Abstract

Introduction:

The emergence of urinary biomarkers for bladder cancer diagnosis could provide a reliable and less invasive diagnostic method. It could be also used as an adjuvant to the current gold standards of cytology and cystoscopy to improve diagnostic accuracy and decrease the percentage of false positives.

Methods:

We searched PubMed, SCOPUS, and Web of Science up to March 18, 2020. We selected four studies that assessed the diagnostic accuracy of urinary apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA-1) in detecting bladder cancer and met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Two authors independently extracted the data and performed quality assessment of the studies.

Results:

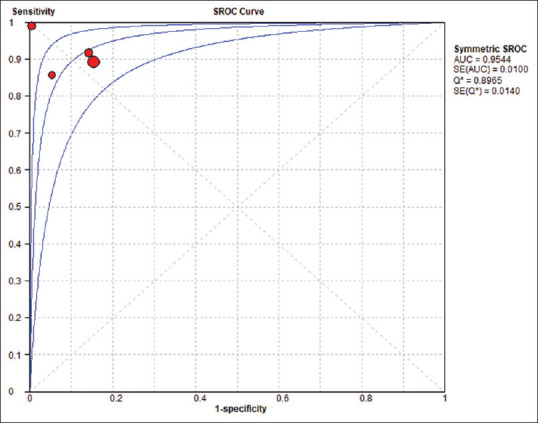

Four studies with 771 participants were selected; 417 were bladder cancer patients and 354 were controls. Bladder cancer was either transitional cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, the stages varied between Ta to T3, and the grades varied between G1 and G3. The pooled sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, and diagnostic odds ratio were 90.7%, 90%, 9.478, 0.1, and 99.424, respectively. Summary receiver operating characteristic curve showed an area under the curve of 0.9544 and Q* index of 0.8965.

Conclusions:

ApoA-1 showed high sensitivity and specificity, so it could be a useful biomarker in diagnosis of bladder cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Bladder cancer is the tenth most commonly diagnosed neoplasia globally, with about 573,000 new cases and 213,000 deaths.[1]

Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) is the main diagnostic type of bladder cancer. About 70%–80% of TCC is diagnosed as nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and 20%–30% as muscle invasive BC (MIBC). However, 10%–30% of patients with NMIBC progress to invasive disease.[2,3,4,5]

Early diagnosis of recurrence is essential, and detection of recurrence is usually performed through frequent cytology and cystoscopy with or without biopsy. In addition, these techniques are also essential for initial diagnosis for patients presented with hematuria. They are the gold standards for diagnosis of bladder cancer. However, they have many limitations. Although cytology has a high specificity (86%) and also a high sensitivity in detecting high-grade bladder tumor, it has a low sensitivity for low-grade tumors (16%). Furthermore, it depends mainly on cytopathologist experience with a high inter- and intra-observer variability.[6,7,8,9,10]

On the other hand, cystoscopy has a high sensitivity and specificity. However, it is an invasive, painful, time-consuming, and costly procedure that is not well accepted for patients. In addition, it may cause urinary tract infection. Furthermore, bladder mucosa irregularities and small areas of carcinoma in situ may contribute to a significant rate of false negatives (FNs) due to operator error.[11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]

Consequently, more reliable and less invasive diagnostic methods should be developed for diagnosis and surveillance of bladder carcinoma.[20]

Urinary biomarkers may emerge as one of these noninvasive, highly sensitive, and specific diagnostic tools for early detection of bladder cancer. They provide the advantages of the ease of sample collection and fast results detection. In addition, they are attractive methods due to the direct contact of the urine with the urothelial tumor cells.[16,21]

Tan et al. reported a high sensitivity for some urinary biomarkers in detecting bladder cancer. Their diagnostic ability increased when combined with cytology.[22] However, although the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the use of some of the commercially available urine-based tests, they are not included in the international guidelines for bladder cancer management.[14,20]

Apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA-1) is one of the urinary biomarkers that can diagnose bladder cancer. It is a major structural part of high-density lipoprotein (HDL). It plays an important role in transporting cholesterol back to the liver, in addition to other functions in immunity, inflammation, and apoptosis. The antitumor function of ApoA-1 is recently identified.[23] Recent studies pronounced that ApoA-1 level was high in certain types of tumors, indicating that it could be used as a potential biomarker for the diagnosis.[24,25,26] Chen et al.[27] detected a high level of ApoA-1 in the urine samples of patients with bladder cancer, which made ApoA-1 a promising noninvasive test for bladder cancer diagnosis. Other studies suggested the potentiality of using urine ApoA-1 for diagnosis of bladder cancer due to its high sensitivity and specificity.[25,26,28]

In this meta-analysis, we aimed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of ApoA-1 in detecting bladder cancer.

METHODS

Data sources and searches

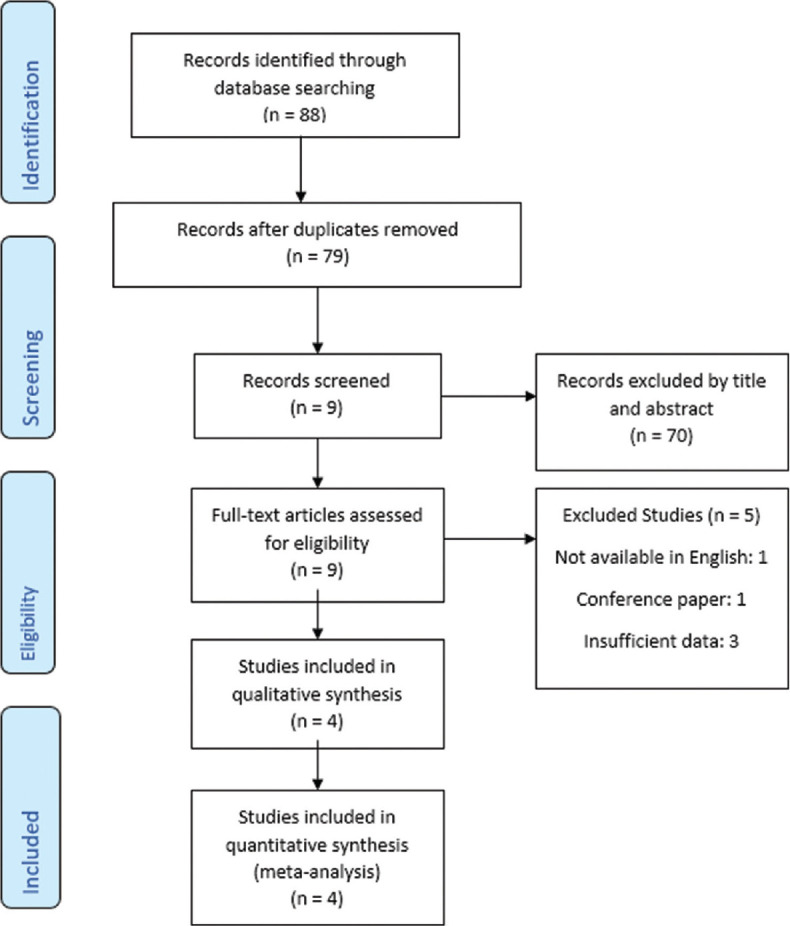

We systematically searched online databases: PubMed, SCOPUS, and Web of Science up to March 18, 2020. Studies were collected according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.[29] The details of the search process and study selection are shown in Figure 1. We used English terms in search: Urinary bladder, Urinary Bladder Neoplasm, Bladder Tumors, Malignant Tumor of Urinary Bladder, Bladder Cancer, Transitional Cell Carcinoma, ApoA-1, Apolipoprotein A I, Pro-Apolipoprotein A-I, Apolipoprotein A-I Isoprotein-2, Apolipoprotein A-I Isoprotein-4, Apolipoprotein AI Propeptide, Apolipoprotein A-I Isoproteins.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram for database searches and study selection

Study selection

Studies that met the following criteria were included: (i) ApoA-1 was used as a biomarker for diagnosis of urinary bladder cancer. (ii) The biomarker was ApoA-1 measured in the urine sample. (iii) Bladder cancer was confirmed by standard diagnostic methods (cystoscopy and histopathology). (iii) Sufficient data were available to calculate sensitivity and specificity of ApoA-1. (iv) Study publication should be in peer-reviewed scientific journal. (v) Full-text should be available in English. However, we excluded the following: (i) conference paper, review articles, reply and comments; (ii) animal studies; and (iii) papers with duplicate population.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors (K.A.M. and K.T.D.) collected the following data from the studies: Author, publication year, country, method, assay type, number of cases (true positives [TP] + FNs), controls (true negatives and false positives [FP]), total number of participants, gold standard used, and cutoff values. We assessed the quality of the included studies using QUADAS-2 tool.[30]

Data synthesis and analysis

MetaDisc 1.4[31] was used in data analysis. Pooled estimates of sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (PLR), negative likelihood ratio (NLR), and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) were calculated and plotted with 95% confidence interval (CI). Summary receiver-operating characteristic curve (sROC) was plotted. Spearman's correlation coefficient, inconsistency (I2), Chi-square test, and Cochran's Q test were performed to test for heterogeneity. The pooled effect was calculated using a random-effects model of DerSimonian–Laird when heterogeneity was present (I2 > 50%, P < 0.05) and a fixed-effects model of Mantel–Haenszel was utilized when no heterogeneity was found.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analysis test by leaving out Salem et al.'s study[28] as they used only Western-blot technique – which is a semiquantitative method – to measure the level of ApoA-1, whereas Li et al., 2014,[25] Li et al., 2011,[26] and Chen et al., 2010[27] used ELISA which is a quantitative method. In addition, we assessed if Salem et al.'s study was the source of the statistical heterogeneity. Therefore, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to investigate the effect of Salem et al.'s study by leaving it out.

Ethics compliance

This study is a systematic review of available evidence and is IRB exempt.

RESULTS

Selected studies and extracted data

Four studies were included in this meta-analysis.[25,26,27,28] The total number of participants was 771, including 417 bladder cancer patients and 354 controls. The controls were either healthy individuals or patients with benign condition as cystitis or hernia. In the studies by Li et al., 2011,[26] Li et al., 2014,[25] and Chen et al., 2010,[27] the urine samples used for validation of ApoA-1 as a diagnostic biomarker were blinded to the examiners as the samples were anonymously labeled and numbered, while in the Salem et al.'s study in 2019,[28] the examiners knew beforehand which samples belonged to which group. All studies measured the level of ApoA-1 in the urine sample. Information about the included studies and the extracted data are shown in Tables 1-3

Table 1.

Information about the selected studies

| Author | Country | Method | Assay type | Control | Golden standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salem et al., 2019[28] | Egypt | Case-control | Western blot | Cystitis/normal | Histopathological |

| Li et al., 2014[25] | China | Blinded sample validation | Western blot/ELISA | Normal | Histopathological |

| Li et al., 2011[26] | China | Blinded sample validation | ELISA | Normal | Cystoscopy with histopathological |

| Chen et al., 2010[27] | Taiwan | Blinded sample validation | ELISA | Hernia | Histopathological |

Table 3.

Data extracted

| Study | Controls | Bladder cancer | Cut-off | TP | FP | FN | TN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salem et al., 2019[28] | 100 | 50 | 195.6* | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Li et al., 2014[25] | 156 | 223 | 19.21 ng/ml | 199 | 24 | 24 | 132 |

| Li et al., 2011[26] | 49 | 107 | 18.22 ng/ml | 98 | 7 | 9 | 42 |

| Chen et al., 2010[27] | 37 | 49 | 12 ng/ml | 42 | 2 | 7 | 35 |

*Total protein normalization ratio. FN=False negative, FP=False positive, TN=True negative, TP=True positive

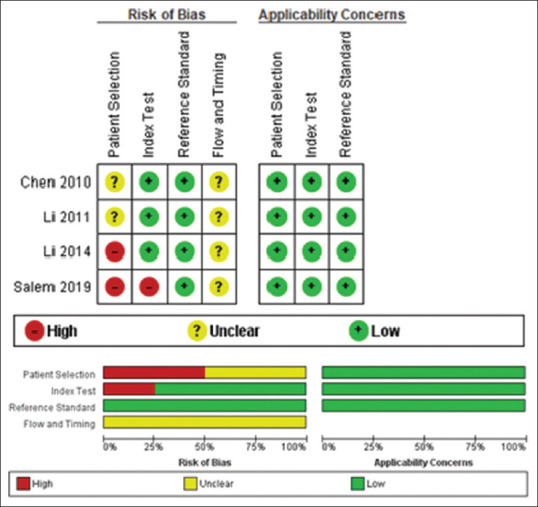

Quality assessment

According to the QUADAS-2 tool,[30] two of the studies[25,28] had a high risk of bias regarding patient selection process, most of which was due to nonrandom or unclear selection of the participants, in addition to inappropriate exclusion criteria such as exclusion of patients with chronic kidney disease. As for the sample collection and validation in Salem et al.'s study in 2019,[28] sample randomization was not done and the investigators were not blinded to whether the samples were taken from bladder cancer patients or from controls; this introduces a high risk of bias. The time interval between ApoA-1 measurement, biopsy, and cystoscopy was not clearly stated in any of the studies, so we concluded the risk of bias to be unclear in the “flow and timing” domain in the QUADAS-2 tool [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary and graph for the selected studies

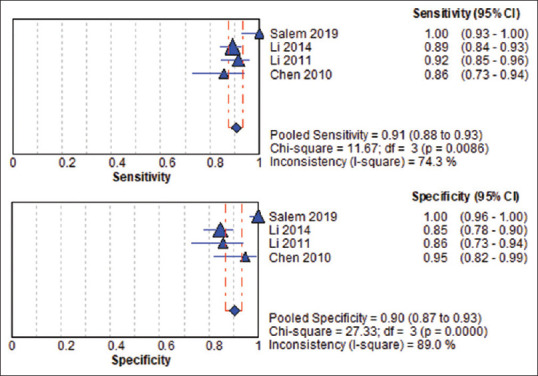

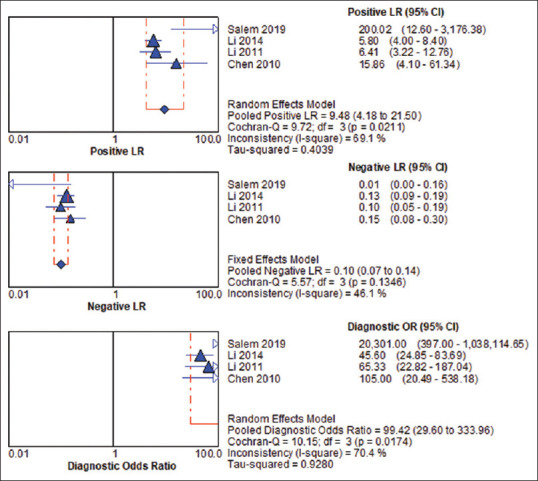

Data analysis

The pooled sensitivity and specificity of ApoA-1 were 90.7% (95% CI, 87.5%–93.3%) and 90% (95% CI, 86.1%–93%), respectively [Figure 3], and the pooled DOR was 99.424 (95% CI, 29.6–333.96). The pooled PLR was 9.478 (95% CI, 4.178–21.502), while the pooled NLR was 0.100 (95% CI, 0.073–0.138) [Figure 4]. For heterogeneity testing, the Spearman's correlation coefficient was − 0.4, (P = 0.6), indicating no threshold effect [Table. 4]. The χ2 was 11.67, 27.34, 9.72, 5.57, and 10.15 for sensitivity, specificity, PLR, NLR, and DOR, respectively. The results of inconsistency test for the different estimates were significant for sensitivity (I2 = 74.3%, P = 0.009), specificity (I2 = 89%, P = 0.000), DOR (I2 = 70.4%, P = 0.017), and PLR (I2 = 69.1%, P = 0.021), while the estimation of heterogeneity for NLR was insignificant with (I2 = 46.1%, P = 0.135), indicating heterogeneity for reasons other than threshold effect. The sROC result showed that the area under the curve and Q* index was 0.9544 and 0.8965, respectively [Figure 5]. Detailed analysis of estimates is shown in Table 5.

Figure 3.

Pooled sensitivity and specificity of apolipoprotein A1

Figure 4.

Pooled positive likelihood ratio negative likelihood ratio and diagnostic odds ratio of apolipoprotein A1

Table 4.

Moses’ model (D=a+bS), area under the summary receiver operating characteristic curve and Spearman’s correlation of apolipoprotein A1

| Marker | Variable | Coefficient | SE | T | P | SE | Spearman correlation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| AUC | Q* | R | P | ||||||

| Apo A1 | a | 4.318 | 0.301 | 14.359 | 0.0048 | 0.9544 | 0.8965 | −0.400 | 0.600 |

| b | −0.818 | 0.544 | 1.503 | 0.2718 | 0.0100 | 0.0140 | |||

Tau-squared estimate=0.0000, a=Intercept, b=Slope, coefficient b represents the dependency of test accuracy on threshold, b≠0 indicates heterogeneity. SE=Standard error, AUC=Area under the curve. Q* index=the point in receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve space closest to the ideal top left-hand corner and where test sensitivity and specificity are equal.

Figure 5.

Summary receiver-operating characteristic curve for apolipoprotein A1

Table 5.

Detailed analysis of the estimates of apolipoprotein A1

| Estimate | Value | 95% CI | I2 (%) | χ 2 | Heterogeneity P | Percentage weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | ||||||

| Salem, 2019 | 1.000 | 0.929-1.000 | 74.3 | 11.67 | 0.009 | |

| Li, 2014 | 0.892 | 0.844-0.930 | ||||

| Li, 2011 | 0.916 | 0.846-0.961 | ||||

| Chen, 2010 | 0.857 | 0.728-0.941 | ||||

| Pooled sensitivity | 0.907 | 0.875-0.933 | ||||

| Specificity | ||||||

| Salem, 2019 | 1.000 | 0.964-1.000 | 89.0 | 27.34 | 0.000 | |

| Li, 2014 | 0.846 | 0.780-0.899 | ||||

| Li, 2011 | 0.857 | 0.728-0.941 | ||||

| Chen, 2010 | 0.946 | 0.818-0.993 | ||||

| Pooled specificity | 0.900 | 0.861-0.930 | ||||

| Positive LR | ||||||

| Salem, 2019 | 200.02 | 12.595-3176.4 | 69.1 | 9.72 | 0.021 | 7.30 |

| Li, 2014 | 5.800 | 4.003-8.404 | 39.73 | |||

| Li, 2011 | 6.411 | 3.221-12.760 | 33.13 | |||

| Chen, 2010 | 15.857 | 4.099-61.337 | 19.84 | |||

| REM pooled LR+ | 9.478 | 4.178-21.502 | ||||

| Negative LR | ||||||

| Salem, 2019 | 0.010 | 0.001-0.155 | 46.1 | 5.57 | 0.135 | 21.11 |

| Li, 2014 | 0.127 | 0.087-0.187 | 48.47 | |||

| Li, 2011 | 0.098 | 0.052-0.185 | 17.98 | |||

| Chen, 2010 | 0.151 | 0.076-0.301 | 12.44 | |||

| FEM pooled LR− | 0.100 | 0.073-0.138 | ||||

| DOR | ||||||

| Salem, 2019 | 20,301.0 | 397.00-1,038,114 | 70.4 | 10.15 | 0.017 | 7.71 |

| Li, 2014 | 45.604 | 24.852-83.685 | 37.32 | |||

| Li, 2011 | 65.333 | 22.822-187.04 | 31.43 | |||

| Chen, 2010 | 105.00 | 20.486-538.18 | 23.54 | |||

| REM pooled DOR | 99.424 | 29.600-333.96 |

I2=Inconsistency test, REM=Random effects model, FEM=Fixed effects model, LR=Likelihood ratio, DOR=Diagnostic odds ratio, CI=Confidence interval

Sensitivity analysis

The study of Salem et al.[28] was found to have a high risk of bias regarding the patient selection methodology, and the assay method was different than other studies; hence, we tried eliminating the study from the results. Following the exclusion, there was neither major effect on the sensitivity nor the specificity, as the new values were still within the 95% CI of the old values. However, the heterogeneity dropped substantially, indicating that Salem et al.'s study[28] was a possible source of heterogeneity in the data [Table 6].

Table 6.

Apolipoprotein A1 test performance following exclusion of Salem et al., 2019

| Parameter | Pooled value | New 95% CI | Heterogeneity I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 0.9-0.89 | 0.86-0.92 | 74.3-0 |

| Specificity | 0.9-0.86 | 0.81-0.90 | 89.0-35.1 |

| DOR | 99.4-53.5 | 32.43-88.25 | 70.4-0 |

CI=Confidence interval, I2=Inconsistency test, DOR=Diagnostic odds ratio

DISCUSSION

Urinary biomarkers have been developed as noninvasive potential diagnostic markers for bladder cancer. One of these urinary biomarkers is the ApoA-1. ApoA-1 is the major structural protein component of HDL and present in other lipoproteins in smaller amounts.[32]

The current meta-analysis is the first to evaluate the diagnostic value of urinary ApoA-1 as a biomarker for bladder cancer. We have comprehensively searched and assessed the published literature regarding the role of ApoA-1 in bladder cancer. We have focused solely on the data regarding the level of the marker in the urine sample. Using the random-effects model, the overall pooled sensitivity and specificity of the urine ApoA-1 were 90.7% and 90%, respectively.

In a meta-analysis on sensitivity and specificity of urinary cytology for diagnosis of bladder cancer, they were reported to be 37% and 95%, respectively.[33] Furthermore, Yafi et al.[9] stated that urinary cytology has a low sensitivity of 48% (16% for low-grade tumors and 84% for high-grade tumors) and a high specificity of 86%. Li et al.,[25] compared urine ApoA-1 (89.2% sensitivity, 84.6% specificity) versus exfoliative urinary cytology (72.2% sensitivity, 90.4% specificity) and reported better sensitivity with ApoA-1 but better specificity with cytology. Thus, ApoA-1 has higher sensitivity but with slightly lower or nearly similar specificity as urinary cytology. This means that urinary ApoA-1 is better in detecting bladder cancer; however, cytology has a slight edge in ruling out the disease.

The U.S. FDA approved a few urinary biomarkers for diagnosis of bladder cancer, including fluorescent in situ hybridization UroVysion (FISH UroVysion), nuclear matrix protein 22 assessed by point of care (NMP22-POC), bladder tumor antigen (BTA) STAT, and BTA TRAK. The sensitivities of FISH, NMP, BTA STAT, and BTA TRAK were 72%, 50%, 70%, and 65%, respectively, and the specificities were 83%, 87%, 75%, and 65%, respectively.[6,34,35] Other non-FDA-approved urinary biomarker kits are available for bladder cancer diagnosis. They include UBC Rapid test, Xpert test, and Cx bladder with reported sensitivities of 53.3%, 75.8%, and 82%, respectively, and specificities of 93.8%, 84.6%, and 85%, respectively.[36,37] None of these available urinary biomarkers have achieved satisfactory diagnostic sensitivity and specificity to replace the combination of cystoscopy and cytology.[26]

In the current meta-analysis, ApoA-1 showed higher sensitivity and specificity than the previously mentioned biomarkers except for UBC Rapid test specificity, thus; ApoA-1 seems to be more accurate and promising in diagnosis of bladder cancer. In addition, ApoA-1 has an advantage in diagnosis of low-grade tumors when compared to other urinary biomarkers including BTA STAT, FISH UroVysion, and UBC Rapid test which were found to have low sensitivity in detection of low-grade tumors.[36,38,39] In contrast, Chen et al.[27] reported that ApoA-1 could detect low-grade early-stage tumors and differentiate them from nontumor with a sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 83.8%, respectively, at a cutoff value of 7 ng/ml.

ApoA-1 was also reported to distinguish patients with low malignant TCC from patients with aggressive TCC of the bladder. Li et al. reported the cutoff to be 29.86 ng/ml with a sensitivity and specificity of 83.7% and 89.7%, respectively.[26]

Liver and intestine are the main sites for synthesis of Apos. Liver synthesis could be affected by diet, alcohol consumption, fibric acids or niacin, lipid-lowering drugs, and various hormones including estrogens, androgens, insulin, glucagon, and thyroxin. On the other hand, lipid content in the diet is the main factor affecting intestinal synthesis of Apos.[40,41] Furthermore, the serum level of ApoA-1 is reduced during inflammation, especially chronic inflammation, and is also affected by different types of cancer including ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, and pancreatic cancer.[25,42,43] However, Salem et al. reported that the significantly higher levels of urinary ApoA-1 in patients with bladder cancer were not correlated to their corresponding blood levels, which showed no significant difference between the malignant group and the control group.[28] Furthermore, ApoA-1 is not released from bladder tumor cells. Li et al.,[25] analyzed bladder epithelium and tumor tissues and reported that ApoA-1 was expressed neither in bladder cancer tissues nor in morphologically normal bladder tissue. Thus, the source of ApoA-1 remains unclear. The combination of a biomarker and a gold standard test could enhance the early detection and diagnosis of bladder cancer.[44] Li et al.[25] showed that ApoA-1 combined with cytology resulted in higher sensitivity and decreased misdiagnosis. The application of exfoliative urinary cytology in combination with the urine Apo-A1 detection significantly increased the sensitivity of cytology in detecting bladder cancer from 72.2% (alone) to 93.7% (combined).[25] This combination could also be used for high-risk patients, for whom cytology is indicated including patients with persistent asymptomatic microscopic hematuria or microscopic hematuria with risk factors such as irritative voiding symptoms, tobacco use, or chemical exposure.[16] Lotan et al. used a nomogram based on age, gender, smoking status, ethnicity, and hematuria in addition to NMP22 to predict Bladder cancer in patients presenting with hematuria.[45] They reported 23 (6%) patients with bladder cancer. The predictive accuracy of that model was 0.79. The same could be applied using Apo-A1.

Heterogeneity is a potential problem when conducting a meta-analysis study,[46] it is caused by either the threshold effect, where the different cut-off values for the different studies is the cause of different sensitivities and specificities, or other factors such as the patients, methodology of testing, and different settings (nonthreshold effect). The Spearman's correlation coefficient r is calculated between the logit of sensitivity and logit of 1-specificity. A strong positive correlation would suggest threshold effect.[31] In our case, r = −0.4 (P = 0.6) that means the threshold effect played no role in heterogeneity of estimates. For heterogeneity by nonthreshold effect, Cochran's Q and inconsistency I2 tests were employed.[47] The result of I2 showed significant heterogeneity for all estimates, except for NLR. We investigated for the sources of heterogeneity and found the following: First, the study of salem et al. was a main source of heterogeneity in the data. Second, the different ethnicities for the patients as 3 studies included asian patients and one study included Egyptian patients. Lastly, the clinical characteristics of the patients such as tumour stage and grade were not consistent among the different studies [Tables 1 and 2]. All these factors could have contributed to the heterogeneity [Tables 1 and 2].

Table 2.

Tumor characteristics

| Author | Exclusion criteria | Tumor type | Tumor stage | Tumor grade | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salem et al., 2019[28] | Not receiving any medications | TCC 36 (72%) | Ta-T1 (58%) | G1 and | No renal failure |

| No surgery or cystoscopy | SCC 14 (28%) | T2-T4 (42%) | G2 50% | ||

| No radiological interventions | G3 50% | ||||

| No associated chronic diseases | |||||

| No other type of tumors | |||||

| Li et al., 2014[25] | No surgery or chemotherapy | Bladder cancer | - | - | No renal failure |

| No radiological interventions | |||||

| No chronic urinary tract diseases | |||||

| Li et al., 2011[26] | - | TCC | - | Grade I, II 58 Grade III 49 | No renal failure |

| Chen et al., 2010[27] | - | Bladder cancer | Early stage 38 | LG 14 | - |

| Advanced stage 11 | HG 35 |

TCC=Transitional cell carcinoma, SCC=Squamous cell carcinoma, LG=Low grade, HG=High grade

The reliability of different studies assessing biomarkers including urinary biomarkers is affected by patient selection. The patients and controls in these studies should reflect the real world. When assessing for the first diagnosis of bladder cancer, both cases and controls should be undergoing investigations for suspected bladder cancer, e.g., patients presenting with hematuria. If assessing for early detection of recurrence, all participants should be patients with previous resection of nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer who are undergoing surveillance for disease recurrence. However, bias could be observed in many of these studies due to many reasons including recruitment of advanced disease versus healthy participants to improve the sensitivity and specificity of the biomarkers and also recruitment of patients with large primary tumors, whereas the aim of the study is to diagnose small early recurrence.[48] In the four studies of the current meta-analysis, the control groups were healthy individuals, patients with hernia, or patients with chronic urinary diseases. It was not clear whether the indication of cystoscopy for these patients was to exclude suspected bladder cancer or was due to other reasons. In addition, four studies just confirmed that the urine samples were from patients diagnosed with bladder cancer based on cystoscopy and biopsy, but the timing of sample in relation to biopsy was not clear as well as indications for biopsy whether patients were in surveillance setting or were symptomatic. Future studies should recruit patients/controls who are undergoing cystoscopy for suspected bladder cancer or undergoing cystoscopies as a part of the follow-up protocol after previous resection of nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer. In the current meta-analysis, three studies used ELISA whereas the fourth study used Western blot. This is a limitation to the present study due to heterogeneity of used tests. Western blot may be less sensitive than ELISA as Western blot is semiquantitative whereas ELISA is quantitative test. However, the single study that used Western blot showed 100% sensitivity and specificity in differentiating patients with bladder cancer from control group.[28] Furthermore, Li et al. used Western blot than ELISA and reported significant difference in the level of ApoA-1 with both techniques.[25] However, whether to use Western blot or ELISA should be evaluated in future studies. We conducted a sensitivity analysis test by leaving out Salem et al.'s study[28] to investigate its effect. Following its exclusion, there was major effect on neither the sensitivity nor the specificity. However, the heterogeneity dropped substantially, indicating that Salem et al.'s study[28] was a possible source of heterogeneity in the data.

There was no follow-up for FP cases among controls in the recruited studies. However, it was reported in the literature that molecular changes may precede clinical findings up to many months earlier.[49] Thus, what appeared as FP may be actually TP. Unfortunately, this was not assessed in the recruited studies.

Several strengths are present in our study. All included studies used the same gold standard for diagnosis of bladder cancer. In addition, the included studies used reliable methods to quantify the level of ApoA-1 and to explore its diagnostic value. Furthermore, this is the first meta-analysis to assess the diagnostic accuracy of urine ApoA-1 in detecting bladder cancer.

Some limitations are to be considered in the current meta-analysis. The number of studies was limited. They were primarily from Asia. In addition, heterogeneity was present in the results due to the several factors discussed previously. We also noted high risk of bias in some of the included studies due to either the patient selection or methodology.[50] Furthermore, there was inappropriate exclusion of some candidates in the included studies, for example, the exclusion of the patients with chronic systemic illness in some studies may have introduced bias. Some studies recruited only patients with TCC, while other studies did not exclude patients with squamous cell carcinoma or other types and just reported the cases as bladder cancer. The distribution of high-grade versus low-grade cases or noninvasive versus muscle-invasive cases was clear in some studies but not reported in other studies. Furthermore, three of the included studies have excluded patients with renal failure, while the fourth study did not report that which make the results of the current meta-analysis may be not applicable for patients with renal failure. Some studies excluded patients on chemotherapy or medications. This may not replicate the real world as many patients on bladder cancer surveillance already received intravesical BCG. Finally, subgroup analysis was not performed (i.e. evaluation of ApoA-1 to discriminate between low-grade vs. high-grade tumors or early stage vs. advanced stages) due to insufficient clinical data. Thus, any future study on urinary biomarkers for diagnosis of bladder cancer should take these points into consideration. In addition, ApoA-1 should be evaluated for the possible correlation with prognosis including survival in patients with bladder cancer. Further, ApoA-1 is a lipoprotein with serum and urinary level that may be affected by other medical conditions or drugs as lipid-lowering drugs; however, Jurukovska-Nospal et al. found that atorvastatin has no significant effect on the serum level of ApoA-1, till now there is no significant evidence on the effect of lipid-lowering drug on the urinary level of ApoA-1 and remains under investigations.[51]

CONCLUSIONS

Urinary ApoA-1 showed high sensitivity and specificity even higher than FDA-approved urinary biomarkers. ApoA-1 seems to be a promising biomarker in diagnosis of bladder cancer. More studies should be done to assess the value of ApoA-1 in different grades and stages of bladder cancer. Studies should be conducted with proper design and implementation to decrease bias as much as possible.

Footnotes

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prout GR, Jr, Barton BA, Griffin PP, Friedell GH. Treated history of noninvasive grade 1 transitional cell carcinoma. The National Bladder Cancer Group. J Urol. 1992;148:1413–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36924-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herr HW. Tumor progression and survival of patients with high grade, noninvasive papillary (TaG3) bladder tumors: 15-year outcome. J Urol. 2000;163:60–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sylvester RJ, Van Der Meijden AP, Oosterlinck W, Witjes JA, Bouffioux C, Denis L, et al. Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: A combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur Urol. 2006;49:466–77. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Türkölmez K, Tokgöz H, Reşorlu B, Köse K, Bedük Y. Muscle-invasive bladder cancer: Predictive factors and prognostic difference between primary and progressive tumors. Urology. 2007;70:477–81. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mowatt G, Zhu S, Kilonzo M, Boachie C, Fraser C, Griffiths TR, et al. Systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of photodynamic diagnosis and urine biomarkers (FISH, ImmunoCyt, NMP22) and cytology for the detection and follow-up of bladder cancer. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14:1–331. doi: 10.3310/hta14040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bastacky S, Ibrahim S, Wilczynski SP, Murphy WM. The accuracy of urinary cytology in daily practice. Cancer. 1999;87:118–28. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990625)87:3<118::aid-cncr4>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leiblich A. Recent developments in the search for urinary biomarkers in bladder cancer. Curr Urol Rep. 2017;18:100. doi: 10.1007/s11934-017-0748-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yafi FA, Brimo F, Steinberg J, Aprikian AG, Tanguay S, Kassouf W. Prospective analysis of sensitivity and specificity of urinary cytology and other urinary biomarkers for bladder cancer. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Investig. 2015;33:66.e25–66e31. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Têtu B. Diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma from urine. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:S53–9. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Aa MN, Steyerberg EW, Bangma C, van Rhijn BW, Zwarthoff EC, van der Kwast TH. Cystoscopy revisited as the gold standard for detecting bladder cancer recurrence: Diagnostic review bias in the randomized, prospective CEFUB trial. J Urol. 2010;183:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitropoulos D, Kiroudi-Voulgari A, Nikolopoulos P, Manousakas T, Zervas A. Accuracy of cystoscopy in predicting histologic features of bladder lesions. J Endourol. 2005;19:861–4. doi: 10.1089/end.2005.19.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Z, Kim J. Urinary proteomics and metabolomics studies to monitor bladder health and urological diseases. BMC Urol. 2016;16:11. doi: 10.1186/s12894-016-0129-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santoni G, Morelli MB, Amantini C, Battelli N. Urinary markers in bladder cancer: An update. Front Oncol. 2018;8:362. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karakiewicz PI, Benayoun S, Zippe C, Lüdecke G, Boman H, Sanchez-Carbayo M, et al. Institutional variability in the accuracy of urinary cytology for predicting recurrence of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. BJU Int. 2006;97:997–1001. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chakraborty A, Dasari S, Long W, Mohan C. Urine protein biomarkers for the detection, surveillance, and treatment response prediction of bladder cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:1104–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gogalic S, Sauer U, Doppler S, Preininger C. Bladder cancer biomarker array to detect aberrant levels of proteins in urine. Analyst. 2015;140:724–35. doi: 10.1039/c4an01432d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herr HW. The risk of urinary tract infection after flexible cystoscopy in patients with bladder tumor who did not receive prophylactic antibiotics. J Urol. 2015;193:548–51. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shariat SF, Karam JA, Lotan Y, Karakiewizc PI. Critical evaluation of urinary markers for bladder cancer detection and monitoring. Rev Urol. 2008;10:120–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuiverloon TC, de Jong FC, Theodorescu D. Clinical decision making in surveillance of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: The evolving roles of urinary cytology and molecular markers. Oncology (Williston Park) 2017;31:855–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sapre N, Anderson PD, Costello AJ, Hovens CM, Corcoran NM. Gene-based urinary biomarkers for bladder cancer: An unfulfilled promise? Urol Oncol. 2014;32:48.e9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan WS, Tan WP, Tan MY, Khetrapal P, Dong L, deWinter P, et al. Novel urinary biomarkers for the detection of bladder cancer: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;69:39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mangaraj M, Nanda R, Panda S. Apolipoprotein A-I: A molecule of diverse function. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2016;31:253–9. doi: 10.1007/s12291-015-0513-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X, Zheng W, Wang W, Shen H, Liu L, Lou W, et al. A new panel of pancreatic cancer biomarkers discovered using a mass spectrometry-based pipeline. Br J Cancer. 2017;117:1846–54. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li C, Li H, Zhang T, Li J, Liu L, Chang J. Discovery of Apo-A1 as a potential bladder cancer biomarker by urine proteomics and analysis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;446:1047–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Li C, Wu H, Zhang T, Wang J, Wang S, et al. Identification of Apo-A1 as a biomarker for early diagnosis of bladder transitional cell carcinoma. Proteome Sci. 2011;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen YT, Chen CL, Chen HW, Chung T, Wu CC, Chen CD, et al. Discovery of novel bladder cancer biomarkers by comparative urine proteomics using iTRAQ technology. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:5803–15. doi: 10.1021/pr100576x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salem H, Ellakwa DE, Fouad H, Abdel M. Gene reports APOA1 and APOA2 proteins as prognostic markers for early detection of urinary bladder cancer. Gene Rep. 2019;16:100463. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Aug 18;151 (4):264-9, W64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. Epub 2009 Jul 20. PMID: 19622511. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zamora J, Abraira V, Muriel A, Khan K, Coomarasamy A. Meta-DiSc: A software for meta-analysis of test accuracy data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Von Zychlinski A, Williams M, McCormick S, Kleffmann T. Absolute quantification of apolipoproteins and associated proteins on human plasma lipoproteins. J Proteomics. 2014;106:181–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie Q, Huang Z, Zhu Z, Zheng X, Liu J, Zhang M, et al. Diagnostic value of urine cytology in bladder cancer. Anal Quant Cytol Histol. 2016;38:38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hajdinjak T. UroVysion FISH test for detecting urothelial cancers: Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy and comparison with urinary cytology testing. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Investig. 2008;26:646–51. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glas AS, Roos D, Deutekom M, Zwinderman AH, Bossuyt PM, Kurth KH. Tumor markers in the diagnosis of primary bladder cancer. A systematic review. J Urol. 2003;169:1975–82. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000067461.30468.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ecke TH, Weiß S, Stephan C, Hallmann S, Arndt C, Barski D, et al. UBC® rapid test – A urinary point-of-care (POC) assay for diagnosis of bladder cancer with a focus on non-muscle invasive high-grade tumors: Results of a multicenter-study. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3891. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Sullivan P, Sharples K, Dalphin M, Davidson P, Gilling P, Cambridge L, et al. A multigene urine test for the detection and stratification of bladder cancer in patients presenting with hematuria. J Urol. 2012;188:741–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Batista R, Vinagre N, Meireles S, Vinagre J, Prazeres H, Leão R, et al. Biomarkers for bladder cancer diagnosis and surveillance: A comprehensive review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10:39. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10010039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kassouf W, Traboulsi SL, Schmitz-Dräger B, Palou J, Witjes JA, van Rhijn BW, et al. Follow-up in non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer – International Bladder Cancer Network recommendations. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Investig. 2016;34:460–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marcil V, Delvin E, Seidman E, Poitras L, Zoltowska M, Garofalo C, et al. Modulation of lipid synthesis, apolipoprotein biogenesis, and lipoprotein assembly by butyrate. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G340–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00440.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren L, Yi J, Li W, et al. Apolipoproteins and cancer. Cancer Med. 2019;8(16):7032–7043. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2587. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2587Kozak KR, Su F, Whitelegge JP, Faull K, Reddy S, Farias-Eisner R. Characterization of serum biomarkers for detection of early stage ovarian cancer. Proteomics 2005;5:4589-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ai J, Tan Y, Ying W, Hong Y, Liu S, Wu M, et al. Proteome analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma by laser capture microdissection. Proteomics. 2006;6:538–46. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhat A, Ritch CR. Urinary biomarkers in bladder cancer: Where do we stand? Curr Opin Urol. 2019;29:203–9. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lotan Y, Svatek RS, Krabbe LM, Xylinas E, Klatte T, Shariat SF. Prospective external validation of a bladder cancer detection model. J Urol. 2014;192:1343–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.05.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hardy RJ, Thompson SG. Detecting and describing heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 1998;17:841–56. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<841::aid-sim781>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.D'Costa JJ, Goldsmith JC, Wilson JS, Bryan RT, Ward DG. A systematic review of the diagnostic and prognostic value of urinary protein biomarkers in urothelial bladder cancer. Bladder Cancer. 2016;2:301–17. doi: 10.3233/BLC-160054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abelson S, Collord G, Ng SW, Weissbrod O, Mendelson Cohen N, Niemeyer E, et al. Prediction of acute myeloid leukaemia risk in healthy individuals. Nature. 2018;559:400–4. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0317-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pannucci CJ, Wilkins EG. Identifying and avoiding bias in research. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:619–25. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181de24bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jurukovska-Nospal M, Arsova V, Levchanska J, Sidovska-Ivanovska B. Effects of statins (atorvastatin) on serum lipoprotein levels in patients with primary hyperlipidemia and coronary heart disease. Prilozi. 2007;28:137–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]