Description

A 26-year-old male patient presented with a history of assault with a sharp object—an ice pick over the forehead at the level of the medial canthus. He presented with severe pain in the right eye and complete vision loss. On examination, the patient denied perception of light from the right eye with mildly dilated and fixed pupils. The patient did not present any neurological symptoms nor develop rhinorrhoea, and the Glasgow Coma Scale score was normal (15/15). He remained under observation and was treated with intravenous antibiotics and corticosteroids.

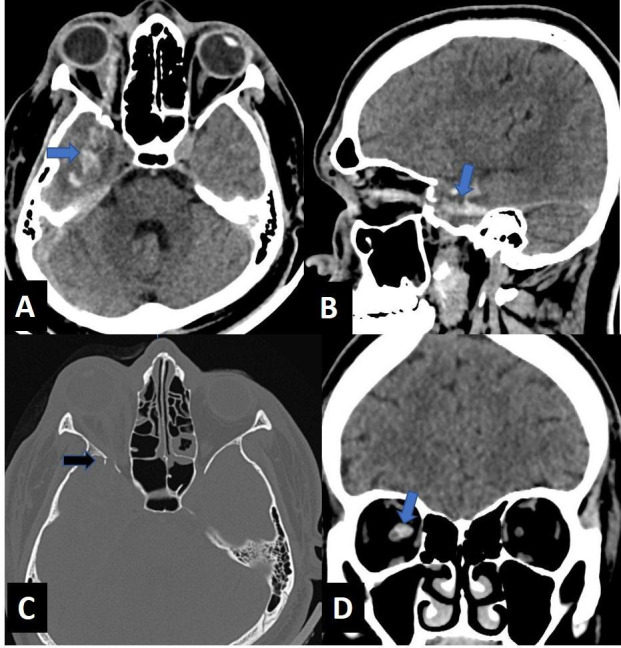

The skin wound was sutured, and CT of the head was performed with angiography study to assess the extent of the injury and to rule out the development of post-traumatic arterial pseudoaneurysm. A linear hyperdense track representing the course of the ice pick was seen passing medial to lateral entering the intraconal compartment, involving the optic nerve. It was seen further passing through the lateral wall of the right orbit with associated fracture of the right greater wing of sphenoid to enter the right temporal lobe with its haemorrhagic contusion. Few tiny fracture fragments were seen protruding into the intracranial extra-axial region (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Axial (A) and sagittal (B) images of the head reveal a linear hyperdense track (curved arrow), which is passing medial to lateral, entering the right orbit medial to the globe along the medial canthus, involving the intraconal compartment with intracranial extension causing temporal lobe laceration (blue arrow). Axial (C) bone window image of the orbit reveals displaced fracture of the right greater wing of sphenoid with few tiny fracture fragments seen protruding into the intracranial extra-axial region (black arrow). Coronal (D) image of the orbit reveals the hyperdense tract closely abutting the right optic nerve (blue arrow).

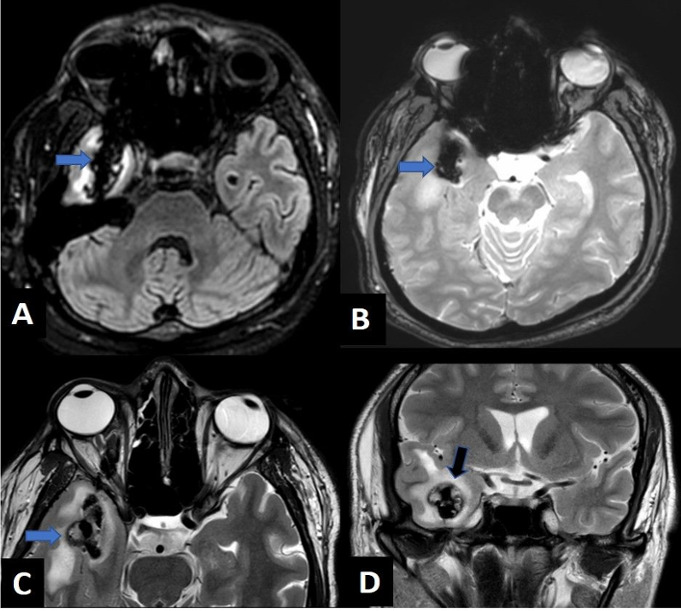

An MRI was performed to assess the extent of optic nerve injury. MRI revealed a T1/T2/Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hypointense track with multiple foci of blooming on susceptibility-weighted images seen along the course of the above-mentioned tract and in the temporal lobe. There was complete transection of the intraorbital portion of the right optic nerve with T2 hyperintense signal, suggestive of oedema (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Axial FLAIR (A), gradient recalled echo (B), T2WI (C) and coronal T2WI (D) images revealing linear hypointense tract (blue arrow) showing blooming on gradient recalled echo images and laceration involving the right temporal region (black arrow). FLAIR, Fkuid-attenuated inversion recovery; T2WI, T2 weighted image.

Long and thin penetrating objects such as an ice pick in our case commonly extend posteriorly and towards the apex owing to the pyramidal shape of the orbit with damage to the nerves and extraocular muscles along its course.1 The globe is not injured commonly and may act as a deflecting force.

Patients with orbital penetrating injuries should undergo emergent surgical exploration. Imaging evaluation is a must before surgery because most of the patients present with a minor external injury and intact neurological status.1 CT helps to assess the location, extent of the penetrating injury and damage caused by the object; detects retained hyperdense foreign bodies, cranial fractures and location of displaced fracture fragments; and helps in surgical planning. Turbin et al divided the orbital surface into four zones, which can predict the course of the penetrating object and resultant damage to the ocular or intracranial structures using 3D CT reconstructions.2 Transorbital intracranial injuries can be classified depending on the presence or absence of orbital fractures; involvement of orbital foramen or fissures; presence of injury to the globe, nerves, vessels or cerebrum; and whether there are associated calvarial or facial fractures. 3D CT reconstruction of angiography studies enables an excellent depiction of the course of the penetrating objects in relation to important intracranial structures and blood vessels.3 However, CT may sometimes underestimate the depth of injury.1 MRI is indicated to assess the status of the optic nerve, know the exact site of the transection and detect intracranial complications.

Patient’s perspective.

I was assaulted by a group of people, and an ice pick was thrust into my eye by someone. This was removed by the bystanders, and I was brought to the hospital. I was in severe pain. I was not able to see anything from my right eye. I was worried that I will lose my vision. When I was brought to the emergency department, the doctor examined me. My wound was cleaned and sutured by the doctor on call. An ophthalmologist examined me; he shone a torchlight into my right eye with the left eye closed; I was not even able to see the light. The nurse took my blood sample and gave me painkillers and intravenous antibiotics. The doctor asked me to get an emergency CT scan done to see if any part of the ice pick was still present inside my eye. On the CT scan, they saw that I had a brain injury as well. I was surprised on hearing it as I was conscious. MRI study was also advised, which showed complete damage to my right optic nerve. The doctors performed emergency surgery on me. The operating team consisted of an ophthalmologist, neurosurgeon, anaesthetist, nurses and other paramedical staff. After the surgery, I was told I will never be able to see again with my right eye as they found that my right optic nerve was severely damaged. Even though I lost vision in my right eye, I am grateful to the doctors for the prompt treatment that I received that saved my life.

Learning points.

Transorbital intracranial penetrating injuries may present with small external injuries and indolent clinical presentation; however, these cases must be dealt with utmost caution, and cross-sectional imaging evaluation must be performed to determine the extent of injury and detect retained foreign bodies and for surgical planning.

CT of the brain is mandatory in all patients with penetrating transorbital injuries.

A multidisciplinary approach is essential between a radiologist, ophthalmologist and neurosurgeons in such cases.

Footnotes

Contributors: MMM and ARJ—concept, design, literature search, manuscript preparation and review. AK and VPF—design, literature search and manuscript preparation.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.van Duinen MTA. Neuroimaging. In: The transorbital intracranial penetrating injury. Springer, Dordrecht, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turbin RE, Maxwell DN, Langer PD, et al. Patterns of transorbital intracranial injury: a review and comparison of occult and non-occult cases. Surv Ophthalmol 2006;51:449–60. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2006.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balasubramanian C, Kaliaperumal C, Jadun CK, et al. Transorbital intracranial penetrating injury-an anatomical classification. Surg Neurol 2009;71:238–40. 10.1016/j.surneu.2007.07.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]