Abstract

The respiratory tract is constantly exposed to various airborne pathogens. Most vaccines against respiratory infections are designed for the parenteral routes of administration; consequently, they provide relatively minimal protection in the respiratory tract. A vaccination strategy that aims to induce the protective mucosal immune responses in the airway is urgently needed. The FcRn mediates IgG Ab transport across the epithelial cells lining the respiratory tract. By mimicking this natural IgG transfer, we tested whether FcRn delivers vaccine antigens to induce a protective immunity to respiratory infections. In this study, we designed a monomeric IgG Fc fused to influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) antigen with a trimerization domain. The soluble trimeric HA-Fc were characterized by their binding with conformation-dependent HA Abs or FcRn. In wild type but not FcRn-knockout mice, intranasal (i.n.) immunization with HA-Fc plus CpG adjuvant conferred significant protection against lethal i.n. challenge with influenza A/PR/8/34 virus. Further, mice immunized with a mutant HA-Fc lacking FcRn binding sites or HA alone succumbed to lethal infection. Protection was attributed to high levels of neutralizing Abs, robust and long-lasting B- and T-cell responses, the presence of lung-resident memory T cells and bone marrow plasma cells, and a remarkable reduction of virus-induced lung inflammation. Our results demonstrate for the first time that FcRn can effectively deliver a trimeric viral vaccine antigen in the respiratory tract and elicit potent protection against respiratory infection. This study further supports a view that FcRn-mediated mucosal immunization is a platform for vaccine delivery against common respiratory pathogens.

Introduction

The respiratory tract is a common site for pathogen exposure. The respiratory tract can resist infection and facilitate the clearance of invading pathogens through a variety of mechanisms, including the airway barrier of polarized epithelial cells and various innate or adaptive immune responses (1, 2). Adaptive immunity, including effector and memory T or B lymphocytes and local and circulating Abs, can prevent infections or decrease the severity of subsequent respiratory infections (3, 4). For example, tissue-resident memory (TRM) T cells that reside in the lung are a recently appreciated subset of memory T cells and are required for optimal protection against previously encountered pathogens (5-7). Presently, most vaccines against respiratory infections are designed for delivery via parenteral routes including the muscle or skin, for intended protection of the lung. However, non-mucosal delivery routes elicit relatively poor mucosal immune responses in the respiratory tract, even though they often induce robust systemic immunity (8-11). A partial reason for the failure of systemic vaccination is the lack of strong mucosal Ab and cell-mediated immunity, including TRM T cells that reside in the lung tissue and their availability in the event of pathogen exposure. To prevent respiratory infections, an ideal way is to develop a mucosal vaccine that mimics natural respiratory infections and engenders beneficial lung immunity. This goal is best achieved by direct administration of vaccines via the respiratory route (12, 13). However, our ability to deliver vaccine antigens safely and effectively across the respiratory mucosal barrier is limited. Mucosal vaccines must avoid inducing excessively robust inflammatory responses that may lead to lung damage and exacerbate chronic diseases such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Since respiratory infections are more prevalent in young and elderly individuals, certain types of mucosal vaccines such as live attenuated vaccines are not preferred for these vulnerable populations. Given the high impact of respiratory infections on public health, developing safe and effective mucosal vaccines is an urgent, unmet need (12).

Epithelial monolayers lining the respiratory, intestinal, and genital tracts, as well as the placenta, polarize into the apical and basolateral plasma membrane domains, which are separated by intercellular tight junctions. The neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) is expressed in these epithelial monolayers and mediates the transfer of IgG Ab across the epithelium (14-16). By IgG transcytosis, FcRn provides a line of humoral defense at mucosal surfaces (16, 17-19), in addition to transferring maternal immunity to neonates. A hallmark of FcRn is its interaction with IgG Ab in a pH-dependent manner, binding IgG at acidic pH (6.0 – 6.5) and releasing IgG at neutral or higher pH (20). FcRn primarily resides within low pH endosomes and binds IgG through the Fc region. Normally, IgG enters epithelial cells via pinocytotic vesicles that fuse with acidic endosomes. IgG bound to FcRn then enters a non-degradative vesicular transport pathway within epithelial cells. Bound IgG is transported to the apical or basolateral surface and released into the lumen or submucosa upon physiological pH (21). Evidence of IgG transport across the respiratory epithelia by FcRn suggest that FcRn might also transport a vaccine antigen, if fused with the Fc portion of IgG, across the respiratory mucosal barrier. Our previous studies showed that FcRn can induce protective genital immunity by efficiently transporting herpes simplex virus gD or HIV-1 gag antigens across epithelial barrier (22, 23).

To test the possibility that FcRn can elicit a protective immunity to respiratory infections, we used the influenza A virus as a model pathogen. The hemagglutinin (HA) primarily mediates interactions of influenza virions with cell surface sialic acid residue receptors. After binding, virions are internalized through endocytic pathways to infect epithelial cells. The HA protein consists of the membrane-distal immunodominant globular head domain and the membrane-proximal HA stalk domain. The head domain shows high structural plasticity which is strongly affected by antigenic drift; in contrast, the stalk domain exhibits a high degree of conservation. The HA plays a critical role in the early steps of viral infection and elicits both humoral and cellular immunity (24). In this study, we determined the ability of FcRn to deliver the viral HA protein fused to an Fc region of IgG across the respiratory epithelial barrier. We defined protective immune responses and mechanisms relevant to this route for mucosal vaccination in the lung in a mouse model. Our data suggest that FcRn-mediated intranasal delivery of influenza virus HA antigen induces high levels of long-lasting Ab and T-cell responses, including TRM T cells in the lung, to provide potent protection against lethal influenza virus challenge. Our data demonstrate that FcRn-targeted delivery of an influenza virus vaccine antigen in the respiratory tract comprises an effective vaccine strategy and may be developed as a universal influenza vaccine against seasonal infection or for protection against pandemic influenza viruses or other common respiratory infections.

Materials and Methods

Cells, Abs, and virus.

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were purchased from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC). MDCK cells were maintained in Opti-MEM complete medium (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and CHO cells were maintained in complete Dulbecco's Minimal Essential Medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen Life Technologies), both supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, nonessential amino acids, and penicillin (100 units/ml)/streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Recombinant CHO cells were grown in a complete medium with G418 (500 μg/ml). All cells were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2. Influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/34/H1N1 (PR8) virus was provided by Dr. Peter Palese (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai) and was amplified in 10-to 11-day-old embryonated chicken eggs and titrated by 50% endpoint dilution assay. The horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin and anti-mouse IgG, IgG1, IgG2b and IgG2c were obtained from Southern Biotech (Birmingham, Alabama). HA Abs were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). HA stalk specific mAb KB2, 6F12, FI6v3, CR6261, and CR8020 were provided by Dr. Florian Krammer (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai) and Dr. Jeffrey Boyington (National Institutes of Health). Anti HA antibody (RA5-22, mouse IgG1,) was purchased from Santa Cruz (SC-52025). HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG2a (1080-05), HRP--conjugated rat anti-mouse IgG1 (1144-05) were from Southern Biotech. Recombinant HA was purchased from Sino Biologicals (Shanghai, China) or from Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources Repository (NR-19240, BEI Resources, Manassas, VA). HIV gp120 specific IgG mAb B12 was also from BEI.

Construction of influenza virus HA-Fc expression plasmids

To make an IgG Fc fusion protein, a pCDNA3 plasmid encoding the hinge, CH2, and CH3 domains of mouse IgG2a Fc (22) served as a template for the Fc fragment. The rationale for using IgG2a is that it has the highest affinity for activating FcγRI, but the lowest affinity for FcγRIIB. In IgG2a Fc, the Glu318, Lys320, and Lys322 residues were replaced with Ala residues to remove the complement C1q binding site (25). In addition, to produce a mutant form of IgG Fc protein that cannot bind to FcRn, the His310/Gln311 (HQ) and His433/Asn434 (HN) residues were changed to Ala310/Asp311 (AD) and Ala433/Gln434 (AQ) residues, respectively, to eliminate FcRn binding sites (26).

To generate a trimeric HA that is fused to the Fc, we first converted the Cys224, Cys227, and Cys229 residues to Ser residues within the Fc using a DNA mutagenesis kit (Clontech), resulting in a monomeric Fc fragment. To make a trimeric HA-Fc fusion gene, the extracellular portion of PR8 HA, excluding the signal peptide sequence, was amplified by PCR from a plasmid containing full-length PR8 HA using the primer pair (5’-GGATCAGGCGGGGGTGGGTCCGGAGGAGGTGGCTCGGGATCTGACA CAATATGTATAGGCTACCATGC-3’ 5’-CCTCTGGGCACCAGGCTTCTTGATCCTGAGCCT GATCCCTGATAGATCCCCATTGATTCC-3’). The IgG Fc antisense primer and the HA sense primer contain complementary glycine and serine codons to produce a 14GS linker to bridge the IgG Fc and HA fragments. A protein trimerization domain was amplified from a plasmid containing the T4 fibritin foldon sequence (27). Similarly, the HA antisense primer and the foldon sense primer contain complementary glycine and serine codons to introduce a 6GS linker between the HA and foldon fragments. The Fc, HA, and foldon fragments were fused by overlapping PCR and ligated into the pCDNA3 vector. All the resultant plasmids were confirmed by double-stranded DNA sequencing to verify the fidelity of PCR amplification and DNA cloning.

SDS-PAGE gel and Western blotting

Protein concentration and quality were assessed by 8-12% SDS-PAGE gel under reducing and non-reducing conditions. Protein in gels was either stained with Coomassie blue dye or used for transferring onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell). The membranes were blocked with 5% milk in PBST (PBS and 0.05% Tween-20) and incubated overnight with anti-IgG2a-HRP (1:10,000) or anti-HA Abs (1:2000). For HA probing, membranes were further incubated with the anti-mouse IgG1-HRP Ab (1:5,000) for 2 hr. SuperSignal West Pico PLUS ECL substrate (Thermo Fisher) was used to visualize protein in membranes and images were developed and captured by the Chemi Doc XRS system (BioRad).

Expression and characterization of HA-Fc fusion proteins

The different HA-Fc plasmids were transfected into CHO cells using PolyJet reagent (SignaGen). Stable cell lines were selected and maintained under G418 (0.5-1 mg/ml). Expression and secretion of HA-Fc fusion proteins were determined by immunofluorescence assay, SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting analysis. The soluble HA-Fc proteins were produced by culturing CHO cells in a complete medium containing 5% FBS with ultra-low IgG. The proteins were purified by Protein A column (Thermo Scientific) for the HA-Fc/wt protein and anti-mouse IgG (Rockland) conjugated agarose beads for the HA-Fc/mut protein. Protein concentrations were determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific).

The trimerization of HA-Fc was determined by the bis [sulfosuccinimidyl] suberate (BS3, Thermo Scientific) cross-linker method. Briefly, HA-Fc proteins (0.1 mg) were incubated with BS3 in 50-fold molar excess for 2 hr on ice. The reaction was then quenched by adding 1M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 to a final concentration of 50 mM Tris-HCl and further incubated for 15 min at room temperature. The protein samples were subjected to electrophoresis and subsequently analyzed by Western blotting analysis with anti-HA and anti-IgG2a Abs in Western blotting.

FcRn binding assay

An FcRn binding assay was performed. CHO cells were either transfected with plasmids expressing mouse FcRn and β2m or mock-transfected. 24 hr later, the transfected cells were seeded in a 6-well plate for 6 hr. Cells were subsequently equilibrated with medium under either pH 6.0 or pH 7.4 condition at 4°C for 30 min, then 3 μg trimeric HA-Fc/wt, HA-Fc/mut, or HA were added into each well or left untreated for 1 hr. The cells were washed with a corresponding pH buffer to remove the unbound proteins. The cells were finally lysed in cold PBS (pH 6.0 or 7.4) with 0.5% CHAPS (Sigma-Aldrich) and protease inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem) mixture on ice for 1 hr. The soluble proteins (10 μg) were subjected to Western blot analysis and blotted with biotin-labeled anti-HA primary Ab and Streptavidin-HRP-conjugated secondary Ab.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

SPR analysis of affinity between mouse FcRn and trimeric HA-Fc/wt was performed by the ACROBiosystems (Newark, Delaware, USA). In brief, the purified recombinant FcRn was diluted to 1 μg/mL with 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5) and was immobilized onto a CM5 biosensor chip (Biacore, Uppsala, Sweden) using an amine coupling kit (Biacore). The activator is prepared by mixing 400 mM 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and 100 mM N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (GE) immediately prior to injection. The CM5 sensor chip is activated for 420 s with the mixture at a flow rate of 10 μL/min, which typically results in immobilization levels of 100 resonance units (RU). The chip is deactivated by 1 M ethanolamine hydrochloride-NaOH (GE) at a flow rate of 10 μL/min for 420 s. The reference surface channel was prepared in the same way as the active surface, but without injecting mouse FcRn. The HA-Fc/wt proteins were diluted with the running buffer B (0.05% Tween-20 in PBS, pH 6.0) to 62.5, 31.25, 15.625, 7.813, 3.906, 1.953 and 0 nM. The HA-Fc/wt proteins were injected and allowed to flow at a rate of 30 μL/min for an association phase of 90 s, followed by 210 s for dissociation in the running buffer B. The affinity was analyzed by Biacore T200 Evaluation Software 3.0 in Biacore T200.

Immunofluorescence assay

Immunofluorescence was performed as previously described (22). Briefly, cells were grown on coverslips for 48 hr. The cells were rinsed with Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) in HBSS for 20 min and quenched with 100 mM glycine in PBS for 10 min. Cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton-X in HBSS for 5 min and incubated with blocking solution (3% normal goat serum in PBS) for 30 min. Cells were incubated with anti-HA Ab diluted in blocking solution for 2 hr. After washing, Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated anti-mouse IgG1 or IgG2a secondary Ab was added for 1 hr. Cells were washed with PBS and mounted to slides with ProLong Antifade solution (Thermo Scientific). Images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope and analyzed by LSM Image Examiner software (Zeiss).

Mouse immunization and virus challenge

All the animal experiments were performed with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. FcRn KO mice are a kind gift from Dr. Derry Roopenian (Jackson Laboratory). Six to eight-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (Charles River Laboratory) and FcRn KO mice were intranasally (i.n.) immunized with 20 μl of 5 μg HA-Fc/wt, HA-Fc/mut, equivalent molar of recombinant HA, or PBS. All vaccine proteins or PBS were mixed with 10 μg of CpG ODN 1826 (Invivogen). For intramuscular (i.m.) immunizations, mice were injected in the right hind leg with a 50-μl sample containing 5 μg HA-Fc/wt antigen admixed with 10 μg CpG. Two weeks later, the mice were boosted with the same vaccine formulations. The mice were i.n. infected with lethal doses (104 TCID50, equal to 5 MLD50) of the PR8 virus two weeks after the boost. For immunizations and challenge, all mice had anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 200 μl of fresh Avertin (20 mg/ml, Fisher Scientific) and laid down on in a dorsal recumbent position to allow for recovery. After infection, mice were monitored daily for weight loss and other clinical signs of illness for 14 days. Animals that lost above 25% of their body weight on the day of infection or had become grossly moribund were euthanized.

Collections of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and nasal wash fluids and preparation of single-cell suspensions from tissues

BAL and nasal wash fluids were collected 14 days after boost. Briefly, a small incision was made in the trachea. A syringe with a thin tube inserted at the tip was filled with PBS. The syringe was inserted first into the trachea towards the lungs and 1 ml of PBS was carefully injected into the lungs and by keeping the syringe in position, the PBS was retrieved back for the collection of BAL. For sampling the nasal wash, the syringe was similarly inserted into the trachea but towards the nasal cavity. PBS was carefully injected into the nasopharynx and collected when it flowed from the external nares. BAL and nasal wash fluids were then subjected to low-speed centrifugation and the supernatants were retained.

The single-cell suspensions from the mediastinal lymph nodes (MedLN) or spleen were made by mechanical abrasion of the organs. For isolation of cells from bone marrow, tibias and femurs were removed and the ends were clipped. The bone marrow was flushed out with RPMI1640. Isolation of single cells from the lung was performed as previously described (22). Briefly, after perfusion with 3 ml of PBS, lungs were minced and treated to enzymatic digestion in RPMI with pronase (1.5 mg/ml), Dispase (0.2%), and DNase (0.5 mg/ml) for 40 min at 37°C with rotation. All cells from the MedLN, spleen, bone marrow, and lung were filtered through a 40 μm nylon cell strainer and treated with red blood cell (RBC) lysis buffer (0.14 M NH4Cl, 0.017 M Tris-HCl at pH 7.2). All cells were washed and suspended in 2% FBS (Invitrogen) in PBS or RPMI1640 complete medium with 1-2% FBS. For each experiment, cells were pooled from 3–5 mice in each animal group.

Intravenous in vivo Ab labeling and flow cytometry

For intravenous in vivo labeling of circulating T cells, mice were intravenously injected with 3 μg of PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated anti-mouse CD3e Ab (145-2C11, BD Biosciences). After 10 min, lungs were perfused with 3 ml of PBS, and the single-cell suspensions were made as described above. Fc block (anti-mouse CD16/CD32, BD Biosciences, 1 μg/sample) was added to the lung and spleen cell samples and incubated for 30 min at 4°C. After washing with FACS buffer, cells were incubated with fluorescently-conjugated Abs to stain for T cell markers, CD3 PE (145-2C11, BD Biosciences), CD4 APC-Cy7 (RM4-5, BD Biosciences), CD8 APC-Cy7 (53-6.7, BD Biosciences), CD69 APC (H1.2F3, BD Biosciences), CD11a FITC (2D7, BD Biosciences), and CD103 FITC (M290, BD Biosciences), for 1 hr at 4°C. Isotype control Abs were included in each experiment. After washing, cells were suspended in 2% paraformaldehyde and analyzed using a FACSAria cytometer (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Intracellular cytokine staining

For determining T cell-derived cytokine levels, intracellular cytokine staining was performed as described (56). Briefly, single-cell suspensions from the lungs were stimulated with 2 μg of HA for 5 hr at 37°C. Cells were then incubated with GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) for an additional 5 hr. After wash, cells were incubated with Fc block and then stained with fluorescently-conjugated Abs for T cell surface markers, CD3 PE (145-2C11, BD Biosciences), CD4 APC-Cy7 (RM4-5, BD Biosciences), and CD8 APC-Cy7 (53-6.7, BD Biosciences). Cells were fixed and permeabilized by incubating with BD CytoFix/Perm. After FACS buffer wash, cells were stained for cytokines IFN-γ APC (XMG1.2, BD Biosciences) and TNF-α Alexa Fluor 488 (MP6-XT22, BD Biosciences). All block, incubation, and permeabilization steps were performed for 20 min at 4°C. After wash, cells were suspended in 2% paraformaldehyde and analyzed by flow cytometry as described above.

Virus titration and pulmonary pathology

Viral titers were determined by 50% endpoint dilution assay and hemagglutination assay as described (28, 29). Briefly, three extra mice were randomly selected from each immunized group and euthanized at day 4 post-infection. Mouse lungs were collected, individual lungs were homogenized in the TissueLyser LT (Qiagen). After centrifuging the homogenates, the supernatants were serially diluted and incubated on MDCK cells for 1 hr. The supernatants were removed from cells and replaced with serum-free Opti-MEM with 1 μg/ml tosyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)- treated trypsin. After incubation at 37°C for 3 days, the supernatant (50 μl) was mixed with chicken RBC (50 μl) and incubated for 35 min. Samples were scored for agglutination and virus titers were calculated by the Reed-Muench method.

To examine the lung pathology, lungs were removed from at least three mice in each group and photographed to observe gross pathology. Lungs were then fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution. The lungs were paraffin embedded, sectioned in five-micron thickness by American HistoLabs (Gaithersburg, MD) and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H & E). To determine the level of pulmonary inflammation, the lung inflammations were scored by an investigator who was blinded to the experimental design. A semi-quantitative scoring system, ranging from 0 to 5, was used to evaluate the following parameters: alveolitis, parenchymal pneumonia, inflammatory cell infiltration, peribronchiolitis, perivasculitis, and lung edema (30, 31). The inflammatory scores are defined as follows: 0, normal; 1, very mild; 2, mild; 3, moderate; 4, marked; and 5, severe. An increment of 0.5 was assigned if the inflammatory score falls between two integers.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot).

For the detection of HA-specific Abs in serum, BAL fluid and nasal washes, ELISA plates (Maxisorp, Nunc) were coated with 3 μg/ml of the trimeric HA protein (NR-19240, BEI Resources) in coating buffer and incubated overnight at 4°C. For determination of the interaction between the HA-Fc and HA stalk-specific Abs, plates were coated with serially diluted mAbs, starting from 3 μg /ml. Plates were then washed three times with 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS (PBST) and blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBST for 1 hr at room temperature. Samples were serially diluted in 2% BSA-PBST or HA-Fc (0.5 μg/well) was added for 2 hr incubation. After washing 3 times, HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG Ab (1:20000, Pierce) or anti-mouse subclass-specific Ab (1:5000, Southern Biotech) was added. For use of biotin-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG-specific Fab (1:2,000), the streptavidin-HRP (1:8000) was added. The reaction was visualized in a colorimetric assay using substrate tetramethyl benzidine (TMB) and analyzed using Victor III microplate reader (Perkin Elmer). Titers represent the highest dilution of samples showing a 2-fold increase over average OD450 nm values of negative controls.

For measuring HA-specific Ab-producing plasma cells, 96-well ELISpot plates (Millipore) were pre-wetted with 35% ethanol and washed with PBS. The plates were then coated with 5 μg/ml of HA protein overnight at 4°C and blocked with RPMI 1640 complete medium with 10% FBS for 2 hr at 37°C under 5% CO2. Serial dilutions of single-cell suspensions from bone marrow were prepared in RPMI 1640 and added to the coated wells for 24 hr at 37°C in 5% CO2. After the incubation, the cells were removed, and the plates were washed 5 times with PBST, then incubated with biotin-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG-specific Fab Ab (1:2000) for 2 hr. After washing with PBST, the streptavidin-conjugated HRP (1:3000) was added and incubated for 1 hr. The samples were developed with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) substrate (BD Biosciences). After washing, the plates were stored upside down in the dark to dry overnight at room temperature. Spots were counted with an ELISpot reader and analyzed by ZellNet Consulting (New Jersey).

Microneutralization assay

Neutralizing Abs were measured by a standard microneutralization assay on MDCK cells as previously described (32). Briefly, receptor destroying enzyme (RDE)-treated serum samples were serially diluted in PBS with 1x antibiotics/antimycotics. Then, 100 TCID50 of the PR8 virus was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 1 hr. MDCK cells were incubated with the serum/virus mixture for 1 hr at 37°C. After removing the mixture, serum-free Opti-MEM containing 1 μg/ml TPCK-treated trypsin was added to each well and incubated for 3 days at 37°C. Cytopathic effects (CPE) were observed daily and the presence of virus was determined by HA assay as described elsewhere. Neutralizing Ab titers were determined as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution preventing the appearance of CPE. Each assay was done in triplicate. The average neutralizing Ab titer was determined for each immunization and control group.

Statistics analysis.

To compare the Kaplan-Meier survival curves, we used multiple Mantel-Cox tests. Differences in Ab titers, cytokine percentages, virus titers, inflammation scores, and IgG-secreting cell numbers were assessed by using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison tests. GraphPad Prism 5.01 software was used for the statistical analyses.

Results

Expression and characterization of influenza HA-Fc fusion proteins

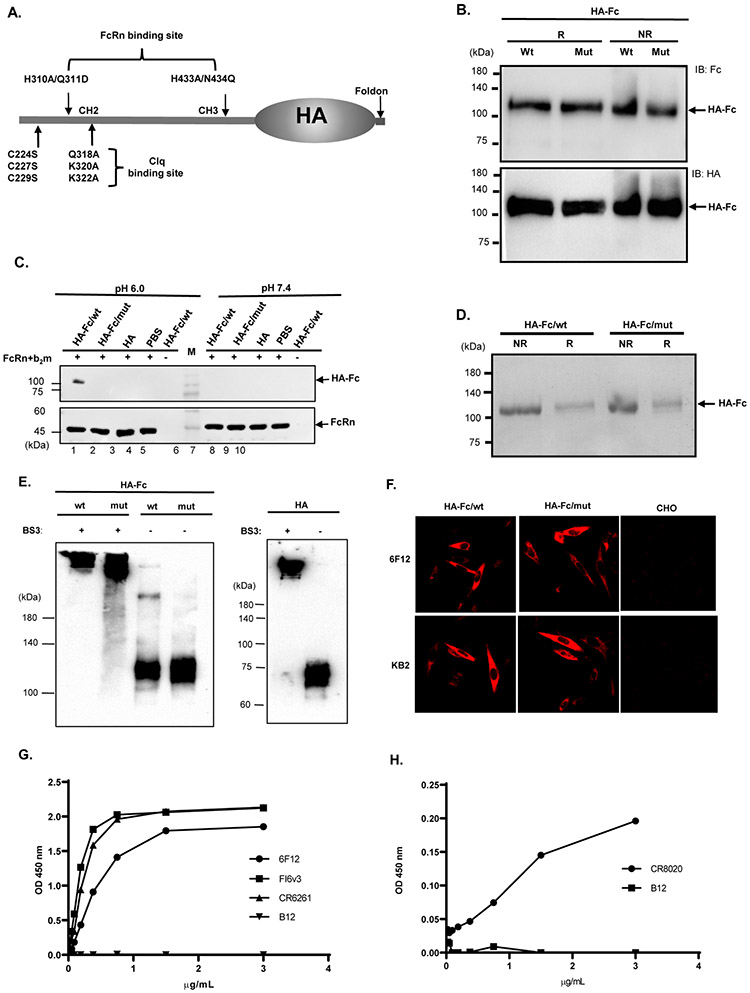

To activate virus infectivity, the HA precursor molecule HA0 is cleaved into HA1 and HA2 (33). To produce the non-cleavable HA0 protein, mutagenesis at the cleavage sites (SIQS→QRET) of PR8 HA ensured that the expressed HA would remain in the HA0 pre-cleavage state. The HA exists as a trimer on the virions or virally infected cells. It is likely that a trimeric HA antigen fused to an Fc would more closely mimic a native HA structure. Because IgG Fc forms a disulfide-bond dimer, we created a monomeric Fc by eliminating the disulfide bonds formed by three cysteines at positions 224, 227, and 229 by substituting with serine residues. We also generated an Fc mutant that was unable to bind FcRn owing to histidine residue substitutions at positions 310 and 433 (23) (Fig. 1A). In both wild type (wt) and mutant (mut) Fc for FcRn binding, the complement C1q-binding motif was eliminated (24) (Fig. 1A). To facilitate trimerization, we engineered a foldon domain from T4 bacteriophage fibritin (25) to the C-terminus of HA0. We fused the monomeric IgG Fc/wt or Fc/mut in frame with the HA0-Foldon, respectively (Fig. 1A), generating plasmids that expressed trimeric HA-Fc/wt or HA-Fc/mut proteins.

Figure 1. Expression and characterization of the trimeric HA-Fc fusion proteins.

(A). Schematic illustration of the genetic fusion of influenza HA, the T4 fibritin foldon domain (Fd), and murine Fcγ2a cDNA to create a trimeric HA-Fc fusion gene. Mutations were made in the Fcγ2a fragment using site-directed mutagenesis by replacing Cys224, Cys227, and Cys229 respectively with a Ser residue to abolish Fc dimerization, and replacing Glu318, Lys320, and Lys322 with an Ala residue to deplete complement C1q binding site. His310/Gln311 (HQ) and His433/Asn434 (HN) residues were replaced with Ala310/Asp311 (AD) and Ala433/Gln434 (AQ) to eliminate FcRn binding sites, this plasmid was designated as HA-Fc/mut.

(B). The HA-Fc fusion protein secreted by a stable CHO cell line. The HA-Fc were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses and detected by either goat anti-mouse IgG-Fc (top panel) or an anti-HA mAb (bottom panel). The fusion protein was shown as a monomer under both non-reducing (NR) and reducing (R) conditions.

(C). FcRn binding of the HA-Fc. CHO cells expressing mouse FcRn and β2m were incubated with 3 μg HA-Fc/wt, HA-Fc/mut, or HA protein for 1 hr at 4°C under pH 6.0 or pH 7.4 condition. After washing, the cells were lysed with 0.5% CHAPS in cold PBS (pH 6.0 or 7.4). Samples were subjected to Western blot analyses. The HA-Fc or HA (top) or mouse FcRn (bottom) was detected with anti-HA or anti-mouse FcRn primary Ab and HRP-conjugated secondary Ab.

(D). The HA-Fc/wt and HA-Fc/mut were purified by affinity chromatography and visualized with Coomassie blue staining.

(E). Western blot analysis of the purified HA-Fc that was cross-linked with BS3. The BS3 -treated (lane 1) or -untreated (lane 2) samples were separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions followed by Western blotting using anti-HA Ab (RA5-22, mouse IgG1).

(F). Stable CHO cell lines expressing HA-Fc/wt and HA-Fc/mut were probed with conformation-dependent anit-HA mAbs. CHO cells were transfected with HA-Fc plasmids and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were then incubated with HA-specific mAb 6F12 (top panel) or KB2 (bottom panel) and visualized using immunofluorescence staining.

(G). Interactions of the purified HA-Fc with a panel of HA stalk-specific and conformation-dependent Abs CR6261, FI6v3, 6F12, or CR8020. The specific binding was detected by the ELISA method. HIV gp120 specific IgG mAb B12 was used as a negative control.

Representative images of three experiment

We observed that both HA-Fc/wt and HA-Fc/mut proteins secreted from stable CHO cells were monomers under reducing or non-reducing conditions (Fig. 1B and 1D), suggesting the removal of the disulfide bonds in the Fc. The fusion proteins were expressed in the HA fused at the C- or N-terminus of the Fc. FcRn binds IgG at acidic pH but not neutral pH conditions (21). To determine whether HA-Fc/wt or HA-Fc/mut protein binds to FcRn, we incubated CHO cells expressing mouse FcRn and β2m with 3 μg HA-Fc/wt, HA-Fc/mut, or HA protein under pH 6.0 or pH 7.4 condition for 1 hr at 4°C. In this way, FcRn would bind the HA-Fc proteins only at pH 6.0. As shown in Figure 1C, the HA-Fc/wt and FcRn proteins were detected with anti-HA or anti-FcRn specific Ab (lane 1). However, the HA-Fc/mut (lane 2) or HA (lane 3) proteins were not found. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) assay determined that the affinity constant of the trimeric HA-Fc binding to immobilized mouse FcRn was 2.38 nM (Fig. S1). Therefore, the trimeric HA-Fc/wt protein maintains the structural integrity required to interact with FcRn.

We further determined if the HA portion of the HA-Fc indeed maintains its trimeric conformation. First, the BS3, a hydrophilic, 11 ångström cross-linker that covalently links proteins, can stabilize trimeric influenza HAs (34, 35). Thus, we cross-linked the HA-Fc/wt or HA-Fc/mut proteins with BS3 and the treated proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis under a reducing and denaturing condition. As shown in Fig. 1E, the treated HA-Fc/wt and HA-Fc/mut proteins migrated to a position at an approximately 330 kDa in comparison with the untreated HA-Fc protein that migrated at 110 kDa position, suggesting the HA-Fc protein exists as a trimer. The HA proteins migrated at 70 kDa without BS3 treatment, but at about 210 kDa with BS3 treatment. Second, we used broadly neutralizing HA Abs to probe the epitopes on HA-Fc/wt. The HA-Fc/wt interacted with mAbs 6F12 and KB2 in an immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 1F) in CHO stable cell lines or with mAbs CR6261, FI6v3, and 6F12 in soluble form in a concentration-dependent manner in ELISA (Fig. 1G). CR8020 mAb showed the binding with low affinity because it preferably binds to the HA stalk of Group 2 influenza virus. All these HA-specific mAbs are conformation-dependent (36-39). Together, we showed that the HA portion of the HA-Fc proteins forms trimer and maintains the correct conformational structure, while its monomeric Fc portion retains its ability to interact with FcRn.

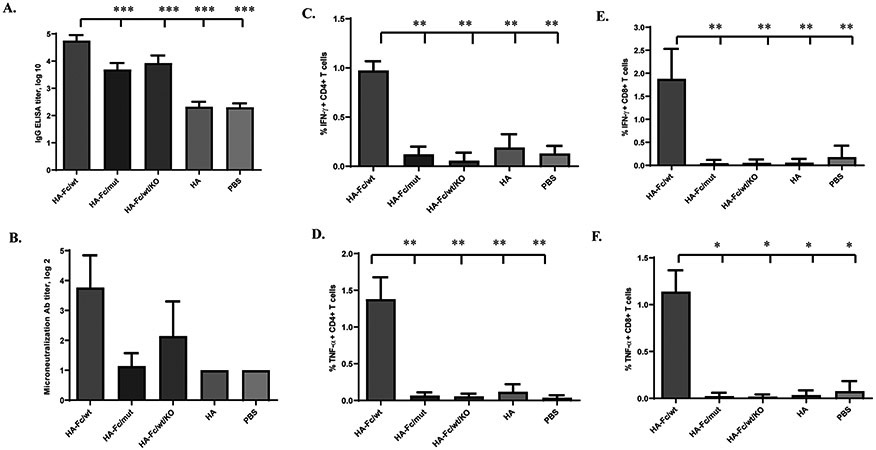

FcRn-mediated intranasal vaccination significantly enhances HA-specific immune responses

We tested whether FcRn-dependent transport augments the immunogenicity to HA protein. Mice were immunized i.n. with 5 μg of HA-Fc, HA protein (equal molar amount), or PBS, all in combination with 10 μg CpG, and boosted after 2 weeks. The specific engagement of FcRn in enhancing immunity was demonstrated in WT mice that were immunized with trimeric HA-Fc/mut proteins or FcRn knockout (KO) mice that are immunized with trimeric HA-Fc/wt proteins. The HA unlinked to an Fc fragment allowed us to evaluate FcRn-independent effects in vivo and determine the magnitude of any observed enhancement in immune responses conferred by targeting the HA-Fc to FcRn. Therefore, these control groups allow us to evaluate the extent that interactions between FcRn and Fc contribute to the immune responses. We co-administrated CpG as a mucosal adjuvant (40). Significantly higher titers of total IgG (Fig. 2A), together with IgG1, IgG2b, and IgG2c (Fig. S2), were seen in the HA-Fc/wt immunized mice when compared with the HA, HA-Fc/mut, HA-Fc/wt/KO immunized and PBS-treated groups of mice. We found that CpG was necessary to enhance the Ab immune responses when the HA-Fc was targeted to FcRn. Moreover, sera from the HA-Fc/wt immunized mice exhibited strong neutralizing activity relative to other control groups (Fig. 2B). Likewise, HA-Fc/wt proteins induced strong IFN-γ or TNF-α producing CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses, as evidenced by significantly higher percentages of IFN-γ or TNF-α producing CD4+ (Figs. 2C & 2D and Fig. S3A) and CD8+ (Figs. 2E & 2F and Fig. S3B) T cells in response to HA stimulation in the lungs of WT mice immunized with HA-Fc/wt comparing to the other groups. This Th1 response was also supported by a major presence of the IgG2c subclass in the sera of the immunized mice (Fig. S2). It remains uncertain whether this polarized Th1 cell response is caused by mucosal immunization as a result of FcRn targeting or, more likely, by the CpG used as adjuvant. Overall, our data demonstrate that engagement of FcRn greatly increased the efficiency by which HA antigen-specific Ab and cellular immune responses were induced.

Figure 2. FcRn-mediated respiratory immunization induces HA-specific Ab and T cell immune responses.

Five μg of HA-Fc/wt, HA-Fc/mut, HA, or PBS in combination with 10 μg of CpG was i.n. administered into wild-type (WT) or FcRn knockout (KO) mice. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests was used. Values marked with asterisks in the figures: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, ***, P<0.001. Immunization conditions are displayed on the bottom.

(A). Measurement of anti-influenza HA-specific IgG Ab titers in serum after the booster immunization. Influenza HA-specific Ab titers were measured by coating with HA protein in ELISA 14 days after boosting. The IgG titers were measured in 10 representative mouse sera. The data represent mean ± S.E.M.

(B). Test of neutralizing Ab activity in the immunized sera. Two weeks after boost, sera sampled from 13 to 20 mice per group were heat-inactivated, diluted twofold in PBS with antibiotics/antimycotics. Influenza PR8 (100 TCID50) was added and incubated at 37°C for 1 hr. The mixture was added to MDCK cells and incubated at 37°C and subsequently removed after 1 hr. The serum-free Opti-MEM containing 1 μg/ml TPCK-trypsin was added to cells. After incubation at 37°C for 72 hr, an HA assay was performed on the supernatant. The neutralization Ab titers were expressed as the reciprocal of the twofold serial dilution preventing the appearance of the agglutination of the erythrocytes of chicken. Each assay was performed in triplicate.

(C, D, E, & F). The percentage of IFN-γ and TNF-α producing T cells in the lung 7 days after the boost. The lung lymphocytes from the immunized mice were stimulated for 10 hr with purified HA or medium control. Lymphocytes were gated by forward and side scatters and T cells labeled with anti-CD3 and identified by their respective surface markers CD4 and CD8 and intracellular IFN-γ or TNF-α staining. Numbers represent the percentage of IFN-γ+ CD4+ (C), TNF-α+ CD4+ (D), IFN-γ+ CD8+ (E), or TNF-α+ CD8+ (F) T cells. Isotype controls included FITC-mouse-IgG1 with baseline response. Flow cytometry plots are representative of two independent experiments with 4 immunized mice pooled in each group. Graphical data is the average percentage of the two experiments.

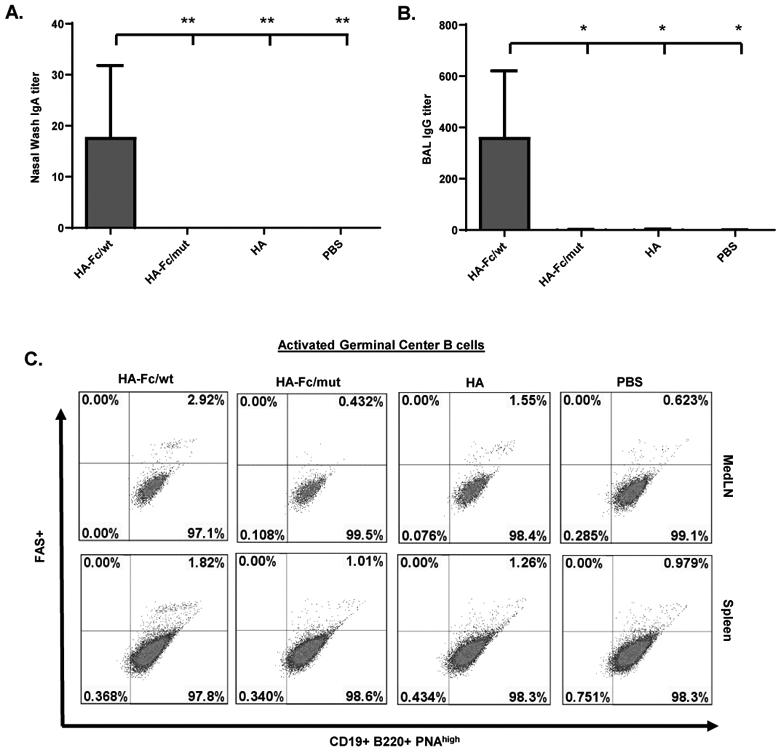

FcRn-mediated intranasal vaccination significantly induced HA-specific local immune responses in the respiratory tract

Because the influenza virus initiates its infection in the airway (41), an important objective for FcRn-targeted mucosal delivery of influenza virus vaccines is to elicit stronger mucosal immune responses, including the presence of anti-viral IgA Ab in nasal washes and IgG in the lung. Several lines of evidence demonstrate the outcome. To determine the ability of the FcRn-targeted mucosal immunization to induce local humoral immune responses, we examined HA-specific Abs in mucosal secretions. The nasal wash and bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BAL) were collected 14 days following the boost and analyzed for HA-specific IgG and IgA by ELISA. Significantly increased levels of HA-specific IgA and IgG were present in the nasal washes (Fig. 3A) and BAL (Fig. 3B) of the HA-Fc/wt protein immunized mice. WT, but not FcRn KO, mice that received the HA-Fc/wt protein had high levels of HA-specific IgA and IgG in the nasal washes and BAL (p <0.01, Fig. 3), suggesting that FcRn-mediated respiratory delivery of HA-Fc/wt induces mucosal IgA and IgG antibodies. The formation and maintenance of germinal centers (GC) generally lead to the differentiation of memory B cells and long-lived plasma cells. Second, we monitored the activated GC reaction in the MedLN and spleens 10 days after the boost. As shown in Fig. 3C, the trimeric HA-Fc/wt immunization induced substantially higher levels of FAS+PNA+B220+ B cells in the MedLN or spleen of WT mice in comparison with those of the control groups. We conclude that HA antigen targeting FcRn, combined with CpG, produced strong Ab and T cell immune responses in the respiratory mucosa.

Figure 3. FcRn-mediated intranasal vaccination significantly induced HA-specific local immune responses in the respiratory tract.

(A & B). Measurement of anti-influenza HA-specific Ab titers in nasal washings (A, IgA), and BAL (B, IgG) after the boost. Influenza HA-specific Abs were measured by ELISA 14 days after boost. The Ab titer was measured in 10 representative mouse samples. The data represent mean values for each group (±S.E.M.). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison tests was used.

(C). Accumulation of activated B cells in germinal centers (GCs) in the mediastinal lymph nodes (MedLNs) and spleens. Representative flow cytometric analyses of GC B cells among CD19+B220+ B cells in the MedLNs and spleens 10 days after the boost. B220+PNAhigh cells are B cells that exhibit the phenotypic attributes of GC B cells. The GC staining in the spleen was used as a positive control. GC B cells are pooled from individual mice because of the limited cell numbers isolated from each MedLN. Numbers are the percentage of activated GC B cells (PNA+FAS+) among gated B cells and are representative of three independent experiments.

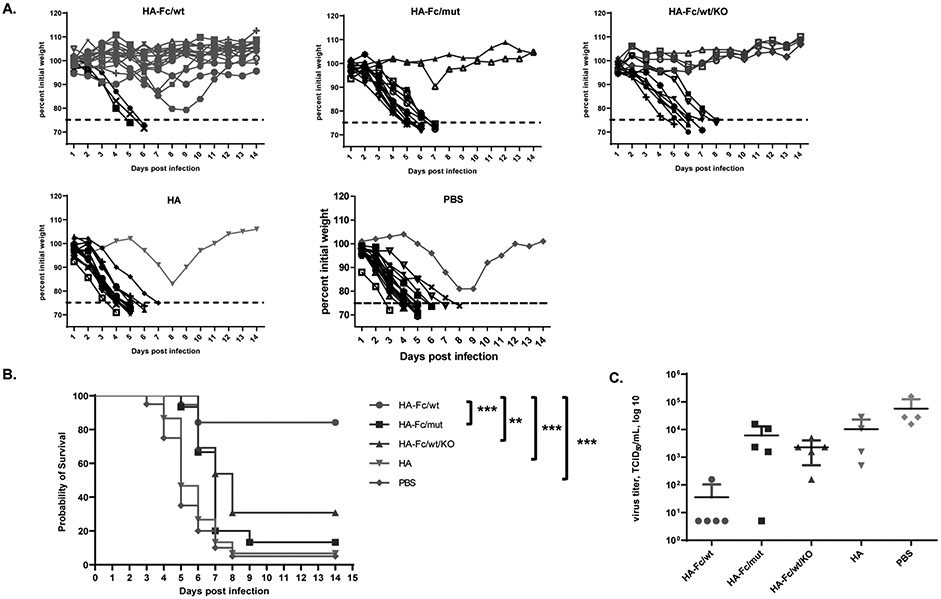

FcRn-targeted respiratory vaccination leads to increased protection against lethal influenza challenge

To test whether the humoral and cellular immune responses elicited by FcRn-targeted intranasal vaccination provides protection, we i.n. challenged all immunized mice with a lethal dose (5 MLD50) of influenza PR8 virus 2 weeks following the boost. Mice were monitored and weighed daily for a 14-day period and were euthanized at 25% body weight loss as a study endpoint. Most of the mice in the control groups had severe weight loss (up to 25%) within eight days after the challenge (Fig. 4A) and either succumbed to infection or were euthanized. In contrast, only 3 of the 19 HA-Fc/wt-immunized mice experienced a 25% body-weight loss. Hence, the trimeric HA-Fc/wt protein-immunized mice led to the protection in 84% of mice, which was significantly higher than the survival rates of other control groups (Fig. 4B). In addition, we assessed each group for viral replication in the lungs 4 days after lethal challenge (Fig. 4C). We observed markedly lower levels of virus in the lungs of the trimeric HA-Fc/wt-immunized mice. After the lethal challenge, there was a 1.5 to 3 log significant reduction of virus titer in the HA-Fc/wt-immunized group when compared with the PBS group (Fig. 4C). Other control groups of mice also essentially failed to contain viral replication. Some stochastic protections observed in the HA-Fc/mut and HA-Fc/wt/KO control groups (Fig. 4A) remain unknown; it might be associated with the innate immunity induced by the HA-Fc interacting with FcγRs in alveolar macrophages of individual mice.

Figure 4. FcRn-targeted respiratory immunization engenders protective immunity to intranasal (i.n.) challenge with virulent influenza virus.

(A). Body-weight changes following the influenza challenge. Two weeks after the boost, groups of 13-20 mice (HA-Fc/wt=19, HA-Fc/mut=15, HA=15, HA-Fc/wt/KO=13, PBS=20) were i.n. challenged with PR8 virus (5 MLD50) and weighed daily for 14 days. Mice were deceased or humanely euthanized if more than 25% of initial body weight was lost. The data is representative of three similar experiments with the data combined.

(B) Mean survival following influenza challenge. Two weeks after the boost, groups of 13-20 mice were i.n. challenged with PR8 virus (5 MLD50) and weighed daily for 14 days. Mice were humanely euthanized if more than 25% of initial body weight was lost. The percentage of mice from protection after the challenge was shown by the Kaplan-Meier survival curve. The data is representative of at least three similar experiments. Statistical differences were determined using multiple Mantel-Cox tests.

(C) Mean of viral titers in the lungs following influenza virus challenge. The virus titers in the lungs of the immunized and control mice (n=4-5) were determined 4 days after lethal challenge. Supernatants of the lung homogenates were added onto MDCK cells and incubated for three days. The viral titers were measured by 50% endpoint dilution assay along with an HA assay.

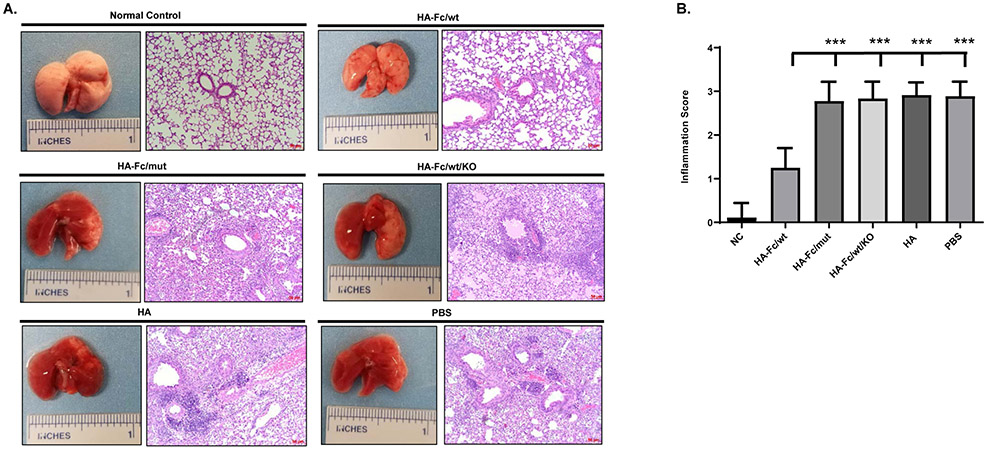

To further demonstrate protection, we characterized the lung pathology of all groups of mice following the challenge. The lung inflammations were scored in a blinded manner. Based on gross pathology, the lungs of mice in all control groups exhibited severe pulmonary lesions, as evidenced by hemorrhage with redness and edema (Fig. 5A). However, the lungs of HA-Fc/wt-immunized mice displayed significantly reduced hemorrhage with an overall pink-like color (Fig. 5A). The lungs of uninfected mice were used as normal control (Fig. 5A). To verify the gross pathology, we then utilized histopathology to determine the extent of lung inflammation. In agreement with the gross pathology, the histopathology of mouse lungs of all challenged control groups showed remarkable infiltrations of monocytes and lymphocytes, resulting in high levels of inflammation (Fig. 5B). In contrast, the mice immunized with HA-Fc/wt had a significantly lower inflammation score of the lungs, compared to those of mice in the control groups (Fig. 5B). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that FcRn-mediated delivery of the trimeric HA-Fc/wt confers significant protection against lethal PR8 challenge, resulting in decreased mortality, viral replication, and pulmonary inflammation. In addition, we did not find a significant difference in the sensitivity of PR8 infection between unimmunized wild type and FcRn KO mice.

Figure 5. Gross- and histopathology of the lungs from the challenged mice.

(A). Lungs were collected from 6- to 14-day period post-challenge based on a 25% body-weight loss endpoint. The lungs from uninfected mice were included as normal control (n=3). The lung sections were stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin (H & E) to determine the level of inflammation in the lungs (10x). The representative slides were shown on the right.

(B). The inflammatory responses for each lung section were scored in a blinded manner. Statistical differences were determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. All scale bars represent 50 μm, 10 X magnification.

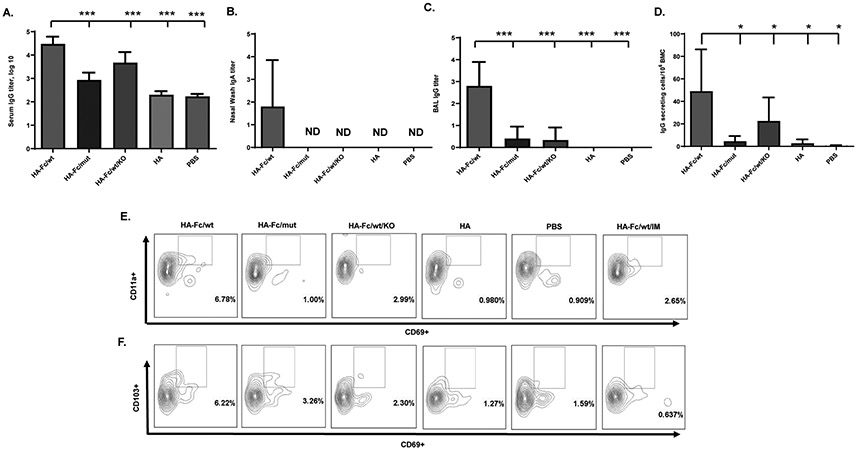

FcRn-targeted mucosal vaccination induces higher memory immune responses

In addition to providing immediate protection against infection after the boost, a successful influenza virus mucosal vaccine is expected to induce long-lasting immune memory. We wanted to determine whether the FcRn-mediated respiratory vaccination with HA-Fc/wt promotes an effective memory immune response up to 8 weeks after the boost. As shown in Fig. 6A, higher titers of HA-specific serum IgG were detected in the mice immunized with the HA-Fc/wt. To further show that this group of mice also maintains local immune responses, we again measured the IgA Abs in nasal washings and IgG in the BAL. We detected significantly high levels of HA-specific IgA and IgG in the nasal washes (Fig. 6B) and BAL (Fig. 6C) in the HA-Fc/wt-immunized mice, but not in the mice of control groups. By ELISpot, a significantly higher number of HA-specific IgG-secreting plasma cells were detected in the bone marrow of mice immunized with HA-Fc/wt (Fig. 6D). The existence of long-lived plasma cells in the bone marrow niche accounts for the maintenance of high levels of viral antigen-specific IgG in circulation (42). We detected some IgG secreting plasma cells in the immunized FcRn KO mice, we speculate that the IgG secreting cells may be contributed by an individual mouse with positive immune responses because pooled samples were used. Also, there was no significant difference in the number of IgG secreting plasma cells between the mice immunized by HA-Fc/mut and FcRn KO mice immunized by HA-Fc/wt proteins (P>0.05). It remains to be determined whether HA-specific IgA-secreting plasma cells also develop. These data indicate that HA-specific B cells maintained significant memory immunity potential at least 2 months after the boost.

Figure 6. Increased memory immune responses in FcRn-mediated respiratory immunization.

(A) The duration of influenza-specific serum IgG response. Influenza HA-specific IgG was quantified by ELISA in serum by endpoint titer from 8-10 mice at 8 weeks after the boost. Influenza HA-specific IgG Ab was not detectable (ND) in PBS-immunized mice. Statistical differences were determined using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison tests.

(B & C). Measurement of anti-influenza HA-specific Ab titers in nasal washings (B, IgA), and BAL (C, IgG) after the boost immunization. Influenza HA-specific Abs were measured 8 weeks after boosting by ELISA. The Ab titer was measured in 5 representative mouse samples. The data represent mean values for each group (±S.E.M.).

(D) Long-lived influenza HA-specific Ab-secreting cells in the bone marrow. Bone marrow cells (BMCs) removed 8 weeks after the boost was placed on HA-coated plates and quantified by ELISPOT analysis of IgG-secreting plasma cells. Data were pooled from two separate experiments with 5 immunized mice pooled in each group. The graphs were plotted based on the average ELISPOT for four replicate wells for each experiment. The asterisk denotes statistics significant differences (P<0.05).

(E+F). Induction of tissue-resident memory (TRM) T cells in mouse lungs. An additional group of mice that were i.m. immunized HA-Fc/wt was included as a parenteral route control. The CD3+CD4+CD69+CD11a+ (E) or CD3+CD8+CD69+CD103+ (F) TRM T cells in the lungs were assessed 8 weeks after the boost by FACS. Flow cytometry plots are representative of two independent experiments with 4 immunized mice pooled in each group. Numbers in the quadrants represent the percentage of TRM T lymphocytes.

Memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are essential to provide protection against the influenza virus (6, 43). A recently appreciated subset is TRM T cells, a subset of T cells that are non-circulating and remain in the lung to provide a rapid response against influenza infections (44, 45). Hence, we determined whether FcRn-mediated immunization could induce TRM T cells in the lung. In order to differentiate circulating T cells from lung TRM T cells, we used the method of an intravenous (i.v.) in vivo infusion of fluorescently labeled anti-CD3 Ab which targets T cells in circulation, but not CD4+ TRM (CD69+ CD11a+) or CD8+ TRM (CD69+CD103+) T cells within the lung (44, 45). We detected substantial numbers of CD4+CD69+CD11a+ TRM cells (Fig. 6E) and CD8+CD69+CD103+ TRM cells (Fig. 6F) in the lungs, but not in the spleen of HA-Fc/wt-immunized mice (Fig. S4), in comparison with that of mice in the control groups. We also failed to detect an appreciable increase in CD4+ or CD8+ TRM T cells in the lungs of all experimental animals when mice were immunized by the intramuscular (i.m.) route (Fig. 6E & 6F). Together, these data suggest that FcRn-targeted respiratory, but not parenteral, immunization can induce lung-resident memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

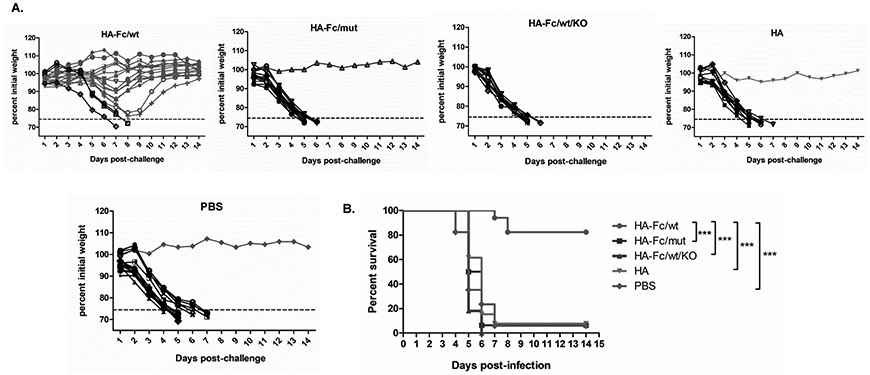

Last, to test if these memory immune responses could provide protection, we again challenged the immunized mice with i.n. PR8 strain two and half months after boost. Mice were weighed daily for a 14-day period and were euthanized at 25% body weight loss as a study endpoint. Most of the mice in the control groups had severe weight loss within 6-7 days after the challenge (Fig. 7A), and either succumbed to infection or were euthanized. Upon lethal challenge, mice immunized with the HA-Fc/wt exhibited significantly reduced disease severity with a survival rate of 80% (Fig. 7B), while mice in control groups succumbed to rapid weight loss and death. Overall, FcRn targeted mucosal delivery of influenza HA vaccine engendered an effective memory immune response and provided protection against challenge.

Figure 7. FcRn-targeted respiratory immunization induces protective memory immune responses to resist challenge by influenza virus.

(A). Body-weight changes following the influenza virus challenge. Eight weeks after the boost, groups of mice (HA-Fc/wt=17, HA-Fc/mut=16, HA=13, HA-Fc/wt/KO=11, PBS=17) were i.n. challenged with PR8 virus (5 MLD50) and weighed daily for 14 days. Mice were deceased or humanely euthanized if more than 25% of initial body weight was lost.

(B). Mean survival following influenza virus challenge in mice 8 weeks following the boost. The immunized mice were i.n. challenged with 5 MLD50 of PR8 virus and weighed daily for 14 days. Mice were deceased or humanely euthanized if more than 25% of initial body weight was lost. The percentage of mice protected on the indicated days is calculated as the number of mice survived divided by the number of mice in each group (n=5), as shown by the Kaplan-Meier survival curve. Statistical differences were determined using multiple Mantel-Cox tests. The data represent combined data of two independent animal experiments.

Discussion

Respiratory tract infections are important causes of serious illnesses and death. Conventional vaccination with non-replicative vaccines is primarily administered by the parenteral routes. However, successful vaccination against respiratory infections may require high levels of potent and durable humoral and cellular responses in the local respiratory tract that are best achieved by direct, mucosal immunization. To achieve this goal, a strategy to deliver vaccine antigens via the respiratory route is needed to improve the protective efficacy against respiratory infections. We are developing a novel strategy for vaccine delivery based on exploiting the FcRn-mediated Ab transfer pathway to deliver an influenza virus HA-Fc fusion protein vaccine across the respiratory epithelial barrier.

By using an intranasal delivery route for the nasal spray influenza vaccine, the present study demonstrates that FcRn-targeted respiratory vaccination induced substantial local and systemic immunity against lethal influenza virus infection. Site-specific (lungs)-targeted delivery provided a unique pathway to produce local and systemic immunity against influenza virus infection. Several lines of evidence support this conclusion. First, the HA-Fc/wt immunized mice have produced significantly high levels of IgG in the blood. Second, the HA-Fc/wt-immunized mice exhibited strong neutralizing Ab activity relative to control groups. Third, the majority of HA-Fc/wt-immunized mice resisted lethal influenza virus infection with reduced virus replication and inflammation in the lung. In contrast, most mice immunized by HA-Fc/mut or HA alone exhibited poor immune responses, increased levels of pulmonary inflammation, and decreased protection against virus challenge. The HA-Fc/mut protein was a control used to show that FcRn was directly mediating delivery of HA-Fc/wt antigen, eliminating the concern of a mucosal leakage. Our data clearly illustrate that the FcRn-mediated delivery pathway is essential to the protection against influenza virus challenge and demonstrate the value of our trimeric fusion protein strategy for directing viral antigens to this pathway. Several mechanisms may account for the protection against respiratory infection by FcRn-targeted mucosal vaccination. Efficient delivery of HA-Fc proteins across the respiratory barrier may increase the half-life of HA-Fc (21) to allow for enhanced FcRs-mediated uptake of HA-Fc by antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells (46-48). Previous studies showed that HA alone by i.n. route elicited some protective immunity following intranasal immunization (49); in our hand, HA alone was very poorly immunogenic and produced minimal protection against virus challenge. Previous work showed CpG does not increase the permeability of airway respiratory barrier; in contrast, it enhances the tight junction integrity of the bronchial epithelial cell barrier (50). We avoid other agents including volatile chemical anesthetics that are known to increase epithelial barrier permeability. Hence, our results clearly point to the benefits of FcRn-mediated delivery for enhancing the efficacy of respiratory tract-administered influenza virus HA antigens.

Considering influenza virus infects the epithelial cells lining the respiratory tract, an ideal vaccine should induce immunity in the mucosa that can effectively block virus penetration and spread. The local humoral immune response can be characterized by secretion of IgA in the upper respiratory tract or IgG in the BAL, and the presence of activated germinal centers (GCs) in the draining lymph node, and the cytokine secretion by lung-specific T cells (1, 4). First, the trimeric HA-Fc/wt-immunized mice have produced high levels of IgG and IgA Abs in the BAL and nasal secretions. IgA is a major protective Ab in nasal secretions after immunization with influenza vaccine (41, 51). Local secretory Abs represent a primary barrier of immune defense against viral infections of the respiratory tract. Second, the HA-Fc/wt induced a high frequency of IFN-γ or TNF-α producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the lung tissues of the immunized mice. IFN-γ and TNF-α are clearly indispensable for resistance to influenza infections (52). Third, we detected the presence of activated GCs in the MedLNs draining the lung. The nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) and the MedLNs are usually the sites where respiratory immune responses are initiated against antigens administered intranasally, after reaching the lung. The presence of activated GCs in the NALT merits further investigation. Hence, FcRn-mediated respiratory delivery of influenza virus vaccine antigens promotes potent antiviral humoral and cell-mediated immune responses at the primary site of influenza infection, which is critical for clearance of the virus.

Induction of influenza-specific memory responses is crucial for a vaccine to provide protection after re-exposure to the influenza virus (6, 43, 53). Immunological memory has been a concern in protein-based subunit mucosal vaccine development. To establish long-lasting protection, a multifaceted memory immune response is essential, including virus-specific memory T and B cells and long-lasting plasma cells. A remarkable feature of this study is that FcRn-mediated mucosal vaccination with HA-Fc/wt induced and sustained higher levels of HA-specific Abs, both IgA and IgG, and plasma cells 2 months after the boost. More importantly, we detected a higher percentage of CD4+ or CD8+ TRM T cells in the lungs of mice immunized with HA-Fc/wt, but not in control groups. CD4+ T cells are essential for promoting memory CD8+ T cell responses, including TRM CD8+ T cells (6, 54). TRM CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in the lung have been shown to promote rapid viral clearance at the site of infection and mediate survival against lethal influenza challenge (54, 55). In addition, we showed that TRM T cells are induced only via intranasal immunization and not by intramuscular injections. This result is consistent with other findings that TRM T cells appear in the lung after natural influenza infection (45, 56) or they are induced by intranasal vaccination with live attenuated influenza virus in a mouse model (44). Our results from FcRn-mediated respiratory delivery of influenza virus HA antigens verifies that the lung-resident T cells can only be induced solely via respiratory vaccination. Corresponding to the induction of memory humoral and cellular immune responses, most HA-Fc/wt-immunized mice resisted lethal influenza infection 2 months after boost. Further studies are needed to confirm how long this subset of TRM T cells persists in the lung and how they specifically contribute towards long-term protection against influenza virus infections.

The Fc-fused trimeric HA proteins are required to induce a high level of protection from influenza virus infection. We initially immunized mice with a dimeric Fc-fused monomeric HA protein. Although the monomeric HA-Fc/wt induced a strong IgG immune response, it only conferred partial protection to subsequent influenza challenge. This low protection conferred by the monomeric HA vaccine may be interpreted by the fact that the native viral HA exhibits a trimeric presentation, which is essential for inducing conformation-dependent neutralizing Abs that mirror those induced by exposure to natural infection. Hence, we designed and produced a trimeric HA-Fc that mimics the native HA structure, as evidenced by the recognition of the trimeric HA-Fc by conformation-dependent anti-HA Abs and its ability to bind to FcRn. As expected, the mice immunized by the trimeric HA-Fc/wt proteins had high levels of survival and decreased morbidity in HA-Fc/wt vaccinated mice.

We have shown that the effects of FcRn-targeted mucosal immunization differ considerably between WT and FcRn KO mice or the HA-Fc/wt and the HA-Fc/mut-immunized mice in terms of mucosal and systemic immune responses, cytokine expression profiles, the maintenance of T and B cell memory, long-lived bone marrow plasma cells, and resistance to infection. In this study, we proved that FcRn-targeted mucosal delivery of influenza virus HA vaccine can provide protection against homologous influenza virus. This study leaves an open question of whether this pathway can be used to deliver a universal influenza vaccine which protects against all strains of influenza virus, eliminating the need for seasonal vaccination with a potential to protect against pandemic strains. To achieve this goal, an optimal universal influenza vaccine is expected to induce broadly neutralizing Abs and cross-reactive T cells against conserved and protective influenza virus antigens, including the stalk domain of HA, nucleoprotein (NP), the ectodomain of matrix 2 (M2e), and/or neuraminidase (NA) (57). We reason that the development of a universal influenza virus vaccine using our FcRn-mediated mucosal delivery of highly conserved influenza virus antigens, such as chimeric HA (24, 58, 59) or HA stalk-based vaccine (38, 60), is very likely. First, our trimeric HA-Fc antigen is readily recognized by several conformation-dependent, stalk-specific Abs (CR6121, FI6v3, 6F12, and CR8020) in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1H) (36-39). Second, FcRn-mediated influenza HA delivery induces memory immune responses, including TRM T cells. TRM T cells are shown to promote viral clearance and mediate heterosubtypic protection and survival against lethal influenza virus challenge (44, 61). Third, FcRn-mediated mucosal delivery of influenza virus vaccines aimed at stimulating protective immunity in the respiratory tract will make prospective universal influenza virus vaccine that is very likely to be more effective and efficient. This mucosal response may forestall influenza virus infection in its early stages, thereby contributing significantly to the reduction in influenza clinical infection and spread in the community. Hence, the mucosal delivery of protein antigens by FcRn may bring us closer to the implementation of a universal influenza virus vaccine.

Taken together, our study has demonstrated the important role of FcRn in facilitating intranasal delivery of protective influenza virus vaccine antigens across the respiratory mucosa, highlighting a novel approach for formulating influenza virus vaccines that stimulate long-lasting, protective local and systemic immunities. We propose a model for FcRn-targeted respiratory immunization. In general, mucosal DCs take up FcRn-transported antigens and subsequently migrate to MedLNs where they prime CD4+ T cells and initiate the cognate B cell response in the GCs. By increasing the persistence of HA-Fc in tissue and circulation, interactions with FcRn may further enhance the development of long-term humoral and cellular immunity by sustaining high levels of serum IgG Abs and TRM T cells specific for HA. It is expected that FcRn can increase pre-existing influenza immunity because FcRn can transport influenza antigen-Ab complexes across the mucosal barrier (14). Our results imply that FcRn-mediated respiratory immunization could be proven to be an effective and safe strategy for maximizing the efficacy of vaccinations directed against influenza virus infections. Our goal is to develop multivalent mucosal vaccines offering protection against a spectrum of respiratory infections.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

A trimeric HA-Fc protein is characterized by their binding with HA mAbs or FcRn.

FcRn-targeted nasal immunization with HA-Fc induces mucosal and systemic immunity.

FcRn-mediated nasal delivery of HA-Fc confers protection from influenza infection.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Dr. Georgy Belov, Dr. Jeffrey DeStefano, Dr. Kenneth Frauwirth, and Dr. Wenxia Song for their helpful discussions and critical reading. We are grateful to Dr. Peter Palese for supplying us with the PR8 virus. We acknowledge the receipt of HA mAbs from Dr. Jeffrey Boyington and MDCK cells expressing rat FcRn from Dr. Pamela Bjorkman. We are most grateful for the technical help from Dr. Dana Farber, Dr. Yunsheng Wang, Mr. Rongyu Zeng, Dr. Chunyan Ma, and Dr. Xiaoling Wu.

Funding sources:

This work was supported in part by NIH grants AI146063, AI130712 (X.Z.), AI102680 (C.D.P. and X.Z.), AI131905 (M.S.), the NIH T32 grant AI125186 (S.P-O), MIPS grant (X.Z.), MAES grants from the University of Maryland (X.Z.), and Heyneker Foundation. W.T. and A.R. are supported by the intramural research program of the USDA ARS.

References

- 1.Allie SR, and Randall TD. 2017. Pulmonary immunity to viruses. Clin. Sci 131: 1737–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwasaki A, Foxman EF, and Molony RD. 2017. Early local immune defences in the respiratory tract. Nat. Rev. Immunol 17: 7–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barría MI, Garrido JL, Stein C, Scher E, Ge Y, Engel SM, Kraus TA, Banach D, and Moran TM. 2013. Localized Mucosal Response to Intranasal Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine in Adults. J. Infect. Dis 207: 115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiu C, and Openshaw PJ. 2015. Antiviral B cell and T cell immunity in the lungs. Nat. Immunol 16: 18–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mueller SN, Gebhardt T, Carbone FR, and Heath WR. 2013. Memory T Cell Subsets, Migration Patterns, and Tissue Residence. Annu. Rev. Immunol 31: 137–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner DL, and Farber DL. 2014. Mucosal Resident Memory CD4 T Cells in Protection and Immunopathology. Front. Immunol 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iijima N, and Iwasaki A. 2015. Tissue instruction for migration and retention of TRM cells. Trends Immunol. 36: 556–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodge LM, Marinaro M, Jones HP, McGhee JR, Kiyono H, and Simecka JW. 2001. Immunoglobulin A (IgA) Responses and IgE-Associated Inflammation along the Respiratory Tract after Mucosal but Not Systemic Immunization. Infect. Immun 69: 2328–2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brokstad KA, Eriksson J, Cox RJ, Tynning T, Olofsson J, Jonsson R, and Davidsson Å. 2002. Parenteral Vaccination against Influenza Does Not Induce a Local Antigen-Specific Immune Response in the Nasal Mucosa. J. Infect. Dis 185: 878–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muszkat M, Greenbaum E, Ben-Yehuda A, Oster M, Yeu’l E, Heimann S, Levy R, Friedman G, and Zakay-Rones Z. 2003. Local and systemic immune response in nursing-home elderly following intranasal or intramuscular immunization with inactivated influenza vaccine. Vaccine 21: 1180–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minne A, Louahed J, Mehauden S, Baras B, Renauld J-C, and Vanbever R. 2007. The delivery site of a monovalent influenza vaccine within the respiratory tract impacts on the immune response. Immunology 122: 316–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwasaki A 2016. Exploiting Mucosal Immunity for Antiviral Vaccines. Annu. Rev. Immunol 34: 575–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMaster SR, Wein AN, Dunbar PR, Hayward SL, Cartwright EK, Denning TL, and Kohlmeier JE. 2018. Pulmonary antigen encounter regulates the establishment of tissue-resident CD8 memory T cells in the lung airways and parenchyma. Mucosal Immunol. 11: 1071–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickinson BL, Badizadegan K, Wu Z, Ahouse JC, Zhu X, Simister NE, Blumberg RS, and Lencer WI. 1999. Bidirectional FcRn-dependent IgG transport in a polarized human intestinal epithelial cell line. J. Clin. Invest 104: 903–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spiekermann GM, Finn PW, Ward ES, Dumont J, Dickinson BL, Blumberg RS, and Lencer WI. 2002. Receptor-mediated Immunoglobulin G Transport Across Mucosal Barriers in Adult Life. J. Exp. Med 196: 303–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z, Palaniyandi S, Zeng R, Tuo W, Roopenian DC, and Zhu X. 2011. Transfer of IgG in the female genital tract by MHC class I-related neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) confers protective immunity to vaginal infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 108: 4388–4393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshida M 2006. Neonatal Fc receptor for IgG regulates mucosal immune responses to luminal bacteria. J. Clin. Invest. 116: 2142–2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bai Y, Ye L, Tesar DB, Song H, Zhao D, Bjorkman PJ, Roopenian DC, and Zhu X. 2011. Intracellular neutralization of viral infection in polarized epithelial cells by neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn)-mediated IgG transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 108: 18406–18411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ko S-Y, Pegu A, Rudicell RS, Yang Z, Joyce MG, Chen X, Wang K, Bao S, Kraemer TD, Rath T, Zeng M, Schmidt SD, Todd J-P, Penzak SR, Saunders KO, Nason MC, Haase AT, Rao SS, Blumberg RS, Mascola JR, and Nabel GJ. 2014. Enhanced neonatal Fc receptor function improves protection against primate SHIV infection. Nature 514: 642–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaughn DE, and Bjorkman PJ. 1998. Structural basis of pH-dependent antibody binding by the neonatal Fc receptor. Structure 6: 63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roopenian DC, and Akilesh S. 2007. FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age. Nat. Rev. Immunol 7: 715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye L, Zeng R, Bai Y, Roopenian DC, and Zhu X. 2011. Efficient mucosal vaccination mediated by the neonatal Fc receptor. Nat. Biotechnol 29: 158–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu L, Palaniyandi S, Zeng R, Bai Y, Liu X, Wang Y, Pauza CD, Roopenian DC, and Zhu X. 2011. A Neonatal Fc Receptor-Targeted Mucosal Vaccine Strategy Effectively Induces HIV-1 Antigen-Specific Immunity to Genital Infection. J. Virol 85: 10542–10553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krammer F, and Palese P. 2015. Advances in the development of influenza virus vaccines. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 14: 167–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duncan AR, and Winter G. 1988. The binding site for C1q on IgG. Nature 332: 738–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim J-K, Tsen M-F, Ghetie V, and Ward ES. 1994. Localization of the site of the murine IgG1 molecule that is involved in binding to the murine intestinal Fc receptor. Eur. J. Immunol 24: 2429–2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Letarov AV, Londer YY, Boudko SP, and Mesyanzhinov VV. 1999. The carboxy-terminal domain initiates trimerization of bacteriophage T4 fibritin. Biochem. Biokhimiia 64: 817–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frey A, Di Canzio J, and Zurakowski D. 1998. A statistically defined endpoint titer determination method for immunoassays. J. Immunol. Methods 221: 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirst GK 1942. The quantitative determination of influenza virus and antibodies by means of red cell agglutination. J. Exp. Med 75: 49–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisfeld AJ, Gasper DJ, Suresh M, and Kawaoka Y. 2019. C57BL/6J and C57BL/6NJ Mice Are Differentially Susceptible to Inflammation-Associated Disease Caused by Influenza A Virus. Front. Microbiol 9: 3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Damjanovic D, Divangahi M, Kugathasan K, Small C-L, Zganiacz A, Brown EG, Hogaboam CM, Gauldie J, and Xing Z. 2011. Negative Regulation of Lung Inflammation and Immunopathology by TNF-α during Acute Influenza Infection. Am. J. Pathol 179: 2963–2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh S, Selleck P, Temperton NJ, Chan PKS, Capecchi B, Manavis J, Higgins G, Burrell CJ, and Kok T. 2009. Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to different clades of Influenza A H5N1 viruses. J. Virol. Methods 157: 161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhirnov OP, Ikizler MR, and Wright PF. 2002. Cleavage of Influenza A Virus Hemagglutinin in Human Respiratory Epithelium Is Cell Associated and Sensitive to Exogenous Antiproteases. J. Virol 76: 8682–8689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krammer F, Margine I, Tan GS, Pica N, Krause JC, and Palese P. 2012. A Carboxy-Terminal Trimerization Domain Stabilizes Conformational Epitopes on the Stalk Domain of Soluble Recombinant Hemagglutinin Substrates. PLoS ONE 7: e43603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weldon WC, Wang B-Z, Martin MP, Koutsonanos DG, Skountzou I, and Compans RW. 2010. Enhanced Immunogenicity of Stabilized Trimeric Soluble Influenza Hemagglutinin. PLoS ONE 5: e12466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ekiert DC, Friesen RHE, Bhabha G, Kwaks T, Jongeneelen M, Yu W, Ophorst C, Cox F, Korse HJWM, Brandenburg B, Vogels R, Brakenhoff JPJ, Kompier R, Koldijk MH, Cornelissen LAHM, Poon LLM, Peiris M, Koudstaal W, Wilson IA, and Goudsmit J. 2011. A Highly Conserved Neutralizing Epitope on Group 2 Influenza A Viruses. Science 333: 843–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan GS, Krammer F, Eggink D, Kongchanagul A, Moran TM, and Palese P. 2012. A Pan-H1 Anti-Hemagglutinin Monoclonal Antibody with Potent Broad-Spectrum Efficacy In Vivo. J. Virol 86: 6179–6188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krammer F, Hai R, Yondola M, Tan GS, Leyva-Grado VH, Ryder AB, Miller MS, Rose JK, Palese P, Garcia-Sastre A, and Albrecht RA. 2014. Assessment of Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin Stalk-Based Immunity in Ferrets. J. Virol 88: 3432–3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friesen RHE, Lee PS, Stoop EJM, Hoffman RMB, Ekiert DC, Bhabha G, Yu W, Juraszek J, Koudstaal W, Jongeneelen M, Korse HJWM, Ophorst C, Brinkman-van der Linden ECM, Throsby M, Kwakkenbos MJ, Bakker AQ, Beaumont T, Spits H, Kwaks T, Vogels R, Ward AB, Goudsmit J, and Wilson IA. 2014. A common solution to group 2 influenza virus neutralization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 111: 445–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iho S, Maeyama J, and Suzuki F. 2015. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides as mucosal adjuvants. Hum. Vaccines Immunother 11: 755–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Renegar KB, Small PA, Boykins LG, and Wright PF. 2004. Role of IgA versus IgG in the Control of Influenza Viral Infection in the Murine Respiratory Tract. J. Immunol 173: 1978–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slifka MK, Antia R, Whitmire JK, and Ahmed R. 1998. Humoral Immunity Due to Long-Lived Plasma Cells. Immunity 8: 363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Araki K, and Ahmed R. 2010. From Vaccines to Memory and Back. Immunity 33: 451–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zens KD, Chen JK, and Farber DL. 2016. Vaccine-generated lung tissue–resident memory T cells provide heterosubtypic protection to influenza infection. JCI Insight 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pizzolla A, Nguyen THO, Smith JM, Brooks AG, Kedzierska K, Heath WR, Reading PC, and Wakim LM. 2017. Resident memory CD8 + T cells in the upper respiratory tract prevent pulmonary influenza virus infection. Sci. Immunol 2: eaam6970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qiao S-W, Kobayashi K, Johansen F-E, Sollid LM, Andersen JT, Milford E, Roopenian DC, Lencer WI, and Blumberg RS. 2008. Dependence of antibody-mediated presentation of antigen on FcRn. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 105: 9337–9342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu X, Lu L, Yang Z, Palaniyandi S, Zeng R, Gao L-Y, Mosser DM, Roopenian DC, and Zhu X. 2011. The Neonatal FcR-Mediated Presentation of Immune-Complexed Antigen Is Associated with Endosomal and Phagosomal pH and Antigen Stability in Macrophages and Dendritic Cells. J. Immunol 186: 4674–4686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baker K, Qiao S-W, Kuo TT, Aveson VG, Platzer B, Andersen J-T, Sandlie I, Chen Z, de Haar C, Lencer WI, Fiebiger E, and Blumberg RS. 2011. Neonatal Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) regulates cross-presentation of IgG immune complexes by CD8-CD11b+ dendritic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 108: 9927–9932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Major D, Chichester JA, Pathirana RD, Guilfoyle K, Shoji Y, Guzman CA, Yusibov V, and Cox RJ. 2015. Intranasal vaccination with a plant-derived H5 HA vaccine protects mice and ferrets against highly pathogenic avian influenza virus challenge. Hum. Vaccines Immunother 00–00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kubo T, Wawrzyniak P, Morita H, Sugita K, Wanke K, Kast JI, Altunbulakli C, Rückert B, Jakiela B, Sanak M, Akdis M, and Akdis CA. 2015. CpG-DNA enhances the tight junction integrity of the bronchial epithelial cell barrier. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 136: 1413–1416.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Riet E, Ainai A, Suzuki T, and Hasegawa H. 2012. Mucosal IgA responses in influenza virus infections; thoughts for vaccine design. Vaccine 30: 5893–5900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown DM, Lee S, de la L. Garcia-Hernandez M, and Swain SL. 2012. Multifunctional CD4 Cells Expressing Gamma Interferon and Perforin Mediate Protection against Lethal Influenza Virus Infection. J. Virol 86: 6792–6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Houser K, and Subbarao K. 2015. Influenza Vaccines: Challenges and Solutions. Cell Host Microbe 17: 295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laidlaw BJ, Zhang N, Marshall HD, Staron MM, Guan T, Hu Y, Cauley LS, Craft J, and Kaech SM. 2014. CD4+ T Cell Help Guides Formation of CD103+ Lung-Resident Memory CD8+ T Cells during Influenza Viral Infection. Immunity 41: 633–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McMaster SR, Wilson JJ, Wang H, and Kohlmeier JE. 2015. Airway-Resident Memory CD8 T Cells Provide Antigen-Specific Protection against Respiratory Virus Challenge through Rapid IFN-γ Production. J. Immunol 195: 203–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Slütter B, Van Braeckel-Budimir N, Abboud G, Varga SM, Salek-Ardakani S, and Harty JT. 2017. Dynamics of influenza-induced lung-resident memory T cells underlie waning heterosubtypic immunity. Sci. Immunol 2: eaag2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Erbelding EJ, Post DJ, Stemmy EJ, Roberts PC, Augustine AD, Ferguson S, Paules CI, Graham BS, and Fauci AS. 2018. A Universal Influenza Vaccine: The Strategic Plan for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. J. Infect. Dis 218: 347–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krammer F, Pica N, Hai R, Margine I, and Palese P. 2013. Chimeric Hemagglutinin Influenza Virus Vaccine Constructs Elicit Broadly Protective Stalk-Specific Antibodies. J. Virol 87: 6542–6550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ermler ME, Kirkpatrick E, Sun W, Hai R, Amanat F, Chromikova V, Palese P, and Krammer F. 2017. Chimeric Hemagglutinin Constructs Induce Broad Protection against Influenza B Virus Challenge in the Mouse Model. J. Virol 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]