Abstract

Centromere proteins (CENPs) are the main constituent proteins of kinetochore, which are essential for cell division. In recent years, several studies have revealed that several CENPs were aberrantly expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, numerous centromere proteins have not been studied in HCC. In this study, we used databases of Oncomine, Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA), the Kaplan-Meier Plotter, cBioPortal, the Human Protein Atlas (HPA), and TIMER (Tumor Immune Estimation Resource) and immunohistochemical staining of clinical specimens to investigate the expression of 15 major centromere proteins in HCC to evaluate their potential prognostic value. We found that the mRNA levels of 4 out of 15 centromere proteins (CENPL, CENPQ, CENPR, and CENPU) were significantly higher in HCC than in normal tissues, and their mRNA levels were associated with the tumor stages (p values < 0.01). Patients with higher mRNA levels of CENPL had poorer overall survival, progression-free survival, relapse-free survival, and disease-specific survival (p values < 0.05). Furthermore, the higher levels of CENPL mRNA were associated with worse overall survival in males without hepatitis virus infection (p values < 0.05). The protein expression level of CENPL in human HCC tissue was higher than that in normal liver tissue. In addition, the expression of CENPL was positively correlated with the levels of the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. The results suggest that the high mRNA expression of CENPL may be a potential predictor of prognosis in HCC patients.

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fourth major cause of cancer-related death globally [1]. Patients with early-stage HCC are eligible to local ablation, surgical resection, or liver transplantation. Unfortunately, due to the lack of satisfactory biomarkers in diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis, morbidity and mortality continue to increase [2]. Therefore, it is necessary to explore novel diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic biomarkers for HCC.

The centromere proteins (CENPs) are assembled in repetitive noncoding DNA regions (centromere DNA). They are named in alphabetical order, according to the date of identification [3]. To date, more than 100 centromere proteins have been identified. These proteins are attached to chromosomes and spindle microtubules and are involved in precise regulation and guidance of chromosome separation during mitosis or meiosis [3, 4] A growing number of studies have revealed that several CENPs were abnormally expressed in lung, breast, ovarian, bladder, esophageal, and colorectal cancers and were correlated with the prognosis of patients [5–14].

Several members of CENPs have been reported to be involved in HCC. These studies showed that CENPA, CENPE, CENPF, CENPH, CENPK, and CENPW were all abnormally expressed in HCC and were associated with patient prognosis [15–29]. Current studies have suggested that these CENPs might play an important role in HCC, and many others remained unknown. With the advancement in bioinformatics, a variety of high-quality databases are available for discovering novel neoplastic factors [30–32]. Based on the public databases, 15 major CENPs, including CENPB, CENPC, CENPI, CENPJ, CENPL, CENPN, CENPO, CENPP, CENPQ, CENPR, CENPS, CENPT, CENPU, CENPV, and CENPX were analyzed by using bioinformatics tools and immunohistochemical staining to further investigate the gene expression patterns and prognostic value in HCC.

2. Methods

2.1. Oncomine Database Analysis

We used Oncomine (http://www.oncomine.org), an online cancer microarray database [33], to analyze the transcription levels of 15 CENPs in tumors and normal tissues from HCC and other cancers. Datasets of clinical tumor and normal control specimens were compared using Student's t-test. For all cancers and genes, the threshold was set as the p value of 0.0001 and the fold change of 2.

2.2. GEPIA Dataset Analysis

Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn) is a newly developed interactive web server for analyzing the RNA sequencing expression data from the TCGA and the GTEx through a variety of customizable functions [34]. It was used to analyze mRNA differential expression in HCC and liver tissues, as well as the correlation between expression levels and pathological stages. Differential threshold of ∣log2FC∣ was 1 and the p value cutoff of 0.01.

2.3. The Kaplan-Meier Plotter

The Kaplan-Meier Plotter (http://www.kmplot.com) database was used to explore the relationship between gene transcription and prognosis. The database contains the levels of CENP mRNAs and survival information including OS, progression-free survival (PFS), RFS, and disease-specific survival (DSS) under various clinical parameters of HCC patients (https://kmplot.com/analysis/index.php?P=service&cancer=liver_rnaseq) [35]. The patients were divided into two groups based on the median mRNA expression of CENPs. The p value of <0.05 is considered significantly different.

2.4. cBioPortal Database

cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/) is a comprehensive gene database, including different datasets such as DNA mutation, gene amplification, and methylation. This database was used to analyze and visualize possible gene mutation and copy number alterations of CENPs.

2.5. TIMER

TIMER (Tumor Immune Estimation Resource) is a web server for comprehensive analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/). The relationships between the expression levels of potential CENPs and 6 immune infiltrates (B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells) were estimated by the TIMER algorithm in HCC. Moreover, the correlation of tumor purity and CENP gene expression was also analyzed. p < 0.05 is considered as significant.

2.6. The Human Protein Atlas

The Human Protein Atlas (HPA) is a Swedish-based program initiated in 2003, which is aimed at mapping all the human proteins in cells, tissues, and organs using an integration of various omics technologies, including antibody-based imaging, mass spectrometry-based proteomics, transcriptomics, and systems biology (https://www.proteinatlas.org/). The Human Pathology Atlas is based on a systems-based analysis of the transcriptome of 17 main cancer types using data from 8000 patients [36]. In this database, we verified the protein expression of CENPs with potential prognostic value in normal liver and HCC tissues.

2.7. Immunohistochemical Staining

Five μm sections were obtained from paraffin-embedded tumor and nontumor specimens from 28 patients with clinically diagnosed HCC. All these sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated in alcohol followed by wet autoclave pretreatment in citrate buffer for antigen retrieval (10 minutes at 120°C, pH = 6.0). Then, the sections were rinsed with phosphate buffer saline. Immunohistochemical staining for antibody to CENPL (rabbit: bs13836R, Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology, China) was performed using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method. The primary antibody was applied to the sections and allowed to react for 1 hour at room temperature. The sections were then incubated with biotinylated anti-mouse/rabbit antibody (1 : 200 dilution for CENPL) for 30 min and avidin-biotin-peroxidase reagent for 25 min. After color development with diaminobenzidine, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

3. Results

3.1. The Transcription Levels of 15 CENPs in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

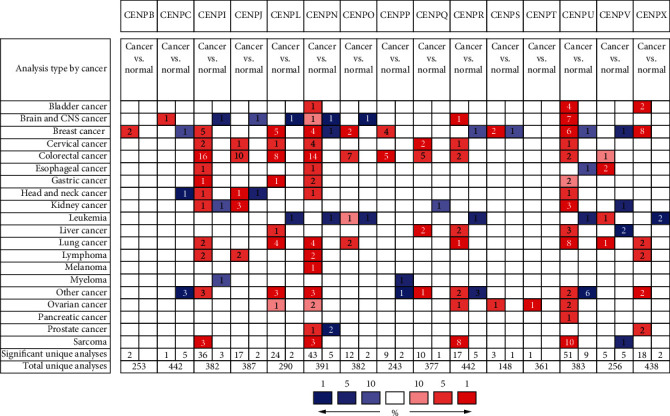

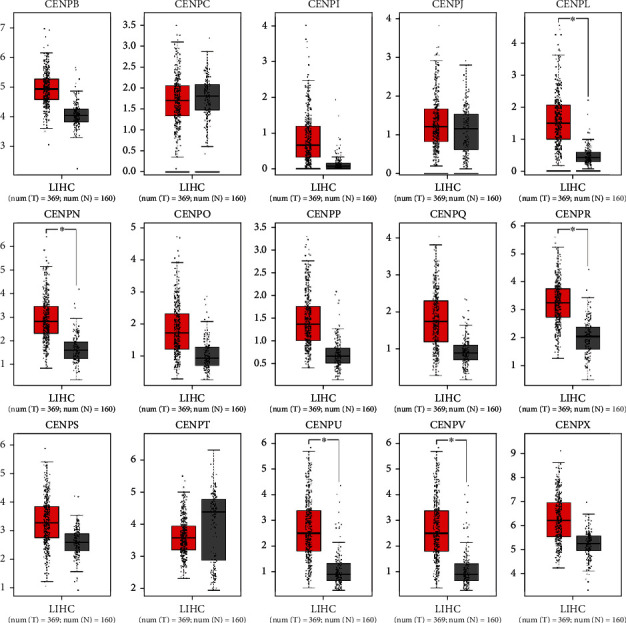

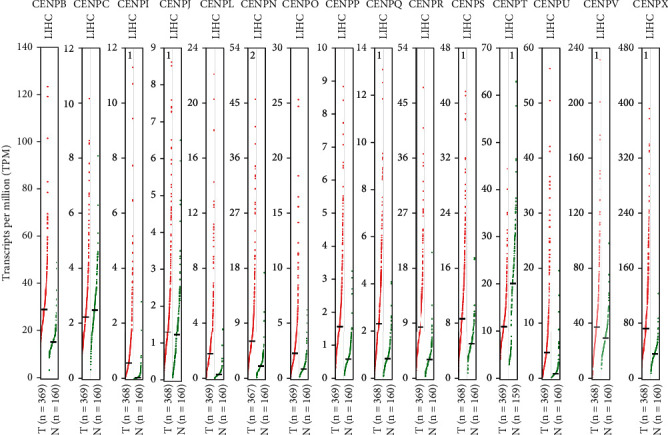

We investigated the mRNA levels of 15 CENPs in the tumor and normal tissues of HCC and other major cancers by using Oncomine database. We found that 4 out of 15 CENPs (CENPL, CENPQ, CENPR, and CENPU) were significantly overexpressed in HCC (Figure 1). Fold change ranged from 2.035 to 4.861 (Table 1). CENPV was underexpressed in two dysplasia datasets with fold change of -2.075 and -2.392 (Table 1). However, no significant change in 10 CENPs (CENPB, CENPC, CENPI, CENPJ, CENPN, CENPO, CENPP, CENPS, CENPT, and CENPX) were observed (Figure 1). These datasets were reported by Wurmbach et al. [37], Roessler et al. [38], and Chen et al. [39], respectively. The results of GEPIA showed that the mRNA levels of 12 CENPs (CENPB, CENPI, CENPL, CENPN, CENPO, CENPP, CENPQ, CENPR, CENPS, CENPU, CENPV, and CENPX) were significantly higher in the tumor than in the normal tissue (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

The transcription levels of CENP in different types of cancers. The mRNA levels of CENPL, CENPQ, CENPR, and CENPU were significantly higher in HCC than in normal tissues (p < 0.01) (Oncomine).

Table 1.

Significant changes in the expression of CENPs in HCC and normal tissues (Oncomine database).

| CENPs | Datasets | Fold change | p value | t-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CENPL | Wurmbach et al.'s liver statistics | 2.234 | 9.45E‐8 | 6.414 |

| CENPQ | Chen et al.'s liver statistics (adenoma) | 2.035 | 3.83E‐6 | 5.747 |

| Chen et al.'s liver statistics | 2.458 | 1.18E‐10 | 6.934 | |

| CENPR | Roessler et al.'s liver 2 statistics | 2.604 | 2.82E‐62 | 20.059 |

| Roessler et al.'s liver statistics | 2.235 | 4.44E‐6 | 5.455 | |

| CENPU | Roessler et al.'s liver 2 statistics | 4.019 | 2.46E‐66 | 22.356 |

| Chen et al.'s liver statistics | 2.344 | 5.94E‐15 | 8.583 | |

| Roessler et al.'s liver statistics | 4.861 | 1.01E‐8 | 7.825 | |

| CENPV | Wurmbach et al.'s liver statistics | -2.392 | 7.60E‐7 | -6.703 |

| Wurmbach et al.'s liver statistics | -2.075 | 4.18E‐6 | -6.889 |

Figure 2.

The expression of CENP mRNA levels in HCC. The transcript levels of CENPB, CENPI, CENPL, CENPN, CENPO, CENPP, CENPQ, CENPR, CENPS, CENPU, CENPV, and CENPX were significantly higher in the tumor than in the normal tissue (p < 0.01) (GEPIA, box plot).

Figure 3.

The expression of CENP mRNA levels in HCC. The transcript levels of CENPB, CENPI, CENPL, CENPN, CENPO, CENPP, CENPQ, CENPR, CENPS, CENPU, CENPV, and CENPX were significantly higher in the tumor than in the normal tissue (p < 0.01) (GEPIA, scatter diagram).

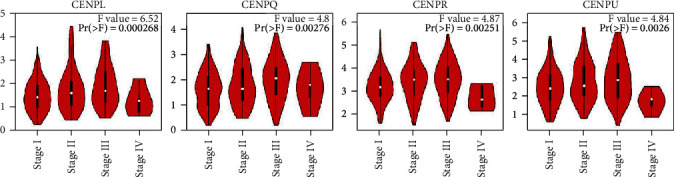

3.2. Relationship between the mRNA Levels of CENPs and Pathological Stages of HCC

Then, we selected 4 CENPs (CENPL, CENPQ, CENPR, and CENPU) with high expression in HCC as shown in both the Oncomine and GEPIA databases to further analyze the relationship between mRNA levels and tumor stages. The analysis showed that high mRNA levels of CENPL, CENPQ, CENPR, and CENPU were significantly correlated with tumor stages (p < 0.01) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Correlation between CENP mRNA levels and tumor stages in HCC patients. The mRNA levels of CENPL, CENPQ, CENPR, and CENPU were significantly correlated with tumor stages (p < 0.01). (GEPIA).

3.3. Correlation between the Increased mRNA Levels and the Prognosis of CENPs in Patients with HCC

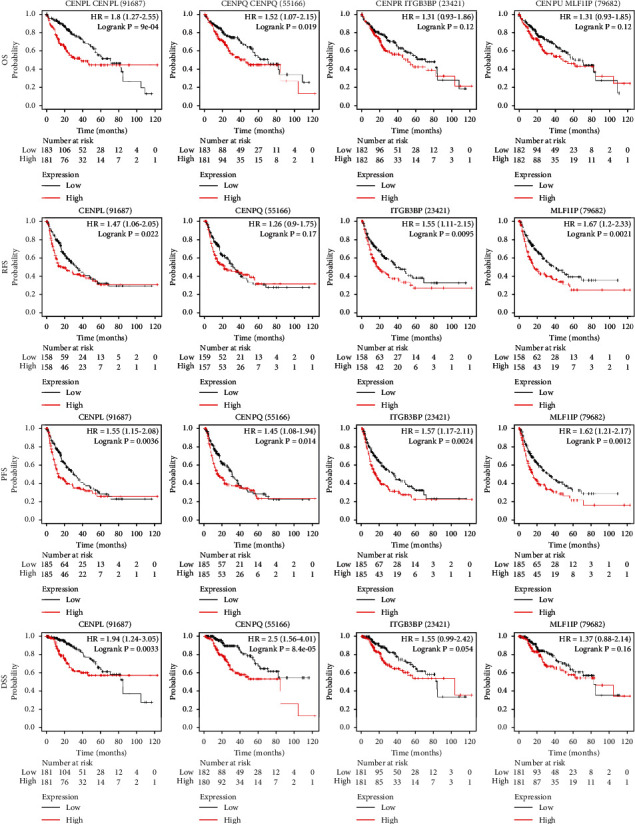

To evaluate the prognostic value of 4 CENPs (CENPL, CENPQ, CENPR, and CENPU) with high mRNA expression in HCC patients, we used the Kaplan-Meier Plotter to analyze their overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), relapse-free survival (RFS), and disease-specific survival (DSS). It was found that patients with higher mRNA levels of CENPL were associated with significantly poor OS, PFS, RFS, and DSS (p < 0.05) (Figure 5, Table 2). Patients with higher CENPQ mRNA expression had poorer OS, PFS, and DSS (p < 0.05), and patients with higher CENPR mRNA levels had poorer PFS and RFS (p < 0.05). Patients with increased CENPU mRNA levels had lower PFS and RFS (p < 0.05) (Figure 5, Table 2).

Figure 5.

Correlation between increased CENP mRNA level (CENPL, CENPQ, CENPR, and CENPU) and prognosis in patients with HCC. Patients with higher mRNA levels of CENPL had significantly poorer OS, PFS, RFS, and DSS (p < 0.05) (the Kaplan-Meier Plotter).

Table 2.

Correlationship between the mRNA expression of CENPs and patient's survival (the Kaplan-Meier Plotter).

| CENPs | Survival | Cases | HR | p value | Median survival | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L (months) | H (months) | |||||

| CENPL | OS | 364 | 1.8 | 0.0009 | 70.5 | 38.3 |

| RFS | 313 | 1.47 | 0.0218 | 34.4 | 21.2 | |

| PFS | 366 | 1.55 | 0.0036 | 29.77 | 13.13 | |

| DSS | 357 | 1.94 | 0.0033 | 49.67 | 20.9 | |

|

| ||||||

| CENPQ | OS | 364 | 1.52 | 0.0186 | 70.5 | 45.7 |

| RFS | 313 | 1.26 | 0.1722∗ | 30.4 | 21.23 | |

| PFS | 366 | 1.45 | 0.0136 | 29.77 | 13.83 | |

| DSS | 357 | 2.5 | 8.4E‐5 | 54.13 | 22 | |

|

| ||||||

| CENPR | OS | 364 | 1.31 | 0.1205∗ | 70.5 | 52 |

| RFS | 313 | 1.55 | 0.0095 | 37.67 | 17.9 | |

| PFS | 366 | 1.57 | 0.0024 | 36.1 | 15.07 | |

| DSS | 357 | 1.55 | 0.0538∗ | 84.4 | 104.17 | |

|

| ||||||

| CENPU | OS | 364 | 1.31 | 0.1243∗ | 70.5 | 49.7 |

| RFS | 313 | 1.67 | 0.0021 | 37.67 | 16.37 | |

| PFS | 366 | 1.62 | 0.0012 | 33 | 15.07 | |

| DSS | 357 | 1.37 | 0.161∗ | 81.87 | 84.73 | |

Note. L: low-expression cohort; H: high-expression cohort. “∗” means no significant statistical significance, p > 0.05.

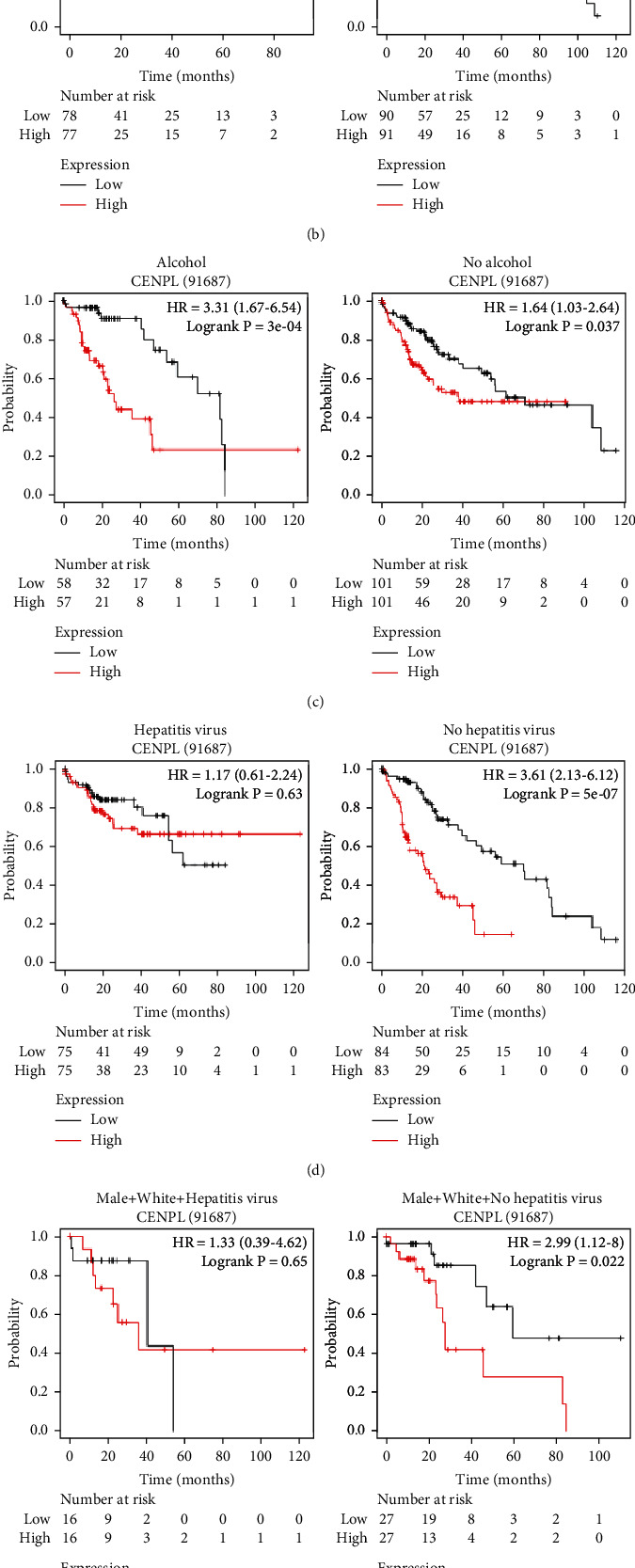

The level of CENPL mRNA showed a potential value in predicting the prognosis of patients with HCC. Therefore, we further explored the relationship between the mRNA expression of CENPL and the OS of patients in subgroups as divided by parameters including gender, race, alcohol consumption, and hepatitis virus infection. The results showed that males with high expression of CENPL mRNA had poorer OS (Figure 6(a), Table 3). Asians with higher mRNA levels of CENPL had worse OS (Figure 6(b), Table 3). Patients with higher CENPL expression had worse OS regardless of alcohol consumption (Figure 6(c), Table 3). Among patients without hepatitis virus infection, patients with higher expression of CENPL had poorer OS (Figure 6(d), Table 3). Furthermore, we found that higher levels of CENPL mRNA were associated with worse OS in white and Asian male patients without hepatitis virus infection (Figures 6(e) and 6(f), Table 3).

Figure 6.

Correlationship between increased CENPL mRNA levels and patients' OS with various clinical parameters. Males with higher mRNA level of CENPL had significantly poorer OS (a). Asians with higher mRNA levels of CENPL had worse OS (b). Patients with higher CENPL mRNA level had poorer OS regardless of alcohol consumption (c). Patients without hepatitis virus infection had poorer OS with high expression of CENPL (d). Among male patients without hepatitis virus infection, white and Asian patients with higher CENPL mRNA level had poorer OS (e, f) (the Kaplan-Meier Plotter).

Table 3.

The relationship between the mRNA expression of CENPL and patients' OS with various clinical parameters (the Kaplan-Meier Plotter).

| Gender | Race | Risk factors (yes/no) | Cases | HR | p value | Median survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/female | White/Asian | Alcohol consumption | Hepatitis virus | L (months) | H (months) | |||

| Both | All | Both | Both | 364 | 1.8 | 0.0009 | 70.5 | 38.3 |

| Male | All | Both | Both | 246 | 2.17 | 0.0007 | 82.9 | 36.3 |

| Female | All | Both | Both | 118 | 1.02 | 0.9349∗ | 52 | 46.6 |

| Both | White | Both | Both | 181 | 1.55 | 0.0599∗ | 54.1 | 31 |

| Both | Asian | Both | Both | 155 | 3.36 | 0.0002 | 56.2 | 9.9 |

| Both | All | Yes | Both | 115 | 3.31 | 0.0003 | 81.9 | 26.7 |

| Both | All | No | Both | 202 | 1.64 | 0.0367 | 71 | 38.3 |

| Both | All | Both | Both | 150 | 1.17 | 0.632∗ | 54.1 | 23.1 |

| Both | All | Both | No | 167 | 3.61 | 5.0E‐7 | 70.5 | 22 |

| Male | White | Both | Both | 102 | 2.28 | 0.0174 | 54.1 | 27.9 |

| Male | Asian | Both | Both | 122 | 3.72 | 0.0003 | 56.2 | 9.3 |

| Male | White | Both | Yes | 32 | 1.33 | 0.6475∗ | 41 | 36.3 |

| Male | White | Both | No | 54 | 2.99 | 0.0224 | 59.7 | 27.9 |

| Male | Asian | Both | Yes | 77 | 1.37 | 0.5562∗ | NA | NA |

| Male | Asian | Both | No | 37 | 3.97 | 0.0098 | 17.8 | 5.7 |

Note. L: low-expression cohort; H: high-expression cohort. “∗” means no significant statistical significance, p > 0.05.

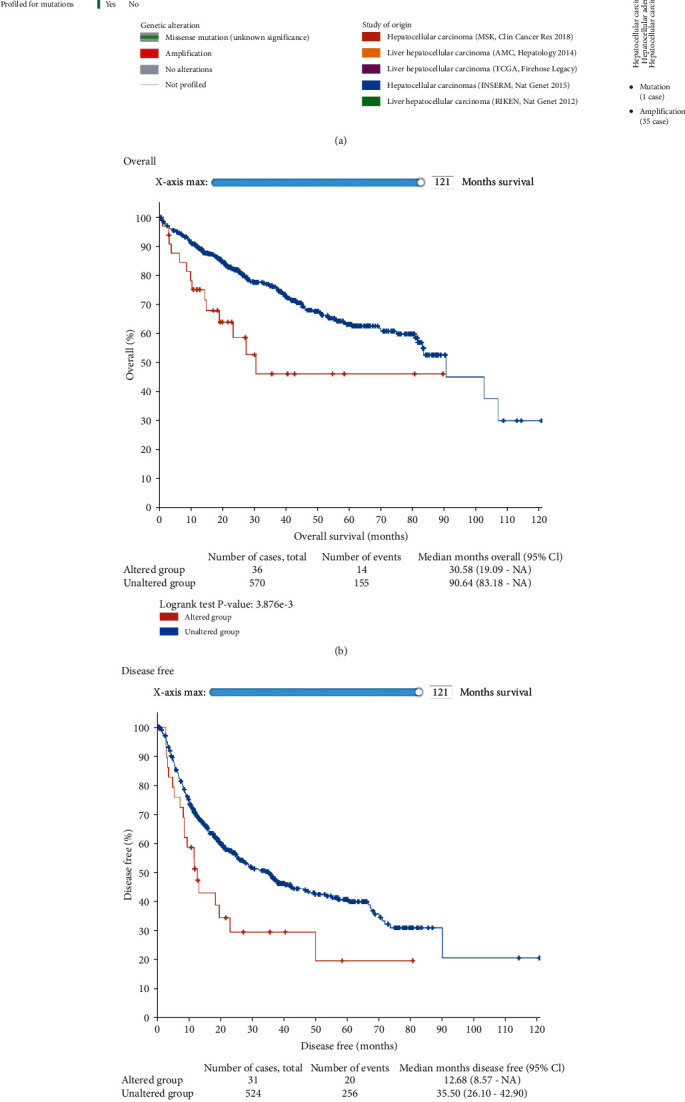

3.4. Mutations and Copy Number Alterations of CENPL in HCC

We used the cBioPortal database to investigate the mutations and copy number alterations of CENPL. Gene alterations occurred in 4% of the patients in the 5 datasets (Figure 7(a)). There was a significant correlation between the gene variation and patients' OS and disease-free survival (p < 0.05) (Figures 7(b) and 7(c)).

Figure 7.

Mutation analysis of CENPL gene in HCC patients. Amplification was the most significant variation in 4% of the queried patients, and the study searched from 5 datasets (a). The gene variation was significantly associated with patient's OS and disease-free survival (p < 0.05) (b, c) (cBioPortal).

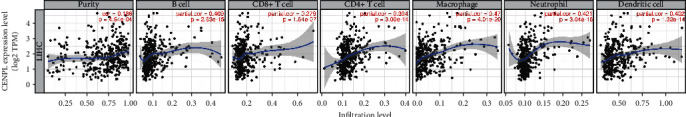

3.5. Relationship between the Expression of CENPL and Immune Cells in HCC

To further understand the relationship between CENPL mRNA level and immune infiltration cells in an HCC microenvironment, we used TIMER to evaluate immune cell infiltration data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). The results illuminated that the expression of CENPL was positively correlated with infiltrating levels of B cell, CD4+ T cell, CD8+ T cell, neutrophil, macrophage, and dendritic cell in HCC, respectively (p < 0.01) (Figure 8). Similarly, the expression of the CENPL gene was positively associated with the tumor purity (p < 0.05) (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Relationship between the expression of CENPL and the abundance of immune cells in HCC. The expression of CENPL had positive correlations with tumor purity and significant positive correlations with infiltrating levels of B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells in HCC, respectively (TIMER).

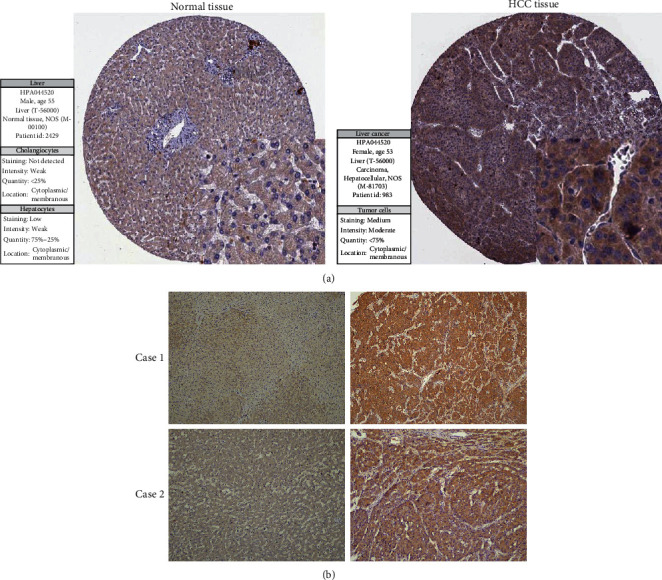

3.6. The Expression of CENPL Protein in Tumor and Normal Tissues of HCC Patients

In order to learn the expression of CENPL protein in HCC specimens, we firstly studied it in the HPA database. The immunohistochemical staining results indicated that the expression of CENPL protein was significantly higher in HCC tissues than in normal liver tissues, and the protein staining intensity score was modest in HCC tissues and low in normal liver tissues (Figure 9(a)). The CENPL protein was mainly localized in the cytoplasm and membrane (Figure 9). Our further clinical specimens confirmed similar results. In 28 clinical specimens, the expression level of CENPL protein was higher in HCC tissues (16/28) than in noncancer tissues (12/28) (Figure 9(b)).

Figure 9.

The expression of CENPL protein in tumor and normal tissues. Immunohistochemical staining showed that the expression of CENPL protein in HCC tissues was significantly higher than that in normal liver tissues. The CENPL protein was mainly localized in the cytoplasm and membrane (a) (HPA). In clinical specimens, the expression of CENPL protein in HCC tissues was significantly higher than that in adjacent tissues (b).

4. Discussion

In this study, the transcriptions of 15 CENPs in HCC were investigated by using the Oncomine and GEPIA databases. Results showed that the mRNA levels of CENPL, CENPQ, CENPR, and CENPU in HCC tissues were significantly higher compared with those in normal tissues. Their mRNA levels were significantly correlated with the pathological stages of HCC. Patients with higher mRNA levels of CENPL had poorer OS, PFS, RFS, and DSS. Then, the prognostic value of CENPL was further studied under different clinical parameters. We found that higher levels of CENPL mRNA were associated with poorer OS in white and Asian male patients without hepatitis virus infection. Mutation analysis showed that CENPL was rarely mutated, suggesting that the pathophysiological role of CENPL in HCC was not mediated by gene mutation. In addition, we found that the expression of CENPL was positively correlated with infiltrating levels of B cell, CD4+ T cell, CD8+ T cell, neutrophil, macrophage, and dendritic cell in HCC. Finally, HPA data and immunohistochemical staining of our clinical specimens showed that CENPL was overexpressed in HCC tissues.

CENPs play an important physiological role in the cell cycle, and their expression levels are strictly regulated; therefore, no pathological effect was shown. However, many CENPs with an abnormal expression were found in tumor cells. To date, it is not clear whether this result is an initiating factor or a result of tumor development. On the one hand, the abnormal expression of CENPs may interact with other genes and contribute to tumorigenisis. For example, Xiao et al. found that CENPM may be involved in the P53 pathway in HCC [40]. On the other hand, chromosomal and genetic instability are now recognized as the important cause of cancer, and the abnormal expression of CENPs is likely to play important roles through this mechanism [5, 41–43]. These results illustrate the complex mechanism between CENPs and HCC. Furthermore, the expression of CENPs in patients with cirrhosis has not been reported, which may help to reveal the mechanism of CENPs and HCC. CENPL is a subunit of the CENPH-CENPI-associated centromeric complex that targets CENPA to centromeres and is required for proper kinetochore function and mitotic progression [44]. Diseases associated with CENPL include the chromosome 22Q11.2 deletion syndrome and chromosome 17p13.3 duplication syndrome (GeneCards: https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=CENPL&keywords=cenpl). To date, no studies of CENPL in tumors have been reported. In this study, we found that CENPL was overexpressed in HCC, and the mRNA level was closely related to various clinicopathological parameters of patients. These results suggest that CENPL may play an important role in HCC and that CENPL is a potential target for future immunotherapy and a prognostic predictor. However, there are several limitations to this study. We have not yet verified the association between CENPL and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in human or mouse specimens. The effects of CENPL on the proliferation, apoptosis, and metastasis of HCC cells have not been further studied. Therefore, in-depth studies are needed in the future.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that CENPL mRNA may be a potential prognostic biomarker of HCC patients.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the many generous data contributors and the many public database providers. This study was supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Joint Fund Project of Fujian Province (2019Y9044), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (grant number 2020J011131), and the Outstanding Youth Training Project (2018Q07).

Contributor Information

Dongliang Li, Email: dongliangli93@163.com.

Zhixian Wu, Email: zxwu@xmu.edu.cn.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from Oncomine (http://www.oncomine.org), GEPIA (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn), the Kaplan-Meier Plotter (http://www.kmplot.com), cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org), TIMER (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/), and HPA (https://www.proteinatlas.org/).

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have declared that they have no competing interests and have confirmed its accuracy.

Authors' Contributions

Zhongyuan Cui and Lijia Xiao contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Villanueva A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. The New England Journal of Medicine . 2019;380(15):1450–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1713263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang J. D., Hainaut P., Gores G. J., Amadou A., Plymoth A., Roberts L. R. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology . 2019;16(10):589–604. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0186-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Earnshaw W. C. Discovering centromere proteins: from cold white hands to the A, B, C of CENPs. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology . 2015;16(7):443–449. doi: 10.1038/nrm4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKinley K. L., Cheeseman I. M. The molecular basis for centromere identity and function. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology . 2016;17(1):16–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang W., Mao J. H., Zhu W., et al. Centromere and kinetochore gene misexpression predicts cancer patient survival and response to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Nature Communications . 2016;7(1, article 12619) doi: 10.1038/ncomms12619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu X., Luo X., Feng G., et al. CENPE expression is associated with its DNA methylation status in esophageal adenocarcinoma and independently predicts unfavorable overall survival. PLoS One . 2019;14(2, article e0207341) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shan L., Zhao M., Lu Y., et al. CENPE promotes lung adenocarcinoma proliferation and is directly regulated by FOXM1. International Journal of Oncology . 2019;55(1):257–266. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2019.4805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X., Chen D., Gao J., et al. Centromere protein U expression promotes non-small-cell lung cancer cell proliferation through FOXM1 and predicts poor survival. Cancer Management and Research . 2018;Volume 10:6971–6984. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S182852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin S. Y., Lv Y. B., Mao G. X., Chen X. J., Peng F. The effect of centromere protein U silencing by lentiviral mediated RNA interference on the proliferation and apoptosis of breast cancer. Oncology Letters . 2018;16(5):6721–6728. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H., Zhang H., Wang Y. Centromere protein U facilitates metastasis of ovarian cancer cells by targeting high mobility group box 2 expression. American Journal of Cancer Research . 2018;8(5):835–851. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim W. T., Seo S. P., Byun Y. J., et al. The anticancer effects of garlic extracts on bladder cancer compared to cisplatin: a common mechanism of action via centromere protein M. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine . 2018;46(3):689–705. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X18500362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding N., Li R., Shi W., He C. CENPI is overexpressed in colorectal cancer and regulates cell migration and invasion. Gene . 2018;674:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu W., Wu F., Wang Z., et al. CENPH inhibits rapamycin sensitivity by regulating GOLPH3-dependent mTOR signaling pathway in colorectal cancer. Journal of Cancer . 2017;8(12):2163–2172. doi: 10.7150/jca.19940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S., Liu B., Zhang J., et al. Centromere protein U is a potential target for gene therapy of human bladder cancer. Oncology Reports . 2017;38(2):735–744. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu L., Li Y., Zhang S., Yu D., Zhu M. Hepatitis B virus X protein mutant upregulates CENP-A expression in hepatoma cells. Oncology Reports . 2012;27(1):168–173. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y., Zhu Z., Zhang S., et al. ShRNA-targeted centromere protein A inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma growth. PLoS One . 2011;6(3, article e17794) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y. M., Zhu Z., Chen Y., Luo Z. G., Shi M., Zhu M. H. Effect of siRNA targeting centromere protein-A gene on biological behavior of HepG2 cells. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi . 2008;37(2):124–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y. M., Liu X. H., Cao X. Z., Wang L., Zhu M. H. Expression of centromere protein A in hepatocellular carcinoma. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi . 2007;36(3):175–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He P., Hu P., Yang C., He X., Shao M., Lin Y. Reduced expression of CENP-E contributes to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma and is associated with adverse clinical features. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy . 2020;123:p. 109795. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu B., Luo H., Wu G., Liu J., Pan J., Liu Z. Low expression of spindle checkpoint protein, Cenp-E, causes numerical chromosomal abnormalities in HepG-2 human hepatoma cells. Oncology Letters . 2015;10(5):2699–2704. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z., Ling K., Wu X., et al. Reduced expression of CENP-E in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research . 2009;28(1):p. 156. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li S., Li X., Xu A., et al. Screening and clinical evaluation of dominant peptides of centromere protein F antigen for early diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Molecular Medicine Reports . 2018;17(3):4720–4728. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dai Y., Liu L., Zeng T., et al. Characterization of the oncogenic function of centromere protein F in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications . 2013;436(4):711–718. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim H. E., Kim D. G., Lee K. J., et al. Frequent amplification of CENPF, GMNN and CDK13 genes in hepatocellular carcinomas. PLoS One . 2012;7(8, article e43223) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu G., Hou H., Lu X., et al. CENP-H regulates the cell growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells through the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Oncology Reports . 2017;37(6):3484–3492. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu G., Shan T., He S., et al. Overexpression of CENP-H as a novel prognostic biomarker for human hepatocellular carcinoma progression and patient survival. Oncology Reports . 2013;30(5):2238–2244. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J., Li H., Xia C., et al. Downregulation of CENPK suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma malignant progression through regulating YAP1. OncoTargets and Therapy . 2019;Volume 12:869–882. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S190061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang H., Liu W., Liu L., et al. Overexpression of centromere protein K (CENP-K) gene in hepatocellular carcinoma promote cell proliferation by activating AKT/TP53 signal pathway. Oncotarget . 2017;8(43):73994–74005. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Z., Zhou Z., Huang Z., He S., Chen S. Histone-fold centromere protein W (CENP-W) is associated with the biological behavior of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Bioengineered . 2020;11(1):729–742. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2020.1787776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun C. C., Li S. J., Hu W., et al. Comprehensive analysis of the expression and prognosis for E2Fs in human breast cancer. Molecular Therapy . 2019;27(6):1153–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Sun C. C., Li S. J., Chen Z. L., Li G., Zhang Q., Li D. J. Expression and prognosis analyses of runt-related transcription factor family in human leukemia. Molecular Therapy - Oncolytics . 2019;12:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2018.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun C. C., Zhou Q., Hu W., et al. Transcriptional E2F1/2/5/8 as potential targets and transcriptional E2F3/6/7 as new biomarkers for the prognosis of human lung carcinoma. Aging . 2018;10(5):973–987. doi: 10.18632/aging.101441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhodes D. R., Yu J., Shanker K., et al. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia . 2004;6(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/S1476-5586(04)80047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang Z., Li C., Kang B., Gao G., Li C., Zhang Z. GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Research . 2017;45(W1):W98–W102. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagy A., Lanczky A., Menyhart O., Gyorffy B. Validation of miRNA prognostic power in hepatocellular carcinoma using expression data of independent datasets. Scientific Reports . 2018;8(1):p. 9227. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27521-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uhlen M., Fagerberg L., Hallstrom B. M., et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science . 2015;347(6220, article 1260419) doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wurmbach E., Chen Y. B., Khitrov G., et al. Genome-wide molecular profiles of HCV-induced dysplasia and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology . 2007;45(4):938–947. doi: 10.1002/hep.21622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roessler S., Jia H. L., Budhu A., et al. A unique metastasis gene signature enables prediction of tumor relapse in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Cancer Research . 2010;70(24):10202–10212. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen X., Cheung S. T., So S., et al. Gene expression patterns in human liver cancers. Molecular Biology of the Cell . 2002;13(6):1929–1939. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-02-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiao Y., Najeeb R. M., Ma D., Yang K., Zhong Q., Liu Q. Upregulation of CENPM promotes hepatocarcinogenesis through mutiple mechanisms. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research . 2019;38(1):p. 458. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1444-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holland A. J., Cleveland D. W. Boveri revisited: chromosomal instability, aneuploidy and tumorigenesis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology . 2009;10(7):478–487. doi: 10.1038/nrm2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cimini D. Merotelic kinetochore orientation, aneuploidy, and cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta . 2008;1786(1):32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tomonaga T., Nomura F. Chromosome instability and kinetochore dysfunction. Histology and Histopathology . 2007;22(2):191–197. doi: 10.14670/HH-22.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okada M., Cheeseman I. M., Hori T., et al. The CENP-H-I complex is required for the efficient incorporation of newly synthesized CENP-A into centromeres. Nature Cell Biology . 2006;8(5):446–457. doi: 10.1038/ncb1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from Oncomine (http://www.oncomine.org), GEPIA (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn), the Kaplan-Meier Plotter (http://www.kmplot.com), cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org), TIMER (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/), and HPA (https://www.proteinatlas.org/).