Key Points

Question

How does skin cancer–specific quality of life (QOL) change for patients after interpolation flap repair of post-Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) nasal defects?

Findings

This cohort study used the Skin Cancer Index to evaluate patient QOL after 2-stage interpolation flap repair of post-Mohs defects on the nose. Quality of life significantly improved 16 weeks after flap takedown compared with pre-MMS QOL.

Meaning

This study suggests that patients can be reassured that skin cancer–related QOL improves after MMS, even for nasal tumors requiring complex reconstruction.

Abstract

Importance

Single-center studies have shown that patients report better skin cancer–specific quality of life (QOL) after Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), but it is unclear whether this improved QOL applies to patients after MMS and complex reconstruction in cosmetically sensitive areas.

Objective

To evaluate patient QOL after MMS and interpolation flap reconstruction for patients with nasal skin cancers.

Design, Setting and Participants

This multicenter prospective survey study used the Skin Cancer Index (SCI), a validated, 15-question QOL questionnaire administered at 4 time points: before MMS, 1 week after flap placement, 4 weeks after flap takedown, and 16 weeks after flap takedown. Patients age 18 years or older with a nasal skin cancer who presented for MMS and were anticipated to undergo 2-stage interpolated flap repair by a Mohs surgeon were recruited from August 9, 2018, to February 2, 2020, at 8 outpatient MMS locations across the United States, including both academic centers and private practices.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Mean difference in overall SCI score before MMS vs 16 weeks after flap takedown.

Results

A total of 169 patients (92 men [54.4%]; mean [SD] age, 67.7 [11.4] years) were enrolled, with 147 patients (75 men [51.0%]; mean [SD] age, 67.8 [11.7] years) completing SCI surveys both before MMS and 16 weeks after flap takedown. Total SCI scores improved significantly 16 weeks after flap takedown compared with pre-MMS scores, increasing by a mean of 13% (increase of 7.11 points; 95% CI, 5.48-8.76; P < .001). All 3 SCI subscale scores (emotion, appearance, and social) improved significantly (emotion subscale, increase of 3.27 points; 95% CI, 2.35-4.18; P < .001; appearance subscale, increase of 1.65 points; 95% CI, 1.12-2.18; P < .001; and social subscale, increase of 2.10 points; 95% CI, 1.55-2.84; P < .001) 16 weeks after flap takedown compared with pre-MMS.

Conclusions and Relevance

Removal of a nasal skin cancer and repair of the resulting defect can be distressing for patients. However, this cohort study suggests that physicians referring patients for MMS can be reassured that their patient’s QOL will improve on average after surgery, even when a complex reconstruction is required.

This cohort study uses the Skin Cancer Index to evaluate patient quality of life after Mohs micrographic surgery and interpolation flap reconstruction for patients with nasal skin cancers.

Introduction

Skin cancer can negatively impact patient quality of life (QOL).1,2 Treatment of skin cancer with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has been associated with improved QOL.3 However, only 28.9% to 32.6% of tumors in studies of MMS were located on the central face, a location for which patient concerns and anxiety are highest.3,4,5,6 This study of nasal tumors removed with MMS and repaired with 2-stage interpolation flaps evaluated patient QOL over time after reconstruction.

Methods

Study Setting and Design

This multicenter prospective cohort study was approved by the institutional review boards at the participating centers. Eight outpatient locations, including both academic centers and private practices (University of Pennsylvania, University of Missouri, The Skin Surgery Center, University of Vermont, Oregon Health & Science University, University of Minnesota, Stanford University, and University of Nebraska) enrolled study participants. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. The study protocol is available in Supplement 1. Patients provided written informed consent; they did not receive payment and were not incentivized to participate in this study.

Participants

Patients age 18 years or older capable of providing informed consent with a nasal skin cancer who presented for MMS and were anticipated to undergo 2-stage interpolated flap repair by a Mohs surgeon were recruited from August 9, 2018, to February 2, 2020. Prospective patients gave written informed consent and were asked to complete a baseline Skin Cancer Index (SCI) questionnaire prior to starting MMS on the day of surgery. Only patients who underwent interpolated flap repair were retained in the study. Fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons or their fellows in training completed all surgical procedures while patients were under local anesthesia in the outpatient setting. Patients were excluded from the study if they underwent a repair other than a 2-stage interpolation flap.

Data Collection

Participants were asked to complete the SCI, a validated survey designed to assess disease-specific QOL in patients with skin cancer, at prespecified points (prior to MMS, 1 week after flap placement, 4 weeks after flap takedown, and 16 weeks after flap takedown). The baseline SCI survey was completed on paper by the study participant prior to MMS and without any prior counseling regarding the repair. Subsequent surveys were either manually completed by study participants using an online platform or administered over the telephone with data entered into the online platform by 1 of 3 study coauthors (T.M.L., A.M.P., or M.P.L.). The SCI is a 15-question survey in which each question is scored on a standard 5-point Likert scale. The questionnaire comprises 3 subscales—emotion (7 questions, minimum score 7, maximum score 35), appearance (3 questions, minimum score 3, maximum score 15), and social (5 questions, minimum score 5, maximum score 25)—that are added together for an overall score ranging from 15 to 75.7 The emotion subscale measures patient anxiety and frustration, the appearance subscale asks about perceived attractiveness and scarring, and the social subscale investigates patient attitudes toward meeting new people and public perception. Higher scores are indicative of a more positive QOL and correlate with greater self-esteem, emotional and mental health, and social functioning.8 The survey instrument can be found in eTable 1 in Supplement 2. Data collection was completed on June 6, 2020.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome of the study was the mean difference in overall SCI scores before MMS and 16 weeks after flap takedown. Only surveys completed in their entirety were included in the analysis. The study was powered to detect a change of 5% from pre-MMS SCI score based on a SCI validation study that reported a pre-MMS score of 60 and SD of 12.8.7 A sample size of 145 achieved 80% power to detect a mean paired difference of 3.0, with an estimated SD of differences of 12.8, with P < .05 considered significant, using a 2-tailed paired t test between pre-MMS SCI score and week 16 after flap takedown SCI score. Loss to follow-up was anticipated and was evaluated as the study progressed. To account for estimated loss to follow-up, the final target sample size to be recruited was increased to 169 patients. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate demographic data and surgical characteristics and to show the trend in SCI over time.

Results

A total of 169 patients (92 men [54.4%], 77 women [45.6%]; mean [SD] age, 67.7 [11.4] years) from 8 centers participated in this study; 147 patients (87.0%; 75 men [51.0%], 72 women [49.0%]; mean [SD] age, 67.8 [11.7] years) completed both the pre-MMS and 16 weeks after flap takedown SCI surveys (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). Patients from the University of Pennsylvania comprised 43.2% of participants (n = 73). Mean and median time between flap placement and takedown was 23.5 and 21 days, respectively. The Table depicts the demographics of the original study cohort (n = 169) and the analytic cohort (n = 147). Basal cell carcinoma was the most common diagnosis (103 of 147 [70.1%]), followed by melanoma (29 of 147 [19.7%]) and squamous cell carcinoma (8 of 147 [5.4%]).

Table. Patient Demographic Characteristics and Case Detailsa.

| Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|

| All enrolled participants (N = 169) | Analytic cohort (n = 147)b | |

| Mean (SD) age, y | 67.7 (11.4) | 67.8 (11.7) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 92 (54.4) | 75 (51.0) |

| Female | 77 (45.6) | 72 (49.0) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| White | 164 (97.0) | 145 (98.6) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 (1.8) | 2 (1.4) |

| Not disclosed | 2 (1.2) | 0 |

| Tumor type | ||

| BCC | 123 (72.8) | 103 (70.1) |

| Melanoma | 31 (18.3) | 29 (19.7) |

| SCC | 9 (5.3) | 8 (5.4) |

| Other | 6 (3.6) | 7 (4.8) |

| Nasal subunits involved | ||

| 1 | 118 (69.8) | 102 (69.4) |

| 2 | 35 (20.7) | 32 (21.8) |

| 3 | 14 (8.3) | 11 (7.5) |

| 4 | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.4) |

| Mean Mohs stage (median [range]) | 2.1 (2 [1-9]) | 2.1 (2 [1-9]) |

| Mean (SD) post-MMS defect size, cm2 | 5.1 (5.6) | 5.2 (5.9) |

| Flap type | ||

| Forehead | 72 (42.6) | 62 (42.2) |

| Cheek-to-nose superiorly based | 66 (39.1) | 58 (39.5) |

| Cheek-to-nose inferiorly based | 31 (18.3) | 27 (18.4) |

| Cartilage graft | ||

| Yes | 38 (22.5) | 33 (22.5) |

| No | 131 (77.5) | 114 (77.6) |

| Involvement of nonnasal subunit | ||

| Yes | 28 (16.6) | 24 (16.3) |

| No | 141 (83.4) | 123 (83.7) |

| Same day resection and flap placementc | ||

| Yes | 165 (97.6) | 143 (97.3) |

| No | 4 (2.4) | 4 (2.7) |

Abbreviations: BCC, basal cell carcinoma; MMS, Mohs micrographic surgery; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Data are presented as number (%) unless noted otherwise.

Participants who completed both pre-MMS and 16 weeks after flap takedown surveys.

Four patients experienced a delay between resection and reconstruction, with reconstruction beginning 2, 6, 14, and 28 days later in each respective case. Reason for delay was not recorded.

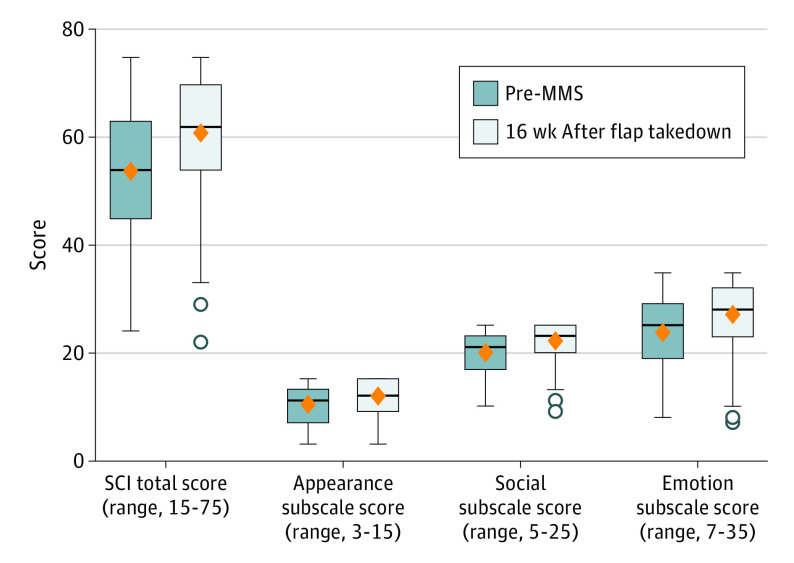

The mean overall SCI scores increased 13% at 16 weeks after flap takedown vs before MMS (increase of 7.11 points; 95% CI, 5.48-8.76; P < .001). Each SCI subscale mean score also increased significantly: there was a 14% increase in the emotion subscale (increase of 3.27 points; 95% CI, 2.35-4.18; P < .001), a 16% increase in the appearance subscale (increase of 1.65 points; 95% CI, 1.12-2.18; P < .001), and an 11% increase in the social subscale (increase of 2.10 points; 95% CI, 1.55-2.84; P < .001). The Figure provides the mean overall SCI scores and individual subscale scores with 95% CIs for pre-MMS and 16 weeks after flap takedown. The mean scores for all time points are provided in eFigure 2 in Supplement 2. There was no significant association between flap type (forehead vs cheek-to-nose) and mean SCI score at any time point (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Figure. Mean Skin Cancer Index (SCI) Total and Subscale Scores Before Mohs Micrographic Surgery (MMS) vs 16 Weeks After Flap Takedown (n = 147).

Error bars indicate 95% CIs, circles indicate outliers, black horizontal lines indicate medians, orange diamonds indicate means, and boxes indicate first and third quartiles.

Discussion

Patient concerns about appearance and potential disfigurement from skin cancer surgery, particularly in cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face, can cause significant anxiety and have a negative effect on psychosocial functioning.6,9 This multicenter prospective study evaluated how skin cancer–specific QOL changes for patients with nasal skin cancers after they undergo MMS and 2-stage interpolation flap reconstruction. Overall patient QOL improved, and improvement was noted across all SCI subscales (emotion, appearance, and social).

Overall SCI scores improved by 13% (increase of 7.11 points; 95% CI, 5.48-8.76, P < .001) from before MMS to 16 weeks after flap takedown. Skin Cancer Index score improvement after MMS has been demonstrated in prior studies, but these studies were not multicenter and did not focus on patients who had skin cancers on the central face or patients who were undergoing complex repair.3,10 These results confirm that QOL improvement after MMS extends to patients undergoing removal of skin cancers in a cosmetically important facial subunit and undergoing complex multistage reconstruction in the outpatient setting.

Quality of life has multiple facets. All 3 SCI subscales (emotion, appearance, and social) significantly improved after surgery in our study. Subscale scores increased from pre-MMS to 16 weeks after flap takedown by 11% to 16%. When a patient has a skin cancer in a cosmetically important region, these results can help physicians inform and reassure patients about the expected trajectory of the emotion, appearance, and social domains of their QOL after MMS surgery.

Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. A total of 147 of the 169 enrolled patients completed all items on the SCI forms at pre-MMS and 16 weeks after flap takedown. However, the 147 patients in the analytic cohort were similar in age, tumor type, reconstruction type, location, race/ethnicity, number of nasal subunits involved, defect size, and number of stages to the original 169 patients who enrolled. Second, this study did not include patients undergoing unanticipated interpolation flap repair or repairs performed under general anesthesia in the operating room. Future research could compare QOL of life across surgical settings for interpolated flaps or QOL differences between nasal defect repair techniques. Third, conversations about choosing a repair and other preoperative counseling methods were not standardized as part of this study. Patients’ expectations and perceptions based on counseling may have affected QOL scores. However, counseling is often variable from one surgeon to another and across medical centers and preserving this variability may increase the generalizability of the results of this study.

Conclusions

In this prospective multicenter cohort study, patients with nasal skin cancers that were treated with MMS and required multistep surgery for reconstruction had improved QOL 16 weeks after reconstruction. Improvement was significant across all subscales of the SCI—emotion, appearance, and social. Despite patient anxiety and aesthetic concerns associated with complex reconstruction of nasal defects, physicians who refer patients for surgery on the nose should feel comfortable reassuring patients about their long-term QOL outcomes.

Study Protocol

eTable 1. Skin Cancer Index

eTable 2. Mean Overall SCI Score by Time Point and Interpolation Flap Type

eFigure 1. Enrollment, Participation, and Inclusion of Study Participants

eFigure 2. Change in Mean Overall SCI and Subscale Scores Over Time

References

- 1.Breitbart W, Holland J. Psychosocial aspects of head and neck cancer. Semin Oncol. 1988;15(1):61-69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornish D, Holterhues C, van de Poll-Franse LV, Coebergh JW, Nijsten T. A systematic review of health-related quality of life in cutaneous melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(suppl 6)(suppl 6):vi51-vi58. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J, Miller CJ, O’Malley V, Etzkorn JR, Shin TM, Sobanko JF. Patient quality of life fluctuates before and after Mohs micrographic surgery: a longitudinal assessment of the patient experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(6):1060-1067. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chren MM, Sahay AP, Bertenthal DS, Sen S, Landefeld CS. Quality-of-life outcomes of treatments for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(6):1351-1357. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borah GL, Rankin MK. Appearance is a function of the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(3):873-878. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181cb613d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sobanko JF, Sarwer DB, Zvargulis Z, Miller CJ. Importance of physical appearance in patients with skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(2):183-188. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhee JS, Matthews BA, Neuburg M, Logan BR, Burzynski M, Nattinger AB. Validation of a quality-of-life instrument for patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006;8(5):314-318. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.8.5.314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhee JS, Matthews BA, Neuburg M, Logan BR, Burzynski M, Nattinger AB. The Skin Cancer Index: clinical responsiveness and predictors of quality of life. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(3):399-405. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31802e2d88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caddick J, Green L, Stephenson J, Spyrou G. The psycho-social impact of facial skin cancers. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65(9):e257-e259. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez N, Griggs J, Nanda S, et al. The Skin Cancer Index: quality-of-life outcomes of treatments for nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31(5):491-493. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1674772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Study Protocol

eTable 1. Skin Cancer Index

eTable 2. Mean Overall SCI Score by Time Point and Interpolation Flap Type

eFigure 1. Enrollment, Participation, and Inclusion of Study Participants

eFigure 2. Change in Mean Overall SCI and Subscale Scores Over Time