This notion was further verified in ischemic mice brains by determining mitophagy following virus-mediated expression. Results showed that GFP-BNIP3L transduction to brains reversed the accumulation of mitochondrial markers COX4I1 and TOMM20 after pMCAO treatment. In contrast, GFP-BNIP3LG203A did not alter the mitochondrial mass in ischemic brains (Figure 4C,D). These data from in vitro and in vivo ischemic models indicated that wild-type BNIP3L rescued mitophagy deficiency in ischemic brains.

Figure 4.

BNIP3L rescues mitophagy deficiency and protects against cerebral ischemia. (A) Primary cultured cortical neurons transfected with Flag, Flag-Bnip3l, or Flag-Bnip3lG203A were subjected to 1 h of OGD. The exogenous expression of Flag, COX4I1, TOMM20 and GAPDH were determined by western blot. (B) Semi-quantitative analyses of COX4I1 and TOMM20 are shown (n = 3 from independent experiments). (C) Mice were infected with AAV-GFP, AAV-GFP-Bnip3l or AAV-GFP-Bnip3lG203A for at least two weeks and then subjected to 6 h of pMCAO. The AAVs, COX4I1 and TOMM20 protein levels in brain tissues were determined by western blot. Empty arrows indicate exogenous BNIP3L. Duplicate lanes are shown for each grou(D) Semi-quantitative analyses of COX4I1 and TOMM20 are shown (n = 3 mice for each group). (E) Mice brains were infected with AAVs expressing GFP, GFP-Bnip3l, or GFP-Bnip3lG203A and then subjected to 24 h of pMCAO. The representative TTC-stained brain slices from each group are shown. (F) The brain infarct volumes and (G) neurological deficit scores of each group were determined (n = 6–7 mice for each group). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed as follows: one-way ANOVA for (B, D, F and G). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s. vs. the indicated group

Our previous studies indicated the neuroprotective effects of mitophagy against ischemic insults [6,31]. To further test whether mitophagy rescued by wild-type BNIP3L may also produce neuroprotective effects, AAV-GFP-Bnip3l and AAV-GFP-Bnip3lG203A were separately injected into wild-type mice brains. The ectopic BNIP3L expression produced significant protection by reducing the brain infarct volumes from 51.9% ± 2.2% to 35.1% ± 2.5% (Figure 4E,F). This neuroprotection was also reflected by improved neurological deficit score (NDS) (3.67 ± 0.21 vs. 2.57 ± 0.20, P < 0.01, Figure 4G) 24 h after ischemia onset. As a comparison, the BNIP3LG203A failed to rescue the infarct volumes (51.9% ± 2.2% vs. 47.8% ± 2.5%, n.s., Figure 4F) as well as NDS (3.67 ± 0.21 vs. 3.57 ± 0.20, n.s., Figure 4G). We thus concluded that wild-type BNIP3L was required for its neuroprotective effect against ischemic injury.

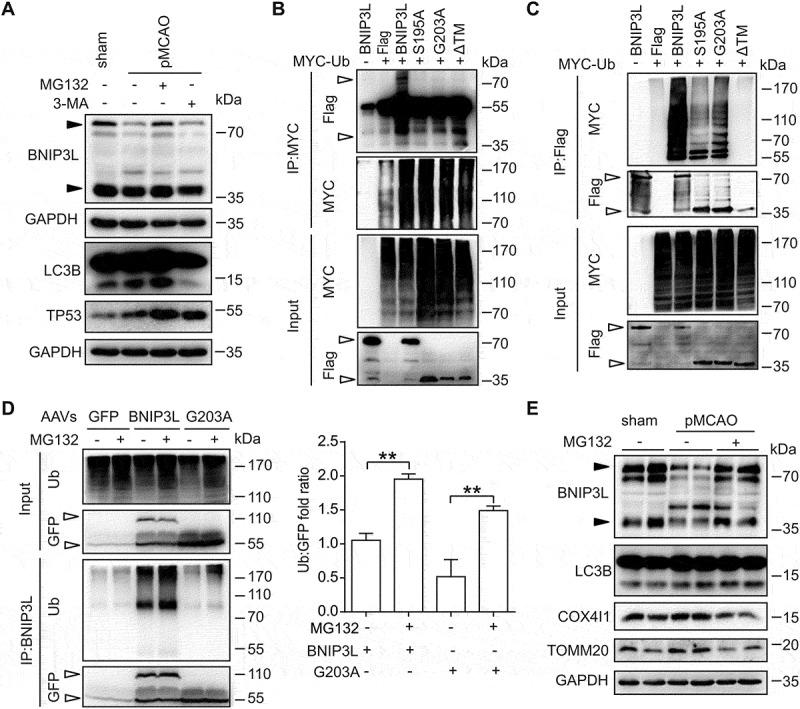

BNIP3L is degraded by ubiquitin-proteasome pathway

Our data supported an intimate link of BNIP3L loss with mitophagy deficiency in cerebral ischemia. Multiple lines of evidence indicated that both autophagy-lysosome pathway and ubiquitin-proteasome pathway were activated in ischemic brains. We thus blocked these two degradation pathways by 3-MA and MG132, respectively. The LC3B-II protein levels were inhibited by 3-MA. MG132 treatment led to an increase in level of TRP53/p53 [40], suggesting proteasome inhibition (Figure 5A). The proteasome inhibitor MG132, rather than autophagy inhibitor 3-MA, rescued wild-type BNIP3L degradation. This result suggested that that proteasomal activation was involved in wild-type BNIP3L loss. To investigate this, we determined the ubiquitination of wild-type BNIP3L and its mutants by immunoprecipitation in BNIP3L-/- HeLa cells. Wild-type BNIP3L was more ubiquitylated compared with its monomer mutants (Figure 5B,C). We cannot exclude the possibility that the smear of ubiquitin chains on wild-type BNIP3L comes from other proteins interacting with BNIP3L and being ubiquitinated. Further studies are needed to address this issue.

Figure 5.

BNIP3L is degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. (A) The mice were injected (i.c.v.) with 3-MA (7.5 μg) or MG132 (4 mg/kg) at the onset of occlusion and then subjected to 6 h of pMCAO. The BNIP3L, LC3 and TP53 protein levels were determined by western blot. (B-C) Protein-protein interactions of MYC-Ub with Flag-BNIP3L, Flag-BNIP3LS195A, Flag-BNIP3LG203A, or Flag-BNIP3LΔTM were confirmed by immunoprecipitation in BNIP3L KO HeLa cells. Plasmids were co-transfected for 24 h. CCCP (10 μM) and MG132 (10 μM) were incubated for 6 h before harvesting. The protein levels of ubiquitin and exogenous expression of BNIP3L were detected by using anti-Flag and anti-MYC antibodies, respectively. Empty arrows indicate exogenous BNIP3L. (D) The bnip3l-/- mice were infected with AAVs expressing GFP, GFP-Bnip3l, or GFP-Bnip3lG203A for two weeks and then subjected to 6 h of pMCAO. The protein-protein interactions of ubiquitin and overexpression of BNIP3L in vivo were determined by immunoprecipitation. The ubiquitylation levels of exogenous BNIP3L were detected by using anti-ubiquitin and anti-BNIP3L antibodies. A ratio t-test was applied (n = 3 from independent experiments). (E) The wild-type mice treated with MG132 (4 mg/kg) at the onset of occlusion were subjected to 6 h of pMCAO. Duplicate lanes are shown for each group. The BNIP3L, LC3B, COX4I1 and TOMM20 protein levels were assessed by western blot. Black arrows indicate endogenous BNIP3L. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed as follows: t-test for (D). **P < 0.01 vs. the indicated group

We next determined whether wild-type BNIP3L was ubiquitylated in ischemic brains. To this end, mice brains were injected with viruses to express the wild-type or monomer BNIP3L in bnip3l-/- mice. After being subjected to pMCAO, ubiquitination of BNIP3Ls was assayed using immunoprecipitation. Both BNIP3L dimer and monomer were ubiquitinated, and the ubiquitylation was further increased with MG132 treatment (Figure 5D). Additionally, MG132 prevented BNIP3L loss in ischemic mice brains when administered systemically. Rescue of BNIP3L loss was accompanied by enhanced mitophagy as revealed by decreased levels of COX4I1 and TOMM20 (Figure 5E). Taken together, these data indicated that BNIP3L was degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway and thus led to mitophagy deficiency in ischemic brains.

Carfilzomib rescues BNIP3L degradation and protects against ischemic injury

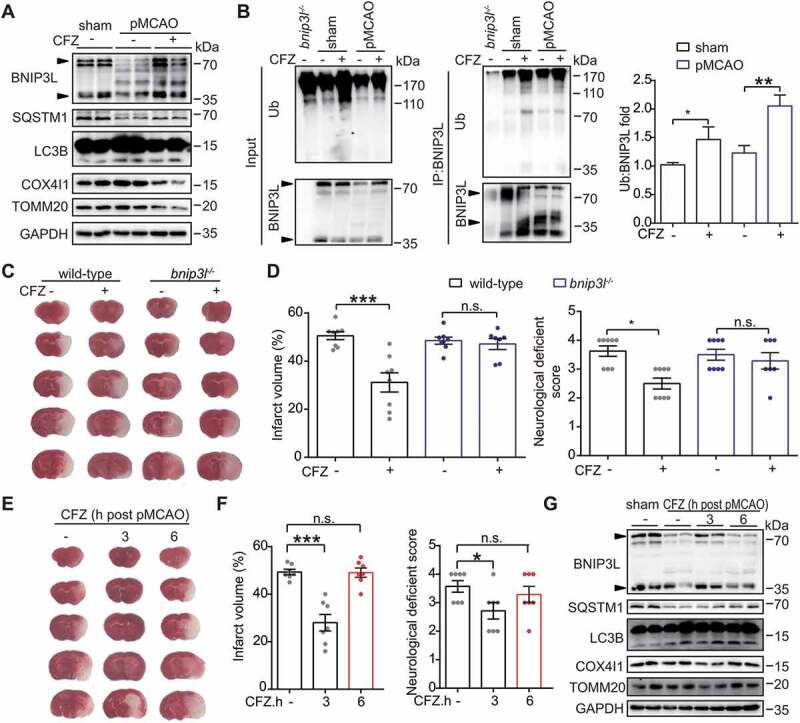

The fact that BNIP3L degradation by proteasomes contributed to mitophagy deficiency in ischemic brains led us to hypothesize that proteasome inhibitors may serve to prevent BNIP3L loss and thus alleviate ischemic brain injury. Some proteasome inhibitors are used in multiple myeloma therapy [41]. Among these drugs, carfilzomib (CFZ) showed advantages in pharmacokinetics and safety [42]. We confirmed that BNIP3L degradation caused by pMCAO was blocked by CFZ treatment. As a consequence, the administration of CFZ reduced the COX4l1 and TOMM20 protein levels, indicating the restoration of mitophagy deficiency (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Carfilzomib (CFZ) rescues BNIP3L degradation and protects against ischemic injury. (A) Mice treated with 2 mg/kg carfilzomib at the onset of occlusion were subjected to 6 h of pMCAO. The protein levels of BNIP3L, SQSTM1, LC3B, COX4I1 and TOMM20 were detected by western blot. Duplicate lanes are shown for each group. (B) Wild-type or bnip3l-/- mice were injected with CFZ at the onset of occlusion and then subjected to 6 h of pMCAO. The protein-protein interactions of BNIP3L and ubiquitin after CFZ treatment were detected by immunoprecipitation in vivo. The ubiquitylation levels of endogenous BNIP3L were detected using anti-ubiquitin and anti-BNIP3L antibodies. A ratio t-test was applied (n = 3 from independent experiments). (C) Wild-type or bnip3l-/- mice were given CFZ at the onset of occlusion and subjected to pMCAO for 24 h. The brain slices were stained by TTC and representative slices from each group are shown. (D) The brain infarct volumes and neurological deficit scores of each group were determined (n = 6–8 mice for each group). (E) The mice were treated with CFZ at 3 or 6 h after the onset of occlusion. Representative brain slices are shown. (F) After 24 h of occlusion, the infarct volumes were determined by TTC staining and neurological deficit scores were evaluated (n = 6–7 mice for each group). (G) The protein levels of BNIP3L, SQSTM1, LC3B, COX4I1 and TOMM20 were determined by western blot. Duplicate lanes are shown for each grouBlack arrows indicate endogenous BNIP3L. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed as follows: t-test for (B); one-way ANOVA for (D and F). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s. vs. the indicated group

CFZ also led to accumulation of total ubiquitin in ischemic brains. In particular, after pull-down of BNIP3L in ischemic brains, we found that CFZ treatment increased the level of ubiquitylated BNIP3L (Figure 6B). These data strengthened the notion that BNIP3L was ubiquitylated in ischemic brains. We next determined the neuroprotective effect of CFZ in the pMCAO model. CFZ (2 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally at the onset of ischemia. The infarct volumes and NDS were determined 24 h after injury. Treatment with CFZ significantly reduced the brain infarct volumes (50.6% ± 1.6% to 31.2% ± 3.9%, P < 0.001) and NDS (3.62 ± 0.18 vs. 2.50 ± 0.19, P < 0.05, Figure 6C,D). Importantly, neuroprotection from CFZ treatment was almost abolished in bnip3l-/- mice, suggesting that BNIP3 L was required for the therapeutic effects of CFZ.

Short therapeutic time-window is a major limitation of anti-stroke drugs. To address the time-window of CFZ for acute stroke therapy, CFZ was administered to mice at 3 or 6 h after ischemia onset. Our results showed that administration of CFZ at 3 h after pMCAO was still competent to alleviate brain infarct volumes (49.3% ± 1.1% to 28.0% ± 3.4%, P < 0.001) as well as NDS (3.56 ± 0.20 vs. 2.71 ± 0.28, P < 0.05, Figure 6E,F), but delayed administration at 6 h abolished the benefits of CFZ treatment. These results suggested that the effective time-window of CFZ for stroke therapy may extend to at least 3 h post-ischemia. We identified the BNIP3L in ischemic brains and found that delayed administration of CFZ at 3 h, but not 6 h, rescued BNIP3L loss as well as mitophagy deficiency (Figure 6G). This observation further emphasized that BNIP3L is associated with effective mitophagy in ischemic brains.

We further determined whether CFZ treatment may also attenuate chronic ischemic brain injury. To do this, mice were subjected to photothrombosis (PT) [43] and their motor function was measured every other day based on a grid-walking task and forelimb symmetry in the cylinder task over the next 13 d. We found that CFZ treatment (2 mg/kg, i.p.) every other day significantly reduced the number of foot faults and the forelimb asymmetry during the 13 d after PT onset (Fig. S6A and S6B). The brain infarct volumes were detected at 13 d after PT using toluidine blue stain. The brain infarct volumes were significantly decreased (saline 0.85 ± 0.07 mm3 vs. CFZ 0.59 ± 0.04 mm3, P < 0.05, Fig. S6 C and S6D), indicating that CFZ treatment could reduce infarct volumes after stroke. Taken together, these data suggested that CFZ could be a promising drug for stroke.

Discussion

In the present study, we identified a previously undetermined link between BNIP3L degradation and mitophagy deficiency in ischemic brains. BNIP3L dimer underwent a time-dependent decrease along with accumulation in ischemic brains (Figure 2E). Moreover, ectopic expression of wild-type BNIP3L, but not its monomer, reversed mitophagy deficiency (Figures 3 and 4). Of note, neuronal autophagy was not impaired by ischemia (Figure 1), further suggesting that mitophagy deficiency was not caused by defective autophagy machinery. We previously found that mitophagy was activated in brains that underwent ischemia-reperfusion (I-R) in which BNIP3L dimer was not reduced [14]. Conversely, bnip3l-/- caused mitophagy deficiency in I-R [6]. Prior to this study, little was known about the mechanisms of neuronal mitophagy deficiency under ischemic conditions [44,45]. Based on our results, we concluded that BNIP3L degradation played a causative role in mitophagy deficiency of ischemic brains.

Another finding of the present study is that BNIP3L monomer mutants failed to induce mitophagy. Although BNIP3L is present as both a dimer and monomer in cells, their respective contributions to mitophagy remained largely unexplored. As a result, BNIP3L was unequivocally determined to be a mitophagy receptor in most studies [46,47]. Previous research indicated that BNIP3, the homolog of BNIP3L [48], formed a homodimer to promote autophagic flux and cell death [49]. Paradoxically, it remained undetermined whether BNIP3L dimer would be indispensable for its biological functions [24]. BNIP3L dimer loss showed a much stronger correlation with mitophagy deficiency than its monomeric form in ischemic brains (Figure 2H,I). Furthermore, the single site-specific mutations (S195A, G203A) of the TM domain in BNIP3L formed only monomer and were sufficient to abolish the mitophagy activation (Figure 3C-F). BNIP3L monomer failed to rescue mitophagy deficiency in ischemic neurons and brains (Figure 4A-D). Our results highlighted that the monomer mutants (S195A and G203A) were not sufficient to induce mitophagy. Neurons prohibit mitophagy by degrading BNIP3L and may restore mitophagy by allowing homodimerization of the remaining BNIP3L monomers. This mechanism may provide a way for ischemic neurons to promptly control mitophagy. In addition, although mutant BNIP3L (S195A and G203A) showed only the monomeric form, we cannot exclude the possibility that the mutants may have effects besides preventing dimerization. Moreover, a dramatic drop in intracellular ATP or glycolysis perturbation, as a stress caused by ischemia, may also block mitophagy [50–52]. Although we found BNIP3L loss was attributed to proteasomal degradation, it was not clear whether this degradation was triggered by energy crisis. It remains unclear whether and how glucose metabolism alterations and BNIP3L degradation work together to regulate neuronal mitophagy in ischemia-related scenarios.

Detailed mechanisms of BNIP3L homodimer in triggering mitophagy were not fully understood. An emerging study added a mechanistic perspective to our findings that BNIP3L dimerization may associate with its phosphorylation in TM domain [53]. Mutations in the TM domain did not alter their mitochondrial location (Fig. S4A and S4B). We confirmed that the mitochondrial distribution of BNIP3L was required (compared with the TM domain deletion mutation) for mitophagy. However, here we showed that anchoring to mitochondria was not sufficient for BNIP3L to serve as a mitophagy receptor. Remarkably, BNIP3L homodimer was prone to interact with LC3A/B-II and the mutants also had a weaker interaction with LC3A/B-I (Figure 3E,F). It is likely that the homodimer of BNIP3L might alter the conformation of its LIR motif, which faces LC3A/B-II proteins and thus facilitates recognition of mitochondria by autophagosomes. In addition to its function in inducing mitophagy, we revealed the requirement of BNIP3L homodimer for its neuroprotective effect in ischemic brains (Figure 4E-G). The neuroprotective feature of BNIP3L was distinct from that of BNIP3, which promotes cell death in its monomeric form [54]. The present study emphasized the previously underestimated roles of BNIP3L dimer in mitophagy activation and advanced our understanding of how BNIP3L serves to protect ischemic brain injury [6]. Therefore, promoting BNIP3L dimer formation in ischemic brains could be a promising strategy in rescuing ischemic brain injury, which should be addressed in future studies.

Ubiquitination has been shown to engage in mitophagy regulation in ischemic neurons [55,56] but the detailed mechanisms have not been fully illustrated. Here we showed, for the first time, that BNIP3L underwent proteasome-dependent rather than autophagy-dependent degradation. Ubiquitylated BNIP3L, particularly in its dimeric form, accumulated after ischemia (Figure 5), but the ubiquitination sites and corresponding E3 ligases for BNIP3L degradation should be further addressed. Importantly, proteasomal inhibitors, MG132 and carfilzomib prevented BNIP3L degradation as well as mitophagy deficiency (Figures 5E and 6A). The BNIP3L loss-induced mitophagy deficiency was significant for ischemic neuronal injury, since restored BNIP3L attenuated brain infarct volumes and NDS (Figure 4E-G). We thus hypothesized that preventing BNIP3L degradation could be a novel therapy for cerebral ischemia. As expected, a single dosage of carfilzomib at the onset of ischemia showed significant neuroprotection in the MCAO model.

Carfilzomib is a selective proteasomal inhibitor approved by the FDA for multiple myeloma [57]. Carfilzomib showed improved safety profiles over bortezomib, another proteasomal inhibitor with profound neurotoxicity [58]. Some other studies indicated the neuroprotection of proteasome inhibitors [59,60], but it was not fully understood how proteasome inhibition attenuated ischemic injury [61,62]. We found that BNIP3L deletion abolished the neuroprotection of carfilzomib (Figure 6C,D), indicating that BNIP3L-mediated mitophagy was the prominent mechanism, if not the only mechanism, underlying the benefits of proteasomal inhibitors. We cannot exclude that other pathways induced by proteasomal blockage may also contribute to neuronal survival besides mitophagy induction. For example, proteasomal inhibition altered neuronal glucose metabolism, which may also promote neuronal survival [63]. Surprisingly, we also found that the administration of carfilzomib as late as 3 h after ischemia onset was still effective in rescuing brain injury. Prolonged administration of carfilzomib to 6 h failed to alleviate brain injury (Figure 6E,F). Coincidently, BNIP3L cannot be restored by carfilzomib at 6 h after ischemia, which further strengthened the significance of BNIP3L-mediated mitophagy in ischemic brains. Finally, we identified the efficacy of carfilzomib in the chronic ischemia model (Fig. S6). Although more complicated pathophysiological mechanisms may be involved, a variety of studies indicated the importance of neuronal mitochondrial quality in the late phases after stroke [64]. Overall, this is the first demonstration of carfilzomib as a promising therapy for diverse states of stroke.

Taken together, our work has unraveled critical contributions of BNIP3L degradation to compromised mitophagy in ischemic brains. Preventing BNIP3L degradation by inhibiting the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway rescued mitophagy deficiency and attenuated cerebral ischemic injury. We identified carfilzomib, a proteasomal inhibitor, as a promising strategy for stroke therapy.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice and male BALB/c mice weighing 22–25 g (8–10 weeks old) were used. Mice were raised on a 12 h light/dark cycle with free access to water and food. The bnip3l-/- mice (BALB/c strain background) were provided by Prof. Paul Ney (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital). The Atg7fl/fl mice were kindly provided by Masaaki Komatsu (Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science, Tokyo, Japan). All experiments were approved by and conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Zhejiang University Animal Experimentation Committee and were in complete compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Efforts were made to reduce any pain and the number of animals required.

MCAO mouse models and drug administration

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane during surgery. Cerebral blood flow (CBF) was detected in the middle cerebral artery (MCA) by laser Doppler flowmetry (Model Moor VMS-LDF2, Moor Instruments Ltd, UK). A fiber-optic probe was fixed to the skull from 2-mm caudal to bregma and 6-mm lateral to midline over the cortex supplied by the proximal part of the right MCA. A 6–0 nylon monofilament suture, blunted at the tip and coated with 1% poly-l-lysine, was inserted 10 mm into the internal carotid to occlude the origin of the MCA. Animals were excluded from the study if the reduction in CBF was less than 80%. Body temperature was maintained at 37°C by a heat lamp (FHC, Bowdoinham, ME, USA) until the mice woke uFor transient MCAO, reperfusion was allowed 1 h after ischemia by gently removing the monofilament suture. Focal cerebral ischemia was induced by MCAO without reperfusion.

Mice were given an intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection of 7.5 μg 3-MA (Sigma, M9281) at the onset of ischemia in pMCAO as we described previously [7]. MG132 (Selleckchem, S2619) was injected (4 mg/kg, i.c.v.) at the onset of ischemia. CFZ (Selleckchem, S2853) was also injected intraperitoneally (2 mg/kg, i.p.) at ischemia onset and at 3 h or 6 h after ischemia. Control mice were injected with the same volume of saline.

Neurological deficit scores were evaluated at 24 h after MCAO as follows: 0, no deficit; 1, flexion of contralateral forelimb upon lifting the whole animal by the tail; 2, circling to the contralateral side; 3, falling to the contralateral side; and 4, no spontaneous motor activity.

Mice were sacrificed using a lethal dose of isoflurane at 24 h after surgery and brain sections were stained with 2,3,5, -triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC; 0.25%; Sigma, T8877). Brain infarct volumes were quantified with ImageJ software and determined by an indirect method that corrects for edema [6].

Cell culture, OGD/O-R procedures

For culturing primary cortical neurons, pregnant mice with embryonic (E17) fetuses were used. The primary cortical neuronal culture experiments were performed as described previously [31]. Briefly, the cortical neurons of fetal mice were digested with 0.25% trypsin (Invitrogen, 25,200–056). Approximately 2 × 105 cells/cm2 were seeded onto poly-L-lysine (10 μg/ml)-coated plates and dishes. The neurons were cultured in Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen, 21,103–049) containing 2% B27 (Invitrogen,17,504–044), 10 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, 15,140–122) and 0.5 mmol/L glutamine (Gibco, 25,030,081) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 + 95% N2. Cultures were maintained for 7 d before further treatment and were routinely observed under a phase-contrast inverted microscope. To produce atg7 knockout neurons, pregnant Atg7fl/fl mice with embryonic (E17) fetuses were used. At the fifth day, Atg7fl/fl cortical neurons (2 × 106) were transfected with hSyn-Cre virus (2 μl; Obio Technology Crop., H4942). Neurons were maintained for 2 d before further treatment.

For OGD treatment, cells were washed twice with glucose-free DMEM (Invitrogen, 12,800–017), and then refreshed with O2- and glucose-free DMEM (pre-balanced in an O2-free chamber at 37°C). Then, we put the neurons in a sealed chamber (Billups Rothenburg, MIC-101) ventilated with mixed gas (5% CO2 + 95% N2) for 7 min at 25 L/min. The chambers were sealed and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. OGD-reperfusion (O-R) was performed by adding oxygen and glucose to the culture medium for 1 h at 37°C.

BNIP3L gene knockout using CRISPR-Cas9 system in HeLa cells

To knockout BNIP3L, two gRNAs (5ʹ-CGGCGGCGGCTCGACTAGGT-3ʹ, 5ʹ-GCGGCGGCGGCTCGACTAGG-3ʹ) targeting the adjacent downstream sequence of its start codon were designed using http://crispr.mit.edu/and inserted into a pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP plasmid (Addgene, 48,138; deposited by Liang Fang) according to a previously described protocol [65]. HeLa cells (ATCC, CCL-2) were co-transfected with two plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 11,668,027), and 48 h after transfection, GFP+ cells were FAC-sorted into 96-well plates as single cells to generate mutant cell clones. The successful knockout was validated using western blot.

Transfection

p3× Flag-Bnip3l, and p3× Flag-Bnip3lG203A were transfected into primary cultured neurons using Amaxa electroporation (Lonza, VPG-1001) as described previously [14]. Briefly, the primary neurons (5 × 106) were electroporated with 3 μg plasmids. The cuvette with cell/DNA suspension was inserted into the Nucleofector Cuvette Holder. After electroporation, the cells were resuspended in the medium mentioned above and then transferred into the prepared culture dishes. The dishes were maintained in an incubator for 7 d at 37°C. The plasmids were transfected into wild-type HeLa and BNIP3L KO HeLa according to the jet PRIME (Polyplus, nl14-15) protocol.

Lentivirus injection in vivo

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and mounted in a stereotaxic apparatus (Stoelting, 512,600) and adeno-associated virus (AAV, designed, produced and identified by Obio Technology Crop., Ltd., Shanghai, China) including AAV-GFP, AAV-GFP-Bnip3l, and AAV-GFP-Bnip3lG203A (1 μl) were injected into the cortex (AP + 0.02 mm; L − 3.2 mm; V − 1.5 mm) and corpus striatum (AP + 0.5 mm; L − 2.0 mm; V − 3.0 mm) with a 5-μl syringe and a 34 gauge needle at 100 nl/min using an injection pump (Micro 4, WPI, Sarasota, Fl, USA). After each injection, the needle was left in place for an additional 10 min and then slowly withdrawn. The virus was allowed to express target proteins for a minimum of 2 weeks.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

Brain tissues and cells were homogenized in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 [Diamond, A110694], 1% sodium deoxycholate [Sigma-Aldrich, 30,970], 0.1% SDS [Biofroxx, 3250GR500]) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 04693132001). The samples come from three independent experiments. A 40 μg aliquot of protein from each sample was separated using SDS-PAGE. The following primary antibodies were used: ATG7 (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, 8558 T), BCL2L13 (1:1000; Proteintech; 16,612-1-AP), BNIP3L (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, 12396s), COX4I1 (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, 4850), Flag (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, 14793s), FUNDC1 (1:1,000; Abcam, ab74834), GAPDH (1:3,000; KangChen, KC-5G4), GFP (1:1,000; MBL; 598), LC3B (1:1,000; Sigma-Aldrich, L7543), MYC (1:1,000; MBL; M192-3), PHB2/prohibitin 2 (1:1000; Proteintech; 12,295-1-AP); PRKN/PARK2 (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, 2132s), SQSTM1 (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, 5114), TOMM20 (1:1,000; Ambo Biotechnology, c16678), TP53 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, 2524 T) and ubiquitin (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 3936s). Secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP against either rabbit or mouse IgG (1:3,000; Cell Signaling Technology, 7071 and 7072) were applied. Digital images were quantified using densitometric measurement with Quantity-One software (Bio-Rad).

For immunoprecipitation, BNIP3L KO HeLa cells were transiently transfected. At 24 h post-transfection, the cells were suspended with the immunoprecipitation (IP) lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40 (Sangon Biotech, A100109), 0.25% sodium deoxycholate) with protease inhibitor cocktail and immunoprecipitated using EZview Red ANTI-Flag M2 Affinity Gel beads (Sigma-Aldrich, F2426). Then the immunoprecipitates were eluted with 100 μl 3× Flag peptide solution (Sigma-Aldrich, F4799). For MYC IP, the supernatant was incubated with 4 μl anti-MYC (MBL; M192-3) and mixed overnight with gentle rotation at 4°C. Then 50 μl protein A Sepharose (GE Healthcare, 17,078,001) was added for 4 h at 4°C.

For endogenous BNIP3 L IP, bnip3l-/- mice were injected with AAVs expressing GFP, GFP-Bnip3l, or GFP-Bnip3lG203A for at least two weeks and then were subjected to 6 h of pMCAO. The brain tissues were homogenized in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitor cocktail. The suspensions were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 20 min. Part of the supernatant (300 μg) was transferred to a new tube as input. In total, 20 μl Protein A Sepharose was added to the supernatant for the preclear process for 4 h and was subsequently discarded. The supernatant (1.5–3 μg) was incubated with 4–8 μl anti-BNIP3L (Cell Signaling Technology, 12396s) overnight at 4°C. Then 50 μl of Protein A Sepharose was added for 4 h at 4°C. Subsequently, the immunoprecipitates were washed with lysis buffer 3 times. The immunoprecipitates were then eluted by boiling for 5 min in 2 × Laemmli sample buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, S3401) and subjected to western blot analysis.

Statistical analysis

All data were collected and analyzed in a blind manner. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. The single comparisons were determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test. One-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) with Dunnett’s T3 post-hoc test applied for multiple comparisons. Sample sizes were based on our previous study and prior literature to achieve reliable measurements. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Paul Ney from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital for offering the bnip3l-/- mice and Professor Masaaki Komatsu of Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science for offering the Atg7fl/fl mice. We are grateful to the Core Facilities of Zhejiang University Institute of Neuroscience and Imaging Facilities.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81822044, 81773703 and 81872844) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2019XZZX004-17)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflicts of interest are disclosed.

Supplemental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- [1].Gallacher KI, Jani BD, Hanlon P, et al. Multimorbidity in stroke. Stroke. 2019;50(7):1919–1926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wang W, Jiang B, Sun H, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and mortality of stroke in china: results from a nationwide population-based survey of 480 687 adults. Circulation. 2017;135(8):759–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kislin M, Sword J, Fomitcheva IV, et al. Reversible disruption of neuronal mitochondria by ischemic and traumatic injury revealed by quantitative two-photon imaging in the neocortex of anesthetized mice. J Neurosci. 2017;37(2):333–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Anzell AR, Maizy R, Przyklenk K, et al. Mitochondrial quality control and disease: insights into ischemia-reperfusion injury. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(3):2547–2564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Um JH, Yun J.. Emerging role of mitophagy in human diseases and physiology. BMB Rep. 2017;50(6):299–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yuan Y, Zheng Y, Zhang X, et al. BNIP3L/NIX-mediated mitophagy protects against ischemic brain injury independent of PARK2. Autophagy. 2017;13(10):1754–1766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zhang X, Yan H, Yuan Y, et al. Cerebral ischemia-reperfusion-induced autophagy protects against neuronal injury by mitochondrial clearance. Autophagy. 2013;9(9):1321–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Yuan Y, Zhang X, Zheng Y, et al. Regulation of mitophagy in ischemic brain injury. Neurosci Bull. 2015;31(4):395–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Galluzzi L, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Blomgren K, et al. Autophagy in acute brain injury. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17(8):467–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tang YC, Tian H-X, Yi T, et al. The critical roles of mitophagy in cerebral ischemia. Protein Cell. 2016;7(10):699–713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sliter DA, Martinez J, Hao L, et al. Parkin and PINK1 mitigate STING-induced inflammation. Nature. 2018;561(7722):258–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yin W, Signore AP, Iwai M, et al. Rapidly increased neuronal mitochondrial biogenesis after hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Stroke. 2008;39(11):3057–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zuo W, Liu Z, Yan F, et al. Hyperglycemia abolished Drp-1-mediated mitophagy at the early stage of cerebral ischemia. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;843(p):34–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zheng Y, Zhang X, Wu X, et al. Somatic autophagy of axonal mitochondria in ischemic neurons. J Cell Biol. 2019;218(6):1891–1907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Novak I, Kirkin V, McEwan DG, et al. Nix is a selective autophagy receptor for mitochondrial clearance. EMBO Rep. 2010;11(1):45–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Schweers RL, Zhang J, Randall MS, et al. NIX is required for programmed mitochondrial clearance during reticulocyte maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(49):19500–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhang X, Yuan Y, Jiang L, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by tunicamycin and thapsigargin protects against transient ischemic brain injury: involvement of PARK2-dependent mitophagy. Autophagy. 2014;10(10):1801–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lampert MA, Orogo AM, Najor RH, et al. BNIP3L/NIX and FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy is required for mitochondrial network remodeling during cardiac progenitor cell differentiation. Autophagy. 2019;15(7):1182–1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ma J, Ni H, Rui Q, et al. Potential roles of NIX/BNIP3L pathway in rat traumatic brain injury. Cell Transplant. 2019;28(5):585-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zhang M, Shi R, Zhang Y, et al. Nix/BNIP3L-dependent mitophagy accounts for airway epithelial cell injury induced by cigarette smoke. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(8):14210–14220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lazarini M, Machado-Neto JA, Duarte ADSS, et al. BNIP3L in myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia: impact on disease outcome and cellular response to decitabine. Haematologica. 2016;101(11):e445–e448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yasuda M, Han J, Dionne C, et al. BNIP3alpha: a human homolog of mitochondrial proapoptotic protein BNIP3. Cancer Res. 1999;59(3):533–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yussman MG, Toyokawa T, Odley A, et al. Mitochondrial death protein Nix is induced in cardiac hypertrophy and triggers apoptotic cardiomyopathy. Nat Med. 2002;8(7):725–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Imazu T, Shimizu S, Tagami S, et al. Bcl-2/E1B 19 kDa-interacting protein 3-like protein (Bnip3L) interacts with bcl-2/Bcl-xL and induces apoptosis by altering mitochondrial membrane permeability. Oncogene. 1999;18(32):4523–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chen G, Cizeau J, Vande Velde C, et al. Nix and Nip3 form a subfamily of pro-apoptotic mitochondrial proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(1):7–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rodrigo R, Mendis N, Ibrahim M, et al. Knockdown of BNIP3L or SQSTM1 alters cellular response to mitochondria target drugs. Autophagy. 2019;15(5):900–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Esteban-Martinez L, Sierra‐Filardi E, McGreal RS, et al. Programmed mitophagy is essential for the glycolytic switch during cell differentiation. Embo J. 2017;36(12):1688–1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Klionsky DJ, Abdelmohsen K, Abe A, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition). Autophagy. 2016;12(1):1–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Komatsu M, Waguri S, Ueno T, et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2005;169(3):425–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].McWilliams TG, Prescott AR, Allen GFG, et al. mito-QC illuminates mitophagy and mitochondrial architecture in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2016;214(3):333–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Shen Z, Zheng Y, Wu J, et al. PARK2-dependent mitophagy induced by acidic postconditioning protects against focal cerebral ischemia and extends the reperfusion window. Autophagy. 2017;13(3):473–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Liu L, Feng D, Chen G, et al. Mitochondrial outer-membrane protein FUNDC1 mediates hypoxia-induced mitophagy in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(2):177–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wei Y, Chiang W-C, Sumpter R, et al. Prohibitin 2 is an inner mitochondrial membrane mitophagy receptor. Cell. 2017;168(1–2):224–238 e10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Otsu K, Murakawa T, Yamaguchi O. BCL2L13 is a mammalian homolog of the yeast mitophagy receptor Atg32. Autophagy. 2015;11(10):1932–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kuramori C, Azuma M, Kume K, et al. Capsaicin binds to prohibitin 2 and displaces it from the mitochondria to the nucleus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;379(2):519–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Jiang D, Sun X, Wang S, et al. Upregulation of miR-874-3p decreases cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by directly targeting BMF and BCL2L13. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;117:108941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wu W, Tian W, Hu Z, et al. ULK1 translocates to mitochondria and phosphorylates FUNDC1 to regulate mitophagy. EMBO Rep. 2014;15(5):566–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Nakamura Y, Kitamura N, Shinogi D, et al. BNIP3 and NIX mediate Mieap-induced accumulation of lysosomal proteins within mitochondria. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sulistijo ES, MacKenzie KR. Sequence dependence of BNIP3 transmembrane domain dimerization implicates side-chain hydrogen bonding and a tandem GxxxG motif in specific helix-helix interactions. J Mol Biol. 2006;364(5):974–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ding WX, Ni HM, Chen X, et al. A coordinated action of Bax, PUMA, and p53 promotes MG132-induced mitochondria activation and apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(3):1062–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gandolfi S, Laubach JP, Hideshima T, et al. The proteasome and proteasome inhibitors in multiple myeloma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2017;36(4):561–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Vij R, Wang M, Kaufman JL, et al. An open-label, single-arm, phase 2 (PX-171-004) study of single-agent carfilzomib in bortezomib-naive patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;119(24):5661–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lin Y-H, Dong J, Tang Y, et al. Opening a new time window for treatment of stroke by targeting HDAC2. J Neurosci. 2017;37(28):6712–6728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zhu M-Y, Zhang D-L, Zhou C, et al. Mild acidosis protects neurons during oxygen-glucose deprivation by reducing loss of mitochondrial respiration. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2019;10(5):2489–2497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Solenski NJ, diPierro CG, Trimmer PA, et al. Ultrastructural changes of neuronal mitochondria after transient and permanent cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2002;33(3):816–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Xiang G, Yang L, Long Q, et al. BNIP3L-dependent mitophagy accounts for mitochondrial clearance during 3 factors-induced somatic cell reprogramming. Autophagy. 2017;13(9):1543–1555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].O’Sullivan TE, Johnson L, Kang H, et al. BNIP3- and BNIP3L-mediated mitophagy promotes the generation of natural killer cell memory. Immunity. 2015;43(2):331–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Chen G, Ray R, Dubik D, et al. The E1B 19K/Bcl-2-binding protein Nip3 is a dimeric mitochondrial protein that activates apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1997;186(12):1975–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hanna RA, Quinsay MN, Orogo AM, et al. Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) interacts with Bnip3 protein to selectively remove endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria via autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(23):19094–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Lee S, Zhang C, Liu X. Role of glucose metabolism and ATP in maintaining PINK1 levels during Parkin-mediated mitochondrial damage responses. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(2):904–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Allen GF, Toth R, James J, et al. Loss of iron triggers PINK1/Parkin-independent mitophagy. EMBO Rep. 2013;14(12):1127–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kanki T, Klionsky DJ. Mitophagy in yeast occurs through a selective mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(47):32386–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Marinkovic M, Sprung M, Novak I. Dimerization of mitophagy receptor BNIP3L/NIX is essential for recruitment of autophagic machinery. Autophagy. 2020;1–12. DOI: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1755120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Frazier DP, Wilson A, Graham RM, et al. Acidosis regulates the stability, hydrophobicity, and activity of the BH3-only protein Bnip3. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8(9–10):1625–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bingol B, Tea JS, Phu L, et al. The mitochondrial deubiquitinase USP30 opposes parkin-mediated mitophagy. Nature. 2014;510(7505):370–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Caldeira MV, Curcio M, Leal G, et al. Excitotoxic stimulation downregulates the ubiquitin-proteasome system through activation of NMDA receptors in cultured hippocampal neurons. Biochim. Biophys Acta-Mol Basis Dis. 2013;1832(1):263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Herndon TM, Deisseroth A, Kaminskas E, et al. U.S. Food and drug administration approval: carfilzomib for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(17):4559–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Karademir B, Liu L, Feng D, et al. Proteomic approach for understanding milder neurotoxicity of carfilzomib against bortezomib. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):16318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zhang L, Zhang ZG, Buller B, et al. Combination treatment with VELCADE and low-dose tissue plasminogen activator provides potent neuroprotection in aged rats after embolic focal ischemia. Stroke. 2010;41(5):1001–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Kolev K, Skopál J, Simon L, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in post-hypoxic human brain capillary endothelial cells: H2O2 as a trigger and NF-kappaB as a signal transducer. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90(3):528–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Jeong EI, Chung HW, Lee WJ, et al. E2-25K SUMOylation inhibits proteasome for cell death during cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(12):e2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Qiu JH, Asai A, Chi S, et al. Proteasome inhibitors induce cytochrome c-caspase-3-like protease-mediated apoptosis in cultured cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20(1):259–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Herrero-Mendez A, Almeida A, Fernandez E, et al. The bioenergetic and antioxidant status of neurons is controlled by continuous degradation of a key glycolytic enzyme by APC/C-Cdh1. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(6):747–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Baek SH, Noh AR, Kim K-A, et al. Modulation of mitochondrial function and autophagy mediates carnosine neuroprotection against ischemic brain damage. Stroke. 2014;45(8):2438–2443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc. 2013;8(11):2281–2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.