Um agrupamento de casos de pneumonia foi registrado pela primeira vez em Wuhan, Hubei, China, em dezembro de 2019.1 Foi estabelecido que um coronavírus era o patógeno responsável pela doença e, desde então, é chamado de Coronavírus da Síndrome Respiratória Aguda Grave 2 (SARS-CoV-2). A doença desencadeada pela SARS-CoV-2 é chamada COVID-19, que se espalhou pelo mundo desde então. Os números tendem a subir na Europa e a extensão da letalidade da COVID-19 não pode ser medida corretamente. Em pacientes idosos, a letalidade parece ser particularmente maior quando comparada à influenza sazonal.2 A TC é muito útil no diagnóstico da COVID-19.3Além disso, o exame de ecocardiografia transtorácica (ETT) é uma ferramenta muito importante para avaliar a fração de ejeção do ventrículo esquerdo (FEVE). Estudos anteriores relataram que a reação em cadeia da polimerase em tempo real (RT-PCR) era o atual padrão ouro para o diagnóstico de COVID-19.3 Mas, em alguns casos, a sensibilidade da TC é maior que a da RT-PCR.4 Relatamos um caso confirmado de pneumonia por COVID-19 em uma mulher de 59 anos. Encontramos uma diminuição leve da FEVE sem elevação dos níveis da troponina-I, que pode ser considerada como miocardiopatia devido ao aumento da liberação de citocinas na COVID-19. Até onde sabemos, este é o primeiro relato da literatura que demonstra a associação entre imagens de ETT e TC na COVID-19, e descobrimos que a piora nos achados da ETT está alinhada com a progressão das imagens na TC.

Relato de Caso

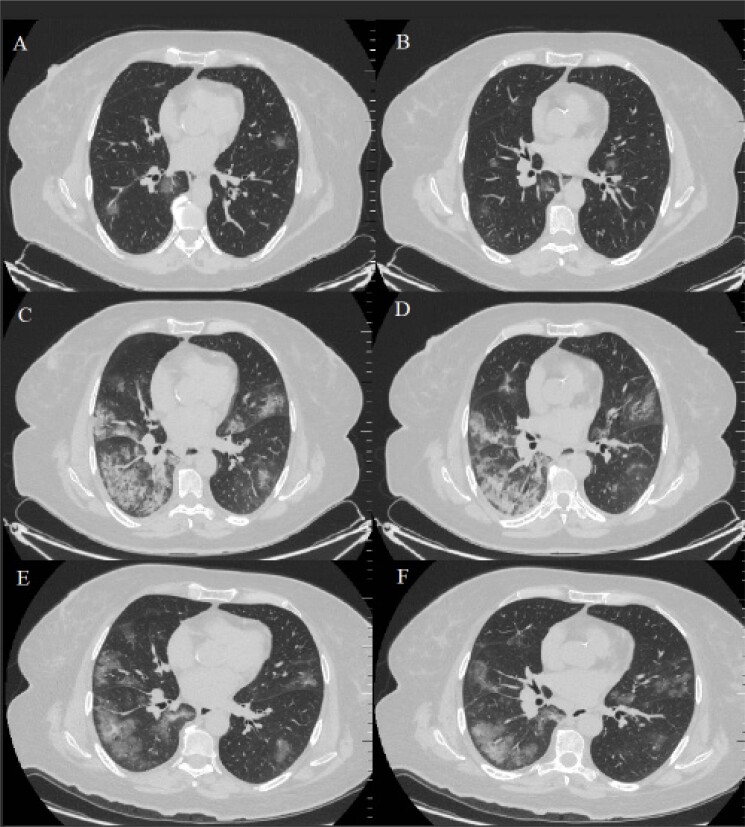

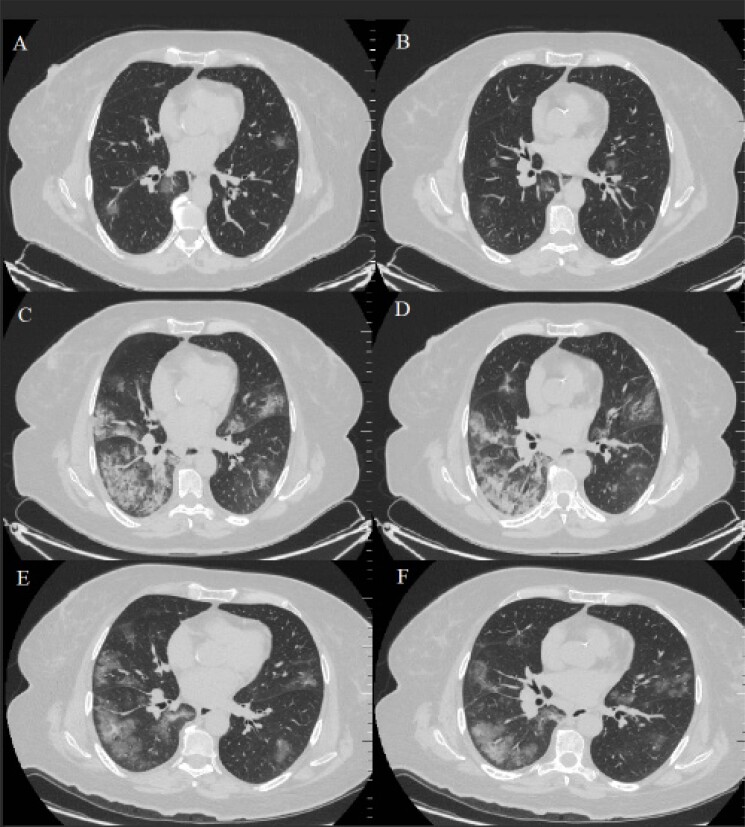

Uma mulher de 59 anos teve febre por 4 dias, depois de pegar um resfriado. Um dia antes de visitar o hospital, ela estava com febre e tosse, mas sem sensação de aperto no peito, dor no tórax, calafrios, náusea e vômito ou diarreia. Ela não se sentiu melhor depois de receber antitérmicos. Então, ela foi internada em nosso ambulatório no BHT Clinic Tema Hospital. Quatro dias antes, a paciente havia tido contato com um parente que havia viajado pela Europa. Em seu histórico médico anterior, cirurgia bariátrica havia sido realizada três anos antes e ela ainda apresentava diabetes mellitus tipo II, hiperlipidemia e hipertensão como condições pré-existentes. Ela foi internada em nosso hospital em 20 de março de 2020 e ainda apresentava febre após a internação, com a temperatura mais alta de 39,5 °C, frequência cardíaca de 119 batimentos por minuto; a eletrocardiografia foi consistente com taquicardia sinusal e o QTc foi calculado em 0,398 segundos, pressão arterial em 94/60 mmHg e taquipneia conspícua com frequência respiratória de 24 incursões respiratórias/min com oxigenação suficiente (95% de saturação em ar ambiente). A identificação do novo coronavírus em 2019 (2019-nCoV) na RT-PCR foi positiva em uma amostra obtida com um swab de garganta. O risco de contaminação simultânea com outros vírus respiratórios e outros patógenos foi negativo para a amostra obtida do swab de garganta. As características tomográficas da paciente foram semelhantes às séries de casos relatadas por Pan et al.,5 (Figura 1: A-B). Os resultados laboratoriais mostraram leucopenia, com 4,1 × 109/L, linfopenia com 0,8 × 109 / L, nível apenas ligeiramente aumentado de PCR, com 18,4 mg / L e baixo nível de procalcitonina, com 0,01 ng / mL. A paciente foi submetida a um exame de ETT com transdutor de 3,5 MHz (Vivid-7 GE Medical System, Horten, Noruega). Os exames e medidas foram realizados de acordo com as recomendações da American Echocardiography Unit. O método de Simpson foi utilizado para calcular a FEVE.6 Na admissão, a FEVE foi calculada em 65%, com achados normais de ETT.

Figura 1. – Imagens axiais de TC. (A-B): Na hospitalização, a TC mostra a presença bilateral de GGO leve no parênquima. (C-D): No dia 6, uma TC de repetição foi consistente com a crescente expansão dos GGOs e com as consolidações em andamento, chamadas de “pavimentação em mosaico”. (E-F): No dia 12, uma TC de repetição mostrou que as consolidações anteriores e GGOs em ambos os pulmões tinham sido absorvidos em sua maioria, deixando lesões fibrosas que podem indicar pneumonia residual em organização. TC: tomografia computadorizada, GGOs: opacidades em vidro fosco.

A paciente foi isolada e iniciou terapia de alto fluxo nasal para insuficiência respiratória e tratada com medicamento antiviral (oseltamivir, 75mg / cápsula, 1 cápsula por vez, duas vezes ao dia, por 5 dias), antibiótico (azitromicina, 500mg / comprimido) no primeiro dia e depois 250mg / comprimido, uma vez ao dia por 4 dias), antipirético (paracetamol 1gr / 100 mL, duas vezes ao dia), mucolítico (ampola de N-acetilcisteína, 300mg / 3mL intravenosa (IV), duas vezes por dia), anticoagulante (enoxaparina 4000 anti-Xa UI / 0,4 mL, uma vez ao dia), corticosteroide (metilprednisolona, 40mg intravenosa (IV), uma vez ao dia, por 5 dias), inibidor da bomba de prótons (ampola de esomeprazol, 40 mg IV, uma vez ao dia) e medicamento antimalárico (sulfato de hidroxicloroquina 200 mg / comprimido, 400 mg / comprimido duas vezes ao dia no primeiro dia e depois 200mg / comprimido duas vezes ao dia, por 6 dias).

Após 5 dias de tratamento, a temperatura da paciente voltou ao normal e os sintomas desapareceram. No entanto, no dia 6, uma TC de repetição mostrou-se consistente com o aumento da expansão dos GGOs e progrediu para as chamadas consolidações de “pavimentação em mosaico”. (Figura 1: C-D). Além disso, a FEVE foi calculada em 52%, mas o nível de troponina-I ainda era normal. Devido aos resultados da TC e aos achados da ETT, adicionamos favipiravir ao tratamento (200 mg / comprimido no primeiro dia, 1600 mg / comprimido duas vezes ao dia e 600 mg / comprimido duas vezes ao dia por 4 dias) em vez do oseltamivir. No 12º dia, uma TC de repetição mostrou que as consolidações anteriores e GGOs em ambos os pulmões tinham sido absorvidos em sua maioria, deixando algumas lesões fibrosas que podem indicar pneumonia residual em organização (Figura 1: E-F). Além disso, a FEVE foi calculada em 65% e a repetição da RT-PCR foi negativa e a paciente recebeu alta. Nenhum outro exame tomográfico de acompanhamento foi realizado.

A infecção é transmitida principalmente através de gotículas respiratórias. Febre e tosse seca são os principais sinais clínicos da COVID-19 em pacientes, acompanhados de dores no corpo ou exaustão, e a maioria dos pacientes tinha entre 40 e 60 anos de idade. Além disso, em alguns casos, podem ocorrer dor de cabeça, hemoptise e diarreia. Além do mais, pacientes graves podem evoluir para SDRA e a intubação pode ser necessária em alguns pacientes.1 Os sinais clínicos da COVID-19 são os mesmos de infecções normais do trato respiratório superior, mas a TC do tórax mostra alguns detalhes.5 Entretanto, é difícil distinguir o COVID-19 de outras pneumonias virais com base apenas nos achados da TC. Ainda é necessário esclarecer e definir a história epidemiológica e ela deve ser diagnosticada por RT-PCR. Miocardite aguda é um risco documentado de infecções virais, tais como a influenza. A apresentação clínica varia de miocardite assintomática a fulminante, o que pode contribuir para instabilidade hemodinâmica grave.7 Estudos anteriores baseados nas autópsias em casos fatais mostraram que, durante a pandemia de influenza asiática de 1957 e durante a pandemia de influenza espanhola, foram registradas, respectivamente, 39,4% e 48% de taxas de complicações com miocardite focal a difusa.8 Esses incidentes mortais de miocardite mostraram pneumonia grave e envolvimento de múltiplos órgãos. Como consequência, espera-se que a miocardite seja um risco fatal em um surto pandêmico de influenza. Miura et al.,9 também encontraram um antígeno viral no miocárdio com coloração imuno-histoquímica do coração autopsiado.9 Bowles et al.,10 avaliaram amostras de biópsia endomiocárdica de 624 pacientes e identificaram objetivamente miocardite utilizando PCR para diferentes genes virais. Das 239 amostras positivas para genes virais, o adenovírus foi encontrado em 142 amostras, o enterovírus em 85 amostras e o influenza tipo A em apenas cinco (0,8%) amostras.10Portanto, embora a patogênese da miocardiopatia ou miocardite associada à COVID-19 permaneça incerta, a literatura sugere que a disfunção endotelial pode ter um papel importante na patogênese da miocardite e da miocardiopatia. Os achados de análises por microscópico eletrônico do coração a partir de um modelo murino de miocardite por influenza mostraram muitos linfócitos infiltrantes diretamente ligados aos miócitos cardíacos e citocinas pró-inflamatórias na patogênese da miocardite aguda.7-9 A liberação excessiva de citocinas na COVID-19 já é um fato conhecido.1-2

Nossa hipótese é de que citocinas como TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, e IL-10, que são conhecidas por terem efeitos cardio-depressivos, e catecolaminas endógenas e exógenas, que desempenham papel importante na sepse, possam também desencadeiam o efeito cardio-depressivo na COVID-19. Além disso, consideramos que a miocardiopatia pode ser reversível ao remover-se as citocinas da circulação durante a recuperação. Estudos anteriores também demonstraram que a inibição da replicação viral mediada por tripsina e a downregulação de citocinas e metaloproteinases da matriz melhoraram significativamente as funções cardíacas de camundongos infectados pelo vírus da influenza A.7-9De acordo com esses achados, temos que identificar prontamente pacientes críticos e tratá-los o mais rápido possível, para evitar complicações fatais. Precisamos utilizar todos os tipos de ferramentas diagnósticas e opções de tratamento durante o seguimento. De maneira especial, a ETT pode ser a maneira menos dispendiosa e mais fácil de acompanhar esses pacientes. Entretanto, ainda não existe medicamento específico para o tratamento de pacientes com COVID-19. Com base na experiência do tratamento da SARS (Síndrome Respiratória Aguda Severa) e MERS (Síndrome Respiratória do Oriente Médio), alguns medicamentos como hidroxicloroquina, azitromicina, oseltamivir, lopinavir-ritonavir, remdesivir e favipiravir podem ter efeitos positivos em pacientes com COVID-19.1

Em conclusão, nossa paciente não apresentou miocardite, pois não houve aumento da troponina-I, mas acreditamos que ela possa sofrer miocardiopatia devido à liberação excessiva de citocinas. No nosso caso, a miocardiopatia e a COVID-19 foram tratadas com hidroxicloroquina, metilprednisolona, azitromicina e, finalmente, com favipiravir. No entanto, os efeitos curativos desses medicamentos ainda não foram comprovados e precisam de pesquisas adicionais.

Vinculação acadêmica

Não há vinculação deste estudo a programas de pós-graduação.

Aprovação ética e consentimento informado

Este artigo não contém estudos com humanos ou animais realizados por nenhum dos autores.

Fontes de financiamento

O presente estudo não teve fontes de financiamento externas.

Referências

- 1.1. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020 Feb 20;382(8):727-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.2. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.3. Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, Zhan C, Chen C, Lv W, et al. Correlation of Chest CT and RT-PCR Testing in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: A Report of 1014 Cases. Radiology. 2020 Feb 26:200642. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.4. Fang Y, Zhang H, Xie J, Lin M, Ying L, Pang P, et al. Sensitivity of Chest CT for COVID-19: Comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology. 2020 Feb 19:200432. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200432. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.5. Pan Y, Guan H, Zhou S, Wang Y, Li Q, Zhu T, et al. Initial CT findings and temporal changes in patients with the novel coronavirus pneumonia (2019-nCoV): a study of 63 patients in Wuhan, China. Eur Radiol. 2020 Feb 13. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06731-x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.6. Acquatella H, Asch FM, Barbosa MM, Barros M, Bern C, Cavalcante JL, et al. Recommendations for Multimodality Cardiac Imaging in Patients with Chagas Disease: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography in Collaboration With the InterAmerican Association of Echocardiography (ECOSIAC) and the Cardiovascular Imaging Department of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology (DIC-SBC). J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2018 Jan;31(1):3-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.7. Ukimura A, Satomi H, Ooi Y, Kanzaki Y. Myocarditis Associated with Influenza A H1N1pdm2009. Influenza Res Treat. 2012;2012:351979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.8. Mamas MA, Fraser D, Neyses L. Cardiovascular manifestations associated with influenza virus infection. Int j Cardiol. 2008;130(3):304–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.9. Miura M, Asaumi Y, Wada Y, Ogata K, Sato T, Sugawara T, et al. A case of influenza subtype A virus-induced fulminant myocarditis: an experience of percutaneous cardio-pulmonary support (PCPS) treatment and immunohistochemical analysis. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2001;195(1):11–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.10. Bowles NE, Ni J, Kearney DL, Pauschinger M, Schultheiss HP, McCarthy R, et al. Detection of viruses in myocardial tissues by polymerase chain reaction: evidence of adenovirus as a common cause of myocarditis in children and adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(3):466–72. [DOI] [PubMed]