Abstract

Background:

The Southern dietary pattern, derived within the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort, is characterized by high consumption of added fats, fried food, organ meats, processed meats, and sugar-sweetened beverages, and is associated with increased risk of several chronic diseases. The aim of the present study was to identify characteristics of individuals with high adherence to this dietary pattern.

Design:

We analyzed data from REGARDS, a national cohort of 30,239 black and white adults ≥ 45 years of age living in the US. Dietary data were collected using the Block 98 Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ). Multivariable linear regression was used to calculate standardized beta coefficients across all covariates for the entire sample and stratified by race and region.

Results:

We included 16,781 participants with complete dietary data. Among these, 34.6% were black, 45.6% male, 55.2% resided in stroke belt region, and the average age was 65 years. Black race was the factor with the largest magnitude of association to the Southern dietary pattern (Δ = 0.76 SD, p < 0.0001). Large differences in Southern dietary pattern adherence were observed between black participants and white participants in the stroke belt and non-belt (stroke belt Δ = 0.75 SD, non-belt Δ = 0.77 SD).

Conclusion:

There was a high consumption of the Southern dietary pattern in the US black population, regardless of other factors, underlying our previous findings showing the substantial contribution of this dietary pattern to racial disparities in incident hypertension and stroke.

Introduction

The “Southern” dietary pattern is a dietary pattern derived from factor analysis within the REasons for Geographic And Racial Disparities in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort. This dietary pattern is characterized by high consumption of added fats, fried food, eggs and egg dishes, organ meats, processed meats, and sugar-sweetened beverages (1). Prior studies have shown that increased adherence to the Southern dietary pattern is associated with a higher risk of incident stroke (2), coronary heart disease (3), sepsis (4), end stage renal disease and chronic kidney disease (5), cancer mortality (6), and cognitive impairment (7). Furthermore, this dietary pattern is a large mediator of the black-white difference in stroke risk (2) and is the largest mediator of the black-white difference in the risk of incident hypertension (8). Characteristics of those most likely to adhere to the Southern dietary pattern remain unclear.

Adherence to particular dietary patterns is influenced by numerous social, economic, and environmental factors (9–16). These include sex (9), age (9, 10, 14), race (12, 14, 16), education (10, 11, 14, 15), socioeconomic stability (13, 15), and food security (13). Additionally, clinical factors, such as body mass index (BMI) (9, 17), waist circumference (17, 18), depression (17), and physical inactivity (17, 18), influence diet adherence. Evidence for these associations has involved well-studied dietary patterns including the Mediterranean diet, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, and diet-quality measures such as the Healthy Eating Index (HEI). Factors describing groups in the population with a high adherence to other dietary patterns, such as the Southern dietary pattern, have not been described.

Given that adherence to the Southern dietary pattern is associated with higher risk of many adverse health outcomes, and is a contributor to the black-white differences in several of these outcomes, identifying subgroups of the population with a high intake of the diet may provide actionable targets for intervention. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to identify population groups with a high adherence to the Southern dietary pattern.

Methods

Study Participants

REGARDS is a longitudinal cohort study designed to examine the reasons for racial and regional differences in stroke mortality. Details of the study design are provided elsewhere (19). Briefly, 30,239 black and white adults ≥ 45 years old were recruited between 2003–2007 using commercially available lists from Genesys, Inc. (Daly City, CA, USA). The study oversampled individuals who were black and residents of the Southeastern United States, an area known as the stroke belt (includes Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina), and specifically within the stroke “buckle” region along the coastal plains of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. Participants were first contacted through an introductory mailing to inform them of an upcoming phone call. REGARDS staff conducted a 45-minute phone call to recruit the participant, obtain verbal informed consent, and collect demographic, socioeconomic, and medical history data. Approximately 2–3 weeks after the phone call, an in-home visit was conducted by a trained health professional to obtain written consent and collect anthropometrics, blood and urine specimens, blood pressure measurements, an electrocardiogram, and medication history. During the in-home visit, a self-administered questionnaire was provided to collect data on dietary intake, residential history, and family history of selected diseases. This study was conducted according to guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Institutional Review Board at all participating universities. Verbal and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Dietary Assessment

The Block 98 Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) was included as part of the baseline self-administered questionnaires that were left with participants. The Block 98 FFQ was developed by Block Dietary Data Systems (Berkeley, CA, USA), distributed by NutritionQuest and validated in populations similar to REGARDS (20, 21). The questionnaire includes more than 150 multiple-choice questions based on 107 food items and can be completed in about 30–40 minutes. Participants were asked to recall usual dietary intake from the past year and mail the completed form along with the other questionnaires to the REGARDS coordinating center.

Dietary Pattern Derivation

As previously reported, usable FFQ data from the baseline FFQ were available for 21,636 paricipants (1). A total of 56 food groups were constructed based on culinary use and nutrient similarity as in similar studies (22). For example, beverages containing only some juice, such as Hi-C, were grouped with sugar-sweetened beverages based on nutritional content. Similarly, other foods, including fried potatoes, fish, and chicken, were separated into a different group because of nutritional content and likely differences in culinary use across race and geographically defined populations. Other items, such as “Chinese food,” were left in stand-alone groups due to their uniqueness. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to derive dietary patterns. An eigenvalue cutpoint of approximatley 1.5 was employed, based on scree plots and interpretability of the derived factors. A five-factor solution was selected to provide optimal congruence across region, sex, and race. Final factor loadings were derived using factor analysis with orthogonal rotation. Patterns were empirically named based on foods that loaded highly in each factor by consensus of the investigators. One of the patterns identified was the “Southern pattern,” named because of high loadings in added fats, fried food, eggs and egg dishes, organ meats, processed meats, and sugar-sweetened beverages, foods sometimes associated with a traditional diet consumed in the Southeastern US (Table 1). Other patterns comprised the “convenience pattern,” “plant-based pattern,” “sweets/fats pattern,” and “salads and alcohol pattern.” As noted above, the Southern dietary pattern subsequently was found to be associated with higher risk of an array of health outcomes and a substantial potential contributor to black-white disparities, and as such is the focus of this report.

TABLE 1.

Final factors loadings and 75th percentile of daily grams/day of food groups making up the Southern dietary pattern (showing only those with absolute value > 0.20 for simplicity).

| 75th percentile Daily Serving Size of Food Item (g/day) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Group | Factor loading | Q1 (lowest adherence) |

Q2 | Q3 | Q4 (highest adherence) |

||||

| Black | White | Black | White | Black | White | Black | White | ||

| Added fats | 0.38 | 8.2 | 12.6 | 9.6 | 15.0 | 12.7 | 19.7 | 21.8 | 30.9 |

| Bread | 0.37 | 23.8 | 31.8 | 26.8 | 38.9 | 37.1 | 55.1 | 74.0 | 89.6 |

| Cereal – high fiber | −0.25 | 16.8 | 17.4 | 8.6 | 6.7 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 4.2 |

| Eggs and egg dishes | 0.42 | 11.5 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 21.7 | 21.7 | 28.6 | 43.3 | 50.0 |

| Fried food | 0.56 | 15.6 | 8.8 | 16.7 | 13.3 | 25.5 | 19.5 | 60.0 | 36.3 |

| Fried potatoes | 0.16 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 9.3 | 5.0 | 9.3 | 10.5 | 18.6 |

| Milk – high-fat | 0.24 | 14.9 | 4.0 | 50.5 | 109.2 | 107.1 | 192.0 | 159.1 | 265.1 |

| Milk – low-fat | −0.42 | 252.1 | 346.0 | 0.0 | 74.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Organ meat | 0.47 | 2.3 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 1.8 | 7.1 | 2.9 |

| Processed meats | 0.45 | 10.6 | 13.5 | 12.1 | 17.4 | 17.9 | 23.6 | 37.5 | 41.1 |

| Red meat | 0.26 | 18.8 | 36.5 | 19.3 | 41.6 | 27.8 | 54.4 | 48.1 | 80.1 |

| Refined grains | 0.20 | 26.1 | 27.4 | 21.3 | 26.0 | 26.9 | 28.0 | 42.7 | 40.3 |

| Shell fish | 0.23 | 4.2 | 4.9 | 3.5 | 6.2 | 4.3 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 12.4 |

| Soda | 0.24 | 55.4 | 51.4 | 102.9 | 156.0 | 156.0 | 205.7 | 312.0 | 360.0 |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages | 0.37 | 8.3 | 4.1 | 16.5 | 4.1 | 38.5 | 4.1 | 145.6 | 12.4 |

| Vegetable – green-leafy | −0.22 | 103.7 | 102.6 | 63.1 | 63.1 | 41.1 | 60.1 | 39.6 | 53.5 |

| Yogurt | −0.25 | 53.1 | 35.0 | 17.5 | 9.4 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 2.0 |

Risk Factors of Interest

Risk factors were based on baseline measurements and classified as in prior REGARDS studies (2–5, 7, 19, 23). Self-reported variables were age (continuous, in years), race (black/white), sex (male/female), region of residence (stroke belt and stroke buckle vs. non-belt/buckle), income (≤ $75K/year vs. > $75K/year), current smoker (yes vs. no), and education (high school graduate or less vs. some college or more). Physical activity, also self-reported, was assessed as the number of times per week participants engaged in exercise enough to work up a sweat (none vs. some). Height, weight, waist circumference, and blood pressure were measured during the in-home visit by a trained examiner. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, (kg/m2). Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or a self-report of a prior diagnosis of hypertension or current use of anti-hypertensive medications. Diabetes was defined as a fasting blood glucose concentration of ≥126 mg/dL, or a non-fasting blood glucose concentration of ≥200 mg/dL, or a self-reported use of insulin or oral anti-glycemic agents. Geographical covariates were census tract level and determined with United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) data. These data included living in a food desert (yes vs. no), neighborhood disadvantage (yes vs. no), and residence in rural or urban areas (rural vs. urban). These data were then linked to participant residence via geocoding, methods described elsewhere (24, 25).

Statistical Analyses

The outcome of interest was a participant’s adherence to the Southern dietary pattern, as quantified by the loading score from the factor analysis. The score was a continuous scale, with a range of −4.5 to 8.2 (mean = −0.001, SD = 1.0), with higher scores indicating greater adherence to the dietary pattern. Chi-square and ANOVA tests were used to assess unadjusted means of demographic characteristics by quartile of Southern dietary pattern score. Multivariable linear regression was used to calculate standardized beta coefficients across all covariates for the entire sample, and then stratified by race and region (stroke belt/stroke buckle vs. non-belt/buckle). The standardization of the estimated regression coefficients was to allow an easy comparison of the differences in the strength of the associations across the different predictor variables. Specifically, differences in Southern diet score are expressed as the number of standard deviation difference associated with the factor; hence, between groups for dichotomous variables and per standard deviation for continuous variables (age, BMI, and waist circumference). Unadjusted and fully adjusted coefficients were calculated to compare the impact of adding additional covariates to the model. Covariates included in the final model were chosen because they have previously been shown to be associated with other dietary patterns (16, 18, 26–28). Multicollinearity was not a problem and variance inflation factor (VIF) was checked for all variables. In order to account for multiple testing, a p-value of < 0.01 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

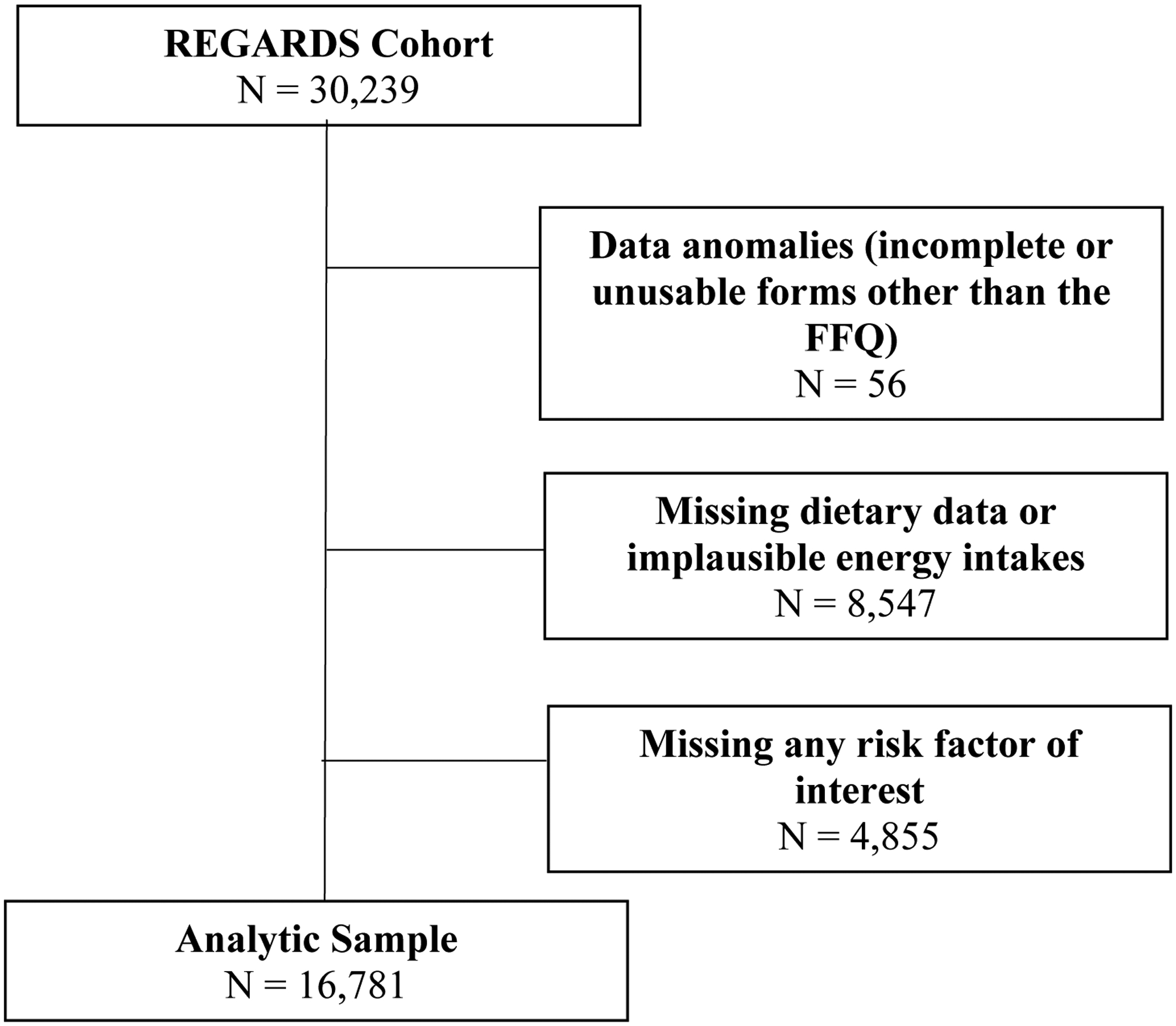

Of the 30,239 participants, 56 had data anomalies (incomplete or unusuable forms, other than the FFQ, due to being damaged), 8,547 (28%) had missing dietary data or implausible energy intakes, and 4,855 (16%) were missing risk factors of interest, leaving an analytical sample of 16,781 participants (Figure 1). Among these participants, 34.6% were black, 45.6% male, 55.2% resided in stroke belt region, and the average age was 65 years. Supplemental Table 1 provides demographic characteristics of included and excluded participants. Briefly, those excluded were more likely to be black, have a high school education or below, have an income of less than $75K/year, live in a food desert, and reside in a disadvantaged neighborhood.

Figure 1.

Participant Selection

Stratification of daily intake for food groups making up the Southern dietary pattern allowed for observation of racial differences in dietary intake (Table 1, Supplemental Table 2). Black participants in the highest quartiles of Southern pattern adherence consumed higher amounts of fried foods, organ meats, and sugar-sweetened beverages compared with white participants. Fried food intake in black participants in the fourth quartile was close to double the intake in white participants (60 g/day vs 36 g/day, respectively). Consumption of organ meats (liver, gizzard, neckbones, and chitlins) for black participants in the fourth quartile was triple the intake of white participants (7.1 g/day vs 2.9 g/day, respectively). Sugar-sweetened beverage intake among black participants in the highest quartile of Southern dietary pattern adherence was 145.6 g/day and 12.4 g/day for white participants. White participants in the highest quartile of Southern dietary pattern adherence reported higher consumption of high-fat milk and red meat. High-fat milk intake for white participants was 265 g/day (approximately 1 cup) and 160 g/day for black participants (approximately 0.68 cups). White participants in the highest quartile of adherence consumed almost double the amount of red meat compared to black participants (80 g/day vs 48 g/day, respectively).

Baseline characteristics of participants by quartile of Southern diet score are shown in Table 2. Those least adherent to the Southern dietary pattern appear in the first quartile, while those most adherent in the fourth quartile. The following characteristics were associated with greater adherence to the Southern diet pattern: black race, male sex, residence in stroke belt region, lower education level, lower income, current smoker, residence in a food desert, living in a disadvantaged neighborhood, physical inactivity, higher BMI, higher waist circumference, history of hypertension, and history of diabetes (p<.0001). Residence in a rural region was the only covariate not associated with Southern diet score (p=0.23).

TABLE 2.

Baseline characteristics by Quartile (Q) of Southern Diet Score in the REasons for Geographical and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study.

| Characteristic, mean or frequency (%) | Q1 n (%) (lowest adherence) N=5349 |

Q2 n (%) N=5349 |

Q3 n (%) N=5350 |

Q4 n (%) (highest adherence) N=5349 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range of Southern Diet Score | −4.42, −0.61 | −0.61, −0.10 | −0.10, 0.48 | 0.48, 8.25 | --- |

| Age (years), mean | 65 (9) | 65 (9) | 65 (9) | 64 (9) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 425 (7.3) | 1047 (18.0) | 1775 (30.6) | 2563 (44.1) | <0.0001 |

| Male | 1623 (21.2) | 1713 (22.4) | 1985 (25.9) | 2337 (30.5) | <0.0001 |

| Stroke belt region | 1999 (21.6) | 2246 (24.2) | 2412 (26.0) | 1585 (21.1) | <0.0001 |

| HS grad and below | 971 (17.1) | 1240 (21.8) | 1535 (27.0) | 1940 (34.1) | <0.0001 |

| Income <$75K/year | 2995 (22.2) | 3293 (24.4) | 3523 (26.1) | 3711 (27.4) | <0.0001 |

| Current smoker | 353 (15.0) | 471 (20.1) | 636 (27.1) | 887 (37.8) | <0.0001 |

| Living in food desert | 390 (15.3) | 499 (19.6) | 718 (28.2) | 940 (36.9) | <0.0001 |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | 1278 (15.5) | 1791 (21.8) | 2332 (28.3) | 2834 (34.4) | <0.0001 |

| Rural | 507 (25.3) | 532 (26.6) | 488 (24.4) | 474 (23.7) | 0.232 |

| Reporting no physical activity | 1137 (21.2) | 1351 (25.2) | 1404 (26.2) | 1472 (27.4) | <0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 27.7 (5.5) | 28.8 (5.9) | 29.4 (6.0) | 30.6 (6.7) | <0.0001 |

| Female | 87.4 (14.8) | 90.8 (15.3) | 93.5 (15.6) | 98.2 (16.4) | |

| History of hypertension | 2131 (20.3) | 2509 (23.9) | 2834 (27.0) | 3016 (28.8) | <0.0001 |

| History of diabetes | 608 (16.2) | 836 (22.3) | 1021 (27.2) | 1283 (34.2) | <0.0001 |

BMI indicates body mass index; and HS, high school.

Linear regression results are shown in Table 3. With the exception of residence in a rural region (p=0.08), all factors were significant (p<0.0001) in each unadjusted model. After fully adjusting each model for all other risk factors, residence in a rural region became significant (p=0.0009) and all other covariates, except for living in a food desert (p = 0.037), remained significant. The magnitude of the association with adherence to the Southern dietary pattern was highest for race (Δ = 0.76 SD, p <0.0001), followed by gender (Δ = 0.4 SD, p <0.0001), and smoking status (Δ = 0.3 SD, p <0.0001).

TABLE 3.

Results from linear regression models investigating factors associated with a Southern dietary pattern.

| Unadjusted | Fully adjusted for all other factors |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stratified by Race | Stratified by Region | |||||||||||

| (n=16,781) | (n=16,781) | (n=5,810) | (n=10,971) | (n=9,267) | (n=7,514) | |||||||

| Factors | Beta | P | Beta | P | Beta | P | Beta | P | Beta | P | Beta | P |

| Age (per 1 SD of 9.0 years) | −0.043 | <.0001 | −0.026 | 0.001 | −0.072 | <.0001 | 0.001 | 0.87 | −0.041 | <.0001 | −0.007 | 0.55 |

| Black participants | 0.839 | <.0001 | 0.758 | <.0001 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.754 | <.0001 | 0.765 | <.0001 |

| Males | 0.244 | <.0001 | 0.395 | <.0001 | 0.456 | <.0001 | 0.357 | <.0001 | 0.440 | <.0001 | 0.340 | <.0001 |

| Region stroke-belt vs everywhere else | 0.217 | <.0001 | 0.224 | <.0001 | 0.240 | <.0001 | 0.214 | <.0001 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Education less than HS vs greater than HS | −0.397 | <.0001 | −0.206 | <.0001 | −0.231 | <.0001 | −0.186 | <.0001 | −0.218 | <.0001 | −0.188 | <.0001 |

| Income <75K vs >75K | −0.413 | <.0001 | −0.165 | <.0001 | −0.215 | <.0001 | −0.140 | <.0001 | −0.197 | <.0001 | −0.130 | <.0001 |

| Current smoker | 0.418 | <.0001 | 0.298 | <.0001 | 0.273 | <.0001 | 0.306 | <.0001 | 0.308 | <.0001 | 0.283 | <.0001 |

| Living in a food desert | 0.382 | <.0001 | 0.039 | 0.037 | 0.025 | 0.42 | 0.053 | 0.038 | 0.038 | 0.13 | 0.040 | 0.20 |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | 0.548 | <.0001 | 0.162 | <.0001 | 0.162 | <.0001 | 0.161 | <.0001 | 0.191 | <.0001 | 0.120 | <.0001 |

| Rural | −0.041 | 0.08 | 0.069 | 0.0009 | −0.001 | 0.99 | 0.085 | <.0001 | 0.071 | 0.005 | 0.047 | 0.24 |

| Reporting no physical activity | 0.138 | <.0001 | 0.068 | <0.001 | 0.078 | 0.004 | 0.059 | 0.0003 | 0.065 | 0.0001 | 0.074 | 0.0004 |

| BMI (per SD of 6.1 kg/m2) | 0.169 | <.0001 | 0.005 | 0.011 | −0.002 | 0.66 | 0.010 | <.0001 | 0.006 | 0.02 | 0.003 | 0.27 |

| Waist circumference (per SD of 15.3 cm) | 0.174 | <.0001 | 0.005 | <.0001 | 0.007 | <.0001 | 0.004 | <.0001 | 0.005 | <.0001 | 0.006 | <.0001 |

| History of hypertension | 0.271 | <.0001 | 0.034 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.58 | 0.038 | 0.014 | 0.042 | 0.03 | 0.022 | 0.28 |

| History of diabetes | 0.312 | <.0001 | 0.025 | 0.143 | −0.040 | 0.18 | 0.077 | 0.0003 | 0.014 | 0.54 | 0.041 | 0.11 |

As the Southern diet score is a standardized factor (mean of 0.0, standard deviation of 1.0), beta coefficients can be interpreted as the number of standard deviation difference associated with the factor (i.e., between groups for dichotomous predictors and per standard deviation for continuous predictors). SD indicates standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; and HS, high school. Fully adjusted model adjusts for all other variables.

As the focus of REGARDS is on racial and geographic disparities, the data were stratified by both race and region (Table 3). For both black and white participants, male sex, residence in the stroke belt, being a current smoker, living in a disadvantaged neighborhood, reporting no physical activity, and having a greater waist circumference were all associated with greater adherence to the Southern dietary pattern. Of these, gender had the highest magnitude of association with Southern dietary pattern adherence (Δ = 0.46 SD, p <0.0001 and Δ = 0.36 SD, p <0.0001, for black participants and white participants, respectively). Having more than a high school education level and an income greater than $75K were both associated with being less adherent to the Southern dietary pattern for both black and white participants, with education level having the stronger magnitude of association (Δ = −0.23 SD, p <0.0001 and Δ = −0.19 SD, p <0.0001, for black participants and white participants, respectively). For black participants only, older age was significantly associated with being less adherent to the Southern dietary pattern. Residence in a rural region and higher BMI were only associated with greater pattern adherence in white participants. Additionally, for white participants only, history of hypertension and history of diabetes were both associated with greater adherence to the Southern dietary pattern.

In both the stroke belt region and elsewhere, black race, male sex, being a current smoker, living in a disadvantaged neighborhood, reporting no physical activity, and greater waist circumference were all associated with greater adherence to the Southern dietary pattern. Having greater than a high school education level and an income greater than $75K were associated with less adherence to the dietary pattern in both regions. Only in the stroke belt region, older age was associated with less adherence to the Southern dietary pattern and residence in a rural region, higher BMI, and history of hypertension were associated with greater pattern adherence. History of diabetes and living in a food desert were not associated with Southern diet pattern adherence in either the stroke belt or non-belt region.

Discussion

In this study, characteristics of individuals with a higher intake of the Southern dietary pattern were identified. Despite the diet being referred to as the “Southern Diet”, the single factor with the largest separation of diet adherence was race. Further, the high intake of the diet by the black population was relatively consistent in both stroke belt and non-stroke belt regions. This substantial racial difference in the diet is a major contributor to the previously reported mediation of the black-white difference in stroke risk (2) and risk of incident hypertension (8). Adherence to this dietary pattern was also higher for men, those with a lower education and income level, those who reside in a food desert and/or disadvantaged neighborhood, current smokers, those who are physically inactive, and those with higher BMI and waist circumference.

Previously, education and income have been associated with diet intake and quality, with higher-income households and those with greater education being more likely to adhere to higher-quality diets (those with greater servings of fresh fruits and vegetables and less energy from solid fats, alcoholic beverages, and added sugars) (14, 15, 27). Higher-quality diets also have higher costs, with income being a consistent predictor of diet intake (29, 30). Several of the foods comprising the Southern dietary pattern are high in energy from solid fats and added sugars, and the pattern is low in fresh fruits and vegetables. Our results are consistent with these findings, in that low education and low income were associated with greater adherence to the Southern dietary pattern.

Similarly, residence in a food desert or disadvantaged neighborhood are both environmental factors that directly affect the cost and availability of foods to an individual, thereby influencing dietary patterns followed (28, 30). Disadvantaged or lower income neighborhoods often have less access to diverse food selections and residence in these areas has been associated with decreased intake of fruits, vegetables, and fish and increased intake of less healthy meats such as processed meats (30, 31). Fresh foods can often take more time to prepare and those living in disadvantaged neighborhoods often work many jobs. This presents a complex issue of availability, affordability, and time. Consequently, this can contribute to diets low in fruits and vegetables and high in energy from processed foods and saturated fat (30), which is consistent with the foods found within the Southern dietary pattern.

We observed large differences in Southern dietary pattern adherence between black participants and white participants (stroke belt Δ = 0.75 SD, non-belt Δ = 0.77 SD). In contrast, the differences between the stroke belt and non-stroke belt were smaller regardless of race (black participants Δ = 0.24 SD, white participants Δ = 0.21 SD). As such, the differences between black participants and white participants (regardless of region) dominates the differences between regions (regardless of race). This suggests that black participants in the stroke belt are just as likely to adhere to this dietary pattern as black participants in the non-stroke belt. It also suggests that residents of the stroke belt consume more of the Southern dietary pattern regardless of race. The racial differences in daily intake of several of the foods prominent in the Southern dietary pattern reinforce this observation.

Large, but similar, differences in Southern dietary pattern adherence were observed between males and females for both race and region. The difference in adherence between males and females was larger among black participants than white participants (black participants Δ = 0.46 SD, white participants Δ = 0.36 SD). Additionally, the difference was larger for participants in the stroke belt compared to participants in the non-belt (stroke belt Δ = 0.44 SD, non-belt Δ = 0.34 SD).

One of the greatest strengths of this research is that the study was conducted in a large sample of geographically dispersed adults, with detailed measurement of covariates using standardized methods. Additionally, oversampling of black participants and residents from the southeastern United States allowed a unique opportunity to investigate sociodemographic and geographical predictors of a Southern diet pattern. However, limitations must also be considered. The study relied on FFQ data, increasing the chances for error in individual dietary reporting. Those who did not return the FFQ or had implausible data were more likely to be black, which could bias the results. Furthermore, although several covariates were adjusted for, other confounding variables from unmeasured health and lifestyle factors linked with diet cannot be excluded. Finally, as a cross-sectional study, causality cannot be inferred.

In conclusion, in this national US sample, we demonstrated that the characteristic associated with strongest adherence to the Southern dietary pattern was black race compared to white race, and this was consistent regardless of residential region and other factors. Racial differences were observed in daily intake of foods making up the Southern diet pattern, with black participants consuming greater amounts of fried foods, organ meats, and sugar-sweetened beverages compared to white participants. These findings reinforce the role of race in dietary pattern adherence and underscore the need for nutrition interventions in predominantly black communities. Future research should focus on the development and delivery of nutrition interventions and understanding of barriers to healthy eating in these communities, and the impact of these interventions on the development of chronic diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their contributions.

Sources of Support:

This study was supported by cooperative agreement U01NS041588 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. CAC was supported by award number T32HL105349 by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Data Share Statement: Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending approval from the REGARDS Executive Committee and execution of a data use agreement.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimers: none.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

Catharine A Couch, Department of Nutrition Sciences, School of Health Professions, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Marquita S Brooks, Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

James M Shikany, Department of Preventative Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Virginia J Howard, Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

George Howard, Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

D. Leann Long, Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Leslie A McClure, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Dornsife School of Public Health, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA.

Jennifer J Manly, Department of Neurology, Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and the Aging Brain, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY.

Mary Cushman, Department of Medicine, Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, Larner College of Medicine at the University of Vermont, Burlington, VT.

Neil A Zakai, Department of Medicine, Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, Larner College of Medicine at the University of Vermont, Burlington, VT.

Keith E Pearson, Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, School of Public Health, Samford University, Birmingham, AL.

Emily B Levitan, Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Suzanne E Judd, Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

References

- 1.Judd SE, Letter AJ, Shikany JM, Roth DL, Newby PK: Dietary Patterns Derived Using Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis are Stable and Generalizable Across Race, Region, and Gender Subgroups in the REGARDS Study. Front Nutr 2014, 1:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Judd SE, Gutierrez OM, Newby PK, Howard G, Howard VJ, Locher JL, Kissela BM, Shikany JM: Dietary patterns are associated with incident stroke and contribute to excess risk of stroke in black Americans. Stroke 2013, 44:3305–3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shikany JM, Safford MM, Newby PK, Durant RW, Brown TM, Judd SE: Southern Dietary Pattern is Associated With Hazard of Acute Coronary Heart Disease in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. Circulation 2015, 132:804–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gutierrez OM, Judd SE, Voeks JH, Carson AP, Safford MM, Shikany JM, Wang HE: Diet patterns and risk of sepsis in community-dwelling adults: a cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2015, 15:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutierrez OM, Muntner P, Rizk DV, McClellan WM, Warnock DG, Newby PK, Judd SE: Dietary patterns and risk of death and progression to ESRD in individuals with CKD: a cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 2014, 64:204–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akinyemiju T, Moore JX, Pisu M, Lakoski SG, Shikany J, Goodman M, Judd SE: A prospective study of dietary patterns and cancer mortality among Blacks and Whites in the REGARDS cohort. International Journal of Cancer 2016, 139:2221–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearson KE, Wadley VG, McClure LA, Shikany JM, Unverzagt FW, Judd SE: Dietary patterns are associated with cognitive function in the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort. J Nutr Sci 2016, 5:e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard G, Cushman M, Moy CS, Oparil S, Muntner P, Lackland DT, Manly JJ, Flaherty ML, Judd SE, Wadley VG, et al. : Association of Clinical and Social Factors With Excess Hypertension Risk in Black Compared With White US Adults. JAMA 2018, 320:1338–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bautista-Castano I, Molina-Cabrillana J, Montoya-Alonso JA, Serra-Majem L: Variables predictive of adherence to diet and physical activity recommendations in the treatment of obesity and overweight, in a group of Spanish subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004, 28:697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tinker LF, Rosal MC, Young AF, Perri MG, Patterson RE, Van Horn L, Assaf AR, Bowen DJ, Ockene J, Hays J, et al. : Predictors of dietary change and maintenance in the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial. J Am Diet Assoc 2007, 107:1155–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fransen HP, Boer JMA, Beulens JWJ, de Wit GA, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Hoekstra J, May AM, Peeters PHM: Associations between lifestyle factors and an unhealthy diet. European journal of public health 2017, 27:274–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen AJ, Kuczmarski MF, Evans MK, Zonderman AB, Waldstein SR: Race Differences in Diet Quality of Urban Food-Insecure Blacks and Whites Reveals Resiliency in Blacks. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2016, 3:706–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhattacharya J, Currie J, Haider S: Poverty, food insecurity, and nutritional outcomes in children and adults. J Health Econ 2004, 23:839–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCabe-Sellers BJ, Bowman S, Stuff JE, Champagne CM, Simpson PM, Bogle ML: Assessment of the diet quality of US adults in the Lower Mississippi Delta. Am J Clin Nutr 2007, 86:697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raffensperger S, Kuczmarski MF, Hotchkiss L, Cotugna N, Evans MK, Zonderman AB: Effect of race and predictors of socioeconomic status on diet quality in the HANDLS Study sample. J Natl Med Assoc 2010, 102:923–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein DE, Sherwood A, Smith PJ, Craighead L, Caccia C, Lin PH, Babyak MA, Johnson JJ, Hinderliter A, Blumenthal JA: Determinants and consequences of adherence to the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet in African-American and white adults with high blood pressure: results from the ENCORE trial. J Acad Nutr Diet 2012, 112:1763–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aggarwal B, Liao M, Allegrante JP, Mosca L: Low social support level is associated with non-adherence to diet at 1 year in the Family Intervention Trial for Heart Health (FIT Heart). J Nutr Educ Behav 2010, 42:380–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downer MK, Gea A, Stampfer M, Sanchez-Tainta A, Corella D, Salas-Salvado J, Ros E, Estruch R, Fito M, Gomez-Gracia E, et al. : Predictors of short- and long-term adherence with a Mediterranean-type diet intervention: the PREDIMED randomized trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016, 13:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, Gomez CR, Go RC, Prineas RJ, Graham A, Moy CS, Howard G: The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology 2005, 25:135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Block G, Woods M, Potosky A, Clifford C: Validation of a self-administered diet history questionnaire using multiple diet records. J Clin Epidemiol 1990, 43:1327–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caan BJ, Slattery ML, Potter J, Quesenberry CP Jr., Coates AO, Schaffer DM: Comparison of the Block and the Willett self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaires with an interviewer-administered dietary history. Am J Epidemiol 1998, 148:1137–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newby PK, Tucker KL: Empirically derived eating patterns using factor or cluster analysis: a review. Nutr Rev 2004, 62:177–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray MS, Wang HE, Martin KD, Donnelly JP, Gutiérrez OM, Shikany JM, Judd SE: Adherence to Mediterranean-style diet and risk of sepsis in the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort. The British journal of nutrition 2018, 120:1415–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dutko PVPM, Farrigan T Characteristics and influential factors of food deserts. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray MS, Lakkur S, Howard VJ, Pearson K, Shikany JM, Safford M, Gutierrez OM, Colabianchi N, Judd SE: The Association between Residence in a Food Desert Census Tract and Adherence to Dietary Patterns in the REGARDS Cohort. Food Public Health 2018, 8:79–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zazpe I, Estruch R, Toledo E, Sanchez-Tainta A, Corella D, Bullo M, Fiol M, Iglesias P, Gomez-Gracia E, Aros F, et al. : Predictors of adherence to a Mediterranean-type diet in the PREDIMED trial. Eur J Nutr 2010, 49:91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimakawa T, Sorlie P, Carpenter MA, Dennis B, Tell GS, Watson R, Williams OD: Dietary intake patterns and sociodemographic factors in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. ARIC Study Investigators. Prev Med 1994, 23:769–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A: The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents’ diets: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Public Health 2002, 92:1761–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rehm CD, Monsivais P, Drewnowski A: The quality and monetary value of diets consumed by adults in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr 2011, 94:1333–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diez-Roux AV, Nieto FJ, Caulfield L, Tyroler HA, Watson RL, Szklo M: Neighbourhood differences in diet: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999, 53:55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A, Poole C: Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. Am J Prev Med 2002, 22:23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.