Abstract

Fetal hemoglobin (HbF) induction constitutes a valuable and validated approach to treat the symptoms of sickle cell disease (SCD). Here, we synthesized pomalidomide–nitric oxide (NO) donor derivatives (3a–f) and evaluated their suitability as novel HbF inducers. All compounds demonstrated different capacities of releasing NO, ranging 0.3–30.3%. Compound 3d was the most effective HbF inducer for CD34+ cells, exhibiting an effect similar to that of hydroxyurea. We investigated the mode of action of compound 3d for HbF induction by studying the in vitro alterations in the levels of transcription factors (BCL11A, IKAROS, and LRF), inhibition of histone deacetylase enzymes (HDAC-1 and HDAC-2), and measurement of cGMP levels. Additionally, compound 3d exhibited a potent anti-inflammatory effect similar to that of pomalidomide by reducing the TNF-α levels in human mononuclear cells treated with lipopolysaccharides up to 58.6%. Chemical hydrolysis studies revealed that compound 3d was stable at pH 7.4 up to 24 h. These results suggest that compound 3d is a novel HbF inducer prototype with the potential to treat SCD symptoms.

Keywords: Fetal hemoglobin inducers, nitric oxide, NO-donors, epigenetics, pomalidomide, Sickle Cell Disease

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) is a monogenic hemoglobinopathy that affects millions of people worldwide, affecting 300,000–400,000 newborns annually, mainly in developing countries such as those in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. Despite the wide phenotypic variability of SCD, the vast majority of patients face common hallmarks of reduced life expectancy and quality of life, high medical cost, chronic pain, and lack of multiple therapeutic options.

Owing to the advances in technology in recent years, gene therapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation have been considered as potential cures; however, we are yet to overcome the challenges of finding compatible donors, allogeneic graft rejection, and high cost. Therefore, small molecule drugs are still essential to mitigate the diversity of symptoms since gene therapy and transplantation are recommended only for selective patients. Currently, four drugs are approved for SCD: hydroxyurea (HU), L-glutamine, voxelotor, and crizanlizumab [2]. Among them, HU is the oldest drug being used for almost two decades, including in pediatric patients. The drug acts by increasing the fetal hemoglobin (HbF) levels—an established and validated approach for the treatment.

Several small molecules have been identified as HbF inducers—natural products (i.e., resveratrol), metformin, methyltransferase inhibitors (i.e., azacitidine and decitabine), histone deacetylase inhibitors (i.e., butyrate and panobinostat), and immunomodulatory imide drugs (IMiDs) (i.e., thalidomide and pomalidomide) [3]. Among these, IMiDs are interesting HbF inducers prototypes and are the only ones that have showed a therapeutic effect in vivo [4]. Pomalidomide, an approved treatment for relapse and refractory multiple myeloma, regulates erythropoiesis, slows down the erythroid maturation, and upregulates γ-globin gene expression by transcriptional mechanisms. Thus, it induces potent fetal hemoglobin production without causing cytotoxic side effects common to other HbF inducers, like HU [4, 5].

Pomalidomide-dependent induction of HbF is due to reversion of γ-globin silencing in erythroblasts by targeting the transcription factors, BCL11A and SOX6, independently of IKZF1 degradation. Several γ-globin repressors have been implicated in the globin switch, such as BCL11A, SOX6, GATA-1, KLF1, and LSD1, with BCL11A being one of the most known modulators of the fetal-to-adult globin switch. Pomalidomide downregulated all these repressors, albeit to different degrees, in CD34+ cells [6].

Previously, we have demonstrated that another IMIDs (i.e. thalidomide) analogue containing a nitric oxide (NO) release subunit could induce gamma-globin expression in K562 and CD34+ cells, although at moderate levels [7–11]. In vivo studies using the transgenic sickle mice revealed that these analogs increased HbF levels, reduced the amount of proinflammatory cytokines, and surprisingly, reversed priapism [12,13].

Therefore, in a continuing effort to discover new HbF inducer agents for treating SCD and as an alternative to HU, we aimed to synthesize and evaluate the pharmacological properties of new pomalidomide analogues containing an NO donor subunit. As a potent HbF inducer, we hypothesized that conjugation of pomalidomide derivatives with NO-donor subunit could improve the HbF-inducer effect observed for its parental drug (2) and thalidomide analogues (1) previously described (Figure 1). These new derivatives could also release NO, acting through pleotropic effects useful to treat some of the SCD symptoms. The drug design explored the bioisosteric replacement of phthalimide subunit (1) to 3-amino-phthalimide present in the pomalidomide (2) (Figure 1). In addition, the molecular optimization evaluated the contribution of furoxan with different NO-release profiles. Then, we studied the mechanisms of action of the new compounds involved in the activation of γ-globin gene expression.

Figure 1.

Drug design of pomalidomide–NO donor compounds (3a–f).

2. RESULTS

2.1. Chemistry

Scheme 1 summarizes the synthesized pomalidomide derivatives (3a–f). The first step of synthesis involved the coupling of furoxan derivatives (6, 9, and 11) with hydrazides, 7a and 7b, in a solution containing ethanol and acetic acid with variable yields ranging 34–75%. The nitro group present in (4) was reduced to amino group (5) using hydrogenation reaction catalyzed by palladium on carbon (Pd/C) in acetone, at yields of 98%. In the last step, 3-aminophthalic anhydride (5) and amino derivatives (8a, b; 10a, b; and 12a, b) were condensed using 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) as coupling reagents to obtain the pomalidomide derivatives (3a–f) with yields ranging 13–43%. We evaluated the purity of all compounds (3a–f) using high performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) analysis and confirmed them to be superior to 98.5%. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra of all of the intermediates (8a, b; 10a, b; and 12a, b) and final compounds (3a–f) revealed one signal that corresponded to the ylidene hydrogen of the E-diastereomers [14,15].

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of pomalidomide derivatives with NO-donor properties (3a–f). Reagents and conditions: a) acetone, Pd/C, H2; b) aminobenzohydrazides, ethanol, H+, room temperature, 4–24 h; c) 3-aminophthalic anhydride (5), EDC, DMAP, DMF anhydrous, N2 atmosphere, room temperature, 24–30 h.

2.2. Nitrite quantification

Nitrite quantification is an indirect method to measure the ability of compounds to release NO. This assay is based on the reaction between the released NO from compounds, oxygen, and water, providing nitrite in the medium; this nitrite is further derivatized using the Griess reagent, consisting of 0.2% N-(1-naphthyl)ethylenediamine dihydrochloride, and 2% sulfanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid [16–18]. We studied the release of NO after incubating 100 μM of each of the pomalidomide derivatives (3a–f) with a large excess of L-cysteine (50 × 10−4 M) for 1 h [19]. Table 1 summarizes the main results, expressed as a percentage of nitrite (NO2−; mol/mol).

Table 1.

NO-release Data

| Compounds | % NO2− (mol/mol) 50 × 10−4 M of L-Cysa |

|---|---|

|

| |

| DNS | 12.0 ±1 |

| 3a | 5.0 ±1.0 |

| 3b | 6.3 ±0.1 |

| 3c | 28.1 ±1.0 |

| 3d | 30.3 ±3.0 |

| 3e | 1.1 ±0.1 |

| 3f | 0.3 ±0.2 |

All values are the mean ± SEM. Determined by Griess reaction, after incubation for 1 h at 37 °C in pH 7.4 buffered water, in the presence of 1:50 molar excess of L-cysteine.

DNS, isosorbide dinitrate.

Compounds 3a–f induced nitrite formation at levels ranging 1.1−30.3%, after the 1h incubation (Table 1). The control, isosorbide dinitrate (DNS), induced 12.0% nitrite formation. We observed a direct relationship between the pattern of substitution in the furoxan subunits and the ability to release NO. Furoxan subunits containing an electron-withdrawing substituent at position 3 released more NO than those containing electron-withdrawing groups at other positions. Phenyl-sulfonyl derivatives (3c–d) released high levels of NO (28.1–30.3%), followed by phenyl-furoxan derivatives (3a–b; 5.0–6.3%). Methyl-furoxan derivatives (3e–f) released low levels of NO (0.3–1.1%) under the same experimental condition. In the absence of L-cysteine, there was no detectable production of nitrite in the medium (not shown).

2.3. Evaluation of γ-globin and HbF expression in CD34+ cells

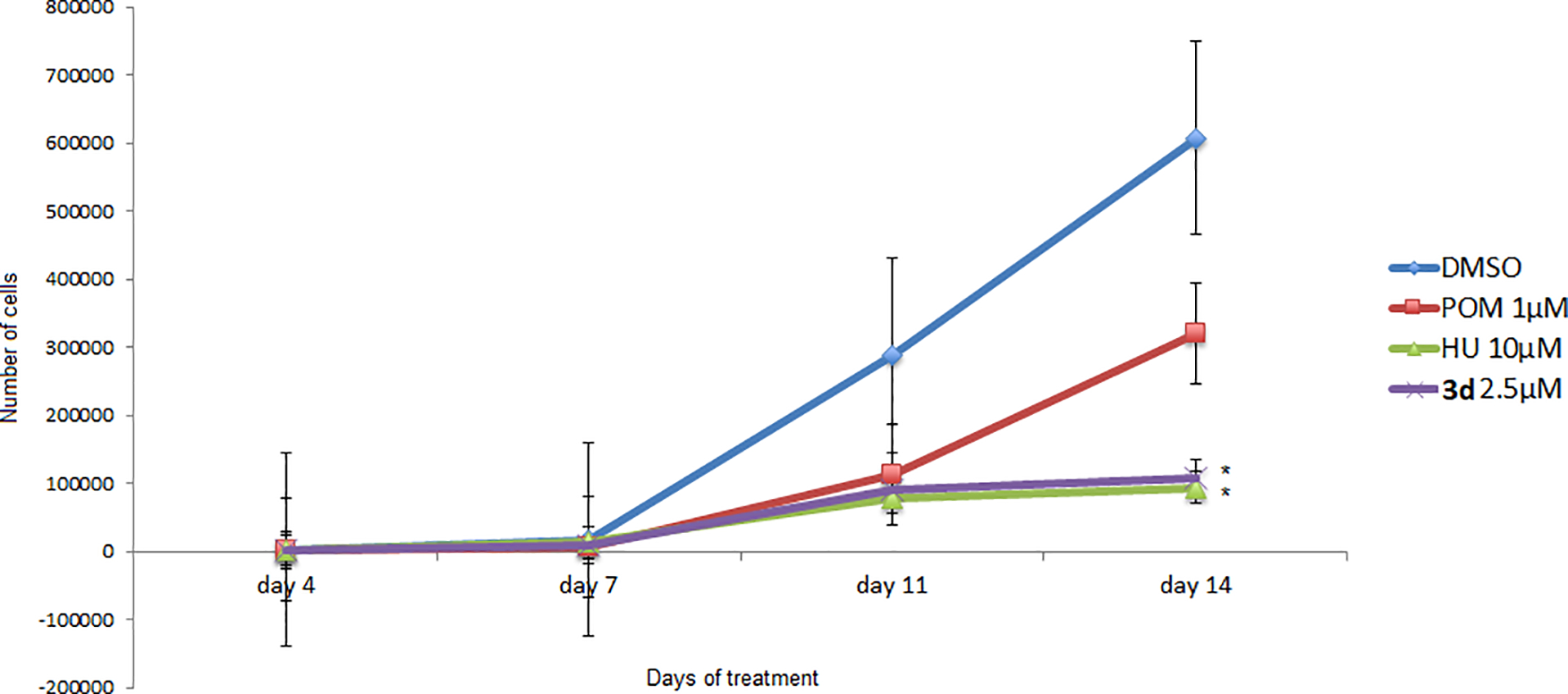

Based on the different NO-release profiles, we evaluated compounds 3b, 3d, and 3f for inducing γ-globin gene expression and HbF production using CD34+ cells. Adult peripheral blood CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells were isolated, expanded, and differentiated using a 3-phase culture system that recapitulates human erythropoiesis, including enucleation, in the presence of pomalidomide and compounds 3b, 3d, and 3f at different concentrations of 0.1 μM, 1 μM, and 10 μM [20]. After 14 days of culture, only compound 3d at 1 μM induced significant γ-globin gene expression (Figure 2A). For this compound, the concentration of 10 μM reduced substantially the number of cells, suggesting toxicity. At 2.5 μM compound 3d induced potent γ-globin gene expression, without interfere with β-globin expression (Figure 2B). At this concentration, the 3d-treated cells exhibited comparable proliferation to that of HU (10 μM)-treated cells; however, it was less potent than that of pomalidomide (1 μM)-treated cells (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Expression of γ-globin in CD34+ cells. (A) CD34+ cells were treated for 14 days with different concentrations of pomalidomide and compounds 3b, 3d, and 3f. (B) CD34+ cells were treated for 14 days with 1μM pomalidomide (POM), 10 μM hydroxyurea (HU), and 2.5 μM compound 3d. DMSO (0.1%) was used as a negative control. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blot using γ-, β-, and α-globin antibodies. The mean relative γ-globin and β-globin expression levels were normalized to that of GAPDH by analyzing the band density using ImageJ software. The error bars represent the SD from three individual experiments. *p < 0.05 compared with DMSO (ANOVA followed by Dunnet test).

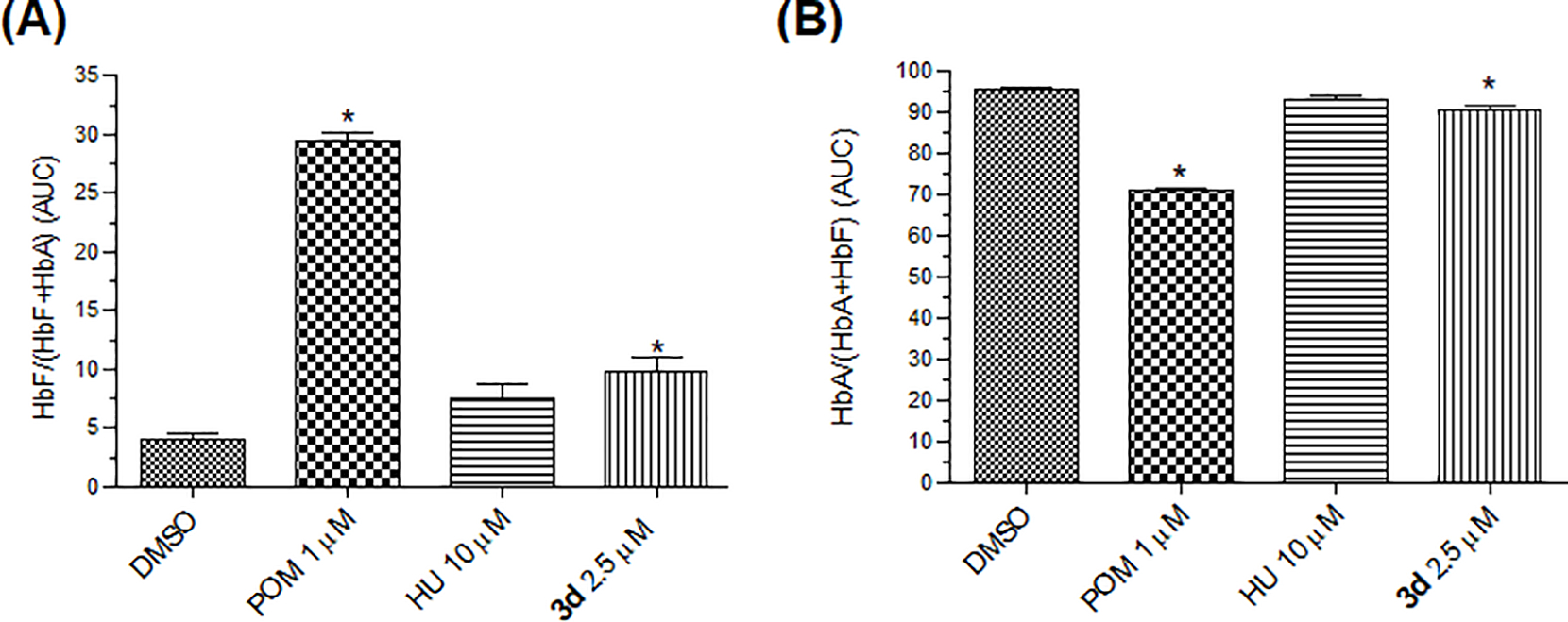

We measured HbF levels after the treatment of CD34+ cells with compound 3d, HU, and pomalidomide on day 14 using HPLC. Representative chromatograms for DMSO, pomalidomide, HU and 3d-treated cultures can be found in the supplementary material (S25–S28). The HbF level induced by 3d (2.5 μM) was significant in comparison to control (DMSO) (Figure 3). HU did not interfere in hemoglobin A (HbA) levels, whereas 3d caused a marginal reduction. The growth curves of treated CD34+ cells exhibited similar profiles for 3d (2.5 μM) and HU (10 μM) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Quantification of hemoglobin in CD34+ cells. Hemoglobin production was assessed in supernatants from H2O-lysed cells, using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Blotplots from DMSO, pomalidomide, HU, and 3d-treated cultures. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for each sample, and relative hemoglobin composition was expressed as the mean percent (A) HbF/(HbF + HbA) ±SEM (N = 3), *p < 0.05 and (B) the mean percent HbA/(HbA + HbF) ±SEM, *p < 0.05 compared with DMSO (ANOVA followed by Dunnet test).

Figure 4.

Growth curves (number of cells) for DMSO-, HU-, pomalidomide (POM)-, and 3d-treated cultures at days 4, 7, 11, and 14. The data are shown as mean cells/mL ±SEM (N = 3). *p < 0.05 compared with DMSO (ANOVA followed by Tukey test).

We monitored the terminal erythroblast differentiation at days 7, 11, and 14 of culture using flow cytometry. Erythroblasts were defined as GPApos cells, and maturation level was determined by the presence of α4-integrin and band 3 proteins [20]. Flow cytometry revealed erythroid precursors and terminal erythroblast differentiation of CD34+ cells treated with all compounds, highlighting the differentiation that occurred at day 14 (Figure 5). Moreover, we verified the cellular morphology using the May–Grunwald–Giemsa method, in which we observed the predominance of control and control processes of diseases with embryonic stem cells with proerythroblasts and basophilic erythroblasts (supplementary material).

Figure 5.

Flow cytometric characterization of erythroid precursors and terminal erythroblast differentiation. Terminal differentiation was monitored via α4-integrin and band 3 levels of GPApos cells on indicated days. Cells with α4-integrinhi/band 3 lo represent less mature erythroblasts, whereas those with α4-integrinlo/band3 hi are further differentiated (N = 3).

2.4. Investigation of mechanisms for HbF induction

2.4.1. Transcriptional/repressor factors

We evaluated the comprehensive network of transcription factors involved in the regulation of γ-globin gene expression in CD34+ cells using western blot. Among its several gene repressors, BCL11A, IKAROS, and LRF play key roles in the regulation of γ-globin gene expression [21,22]. After four days of differentiation, we observed that compound 3d (2.5 μM) and HU (10 μM) did not affect the expression of BCL11A and LRF, however an increased levels in the expression of IKAROS was observed (Figure 6). On the contrary, pomalidomide (1 μM) reduced the levels of BCL11A and IKAROS; however, the LRF levels were unaltered.

Figure 6.

(A) Western blot for BCL11A and IKAROS in CD34+ cells treated with 0.1% DMSO (negative control), 1 μM POM, 10 μM HU, and 2.5 μM compound 3d. Cell lysates were analyzed on day 4 of the treatment. The mean relative BCL11A and IKAROS expression levels were normalized to that of GAPDH by analyzing the band density using the ImageJ software. The error bars represent the SD from three individual experiments, *p < 0.05 compared with DMSO (ANOVA followed by Dunnet test). (B) Western blot for LRF in CD34+ cells treated with 0.1% DMSO, 1 μM POM, 10 μM HU, and 2.51 μM 3d at day 4 of culture. The mean relative LRF expression level was normalized to that of GAPDH by analyzing the band density using the ImageJ software. The error bars represent the SD from three individual experiments, *p < 0.05 compared with DMSO (ANOVA followed by Dunnet test).

2.4.2. Inhibition of histone deacetylase (HDAC 1 and 2)

Epigenetic enzymes, such as histone deacetylase (HDAC), regulate the γ-globin gene expression [23]. Previous studies have demonstrated that class I HDAC inhibitors, mainly those acting through HDAC-1 and HDAC-2 inhibition, can induce γ-globin gene expression and increase HbF levels in a dose-dependent manner using cultured primary cells derived from sickle cell patients [23,24]. Thus, to evaluate its ability as an HDAC inhibitor, we performed an enzymatic assay using 2.5 μM of compound 3d. The percentage of inhibition for HDAC-1 and −2 induced by 3d was 6% and 2%, respectively (Table 2). In this experiment, we used 30 nM of vorinostat (also called suberanilohydroxamic acid, SAHA) as a drug reference. At 30 nM vorinostat inhibited HDAC-1 and −2 by 87% and 72%, respectively. These data suggested that the HbF induction mechanism is unrelated to HDAC inhibition.

Table 2.

Percentage of HDAC-1 and –2 inhibition.

| % inhibition | ||

|---|---|---|

| Treatment | HDAC1 | HDAC2 |

|

| ||

| 3d * | 6 | 2 |

| vorinostat, 30 nM | 87 | 72 |

The enzymatic assays were performed in triplicate at each concentration (360 nm). The percent activity in the presence of each compound was calculated according to the following equation: % activity = (F−Fb)/(Ft−Fb), where F = fluorescent intensity in the presence of vorinostat (SAHA).

2.5 μM of compound 3d was used.

2.4.3. Quantification of cGMP levels

The activation of the soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) pathway is another mechanism that induces HbF production [25]. Since 3d acts as NO donor, soluble cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) pathway could be activated after treatment with this compound. Therefore, in this experiment, we measured the levels of cGMP in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) after incubation with 3d (2.5 μM), HU (10 μM), and pomalidomide (1 μM) or DMSO (vehicle control; 0.1%) for 24 h (Figure 7). Both HU and compound 3d elevated cGMP levels in HUVEC cells to 9.6 and 24.4 pmol cGMP/μg protein, respectively. In contrast, pomalidomide did not increase the cGMP level in HUVEC cells. Similar observation was found after measurement of cGMP levels using CD34+ cells, however, we found lesser amount of cGMP compared to HUVEC cells (supplementary material).

Figure 7.

Effects 0.1% DMSO, 1 μM POM, 10 μM HU, and 2.5 μM compound 3d on intracellular cGMP levels in HUVEC cells. HUVEC cells were used at the confluence, and the results were measured after 48 h of treatment. Values represent means ±SEM (n = 3). *p < 0.05

2.5. Measurement of TNF-α level in human mononuclear cells culture

We employed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to determine the level of the proinflammatory cytokine, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), in the supernatant of mononuclear cell cultures treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and co-incubated with either DMSO, pomalidomide, HU, or 3d (Figure 8). LPS (50 mg/mL) was used as an inflammatory stimulus (data not shown). We performed a dose-response assay to characterize the cellular viability. Only those concentrations exhibiting viability greater than 90% were considered in this study. Previously, we demonstrated that HU did not reduce TNF-α levels [8]. In this experiment, cultured cells were treated with pomalidomide (5 μM) and 3d (1 μM and 2.5 μM). All tested compounds reduced TNF-α levels compared with LPS (425 pg/mL). Compound 3d and pomalidomide exhibited comparable effects in reducing the production of this proinflammatory cytokine with TNF-α levels of 180 pg/mL (57.6%) and 176 pg/mL (58.6%), respectively (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Level of the proinflammatory cytokine, TNF-α, determined using ELISA in the supernatant of human mononuclear culture treated with LPS and co-incubated with test drugs. Pomalidomide (POM) was used as positive anti-inflammatory controls. LPS at 50 mg/mL was used as an inflammatory stimulus. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM; p < 0.05 compared with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test); N = 3 experiments; C(−) : DMSO.

2.6. In vitro stability study

To determine the in vitro stability of compound 3d at pH 1.0 and 7.4, we performed a chemical hydrolysis study using the HPLC method. After 1 h, we observed about 96% degradation of the compound at pH 1.0, suggesting that compound 3d is unstable under highly acid conditions. On the contrary, at pH 7.4 that mimics the plasma pH, the compound was stable up to 12 h, after which there was marginal degradation of 4.86% and 8.06% at 20 h and 24 h, respectively (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

In vitro determination of chemical stability for compound 3d in buffers at pH 1.0 and 7.4. Data are represented as means ±SEMs and expressed as %.

3. DISCUSSION

In recent years, novel drugs have been approved for SCD treatment; however, HU remains the only approved drug capable of increasing HbF levels. Long-term treatment using HU leads to a significant reduction of morbidity and mortality [26,27]. High levels of HbF decrease hemoglobin S polymerization inside erythrocytes; thus, preventing the sickling process. In addition, HU reduces the adhesiveness of the red blood cells, platelets, and leukocytes, preventing the vaso-occlusive process [28,29]. Despite all those beneficial effects, severe adverse events, such as myelosuppression and lack of effectiveness in a significant patient population, limit its use, justifying the need for novel HbF inducers [30].

The complex heterogeneity of SCD pathophysiology demands efforts for identifying novel compounds that act through multiple mechanisms. Previously, we demonstrated that thalidomide derivatives designed to release NO could contribute through multiple effects in SCD treatment, including HbF induction, anti-inflammatory, and antiplatelet effects [8–10,12]. Although the mechanisms of these effects of the thalidomide derivatives were not completely established, they had distinct effects compared with thalidomide [10].

Despite these effects, thalidomide is less potent than pomalidomide in inducing HbF production [4,5]. In addition, the anti-inflammatory activity of pomalidomide is greater than that of thalidomide, partially explained by its ability to inhibit TNF-α [31]. Pomalidomide also increases erythropoiesis and preserves bone marrow function [5]. Some studies suggested that the HbF-inducing mechanism of pomalidomide is selectively related to BCL11A and SOX-6 repression factors [6]. Based on all promising effects of pomalidomide, a phase I trial was conducted to assess its effectiveness, safety, and maximum tolerated dose in SCD patients treated with pomalidomide (US ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01522547). Therefore, considering the potential of pomalidomide as a novel prototype HbF-inducer, we evaluated the effectiveness of hybrid pomalidomide–NO donor subunit to optimize the beneficial effects previously identified in the thalidomide–NO donors.

Synthetic procedures allowed the preparation of compounds 3a–f through coupling reactions with yields ranging 13–43%. We chose furoxan (1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-N-oxide) as the NO-donor subunit as it is advantageous over other NO-donors (i.e., organic nitrate esters) in terms of the possibility to modulate the levels of NO released in the medium. The insertion of electron-withdrawing substituents at position 3 of furoxan enhances the NO-release compared with that of electron-enriching substituents. Therefore, for this study, we selected furoxan containing phenylsulfonyl (strong), phenyl (moderate), and methyl (weak) substituents with the aim to characterize a possible relationship between the NO release and HbF induction. We determined that the levels of nitrite ranged from 28.1–30.3% for phenylsulfonyl derivatives (3c and 3d), 5.0–6.3% for phenylfuroxan (3a and 3b), and 0.3–1.1% for methylfuroxan (3e and 3f).

In sickled cells, vascular hemolysis releases the heme group arising from hemoglobin into circulation, which reduces the endothelial NO bioavailability and favors a vasoconstrictor response. In the vascular endothelium, chronic injury associated with low levels of NO contributes to inflammation and hypercoagulability states, leading to vaso-occlusion and prothrombotic events [32]. Abnormal adhesion of erythrocytes to vascular endothelium is caused due to augmented adhesion molecules. Additional interactions with leukocytes and activated platelets induce cellular heteroaggregation that is responsible for vaso-occlusion [2,26,33].

NO has a pleiotropic effect in SCD, contributing as vasodilator; thus, decreasing platelet aggregation and cellular adhesion in the endothelium and inducing HbF production [34]. The NO-induced augmentation of HbF was a result of the activation of the sGC pathway in both erythroleukemic and primary erythroblast cells [25,35]. cFOX is a transcription factor activated by the NO/cGMP pathway; it binds to the hypersensitive site 2 in the β-globin locus control region and the Sp1 in the CACCC box [36–38].

We selected three compounds, 3b, 3d, and 3f, with different NO-release profiles to study their ability to induce γ-globin gene expression in CD34+ cells. Of these, only compound 3d induced the gene expression. It was observed an appropriate balance between optimum effect and cellular toxicity at 2.5 μM. Interestingly, this phenylfuroxan derivative (3d) was extremely potent at releasing NO; it generated around 30.3% of nitrite, suggesting that high levels of NO-release may be necessary to induce γ-globin gene expression. Both compound 3d and HU exhibited similar levels of γ-globin gene expression; however, this effect was lesser than that induced by pomalidomide. It has been reported that after metabolism, HU gets bioconverted to NO. HU-treated patients exhibited augmentation in their plasma levels of nitrite, nitrate, and iron nitrosyl hemoglobin, 2 h after the oral intake of HU [39]. Therefore, there exists a relationship between NO levels and γ-globin gene expression [10].

Distinct stresses can activate γ-globin gene expression in erythroid cells [40]. Thus, in addition to gene expression, we must measure HbF levels during phenotypic assays to avoid false-positive results. On day 14, we measured levels of HbF after treatment with compound 3d, HU, and pomalidomide in CD34+ cells. The HbF level induced by 3d (2.5 μM) was significant in comparison to control (DMSO). These results confirmed the findings observed in the gene expression assay.

We also studied the mechanism of action of 3d-induced γ-globin gene expression and HbF production. Among the several transcription factors that silence the globin genes, the effect of BCL11A is notorious; it binds within the β-globin locus and silences ε- and γ-globin gene expressions [41]. As pomalidomide downregulates several transcription factors, including BCL11A and IKAROS involved in γ-globin gene expression, we investigated similar effects for 3d [6]. Although our study confirmed that pomalidomide downregulated BCL11A and IKAROS, we did not observe such effects for both HU and 3d. On the contrary, the levels of IKAROS were slightly increased for the group treated with 3d, suggesting a different mode of action for HbF induction compared to pomalidomide. In addition, another transcription factor, leukemia/lymphoma-related factor (LRF), was not altered by pomalidomide, HU, or 3d. LRF binds DNA through its C-terminal C2H2-type zinc finger domain and recruits a transcriptional repressor complex through its N-terminal domain. LRF also represses the expression of the γ-globin gene [22].

Pomalidomide binds to cereblon, an E3 ligase protein and a substrate receptor for the CRL4 (CUL4−RBX1−DDB1) ubiquitin ligase complex, and induces the degradation of IKAROS, involved in the silencing of γ-globin genes [42]. This occurs through the combined effect of IKAROS and GATA-1, suppressing γ-globin genes [43]. Additionally, cereblon has been associated with the teratogenic effects of thalidomide [42,44]. Molecular studies revealed that the binding of IMiDs to cereblon requires the glutarimide subunit as pharmacophore [45]. In our drug design, we speculated the suppression of glutarimide subunit to eliminate the asymmetric center. The absence of glutarimide subunit for 3d could explain the lack of effect on transcription factors, such as IKAROS.

Epigenetic sites act as recognition sites that facilitate interactions with proteins or complexes and then regulate the pattern of gene expression. Similarly, chromatin remodeling is a regulated phenomenon that allows the switch between ε-, γ-, and β-globin expression during the different development stages from embryo to adulthood. The regulation of γ-globin gene expression involves several epigenetic mechanisms, including histone acetylation and methylation [36]. Since the discovery of the effect of butyrate on rising HbF levels, HDAC inhibitors have received attention as promising inducers of HbF [2]. It was demonstrated that selective inhibition of HDAC class I, specifically HDAC-1 and −2, increases HbF levels without interfering with cell cycle proliferation [23]. To assess the inhibitory effect of 3d on HDAC-1 and −2, we performed an enzymatic assay that revealed extremely weak inhibition of these enzymes by 3d. At 2.5 μM, compound 3d inhibited only 6% and 2% of HDAC-1 and −2, respectively, suggesting that it did not induce HbF via this mechanism.

Based on the NO-release effect of 3d, we investigated the activation of the sGC pathway. We measured the levels of cGMP in HUVEC cells after incubation with 3d (2.5 μM), HU (10 μM), and pomalidomide (1 μM) or DMSO (vehicle control). Pomalidomide did not affect cGMP levels. Conversely, compound 3d was 2.5-fold more potent than HU in increasing the cGMP level. The activation of the NO–cGMP pathway increases Jun mRNA levels [46, 47], which modulate γ-globin gene expression through a cAMP response element (CRE). The way CRE acts is comparable with that of transcription factor CRE binding protein 1 (CREB1) [48]. Increased levels of NO and cGMP were also related to the increase in phosphorylation of p38 MAPK [49]. Additionally, CREB1 activated γ-globin gene expression through the p38 MAPK pathway in erythroid cells [50]. Thus, the NO–cGMP pathway can stimulate the expression of the γ-globin gene through the pathways involving both p38 MAPK and JUN.

Despite its effectiveness as an HbF inducer, in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that HU did not reduce the levels of TNF-α. High levels of this pro-inflammatory cytokine is commonly found in SCD patients [8,12,52]. The high levels of TNF-α contribute to an increase in adhesion molecules (i.e., ICAM and VCAM-1), worsening vaso-occlusion, and maintaining active chronic inflammation with the recruitment of inflammatory cells [53]. Moreover, TNF-α acts directly on the nociceptor, contributing to the primary complaint of chronic pain in sickle cell patients [54,55].

Our results demonstrated that both 3d and pomalidomide reduce the levels of TNF-α in the supernatants of human mononuclear cultures treated with LPS. We did not observe differences between 3d and pomalidomide; but 3d was more potent than the thalidomide derivatives previously described [10]. Based on the structure activity relationship for phthalimide derivatives and its effect of reducing TNF-α levels, it is possible to comprehend that the 3-amino-phthalimide subunit, found for 3d, is the pharmacophore responsible for the anti-inflammatory effect [8–11]. In addition, it is notorious that this compound was stable at pH 7.4 up to 12 h; however, it was unstable in acidic conditions; thus, demanding appropriate formulation for further studies.

4. CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we successfully synthesized a novel series of pomalidomide derivatives with NO-donor properties (3a–f) and evaluated their suitability as HbF inducers for SCD treatment. The new pomalidomide derivatives were optimized aiming to not only induce HbF production, but also contribute for pleiotropic effects by releasing NO. The derivatives (3a–f) released 0.3–30.3% of nitrite in the medium. Strong NO-donor, such as phenylsulfonyl 3d, was able to induce gamma-globin gene expression at profile similar to that of HU. Compound 3d also induced HbF production and did not alter the expression of transcription factors involved in the γ-globin gene regulation, such as BCL11A and LRF. Although, a slightly increase in the levels of IKAROS was found. Compound 3d did not inhibit the enzymes, HDAC-1 and −2, involved in the regulation of gamma-globin gene expression. Interestingly, 3d significantly increased the levels of cGMP in HUVEC cells compared with HU, while pomalidomide did not exhibit this effect. Moreover, it reduced TNF-α levels in mononuclear cells treated with LPS, similar to the effect of pomalidomide. Although unstable in acid conditions, 3d exhibited good chemical stability at pH 7.4 up to 24 h. In summary, compound 3d emerged as a novel HbF inducer with anti-inflammatory properties and may prove useful as an alternative to treat the symptoms of SCD.

5. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

5.1. Chemistry. General Information

Reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial suppliers at reagent purity grade and were used without any further purification. Dry solvents used in the reactions were obtained by distillation of technical grade materials over appropriate dehydrating agents. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC), precoated with silica gel 60 (HF-254; Merck) to a thickness of 0.25 mm, was used for monitoring all reactions. The plates were revealed under UV light (254 nm). All compounds were purified on a chromatography column with silica gel (60 Å pore size, 35–75-μm particle size) and the following solvents were used as mobile phase: dichloromethane, hexane, ethyl acetate and petroleum ether. In addition, the purity analyzed by HPLC for all tested compounds was superior to 98%. Melting points (mp) were determined in open capillary tubes using an electrothermal melting point apparatus (SMP3; Bibby Stuart Scientific). Infrared (IR) spectroscopy (KBr disc) was performed on an FTIR-8300 Shimadzu spectrometer, and the frequencies are expressed per cm−1. The nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) for 1H and 13C of all compounds were scanned on a Bruker Fourier with Dual probe 13C/1H (300-MHz) NMR spectrometer using dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6), as solvent. Chemical shifts were expressed in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane. The signal multiplicities are reported as singlet (s), doublet (d), doublet of doublet (dd), and multiplet (m). Chemical shifts were expressed in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane. Elemental analyses (C, H, and N) were performed on a Perkin-Elmer model 240C analyzer, and the data were within ±0.4% of the theoretical values.

5.2. General Procedures for the Synthesis of N-oxide derivatives (8a-b; 10a-b and 12a-b)

Compounds 5, 6, 9 and 11 were synthesized according to previously described methodologies [38,56,57]. In a nitrogen atmosphere, an equivalent amount of furoxan derivatives (6, 9 or 11) (1.5 mmol) and 2- (7a) or 3-aminobenzhydrazides (7b) (1.5 mmol) was stirred under room temperature at different times (4–24h) in a medium containing ethanol and 0.1 mL of anhydrous acetic acid. The reaction was monitored by TLC using as a mobile phase a mixture of hexane (50%): ethyl acetate (50%). After, it was carried out a filtration under reduced pressure to collect N-oxide intermediates (8a-b; 10a-b and 12a-b), which were washed with cold ethanol to remove residual reagents. If necessary, an additional purification was performed by column chromatography using Isolera Biotage equipment, using a 20μm (25g) Sphere silica column, with a flow rate of 25 ml / min and phase mobile 50% ethyl acetate / 50% hexane. The N-oxide derivatives (8a-b; 10a-b and 12a-b) were obtained at yields ranging from 34–75%.

(E)-4-(4-((2-(2-aminobenzoyl)hydrazono)methyl)phenoxy)-3-phenyl-1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-N-oxide (8a)

White powder; yield: 55%; mp: 201–203°C. IR max (cm−1; KBr pellets): 3113 (C-H aromatic), 2928 (C-H alkyl), 1636 (C=C aromatic), 1479 (C=C aromatic), 1382 (N-O oxide). 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 11.69 (s, 1H), 8.41 (s, 1H,), 8.07 (dd, 2H), 7.8 (dd, 2H, J=7.8Hz), 7.55–7.65 (m, 6H), 7.18 (t, 1H, J= 8.0Hz e J= 1.7Hz ), 6.77 (dd, 2H, J= 7.0Hz), 6.55 (ddd, 1H, J= 7.0Hz), 6.39 (s, 2H, NH2). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 161.92, 153.64, 150.13, 132.95, 132.85, 131.01, 129.17, 128.67, 126.73, 121.71, 120.60, 116.44, 114.69, 108.41. Anal. Calcd (%) for C22H17N5O4: C: 63.61; H: 4.13; N: 16.86. Found: C: 63.64; H: 4.14; N: 16.87. (MW: 415.14, Rf: 0.27, eluent hexane: ethyl acetate 1: 1 (v/v)).

(E)-4-(4-((2-(4-aminobenzoyl)hydrazono)methyl)phenoxy)-3-phenyl-1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-N-oxide (8b)

White powder; yield: 63%; mp: 217–219°C. IR max (cm−1; KBr pellets): 3111 (C-H aromatic), 2926 (C-H alkyl), 1638 (C=C aromatic), 1475 (C=C aromatic), 1382 (N-O oxide). 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 11.54 (s, 1H); 8.42 (s, 1H), 8.08 (dd, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.82 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.58 – 7.63 (m, 3H), 7.60 (m, 4H), 6.60 (dd, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 5.81 (s, 2H, NH2). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 161.94, 153.51, 152.42, 133.03, 131.02, 129.17, 128.55, 126.73, 121.71, 120.58, 119.43, 112.69, 108.40. Anal. Calcd (%) for C22H17N5O4: C: 63.61; H: 4.13; N: 16.86. Found: C: 63.63; H: 4.15; N: 16.86. (MW: 415.14, Rf: 0.30, eluent hexane: ethyl acetate 1: 1 (v/v)).

(E)-4-(4-((2-(2-aminobenzoyl)hydrazono)methyl)phenoxy)-3-(phenylsulfonyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-N-oxide (10a)

White powder; yield: 59%; mp: 175–178°C. IR max (cm−1; KBr pellets): 3108 (C-H aromatic), 2927 (C-H alkyl), 1636 (C=C aromatic), 1480 (C=C aromatic), 1381 (N-O oxide). 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 11.70 (s, 1H), 8.42 (s, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.93 (t, J = 7.5 Hz e J= 1.2, 1H), 7.87 – 7.73 (m, 4H), 7.55 (m, 3H), 7.21 (t, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (t, J= 7.5 Hz and J= 1.5, 1H), 6.40 (s, 2H, NH2). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 158.23, 153.59, 150.13, 136.92, 136.35, 132.94, 132.40, 130.10, 128.69, 120.15, 116.43, 114.68, 111.37. Anal. Calcd (%) for C22H17N5O6S: C: 55.11; H: 3.57; N: 14.61. Found: C: C: 55.10; H: 3.57; N: 14.63. (MW: 479.47, Rf: 0.15, eluent hexane: ethyl acetate 1: 1 (v/v)).

(E)-4-(4-((2-(4-aminobenzoyl)hydrazono)methyl)phenoxy)-3-(phenylsulfonyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-N-oxide (10b)

White powder; yield: 75%; mp: 173–175°C. IR max (cm−1; KBr pellets): 3110 (C-H aromatic), 2925 (C-H alkyl), 1638 (C=C aromatic), 1477 (C=C aromatic), 1382 (N-O oxide). 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 11.52 (s, 1H), 8.42 (s, 1H), 8.06 (dd, 2H, J= 8 Hz), 7.77–7.94 (m, 5H), 7.67 (dd, 2H, J= 7.5Hz), 7.51 (dd, 2H, J= 7.5Hz), 6.6 (dd, 2H, J= 8.0Hz), 5.8 (2H, s, NH2). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 158.65, 153.83, 152.82, 144.96, 136.75, 130.51, 129.98, 129.91, 128.57, 120.54, 119.65, 113.07, 111.75. Anal. Calcd (%) for C22H17N5O6S: C: 55.11; H: 3.57; N: 14.61. Found: C: C: 55.15; H: 3.58; N: 14.62. (MW: 479.47, Rf: 0.22, eluent hexane: ethyl acetate 1: 1 (v/v)).

(E)-4-(4-((2-(2-aminobenzoyl)hydrazono)methyl)phenoxy)-3-methyl-1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-N-oxide (12a)

White powder; yield: 65%; mp: 165–168°C. IR max (cm−1; KBr pellets): 3103 (C-H aromatic), 2924 (C-H alkyl), 1635 (C=C aromatic), 1475 (C=C aromatic), 1381 (N-O oxide). 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 11.67 (1H, s), 8.41 (1H, s), 7.80 (2H, dd, J = 8Hz), 7.48–7.57 (3H, m), 7.2 (1H, ddd, J = 7Hz), 6.75 (1H, dd, J = 7Hz), 6.57 (1H, J = 8Hz), 6.39 (s, 2H), 2.13 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 165.73, 163.30, 154.02, 150.40, 145.70, 132.64, 129.05, 120.48, 116.68, 114.91, 113.64, 107.94, 7.29. Anal. Calcd (%) for C17H15N5O4: C: 57.79; H: 4.28; N: 19.82. Found: C: 57.81; H: 4.29; N: 19.82. (MW: 353.33, Rf: 0.22, eluent dichloromethane (95%): methanol (5%)).

(E)-4-(4-((2-(4-aminobenzoyl)hydrazono)methyl)phenoxy)-3-methyl-1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-N-oxide (12b)

White powder; yield: 66%; mp: 160–162°C. IR max (cm−1; KBr pellets): 3101 (C-H aromatic), 2925 (C-H alkyl), 1634 (C=C aromatic), 1475 (C=C aromatic), 1382 (N-O oxide). 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 11.51 (s, 1H), 8.41 (s, 1H), 7.80 (dd, 2H, J = 8 Hz), 7.67 (dd, 2H, J = 7.5Hz), 7.50 (dd, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz), 6.60 (dd, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz), 5.80 (s, 2H), 2.13 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 162.98, 153.58, 152.47, 144.75, 132.79, 129.08, 128.64, 120.08, 119.40, 112.71, 107.74, 7.14. Anal. Calcd (%) for C17H15N5O4: C: 57.79; H: 4.28; N: 19.82. Found: C: 57.83; H: 4.29; N: 19.85. (MW: 353.33, Rf: 0.15, eluent dichloromethane (95%): methanol (5%)).

5.3. General Procedures for the pomalidomide-NO donor derivatives (3a-f)

In a nitrogen atmosphere, a mixture containing 3-amino-phthalic anhydride (5) (1 mmol), N-ethyl-N′-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) (1.5 mmol), N-oxide derivatives (8a-b; 10a-b and 12a-b) (2 mmol) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (0.2 mmol) in 20 mL of dry dimethylformamide (DMF) was stirred and maintained at room temperature for 24–30h. After, it was added around 10 mL of ice-water to precipitate the compounds (3a-f), which were collected by filtration under reduced pressure and washed with cold water to remove residual reagents. If necessary, an additional purification was performed by column chromatography using Isolera Biotage equipment, using a 20μm (25g) Sphere silica column, with a flow rate of 25 ml / min and phase mobile 50% ethyl acetate / 50% hexane. The pomalidomide NO-donor derivatives (3a-f) were obtained at yields ranging from 13–43%.

(E)-4-(4-((2-(2-(4-amino-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)benzoyl)hydrazono)methyl)phenoxy)-3-phenyl-1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-N-oxide (3a)

Yellowish powder; yield: 32%; mp: 250–252°C. IR max (cm−1; KBr pellets): 3061 (C-H aromatic), 2929 (C-H alkyl), 1776 and 1721 (C=O imide), 1608 (C=C aromatic), 1472 (C=C aromatic), 1362 (N-O oxide). 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 12.11 (s, 1H), 8.36 (s, 1H), 8.07 (dd, J= 8,0 Hz, 2H), 7.78– 7.83 (m, 3H), 7.58–7.56 (m, 6H), 7.54 – 7.47 (m, 3H), 7.02 −7.06 (m, 2H), 6.53 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 168.34, 167.12, 162.62, 161.85, 153.82, 146.91, 146.34, 135.43, 132.67, 132.36, 130.97, 129.15, 128.88, 126.71, 121.68, 120.54, 111.06, 109.11, 108.40. Anal. Calcd (%) for C30H20N6O6: C, 64.28; H, 3.60; N, 14.99. Found: C, 64.29; H, 3.59; N, 14.99. (MW: 545.50, Rf: 0.10, eluent ether petroleum (55%): ethyl acetate (45%)).

(E)-4-(4-((2-(4-(4-amino-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)benzoyl)hydrazono)methyl)phenoxy)-3-phenyl-1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-N-oxide (3b)

Yellowish powder; yield: 43%; mp: 205–208°C. IR max (cm−1; KBr pellets): 3060 (C-H aromatic), 2930 (C-H alkyl), 1779 and 1720 (C=O imide), 1607 (C=C aromatic), 1470 (C=C aromatic), 1361 (N-O oxide). 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 12.04 (s, 1H), 8.48 (s, 1H), 8.09–8.02 (m, 4H), 7.90 (dd, 2H), 7.61–7.51 (m, 8H), 7.09– 7.05 (m, 2H), 6.58 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 168.54, 167.33, 163.29, 162.30, 154.27, 147.46, 147.37, 136.14, 132.45, 131.45, 129.59, 129.37, 128.65, 127.33, 127.15, 122.16, 122.03, 121.05, 111.73, 109.06, 108.84, 40.16, 40.02, 39.88, 39.74, 39.60, 39.46, 39.32, 30.85. Anal. Calcd (%) for C30H20N6O6: C, 64.28; H, 3.60; N, 14.99. Found: C, 64.27; H, 3.61; N, 14.98. (MW: 545.50, Rf: 0.32, eluent ether petroleum (55%): ethyl acetate (45%)).

(E)-4-(4-((2-(2-(4-amino-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)benzoyl)hydrazono)methyl)phenoxy)-3-(phenylsulfonyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-N-oxide (3c)

Yellowish powder; yield: 13%; mp: 216–218°C. IR max (cm−1; KBr pellets): 3058 (C-H aromatic), 2931 (C-H alkyl), 1780 and 1720 (C=O imide), 1610 (C=C aromatic), 1465 (C=C aromatic), 1360 (N-O oxide). 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 12.06 (s, 1H), 8.48 (s, 1H), 8.06 (d, 2H, J= 7.1 Hz, 2H), 8.02 (dd, 1H, J= 8.0), 7.89 (dd, 2H), 7.63–7.59 (m, 7H), 7.52 (ddd, 1H, J= 7,0), 7.09 (dd, 1H, J= 7.08), 7.05 (dd, 1H, J= 7,07), 6.58 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 168.54, 167.35, 163.36, 162.30, 147.44, 136.17, 135.52, 132.58, 132.43, 131.47, 129.60, 129.40, 128.66, 127.36, 127.16, 122.24, 122.00, 121.05, 111.78, 109.05, 108.85. Anal. Calcd (%) for C30H20N6O8S: C, 57.69; H, 3.23; N, 13.46. Found: C, 57.70; H, 3.24; N, 13.46. (MW: 624.58, Rf: 0.20, eluent ether petroleum (55%): ethyl acetate (45%)).

(E)-4-(4-((2-(4-(4-amino-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)benzoyl)hydrazono)methyl)phenoxy)-3-(phenylsulfonyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-N-oxide (3d)

Yellowish powder; yield: 20%; mp: 221–223°C. IR max (cm−1; KBr pellets): 3057 (C-H aromatic), 2927 (C-H alkyl), 1775 and 1718 (C=O imide), 1610 (C=C aromatic), 1461 (C=C aromatic), 1361 (N-O oxide). 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 12.02 (s, 1H), 8.49 (s, 1H), 8.02–8.07 (m, 4H), 7.74–7.94 (m, 5H), 7.49–7.62 (m, 5H), 7.03–7.09 (m, 2H), 6.61 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 167.82, 166.58, 162.42, 157.96, 153.46, 146.80, 146.39, 136.63, 136.06, 135.36, 134.75, 132.39, 131.91, 129.81, 128.63, 128.36, 127.93, 126.59, 121.68, 119.89, 111.00, 110.90, 108.39. Anal. Calcd (%) for C30H20N6O8S: C, 57.69; H, 3.23; N, 13.46. Found: C, 57.68; H, 3.24; N, 13.45. (MW: 624.58, Rf: 0.30, eluent ether petroleum (55%): ethyl acetate (45%)).

(E)-4-(4-((2-(2-(4-amino-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)benzoyl)hydrazono)methyl)phenoxy)-3-methyl-1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-N-oxide (3e)

White powder; yield: 15%; mp: 217–220°C. IR max (cm−1; KBr pellets): 3060 (C-H aromatic), 2933 (C-H alkyl), 1778 and 1720 (C=O imide), 1600 (C=C aromatic), 1475 (C=C aromatic), 1358 (N-O oxide). 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 12.1 (s, 1H), 8.35 (s, 1H), 7.77–7.81 (m, 2H), 7.71–7.62 (dd, 2H, J= 7Hz), 7.54–7.52 (m, 4H), 7.02–7.06 (m, 2H), 6.87 (dd, 1H), 6.57 (s, 2H), 2.11 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 168.4, 167.18, 162.87, 153.90, 151.51, 146.90, 146.40, 139.30, 135.64, 132.60, 132.17, 130.44, 128.16, 125.01, 128.16, 125.01, 121.68, 120.01, 111.21, 108.67, 107.75, 7.02. Anal. Calcd (%) for C25H18N6O6: C, 60.24; H, 3.64; N, 16.86. Found: C, 60.26; H, 3.65; N, 16.85. (MW: 498.45, Rf: 0.22, eluent ether petroleum (55%): ethyl acetate (45%)).

(E)-4-(4-((2-(4-(4-amino-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)benzoyl)hydrazono)methyl)phenoxy)-3-methyl-1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-N-oxide (3f)

White powder; yield: 19%; mp: 218–221°C. IR max (cm−1; KBr pellets): 3059 (C-H aromatic), 2930 (C-H alkyl), 1777 and 1719 (C=O imide), 1608 (C=C aromatic), 1470 (C=C aromatic), 1360 (N-O oxide). 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 12.02 (s, 1H), 8.49 (s, 1H), 8.02 (dd, J= 8.0Hz, 2H), 7.88 (dd, J= 8Hz, 2H), 7.63 (d, 2H, J=7.5Hz), 7.5 (dd, 2H, J= 7.5Hz), 7.06–7.10 (m, 2H), 6.87(m, 1H), 6.61 (s, 2H), 2.13 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ ppm) δ: 168.10, 166.86, 162.77, 153.90, 151.51, 147.08, 146.75, 139.24, 135.64, 135.10, 132.19, 130.88, 128.92, 128.14, 126.86, 124.96, 121.75, 119.97, 111.18, 108.67, 107.68, 7.02. Anal. Calcd (%) for C25H18N6O6: C, 60.24; H, 3.64; N, 16.86. Found: C, 60.25; H, 3.63; N, 16.84. (MW: 498.45, Rf: 0.4, eluent ether petroleum (55%): ethyl acetate (45%)).

5.4. Pharmacology

5.4.1. Quantification of nitrite

The quantification of nitrite in the medium was characterized using Griess reaction after incubation of all compounds (3a-f) according procedures previously described [8,9,38]. All experiments were carried out in triplicate and repeated three independent times. In the conditions without L-cysteine was nor observed nitrite formation. The results were shown as a percentage of nitrite (% NO2−; mol/mol) and for statistical analysis was used ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Test at a significance level of p < 0.05.

5.4.2. Evaluation of gamma-globin expression using CD34+ cells

CD34+ cells were isolated from de-identified control patient peripheral blood leukoreduction filters. To limit variability from one individual to another, CD34+ isolated from 20 leukoreduction filters were pooled for each experiment. Blood components were separated using Ficoll-Opaque, and CD34+ cells were purified using anti-CD34 manual cell separation columns and conjugated microbeads according to manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi). Isolated peripheral blood CD34+ cells were expanded in H3000 media supplemented with CC100 (Stem Cell Technologies) for 4 days at a density of 105 cells/mL. CD34+ cells were differentiated toward erythrocytes using an adapted version of a previously described in vitro 3-phase culture system [20].Briefly, CD34+ cells were cultured in 3% (vol/vol) AB serum, 2% (vol/vol) human plasma, 10μg/mL insulin, 3U/mL heparin, 200μg/mL transferrin supplemented with either 10ng/mL stem cell factor (SCF), 1ng/mL interleukin-3 (IL-3) and 3IU/mL erythropoietin (EPO) (Phase I; D0–7) or 10ng/mL SCF and 3IU/mL EPO (Phase II; D7–11) or 1mg/Ml transferrin and 3IU/mL EPO (Phase III; D11–16). The treatments (0.1–10 μM pomalidomide, 10 μM HU, 0.1–10 μM compounds 3b, 3d, 3f and DMSO) were added to erythroid differentiation cultures at every culture medium change.

Western Blot:

Cells were lysed in 1X RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific) supplemented with 1:100 protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Aldrich) on ice, and then centrifuged at maximum speed. Supernatants were mixed 1:1 with 2X Laemmli sample buffer (BioRad) under reducing conditions and boiled for 5 min. Following this, samples were separated via sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) for 1.5 hour at 110V, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for 1 hr at 90V. Membranes were blocked with 4% (wt/vol) milk 1% (wt/vol) BSA 1X Phosphate Buffer Saline 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween20 (PBS-T), and incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4°C: BCL11-A (Abcam, MA), IKAROS (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, CA), (Abcam, MA), and α-globin (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, CA), β- globin (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, CA), γ-globin (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, CA), and GAPDH (Millipore, Germany). Membranes were washed 3 times with PBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1h at room temperature (RT). Bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Thermo Scientific). All western blots presented in the manuscript are representative of multiple experiments, as detailed in the figure legend section. Quantifications were obtained with ImageJ software.

High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

At D14 of differentiation, 5×105 cells were pelleted and lysed with 100 μL H2O on ice for 30 min. Alternatively, 1μL of packed RBCs derived from cord or peripheral blood was pelletized and lysed with 500 μL H2O on ice for 30 min. Following centrifugation at max speed, hemolysates were collected, and hemoglobin molecules were measured using a polyCAT HPLC column (100×4.6-mm, 3μm, 1000Å) (PolyLC inc., MD) and dual wavelength absorbance at 415 and 690 nm. Hemoglobin content was calculated by integrating the area under the curve of chromatograms, and expressed as a percent of total hemoglobin (HbA + HbF, normal controls).

Flow cytometric analysis of erythropoiesis.

Terminal erythroblast differentiation was monitored at D7 and 14 of culture. Cells were pelleted and stained with a cocktail of antibodies consisting of an anti-band 3 FITC-conjugated (produced by Dr. Mohandas Narla), anti-GPA PE-conjugated, and anti- α4-integrin APC-conjugated (MACS) antibodies for 15 min at RT. Erythroblasts were defined as GPApos cells, and the level of maturation was determined by α4 and band 3 expression. Immature erythroblasts (i.e. proerythroblasts) were α4-integrinhi/band 3lo more differentiated erythroblasts such as orthochromatic and reticulocytes represent α4-integrinlo/band 3hi populations. Dead cells were excluded from analysis through 7-AAD staining. Flow cytometric analyses were performed on a BD Fortessacytometer and FlowJo software. Unless otherwise indicated, all antibodies used were from BD Biosciences.

5.4.4. Histone deacetylase inhibition

Compound 3d was evaluated through an in vitro enzymatic assay using recombinant HDAC-1 and HDAC-2. This compound was dissolved in DMSO at initial concentration of 1 mM. After, it will then get directly diluted 10x fold into assay buffer for an intermediate dilution of 10 % DMSO in HDAC assay buffer and 5 μL of the dilution was added to a 50 μL reaction so that the final concentration of DMSO is 1 % in all of reactions. The enzymatic reactions for the HDAC enzymes were carried out in triplicate at 37°C for 30 minutes in a 50 μL mixture containing HDAC assay buffer, 5 μg BSA, an HDAC substrate (10 μM HDAC Substrate 3; BPS Bioscience, #50037), a HDAC enzyme (HDAC-1, 7.2 ng/reaction, BPS Bioscience, catalog #50051; and HDAC-2, 7.2 ng/reaction, BPS Bioscience, catalog #50052) and compound 3d (0.3 μM) or vorinostat at 3 nM and 30 nM. After enzymatic reactions, 50 μL of 2x HDAC Developer ((BPS Bioscience, catalog #50030) was added to each well for the HDAC enzymes and the plate was incubated at room temperature for an additional 15 minutes. Fluorescence intensity was measured at an excitation of 360 nm and an emission of 460 nm using a Tecan Infinite M1000 microplate reader. HDAC activity assays were performed in triplicate, in three different experiments. The fluorescent intensity data were analyzed using the computer software, Graphpad Prism. In the absence of the compound, the fluorescent intensity (Ft) in each data set was defined as 100% activity. In the absence of HDAC, the fluorescent intensity (Fb) in each data set was defined as 0% activity. The percent activity in the presence of each compound was calculated according to the following equation: % activity = (F-Fb)/(Ft-Fb), where F= the fluorescent intensity in the presence of the compound.

5.4.5. Quantification of cGMPc levels

The levels of intracellular accumulation of cGMP were quantified using HUVEC cells [58]. HUVEC cells were grown in 60 mm plates in medium M199 supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum, 200 Ag/ml endothelial cell growth supplement, 4 U/ml heparin sodium, 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin and 50 Ag/ml gentamycin. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 100% humidity and used when in confluence. The cells were treated and incubated for a period of 4 h. The incubation with the tested compounds was interrupted by removing the supernatant from the culture and the cells were then immediately covered with lysis buffer and scraped off. The extract was collected, centrifuged for 5 min at 5000x g and stored at −20 °C until analyzed. To normalize the cGMP values, the protein content in each well was measured by Bradford trial assay and normalized to have the same concentration in a final volume of 250uL. Results were presented in order of fmol cGMP / μg of protein. Intracellular cGMP levels were measured using the kit GMPc EIA (R & D Systems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

5.4.6. Cellular viability and measurement of TNF-α level in macrophage cells

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medical Sciences of UNICAMP, under No. 1,169,997 and CAAE no.: 45878215.8.0000.5404. Human mononuclear cells were separated from peripheral blood by Ficoll gradient (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and subsequently Percoll 45% (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) to obtain a more purified cell population. After, a volume of 100 μL containing 5 × 106 cells suspended in RPMI medium and 10% of calf bovine serum was added to the 24-well plates and incubated for 1h (37 °C, atmosphere 5% of CO2). Those non-adherent cells in the supernatant were discarded. Thus, it was added lipopolysaccharide (Escherichia coli 0111B) (LPS) (10 mg/mL) dissolved in RPMI medium and 10% of calf bovine serum and the plates were incubated once again for 24h in the same conditions. Then, a volume of 100 μL of a aqueous solution of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)–2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) (1 mg/mL) was added to each well and incubated for more 3 hours. The supernatant was discarded, and an amount of 100 μL of isopropyl alcohol was added. The absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a microplate reader spectrophotometer (BioTek®) and the results expressed as means ± SEM of the percentage of viable cells. The TNF-α quantification was performed using ELISA in the culture supernatant. All quantifications were performed using the BD OptEIA ELISA kit (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration used for reference drugs pomalidomide was 5 μM, while for compound 3d it was 2.5 μM. In all of those concentrations the cellular viability was superior to 90%. The results were expressed as means ± SEM of the amount of TNF-α in pg/mL. Both cellular viability and TNF-α quantification experiments were carried out in triplicate in distinct three experiments. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Test as a post hoc test was performed using the software Graph-Pad InStat version 3.00 for Windows 95 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, U.S.A.). The statistical significance was defined as a p-value <0.05.

5.4.7. In vitro stability study

The chemical stability of compound 3d was evaluated in vitro at pHs 1.2 and 7.4 using an HPLC method. The hydrolysis study with compound 3d was conducted using a Phenomenex Luna reverse-phase C18 (2)-HTS column (2.5-μm particle, 2 by 50 mm) in isocratic flow 50:50 (water: 0,1 % formic acid-acetonitrile, v/v) at flow rate of 0.25 mL/min. The HPLC was coupled to a API 2000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with a heated electrospray ionization interface (H-ESI) operated in the positive ionization mode at capillary voltage 5200 V, source temperature 350 °C, nitrogen gas flow 65 units. For chemical hydrolysis, an initial solution in acetonitrile of compound 3d at 1000 μM and after diluted to 10 μM using different PBS buffers (phosphate-buffered saline) to maintain the pHs: 1.2 and 7.4. During the assay, all samples were maintained at constant agitation using a shaker (400 rpm) at 37 °C. An aliquot of 5 μL was taken from the solution at the following times: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 12, 20 and 24 h and injected in HPLC. All analyses were conducted in triplicate, and the results were expressed as the averages of the concentrations in percentages (± standard error of the mean [SEM]).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Discovery of pomalidomide–nitric oxide donor derivatives useful for sickle cell disease treatment.

Compounds with different nitric oxide release profiles.

Compound 3d was the most effective fetal hemoglobin inducer for CD34+ cells.

Compound 3d significantly increased the levels of cGMP.

Compound 3d demonstrated a potent anti-inflammatory effect.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP Ref. Process: 2010/12495-6, 2011/15204-5, 2013/04244-1, 2014/06755-6, 2014/00984-3, 2015/19531-1 and 2016/09502-7), Programa de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Científico da Faculdade de Ciências Farmacêuticas da UNESP - PADC and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq Ref. Process: 479468/2013-3 and 310026/2011-3), the National Institutes of Health HL144436 (to LB).

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Kato GJ, Piel FB, Reid CD, Gaston MH, Ohene-Frempong K, Krishnamurti L, Smith WR, Panepinto JA, Weatherall DJ, Costa FF, Vichinsky EP, Sickle cell disease, Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim 4 (2018) 18010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pavan AR, dos Santos JL, Advances in Sickle Cell Disease Treatments, Curr. Med. Chem (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Paikari A, Sheehan VA, Fetal haemoglobin induction in sickle cell disease, Br. J. Haematol 180 (2018) 189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Parseval LAM, Verhelle D, Glezer E, Jensen-Pergakes K, Ferguson GD, Corral LG, Morris CL, Muller G, Brady H, Chan K, Pomalidomide and lenalidomide regulate erythropoiesis and fetal hemoglobin production in human CD34+ cells, J. Clin. Invest 118 (2008) 248–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Meiler SE, Wade M, Kutlar F, Yerigenahally SD, Xue Y, Parseval LAM, Corral LG, Swerdlow PS, Kutlar A, Pomalidomide augments fetal hemoglobin production without the myelosuppressive effects of hydroxyurea in transgenic sickle cell mice, Blood. 118 (2011) 1109–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dulmovits BM, Appiah-Kubi AO, Papoin J, Hale J, He M, Al-Abed Y, Didier S, Gould M, Husain-Krautter S, Singh SA, Chan KWH, Vlachos A, Allen SL, Taylor N, Marambaud P, An X, Gallagher PG, Mohandas N, Lipton JM, Liu JM, Blanc L, Pomalidomide reverses γ-globin silencing through the transcriptional reprogramming of adult hematopoietic progenitors, Blood. 127 (2016) 1481–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Aerbajinai W, Zhu J, Gao Z, Chin K, Rodgers GP, Thalidomide induces γ-globin gene expression through increased reactive oxygen species–mediated p38 MAPK signaling and histone H4 acetylation in adult erythropoiesis, Blood. 110 (2007) 2864–2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].dos Santos JL, Lanaro C, Lima LM, Gambero S, Franco-Penteado CF, Alexandre-Moreira MS, Wade M, Yerigenahally S, Kutlar A, Meiler SE, Costa FF, Chung M, Design, synthesis, and pharmacological evaluation of novel hybrid compounds to treat sickle cell disease symptoms, J. Med. Chem 54 (2011) 5811–5819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dos Santos JL, Lanaro C, Chelucci RC, Gambero S, Bosquesi PL, Reis JS, Lima LM, Cerecetto H, González M, Costa FF, Chung MC, Design, Synthesis, and Pharmacological Evaluation of Novel Hybrid Compounds to Treat Sickle Cell Disease Symptoms. Part II: Furoxan Derivatives, J. Med. Chem 55 (2012) 7583–7592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].de Melo TRF, Kumkhaek C, Fernandes GFDS, Pires MEL, Chelucci RC, Barbieri KP, Coelho F, de O. Capote TS, Lanaro C, Carlos IZ, Marcondes S, Chegaev K, Guglielmo S, Fruttero R, Chung MC, Costa FF, Rodgers GP, Dos Santos JL, Discovery of phenylsulfonylfuroxan derivatives as gamma globin inducers by histone acetylation, Eur. J. Med. Chem 154 (2018) 341–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chelucci RC, de Oliveira IJ, Barbieri KP, Lopes-Pires ME, Polesi MC, Chiba DE, Carlos IZ, Marcondes S, Dos Santos JL, Chung M, Antiplatelet activity and TNF-α release inhibition of phthalimide derivatives useful to treat sickle cell anemia, Med. Chem. Res 28 (2019) 1264–1271. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lanaro C, Franco-Penteado CF, Silva FH, Fertrin KY, Dos Santos JL, Wade M, Yerigenahally S, de Melo TR, Chin CM, Kutlar A, Meiler SE, Costa FF, A thalidomide-hydroxyurea hybrid increases HbF production in sickle cell mice and reduces the release of proinflammatory cytokines in cultured monocytes, Exp. Hematol 58 (2018) 35–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Silva FH, Karakus S, Musicki B, Matsui H, Bivalacqua TJ, Dos Santos JL, Costa FF, Burnett AL, Beneficial Effect of the Nitric Oxide Donor Compound 3-(1,3-Dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)Benzyl Nitrate on Dysregulated Phosphodiesterase 5, NADPH Oxidase, and Nitrosative Stress in the Sickle Cell Mouse Penis: Implication for Priapism Treatment, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 359 (2016) 230–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Blanco F, Egan B, Caboni L, Elguero J, O’Brien J, McCabe T, Fayne D, Meegan MJ, Lloyd DG, Study of E/Z Isomerization in a Series of Novel Non-ligand Binding Pocket Androgen Receptor Antagonists, J. Chem. Inf. Model 52 (2012) 2387–2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].da Silva YKC, Augusto CV, de C. Barbosa ML, de A. Melo GM, de Queiroz AC, de L.M.F. Dias T, Júnior WB, Barreiro EJ, Lima LM, Alexandre-Moreira MS, Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of pyrazine N-acylhydrazone derivatives designed as novel analgesic and anti-inflammatory drug candidates, Bioorg. Med. Chem 18 (2010) 5007–5015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tsikas D, Methods of quantitative analysis of the nitric oxide metabolites nitrite and nitrate in human biological fluids, Free Radic. Res 39 (2005) 797–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tsikas D, Analysis of nitrite and nitrate in biological fluids by assays based on the Griess reaction: appraisal of the Griess reaction in the L-arginine/nitric oxide area of research, J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci 851 (2007) 51–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ford PC, Wink DA, Stanbury DM, Autoxidation kinetics of aqueous nitric oxide, FEBS Lett. 326 (1993) 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sorba G, Medana C, Fruttero R, Cena C, Di Stilo A, Galli U, Gasco A, Water soluble furoxan derivatives as NO prodrugs, J. Med. Chem 40 (1997) 463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hu J, Liu J, Xue F, Halverson G, Reid M, Guo A, Chen L, Raza A, Galili N, Jaffray J, Lane J, Chasis JA, Taylor N, Mohandas N, An X, Isolation and functional characterization of human erythroblasts at distinct stages: implications for understanding of normal and disordered erythropoiesis in vivo, Blood. 121 (2013) 3246–3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dijon M, Bardin F, Murati A, Batoz M, Chabannon C, Tonnelle C, The role of Ikaros in human erythroid differentiation, Blood. 111 (2008) 1138–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Masuda T, Wang X, Maeda M, Canver MC, Sher F, Funnell APW, Fisher C, Suciu M, Martyn GE, Norton LJ, Zhu C, Kurita R, Nakamura Y, Xu J, Higgs DR, Crossley M, Bauer DE, Orkin SH, V Kharchenko P, Maeda T, Transcription factors LRF and BCL11A independently repress expression of fetal hemoglobin, Science. 351 (2016) 285–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bradner JE, Mak R, Tanguturi SK, Mazitschek R, Haggarty SJ, Ross K, Chang CY, Bosco J, West N, Morse E, Lin K, Shen JP, Kwiatkowski NP, Gheldof N, Dekker J, DeAngelo DJ, Carr SA, Schreiber SL, Golub TR, Ebert BL, Chemical genetic strategy identifies histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and HDAC2 as therapeutic targets in sickle cell disease, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 107 (2010) 12617–12622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Shearstone JR, Golonzhka O, Chonkar A, Tamang D, van Duzer JH, Jones SS, Jarpe MB, Chemical Inhibition of Histone Deacetylases 1 and 2 Induces Fetal Hemoglobin through Activation of GATA2, PLoS One. 11 (2016) e0153767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ikuta T, Ausenda S, Cappellini MD, Mechanism for fetal globin gene expression: role of the soluble guanylate cyclase-cGMP-dependent protein kinase pathway, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 98 (2001) 1847–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].dos Santos JL, Lanaro C, Chin CM, Advances in Sickle Cell Disease Treatment: from Drug Discovery Until the Patient Monitoring, Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents Med. Chem 9 (2011) 113–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dai Y, Sangerman J, Luo HY, Fucharoen S, Chui DHK, Faller DV, Perrine SP, Therapeutic fetal-globin inducers reduce transcriptional repression in hemoglobinopathy erythroid progenitors through distinct mechanisms, Blood Cells, Mol. Dis 56 (2016) 62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Akinsheye I, Klings ES, Sickle cell anemia and vascular dysfunction: the nitric oxide connection, J. Cell Physiol 224 (2010) 620–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Perrine SP, Pace BS, V Faller D, Targeted fetal hemoglobin induction for treatment of beta hemoglobinopathies, Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am 28 (2014) 233–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].McGann PT, Ware RE, Hydroxyurea therapy for sickle cell anemia, Expert. Opin. Drug Saf 14 (2015) 1749–1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bodera P, Stankiewicz W, Immunomodulatory properties of thalidomide analogs: pomalidomide and lenalidomide, experimental and therapeutic applications, Recent Pat. Endocr. Metab. Immune Drug Discov 5 (2011) 192–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rother RP, Bell L, Hillmen P, Gladwin MT, The clinical sequelae of intravascular hemolysis and extracellular plasma hemoglobin: a novel mechanism of human disease, JAMA. 293 (2005) 1653–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].dos Santos JL, Chung M, Recent insights on the medicinal chemistry of sickle cell disease, Curr. Med. Chem 18 (2011) 2339–2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gutsaeva DR, Montero-Huerta P, Parkerson JB, Yerigenahally SD, Ikuta T, Head CA, Molecular mechanisms underlying synergistic adhesion of sickle red blood cells by hypoxia and low nitric oxide bioavailability, Blood. 123 (2014) 1917–1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Conran N, Oresco-Santos C, Acosta HC, Fattori A, Saad STO, Costa FF, Increased soluble guanylate cyclase activity in the red blood cells of sickle cell patients, Br. J. Haematol 124 (2004) 547–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ginder GD, Epigenetic regulation of fetal globin gene expression in adult erythroid cells, Transl. Res 165 (2015) 115–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pace BS, Liu L, Li B, Makala LH, Cell signaling pathways involved in drug-mediated fetal hemoglobin induction: Strategies to treat sickle cell disease, Exp. Biol. Med 240 (2015) 1050–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bosquesi PL, Melchiora ACB, Pavana AR, Lanaro C, de Souza CM, Rusinova R, Chelucci RC, Barbieri KP, dos S. Fernandes GF, Carlos IZ, Andersen OS, Costa FF, Dos Santos JL, Synthesis and evaluation of resveratrol derivatives as fetal hemoglobin inducers, Bioorg. Chem 100 (2020) 103948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].King SB, Nitric oxide production from hydroxyurea, Free Radic. Biol. Med 37 (2004) 737–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Schaeffer EK, West RJ, Conine SJ, Lowrey CH, Multiple physical stresses induce γ-globin gene expression and fetal hemoglobin production in erythroid cells, Blood Cells Mol. Dis 52 (2014) 214–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sankaran VG, Xu J, Byron R, Greisman HA, Fisher C, Weatherall DJ, Sabath DE, Groudine M, Orkin SH, Premawardhena A, Bender MA, A functional element necessary for fetal hemoglobin silencing, N. Engl. J. Med 365 (2011) 807–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].John LB, Ward AC, The Ikaros gene family: transcriptional regulators of hematopoiesis and immunity, Mol. Immunol 48 (2011) 1272–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Bottardi S, Ross J, Bourgoin V, Fotouhi-Ardakani N, Affar EB, Trudel M, Milot E, Ikaros and GATA-1 combinatorial effect is required for silencing of human gamma-globin genes, Mol. Cell Biol 29 (2009) 1526–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lopez-Girona A, Mendy D, Ito T, Miller K, Gandhi AK, Kang J, Karasawa S, Carmel G, Jackson P, Abbasian M, Mahmoudi A, Cathers B, Rychak E, Gaidarova S, Chen R, Schafer PH, Handa H, Daniel TO, Evans JF, Chopra R, Cereblon is a direct protein target for immunomodulatory and antiproliferative activities of lenalidomide and pomalidomide, Leukemia. 26 (2012) 2326–2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Mori T, Ito T, Liu S, Ando H, Sakamoto S, Yamaguchi Y, Tokunaga E, Shibata N, Handa H, Hakoshima T, Structural basis of thalidomide enantiomer binding to cereblon, Sci. Rep 8 (2018) 1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Cokic VP, Smith RD, Beleslin-Cokic BB, Njoroge JM, Miller JL, Gladwin MT, Schechter AN, Hydroxyurea induces fetal hemoglobin by the nitric oxide-dependent activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase, J. Clin. Invest 111 (2003) 231–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Haby C, Lisovoski F, Aunis D, Zwiller J, Stimulation of the cyclic GMP pathway by NO induces expression of the immediate early genes c-fos and junB in PC12 cells, J. Neurochem 62 (1994) 496–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kodeboyina S, Balamurugan P, Liu L, Pace BS, cJun modulates Ggamma-globin gene expression via an upstream cAMP response element, Blood Cells Mol. Dis 44 (2010) 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Browning DD, Windes ND, Ye RD, Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase by lipopolysaccharide in human neutrophils requires nitric oxide-dependent cGMP accumulation, J. Biol. Chem 274 (1999) 537–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ramakrishnan V, Pace BS, Regulation of γ-globin gene expression involves signaling through the p38 MAPK/CREB1 pathway, Blood Cells Mol. Dis 47 (2011) 12–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Pai K, Shrivastava A, Kumar R, Khetarpal S, Sarmah B, Gupta P, Sodhi A, Activation of P388D1 macrophage cell line by chemotherapeutic drugs, Life Sci. 60 (1997) 1239–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Tavakkoli F, Nahavandi M, Wyche MQ, Perlin E, Plasma levels of TNF-alpha in sickle cell patients receiving hydroxyurea, Hematology. 9 (2004) 61–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Telen MJ, Role of adhesion molecules and vascular endothelium in the pathogenesis of sickle cell disease, Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Progr 2007 (2007) 84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Aich A, Jones MK, Gupta K, Pain and sickle cell disease, Curr. Opin. Hematol 26 (2019) 131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hess A, Axmann R, Rech J, Finzel S, Heindl C, Kreitz S, Sergeeva M, Saake M, Garcia M, Kollias G, Straub RH, Sporns O, Doerfler A, Brune K, Schett G, Blockade of TNF-α rapidly inhibits pain responses in the central nervous system, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 108 (2011) 3731–3736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Dutra LA, de Almeida L, Passalacqua TG, Reis JS, Torres FAE, Martinez I, Peccinini RG, Chin CM, Chegaev K, Guglielmo S, Fruttero R, Graminha MAS, dos Santos JL, Leishmanicidal Activities of Novel Synthetic Furoxan and Benzofuroxan Derivatives, Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother 58 (2014) 4837–4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Dutra LA, Guanaes JFO, Johmann N, Pires MEL, Chin CM, Marcondes S, Dos Santos JL, Synthesis, antiplatelet and antithrombotic activities of resveratrol derivatives with NO-donor properties, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 27 (2017) 2450–2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Polytarchou C, Papadimitriou E, Antioxidants inhibit human endothelial cell functions through down-regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity, Eur. J. Pharmacol 510 (2005) 31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.