Abstract

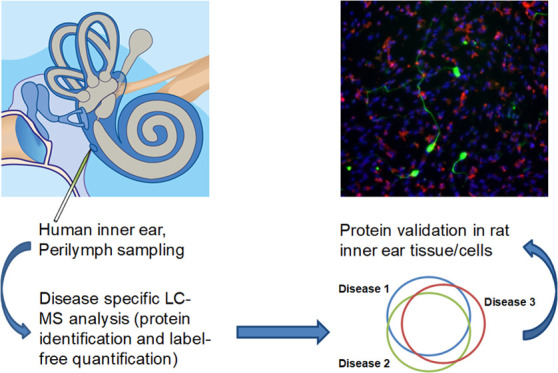

Despite a vast amount of data generated by proteomic analysis on cochlear fluid, novel clinically applicable biomarkers of inner ear diseases have not been identified hitherto. The aim of the present study was to analyze the proteome of human perilymph from cochlear implant patients, thereby identifying putative changes of the composition of the cochlear fluid perilymph due to specific diseases. Sampling of human perilymph was performed during cochlear implantation from patients with clinically or radiologically defined inner ear diseases like enlarged vestibular aqueduct (EVA; n = 14), otosclerosis (n = 10), and Ménière’s disease (n = 12). Individual proteins were identified by a shotgun proteomics approach and data-dependent acquisition, thereby revealing 895 different proteins in all samples. Based on quantification values, a disease-specific protein distribution in the perilymph was demonstrated. The proteins short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family 9C member 7 and esterase D were detected in nearly all samples of Ménière’s disease patients, but not in samples of patients suffering from EVA and otosclerosis. The presence of both proteins in the inner ear tissue of adult mice and neonatal rats was validated by immunohistochemistry. Whether these proteins have the potential for a biomarker in the perilymph of Ménière’s disease patients remains to be elucidated.

Introduction

The human inner ear harbors the vestibular and the cochlear organs. The latter is important for hearing and communication and, in newborns, also for proper development. The cellular and molecular structures in the cochlea are vulnerable to toxic agents and damaging processes, resulting in sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). Hearing loss is the result of a variety of pathological conditions that damage the inner ear. The etiology and pathophysiology of the majority of the conditions leading to hearing loss are still poorly understood. In particular, knowledge of disease-specific molecular changes in the human inner ear is limited due mainly to the difficulty in accessing the human inner ear. Understanding the molecular basis of the disease is an absolutely essential prerequisite to develop improved diagnosis and efficient interventions. Some disease patterns leading to sensorineural hearing loss such as Ménière’s disease (MEN),1,2 enlarged vestibular aqueduct (EVA),3−5 and otosclerosis (OTO)6 are frequently identified based on clinical and/or radiological findings.

Ménière’s disease is a chronic inner ear disease characterized by episodic vertigo associated with fluctuating low- to medium-frequency sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) and tinnitus. The disease commonly begins in the fourth or fifth decade of life, shows a slight female predominance, and increases with increasing age.1 The patients with Ménière’s disease show the presence of an endolymphatic hydrops, which begins with a disturbance of the ionic composition of the scala media and leads to the dilation of the membranous labyrinth of the inner ear. The hearing loss is probably caused by a potassium intoxication of the hair cells during membrane ruptures caused by an increase of endolymphatic pressure because the potassium-rich endolymph blocks the sensory hair cells within the perilymph.2 Also, an overproduction of endolymph occurs by an altered expression of water and ion channels like aquaporins.2 Additionally, increased levels of cochlin in the basilar membranes of the crista ampullaris and macula utricle in subjects with Ménière’s disease have been reported.7 A widely accepted hypothesis indicates that multiple genetic and environmental factors as well as several regulatory factors such as the innate immune response, the endocrine system, and the autonomic nervous system, and trigger factors like allergens, infectious agents, and genetic variants can contribute to the development of Ménière’s disease.1

The enlarged vestibular aqueduct (EVA) is a very frequently diagnosed reason for (progressive) inner ear hearing loss and can also affect the vestibular system. Especially in the pediatric population, it is a frequent cause for congenital or childhood-onset hearing loss and is radiographically detectable.5 The vestibular aqueduct contains the endolymphatic duct terminating in the endolymphatic sac and depicts a bony structure connecting the vestibule with the posterior cranial fossa. EVA syndrome is sometimes associated with an enlarged endolymphatic sac, Pendred’s syndrome, distal renal tubular acidosis, Waardenburg’s syndrome, X-linked congenital mixed deafness, branchio-oto-renal syndrome, otofaciocervical syndrome, and Noonan’s syndrome. Mutations in the SLC26A4 gene encoding the protein pendrin, involved in the cellular transport of chloride, iodine, and bicarbonate anions, can cause Pendred’s syndrome as well as nonsyndromic recessive deafness (DFNB4) and are also associated with EVA.4 There are different hypotheses for the etiology of EVA. EVA could allow the transfer of elevated pressure shifts into the inner ear, leading to the damage of the sensible structures of the inner ear like hair cells, resulting in hearing loss.4 Another theory assumes that EVA leads to histological changes of the epithelia of the endolymphatic sac and duct and that the resulting large volumes of endolymph impair the ion pump mechanism of the stria vascularis in the inner ear, leading to an electrolyte imbalance. This reflux theory suggesting that this phenomenon could lead to hearing loss was confirmed by computed tomography (CT) and, in the first instance, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the inner ear of EVA patients. However, the exact mechanisms remain unclear because of the various etiologic differences between patients.4

Otosclerosis is characterized by bone remodeling of the bony parts of the otic capsule (pericochlear, perilabyrinthine, regions adjacent to the oval and round window, as well as in the stapes footplate), leading to mostly bilateral conductive, sensorineural, or mixed hearing loss. The onset of progressive hearing loss occurs in the fourth or fifth decade. Possible reasons for the development of otosclerosis include viral, genetic, inflammatory, autoimmune, environmental, hormonal, and other factors.8,9 An association with otosclerosis to the genes COL1A1 and RELN was discussed since both genes were also influenced by sex, explaining the female prevalence of this disease.9 Also, other genes might be associated with otosclerosis, like the ACE gene, the AGT gene, OTSC2, and the TGFB1 gene.9,10 The bone metabolism is regulated by two processes, the endocrine network on the one hand, and a local network of interactions between osteoclasts, osteoblasts, and different mediators like cytokines on the other hand. A possible explanation for the otosclerotic process might be an imbalance or uncoupling of these two processes, also seen in arthritis or in other inflammatory diseases.11

Restoration of hearing is mainly based on technical devices either with the support of hearing aids for sound amplification or with cochlear implants for direct electrical stimulation of the auditory neurons. The electrode array of the cochlear implant is inserted into the inner ear, providing an invaluable route to access the otherwise not accessible inner ear. Both diagnostic sampling of inner ear fluids and local intracochlear application of therapeutics are possible in the setting of cochlear implantation. Thus, precision diagnostics based on perilymph sampling is placed within reach.

Proteome analysis is the centerpiece in large-scale biology due the today’s already very high sensitivity of this method and further expected developments in the future.12 Tissues in contact with biological fluids release protein components that can be detected in the surrounding fluids. In our recent study, we could detect perilymph proteins assigned to extracellular compartments like extracellular exosomes with supposed origin in inner ear tissues.13 Diseased tissues may be characterized by the type or the amount of the released proteins. Thus, proteomics depicts the method of choice due to the minimal required volumes for analysis and the plurality of different proteins detectable in one analysis leading to a putative disease-specific protein distribution pattern in the perilymph. Thus, the chance to identify proteins as biomarkers by proteomic analysis of bodily fluids has been pursued in many fields, including otology, using proteomics for perilymph analysis.13−17 Sampling fluid from the compartments surrounding the diseased tissue may, for several reasons, be better for identifying biomarkers of nonsystemic diseases. When compared with plasma, other bodily fluids such as cerebrospinal fluid, saliva, vitreous fluid, or perilymph are more likely to collect proteins from a few or even one tissue type. Thus, the composition of the perilymph fluid is more likely to reflect the state of the inner ear and might be a valuable source of disease-specific marker proteins.

The complexity of data generated by liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS) may not only reflect the proteome of diseased organ tissues but, as was recently shown for vitreoretinal diseases, uncovered numerous biomarkers and identified protein targets for approved drugs.18 Equally, the biochemical composition of the human perilymph, especially the changes of perilymph composition occurring during inner ear diseases, may give information about the surrounding tissue and may also display pathological conditions at a molecular level. In recent years, we and others provided solid proof of the feasibility of perilymph sampling and analysis to define the cochlear microenvironment not only by analyzing the proteome13−16,19 but also the inflammasome,20 microRNA (miRNA) profile,21,22 and proteins related to the heat shock23 as well as the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)17 pathway in humans by combining the proteomic profile with gene expression arrays, residual organ function, and bioinformatic analysis.

In the present study, a comparative analysis was performed in patients with clinically and/or radiologically defined inner ear diseases. Despite the lack of perilymph from healthy individuals, we aim to identify disease-specific proteins that are significantly altered in their abundance. These proteins might be involved in processes in the inner ear, leading to severe sensorineural hearing loss of patients diagnosed with Ménière’s disease, EVA, and otosclerosis. Of the patients with these defined inner ear diseases receiving cochlear implantation, perilymph samples were collected and proteins were identified as well as quantified. Therefore, we identified different perilymph proteomes by direct comparison of the pathological conditions, leading to Ménière’s disease, EVA, and otosclerosis. The protein short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family 9C member 7 (SDR9C7), also named orphan short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR-O), and S-formylglutathione hydrolase (FGH), also named esterase D (ESD), were unique for the perilymph of Ménière’s disease patients. To localize the expression site of these proteins, we stained the inner ear tissue of adult mice and neonatal rats with SDR9C7 and ESD antibodies. We herein provide for the first time personalized proteomics of patients suffering from defined inner ear diseases allowing, as has been shown in other fields, the identification of molecular constituents in the diseased tissue that may be used for early precision diagnosis and for the development of targeted treatment approaches.18

Results

Overall, 36 human perilymph samples were collected during cochlear implantations of patients suffering from Ménière’s disease (n = 12 patients; n = 12 samples), EVA (n = 10 patients; n = 14 samples), or otosclerosis (n = 9 patients; n = 10 samples), leading to sensorineural hearing loss. The samples taken during cochlear implantations were analyzed by LC-MS-based proteomics and data-dependent acquisition. The average age (Table 1) of the EVA group is 10.78 years and differs from the Ménière’s (61.24 years) and otosclerosis (56.87 years) group. In the EVA group, mainly children were included because the early diagnosis of an enlarged aqueduct is easily detectable by computed tomography and is part of the routine diagnostic before cochlear implantation. Ménière’s disease and otosclerosis are commonly apparent and diagnosed in adult patients.

Table 1. Demographic Data of Study Patientsa.

| demographic data | Ménière’s disease | EVA | otosclerosis | n* in % (Ménière’s disease/EVA/otosclerosis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| patients (n) | 12 | 10 | 9 | |

| age (mean in years) | 61.24 | 10.78 | 56.87 | |

| male (n) | 7 | 6 | 3 | 58.3/60/33.3 |

| female (n) | 5 | 4 | 6 | 41.7/40/66.7 |

| children (0–18 years) | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0/70/0 |

| adults (19–80) | 12 | 3 | 9 | 100/30/100 |

| perilymph samples (n) | 12 | 14 | 10 | |

| sample volume in average (μL) | 1.9 | 7.1 | 3.1 | |

| PTA | 84.4 | 112 | 96.6 |

Pure tone audiometry (PTA): missing values were added; children were not allowed to take part in PTA testing, therefore, values from brainstem evoked response audiometry (BERA) and electrocochleography (ECOCHG) were used for calculating a PTA value.

The proteome raw data analysis of all perilymph samples led to the identification of 895 different proteins. Table 2 shows 33 perilymph proteins, which were detected in every perilymph sample (n = 36) and are therefore common in all disease groups. These 33 proteins account for only 4% of the complete perilymph proteins detected in this study. In Figure 1, the distribution of all detected proteins is shown in the left VENN diagram. In this diagram, proteins detected in only a few perilymph samples are also depicted. In the right VENN diagram, all proteins detected in less than eight perilymph samples per disease group were removed, leading to a reduced number of 304 proteins; 96% of these proteins (n = 291) were detected in perilymph samples of all three disease groups. There were two proteins (short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family 9C member 7 and S-formylglutathione hydrolase) that were only detected in the perilymph samples of patients suffering from Ménière’s disease but in none of the samples collected from EVA and otosclerosis patients. Of these two proteins, short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family 9C member 7 was identified in 11 of the 12 samples of Ménière patients. The protein S-formylglutathione hydrolase was detected in 9 of the 12 Ménière’s disease perilymph samples. Therefore, these two proteins may indicate the possible perilymph biomarkers of Ménière’s disease. Data of all proteins associated with Figure 1 are shown in the Supporting Information (Tables S1 and S2).

Table 2. Proteins Ubiquitous in All Perilymph Samples.

| majority protein IDs | protein names | gene names |

|---|---|---|

| O43405 | cochlin | COCH |

| P00450 | ceruloplasmin | CP |

| P00734 | prothrombin | F2 |

| P00738 | haptoglobin | HP |

| P01009 | α-1-antitrypsin | SERPINA1 |

| P01011 | α-1-antichymotrypsin | SERPINA3 |

| P01023 | α-2-macroglobulin | A2M |

| P01024 | complement C3 | C3 |

| P01042 | kininogen-1 | KNG1 |

| P02647 | apolipoprotein A-I | APOA1 |

| P02649 | apolipoprotein E | APOE |

| P02671 | fibrinogen α chain | FGA |

| P02749 | β-2-glycoprotein 1 | APOH |

| P02766 | transthyretin | TTR |

| P02787 | serotransferrin | TF |

| P02790 | hemopexin | HPX |

| P04004 | vitronectin | VTN |

| P04114 | apolipoprotein B-100 | APOB |

| P04196 | histidine-rich glycoprotein | HRG |

| P04217 | α-1B-glycoprotein | A1BG |

| P05090 | apolipoprotein D | APOD |

| P05155 | plasma protease C1 inhibitor | SERPING1 |

| P06727 | apolipoprotein A-IV | APOA4 |

| P08603 | complement factor H | CFH |

| P10909 | clusterin | CLU |

| P15924 | desmoplakin | DSP |

| P25311 | zinc-α-2-glycoprotein | AZGP1 |

| P32119 | peroxiredoxin-2 | PRDX2 |

| P41222 | prostaglandin-H2 D-isomerase | PTGDS |

| P68871 | hemoglobin subunit β | HBB |

| P69905 | hemoglobin subunit α | HBA1 |

| Q14151 | scaffold attachment factor B2 | SAFB2 |

| Q8N7L0 | protein FAM216B | FAM216B |

Figure 1.

Number of identified perilymph proteins in the three disease groups. In the VENN diagram, the distribution of the detected 895 perilymph proteins in otosclerosis (n = 10 samples), Ménière’s disease (n = 12 samples), and EVA (n = 14 samples) is shown. Left: All over analysis: all proteins detected in the disease groups are shown (n = 895). In this figure, it is not considered in how many samples the protein was detected. Right: more stringent analysis: only proteins detected in at least eight samples of one of the disease groups are shown (n = 304). The highlighted proteins are considered as disease-specific because they are identified only in samples of Ménière’s disease patients.

For further analyses, the stringent list, especially the label-free quantification (LFQ) quantification data, was modified using an imputation algorithm. To include proteins with unknown intensities in the statistical analysis, an imputation algorithm was used that uses a normal distribution and a width of 0.3 compared to the measured values. Since proteins, for which no quantitative values are available, might have been not detected due to an abundance below the detection limit, also a downshift of the intensity by a factor of 3.5 protein intensities has been imputed. Statistical analyses were performed to point out higher and lower abundant perilymph proteins in a direct comparison of the three disease groups: Ménière’s disease, EVA, and otosclerosis. Therefore, three comparison analyses were performed and higher abundant proteins were identified in each analysis (p = 0.05, Student’s t-test). Between Ménière’s disease and EVA samples, 97 proteins with significantly different abundance were identified, 71 proteins had a significantly higher abundance in Ménière’s disease, and 26 proteins had a higher abundance in EVA samples. The comparison of Ménière’s disease and otosclerosis samples led to 99 significantly different abundant proteins. Of these proteins, 92 proteins had significantly higher abundance in Ménière’s disease and 7 proteins had significantly higher abundance in otosclerosis. EVA compared to otosclerosis led to 90 significantly different abundant proteins, 69 proteins had significantly higher abundance in EVA, and 21 proteins had significantly higher abundance in otosclerosis (Figure 2). Significantly higher and lower abundant proteins are pointed out in Table S3. This indicates that there should be disease-specific perilymph proteins that might help to better understand molecular mechanisms involved in inner ear diseases and might also have potential as a biomarker.

Figure 2.

Vulcano plots of the proteins identified in the perilymph of the three disease groups. In the vulcano plots, (A–C) proteins identified by mass spectrometric analyses are shown in a direct comparison of each two considered diseases. The boxes mark the proteins with significant differences between the two considered disease patterns (Student’s t-test p < 0.05 and Student’s t-test difference >1). Ménière’s disease (MEN), otosclerosis (OTO). (A) Ménière vs EVA: 71 proteins with significantly higher abundance in Ménière’s disease are shown in the box on the right side and 26 proteins with significantly higher abundance in EVA are shown in the box on the left side. (B) Ménière vs otosclerosis: 92 proteins with significantly higher abundance in Ménière’s disease are shown in the box on the right side and 7 proteins with significantly higher abundance in otosclerosis are shown in the box on the left side. (C) Otosclerosis vs EVA: 69 proteins with significantly higher abundance in EVA are shown in the box on the right side and 21 proteins with significantly higher abundance in otosclerosis are shown in the box on the left side.

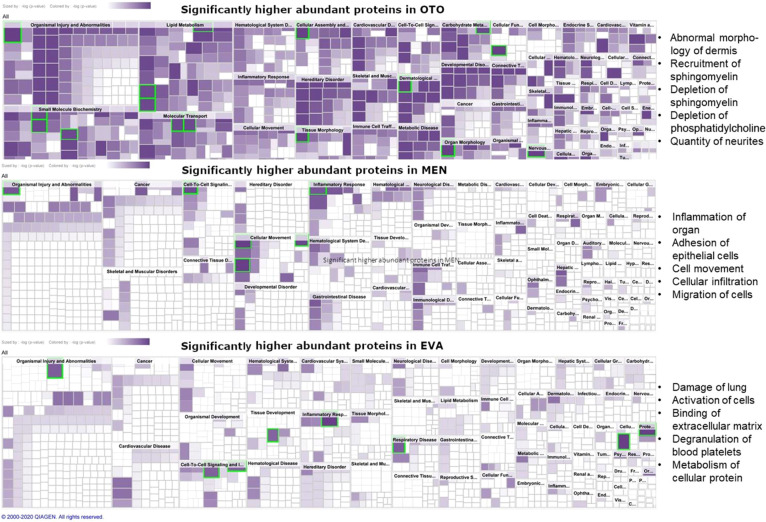

All significantly higher abundant proteins are listed in Table S3. Proteins that exhibit significantly different abundances in the comparison of a disease group to the other two disease groups (Tables 3–7) were further analyzed using ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) software to obtain a functional annotation of the proteins with different abundances, visualized in disease and function heat maps and networks (Figures 3 and S1–S5).

Table 3. Fourteen Proteins had a High Abundance in EVA But a Low Abundance in Ménière’s Disease and Otosclerosis.

| majority protein IDs | protein names | gene names |

|---|---|---|

| P20774 | mimecan | OGN |

| P98160 | basement membrane-specific heparan sulfate proteoglycan core protein | HSPG2 |

| P29622 | kallistatin | SERPINA4 |

| Q13822 | ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase family member 2 | ENPP2 |

| P01009 | α-1-antitrypsin | SERPINA1 |

| P23083 | Ig heavy chain V-I region V35 | IGHV1–2 |

| P02774 | vitamin D-binding protein | GC |

| P02765 | α-2-HS-glycoprotein | AHSG |

| P05546 | heparin cofactor 2 | SERPIND1 |

| P04004 | vitronectin | VTN |

| P01008 | antithrombin-III | SERPINC1 |

| Q14112 | nidogen-2 | NID2 |

| P05155 | plasma protease C1 inhibitor | SERPING1 |

| P02787 | serotransferrin | TF |

Table 7. Thirty-Seven Proteins had a Low Abundance in Otosclerosis But a High Abundance in EVA and Ménière’s Disease.

| majority protein IDs | protein names | gene names |

|---|---|---|

| P98160 | basement membrane-specific heparan sulfate proteoglycan core protein | HSPG2 |

| O43505 | β-1,4-glucuronyltransferase 1 | B4GAT1 |

| Q92823 | neuronal cell adhesion molecule | NRCAM |

| Q12860 | contactin-1 | CNTN1 |

| P41222 | prostaglandin-H2 D-isomerase | PTGDS |

| Q8TEU8 | WAP, Kazal, immunoglobulin, Kunitz, and NTR domain-containing protein 2 | WFIKKN2 |

| P05154 | plasma serine protease inhibitor | SERPINA5 |

| Q92859 | neogenin | NEO1 |

| P05543 | thyroxine-binding globulin | SERPINA7 |

| P12109 | collagen α-1(VI) chain | COL6A1 |

| P01042 | kininogen-1 | KNG1 |

| O43405 | cochlin | COCH |

| P08697 | α-2-antiplasmin | SERPINF2 |

| P01011 | α-1-antichymotrypsin | SERPINA3 |

| Q08380 | galectin-3-binding protein | LGALS3BP |

| O00391 | sulfhydryl oxidase 1 | QSOX1 |

| Q6X4T0 | uncharacterized protein C12orf54 | C12orf54 |

| P01019 | angiotensinogen | AGT |

| P02774 | vitamin D-binding protein | GC |

| P36222 | chitinase-3-like protein 1 | CHI3L1 |

| P02765 | α-2-HS-glycoprotein | AHSG |

| P02751 | fibronectin | FN1 |

| P07942 | laminin subunit β-1 | LAMB1 |

| P04180 | phosphatidylcholine-sterol acyltransferase | LCAT |

| P08185 | corticosteroid-binding globulin | SERPINA6 |

| P07360 | complement component C8 γ chain | C8G |

| O75882 | attractin | ATRN |

| P49788 | retinoic acid receptor responder protein 1 | RARRES1 |

| Q8NE18 | putative methyltransferase NSUN7 | NSUN7 |

| Q86UD1 | out at first protein homolog | OAF |

| Q86UX2 | inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H5 | ITIH5 |

| O14594 | neurocan core protein | NCAN |

| Q16769 | glutaminyl-peptide cyclotransferase | QPCT |

| P05156 | complement factor I | CFI |

| Q12805 | EGF-containing fibulin-like extracellular matrix protein 1 | EFEMP1 |

| P08603 | complement factor H | CFH |

| O00533 | neural cell adhesion molecule L1-like protein | CHL1 |

Figure 3.

Disease and function heat maps of significantly higher abundant proteins. Proteins identified in the three disease groups were uploaded and analyzed using IPA software. Three disease and function maps are shown: otosclerosis (OTO; top), Ménière’s disease (MEN; middle), and EVA (bottom). Interestingly, in all three considered disease patterns also an inflammatory component is visible. The most significant disease and function components are highlighted in green. These processes are depicted in the list to the right of the heat maps.

Higher Abundant Proteins in EVA

In total, 14 proteins had a higher abundance in EVA but a lower abundance in perilymph samples of patients with Ménière’s disease and otosclerosis (Table 3). They are related to the top canonical pathways LXR/RXR activation, FXR/RXR activation, acute phase response signaling, the coagulation system, and clathrin-mediated endocytosis signaling. In the category molecular and cellular function, most proteins were involved in protein synthesis, cellular compromise, cell-to-cell signaling and interaction, cellular movement, and cellular function and maintenance.

The top associated network functions identified using IPA software, in which many of the higher abundant proteins of the EVA perilymph samples were involved, are: protein synthesis, cellular compromise, and inflammatory response (Figure S1).

Lower Abundant Proteins in EVA

In total, 12 proteins had a lower abundance in perilymph samples from EVA patients but a higher abundance in perilymph samples from patients with Ménière’s disease and otosclerosis (Table 4).

Table 4. Twelve Proteins had a Low Abundance in EVA But a High Abundance in Ménière’s Disease and Otosclerosis.

| majority protein IDs | protein names | gene names |

|---|---|---|

| P01859 | Ig γ-2 chain C region | IGHG2 |

| P07358 | complement component C8 β chain | C8B |

| Q5T749 | keratinocyte proline-rich protein | KPRP |

| P06702 | protein S100A9 | S100A9 |

| P08670 | vimentin | VIM |

| Q06830 | peroxiredoxin-1 | PRDX1 |

| Q02413 | desmoglein-1 | DSG1 |

| P30740 | leukocyte elastase inhibitor | SERPINB1 |

| P81605 | dermcidin | DCD |

| P04406 | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | GAPDH |

| P21333 | filamin-A | FLNA |

| P00558 | phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | PGK1 |

Significantly lower abundant proteins in EVA patients’ perilymph were involved in the top canonical pathways glycolysis I, gluconeogenesis I, reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) repair, ILK signaling, and systemic lupus erythematosus signaling. In the category molecular and cellular function, most proteins were involved in cell-to-cell signaling and interaction, cell morphology, cellular movement, cellular development, and cellular growth and proliferation.

The top associated network functions identified using IPA software, in which many of the lower abundant proteins of the EVA perilymph samples were involved, are: (1) cell-to-cell signaling and interaction, cell morphology, and cellular movement (Figure S2). (2) Cellular development, cellular growth and proliferation, and embryonic development.

Higher Abundant Proteins in Ménière’s Disease

Thirty-three proteins had a higher abundance in Ménière’s disease but a lower abundance in EVA and otosclerosis (Table 5).

Table 5. Thirty-Three Proteins had a High Abundance in Ménière’s Disease But a Low Abundance in EVA and Otosclerosis.

| majority protein IDs | protein names | gene names |

|---|---|---|

| P60709 | actin, cytoplasmic 1 | ACTB |

| P09211 | glutathione S-transferase P | GSTP1 |

| O00299 | chloride intracellular channel protein 1 | CLIC1 |

| P10768 | S-formylglutathione hydrolase | ESD |

| P01876 | Ig α-1 chain C region | IGHA1 |

| Q6ZRV2 | protein FAM83H | FAM83H |

| Q8NEX9 | short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family 9C member 7 | SDR9C7 |

| P02671 | fibrinogen α chain | FGA |

| P09104 | γ-enolase | ENO2 |

| P60174 | triosephosphate isomerase | TPI1 |

| Q92835 | phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate 5-phosphatase 1 | INPP5D |

| P02675 | fibrinogen β chain | FGB |

| P04075 | fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A | ALDOA |

| P63261 | actin, cytoplasmic 2 | ACTG1 |

| P55290 | cadherin-13 | CDH13 |

| O75369 | filamin-B | FLNB |

| P02458 | collagen α-1(II) chain | COL2A1 |

| Q92876 | kallikrein-6 | KLK6 |

| Q16706 | α-mannosidase 2 | MAN2A1 |

| P00736 | complement C1r subcomponent | C1R |

| P19320 | vascular cell adhesion protein 1 | VCAM1 |

| P40925 | malate dehydrogenase, cytoplasmic | MDH1 |

| P43251 | biotinidase | BTD |

| P62937 | peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase A | PPIA |

| P10645 | chromogranin-A; vasostatin-1; serpinin | CHGA |

| O15394 | neural cell adhesion molecule 2 | NCAM2 |

| O75635 | serpinB7 | SERPINB7 |

| O75882 | attractin | ATRN |

| P04114 | apolipoprotein B-100 | APOB |

| Q5JTZ5 | uncharacterized protein C9orf152 | C9orf152 |

| P43121 | cell surface glycoprotein MUC18 | MCAM |

| P02452 | collagen α-1(I) chain | COL1A1 |

| P00738 | haptoglobin | HP |

Significantly higher abundant proteins in Ménière’s disease patients’ perilymph were involved in the top canonical pathways: the intrinsic prothrombin activation pathway, glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, GP6 signaling pathway, and atherosclerosis signaling. In the category molecular and cellular function, most proteins were involved in cellular movement, cell-to-cell signaling and interaction, cellular compromise, cellular assembly and organization, and carbohydrate metabolism.

The top associated network functions identified using IPA software, in which many of the higher abundant proteins of the Ménière’s disease perilymph samples were involved, are: (1) hematological disease, cell-to-cell signaling and interaction, and embryonic development (Figure S3); (2) cellular movement, hematological disease, and immunological disease; and (3) cell cycle, DNA replication, recombination and repair, and cellular assembly and organization.

Lower Abundant proteins in Ménière’s Disease

Only the protein hemoglobin subunit γ-1 had a lower abundance in Ménière’s disease but a higher abundance in EVA and otosclerosis. Because of only one identified protein, no further IPA analysis was performed.

Higher Abundant Proteins in Otosclerosis

Four proteins had a higher abundance in otosclerosis but a lower abundance in EVA and Ménière’s disease (Table 6).

Table 6. Four Proteins had a High Abundance in Otosclerosis But a Low Abundance in EVA and Ménière’s Disease.

Significantly higher abundant proteins in otosclerosis patients’ perilymph were involved in the top canonical pathways: clathrin-mediated endocytosis signaling, remodeling of epithelial adherens junctions, actin nucleation by ARP-WASP complex, regulation of actin-based motility by rho, and Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages and monocytes. In the category molecular and cellular function, most proteins were involved in cellular assembly and organization, cellular function and maintenance, carbohydrate metabolism, cell-to-cell signaling and interaction, and cellular compromise.

The top associated network functions identified using IPA software, in which many of the higher abundant proteins of the otosclerosis perilymph samples were involved, are: cancer, organismal injury and abnormalities, and respiratory disease (Figure S4).

Lower Abundant Proteins in Otosclerosis

Thirty-seven proteins had a lower abundance in otosclerosis but had a higher abundance in EVA and Ménière’s disease (Table 7).

Significantly lower abundant proteins in otosclerosis patients’ perilymph were involved in the top canonical pathways: LXR/RXR activation, FXR/RXR activation, acute phase response signaling, the coagulation system, and the complement system. In the category molecular and cellular function, most proteins were involved in cellular movement, cellular compromise, cell-to-cell signaling and interaction, cell morphology, and protein synthesis.

The top associated network functions identified using IPA software, in which many of the lower abundant proteins of the otosclerosis perilymph samples were involved are: (1) cellular movement, cellular compromise, and inflammatory response (Figure S5). (2) The cell cycle, reproductive system development and function, gene expression. (3) Cardiovascular disease, organismal injury and abnormalities, tissue morphology.

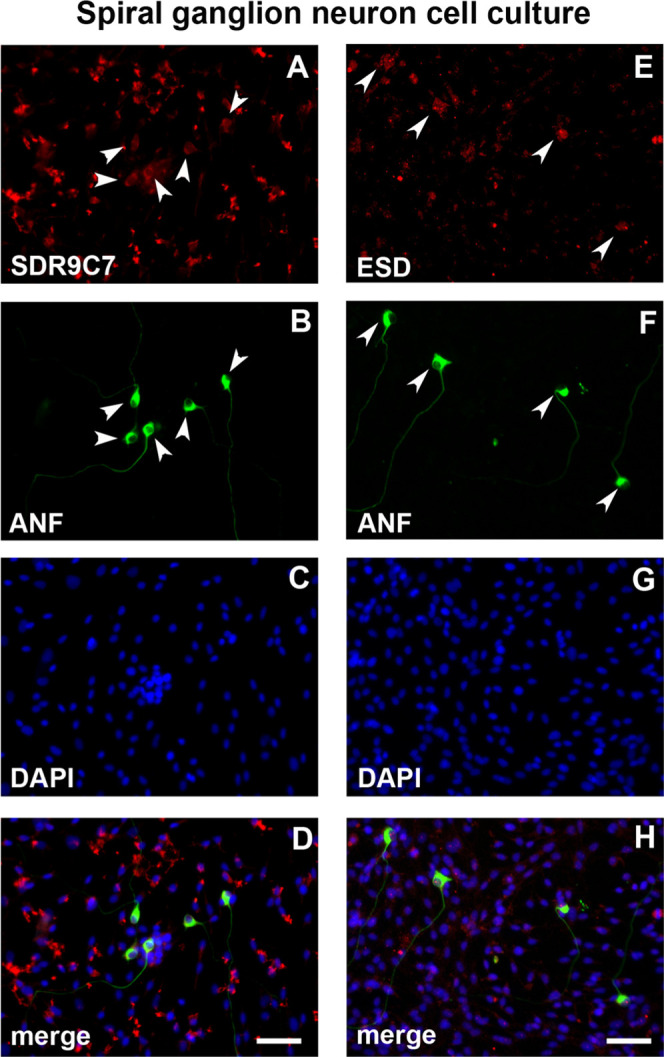

Immunohistochemistry in the Inner Ear Tissue of Adult Mice and Neonatal Rats and in Dissociated Spiral Ganglion Neuron (SGN) Cell Cultures

Immunohistochemical staining was performed for the proteins SDR9C7 and ESD in neonatal rats (whole mounts and dissociated spiral ganglion neurons) and adult mice (paraffin sections) for confirming their presence in inner ear tissues (Figures 4 and 5). The protein SDR9C7, also named SDR-O, was detected in the somata of SGN, the hair cells of adult mice (Figure 4A), and the inner and outer hair cells (IHC and OHC), especially in the stereocilia of the hair cells in neonatal rats (Figure 4C,E). The protein ESD was visible in the somata of SGN, the hair cells of adult mice (Figure 4B), and the neurofilament positive neurites of the SGN in neonatal rats (Figure 4D,F).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry of SDR9C7 and ESD. (A) In the inner ear of adult mice, the proteins SDR9C7 ((A) red) and ESD ((B) red) were detected in the somata of SGN and the inner and outer hair cells (IHC, OHC). In the whole mount preparations of neonatal rat cochleae, SDR9C7 ((C, E) green) was visible in the inner and outer hair cells (IHC, OHC) and the stereocilia of the hair cells. This was confirmed by additional staining of the hair cells with phalloidin (red). ESD ((D, F) red) was visible in neurites of SGN. In (A) and (B), the cell nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI) in blue, and in all images the scale bar is 50 μm.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry of SDR9C7 and ESD in dissociated SGN. The microscopic images showed double staining with SDR9C7 ((A) red) or ESD ((E) red) antibodies and 200 kDa neurofilament ((B, F) ANF, green), which is a neuron-specific antibody in the SGN cell culture of neonatal rats. Nuclei were stained with DAPI in blue (C, G). Arrowheads point at the labeling of SDR9C7 (A) or ESD (E) in the somata of stained SGN. Additionally, SDR9C7 (A) and ESD (E) immunosignals were also present in the supporting cells of SGN cell cultures. Merged images of the double-immunostainings (SDR9C7/ESD in red and ANF in green) in combination with DAPI staining were depicted in (D) and (H). Scale bar: 50 μm.

In the dissociated SGN cell culture of neonatal rats, SDR9C7 and ESD showed double labeling with the 200 kDa neurofilament positive somata of SGN (Figure 5). Moreover, the supporting cells (fibroblasts and glial cells) in the dissociated SGN cell culture of neonatal rats were stained positive for SDR9C7 and ESD. Thus, both in human perilymph identified proteins are expressed in the inner ear tissue.

Discussion

We here provide the first evidence of disease-specific protein profiles in perilymph samples of patients with Ménière’s disease, EVA, and otosclerosis. Using LC-MS-based proteomics, we identified 895 different proteins in all perilymph samples and obtained intensity values for relative quantification, also enabling the comparison of differences in the abundances of each protein. By further data selection and statistical analysis, we could identify different abundant proteins for each disease group (Tables 3–7). These disease-specific proteins may reflect the molecular pathologic changes in the perilymph composition of the examined disease patterns. Certain mutations of the COCH gene, which encodes the most abundant extracellular matrix protein cochlin in the cochlea and vestibule of the inner ear, lead to hereditary late onset autosomal-dominant nonsyndromic sensorineural hearing loss (DFNA9) in combination with vestibular dysfunctions.24 In the basilar membranes of the crista ampullaris and macula utricle of Ménière’s disease patients, an increased level of cochlin deposition and expression was observed.7 Interestingly, we observed significantly higher levels of cochlin in the perilymph samples of Ménière’s disease and EVA patients compared to otosclerosis patients. In our mass spectrometric perilymph analysis, we identified a significantly higher abundance of fibrinogen α chain in Ménière’s disease perilymph samples compared to EVA and also otosclerosis perilymph samples. Complement factor H had a significantly higher abundance in Ménière’s disease and EVA perilymph compared to otosclerosis perilymph samples. A higher level of these two proteins was also detected by mass spectrometric analysis in the plasma of Ménière’s disease patients compared to healthy controls in the study of Chiarella et al.,25 showing a similar increased level in perilymph and plasma of Ménière’s disease patients for fibrinogen α chain and complement factor H.

Among the significantly higher abundant proteins in Ménière’s disease perilymph are two proteins, which seem unique for Ménière’s disease since they have not been detected in the perilymph of otosclerosis and EVA patients. The protein short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family 9C member 7 (SDR9C7) was uniquely detected in 11 of 12 samples of Ménière’s disease patients, but not in samples of patients suffering from EVA and otosclerosis. This enzyme is an oxidoreductase, a single domain protein, and shows a weak retinol dehydrogenase activity. SDR9C7 is also named as orphan short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR-O) and catalyzes the conversion of retinal into retinol in the presence of the cofactor NADH and appears to be involved in vitamin A metabolism.26 In normal healthy skin, SDR9C7 protein was predominantly expressed in granular and cornified layers of the epidermis, whereas a missense mutation in the SDR9C7 gene leads to autosomal recessive ichthyosis.27 SDR9C7 catalyzes NAD+-dependent dehydrogenation of the lipoxygenase products esterified in ceramide esterified omega-hydroxy sphingosine (CerEOS) to the corresponding 13-ketone (CerEOS-epoxy-enone) that can bind to proteins. SDR9C7 facilitates the covalent binding of oxidized acylceramide to cornified cell envelope proteins, thus forming the skin barrier.28

The protein S-formylglutathione hydrolase (FGH), also named esterase D (ESD), was detected in 9 of 12 Ménière’s disease perilymph samples but not in samples of patients suffering from EVA and otosclerosis. FGH is a glutathione thiol esterase expressed by the esterase D gene that catalyzes the conversion of S-formylglutathione to glutathione (GSH), which is an important antioxidant in the cell, and formate. The expression and activity of FGH are regulated by short-form Klotho (Skl, an aging-suppressor gene) and may also regulate cellular oxidative stress.29

The two proteins SDR9C7 and ESD are uniquely identified in the perilymph of Ménière’s disease patients, and their potential as a biomarker for inner ear disease has to be confirmed in further studies. It could be possible that Ménière’s disease might lead to cochlear leakage, resulting in the liberation of higher amounts of these proteins in the small volume of the perilymph. Additionally, we checked our perilymph library, including the analyzed samples also published in the study by Schmitt et al.13—a total of 75 perilymph samples—for the presence of SDR9C7 and ESD. The protein SDR9C7 was additionally detected in three perilymph samples—one from a 68-year-old man with single-sided deafness, tinnitus, and multiple sudden hearing losses, one from a child (0.8 years) suffering from intrauterine cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, and one from a 3-year-old child with congenital hearing loss and gusher during cochlear implant surgery by opening the round window membrane, indicating an elevated inner ear pressure. The protein ESD was also detected in the perilymph of one man diagnosed with Ménière’s disease in the contralateral ear. In our as reference analyzed serum and CSF samples from patients predominantly suffering from vestibular schwannoma, we have not identified the protein ESD. The protein SDR9C7 seems to be perilymph specific because it was not detected in our mass spectrometric analyzed CSF and serum samples13 and in comparison to common serum and CSF databases available online (http://www.plasmaproteomedatabase.org, accessed date 2017/09/16; CSF database reported by Zhang et al.,30Supporting Information).

For further characterization of the location of these two proteins in the inner ear, cochlear tissues and cells of neonatal rats and adult mice were stained by immunohistochemistry. This analysis could only be performed in animal tissue and not in human tissue because of the nonavailability of human inner ear tissue. In rodents, SDR-O could be detected in the somata of SGN and in the stereocilia of hair cells (adult mice and neonatal rats) as well as in supporting cells (neonatal rats) (Figures 4 and 5). The protein ESD was visible in the somata (adult mice) and neurites of SGN (neonatal rats) as well as in supporting cells (neonatal rats) (Figures 4 and 5). Comparing these results with the knowledge of databases analyzing inner ear neurons on a single cell level confirmed our results regarding ESD.31 The protein ESD has been detected along the tonotopic axis in type I as well as in type II SGN with a relatively high abundance. However, these data could not confirm the expression of SDR9C7 in inner ear neurons. In the whole mount preparation of neonatal mice, we could detect SDR9C7 in the area of the inner and outer hair cells.

α-1-Antitrypsin (AAT) was present in significantly higher abundance in the perilymph of EVA patients compared to Ménière’s disease and otosclerosis patient’s perilymph. AAT is a circulating serine protease inhibitor and plays a role in the innate biochemical defense system and is usually upregulated in response to acute or chronic inflammation.32 In a previous study, we could show that decreased AAT levels in the perilymph fluid of the inner ear appear to display a relationship with the severity of hearing loss.33

There were other two proteins identified, which showed significant differences between the three diseases: basement membrane-specific heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) core protein and attractin. The protein HSPG, also named perlecan, was statistically significant with the highest abundance in EVA patients’ perilymph, followed by Ménière’s disease patients and the lowest abundance in the perilymph otosclerosis patients. This protein is primarily localized in basement membranes and pericellular spaces and is also expressed in a wide array of tissues. HSPG acts as a homeostatic regulator within a vast array of cellular processes, including cell adhesion, endocytosis, bone and cartilage formation, lipid metabolism, peripheral node assembly, inflammation and wound healing, thrombosis, cancer angiogenesis, cardiovascular development, and autophagy. HSPG coordinates angiogenesis by providing pro- and anti-angiogenic properties within the same molecule. HSPG applies for complex regulatory roles over the vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA)/vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) and α2β1 integrin signaling axes.34 In Figure S1, the top network of high-abundant proteins of the EVA perilymph samples (marked in gray) are shown in this network created using IPA software. The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a central part in this network but was not identified by our mass spectrometric analysis. In our recent study,35 we demonstrated the presence of VEGF in perilymph analyzed by a multiplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Summarizing the results of this previous study and our finding that in EVA patient’s perilymph proteins involved in the VEGF pathway are of higher abundance (Figure S1 and Table 3), there are indications that in EVA patient’s perilymph, many proteins involved in inflammatory processes were enriched. Therefore, we suggest that our data support the theory of damage or even ruptures of sensible structures in the cochlea of patients suffering from EVA, leading to an increased inflammatory response. In another complementary study, the presence of macrophages or even immune cell machinery in the endolymphatic sac and, therefore, protection of the sensitive inner ear structures was discussed.36

The protein attractin was statistically significant with the highest abundance in Ménière’s disease patient’s perilymph, followed by EVA patients and the lowest abundance in the perilymph of otosclerosis patients. Attractin is a circulating serum glycoprotein and is rapidly expressed on activated T cells and plays a significant role in the immune response in vivo.37

Polymorphisms in the RELN and AGT genes were discussed to be statistically significantly associated with otosclerosis.9,38 In our MS analysis, we identified the protein reelin in none of the perilymph samples of otosclerosis patients, in about 50% of Ménière’s patients, and in 36% of EVA patients. The protein angiotensinogen was significantly reduced in the perilymph samples of otosclerosis compared to samples of patients suffering from EVA and Ménière’s disease.

Precision health care has already entered everyday life by monitoring and diagnostics utilizing wearable health sensors. Based on personalized risk profiles, precision health may enable early diagnosis by the detection of subclinical decline before disease-specific symptoms appear. As we move from symptom-oriented diagnosis of disease to a precision health approach, we are on the cusp of a new era. For inner ear disorders, this would mean to move from symptom-oriented therapies to precise molecular treatment approaches delineating the beginning of a new era in otology equally anticipated by physicians, scientists, and biotechnology companies.

Despite its high complexity, protein analysis in the perilymph increases the probability of identifying biomarkers related to the associated disease. The challenge is the invasive procedure of the fluid collection, preventing the analysis of healthy control subjects. The rather limited availability makes their use for early or even screening biomarker detection in patients with less severe symptoms difficult. Initial data from earlier studies show that perilymph sampling presents a safe procedure that does not further damage the cochlea.13,15 Thus, we are optimistic that data from hearing people will emerge in the future, helping to characterize the healthy cochlear environment.

Many proteins were identified in all three disease groups and may not exhibit biomarker function. However, the 101 proteins listed in Tables 3–7 were significantly altered in their abundance compared to the two other disease groups. These proteins showed different networks in which they were integrated as identified using IPA software. Thus, we assume that a disease signature may be detectable in the perilymph. The 101 proteins in Tables 3–7 may either originate from tissue leakage or regulation. From other proteomic studies on bodily fluids, lists of up to hundreds of differentially expressed proteins are available. For biomarker identification, the definition of a biomarker needs careful consideration.39 A biological marker can be objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of physiological or pathological processes.40 Generally, proteomic analysis based on MS can analyze every single protein in a system and determine causal biological relationships.41 In the inner ear, the challenge of validated analysis in small volumes has been overcome not only for proteomics and metabolomics14,19 but also for miRNA and the inflammasome.35 The latter is based on an immunoassay, showing that this technique can also be applied to small volumes enabling another step toward individualized precision diagnostics. Quantitative methods based on immunoassays need to be developed for each marker candidate to verify the biomarker criteria, i.e., precision and accuracy. Among the proteins in the tables of the herein presented study, a potential biomarker can be identified. For implementation into the clinic, studies on large cohorts of hundreds or thousands of patients during the clinical validation phase may be required. Thus, our results are just the beginning of the discovery of new biomarkers. To this end, standardized proteomic workflows to fulfill quality criteria to focus the biomarker selection process on the most valuable candidates are necessary.42

Provided their successful verification and validation, the two potential diagnostic biomarkers identified in the perilymph of patients with Ménière’s disease may be either utilized to recognize an overt disease or even to categorize the severity of the disease. Validated biomarkers could even be utilized to prove therapy response.

In other areas, ratios of abundances are employed, e.g., ASAT/ALAT to differentiate liver diseases or the soluble Fms-like tyrosinkinase-1 (sFlt-1)/placental growth factor (PlGF) ratio for the diagnosis of preeclampsia.43 Whether abundance ratios of the inner ear-specific proteins can be used to differentiate inner ear diseases needs further investigation.

The advantage of the herein presented study is the preselection of patients by clinicians, enhancing the precise definition of the clinical condition of interest. It has been stated that “high fidelity phenotyping” is mandatory to assure the highest quality clinical data.42

By comparing the proteome of patients in three different disease groups, increased specificity of the results can be achieved. A limitation of the herein presented study is—despite presenting the largest series published thus far—the relatively small number of patients included. In addition, the lack of data from normal hearing subjects further limits the presented results. The only study to our knowledge reporting on proteome data from normal hearing cochleae was derived from individuals suffering from meningiomas.15 In the data depository available from this study, we could not find the two proteins present in patients with Ménière’s disease, SDR9C7, or ESD. Furthermore, verification by targeted proteomics and validation by quantitative immunoassays of the two potential biomarkers are missing.

Materials and Methods

Sampling of Human Perilymph in Patients with Specific Diseases

Meniere’s disease was diagnosed according to the guidelines of the Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium44 (the clinical presence of (I) two or more definitive spontaneous episodes of vertigo, 20 min or longer, (II) audiometrically documented hearing loss on at least one occasion, (III) tinnitus or aural fullness in the treated ear, and (IV) exclusion of other causes). Nine patients fulfilled these criteria completely, and in three more patients, specific proof of endolymphatic hydrops was seen clinically and objectified by electrocochleography and dehydration tests.

The enlarged vestibular aqueduct was defined as the midpoint or opercular widths of 1.0 and 2.0 mm or greater in CT scans (axial planes) according to the “Cincinnati criteria”.4,45

Otosclerosis was diagnosed in patients in whom bony destruction of the labyrinth was present and/or in whom the fixation of the stapes was described in previous stapes surgery and in whom competing causes, such as status post radiotherapy or tumorous diseases, were excluded.

Perilymph samples were collected during uni- or bilateral cochlear implantations by inserting the tip of a microglass capillary through the round window membrane as described previously.13 The study patients were suffering from Ménière’s disease (n = 12 patients; n = 12 samples), EVA (n = 10 patients; n = 14 samples), and otosclerosis (n = 9 patients; n = 10 samples). In the group of patients suffering from EVA, perilymph samples from both ears (3 × bilateral cochlear implantation, 1 × 1 year between unilateral cochlear implantations left/right) of four patients are included in the analysis. Three EVA patients suffered from additional diseases like incomplete partition type II (n = 3) or Pendred syndrome (n = 1). In the group of patients suffering from otosclerosis, perilymph samples from both ears of one patient were taken at different time points (3 years between unilateral cochlear implantations left/right). The perilymph sample volumes ranged from 0.5 to 12 μL. Patients aged 8 months up to 80 years were included in this study. The demographic data of the patients are shown in Table 1.

The protocols for the collection of perilymph were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (approval no. 1883-2013). Written informed consent was obtained from every patient included in this study.

Proteome Analysis

In our prior study, the intraoperative perilymph sampling method during cochlear implantations was described in detail. Additionally, the analysis of the collected perilymph samples (small sample sizes in a microliter range) by an in-depth shotgun proteomics approach was established, allowing the analysis of hundreds of proteins simultaneously and described in detail.13,17,23 The relative protein quantification was performed by label-free quantification (LFQ) and was determined as LFQ intensity. Label-free quantification of detected proteins in the three disease groups was performed using maxQuant software. For statistical analysis, proteins detected in at least eight samples of the three groups were compared after data imputation using Perseus software.

Additionally, proteins were subjected to classification by Gene Ontology Annotations (GOA) using UniProt.46 The Gene Ontology (GO) classification allows a mapping of the proteins into the categories molecular function, biological process, and cellular compartment. Proteins were described using a standardized vocabulary of the UniProt Knowledgebase by uploading the UniProt IDs of the proteins to the UniProt website http:/www.uniprot.org.

Audiologic Data of Patients

Pure tone audiometry (PTA) was performed before surgery and perilymph sampling. The preoperative audiograms were used to further classify the groups of patients (Ménière’s disease, EVA, otosclerosis). Therefore, the PTA was calculated as the average of the frequency regions 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz. BERA and ECOCHG measurements were used as an alternative PTA in young children.

Statistical Analysis

Mass spectrometric raw data were processed using MaxQuant software (version 1.4) and human entries of the Swissprot/UniProt database.47,48 The threshold for protein identification was set to <0.01 on peptide and protein levels. The LFQ values of the proteins were imputated after the selection of these proteins at least in eight samples within a disease group. The imputated LFQ values were used for statistical analysis by Student’s t-test.

Disease-specific proteomics data were analyzed and compared using Perseus49 and ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA, Qiagen Bioinformatics, http://www.ingenuity.com) software.50 By statistical analysis for each of the three considered diseases, significant differences in the levels of numerous proteins were determined. Proteins detected in at least eight samples of a disease group and after imputation of data (replacement of missing values by normal distribution) were used for statistical analysis. Student’s t-test was performed (p < 0.05) for the identification of proteins, with significant differences in the quantification of proteins detected in the three patient groups.

Immunohistochemistry of Cochlea Preparations

Ethics

Cochleae and spiral ganglion neurons (SGN) were isolated from neonatal Sprague Dawley rats (postnatal day 3–5) in accordance with the German animal welfare act. The euthanasia for tissue sampling is registered (no.: 2016/118) with the local authorities (Zentrales Tierlaboratorium, Laboratory Animal Science, Hannover Medical School, including an institutional animal care and use committee) and is reported on a regular basis as demanded by law. For the exclusive sacrifice of animals for tissue analysis in research, no further approval is needed if no other treatment is applied beforehand (Materials and Methods section).

Dissociated Spiral Ganglion Neuron Culture (Neonatal Rats)

Sprague Dawley rats of both sexes were used for the preparation of the primary SGN cell culture. The isolation and cultivation of SGN have been described in detail in a previous publication.51 Briefly, isolated cochleae were microscopically dissected, followed by enzymatic and mechanical dissociation of the spiral ganglia. Viable cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion using a Neubauer chamber (Brandt, Wertheim, Germany). Before cell seeding, the 96-well plates were coated with poly-d/l-ornithine (0.1 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) and laminin (0.01 mg/mL; natural from mouse, Life Technologies, Carlsbad). The dissociated cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well in 96-well plates (Nunc, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA). The SGN medium consisted of Panserin 401 (PAN Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany) supplemented with N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES)-buffer (23.43 mM; Invitrogen), phosphate-buffered saline (0.172 mg/mL; PBS tablets, Gibco by Life Technologies), glucose (0.15%; B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany), penicillin (30 U/mL; Biochrom, Germany), insulin (8.7 μg/mL; Biochrom, Germany), and N2-supplement (0.1 μg/mL; Invitrogen). For this investigation, fetal calf serum (FCS, 10%, Biochrom) was additionally added to the medium. After 72 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2, the cells were fixed with a 1:1 acetone (J. T. Baker, Deventer, Netherlands)/methanol (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) solution for 10 min and were washed with PBS (PBS tablets, Gibco by Life Technologies).

Immunohistochemistry

The dissociated SGN cultures were mixed cultures containing neurons, fibroblasts, and glial cells. For identification of SGN, neuron-specific staining with a mouse 200 kDa neurofilament antibody (clone RT97; Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) was performed. Additionally, the nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI), and the two proteins of interest with antibodies against ESD and SDR-O (Table 8). The protocol of immunocytochemistry has been described in a previous publication.52 Briefly, after the removal of PBS, the fixed cells were washed for 10 min with washing buffer (WB; 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis) in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Then, the cells were blocked with a blocking solution (1% bovine serum albumin, BSA, Sigma-Aldrich in PBS) for 30 min, followed by incubation for 1 h with the diluted primary antibodies diluted in 0.5% BSA in WB (Table 8). Afterward, the samples were washed two times with WB for 15 min. Secondary antibodies (Table 8) were diluted in 0.5% BSA in WB and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the cells. After the addition of the secondary antibodies, the samples were handled in the dark. Controls were performed by omitting the primary antibodies. Finally, the samples were washed again and stored in PBS. Images were made using the fluorescence microscope BZ-9000 (Keyence, Osaka, Japan).

Table 8. Antibodies Used for Immunohistochemistry.

| primary antibody | dilution | antigen | company, cat.-no | secondary antibody | dilution | company, cat.-no |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| monoclonal mouse anti-neurofilament 200 kDa-antibody | 1:200 | 200 kDa Neurofilament (SGNs) | Leica Biosystems, #NF200-N52-L-CE | Goat anti-mouse Alexa 488 | 1:500 | Jackson Immuno Research, #115-545-00 |

| polyclonal rabbit anti-esterase D (n-terminal) | 1:50 | ESD | Aviva Systems Biology, #ARP58619-P050 | Goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 | 1:500 | Jackson Immuno Research, #111-585-144 |

| Polyclonal rabbit anti-SDR-O | 1:50 | SDR-O | Biorbyt, #orb453699 | Goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 | 1:500 | Jackson Immuno Research, #111-585-144 |

| DAPI | 1:250 | Applichem, #a4099,0010 | ||||

| ESD polyclonal antibody | (4 μg/mL) | Invitrogen, PA5-58890 | Alexa Fluor Donkey 555 anti-Rabbit | 1:1000 | Abcam, ab150074 | |

| anti-SDR9C7 (short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family 9C member 7) | (1 μg/mL) | USbiological Life Sciences, Cat#: 479660 | Alexa Fluor Donkey 555 anti-Rabbit | 1:1000 | Abcam, ab150074 |

Whole Mount Preparations (Neonatal Rats)

For whole mount preparations of the cochlea, the capsule of the cochlea was carefully removed and the spiral ganglion with the organ of Corti was detached from the modiolus. The membranous cochlea was divided into a basal, medial, and apical part. These were transferred on already prepared microscope slides with circles drawn with an ImmEdge Pen (hydrophobic barrier PAP, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame) and a drop of 50 μL PBS. Now the same staining protocol as mentioned above was performed until the last washing step. After the removal of the PBS, the samples were mounted with a ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Molecular Probes by Life Technologies). Images were made using the fluorescence microscope BZ-9000 (Keyence).

Temporal Bone Preparation of Adult Mice

Mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal applications of phenobarbital (585 mg/kg) and phenytoin sodium (75 mg/kg) (Beuthanasia-D Special, Schering-Plough Animal Health Corp., Union, NJ, Canada) and sacrificed via intracardiac perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The temporal bones were removed. The stapes were extracted and the round window was opened. The temporal bones were postfixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4 °C. After rinsing in PBS three times for 30 min, the temporal bones were decalcified in 10% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for 48 h. The temporal bones were rinsed in PBS, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin.

Immunohistochemistry

Ten micrometer sections were cut parallel to the modiolus, mounted on Fisherbrand Superfrost/Plus Microscope Slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and dried overnight. The samples were deparaffinized and rehydrated in PBS two times for 5 min, then three times in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, and finally in blocking solution 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS with 10% fetal bovine serum for 30 min at room temperature. After blocking, specimens were treated with antibodies (Table 8) diluted to concentration with a blocking solution. The tissue was incubated for 48 h at 4 °C in a humid chamber. After three rinses in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS, immunohistochemical detection was carried out using an Alexa Fluor Donkey 555 anti-Rabbit. The secondary antibody was incubated for 6 h at room temperature in a humid chamber. The slides were rinsed in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS three times for 5 min and finally coverslipped with the ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Imaging was carried out with a Nikon C-1 confocal microscope.

Conclusions

We herein present the first comparative study of proteome analysis in patients with three different clinically defined inner ear diseases. The protein short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family 9C member 7 (SDR9C7) is only present in the perilymph of patients with Ménière’s disease. Whether this protein has the potential for a biomarker in the perilymph of patients with Ménière’s disease or is even involved etiologically remains to be elucidated. Another protein, S-formylglutathione hydrolase (FGH), was present in the majority of the patients with Ménière’s disease, but in none of the patients from the other disease groups.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank R. Salcher, K. Willenborg, and M. Teschner for their support in sampling of perilymph during inner ear surgeries as well as M. Ben Amor and M. Schwebs for their technical assistance.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- EVA

enlarged vestibular aqueduct

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry

- DDA

data-dependent acquisition

- SDR9C7

short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family 9C member 7

- SDR-O

orphan short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase

- ESD

esterase D

- FGH

S-formylglutathione hydrolase

- IPA

ingenuity pathway analysis

- PTA

pure tone audiometry

- BERA

brainstem evoked response audiometry

- ECOCHG

electrocochleography

- LTQ

linear trap quadrupole

- CID

collision-induced dissociation

- LFQ

label-free quantification

- GOA

Gene Ontology Annotations

- SGN

spiral ganglion neurons

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- DAPI

4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride

- WB

washing buffer

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- ETDA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- SNHL

sensorineural hearing loss

- CT

computed tomography

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- GSH

glutathione

- AAT

α-1-antitrypsin

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFA

vascular endothelial growth factor A

- VEGFR2

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2

- ASAT

aspartate transaminase

- ALAT

alanine transaminase

- sFlt-1

soluble Fms-like tyrosinkinase-1

- PlGF

placental growth factor

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c01136.

By in-depth shotgun proteomics detected perilymph proteins before and after the selection and statistical analysis of the data; top networks of higher/lower-abundant proteins of one disease group after comparison to the two other disease groups created using IPA software (Figures S1–S5) (PDF)

Table of protein distribution in perilymph (Table S1); table of protein distribution in perilymph; more stringent list—proteins detected in the minimum of eight perilymph samples per disease group (Table S2); table of significant abundant proteins (Table S3) (XLSX)

Author Contributions

This manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the DFG Cluster of Excellence EXC 2177/1 “Hearing4all”.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Espinosa-Sanchez J. M.; Lopez-Escamez J. A.. Menière’s Disease. Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier B.V., 2016; Vol. 137, pp 257–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama G.; Lopez I. A.; Sepahdari A. R.; Ishiyama A. Meniere’s Disease: Histopathology, Cytochemistry, and Imaging. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1343, 49–57. 10.1111/nyas.12699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T.; Westerberg B. D.; Atashband S.; Kozak F. K. Natural History of Hearing Loss in Children with Enlarged Vestibular Aqueduct Syndrome. J. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2008, 37, 112–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopen Q.; Zhou G.; Whittemore K.; Kenna M. Enlarged Vestibular Aqueduct: Review of Controversial Aspects. Laryngoscope 2011, 121, 1971–1978. 10.1002/lary.22083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemi A. S.; Chan D. K. Progressive Hearing Loss and Head Trauma in Enlarged Vestibular Aqueduct: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2015, 153, 512–517. 10.1177/0194599815596343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashishth A.; Fulcheri A.; Prasad S. C.; Bassi M.; Rossi G.; Caruso A.; Sanna M. Cochlear Implantation in Cochlear Ossification: Retrospective Review of Etiologies, Surgical Considerations, and Auditory Outcomes. Otol. Neurotol. 2018, 39, 17–28. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada A. P.; Lopez I. A.; Beltran Parrazal L.; Ishiyama A.; Ishiyama G. Cochlin Expression in Vestibular Endorgans Obtained from Patients with Meniere’s Disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2012, 350, 373–384. 10.1007/s00441-012-1481-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karosi T.; Sziklai I. Etiopathogenesis of Otosclerosis. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2010, 267, 1337–1349. 10.1007/s00405-010-1292-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittermann A. J. N.; Wegner I.; Noordman B. J.; Vincent R.; van der Heijden G. J. M. G.; Grolman W. An Introduction of Genetics in Otosclerosis. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2014, 150, 34–39. 10.1177/0194599813509951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thys M.; Schrauwen I.; Vanderstraeten K.; Janssens K.; Dieltjens N.; Van Den Bogaert K.; Fransen E.; Chen W.; Ealy M.; Claustres M.; Cremers C. R. W. J.; Dhooge I.; Declau F.; Claes J.; Van de Heyning P.; Vincent R.; Somers T.; Offeciers E.; Smith R. J. H.; Van Camp G. The Coding Polymorphism T263I in TGF-B1 Is Associated with Otosclerosis in Two Independent Populations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007, 16, 2021–2030. 10.1093/hmg/ddm150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liktor B.; Szekanecz Z.; Batta T. J.; Sziklai I.; Karosi T. Perspectives of Pharmacological Treatment in Otosclerosis. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2013, 793. 10.1007/s00405-012-2126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley N. M.; Hebert A. S.; Coon J. J. Proteomics Moves into the Fast Lane. Cell Syst. 2016, 2, 142–143. 10.1016/j.cels.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt H. A.; Pich A.; Schröder A.; Scheper V.; Lilli G.; Reuter G.; Lenarz T. Proteome Analysis of Human Perilymph Using an Intraoperative Sampling Method. J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16, 1911–1923. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaght A. C.; Kao S. Y.; Paulo J. A.; Merchant S. N.; Steen H.; Stankovic K. M. Proteome of Human Perilymph. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 3845–3851. 10.1021/pr200346q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H. C.; Ren Y.; Lysaght A. C.; Kao S. Y.; Stankovic K. M. Proteome of Normal Human Perilymph and Perilymph from People with Disabling Vertigo. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0218292 10.1371/journal.pone.0218292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen J. E.; Laurell G.; Rask-Andersen H.; Bergquist J.; Eriksson P. O. The Proteome of Perilymph in Patients with Vestibular Schwannoma. A Possibility to Identify Biomarkers for Tumor Associated Hearing Loss?. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0198442 10.1371/journal.pone.0198442PONE-D-18-04726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries I.; Schmitt H.; Lenarz T.; Prenzler N.; Alvi S.; Staecker H.; Durisin M.; Warnecke A. Detection of BDNF-Related Proteins in Human Perilymph in Patients With Hearing Loss. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 214 10.3389/fnins.2019.00214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velez G.; Tang P. H.; Cabral T.; Cho G. Y.; Machlab D. A.; Tsang S. H.; Bassuk A. G.; Mahajan V. B. Personalized Proteomics for Precision Health: Identifying Biomarkers of Vitreoretinal Disease. Transl. Vision Sci. Technol. 2018, 7, 12 10.1167/tvst.7.5.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavel S.; Lefèvre A.; Bakhos D.; Dufour-Rainfray D.; Blasco H.; Emond P. Validation of Metabolomics Analysis of Human Perilymph Fluid Using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectroscopy. Hear. Res. 2018, 367, 129–136. 10.1016/j.heares.2018.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnecke A.; Prenzler N. K.; Schmitt H.; Daemen K.; Keil J.; Dursin M.; Lenarz T.; Falk C. S. Defining the Inflammatory Microenvironment in the Human Cochlea by Perilymph Analysis: Toward Liquid Biopsy of the Cochlea. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 665 10.3389/fneur.2019.00665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shew M.; Warnecke A.; Lenarz T.; Schmitt H.; Gunewardena S.; Staecker H. Feasibility of MicroRNA Profiling in Human Inner Ear Perilymph. NeuroReport 2018, 29, 894–901. 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shew M.; New J.; Wichova H.; Koestler D. C.; Staecker H. Using Machine Learning to Predict Sensorineural Hearing Loss Based on Perilymph Micro RNA Expression Profile. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3393 10.1038/s41598-019-40192-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt H.; Roemer A.; Zeilinger C.; Salcher R.; Durisin M.; Staecker H.; Lenarz T.; Warnecke A. Heat Shock Proteins in Human Perilymph. Otol. Neurotol. 2018, 39, 37–44. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolis E. A Gene for Non-Syndromic Autosomal Dominant Progressive Postlingual Sensorineural Hearing Loss Maps to Chromosome 14q12-13. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1996, 5, 1047–1050. 10.1093/hmg/5.7.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarella G.; Saccomanno M.; Scumaci D.; Gaspari M.; Faniello M. C.; Quaresima B.; Di Domenico M.; Ricciardi C.; Petrolo C.; Cassandro C.; Costanzo F. S.; Cuda G.; Cassandro E. Proteomics in Ménière Disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 2012, 227, 308–312. 10.1002/jcp.22737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalik D.; Haller F.; Adamski J.; Moeller G. In Search for Function of Two Human Orphan SDR Enzymes: Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase like 2 (HSDL2) and Short-Chain Dehydrogenase/Reductase-Orphan (SDR-O). J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009, 117, 117–124. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigehara Y.; Okuda S.; Nemer G.; Chedraoui A.; Hayashi R.; Bitar F.; Nakai H.; Abbas O.; Daou L.; Abe R.; Sleiman M. B.; Kibbi A. G.; Kurban M.; Shimomura Y. Mutations in SDR9C7 Gene Encoding an Enzyme for Vitamin A Metabolism Underlie Autosomal Recessive Congenital Ichthyosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, ddw277 10.1093/hmg/ddw277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeichi T.; Hirabayashi T.; Miyasaka Y.; Kawamoto A.; Okuno Y.; Taguchi S.; Tanahashi K.; Murase C.; Takama H.; Tanaka K.; Boeglin W. E.; Calcutt M. W.; Watanabe D.; Kono M.; Muro Y.; Ishikawa J.; Ohno T.; Brash A. R.; Akiyama M. SDR9C7 Catalyzes Critical Dehydrogenation of Acylceramides for Skin Barrier Formation. J. Clin. Invest. 2020, 130, 890–903. 10.1172/JCI130675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Sun Z. Regulation of S-Formylglutathione Hydrolase by the Anti-Aging Gene Klotho. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 88259–88275. 10.18632/oncotarget.19111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Guo Z.; Zou L.; Yang Y.; Zhang L.; Ji N.; Shao C.; Sun W.; Wang Y. A Comprehensive Map and Functional Annotation of the Normal Human Cerebrospinal Fluid Proteome. J. Proteomics 2015, 119, 90–99. 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha B. R.; Chia C.; Wu L.; Kujawa S. G.; Liberman M. C.; Goodrich L. V. Sensory Neuron Diversity in the Inner Ear Is Shaped by Activity. Cell 2018, 174, 1229.e17–1246.e17. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. S.; Yoon Y. J.; Lee E. J. Studies on Distribution of A1-Antitrypsin, Lysozyme, Lactoferrin, and Mast Cell Enzymes in Diseased Middle Ear Mucosa. Acta Otolaryngol. 2014, 134, 791–795. 10.3109/00016489.2014.913198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Saied S.; Schmitt H.; Durisin M.; Joshua B.; Abu Tailakh M.; Prenzler N.; Lenarz T.; Kaplan D. M.; Lewis E. C.; Warnecke A. Endogenous A1-antitrypsin Levels in the Perilymphatic Fluid Correlates with Severity of Hearing Loss. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2020, 45, 495–499. 10.1111/coa.13541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubbiotti M. A.; Neill T.; Iozzo R. V. A Current View of Perlecan in Physiology and Pathology: A Mosaic of Functions. Matrix Biol. 2017, 57–58, 285–298. 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnecke A.; Prenzler N. K.; Schmitt H.; Daemen K.; Keil J.; Dursin M.; Lenarz T.; Falk C. S. Defining the Inflammatory Microenvironment in the Human Cochlea by Perilymph Analysis: Toward Liquid Biopsy of the Cochlea. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 665 10.3389/fneur.2019.00665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kämpfe Nordström C.; Danckwardt-Lillieström N.; Laurell G.; Liu W.; Rask-Andersen H. The Human Endolymphatic Sac and Inner Ear Immunity: Macrophage Interaction and Molecular Expression. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 3181 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke-Cohan J. S.; Gu J.; McLaughlin D. F.; Xu Y.; Freeman G. J.; Schlossman S. F. Attractin (DPPT-L), a Member of the CUB Family of Cell Adhesion and Guidance Proteins, Is Secreted by Activated Human T Lymphocytes and Modulates Immune Cell Interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998, 95, 11336–11341. 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrauwen I.; Thys M.; Vanderstraeten K.; Fransen E.; Dieltjens N.; Huyghe J. R.; Ealy M.; Claustres M.; Cremers C. R. W. J.; Dhooge I.; Declau F.; Van de Heyning P.; Vincent R.; Somers T.; Offeciers E.; Smith R. J. H.; Van Camp G. Association of Bone Morphogenetic Proteins With Otosclerosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008, 23, 507–516. 10.1359/jbmr.071112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomaa N. A.; Jimoh Z.; Campbell S.; Zenke J. K.; Szczepek A. J. Biomarkers for Inner Ear Disorders: Scoping Review on the Role of Biomarkers in Hearing and Balance Disorders. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 42 10.3390/diagnostics11010042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson A. J.; Colburn W. A.; DeGruttola V. G.; DeMets D. L.; Downing G. J.; Hoth D. F.; Oates J. A.; Peck C. C.; Schooley R. T.; Spilker B. A.; Woodcock J.; Zeger S. L. Biomarkers and Surrogate Endpoints: Preferred Definitions and Conceptual Framework. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 69, 89–95. 10.1067/mcp.2001.113989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aebersold R.; Mann M. Mass-Spectrometric Exploration of Proteome Structure and Function. Nature 2016, 537, 347–355. 10.1038/nature19949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischak H.; Apweiler R.; Banks R. E.; Conaway M.; Coon J.; Dominiczak A.; Ehrich J. H. H.; Fliser D.; Girolami M.; Hermjakob H.; Hochstrasser D.; Jankowski J.; Julian B. A.; Kolch W.; Massy Z. A.; Neusuess C.; Novak J.; Peter K.; Rossing K.; Schanstra J.; Semmes O. J.; Theodorescu D.; Thongboonkerd V.; Weissinger E. M.; Van Eyk J. E.; Yamamoto T. Clinical Proteomics: A Need to Define the Field and to Begin to Set Adequate Standards. Proteomics: Clin. Appl. 2007, 1, 148–156. 10.1002/prca.200600771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer P. E.; Holdt L. M.; Teupser D.; Mann M. Revisiting Biomarker Discovery by Plasma Proteomics. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2017, 942 10.15252/msb.20156297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Evaluation of Therapy in Menière’s Disease. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 1995, 113, 181–185. 10.1016/S0194-5998(95)70102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]