Summary

The genetic causes of global developmental delay (GDD) and intellectual disability (ID) are diverse and include variants in numerous ion channels and transporters. Loss-of-function variants in all five endosomal/lysosomal members of the CLC family of Cl− channels and Cl−/H+ exchangers lead to pathology in mice, humans, or both. We have identified nine variants in CLCN3, the gene encoding CIC-3, in 11 individuals with GDD/ID and neurodevelopmental disorders of varying severity. In addition to a homozygous frameshift variant in two siblings, we identified eight different heterozygous de novo missense variants. All have GDD/ID, mood or behavioral disorders, and dysmorphic features; 9/11 have structural brain abnormalities; and 6/11 have seizures. The homozygous variants are predicted to cause loss of ClC-3 function, resulting in severe neurological disease similar to the phenotype observed in Clcn3−/− mice. Their MRIs show possible neurodegeneration with thin corpora callosa and decreased white matter volumes. Individuals with heterozygous variants had a range of neurodevelopmental anomalies including agenesis of the corpus callosum, pons hypoplasia, and increased gyral folding. To characterize the altered function of the exchanger, electrophysiological analyses were performed in Xenopus oocytes and mammalian cells. Two variants, p.Ile607Thr and p.Thr570Ile, had increased currents at negative cytoplasmic voltages and loss of inhibition by luminal acidic pH. In contrast, two other variants showed no significant difference in the current properties. Overall, our work establishes a role for CLCN3 in human neurodevelopment and shows that both homozygous loss of ClC-3 and heterozygous variants can lead to GDD/ID and neuroanatomical abnormalities.

Keywords: CLCN, neurodevelopmental delay, intellectual disability, voltage gated chloride channel, gain of function, hippocampus, pH sensitivity, acidification

Introduction

The causes of global developmental delay (GDD) and intellectual disability (ID) are multifactorial with recent data suggesting that a majority of cases are secondary to an underlying genetic disorder.1,2 Owing to the complexity of the human brain, variants in a wide range of genes, including those encoding ion transport proteins, have been associated with neurodevelopmental disorders and epilepsy. Such transport proteins can localize to the plasma membrane or to intracellular organelles, such as endosomes and lysosomes. The former influence cellular excitability or regulate intra- or extracellular ion concentrations, whereas the latter modulate vesicular trafficking or cellular metabolism.

The CLC family of Cl− channels and transporters3 comprises nine members in mammals. Whereas ClC-1, ClC-2, ClC-Ka, and ClC-Kb are plasma membrane chloride channels, CIC-3, CIC-4, CIC-5, CIC-6, and CIC-7 reside on vesicles of the endosomal/lysosomal system and mediate 2Cl−/H+ exchange. Together with proton pumps, these vesicular CLC (vCLC) proteins support luminal acidification and Cl− accumulation, which in turn may affect endosomal/lysosomal function and trafficking by poorly understood mechanisms. ClC-5 is found predominantly on early endosomes, while ClC-3, ClC-4, and ClC-6 reside mainly on late endosomes. ClC-7, together with its β-subunit Ostm1,4 is present on lysosomes and the specialized acid-secreting ruffled border of osteoclasts.

Loss-of-function variants of all nine CLCN genes lead to pathology in mice, humans, or both.3 Loss of vesicular CLC proteins predominantly affect the nervous system, with the exception of the mainly epithelial ClC-5, whose disruption causes proteinuria and kidney stones by severely impairing proximal tubular endocytosis (CLCN5 [MIM: 300008]).5,6 Although Clcn4−/− mice lack obvious phenotypes,7,8 loss-of-function variants in human CLCN4 (MIM: 302910) cause syndromic intellectual disability that often presents with seizures and dysmorphic facial features.9,10 Loss of ClC-6 function leads to a mild form of neuronal lysosomal storage disease in mice.11 A recurrent gain-of-function CLCN6 variant (MIM: 602726) leads to severe global developmental delay, hypotonia, respiratory insufficiency, neurodegeneration, and associated MRI abnormalities in humans,12 and an individual heterozygous for a different CLCN6 variant presents with West syndrome.13,14 Loss of lysosomal ClC-7 results in pronounced, mainly neuronal, lysosomal storage disease and severe osteopetrosis in mice and humans (CLCN7 [MIM: 602727]).15,16 Disruption of mouse Clcn3 results in drastic neurodegeneration with loss of the hippocampus a few months after birth and early retinal degeneration.17 To date, human disease causing CLCN3 (MIM: 600580) variants have not been reported.

Vesicular CLC proteins are voltage-gated Cl−/H+-antiporters that exchange two Cl− ions for one H+ ion. They generate electrical currents that may be needed for efficient operation of vesicular H+-ATPases,3,18,19 although other vesicular conductors might substitute for vCLCs in vesicle acidification.20 vCLCs also concentrate Cl− in the vesicle lumen, a role that depends on the coupling of Cl− to H+ fluxes.21 The importance of this function is emphasized by the observation that knock-in mice carrying uncoupling point variants display phenotypes resembling those of the respective knock-out mice.8,19,21 Although the mechanisms by which variants in vCLCs lead to disease remain poorly understood, it is well established that loss of CLC function can disrupt endosomal trafficking6 or lysosomal protein degradation.15,22 Many of these insights have been gleaned from mouse models or from patients carrying various loss- or gain-of-function variants in CLCN genes.

We now report 11 individuals, 9 that carry 8 different rare heterozygous missense variants in CLCN3 (MIM: 600580) and 2 siblings that are homozygous for a frameshift variant likely abolishing ClC-3 function. All 11 have GDD or ID and dysmorphic features, and a majority has mood or behavioral disorders and structural brain abnormalities. The severity of disease in the two individuals with homozygous disruption of ClC-3 is consistent with the drastic phenotype seen in Clcn3−/− mice.17 Electrophysiological analysis of four of the individuals’ missense variants revealed that two variants, p.Ile607Thr (c.1820T>C) and p.Thr570Ile (c.1709C>T), increase ion transport by the ClC-3 transporter. Overall, our work establishes variants in CLCN3 as a cause of GDD/ID and structural brain anomalies.

Subjects and methods

Human subjects

A parent or legal guardian provided informed consent for all subjects in accordance with local institutional review boards of the participating centers. MRIs from individuals (I) 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10.1, and 10.2 were obtained and reviewed by a single pediatric radiologist at Boston Children’s Hospital to evaluate the findings.

Expression constructs

A plasmid of mouse ClC-3, splice variant c, kindly provided by C. Fahlke (Forschungszentrum Jülich, Germany), contained EGFP fused to the C terminus in the background of the mammalian expression vector FsY1.1 G.W. For oocyte expression, the open reading frame was subcloned in the PTLN vector,23 in which the disease-associated variants were introduced using standard restriction free mutagenesis. Using suitable restriction enzymes and ligation, the variants were transferred to the FsY1.1 G.W. vector. All constructs were verified by Sanger sequencing. Mouse and human ClC-3 differ in three amino acid positions. With numbering referring to the long human splice B isoform, these are: G205E (not conserved among ClC-3-5), I494V (conservative change, being V also in ClC-4 and -5), and N663S (not conserved among ClC-3-5). The regions around the functionally studied mutations are identical.

Expression in oocytes

After linearization with MluI, RNA was transcribed using the SP6 mMessageMachine kit (Thermofisher). Oocytes were obtained, injected with 10 ng of RNA, and incubated at 18°C for 2–4 days prior to measurements as described previously.24

Expression in mammalian cell lines

HEK293 cells were maintained in standard culture conditions and transfected using the Effectene kit (QIAGEN) or using the FuGENE HD Transfection Reagent (Promega). 24 h after transfection, cells were split and seeded on glass coverslips and incubated for another 24 h. Tmem206−/− HEK cells were seeded on coverslips 1–5 h prior to measurements. Positively transfected cells were identified and selected for patch clamping by means of fluorescence microscopy. Confocal microscopy did not reveal obvious differences in plasma membrane expression among the variants.

Two-electrode voltage clamp recordings

Recording pipettes were filled with 3 M KCl (resistance about 0.6 MOhm) and currents were recorded using a TEC03 two-electrode voltage clamp amplifier (npi electronics). Ground electrodes were connected to the bath via agar bridges. The standard extracellular solution contained 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgSO4, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.3). Transient currents were recorded in a Cl− free solution exchanging Cl− by glutamate. For solutions at pH 6.3 and 5.3, MES buffer replaced HEPES. For the solution at pH 4.3, 10 mM glutamic acid replaced HEPES as buffer. Currents were acquired using the custom GePulse acquisition program and an itc-16 interface (Instrutech). Two types of stimulation protocols were applied from a holding potential of −30 mV. The first consisted of 10 ms pulses to voltages ranging from +160 to −120 mV (in 20 mV steps) without leak subtraction. The second protocol consisted of steps ranging from +170 to −10 mV (in 10 mV steps), applying linear-leak and capacity subtraction using a “P/4” leak subtraction protocol from the holding potential −30 mV. Only with this protocol could transient currents be resolved.

Patch clamp recordings

For the recordings shown in Figures 3B, 4C, and 4D, currents were recorded in the standard whole-cell configuration at room temperature using a MultiClamp 700B patch-clamp amplifier/Digidata 1550B digitizer and pClamp 10 software (Molecular Devices). Patch pipette solution contained 140 mM CsCl, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES (pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH). The extracellular solution: 150 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5 [NaOH]). The bath solution with pH 5.0 was buffered with MES. Series resistance was compensated by 60%. During acquisition, recordings were filtered with a low pass Bessel filter at 6 kHz and sampled at 10 kHz. Voltage step protocol consisted of 0.5 s voltage steps starting from −100 to +140 mV in 20-mV increment from a holding potential of −30 mV.

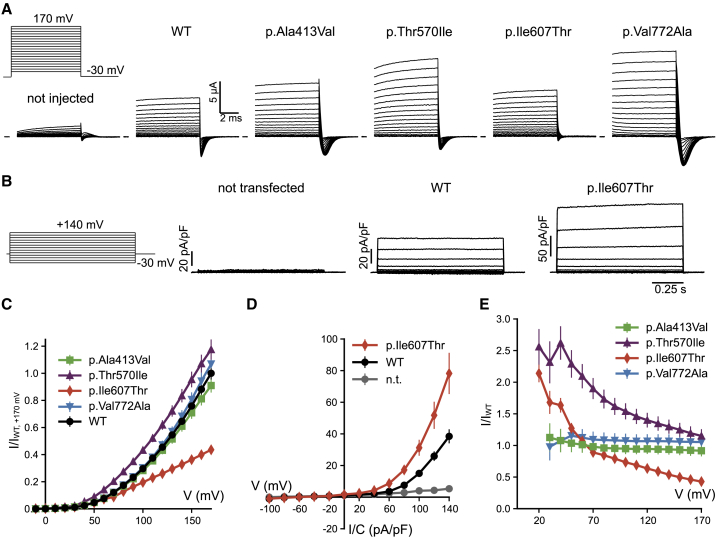

Figure 3.

Functional expression of CLCN3 variants

(A) Voltage protocol and typical current traces obtained for WT and indicated variants in Xenopus oocytes. Linear leak and capacitance were subtracted using a P/n protocol. Traces have been clipped to hide the residual capacitative artifact.

(B) Voltage protocol and typical current traces obtained for WT and variant p.Ile607Thr in HEK293 cells.

(C) Average normalized current-voltage relationship measured in oocytes, normalized to WT currents at 170 mV (see Subjects and methods). For variant p.Ile607Thr values are significantly different from WT for V ≥ 120 mV (p < 0.05, Student’s t test). All other values are not significantly different from WT (p > 0.05, Student’s t test).

(D) Average current-density voltage relationship of WT and variant p.Ile607Thr measured in HEK293 cells. p.Ile607Thr values are significantly different from WT for V ≥ 0 mV (p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test).

(E) Average ratio of mutant versus WT currents in Xenopus oocytes (see Subjects and methods). For variants p.Ala413Val and p.Val772Ala, the ratio is close to 1 at all voltages, indicating similar rectification properties compared to WT. In contrast, for p.Thr570Ile and p.Ile607Thr the ratio is voltage dependent, becoming smaller at more positive voltages, indicating that rectification is shallower compared to WT. All error bars indicate SEM.

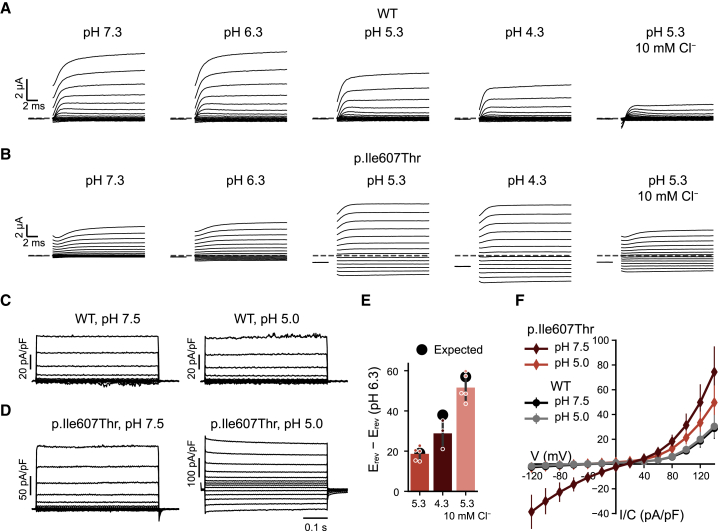

Figure 4.

Induction of inward currents of variants p.Ile607Thr and p.Thr570Ile at acidic pHo

(A) Typical currents of an oocyte expressing WT ClC-3 in the presence of different pH values and in a low Cl− solution at pH 5.3.

(B) Typical currents of an oocyte expressing variant p.Ile607Thr. For display reasons, capacitance (but not leak) was partially subtracted using the capacitive transients upon return to the holding potential.

(C and D) Typical current traces of WT (C) or variant p.Ile607Thr (D) expressed in Tmem206−/− HEK cells.

(E) Difference of reversal potential measured for p.Ile607Thr in oocytes in the indicated conditions and that measured at pH 6.3 (bars) (a liquid junction potential of 8 mV was added to the values measured in the low Cl− condition). Expected values were calculated assuming a 2 Cl−:1 H+ transport stoichiometry.33 For variant p.Ile607Thr, reversal potentials could be obtained at pH 6.3 and lower.

(F) Average current-density voltage relationship of WT and variant p.Ile607Thr measured in Tmem206−/− HEK cells at pH 7.5 and pH 5.0. For V ≤ 0 mV values of variant p.Ile607Thr are significantly different from those of WT (p < 10−4, Student’s t test). All error bars indicate SEM.

For the recordings shown in Figure S2, recording pipettes were filled with a solution containing 130 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.3) and had resistances of 1–2 MOhm. The extracellular solution contained 145 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.3). Data were acquired at 100 kHz, filtered at 10 kHz using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon), the GePulse acquisition program, and a National Instruments PCI6021 interface. Pulse protocols were similar to those used for two-electrode voltage-clamp recordings except that the holding potential was 0 mV and pulse protocols were shorter. Series-resistance and capacitance were compensated in most recordings by at least 60%. Transient currents could be well recorded even in the high chloride solution using a P/4 leak subtraction protocol.

Data analysis

In order to evaluate the relative expression levels of mutants and WT in oocytes, currents were measured for ≥6 oocytes for each batch of injection of each construct, and the average current-voltage relationship was obtained. Average currents from ≥6 non-injected oocytes from the same batch were subtracted. For the data shown in Figure 3C, currents were normalized to the current measured for WT from the same batch at 170 mV, and data from at least 4 injections for each construct were averaged. For the data shown in Figure 3E, currents were normalized at each voltage to the respective current measured for WT. This procedure highlights possible alterations of the voltage dependence. A voltage-independent reduction (or increase) in current size would result in a voltage-independent ratio (as seen for variants p.Ala413Val [c.1238C>T] and p.Val772Ala [c.2315T>C]). For variants p.Ile607Thr and p.Thr570Ile, the ratio is voltage dependent.

Transient currents were recorded upon return to the holding potential, integrated, and plotted as a function of the prepulse-voltage (Figures S1 and S2). The resulting charge voltage-relationship was fitted by a Boltzmann distribution of the form

where Qmax is the (extrapolated) maximal charge, V1/2 the voltage of half maximal displacement, z the gating valence, qe the absolute charge of the electron, k the Boltzmann constant, and T the temperature. The ratio Qmax / I(170 mV in high Cl−), was used to quantitate the amount of transient charge compared to ionic currents (see Figures S1 and S2).

For data analysis of currents measured at various external pH values shown in Figure 5, the following leak-subtraction was performed. For each oocyte, currents measured at pH 7.3 were fitted in the range −120 mV ≤ V ≤ 0 mV with a straight line. The line was extrapolated to all voltages and subtracted from the IVs measured in the various conditions and then normalized to the current at pH 7.3, 160 mV. This is based on the fact that for WT ClC-3 and the four studied variants, at pH 7.3, currents recorded at voltages V ≤ 0 mV are very small and indistinguishable from currents in uninjected oocytes and represent a mixture of leak and endogenous currents. Error bars in all figures represent SEM.

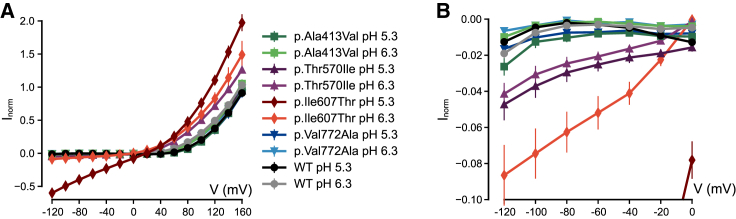

Figure 5.

Effect of acidic pH on all variants expressed in Xenopus oocytes

Normalized currents measured for WT and all four variants at pH 5.3 and pH 6.3, leak-subtracted as described in Subjects and methods. For variants p.Thr570Ile and p.Ile607Thr, values are significantly different from those of WT at all voltages (p < 10−5, Student’s t test). For variants p.Ala413Val and p.Val772Ala, values are not significantly different from WT (p > 0.05, Student’s t test). Same data as (A) shown at higher magnification in (B). All error bars indicate SEM.

Results

Identification of CLCN3 variants in individuals with GDD/ID

Individuals with GDD/ID and rare variants in CLCN3 were identified through an international collaboration facilitated by MatchMaker Exchange (Table 1).25, 26, 27 CLCN3 variants were identified through clinical trio exome sequencing (I:1, I:2, I:5, I:8), clinical trio exome sequencing with research reanalysis (I:9),28 research trio exome sequencing (I:7, I:10.1, I:10.2), research trio genome sequencing (I:6), and singleton clinical exome sequencing (I:3, I:4).

Table 1.

Clinical and genetic findings of individuals with variants in CLCN3

| Individual # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10.1 | 10.2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLCN3 variant information | |||||||||||

| Genomic (GRCh38) | chr4: 169680143-A-G | chr4: 169692139-T-C | chr4: 169695646 T>C | chr4: 169697409-C-T | chr4: 169697528-A-C | chr4: 169704143-C-T | chr4: 169704143-C-T | chr4: 169706937-T-C | chr4: 169713244-T-C | chr4: 169687675_169687678del | chr4: 169687675_169687678del |

| cDNA (NM_173872.3) | c.254A>G | c.755T>C | c.971T>C | c.1238C>T | c.1357A>C | c.1709C>T | c.1709C>T | c.1820T>C | c.2315T>C | c.336_339del | c.336_339del |

| Protein | p.Tyr85Cys | p.Ile252Thr | p.Val324Ala | p.Ala413Val | p.Ser453Arg | p.Thr570Ile | p.Thr570Ile | p.Ile607Thr | p.Val772Ala | p.Lys112Asnfs∗6 | p.Lys112Asnfs∗6 |

| Inheritance | de novo | de novo | de novo | unknown (adopted) | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo | de novo | homozygous (parents unaffected) | homozygous (parents unaffected) |

| Sequencing method | trio WES, clinical | trio WES, clinical | WES, research | singleton WES, clinical | trio WES, clinical | trio WGS, research | trio WES, research | trio WES, clinical | trio WES, clinical | trio WES, research | trio WES, research |

| CADD score | 28.7 | 26.2 | 27.4 | 22.3 | 26.7 | 23.6 | 23.6 | 27.1 | 23.4 | 32 | 32 |

| Patient information | |||||||||||

| Sex | female | male | male | female | female | female | female | female | male | male | male |

| Ethnicity | Turkish (consanguineous) | European | European | European | Metis/European | European | Ashkenazi Jewish | European | Uruguayan | European | European |

| Institution | Erasmus University Medical Center | Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital | University of California San Francisco | Emory University School of Medicine | University of British Columbia | Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard | University of British Columbia | University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf | Boston Children’s Hospital | University Hospital of Düsseldorf | University Hospital of Düsseldorf |

| Age | 16 y | 5 y | 17 y | 10 y | 5 y | 13 y | 12 y | 23 d (deceased) | 7 y | 18 m | 14 m (deceased) |

| Gestational age | 40 weeks | 39 weeks | 39 3/7 weeks | ND | 41 3/7 weeks | 41 2/7 weeks | approx. 40 weeks | 39 6/7 weeks | approx. 39 weeks | 40 weeks | 40 weeks |

| Birth weight | 4,000 g (+1.57 SD, 94th %ile) | 3,340 g (−0.35 SD) | 3,020 g (−0.89 SD, 19th %ile) | ND | 3,960 g (>+1.19 SD, >88.3%ile) | 2,790 g (−1.01 SD, 16th %ile) | 3,203 g (−0.06 SD, 47th %ile) | 3,130 g (−0.8 SD) | 2,485 g (−3.94 SD, 3rd %ile) | 3,230 g (25th %ile) | 3,660 g (50th %ile) |

| Birth length | ND | 52 cm (+0.70 SD) | 50 cm (−0.22 SD, 41%ile) | ND | 54 cm (+2.17 SD, 98.5%ile) | 52 cm (+1.59 SD, 94th %ile) | 49 cm (−0.08 SD, 47th %ile) | 50.8 cm (−0.4 SD) | 44 cm (−3.11 SD, 0%ile) | 53 cm (50th %ile) | 55 cm (90–97th %ile) |

| OFC Birth | ND | 34.5 cm (−0.61 SD) | 33 cm (−1.16 SD, 12th %ile) | ND | 35 cm (+0.42 SD, 66.4%ile) | 32 cm (−1.59 SD, 6th %ile) | 33.5 cm (−0.32 SD, 37th %ile) | 40.5 cm (+4.5 SD) | ND | 34 cm (10th %ile) | 34.5 cm (10–25th %ile) |

| Failure to thrive | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N |

| Feeding issues | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Neurological features | |||||||||||

| Speech development | delayed | absent | absent | delayed | delayed | delayed with regression at 3 y | delayed | N/A | absent | absent | absent |

| Gross motor development | delayed, walks independently | delayed, walks independently (starting a 6 y) | delayed, does not walk independently | delayed, walks independently | delayed, walks independently with difficulty and AFOs | delayed, walks independently | delayed, walks independently | N/A | delayed, sits supported, cannot crawl or walk | delayed, does not walk independently | delayed, never walked independently |

| Fine motor development | delayed | delayed | delayed | delayed | delayed | delayed | delayed | N/A | delayed | delayed | delayed |

| Developmental delay/intellectual disability | mild-moderate ID (IQ 55) | severe ID (QS 24) | severe ID | mild ID (IQ 71) | GDD | profound ID | mild-moderate ID | N/A | severe ID | GDD | GDD |

| Seizures | N | tonic clonic, onset 29 m | myoclonic, onset 4 y, controlled by clobazam + oxcarbazepine | N | non-clinical seizures | N | N | N | seizures, onset 6 m, well controlled w/ Keppra | focal seizure onset in neonatal period; start at 3 months multifocal tonic and myoclonic seizures | seizure onset 3 months, tonic and myoclonic |

| Autism | Y | not evaluated | N | Y | N | Y | N | N/A | N | N | Y |

| Hypotonia | N | severe | moderate | mild | moderate | mild | moderate | N | truncal and nuchal | N | N, has severe spasticity |

| Mood or behavioral abnormalities | temper tantrums since puberty | N | N | hyperactive, OCD, anxiety, stereotypies | self- stimulatory actions when younger | severe anxiety, self-injurious, intermittent explosive behavior | severe anxiety | N/A | N | severe restlessness | N |

| Other Clinical Findings | |||||||||||

| Vision/Eye abnormalities | N | unilateral strabismus | bilateral partial optic atrophy, retinal dystrophy, nystagmus | strabismus | strabismus, intermittent right exotropia | strabismus, hyperopia | anisometropia | N/A | esotropia | salt and pepper fundus pigmentation, nystagmus, no fixation | salt and pepper fundus pigmentation, nystagmus, no fixation |

| Hearing impairment | N | N | N | unilateral hearing impairment due to hx of cholesteatoma | N | mild sensorineural hearing loss | N | N/A | N | N | N |

| Dysmorphic features | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Congenital anomalies | N | N | crytorchdism | possible hydrocephalus at birth | N | N | N | arthrogryposis multiplex congenita, hip dislocation | ASD, BL talipes equinovarus, BL renal pyelectasis, BL hand contractures, congenital radial head dislocation, hypoplastic/absent coccyx | N | N |

Y, present; N, absent; ND, no data; N/A, not applicable; GDD, global developmental delay; BL, bilateral.

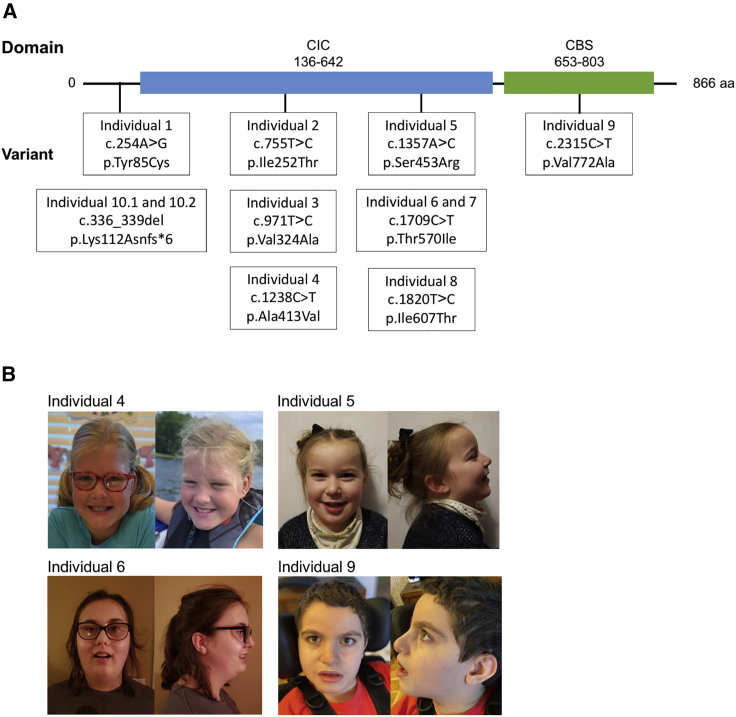

Nine individuals (1–9) in the cohort harbor eight different heterozygous missense variants, whereas a pair of siblings (I:10.1, I:10.2) carried homozygous frameshift variants predicted to truncate the ClC-3 protein before the first transmembrane domain (Table 1, Figure 1). All missense variants were confirmed to be de novo in eight individuals for whom parental data was available. The Combined Annotation Depletion Score (CADD) scores for the missense variants ranged from 22.3 to 28.7, suggesting that the variants have a deleterious impact. The CADD score within that range did not correlate with the individual’s clinical severity. The CADD scores from lowest to highest were as follows: c.1238C>T (p.Ala413Val), c.2315T>C (p.Val772Ala), c.1709C>T (p.Thr570Ile), c.755T>C (p.Ile252Thr), c.1357A>C (p.Ser453Arg), c.1820T>C (p.Ile607Thr), c.971T>C (p.Val324Ala), c.254A>G (p.Tyr85Cys) (GenBank: NM_173872.3, GRCh38). All of the variants identified are absent from gnomAD, and the data from gnomAD suggests that CLCN3 is a highly constrained gene that is intolerant of missense variation (z-score: 4.37) and loss of function (pLi = 1, LOEUF = 0.22).

Figure 1.

CLCN3 variants in affected individuals

(A) Domains present in the protein ClC-3 and the variants presented in the affected individuals.

(B) Pictures of individuals 4, 5, 6, and 9. Individual 4 has a prominent forehead, bushy eyebrows, mild downslanting palpebral fissures, posteriorly rotated ears, and full cheeks; high arched palate also present, but not shown. Individual 5 has a bossed forehead, high anterior hairline, and hypertelorism; clinodactyly of 5th digits also present, but not shown. Individual 6 has notable midface retrusion, full cheeks, and prognathia. Individual 9 has mildly down slanting palpebral fissures, epicanthal folds, flat midface, and mild micrognathia; brachycephaly and long digits also present, but not shown.

The 11 individuals in the cohort share clinical features of variable severity (Table 1). They were all diagnosed with GDD and ID, if old enough for testing. Their ID ranged in severity from mild to profound. All of the individuals demonstrated delayed gross motor, fine motor, and language development, with five of them never developing speech (Table 1). The structural brain abnormalities on MRI (9/11) included partial or full agenesis of the corpus callosum (6/9), disorganized cerebellar folia (4/9), delayed myelination (3/9), decreased white matter volume (3/9), pons hypoplasia (3/9), and dysmorphic dentate nuclei (3/9) (Table S1, Figure 2). Six of those with brain abnormalities also presented with seizures. Nine have abnormal vision, including strabismus in four and inability to fix or follow in the two with homozygous loss-of-function variants (I:10.1, I:10.2). Hypotonia ranging from mild to severe was reported in 7 of the 11 individuals. Six have mood or behavioral disorders, particularly anxiety (3/6). Consistent dysmorphic facial features included microcephaly, prominent forehead, hypertelorism, down-slanting palpebral fissures, full cheeks, and micrognathia. The disease was more severe in two siblings carrying homozygous loss-of-function variants (I:10.1, I:10.2) with the presence of GDD, absent speech, seizures, and salt and pepper fundal pigmentation in both individuals, with one deceased at 14 months of age (I:10.2). The siblings also had significant neuroanatomical findings including diffusely decreased white matter volume, thin corpora callosa, small hippocampi, and disorganized cerebellar folia. In comparison, the heterozygous de novo variants caused a spectrum of disease. In individual 8, p.Ile607Thr caused severe disease; she had complex brain malformation and died within the first month of life. In contrast, the p.Thr570Ile variant was de novo in two individuals (I:6, I:7) of different ethnicities and was associated with severe anxiety, mild-moderate ID, hypotonia, and increased gyral folding on brain MRI in both individuals.

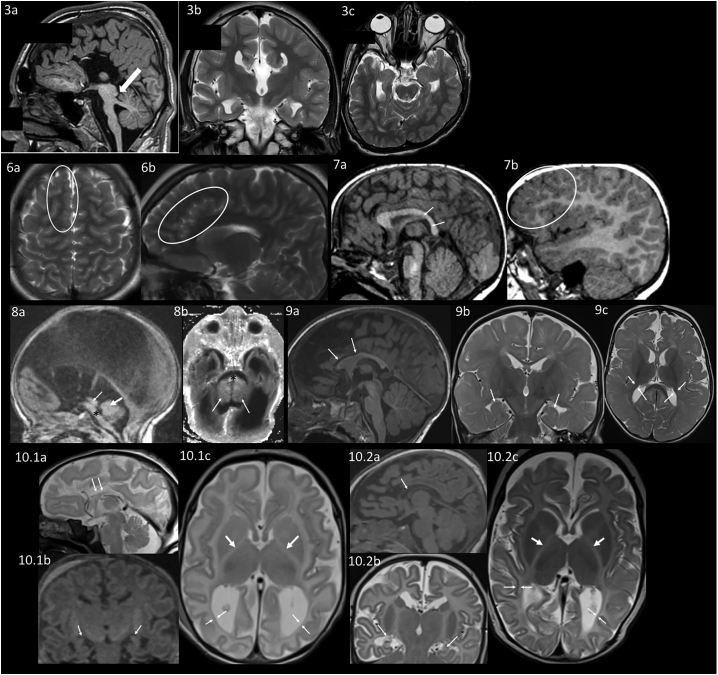

Figure 2.

Neuroanatomical differences appreciated on brain MRI

MRI of individual 3. 3a: Sagittal T1 weighted image shows complete absence of the corpus callosum, a hypoplastic pons and a prominent superior cerebellar peduncle (arrow). 3b: Coronal T2 weighted image also shows an absent corpus callosum. 3c: Axial T2 weighted image shows left plagiocephaly.

MRI of individual 6 at an unknown age. 6a: Axial T2 Blade showing increased gyral folding in the frontal lobes (circle). 6b: Sagittal T2 Blade showing increased gyral folding in the parasagittal frontal lobe (circle).

MRI of individual 7 at 2 years. 7a: Sagittal 3D FLASH in the midline showing small posterior body and splenium of the corpus callosum (arrows). 7b: Sagittal 3D FLASH of the right hemisphere showing increased gyral folding in the frontal lobes (circle).

MRI of individual 8 as an infant. 8a: Sagittal T1 showing hypoplastic pons (∗), aqueductal stenosis (thin arrow), and small vermis (thick arrow). 8b: Axial inversion recovery T1 showing hypoplastic pons (∗) and small cerebellar hemispheres (arrowheads).

MRI of individual 9 at 11 months. 9a: Sagittal MPRAGE shows thin corpus callosum, particularly the anterior body and genu (arrows). 9b: Coronal T2 TSE with incompletely rotated hippocampi (arrows). 9c: Axial T2 TSE showing delayed myelination (myelination should be seen in the gyri throughout the posterior temporal and occipital lobe and decreased white matter volume shown by arrows).

MRI of individual 10.1 as a neonate. 10.1a: Sagittal T2 showing hypoplastic thin corpus callosum (arrows). 10.1b: Coronal reformation of sagittal MPGR showing small incompletely rotated hippocampi (arrows). 10.1c: Axial T2 showing lack of myelin in the posterior limb internal capsule (thick arrows) and decreased white matter volume (thin arrows).

MRI of individual 10.2 as a neonate. 10.2a: Sagittal MPGR showing hypoplastic thin corpus callosum (arrow). 10.2b: Coronal T2 TSE showing small incompletely rotated hippocampi (arrows). 10.2c: Axial T2 TSE showing lack of myelin in the posterior limb internal capsule (thick arrows) and decreased white matter volume (thin arrows).

Electrophysiological analysis of ClC-3 variants at neutral external pH

Clcn3−/− mice display severe neurodegeneration, whereas heterozygous Clcn3+/− mice appear normal.17 Similarly, the bi-allelic disruption of ClC-3 manifests as a severe neurodevelopmental disorder in individuals 10.1 and 10.2, and their carrier parents are unaffected. In this context, we hypothesized that in other families, monoallelic variants alter neurodevelopment through a gain-of-function mechanism, rather than loss of function. To test this hypothesis, we selected four variants that resulted in a range of neurodevelopmental impairment for electrophysiological analysis: p.Ile607Thr, p.Val772Ala, p.Thr570Ile, and p.Ala413Val. Variant p.Ile607Thr (I:8) led to the most severe neurological outcome in a heterozygous individual, p.Val772Ala (I:9) caused moderate to severe neurological disorder and had associated congenital anomalies, p.Thr570Ile (I:6, I:7) led to a mild-moderate neurological disorder in two individuals, and p.Ala413Val (I:4) caused a mild neurological disorder.

In native cells, ClC-3 primarily resides on late endosomes.8,17 This localization prevents straightforward electrophysiological characterization by measurements of plasma membrane currents. However, inclusion of an alternative 5′ exon (exon c), which replaces the extreme amino terminus of the ClC-3 sequence, allows for partial targeting of the protein to the plasma membrane when it is overexpressed and enables characterization by measuring whole cell currents.29 In order to understand how the variants in our human cohort altered function, we inserted the four variants into exon c-containing ClC-3 cDNA sequence and compared their electrophysiological properties to those of WT ClC-3. Upon expression in Xenopus oocytes, all variants yielded currents at positive voltages with amplitudes that, except for variant p.Ile607Thr (I:8), were comparable to those of WT (Figures 3A and 3C). Currents from variant p.Ile607Thr were moderately decreased; however, the decrease in amplitude of ClC-3I607T is of unclear significance, since overexpression of the same variant in HEK cells rather lead to an increase in current amplitudes compared to WT (Figures 3B and 3D). These quantitative differences in amplitudes might reflect disparities between expression systems or effects on surface targeting and likely lack physiological relevance.

To test quantitatively whether any of the variants changed the voltage-dependent rectification, we calculated the ratio of currents mediated by the mutants and the WT at each voltage in Xenopus oocytes. For variants p.Ala413Val (I:4) and p.Val772Ala (I:9), this ratio was close to one at all voltages, indicating that their rectification is indistinguishable from WT (Figure 3E). In contrast, for p.Thr570Ile (I:6, I:7) and p.Ile607Thr (I:8), this ratio decreased with increasingly positive voltages indicating that their rectification was less than that of WT (Figure 3E). The reduced rectification of p.Ile607Thr was not apparent in HEK293 cells (Figure 3D), suggesting that functional properties depend to a certain degree on the expression system.

Upon voltage steps, ClC-3 generates large transient currents29,30 that probably result from the relaxation of voltage-dependent protein conformations rather than from ion transport across the membrane. The physiological importance, if any, of these currents remains unclear. Such transient currents were seen for WT ClC-3 and for variants p.Ala413Val (I:4), p.Thr570Ile (I:6, I:7), and p.Val772Ala (I:9), but not for variant p.Ile607Thr (I:8) (Figure S1A). The biophysical characteristics of the transient currents, i.e., the relative size of transient charge movement and ionic currents, were indistinguishable between WT ClC-3 and variants p.Ala413Val (I:4) and p.Val772Ala (I:9) (Figures S1A–SD). Transient currents of variant p.Thr570Ile (I:6, I:7) were significantly reduced compared to WT (Figure S1C), whereas the voltage of half-maximal charge movement was not altered (Figure S1D). Similar effects of ClC-3 sequence variants on transient currents were observed with overexpression in HEK cells (Figure S2) and, therefore, are independent of the expression system.

In summary, we detected moderate changes of biophysical properties of the Thr507Ile and p.Ile607Thr variants at neutral pH; however, the biological consequences of these alterations remain unclear.

Acidic pHo profoundly changes the properties of the p.Ile607Thr mutant

ClC-3 normally resides on vesicles of the endosomal pathway, which are progressively acidified. Since the lumen of vesicles corresponds topologically to the extracellular space, we examined the effect of external pH (pHo) on the currents of surface-resident ClC-3 and its mutants expressed in Xenopus oocytes. WT ClC-3 was inhibited by acidic pHo (Figure 4A) as shown previously31 and as described earlier for the highly homologous ClC-4 and ClC-5.32 Mirroring their unchanged behavior at normal pHo, variants p.Ala413Val and p.Val772Ala showed a similar pHo dependence as WT, retaining their strong outward rectification at acidic pHo (Figure 5). By contrast, outward currents mediated by variant p.Ile607Thr were increased rather than decreased at acidic pHo, and strikingly exhibited considerable inward currents at pH 6.3, pH 5.3, and pH 4.3 (Figure 4B).

Measurements of Cl− currents at acidic pHo can be confounded by the activation of the widely expressed acid-sensitive outwardly rectifying anion channel ASOR,34 which was recently shown to be formed by Tmem206 proteins.35,36 We therefore used Tmem206−/− HEK cells35 as an expression system for examining WT and p.Ile607Thr ClC-3 at acidic pH (Figures 4C and 4D). Indeed, also in Tmem206−/− HEK cells ClC-3I607T, but not WT ClC-3, showed an increase of current amplitude at positive potentials and, most importantly, elicited currents of considerable amplitudes at cytoplasmic negative voltages (Figures 4D and 4F). The presence of currents at negative voltages enabled us to determine reversal potentials that reflect the ion selectivity of the permeation pathway and the coupling between fluxes of different ionic species. In oocytes, the mere fact that the reversal potential measured at pH 6.3 is more negative than that measured at pH 5.3 demonstrates that proton transport is contributing to the inward currents. More quantitatively, the difference of reversal potentials compared with that measured at pH 6.3 indicates that the inward currents represent to a large extent coupled 2Cl−/H+-exchange (Figure 4E). In Tmem206−/− HEK cells, the measured reversal potential of Vr ∼+18 mV markedly differs from that expected for an uncoupled Cl− conductance (Vr ∼−3 mV). Although falling short of the reversal potential predicted for a 2Cl−/H+-exchange for the ionic conditions (Vr ∼+43 mV), this indicates that protons contribute to ClC-3I607T currents at pHo 5.0 also in these cells (Figure 4F). Overall, the results indicate that the currents measured at acidic pH represent coupled Cl−/H+ antiport (Figures 4E and 4F). The differences between measured reversal potentials and those calculated for 2Cl−/H+-exchange might be due to background currents of the expression system or a minor degree of uncoupling at very acidic pH.

Detailed analysis in Xenopus oocytes revealed that variant p.Thr570Ile (individuals 6 and 7) also mediates significant inward currents at an acidic pH, although they are smaller than those of p.Ile607Thr (Figure 5; note the different scaling in Figure 5A compared to Figure 5B). In addition, variant p.Thr570Ile showed increased outward currents at pH 6.3 when compared to pH 7.3 (Figure 5A), which is a response similar to that of variant p.Ile607Thr. These results, therefore, suggest that mutants p.Ile607Thr and p.Thr570Ile show increased function at acidic pH; we speculate that this is due to a defect in the gating process that determines the activity of the transporter.

Discussion

We identified 11 individuals with syndromic GDD/ID, structural brain abnormalities, and variants in the widely expressed endosomal exchanger, encoded by CLCN3. In two siblings, a homozygous frameshift variant is predicted to cause complete loss of ClC-3 function and resulted in severe neurological disease as in Clcn3−/− mice.17 In contrast, functional evaluation of a few of the heterozygous missense variants indicated a pathogenic gain of function. Electrophysiological analysis revealed a significant increase in ion transport for variant, p.Ile607Thr, found in the most severely affected heterozygous individual (8). Similar but less pronounced changes were observed with a variant p.Thr570Ile identified in two individuals (I:6, I:7) with less severe disorders. These mutant transporters showed increased current amplitudes at the acidic pH of late endosomes where ClC-3 is normally localized. Our work suggests that loss and gain of ClC-3 function is detrimental for brain structure and function.

Loss of ClC-3 causes severe neurological disease in both mice and humans

The homozygous early frameshift variant in individuals 10.1 and 10.2 truncates the ClC-3 protein before the first transmembrane helix; it therefore predicts both a complete loss of ion transport and a lack of ClC-3 protein interactions such as the formation of heterodimers with ClC-4 in brain and other tissues.8 Without ClC-3, ClC-4 is partially retained in the ER and is more prone to degradation. As a consequence, ClC-4 levels are reduced by ∼60% in the brain of Clcn3−/− mice.8 Since loss-of-function variants in CLCN4 lead to ID, seizures, and dysmorphic features in humans,9,10,37 the predicted secondary loss of ClC-4 in individuals 10.1 and 10.2 might contribute to the severity of their disease. By contrast, no effect on ClC-4 levels is expected for CLCN3 missense variants, unless they alter ClC-3 production or interaction with ClC-4.

Clcn3−/− mice display severe neurodegeneration, leading to an almost complete loss of the hippocampus within a few months of life and to blindness from an early complete loss of photoreceptors.17 Likewise, individuals 10.1 and 10.2 have abnormal retinas with salt and pepper pigmentation appreciated on both of their funduscopic examinations; clinically, neither individual is (or was) able to fix and follow with their eyes (Table 1). Brain imaging showed diffusely decreased white matter volume and small hippocampi, which can be suggestive of neurodegeneration similar to that of Clcn3−/− mice; hypoplasia, however, cannot be ruled out since the MRIs are only from single time points. Their MRIs also revealed, like many of the other probands, significant thinning of the corpus callosum, a finding not present in Clcn3−/− mice.17,38,39 Partial or full agenesis of the corpus callosum (ACC [MIM: 217990]) was also present in five of the individuals and is a common malformation with diverse etiology, including variants in >20 genes.40 In these genetic disorders, ACC is often variable and its expression may differ between mice and humans. For instance, in ACCPN (peripheral neuropathy with agenesis of the corpus callosum, or Anderman syndrome [MIM: 218000]), which is caused by loss-of-function variants in SLC12A6 encoding the K+-Cl−-cotransporter KCC3,41 penetrance is incomplete in humans and preliminary studies in Kcc3−/− mice indicated that they have a normal corpus callosum.41,42 However, careful quantitative analysis indicated a ∼12% decrease in corpus callosum volume in Kcc3−/− mice.43 Likewise, in contrast to individuals 10.1 and 10.2, Clcn3−/− mice do not lack the corpus callosum. The severe early degeneration of the brain in Clcn3−/− mice precludes, however, a meaningful quantitative assessment of the size of their corpus callosum. Focal and generalized seizures were observed in both individuals 10.1 and 10.2. While both individuals had a history of seizures, no seizures were reported for two Clcn3−/− mouse strains,17,39 but in a third strain spontaneous seizures were observed in a few animals.38

Effect of heterozygous missense variants

For those CLCN3 missense variants for which parents were tested, all arose de novo. None of these variants predicted a truncation of the protein. Two of the four missense variants studied, p.Thr570Ile and p.Ile607Thr, exhibited a significant increase of inward currents at acidic extracellular (or luminal) pH. The effect was much more pronounced for p.Ile607Thr, which was associated with one of the most severe phenotypes in our cohort. Such inward currents have never been observed with WT ClC-3,31 nor with the highly homologous ClC-4 and ClC-5 exchangers.24,32 The absence of inward currents has been largely attributed to a “gating” process that quickly inactivates the transporters at negative voltages.3,44 A similar gating process can be introduced into ClC-5 by a single point variant24 and was recently found with a disease-causing variant of ClC-6.12 Transporter gating is also present in the lysosomal ClC-7 transporter that displays gating kinetics in the seconds range.44 Hence both variants p.Ile607Thr and p.Thr570Ile might interfere with gating, particularly at acidic luminal (or extracellular) pH, thereby allowing currents also at cytoplasmic negative potentials. These currents predominantly represent 2Cl−/H+-exchange, although their reversal potential did not fully correspond to a tightly coupled exchanger. This discrepancy may be explained by background currents endogenous to the expression system or might point to a partial uncoupling of Cl− from H+-transport caused by the variant at the acidic pHo.

Depending on the expression system, currents elicited by ClC-3I607T also exhibited slight changes in amplitudes. Decreased current amplitudes in the oocyte system likely represent diminished surface expression, as suggested by less complete glycosylation of the mutant protein observed in western blots (data not shown). By contrast, when expressed in HEK cells, the mutant displayed increased current amplitudes, a finding we confirmed for an equivalent mutant in ClC-4 (data not shown). Importantly, the transporter-intrinsic changes in pH sensitivity are independent from the non-physiological levels of surface expression and strongly support a gain of transporter function in their native, acidic environment.

ClC-3I607T not only displays inward currents at acidic pH, but almost completely lacks the transient currents seen in WT ClC-329,30 or ClC-7.45 Such transient currents are hypothesized to be associated with partial reaction cycles of CLC transporters and movements of the so-called “gating glutamate.”46,47 Variant p.Thr570Ile, which exhibits a smaller increase of inward currents at acidic pH likewise shows a partial reduction of transient currents. These transient currents are unlikely to have physiological relevance,3 but provide insight into the transport mechanism of CLC transporters.

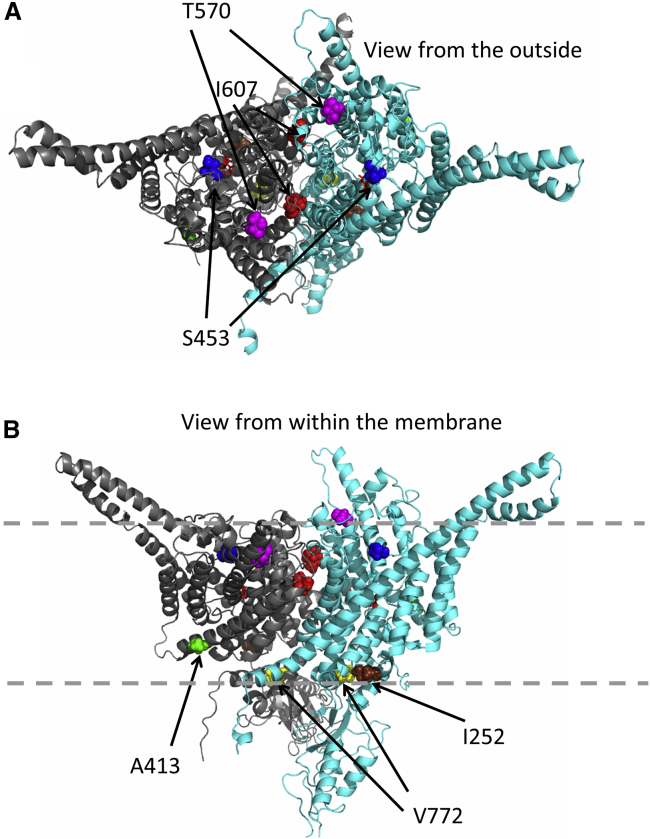

Amino acid Ile607 is located at the extracellular end of helix Q, close to the subunit interface of the CLC dimer (highlighted in red in Figure 6). This location is consistent with the hypothesis that gating of ClC-3 involves a rearrangement of the dimer interface, similar to that proposed for the “common gating” process of CLC channels3 and for the slow gating of ClC-7.48 Residue Thr570 is also located close to the outside of the channel, in the loop connecting helices N and O (highlighted in magenta in Figure 6). In contrast, residues Ala413 and Val772 are located on the intracellular side of the transporter (highlighted in green and yellow, respectively, in Figure 6). Interestingly, Ile607 corresponds to Ile422 of the bacterial ecClC-1 transporter, mutation of which to tryptophan together with another variant (p.Ile201Trp) led to a disruption of the dimeric architecture and thereby resulted in monomeric transporters.49 If the p.Ile607Thr similarly, possibly partially, destabilizes dimerization of CLC subunits, it might lead to a decrease of ClC-4 protein levels like in Clcn3−/− mice.8

Figure 6.

Mapping of variants on a homology model of ClC-3

Based on the structure of the Cm-CLC transporter _ENREF_37,50 a ClC-3 homology model was constructed by the Swiss model server. One subunit is shown in light blue, the other in gray. The “gating” glutamate is shown as red sticks. Affected residues are shown in spacefill and are color coded (red: p.Ile607Thr, magenta: Thr570, green: Ala413, yellow: Val772, brown: Ile252, blue: Ser453). A, top view from the extracellular (luminal) side; B, side view from within the membrane, which is schematically indicated by dashed lines.

We could not detect functional differences between WT ClC-3 currents and those mediated by variants p.Ala413Val and p.Val772Ala. However, our analysis only examined electrical currents at the plasma membrane, and not other parameters such as a change in subcellular localization. The different pathologies observed with variants of ClC-3, -4,9,10 and -6,11,12 which are all endosomal 2Cl−/H+-exchangers expressed in brain, suggest that subtle, poorly understood differences between these proteins are crucial for their function. However, in the absence of functional defects, we cannot strictly exclude that these variants are not causally related to the clinical phenotype.

While a detailed evaluation of the roles of ClC-3 and all the human variants is beyond the scope of this work and may require the generation of new mouse models, we can speculate on the effects of some of the missense variants we did not analyze functionally.

The tyrosine mutated in the p.Tyr85Cys variant of individual 1 is located in the cytosolic N terminus of ClC-3. As noticed before,51,52 its sequence context conforms to a tyrosine-based sorting motif (YxxΦ, with Φ being a hydrophobic, bulky amino acid such as phenylalanine in the present case). However, previous mutagenesis studies did not reveal functional effects of this tyrosine, nor of the equivalent tyrosine in the highly homologous ClC-5.51,52 In particular, mutating the equivalent Tyr residue did not result in increased surface expression of ClC-5.52 Nonetheless, we believe that altered trafficking of ClC-3Tyr85Cys remains a viable hypothesis to explain the pathological effect of this variant.

Physiological and pathological roles of ClC-3

In addition to the four plasma membrane Cl− channels, ClC-1, -2, -Ka, and -Kb, the mammalian CLC gene family encodes five different 2Cl−/H+-exchangers that are predominantly located on vesicles of the endosomal-lysosomal pathway. A common feature of those vesicular CLCs (vCLCs) is the strong outward rectification that allows ion transport only with cytoplasmic positive potential, and their inhibition by acidic extracellular (luminal) pH. Inhibition by luminal pH was hypothesized to provide a negative feedback loop for endosomal acidification,12,32 but the benefit of strong outward rectification remains mysterious.

Vesicular CLCs are believed to foster the acidification of endosomes and lysosomes by providing neutralizing countercurrents for electrogenic H+-ATPases.3,18 Whereas this has been confirmed for renal endosomal ClC-5,18,19,53 the steady-state pH of lysosomes does not depend on lysosomal ClC-7,15,21 and a role of ClC-3 in acidifying recycling and late endosomes has not been observed universally.8,39,53 At first sight, the strong voltage-dependence of vCLCs seems to contradict a role in compensating H+-ATPase currents: proton pumping is expected to generate lumen-positive potentials, which would shut down vCLC activity. However, mathematical analysis predicts that parallel operation of an H+-ATPase and a 2Cl−/H+-exchanger leads to a moderately lumen-negative potential that allows for vCLC activity and efficient acidification.21,54,55 As predicted and confirmed experimentally,21 vCLCs accumulate Cl− inside vesicles. Changes in vCLC activity likely affect not only vesicular voltage, Cl− and H+ concentrations, but indirectly also those of other ions and not least vesicular osmolarity which might, together with luminal pH and Ca2+, affect vesicle budding, fusion and trafficking. We assume that both the moderate pH dependence, as well as the strong voltage dependence of vCLCs provide crucial feedback regulation for the regulation of endosomal/lysosomal homeostasis.

It was hypothesized that the severe neurodegeneration of Clcn3−/− mice17,38,39 results from altered endo-lysosomal trafficking, but the underlying mechanism remains obscure. As mentioned before, ClC-3 disruption is associated with a marked reduction of protein levels of its binding partner ClC-4.8 However, the lack of ClC-4 is not sufficient to explain the severe phenotype of Clcn3−/− mice, since Clcn4−/− mice appear largely normal.7, 8, 9 Loss-of-function variants in human X chromosome CLCN4 lead to intellectual disability, seizures, and facial abnormalities mostly in males.9,10 After recent work associated CLCN6 variants with a neurodegenerative disorder,12 CLCN3 was the only CLCN gene for which no human disease was known.

Both CLCN3 p.Ile607Thr and p.Thr570Ile variants showed clear gain of function with the appearance of abnormal currents at lumen-positive potentials and acidic luminal pH. We suggest that these variants interfere with a negative feedback mechanism in which transport of ClC-3 is shut down when a certain threshold of luminal acidification or lumen-positive potential is reached. Loss of ClC-3 control may then cause excessive Cl− accumulation in late endosomes or lysosomes and their subsequent swelling and functional impairment, as has been suggested for ClC-6.12 Similarly, overexpression of WT ClC-3 in transfected cells was associated with large, acidified vacuoles whose generation required Cl−/H+-exchange.56

Genotype-phenotype correlations

Intriguingly, both loss and gain of ClC-3 function lead to neurodevelopmental or possible neurodegenerative disorders in humans with overlapping clinical spectra. Similar observations were made for variants in the late endosomal ClC-611,12 and the lysosomal ClC-7.16,44,57 Homozygous loss of ClC-7 function results in lysosomal storage disease and osteopetrosis,16 but several CLCN7 variants found in dominant osteopetrosis accelerate the normally very slow gating of ClC-7, resulting in a gain of ClC-7 currents at early time points.44 Another CLCN7 variant, which increased current amplitudes several-fold, led to lysosomal storage, but not osteopetrosis, and was associated with the formation of large intracellular vacuoles.57 Whereas Clcn6 disruption in mice only leads to a mild lysosomal storage disease,11 a human CLCN6 missense variant markedly increases currents and leads to severe developmental delay, ID, and neurodegeneration.12 Resembling the ClC-7 variant described by Nicoli et al.,57 the ClC-6Tyr553Cys variant induces giant lysosome-like vesicles in transfected cells.12 Akin to the present ClC-3Ile607Thr variant, ClC-6Tyr553Cys abolished the inhibition of currents by luminal acidic pH but failed to invert the pH dependence as found here for ClC-3Ile607Thr. The ClC-6 variant did not produce currents at cytoplasmic negative voltages as seen here with ClC-3Ile607Thr. In conclusion, loss- and gain-of-function variants in CLCN6, CLCN7, or CLCN3 (this work) can lead to distinct but partially overlapping phenotypes at the organismal level. In the present cohort, genotype-phenotype correlations also extend to the missense variants. The p.Ile607Thr variant, which produced a more pronounced gain of transport function than p.Thr570Ile, resulted in very severe pathology (I:8), whereas the two unrelated children carrying the latter variant (I:6, I:7) that showed less pronounced biophysical changes were less severely affected and displayed fewer abnormalities on their brain MRIs.

It is likely that the gain of currents is present not only in homodimeric mutant ClC-3 transporters, as studied here, but also in heterodimers with WT ClC-3 or ClC-4. The gating of vCLCs involves both subunits of the transporters, as illustrated by mutant ClC-7 subunits with altered opening kinetics that changed gating of associated WT subunits in the same direction.48 Hence, in heterozygous patients, the disruption induced by either variant will likely be at least partially conferred to mutant/WT and mutant/ClC-4 heterodimers. The gain of abnormal ClC-3 currents associated with both p.Ile607Thr and p.Thr570Ile, therefore, helps explain why they exert effects when present in de novo heterozygous patients. The observed correlation between amplitudes of abnormal currents and the severity of the clinical phenotype, as found with p.Thr570Ile and the more severe p.Ile607Thr mutant, further strengthens the conclusion that both variants contribute to the respective patient’s pathology. The fact that both loss and gain of function of vesicular Cl−/H+-exchangers caused abnormalities highlights that ion homeostasis of endosomes and lysosomes needs to be finely tuned.

Declaration of interests

P.B.A. is on the Scientific Advisory Board of Illumina, Inc. and GeneDx. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01AR068429-01 to P.B.A.), the National Institutes of Health (T32HD098061 to A.R.D.), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FOR 2652 (Je164/14-1,2) and Exc257 “NeuroCure”), the Prix Louis-Jeantet de Médecine to T.J.J., and by a grant from the Fondazione AIRC per la Ricerca sul Cancro (grant # IG 21558) and the Italian Research Ministry (PRIN 20174TB8KW) to M.P. This work was supported in part by the Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research and Sanger sequencing performed by the Boston Children’s Hospital IDDRC Molecular Genetics Core Facility supported by NIH award U54HD090255 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. This work was also supported by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación(MICINN) (RTI2018-093493-B-I00 to R.E.) and R.E. is a recipient of an ICREA Academia prize. The investigators of the CAUSES Study include Shelin Adam, Christele Du Souich, Alison Elliott, Anna Lehman, Jill Mwenifumbo, Tanya Nelson, Clara Van Karnebeek, and Jan Friedman. CAUSES Study was funded by Mining for Miracles, British Columbia Children’s Hospital Foundation, and Genome British Columbia.

Sequencing and analysis for individual 6 was provided by the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard Center for Mendelian Genomics (Broad CMG) and was funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute, the National Eye Institute, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants UM1 HG008900 and R01 HG009141 and by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative to the Rare Genomes Project.

Published: June 28, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.06.003.

Contributor Information

Thomas J. Jentsch, Email: jentsch@fmp-berlin.de.

Pankaj B. Agrawal, Email: pagrawal@enders.tch.harvard.edu.

Data and code availability

Data for all protein variants identified are publicly available on ClinVar. Data generated for the manuscript are available from the corresponding authors on request.

Web resources

GePulse acquisition program, http://users.ge.ibf.cnr.it/pusch/programs-mik.htm

OMIM, https://www.omim.org/

Swiss model server, https://swissmodel.expasy.org/

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Gilissen C., Hehir-Kwa J.Y., Thung D.T., van de Vorst M., van Bon B.W., Willemsen M.H., Kwint M., Janssen I.M., Hoischen A., Schenck A. Genome sequencing identifies major causes of severe intellectual disability. Nature. 2014;511:344–347. doi: 10.1038/nature13394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vissers L.E., Gilissen C., Veltman J.A. Genetic studies in intellectual disability and related disorders. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016;17:9–18. doi: 10.1038/nrg3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jentsch T.J., Pusch M. CLC Chloride Channels and Transporters: Structure, Function, Physiology, and Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2018;98:1493–1590. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00047.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lange P.F., Wartosch L., Jentsch T.J., Fuhrmann J.C. ClC-7 requires Ostm1 as a β-subunit to support bone resorption and lysosomal function. Nature. 2006;440:220–223. doi: 10.1038/nature04535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lloyd S.E., Pearce S.H., Fisher S.E., Steinmeyer K., Schwappach B., Scheinman S.J., Harding B., Bolino A., Devoto M., Goodyer P. A common molecular basis for three inherited kidney stone diseases. Nature. 1996;379:445–449. doi: 10.1038/379445a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piwon N., Günther W., Schwake M., Bösl M.R., Jentsch T.J. ClC-5 Cl- -channel disruption impairs endocytosis in a mouse model for Dent’s disease. Nature. 2000;408:369–373. doi: 10.1038/35042597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rickheit G., Wartosch L., Schaffer S., Stobrawa S.M., Novarino G., Weinert S., Jentsch T.J. Role of ClC-5 in renal endocytosis is unique among ClC exchangers and does not require PY-motif-dependent ubiquitylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:17595–17603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.115600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinert S., Gimber N., Deuschel D., Stuhlmann T., Puchkov D., Farsi Z., Ludwig C.F., Novarino G., López-Cayuqueo K.I., Planells-Cases R., Jentsch T.J. Uncoupling endosomal CLC chloride/proton exchange causes severe neurodegeneration. EMBO J. 2020;39:e103358. doi: 10.15252/embj.2019103358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu H., Haas S.A., Chelly J., Van Esch H., Raynaud M., de Brouwer A.P., Weinert S., Froyen G., Frints S.G., Laumonnier F. X-exome sequencing of 405 unresolved families identifies seven novel intellectual disability genes. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:133–148. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmer E.E., Stuhlmann T., Weinert S., Haan E., Van Esch H., Holvoet M., Boyle J., Leffler M., Raynaud M., Moraine C., DDD Study De novo and inherited mutations in the X-linked gene CLCN4 are associated with syndromic intellectual disability and behavior and seizure disorders in males and females. Mol. Psychiatry. 2018;23:222–230. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poët M., Kornak U., Schweizer M., Zdebik A.A., Scheel O., Hoelter S., Wurst W., Schmitt A., Fuhrmann J.C., Planells-Cases R. Lysosomal storage disease upon disruption of the neuronal chloride transport protein ClC-6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:13854–13859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606137103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polovitskaya M.M., Barbini C., Martinelli D., Harms F.L., Cole F.S., Calligari P., Bocchinfuso G., Stella L., Ciolfi A., Niceta M. A Recurrent Gain-of-Function Mutation in CLCN6, Encoding the ClC-6 Cl-/H+-Exchanger, Causes Early-Onset Neurodegeneration. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020;107:1062–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y., Du X., Bin R., Yu S., Xia Z., Zheng G., Zhong J., Zhang Y., Jiang Y.H., Wang Y. Genetic Variants Identified from Epilepsy of Unknown Etiology in Chinese Children by Targeted Exome Sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:40319. doi: 10.1038/srep40319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He H., Cao X., Yin F., Wu T., Stauber T., Peng J. West Syndrome Caused By a Chloride/Proton Exchange-Uncoupling CLCN6 Mutation Related to Autophagic-Lysosomal Dysfunction. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021;58:2990–2999. doi: 10.1007/s12035-021-02291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasper D., Planells-Cases R., Fuhrmann J.C., Scheel O., Zeitz O., Ruether K., Schmitt A., Poët M., Steinfeld R., Schweizer M. Loss of the chloride channel ClC-7 leads to lysosomal storage disease and neurodegeneration. EMBO J. 2005;24:1079–1091. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kornak U., Kasper D., Bösl M.R., Kaiser E., Schweizer M., Schulz A., Friedrich W., Delling G., Jentsch T.J. Loss of the ClC-7 chloride channel leads to osteopetrosis in mice and man. Cell. 2001;104:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stobrawa S.M., Breiderhoff T., Takamori S., Engel D., Schweizer M., Zdebik A.A., Bösl M.R., Ruether K., Jahn H., Draguhn A. Disruption of ClC-3, a chloride channel expressed on synaptic vesicles, leads to a loss of the hippocampus. Neuron. 2001;29:185–196. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Günther W., Lüchow A., Cluzeaud F., Vandewalle A., Jentsch T.J. ClC-5, the chloride channel mutated in Dent’s disease, colocalizes with the proton pump in endocytotically active kidney cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:8075–8080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novarino G., Weinert S., Rickheit G., Jentsch T.J. Endosomal chloride-proton exchange rather than chloride conductance is crucial for renal endocytosis. Science. 2010;328:1398–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1188070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinberg B.E., Huynh K.K., Brodovitch A., Jabs S., Stauber T., Jentsch T.J., Grinstein S. A cation counterflux supports lysosomal acidification. J. Cell Biol. 2010;189:1171–1186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinert S., Jabs S., Supanchart C., Schweizer M., Gimber N., Richter M., Rademann J., Stauber T., Kornak U., Jentsch T.J. Lysosomal pathology and osteopetrosis upon loss of H+-driven lysosomal Cl- accumulation. Science. 2010;328:1401–1403. doi: 10.1126/science.1188072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wartosch L., Fuhrmann J.C., Schweizer M., Stauber T., Jentsch T.J. Lysosomal degradation of endocytosed proteins depends on the chloride transport protein ClC-7. FASEB J. 2009;23:4056–4068. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-130880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorenz C., Pusch M., Jentsch T.J. Heteromultimeric CLC chloride channels with novel properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:13362–13366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Stefano S., Pusch M., Zifarelli G. A single point mutation reveals gating of the human ClC-5 Cl-/H+ antiporter. J. Physiol. 2013;591:5879–5893. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.260240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arachchi H., Wojcik M.H., Weisburd B., Jacobsen J.O.B., Valkanas E., Baxter S., Byrne A.B., O’Donnell-Luria A.H., Haendel M., Smedley D. matchbox: An open-source tool for patient matching via the Matchmaker Exchange. Hum. Mutat. 2018;39:1827–1834. doi: 10.1002/humu.23655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Philippakis A.A., Azzariti D.R., Beltran S., Brookes A.J., Brownstein C.A., Brudno M., Brunner H.G., Buske O.J., Carey K., Doll C. The Matchmaker Exchange: a platform for rare disease gene discovery. Hum. Mutat. 2015;36:915–921. doi: 10.1002/humu.22858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobreira N., Schiettecatte F., Valle D., Hamosh A. GeneMatcher: a matching tool for connecting investigators with an interest in the same gene. Hum. Mutat. 2015;36:928–930. doi: 10.1002/humu.22844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmitz-Abe K., Li Q., Rosen S.M., Nori N., Madden J.A., Genetti C.A., Wojcik M.H., Ponnaluri S., Gubbels C.S., Picker J.D. Unique bioinformatic approach and comprehensive reanalysis improve diagnostic yield of clinical exomes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;27:1398–1405. doi: 10.1038/s41431-019-0401-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guzman R.E., Miranda-Laferte E., Franzen A., Fahlke C. Neuronal ClC-3 splice variants differ in subcellular localizations, but mediate identical transport functions. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:25851–25862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.668186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guzman R.E., Grieschat M., Fahlke C., Alekov A.K. ClC-3 is an intracellular chloride/proton exchanger with large voltage-dependent nonlinear capacitance. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013;4:994–1003. doi: 10.1021/cn400032z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rohrbough J., Nguyen H.N., Lamb F.S. Modulation of ClC-3 gating and proton/anion exchange by internal and external protons and the anion selectivity filter. J. Physiol. 2018;596:4091–4119. doi: 10.1113/JP276332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedrich T., Breiderhoff T., Jentsch T.J. Mutational analysis demonstrates that ClC-4 and ClC-5 directly mediate plasma membrane currents. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:896–902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Accardi A., Miller C. Secondary active transport mediated by a prokaryotic homologue of ClC Cl- channels. Nature. 2004;427:803–807. doi: 10.1038/nature02314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Capurro V., Gianotti A., Caci E., Ravazzolo R., Galietta L.J., Zegarra-Moran O. Functional analysis of acid-activated Cl− channels: properties and mechanisms of regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1848(1 Pt A):105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ullrich F., Blin S., Lazarow K., Daubitz T., von Kries J.P., Jentsch T.J. Identification of TMEM206 proteins as pore of PAORAC/ASOR acid-sensitive chloride channels. eLife. 2019;8:8. doi: 10.7554/eLife.49187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang J., Chen J., Del Carmen Vitery M., Osei-Owusu J., Chu J., Yu H., Sun S., Qiu Z. PAC, an evolutionarily conserved membrane protein, is a proton-activated chloride channel. Science. 2019;364:395–399. doi: 10.1126/science.aav9739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Veeramah K.R., Johnstone L., Karafet T.M., Wolf D., Sprissler R., Salogiannis J., Barth-Maron A., Greenberg M.E., Stuhlmann T., Weinert S. Exome sequencing reveals new causal mutations in children with epileptic encephalopathies. Epilepsia. 2013;54:1270–1281. doi: 10.1111/epi.12201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dickerson L.W., Bonthius D.J., Schutte B.C., Yang B., Barna T.J., Bailey M.C., Nehrke K., Williamson R.A., Lamb F.S. Altered GABAergic function accompanies hippocampal degeneration in mice lacking ClC-3 voltage-gated chloride channels. Brain Res. 2002;958:227–250. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03519-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshikawa M.U.S., Ezaki J., Rai T., Hayama A., Kobayashi K., Kida Y., Noda M., Koike M., Uchiyama Y., Marumo F. CLC-3 deficiency leads to phenotypes similar to human neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Genes Cells. 2002;7:597–605. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofman J., Hutny M., Sztuba K., Paprocka J. Corpus Callosum Agenesis: An Insight into the Etiology and Spectrum of Symptoms. Brain Sci. 2020;10:10. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10090625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howard H.C., Mount D.B., Rochefort D., Byun N., Dupré N., Lu J., Fan X., Song L., Rivière J.B., Prévost C. The K-Cl cotransporter KCC3 is mutant in a severe peripheral neuropathy associated with agenesis of the corpus callosum. Nat. Genet. 2002;32:384–392. doi: 10.1038/ng1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boettger T., Rust M.B., Maier H., Seidenbecher T., Schweizer M., Keating D.J., Faulhaber J., Ehmke H., Pfeffer C., Scheel O. Loss of K-Cl co-transporter KCC3 causes deafness, neurodegeneration and reduced seizure threshold. EMBO J. 2003;22:5422–5434. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shekarabi M., Moldrich R.X., Rasheed S., Salin-Cantegrel A., Laganière J., Rochefort D., Hince P., Huot K., Gaudet R., Kurniawan N. Loss of neuronal potassium/chloride cotransporter 3 (KCC3) is responsible for the degenerative phenotype in a conditional mouse model of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy associated with agenesis of the corpus callosum. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:3865–3876. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3679-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leisle L.L.C., Wagner F.A., Jentsch T.J., Stauber T. ClC-7 is a slowly voltage-gated 2Cl-/1H+-exchanger and requires Ostm1 for transport activity. EMBO J. 2011;30:2140–2152. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pusch M., Zifarelli G. Large transient capacitive currents in wild-type lysosomal Cl-/H+ antiporter ClC-7 and residual transport activity in the proton glutamate mutant E312A. J. Gen. Physiol. 2021;153:153. doi: 10.1085/jgp.202012583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith A.J., Lippiat J.D. Voltage-dependent charge movement associated with activation of the CLC-5 2Cl-/1H+ exchanger. FASEB J. 2010;24:3696–3705. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-150649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zifarelli G., De Stefano S., Zanardi I., Pusch M. On the mechanism of gating charge movement of ClC-5, a human Cl(-)/H(+) antiporter. Biophys. J. 2012;102:2060–2069. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.03.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ludwig C.F., Ullrich F., Leisle L., Stauber T., Jentsch T.J. Common gating of both CLC transporter subunits underlies voltage-dependent activation of the 2Cl-/1H+ exchanger ClC-7/Ostm1. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:28611–28619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.509364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robertson J.L., Kolmakova-Partensky L., Miller C. Design, function and structure of a monomeric ClC transporter. Nature. 2010;468:844–847. doi: 10.1038/nature09556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feng L., Campbell E.B., Hsiung Y., MacKinnon R. Structure of a eukaryotic CLC transporter defines an intermediate state in the transport cycle. Science. 2010;330:635–641. doi: 10.1126/science.1195230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao Z., Li X., Hao J., Winston J.H., Weinman S.A. The ClC-3 chloride transport protein traffics through the plasma membrane via interaction of an N-terminal dileucine cluster with clathrin. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:29022–29031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703506200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stauber T., Jentsch T.J. Sorting motifs of the endosomal/lysosomal CLC chloride transporters. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:34537–34548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.162545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hara-Chikuma M.Y.B., Sonawane N.D., Sasaki S., Uchida S., Verkman A.S. ClC-3 chloride channels facilitate endosomal acidification and chloride accumulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:1241–1247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishida Y., Nayak S., Mindell J.A., Grabe M. A model of lysosomal pH regulation. J. Gen. Physiol. 2013;141:705–720. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Astaburuaga R., Quintanar Haro O.D., Stauber T., Relógio A. A mathematical model of lysosomal ion homeostasis points to differential effects of Cl(-) transport in Ca(2+) dynamics. Cells. 2019;8:8. doi: 10.3390/cells8101263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li X., Wang T., Zhao Z., Weinman S.A. The ClC-3 chloride channel promotes acidification of lysosomes in CHO-K1 and Huh-7 cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C1483–C1491. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00504.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nicoli E.R., Weston M.R., Hackbarth M., Becerril A., Larson A., Zein W.M., Baker P.R., 2nd, Burke J.D., Dorward H., Davids M., Undiagnosed Diseases Network Lysosomal storage and albinism due to effects of a de novo CLCN7 variant on lysosomal acidification. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;104:1127–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data for all protein variants identified are publicly available on ClinVar. Data generated for the manuscript are available from the corresponding authors on request.