Abstract

Achieving sustained engagement in family-based preventive intervention programs is a serious challenge faced by program implementers. Despite the evidence supporting the effectiveness and potential population-level impacts for these programs, their actual impact is limited by challenges around retention of participants. In order to inform efforts to better retain families, it is critical to understand the different patterns of attendance that emerge across the duration of program implementation and the factors that are associated with each attendance pattern. In this study, we identified latent classes of attendance patterns across the seven program sessions of the Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth Ages 10-14 (SFP 10-14). Youth and their parents who attended at least one SFP 10-14 program session together were included in the analysis. Four distinct classes emerged: First-Session Attenders (7%), Early Attenders (9%), Declining-High Attenders (18%), and Consistent-High Attenders (66%). An examination of individual, family, and sociodemographic predictors of class membership revealed that adolescent school bonding predicted families having relatively high attendance, adolescent involvement with deviant peers predicted early dropout, and family low-income status predicted early dropout. Findings point to the need for potential targeted strategies for retaining these groups, such as involving school personnel, employing brief interventions to identify and address barriers at the outset, and leveraging the positive influence of Consistent-High Attenders. Findings also shed light on ways to reach those who may continue to drop out early, such as restructuring program content to address critical material early in the program. This study adds to the growing body of literature that seeks to understand for whom, when, and in which ways program dropout occurs.

Keywords: Family-based program, Attendance, Motivations, Barriers, Latent class analysis

INTRODUCTION

Despite their potential for population-level effects, universal family-based preventive intervention programs often suffer from low retention, making it challenging for them to have a substantial impact (Spoth & Redmond, 1995, 2000). Most programs are designed and tested under the assumption that they will be received in their entirety; however, as content varies across program sessions (LoBraico et al., 2019), program dropout threatens their overall potential effectiveness. Understanding how and why patterns of program attendance vary may inform efforts to better retain families in preventive intervention programs, and may also aid in the identification of alternative approaches to critical content delivery that may benefit families who leave the program prematurely (Coatsworth, Santisteban, McBride, & Szapocznik, 2001; Finan, Swierzbiolek, Priest, Warren, & Yap, 2018).

Participation choices in behavioral and physical health interventions have been a focus of study for several decades. Beyond the challenges around initial program engagement, programs also suffer from challenges concerning ongoing engagement, including attendance, as separate but related issues. A recent review revealed that 26% of parents who began a parenting-focused behavioral training program dropped out before completing it, and that attendance rates throughout the duration of programs were highly variable (Chacko et al., 2016). One framework for understanding participation decisions, the Health Belief Model, posits four key variables that determine someone’s likelihood of participating in a particular health behavior (Rosenstock, 1966). When applied to a parent’s decision to attend a program for their adolescent, they would be more likely to attend if they believed (1) their child was susceptible to the problem, (2) the problem was serious, (3) they would benefit from the program, and (4) they were able to participate (i.e., they would encounter only minimal barriers). This framework has been generally supported by empirical evidence and is reflected in many identified barriers and facilitators of initial and ongoing program engagement (Eisner & Meidert, 2011; Perrino et al., 2016; Spoth et al., 2000).

Key influences on program engagement can be organized across individual, family, and sociodemographic factors. While adolescent behavior problems (e.g., at school, with peers) may motivate some parents to attend programs because they perceive benefits from the program or are concerned their child is susceptible to the problem, adolescent problems may also impede attendance for other parents who see this as a barrier to participating (Brody et al., 2006). This complexity is reflected by the divergent findings in the literature. For instance, some studies have shown that families with higher rates of initial engagement have children with higher levels of behavior problems (e.g., externalizing; Mauricio et al., 2014). However, other studies have shown that families with youth problem behavior are less likely to consistently attend a family-based program (Brody et al., 2006). Features of the family are also associated with both initial and ongoing family-based program engagement. Poor family-level functioning, including tension, conflict, and disorganization, have been associated with lower initial and ongoing engagement (Bamberger et al., 2014; Eisner & Meidert, 2011). Lower parent-child relationship quality has been associated with more program engagement, reflecting parents’ motivation to improve their relationship with their youth (Coatsworth, Hemady, & George, 2018). Parenting skills, such as parental monitoring and knowledge, have been associated with less attendance in a web-delivered family-based program, perhaps indicating less perceived benefits of programming (Perrino et al., 2016), although these findings have not been replicated with in-person formats (e.g., Fleming et al., 2015). Practical barriers, such as scheduling challenges and transportation issues, are likely exacerbated for single-parent families and low-income families, as the demands faced by parents who manage their families as single parents and those with few financial resources may make prioritizing attendance to prevention programs challenging, regardless of other motivations (Coatsworth et al., 2017; Fleming et al., 2015).

Conceptualizing attendance as a pattern of behavior that may change throughout the course of a program rather than as a binary indicator (e.g., high or low attendance), or as a total count of sessions attended, is important to inform how and why different barriers and facilitators may shape attendance. Identification of patterns rather than grouping by high and low attendance also offers insight into heterogeneity in attendance across program sessions. Recently, work has explored this issue by identifying unobserved subgroups of participants with similar attendance patterns and describing people within those groups to better understand who is at risk for program dropout and when that may occur (Mauricio, Mazza, et al., 2018; Mauricio, Tein, Gonzales, Millsap, & Dumka, 2018; St. George et al., 2018). This information provides insight for program implementers to engage in proactive retention promotion strategies that incentivize continued participation and are personalized for specific subgroups with different patterns of attendance that may have unique risk factors for program dropout. Mauricio and colleagues have identified meaningful subgroups in attendance trajectories over the course of two family-based programs – the New Beginnings program, which targets effective parenting by divorced and separated mothers and fathers, and the Bridges to High School program, which targets school engagement (Mauricio, Mazza, et al., 2018; Mauricio, Tein, et al., 2018). St. George and colleagues (2018) identified latent classes of attendance patterns in a family-based obesity preventive intervention for Hispanic overweight and obese adolescents, the Familias Unidas for Health and Wellness intervention. Across these three studies and three programs, consistent attendance patterns emerged: (1) early dropouts, (2) mid-program dropouts/declining attenders, and (3) sustained attenders. The factors related to membership in each attendance subgroup were specific to the samples under study (e.g., lower degree of comfort with one’s Hispanic culture predicted attendance to Familias Unidas; St. George et al., 2018), reflecting the several motivations for different types of programs with various intervention targets and target populations. Our study attempts to fill the gap in the literature regarding prevalent patterns of attendance in other types of family-based preventive interventions that focus on families with different barriers and facilitators of attending and maintaining attendance. We focus on the Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth Ages 10-14 (SFP 10-14), a universal preventive intervention that targets adolescent substance use with content addressing effective parenting, family relationships, and adolescent behaviors and skills.

Our Study

We sought to (1) identify patterns of attendance to SFP 10-14 among families who initially engaged in the program, and (2) determine whether individual (i.e., conduct problem behaviors, deviant peer involvement, negative school bonding), family (i.e., family climate, parental knowledge, adolescent positive family engagement), and sociodemographic (i.e., single-parent status, low-income status) characteristics are related to attendance patterns. Based on prior similar analyses with different interventions, we expected to identify at least three latent classes: (1) consistent-high attenders, (2) early dropouts, and (3) late dropouts. Second, guided by earlier findings revealing that factors can be both barriers and motivators of attendance to interventions similar to SFP 10-14, we expected there to be differences among classes across individual, family, and sociodemographic factors. Specifically, we expected membership in: (a) the consistent-high attenders group to be predicted by lower risk across the family, individual, and sociodemographic factors, reflecting low perceived barriers to participating in the program; (b) the early dropout group to be predicted by higher sociodemographic risk and higher adolescent individual risk, reflecting high perceived participation barriers; and (c) the late dropout group to be predicted by higher family risk, reflecting perceived benefits of the program that might motivate initial attendance, but then also drive eventual dropout if the expected benefits were not experienced as the program progressed.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Data were from the community-randomized trial of the PROmoting School-community-university Partnerships to Enhance Resilience (PROSPER) preventive intervention program delivery system. The trial included 28 rural and semi-rural school districts in Pennsylvania and Iowa (for more details on the trial, see Spoth, Greenberg, Bierman, & Redmond, 2004). The fourteen communities in the intervention condition received the PROSPER-delivered family-based and school-based intervention programs during Grades 6 and 7, respectively, and the control condition implemented “programming as usual.” Community eligibility criteria for the trial were: (a) school district enrollment between 1300 and 5200 students, and (b) at least 15% of students eligible for free or reduced cost lunches (a measure used to identify level of socioeconomic status). Participants were two successive cohorts of sixth graders, beginning in the 2002-2003 school year. All research was conducted under the supervision of both the Iowa and Pennsylvania State Universities’ Institutional Review Boards.

Data were collected in classrooms during the Fall and Spring of Grade 6, followed by yearly assessments through Grade 12. A passive consent procedure for parents and an active assent procedure for youth allowed the adolescents to opt out of assessments. Assessments were self-report questionnaires which included questions about adolescents’ demographic information, families, peers, their own behaviors, and their attitudes and beliefs toward substance use. Of these data, our study uses only the Fall Grade 6 assessment. A total of 10,845 students (approximately 90% of those eligible) in the intervention and control communities completed the Fall Grade 6 assessment. After this initial assessment, families in the intervention condition (n = 5,515) were offered SFP 10-14 (Kumpfer et al., 1996). SFP 10-14 is a highly disseminated program that has been shown to reduce a host of adolescent problem behaviors and to improve parents’ family management skills and family climate (Spoth, Redmond, Mason, Schainker, & Borduin, 2015). School and community outlets, including classroom presentations, newsletters, parent-teacher conferences, and phone and mail invitations, were used to recruit families in the PROSPER intervention communities into SFP 10-14 (refer to Spoth, Clair, Greenberg, Redmond, & Shin, 2007 for details on these processes). Three facilitators delivered two-hour program sessions in community facilities for seven weekly meetings. Dinner and childcare were provided. Approximately 17% of intervention community families enrolled in SFP 10-14. Our analytic sample (N = 957) included families for whom an adolescent and parent together attended at least one SFP 10-14 program session. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. We compared families who attended SFP 10-14 across model predictors to those who did not attend. One significant difference emerged: those who attended SFP 10-14 were less likely to be single parents.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the analytic sample (N =957), attendance rates, and predictor variables.

| Variable | Mean (SD)/Frequency (Valid %) |

|---|---|

| Adolescent age | 11.8 (0.40) Min = 10.9, Max= 13.7 Missing = 212 |

| Adolescent gender | |

| Female | 432 (48.6%) |

| Male | 451 (50.7%) |

| Not sure | 6 (0.7%) |

| Missing | 8 |

| Adolescent race/ethnicity | |

| White | 700 (86.7%) |

| African American | 17 (1.9%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 39 (4.8%) |

| Asian | 1 (0.1%) |

| Native American | 16 (1.8%) |

| Other | 34 (3.8%) |

| Missing | 90 |

| Program attendance | |

| Session 1 | 768 (86%) |

| Session 2 | 744 (83%) |

| Session 3 | 698 (78%) |

| Session 4 | 659 (74%) |

| Session 5 | 620 (69%) |

| Session 6 | 597 (67%) |

| Session 7 | 630 (70%) |

| Predictor variables | |

| Individual factors | |

| Conduct problem behaviors | 1.13 (0.33) |

| Deviant peer involvement | 1.49 (0.79) |

| Negative school adjustment and bonding | 2.20 (0.73) |

| Family factors | |

| Family climate | 3.58 (0.75) |

| Adolescent positive engagement with the family | 4.31 (0.87) |

| Parental knowledge | 4.54 (0.64) |

| Sociodemographic factors | |

| Low income status | 251 (32%) |

| Single parent status | 155 (19%) |

Note. Low income status was measured with a proxy variable of eligibility from free or reduced-priced school lunch eligibility status.

Measures

Program attendance.

We calculated attendance as the attendance of one adolescent and one parent together at each program session.

Predictors of attendance.

Predictors were from the fall Grade 6 self-report assessment described above.

Individual factors.

Adolescents reported on three individual factors: conduct problem behaviors, antisocial peer behavior, and negative school adjustment and bonding. Conduct problem behaviors was measured with items from the National Youth Survey (Elliott et al., 1985). Adolescents responded to 12 items that asked them to report their conduct problem behaviors in the past year (e.g., “purposely damaged or destroyed property that did not belong to you”). The response scale ranged from 1 (Never) to 5 (5 or more times). The reliability of this scale was α=0.84. Adolescent deviant peer involvement was measured with three items that asked adolescents about the antisocial behaviors of their closest friends (e.g., “these friends sometimes break the law”; Spoth & Molgaard, 1999). The response scale ranged from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). The reliability of this scale was α=0.81. Negative school adjustment and bonding was measured with 5 items that asked adolescents about their negative attitudes toward and perceptions about school and their teachers (e.g., “I don’t feel like I really belong at school”). This scale was adapted from Simons, Whitbeck, Conger, and Conger (1991) and is consistent with negative aspects of other measures of student engagement (see Fredricks & McColskey, 2012). The response scale ranges from 1 (Never true) to 5 (Always true). The reliability of this scale was α=0.57.

Family factors.

Adolescents reported on three family factors: family climate, parental knowledge, and adolescent positive engagement in the family. Family climate was measured with items drawn from the Family Environment Scale (Moos & Moos, 1994). Adolescents reported on statements about family cohesion, conflict, and organization. An example item is “Family members really help and support one another.” The response scale ranged from 1 (Strongly agree) to 5 (Strongly disagree); the scale was scored so that higher values indicated more cohesion and organization, and less conflict. The reliability of this scale was α=0.73. Parental knowledge was measured with the child monitoring subscale of the General Child Management Scale (Spoth, Redmond, & Shin, 1998). Adolescents responded to four items about their parents’ knowledge of their behaviors and activities. The response scale ranged from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). An example item is “My parents know who I am with when I am away from home.” The reliability of this scale was α=0.74. Adolescent positive engagement with the family was measured with the Affective Quality of the Relationship Scale (AQRS; Spoth, Redmond, & Shin, 1998). Adolescents responded to three items about their expression of affective quality toward each parent in the past year. The response scale ranged from 1 (Never or almost never) to 5 (Always or almost always). We averaged the six items for each adolescent to yield a positive engagement score. An example item asks “When you and your [father/mother] have spent time talking or doing things together, how often did you let [him/her] know you really care about [him/her]?” The reliability of this scale was α=0.90.

Sociodemographic factors.

Adolescents reported on two sociodemographic factors. Household single-parent status was measured with one item that asked “Who do you live with most of the year?” Youth who responded “Mother only” or “Father only” were coded as having a single-parent household status (0 = No, 1 = Yes). Low income status was measured with a proxy item that asked “What do you usually do for lunch on school days?” Youth who either responded “I receive free lunch from school” or “I buy my lunch at school at a reduced price” were coded as eligible free/reduced price lunch (0 = No, 1 = Yes).

Analysis Plan

We identified and described latent classes of SFP 10-14 attendance patterns using repeated measures latent class analysis (RMLCA; Collins & Lanza, 2010; Lanza & Collins, 2006). RMLCA identifies latent classes characterized by patterns of categorical changes (in program attendance) over three or more times (out of a total of seven program sessions). We selected the model using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), sample-size adjusted BIC (a-BIC), entropy, and a bootstrapped likelihood ratio test, as well as model stability and interpretability. We checked maximum likelihood estimate identification for all models with 1,000 initial stage starts and 500 final stage starts. Next, we examined whether prevalence rates of class membership differed based on the subsets of domain-specific predictors, including individual, family, and sociodemographic factors. Finally, we ran a final model including all significant predictors simultaneously in order to determine which factors were most relevant to attendance class membership. We added predictors using baseline-category multinomial logistic regression based on modal class assignment with classification-error correction (Vermunt, 2010; R3STEP command in Mplus). We used full-information maximum likelihood estimation to handle missing data for these predictor analyses. We adjusted the standard errors in all models to account for clustering at the community level; we estimated all models using Mplus version 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2019).

Results

Model fit information and selection criteria are displayed in Table 2. We considered models with 1-6 classes; the AIC minimized at the 5-class solution, the BIC minimized at the 3-class solution, and the a-BIC minimized at the 4-class solution. Entropy ranged from 0.70 to 0.93, with values for larger models in the lower .70s. Additionally, the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test became insignificant at the 6-class model, indicating that the addition of a sixth class did not provide additional information. Further examination of the 5-class model indicated one class that was not theoretically distinct from another in the model, offering evidence of overextraction. The 4-class model included four distinct, stable, and interpretable classes. We selected the 4-profile model for theoretical interpretation and additional analysis.

Table 2.

Model fit indices for models with 1-6 classes (n=897).

| No. of classes |

Log- likelihood |

No. of free parameters |

AIC | BIC | a-BIC | Entropy | BLRT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −3445.111 | 7 | 6904.222 | 6937.815 | 6915.585 | -- | -- |

| 2 | −2840.100 | 15 | 5710.199 | 5782.185 | 5734.548 | .93 | p <.001 |

| 3 | −2785.234 | 23 | 5616.469 | 5726.847 | 5653.803 | .84 | p <.001 |

| 4 | −2761.268 | 31 | 5584.535 | 5733.306 | 5634.855 | .87 | p <.001 |

| 5 | −2750.473 | 39 | 5578.946 | 5766.110 | 5642.252 | .70 | p < .001 |

| 6 | −2744.256 | 47 | 5582.513 | 5808.068 | 5658.804 | .72 | p = .65 |

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; a-BIC = sample size adjusted BIC; BLRT = Bootstrapped likelihood ratio test. Dashes indicate criterion was not applicable; bold indicates selected model.

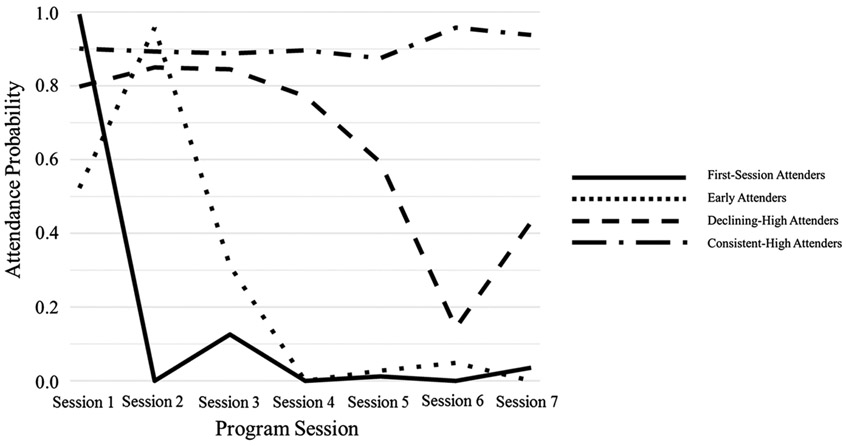

Parameter estimates for the RMLCA are presented in Table 3. Class 1 (7% prevalence) had a high probability of attending the first program session (0.99) and low probabilities of attending additional sessions (e.g., 0.00 for Session 2, 0.13 for Session 3); we labeled this class First-Session Attenders. Class 2 (9% prevalence) had moderate to high probabilities of attending the first two sessions and low and declining probabilities of attending additional sessions; we labeled this class Early Attenders. Class 3 (18% prevalence) had high probabilities of attending the first four sessions followed by moderate and declining probabilities of attending the final 3 sessions; we labeled this class Declining-High Attenders. Class 4 (66% prevalence) had high probabilities of attending all seven program sessions; we labeled this fourth class Consistent-High Attenders. See Figure 1 for a visual depiction of these four classes.

Table 3.

Probabilities of SFP 10-14 program attendance by latent class (N=957).

| Class (Prevalence) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Session Attenders (7%) |

Early Attenders (9%) | Declining-High Attenders (18%) |

Consistent-High Attenders (66%) |

|

| Session 1 | 0.99 | 0.52 | 0.80 | 0.90 |

| Session 2 | 0.00 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 0.89 |

| Session 3 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 0.85 | 0.89 |

| Session 4 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.77 | 0.90 |

| Session 5 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.59 | 0.88 |

| Session 6 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.96 |

| Session 7 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.94 |

Figure 1.

Latent classes of patterns of family attendance to SFP 10-14.

Next, we examined predictors of attendance class membership by each domain separately (results not shown). Among the individual factors, we found evidence of significant pairwise comparisons for adolescent deviant peer involvement and negative school adjustment and bonding, and a trend (p =.07) in comparisons for conduct problem behaviors. Among the family factors, pairwise comparisons were only significant for family climate, and among the sociodemographic factors, pairwise comparisons were only significant for low-income status. We thus only retained these individual, family, and sociodemographic predictors in the final model.

Results from the final predictor analysis model are displayed in Table 4 as multinomial regression coefficients and their corresponding odds ratios. Effects of predictors on class membership are expressed as odds ratios describing the increase (> 1) or decrease (< 1) in odds of membership in a particular profile compared to the reference profile. Negative school adjustment and bonding, adolescent deviant peers, and low-income status were robustly related to attendance: controlling for the other factors, (a) families with adolescents who engaged with peers who were more deviant were more likely to be Early Attenders than Consistent-High Attenders and Declining-High Attenders, (b) families with adolescents who experienced more negative school adjustment and bonding were more likely to be Declining-High Attenders than any other type and also were less likely to be Early Attenders than Consistent-High Attenders, and (c) low-income families were more likely than non-low-income families to be First-Session Attenders than Consistent-High Attenders.

Table 4.

Effects of predictors on program attendance class membership.

| Predictor | 1. First-Session Attenders |

2. Early Attenders |

3. Declining- High Attenders |

4. Consistent- High Attenders |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (Odds Ratios) | ||||

| Conduct problem behaviors | 0.63 (1.88) | −1.54 (0.22) | −0.07 (0.94) | -- |

| Deviant peer involvement | 0.09 (1.09) | 0.55* (1.74) | −0.03 (1.03) | -- |

| Negative school adjustment and bonding | −0.34 (0.71) | −0.45* (0.64) | 0.34* (1.41) | -- |

| Family climate | −0.44 (0.65) | 0.06 (1.06) | −0.34 (0.71) | -- |

| Low income status | 0.96* (2.62) | 0.65 (1.91) | 0.54 (1.72) | -- |

| Conduct problem behaviors | 0.70 (2.01) | −1.47 (0.23) | -- | 0.07 (1.07) |

| Deviant peer involvement | 0.06 (1.06) | 0.53* (1.69) | -- | −0.03 (0.97) |

| Negative school adjustment and bonding | −0.68* (0.51) | −0.79* (0.46) | -- | −0.34* (0.71) |

| Family climate | −0.10 (0.91) | 0.40 (1.49) | -- | 0.34 (1.40) |

| Low income status | 0.42 (1.52) | 0.10 (1.11) | -- | −0.54 (0.58) |

Note. Dashes indicate the reference class.

p < .05.

Discussion

We identified four distinct subgroups of SFP 10-14 attendance patterns and assessed individual, family, and sociodemographic factors as predictors of belonging to each subgroup. Similar to the findings for other prevention programs described earlier, we identified a group with consistently high attendance (“Consistent-High Attenders”), a group whose attendance declined during the program (“Declining-High Attenders”), and a group that dropped out of the program early on (Mauricio, Mazza, et al., 2018; Mauricio, Tein, et al., 2018; St. George et al., 2018). A key difference between the current study and past work was the emergence of two, instead of one, distinct groups that are characterized by early dropout: First-Session Attenders reflected a group who attended one session prior to dropping out and Early Attenders reflected a group who attended the second session (some without attending the first session or third session), prior to dropping out. Given our sample size, our detection of more classes than prior similar studies with smaller sample sizes was not surprising.

Our predictor analyses offer new contributions to the literature on multi-session universal family-based programs by indicating certain key areas on which to focus to improve potential retention efforts for specific subgroups of families. First, adolescent negative school adjustment and bonding may motivate the initially sustained attendance of the Declining-High Attenders. This group shows consistent, high attendance probabilities for the initial sessions of the program, followed by low likelihood to attend the last three sessions. This group may be responsive to practitioner-led retention efforts, as it appears they are uniquely motivated to attend the program as compared to other drop-out groups. Perhaps these families are particularly motivated to attend programs because they are concerned that their youth lack connection to and enjoyment from school and their relationships at the school. If these concerns are a primary motivating factor, programs might consider providing additional support addressing school bonding outside of session time, such as incorporating elements of the school during the dinner (e.g., having teachers present). And, although this study did not assess program recruitment, families with adolescents who experience negative school adjustment and bonding might be a key group to target for recruitment, given their capacity to be fully engaged for much of the program.

Second, adolescents’ deviant peer involvement emerged as a key predictor of being Early Attenders compared to the two high attenders groups. Compared to Declining High-Attenders, Early Attenders may be more proximally approaching risk for substance use. Parents in this group may be particularly motivated by the perceived susceptibility of their adolescents to use substances given the risky behaviors in which their adolescents engage in deviant peer contexts (Rosenstock, 1966; Van Ryzin, Fosco, & Dishion, 2012). To retain Early Attenders, program implementers may focus on providing an especially warm welcome when they attend session two, as for many this is their first or last session. Implementers should also consider supplementing the programming with an overview of the previous session prior to session two and facilitating an activity to establish cohesion for this larger group that includes those who did not attend the previous session. These brief activities may be designed to take place during group check-in conversations before sessions begin, avoiding fidelity violations.

Third, low-income status emerged as a key differentiating factor between First-Session Attenders and the high attendance groups. This finding indicates that there is a small but meaningful group of people who are motivated enough to initially attend the program, but who are at a high risk of not returning. Given their low-income status, perhaps programs should focus more resources toward reducing barriers for these families’ attendance. Low-income parents cite lack of time, scheduling conflicts, and experiencing too much stress as the most common reasons for dropping out of parent groups (Gross et al., 2001). Although many programs, including SFP 10-14, offer childcare and dinner for all participants, there may be more that can be offered to further reduce barriers. For instance, some programs have found success by simply offering cash as an incentive to program attendance (Gross & Bettencourt, 2019). Another strategy involves brief verbal interventions for motivating parent participation and may help low-income families remain engaged by addressing their unique barriers at the outset (Nock & Kazdin, 2005).

Barring a reduction in the quantity of First-Session Attenders and Early Attenders through retention strategies, programs should offer resources to all families early on in the intervention. Though not significant in the overall test, the initial individual domain models indicated that these two groups are at somewhat elevated risk for problems that are targeted by SFP 10-14 (i.e., conduct problem behaviors, antisocial peer association, poor family climate). By offering all families additional resources (i.e., referrals) at the beginning of the program, even those who drop out early may be able to benefit from the goals of the program in this more distal way. Others have suggested altering content sequencing by presenting an overview of key material in the initial program sessions (Coatsworth et al., 2006).

One resource for retention might be to leverage the Consistent-High Attenders group’s commitment to the program to promote engagement for the others in their SFP 10-14 group. Strategies might include external contact (e.g., social network sites; Yang, 2017) in which parents maintain relationships across the weeks of the program. Although a handful of studies have examined this approach to improve engagement in online parenting programs, to date we are not aware of any which have examined this strategy with face-to-face program attendance (Epstein et al., 2019; Love et al., 2016).

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations to our study. First, we were unable to run a multilevel model to evaluate community-level predictors of attendance patterns because of limits to statistical power. Future studies should consider the greater community context, such as community readiness and community-level risk, when considering barriers to ongoing program engagement. Second, we did not study attendance change processes; studies with data available between program sessions should include the predictors of attendance to each session to better understand why and how each occur. Third, our measure of negative school adjustment and bonding had lower than optimal reliability, warranting cautious interpretation of results. Fourth, the data we used in these analyses date from 2002-2003. However, SFP 10-14 is currently implemented in the same manner as it was in this trial; thus, we have no reason to believe that patterns of attendance or predictors of patterns would have differed in a more recent trial. Lastly, our sample was rural and semi-rural with families that were predominantly White, potentially limiting generalizability.

Conclusion

We used RMLCA to identify latent classes of attendance among 957 parents and adolescents who attended at least one of seven sessions of SFP 10-14. Four latent classes emerged: First-Session Attenders (7%), Early Attenders (9%), Declining-High Attenders (18%), and Consistent-High Attenders (66%). Adolescent negative school adjustment and bonding, engagement with deviant peers, and family low-income status were key predictors of attendance patterns. The findings from this study offer targets for practitioners in their efforts to retain families in multi-session programs, particularly those with adolescents with low school engagement, low-income status, and adolescents engaging with deviant peers.

Grant Support

This study was funded by grant R01-DA013709 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and co-funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Authors were supported by several funding sources: The National Institute on Drug Abuse (LoBraico: F31-DA048522; Bray: P50 DA039838), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Fosco & Feinberg: R01 HD092439). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Compliance With Ethical Standards

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- Bamberger KT, Coatsworth JD, Fosco GM, & Ram N (2014). Change in participant engagement during a family-based preventive intervention: Ups and downs with time and tension. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(6), 811–820. 10.1037/fam0000036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Chen Y, Kogan SM, & Brown AC (2006). Effects of family risk factors on dosage and efficacy of a family-centered preventive intervention for rural African Americans. Prevention Science, 7(3), 281–291. 10.1007/s11121-006-0032-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacko A, Jensen SA, Lowry LS, Cornwell M, Chimklis A, Chan E, Lee D, & Pulgarin B (2016). Engagement in behavioral parent training: Review of the literature and implications for practice. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19(3), 204–215. 10.1007/s10567-016-0205-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth DJ, Santisteban DA, McBride CK, & Szapocznik J (2001). Brief strategic family therapy versus community control: Engagement, retention, and an exploration of the moderating role of adolescent symptom severity. Family Process, 40(3), 313–332. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4030100313.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Duncan LG, Pantin H, & Szapocznik J (2006). Patterns of retention in a preventive intervention with ethnic minority families. Journal of Primary Prevention, 27(2), 171–193. 10.1007/s10935-005-0028-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Hemady KT, & George MW (2017). Predictors of group leaders’ perceptions of parents’ initial and dynamic engagement in a family preventive intervention. Prevention Science. 10.1007/s11121-017-0781-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Hemady KT, & George MW (2018). Predictors of group leaders’ perceptions of parents’ initial and dynamic engagement in a family preventive intervention. Prevention Science, 19(5), 609–619. 10.1007/s11121-017-0781-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner M, & Meidert U (2011). Stages of parental engagement in a universal parent training program. Journal of Primary Prevention, 32(2), 83–93. 10.1007/s10935-011-0238-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, & Ageton SS (1985). Explaining Delinquency and Drug Use. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M, Oesterle S, & Haggerty KP (2019). Effectiveness of Facebook groups to boost participation in a parenting intervention. Prevention Science, 20(6), 894–903. 10.1007/s11121-019-01018-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan SJ, Swierzbiolek B, Priest N, Warren N, & Yap M (2018). Parental engagement in preventive parenting programs for child mental health: A systematic review of predictors and strategies to increase engagement. PeerJ, 2018(4). 10.7717/peerj.4676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, Mason WA, Haggerty KP, Thompson RW, Fernandez K, Casey-Goldstein M, & Oats RG (2015). Predictors of participation in parenting workshops for improving adolescent behavioral and mental health: Results from the Common Sense Parenting Trial. Journal of Primary Prevention, 36(2), 105–118. 10.1007/s10935-015-0386-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks J, & McColskey W (2012). The measurement of student engagement: A comparative analysis of various methods and student self-report instruments. In Christenson SL, Wylie C, & Reschly AL (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (pp. 763–782). Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, & Bettencourt AF (2019). Financial incentives for promoting participation in a school-based parenting program in low-income communities. Prevention Science, 20(4), 585–597. 10.1007/s11121-019-0977-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Julion W, & Fogg L (2001). What motivates participation and dropout among low-income urban families of color in a prevention intervention? Family Relations, 50(3), 246–254. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2001.00246.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Molgaard V, & Spoth R (1996). The Strengthening Families Program for the prevention of delinquency and drug use. In Peters RD & McMahon RJ (Eds.), Preventing Childhood Disorders, Substance Abuse, and Delinquency (pp. 241–267). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, & Collins LM (2006). A mixture model of discontinuous development in heavy drinking from ages 18 to 30: The role of college enrollment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67(4), 552–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoBraico EJ, Crowley DM, Spoth RL, Fosco GM, Feinberg ME, & Redmond C (2019). Examining intervention component dosage effects on substance use initiation in the Strengthening Families Program: for Parents and Youth Ages 10–14. Prevention Science. 10.1007/s11121-019-00994-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love SM, Sanders MR, Turner KMT, Maurange M, Knott T, Prinz R, Metzler C, & Ainsworth AT (2016). Social media and gamification: Engaging vulnerable parents in an online evidence-based parenting program. Child Abuse and Neglect, 53(2016), 95–107. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauricio AM, Mazza GL, Berkel C, Tein JY, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, & Winslow E (2018). Attendance trajectory classes among divorced and separated mothers and fathers in the New Beginnings Program. Prevention Science, 19(5), 620–629. 10.1007/s11121-017-0783-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauricio AM, Tein JY, Gonzales NA, Millsap RE, & Dumka LE (2018). Attendance patterns and links to non-response on child report of internalizing among Mexican-Americans randomized to a universal preventive intervention. Prevention Science, 19, 27–37. 10.1007/s11121-016-0632-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauricio AM, Tein JY, Gonzales NA, Millsap RE, Dumka LE, & Berkel C (2014). Participation patterns among Mexican–American parents enrolled in a universal intervention and their association with child externalizing outcomes. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(3–4), 370–383. 10.1007/s10464-014-9680-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos R, & Moos B (1994). Family Environment Scale Manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (n.d.). Mplus User’s Guide Eighth Edition. Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, & Kazdin AE (2005). Randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for increasing participation in parent management training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 872–879. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Estrada Y, Huang S, St. George S, Pantin H, Cano MÁ, Lee TK, & Prado G (2016). Predictors of participation in an eHealth, family-based preventive intervention for Hispanic youth. Prevention Science, 1–12. 10.1007/s11121-016-0711-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock IM (1966). Why people use health services. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 83(44), 94–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Whitbeck LB, Conger RD, Conger KJ, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB, Conger RD, & Conger KJ (1991). Parenting factors, social skills, and value commitments as precursors to school failure, involvement with deviant peers, and deliquent behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 20(6), 645–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth RL, Greenberg MT, Bierman KL, & Redmond C (2004). PROSPER community-university partnership model for public education systems: Capacity-building for evidence-based, competence-building prevention. Prevention Science, 5(1), 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, & Molgaard V (1999). Project Family: A partnership in integrating rsearch with the practice of promoting family and youth competencies. In Chibucos TR & Lerner R (Eds.), Serving children and families through community-university partnerships: Sucess sotires (pp. 127–137). Kluwer Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Mason WA, Schainker L, & Borduin L (2015). Research on the Strengthening Families Program for Parents and Youth Ages 10– 14: Long-term effects, mechanisms, translation to public health, PROSPER partnership scale up. In Scheier LM (Ed.), Handbook of Adolescent Drug use Prevention: Research, Intervention Strategies, and Practice. (2nd ed., pp. 267–292). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Spoth Richard, Clair S, Greenberg M, Redmond C, & Shin C (2007). Toward dissemination of evidence-based family interventions: Maintenance of community-based partnership recruitment results and associated factors. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(2), 137–146. 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth Richard, Redmond C, & Shin C (2000). Modeling factors influencing enrollment in family-focused preventive intervention research. Prevention Science, 1(4), 213–225. 10.1023/A:1026551229118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. George SM, Petrova M, Lee TK, Sardinas KM, Kobayashi MA, Messiah SE, & Prado G (2018). Predictors of participant attendance patterns in a family-based intervention for overweight and obese hispanic adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(7). 10.3390/ijerph15071482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, Fosco GM, & Dishion TJ (2012). Family and peer predictors of substance use from early adolescence to early adulthood: An 11-year prospective analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 37(12), 1314–1324. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK (2010). Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis, 18(4), 450–469. 10.1093/pan/mpq025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q (2017). Are social networking sites making health behavior change interventions more effective? A meta-analytic review. Journal of Health Communication, 22(3), 223–233. 10.1080/10810730.2016.1271065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]