Abstract

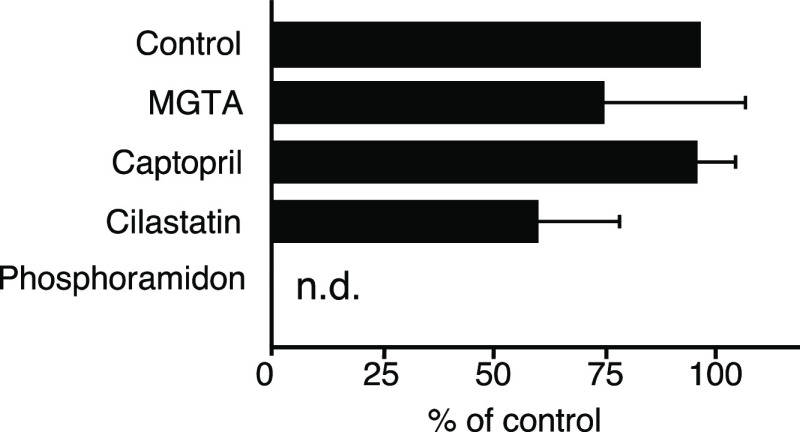

Copper-64 (64Cu)-labeled antibody fragments such as Fab are useful for molecular imaging (immuno-PET) and radioimmunotherapy. However, these fragments cause high and persistent localization of radioactivity in the kidneys after injection. To solve this problem, this study assessed the applicability of a molecular design to 64Cu, which reduces renal radioactivity levels by liberating a urinary excretory radiometabolite from antibody fragments at the renal brush border membrane (BBM). Since 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid (NOTA) forms a stable complex with Cu, NOTA-conjugated Met-Val-Lys-maleimide (NOTA-MVK-Mal), which is a radio-gallium labeling agent for antibody fragments, was evaluated for applicability to 64Cu. The MVK linkage was recognized by the BBM enzymes to liberate [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Met although the recognition of the MVK sequence for the [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK derivative was reduced compared with that of its [67Ga]Ga-counterpart, probably due to the difference in the charge of the metal-NOTA complexes. When injected into mice, [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab resulted in similar renal radioactivity levels to the 67Ga-labeled counterpart. In addition, [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab resulted in lower renal radioactivity levels than those from 64Cu-labeled Fab using a conventional method, without a reduction in the tumor radioactivity levels. These findings indicate that our approach to reducing renal radioactivity levels by liberating a radiolabeled compound from antibody fragments at the renal BBM for urinary excretion is applicable to 64Cu-labeled antibody fragments and useful for immuno-PET and radioimmunotherapy.

Introduction

Antibodies and constructs labeled with radionuclides such as indium-111, zirconium-89, and copper-64 (64Cu) are used to visualize target expression and study their pharmacokinetics in living subjects.1−4 Because positron emission tomography (PET) provides more quantitative and higher-resolution images than single-photon emission computed tomography, antibodies and constructs labeled with positron-emitting radionuclides have recently been developed (immuno-PET).1−3 Although intact antibodies have been widely used for immuno-PET, constructs such as Fab and single-chain Fv fragments (low-molecular-weight antibodies that can pass through the glomerulus) are more useful for molecular imaging due to their faster clearance from circulation and more homogeneous tissue distribution.2,3 They can also reduce radiation exposure for the subject. However, radiolabeled antibody constructs cause high and persistent localization of radioactivity in the kidney, hindering target visualization in that area.2,5

To reduce renal radioactivity levels, we conceived a molecular design that liberates a radiolabeled compound via urinary excretion using enzymes present on the brush border membrane (BBM) lining the proximal renal tubule, while the low-molecular-weight antibodies are incorporated into renal cells (renal brush border strategy).6−12 Using this strategy, we recently constructed an S-2-(4-isothiocyanatobenzyl)-1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid (SCN-Bn-NOTA)-conjugated antibody Fab fragment with a Met-Val-Lys linkage (NOTA-MVK-Fab) and gallium-67 (67Ga)-labeled NOTA-MVK-Fab ([67Ga]Ga-NOTA-MVK-Fab). This construct resulted in limited renal radioactivity levels shortly after injection without impairing the radioactivity levels in the tumor due to the release of [67Ga]Ga-NOTA-Met from [67Ga]Ga-NOTA-MVK-Fab by BBM enzymes (Figure 1A).9 This approach can also be applied to gallium-68 (68Ga), a positron emitter. However, the half-life of 68Ga is short (68 min), and radionuclides with a longer half-life would be more useful for immuno-PET.2,3 Therefore, another positron emitter with a longer half-life must be investigated.

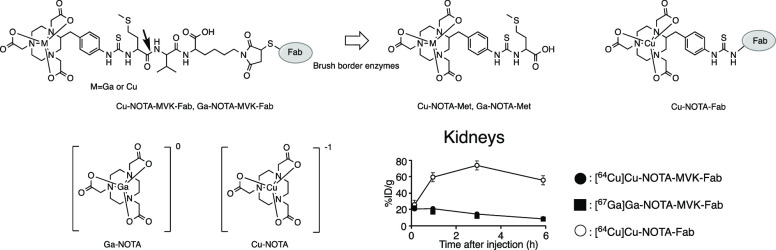

Figure 1.

(A) Chemical structures of M-NOTA-MVK-Fab and M-NOTA-Met (M = Ga or Cu). Ga-NOTA-MVK-Fab liberates Ga-NOTA-Met following the action of renal BBM enzymes. (B) Chemical structures of Ga-NOTA and Cu-NOTA. Ga-NOTA is neutral, but Cu-NOTA is negatively charged.

Copper-64 (64Cu) undergoes β+ decay with a 12.7 h half-life, longer than that of 68Ga, and can provide quality PET images for up to 48 h. Moreover, copper forms a stable metal complex with NOTA.13,14 Therefore, NOTA-MVK-Fab could be applied to 64Cu to produce [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab as an immuno-PET agent. However, the gallium ion has an oxidation state of +3, while that of the copper ion used in nuclear medicine is +2.14 Therefore, the net charge of the Cu-NOTA complex is negative while that of the Ga-NOTA complex is neutral (Figure 1B).14,15 Because the molecular charge might affect enzymatic recognition,16 it is necessary to investigate the applicability of NOTA-MVK-Fab to 64Cu. Thus, this study evaluated the recognition of the MVK sequence in [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab by renal BBM enzymes. A low-molecular-weight model compound, [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK (benzoyl)-OH ([64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo), was synthesized in which the maleimide group in NOTA-MVK-Mal was substituted with a benzoyl group to prevent maleimide-mediated reactions with enzymes. The applicability of NOTA-MVK-Fab to 64Cu was assessed through comparative biodistribution studies of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab in normal and tumor-bearing mice using [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-conjugated Fab fragments with a conventional thiourea linkage and [67Ga]Ga-NOTA-MVK-Fab.

Results and Discussion

64Cu undergoes β+ decay with a 12.7 h half-life and can provide quality PET images for up to 48 h. Thus, the development of 64Cu-labeling agents for antibody fragments based on the brush border strategy would be useful for providing clear tumor images. On the other hand, we have developed radiolabeling agents for antibody fragments based on the brush border strategy using various radionuclides such as 99mTc and 67Ga.6−9,11,12,17 In these studies, altering the radiolabeling moiety changed the enzymatic recognition for the linker structure, which required a modification of the linker structure. The charges of Cu-NOTA and Ga-NOTA were different,14,15 and the molecular charge can affect enzyme recognition. Therefore, we investigated the applicability of NOTA-MVK-Fab to 64Cu.

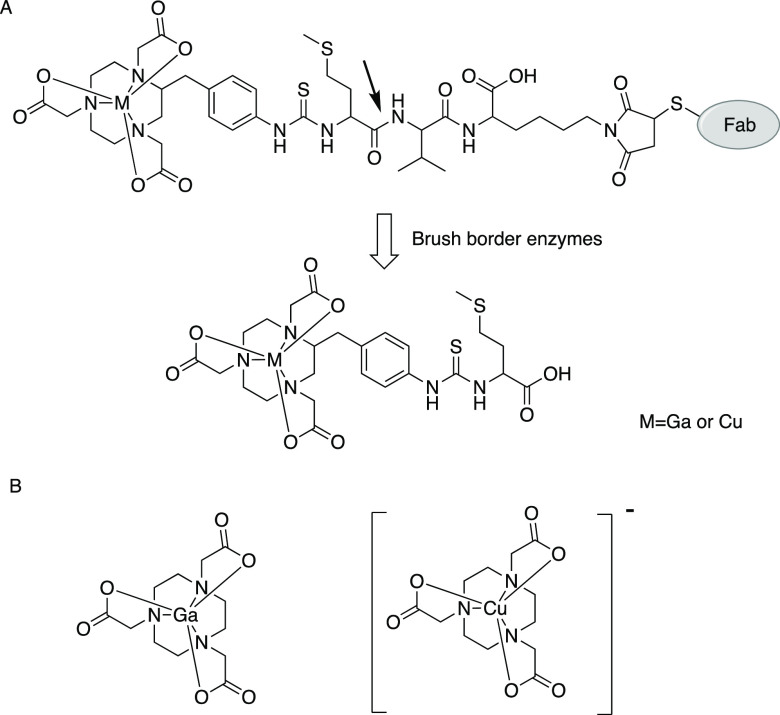

Enzymatic Recognition of the MVK Linkage

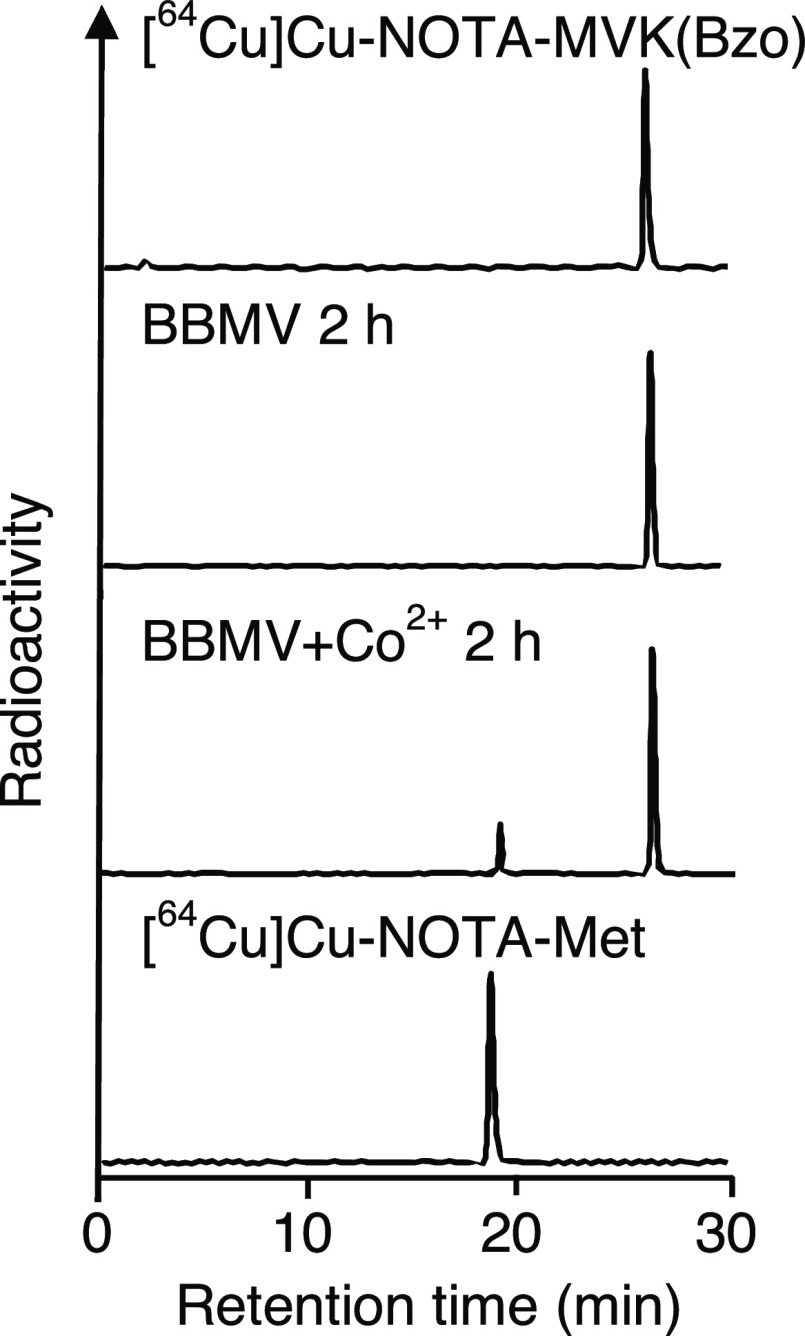

Gallium is found primarily in the +3 oxidation state, while copper forms a wide variety of compounds usually in the +1 and +2 oxidation states. In the field of nuclear medicine, Cu2+ is used; Cu-NOTA has a molecular charge of −1 while Ga-NOTA is neutral (Figure 1B).13,14 Indeed, Cu-NOTA-Met was detected as [M]− in the electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrum, while Ga-NOTA-Met was detected as [M + H]+. Electrostatic forces are involved in a wide variety of molecular interactions, including the interactions between enzymes and their substrates.16 Therefore, the recognition of the MVK sequence in [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo by the BBM enzymes was investigated first. After removing free NOTA-MVK-Bzo by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC), [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo was incubated with brush border membrane vesicles (BBMVs) to estimate the release of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Met. However, [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo barely released [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Met after incubation with BBMVs (Figure 2), while [67Ga]Ga-NOTA-Met was released from [67Ga]Ga-NOTA-MVK-Bzo.9 The negative charge of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo might have inhibited the number of contacts with BBMVs because they were negatively charged.18 Therefore, we re-evaluated the BBM enzyme recognition of the MVK sequence in [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo in the presence of Co2+, which is a well-known enzyme activator.19,20 The incubation of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo with BBMVs in the presence of Co2+ resulted in the cleavage and release of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Met (Figure 2). Therefore, there was a slight recognition of the MVK sequence in [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo by BBM enzymes. The release of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Met from [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo in the presence of Co2+ was inhibited by phosphoramidon, an inhibitor of neutral endopeptidase (NEP) (Figure 3).21 Because the BBM enzymes were activated by Co2+ even in the presence of phosphoramidon (data not shown), these results suggest that NEP was involved in the cleavage of the MVK sequence in [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo. Conversely, in vivo, the MVK sequence in [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab might have gained access to enzymes on the BBM during the uptake of antibody fragments by renal cells, facilitating the cleavage of the MVK sequence. From these hypotheses, although the change of radiometal from Ga3+ to Cu2+ might reduce recognition by NEP, we investigated the applicability of NOTA-MVK-Fab to Cu in vivo.

Figure 2.

Radioactivity profiles of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo after incubation in BBMVs for 2 h without (second from top) and with 1 mM Co2+ (third from top). [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo (top) and [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Met (bottom) are standard samples.

Figure 3.

Formation of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Met metabolites from [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo after incubation with BBMVs and 1 mM Co2+ at 37 °C for 2 h in the absence (control) or presence of an inhibitor of carboxypeptidase (MGTA), angiotensin-converting enzyme (captopril), dipeptidase (cilastatin), or neutral endopeptidase (phosphoramidon). The bars show the means ± SD of three experiments.

Preparation of 64Cu-Labeled Fab Fragments

NOTA-MVK-Mal was conjugated with thiolated Fab fragments using a standard 2-iminothiolane method. The number of NOTA-MVK linkages introduced per molecule of Fab fragments was estimated to be 1.50–2.32 by calculating the number of thiol groups in the Fab fragment before and after the conjugation reaction. NOTA-Fab was also prepared as a reference, and the number of the chelating groups introduced in the Fab fragments was determined to be 2.5. All NOTA-conjugated Fab fragments were labeled with 64Cu in the presence of acetate, and the resulting radiolabeled Fab fragments were analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and size-exclusion high-pressure liquid chromatography (SE-HPLC) (Figure S1). The radiochemical yields and purities of all 64Cu-labeled Fab fragments were over 95%.

Biodistribution Studies in Normal and Tumor-Bearing Mice

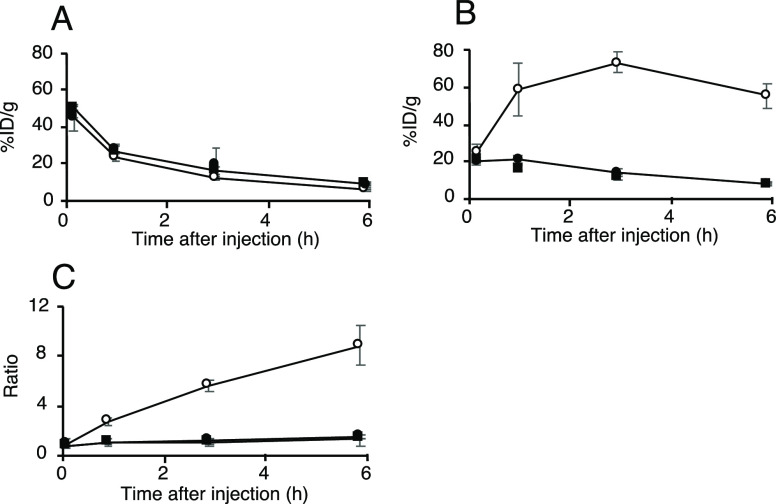

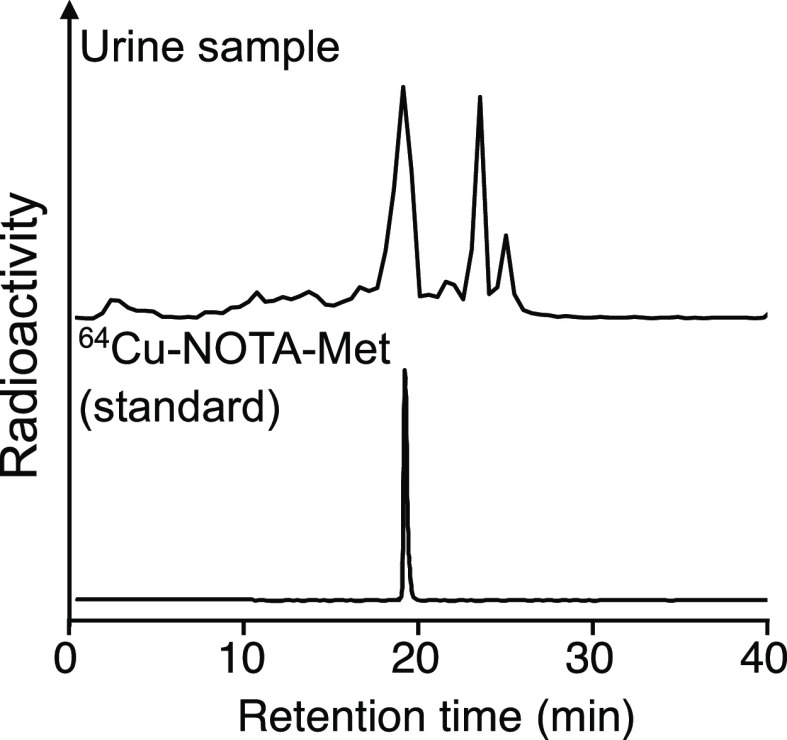

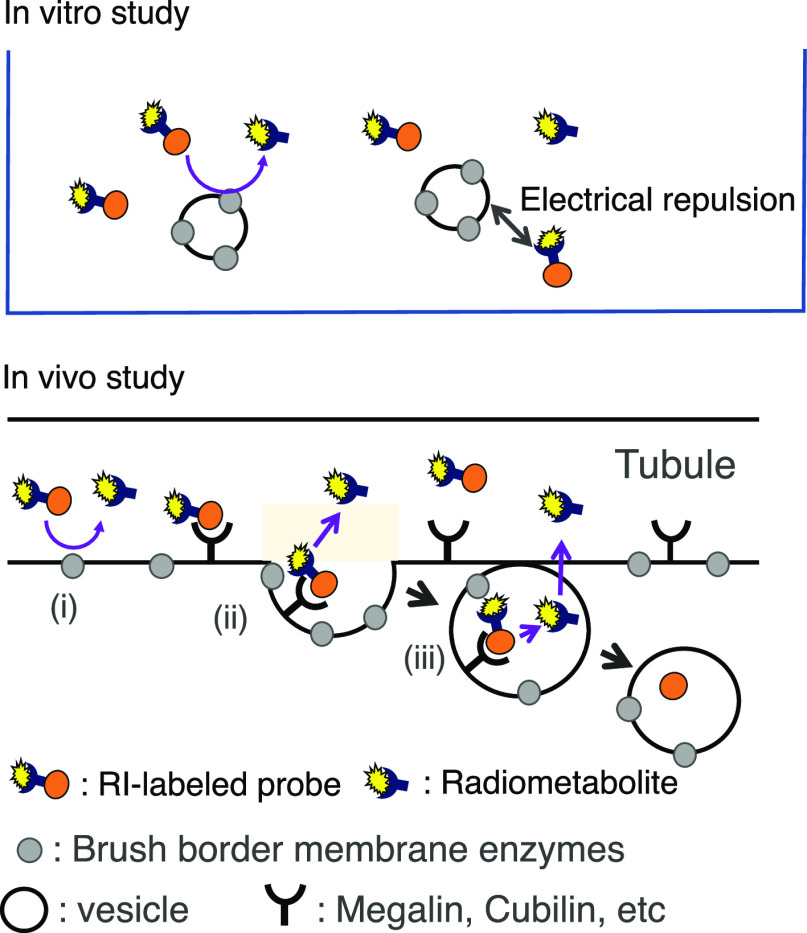

The biodistribution of radioactivity after injection of the 64Cu/67Ga-labeled Fab fragments in normal mice is summarized in Figure 4 and Table S1. When injected into normal mice, both 64Cu-labeled Fab fragments and [67Ga]Ga-NOTA-MVK-Fab showed similar elimination rates of radioactivity from circulation. Thus, similar portions of the three radiolabeled Fab fragments were filtered through the glomerulus and transported to the proximal renal tubules after administration. Indeed, the renal radioactivity levels at 10 min postinjection were similar (Figure 4B). Conversely, the radioactivity levels for [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab in the kidneys were significantly lower than those for [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Fab and similar to those for [67Ga]Ga-NOTA-MVK-Fab from 1 to 6 h postinjection. According to the RP-HPLC analysis of the urine samples collected for 6 h postinjection of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab, the major radiometabolite had a retention time of 19 min, identical to that of the [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Met standard (Figure 5). These results suggest that [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab yielded lower renal radioactivity levels due to the release of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Met by BBM enzymes. Contrary to the results of the in vitro study using BBMVs, the renal radioactivity levels for [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab were similar to those for [64Ga]Ga-NOTA-MVK-Fab (Figure 4), indicating that the recognition of the MVK sequence in [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab in vivo is similar to that of [67Ga]Ga-NOTA-MVK-Fab. Similar results were also observed with [188Re]Re-CpTR-GK-Fab, which yielded low renal radioactivity levels similar to those with [125I]I-HML-Fab, although the in vitro study using BBMVs showed different recognition rates.11 As mentioned above, in the in vitro system using BBMVs, the substrates contact the enzymes on the BBMVs by physical contact (Figure 6). Therefore, it is probable that the negatively charged compound, [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo, would be difficult to contact due to electrostatic repulsion. Thus, it was considered that [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Met could be released efficiently even if the contact time was short because the BBM enzymes were activated by the addition of Co2+. On the other hand, in the analysis using radioiodinated Fab fragment synthesized based on the brush border strategy, radiometabolites were observed in the kidneys even when 10 min after injection, while in the in vitro study, the radiometabolite was analyzed after 2 or 3 h of incubation.9,22,23 Therefore, metabolism by the BBM enzymes in the body would be faster than that of those in the in vitro study. On the other hand, in the analysis using 99mTc-labeling agent based on the brush border strategy, the radiometabolite was released also while internalization.6 From these considerations, [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab appears to liberate [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Met during uptake into renal cells, suggesting [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab might gain better access in vivo to the BBM enzymes. Therefore, the differences in accessibility of substrates to the enzymes between the two experiments might affect enzymatic recognition (Figure 6). These results also suggested that although an in vitro system using BBMVs would be useful to estimate radiolabeling reagents of antibody fragments designed to reduce renal radioactivity levels, the recognition rates of them by the BBM enzymes might be important, but whether they are recognized by the BBM enzymes or not might be more important.

Figure 4.

Time–activity curves of radioactivity in the blood (A) and kidneys (B) and the kidney/blood ratio (C) after injection of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab (solid circle), [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Fab (open circle), and [67Ga]Ga-NOTA-MVK-Fab (solid square) in normal mice.

Figure 5.

Radiochromatograms of urine samples collected for 6 h after injection of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab analyzed by RP-HPLC. The top graph is the urine sample after proteins were removed and the bottom is the [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Met standard sample.

Figure 6.

Proposed differences in the enzymatic recognition for substrates between the in vitro (upper) and in vivo (lower) experiments. In the in vitro system using BBMVs, the substrates contact the enzymes on the BBMVs by physical contact (upper). Therefore, it is probable that the negatively charged compound would be difficult to contact due to electrostatic repulsion. On the other hand, in the in vivo experiments, substrates would not only be cleaved by simple physical contact (i) but also by contact enhanced by the internalizing process such as the formation of coated pits (ii) and coated vesicles (iii) (lower).

In the brush border strategy, the radiometabolite characteristics are also important.6,12,24 Indeed, when [99mTc]Tc-MAG3-Gly was used as a radiometabolite based on the brush border strategy, it was redistributed from the kidneys to the liver and intestine.6 As a result, high radioactivity levels were observed in the liver and intestine although renal radioactivity levels were reduced. In this study, the tissue radioactivity levels after injection of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab were similar to those with [67Ga]Ga-NOTA-MVK-Fab (Figure 4 and Table S1). In addition, the radiochromatograms of urine samples with [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab were similar to those reported previously with [67Ga]Ga-NOTA-MVK-Fab.9 These results suggest that the function of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Met was similar to that of [67Ga]Ga-NOTA-Met, with rapid excretion from the kidneys to urine.25 Therefore, [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Met would be suitable as a radiometabolite based on the brush border strategy.

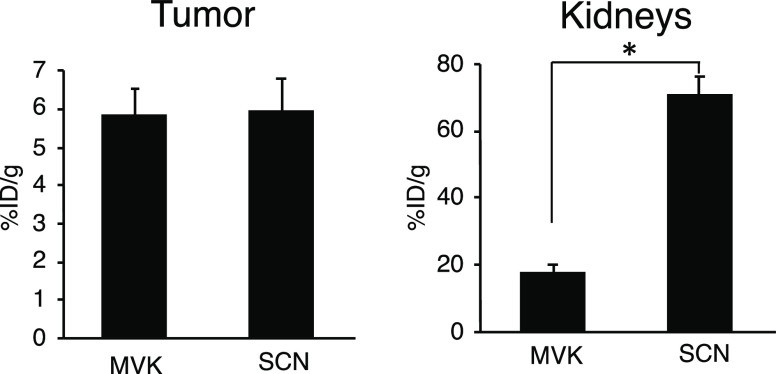

The ability of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab to reduce renal radioactivity levels without impairing the radioactivity levels in the tumor was demonstrated in a biodistribution study in tumor-bearing mice (Figure 7). While no significant differences were observed in tumor uptake between the two 64Cu-labeled Fab fragments at 3 h postinjection, [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab resulted in significantly lower radioactivity levels in the kidneys than [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Fab did. In this study, the antibody Fab fragment was against CD25, which is expressed on T cells such as Treg cells.26 Therefore, some Fab fragments would bind to circulating T cells that expressed CD25 in the blood as indicated by the previous report.27 As a result, both 64Cu-labeled Fab fragments showed slightly higher blood radioactivity levels compared with previously reported results using other Fab fragments.9 Therefore, the tumor/blood ratio was less than 1 (Table S2). Since this depends on the nature of the antibody fragment used in this study, the tumor/blood ratio could improve if appropriate antibody fragments were used. On the other hand, 64Cu undergoes not only β+ but also β– decay, which can be used for radiotherapy.28−30 Therefore, [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab could be used as a radiotheranostic agent. Although the antibody Fab fragment used in this study would not be suitable for radioimmunotherapy due to high hematological toxicity, this labeling procedure could be applied to a variety of antibody constructs of interest. Therefore, other Fab fragments that do not bind to circulating components in the blood would be suitable for radioimmunotherapy.

Figure 7.

Bar graphs showing ID/g of the tumor and kidneys at 3 h postinjection of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab (MVK) and [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Fab (SCN) in tumor-bearing mice (n = 5). The significance was determined using an unpaired Student’s t-test (*: p < 0.05, significantly different from [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-Fab).

Conclusions

This study indicates that the molecular design of NOTA-MVK-Mal developed for a radio-gallium labeling agent can be applied to radio-copper. Because 64Cu undergoes not only β+ but also β– decay, it is used for radiotherapy. This is the first application of a radionuclide that can be used for PET and radiotherapy based on the renal brush border strategy. In addition, copper-67 (67Cu) undergoes β– decay with a half-life of 61.8 h, which is suitable for radiotherapy.28−30 Therefore, [64/67Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab could be used in radiotheranostics. This labeling procedure may be applied to a variety of antibody constructs of interest and used for immuno-PET and radioimmunotherapy.

Experimental Procedures

General

[67Ga]GaCl3 and [64Cu]CuCl2 were purchased from FUJIFILM Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). NOTA-MVK-Bzo, NOTA-MVK-Mal, and the renal BBMVs were prepared as described previously.9,17 The analytical methods are described in the Supporting Information. All commercial chemicals were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

Synthesis of Cu-NOTA-Met

NOTA-Met (3.0 mg, 5 μmol) was added to a solution of nonradioactive CuCl2 (1.0 mg, 7.44 μmol) in 0.25 M acetate buffer (pH 5.5, 50 μL). After stirring for 1 h, Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo was purified by analytical RP-HPLC as a blue solid (0.4 mg, 0.61 μmol, 12.2%). ESI-MS m/z [M]− 659, 661; found 659, 661.

Synthesis of Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo

NOTA-MVK-Bzo (4.0 mg, 4.3 μmol) was added to a solution of nonradioactive CuCl2 (1.0 mg, 7.44 μmol) in 0.25 M acetate buffer (pH 5.5, 50 μL). After stirring for 1 h, Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo was purified by analytical RP-HPLC as a blue solid (0.5 mg, 0.50 μmol, 11.6%). ESI-MS m/z [M]− 990, 992; found 990, 992.

Preparation of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo

A 1.0 μL solution of [64Cu]CuCl2 was mixed with 0.1 M ammonium acetate buffer (pH 5.5, 10 μL). After 5 min, a solution of NOTA-MVK-Bzo (2 × 10–4 M, 10 μL) in 0.1 M ammonium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The radiochemical yield was analyzed by RP-HPLC equipped with an on-line UV/vis detector and a radioactivity detector.

Monoclonal Antibody and Cells

The monoclonal antibody against CD25 (PC-61.53) was purchased from Bio X Cell (Lebanon, NH, USA). The Fab fragments of the anti-CD25 antibody were prepared using a standard procedure using immobilized ficine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Yokohama, Japan). MC38 cells were cultivated in DMEM (Nacalai Tesque Inc., Kyoto, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Nippon Bio-Supply Center, Tokyo, Japan), 2 mM l-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich Japan, Tokyo, Japan), and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (10,000 units/mL and 10,000 μg/mL, Nacalai Tesque Inc.) in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Preparation of 67Ga-Labeled and 64Cu-Labeled Fab Fragments

67Ga-labeled Fab fragments were prepared as previously described.9 For the 64Cu-labeled Fab fragments, 1 μL of [64Cu]CuCl2 solution was added to 0.1 M ammonium acetate buffer (pH 5.5, 10 μL). After 5 min, each NOTA-Fab conjugate (10 μL, 2 mg/mL, 0.1 M ammonium acetate buffer, pH 5.5) was added to the solution, which was gently incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Then, 20 μL of 20 mM EDTA solution was added, and each 64Cu-labeled Fab fragment was purified by a centrifuged column procedure using Sephadex G-50 Fine, equilibrated, and eluted with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS).

Enzymatic Recognition of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo

The enzymatic recognition of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo was determined as previously described.22 A solution of BBMVs (10 μL, 10 mg/mL) was preincubated at 37 °C for 10 min followed by the addition of RP-HPLC-purified [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Bzo (10 μL) in D-PBS. After 2 h of incubation at 37 °C, aliquots of the sample were taken from the solution and analyzed immediately by RP-TLC (0.1 M ammonium acetate/methanol = 1:1). The samples were also treated with ethanol (40 μL) to precipitate proteins, centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 1 min, and analyzed by RP-HPLC. Similar experiments were performed in the presence of an activator (CoCl2) and inhibitors (d,l-mercaptomethyl-3-guanidino-ethylthiopropanoic acid, captopril, cilastatin, and phosphoramidon) of brush border enzymes at a final concentration of 1 mM. All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

In Vivo Study

Animal studies were approved by the Chiba University Animal Care Committee. The number of animals in each group was empirically determined based on prior biodistribution and imaging studies. As such, 3–5 animals were used in each group to allow for statistically significant differences. Separate groups of six-week-old male C57BL/6 J mice (∼25 g, Japan SLC Inc., Shizuoka, Japan) were injected via the tail vein with each of the 67Ga/64Cu-labeled Fab fragments (100 μL, 11.1 kBq, 5 μg). The animals were sacrificed, and the organs were dissected at 10 min, 1 h, 3 h, and 6 h postinjection. Each tissue of interest was excised and weighed, and the radioactivity counts were determined with a gamma well counter. Urine and feces were collected for 6 h postinjection, and the radioactivity counts were determined with a gamma well counter. Each value is expressed as the mean percent injected dose/g of tissue ± SD for a group of 3–5 animals, except for the stomach and intestine.

Five-week-old male C57BL/6 J mice were xenografted in their right hind legs via subcutaneous injection of MC-38 cells suspended in a BD Matrigel (3 × 106 cells). When the tumor reached approximately 10 mm in diameter, these mice were used for in vivo biodistribution studies (body weight ≈ 25 g). Biodistribution studies were conducted using male C57BL/6 J mice bearing MC-38 tumor xenografts at 3 h postinjection of each 64Cu-labeled Fab fragment (100 μL, 11.1 kBq, 5 μg). Tissues of interest were dissected and weighed, and the radioactivity counts were determined using a gamma well counter. Values are expressed as the mean percent injected dose/g of tissue ± SD for a group of five animals.

Analysis of Radiometabolites in Urine

The urine samples were collected from six-week-old C57BL6/J mice for 6 h postinjection of [64Cu]Cu-NOTA-MVK-Fab (100 μL, 222 kBq, 5 μg). The samples were then filtered using a polycarbonate membrane (0.45 μm) and analyzed by SE-HPLC. After the precipitation of proteins with ethanol, the urine samples were analyzed by RP-HPLC using on-line radioactivity detectors.

Statistics

Quantitative data are expressed as means ± SD. Statistical analysis was carried out by comparison using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparison test and Student’s t-test.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B), Grant Numbers JP20H03619.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PET

positron emission tomography

- SPECT

single-photon emission computed tomography

- BBM

brush border membrane

- BBMVs

brush border membrane vesicles

- NEP

neutral endopeptidase.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c02516.

HPLC methods, biodistribution data in normal mice and nude mice bearing MC-38 cells, and SE-HPLC profiles of 64Cu-labeled Fab (PDF)

Author Contributions

H.S. and T.U. conceived and designed the project. H.S. and S.K. prepared the 64Cu/67Ga-labeled compounds and evaluated them both in vivo and in vitro. Y.K., R.W., and T.F. evaluated the 64Cu/67Ga-labeled compounds in vivo. T.S. evaluated 64Cu/67Ga-labeled compounds in vitro. T.F., H.F., and T.U. supervised the project. All authors analyzed and discussed the results and assisted in paper preparation.

JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B), Grant Numbers JP20H03619.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Maloney R.; Buuh Z. Y.; Zhao Y.; Wang R. E. Site-specific antibody fragment conjugates for targeted imaging. Methods Enzymol. 2020, 638, 295–320. 10.1016/bs.mie.2020.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W.; Rosenkrans Z. T.; Liu J.; Huang G.; Luo Q. Y.; Cai W. ImmunoPET: Concept, Design, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 3787–3851. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu R.; Carroll L.; Yahioglu G.; Aboagye E. O.; Miller P. W. Antibody Fragment and Affibody ImmunoPET Imaging Agents: Radiolabelling Strategies and Applications. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 2466–2478. 10.1002/cmdc.201800624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England C. G.; Kamkaew A.; Im H. J.; Valdovinos H. F.; Sun H.; Hernandez R.; Cho S. Y.; Dunphy E. J.; Lee D. S.; Barnhart T. E.; Cai W. ImmunoPET Imaging of Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Receptor in a Subcutaneous Mouse Model of Pancreatic Cancer. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2016, 13, 1958–1966. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akizawa H.; Uehara T.; Arano Y. Renal uptake and metabolism of radiopharmaceuticals derived from peptides and proteins. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2008, 60, 1319–1328. 10.1016/j.addr.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara T.; Kanazawa N.; Suzuki C.; Mizuno Y.; Suzuki H.; Hanaoka H.; Arano Y. Renal Handling of 99mTc-Labeled Antibody Fab Fragments with a Linkage Cleavable by Enzymes on Brush Border Membrane. Bioconjugate Chem. 2020, 31, 2618–2627. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.0c00541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arano Y. Renal brush border strategy: A developing procedure to reduce renal radioactivity levels of radiolabeled polypeptides. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2021, 92, 149–155. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki C.; Uehara T.; Kanazawa N.; Wada S.; Suzuki H.; Arano Y. Preferential Cleavage of a Tripeptide Linkage by Enzymes on Renal Brush Border Membrane To Reduce Renal Radioactivity Levels of Radiolabeled Antibody Fragments. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5257–5268. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara T.; Yokoyama M.; Suzuki H.; Hanaoka H.; Arano Y. A Gallium-67/68-labeled antibody fragment for immuno-SPECT/PET shows low renal radioactivity without loss of tumor uptake. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 3309–3316. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akizawa H.; Imajima M.; Hanaoka H.; Uehara T.; Satake S.; Arano Y. Renal brush border enzyme-cleavable linkages for low renal radioactivity levels of radiolabeled antibody fragments. Bioconjugate Chem. 2013, 24, 291–299. 10.1021/bc300428b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara T.; Koike M.; Nakata H.; Hanaoka H.; Iida Y.; Hashimoto K.; Akizawa H.; Endo K.; Arano Y. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of [188Re]organorhenium-labeled antibody fragments with renal enzyme-cleavable linkage for low renal radioactivity levels. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007, 18, 190–198. 10.1021/bc0602329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arano Y.; Fujioka Y.; Akizawa H.; Ono M.; Uehara T.; Wakisaka K.; Nakayama M.; Sakahara H.; Konishi J.; Saji H. Chemical design of radiolabeled antibody fragments for low renal radioactivity levels. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 128–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price E. W.; Orvig C. Matching chelators to radiometals for radiopharmaceuticals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 260–290. 10.1039/C3CS60304K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadas T. J.; Wong E. H.; Weisman G. R.; Anderson C. J. Coordinating Radiometals of Copper, Gallium, Indium, Yttrium, and Zirconium for PET and SPECT Imaging of Disease. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2858–2902. 10.1021/cr900325h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubíček V.; Böhmová Z.; Ševčíková R.; Vaněk J.; Lubal P.; Poláková Z.; Michalicová R.; Kotek J.; Hermann P. NOTA Complexes with Copper(II) and Divalent Metal Ions: Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 3061–3072. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheinerman F. B.; Norel R.; Honig B. Electrostatic aspects of protein-protein interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000, 10, 153–159. 10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara T.; Rokugawa T.; Kinoshita M.; Nemoto S.; Fransisco Lazaro G. G.; Hanaoka H.; Arano Y. 67/68Ga-labeling agent that liberates 67/68Ga-NOTA-methionine by lysosomal proteolysis of parental low molecular weight polypeptides to reduce renal radioactivity levels. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014, 25, 2038–2045. 10.1021/bc5004058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biber J.; Stieger B.; Stange G.; Murer H. Isolation of renal proximal tubular brush-border membranes. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 1356–1359. 10.1038/nprot.2007.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett B. EPR of Cobalt-Substituted Zinc Enzymes. In Metals in Biology: Applications of High-Resolution EPR to Metalloenzymes. Biol. Magn. Reson. 2010, 29, 345–370. 10.1007/978-1-4419-1139-1_10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deddish P. A.; Skidgel R. A.; Erdös E. G. Enhanced Co2+ activation and inhibitor binding of carboxypeptidase M at low pH. Similarity to carboxypeptidase H (enkephalin convertase). Biochem. J. 1989, 261, 289–291. 10.1042/bj2610289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oefner C.; D’Arcy A.; Hennig M.; Winkler F. K.; Dale G. E. Structure of human neutral endopeptidase (Neprilysin) complexed with phosphoramidon. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 296, 341–349. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka Y.; Satake S.; Uehara T.; Mukai T.; Akizawa H.; Ogawa K.; Saji H.; Endo K.; Arano Y. In vitro system to estimate renal brush border enzyme-mediated cleavage of peptide linkages for designing radiolabeled antibody fragments of low renal radioactivity levels. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005, 16, 1610–1616. 10.1021/bc050211z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka Y.; Arano Y.; Ono M.; Uehara T.; Ogawa K.; Namba S.; Saga T.; Nakamoto Y.; Mukai T.; Konishi J.; Saji H. Renal metabolism of 3′-iodohippuryl Nε-maleoyl-L-lysine (HML)-conjugated fab fragments. Bioconjugate Chem. 2001, 12, 178–185. 10.1021/bc000066j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai S. W.; Li L.; Williams L. E.; Anderson A. L.; Raubitschek A. A.; Shively J. E. Metabolism and renal clearance of 111In-labeled DOTA-conjugated antibody fragments. Bioconjugate Chem. 2001, 12, 264–270. 10.1021/bc0000987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.; Jagoda E.; Brechbiel M.; Webber K. O.; Pastan I.; Gansow O.; Eckelman W. C. Biodistribution and catabolism of Ga-67-labeled anti-Tac dsFv fragment. Bioconjugate Chem. 1997, 8, 365–369. 10.1021/bc970032k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K.; Sato N.; Xu B.; Nakamura Y.; Nagaya T.; Choyke P. L.; Hasegawa Y.; Kobayashi H. Spatially selective depletion of tumor-associated regulatory T cells with near-infrared photoimmunotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 352ra110 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan S.; Liu B.; Zhang C.; Lee K. H.; Sun S.; Wei J. Circulating autoantibody to CD25 may be a potential biomarker for early diagnosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2013, 15, 825–829. 10.1007/s12094-013-1007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T.; Karlsen M.; Karlberg A. M.; Redalen K. R. Hypoxia imaging and theranostic potential of [64Cu][Cu(ATSM)] and ionic Cu(II) salts: a review of current evidence and discussion of the retention mechanisms. EJNMMI Res. 2020, 10, 33. 10.1186/s13550-020-00621-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto H.; Igarashi C.; Kaneko E.; Hashimoto H.; Suzuki H.; Kawamura K.; Zhang M. R.; Higashi T.; Yoshii Y. Process development of [Cu-64]Cu-ATSM: efficient stabilization and sterilization for therapeutic applications. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2019, 322, 467–475. 10.1007/s10967-019-06738-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshii Y.; Furukawa T.; Kiyono Y.; Watanabe R.; Mori T.; Yoshii H.; Asai T.; Okazawa H.; Welch M. J.; Fujibayashi Y. Internal radiotherapy with copper-64-diacetyl-bis (N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) reduces CD133+ highly tumorigenic cells and metastatic ability of mouse colon carcinoma. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2011, 38, 151–157. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.