Archaeogenetic time transect in Europe unravels genetic and social changes before and after the arrival of “steppe” ancestry.

Abstract

Europe’s prehistory oversaw dynamic and complex interactions of diverse societies, hitherto unexplored at detailed regional scales. Studying 271 human genomes dated ~4900 to 1600 BCE from the European heartland, Bohemia, we reveal unprecedented genetic changes and social processes. Major migrations preceded the arrival of “steppe” ancestry, and at ~2800 BCE, three genetically and culturally differentiated groups coexisted. Corded Ware appeared by 2900 BCE, were initially genetically diverse, did not derive all steppe ancestry from known Yamnaya, and assimilated females of diverse backgrounds. Both Corded Ware and Bell Beaker groups underwent dynamic changes, involving sharp reductions and complete replacements of Y-chromosomal diversity at ~2600 and ~2400 BCE, respectively, the latter accompanied by increased Neolithic-like ancestry. The Bronze Age saw new social organization emerge amid a ≥40% population turnover.

INTRODUCTION

Archaeogenetics has revealed two major population turnovers in Europe within the past 10,000 years (1–5). The first, beginning in the seventh millennium BCE, was associated with expanding Neolithic farming communities from Anatolia (6, 7). European Early Neolithic farmers were initially genetically distinct from preceding hunter-gatherers (HG) and almost indistinguishable from Anatolian farmers (8–10), however incorporated HG ancestry into their gene pools over ensuing millennia (3, 11–13).

The second major turnover occurred in the early third millennium BCE with individuals of the Corded Ware (CW) culture (3, 4, 8). Of note, in what follows, we use the co-occurrence of human skeletal remains and markers of archaeological cultures (e.g., grave goods and body orientation) to denote an association between individuals and an archaeological culture (e.g., “CW individuals”), although this may not reflect a unified social entity. The CW represents a major cultural shift in central, northern, and northeastern Europe, bringing changes in economy, ideology, and mortuary practices (14–22). CW individuals were shown to be genetically distinct from culturally pre-CW people, having ~75% of their ancestry similar to Yamnaya individuals from the Pontic-Caspian steppe (3, 4, 23–27). This Yamnaya-like “steppe” ancestry then spread rapidly throughout Europe, reaching Britain, Ireland, the Iberian Peninsula, the Balearic Islands, Sardinia, and Sicily before the end of the third millennium BCE (5, 28–32).

Despite the importance of the third millennium BCE, our genetic understanding is mainly built upon studies with pan-European sampling strategies, with little emphasis on regional, high-resolution temporal transects (3–5, 8). Consequently, many temporal and geographic sampling gaps remain, resulting in limited knowledge about the processes at the level of the societies and communities and how cultural groups interacted, influenced, and gave rise to one another. In addition, the use of small sample sizes to represent supra-regional archaeological phenomena, as well as the resulting oversimplified culture-historical interpretations, has drawn criticisms from archaeologists (21, 33–40).

Unresolved questions concern the genetic and geographic origins of CW and Bell Beaker (BB) individuals, their relationship to one another and to Yamnaya individuals, as well as the origin of Early Bronze Age (EBA) Únětice individuals. Although it has been proposed that CW formed from a male-biased westward migration of genetically Yamnaya-like people (23, 41–44), no overlap in Y-chromosomal lineages (with the exception of a few nondiagnostic I2) has been found between the predominantly R1a-carrying CW and mainly R1b-Z2103–carrying Yamnaya males. Steppe ancestry is also present in BB individuals (5); however, they predominantly carry R1b-P312, a Y-lineage not yet found among CW or Yamnaya males. Therefore, despite their sharing of steppe ancestry (3, 4) and substantial chronological overlap (45), it is currently not possible to directly link Yamnaya, CW, and BB groups as paternal genealogical sources for one another, particularly noteworthy in light of steppe ancestry’s suggested male-driven spread (23, 41–43) and the proposed patrilocal/patriarchal social kinship systems of these three societies (46–48).

Crucial to understanding the cultural, social, and genetic transitions in third millennium BCE Europe are densely settled regions that attest to the (co)existence of societies attributed to pre-CW [Baden and Globular Amphora (GAC)], CW, BB, and EBA Únětice. Currently, no such region has been systematically studied from the archaeogenetic perspective. Situated in the heart of Europe and tightly nestled around the important Elbe river, the fertile lowlands of Bohemia, the western part of today’s Czech Republic, witnessed many major supra-regional archaeological phenomena (table S1, Fig. 1, fig. S1, and the Supplementary Materials). Dense agrarian settlement of Bohemia began after ~5400 BCE (49, 50) with the arrival of early Neolithic farmers (Linearbandkeramik-LBK, later Stichbandkeramik-STK, and Lengyel). They were succeeded by manifold societies of the Eneolithic (~4400 to 2200 BCE), associated with more than a dozen archaeological cultural groups including Jordanów, Michelsberg, Funnelbeaker, Baden, Řivnáč, GAC, Early and Late CW, and BB (table S1) (50). The Eneolithic witnessed important innovations (metallurgy, the wheel, wagon and plough, fortified hillforts, and burial mounds) (51–53) and was succeeded by the globalized EBA Únětice culture, geographically centered around Bohemia.

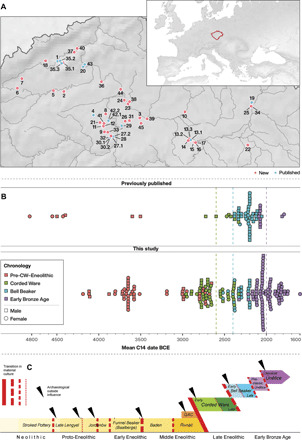

Fig. 1. Temporal and geographic distribution of studied Neolithic, Eneolithic, and EBA individuals from Bohemia.

(A) Map of Bohemia showing the locations of sampled sites (red, new; blue, previously published; table S2 and figs. S1 to S5). (B) Mean age of newly reported (n = 206) and published (n = 65) individuals from Bohemia. (C) Local chronology of archaeological cultures and time periods. Black triangles indicate external influences visible in the material culture. Red lines indicate qualitative degree of change in material culture.

In addition to material and technological developments, ideological changes, as manifested through mortuary behavior, are also evident (54). Although relatively common during the Funnelbeaker period (~3800 to 3400 BCE, n = ~100 known graves in Bohemia) (55), regular graves almost disappear from the succeeding Baden, Řivnáč, and GAC periods (Middle Eneolithic, ~3500 to 2800 BCE, n = ~20 in Bohemia) (56). Single graves, but now with strict gender differentiation in body position and grave goods, reappeared in abundance with CW from ~2900 BCE (n = ~1500 in Bohemia) (50, 57) and continued with BB (n = ~600 in Bohemia) from ~2500 BCE (58), who developed and maintained important differences from the preceding CW. The EBA Únětice culture (59, 60) continued with single graves (n = ~4000 to 5000 in Bohemia), but now again without gender differentiation in body position.

To better understand these transitions, we analyzed a high-resolution archaeogenetic time transect of 271 (206 newly reported and 65 previously published) individuals (Fig. 1, fig. S1, tables S2 to S4, and the Supplementary Materials) from the northern part of Bohemia. Through dense genetic sampling from geographically and temporally overlapping archaeological cultures, we aim to (i) address whether cultural changes in the Eneolithic and EBA of central Europe were driven by an influx of nonlocals, (ii) characterize the central European genetic diversity immediately prior the appearance of CW, (iii) date when individuals with Yamnaya-like steppe ancestry first appeared in central Europe and understand their genetic origin and social structure, (iv) characterize the nature and extent of biological exchange between the “locals” and “migrants” after the appearance of CW, and (v) identify social transformations linked to genetic and archaeological changes.

RESULTS

General sample overview

We screened 261 prehistoric individuals (table S3) from 37 sites (table S2) for ancient human DNA preservation, of which 219 individuals were enriched for 1,233,013 ancestry informative sites in the human genome (“1240k capture panel”) (8). After enrichment, individuals with fewer than 30,000 sites covered (on 1240k) or signs of contamination were removed (n = 13), resulting in a dataset of 206 newly reported individuals. We combined our dataset with 65 previously published individuals (5, 61, 62) from Bohemia (with >30,000 covered sites on 1240k; table S4) and wider (table S5), thereby extending the total number of published Bohemian Neolithic and pre-CW Eneolithic individuals from 7 to 58 (fig. S2), CW individuals from 7 to 54 (fig. S3), BB individuals from 40 to 64 (fig. S4), and EBA individuals from 11 to 95 (fig. S5). Crucially, we substantially expand the sample size of individuals around the time of CW formation (~3200 to 2600 BCE, from n = 1 to n = 50; Fig. 1B), i.e., the last pre-CW (Baden, Řivnáč, and GAC, from n = 0 to n = 18) and the early CW (from n = 1 to n = 32) individuals, allowing us to directly study the origin of CW in central Europe, the nature of their migration, and social interactions with coexisting pre-CW people. First-degree relatives were excluded from allele frequency–based analyses [f statistics, qpWave, qpAdm, Distribution of Ancestry Tracts of Evolutionary Signals (DATES), and Y chromosome analyses; table S4 and see Materials and Methods]. We also report 140 new radiocarbon dates to aid in finer temporal resolution, allowing us to study the genetic changes between early and late phases of important third millennium BCE cultural groups (e.g., CW, BB, and Únětice; tables S4 and S6).

Bohemia before Corded Ware (pre-CW, before ~2800 BCE)

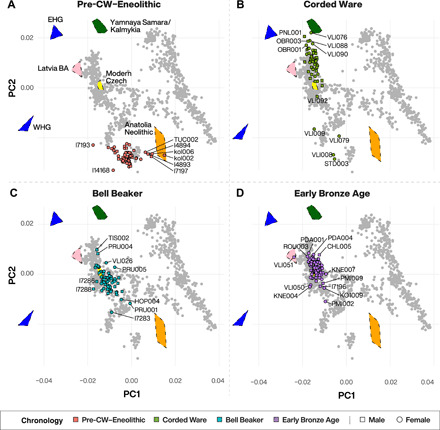

We first assessed the genome-wide data by projecting the ancient individuals from Bohemia onto the first two axes of a principal components analysis (PCA) constructed from 1141 modern-day West Eurasian individuals (table S7). In the resulting PCA plot (Fig. 2A), all (n = 58) pre-CW individuals from Bohemia plot between Anatolia_Neolithic and Western HG (WHG), in close proximity to published culturally pre-CW individuals from central Europe (3, 8, 11, 13, 25). This suggests an absence of steppe ancestry, which we formally confirmed using qpAdm modeling (table S8), revealing that pre-CW individuals from Bohemia can be largely modeled as two-way mixtures of Anatolia_Neolithic and WHG (Fig. 3A, tables S8 and S9, and fig. S6). The percentage of HG ancestry is positively correlated with time (Spearman’s rank correlation r = 0.39, P < 0.004), showing that the previously reported trend of increasing HG ancestry during the Neolithic also took place in Bohemia (3, 11). We found this HG ancestry increase to be best modeled as a two-stage linear process (Fig. 3A, table S8, and the Supplementary Materials), with an increase in HG ancestry during the fifth millennium BCE, followed by stasis (nonsignificant slope) thereafter (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Materials).

Fig. 2. PCA of published and newly reported ancient individuals from Bohemia (n = 271).

Data are displayed in four major time periods: (A) Pre-CW–Eneolithic, (B) CW, (C) BB, and (D) EBA. Modern-day West Eurasian individuals upon which principal components were calculated (n = 1141; table S7) are grayed out in the background with modern-day Czech and relevant ancients (projected) plotted as colored polygons for reference [labeled in (A), WHG, EHG, Latvia Bronze Age (BA), Yamnaya Samara/Kalmykia, and Anatolia Neolithic]. Individuals mentioned in the main text are labeled.

Fig. 3. WHG ancestry in pre-CW Bohemia.

(A) The proportion of WHG ancestry through time in pre-CW individuals from Bohemia modeled as a two-stage linear process (table S8). The gray area indicates 95% confidence interval. (B) Left: Proportion of ancestry ascribable to Anatolia_Neolithic, Loschbour, and Körös_HG in pre-CW cultural groups from Bohemia in chronological order from bottom to top (sample size of each cultural group in brackets and P value of three-way qpAdm model indicated within orange bars; table S10). Right: Inferred dates (2 SE; table S11) of HG admixture (gray interval) relative to culture’s chronology (black interval). (C) Zoomed-in PCA showing (with the exception of TUC003) segregation between Bohemian GAC and Řivnáč individuals along with position of early CW females without steppe ancestry (green circles). Black dots represent previously published GAC individuals from Poland and Ukraine.

To gain insight into the process(es) by which HG ancestry was incorporated into the gene pool of pre-CW individuals from Bohemia, we used qpAdm to model each pre-CW cultural group as a three-way mixture of Anatolia_Neolithic, Loschbour, and Körös_HG as well as DATES to estimate the introgression date of incorporated HG ancestry (Fig. 3B and tables S10 and S11). Under a scenario of population continuity with sequential incorporation of HG ancestry, the mean date of introgression, as indicated by the gray intervals in Fig. 3B (right), for succeeding cultures is expected to become more recent through time. Conversely, under population continuity without incorporation of further HG ancestry, the admixture date should be similar for successive cultural groups who have similar HG proportions.

Our results indicate two cultural transitions for which either of these expectations is not met. First, although Bohemian Jordanów and Funnelbeaker have similar amounts of WHG ancestry [f4(Mbuti.DG, WHG; Jordanów, Funnelbeaker) ~0; z score, 0.96], the estimated date of WHG introgression for Funnelbeaker is significantly earlier (5079 to 4748 BCE) than for Jordanów (4636 to 4310 BCE) (Fig. 3B and table S11), consistent with Bohemian Funnelbeaker individuals being derived from a different population (whose HG ancestry was incorporated further back in time), which superseded the Jordanów population in Bohemia. This transition between Jordanów and Funnelbeaker is corroborated by three additional observations. First, an f4 statistic of the form f4(Mbuti.DG, Bohemia-Funnelbeaker; Bohemia-Jordanów, Germany-Funnelbeaker) is positive (z score, 3.14), revealing significantly greater genetic affinity of Bohemian Funnelbeaker to Funnelbeaker (Baalberge and Salzmünde) individuals from Saxony-Anhalt than to the preceding local Jordanów individuals. Conversely, f4(Mbuti.DG, Bohemia-Jordanów; Germany-Funnelbeaker, Bohemia-Funnelbeaker) is consistent with 0 (z score, 1.03), suggesting phylogenetic cladality between Bohemian and German Funnelbeaker with respect to Bohemia-Jordanów individuals. Second, Bohemia-Jordanów individuals can be modeled as a two-way mixture of Anatolia_Neolithic and Körös_HG but not Anatolia_Neolithic and Loschbour, while the opposite is true for Bohemia-Funnelbeaker (table S12). This suggests different affinities, in addition to the different introgression dates, of the HG ancestries in Bohemian Jordanów and Funnelbeaker cultural groups. Third, qpWave does not support cladality between Bohemian Jordanów and Funnelbeaker (P = 0.00679), while cladality between Bohemian and German Funnelbeaker cannot be rejected (P = 0.88; table S13). Together, these results indicate a largely (significantly more than 50%) nonlocal genetic origin of Bohemian Funnelbeaker individuals.

The second such case can be seen in the Řivnáč to GAC cultural transition. GAC individuals carry the most HG ancestry among pre-CW cultural groups from Bohemia (25.7%, ±1.4), significantly more than Řivnáč individuals [f4(Mbuti.DG, WHG; Řivnáč, GAC) >> 0; z score, 4.46]. However, the estimated date of HG admixture in GAC is not later than in Řivnáč individuals (Fig. 3B and table S11), suggesting that GAC individuals do not descend from a recent mixture of Řivnáč and an HG source but instead constituted a recent, nonlocal incursion in Bohemia from a region that received more HG gene flow [e.g., Poland (13, 63)], in accordance with interpretations of archaeological evidence (56).

A distinct genetic origin for Řivnáč and GAC individuals is further supported by PCA and qpAdm modeling. From PCA, we find that with the exception of TUC003, Řivnáč and GAC individuals form distinct clouds (Fig. 3C). This is confirmed by qpAdm modeling where GAC individuals can be modeled as a mixture of Anatolia_Neolithic and Loschbour but not Anatolia_Neolithic and Körös_HG, while the opposite is true for Řivnáč individuals (table S14). Consequently, Řivnáč and GAC individuals are distinguishable based on the amount and source of HG ancestry, suggesting that Bohemia was inhabited by genetically differentiated groups of Řivnáč and GAC individuals at the time of CW appearance. The Řivnáč outlier (TUC003) also raises the interesting possibility of an individual born into a GAC but buried in a Řivnáč cultural context.

Among the 16 Řivnáč and GAC individuals who are contemporaneous with or postdate the appearance of CW in Bohemia (Fig. 1B), we find no detectable traces of steppe ancestry (Fig. 2A and table S8), suggesting that biological exchange from CW/Yamnaya into culturally pre-CW people (e.g., Řivnáč and GAC) was low, possibly nonexistent. Steppe ancestry coappears with CW individuals in early third millennium BCE Bohemia.

Corded Ware

We report genomic data from the earliest CW individuals to date, including STD003 (northwestern Bohemia, 3010 to 2889 calibrated (cal) BCE), VLI076 (central Bohemia, 3018 to 2901 cal BCE), OBR003 (central Bohemia, 2911 to 2875 cal BCE), and PNL001 (eastern Bohemia, 2914 to 2879 cal BCE), showing that CW was widespread across Bohemia by 2900 BCE. The early radiocarbon dates are also supported by these individuals’ genetic profiles, who occupy the most extreme positions on PC2 (Fig. 2B), as expected under a scenario of the earliest CW being migrants from the east who mixed with locals, resulting in intermediate PC2 positions in later generations.

To explore the formation of the Bohemian CW gene pool, we grouped CW individuals with steppe ancestry and mean age > 2600 BCE (n = 27) into a Bohemia_CW_Early group and the rest (n = 21) into Bohemia_CW_Late (table S4). We found poor statistical support (P < 0.005) for modeling Bohemia_CW_Early as a two-way mixture of any known Yamnaya source and any local Bohemian or nonlocal pre-CW source from Poland, Ukraine, Hungary, or Germany (table S15). When using distal sources as proxies for the Neolithic ancestry (Anatolia_Neolithic and a range of HG sources), we found no strong support (P < 0.05) for all but one of the three-way distal models (table S16). However, this one statistically supported model results in a previously unobserved ratio of Neolithic ancestry in Europe (i.e., a Neolithic population of ~1:1 ratio of Anatolia_Neolithic:Sweden_Motala_HG). In addition, when modeling early CW individually as “standard” three-way mixtures of Anatolia_Neolithic, WHG, and Yamnaya_Samara (3), we find that in 37% (10 of 27) of cases, the model lacks strong support (P < 0.05 or infeasible; fig. S6 and table S9).

To explore why two-way proximal models between any Yamnaya and a European Neolithic source are insufficient in explaining Bohemia_CW_Early genetic diversity, we tried adding a third source to obtain better model fits. We find that when either one of Latvia_MN, Ukraine_Neolithic, or PittedWare is added as a source, almost all (280 of 285) model fits (P values) improve and most of them by several orders of magnitude (table S17). While all (n = 95) two-way proximal models lack strong support (P < 0.05; table S17), the addition of either Latvia_MN (57 of 95 supported models), Ukraine_Neolithic (53 of 95 supported models), or PittedWare (32 of 95 supported models) to the sources drastically increases the number of supported models (table S17). These results show the presence of excess Latvia_MN/Ukraine_Neolithic/PittedWare-like ancestry in Bohemia_CW_Early relative to all known Yamnaya and central European Neolithic groups. Our models suggest that this ancestry accounts for ~5 to 15% of the Bohemia_CW_Early gene pool (table S17). Increases in model fits with either of these third sources are also observed when modeling Bohemia_CW_Late and Germany_Corded_Ware, suggesting this ancestry to be present also in later central European CW (tables S18 and S19) and is consistent with allele sharing f4 statistics, which show that CW groups share more alleles with ancient northeast European groups than do Yamnaya (tables S20 and S21).

We provide the first genomic data from CW individuals without steppe ancestry, thereby elucidating the social processes of interaction between CW and pre-CW people. Observing only females (four of four) among early CW individuals without steppe ancestry (Figs. 2B and 3C) suggests that the process of assimilating pre-CW people into early CW society was female-biased. Two of these females (STD003 and VLI008) plot in close PCA space to GAC individuals from Bohemia and Poland (Fig. 3C). When grouped together, we find that STD003+VLI008 share more genetic affinity with Bohemian GAC than with Bohemian Řivnáč [f4(Mbuti.DG, STD003+VLI008; Bohemia-GAC, Bohemia-Řivnáč) < 0; z score, −2.32]. These two females are not genetically closer to Bohemian compared to Polish GAC individuals [f4(Mbuti.DG, STD003+VLI008; Bohemia-GAC, Poland-GAC) ~ 0; z = 0.5], meaning that a nonlocal, (north)eastern origin (e.g., Poland) cannot be ruled out. In addition, VLI009 and VLI079 fall outside of the sampled Bohemian Middle Eneolithic (Baden, Řivnáč, and GAC) genetic variation in PCA, carrying significantly more HG ancestry (Fig. 3C and table S22), suggesting that a large proportion (50%, or higher when including STD003/VLI008) of the genetically pre-CW females of the early CW society originated from outside Bohemia.

We find that Bohemia_CW_Late carries significantly more pre-CW–Eneolithic–like ancestry compared to Bohemia_CW_Early (table S23); however, this signal is lost when early CW females without steppe ancestry are included (table S24). This additional pre-CW–Eneolithic–like ancestry in Bohemia_CW_Late (relative to Bohemia_CW_Early) is poorly modeled as coming from local sources (table S25), suggesting nonlocal genetic influences on the Bohemian CW gene pool through time. This is consistent with the genetically pre-CW females originating from outside of Bohemia and is supported by the finding that Bohemia_CW_Early (including females without steppe ancestry) and Bohemia_CW_Late are not cladal in qpWave analysis (table S26), despite having similar amounts of pre-CW–Eneolithic–like ancestry.

In addition to autosomal genetic changes through time, we observe a sharp reduction in Y-chromosomal diversity going from five different lineages in early CW to a dominant (single) lineage in late CW (Fig. 4A). We used forward simulations to explore the demographic scenarios that could account for the observed reduction in Y-chromosomal diversity. Performing 1 million simulations of a population with a starting frequency of R1a-M417(xZ645) centered around the observed starting frequency in Bohemia_CW_Early (3 of 11, 0.27), we assessed the plausibility of this lineage reaching the observed frequency in Bohemia_CW_Late (10 of 11, 0.91) in the time frame of 500 years under a model of a closed population and random mating (Materials and Methods). We reject the “neutral” hypothesis, i.e., that this change in frequency occurred by chance, given a wide range of plausible population sizes. Instead, our results suggest that R1a-M417(xZ645) was subject to a nonrandom increase in frequency, resulting in these males having 15.79% (4.12 to 44.42%) more surviving offspring per generation relative to males of other Y-haplogroups. We also find that this change in Y chromosome frequency is extreme compared to the changes in allele frequencies at fully covered autosomal 1240k sites (P < 0.0003) within the same males, suggesting a process that disproportionately affected Y-chromosomal compared to autosomal genetic diversity, ruling out a population bottleneck as the likely cause. Our results suggest that the Y-lineage diversity in early CW males was supplanted by a nonrandom process [selection, social structure, or influx of nonlocal R1a-M417(xZ645) lineages] that drove the collapse in Y-chromosomal diversity. A simultaneous decline of Y-chromosomal diversity dating to the Neolithic has been observed across most extant Y-haplogroups (64), possibly due to increased conflict between male-mediated patrilines (65). We view that changes in social structure (e.g., an isolated mating network with strictly exclusive social norms) could be an alternative cause but would be difficult to distinguish in the underlying model parameters.

Fig. 4. Temporal Y chromosome and autosomal PC2 variation in Bohemia.

(A) Temporal distribution of Y chromosome haplogroups by culture. Schematic of phylogenetic relationships between Y chromosome lineages is shown along y axis. Dashed vertical lines demarcate respective (colored) cultural group into early and late phases. (B) Temporal variation in PC2 showing the genetic variation of males and females within each cultural group.

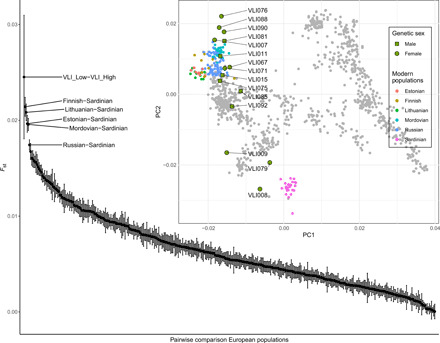

The greatest genetic differentiation within early CW individuals can be found at Vliněves. The fst value between the three highest and three lowest early CW individuals on PC2 from Vliněves is greater than pairwise comparisons of all modern-day European populations (Fig. 5 and table S27).

Fig. 5. Genetic distances of Early CW individuals from Vliněves.

Pairwise Fst between the three highest (VLI076, VLI088, and VLI090; VLI_High) and three lowest (VLI008, VLI079, and VLI009; VLI_Low) early CW on PC2 from Vliněves in the context of modern European pairwise Fst (2 SE plotted; table S27). Inset: PCA of 1141 modern West Eurasian individuals (gray points) on which early CW individuals from Vliněves (green symbols with black outline) were projected (see also Fig. 2B). The highly differentiated pairs of modern European populations labeled in the main figure are colored in the inset PCA.

Bell Beaker

The earliest BB individuals occupy a similar position in PCA as CW individuals (Fig. 4B and fig. S7), suggesting a degree of genetic continuity. To explore the genetic origin of early BB individuals (Bohemia_BB_Early; mean date, >2400 BCE; n = 3), we modeled them as a two-way mixture between preceding and contemporaneous cultural groups. We found support for a local origin, although nonlocal alternatives cannot be ruled out (table S28). However, our Bohemia_BB_Early group consists of only three (female) individuals and is therefore likely limited in representativeness and resolution to discern source populations.

We find that late BB individuals (Bohemia_BB_Late; mean date, ≤2400 BCE; n = 56) carry significantly more Middle Eneolithic–like ancestry compared to Bohemia_BB_Early (table S29). To explore this genetic shift, we modeled the ancestry of Bohemia_BB_Late as a two-way mixture of Bohemia_BB_Early and local Middle Eneolithic sources (table S30), finding support for an additional ~20% local Middle Eneolithic–like ancestry in late compared to early BB.

We observe a closer phylogenetic relationship between the Y chromosome lineages found in early CW and BB than in either late CW or Yamnaya and BB. R1b-L151 is the most common Y-lineage among early CW males (6 of 11, 55%) and one branch ancestral to R1b-P312 (Fig. 4A), the dominant Y-lineage in BB (5). Although it is not possible to determine whether the P312 mutation(s) occurred in one of the early CW R1b-L151 males from Bohemia, we note that most Bohemian BB males are further derived at R1b-L2/S116 (R1b1a1a2b1), in contrast to BB males from England, several of whom are derived at R1b-L21(R1b1a1a2c1), showing that English and Bohemian BB males cannot be descendants of one another, but rather diversified in parallel. A scenario of R1b-P312 originating somewhere between Bohemia and England, possibly in the vicinity of the Rhine (66, 67), followed by an expansion northwest and east is compatible with our current understanding of the phylogeography of ancient R1b-L151–derived lineages.

EBA—Únětice culture

The transition to the EBA in Bohemia is associated with a positive shift in the coordinates of PC2, relative to preceding late BBs (Fig. 4B, fig. S7, and table S31). Admixture f3 statistics are most negative when EHG (Eastern HG) or WSHG (West Siberian HG) are used as a second source in addition to the geographically and temporally proximal Bohemia_BB_Late (table S32), suggesting a northeastern contribution to Bohemia_Únětice_preClassical. To find a suitable proxy for a potential additional source population, we modeled Bohemia_Únětice_preClassical as a two-way mixture of local Bohemia_BB_Late and various sources more positive on PC2 (table S33). We reject mixture models involving Bohemia_BB_Late and Yamnaya (Samara, P = 5.3 × 10−10; Kalmykia, P = 5.8 × 10−10; Ukraine, P = 7.3 × 10−12; and Caucasus, P = 3.2 × 10−15) or Bohemia_BB_Late and CW (early, P = 1.1 × 10−4; late, P = 5.4 × 10−6). We fail to reject a two-way mixture model of 63.5% Bohemia_BB_Early and 36.5% Bohemia_BB_Late (P = 0.29), suggesting a large (63.5%) contribution from an early BB lineage, which was largely unsampled during the late BB phase (2400 to 2200 BCE), but represents a potential new lineage at the dawn of the Bronze Age. The Y-chromosomal data suggest an even larger turnover. A decrease of Y-lineage R1b-P312 from 100% (in late BB) to 20% (in preclassical Únětice) implies a minimum 80% influx of new Y-lineages at the onset of the EBA.

However, aware of the limited resolution of Bohemia_BB_Early (small sample size, low resolution, and large SEs), we explored alternative models for preclassical Únětice individuals. All model fits improve when Latvia_BA is included in the sources, resulting in two additional supported models (table S33). A three-way mixture of Bohemia_BB_Late, Bohemia_CW_Early, and Latvia_BA (P value of 0.086) not only supports a more conservative estimate of 47.7% population replacement but also accounts for the Y-chromosomal diversity found in preclassical Únětice, with R1b-P312 from Bohemia_BB_Late, R1b-U106 and I2 from Bohemia_CW_Early, and R1a-Z645 from Latvia_BA (Fig. 4A).

Although the geographic origin of this new ancestry cannot be precisely located, three observations offer clues. First, the Latvia_BA ancestry that improves all model fits (table S33) suggests an ultimate northeastern origin. Second, Y-haplogroup R1a-Z645 appears in Bohemia (and wider central Europe) for the first time at the beginning of the EBA, a lineage previously fixed in Baltic and common in Scandinavian CW males (23, 24), supporting a north/northeastern genetic contribution. Third, an Únětice genetic outlier (VLI051, male, Y-haplogroup R1a-Z645; table S34) resembles individuals from Bronze Age Latvia (Fig. 2D) (68), providing direct evidence for migrants from the northeast.

We also detect a genetic shift in the transition from preclassical to classical Únětice, reflected in the decrease in PC2 coordinates for Únětice individuals dated after ~2000 BCE (Fig. 4B and fig. S7) and confirmed using qpWave (table S35) and f4 statistics (table S36). Bohemia_Únětice_Classical can be modeled as a mixture of Bohemia_Únětice_preClassical and a local Eneolithic source (table S37). In contrast to the genetic shift between late BB and preclassical Únětice, the Y-lineage diversity remains similar throughout both Únětice phases, suggesting assimilation and subtler social changes.

DISCUSSION

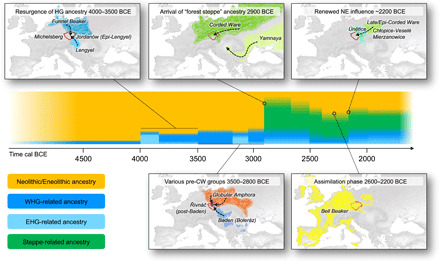

The high-resolution genetic time transect in Bohemia, allowing early and late phases of cultural groups to be divided and studied separately (e.g., CW, BB, and Únětice), elucidates several major processes before and after the arrival of steppe ancestry (Fig. 6). Our dense sampling allows detection of novel, important, and perhaps “unexpected” changes within cultural groups (e.g., CW and BB), if they are seen through a strict cultural-historical lens. Previous studies have largely been interpreted as revealing major migrations at the beginning and end of the Neolithic (i.e., periods where the incoming groups were genetically very distinct); however, our results reveal additional large genetic turnovers. By sampling consecutive and partially contemporaneous cultural groups, we show that the spread of Funnelbeaker and GAC (69, 70), as well as the origin of Únětice, involved large genetic shifts over short time periods, likely explained by migrations.

Fig. 6. Schematic summary of the major processes that shaped the genetic and cultural diversity of Bohemia (red outline) over time.

Arrows on maps indicate a general direction of influences rather than discrete routes of migration.

We show that early CW were genetically exceptionally diverse, some resembling GAC and Yamnaya, with a few also falling outside of previously sampled central European Neolithic genetic diversity. Such a notably diverse signal is likely the result of the agglomeration of people from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds into an archaeologically similar but polyethnic or plural society. Important factors in ethnic identity include ancestry, history, ideology, and language (71, 72). The level of genetic differentiation (i.e., time since common ancestor) between early CW individuals with high and no steppe ancestry implies long biological isolation and hence different histories. The finding of GAC-like and Yamnaya-like genetic profiles in early CW suggests integration of people who came from ideologically diverse societies (i.e., neither GAC nor Yamnaya practiced strong gender differentiation in mortuary practices, unlike CW). It is likely that GAC and CW/Yamnaya individuals spoke different languages (3, 4, 43), meaning that early CW society in Bohemia encompassed people who had demonstrably different histories, likely originating from ideologically diverse cultures, who spoke different mother tongues.

The assimilation process of individuals without steppe ancestry into early CW society was female-biased (43). However, finding females also among individuals with the highest amounts of steppe ancestry (3 of 5; Fig. 2B) suggests that they were also well represented among migrating CW individuals [in contrast to (43)] or perhaps assimilated from nearby Yamnaya groups (e.g., Hungary). Finding individuals without steppe ancestry in early CW contexts (n = 4) is more common than individuals with steppe ancestry in pre-CW contexts (e.g., GAC, n = 0). This pattern of asymmetric gene flow between the contemporaneous GAC and CW may reflect newcomers (CW groups) having more benefit from incorporating people with important local knowledge (i.e., from pre-CW cultural contexts) into their communities. The archaeological record shows continuity of such knowledge (e.g., pottery production and lithic raw materials) in several regions (22, 67, 73).

Vliněves is crucial for elucidating interactions between individuals with high and no steppe ancestry. This site yields the earliest dated CW (VLI076, 3018 to 2901 BCE) who is also genetically most differentiated from pre-CW individuals, while 20% (3 of 15) of the sampled early CW from Vliněves had no steppe ancestry. Intriguingly, we observe no archaeological differences between CW graves of individuals with and without steppe ancestry from two sites (Vliněves and Stadice; see the Supplementary Materials), suggesting full integration of genetically, and likely ethnically, diverse individuals within the same archaeological culture.

Finding Latvia_MN-like ancestry in early CW, in conjunction with the absence of Y-chromosomal sharing between early CW and Yamnaya males, suggests a limited or indirect role of known Yamnaya in the origin and spread of CW to central Europe. Our results allude to either a northeast European Eneolithic forest steppe contribution to early CW [a region consistent with some interpretations of the archaeological evidence (57)] or a hitherto unsampled steppe population who carried excess Latvia_MN-like ancestry, a scenario that is less likely given the high degree of genetic homogeneity among 3000-BCE steppe groups [e.g., Yamnaya and Afanasievo separated by ~2500 km but genetically almost indistinguishable (4, 61)]. As much of 4000- to 2500-BCE (north)eastern Europe remains unsampled, inferring the precise geographic origin of early CW individuals remains elusive.

Since social kinship systems influence patterns of genetic diversity (13, 42, 48, 74), it is likely that several different kin systems existed in third millennium BCE central Europe. The highly diverse genetic profiles (both nuclear and Y-chromosomal) of early CW suggest a different social organization to late CW and BB, whose Y chromosome pattern is indicative of strict patrilineality. This suggests that different cultural groups, in addition to using various forms of material culture and mortuary practices, likely also conformed to different ideologies as expressed in their mating pattern and/or social organization. This is supported by the finding of completely nonoverlapping Y chromosome variation between the partially contemporaneous late CW and BB, indicating a large degree of paternal mating isolation between these two groups, even when found at the same site (e.g., Vliněves).

The onset of the preclassical Únětice was accompanied by a ≥40% nuclear and ≥80% Y-chromosomal contribution ultimately originating from the northeast and breaking down the gender-differentiated mortuary practices and strict patrilineality of late CW and BB. This was neither evident in the burial customs nor in the material culture but could represent the underlying connection to the Baltics, the ultimate source of EBA amber in Bohemia associated with the later emerging Amber Road (75–77). Therefore, our results suggest two main periods (early CW and early Únětice) of genetic influence from the northeast, much of which remains unsampled in the European archaeogenetic record (e.g., Belarus).

Our results reveal a complex and highly dynamic history of Neolithic to EBA central Europe, during which migration and the movement of people facilitated abrupt genetic and social changes. Large-scale demic expansions occurred multiple times before and after the appearance of steppe ancestry in Europe. Early CW society was diverse and emerged amid a strong cultural and genetic transition, involving males and females of diverse origins and likely ethnicities. Genetic shifts occurred within CW, BB, and EBA societies despite continuity in material culture. Cultural affiliations played a major role in third millennium BCE social behaviors, which ultimately changed with the influx of new people over time. Although the impact of social processes is observable in patterns of genetic diversity, further interdisciplinary research is required to characterize the drivers of these changes, both at a micro- and macro-regional level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Processing sites for the newly reported individuals

Most (186 of 206, 90.2%) of the newly reported individuals were entirely processed at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany, and the full details of sampling and ancient DNA wet laboratory work and bioinformatic processing are summarized in what follows. The individuals from the site Makotřasy were initially sampled and processed into powder at the University of Vienna, followed by subsequent laboratory work and bioinformatic and ancient DNA analysis at Harvard Medical School following previously described protocols (61).

Sampling

In total, 389 pars petrosa, teeth, and bones from 261 individuals were processed as part of this study. Upon introduction into the clean room facilities at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany, all samples were wiped with 5% bleach and ultraviolet (UV) irradiated for 20 min on each side. Teeth were sampled by removing the crown followed by drilling into the pulp chamber to create bone powder. Pars petrosa were sampled by drilling into their dense region (78) to create bone powder. Between 50 and 100 mg of resulting bone powder from each sample were collected in different 2-ml Biopure tubes (one tube per sample) and used in subsequent DNA extraction.

DNA extraction

One milliliter of extraction buffer [containing 0.9 ml of 0.5 M EDTA, 0.025 ml of proteinase K (0.25 mg/ml), and 0.075 ml of UV high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) water] was added to Biopure tubes containing bone powder. Biopure tubes were then sealed with Parafilm and incubated overnight on a rotating wheel at 37°C. After incubation, Biopure tubes were spun for 2 min at 18,500 relative centrifugal force (rcf), separating the soluble from insoluble parts of the resulting solution. The soluble part was transferred to a 50-ml falcon tube containing 10 ml of binding buffer and 400 μl of sodium acetate (3 M, pH 5.2). Resulting mixture was transferred to a high pure extender assembly (HPEA) falcon tube, which was centrifuged at 1500 rpm in a 50-ml Thermo Fisher Scientific TX-400 Swinging Bucket Rotor for 8 min. The column from each HPEA tube was removed and inserted into a fresh collection tube and centrifuged at 18,500 rcf for 2 min. A total of 450 μl of wash buffer from the high pure viral nucleic acid kit (HPVNAK) was added to each column, which was then centrifuged at 8000 rcf for 1 min. Columns were then removed and placed into new collection tubes. Another round of washing was performed whereby 450 μl of wash buffer from the HPVNAK was added to each column and centrifuged at 8000 rcf for 1 min. Columns containing washed DNA were then transferred to 1.5-ml siliconized tubes. Fifty microliters of TET (tris-EDTA + Tween 20) buffer were added to the center of columns, and the columns were then incubated at room temperature for 3 min and centrifuged at 18,500 rcf for 1 min. Another 50 μl of TET buffer was added to the center of columns, after which they were centrifuged once more at 18,500 rcf for 1 min. The resulting 100 μl of DNA extracts was stored at −20°C until further processing.

DNA libraries and in-solution capture

Twenty-five microliters of DNA extract was used for the construction of (in most cases) double-stranded uracil DNA glycosylase (UDG) half-treated DNA libraries. UDG repair was performed by adding DNA extract to a 25-μl mastermix containing 6 μl of 10× Buffer Tango, 6 μl of 10 mM adenosine 5′-triphosphate, 0.5 μl of bovine serum albumin (BSA; 20 mg/ml), 0.2 μl of 25 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 3.6 μl of 1-U USER enzyme, and 8.7 μl of UV HPLC water. Resulting mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min followed by 12°C for 1 min. Inhibition of UDG treatment was achieved through the addition of 3.6 μl of 2-U uracil glycosylase inhibitor (UGI) to each tube followed by incubation at 37°C for 30 min and again at 12°C for 1 min. Blunt-end repair was performed by adding 3 μl of 10-U T4 polynucleotide kinase and 1.65 μl of 3-U T4 DNA polymerase and incubating the resulting mixture at 25°C for 20 min and then at 12°C for 10 min. Blunt-end repaired mixture was purified using a MinElute kit and eluted in 20 μl of elution buffer (EB) containing 0.05% Tween. Illumina adapters were ligated onto DNA molecules through the mixture of 18 μl of eluate from the previous step with 20 μl of 2× Quick Ligase Buffer, 1 μl of 10 μM Adapter Mix, and 1 μl of 5-U Quick Ligase. Resulting mixture was incubated at 22°C for 20 min followed by purification with a MinElute kit and elution in 22 μl of EB containing 0.05% Tween. Adapter fill in reaction was performed by adding 20 μl of eluate from the previous step to 4 μl of 10× isothermal buffer, 0.2 μl of 25 mM each dNTP, 2 μl of 8-U Bst 2.0 polymerase, and 13.8 μl of UV HPLC water, followed by incubation at 37°C for 30 min and 80°C for 10 min. Resulting libraries were stored at −20°C until further processing. Unique library-specific indexes were added to the 5′ and 3′ ends of molecules in each library through an indexing polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Each library was split into four separate indexing PCR reactions, which were carried out using 10 μl of 10× Pfu Turbo buffer, 1.5 μl of BSA (20 mg/ml), 1 μl of 25 mM each dNTP, 1 μl of 2.5-U Pfu Turbo polymerase, 73.5 μl of UV HPLC water, 2 μl of 10 μM P5 index, 2 μl of 10 μM P7 index, and 9 μl of DNA library. Amplification was achieved through an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 10 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by 72°C for 10 min. Resulting indexed libraries of the same sample were pooled and purified using a MinElute purification kit. Purified libraries were quantified using quantitative PCR and amplified to 1013 copies. Amplified libraries were shallow shotgun sequenced (~5 million reads) on an Illumina HiSeq or NextSeq platform to estimate the general human DNA content, presence of ancient DNA damage, and mitochondrial:nuclear coverage ratio. Libraries with >0.1% endogenous human DNA and >5% C-to-T misincorporations at the 5′ end were chosen for 1240k capture (8) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) capture. In cases where more than one library from the same individual satisfied the criteria for capture, the better quality (higher endogenous DNA content) library was used for 1240k and mtDNA capture.

Sequencing

Postcapture libraries were single-end (75 cycles) or paired-end sequenced (2 × 50 or 2 × 75) on HiSeq or NextSeq Illumina platforms to a depth of 20 to 50 million reads per library. Resulting sequence data were processed through EAGER (v1.92.38) (79). Illumina adapters were removed using AdapterRemoval (v2.2.0) (80), and in case of paired-end sequencing, corresponding reads from the same template molecule with a minimum of 11 base pairs (bp) of overlap were merged. Fastq files of merged and unmerged reads were concatenated, and reads shorter than 30 bp were discarded. Processed reads were mapped to the human reference genome (hg19) using BWA-aln and BWA-samse (v0.7.12) (81) applying maxdiff (-n) 0.01 and seeding turned off (-l 10000). Resulting bam files were sorted, and duplicate reads were removed using DeDup (v0.12.1) (https://github.com/apeltzer/DeDup). Damageprofiler (v0.3.10) (https://github.com/Integrative-Transcriptomics/DamageProfiler) was used to calculate rates of misincorporation in read termini of DNA fragments in our captured libraries. BAM files had the last three bases from both 5′ and 3′ ends of reads and corresponding base quality scores masked for downstream analyses (82).

Sex determination and authentication

The genetic sex of each sample (bam file) was determined by calculating the normalized mean coverage on the X (mean X coverage/mean autosome coverage) and Y (mean Y coverage/mean autosomal coverage) chromosomes (83). Samples with normalized mean Y coverage values greater than 0.2 were assigned male. Contamination was estimated in males by calculating the rate of heterozygosity on their X chromosome (84). In addition, we used Schmutzi to estimate the mitochondrial contamination in all libraries (85). Schmutzi was run on BAM files resulting from mapping 1240K capture sequencing data to the human mitochondrial reference genome. In cases where 1240k data were not enough to give an mtDNA contamination, we ran Schmutzi on the mtDNA capture data mapped to the human mitochondrial reference genome.

Genotyping

We used SAMtools (v1.3) (86) mpileup and pileupCaller from the sequenceTools (v1.4.0.2) package (https://github.com/stschiff/sequenceTools) to call pseudo diploid genotypes by sampling a random high-quality allele (base quality, ≥30; mapping quality, ≥30) from each of the 1240k sites (8). Newly generated genotype data for this study were then merged to a compiled dataset of previously published ancient and modern worldwide populations (https://reich.hms.harvard.edu/allen-ancient-dna-resource-aadr-downloadable-genotypes-present-day-and-ancient-dna-data) (v42.2) using mergeit (v2450) from the EIGENSOFT package (https://github.com/DReichLab/EIG).

Mitochondrial and Y chromosome haplogroups

Mitochondrial haplogroups were called by mapping 1240k or mtDNA capture data to the human mitochondrial reference genome followed by creating pileups at each position (map quality and base quality filter of 30) and calling the most frequent base at each position. Resulting genotype information was converted to fasta files, and haplogroups were called using haplofind (87). Y chromosome haplogroups were called by mapping 1240k capture data to the whole human reference genome (hg19) followed by visual inspection of ancestral/derived alleles (after map quality and base quality filter of 30) at ISOGG (v15.58 April 2020) sites.

Principal components analysis

PCA was conducted using smartpca (v1600) from the Eigensoft package (https://github.com/DReichLab/EIG). Principal components were calculated on the genotype data of modern West Eurasian individuals (table S7) (88–90). Ancient individuals were projected (lsqproject: YES) onto the axes calculated from modern individuals. “shrinkmode: YES” was used to account for artificial stretching of principal component axes between projected (ancient) individuals and modern individuals. Fst values were also calculated in smartpca using “fsthiprecision: YES” and “inbreed: YES” parameters.

Ancestry decomposition and admixture modeling

F statistics, qpWave, and qpAdm runs were conducted in admixr v0.7.1 (91), a wrapper program around ADMIXTOOLS (88). Selection of outgroups for each analysis is indicated in the corresponding Supplementary Table.

Linear modeling of pre-CW HG ancestry (Fig. 3A) was performed using segmented linear regression as implemented in R using the segmented function for v.1.2-0 of the segmented library (92). To select the optimal number of breakpoints, we compared Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) for models with between zero and four breakpoints. The AIC is a score that considers how well a model fits the data while simultaneously penalizing models with additional parameters. In this way, model fit must be significantly improved for a more complicated model with additional parameters to be accepted over a simpler, nested model. A linear regression model with one breakpoint was found to have the minimum AIC and hence was selected (93).

DATES v753 (61) was used to estimate length distributions of ancestry tracts and infer admixture dates between Anatolia_Neolithic and WHG (here, Loschbour+Körös_HG+Germany_BDB). Parameters binsize 0.001, maxdis 1, seed 77, jackknife YES, qbin 10, runfit YES, afffit YES, lovalfit 0.45, minparentcount 1, and checkmap YES were used.

Y haplogroup frequency simulations

To investigate the process of Y-haplogroup inheritance in early and late CW groups, we simulated 106 realizations, assuming a generational time of 25 years, and analyzed the results using approximate Bayesian computation (ABC). For the ith realization, we assumed a constant population size of Ni ~ U(102,104), with a starting a proportion of R1a-M417(xZ645) of pi ~ TN(0, 1)(0.27,0.134) from a truncated normal distribution based on the observed proportion of R1a-M417(xZ645) of 3 of 11 (0.27). For each simulation, we also included a selection coefficient denoted si ~ U(−1,1). Under random mating, for generation j + 1, let the number of a male offspring carrying R1a-M417(xZ645) be Xij+1 ~ B(Ni, wj), where wj = Xj−1/Nj−1. However, if one includes a selection coefficient, then wj = min(1,(1 + si)Xj−1/Nj−1). Hence, one may interpret sj as the average increase in the proportion of male offspring that R1a-M417(xZ645) individuals were having over this period. We then compared our observed number of per-generation R1a-M417(xZ645) to our simulated realizations using the rejection method and keeping the top closest 0.05% realizations (selected via cross-validation) to form samples from the joint posterior distributions for our simulation parameters. All ABC and cross-validation analyses were performed in R using the abc package (94).

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Kaupová and E. Zazvonilová for the help during sample collection; G. Brandt, A. Wissgott, E. Hoché, M. Himmel, and V. Wanka for the laboratory support; and S. Clayton and K. Prüfer for processing the raw sequencing data. We thank M. Furholt, H. Ringbauer, A. Childebayeva, and the population genetics group of the Department of Archaeogenetics for suggestions and valuable feedback. We thank M. O’Reilly and H. Sell for graphics support. D.R. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Funding: This work was supported by the following: Max Planck Society; European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreements no. 771234–PALEoRIDER (to W.H.) and no. 788616–YMPACT (to V.H.); John Templeton Foundation grant 61220 (to D.R.); Paul Allen Family Foundation (to D.R.); Czech Academy of Sciences award Praemium Academiae (to M.E.); Institutional program RVO 67985912 of the Institute of Archaeology of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague (to M.E. and M.Dobe.); Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic grant DKRVO 2019-2023/7.l.c., 00023272 (to P.V. and M.Dobi.); Long-term Development Project RV67985939 (to J.Ko.); and Czech Science Foundation 19-20970Y (to J.Ko.), Author contributions: Conceptualization: M.E., M.Dobe., and W.H. Supervision: W.H. and S.S. Archaeological material and methodology: M.E., M.Dobe., M.L., P.V., M.Kun., H.B., D.D., A.D., M.Dobi., J.H., D.J.K., B.C., J.Kl., M.Ko., P.K., M.Kuc., J.K.H., P.L., D.M., L.M., M.P., K.P., E.P., R.P., D.R., P.S., L.S., J.Š., R.Š., O.Š., M.T., M.V., and J.Kr. Laboratory work: L.P., F.A., G.U.N., M.A.S., and N.R. Data analysis: L.P., A.B.R., S.S., and W.H. Contextualization: M.E., M.Dobe., J.Ko., and V.H. Visualization: L.P., M.E., M.Dobe., M.L., and W.H. Writing—archaeological sections: M.E., M.Dobe., and M.L. Writing: L.P., M.E., M.Dobe., V.H., and W.H. with input from all coauthors. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The aligned sequences are available through the European Nucleotide Archive under accession number PRJEB45006. Haploid genotype data for the 1240k panel are available in eigenstrat format via the Edmond Data Repository of the Max Planck Society (https://edmond.mpdl.mpg.de).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/7/35/eabi6941/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Bramanti B., Thomas M. G., Haak W., Unterlaender M., Jores P., Tambets K., Antanaitis-Jacobs I., Haidle M. N., Jankauskas R., Kind C.-J., Lueth F., Terberger T., Hiller J., Matsumura S., Forster P., Burger J., Genetic discontinuity between local hunter-gatherers and central Europe’s first farmers. Science 326, 137–140 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt G., Haak W., Adler C. J., Roth C., Szécsényi-Nagy A., Karimnia S., Möller-Rieker S., Meller H., Ganslmeier R., Friederich S., Dresely V., Nicklisch N., Pickrell J. K., Sirocko F., Reich D., Cooper A., Alt K. W.; Genographic Consortium , Ancient DNA reveals key stages in the formation of central European mitochondrial genetic diversity. Science 342, 257–261 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haak W., Lazaridis I., Patterson N., Rohland N., Mallick S., Llamas B., Brandt G., Nordenfelt S., Harney E., Stewardson K., Fu Q., Mittnik A., Bánffy E., Economou C., Francken M., Friederich S., Pena R. G., Hallgren F., Khartanovich V., Khokhlov A., Kunst M., Kuznetsov P., Meller H., Mochalov O., Moiseyev V., Nicklisch N., Pichler S. L., Risch R., Guerra M. A. R., Roth C., Szécsényi-Nagy A., Wahl J., Meyer M., Krause J., Brown D., Anthony D., Cooper A., Alt K. W., Reich D., Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature 522, 207–211 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allentoft M. E., Sikora M., Sjögren K.-G., Rasmussen S., Rasmussen M., Stenderup J., Damgaard P. B., Schroeder H., Ahlström T., Vinner L., Malaspinas A.-S., Margaryan A., Higham T., Chivall D., Lynnerup N., Harvig L., Baron J., Casa P. D., Dąbrowski P., Duffy P. R., Ebel A. V., Epimakhov A., Frei K., Furmanek M., Gralak T., Gromov A., Gronkiewicz S., Grupe G., Hajdu T., Jarysz R., Khartanovich V., Khokhlov A., Kiss V., Kolář J., Kriiska A., Lasak I., Longhi C., McGlynn G., Merkevicius A., Merkyte I., Metspalu M., Mkrtchyan R., Moiseyev V., Paja L., Pálfi G., Pokutta D., Pospieszny Ł., Price T. D., Saag L., Sablin M., Shishlina N., Smrčka V., Soenov V. I., Szeverényi V., Tóth G., Trifanova S. V., Varul L., Vicze M., Yepiskoposyan L., Zhitenev V., Orlando L., Sicheritz-Pontén T., Brunak S., Nielsen R., Kristiansen K., Willerslev E., Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. Nature 522, 167–172 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olalde I., Brace S., Allentoft M. E., Armit I., Kristiansen K., Booth T., Rohland N., Mallick S., Szécsényi-Nagy A., Mittnik A., Altena E., Lipson M., Lazaridis I., Harper T. K., Patterson N., Broomandkhoshbacht N., Diekmann Y., Faltyskova Z., Fernandes D., Ferry M., Harney E., de Knijff P., Michel M., Oppenheimer J., Stewardson K., Barclay A., Alt K. W., Liesau C., Ríos P., Blasco C., Miguel J. V., García R. M., Fernández A. A., Bánffy E., Bernabò-Brea M., Billoin D., Bonsall C., Bonsall L., Allen T., Büster L., Carver S., Navarro L. C., Craig O. E., Cook G. T., Cunliffe B., Denaire A., Dinwiddy K. E., Dodwell N., Ernée M., Evans C., Kuchařík M., Farré J. F., Fowler C., Gazenbeek M., Pena R. G., Haber-Uriarte M., Haduch E., Hey G., Jowett N., Knowles T., Massy K., Pfrengle S., Lefranc P., Lemercier O., Lefebvre A., Martínez C. H., Olmo V. G., Ramírez A. B., Maurandi J. L., Majó T., McKinley J. I., McSweeney K., Mende B. G., Modi A., Kulcsár G., Kiss V., Czene A., Patay R., Endrődi A., Köhler K., Hajdu T., Szeniczey T., Dani J., Bernert Z., Hoole M., Cheronet O., Keating D., Velemínský P., Dobeš M., Candilio F., Brown F., Fernández R. F., Herrero-Corral A.-M., Tusa S., Carnieri E., Lentini L., Valenti A., Zanini A., Waddington C., Delibes G., Guerra-Doce E., Neil B., Brittain M., Luke M., Mortimer R., Desideri J., Besse M., Brücken G., Furmanek M., Hałuszko A., Mackiewicz M., Rapiński A., Leach S., Soriano I., Lillios K. T., Cardoso J. L., Pearson M. P., Włodarczak P., Price T. D., Prieto P., Rey P.-J., Risch R., Guerra M. A. R., Schmitt A., Serralongue J., Silva A. M., Smrčka V., Vergnaud L., Zilhão J., Caramelli D., Higham T., Thomas M. G., Kennett D. J., Fokkens H., Heyd V., Sheridan A., Sjögren K.-G., Stockhammer P. W., Krause J., Pinhasi R., Haak W., Barnes I., Lalueza-Fox C., Reich D., The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe. Nature 555, 190–196 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.C. Perlès, The Early Neolithic in Greece: The First Farming Communities in Europe (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.-D. Schoop, in How did farming reach Europe?: Anatolian-European relations from the second half of the 7th through the first half of the 6th millenium cal BC ; proceedings of the International Workshop ; Istanbul, 20–22 May 2004, C. Lichter, R. Meriç, Eds. (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. Abteilung Istanbul, İstanbul, 2005), Byzas, pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathieson I., Lazaridis I., Rohland N., Mallick S., Patterson N., Roodenberg S. A., Harney E., Stewardson K., Fernandes D., Novak M., Sirak K., Gamba C., Jones E. R., Llamas B., Dryomov S., Pickrell J., Arsuaga J. L., de Castro J. M. B., Carbonell E., Gerritsen F., Khokhlov A., Kuznetsov P., Lozano M., Meller H., Mochalov O., Moiseyev V., Guerra M. A. R., Roodenberg J., Vergès J. M., Krause J., Cooper A., Alt K. W., Brown D., Anthony D., Lalueza-Fox C., Haak W., Pinhasi R., Reich D., Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature 528, 499–503 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazaridis I., Nadel D., Rollefson G., Merrett D. C., Rohland N., Mallick S., Fernandes D., Novak M., Gamarra B., Sirak K., Connell S., Stewardson K., Harney E., Fu Q., Gonzalez-Fortes G., Jones E. R., Roodenberg S. A., Lengyel G., Bocquentin F., Gasparian B., Monge J. M., Gregg M., Eshed V., Mizrahi A.-S., Meiklejohn C., Gerritsen F., Bejenaru L., Blüher M., Campbell A., Cavalleri G., Comas D., Froguel P., Gilbert E., Kerr S. M., Kovacs P., Krause J., McGettigan D., Merrigan M., Merriwether D. A., O’Reilly S., Richards M. B., Semino O., Shamoon-Pour M., Stefanescu G., Stumvoll M., Tönjes A., Torroni A., Wilson J. F., Yengo L., Hovhannisyan N. A., Patterson N., Pinhasi R., Reich D., Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East. Nature 536, 419–424 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofmanová Z., Kreutzer S., Hellenthal G., Sell C., Diekmann Y., Díez-Del-Molino D., van Dorp L., López S., Kousathanas A., Link V., Kirsanow K., Cassidy L. M., Martiniano R., Strobel M., Scheu A., Kotsakis K., Halstead P., Triantaphyllou S., Kyparissi-Apostolika N., Urem-Kotsou D., Ziota C., Adaktylou F., Gopalan S., Bobo D. M., Winkelbach L., Blöcher J., Unterländer M., Leuenberger C., Çilingiroğlu Ç., Horejs B., Gerritsen F., Shennan S. J., Bradley D. G., Currat M., Veeramah K. R., Wegmann D., Thomas M. G., Papageorgopoulou C., Burger J., Early farmers from across Europe directly descended from Neolithic Aegeans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 6886–6891 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipson M., Szécsényi-Nagy A., Mallick S., Pósa A., Stégmár B., Keerl V., Rohland N., Stewardson K., Ferry M., Michel M., Oppenheimer J., Broomandkhoshbacht N., Harney E., Nordenfelt S., Llamas B., Mende B. G., Köhler K., Oross K., Bondár M., Marton T., Osztás A., Jakucs J., Paluch T., Horváth F., Csengeri P., Koós J., Sebők K., Anders A., Raczky P., Regenye J., Barna J. P., Fábián S., Serlegi G., Toldi Z., Nagy E. G., Dani J., Molnár E., Pálfi G., Márk L., Melegh B., Bánfai Z., Domboróczki L., Fernández-Eraso J., Mujika-Alustiza J. A., Fernández C. A., Echevarría J. J., Bollongino R., Orschiedt J., Schierhold K., Meller H., Cooper A., Burger J., Bánffy E., Alt K. W., Lalueza-Fox C., Haak W., Reich D., Parallel palaeogenomic transects reveal complex genetic history of early European farmers. Nature 551, 368–372 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rivollat M., Jeong C., Schiffels S., Küçükkalıpçı İ., Pemonge M.-H., Rohrlach A. B., Alt K. W., Binder D., Friederich S., Ghesquière E., Gronenborn D., Laporte L., Lefranc P., Meller H., Réveillas H., Rosenstock E., Rottier S., Scarre C., Soler L., Wahl J., Krause J., Deguilloux M.-F., Haak W., Ancient genome-wide DNA from France highlights the complexity of interactions between Mesolithic hunter-gatherers and Neolithic farmers. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz5344 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schroeder H., Margaryan A., Szmyt M., Theulot B., Włodarczak P., Rasmussen S., Gopalakrishnan S., Szczepanek A., Konopka T., Jensen T. Z. T., Witkowska B., Wilk S., Przybyła M. M., Pospieszny Ł., Sjögren K.-G., Belka Z., Olsen J., Kristiansen K., Willerslev E., Frei K. M., Sikora M., Johannsen N. N., Allentoft M. E., Unraveling ancestry, kinship, and violence in a Late Neolithic mass grave. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 10705–10710 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.J. Schibler, in Umwelt, Wirtschaft, Siedlungen im dritten vorchristlichen Jahrtausend Mitteleuropas und Süskandinaviens: Interntionale Tagung Kiel 4.-6. November 2005, W. Dörfler, J. Müller, Eds. (Wachholtz, Neumünster, 2008), Offa-Bücher, pp. 379–391.

- 15.C. Becker, in Umwelt, Wirtschaft, Siedlungen im dritten vorchristlichen Jahrtausend Mitteleuropas und Südskandinaviens: Internationale Tagung Kiel 4.-6. November 2005, W. Dörfler, J. Müller, Eds. (Wachholtz, Neumünster, 2008), Offa-Bücher, pp. 287–299.

- 16.V. M. Heyd, in Is there a British Chalcolithic?: People, Place and Polity in the Later 3rd Millennium BC, M. J. Allen, J. Gardiner, A. Sheridan, Eds. (Oxbow Books, London & Oxford, 2012), vol. 4 of Prehistoric Society Research Paper, pp. 98–114. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Müller J., Seregély T., Becker C., Christensen A.-M., Fuchs M., Kroll H., Mischka D., Schüssler U., A revision of Corded Ware settlement pattern – new results from the central European low mountain range. Proc. Prehis. Soc. 75, 125–142 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 18.M. Buchvaldek, Kultura se šňůrovou keramikou ve střední Evropě 1. Skupiny mezi Harzem a Bílými Karpaty (Univerzita Karlova, 1985), vol. 12 of Praehistorica.

- 19.Bourgeois Q., Kroon E., The impact of male burials on the construction of Corded Ware identity: Reconstructing networks of information in the 3rd millennium BC. PLOS ONE 12, e0185971 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furholt M., Upending a “totality”: Re-evaluating Corded Ware variability in Late Neolithic Europe. Proc. Prehis. Soc. 80, 67–86 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furholt M., Re-integrating archaeology: A contribution to aDNA studies and the migration discourse on the 3rd millennium BC in europe. Proc. Prehis. Soc. 85, 115–129 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 22.J. Kolář, Archaeology of Local Interactions: Social and Spatial Aspects of the Corded Ware Communities in Moravia (Verlag Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, 2018), vol. 31 of Studien zur Archäologie Europas. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saag L., Varul L., Scheib C. L., Stenderup J., Allentoft M. E., Saag L., Pagani L., Reidla M., Tambets K., Metspalu E., Kriiska A., Willerslev E., Kivisild T., Metspalu M., Extensive farming in estonia started through a sex-biased migration from the steppe. Curr. Biol. 27, 2185–2193.e6 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malmström H., Günther T., Svensson E. M., Juras A., Fraser M., Munters A. R., Pospieszny Ł., Tõrv M., Lindström J., Götherström A., Storå J., Jakobsson M., The genomic ancestry of the Scandinavian Battle Axe Culture people and their relation to the broader Corded Ware horizon. Proc. Biol. Sci. 286, 20191528 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furtwängler A., Rohrlach A. B., Lamnidis T. C., Papac L., Neumann G. U., Siebke I., Reiter E., Steuri N., Hald J., Denaire A., Schnitzler B., Wahl J., Ramstein M., Schuenemann V. J., Stockhammer P. W., Hafner A., Lösch S., Haak W., Schiffels S., Krause J., Ancient genomes reveal social and genetic structure of Late Neolithic Switzerland. Nat. Commun. 11, 1915 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linderholm A., Kılınç G. M., Szczepanek A., Włodarczak P., Jarosz P., Belka Z., Dopieralska J., Werens K., Górski J., Mazurek M., Hozer M., Rybicka M., Ostrowski M., Bagińska J., Koman W., Rodríguez-Varela R., Storå J., Götherström A., Krzewińska M., Corded Ware cultural complexity uncovered using genomic and isotopic analysis from south-eastern Poland. Sci. Rep. 10, 6885 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saag L., Vasilyev S. V., Varul L., Kosorukova N. V., Gerasimov D. V., Oshibkina S. V., Griffith S. J., Solnik A., Saag L., D’Atanasio E., Metspalu E., Reidla M., Rootsi S., Kivisild T., Scheib C. L., Tambets K., Kriiska A., Metspalu M., Genetic ancestry changes in Stone to Bronze age transition in the East European plain. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd6535 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cassidy L. M., Martiniano R., Murphy E. M., Teasdale M. D., Mallory J., Hartwell B., Bradley D. G., Neolithic and Bronze Age migration to Ireland and establishment of the insular Atlantic genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 368–373 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martiniano R., Cassidy L. M., Ó’Maoldúin R., McLaughlin R., Silva N. M., Manco L., Fidalgo D., Pereira T., Coelho M. J., Serra M., Burger J., Parreira R., Moran E., Valera A. C., Porfirio E., Boaventura R., Silva A. M., Bradley D. G., The population genomics of archaeological transition in west Iberia: Investigation of ancient substructure using imputation and haplotype-based methods. PLOS Genet. 13, e1006852 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olalde I., Mallick S., Patterson N., Rohland N., Villalba-Mouco V., Silva M., Dulias K., Edwards C. J., Gandini F., Pala M., Soares P., Ferrando-Bernal M., Adamski N., Broomandkhoshbacht N., Cheronet O., Culleton B. J., Fernandes D., Lawson A. M., Mah M., Oppenheimer J., Stewardson K., Zhang Z., Jiménez Arenas J. M., Toro Moyano I. J., Salazar-García D. C., Castanyer P., Santos M., Tremoleda J., Lozano M., García Borja P., Fernández-Eraso J., Mujika-Alustiza J. A., Barroso C., Bermúdez F. J., Viguera Mínguez E., Burch J., Coromina N., Vivó D., Cebrià A., Fullola J. M., García-Puchol O., Morales J. I., Oms F. X., Majó T., Vergès J. M., Díaz-Carvajal A., Ollich-Castanyer I., López-Cachero F. J., Silva A. M., Alonso-Fernández C., de Castro G. D., Echevarría J. J., Moreno-Márquez A., Berlanga G. P., Ramos-García P., Ramos-Muñoz J., Vila E. V., Arzo G. A., Arroyo Á. E., Lillios K. T., Mack J., Velasco-Vázquez J., Waterman A., de Lugo Enrich L. B., Sánchez M. B., Agustí B., Codina F., de Prado G., Estalrrich A., Fernández Flores Á., Finlayson C., Finlayson G., Finlayson S., Giles-Guzmán F., Rosas A., Barciela González V., García Atiénzar G., Hernández Pérez M. S., Llanos A., Carrión Marco Y., Collado Beneyto I., López-Serrano D., Sanz Tormo M., Valera A. C., Blasco C., Liesau C., Ríos P., Daura J., de Pedro Michó M. J., Diez-Castillo A. A., Fernández R. F., Farré J. F., Garrido-Pena R., Gonçalves V. S., Guerra-Doce E., Herrero-Corral A. M., Juan-Cabanilles J., López-Reyes D., McClure S. B., Pérez M. M., Foix A. O., Borràs M. S., Sousa A. C., Encinas J. M. V., Kennett D. J., Richards M. B., Alt K. W., Haak W., Pinhasi R., Lalueza-Fox C., Reich D., The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years. Science 363, 1230–1234 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcus J. H., Posth C., Ringbauer H., Lai L., Skeates R., Sidore C., Beckett J., Furtwängler A., Olivieri A., Chiang C. W. K., Al-Asadi H., Dey K., Joseph T. A., Liu C.-C., Der Sarkissian C., Radzevičiūtė R., Michel M., Gradoli M. G., Marongiu P., Rubino S., Mazzarello V., Rovina D., La Fragola A., Serra R. M., Bandiera P., Bianucci R., Pompianu E., Murgia C., Guirguis M., Orquin R. P., Tuross N., van Dommelen P., Haak W., Reich D., Schlessinger D., Cucca F., Krause J., Novembre J., Genetic history from the Middle Neolithic to present on the Mediterranean island of Sardinia. Nat. Commun. 11, 939 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernandes D. M., Mittnik A., Olalde I., Lazaridis I., Cheronet O., Rohland N., Mallick S., Bernardos R., Broomandkhoshbacht N., Carlsson J., Culleton B. J., Ferry M., Gamarra B., Lari M., Mah M., Michel M., Modi A., Novak M., Oppenheimer J., Sirak K. A., Stewardson K., Mandl K., Schattke C., Özdoğan K. T., Lucci M., Gasperetti G., Candilio F., Salis G., Vai S., Camarós E., Calò C., Catalano G., Cueto M., Forgia V., Lozano M., Marini E., Micheletti M., Miccichè R. M., Palombo M. R., Ramis D., Schimmenti V., Sureda P., Teira L., Teschler-Nicola M., Kennett D. J., Lalueza-Fox C., Patterson N., Sineo L., Coppa A., Caramelli D., Pinhasi R., Reich D., The spread of steppe and Iranian-related ancestry in the islands of the western Mediterranean. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 334–345 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vander Linden M., Population history in third-millennium-BC Europe: Assessing the contribution of genetics. World Archaeol. 48, 714–728 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heyd V., Kossinna’s smile. Antiquity 91, 348–359 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klejn L. S., The steppe hypothesis of Indo-European origins remains to be proven. Acta Archaeol. 88, 193–204 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klejn L. S., Haak W., Lazaridis I., Patterson N., Reich D., Kristiansen K., Sjögren K.-G., Allentoft M., Sikora M., Willerslev E., Discussion: Are the origins of Indo-European languages explained by the migration of the Yamnaya Culture to the West. Eur. J. Archaeol. 21, 3–17 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furholt M., Massive migrations? The impact of recent aDNA studies on our view of third millennium europe. Eur. J. Archaeol. 21, 159–191 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Furholt M., De-contaminating the aDNA – archaeology dialogue on mobility and migration: Discussing the culture-historical legacy. Current Swedish Archaeology. 27, 53–68 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Furholt M., Mobility and social change: Understanding the european neolithic period after the archaeogenetic revolution. J. Archaeol. Res. , (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frieman C. J., Hofmann D., Present pasts in the archaeology of genetics, identity, and migration in Europe: A critical essay. World Archaeol. 51, 528–545 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldberg A., Günther T., Rosenberg N. A., Jakobsson M., Ancient X chromosomes reveal contrasting sex bias in Neolithic and Bronze Age Eurasian migrations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 2657–2662 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mittnik A., Massy K., Knipper C., Wittenborn F., Friedrich R., Pfrengle S., Burri M., Carlichi-Witjes N., Deeg H., Furtwängler A., Harbeck M., von Heyking K., Kociumaka C., Kucukkalipci I., Lindauer S., Metz S., Staskiewicz A., Thiel A., Wahl J., Haak W., Pernicka E., Schiffels S., Stockhammer P. W., Krause J., Kinship-based social inequality in Bronze Age Europe. Science 366, 731–734 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kristiansen K., Allentoft M. E., Frei K. M., Iversen R., Johannsen N. N., Kroonen G., Pospieszny Ł., Douglas Price T., Rasmussen S., Sjögren K.-G., Sikora M., Willerslev E., Re-theorising mobility and the formation of culture and language among the Corded Ware Culture in Europe. Antiquity 91, 334–347 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lazaridis I., Reich D., Failure to replicate a genetic signal for sex bias in the steppe migration into central Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E3873–E3874 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.V. Heyd, in Ancestral landscapes: Burial mounds in the Copper and Bronze Ages (Central and Eastern Europe-Balkans-Adriatic-Aegean, 4th-2nd millennium B.C.): Proceedings of the International Conference held in Udine, May 15th–18th 2008, E. Borgna, S. Müller Celka, Eds. (Maison de l’Orient et de la Méditerranée, Lyon, 2011), Travaux de la Maison de l’Orient et de la Méditerranée, pp. 535–555. [Google Scholar]

- 46.A. Frînculeasa, The Children of the Steppe: Descendance as a key to Yamnaya success. Studii de Preistorie, 129–168 (2019).

- 47.Sjögren K.-G., Price T. D., Kristiansen K., Diet and mobility in the Corded Ware of Central Europe. PLOS ONE 11, e0155083 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sjögren K.-G., Olalde I., Carver S., Allentoft M. E., Knowles T., Kroonen G., Pike A. W. G., Schröter P., Brown K. A., Brown K. R., Harrison R. J., Bertemes F., Reich D., Kristiansen K., Heyd V., Kinship and social organization in Copper Age Europe. A cross-disciplinary analysis of archaeology, DNA, isotopes, and anthropology from two Bell Beaker cemeteries. PLOS ONE 15, e0241278 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.I. Pavlů, M. Zápotocká, The Prehistory of Bohemia 2. The Neolithic (Archeologický ústav AV ČR, Praha, v. v. i., Praha, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 50.E. Neustupný, M. Dobeš, J. Turek, M. Zápotocký, The Prehistory of Bohemia 3. The Eneolithic (Archeologický ústav AV ČR, Praha, v. v. i., Praha, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 51.E. Neustupný, K počátkům patriarchátu ve střední Evropě – The Beginnings of Patriarchy in Central Europe (Academia, Prague, 1967), vol. 77/2 of Rozpravy Československé akademie věd. Řada společenských věd. [Google Scholar]

- 52.E. Neustupný, in Die Kupferzeit als Historische Epoche: Symposium Saarbrücken und Otzenhausen 6.-13.11.1988., J. Lichardus, R. Echt, Eds. (Habelt, Bonn, 1991), Saarbrücker Beiträge zur Altertumskunde, pp. 747–752. [Google Scholar]

- 53.A. Sherratt, in Pattern of the Past: Studies in Honour of David Clarke, I. Hodder, D. L. Clarke, N. Hammond, Eds. (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1981), pp. 261–305. [Google Scholar]

- 54.V. Heyd, in Transitional landscapes?: The 3rd millennium BC in Europe : Proceedings of the International Workshop “Socio-Environmental Dynamics over the last 12,000 Years: The Creation of Landscapes III (15th–18th April 2013)” in Kiel, M. Furholt, R. Großmann, M. Szmyt, Eds. (Verlag Dr. Rudolf Habelt, Bonn, 2016), Universitätsforschungen zur prähistorischen Archäologie, pp. 53–84. [Google Scholar]

- 55.M. Zápotocký, in The Prehistoty of Bohemia 3. The Eneolithic, E. Neustupný, Ed. (Archeologický ústav AV ČR, Praha, v. v. i., Praha, 2013), pp. 64–86. [Google Scholar]

- 56.M. Dobeš, in The Prehistory of Bohemia 3. The Eneolithic, E. Neustupný, Ed. (Archeologický ústav AV ČR, Praha, v. v. i., Praha, 2013), pp. 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buchvaldek M., Corded pottery complex in central Europe. J. Indo Eur. Stud. 8, 393–406 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 58.J. Turek, in The Prehistory of Bohemia 3. The Eneolithic, E. Neustupný, Ed. (Archeologický ústav AV ČR, Praha, v. v. i., Praha, 2013), pp. 154–178. [Google Scholar]

- 59.L. Jiráň, O. Chvojka, E. Čujanová-Jílková, J. Hrala, J. Hůrková, D. Koutecký, J. Michálek, V. Moucha, I. Pleinerová, Z. Smrž, V. Vokolek, The Prehistory of Bohemia 4. The Bronze Age (Archeologický ústav AV ČR, Praha, v. v. i., Praha, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 60.M. Ernée, M. Langová, L. Arppe, P. Bednář, D. Berger, G. Brügmann, J. Bíšková, J. Cvrček, S. Drtikolová Kaupová, F. V. F. Jan, V. Heyd, L. Horáčková, L. Kaňáková, J. Kmošek, P. Kočár, R. Kočárová, Š. Křížová, L. Kučera, R. Kyselý, M. Mihaljevič, K. Moravcová, E. Pernicka, P. Stránská, R. Sedláček, J. Šura, J. Švédová, L. Vargová, P. Velemínský, K. Vymazalová, E. Zazvonilová, Mikulovice. Pohřebiště starší doby bronzové na Jantarové stezce - Mikulovice. Early Bronze Age Cemetery on the Amber Road (Archeologický ústav Akademie věd České republiky, Praha, v. v. i., Praha, 2020), vol. 21 of Památky archeologické, Supplementum. [Google Scholar]