Abstract

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been postulated to be associated with hypercoagulability, leading to thromboembolism in major blood vessels. There are also increasing reports of invasive fungal infections in COVID-19 patients. We report a unique case of mucormycosis associated with renal artery thrombosis leading to renal infarction and nephrectomy in a COVID-19 patient. This is the first such reported case to our knowledge.

INTRODUCTION

The spectrum of disease due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection ranges from asymptomatic or mild disease to severe illness, leading to multiorgan failure and death. Coagulopathy in the form of arterial and venous thromboembolism, is one of the most severe sequelae of the disease.[1] The high incidence of reported thromboembolism, despite prophylactic and therapeutic anticoagulation, raise a question regarding the pathophysiology of COVID-19 infection.[2]

CASE REPORT

A 32-year-old male, presented to the emergency department, complaining of abdominal pain, obstipation, and vomiting for 6 days. The patient had no comorbidities and no surgical history. He was a nonsmoker, tee-totaller, and gave no history of recreational drug use. There was no history of lower urinary tract symptoms and hematuria. The patient was previously admitted 1 month earlier in a peripheral hospital for high-grade fever, dyspnea, dry cough, and generalized weakness and was tested positive for COVID-19 in a nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab RT-PCR test. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) showed CT severity score to be 11/25. He was discharged 14 days later, after full recovery from all his symptoms. At discharge, his COVID-19 swab was negative.

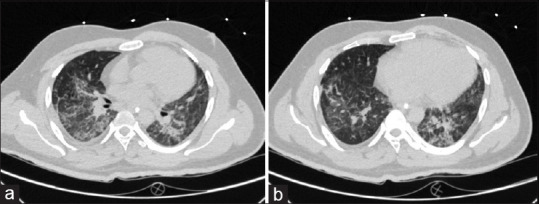

On evaluation at this admission, which was after 16 days after previous discharge, the patient was tachypneic (respiratory rate, 48 breaths/min) with worsening dyspnea with oxygen saturation 96% on nasal prong with an oxygen flow rate of 15 L/min. The patient was afebrile (97.8°F) with pulse rate (106 beats/min) and normal blood pressure (106/68 mmHg). He was conscious and well-oriented. His abdomen was tense and distended with moderate guarding and rigidity, There was associated generalized abdominal tenderness which was more in the right hypochondriac and right lumbar regions. Bowel sounds were sluggish. On rectal examination, anal tone was normal and rectum was empty. All peripheral pulses were present, and bilateral upper and lower limbs were warm. The initial laboratory workup revealed leukocytosis (white blood cell count 36,200/μL) with neutrophilia, hemoglobin 10.3 g/dl, and platelet count of 265,000/μL [Table 1]. HRCT was done on re-admission which was suggestive of sequelae of viral pneumonia [Figure 1].

Table 1.

Laboratory findings

| Investigations | Case | Reference range |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.3 | 12-15.0 |

| WBC count (/µl) | 36,200 | 4000-10,000 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 88.3 | 40-75 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 164 | 80-100 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 21 | <0.5 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 1145 | <248 |

| γ-glutamyltransferase (U/L) | 293 | <55 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.3 | 0.6-1.2 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/ml) | 3.8 | 0-0.5 |

| D-dimer (ng/ml) | 420 | <500 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 616 | 200-400 |

CRP=C-reactive protein, WBC=White blood cell

Figure 1.

High-resolution computed tomography chest. (a) Diffuse areas of ground glass densities, interstitial septal thickening, (b) Reticulation giving crazy paving appearance

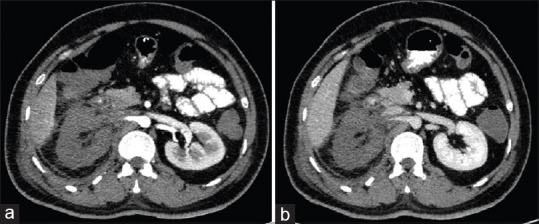

The patient was managed in the intensive care unit (ICU) and was continued on nasal prong with an oxygen flow rate of 15 L/min. COVID-19 RT-PCR swab was negative. Initial abdominal sonography suggested mildly enlarged liver, gaseous bowel loops with mild ascites, and right-sided pleural effusion and hepatitis. The right kidney was bulky and hypoechoic. A small 10–15 ml collection with internal echoes and debris was seen in the right perinephric space. No intraparenchymal collection and hydronephrosis was seen. The left kidney appeared normal in size, shape, and echogenicity. A nasogastric tube was placed for subacute intestinal obstruction. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography abdomen suggested completely nonenhancing right kidney with renal artery thrombosis and right renal infarction [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Computed tomography angiography. (a) Arterial phase - Abrupt cut off of the right renal artery was seen 2.7 cm distal to its origin, suggesting of thrombosis and right renal infarction (b) Venous Phase - hypodense and completely non-enhancing right kidney

The patient was planned for emergency right retroperitoneal exploration along with right nephrectomy. Intraoperatively, there was severe subcutaneous edema with poorly viable musculature. There was intermittent necrotic tissue along with infarcted right kidney and necrotic perirenal fat and Gerota's fascia. Right nephrectomy along with complete debridement of necrotic tissue was done. The patient was shifted back to the ICU after operative intervention on ionotropes and ventilatory support. The patient continued to deteriorate and expired in the ICU.

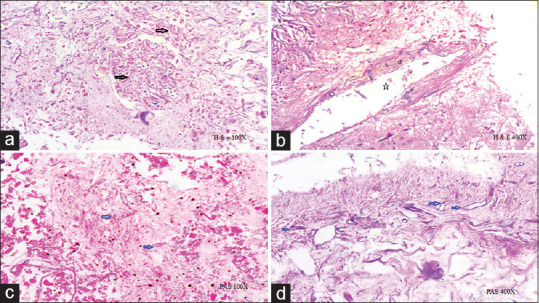

Gross examination of the specimen showed blurred corticomedullary junction in the middle part of the kidney with areas of congestion. On microscopic examination, there was marked necrosis along with many fungal elements. The fungus had irregular cell wall, obtuse angle branching, and aseptate hyphae. Areas of angioinvasion were seen. Large area of fat necrosis with cholesterol cleft was seen in the surrounding area. The ureter also showed similar features [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Histological images. (a) Near complete necrosis of renal parenchyma seen with numerous invasive fungus hyphe (Black arrows). (b) Areas of angioinvasion seen (*). (c) On PAS stain fungal hyphe are identified (blue arrows). (d) Fungal has irregular cell wall, aseptate hyphe, obtuse angle branching (blue arrows)

DISCUSSION

Although the prognosis of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 disease is often determined by the extent of pulmonary lesions, hypercoagulabilty leading to thromboembolism in COVID-19 patients, is emerging as a major pathological occurrence, resulting in higher morbidity and mortality. Mucormycosis, an opportunistic fungal infection, is caused by a group of opportunistic molds, i.e. mucormycetes, mainly found in immunosuppressed states. It is to be noted that our patient was young with no comorbidities. SARS-CoV-2 infection has been postulated to alter the immune system by affecting T lymphocytes, particularly CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, which might result in the pathological process of COVID-19 infection.[3]

The occurrence of isolated renal mucormycosis in an immunocompetent host is a rare entity. Recently in the COVID-19 pandemic, we have found increased number of cases of mucormycois in other parts of human body in India. This may be due to COVID-19 causing immunosuppression which may be the cause of aggravated response to fungal infection. Patients with chronic pulmonary disease or on corticosteroid therapy are also associated with a higher risk of invasive fungal disease. Patients with invasive fungal disease compared to those without, have higher mortality (53% vs. 31%), which can be significantly reduced by appropriate therapy.[4]

Prompt diagnosis, early surgical debridement along with systemic antifungal therapy is the standard treatment. An algorithm for the early diagnosis and management of common invasive fungal infections (Aspergillus, candidiasis, cryptococcosis, and mucormycosis) has been suggested by Song et al.[5]

CONCLUSIONS

COVID-19 has association with hypercoagulability and immune suppression, leading to thromboembolic events and opportunistic infections, so prolonged anticoagulation therapy and long-term follow-up for opportunistic infections may be essential in severely ill COVID patients.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Footnotes

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844–7. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu J, Li S, Liu J, Liang B, Wang X, Wang H, et al. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARSCoV-2 infected patients. EBioMedicine. 2020;55:102763. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White, Lewis P, et al. “A national strategy to diagnose COVID-19 associated invasive fungal disease in the ICU.” Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, ciaa1298. 29 Aug. 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song G, Liang G, Liu W. Fungal co-infections associated with global COVID-19 pandemic: A clinical and diagnostic perspective from China. Mycopathologia. 2020;185:599–606. doi: 10.1007/s11046-020-00462-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]