Abstract

Objective:

This study aims to assess the stress levels, stress busters (stress relievers), and coping mechanisms among Saudi dental practitioners (SDPs) during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic outbreak.

Method:

A self-administered questionnaire was sent to SDPs via Google Forms. Cohen’s stress score scale was used for stress evaluation, and the mean scores were compared based on age, gender, qualification, and occupation. In addition, comparisons of the utilization of stress coping mechanisms and stress busters based on gender, age, and occupation were evaluated. Descriptive statistics were carried out using SPSS Version 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results:

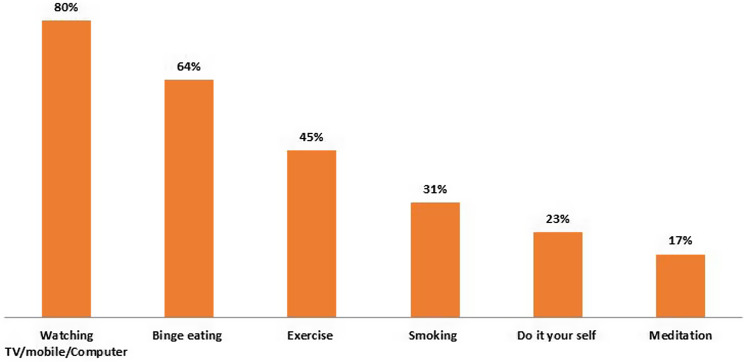

A total of 206 SDPs (69% males and 31% females) participated in the study. Male SDPs showed a higher score than females (P > 0.05). SDPs around age 50 years and above obtained high stress scores (25 ± 7.4) as compared with other age groups (P < 0.05). The occupational level showed higher stress scores (22.6 ± 4.6 than the other occupation groups (P < 0.05). The majority of the SDPs used watching TV/mobile/computer (80%) as a stress buster, followed by binge eating (64%), exercise (44%), smoking (32%), do-it-yourself (DIY; 23%), and meditation (17%).

Conclusion:

SDPs are experiencing stress levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. Male SDPs above age 50 years and private practitioners showed higher levels of stress scores. An overall commonly used stress buster was smoking in males and meditation in females.

Keywords: dental practitioners, Saudi Arabia, source of information, stress, stress busters, stress relievers

Introduction

Stress is defined as an unpleasant state of emotional and physiological stimulation that individuals experience in circumstances that they distinguish as threatening or dangerous to their welfare.1 The recent coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has posed a threat to humankind due to its potential lethality. In the present scenario, dentists are exposed to stress and are considered high-stress groups.2 Since dental professionals work in the very vicinity to patients’ oral cavity, saliva, and aerosol splatter, they are at risk of acquiring COVID-19.3,4 In the present situation of COVID-19, dental practitioners have been affected the most compared with other health care professions. In addition, anxiety, anger, confusion, insomnia, irritability, and posttraumatic symptoms have been reported to impact this pandemic outbreak.5,6 These psychological effects due to COVID-19 could lead to more harm than the contagion itself, and, at the worst, it can affect the dental practitioners for the long term and limit services to the population.

The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in 2003 had a similar impact. It affected the psychological well-being of health care workers (HCWs). It had instilled fears of financial loss, job insecurity, the uncertainty of the future, social exclusion, fear of infection, and contamination to family, friends, and colleagues.7 Lee et al.7 reported that the depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress in HCWs were more than those of the non-HCWS after a year of the SARS outbreak. The psychological effects of this outbreak on dental practitioners are complex. Stress can be beneficial and harmful. Mild to moderate levels of stress help the individual deal with the situation and also overcome it. However, if the stress is chronic and is not addressed, it can turn out to be harmful. It is human nature to find ways to deal with stress. In such an attempt, various coping mechanisms are sought by the individual. The coping mechanisms have been considered important for the stress-anxiety relationship.8 Various factors influencing the coping mechanism are ethnicity, culture, and socioeconomic characteristics.9 Of the many coping mechanisms, psychological and social assistance have been reported to improve the mental health of HCWs.10 There is a lack of evidence in the existing literature addressing the stress levels among dental professionals from Saudi Arabia and the various coping mechanisms to combat the same. Various stress busters were reported in the literature that used to reduce stress. To date, there are no studies that stated that stress leaves and stress busters among dental practitioners. Hence, the study was aimed to assess the stress levels, stress busters, and coping mechanisms among Saudi dental practitioners (SDPs) during the pandemic outbreak of COVID-19.

Methodology

A cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study was formulated to know the possible stressors, stress busters (stress relievers), and coping mechanisms adopted by the dental professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. The self-administered questionnaire (demographic-4; source of information-1; Cohen Perceived Stress Scale-10; stress coping mechanism-1; stress contributing factor-1; and stress busters-1 (Figure 1) was sent to SDPs via Google Forms. The ethical approval was obtained from the Majmaah University, Saudi Arabia. Only the completed questionnaire forms were considered for final analysis, and only responses from SDPs were used for the study’s analysis. Dentists from places other than Saudi Arabia and incomplete forms were removed from the final analysis. The obtained data were tabulated based on age, gender, qualification, and occupation. The Cohen Perceived Stress Scale11 was used for stress evaluation, and the mean scores were compared based on age, gender, qualification, and occupation. Comparisons of the utilization of stress coping mechanisms and stress busters based on gender, age, and occupation were evaluated. Descriptive statistics were carried out using SPSS Version 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Figure 1.

Pictorial representation of stress busters (stress relief activities) used in the study: A. Binge eating. B. Meditation. C. Do-it-yourself. D. Watching TV/Computer. E. Smoking. F. Exercise.

Results

Among the 410 participants, only 206 SDPs across Saudi Arabia submitted the completed questionnaire and evaluated it. Out of a total of 206 participants, 143 (69.4%) were male and 63 (30.6%) were female, with the most common age group of respondents being 31–40 years (91; 44.2%); age groups of 21-30, 41-50, and > 50 years totaled 30 (14.6%), 67 (32.5%), and 18 (8.7%), respectively (Table 1). Of the majority of the practitioners, 67 (32.5%) worked at private clinics, 53 (25.7%) worked as both faculty and private practitioners, 43 (20.9%) were faculty, and 43 (20.9%) were government practitioners (Ministry of Health [MOH]). There is a psychological stress description among the dental practitioners toward COVID-19 during the pandemic period (Table 2). The mean stress score for males is 19.62 ± 5.8, and for females, 19.14 ± 6.3 (P > 0.05); males were affected more than females from stress due to the COVID-19 pandemic. SDPs above age 50 years had high stress (25.06 ± 7.4) as compared with other age groups (21–30 years, 17.9 ± 6; 31–40 years, 18.235 ± 5.7; and 41–50 years, 20.19 ± 5) and statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) was evident among and within the age groups. At the occupation level, private practitioners showed high stress mean value of 22.67 ± 4.7 than the government employees working in MOH (16.93±4.3) and faculty who had a private practice (20.26 ± 5.4). On the other hand, academicians had a minor stress mean value of 16.05 ± 7.2, and there was a statistically significant difference among and within the groups (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic information of the participants

| Details | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 63 | 30.6% |

| Female | 143 | 69.4% |

| Age (Years) | ||

| 20-30 | 30 | 14.6% |

| 31-40 | 91 | 44.2% |

| 41-50 | 67 | 32.5% |

| > 50 | 18 | 8.7% |

| Occupation | ||

| Private practitioners | 67 | 32.5% |

| Faculty | 43 | 20.9% |

| Ministry of Health | 43 | 20.9% |

| Faculty and private practitioners | 53 | 25.7% |

Table 2.

Comparison of overall Cohen Perceived Stress Scale mean scores based on gender, age, and occupation

| Gender | Male | Female | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | 19.62 ± 5.8 | 19.14 ± 6.3 | >0.05 | ||

| Age (Years) | 20-30 | 31-40 | 41-50 | >50 | |

| Mean ± SD | 17.90 ± 6.0 | 18.35 ± 5.7 | 20.19 ± 5.0 | 25.06 ± 7.4 | <0.05 |

| Occupation | Private Practitioners | Faculty | Ministry of Health | Faculty and Private Practitioners | |

| Mean ± SD | 22.67 ± 4.7 | 16.05 ± 7.2 | 16.93 ± 4.3 | 20.26 ± 5.4 | <0.05 |

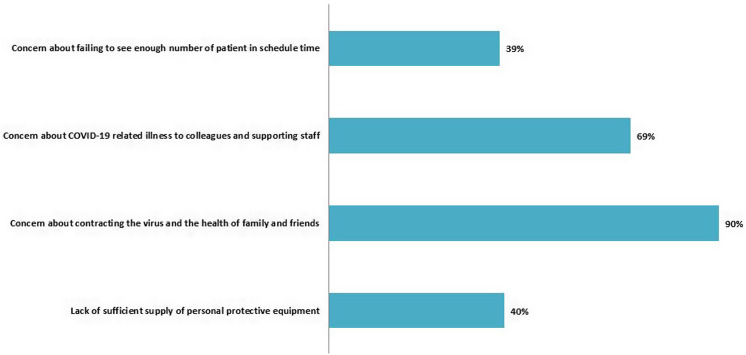

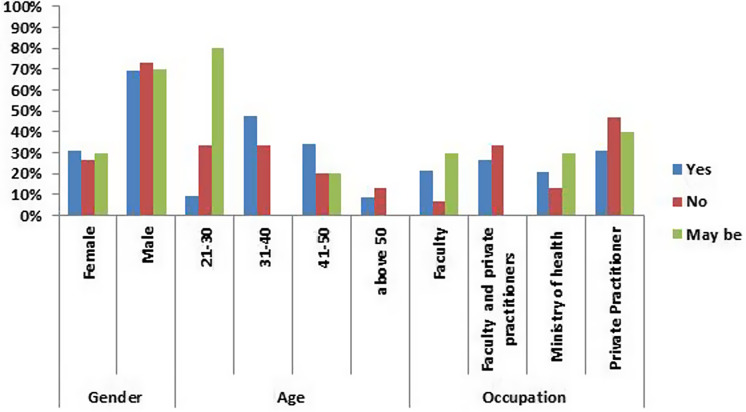

Among SDPs, 29% and 35% accessed scientific journals and websites for information regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, whereas 83% of the SDPs depended on the news, and 82% obtained the information from social media. The contributing factors for stress during post-pandemic dental practice demonstrated that most of the practitioners (90%) were worried about transmitting the virus and transmitting it to the less exposed members of family and friends; 69.4% were stressed about transmitting the virus to their colleagues and supporting staff in the dental operatory. The other stressors in ranking order were insufficient supply of personal protective equipment (40.3%) and the fear of a decline in the number of patients turning up for consultations or treatment in the dental practice (39.3%) (Figure 2). Overall, 88% of dental practitioners said they were using a stress-coping mechanism to relieve stress from the COVID-19 pandemic. Among them, 69% were males, 48% of participants were from the group of 31–40 years old, and 31% were private practitioners (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Description of contributing factors for stress during dental practice post-COVID-19 pandemic outbreak.

Figure 3.

Saudi dental practitioners’ responses to question on applying any coping mechanism for relieving stress.

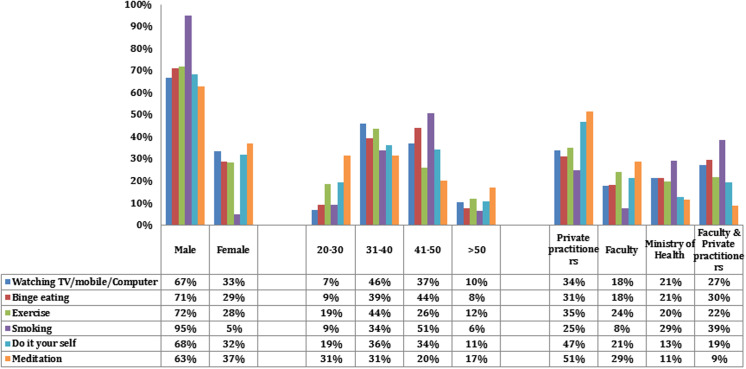

The majority of the SDPs used watching TV/mobile/computer (80%) as a stress buster, followed by binge eating (64%), exercise (44%), smoking (32%), do-it-yourself (DIY; 23%), and meditation (17%), as shown in Figure 4. Among the utilization of stress busters, males achieved higher scores than females in all stress busters (Figure 5). Among these, 96% males used smoking as a stress buster, but only 5% of females used smoking. Watching TV/mobile/computer (46%) and exercise (44%) were higher in 31-40 years of SDPs, while binge eating (44%) and smoking (51%) were high in 41- to 50-year-old SDPs (see Figure 5). SDPs in a private practice achieved high-stress buster scores for overall stress busters evaluated in the study. The SDPs working in a private practice, MOH, and faculty with a private practice used smoking as a common stress buster and rarely depend on meditation. While faculties working in academics were rarely dependent on smoking as a stress buster, and they frequently depended on meditation (see Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Details of stress busters (stress relief activities) used by Saudi dental practitioners.

Figure 5.

Details of stress busters (stress relief activities) used by Saudi dental practitioners based on gender, age, and occupation.

Discussion

This study was designed to evaluate the stress caused by COVID-19 among SDPs, the possible contributing factors, and the stress busters at the individual level based on gender, age, and occupation. A questionnaire survey was chosen for the present study as an efficient means to reach out to the large population of dental professionals throughout the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia during a pandemic to collect data, and the questionnaire was provided in Arabic and English languages. COVID-19 was affirmed a pandemic on March 11, 2020, by the World Health Organization, and Saudi Arabia imposed all the measures to control the contagion’s spread.12 Facilities like entertainment, social institutions, religious gatherings, and educational institutions were also restricted or closed in the attempt of lockdown in the second week of March 2020.13 The unprecedented situation has forced us to adopt some new norms all at once. This immediate shift from the usual routine affected the social and mental well-being of the public and mostly the HCWs.14 The nature of COVID-19 being easily transmitted adding to its fatality has instilled fears among health care professionals. They comprise a population of HCWs who work closely to the patient environment and are exposed to bodily fluids, making them vulnerable to contract this infection.3,15,16 Dentists are considered to belong to the high-stress group, and regarding the transmission nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, they also happen to be vulnerable to contracting the virus.

Another observation from the present study was that the population depended on information regarding COVID-19 on the news (83%) and social media (82%) more than trusted sources such as the official websites (35%) and scientific journals (28.6%). The strategies to handle this pandemic impact patients and the policies and have been changing almost regularly. In such a dynamic scenario,17 WHO advised restricting the information from other sources than from the official websites and from the subject experts to about once or twice a day to check the anxiety levels and beware of any misinformation more harm. A Taiwanese study reported similar results where the study population used Internet media (69%). The authors observed that COVID-19 associated information recurrently from social media, traditional media, and friends made SDPs more worried.18 The Taiwan study was conducted for 20 years, and the present study was conducted in SDPs, so the results were not comparable. Nonetheless, there is a need to evaluate media sources’ influence on health care professionals’ stress levels. In the present study, local news authorities and social media positively impacted SDPs in providing information on COVID-19.

Studies have reported that the female population’s stress levels were higher and also appeared to be more vulnerable compared with the male population among the general population and students.19 – 22 In contrast, the present study observed that the male SDPs’ stress mean scores were higher than those of the female SDPs, and the results were statistically significant. The prior Saudi study used the Event Scale – Revised and the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale: scales to evaluate the Saudi population’s stress scores.20 The American study used an anonymous, longitudinal design based on the best practice used by Amazon Turk workers.21 However, the present study evaluated stress levels based on the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale. Both studies used an online platform to send the evaluation forms to the participants, and the present study used Google Forms. The study population was SDPs, hence the results were not comparable with prior studies.

SDPs of above 50 years of age were under high stress (25.06 ± 7.4) as compared to other age groups (P < 0.05), and the findings were consistent with the study conducted. It was expected because it had been reported that people more than 60 years of age are at an utmost risk of transmitting COVID-19. The results from the present study support that even SDPs of older age also felt stress. Dentists were advised to defer any non-emergency treatment, which led to clinics/hospitals’ closure and affected most dental professionals’ income source.22 – 24 A Serbian study24 suggested that frontline health care professionals developed higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress than second-line health care teams. The authors used the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale to measure anxiety, the Perceived Stress Scale to measure stress, and the Beck Depression Inventory to measure depression. However, in the present study, the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale was used to assess the stress levels among the SDPs.

At the occupation level, private practitioners showed a higher stress mean value of 22.67 ± 4.7 than the government employees working in MOH (16.93 ± 4.3) and faculty with a private practice (20.26 ± 5.4). Academicians had the most minor stress mean value of 16.05 ± 7.2. During post-pandemic dental practice, the contributing factors for stress demonstrated that most practitioners (90%) were worried about contracting the virus and transmitting it to the less exposed family and friends. Sixty-nine percent were stressed about transmitting the virus to colleagues and supporting staff in the dental operatory. The other stressors were the insufficient supply of personal protective equipment (40.3%), followed by the fear of declining the number of patients turning up for consultations or treatment in the dental practice (39.3%). As stress is a natural response to any threat or danger, coping mechanisms are behaviors and thoughts we adopt to respond/overcome stressful situations.8,10,24 Coping changes cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and internal demands exceeding or taxing a person’s resources.25 Coping mechanisms will help and diminish stressful circumstances by identifying a possible solution, henceforth fighting stress or distracting oneself from stressful situations.26,27 The survey included a section about the coping mechanism and the participants’ stress busters during the pandemic. Overall, 88% of SDPs said they were using a stress-coping mechanism to relieve stress from the COVID-19 pandemic. Among the SDPs, 69% were males, 48% of participants were from the 31–40 years of age group, and 31% were private practitioners. The most common stress busters were electronic media (TV, media, computers) and entertainment (80.1%). Bilal et al.28 also observed that 95.5% of male participants smoked to overcome stress. The other stress busters reported were binge eating, exercise, DIY, and meditation.

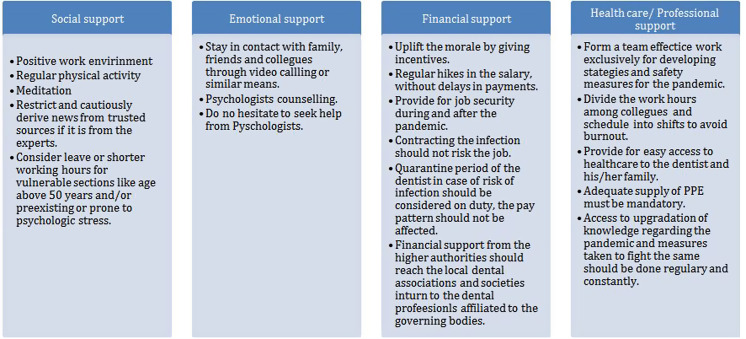

A closer examination of what is transpiring in context and the prior studies27,29,30 revealed smoking as a way of taking a study break or refocusing as well as a way of celebrating the end of an examination. The present study found that SDPs in academics and private practice used smoking as a stress buster. Almost similar findings were evident in an Ethiopian study31 where academicians showed a higher tendency to smoking as stress busters. The authors emphasized that job control, job demand, and cigarette smoking to ease occupational stress factors are more common among academicians. Taha et al.32 observed that during the H1N1 pandemic, individuals with an intolerance to uncertainty reportedly experienced more anxiety. Hence, during this period of uncertainty about the period that the pandemic will persist, if there could be an effective vaccine and the impact it will leave, anxiety is just a response to the uncertainty. The previous outbreaks of SARS in 2003 and MERS in 2012 have impacted HCWs’ psychological well-being. It also resulted in post-pandemic psychological stress.33 Although the previous pandemics have prepared society to deal with a similar situation, and COVID-19 has been challenging to expose dental professionals to a potential risk of contracting the infection and increasing psychological stress. The health care fraternity needs some thought and care to fight the stress-induced due to this pandemic. The authors developed a stress reduction model (Figure 6), adopted from the model proposed by Khosravi et al.34 This stress reduction model should be implemented to address and manage the psychological stress among HCWs during such a crisis. The model could be used in the future or built upon when faced with a challenge/outbreak/pandemic. The sample size was considerably less with a short period of study using a closed-ended questionnaire. Hence, the results were not generalized. These factors were considered to be the limitation of the present cross-sectional survey.

Figure 6.

Proposed model based on recommendations of Khosravi et al. (2020).34

Conclusion

SDPs are experiencing stress levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. Male practitioners above 50 years of age and private practitioners showed higher stress scores. Overall commonly used stress busters were electronics use – TV, mobile, and computer – and smoking was more common in males, whereas meditation was more common in females.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to all study participants for their time spent on this project.

The paper was presented at the 4th Career and Research Day organized by the International Association of Dental Research, the Saudi Arabian Division, and King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

The authors would like to thank the Dean, Scientific Research, Majmaah University for supporting this project under project No. (R-2021-161).

Author Contributions

All authors have discussed the planning and the framework of the reflection notes. All designed the theoretical framework and reviewed the literature and wrote the report.

Conflict(s) of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Gruen RJ, DeLongis A.Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;50(3):571-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meng L, Hua F, Bian Z.Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): emerging and future challenges for dental and oral medicine. J Dent Res. 2020;99(5):481-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, et al. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mallineni SK, Innes NP, Raggio DP, et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): characteristics in children and considerations for dentists providing their care. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2020;30:245-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee D.The COVID-19 outbreak: crucial role the psychiatrists can play. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;50:102014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badahdah MA, Khamis F, Mahyijari NA.The psychological well-being of physicians during COVID-19 outbreak in Oman. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289:113053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee AM, Wong JG, McAlonan GM, et al. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52(4):233-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myers HL, Myers LB.It’s difficult being a dentist: stress and health in general dentist practitioner. Br Dent J. 2004;197:89-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coster EA, Carstens IL, Harris AM.Patterns of stress among dentists. J Dent Assoc S Afr. 1987;42(7):389-394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Javed S, Parveen H.Adaptive coping strategies used by people during coronavirus. J Educ Health Promot. 2021;10:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e15-e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebrahim SH, Ahmed QA, Gozzer E, et al. COVID-19 and community mitigation strategies in a pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alshammari Thamir M, Altebainawi Ali F, Alenzi Khalidah A.Importance of early precautionary actions in avoiding the spread of COVID-19: Saudi Arabia as an example. Saudi Pharm J. 2020;28(7):898-902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United Nations. Policy brief: COVID-19 and the need for action on mental health. May 13, 2020. https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/UN-Policy-Brief-COVID-19-and-mental-health.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2021.

- 15.Bizzoca ME, Campisi G, Muzio LL.COVID-19 pandemic: what changes for dentists and oral medicine experts? A narrative review and novel approaches to infection containment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhumireddy J, Mallineni SK, Nuvvula S. Challenges and possible solutions in dental practice during and post COVID-19. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020;epub:1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.World Health Organization. WHO director-general’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19–11 March 2020. March 11, 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. Accessed June 2, 2020.

- 18.Ho HY, Chen YL, Yen CF. Different impacts of COVID-19-related information sources on public worry: an online survey through social media. Internet Interv. 2020;epub:100350. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2020.100350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Ahmed MA, Jouhar R, Ahmed N, et al. Fear and practice modifications among dentists to combat novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alkhamees A, Alrashed S, Alzunaydi A, et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the general population of Saudi Arabia. Compr Psychiatry. 2020;102:152-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park C, Russell B, Fendrich M, et al. Americans’ COVID-19 stress, coping, and adherence to CDC guidelines. J Gen Internal Med. 2020;35(8):2296-2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alyami H, Naser A, Dahmash E, et al. Depression and anxiety during 2019 coronavirus disease pandemic in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. 2020;epub. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.09.20096677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Mallineni SK, Bhumireddy JC, Nuvvula S. Dentistry for children during and post COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;epub:105734. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Antonijevic J, Binic I, Zikic O, et al. Mental health of medical personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav. 2020;epub:e01881. doi: 10.1002/brb3.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ. 2003;168:1245-1251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fallahi HR, Keyhan SO, Zandian D, et al. Being a front-line dentist during the COVID-19 pandemic: a literature review. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;42(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nichter M, Nichter M, Carkoglu A.Tobacco Etiology Research Network reconsidering stress and smoking: a qualitative study among college students. Tob Control. 2007;16(3):211-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bilal, Latif F, Bashir MF, et al. Role of electronic media in mitigating the psychological impacts of novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Psychiatry Res. 2020;289:113041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deboer LB, Tart CD, Presnell KE, et al. Physical activity as a moderator of the association between anxiety sensitivity and binge eating. Eat Behav. 2012;13(3):194-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menatti AR, DeBoer LB, Weeks JW, Heimberg RG.Social anxiety and associations with eating psychopathology: mediating effects of fears of evaluation. Body Image. 2015;14:20-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taha S, Matheson K, Cronin T, Anisman H.Intolerance of uncertainty, appraisals, coping, and anxiety: the case of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Br J Health Psychol. 2013;19(3):592-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kabito GG, Wami SD, Chercos DH, Mekonnen TH.Work-related stress and associated factors among academic staffs at the University of Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia: an institution-based cross-sectional study. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2020;30(2):223-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khalid I, Khalid T, Qabajah M, et al. Healthcare workers emotions, perceived stressors and coping strategies during a MERS-COV outbreak. Clin Med Res. 2016;14(1):7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khosravi M.Stress reduction model of COVID-19 pandemic. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2020;14(2):e103865. 10.5812/ijpbs. [DOI] [Google Scholar]