Abstract

Objectives

To assess COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Bangladesh and identify population subgroups with higher odds of vaccine hesitancy.

Design

A nationally representative cross-sectional survey was used for this study. Descriptive analyses helped to compute vaccine hesitancy proportions and compare them across groups. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to compute the adjusted OR.

Setting

Bangladesh.

Participants

A total of 1134 participants from the general population, aged 18 years and above participated in this study.

Outcome measures

Prevalence and predictors of vaccine hesitancy.

Results

Of the total participants, 32.5% showed COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Hesitancy was high among respondents who were men, over 60, unemployed, from low-income families, from central Bangladesh, including Dhaka, living in rented houses, tobacco users, politically affiliated, doubtful of the vaccine’s efficacy for Bangladeshis and those who did not have any physical illnesses in the past year. In the multiple logistic regression models, transgender respondents (adjusted OR, AOR=3.62), married individuals (AOR=1.49), tobacco users (AOR=1.33), those who had not experienced any physical illnesses in the past year (AOR=1.49), those with political affiliations with opposition parties (AOR=1.48), those who believed COVID-19 vaccines would not be effective for Bangladeshis (AOR=3.20), and those who were slightly concerned (AOR=2.87) or not concerned at all (AOR=7.45) about themselves or a family member getting infected with COVID-19 in the next year were significantly associated with vaccine hesitancy (p<0.05).

Conclusions

Given the high prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, in order to guarantee that COVID-19 vaccinations are widely distributed, the government and public health experts must be prepared to handle vaccine hesitancy and increase vaccine awareness among potential recipients. To address these issues and support COVID-19 immunisation programs, evidence-based educational and policy-level initiatives must be undertaken especially for the poor, older and chronically diseased individuals.

Keywords: COVID-19, public health, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to measure COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Bangladesh using a validated vaccine hesitancy questionnaire.

Participants were interviewed face to face to minimise non-response and maximise the quality of the data collected.

The survey assessed a range of sociodemographic and psychological variables (ie, perceived COVID-19 risk).

Including the transgender population increased the generalisability of the findings.

The influence of traditional media and social media on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was not measured, which significantly limited this study.

Introduction

The first case of COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2 was detected in December 2019 in Wuhan, China. By the first week of February 2021, COVID-19 had infected over 105 million people across 223 countries or territories and had caused more than 2.3 million fatalities worldwide.1 Consequently, COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by WHO in March 2020, and many countries began developing COVID-19 vaccines. Two COVID-19 vaccines with 90%–95% effectiveness developed by two American pharmaceutical companies were announced at the end of November 2020.2 3 Subsequently, many other safe and effective vaccines were also developed and announced by other countries.4–7 By the end of 2020, 10 vaccines were approved for either full or early use in several countries, including the USA, UK and Canada.8 Immediately after they were approved, the vaccines were rolled out in the respective countries.

However, a vaccination programme can be promoted or undermined by factors such as vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy refers to delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite the availability of the vaccination service.9 In 2019, WHO declared vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 global health threats.10 Following the COVID-19 vaccine roll-out, news regarding adverse effects of the vaccine experienced by a few vaccine recipients, along with conspiracy theories and misinformation on social media, have drawn public attention across the world.11 Hence, confusing news about the effectiveness of some vaccines by the media has negatively impacted the opinions of potential vaccine recipients.12 13 Moreover, the anxiety and hesitancy were further heightened due to the accelerated pace of vaccine development.14 Along with contemporary consequences, knowledge and awareness-related issues, vaccine hesitancy can also be determined by religious, cultural, gender or socioeconomic factors.9

A study indicated that the rate of willingness to vaccinate could range from 55% to 90% worldwide.15 However, vaccine willingness or hesitancy changes over time.9 Most of the previous studies were conducted in high-income settings and well before the vaccine was made available. However, little is known about COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in vaccination programmes being run in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) population.

Generally, vaccinations are largely accepted in LMICs, such as Bangladesh.16 A study conducted in 2018 with 140 000 individuals in 140 countries suggested that 94% of participants in South Asia described vaccination as effective, and 95% of them perceived vaccines as safe.17 However, another study conducted in Bangladesh, China, Ethiopia, Guatemala and India revealed that over 50% of respondents agreed or were neutral with regards to the notion, ‘new vaccines carry more risks than older vaccines’.18 Nonetheless, Bangladesh did not participate in any COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials. We hypothesised that, due to the novelty of COVID-19 vaccines, Bangladeshis lacked awareness of their impact. Thus, acceptance or hesitancy towards a COVID-19 vaccine among Bangladeshis might differ from other vaccines available in in the country.

The impact of COVID-19 on the overall health, economy and community of Bangladesh is one of the highest among the LMICs. By mid-February 2021, in Bangladesh, about 0.55 million COVID-19 cases had been confirmed, and about 10 000 people had died from the disease.19 While the COVID-19 vaccine roll-out in Bangladesh was inaugurated on 27 January 2021, aiming to immunise 138 million people,20 little was known about COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy or willingness among this cohort. Thus, our study aimed to (1) conduct a rapid national assessment of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Bangladesh and (2) identify population subgroups with higher odds of vaccine hesitancy.

Methods

Design and participants

In a cross-sectional study conducted in Bangladesh from 18 January 2021 to 31 January 2021, approximately 1500 male, female and transgender participants aged 18 years and above were invited to participate in an interview using a previously employed, valid and reliable vaccine hesitancy questionnaire.21 A margin of 5% error, a confidence level of 95% and a response distribution of 50% were used to calculate the sample size to target a population of 138 million individuals and secure a minimum sample size of 1067 participants.22 23 Therefore, similar to other previous studies, our sample consisted of 1134 respondents.21 24

Recruitment and training of data collectors

Eighteen health science students (nine of whom were women) were recruited to collect and sort data for this study. A 2-day online training programme was arranged for the data collectors. However, 16 successful trainees were appointed for further procedures. Among the 16 data collectors, four were assigned to North Bengal and four to South Bengal. Considering the higher population density, eight data collectors were appointed for central Bangladesh, including Dhaka City. Eight teams of two persons (one woman in each team) were created. Interviews were conducted in the Bangla language. A data collector asked the questions first, and the answers were then confirmed by the second member of the respective team.

To observe the day-to-day fluctuation of vaccine hesitancy, each team was instructed to collect around 12 pieces of data per day. Furthermore, the data collectors were briefed about the study’s objectives, methodology and questionnaire. They were taught the techniques for report building and preserving neutrality and were well informed on ethical issues, privacy concerns, cultural awareness and risk management for COVID-19 infection. A pilot study was arranged for all data collectors as a single unit following the training session to observe their capacity to comprehend relevant techniques and troublesome situations that could occur while interviewing. Necessary corrections were made following the pilot study. Each trained team visited their designated area to collect data using a semistructured questionnaire.

The questionnaire

The paper-based questionnaire comprised two parts. In the first part, participants were asked questions regarding vaccine hesitancy and perceived COVID-19 threat.21 First, participants were asked about the likelihood of getting a vaccine. The dependent variable and a key outcome of the study (ie, vaccine hesitancy) was measured using the question, ‘If a vaccine that would prevent coronavirus infection was available, how likely is it that you would get the vaccine or shot?’ The response options for this question were ‘very likely,’ ‘somewhat likely,’ ‘not likely’ and ‘definitely not.’ Second, participants were asked two questions regarding the perceived COVID-19 threat: (1) ‘How likely is it that you or a family member could get infected with coronavirus in the next one year?’ with response options ‘very likely,’ ‘somewhat likely,’ ‘not likely’ and ‘definitely not.’ (2) ‘How concerned are you that you or a family member could get infected with coronavirus in the next one year?’ with response options ‘very concerned,’ ‘concerned,’ ‘slightly concerned’ and ‘not concerned at all.’

The second part of the questionnaire comprised a wide range of sociodemographic questions. A set of structured questions assessed participants’ gender, age, religion, marital status, education, employment status, monthly household income in Bangladeshi taka, permanent address and region of residence in Bangladesh (north, south and central zone, including Dhaka), current residence type (own/rented/hostel or mess), present tobacco use status and political affiliation. Participants were also asked about the presence of children or older people at home, whether they had any physical illnesses in the last year, whether they had a chronic disease diagnosis (eg, hypertension, diabetes, asthma), and whether they practised religion regularly. These questions were answered by choosing between dichotomous options (yes/no). Additionally, participants were also asked two more COVID-19 vaccine-related questions: ‘Do you think the COVID-19 vaccine will be effective among Bangladeshis’ (no/yes/sceptical) and ‘Which developers’ vaccine would you prefer to take’ (American/British/Chinese/Russian/Indian/I have no idea regarding this).

Data collection

Individual face-to-face interviews were conducted to ensure privacy of the participants. All participants were informed of the voluntary nature of the participation. We adhered to the adequate COVID-19-related safety measures, including maintaining social distance, wearing a mask and using hand sanitisers during the interview session. The respondents were given no incentives, such as monetary retribution or food items. The questions were read out to the interviewees individually during the interview, and the acceptable options were asked. The coinvestigator reviewed the data collection sheets for completeness, accuracy and internal consistency and confirmed them with the principal investigator. The interviews were conducted at homes, marketplaces, shopping malls and waiting rooms of large hospitals and diagnostic centres. Furthermore, to include diverse participants, data were collected in the waiting room of bus and rail stations, and from a colony of the transgender population. Approximately 1500 adults were invited to the interview, and 1250 of them agreed to participate. The rate of invitees who declined the interview was higher among women and transgender people than men.

Sampling technique

We employed a two-stage cluster sampling technique to include potential participants for the study. The residential areas, marketplaces, shopping malls and waiting rooms of large hospitals, diagnostic centres, and bus and rail stations were randomly chosen and processed as a cluster in the first stage. The list of given data collection sites were collected from the districts’ websites. In the second stage, we chose the participants in a methodical and convenient manner by selecting alternate individuals from diverse groups.

Participants and public involvement

The participants and the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting and dissemination plans of our research. This study’s aim and objective were explained, and assurance of anonymity was given before receiving informed consent from the participants.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed to describe the demographic characteristics of the study participants. χ2 tests were used to compute vaccine hesitancy proportions and draw comparisons between groups. Responses were compared for various sociodemographic characteristics by dichotomising the variable as either a positive (‘very likely’ and ‘somewhat likely’) or a negative (‘not likely’ and ‘definitely not’) attitude towards the COVID-19 vaccine, indicating the extent of vaccine hesitancy. To compute adjusted ORs (AORs) with a 95% CI, multiple logistic regression analyses were performed with vaccine hesitancy as a dependent variable and sociodemographic characteristics and perceived COVID-19 threat as predictor variables for vaccine hesitancy. To ensure that the models adequately fit the data, the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used. The significance level was set at p<0.05, and SPSS V.22.0 (IBM) was used for all data analyses.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

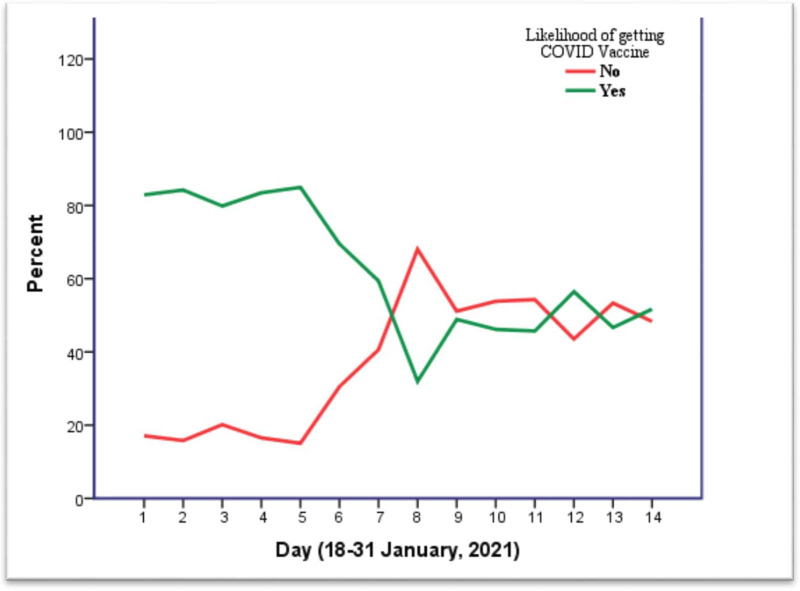

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics, perceived COVID-19 threat and vaccine hesitancy of the 1134 Bangladeshis who participated in this study. The mean age of the participants was 32.05 years (SD ±11.72). The majority of the study participants were men (59.2%), aged 26–40 years (40.7%), Muslim (93.2%), married (52.7%), with a bachelor’s degree (31.4%), full-time employees (28.7%), having a monthly household income ≥৳30 000 (44.9%), from the central zone, including Dhaka, of Bangladesh (60%), living in their own house (46.3%) and had no experience of physical illnesses (57.3%) and were not politically affiliated (56.5%). However, 29.8% of the participants were tobacco users, and only 24.3% had a chronic disease. The question on the likelihood of being infected by COVID-19 in the next year received the following responses: ‘very likely’ (34.2%), ‘somewhat likely’ (53.6%), ‘not likely’ (7.3%) and ‘definitely not’ (5.9%). Furthermore, figure 1 represents the day-to-day fluctuation of vaccine hesitancy.

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis: sociodemographic characteristics, COVID-19 threat and vaccine hesitancy

| Variables | Total sample n (%) | Likelihood of getting COVID-19 vaccine | P value | |

| Not likely/definitely not n (%) | Very likely/somewhat-likely n (%) | |||

| All participants | 1134 (100) | 369 (32.5) | 765 (67.5) | – |

| Gender | 0.003 | |||

| Transgender | 14 (1.2) | 9 (64.3) | 5 (35.7) | |

| Female | 449 (39.6) | 127 (28.3) | 322 (71.7) | |

| Male | 671 (59.2) | 233 (34.7) | 438 (65.3) | |

| Age group | 0.009 | |||

| 18–25 | 442 (39.0) | 122 (27.6) | 320 (72.4) | |

| 26–40 | 461 (40.7) | 174 (37.7) | 287 (62.3) | |

| 41–60 | 200 (17.6) | 61 (30.5) | 139 (69.5) | |

| ≥61 | 31 (2.7) | 12 (38.7) | 19 (61.3) | |

| Religion | 0.442 | |||

| Muslim | 1057 (93.2) | 349 (33.0) | 708 (67.0) | |

| Hindu | 61 (5.4) | 16 (26.2) | 45 (73.8) | |

| Cristian and Buddhist | 16 (1.4) | 4 (25.0) | 12 (75.0) | |

| Marital status | 0.039 | |||

| Unmarried | 495 (43.6) | 141 (28.5) | 353 (71.5) | |

| Married | 598 (52.7) | 214 (35.8) | 384 (64.2) | |

| Divorce/widow | 42 (3.7) | 14 (33.3) | 28 (66.7) | |

| Children at home | 0.950 | |||

| No | 481 (42.4) | 157 (32.6) | 324 (67.4) | |

| Yes | 653 (57.6) | 212 (32.5) | 441 (67.5) | |

| Aged people at home | 0.224 | |||

| No | 396 (34.9) | 138 (34.8) | 258 (65.2) | |

| Yes | 738 (65.1) | 231 (31.3) | 507 (68.7) | |

| Education | 0.268 | |||

| ≤High school | 264 (23.3) | 98 (37.1) | 166 (62.9) | |

| College education | 309 (27.2) | 92 (29.8) | 217 (70.2) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 356 (31.4) | 111 (31.2) | 245 (68.8) | |

| ≥Master’s degree | 205 (18.1) | 68 (33.2) | 137 (66.8) | |

| Employment status | 0.013 | |||

| Full-time employee | 326 (28.7) | 109 (33.4) | 217 (66.6) | |

| Part-time employee | 73 (6.4) | 23 (31.5) | 50 (68.5) | |

| Business | 169 (14.9) | 66 (39.1) | 103 (60.9) | |

| Unemployed | 88 (7.8) | 35 (39.8) | 53 (60.2) | |

| Home maker | 171 (15.1) | 60 (35.1) | 111 (64.9) | |

| Student | 307 (27.1) | 76 (24.8) | 231 (75.2) | |

| Monthly household income (৳) | 0.042 | |||

| <৳15 000 | 239 (21.1) | 78 (32.6) | 161 (67.4) | |

| ৳15 000–৳30 000 | 386 (34.0) | 108 (28.0) | 278 (72.0) | |

| ≥৳30 000 | 509 (44.9) | 183 (36.0) | 326 (64.0) | |

| Family type | 0.205 | |||

| Nuclear | 715 (63.1) | 223 (31.2) | 492 (68.8) | |

| Joint | 419 (36.9) | 146 (34.8) | 273 (65.2) | |

| Permanent address | 0.533 | |||

| Rural | 637 (56.2) | 216 (33.9) | 421 (66.1) | |

| Urban | 411 (36.2) | 126 (30.7) | 285 (69.3) | |

| Sub urban | 86 (7.6) | 27 (31.4) | 59 (68.6) | |

| Current living location | 0.048 | |||

| Central zone | 680 (60.0) | 237 (34.9) | 443 (65.1) | |

| North zone | 237 (20.9) | 62 (26.2) | 175 (73.8) | |

| South zone | 217 (19.1) | 70 (32.3) | 147 (67.7) | |

| Current residence type | 0.042 | |||

| Rented | 514 (45.3) | 184 (35.8) | 330 (64.2) | |

| Own | 525 (46.3) | 151 (28.8) | 374 (71.2) | |

| Hostel/mess | 95 (8.4) | 34 (35.8) | 61 (64.2) | |

| Regular religious practice | 0.064 | |||

| No | 328 (28.9) | 120 (36.6) | 208 (63.4) | |

| Yes | 806 (71.1) | 249 (30.9) | 557 (69.1) | |

| Present tobacco user | 0.037 | |||

| No | 796 (70.2) | 244 (30.7) | 552 (69.3) | |

| Yes | 338 (29.8) | 125 (37.0) | 213 (63.0) | |

| Did you face physical illness in the last year | 0.006 | |||

| No | 650 (57.3) | 233 (35.8) | 417 (64.2) | |

| Yes | 484 (42.7) | 136 (28.1) | 348 (71.9) | |

| Having a chronic condition | 0.943 | |||

| No | 859 (75.7) | 280 (32.6) | 579 (67.4) | |

| Yes | 275 (24.3) | 89 (32.4) | 186 (67.6) | |

| Political affiliation | 0.050 | |||

| Ruling party | 340 (30.0) | 119 (35.0) | 221 (65.0) | |

| Opposition | 153 (13.5) | 59 (38.6) | 94 (61.4) | |

| Neutral | 641 (56.5) | 191 (29.8) | 450 (70.2) | |

| Do you think the COVID-19 vaccine will be effective among Bangladeshis | <0.001 | |||

| No | 108 (9.5) | 72 (66.7) | 36 (33.3) | |

| Yes | 367 (32.4) | 43 (11.7) | 324 (88.3) | |

| Sceptical | 659 (58.1) | 254 (38.5) | 405 (61.5) | |

| Which developers’ vaccine would you prefer | 0.001 | |||

| American | 435 (38.4) | 160 (36.8) | 275 (63.2) | |

| British | 372 (32.8) | 102 (27.4) | 270 (72.6) | |

| Chinese | 82 (7.2) | 21 (25.6) | 61 (74.4) | |

| Russian | 64 (5.6) | 16 (25.0) | 48 (75.0) | |

| Indian | 39 (3.4) | 8 (20.5) | 31 (79.5) | |

| Others/no idea | 142 (12.5) | 62 (43.7) | 80 (56.3) | |

| Perceived likelihood of getting infected in the next 1 year | <0.001 | |||

| Very likely | 388 (34.2) | 141 (36.3) | 247 (63.7) | |

| Somewhat likely | 608 (53.6) | 146 (24.0) | 462 (76.0) | |

| Not likely | 83 (7.3) | 51 (61.4) | 32 (38.6) | |

| Definitely not | 55 (4.9) | 31 (56.4) | 24 (43.6) | |

| Level of concern about getting infected in the next 1 year | <0.001 | |||

| Very concerned | 226 (19.9) | 30 (13.3) | 196 (86.7) | |

| Concerned | 290 (25.6) | 53 (18.3) | 237 (81.7) | |

| Slightly concerned | 235 (20.7) | 69 (29.4) | 166 (70.6) | |

| Not concerned at all | 383 (33.8) | 217 (56.7) | 166 (43.3) | |

Bold faces are significant at 5% significance level.

Figure 1.

Day-to-day fluctuation of COVID-19 vaccine wiliness or hesitancy among participants.

Descriptive analysis

Statistically significant differences in vaccine hesitancy were found based on sociodemographic characteristics, with the highest prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the transgender population (64%; p=0.003), persons aged over 60 (39%; p=0.009), unemployed persons (40%; p=0.013), those with a monthly household income <৳15 000 (33%; p=0.042), those living in the central zone (35%; p=0.048), those living in a rented house (36%; p=0.042), tobacco users (37%; p=0.037), those who had not faced a physical illness in the past year (36%; p=0.006) and those affiliated with the opposition parties (39%; p=0.050), those who did not believe in COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness for Bangladeshi (67%; p=<0.001), and those who had no knowledge on vaccine developers (43.7%; p=0.001) (table 1).

Furthermore, participants who were not likely to believe that they or a family member could be infected with COVID-19 in the next year (61%; p≤0.001) and those who were not concerned at all about themselves or a family member getting infected in the next year (57%; p≤0.001) had the highest rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.

Multiple logistic regression analysis

Table 2 presents the predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. A multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy by including factors significantly associated with vaccine hesitancy in the descriptive analysis. In this multiple regression model, groups with significantly higher odds of vaccine hesitancy were found to be transgender individuals (AOR=3.62, 95% CI=1.177 to 11.251), married persons (AOR=1.49, 95% CI=1.047 to 2.106), tobacco users (AOR=1.33, 95% CI=1.018 to 1.745), participants who had not experienced physical illnesses in the past year (AOR=1.49, 95% CI=1.134 to 1.949), those with political affiliations with opposition parties (AOR=1.48, 95% CI=1.025 to 2.134), those who doubted the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines for Bangladeshis (AOR=3.20, 95% CI=2.079 to 4.925) and those who were slightly concerned (AOR=2.87, 95% CI=1.744 to 4.721) or not concerned at all (AOR=7.45, 95% CI=4.768 to 11.643) about themselves or a family member getting infected with COVID-19 in the next year. Compared with participants who believed it was very likely that they or their family members could get infected with COVID-19 in the next 1 year, those who thought such an occurrence would not be likely (AOR=1.88, 95% CI=1.109 to 3.172) had significantly higher odds of vaccine hesitancy. Nonetheless, women (AOR=0.70, 95% CI=0.537 to 0.928), students (AOR=0.60, 95% CI=0.379 to 0.966) and those who preferred to take the British (AOR=0.48, 95% CI=0.324 to 0.725), Chinese (AOR=0.44, 95% CI=0.245 to 0.807), Russian (AOR=0.42, 95% CI=0.222 to 0.825) or Indian (AOR=0.33, 95% CI 0.143 to 0.774) vaccine had statistically significantly lower odds of vaccine hesitancy.

Table 2.

Multiple logistic regression: predictors of vaccine hesitancy in study participants

| Variables | Adjusted OR | SE | 95% CI | P value |

| Gender | ||||

| Transgender | 3.639 | 0.576 | 1.177 to 11.251 | 0.025 |

| Female | 0.706 | 0.139 | 0.537 to 0.928 | 0.013 |

| Male | Reference | |||

| Age group | ||||

| 18–25 | Reference | |||

| 26–40 | 1.208 | 0.179 | 0.851 to 1.715 | 0.290 |

| 41–60 | 0.808 | 0.238 | 0.508 to 1.285 | 0.368 |

| ≥61 | 1.053 | 0.434 | 0.450 to 2.465 | 0.905 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Unmarried | Reference | |||

| Married | 1.485 | 0.175 | 1.047 to 2.106 | 0.027 |

| Divorce/widow | 1.606 | 0.394 | 0.742 to 3.44 | 0.229 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Full-time employee | 1.006 | 0.217 | 0.657 to 1.539 | 0.979 |

| Part-time employee | 0.914 | 0.315 | 0.439 to 1.693 | 0.775 |

| Business | 1.230 | 0.227 | 0.788 to 1.921 | 0.362 |

| Unemployed | 1.311 | 0.284 | 0.751 to 2.286 | 0.341 |

| Student | 0.606 | 0.238 | 0.379 to 0.966 | 0.035 |

| Home maker | Reference | |||

| Monthly household income (৳) | ||||

| <৳15 000 | Reference | |||

| ৳15 000–৳30 000 | 0.790 | 0.185 | 0.550 to 1.136 | 0.203 |

| ≥৳30 000 | 1.181 | 0.185 | 0.822 to 1.696 | 0.368 |

| Current living location | ||||

| Central zone | 1.105 | 0.169 | 0.793 to 1.540 | 0.554 |

| North zone | 0.762 | 0.209 | 0.506 to 1.147 | 0.192 |

| South zone | Reference | |||

| Current residence type | ||||

| Rented | 0.962 | 0.235 | 0.607 to 1.527 | 0.871 |

| Own | 0.761 | 0.241 | 0.475 to 1.221 | 0.258 |

| Hostel/mess | Reference | |||

| Tobacco user | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.333 | 0.138 | 1.018 to 1.745 | 0.037 |

| Did you face physical illness in the last year | ||||

| No | 1.486 | 0.138 | 1.134 to 1.949 | 0.004 |

| Yes | Reference | |||

| Political affiliation | ||||

| Ruling party | 1.269 | 0.143 | 0.959 to 1.678 | 0.096 |

| Opposition | 1.479 | 0.187 | 1.025 to 2.134 | 0.037 |

| Neutral | Reference | |||

| Do you think the COVID-19 vaccine will be effective among Bangladeshis | ||||

| No | 3.199 | 0.220 | 2.079 to 4.925 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 0.212 | 0.182 | 0.149 to 0.303 | <0.001 |

| Sceptical | Reference | |||

| Which developers’ vaccine would you prefer | ||||

| American | 0.744 | 0.197 | 0.506 to 1.094 | 0.133 |

| British | 0.484 | 0.205 | 0.324 to 0.725 | <0.001 |

| Chinese | 0.444 | 0.304 | 0.245 to 0.807 | 0.008 |

| Russian | 0.428 | 0.335 | 0.222 to 0.825 | 0.011 |

| Indian | 0.332 | 0.431 | 0.143 to 0.774 | 0.011 |

| No idea | Reference | |||

| Perceived likelihood of getting infected in the next 1 year | ||||

| Very likely | Reference | |||

| Somewhat likely | 0.645 | 0.161 | 0.471 to 0.884 | 0.006 |

| Not likely | 1.875 | 0.268 | 1.109 to 3.172 | 0.019 |

| Definitely not | 1.099 | 0.307 | 0.602 to 2.007 | 0.758 |

| Level of concern about getting infected in the next 1 year | ||||

| Very concerned | Reference | |||

| Concerned | 1.609 | 0.255 | 0.977 to 2.649 | 0.062 |

| Slightly concerned | 2.869 | 0.254 | 1.744 to 4.721 | <0.001 |

| Not concerned at all | 7.450 | 0.228 | 4.768 to 11.643 | <0.001 |

Bold faces are significant at 5% significance level.

Discussion

In the current comprehensive national study, more than one-third of the participants (32.5%) reported vaccine hesitancy. Analysis of daily data suggested that vaccine hesitancy varied from 18% to 72% in Bangladesh. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to measure COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Bangladesh using the previously used COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy questionnaire; thus, little is known about the previous hesitancy rate. However, a global survey from June 2020 suggested that more than 80% of participants from China, Korea, and Singapore were very or somewhat likely to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.15 Another study conducted in September 2020 in Japan found that 65% of participants were willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.24 However, a January 2021 survey in India suggested that 60% of polled Indians showed hesitancy towards receiving COVID-19 vaccines.25

In the current study, we found a higher vaccine hesitancy among male, older, married and transgender participants. In the final model, women showed significantly lower odds of vaccine hesitancy. In agreement with our findings, a global study observed lower odds of vaccine willingness among male participants15; however, women in Japan demonstrated very high vaccine hesitancy compared with men.24 American women also showed lower willingness towards the COVID-19 vaccine.26 Nonetheless, an early study suggested that Bangladeshi women’s better knowledge, attitude and preventive practice towards COVID-19 could be the reasons for a lower rate of vaccine hesitancy among them.27 Furthermore, we found statistically significant higher odds of vaccine hesitancy among the transgender population. Previous research suggested that vaccine hesitancy is universally higher among gender minorities due to limited access and interaction with healthcare professionals, historical, biomedical and healthcare-related mistrust, cost-related concerns, lack of belief in the scientific enterprise of medicine and public health, lack of awareness and education.28 An additional regional study is required to determine the gender-based difference in vaccine hesitancy.

Unlike other studies, we found higher vaccine hesitancy among older people than younger individuals. This difference could also be explained by an earlier study that showed a lack of COVID-19-related knowledge among the older population of Bangladesh.27 Sociocultural and religious beliefs related to preexisting vaccine hesitancy among the older population could also cause higher vaccine hesitancy among the Bangladeshis. Additionally, results regarding the married population are incorporated with age; therefore, results need to be interpreted by considering marital status and age together.

Unemployment, an education level lower than or equal to high school, and a monthly household income of less than ৳15 000 were associated with a higher likelihood of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Bangladesh. In line with our findings, a global study also suggested that participants with lower education and income were less likely to get the COVID-19 vaccine.15 Moreover, participants who were unemployed and those with a low level of education in the USA and Saudi Arabia showed higher vaccine hesitancy.26 29 Contrastingly, other studies found that unemployed participants were more likely to accept the COVID-19 vaccine as in some regions, unemployed individuals may want to return to work, which could only be facilitated after vaccination.21 30

A unique finding of this study was that a high portion of tobacco users showed hesitancy to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. This high rate may be explained with the reason that, universally, tobacco users (including smokers) tend to have unhealthy life practices. Nonetheless, a systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that current and previous smoking habit is associated with severe COVID-19 outcomes.31 Another systematic review suggested that tobacco use was significantly associated with a higher rate of mortality among patients with COVID-19.32 So far, there have been discussions on vaccine prioritisation (eg, for front liners). However, little vaccination planning has been done for the most vulnerable populations who continue to remain susceptible to COVID-19 outcomes (ie, a greater number of deaths and severe infections). Our findings would help identify these subgroups. In contrast, we found high odds among those who did not have physical illnesses throughout the last year. However, existing evidence suggests that healthier individuals can also be infected by COVID-19 and that the outcomes are unpredictable. Therefore, policy-makers should target these subgroups when planning vaccine literacy for potential vaccine recipients.

Interestingly, we found statistically significant higher vaccine hesitancy among politically affiliated (either affiliated with the ruling parties or oppositions) participants than those who described themselves as neutral. However, regression analysis suggested that those affiliated with opposition parties had higher odds. Additionally, a systematic review and meta-analysis found that vaccine hesitancy in LMICs collated with a range of trust-based relationships, such as trust in healthcare professionals, the health system, the government, and friends and family members.33

The effectiveness of vaccines in general varies between races and countries.34 However, no human clinical trial of any COVID-19 vaccine has been conducted in Bangladesh. In our study, participants were asked whether they believed in the efficacy of the vaccines for Bangladeshis. Those who answered ‘no’ and remained ‘sceptical’ showed a higher rate of vaccine hesitancy. However, this finding is similar to the findings of a study conducted in another country.35 Finally, our study revealed high odds of hesitancy among those who were not concerned about being infected by COVID-19. In support of our findings, a systematic review confirmed that people’s perceived risk of infection is one of the strongest predictors of pandemic vaccine acceptance or hesitancy.36

In our study, participants were asked about their vaccine choice. Evidence suggested that the efficacy of different vaccines from various developers was not matched.37 For example, vaccines from the American companies, Moderna and Pfizer, and Russian company Gamaleya have the highest efficacy (ie, >90%). A British vaccine, Oxford-AstraZeneca, has moderate efficacy (76%). A vaccine from the Chinese company Sinovac has shown lower efficacy (51%). Furthermore, a study has shown that some vaccines (eg, Oxford-AstraZeneca) produce severe adverse effects, such as very rare blood clots and even fatalities.38 Consequently, some countries, such as Denmark, have stopped using the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. Our study found statistically significant differences in vaccine hesitancy between the vaccine preference subgroups. This finding highlights the need to further study whether freedom in vaccine choice among the population could reduce vaccine hesitancy in Bangladesh.

Risk perception is central to many health behaviour theories. A systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that vaccination behaviour is significantly predicted by likelihood of risk, susceptibility and severity of the disease.39 In the case of COVID-19, a study suggested that higher risk perception was associated with reduced vaccine hesitancy.40 Furthermore, another study revealed that reduced risk perception was associated with reduced COVID-19 vaccine willingness.41 Contrastingly, a particular study suggested that the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine outweighs disease risk perception when predicting vaccine hesitancy.42 In our study, we found that perceived COVID-19 threat was strongly associated with vaccine hesitancy. However, our study found significantly high fluctuation rate in day-to-day vaccine hesitancy among Bangladeshi general population. Negative news on social and traditional media regarding adverse effects of vaccination during vaccine roll out in Bangladesh or neighbouring countries like India and changes in the local pandemic situation might be the potential causes of this fluctuation. Further study is required to find the details to implicate the results.

Several limitations may have influenced our results. First, this study is a cross-sectional study that portrays the community response at the climacteric of the study. Nonetheless, studies have found that vaccine hesitancy is complex in disposition and is adherence-specific, varying over time, location and perceived behavioural nature of the community.36 43 44 Second, the influence of social and traditional media influence is major predictor of pandemic vaccine hesitancy or acceptance.45 In our study, we did not examine the impact of the media, thus potentially confounding the results. Additional research is warranted to address this issue. Third, as the refusal rate to participate in this study was higher among women, we had slightly higher number of male participants in the study sample. Finally, the face-to-face interview format may have led to social desirability bias, so more anonymous methods should be employed in further studies. Additionally, participants were asked about their willingness to get a vaccine that prevents infection, however, for many vaccines, the shot actually lessened the severity of the disease. This might have slightly influenced the study results. Despite these limitations, our study provided baseline evidence regarding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among LMICs. Furthermore, our study identified many subgroups of the general population that must be considered during vaccine hesitancy discussions. Finally, data collected by interviewing systematically selected participants from the north, south and central zone of Bangladesh, including Dhaka, would have given a better representation of the population in the sample, thus increasing the generalisability of the study.

Conclusion

The current study found differences in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy based on the sociodemographic characteristics, health and behaviour of the Bangladeshi general population. Various contributing factors for vaccine hesitancy, such as preexisting indecisiveness, cultural and religious views, lack of belief in the scientific enterprise of medicine and public health, especially among the older population and lower levels of awareness, were identified. Further research is warranted to comprehend the complicated interplay of various individual and social characteristics influencing vaccine hesitancy. To ensure the extensive coverage of COVID-19 vaccines, the government, public health officials and advocates must be prepared to address vaccine hesitancy to reach their target and build vaccine literacy among potential recipients. Evidence-based educational and policy-level interventions must be implemented to address these problems and promote COVID-19 immunisation programmes. The rates of willingness are subject to change with the suitability of vaccines, but the frequent and ambivalent effects of vaccines may further reduce those rates. The uptake of COVID-19 vaccines can be increased once the factors identified in this study are properly addressed, and the long-term positive effects of the vaccines are clarified to the general population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Both authors are thankful to the participants for providing the information used to conduct the study.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Dr_Mohammad_Ali

Contributors: MA participated in study conception, design and coordination of the manuscript. MA also performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. AH reviewed the manuscript and helped to draft the manuscript. Both the authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Formal ethical approval was received from the Ethical Review Committee (ERC) of Uttara Adhunik Medical College and Hospital. Prospective observational trial registration was obtained from the WHO endorsed Clinical Trial Registry-India: CTRI/2021/01/030546. Furthermore, we conducted the study strictly following the STROBE guideline. All the invited participants were required to provide informed consent for participation, collection and analysis of their data.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Weekly operational update on COVID-19, 2021: 1–10. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-update-on-covid-19-16-october-2020 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2603–15. 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2021;384:403–16. 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logunov DY, Dolzhikova IV, Shcheblyakov DV, et al. Safety and efficacy of an Rad26 and RAD5 vector-based heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccine: an interim analysis of a randomised controlled phase 3 trial in Russia. Lancet 2021;397:671–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00234-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voysey M, Clemens SAC, Madhi SA, et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet 2021;397:99–111. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Zeng G, Pan H, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18-59 years: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2021;21:181–92. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30843-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caddy S. Russian SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. BMJ 2020;370:m3270. 10.1136/bmj.m3270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.How Eight Covid-19 Vaccines Work - The New York Times. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/health/how-covid-19-vaccines-work.html?name=styln-coronavirus-vaccines®ion=TOP_BANNER&block=storyline_menu_recirc&action=click&pgtype=Interactive&impression_id=512adde2-6258-11eb-9e5c-17bd043bd909&variant=1_Show [Accessed 29 Jan 2021].

- 9.MacDonald NE, SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy . Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015;33:4161–4. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aranda S. Ten threats to global health in 2019. World Health Organisation (WHO), 2019: 1–18. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beckett L. Misinformation “superspreaders”: Covid vaccine falsehoods still thriving on Facebook and Instagram. The Guardian, 2021. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/06/facebook-instagram-urged-fight-deluge-anti-covid-vaccine-falsehoods [Accessed 31 Jan 2021].

- 12.Covid: France restricts AstraZeneca vaccine to under-65s - BBC News, 2021. Available: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-55901957 [Accessed 2 Feb 2021].

- 13.UK defends Oxford vaccine as Germany advises against use on over-65s | World news | The Guardian [Internet]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/28/germany-recommends-oxford-astrazeneca-covid-vaccine-not-used-over-65s [Accessed 31 Jan 2021].

- 14.Fadda M, Albanese E, Suggs LS. When a COVID-19 vaccine is ready, will we all be ready for it? Int J Public Health 2020;65:711–2. 10.1007/s00038-020-01404-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med 2021;27:225–8. 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhopal S, Nielsen M. Vaccine hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries: potential implications for the COVID-19 response. Arch Dis Child 2021;106:113–4. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-318988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welcome Foundation . Wellcome global monitor 2018 | reports | Wellcome, 2019. Available: https://wellcome.org/reports/wellcome-global-monitor/2018 [Accessed 31 Jan 2021].

- 18.Wagner AL, Masters NB, Domek GJ, et al. Comparisons of vaccine hesitancy across five low- and middle-income countries. Vaccines 2019;7:155. 10.3390/vaccines7040155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization . Who coronavirus disease (COVID-19) report, 2021. Available: https://covid19.who.int/ [Accessed 29 Jan 2021].

- 20.Covid-19 vaccination across Bangladesh to start from Feb 7 | Dhaka Tribune. Available: https://www.dhakatribune.com/health/coronavirus/2021/01/26/health-minister-vaccination-to-start-from-feb-7 [Accessed 31 Jan 2021].

- 21.Khubchandani J, Sharma S, Price JH, et al. COVID-19 vaccination Hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. J Community Health 2021;46:270–7. 10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taherdoost H. Determining sample size; how to calculate survey sample size. Int J Econ Manag Syst 2017;2:237–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.James E, Joe W, Chadwick C. Organizational research : Determining appropriate sample size in survey research. Inf Technol Learn Perform J 2001;19:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoda T, Katsuyama H. Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination in Japan. Vaccines 2021;9:48. 10.3390/vaccines9010048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coronavirus update February, 2021 - The Hindu, 2021. Available: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/coronavirus-live-updates-february-4-2021/article33745821.ece [Accessed 7 Feb 2021].

- 26.Malik AA, McFadden SM, Elharake J, et al. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine 2020;26:100495. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali M, Uddin Z, Banik PC. Knowledge, attitude, practice and fear of COVID-19: a cross-cultural study. medRxiv 2020;26. 10.1101/2020.05.26.20113233v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Owen-Smith AA, Woodyatt C, Sineath RC, et al. Perceptions of barriers to and facilitators of participation in health research among transgender people. Transgend Health 2016;1:187–96. 10.1089/trgh.2016.0023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Mohaithef M, Padhi BK. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia: a web-based national survey. J Multidiscip Healthc 2020;13:1657–63. 10.2147/JMDH.S276771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Taiber S, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol 2020;35:775–9. 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gülsen A, Yigitbas BA, Uslu B, et al. The effect of smoking on COVID-19 symptom severity: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pulm Med 2020;2020:1–11. 10.1155/2020/7590207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salah HM, Sharma T, Mehta J. Smoking doubles the mortality risk in COVID-19: a meta-analysis of recent reports and potential mechanisms. Cureus 2020;12:e10837. 10.7759/cureus.10837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larson HJ, Clarke RM, Jarrett C, et al. Measuring trust in vaccination: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2018;14:1599–609. 10.1080/21645515.2018.1459252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hernandez D. Pfizer Covid-19 Vaccine Works Against Mutations Found in U.K, South Africa Variants, Lab Study Finds - WSJ, 2021. Available: https://www.wsj.com/articles/pfizer-covid-19-vaccine-works-against-mutations-found-in-u-k-south-africa-variants-lab-study-finds-11611802559 [Accessed 5 Feb 2021].

- 35.Attwell K, Lake J, Sneddon J, et al. Converting the maybes: crucial for a successful COVID-19 vaccination strategy. PLoS One 2021;16:e0245907. 10.1371/journal.pone.0245907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen T, Henningsen KH, Brehaut JC, et al. Acceptance of a pandemic influenza vaccine: a systematic review of surveys of the general public. Infect Drug Resist 2011;4:197. 10.2147/IDR.S23174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Covid-19 Vaccine Tracker: Latest Updates - The New York Times. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/science/coronavirus-vaccine-tracker.html [Accessed 18 Jun 2021].

- 38.Tobaiqy M, Elkout H, MacLure K. Analysis of thrombotic adverse reactions of covid-19 astrazeneca vaccine reported to eudravigilance database. Vaccines 2021;9:393. 10.3390/vaccines9040393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Gibbons FX, et al. Meta-Analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: the example of vaccination. Health Psychol 2007;26:136–45. 10.1037/0278-6133.26.2.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caserotti M, Girardi P, Rubaltelli E, et al. Associations of COVID-19 risk perception with vaccine hesitancy over time for Italian residents. Soc Sci Med 2021;272:113688. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kucukkarapinar M, Karadag F, Budakoglu I, et al. COVID-19 vaccine Hesitancy and its relationship with illness risk perceptions, affect, worry, and public trust: an online serial cross-sectional survey from turkey. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology 2021;31:98–109. 10.5152/pcp.2021.21017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karlsson LC, Soveri A, Lewandowsky S, et al. Fearing the disease or the vaccine: the case of COVID-19. Pers Individ Dif 2021;172:110590. 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao X, Wong RM. Vaccine hesitancy and perceived behavioral control: a meta-analysis. Vaccine 2020;38:5131–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.04.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, et al. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007-2012. Vaccine 2014;32:2150–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Puri N, Coomes EA, Haghbayan H, et al. Social media and vaccine hesitancy: new updates for the era of COVID-19 and globalized infectious diseases. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2020;16:2586–93. 10.1080/21645515.2020.1780846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.