Abstract

This cross-sectional study examines trends in acquisition and funding of surgical practices and facilities by private equity firms in the US from January 1, 2000, to October 30, 2020.

Health care has become a profitable field, drawing the attention of private equity (PE) firms with the goal of increasing return on investment. Studies have shown an increasing number of acquisitions of specialty practices, such as dermatology and ophthalmology practices, by PE firms.1,2 Private equity firms generally seek to consolidate practices, improve efficiencies in care, and increase market share. Surgical services are one of the most profitable aspects of health care; elective procedures account for billions of dollars of annual health care revenue. Currently, surgical services account for 51% of all Medicare spending, with an increasing market share from outpatient surgical costs.3 Although surgical services and facilities, including ambulatory surgery centers, have demonstrated the ability to profit, little is known regarding the scope of acquisitions of surgical care practices and facilities by PE firms. Understanding the temporal trends and geographic regions of surgical services acquired and funded by PE firms may help surgeons, payers, and patients appreciate the evolving financial situation of surgical care.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study examining the acquisition and funding of surgical practices and facilities by PE firms in the US from January 1, 2000, to October 30, 2020. We used 3 financial databases that contain public and private business transaction data: Zephyr, S&P Global, and Privco. We used the following search terms to collect data for all surgical specialties: surg, orthop, uro, plastic, cosmetic, vascular, thoracic, oto, neuro, gyn, oral, maxillo, ophthal, and oncol. We collected data regarding types of investments (acquisition vs funding), industry acquired (health care facility vs services), location of the target company (divided into 4 census regions: West, Midwest, South, Northeast), and amount of funding. This study qualified for nonregulated status from the institutional review board at the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor. We used generalized linear regression models to examine temporal trends in funding and acquisition by PE firms. Statistical significance was set at 2-sided P < .05. Data analysis was performed using Stata, version 15.0 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

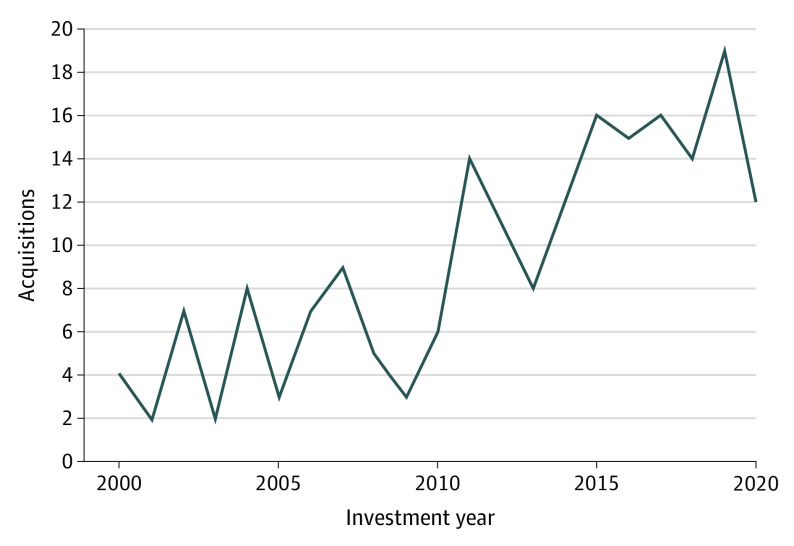

A total of 193 investments were made by 101 PE firms to acquire or fund surgical practices and facilities. Of these investments, 100 (52%) involved operative facilities including ambulatory surgery centers and 93 (48%) involved surgical services including physician practices. Most investments (117 [61%]) led to acquisition of the surgical practice or facility. The number of investments to acquire and fund practices by PE firms increased each year, from 4 in 2000 to 19 in 2019 (β, 0.65; 95% CI 0.42-0.88, P < .001) (Figure). The mean (SD) price of acquisitions was $143 ($356) million. Overall, most practices and facilities acquired and funded by PE firms (88 [46%]) were in the South; however, after 2016, the number of practices and facilities acquired and funded by PE firms was similar among the census regions (Table).

Figure. Investments in Surgical Practices by Private Equity Firms Over Time.

Table. Investments Made by Private Equity Investors to Fund or Acquire Surgical Practices by Census Region.

| Period, census region | Investments, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| 2000-2005 (n = 26) | |

| South | 17 (65) |

| West | 7 (27) |

| Midwest | 2 (8) |

| 2006-2010 (n = 30) | |

| South | 15 (50) |

| West | 7 (23) |

| Midwest | 6 (20) |

| Northeast | 2 (7) |

| 2011-2015 (n = 61) | |

| South | 28 (46) |

| West | 16 (26) |

| Midwest | 7 (12) |

| Northeast | 10 (16) |

| 2016-2020 (n = 76)a | |

| South | 28 (37) |

| West | 11 (14) |

| Midwest | 13 (17) |

| Northeast | 23 (30) |

Percentages sum to less than 100% because region was unavailable for 1 financial arrangement.

Discussion

The number of surgical services and facilities funded and acquired by PE firms has increased over the past 20 years. Involvement of PE firms in the financing of health care services remains controversial. Acquisitions result in consolidation of health care, which offers theoretical benefits, including a larger market share to negotiate contracts and reimbursement and less administrative costs through economies of scale. Moreover, funding from PE firms can potentially provide capital for new therapies, equipment, and advanced technologies. However, PE firms aim to ultimately increase profits and provide a return on investment, and whether these investments are optimal for patient care is unknown. For example, 1 study4 found that government-owned nursing homes had significantly fewer COVID-19 cases compared with nursing homes funded by PE firms. In another study,5 hospitals acquired by PE firms had increased charge to cost ratios and experienced improvements in process quality measures of medical conditions compared with hospitals not funded by PE firms. Funding from PE firms for surgical care may lead to concerns regarding how financial profits may affect patient care and, specifically, surgical outcomes. Financial involvement of PE firms may result in limited surgeon autonomy if the firm dictates patient-payer mix, may affect how surgical services are offered, and may ultimately lead to promotion of profitable interventions and surgical procedures.

In this study, funding for surgical services by PE firms increased over time and across geographic regions, highlighting a new area of health care investment. A limitation of our study was that our search method was limited to 3 financial databases from which we could acquire data. The results likely underreport the number of investments. To ensure optimal patient care, additional investigation is needed.

References

- 1.Tan S, Seiger K, Renehan P, Mostaghimi A. Trends in private equity acquisition of dermatology practices in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(9):1013-1021. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel SN, Groth S, Sternberg P Jr. The emergence of private equity in ophthalmology. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(6):601-602. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.0964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaye DR, Luckenbaugh AN, Oerline M, et al. Understanding the costs associated with surgical care delivery in the Medicare population. Ann Surg. 2020;271(1):23-28. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun RT, Yun H, Casalino LP, et al. Comparative performance of private-equity owned US nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2026702. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.26702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruch JD, Gondi S, Song Z. Changes in hospital income, use, and quality associated with private equity acquisition. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1428-1435. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]