Abstract

Introduction

Unmet health-related social needs contribute to high patient morbidity and poor population health. A potential solution to improve population health includes the adoption of care delivery models that alleviate unmet needs through screening, referral, and tracking of patients in health care settings, yet the overall impact of such models has remained unexplored. This review addresses an existing gap in the literature regarding the effectiveness of these models and assesses their overall impact on outcomes related to experience of care, population health, and costs.

Methods

In March 2020, we searched for peer-reviewed articles published in PubMed over the past 10 years. Studies were included if they 1) used a screening tool for identifying unmet health-related social needs in a health care setting, 2) referred patients with positive screens to appropriate resources for addressing identified unmet health-related social needs, and 3) reported any outcomes related to patient experience of care, population health, or cost.

Results

Of 1,821 articles identified, 35 met the inclusion criteria. All but 1 study demonstrated a tendency toward high risk of bias. Improved outcomes related to experience of care (eg, change in social needs, patient satisfaction, n = 34), population health (eg, diet quality, blood cholesterol levels, n = 7), and cost (eg, program costs, cost-effectiveness, n = 3) were reported. In some studies (n = 5), improved outcomes were found among participants who received direct referrals or additional assistance with indirect referrals compared with those who received indirect referrals only.

Conclusion

Effective collaborations between health care organizations and community-based organizations are essential to facilitate necessary patient connection to resources for addressing their unmet needs. Although evidence indicated a positive influence of screening and referral programs on outcomes related to experience of care and population health, no definitive conclusions can be made on overall impact because of the potentially high risk of bias in the included studies.

Summary.

What is already known on this topic?

Little is known about the overall impact of screening and referral programs that address unmet health-related social needs on outcomes related to experience of care, population health, and cost.

What is added by this report?

Although screening and referral programs positively affected outcomes related to experience of care and population health, definitive conclusions about their overall impact could not be determined.

What are the implications for public health practice?

This study synthesizes evidence to inform health care administrators and policy makers considering the expansion of screening and referral programs to address unmet health-related social needs.

Introduction

Up to 80% of health outcomes can be attributed to social determinants of health (SDOH), the conditions in which we grow, live, and work (1,2). Adverse SDOH include food insecurity, housing instability, unemployment, and other unmet health-related social needs (3), which often contribute to negative health outcomes, including an increased risk for diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease (4–7). Recently, higher unemployment rates and changes in health insurance coverage due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic have further compromised health care access and increased the number of people with unmet needs (8,9).

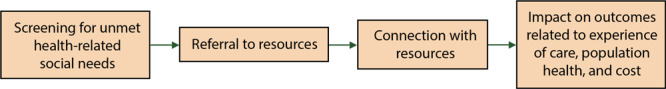

Health care organizations (HCOs) offer a natural setting for integration of clinical care, public health, and community-based services (10,11). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has recognized the potential value in leveraging the infrastructure of HCOs for addressing health-related social needs. As part of the Accountable Health Communities initiative, CMS provides incentives for HCOs to consider solutions that address unmet needs by potentially improving population health and reducing system costs to drive overall performance (12). One common approach to the screening and referral–based care delivery model includes the identification of unmet needs through a screening questionnaire, followed by a referral component that addresses or mitigates unmet needs through referrals to appropriate resources, and subsequently evaluates the impact of this screening and referral program (12–14) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Processes and potential impact on outcomes of screening and referral-based delivery services for addressing unmet health-related social needs among patients in a healthcare setting.

Although implementation of such screening and referral-based programs has increased in recent years (14), we found no review that summarized evidence on the impact of these programs on care outcomes. Therefore, in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (15), we answered the following population, intervention, comparison, and outcomes question (PICO): What is the impact of screening and referral programs targeting unmet health-related social needs in health care settings on outcomes related to experience of care, population health, and costs?

Methods

Data sources

Because CMS only started implementing screening and referral–based care delivery models in 2016 (12), we searched PubMed to identify relevant peer-reviewed articles published over the past 10 years as of March 2020 to capture results from any pilot and demonstration projects before and after this time frame. Search terms were derived with the help of a subject librarian and included the following terms: (“social determinants of health” OR “social determinants” OR “social needs” OR food insecurity OR housing OR transportation OR employment) AND (screening OR needs assessment OR test) AND (referrals OR collaboration OR address needs) AND (“primary care” OR primary health care OR health services) NOT (biological OR psychology OR mental health). Our search terms did not contain an exhaustive list of all social determinants described in the literature. Specific health-related social needs (eg, food insecurity, housing) included in the search indicate the needs commonly addressed by current screening and referral programs. Additionally, we scanned the bibliographies of all articles that met the inclusion criteria and other literature reviews (16,17). To maximize our final article yield, older studies published before January 1, 2010, obtained from bibliographies, were included if they met the inclusion criteria.

Study selection

Articles were included if they were written in English and described an intervention in a health care setting that 1) used a screening tool to identify unmet health-related social needs, 2) referred screened patients with positive results (or positive screens) to resources offering assistance (eg, on-site provision of food or referral to a food bank), and 3) reported any care outcomes resulting from the screening and referral components described in 1) and 2), beginning with program recruitment or referral uptake. After the study selection, all outcomes were categorized into experience of care, population health, and cost-related based on the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Triple Aim framework (18), which targets 3 dimensions for optimizing performance in HCOs: 1) improving the patient experience of care through quality and satisfaction; 2) improving health of the patient population, and 3) reducing the per capita cost of care.

Using the Triple Aim framework as a guideline, outcomes related to the patient experience of care included outcomes resulting from the referral (eg, patient use of resource) and patient-reported outcomes (eg, self-reported changes in social needs, patient satisfaction with the screening and referral intervention). Outcomes related to population health describe any changes in indicators pertaining to patient health (eg, blood pressure trends, diet intake). Cost-related outcomes included any changes in health care costs, utilization, or cost-effectiveness evaluation.

Articles were excluded if the intervention was in a non–health care setting (eg, community settings such as food banks), if the care delivery services focused solely on individual behavior-related determinants (eg, smoking, physical inactivity, alcohol consumption) rather than social determinants, or if the program did not include a screening and/or referral component. Articles were also excluded if we could not ascertain whether on-site screening for health-related social needs was performed or if solely process-related, descriptive screening outcomes (eg, number of screenings, number of referrals) were reported.

Screening of titles and abstracts was carried out by 2 reviewers (E.R.E., S.P.) using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation). Once relevant articles were independently identified, each reviewer completed a full-text review of the selected articles. We planned to resolve discrepancies during the article selection process by using consensus among the authors (E.R.E., S.P., C.B.), but no discrepancies occurred.

Data extraction

From each eligible article, we extracted the following: author name(s), year of publication, place of origin, health care setting(s), target population, study design, sample size, screening tool used, targeted unmet health-related social need(s), referral approach, referral site, outcome(s) assessed, and study results.

Risk of bias assessment and data analysis

Valid and complementary assessment tools for randomized (19) and nonrandomized studies (20) were used to examine risk of bias. For randomized clinical trials, we used the Cochrane tool (19) to make critical assessments (low risk, high risk, and unclear risk) of included studies in 6 domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and “other sources of bias.” For nonrandomized studies, we made similar critical assessments (low risk, high risk, and unclear risk) using the RoBANS tool (Risk of Bias Assessment for Nonrandomized Studies) (20) for a slightly different set of 6 domains: selection of participants, confounding variables, measurement of exposure, blinding of outcomes assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting. For both randomized and nonrandomized studies, the final assessment within and across studies was based on the responses to individual domains.

A qualitative synthesis of results across studies was performed. Meta-analysis was not performed because of heterogeneity in the study populations, interventions, and outcomes of included studies.

Results

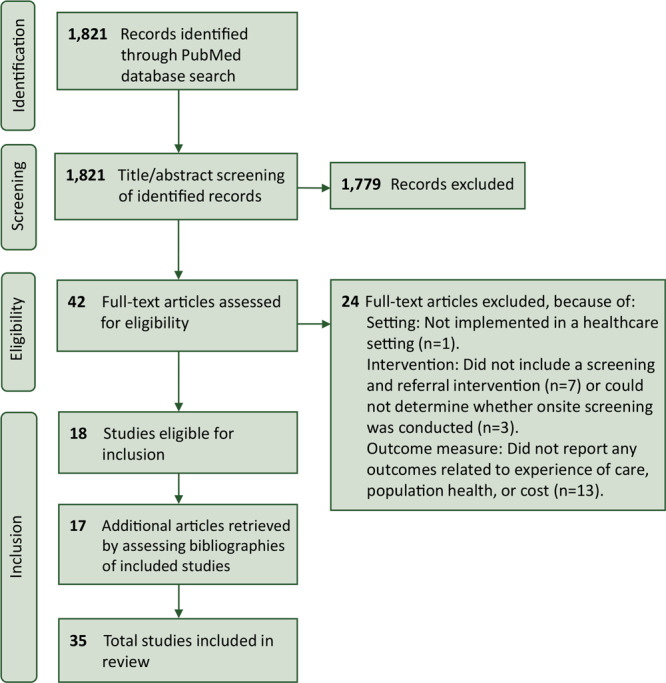

A total of 1,821 articles were identified from the PubMed database search (Figure 2). After applying the PICO question and our inclusion criteria, 42 articles were selected for full-text review, of which 18 met the inclusion criteria. An additional 17 articles were included from bibliographies, bringing the total to 35 articles in the final review. Seven (20%) studies were randomized control trials, 6 (17%) were observational studies that compared outcomes within the intervention group to a nonintervention comparison group, and the rest examined outcomes within an intervention group only (n = 22; 63%).

Figure 2.

PRISMA (Preferred Reported Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) diagram for identification of included studies.

Risk of bias assessment

Randomized studies demonstrated a potentially high risk (n = 6) or unclear risk of bias (n = 1) (Table 1). Insufficient or lack of information about blinding of participants, personnel, or outcomes indicated that potential selection, performance, and detection biases were present. Additionally, all nonrandomized studies (n = 28) were assessed as having a potentially high risk of bias (Table 2). The most common domains demonstrating high risk were blinding of outcomes assessment (n = 28), confounding variables (n = 19), and participant selection (n = 13).

Table 1. Risk of Bias Assessment for Included Randomized Studies, Screening and Referral to Identify Unmet Health-Related Social Needs in Health Care Settings.

| Author, Year (Reference) | Risk of Bias Assessment |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Sequence Generation | Allocation Concealment | Blinding, Participants and Personnel/ Outcomes | Incomplete Outcomes Data | Selective Reporting | Other Sources of Bias | Overall Assessment | |

| Dubowitz H, 2009 (21) | Low | Uncleara | High/High | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Ferrer RL, 2019 (22) | Low | Low | High/High | Low | Low | High | High |

| Garg A, 2015 (23) | Low | Uncleara | Low/Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Gottlieb LM, 2016 (24) | Low | High | High/High | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Haas JS, 2015 (25) | Low | Uncleara | High/Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Sege R, 2015 (26) | Low | Uncleara | High/High | Low | Low | High | High |

| Silverstein M, 2004 (27) | Low | Uncleara | Low/High | Low | Low | Low | High |

Insufficient information provided to determine whether allocation concealment was performed.

Table 2. Risk of Bias Assessment for Included Nonrandomized Studies, Screening and Referral to Identify Unmet Health-Related Social Needs in Health Care Settings.

| Author, Year (Reference) | Risk of Bias Assessment |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant Selection | Confounding Variables | Measurement of Exposure (Referral Service) | Blinding of Outcome Assessments | Incomplete Outcomes/ Loss to Follow-up | Selective Reporting | Overall Assessment | |

| Aiyer JN, 2019 (28) | Low | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Beck AF, 2012 (29) | High | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Beck AF, 2014 (30) | High | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Berkowitz SA, 2017 (31) | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Coker AL, 2012 (32) | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Dicker RA, 2009 (33) | Low | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Dubowitz H, 2012 (34) | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Fiori KP, 2020 (35) | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Fleegler EW, 2007 (36) | High | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Fox CK, 2016 (37) | Low | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Garg A, 2010 (38) | Low | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Garg A, 2012 (39) | Low | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Hassan A, 2015 (40) | Low | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Hsu C, 2019 (41) | High | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Juillard C, 2015 (42) | High | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Klein MD, 2013 (43) | Low | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Krasnoff M, 2002 (44) | Low | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Marpadga S, 2019 (45) | High | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Morales ME, 2016 (46) | High | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Palakshappa D, 2017 (47) | High | Low | Low | High | High | Low | High |

| Patel MR, 2018 (48) | High | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Pettignano R, 2011 (49) | High | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Power-Hays A, 2020 (50) | High | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Schickedanz A, 2019 (51) | High | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Smith R, 2013 (52) | High | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Smith S, 2016 (53) | Low | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Stenmark SH, 2018 (54) | Low | High | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

| Uwemedimo OT, 2018 (55) | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | High |

Settings, populations, and unmet health-related social needs

All included studies (n = 35) had a screening and referral component and originated in the US (Tables 1 and 2). Most screening and referral programs were implemented in pediatric clinics (n = 15) (21,26,29,30,34–37,39,43,47,49,50,54,55) and other primary care practices (n = 11) (22,23,25,27,28,31,32,38,40,41,53); the rest (n = 9) were in other settings (24,33,42,44–46,48,51,52). Included studies defined target populations by health conditions or behavioral risk factors (eg, patients with diabetes, or patients who smoke), and/or demographic characteristics (eg, age, sex).

The social needs addressed included education (eg, poor literacy, health education) (23,24,27,33,38–41,49–52,55), unemployment and income insecurity (eg, vocational training, financial burden) (23,24,26,31,33,36,38–41,43,48–52,55), food insecurity (22–24,26,28,30,31,35–41,43,45–47,49–51,53–55), housing insecurity (eg, poor housing conditions, homelessness) (23,24,26,29,31,35,36,38–41,43,49–52,55), interpersonal safety (eg, intimate partner violence) (21,24,32–36,38,39,43,44,49,55), transportation to health care site (24,31,35,39,41,50,51,55), and others (eg, counseling needs, childcare/eldercare services, access to services) (21,23,24,31–36,38–41,43,49–52,55) (Table 3). Although some programs (n = 13) addressed a single unmet social need (22,27–30,37,44–48,53,54), more than half (n = 21) addressed multiple needs (21,23–26,31–36,38–41,43,49–52,55). One study (42) was a cost-effectiveness analysis of a screening and referral program addressing multiple needs (52).

Table 3. Characteristics of Included Studies, Screening and Referral to Identify Unmet Health-Related Social Needs in Health Care Settings.

| Author, Year; Location (Reference) | Setting; Target Population | Screening Tool and Targeted Unmet Health-Related Social Need | Referral Approach; Referral Site | Study Design, Sample Sizea | Outcome Assessed | Summary of Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience of care outcomes | ||||||

| Smith S, 2016; San Diego, CA (53) | Setting: 3 student-run free clinics. Population: Adults (aged >18 y) | USDA US Household Food Security Survey 30-day version, targeted food insecurity | Approach: Indirect referralb with on-site assistance.c Site: Local food pantries, monthly on-site food distributions, and on-site same-day SNAP enrollment | Cross-sectional study, 1-group design (n = 430) | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | 15% (66 of 430) of total patients used a food pantry. 15% (64 of 430) enrolled in SNAP. 48% (208 of 430) of screened patients had diabetes, of whom 97% (201 of 208) received on-site monthly food boxes |

| Fox CK, 2016; Minnesota (37) | Setting: 1 pediatric weight management clinic. Population: Households with children | Hunger Vital Sign, targeted food insecurity | Approach: Direct referral.e Site: Food bank (Second Harvest Heartland) offered on-site assistance with SNAP application | Prospective pilot study, 1-group design (n = 116) | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | 8% (3 of 40) of eligible patients completed SNAP enrollment process. |

| Palakshappa D, 2017; Pennsylvania (47) | Setting: 6 pediatric clinics. Population: Households with children | Hunger Vital Sign in EHR, targeted food insecurity | Approach: Direct referral.e Site: Nonprofit organization (Benefits Data Trust) assisted with applications to government benefits | Prospective mixed-methods study, 1-group design (n = 4,371) | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | 26% (32 of 122) of patients with food insecurity consented to a direct referral. 3% (1 of 32) of patients enrolled in SNAP. |

| Stenmark SH, 2018; Colorado (54) | Setting: 2 pediatric clinics. Population: Households with children | Hunger Vital Sign, targeted food insecurity | Approach: Indirect referralb evolved into direct referral.e Site: Nonprofit organization (Hunger Free Colorado) offered assistance with applications to federal and community resources | Descriptive, prospective study, 1-group design, number of screened patients not provided; 1,586 patients were referred | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | Connection rate between patients and referral site increased from 5% to 75% after the program moved from indirect to direct referral. 6% (100 of 1,586) of patients enrolled in SNAP. |

| Marpadga S, 2019; San Francisco, CA (45) | Setting: 1 diabetes clinic. Population: Patients with diabetes | Hunger Vital Sign, targeted food insecurity | Approach: Indirect referralb with on-site assistance.c Site: Multiple, including programs that offered free groceries, on-site prepared meals, home-delivered meals, and medically tailored meals (Project Open Hand) | Qualitative study; semistructured interviews, 1-group design (n = 240) | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | 13% (31 of 240) of screened patients were interviewed. 32% (10 of 31) of participants connected with food resources: 3% (1 patient) with a program providing free groceries and 29% (9 patients) with a program providing medically tailored meals. |

| Beck AF, 2012; Cincinnati, OH (29) | Setting: 1 pediatric primary care clinic. Population: Households with children | EHR-based screening, targeted poor housing conditions | Approach: Warm handoff.f Site: On-site medical–legal partnership offered help with legal housing problems | Descriptive, retrospective study, 1-group design, number of screened patients not provided, 16 caregivers referred | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | 71% (10 of 14) of referred housing units with outcome data resulted in housing condition repairs. 58% (11 of 19) of building complexes with the same owner received substantial systemic repairs. |

| Silverstein M, 2004; Seattle, WA (27) | Setting: 4 health clinics. Population: Low-income households with children | Program-developed tool, targeted education | Approach: Intervention: Direct referral.e Control: Indirect referral.b Site: US Department of Health and Human Services program (Head Start) | Randomized controlled trial, intervention (n = 123) vs control (n = 123) | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | Intervention group had more children who connected with the education resource (41%, 50 of 123 vs 18%, 22 of 123; adjusted difference, 17%; 95% CI, 8%–27%) and more children who actively attended the program (25%, 31 of 123 vs 11%, 14 of 123; adjusted difference, 12%; 95% CI, 3%–21%) than the control group. |

| Dicker RA, 2009; San Francisco, CA (33) | Setting: 1 level I trauma center. Population: Patients aged between 12–30 | Screening tool (not specified) targeted risk of reinjury | Approach: Warm handofff. Site: Case management services, including help with court advocacy, driver’s license, educational resources, vocational training, mental health and drug treatment, and more | Program evaluation study, 1-group design, number of screened patients not provided, 44 enrolled | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | 23% of patients with a positive screen for unmet health-related social needs (45 of 195) received full case management services including help with court advocacy, education, vocational training, mental health/drug treatment, employment needs, housing needs, and receiving a driver’s license. |

| Coker AL, 2012; Unknown location (32) | Setting: 6 primary care clinics. Population: Women (aged >18 years) | Program-developed tool (56) targeted intimate partner violence | Approach: Intervention: Indirect referral,b warm handoff,f and on-site assistance.c Control: Indirect referral.b Site: Multiple, including coalition services, safety planning, and on-site counseling and support (intervention group only) | Quasi-experimental, longitudinal cohort study, intervention (n = 138) vs control (n = 93) | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | A similar number of women reported using the referral resource in the intervention and control group (21.4% vs 17.4%; P = .43). More intervention women connected with the on-site advocate (32.8% vs 4.4%; P < .001) and had lower IPV scores and fewer depressive symptoms (P = .07; P = .01) than the control. |

| Klein MD, 2013; Cincinnati, OH (43) | Setting: 3 pediatric clinics. Population: Households with children | EHR-based screening (57) targeted income, child food insecurity, poor housing conditions, domestic violence, parental depression, and anhedonia | Approach: Warm handoff.f Site: On-site medical–legal partnership offered help with legal problems | Descriptive cohort study, number of enrolled participants not provided, 1-group design; 1,614 patients referred | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | 1,617 legal cases were pursued by 1,614 referred families. 90% (1,742 of 1,945) of legal outcomes were positive, including improvements in housing conditions, public benefits, education, or provision of legal advice. 10% (n = 203) related to either inability to reconnect with the family or issue resolution. |

| Uwemedimo OT, 2018; Queens, NY (55) | Setting: 1 hospital-based pediatric practice. Population: Households with children (<18 y) | FAMNEEDS targeted parent counseling and education needs, food insecurity, housing/utility insecurity, interpersonal safety, transportation, unemployment | Approach: Warm handofff before indirect referral.b Site: Unspecified partner CBOs | Pre-post intervention study, 1-group design (n = 148) | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | 31% (46 of 148) of households reported using the program-provided resources at 12-month follow-up. More limited English proficiency caregivers used resources (38.4% vs 18.4%, P = .03) than English-proficient caregivers, and more noncitizen caregivers used referrals (37.4% vs 23.1%, P = .04) than US citizens. |

| Garg A, 2015; Boston, MA (23) | Setting: 8 community health centers. Population: Households with infants (<6 mo) | Program-developed tool targeted parent education needs, childcare needs, food insecurity, housing insecurity, unemployment | Approach: Intervention: Indirect referralb with on-site assistance.c Control: Indirect referral.b Site: Unspecified CBOs | Randomized controlled trial, intervention (n = 168) vs control (n = 168) | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | Intervention mothers were more likely to enroll in a new community resource (39% vs 24%; aOR = 2.1; 95% CI, 1.2–3.7), had greater odds of being employed or enrolled in a job training program (aOR = 44.4; 95% CI, 9.8–201.4), receiving childcare support (aOR = 6.3; 95% CI, 1.5–26.0), fuel assistance (aOR = 11.9; 95% CI, 1.7–82.9), and lower odds of being in a homeless shelter (aOR = 0.2; 95% CI, 0.1–0.9) than mothers in control group. |

| Fiori KP, 2020; Bronx, NY (35) | Setting: 1 pediatric clinic. Population: Households with children | EHR-based Health Leads–adapted tool targeted poor access to health care, childcare and eldercare needs, food insecurity, housing insecurity, interpersonal safety, legal needs, transportation | Approach: Warm handoff.f Site: Unspecified CBOs | Pragmatic prospective cohort study, 1-group design (n = 4,948) | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | 43% (123 of 287) of patients referred to a community health worker had “successful” referrals. These patients either accessed, obtained, or used the recommended community-based service or support. |

| Pettignano R, 2011; Atlanta, GA (49) | Setting: 1 pediatric clinic. Population: Households with children with sickle cell disease | Screening tool (not specified) targeted legal needs associated with child needs (eg, childcare, child abuse), education, health insurance, interpersonal safety, unemployment, food insecurity, housing insecurity, and income insecurity | Approach: Warm handofff to HeLP program with on-site assistance.c Site: On-site medical–legal partnership offered help with legal problems | Descriptive, retrospective cohort study, number of enrolled participants not provided, 1-group design, 69 patients referred | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | 106 legal cases were pursued by 69 referred households. 93% (n = 99) of the cases were closed. 21% (21 of 99) of the closed cases resulted in measurable gain of benefits including obtaining food stamps, Social Security insurance, family stability, employment, and/or housing and education benefits. |

| Garg A, 2012; Baltimore, MD (39) | Setting: 1 pediatric clinic. Population: Households with children | Health Leads targeted education needs, food insecurity, health insurance, housing insecurity, income insecurity, interpersonal safety, transportation needs, unemployment | Approach: Indirect referral.b Site: Unspecified CBOs | Prospective cohort study, 1-group design (n = 1,059) | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | 50% (530 of 1,059) of families enrolled in at least 1 community-based resource within 6 months of accessing the on-site Health Leads desk. |

| Power-Hays A, 2020; Boston, MA (50) | Setting: 1 pediatric hematology clinic. Population: Patients with sickle cell disease | The WE CARE app targeted childcare needs, educational needs, food insecurity, housing insecurity, income insecurity, transportation needs, unemployment | Approach: Indirect referralb or warm handoff.f Site: Unspecified local CBOs | Qualitative quality improvement project, 1-group design (n = 132) | Experience of care (referral uptaked) | 45% (42 of 92) of patients who were referred and available for follow-up reported reaching out to the CBO. |

| Hassan A, 2015; Boston, MA (40) | Setting: 1 adolescent/young adult clinic. Population: Patients aged 15–25 | Program-developed tool targeted access to health care, education needs, food insecurity, housing insecurity, income insecurity, fitness and safety equipment needs, unemployment | Approach: Indirect referral.b Site: Unspecified CBOs | Prospective interventional study, 1-group design (n = 401) | Experience of care (referral uptaked, patient-reported outcomes) | 40% (104 of 259) of patients with a positive screen contacted the referral site of which 50% (52 of 104) had their problem resolved. 60% (155 of 259) did not contact the referral site but 45% (70 of 155) reported having resolved their problem. |

| Krasnoff M, 2002; Unknown location (44) | Setting: 1 level I trauma center. Population: Women aged 18–65 | Partner Violence Screen (58) targeted IPV | Approach: Warm handoff.f Site: On-site case manager and other unspecified community-based resources | Observational case study, 1-group design (n = 528) | Experience of care (referral uptaked, patient-reported outcomes) | 84% (475 of 562) of women with a positive screen consented to meeting with an on-site advocate, of whom 54% (258 of 475) then agreed to meet with a case manager. At follow-up, 24% (127 of the 528) of women reported they no longer believed they were at risk for violence from their abuser. |

| Haas JS, 2015; Boston, MA (25) | Setting(s): 13 primary care clinics. Population: Adults that smoke | Web-based referral system HelpSteps targeted multiple social needs | Approach: Intervention: Direct referrale before indirect referral.b Control: No referral. Site: External specialist (direct referral), unspecified CBOs (indirect referral), and provision of free NRT patches | Randomized clinical trial, intervention (n = 399) vs control (n = 308) | Experience of care (referral uptaked, patient-reported outcomes) | 68.7% (274 of 399) of intervention participants connected with the external tobacco treatment specialist, while 20.1% reported using the HelpSteps referral. Intervention participants who connected with the specialist (21.2% vs 10.4%; P = .009) or used the HelpSteps referral (43.6% vs 15.3%; P < .001) were more likely to quit than those who did not. |

| Hsu C, 2019; San Pablo, CA (41) | Setting: 1 primary care practice. Population: Adults | Health Leads targeted childcare needs, food insecurity, health literacy, housing insecurity, income insecurity, transportation | Approach: Warm handoff.f Site: Unspecified community-based resources | Qualitative study; semistructured interviews, 1-group design (n = 102) | Experience of care (referral uptake, patient-reported outcomes) | Patients reported concrete changes in their lives including healthier diets, decreased stress or worry, and increased feeling of stability; some reported as resolved immediate food, transportation, or health care needs, and others reported physical or mental/emotional benefits. |

| Fleegler EW, 2007; Boston, MA (36) | Setting: 2 pediatric clinics. Population: Households with children aged 0–6 | Program-developed tool targeted poor access to health care, food insecurity, housing insecurity, income insecurity, and intimate partner violence | Approach: Indirect referralb Site: Unspecified local agencies | Cross-sectional descriptive study, 1-group design (n = 450) | Experience of care (referral uptaked, patient satisfaction) | 63% (73 of 115) of referrals received by 79 households led to contact with the referral agency. 82% (60 of the 73) of households considered their referral sites helpful. |

| Garg A, 2010; Baltimore, MD (38) | Setting: 1 medical home. Population: Households with children | WE CARE-based tool targeted child needs (eg, after-school programs, childcare, child school failure), education needs, food insecurity, health insurance, housing insecurity, public benefits needs, income insecurity, IPV, unemployment, safety equipment, and other (eg, smoking, drug or alcohol abuse) | Approach: Warm handoff.f Site: Unspecified CBOs | Longitudinal cohort pilot study, 1-group design (n = 59) | Experience of care (referral uptaked, patient satisfaction) | 32% (19 of 59) of parents that used the on-site Help Desk reported enrolling in at least 1 community program. 21% (4 of the 19) enrolled in ≥2 community programs. More than 90% of parents who enrolled in a community resource were very or somewhat satisfied. |

| Gottlieb LM, 2016; San Francisco and Oakland, CA (24) | Setting: 2 safety-net hospitals. Population: Households with children | 14-item questionnaire targeted needs related to childcare, education, food insecurity, health insurance, housing insecurity, income insecurity, interpersonal safety, legal aid, transportation, unemployment | Approach: Intervention: Warm handoff.f Control: Indirect referral.b Site: Unspecified community, hospital, and government-based resources | Randomized clinical trial, intervention (n = 872) vs control (n = 937) | Experience of care (patient-reported outcomes) | At 4-months postenrollment, intervention participants reported fewer unmet social needs (mean change of −0.39 vs 0.22; P < .001) and greater improvement in their child’s health than control participants (mean change of −0.36 vs 0.12; P < .001). |

| Dubowitz H, 2009; Baltimore, MD (21) | Setting: 1 pediatric clinic. Population: Households with children aged 0–5 | Parent Screening Questionnaire (59) targeted child maltreatment risk factors including parental depression, parental substance abuse, harsh punishment, major parental stress | Approach: Intervention: Indirect referralb and warm handoff,f if needed. Control: No referral. Site: Multiple, including local community resources and on-site social workers | Randomized controlled trial, intervention (n = 308) vs control (n = 250) | Experience of care (patient-reported outcomes) | Postintervention, the intervention group had fewer families that filed child protective services reports (13.3% vs 19.2%; P = .03), and fewer instances of possible medical neglect including nonadherence (4.6% vs 8.4%; P = .05) and delayed immunizations (3.3% vs 9.6%; P = .002) than the control group. Control group had more parent-reported harsh punishment (P = .04). |

| Dubowitz H, 2012; Maryland (34) | Setting: 18 pediatric practices. Population: Mothers with children | Parent Screening Questionnaire (59) targeted child maltreatment risk factors including parental depression, parental substance abuse, harsh punishment, major parental stress | Approach: Intervention: Indirect referralb and warm handofff if needed. Control: No referral. Site: Multiple, including local community resources and on-site social workers | Case-control study; intervention (n = 595) vs control (n = 524) | Experience of care (patient-reported outcomes) | Intervention mothers reported less psychological aggression initially and 12 months later (initial effect size P = .006; 12-month effect size P = .047) and fewer minor physical assaults (initial effect size P = .02; 12-month effect size P = .04) than control. |

| Population health outcomes | ||||||

| Beck AF, 2014, Cincinnati, OH (30) | Setting: 1 pediatric clinic. Population: Households with infant(s) aged <12 months | Hunger Vital Sign targeted food insecurity | Approach: Recipients: Indirect referralb and on-site assistance.c Nonrecipients: No referral. Site: Unspecified CBOs and on-site provision of formula cans | Prospective, difference-in-difference study, recipients (n = 1,042) vs nonrecipients (n = 4,029) | Experience of care (referral uptaked), Health | Experience of care: All recipients were more likely to have been referred to social work (29.2% vs 17.6%; P < .001), or the medical–legal partnership (14.8% vs 5.7%; P < .001) than nonrecipients. Health: By 14 months, recipients versus nonrecipients were more likely to have completed a lead test and developmental screen (both P < .001), and a full set of well-infant visits (42% vs 28.7%; P < .001). |

| Sege R, 2015; Boston, MA (26) | Setting: 1 hospital-based pediatric clinic. Population: Households with newborn aged <10 weeks | Screening tool (not specified) targeted food insecurity, housing insecurity, income insecurity | Approach: Intervention: Warm handoff.f Control: No referral. Site: On-site medical–legal partnership | Randomized controlled trial, intervention (n = 167) vs control (n = 163) | Experience of care (referral uptaked), Health | Experience of care: Intervention versus control showed accelerated access to resources (baseline, 2.8% vs 1.6%; 6 months, 3.2% vs 2.7%; 12 months, 3.7% vs 3.2%; P = .03). Health: Intervention versus control group had more infants that completed their 6-month immunization schedule by age 7 and 8 months (77% vs 63%; P < .005 and 88% vs 78%; P < .01, respectively), more likely to have ≥5 routine preventive care visits by age 1 year (78% vs 67%; P < .01), and less likely to have visited the emergency department by age 6 months (37% vs 50%; P = .021). |

| Patel MR, 2018; Michigan (48) | Setting: 1 endocrinology clinic. Population: Patients with diabetes | Program-developed tool targeted financial burdens | Approach: Indirect referral.b Site: Unspecified local and national resources for financial burden and disease management | 1-group pre–post pilot study (n = 104) | Experience of care (referral uptaked, patient satisfaction), Health | Experience of care: More participants were using low-cost resources at 2-month follow-up compared with baseline, such as online diabetes education (40% vs 29%; P = .05) and assistance programs related to blood glucose supplies (40% vs 16%; P = .03). Participants found the resource tool highly acceptable across 15 indicators (eg, 93% “learned a lot,” 98% “topics relevant”). Health: Fewer patients reported skipping doses of medicines due to cost concerns (4% vs 11%; P = .03) compared with baseline. |

| Smith R, 2013; San Francisco, CA (52) | Setting: 1 hospital. Population: Victims of violent trauma aged 10–30 years | Screening tool (not specified) targeted high risk for reinjury and others, including need for court advocacy, driver’s license, education, employment, family counseling, housing, mental health, vocational/professional training, substance abuse help | Approach: Warm handoff.f Site: Unspecified risk-reduction resources | Retrospective cohort study, 1-group design (n = 141) | Experience of care (referral uptaked), Health | Experience of care: For 6 years of the program, 254 clients received on-site case management services; a total of 617 needs were identified. 70% (430 of 617) of identified needs were met. Health: The violent injury recidivism rate dropped from an initial 16% to 4.5% by the end of the program. |

| Berkowitz SA, 2017; Boston, MA (31) | Setting: 3 primary care practices. Population: Adults with chronic disease | Health Leads targeted access to medications, elder care needs, food insecurity, housing insecurity, income insecurity, transportation needs, unemployment | Approach: Participants: Warm handoff.f Nonparticipants: No referral. Site: Unspecified CBOs and public benefits | Pragmatic difference-in-difference evaluation study, participants (n = 1,021) vs nonparticipants (n = 301) | Experience of care (referral uptaked), Health | Experience of care: 58% (1,021 of 1,774) of patients with a positive screen enrolled in the program and connected with the on-site advocate. 29.7% of reported needs were closed as “successful,” 27.9% as “equipped,” 34.9% as “unsuccessful,” and 7.1% were handled with a rapid resource referral. Health: Participants versus nonparticipants demonstrated greater improvement in blood pressure (SBP differential change −1.2; 95% CI, −2.1 to −0.4; DBP differential change −1.0; 95% CI, −1.5 to −0.5), and LDL-C (differential change −3.7; 95% CI, −6.7 to −0.6), but no change in HbA1c (differential change −0.04%; 95% CI, −0.17% to 0.10%). |

| Morales ME, 2016; Chelsea, MA (46) | Setting: 1 obstetric clinic. Population: Women | Program-developed tool targeted food insecurity | Approach: Recipients: Indirect referralb and on-site assistance.c Nonrecipients: No referral. Site: Food for Families program, which included referral to local food pantries and on-site support with SNAP or WIC enrollment | Retrospective cohort study, 2-group design, recipients (n = 145) vs nonrecipients (n = 145) | Experience of care (referral uptaked), Health | Experience of care: 67% (97 of 145) of women referred to the program enrolled. Health: Recipients demonstrated better blood pressure trends during pregnancy (SBP 0.2015 mm Hg/wk lower; P = .006 and DBP 0.1049 mm Hg/wk lower; P = .02). No blood pressure trend among nonrecipients, and no differences in blood glucose trends between the 2 groups (P = .40). |

| Ferrer RL, 2019; San Antonio, TX (22) | Setting: 1 primary care clinic. Population: Patients with type 2 diabetes | Hunger Vital Sign targeted food insecurity | Approach: Intervention: Warm handoff.f Control: Indirect referral.b Site: Regional food bank | Randomized controlled trial, intervention (n = 19) vs control (n = 24) | Experience of care (patient-reported outcomes), Health | Experience of care: Intervention group received an average of 7.8 food allotments and were visited at home by a community health worker an average of 2.6 times. Health: Intervention versus control demonstrated a greater drop in HbA1c levels (mean difference of −3.09 vs −1.66; P = .01), improved STC-Diet scale (mean differences of 2.47 vs 0.06; P = .001), but no significant BMI difference (mean differences of –0.17 vs 0.84; P = .43). |

| Cost-related outcomes | ||||||

| Aiyer JN, 2019; North Pasadena, TX (28) | Setting: 1 federally qualified health center and 2 school-based clinics. Population: Households with children | Hunger Vital Sign targeted food insecurity | Approach: Indirect referral.b Site: Food prescription to local food pantry | 1-group design, pre–post mixed methods evaluation study, n = 242 | Experience of care (referral uptaked, patient-reported outcomes), Cost-related (program costs) | Experience of care: 71.1% (172 of 242) of referred patients redeemed their prescription at the food pantry. 94.1% (162 of 172) participants reported a decrease in the prevalence of their food insecurity. Cost-related: Program costs was $12.20 per participant per prescription redemption. |

| Schickedanz A, 2019; Southern CA (51) | Setting: 1 health care system. Population: Predicted high-utilizer patients | Health Leads targeted child-related needs, educational needs, food insecurity, housing insecurity, income insecurity, transportation needs, unemployment | Approach: Intervention: Indirect referral.b Control: No referral. Site: Multiple community-based resources including food banks, housing programs, and other agencies | Prospective difference-in-difference study, intervention (n = 7,107) vs control (n = 27,118) | Experience of care (referral uptaked), Cost-related (utilization) | Experience of care: 53% (1,984 of 3,721) of screened participants reported social needs, but only 10% of those connected with resources. Cost-related: Intervention versus control showed 2.2% decline in utilization visits (P = .058) over 1-year postintervention, including emergency department visits, inpatient hospitalizations, and ambulatory visits. Greater declines in total utilization for all low-socioeconomic status subgroups in intervention versus control (P < .001). |

| Juillard C, 2015; San Francisco, CA (42) | Refer to Smith R, 2013 (52) | Refer to Smith R, 2013 (52) | Refer to Smith R, 2013 (52) | Cost-effectiveness analysis of Smith R, 2013 (52) | Cost-related (cost effectiveness and cost savings) | Cost-related: Realized substantial health benefits (24 QALYs) and savings ($4,100) if implemented for 100 people. |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CBO, community-based organization; DBP, diastolic blood pressure in mm Hg; EHR, electronic health record; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; FAMNEEDS, Family Needs Screening Program; HeLP Program, Health Law Partnership; IPV, intimate partner violence; KIND, Keeping Infants Nourished and Developing; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in mg/dL; NRT, nicotine replacement therapy; QALYs, quality-adjusted life years; SBP, systolic blood pressure in mmHg; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; USDA US HFSS, US Department of Agriculture US Household Food Security Survey; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Reported as the total number of participants who underwent screening. If the study did not report number of screenings, the number of referrals was reported as the sample size.

A referral approach in which health care providers simply hand over information about relevant referral sites to the patient (eg, a list of local food banks and their contact information).

Additional on-site services may include assistance with applying to community-based resources or connection to other resources through a helpdesk, and/or on-site provision of supplies.

Refers to participants who connected to necessary resources expressed as a percentage or ratio of all participants who had a positive screen or those who consented to a referral.

A referral approach that requires the patient’s consent to forward their contact information to the corresponding internal or external resource. The referral site then directly contacts the patient.

A referral approach in which patients are introduced to an on-site intermediary person in the health care organization (eg, community health worker, case manager) who works to connect them to referral sites.

Screening component

The programs described in the included studies employed various screening tools (eg, the Hunger Vital Sign [https://childrenshealthwatch.org/public-policy/hunger-vital-sign/], Health Leads [https://healthleadsusa.org/]) to identify unmet need(s). Most studies (n = 19) (21,22,25,28,30,31,34,35,37–39,41,44,45,47,50,51,53,54) either used tools that had been previously validated in existing literature (60,61) or used tools developed in-house (n = 11) (23,24,27,29,32,36,40,43,46,48,55). Other studies (n = 4) (26,33,49,52) did not specify a screening tool.

Screening assessments were facilitated by clinic staff (n = 9) (21,28,34,35,37,41,46,50,54), health care providers (n = 6) (23,30,31,39,47,49), and others (n = 7) (33,38,43,45,46,50,55). Some assessments (n = 4) were administered to patients online (25,27,36,40).

Referral component

Studies featured HCOs that partnered with various community-based organizations (CBOs) or expanded their internal resources to include assistance programs that addressed immediate unmet needs. Five studies reported on providing on-site social assistance services including CBO eligibility applications (32,45,49,53) and distribution of food supplies (30,53). Although descriptions of community collaboration were sparse, referral sites included CBOs such as food banks, nutrition programs, intimate partner violence agencies, housing programs, and early childhood education programs.

Additionally, we found 3 referral approaches: indirect, direct, and warm handoff. In an indirect referral, health care providers simply hand over information about the referral site(s) to the patient (eg, distribute a list of local food banks and their contact information to patients who have a positive screen for food insecurity). A direct referral approach is when the HCO directly forwards a patient’s contact information to a referral site contingent on the patient’s consent and is often administered through health information exchange tools. The referral site then follows up with the patient to assist in the patient’s application or enrollment in programs to alleviate unmet needs. A warm handoff is when an on-site intermediary person in the HCO (eg, community health worker, social worker) assists patients who have a positive screen with connecting to the referral site.

Indirect referrals and warm handoffs were the most common referral approaches (n = 29) reported (21–24,26,28–36,38–41,43–46,48–53,55). The rest (n = 5) were studies that reported direct referrals (25,27,37,47,54). Studies with 2 groups either compared outcomes in the intervention group to a control group that received no referral (n = 8) (21,25,26,30,31,34,46,51) or to a control group that received a different type of referral (n = 5) (22–24,27,32).

Qualitative synthesis of outcomes

Most studies (n = 25) (21,23–25,27,29,32–41,43–45,47,49,50,53–55) reported only outcomes related to experience of care (Table 3), which included referral uptake (ie, participants who connected with or used necessary resources expressed as a percentage or ratio of all participants who had a positive screen or consented to a referral) and patient-reported outcomes (ie, self-reported changes in social needs, diet, health, and patient satisfaction). Other studies reported population health outcomes (n = 7) (22,26,30,31,46,48,52), which included changes in indicators of patient health such as systolic and diastolic blood pressure, glycosylated hemoglobin levels (HbA1c), body mass index (BMI), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, medication adherence, appointment adherence, violent injury recidivism rates, and preventive care outcomes (ie, completing lead tests, developmental screens, infant immunization schedules, or well-infant visit sets). Only 3 studies reported cost-related outcomes (28,42,51), including evaluation of program costs, changes in health care utilization, or cost-effectiveness.

Experience of care outcomes

Referral uptake. Data on participants or participating families who connected with or used necessary resources were expressed either as a percentage of all participants who had a positive screen or as a percentage of those who consented to/received a referral (referral uptake). Although most studies (n = 30) reported some information on patient connection to the referral site, the reported results were highly contextual and varied widely from study to study. For example, some studies reported connection rates as low as 3% (47) while others reported rates as high as 75% (54).

Patient-reported outcomes. Nine studies (21,24,28,36,38,40,41,44,48) reported positive findings on patient-reported outcomes. For example, 1 study interviewing patients with unmet needs (41) reported participants being able to make concrete changes in their lives as a result of screening and referral, including resolving immediate social needs, a healthier diet, or physical and mental/emotional benefits; another study (28) found that participants’ self-reported food insecurity decreased by 94.1%.

Three studies (36,38,48) that investigated patient satisfaction reported positive feedback on referral sites and program tools. More than 80% of patients found their referral sites helpful in 1 study (36), and more than 90% of parents enrolled in a community-based resource reported being “very” or “somewhat” satisfied in a different study (38). Similarly, participants with diabetes in another study reported high acceptability across multiple survey items in their program’s resource tool (eg, 93% “learned a lot,” 98% found “topics relevant”) (48).

Health outcomes

Seven (22,26,30,31,46,48,52) studies that examined outcomes related to population health found some positive changes in health indicators. After addressing income insecurity, 7% fewer patients (P = .03) reported skipping doses of medicines because of financial concerns (48). Another study found a drop in the violent injury recidivism rate from an initial 16% to 4.5% by the end of the program (52). Other studies found improved preventive care outcomes, including faster completion of lead tests, developmental screens, infant immunization schedules among participants (77% vs 63% completed by age 7 months, P = .002 and 88% vs 78% by age 8 months, P = .008) (26), and greater likelihood of completing a full set of well-infant visits by 14 months (42% vs 28.7%; P < .001) (30). Changes reported in intervention participants enrolled in screening and referral programs compared with those who did not receive a referral included improvements in systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure trends during pregnancy (46) (P = .004), and a modest differential change in systolic blood pressure of −1.2 mm Hg (95% CI, −2.1 to −0.4), diastolic blood pressure of −1.0 mm Hg (95% CI, −1.5 to −0.5), and improved low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (differential change −3.7 mg/dL; 95% CI, −6.7 to −0.6) among participants with diabetes (31).

Cost-related outcomes

Only 3 studies examined cost-related outcomes. One study targeting food insecurity with a food prescription program (28) found program costs to be $12.20 per person per redemption. Additionally, participants reported an average $57 savings per week on grocery bills. Another study targeting multiple social needs (51) reported a decreased likelihood of health care utilization among the intervention group compared with the control group. Also, a cost-effectiveness study (42) of a hospital-based violent injury prevention intervention (52) yielded 25.6 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs, a standardized measure of disease burden in cost-effectiveness evaluations that typically combines both survival and health-related quality of life to guide decisions on the distribution of limited health care resources) versus 25.3 for the non violent injury prevention group, with net costs of $5,892 per patient versus $5,923 for the non violent injury prevention group.

Impact of referral approach on all outcomes

Studies comparing direct (27,54) to indirect referral reported greater referral uptakes with direct referral. One study (27) found that intervention participants receiving direct referrals reported a greater percentage of children who connected with an education resource (41% vs 18%) and actively attended the development program (25% vs 11%) than intervention participants who received an indirect referral. Another study (54) reported patient connection to referral sites increasing from 5% to 75% when the approach was changed from indirect to direct referral.

Some studies compared indirect referrals paired with additional services (eg, on-site assistance) in the intervention to a control group that received indirect referrals only. One such study (32) found a similar percentage of participants using the referral resource (21.4% vs 17.4%; P = .43) as the control group. However, a greater percentage of intervention participants than control participants connected with the on-site advocate (32.8% vs 4.4%; P < .001). Similarly, another study (23) reported that intervention participants had greater odds than control participants of being employed or enrolled in a job training program (aOR = 44.4), receiving childcare support (aOR = 6.3) and fuel assistance (aOR = 11.9), and lower odds of being in a homeless shelter (aOR = 0.2).

Two studies (22,24) compared outcomes in patients receiving a warm handoff with patients who received an indirect referral. The intervention group receiving warm handoff (22) had decreased HbA1c levels (mean differences of −3.09 vs −1.66; P = .012), improved STC (Starting the Conversation)-Diet scale (62) (mean differences of 2.47 vs 0.06; P = .001), but no difference in BMI (mean differences of –0.17 vs 0.84; P = .43) compared with control participants. Similarly, intervention participants in another study (24) reported fewer unmet social needs (mean change of −0.39 vs 0.22; P < .001) and greater improvement in their child’s health than control participants (mean change of −0.36 vs 0.12; P < .001).

Discussion

The body of evidence on the relationship between unmet health-related social needs and poor patient outcomes has continued to grow in recent years. In response, screening and referral programs have expanded to mitigate unmet health-related social needs among patients in health care settings (12,14).

This review found 35 studies on screening and referral delivery services that reported outcomes related to patients’ experience of care, population health, and cost. The delivery service targeted patients with different chronic conditions and demographic characteristics, aiming to mitigate different health-related unmet needs.

We found some indication that screening and referral programs had a generally positive impact on outcomes related to experience of care, population health, and cost. Patient connection to referral sites and patient-reported outcomes such as self-reported diet intake, resolution of unmet health-related social needs, overall well-being, and patient satisfaction increased. Indicators of health such as blood pressure trends, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and medication adherence improved. Additionally, results indicated an improvement in QALYs, decreased likelihood of health care utilization, and modest savings associated with these programs.

Overall, included studies revealed a high risk of bias for elements related to study design and evaluation. Thus, we were unable to draw any definitive conclusions about the impact of screening and delivery services on any outcome.

The linkage of patients to resources seemed to be influenced by the type of referral and the degree of navigation within the HCOs and collaboration between the HCOs and the CBOs involved. Results suggested that patients were more successful in connecting with resources when partnered CBOs are more directly involved (ie, direct referral), or if referral efforts were made through on-site intermediaries such as community health workers to direct patients in contacting or applying to referral sites (ie, warm handoff).

Studies have indicated (37,41,47) that referral uptake was influenced by accessibility to referral sites, including patient eligibility criteria and intensity of time and labor required to access resources. For instance, the application process for SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) is lengthy and complex (63). Such barriers, as speculated in the literature (64), can explain why, despite participating in screening and referral programs, patients can have difficulties in accessing some resources. In short, the degree of referral uptake can be subject to various program characteristics including referral approach, on-site assistance, and accessibility of referral sites.

This review serves as a call to action for policy makers, advocates, and care providers to facilitate screening and referral delivery services through strong collaborations among health care, public health, and community sectors to address unmet health-related and social needs. Such programs can offer a comprehensive solution for health care administrators and insurers looking to improve the health of their patient population, reduce system costs, and optimize overall performance by addressing social determinants of health in their patient populations and delivering high-quality person-centered care. Research with stronger study designs and rigorous evaluation methodologies is needed to establish a strong evidence base of the effectiveness of screening and referral delivery services. Future studies can further explore social-needs screening in mental/behavioral health settings that target individual behavior-related determinants of health (eg, smoking, alcohol abuse) along with social determinants.

To our knowledge, this review is the first study to provide an overview of the impact of screening and referral programs on outcomes related to experience of patient care, population health, and costs. Although our search for articles was performed in accordance with PRISMA guidelines for a systematic review (15), our study was exploratory. We limited our search to peer-reviewed articles and 1 database, which might have excluded other results reported in the gray literature or in other databases.

In summary, literature on the impact of screening and referral programs in HCOs had a tendency toward high risk of bias. Although the evidence indicated promising changes in patient connection to resources, patient-reported outcomes, patient satisfaction, and some health indicators, no definitive conclusions could be made about the impact of such programs on outcomes related to experience of care, population health, and cost. This study can inform public health professionals, administrators, and policy makers about the impact of implementing screening and referral care delivery services in health care settings, paving the way for the expansion of such programs to improve population health.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rebecca Carlson, MLS, AHIP, from the UNC Health Sciences Library for her consultation on designing terms for the literature search. The authors did not receive any funding for conducting this systematic review and report no conflict of interest. No copyrighted materials or tools were used in this work.

Footnotes

The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions.

Suggested citation for this article: Ruiz Escobar E, Pathak S, Blanchard CM. Screening and Referral Care Delivery Services and Unmet Health-Related Social Needs: A Systematic Review. Prev Chronic Dis 2021;18:200569. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.200569.

References

- 1. Magnan S. Social determinants of health 101 for health care: five plus five. National Academy of Medicine. 2017. https://nam.edu/social-determinants-of-health-101-for-health-care-five-plus-five. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- 2. Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, Catlin BB. County Health Rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med 2016;50(2):129–35. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Social determinants of health. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/socialdeterminants/faq.html#addressing-role. Accessed June 16, 2020.

- 4. Berkowitz SA, Hulberg AC, Hong C, Stowell BJ, Tirozzi KJ, Traore CY, et al. Addressing basic resource needs to improve primary care quality: a community collaboration programme. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25(3):164–72. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. How does employment, or unemployment, affect health? Health Policy Snapshot Series. 2013. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2012/12/how-does-employment--or-unemployment--affect-health-.html. Accessed August 24, 2020.

- 6.Healthy People 2020. Social determinants of health/economic stability/unemployment. 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions-resources/employment#7. Accessed August 24, 2020.

- 7. Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(11):1830–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galloway, G. The impact of COVID-19 on SDoH. Healthify. Published March 31, 2020. https://www.healthify.us/healthify-insights/sdoh-impact-of-covid-19. Accessed August 24, 2020.

- 9. American Hospital Association. COVID-19: addressing patients’ social needs can help reduce health inequity during COVID-19. 2020. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/04/awareness-of-social-needs-can-help address-health-inequity-during-covid-19.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2020.

- 10. Shim R, Rust G. Primary care, behavioral health, and public health: partners in reducing mental health stigma. Am J Public Health 2013;103(5):774–6. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krist AH, Shenson D, Woolf SH, Bradley C, Liaw WR, Rothemich SF, et al. Clinical and community delivery systems for preventive care: an integration framework. Am J Prev Med 2013;45(4):508–16. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accountable Health Communities (AHC) model evaluation. 2020. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/ahcm. Accessed February 15, 2021.

- 13. Gurewich D, Garg A, Kressin NR. Addressing social determinants of health within healthcare delivery systems: a framework to ground and inform health outcomes. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35(5):1571–5. 10.1007/s11606-020-05720-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guyer J, Boozang P, Nabet B. Addressing social factors that affect health: emerging trends and leading edge practices in Medicaid. 2019. https://www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Social-Factors-That-Affect-Health_Final.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2020.

- 15. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6(7):e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gottlieb LM, Wing H, Adler NE. A systematic review of interventions on patients’ social and economic needs. Am J Prev Med 2017;53(5):719–29. 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carter N, Valaitis RK, Lam A, Feather J, Nicholl J, Cleghorn L. Navigation delivery models and roles of navigators in primary care: a scoping literature review. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18(1):96. 10.1186/s12913-018-2889-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. IHI Triple Aim Initiative. http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed November 16, 2020.

- 19. Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/10027964982/en/. Accessed March 7, 2021.

- 20. Kim SY, Park JE, Lee YJ, Seo H-J, Sheen S-S, Hahn S, et al. Testing a tool for assessing the risk of bias for nonrandomized studies showed moderate reliability and promising validity. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66(4):408–14. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, Kim J. Pediatric primary care to help prevent child maltreatment: the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) Model. Pediatrics 2009;123(3):858–64. 10.1542/peds.2008-1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ferrer RL, Neira L-M, De Leon Garcia GL, Cuellar K, Rodriguez J. Primary care and food bank collaboration to address food insecurity: a pilot randomized trial. Nutr Metab Insights 2019;12:1178638819866434. 10.1177/1178638819866434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics 2015;135(2):e296–304. 10.1542/peds.2014-2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gottlieb LM, Hessler D, Long D, Laves E, Burns AR, Amaya A, et al. Effects of social needs screening and in-person service navigation on child health: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170(11):e162521. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haas JS, Linder JA, Park ER, Gonzalez I, Rigotti NA, Klinger EV, et al. Proactive tobacco cessation outreach to smokers of low socioeconomic status: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(2):218–26. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sege R, Preer G, Morton SJ, Cabral H, Morakinyo O, Lee V, et al. Medical-legal strategies to improve infant health care: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2015;136(1):97–106. 10.1542/peds.2014-2955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Silverstein M, Mack C, Reavis N, Koepsell TD, Gross GS, Grossman DC. Effect of a clinic-based referral system to head start: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;292(8):968–71. 10.1001/jama.292.8.968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aiyer JN, Raber M, Bello RS, Brewster A, Caballero E, Chennisi C, et al. A pilot food prescription program promotes produce intake and decreases food insecurity. Transl Behav Med 2019;9(5):922–30. 10.1093/tbm/ibz112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Beck AF, Klein MD, Schaffzin JK, Tallent V, Gillam M, Kahn RS. Identifying and treating a substandard housing cluster using a medical-legal partnership. Pediatrics 2012;130(5):831–8. 10.1542/peds.2012-0769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beck AF, Henize AW, Kahn RS, Reiber KL, Young JJ, Klein MD. Forging a pediatric primary care-community partnership to support food-insecure families. Pediatrics 2014;134(2):e564–71. 10.1542/peds.2013-3845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Berkowitz SA, Hulberg AC, Standish S, Reznor G, Atlas SJ. Addressing unmet basic resource needs as part of chronic cardiometabolic disease management. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177(2):244–52. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Coker AL, Smith PH, Whitaker DJ, Le B, Crawford TN, Flerx VC. Effect of an in-clinic IPV advocate intervention to increase help seeking, reduce violence, and improve well-being. Violence Against Women 2012;18(1):118–31. 10.1177/1077801212437908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dicker RA, Jaeger S, Knudson MM, Mackersie RC, Morabito DJ, Antezana J, et al. Where do we go from here? Interim analysis to forge ahead in violence prevention. J Trauma 2009;67(6):1169–75. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181bdb78a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dubowitz H, Lane WG, Semiatin JN, Magder LS. The SEEK model of pediatric primary care: can child maltreatment be prevented in a low-risk population? Acad Pediatr 2012;12(4):259–68. 10.1016/j.acap.2012.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fiori KP, Rehm CD, Sanderson D, Braganza S, Parsons A, Chodon T, et al. Integrating social needs screening and community health workers in primary care: the Community Linkage to Care Program. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2020;59(6):547–56. 10.1177/0009922820908589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fleegler EW, Lieu TA, Wise PH, Muret-Wagstaff S. Families’ health-related social problems and missed referral opportunities. Pediatrics 2007;119(6):e1332–41. 10.1542/peds.2006-1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fox CK, Cairns N, Sunni M, Turnberg GL, Gross AC. Addressing food insecurity in a pediatric weight management clinic: a pilot intervention. J Pediatr Health Care 2016;30(5):e11–5. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Garg A, Sarkar S, Marino M, Onie R, Solomon BS. Linking urban families to community resources in the context of pediatric primary care. Patient Educ Couns 2010;79(2):251–4. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Garg A, Marino M, Vikani AR, Solomon BS. Addressing families’ unmet social needs within pediatric primary care: the health leads model. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012;51(12):1191–3. 10.1177/0009922812437930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hassan A, Scherer EA, Pikcilingis A, Krull E, McNickles L, Marmon G, et al. Improving social determinants of health: effectiveness of a web-based intervention. Am J Prev Med 2015;49(6):822–31. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hsu C, Cruz S, Placzek H, Chapdelaine M, Levin S, Gutierrez F, et al. Patient perspectives on addressing social needs in primary care using a screening and resource referral intervention. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35(2):481–9. 10.1007/s11606-019-05397-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Juillard C, Smith R, Anaya N, Garcia A, Kahn JG, Dicker RA. Saving lives and saving money: hospital-based violence intervention is cost-effective. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;78(2):252–7, discussion 257–8. 10.1097/TA.0000000000000527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klein MD, Beck AF, Henize AW, Parrish DS, Fink EE, Kahn RS. Doctors and lawyers collaborating to HeLP children—outcomes from a successful partnership between professions. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2013;24(3):1063–73. 10.1353/hpu.2013.0147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Krasnoff M, Moscati R. Domestic violence screening and referral can be effective. Ann Emerg Med 2002;40(5):485–92. 10.1067/mem.2002.128872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Marpadga S, Fernandez A, Leung J, Tang A, Seligman H, Murphy EJ. Challenges and successes with food resource referrals for food-insecure patients with diabetes. Perm J 2019;23:18–097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Morales ME, Epstein MH, Marable DE, Oo SA, Berkowitz SA. Food insecurity and cardiovascular health in pregnant women: results from the Food for Families Program, Chelsea, Massachusetts, 2013–2015. Prev Chronic Dis 2016;13(11):E152. 10.5888/pcd13.160212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Palakshappa D, Vasan A, Khan S, Seifu L, Feudtner C, Fiks AG. Clinicians’ perceptions of screening for food insecurity in suburban pediatric practice. Pediatrics 2017;140(1):e20170319. 10.1542/peds.2017-0319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Patel MR, Resnicow K, Lang I, Kraus K, Heisler M. Solutions to address diabetes-related financial burden and cost-related nonadherence: results from a pilot study. Health Educ Behav 2018;45(1):101–11. 10.1177/1090198117704683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pettignano R, Caley SB, Bliss LR. Medical-legal partnership: impact on patients with sickle cell disease. Pediatrics 2011;128(6):e1482–8. 10.1542/peds.2011-0082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Power-Hays A, Li S, Mensah A, Sobota A. Universal screening for social determinants of health in pediatric sickle cell disease: a quality-improvement initiative. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2020;67(1):e28006. 10.1002/pbc.28006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schickedanz A, Sharp A, Hu YR, Shah NR, Adams JL, Francis D, et al. Impact of social needs navigation on utilization among high utilizers in a large integrated health system: a quasi-experimental study. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34(11):2382–9. 10.1007/s11606-019-05123-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Smith R, Dobbins S, Evans A, Balhotra K, Dicker RA. Hospital-based violence intervention: risk reduction resources that are essential for success. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;74(4):976–80, discussion 980–2. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31828586c9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Smith S, Malinak D, Chang J, Perez M, Perez S, Settlecowski E, et al. Implementation of a food insecurity screening and referral program in student-run free clinics in San Diego, California. Prev Med Rep 2016;5:134–9. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Stenmark SH, Steiner JF, Marpadga S, Debor M, Underhill K, Seligman H. Lessons learned from implementation of the Food Insecurity Screening and Referral Program at Kaiser Permanente Colorado. Perm J 2018;22:18–093. 10.7812/TPP/18-093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Uwemedimo OT, May H. Disparities in utilization of social determinants of health referrals among children in immigrant families. Front Pediatr 2018;6:207. 10.3389/fped.2018.00207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Coker AL, Flerx VC, Smith PH, Whitaker DJ, Fadden MK, Williams M. Partner violence screening in rural health care clinics. Am J Public Health 2007;97(7):1319–25. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.085357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Beck AF, Klein MD, Kahn RS. Identifying social risk via a clinical social history embedded in the electronic health record. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012;51(10):972–7. 10.1177/0009922812441663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, Norton IM, Lowenstein SR, Abbott JT. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA 1997;277(17):1357–61. 10.1001/jama.1997.03540410035027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, Prescott L, Blackman K, Grube L, et al. Screening for depression in an urban pediatric primary care clinic. Pediatrics 2007;119(3):435–43. 10.1542/peds.2006-2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Henrikson NB, Blasi PR, Dorsey CN, Mettert KD, Nguyen MB, Walsh-Bailey C, et al. Psychometric and pragmatic properties of social risk screening tools: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2019;57(6 Suppl 1):S13–24. 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mahalingam S, Kahlenberg H, Pathak S. Social determinant of health screening tools with validity-related data. 2019. https://pharmacy.unc.edu/files/2020/02/SDoH-Report.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2021.

- 62. Paxton AE, Strycker LA, Toobert DJ, Ammerman AS, Glasgow RE. Starting the conversation performance of a brief dietary assessment and intervention tool for health professionals. Am J Prev Med 2011;40(1):67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hahn H, Katz M, Isaacs JB. What is it like to apply for SNAP and other work supports? Findings from the Work Support Strategies Evaluation. Urban Institute. 2017. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/92766/2001473_whats_it_like_to_apply_for_snap_and_other_work_supports.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2021.