Abstract

Nuclear matrix attachment regions (MARs) flanking the immunoglobulin heavy chain intronic enhancer (Eμ) are the targets of the negative regulator, NF-μNR, found in non-B and early pre-B cells. Expression library screening with NF-μNR binding sites yielded a cDNA clone encoding an alternatively spliced form of the Cux/CDP homeodomain protein. Cux/CDP fulfills criteria required for NF-μNR identity. It is expressed in non-B and early pre-B cells but not mature B cells. It binds to NF-μNR binding sites within Eμ with appropriate differential affinities. Antiserum specific for Cux/CDP recognizes a polypeptide of the predicted size in affinity-purified NF-μNR preparations and binds NF-μNR complexed with DNA. Cotransfection with Cux/CDP represses the activity of Eμ via the MAR sequences in both B and non-B cells. Cux/CDP antagonizes the effects of the Bright transcription activator at both the DNA binding and functional levels. We propose that Cux/CDP regulates cell-type-restricted, differentiation stage-specific Eμ enhancer activity by interfering with the function of nuclear matrix-bound transcription activators.

The immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) locus has been studied extensively as a model of tissue-specific gene expression. Transcription of IgH is controlled by promoters, located 5′ of the individual variable (VH) gene segments, and downstream enhancer elements which cooperate to regulate tissue-restricted expression (reviewed in references 56, 66, and 84). The IgH intronic enhancer (Eμ), which is located in the intron between the joining (J) and constant (C) region gene segments, can be broken down operationally and functionally into two regions (Fig. 1): the enhancer core (1, 7, 34) and the enhancer flanking regions (75). The HinfI core restriction fragment of Eμ has binding sites for a large number of transcription factors, including the octamer transcription factors and various E-box-binding proteins (49, 53, 57, 67, 71, 72). Several of these factors can transactivate reporter gene constructs in transient transfection studies (33, 67, 84). Most of these factors are ubiquitously expressed, and yet the full-length enhancer is cell type specific in that it will activate transcription only in cells representing late stages of B-lineage differentiation. On the other hand, factors binding to the enhancer flanking regions show a more restricted expression pattern. For example, the Bright transcription activator is expressed only in mature B-lineage cells (40).

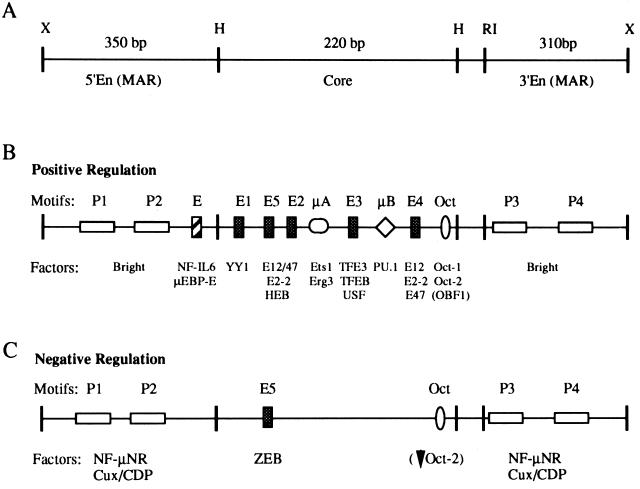

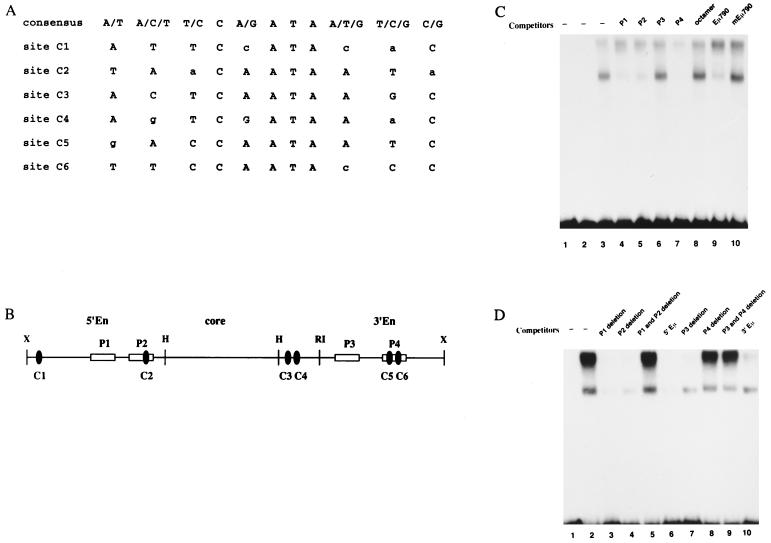

FIG. 1.

(A) Schematic showing the 991-bp IgH Eμ enhancer region and the restriction enzymes sites for XbaI (X), HinfI (H), and EcoRI (RI) used to delineate the HinfI enhancer core fragment and the flanking MARs. Components identified by various groups that have been found to activate (B) or repress (C) enhancer activity are indicated. The DNA binding site motifs and the relevant protein factors identified which bind them are indicated above and below each line, respectively. Details concerning these components can be found in the text and in reference 84.

Deletion studies have demonstrated that the Eμ core lacking the enhancer flanking regions will activate transcription in both B and non-B cells following transient transfection (42, 75, 92). This result suggests that the tissue specificity of the enhancer depends on repression in non-B cells by the enhancer flanking regions. A candidate repressor, NF-μNR (nuclear factor μ negative regulator) (Fig. 1), was first identified as an activity that binds to both flanking regions of Eμ (75). NF-μNR binding activity, demonstrated as a specific mobility shift complex, is present in non-B and early pre-B cells but absent in mature B and plasma cells. NF-μNR footprinting reveals four binding sites within the Eμ flanking regions. Deletions of the NF-μNR binding sites leads to the activation of Eμ-driven constructs which are normally repressed in non-B cells (75).

The enhancer flanking regions bound by NF-μNR correspond to two nuclear matrix attachment regions (MARs) defined by an in vitro matrix binding assay (21, 75, 99). Although originally thought of as a structural component of the nucleus, it now appears that the nuclear matrix may play an important role in the regulation of gene expression. For example, deletion of the MAR located next to the immunoglobulin kappa chain intronic enhancer (20) decreases kappa chain transcription in stable transformants (9). The observation that the NF-μNR repressor binds the Eμ-flanking MARs suggests that repression may occur by influencing nuclear matrix attachment. In support of this hypothesis, in vitro studies demonstrated that NF-μNR can inhibit nuclear matrix attachment of Eμ (99).

To further investigate the mechanism of enhancer repression, we sought to clone the NF-μNR gene. We report here the identification of NF-μNR as a homeoprotein, Cux/CDP, previously cloned as a regulator of myeloid gene expression (68, 90). We demonstrate that Cux/CDP fulfills criteria for NF-μNR identity and functions as a repressor of the Eμ enhancer through the flanking MARs. Mechanistically, Cux/CDP is able to antagonize the DNA binding and transactivation capacity of Bright, a transcription activator found in the nuclear matrix (40). The finding that a similar regulatory scheme appears to be associated with the T-cell receptor β-gene enhancer (17) suggests that differential regulation of nuclear matrix attachment may be a common mechanism of gene regulation for antigen receptor genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

EL4, a mature murine T-cell line, was split every 2 to 3 days in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone, Logan, Utah), penicillin, streptomycin, l-glutamine, minimal essential medium nonessential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, β-mercaptoethanol, and 20 mM HEPES (all from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). 293 is a permanent cell line of primary human embryonal kidney transformed by sheared human adenovirus type 5 DNA. It was grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. J558 was grown in RPMI 1640 without HEPES. Other cells were grown as described elsewhere (75).

PCR and plasmid construction.

To facilitate cloning, the N-terminal end of the Cux/CDP gene was amplified by PCR. The 5′ and 3′ primers used were 5′-TTCCGCTAGCATGTCCACCACCTCAAAACTG-3′ and 5′-GCCTGGCCTTTGAGTTTTTC-3′. PCR was performed according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.). Clone 1B1 plasmid DNA was mixed with 50 pmol of each primer, 100 mmol of deoxynucleotide triphosphates, and 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase. Samples were amplified for 35 cycles as follows: 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, 1 min of annealing at 55°C, and 2 min of extension at 72°C. After the final cycle, a 10-min extension at 72°C was performed. The 500-bp product was used for cloning into the expression construct as outlined below.

Standard molecular techniques were used in all plasmid constructions (74). Plasmid pCEP4-L contains nine amino acids of the influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) molecule upstream of the polylinker of plasmid pCEP4 (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.). pCEP4 contains the enhancer and promoter of the human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene and the hygromycin resistance gene. Cux/CDP expression plasmid pCEP4-Cux was constructed as follows. First, the original cDNA clone, 1B1, obtained from screening the expression library (described below) was digested with DraI, blunt ended by filling in with Klenow enzyme, and cut with EcoRI; a 4.0-kb fragment was recovered. Second, the 500-bp PCR product encoding the N terminus of Cux/CDP protein (including the first ATG) with an NheI site incorporated at the 5′ end was amplified, and the product was digested with NheI and EcoRI. Third, the NheI-EcoRI PCR fragment was ligated with the 4.0-kb DraI-EcoRI fragment from 1B1 into NheI and XhoI sites of pCEP4-L (the XhoI site had been blunt ended before ligation). The PCR portion of the construct was sequenced, and no mutations were found.

An XbaI fragment from pCEP4-Cux, containing the Cux/CDP gene from 1B1 and an HA tag, was subcloned into the XbaI site of pSP72 (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.). The resultant plasmid, pSP72-Cux, was used as a template for in vitro transcription and translation.

The reporter gene vector pTKCAT contains the minimal promoter of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (TK) gene upstream of the bacterial chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene (62). All CAT reporter gene constructs were generated using the XbaI site in the polylinker upstream of the TK promoter.

Screening of an expression library by using an NF-μNR binding site probe.

An oligo(dT)-primed λ-ZapII cDNA library prepared from EL4 cells was made by Stratagene Cloning Systems (La Jolla, Calif.) and screened by the method of Singh et al. (81). Briefly, 105 phage were grown on an Escherichia coli lawn at 42°C until plaques were visible (about 4 h), and then filters were overlaid and incubated at 37°C overnight. The next day, the wet filters were blocked in binding buffer (50 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% [vol/vol] Tween 20) with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk for 1 h, washed, and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature in binding buffer containing 0.25% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk, 10 μg of sheared single-stranded salmon sperm DNA per ml, 2 μg of double-stranded poly(dI-dC) per ml, and 106 cpm of end-labeled double-stranded (10/12)7. (10/12 is an NF-μNR binding site from the S107 promoter [40].) Filters were then washed three times in binding buffer with 0.25% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk, allowed to dry, and exposed to film overnight at −80°C with intensifying screens. Plaques demonstrating binding of labeled probe were then picked and purified to homogeneity by three rounds of successive screening. Two kinds of positive clones were identified; one demonstrated low-level binding for the probe, and the other demonstrated high-level binding (e.g., clone 1B1). Both were converted to double-stranded plasmids by Stratagene’s in vivo excision protocol and sequenced by using vector primers with an automated fluorescence-tagged sequencing system (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, Calif.).

In vitro transcription and translation.

The Cux/CDP protein was generated by in vitro transcribing mRNA from plasmid pSP72-Cux and in vitro translating the protein by using the TNT coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Both sense mRNA, using T7 polymerase, and antisense mRNA, using the SP6 polymerase, were synthesized from pSP72-Cux and translated. Production of nonradioactive Cux/CDP in the TNT coupled reticulocyte lysate system was confirmed and quantified by performing parallel in vitro transcription and translation reactions in the presence of [35S]methionine and analyzing the reaction products on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel. As expected, the in vitro-translated products yielded an HA-tagged Cux/CDP protein of approximately 150 kDa, using the sense but not antisense mRNA (data not shown).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and supershift assay.

Nuclear extracts of various cell lines were isolated as described elsewhere (52, 75), and protein concentrations were determined with Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). Cux/CDP protein with an HA tag was generated as described above. Typically, 1 to 2 μl (based on the translation efficiency) of the reticulocyte lysate containing in vitro-translated HA-tagged Cux/CDP was used in each binding reaction. The mobility shift assay was performed by incubating nuclear extract (0.5 to 2 μg) or in vitro-translated protein with 1 μg of poly(dI-dC) and 104 cpm of labeled probe (∼0.1 ng) in 20 μl of MSA buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 10% [vol/vol] glycerol 50 mM KCl, 0.5% [vol/vol] Tween 20, 0.2 mM EDTA) for 15 min at room temperature and then running the reaction mixture at 10 V/cm on a 4% acrylamide–5% glycerol–0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA gel. The DNA probe was a trimer of the NF-μNR P2 site end labeled with [32P]dATP (ICN, Costa Mesa, Calif.) by filling in with polymerase I Klenow fragment (74) and purified by gel electrophoresis. Double-stranded oligonucleotide P sites (P1, P2, P3, and P4) were first cloned into pUC19 plasmid, and primers specific for the plasmid were used to PCR amplify the cloned monomers. The PCR products were then gel purified. The wild-type 5′En (XbaI-PvuII) and 3′En (EcoRI-XbaI) fragments of Eμ and their deletion mutants, described previously (76), were gel purified following restriction enzyme digestion. Concentrations of competitors were determined by comparison with known amounts of standard following gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. For competition experiments, competitors were allowed to bind with the nuclear extract or in vitro-translated proteins for 5 min at room temperature before the labeled probe was added.

The supershift assay was done as described previously (68). Briefly, 0.5 to 2.0 μg of nuclear extract was first incubated either with antiserum (for antibody preincubation) or with probe (for antibody postincubation) on ice for 30 min, and then probe or antiserum, respectively, was added. The mixture was then incubated on ice for an additional 30 min, and the reactions were run on 4% native polyacrylamide gels at 4°C for 8 to 10 h.

Immunoblotting.

Guinea pig antiserum against human CDP protein was used in immunoblots as described elsewhere (68). Cell line nuclear extracts were prepared as described previously (75). All samples were resuspended in reducing buffer, boiled for 5 min, and electrophoresed on 6.5% acrylamide–0.1% SDS gels. Proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane at 4°C (100 V, 5 h). Membranes were blocked with 2.5% nonfat dry milk in TBST buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature and washed three times with 0.25% nonfat dry milk in TBST buffer. The membranes were then incubated with anti-human CDP antiserum (diluted 1:1,000) for 1 h at room temperature. Following washing of the membranes in TBST, affinity-purified goat anti-guinea pig IgG conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Sigma) was added (1:8,000 dilution), and the membranes were developed with nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (Promega).

Transfections.

A total of 2 × 107 EL4 or J558 cells in 0.5 ml of RPMI-CM medium were transiently transfected with 15 μg of reference plasmid pRSVLuciferase (22) and 20 μg of expression and reporter plasmids by electroporation using a Gene Pulser (BioRad) set at 960 mF and 280 to 300 V. The expression plasmids pCEP4 and pCEP4-Cux were used. Similar repression was also observed using pRC-CDP (59) containing the human gene. Cells were harvested 48 h later and resuspended in 0.2 ml of 0.25 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0); extracts were prepared by three cycles of freeze-thaw lysis followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C.

Stable J558L lines were prepared as previously described (93). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were selected in G418. Transient transfections of these cells with pCEP4-Cux and/or pCEP4-Bright (40) were carried out 3 to 5 weeks postselection. DNA used in transfections was prepared by the Qiagen (Santa Clara, Calif.) isolation method. All transfections were repeated a minimum of three times. For 293 cells, transfections were performed by the calcium phosphate method (74).

Luciferase and CAT assays.

Luciferase assays (14) were performed on a luminometer (MGM Instruments Inc., Hamden, Conn.) immediately after injection of 100 μl of 1 mM d-Luciferin (Sigma) into the lysate mixture. The amount of cell lysates used in one CAT assay was adjusted according to luciferase activities. CAT activity was determined by measuring the extent of acetylation of [14C]chloramphenicol (35). Labeled substrate and acetylated derivatives were separated by ascending silica gel thin-layer chromatography (CHCl3:CH3OH, 95:1). Quantitations were performed on a Betascope (Betagen Corp., Waltham, Mass.) or a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The full-length sequence of 1B1 has been submitted to the GenBank database under accession no. AF004225.

RESULTS

Protein components of purified NF-μNR.

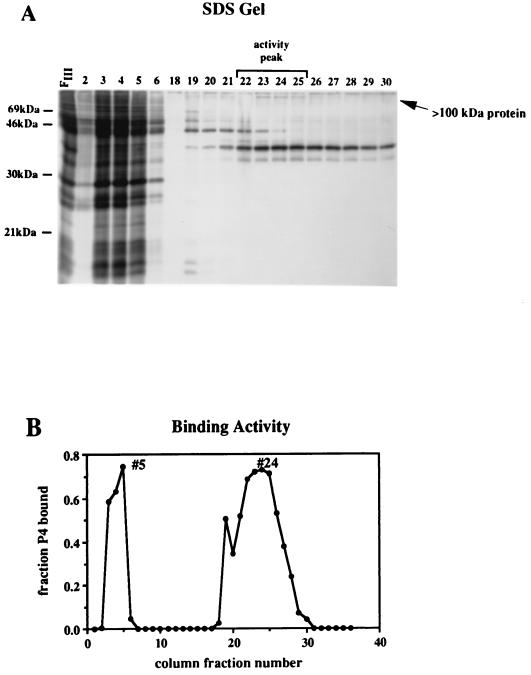

NF-μNR was purified from nuclear extracts of a pre-B-cell line (PD31) by DNA affinity chromatography with concatemerized P2 DNA (76). P2 is the strong NF-μNR binding site located within the 5′ flanking MAR of Eμ (Fig. 1). Fractions which bound to the affinity column substrate and were eluted at moderate salt concentrations contained four major proteins as visualized by silver staining following SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2A): a predominant band of ∼40 kDa and less abundant components of ∼35, ∼45, and >100 kDa. Mobility shift assays of column fractions indicated that fractions 22 to 25 contained substantial binding activity for NF-μNR binding sites, which tapered off rapidly in later fractions (Fig. 2B). Of the four proteins present in these fractions, only the concentration of the >100-kDa protein correlated with NF-μNR binding activity.

FIG. 2.

Affinity chromatography of NF-μNR. A DEAE-Sephacel column fraction pool (FIII) was preincubated with poly(dI-dC) and loaded onto a DNA affinity column containing oligomerized binding site P2. Bound proteins were eluted with a KCl gradient. (A) Denaturing gel analysis of column fractions. Proteins from affinity column fractions (25 μl) were separated on an SDS–15% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by silver staining. Fractions 2 to 6 are from the flowthrough; fractions 18 to 30 were salt eluted. (B) DNA binding activity of affinity column fractions. Column fractions (5 μl) were assayed for binding to 32P-labeled P4 site by a standard mobility shift assay. Binding activity was quantified by phosphorimaging. Fractions with peak activity (5 and 24) are indicated.

Isolation of putative NF-μNR cDNA clones by expression screening.

An EL4 (T-cell) λ-ZapII cDNA library was screened with a concatemer of a high-affinity NF-μNR binding site. From 2 × 106 plaques screened, two groups of positive clones were identified. One group, isolated four times, demonstrated low-affinity binding for the probe. Sequencing analysis and database comparisons indicated that these four clones encoded overlapping portions of the murine HMG(I)Y gene (83). Several observations argue against HMG(I)Y being a component of NF-μNR. First, although an early fraction (fraction 19) eluted from the DNA affinity column contained a protein with a molecular mass consistent with that of HMG(I)Y (∼18 kDa), other fractions with strong binding activity did not. Second, in contrast with NF-μNR (76), HMG(I)Y demonstrates relatively low affinity for its binding sites, with loose specificity for AT-rich DNA sequences (25). Third, anti-HMG(I)Y antibody (kindly provided by R. Reeves, Washington State University) did not perturb NF-μNR–DNA complexes in mobility shift assays (data not shown).

The other group of positive plaques contained an insert whose fusion protein demonstrated relatively high affinity binding for the probe. Sequencing of the 5,017-bp insert of 1B1 and database analysis indicated that 1B1 demonstrated extensive homology with the human CDP (68), the murine Cux (90), and the canine Clox (2) genes. Although isolated from mouse cells, 1B1 differs significantly from the published murine Cux cDNA at its 5′ end (Fig. 3A). 1B1 lacks the in-frame stop codons 5′ of the initiator ATG proposed by Valarché et al. (90). This extension of 195 bp at the 5′ end of 1B1 encodes an extra 65 amino acids which closely align with the 5′ end of human CDP. It now appears that the 5′ end of the published murine Cux cDNA corresponds to a fragment of a ribosomal subunit gene (67a).

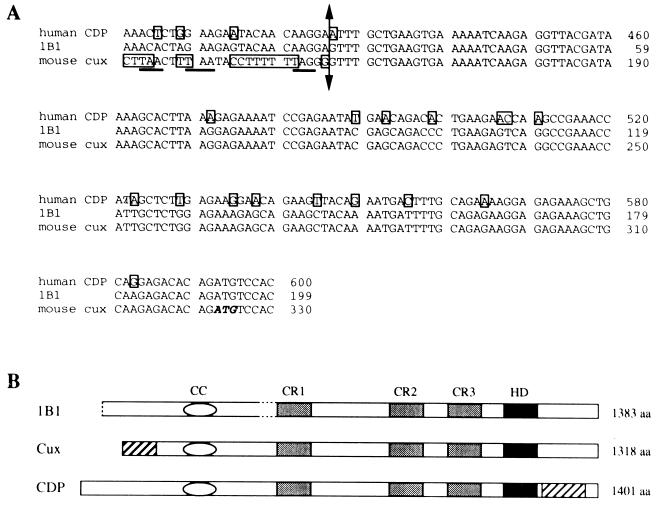

FIG. 3.

Comparison of clone 1B1 with Cut homologues. (A) The clone (1B1) identified in this study differs from published mouse Cux at its 5′ end (to the left of the double-headed arrow). The published mouse Cux sequence contains three in-frame stop codon upstream of this regions (underlined) that are not present in 1B1. The extra coding region in 1B1 is homologous to the human CDP gene. (B) Conserved domains among the mouse and human Cut homologues, including CRs, a homeodomain (HD), and coiled-coil region (CC). Regions in mouse Cux and human CDP that differ significantly from 1B1 are indicated as hatched boxes. A deletion of the 5′ half of exon 10 in 1B1 is indicated with dashed lines.

1B1 differs from the human CDP gene at a region between the homeodomain and the carboxy terminus (Fig. 3A). Here, the sequence of 1B1 is identical with the published murine sequence (except that the CG beginning at position 4212 of murine Cux is a GC in 1B1). The presence of an internal divergent region interrupting regions of high homology supports the possibility that this region represents an alternatively spliced exon (90).

In between, the sequence of 1B1 is identical to the published mouse Cux sequence and highly homologous to human CDP with the exception of a deletion immediately 5′ of the CR1 (see below) domain. The deletion begins at the 3′ end of exon 9 and extends to the middle of exon 10, where a consensus splice acceptor can be found, suggesting that 1B1 represents an alternatively spliced version of the same gene. In support of this possibility, PCR products of the expected sizes for each that hybridize to a CDP probe have been found in all cell lines tested (see Fig. 5C). In most of the cell lines tested, the relative amounts of product derived from each transcript are about the same, suggesting that the two forms are not differentially regulated. Although the structure of 1B1 differs from that of CDP, we have not found any differences in DNA binding or repression activity between these two forms (data not shown). Based on the extensive homologies with these two genes, we refer to the gene encoded by 1B1 as Cux/CDP.

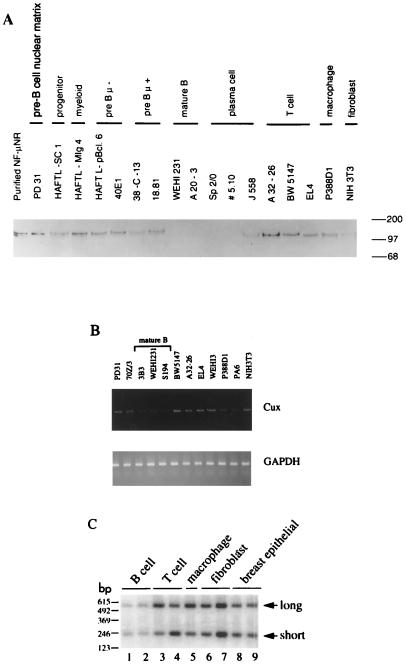

FIG. 5.

Cell-type-specific expression of Cux/CDP. (A) Expression of Cux/CDP protein. Immunoblotting was performed as described previously (68); 4 μg of nuclear extracts or nuclear matrix (lane 2 only) from various cell lines and 20 ng of affinity-purified NF-μNR were analyzed in SDS–6.5% polyacrylamide gels. Sizes are indicated in kilodaltons. (B) Expression of Cux/CDP mRNA. Total RNA was isolated, cDNA was synthesized, and PCR analysis was performed as previously described (77). Primers used to amplify Cux/CDP mRNA (TAGTAGCCATGTCTCCTGAG and CTTCAGGTTGAGTTGTGTGG) generate a 496-bp product corresponding to the CR3-homeodomain region; primers for GAPDH mRNA were described previously (77). (C) Expression of Cux/CDP alternative splice products in vivo. PCR was performed as described above except that the primers used (AAGGCCAGGCTGACTATGAAGAAG and TTGGGGAAGATATGGAGTTTGTGC) span the putative alternative splice region. After gel electrophoresis, PCR products were transferred to a Zetaprobe membrane, hybridized with a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide derived from the intervening region (CATCGGAGGGAGCAGGGACACAGG) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and analyzed by phosphorimaging. The expected product size from the published mouse Cux and human CDP sequences is 524 bp; that from the 1B1 sequence is 218 bp. The total RNA analyzed was isolated from the following types of cells (lanes 1 to 9: B cell, (3B3 and S194), T cell (BW5147 and EL4), macrophage (WEHI-3), fibroblast (PA6 and NIH 3T3), and human breast cancer (BT474 and MDA-MB231).

Specific binding of Cux/CDP to NF-μNR MAR sites.

The Cux/CDP protein has one homeodomain and three regions of 60 to 70 amino acids with strong homology to each other (CR1 to -3). These homologous sequences were first identified in the Drosophila Cut protein (10) and have been termed Cut repeats (CRs). Each CR has a unique DNA binding specificity with homology to a loosely defined CR consensus binding sequence (Fig. 4A) (5, 39). The Eμ enhancer contains six sites homologous to this CR consensus binding site (Fig. 4A). Three of these, C2, C5, and C6, overlap the two high-affinity binding sites P2 and P4 previously identified for NF-μNR within the Eμ MARs (Fig. 4B) (76).

FIG. 4.

In vitro-translated Cux/CDP protein binds the high-affinity NF-μNR binding sites in the Eμ enhancer. (A) CR consensus sequence and six homologous sites from Eμ. (B) Schematic representation of NF-μNR binding sites and Cut homologous sites within the enhancer. (C) Cux/CDP binds to P1, P2, and P4 sites. One to 2 μl of the reticulocyte lysate containing in vitro-translated Cux/CDP protein was incubated with the 32P-labeled trimer of the P2 site of NF-μNR and various competitors (lane 4 to lane 10). When included, competitor DNA was added at a 500-fold molar excess. The samples were fractionated on a 4% native polyacrylamide gel. P2 and P4 are strong NF-μNR binding sites from the Eμ enhancer. The octamer is a nonspecific competitor from Eμ. Eμ790 is the consensus cut site C5 from P4 (B), and mEμ790 is a mutated version of this site. (D) Competition by 5′En and 3′En fragments with P-site deletions. The flanking sequences of Eμ and their deletion mutants are described in the text.

To determine whether Cux/CDP would bind NF-μNR binding sites, EMSAs were performed with in vitro-translated Cux/CDP and a trimer of the P2 site as a probe. Cux/CDP binds to the P2 trimer in the presence of an excess of nonspecific competitor (Fig. 4C, lane 3) and generates two shifted complexes. It is not clear whether these Cux/CDP-specific complexes represent different stoichiometries of binding or binding of truncated proteins generated during the in vitro synthesis of the relatively large Cux/CDP. To establish the specificity of the DNA-protein interaction, unlabeled double-stranded PCR products containing monomers of the P1, P2, P3, and P4 sites (lanes 4 to 7) or the octamer site (lane 8) were used as competitors in the binding assays. P1, P2, and P4 inhibited Cux binding; P2 and P4 are the two high-affinity NF-μNR binding sites (76) which contain regions homologous to the CR consensus. The low-affinity P3 and octamer sites were unable to compete for binding under these conditions. A double-stranded oligonucleotide (Eμ790) containing the CR homologous site C5 (Fig. 4A) from the P4 NF-μNR binding site also inhibited the formation of the P2 complex (lane 9), whereas a double-stranded oligonucleotide containing a mutated version (mEμ790) of the CR homologous site C5 did not (lane 10). Thus, Cux/CDP binds to NF-μNR binding sites and demonstrates a requirement for the CR homologous sequences.

To determine if the P sites were the only high-affinity binding sites for Cux/CDP in the 5′ and 3′ MAR segments, fragments containing P-site deletions were evaluated in competition experiments (Fig. 4D). Both the wild-type 5′-Eμ and 3′-Eμ fragments compete for binding of Cux/CDP to the P2 trimer (lanes 6 and 10, respectively). A double deletion of P1 and P2 or a single deletion of P4 from the respective fragments was sufficient to abrogate competition (lanes 5 and 8). On the other hand, and consistent with the data in Fig. 4C, deletion of the low-affinity NF-μNR binding site P3 had little effect on competition (lane 7). Thus, Cux/CDP binds to the P1, P2, and P4 sites of NF-μNR; indeed, these are the only high-affinity binding sites located within the enhancer-flanking MARs. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that Cux/CDP encodes the DNA-binding component of NF-μNR.

Cell-type- and differentiation stage-restricted expression of Cux/CDP.

Previously we had shown that NF-μNR binding activity could be identified in nuclear extracts from a variety of different cell lines but was uniquely absent from the nuclear extracts of late pre-B, mature B, and plasma cells (75). Although others have shown that CDP and its homologues are expressed in a variety of cells and tissues (68, 90), expression in lymphoid cells or tissues has not been fully examined. To compare their expression patterns, we probed protein blots of nuclear extracts from a variety of murine cell lines with an antiserum raised against human CDP, which cross-reacts with murine Cux (67a). The 150- to 180-kDa Cux/CDP protein was readily detected in soluble nuclear extracts from non-B-cell lines including T (EL4, A32-26, and BW5147), macrophage (P388D1), fibroblast (NIH 3T3), and pre-B (HAFTL-pBcl6, 40E1, 38-C-13, and 18.81) cells (Fig. 5A). No Cux/CDP was detected in the mature B and plasma cell lines WEHI-231, A20-3, Sp2/0, and 5.10. The lower amount of CDP protein found by immunoblotting for J558 also correlates with the modest NF-μNR binding activity observed in these cells (75). Thus, the expression pattern of Cux/CDP closely correlates with the previously determined NF-μNR binding activities in these cells (75). On the other hand, although the pre-B-cell line 18.81 exhibited substantial amounts of CDP protein by immunoblotting, only low levels of binding activity had been observed in extracts from these cells. This finding suggests that the DNA binding activity of NF-μNR may also be regulated posttranslationally, especially as the cells transit from the early to the late pre-B-cell stages of differentiation.

Interestingly, Cux/CDP was also abundant in nuclear matrix preparations from the pre-B-cell line PD31 (Fig. 5A, lane 2). Importantly, affinity-purified NF-μNR (Fig. 2) also contains a protein of 150 to 180 kDa that reacts with the anti-human CDP antiserum (Fig. 5A, lane 1).

Cell-type-specific expression appears to be partly dictated by differential mRNA expression. PCR analysis of cDNA derived from a panel of cell lines indicates that mature B-cell lines carry lower levels of Cux/CDP RNA (Fig. 5B and C). However, significant levels are still detected both by reverse transcription-PCR (Fig. 5B and C) and RNase protection (data not shown). This observation suggests that additional posttranscriptional mechanisms may further regulate Cux/CDP protein levels in these cell types.

Cux/CDP is a component of NF-μNR.

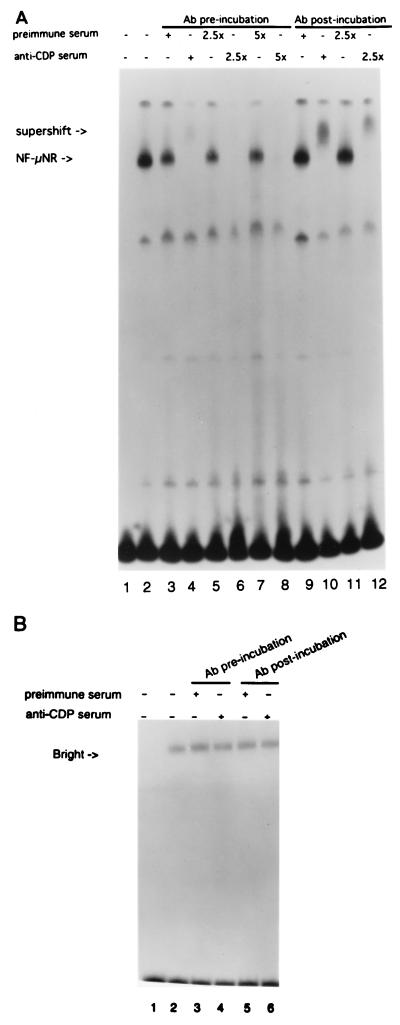

To determine if Cux/CDP is a component of the endogenous NF-μNR mobility shift complex, the effects of anti-human CDP antiserum were evaluated. If a protein recognized by the antiserum is involved in the NF-μNR protein-DNA complex, preincubation of the nuclear extract with the antiserum would potentially block this interaction. Similarly, incubation with the antiserum after the protein has been allowed to bind to the DNA probe would result in a further change or supershift in the migration of the NF-μNR–DNA complex. The antiserum raised against human CDP ablated NF-μNR complex formation under preincubation conditions (Fig. 6A, lanes 4, 6, and 8). Antiserum added subsequent to nuclear extract-probe mixture supershifted the NF-μNR complex (lanes 10 and 12). In both cases, incubation with preimmune serum had no effect. As a final specificity control, we used the same DNA probe to analyze an extract from a mature B-cell line (BCL1) devoid of NF-μNR but abundant in the activity of a B-cell-specific transcriptional activator, Bright (40). Bright binds strongly to P2 DNA under identical conditions. As shown in Fig. 6B, there was no inhibition or supershifting of the Bright complex with anti-human CDP serum. These results clearly demonstrate that Cux/CDP is a component of endogenous NF-μNR.

FIG. 6.

Anti-human CDP antiserum interacts with the NF-μNR/DNA complex. (A) EL4 nuclear extract (2 μg) was first incubated on ice with either anti-human CDP antiserum (for antibody [Ab] preincubation) or the 32P-labeled P2 trimer probe (for antibody postincubation) for 30 min. The labeled probe or the antiserum was then added, and the mixtures were incubated on ice for another 30 min. The resultant samples were separated on a 4% native polyacrylamide gel. The endogenous NF-μNR shifted complex and the supershifted complex are marked by arrows. (B) Anti-CDP pre- and postincubation using 1 μg of a nuclear extract from a B-cell line (BCL1) that lacks NF-μNR but contains a positive transactivator (Bright) that binds the same P2 sequence. No effect was found on the Bright complexes.

Cux/CDP represses Eμ-driven transcription.

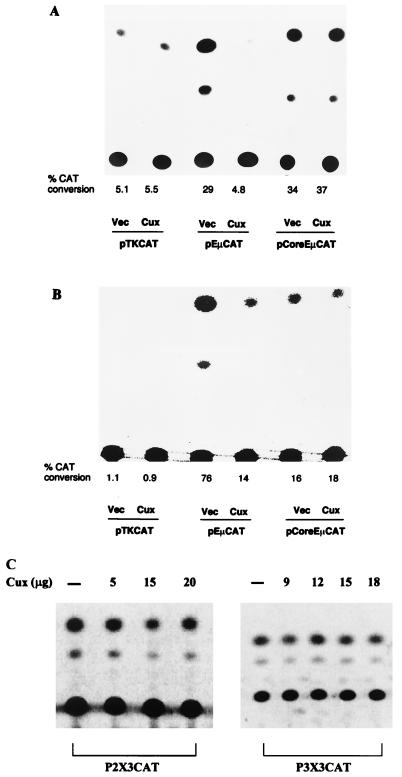

Based on functional studies of enhancers containing NF-μNR binding site deletions, NF-μNR was proposed to function as a repressor, keeping the Eμ enhancer inactive in inappropriate cells (75). To investigate whether Cux/CDP could repress the activity of Eμ, transient cotransfections were performed with Cux/CDP expression vectors and reporter gene constructs driven by various Eμ fragments. The Cux/CDP expression construct, pCEP4-Cux, contains the full-length Cux cDNA under control of the cytomegalovirus promoter and enhancer. The reporter constructs used in these studies were pTKCAT, pEμCAT, and pCoreEμCAT. pEμCAT contains the full-length Eμ enhancer fragment (Fig. 1A) cloned upstream of the minimal TK promoter in pTKCAT. pCoreEμCAT contains the core of the Eμ enhancer (Fig. 1A) cloned upstream of the TK promoter. This HinfI fragment lacks both MARs, the four P sites, and the six CR homologous sites (Fig. 4B). The T-cell line EL4 has been shown to be partially permissive for Eμ-driven reporter gene transcription following transient transfection (40). Cotransfection of EL4 with Cux/CDP strongly repressed the transcription of pEμCAT (Fig. 7A). This was not a general effect on transcription since cotransfection of Cux/CDP had no effect on basal pTKCAT expression (Fig. 7A). Repression by Cux/CDP required the Eμ-flanking MARs containing the CR homologous and NF-μNR binding sites, since cotransfection had no effect on transcription of the pCoreEμCAT construct. Thus, although EL4 expresses CDP/Cux (Fig. 5), the residual Eμ activity observed in these cells is further repressed by providing additional Cux/CDP exogenously. Identical results were obtained in cotransfection studies with another non-B-cell line, 293 (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Cux/CDP represses the MAR-containing Eμ enhancer but not the enhancer core. CAT assays were performed on cell extracts following cotransfection with the constructs described in the text. (A) Cotransfection in EL4 T cells. Vec, vector. (B) Cotransfection in J558 plasma cells. Transfection efficiency was normalized based on cotransfected luciferase activity. The percent CAT conversions indicated are averages of three or more independent transfections. (C) Cotransfection of Cux with reporter constructs carrying P-site multimers in EL4. Reporter constructs were generated by introduction of three tandem copies of sites P2 or P3 into the pTKCAT vector. The amount of Cux expression plasmid included in each transfection is indicated. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments that gave similar results.

To investigate Cux/CDP-mediated repression further, we cotransfected the Eμ reporter constructs into a plasmacytoma (J558) that contains little endogenous Cux/CDP (Fig. 5). As seen in Fig. 7B, the wild-type Eμ enhancer was significantly repressed by cotransfected Cux/CDP in J558. As in the non-B cells, repression required the presence of the flanking MARs. Cux/CDP repression has also been observed in other mature B-cell lines, including MPC11, M12, and A20-3. Interestingly, the level of enhancer activity in the absence of Cux was lower when the flanking MARs were deleted, corroborating the role of these flanking regions in transcription activation (29, 40, 43) as well as repression. Taken together, these data indicate that expression of Cux/CDP results in enhancer down-regulation in the in vitro culture systems used.

To further investigate the sequence requirements for Cux/CDP-mediated repression, cotransfection studies using reporter constructs carrying multimers of P sites were performed. Constructs carrying multimers of the strong binding site, P2, were repressed by cotransfections with various concentrations of Cux/CDP plasmid (Fig. 7C). On the other hand, constructs carrying multimers of the weak binding site, P3, were not repressed under similar conditions. Thus, sequences included in the P2 region of the enhancer-flanking MARs are sufficient for repression mediated by Cux/CDP. These results also suggest that the P3 sites, with a 2-log-lower affinity for NF-μNR binding (76), are nonfunctional on their own in vivo.

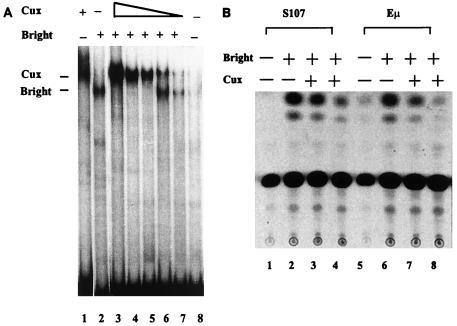

Cux/CDP abrogates MAR binding and transactivation by Bright.

When independently bound to the P sites within the Eμ MARs, Cux/CDP and Bright mediate reciprocal effects on transcription. To address the mechanism of Cux/CDP-mediated repression, we used in vitro-synthesized proteins in a series of mobility shift assays (Fig. 8A). The probe is the single binding site located within the S107 VH promoter—the sequence used to clone Cux/CDP in this study and shown previously by EMSA (40) and DNase footprinting (100) to contain overlapping binding sites for both proteins. With increasing concentrations (lanes 3 to 7) or incubation times (data not shown) of Cux/CDP, prebound Bright is quantitatively eliminated. The absence of Bright-DNA complexes in these experiments, where the DNA probe is in excess, suggests that Cux/CDP preferentially binds to DNA when it is part of this Bright-DNA complex or that it induces its dissociation.

FIG. 8.

Cux/CDP antagonizes Bright DNA binding and transactivation. (A) Abrogation of Bright binding. In vitro-synthesized Bright and Cux were used in EMSAs containing the 32P-labeled P2 binding site (1 ng) derived from the S107 promoter-associated MAR as a probe. Lane 1, 20 ng of Cux; lane 2, 20 ng of Bright; lanes 3 to 7, 20 ng of Bright with decreasing concentrations of Cux (20, 16, 12, 8, and 4 ng, respectively); lane 8, free probe. (B) Repression of Bright transactivation. J558L cells were stably transfected with CAT reporter vectors driven by either the S107 promoter or Eμ upstream of the TK promoter; their basal activities are shown in lanes 1 and 5, respectively. These stable bulk cell lines were then transiently transfected with 5 μg of a Bright expression vector alone (lanes 2 and 6) or with either 2 μg (lanes 3 and 7) or 5 μg (lanes 4 and 8) of a Cux expression vector. Reporter expression values were normalized to cotransfected luciferase activity. Transfection efficiencies ranged from 6 to 10% as measured with a green fluorescent protein expression construct.

The functional effects of Bright-Cux/CDP competition were evaluated in transfection experiments. We have found that the influence of Bright and Cux/CDP on reporter gene expression is more dramatic when the reporter constructs are integrated in the host cell genome (unpublished data). This may relate to the putative nuclear matrix involvement discussed below. Two different reporter constructs were evaluated: CAT driven by the S107 VH promoter without an enhancer (this promoter fragment includes Bright and Cux/CDP binding sites and a single MAR) and CAT driven by the TK promoter and the Eμ enhancer (40, 93). Both CAT constructs were stably transfected into J558 cells and selected with G418 for 3 to 5 weeks prior to transient transfection with Bright and Cux/CDP expression constructs. As shown in Fig. 8B, Bright transactivates the integrated S107 promoter and Eμ enhancer constructs about 15-fold above levels observed without Bright. Cotransfection with Cux/CDP abrogated Bright transactivation of the Eμ construct and significantly (three- to fivefold) reduced transactivation of the S107 construct. These results indicate that Cux/CDP repression is dominant to Bright transactivation, apparently through dominant effects at the DNA binding level.

DISCUSSION

Relationship between Cux/CDP and NF-μNR.

The data presented strongly argue that Cux/CDP is a component of NF-μNR. Antibodies raised against Cux/CDP recognize a protein in highly purified NF-μNR preparations that fractionates with NF-μNR binding activity. The same antibodies bind to preformed NF-μNR–DNA complexes and will prevent complex formation if preincubated with nuclear extracts. The expression pattern of Cux/CDP protein and the binding activity pattern of endogenous NF-μNR are virtually identical in their cell type specificity. The binding affinities for regions within the Eμ enhancer are closely similar. Finally, the repressive function of NF-μNR suggested by our previous studies and the actual repressor function of Cux/CDP on the Eμ enhancer also correlate well. It should be noted that it is possible that Cux/CDP interacts with another component to form the functional DNA binding activity characterized as NF-μNR. However, the fact that in vitro-transcribed/translated Cux/CDP exhibits the same gel shift pattern as authentic NF-μNR present in nuclear extracts indicates that if another component is involved, it must be present in rabbit reticulocyte lysates.

Mechanism of Cux/CDP-mediated Eμ repression and the genetic switch.

Repression by Cux/CDP appears to occur in part by competition with transcription activators for overlapping DNA binding sites. The B-cell-specific transcription activator Bright was found to bind with high affinity to NF-μNR sites P2 and P3 (40). In the studies described here, Cux/CDP was found to antagonize the effects of Bright. Bright contains regions homologous to the Drosophila SWI1 protein (51), suggesting that it might be involved in chromatin remodeling. Thus, Cux/CDP inhibition might prevent changes in chromatin structure necessary for transcription or recombination. In this regard, the requirement for these enhancer flanking regions to generate extended chromatin accessibility has recently been reported (44).

Cux/CDP regulation may also involve other changes related to nuclear matrix attachment. The nuclear matrix binds to both the 5′En and 3′En flanking segments that are also bound by NF-μNR/Cux/CDP (21, 75). The mechanism by which the nuclear matrix might influence transcription rates is still a matter of debate. MAR sites that flank a transcription unit might set up a torsionally constrained domain that could help maintain an unwound state during transcription (91). MARs have been suggested to alter locus demethylation (58), insulate loci from chromosomal position effects (16, 30, 89), establish transcriptional domains via physical anchorage (12, 48), or create nucleosome-altered environments (36, 43, 44, 63, 69, 86). Alternatively, perhaps attachment of a locus to the nuclear matrix brings the gene into regions of the nucleus with high concentrations of transcription factors, topoisomerases, RNA polymerases, nucleosome-remodeling proteins, etc. (38, 75, 85). The idea that tissue specificity might be regulated by differential attachment to the nuclear matrix is supported by the observation that genes that are actively transcribed are preferentially bound to the nuclear matrix in vivo (15, 32).

Regardless of the mechanism, if binding to the nuclear matrix is involved in activating transcription, repression could occur by preventing nuclear matrix attachment. Indeed, NF-μNR/Cux/CDP inhibits nuclear matrix attachment of Eμ in vitro and competes for binding of two nuclear matrix proteins, MAR-BP1 (99) and Bright (as demonstrated here). In further support of this hypothesis, a Cux/CDP binding site located adjacent to the T-cell receptor β-gene enhancer is also a functional MAR (17). In this case, competition appears to occur with the T-cell-specific SatB1 protein (23, 50). Competition models in this context predict that the MARs flanking Eμ will stimulate transcription in cells that lack Cux/CDP. This is consistent with previous studies (29, 40, 43) and our transfection results in which the core-only constructs were less active in J558 than the MAR-containing constructs (Fig. 7).

Several ubiquitous and B-cell-specific transcriptional activators and coactivators that stimulate Eμ have been cloned and studied. However, a number of experiments suggest that the cell type specificity of the Eμ enhancer is governed by negative regulatory mechanisms which are dominant to these activators. For example, fusion of B-cell lines with either fibroblasts or T cells results in the inactivation of the enhancer (46, 98). Three regions of the IgH intronic enhancer that contain negative regulatory elements have been identified. The μE5 box binds the positive-acting helix-loop-helix transcription factor ITF-1, encoded by the E2A gene, that can be functionally inactivated by dimerization with the Id protein and replacement with the displacement protein ZEB (31, 73, 94, 96). The μE4-octamer region is a target of repression apparently as a result of down-regulation of Oct-2 (47, 70, 79, 97). Finally, the regions flanking the enhancer core also repress enhancer activity through the activity of NF-μNR/Cux/CDP (42, 75).

The relationship between the different positive and negative regulatory elements is unclear. It is possible that the different elements are important for regulating different processes shown to involve the Eμ enhancer: open chromatin associated with the maintenance of IgH transcription (36); cell-type-specific changes in chromatin structure (44); changes in IgH expression in response to mitogens like lipopolysaccharide, interleukin-6, gamma interferon, and concanavalin A (19, 45, 64, 65, 80, 95); initiation of chromosomal DNA replication (3, 4, 41); and both VDJ- and switch-type recombination (18, 26, 27, 28, 37, 54, 55, 78). Each of the factors described above may play a unique role in regulating transcription, replication, or recombination.

Cux/CDP as a repressor of end-stage genes.

The mouse Cux/CDP protein is highly homologous to the human CDP protein (68) and Drosophila Cut protein (10). The Cut locus of Drosophila controls cell identity in several organs. Mutations of the Cut locus result in the transformation of the neurons and support cells of the external sensory organs into those of the chordotonal organs in Drosophila (13). Ectopic expression of Cut in Drosophila embryos results specifically in the morphologic and antigenic transformation of chordotonal organs into external sensory organs (11).

Investigators studying diverse developmental systems have found that CDP and its homologues serve as repressors of different genes (2, 8, 24, 59, 61, 82, 88, 90). The binding of these proteins to promoters of tissue-specific genes appears to be limited to tissues or developmental stages where the target genes are not expressed. With terminal differentiation, Cux/CDP proteins lose the ability to bind to tissue-specific promoters, and transcription of the target genes is activated. Targets reported for this group of proteins include the promoters for the γ-globin (87, 88), c-Myc (24), myosin heavy chain (2), neural cell adhesion molecule (90), CD8a (6), mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat (60), and myelomonocyte-specific gp91-phox (82) genes. More recently, Cux/CDP has been found to bind to a differentiation stage-specific DNase-hypersensitive site located near the T-cell receptor β-gene enhancer that can mediate repression of this enhancer in transfection studies (17). The results described here indicate that Cux/CDP functions as a repressor of another end-stage gene in a different differentiation pathway, the IgH gene in B-lineage differentiation. Thus, Cux/CDP may serve a more general function as a regulator of genes expressed in late stages of differentiation in multiple lineages.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

R.H.S. and P.W.T. are co-senior authors.

We thank Rick Herrscher and Jilian Cai for suggestions, Ray Reeves for anti-HMG(I)Y antibody, the Tucker lab for help and support, U. Das and K. Rice for help with preparation of the manuscript, M. Levine for critical review of the manuscript, and J. Chen for communication of unpublished results.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants GM50329 to R.H.S., HL49196 to E.J.N., and CA31534 and GM31689 to P.W.T. E.J.N. is a fellow of the Lucille P. Markey Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams J M, Harris A W, Pinkert C A, Corcoran L M, Alexander W S, Cory S, Palmiter R D, Brinster R L. The c-myc oncogene driven by immunoglobulin enhancers induces lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice. Nature. 1985;318:533–541. doi: 10.1038/318533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrés V, Nadal-Ginard B, Mahdavi V. Clox, a mammalian homeobox gene related to Drosophila cut, encodes DNA-binding regulatory proteins differentially expressed during development. Development. 1992;116:321–334. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ariizumi K, Wang Z, Tucker P W. Immunoglobulin heavy chain enhancer is located near or in an initiation zone of chromosomal DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3695–3699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ariizumi K, Ghosh M R, Tucker P W. Elements in the immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer directly regulate simian virus 40 ori-dependent DNA replication. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5629–5636. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aufiero B, Neufeld E J, Orkin S. Sequence specific DNA binding of individual cut repeats of the human CCAAT displacement/cut homeodomain protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7757–7761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banan M, Rojas I C, Lee W H, King H L, Harriss J V, Kobayashi R, Webb C F, Gottlieb P D. Interaction of the nuclear matrix-associated region (MAR)-binding proteins, SATB1 and CDP/Cux, with a MAR element (L2a) in the upstream regulatory region of the mouse CD8a gene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18440–18452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banerji J, Olson L, Schaffner W. A lymphocyte-specific cellular enhancer is located downstream of the joining region in immunoglobulin heavy chain genes. Cell. 1983;33:729–740. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barberis A, Superti-Furga G, Busslinger M. Mutually exclusive interaction of the CCAAT-binding factor and of a displacement protein with overlapping sequences of a histone gene promoter. Cell. 1987;50:347–359. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90489-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blasquez V C, Xu M, Moses S C, Garrard W T. Immunoglobulin kappa gene expression after stable integration. I. Role of the intronic MAR and enhancer in plasmacytoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:21183–21189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blochlinger K, Bodmer R, Jack J W, Jan L Y, Jan Y N. Primary structure and expression of a product from cut, a locus involved in specifying sensory organ identity in Drosophila. Nature. 1988;333:629–635. doi: 10.1038/333629a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blochlinger K, Jan L Y, Jan Y N. Transformation of sensory organ identity by ectopic expression of Cut in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1124–1135. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.7.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bode J, Maass K. Chromatin domain surrounding the human interferon-β gene as defined by scaffold-attached regions. Biochemistry. 1988;27:4706–4711. doi: 10.1021/bi00413a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodmer R, Barbel S, Sheperd S, Jack J W, Jan L Y, Jan Y N. Transformation of sensory organs by mutations of the cut locus of D. melanogaster. Cell. 1987;51:293–307. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brasier A R, Tate J E, Habener J E. Optimized use of the firefly luciferase assay as a reporter gene in mammalian cell lines. BioTechniques. 1989;7:1116–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brotherton T, Zenk D, Kahanic S, Reneker J. Avian nuclear matrix proteins bind very tightly to cellular DNA of the β-globin gene enhancer in a tissue-specific fashion. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5845–5850. doi: 10.1021/bi00238a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai H, Levine M. Modulation of enhancer-promoter interactions by insulators in the Drosophila embryo. Nature. 1995;376:533–536. doi: 10.1038/376533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chattopadhyay S, Whitehurst C E, Chen J. A nuclear matrix attachment region upstream of the T cell receptor beta gene binds Cux/CDP and SatB1 and modulates enhancer-dependent reporter gene expression but not endogenous gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29838–29846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J, Young F, Bottaro A, Stewart V, Smith R K, Alt F W. Mutations of the intronic IgH enhancer and its flanking sequences differentially affect accessibility of the JH locus. EMBO J. 1993;12:4635–4645. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen U, Scheuermann R H, Wirth T, Gerster T, Roeder R G, Harshman K, Berger C. Anti-IgM antibodies down modulate μ-enhancer activity and OTF2 levels in LPS-stimulated mouse splenic B-cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5981–5989. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.21.5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cockerill P N, Garrard W T. Chromosomal loop anchorage of the kappa immunoglobulin gene occurs next to the enhancer in a region containing topoisomerase II sites. Cell. 1986;44:273–282. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90761-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cockerill P N, Yuen M-H, Garrard W T. The enhancer of the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus is flanked by presumptive chromosomal loop anchorage elements. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5394–5397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Wet J R, Wood K V, Deluca M, Helinski D R, Subramani S. Firefly luciferase gene: structure and expression in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:725–737. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.2.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dickinson L A, Joh T, Kohwi Y, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. A tissue specific MAR/SAR DNA-binding protein with unusual binding site recognition. Cell. 1992;70:631–645. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90432-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dufort D, Nepveu A. The human cut homeodomain protein represses transcription from the c-myc promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4251–4257. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elton T S, Nissen M S, Reeves R. Specific A · T DNA sequence binding of RP-HPLC purified HMG-I. Biochem Biophy Res Commun. 1987;143:260–265. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90659-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernex C, Caillol D, Capone M, Krippl B, Ferrier P. Sequences affecting the V(D)J recombinational activity of the IgH intronic enhancer in a transgenic substrate. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:792–798. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.5.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernex C, Capone M, Ferrier P. The V(D)J recombinational and transcriptional activities of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain intronic enhancer can be mediated through distinct protein-binding sites in a transgenic substrate. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3217–3226. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrier P, Krippl B, Blackwell T K, Furley A J, Suh H, Winoto A, Cook W D, Hood L, Costantini F, Alt F W. Separate elements control DJ and VDJ rearrangement in a transgenic recombination substrate. EMBO J. 1990;9:117–125. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forrester W C, van Genderen C, Jenuwein T, Grosschedl R. Dependence of enhancer-mediated transcription of the immunoglobulin μ gene on nuclear matrix attachment regions. Science. 1994;265:1221–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.8066460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gasser S M, Laemmli U K. Cohabitation of scaffold binding regions with upstream/enhancer elements of three developmentally regulated genes of D. melanogaster. Cell. 1986;46:521–530. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90877-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Genetta T, Ruezinsky D, Kadesch T. Displacement of an E-box-binding repressor by basic helix-loop-helix proteins: implications for B-cell specificity of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6153–6163. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerdes M G, Carter K C, Moen P T, Jr, Lawrence J B. Dynamic changes in the higher-level chromatin organization of specific sequences revealed by in situ hybridization to nuclear halos. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:289–304. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.2.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerster T, Balmaceda C-G, Roeder R G. The cell type-specific transcription factor OTF-2 has two domains required for the activation of transcription. EMBO J. 1990;9:1635–1643. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gillies S D, Morrison S L, Oi V T, Tonegawa S. A tissue-specific transcription enhancer element is located in the major intron of a rearranged immunoglobulin heavy chain gene. Cell. 1983;33:717–728. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gorman T V, Moffat L F, Howard B H. Recombinant genomes which express chloramphenicol acetyltransferase in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:1044–1051. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.9.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grosschedl R, Marx M. Stable propagation of the active transcriptional state of an immunoglobulin μ gene requires continuous enhancer function. Cell. 1988;55:645–654. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90223-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu H, Zou Y R, Rajewsky K. Independent control of immunoglobulin switch recombination at individual switch regions evidenced through Cre-loxP-mediated gene targeting. Cell. 1993;73:1155–1164. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90644-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haaf T, Schmid M. Chromosome topology in mammalian interphase nuclei. Exp Cell Res. 1991;192:325–332. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90048-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harada R, Dufort D, Denis-Larose C, Nepveu A. Conserved cut repeats in the human cut homeodomain protein function as DNA binding domains. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2062–2067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herrscher R F, Kaplan M H, Lelsz D L, Das C, Scheuermann R H, Tucker P W. The immunoglobulin heavy-chain matrix-associating regions are bound by Bright: a B cell-specific trans-activator that describes a new DNA-binding protein family. Genes Dev. 1995;9:3067–3082. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.24.3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iguchi-Ariga S M, Ogawa N, Ariga H. Identification of the initiation region of DNA replication in the murine immunoglobulin heavy chain gene and possible function of the octamer motif as a putative DNA replication origin in mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1172:73–81. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(93)90271-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Imler J-I, Lemaire C, Wasylyk C, Wasylyk B. Negative regulation contributes to tissue specificity of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2558–2567. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.7.2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jenuwein T, Forrester W C, Qiu R-G, Grosschedl R. The immunoglobulin μ enhancer core establishes local factor access in nuclear chromatin independent of transcriptional stimulation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2016–2032. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jenuwein T, Forrester W C, Fernandez-Herrero L A, Laible G, Dull M, Grosschedl R. Extension of chromatin accessibility by nuclear matrix attachment regions. Nature. 1997;385:269–272. doi: 10.1038/385269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johansson K, Sigvardsson M, Leanderson T. Transcriptional regulation of immunoglobulin gene expression by anti-Ig. Int Immunol. 1994;6:41–48. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Junker S, Nielsen V, Matthias P, Picard D. Both immunoglobulin promoter and enhancer sequences are targets for suppression in myeloma-fibroblast hybrid cells. EMBO J. 1988;7:3093–3098. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Junker S, Pedersen S, Schreiber E, Matthias P. Extinction of an immunoglobulin κ promoter in cell hybrids is mediated by the octamer motif and correlates with suppression of Oct-2 expression. Cell. 1990;61:467–474. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90528-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kellum R, Schedl P. A position-effect assay for boundaries of higher order chromosomal domains. Cell. 1991;64:941–950. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90318-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kiledjian M, Su L-K, Kadesch T. Identification and characterization of two functional domains within the murine heavy-chain enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:145–152. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kohwi-Shigematsu T, Kohwi Y. Torsional stress stabilizes extended base unpairing in suppressor sites flanking immunoglobulin heavy chain enhancer. Biochemistry. 1990;29:9551–9560. doi: 10.1021/bi00493a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kwon H, Imbalzano A N, Khavari P A, Kingston R E, Green M R. Nucleosome disruption and enhancement of activator binding by a human SWI/SNF complex. Nature. 1994;370:477–481. doi: 10.1038/370477a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee K A W, Bindereif A, Green M R. A small-scale procedure for preparation of nuclear extracts that support efficient transcription and pre-mRNA splicing. Gene Anal Tech. 1988;5:22–31. doi: 10.1016/0735-0651(88)90023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lenardo M, Pierce J W, Baltimore D. Protein-binding sites in Ig gene enhancers determines the transcriptional activity and inducibility. Science. 1987;236:1573–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.3109035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leung H, Maizels N. Transcriptional regulatory elements stimulate recombination in extrachromosomal substrates carrying immunoglobulin switch-region sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4154–4158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leung H, Maizels N. Regulation and targeting of recombination in extrachromosomal substrates carrying immunoglobulin switch region sequences. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1450–1458. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Libermann T A, Baltimore D. Transcriptional regulation of immunoglobulin gene expression. Mol Aspects Cell Regul. 1991;6:385–421. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Libermann T A, Baltimore D. π, a pre-B-cell-specific enhancer element in the immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5957–5969. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.5957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lichtenstein M, Keini G, Bergman Y. B cell-specific demethylation: a novel role for the intronic kappa chain enhancer sequence. Cell. 1994;76:913–923. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lievens P M J, Donady J J, Tufarelli C, Neufeld E J. Repressor activity of CCAAT displacement protein in HL-60 myeloid leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12745–12750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu J, Bramblett D, Zhu Q, Lozano M, Kobayashi R, Ross S R, Dudley J P. The matrix attachment region-binding protein SATB1 participates in negative regulation of tissue-specific gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5275–5287. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu S, Mcleod E, Jack J. Four distinct regulatory regions of the cut locus and their effect on the cell type specification in Drosophila. Genetics. 1991;127:151–159. doi: 10.1093/genetics/127.1.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luckow B, Schütz G. CAT constructions with multiple unique restriction sites for the functional analysis of eukaryotic promoters and regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:5490–5495. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.13.5490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McKnight R A, Shamay A, Sankaran L, Wall R J, Hennighausen L. Matrix-attachment regions can impart position-independent regulation of a tissue-specific gene in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6943–6947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miller A E, Ennist D L, Ozato K, Westphal H. Activation of immunoglobulin control elements in transgenic mice. Immunogenetics. 1992;35:24–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00216623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Motomura M, Kitamura D, Araki K, Maeda H, Kudo A, Watanabe T. The cis-acting regulatory elements of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene involved in enhanced immunoglobulin production after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation. Mol Immunol. 1987;24:759–764. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(87)90059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nelsen B, Sen R. Regulation of immunoglobulin gene transcription. Int Rev Cytol. 1992;133:121–149. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61859-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nelsen B, Tian G, Erman B, Gregoire J, Maki R, Graves B, Sen R. Regulation of lymphoid-specific immunoglobulin μ heavy chain gene enhancer by ETS-domain proteins. Science. 1993;261:82–86. doi: 10.1126/science.8316859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67a.Neufeld, E. J. Unpublished data.

- 68.Neufeld E J, Skalnik D G, Lievens P M-J, Orkin S H. Human CCAAT displacement protein is homologous to the Drosophila homeoprotein, cut. Nat Genet. 1992;1:50–55. doi: 10.1038/ng0492-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Phi-Van L, von Kries J P, Ostertag W, Stratling W H. The chicken lysozyme 5′ matrix attachment region increases transcription from a heterologous promoter in heterologous cells and dampens position effects on the expression of transfected genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:2302–2307. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.5.2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Radomska H S, Shen C-P, Kadesch T, Eckhardt L A. Constitutively expressed Oct-2 prevents immunoglobulin gene silencing in myeloma × T cell hybrids. Immunity. 1994;1:623–634. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rivera R R, Stuiver M H, Steenbergen R, Murre C. Ets proteins: new factors that regulate immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7163–7169. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.11.7163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roman C, Platero J S, Shuman J, Calame K. Ig/EBP-1: a ubiquitously expressed immunoglobulin enhancer binding protein that is similar to C/EBP and heterodimerizes with C/EBP. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1404–1415. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.8.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ruezinsky D, Beckmann H, Kadesch T. Modulation of the IgH enhancer’s cell type specificity through a genetic switch. Genes Dev. 1991;5:29–37. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scheuermann R H, Chen U. A developmental-specific factor binds to suppressor sites flanking the immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1255–1266. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.8.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Scheuermann R H. The tetrameric structure of NF-μNR provides a mechanism for cooperative binding to the immunoglobulin heavy chain μ enhancer. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:624–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Scheuermann R H, Bauer S R. Polymerase chain reaction-based mRNA quantification using an internal standard: analysis of oncogene expression. Methods Enzymol. 1993;218:446–473. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)18035-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Serwe M, Sablitzky F. V(D)J recombination in B cell is impaired but not blocked by targeted deletion of the immunoglobulin heavy chain intronic enhancer. EMBO J. 1993;12:2321–2327. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shen L, Lieberman S, Eckhardt L A. The octamer/μE4 region of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer mediates gene repression in myeloma × T-lymphoma hybrids. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3530–3540. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sigurdardottir D, Sohn J, Kass J, Selsing E. Regulatory regions 3′ of the immunoglobulin heavy chain intronic enhancer differentially affect expression of a heavy chain transgene in resting and activated B cells. J Immunol. 1995;154:2217–2225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Singh H, LeBowitz J H, Baldwin A S, Sharp P A. Molecular cloning of an enhancer binding protein: isolation by screening of an expression library with a recognition site DNA. Cell. 1988;52:415–423. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Skalnik D G, Strauss E C, Orkin S H. CCAAT displacement protein as a repressor of the myelomonocytic-specific gp91-phox gene promoter. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:16736–16744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Solomon M J, Strauss F, Varshavsky A. A mammalian high mobility group protein recognizes any stretch of six A · T base pairs in duplex DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1276–1280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.5.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Staudt L M, Lenardo M J. Immunoglobulin gene transcription. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:373–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stein G S, Lian J B, Dworetzky S I, Owen T A, Bortell R, Bidwell J P, van Wijnen A J. Regulation of transcription-factor activity during growth and differentiation: involvement of the nuclear matrix in concentration and localization of promoter binding proteins. J Cell Biochem. 1991;47:300–305. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240470403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stief A, Winter D M, Stratling W H, Sippel A E. A nuclear DNA attachment element mediates elevated and position-independent gene activity. Nature. 1989;341:343–345. doi: 10.1038/341343a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Superti-Furga G, Barberis A, Schaffner G, Busslinger M. The −117 mutation in Greek HPFH affects the binding of three nuclear factors to the CCAAT regions of the γ-globin gene. EMBO J. 1988;7:3099–3107. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Superti-Furga G, Barberis A, Schreiber E, Busslinger M. The protein CDP, but not CP1, footprints on the CCAAT region of the γ-globin gene in unfractionated B-cell extracts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;1007:237–242. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(89)90046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Talbot D, Collis P, Antoniou M, Vidal M, Grosveld F, Greaves D R. A dominant control region from the human β-globin locus conferring integration site-independent gene expression. Nature. 1989;338:352–355. doi: 10.1038/338352a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Valarché I, Tissier-Seta J-P, Hirsch M-R, Martinez S, Goridis C, Brunet J-F. The mouse homeodomain protein Phox2 regulates Ncam promoter activity in concert with Cux/CDP and is a putative determinant of neurotransmitter phenotype. Development. 1993;119:881–896. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.3.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang J C, Lynch A S. Transcription and DNA supercoiling. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:764–768. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wasylyk C, Wasylyk B. The immunoglobulin heavy-chain B-lymphocyte enhancer efficiently stimulates transcription in non-lymphoid cells. EMBO J. 1986;5:553–560. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Webb C F, Das C, Eaton S, Calame K, Tucker P W. Novel protein-DNA interactions associated with increased immunoglobulin transcription in response to antigen plus interleukin-5. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5197–5205. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Weinberger J, Jat P S, Sharp P A. Localization of a repressive sequence contributing to B-cell specificity in the immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:988–992. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.2.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Williams M, Maizels N. LR1, a lipopolysaccharide-responsive factor with binding sites in the immunoglobulin switch regions and heavy-chain enhancer. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2353–61. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12a.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wilson R B, Kiledjian M, Shen C-P, Benezra R, Zwollo P, Dymecki S M, Desiderio S V, Kadesch T. Repression of immunoglobulin enhancers by the helix-loop-helix protein Id: implications for B-lymphoid-cell development. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:6185–6191. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.12.6185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yu H, Porton B, Shen L, Eckhardt L A. Role of the octamer motif in hybrid cell extinction of immunoglobulin gene expression: extinction is dominant in a two enhancer system. Cell. 1989;58:441–448. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90425-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zaller D M, Yu H, Eckhardt L A. Genes activated in the presence of an immunoglobulin enhancer or promoter are negatively regulated by a T-lymphoma cell line. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:1932–1939. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.5.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zong R T, Scheuermann R H. Mutually exclusive interaction of a novel matrix attachment region binding protein and NF-μNR enhancer repressor: implications for regulation of immunoglobulin heavy-chain expression. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24010–24018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zong, R. T., and R. H. Scheuermann. Unpublished results.