Abstract

Excessive free fatty acids (FFAs) causes reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) development. Garcinia cambogia (G. cambogia) is used as an anti-obesity supplement, and its protective potential against NAFLD has been investigated. This study aims to present the therapeutic effects of G. cambogia on NAFLD and reveal underlying mechanisms. High-fat diet (HFD)-fed mice were administered G. cambogia for eight weeks, and steatosis, apoptosis, and biochemical parameters were examined in vivo. FFA-induced HepG2 cells were treated with G. cambogia, and lipid accumulation, apoptosis, ROS level, and signal alterations were examined. The results showed that G. cambogia inhibited HFD-induced steatosis and apoptosis and abrogated abnormalities in serum chemistry. G. cambogia increased in NRF2 nuclear expression and activated antioxidant responsive element (ARE), causing induction of antioxidant gene expression. NRF2 activation inhibited FFA-induced ROS production, which suppressed lipogenic transcription factors, C/EBPα and PPARγ. Moreover, the ability of G. cambogia to inhibit ROS production suppressed apoptosis by normalizing the Bcl-2/BAX ratio and PARP cleavage. Lastly, these therapeutic effects of G. cambogia were due to hydroxycitric acid (HCA). These findings provide new insight into the mechanism by which G. cambogia regulates NAFLD progression.

Keywords: Garcinia cambogia, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), steatosis, apoptosis, reactive oxygen species, antioxidant, NRF2, hydroxycitric acid

1. Introduction

Obesity is a chronic disease resulting from an energy imbalance caused by hypercaloric food intake and insufficient energy expenditure [1] and is strongly associated with type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [2]. NAFLD is the most common chronic liver disease in western societies and is well recognized as the hepatic manifestation of metabolic disease [3]. NAFLD is characterized by excessive fat accumulation in hepatocytes and is strongly associated with obesity and energy imbalance [4]. If this pathological state is not properly treated, it can progress to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and continue to progress to cirrhosis and ultimately to hepatocellular carcinoma [5].

NAFLD is a various factorial disease associated with genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors [6]. Although its pathogenesis is still not entirely clear, the “two-hit hypothesis” proposes an explanation for the development of NAFLD [7]. The first hit results from insulin resistance, which causes an imbalance between hepatic lipid influx and clearance [8]. The second hit involves the perturbation of redox homeostasis, causing reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. Redox imbalance leads to hepatic mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammatory and oxidative processes [9]. An updated theory is the “multiple-hit” hypothesis, which proposes the involvement of a number of factors, including insulin resistance, inflammation, and oxidative stress [10]. One of the factors that contribute to the “multiple-hit” is oxidative stress, which is considered the main contributor to the progression of NAFLD [11]. Oxidative stress is an important cause of NAFLD, and regulation of ROS generation is one important therapeutic strategy.

Excessive accumulation of free fatty acids (FFAs) due to the intake of high-calorie food induces ROS production, and abnormal levels of ROS can mediate the progression of NAFLD, causing a breakdown of lipid homeostasis via upregulation of lipogenic genes [12,13,14]. In addition, ROS can cause apoptosis of hepatocytes and increase liver damage to promote the progression of NAFLD by inducing mitochondrial dysfunction [12]. Thus, several studies have reported that antioxidants have therapeutic effects on NAFLD by scavenging ROS and inhibiting de novo lipogenesis and apoptosis via regulating related signaling pathways [15,16,17]. Phloroglucinol, a phenolic compound of natural origin, attenuates palmitic acid and hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage and reduced steatosis in HepG2 cells via strengthening the enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidants barriers [18]. Berberine, an isoquinoline quaternary alkaloid majorly extracted from a Chinese herb named Coptis chinensis, ameliorates non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis via reducing nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 2 (Nox2)-dependent cytoplasmic ROS production and mitochondrial ROS production [19].

Normal cells can maintain oxidative homeostasis due to the operation of antioxidant defense systems [20]. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2), which is a transcription factor and binds to the antioxidant response element (ARE), activates cellular antioxidant response by inducing the transcription of antioxidant genes, such as heme oxygenase 1 (HMOX1) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) to regulate oxidative stress [21]. Notably, NRF2 has been demonstrated to contribute to the suppression of NAFLD by negative regulation of lipogenic gene expression [22]. Furthermore, NRF2 overexpression increased antiapoptotic mitochondrial protein Bcl-2, implying attenuation of oxidative and apoptotic response [23]. Therefore, the regulation of NRF2 not only controls oxidative stress but also ameliorates NAFLD development, which is a potential therapeutic target to protect from liver disease.

Garcinia cambogia (G. cambogia) is a fruit that is native to Southeast Asia and is currently used as a weight-loss supplement [24]. There are many studies suggesting the anti-obesity effect of G. cambogia mediated by an increase in fat oxidation [25], a decrease in de novo lipogenesis [26], and inhibition of mitotic clonal expansion (MCE) in the early stage of adipocyte differentiation [27]. Interestingly, G. cambogia reduced liver weight gain, vacuolization, and lipid droplet numbers in the liver tissues of high-fat diet (HFD)-fed mice, implying a therapeutic effect on NAFLD [28,29]. Despite these findings, the underlying mechanisms and interactions of signaling mediators by which G. cambogia inhibits NAFLD remains poorly understood.

In this study, we investigated the therapeutic effects of G. cambogia on HFD-fed liver tissues and FFA-treated HepG2 cells. Our findings show the inhibitory effect of G. cambogia on NAFLD through suppressing HFD- and FFA-induced steatosis and apoptosis. These effects were due to an increase of NRF2-mediated attenuation of hepatic lipogenic gene transcription and apoptosis-related signal transduction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents, Chemicals, and Antibodies

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), penicillin/streptomycin, and trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) were obtained from Gibco, Inc. (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Sodium oleate, sodium palmitate, oil red O, isopropanol, (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), digitonin, N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), anti-rabbit-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC, F0382), and potassium hydroxycitrate tribasic monohydrate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Bovine serum albumin was obtained from Bovogen Biologicals (Melbourne, Australia). Anti-C/EBPα (8178), anti-PPARγ (2443), anti-BAX (2772), anti-PARP (9532), anti-NRF2 (12721), anti-Lamin A/C (4777), and goat anti-rabbit (7074) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Anti-Bcl-2 (sc-7382) antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA). Anti-β-actin (LF-PA0207) and goat anti-mouse (LF-SA8001) antibodies were purchased from Abfrontier (Geumcheon, Seoul, Korea). Garcinia cambogia (G. cambogia) powder (main component: hydroxycitric acid, 59.55%) was obtained from Mirae Biotech, Inc. (Pocheon, Gyeonggi-do, Korea). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

2.2. Animals and Diet

Four-week-old male C57BL/6N mice (average weight, 22 g) were obtained from Orient Bio Inc. (Seongnam, Korea). The animals were provided normal chow and water ad libitum in the animal facility under controlled temperature (22 ± 2 °C), humidity (50 ± 5%), and lighting (12/12 h dark/light cycle, lights on at 7:00 a.m.) conditions. After a 1-week acclimatization period, animal experiments were performed by minimizing the use of the animals and their discomfort according to procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chungnam National University (2019012A-CNU-190) and the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines [30].

To induce obesity, mice were randomly divided into five groups (n = 7 per group): normal diet (ND, control), high-fat diet (HFD), HFD + 200 mg/kg G. cambogia (HFD + Ga 200), HFD + 400 mg/kg G. cambogia (HFD + Ga 400) and HFD + 20 mg/kg orlistat (HFD + Orli 20, positive control of anti-obesity [31] and anti-steatosis [32,33]). The control group mice were fed an ND (10% kcal fat, 20% kcal protein, 70% kcal carbohydrate, 3.82 kcal/g, R12450B, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA), and the HFD group mice were fed a high-fat diet (40% kcal fat, 17% kcal protein, 43% carbohydrate, 4.67 kcal/g, R12079B, Research Diets) ad libitum with free access to water for 8 weeks. Mice were administered G. cambogia or orlistat dissolved in 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) orally every day. The weight gains from initial and final body weights are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Body weight and biochemical markers of animal models (n = 7 per group).

| Body Weight (g) | ND | HFD | HFD + Ga 200 | HFD + Ga 400 | HFD + Orli 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g, initial time) | 22.29 ± 0.92 | 23.51 ± 1.09 | 23.27 ± 0.73 | 22.89 ± 1.08 | 22.57 ± 0.76 |

| Body weight (g, finish time) | 27.56 ± 1.38 | 34.07 ± 1.37 ** | 31.54 ± 2.20 | 29.27 ± 0.70 ## | 28.81 ± 1.96 ## |

| Weight gain | 5.27 ± 1.48 | 10.56 ± 1.31 ** | 8.27 ± 2.38 | 6.39 ± 1.04 ## | 6.24 ± 1.29 ## |

| ALT (U/I) | 53.00 ± 7.14 | 84.69 ± 21.61 ** | 63.33 ± 8.76 # | 53.33 ± 6.83 ## | 54.79 ± 7.76 ## |

| AST (U/I) | 73.50 ± 6.82 | 100.2 ± 10.97 ** | 82.50 ± 11.29 # | 75.83 ± 5.85 ## | 77.83 ± 4.02 ## |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 86.42 ± 38.00 | 215.2 ± 30.96 ** | 130.0 ± 33.76 ## | 113.3 ± 19.66 ## | 173.7 ± 42.58 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 140.0 ± 7.07 | 240.2 ± 25.93 ** | 201.7 ± 14.38 # | 180.8 ± 14.63 ## | 168.0 ± 27.28 ## |

** p < 0.01 vs. ND, # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 vs. HFD. Data are mean ± S.D.

2.3. Dosage Information

The dosages of G. cambogia were determined by consideration of the equivalent conversion of human dose [34] for a mouse model [35] and several studies, including an animal model [36,37]. The dosages of G. cambogia used for weight loss range from 1667 to 4668 mg (taken in divided doses) daily for 60 kg humans [34], and the G. cambogia dose for a mouse model based on a conversion of these dose regiment ranges from 307.5 to 947.1 mg/kg daily [35]. Considering dosages of other studies (200–250 mg/kg) [36,37], low dose (200 mg/kg) and high dose (400 mg/kg) were determined. In addition, the dosage of orlistat was determined similar to G. cambogia. The dosages of orlistat used for weight loss range from 180 to 360 mg (taken in divided doses) daily for 60 kg humans [38], and the orlistat dose for a mouse model based on a conversion of these dose regiments ranges from 32.2 to 64.4 mg/kg daily. Considering dosages of other studies (10 mg/kg) [39], orlistat dosage (20 mg/kg) was determined.

2.4. Histological Analysis

At the end of the experimental period, all animals were fasted overnight and anesthetized by CO2 administration. After the mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, liver, heart, spleen, lung, and kidney tissues were collected, weighed, rinsed, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. The tissues were cut into 4-μm-thick sections. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological examination, and images were acquired using a microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti, Nikon Instruments Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The scale bars in the images represent 50 μm. The degree of steatosis was quantified as described previously [40]. Briefly, macrovesicular steatosis (vacuoles displaced the nucleus to the side) and microvesicular steatosis (vacuoles not displaced around the nucleus) were both separately scored, and the severity was graded based on the percentage of the total area affected. The scores were: 0 (<5), 1 (5–33%), 2 (33–66%) and 3 (66%) [41]. Five fields were analyzed per animal, and an average score of each animal was considered for statistical analysis. In addition, the liver index was calculated as follows:

| Liver index = liver weight (g)/body weight (g) |

In vivo studies were performed in a blinded fashion at the histological analysis stage. For the quantification of tissue staining and pathological evaluation of animal specimens, the investigator was blinded to ensure an unbiased interpretation of the results.

2.5. Serum Analysis

At the end of the experimental period, blood samples were collected from the abdominal aorta and centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 20 min to separate the serum. The levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), triglycerides, and total cholesterol were analyzed using a DRI-CHEM 7000i (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan). The malondialdehyde (MDA) content was determined using an OxiSelect™ TBARS Assay Kit (MDA Quantitation) (Cell Biolabs Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The levels of MDA were measured at 532 nm using a microplate reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland).

2.6. Cell Culture

Human hepatoblastoma HepG2 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Cat. No. ATCC HB-8065, Manassas, VA, USA) and grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified incubator under 95% air and 5% CO2. Cells were seeded on different types of plates and serum-starved for 24 h in a serum-free medium before experimental treatment. G. cambogia extract (dissolved in DW) and other reagents (dissolved in DMSO to a final DMSO concentration in the medium of ≤0.2%) were added for the indicated time periods. HepG2 cells were used at passages 4–7.

2.7. Free Fatty Acids (FFAs) Solution Preparation

The FFAs solution was prepared by previously described methods [42]. Briefly, the FFA-containing stock solution was prepared by conjugation of oleate (0.67 mM) and palmitate (0.33 mM) with 1% FFA-free BSA in a serum-free medium (final FFA concentration, 1 mM). After 24 h of incubation with FFA-containing medium and experimental treatments, the extent of steatosis, apoptosis, ROS levels, and protein expression levels was evaluated.

2.8. MTT Assay

Cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay. HepG2 cells were seeded on 96-well plates and incubated in a serum-free medium. After 24 h, the G. cambogia, other reagents, and 100 μg/mL digitonin (used as a positive control for cytotoxicity [43]) were added for 24 h. After the reaction was terminated, 5 mg/mL of MTT reagent was added, and the cells were incubated at 37 °C under humidified 5% CO2. After 3 h, dimethyl sulfoxide was added to dissolve any formed crystals. The absorbance was measured at 565 nm using a microplate reader (Tecan Group Ltd.). All results are expressed as fold changes relative to the control (no stimulation) value.

2.9. Oil Red O Staining

Lipid droplets in cells were examined using oil red O staining after the reaction was terminated. HepG2 cells were fixed using 4% formaldehyde for 1 h and washed with 60% isopropanol. Then, the fixed cells were stained with filtered oil red O solution in 60% isopropanol for 10 min. After the oil red O solution was removed, the stained cells were washed with distilled water. Images of lipid droplets in the stained cells were acquired using an Olympus IX71 digital microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The stained lipid droplets were dissolved in 100% isopropanol and quantified by measuring the absorbance at 520 nm using a microplate reader (Tecan Group Ltd.).

2.10. Western Blot Analysis

Western blotting was performed to detect protein levels in cells and tissues. Proteins were extracted in ice-cold RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% NP-40, 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM NaF, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]). The protein concentration in the lysates was quantified using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Equivalent amounts of protein were separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE, 7.5–12.5%) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (ATTO Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The membranes were blocked with TBS-T (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.6) containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h. Next, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight and were then incubated with secondary antibodies for 6 h at 4 °C. Specific signals were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (ATTO Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The band densities were quantified using Image Lab software (Version 5.2.1, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.11. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

Total RNAs in cells and tissues were isolated using TRIzol™ (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using AccuPower CycleScript RT Premix (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea) and 1 µg RNA in a thermocycler. Real-time PCR amplification was performed using 96-well optical plates, with TOPreal™ qPCR 2X PreMIX (SYBR Green with low ROX) (Enzynomics, Daejeon, Korea), 400 nM each of forward and reverse primer and 1 µL of cDNA and H2O in a 20 µL reaction volume. Real-time fluorescence of PCR products was detected using CFX96 Real-Time Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at following thermocycling conditions: 1 cycle of 95 °C for 3 min; 39 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, and 60 °C for 30 s; 1 cycle of 95 °C for 10 s and 65 °C for 5 s followed by 0.5 °C increments at 5 s/step back to 95 °C. Only primer pairs leading to the synthesis of a single fragment with the appropriate size were used in this study. Primer sets used for this study were listed in Table S1. The relative gene expression was calculated using a 2−∆∆ct method, which was normalized by β-actin expression level.

2.12. TUNEL Staining

A Click-iT™ Plus TUNEL Assay for in situ apoptosis detection (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used for TUNEL staining, which was performed using sections from liver tissues. As positive controls, sections were pre-treated with DNase I (30 U). Images were acquired using a confocal laser microscope (K1-Fluo, Nanoscope Systems, Daejeon, Korea) using K1-image software (Nanoscope Systems, Daejeon, Korea). The number of TUNEL-positive cells was quantified using ImageJ software (Version 1.53c, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.13. Apoptosis Detection Assay

Apoptosis-mediated cell death was analyzed by annexin V (AV) and propidium iodide (PI) staining using a FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Pharmingen™, San Jose, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Briefly, cells were collected by trypsinization and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 3 min. The pellets were washed carefully with PBS and centrifuged. Then the cells were stained with AV-FITC/PI solution. The extent of AV-FITC and PI staining was measured using FACS Canto II and BD FACS Diva software. AV− PI− (viable), AV+ PI− (early apoptotic), AV+ PI+ (late apoptotic), and AV− PI+ (necrotic) cells were analyzed using FlowJo software (Version 10, FlowJo LLC, Ashland, OR, USA), and the data are summarized in one graph.

2.14. Caspase-3 Activity

The in vitro and in vivo caspase-3 activity assay was carried out in accordance with the instructions provided by the Caspase-3 Assay Kit (Abcam, MA, USA). Briefly, lysates of cells or liver tissues were collected, and reaction buffer with dithiothreitol (DTT, 10 mM) was added. Then, the caspase-3 substrate in the kit (DEVD-p-NA, 200 μM) was treated for 60 min at 37 °C. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm using a microplate reader (Tecan Group Ltd.). All results are expressed as fold changes relative to the control (no stimulation) value.

2.15. Determination of Intracellular ROS Level

HepG2 cells were seeded into black 96-well plates. Cells incubated with FFAs were cotreated with G. cambogia and N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC, 4 mM, positive control for antioxidant activity [44]). After the reaction was terminated, the medium was removed, and H2DCFDA (20 μM) diluted in serum-free medium was added to the cells and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were washed and filled with PBS, and the fluorescence intensity (excitation = 485 nm; emission = 530 nm) was measured using a fluorescence reader (Infinite F200, Tecan Group Ltd.). All results are expressed as fold changes relative to the control (no stimulation) value.

2.16. Cell Fractionation

Cell fractionation was performed as described previously [45]. Briefly, HepG2 cells were treated with FFA and G. cambogia for 12 h. After the reaction was terminated, cells were centrifuged at 800× g for 10 min and homogenized in buffer 1 (250 mM sucrose, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate) and kept on ice for 30 min. Then, the homogenate was mixed by vortexing for 15 s and centrifuged at 800× g for 15 min at 4 °C to obtain supernatant (S0) and pellet (P0). The pellet (P0) was mixed with buffer 1 by vortexing for 15 s and centrifuged at 500× g for 15 min at 4 °C. The obtained pellet was resuspended in buffer 2 (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 M NaCl, 20% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate) by vortexing for 15 s and kept on ice for 30 min. Then, the homogenate was placed on ice in a Vibra-Cell sonicator (Sonics, Newtown, CT, USA) for 8 × 5 s bursts with 10 s intervals. The homogenate was centrifuged at 9000× g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was resuspended in 5× SDS loading buffer to generate the nuclear fraction. Western blot analysis was performed to identify nuclear fraction proteins. Lamin A/C was used as a loading control for the nucleus.

2.17. Immunofluorescence

HepG2 cells were seeded with coverslips and placed in 24-well plates. Then, HepG2 cells were treated with FFA and G. cambogia for 12 h. After the reaction was completed, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS and 1% BSA for 5 min. Then cells were blocked with 5% goat serum in PBS. After 1 h, cells were incubated with NRF2 primary antibodies for 16 h at 4 °C and subsequently treated with secondary antibodies in PBS with 3% BSA for 2.5 h at room temperature. Then cell nuclei were stained by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and observed under a confocal laser microscope (K1-Fluo, Nanoscope systems, Daejeon, Korea) using K1-image software (Nanoscope systems, Daejeon, Korea). The intensity of nuclear NRF2 was measured by ImageJ software (Version 1.53c, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.18. Dual-Luciferase Assay

HepG2 cells were co-transfected with a DNA mixture containing the pGL4.37[luc2P/ARE/Hygro] reporter (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), renilla luciferase control reporter (pRL-TK, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and 1 μL of Lipofectamine 2000. After 4 h, cells were treated with FFA and G. cambogia for 12 h. After cells were harvested using passive lysis buffer, ARE promoter activity was measured with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) using a Glomax 20/20 luminometer reader (Promega). Specific promoter activity was expressed as the relative activity ratio of firefly luciferase to Renilla luciferase.

2.19. Identification of Hydroxycitric Acid in G. cambogia Using Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry

For the identification of hydroxycitric acid in G. cambogia, the content of hydroxycitric acid was analyzed using liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS). The G. cambogia powder was dissolved at a concentration of 1 μg/mL in distilled water. After vortexing for 1 min, the solution was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 7 min. The supernatant was transferred to an LC vial for LC-HRMS analysis. The LC-HRMS system consisted of a CTC HTS PAL auto-sampler (LEAP Technologies, Carrboro, NC, USA), LC-20AD pumps (Shimadzu Corporation, Columbia, MD, USA), CBM-20A controller (Shimadzu Corporation), and a hybrid quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer 5600 with an electrospray ionization source (Sciex, Foster City, CA, USA). The hybrid quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer 5600, equipped with an electrospray ionization source, was operated in the negative ion mode. The mass transition of parent-to-parent ion was used for hydroxycitric acid (m/z 207.0→207.0). Water containing 0.1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid (B) was used as mobile phase. The flow rate was 0.4 mL/min. Error ppm was applied for the accuracy of measurement. Data processing was performed using the Analyst® TF 1.6 and MultiQuant™ software (Version 3.0.3, Sciex).

2.20. Statistical Analyses

All data were expressed as mean ± S.D. of 4–7 independent experiments mentioned in the respective figure legends or graphs. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software (Version 9, San Diego, CA, USA). The normality of the data distributions was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. A two-sided, unpaired Student’s t-test was used to analyze the difference between two groups of data. The data in Figures 1F and 2E were analyzed using Welch’s t-test for unequal variances. Differences across three or more groups were tested via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by a post hoc analysis with Bonferroni’s test if F achieved statistical significance (p < 0.05) and there was no significant variance in homogeneity with the Barlett’s test. The correlation results were determined by Pearson’s rank test. Differences with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Garcinia cambogia Attenuates NALFD in HFD-Induced Mice by Reducing Hepatic Steatosis

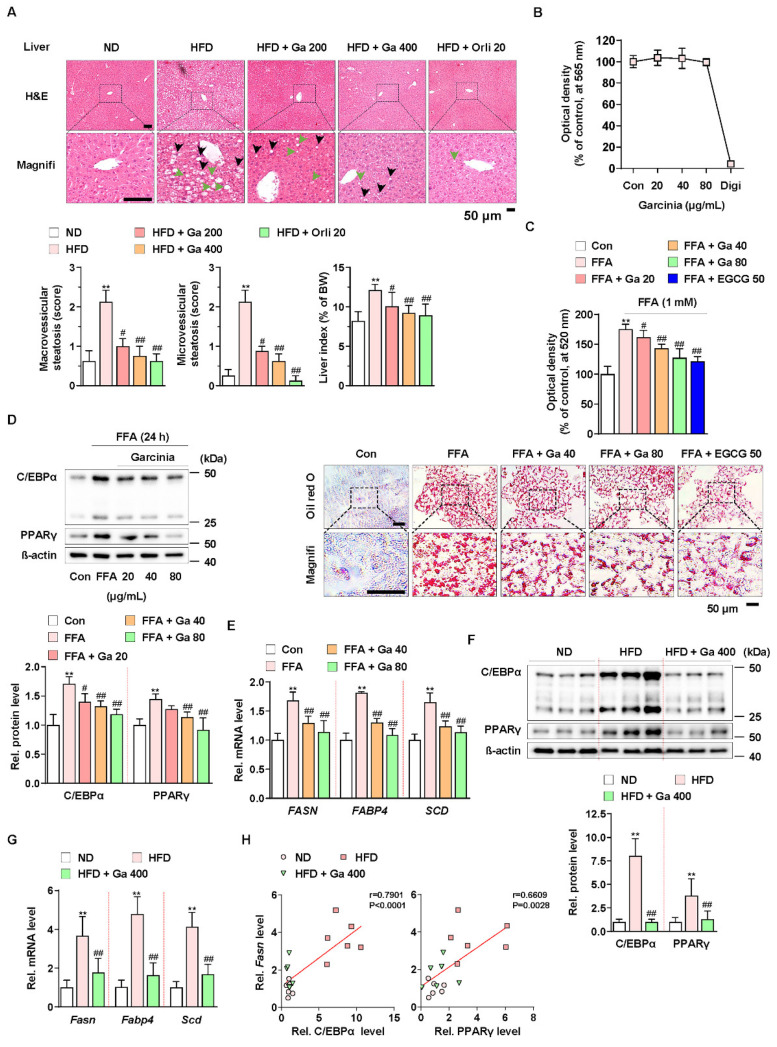

To investigate the effect of G. cambogia on NAFLD in HFD-fed mice, we administered G. cambogia and orlistat (positive control for the anti-obesity effect) for 8 weeks with HFD feeding. As shown in Table 1, G. cambogia significantly reduced weight gain resulting from HFD feeding, indicating an anti-obesity effect. In addition, administration of G. cambogia improved the abnormal serum levels of measured parameters, such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), markers of liver function, and triglycerides and total cholesterol, and markers of lipid metabolism, indicating that G. cambogia can regulate HFD-induced abnormal metabolic phenotype. Furthermore, G. cambogia inhibited the formation of hepatic lipid droplets and increased liver index, an indicator of NAFLD [46], resulting from HFD feeding (Figure 1A). There were no signs of obvious pathological changes in major organs such as the heart, spleen, lung, and kidney, implying no other organ toxicity (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Anti-NALFD effect of Garcinia cambogia in HFD-fed mice reducing hepatic steatosis. (A) Representative images showing the effect of G. cambogia (Ga, 200 and 400 mg/kg) on HFD-induced hepatic steatosis. H&E staining of liver tissues was performed. The scores of macrovesicular (black arrow) and microvesicular (green arrow) steatosis and liver index were quantified, as described in the Methods section. Normal diet (ND)-fed mice were used as the negative control for high levels of fat accumulation, and orlistat (20 mg/kg) was used as the positive control for anti-obesity and anti-steatosis effects (n = 7 per group). Scale bars: 50 μm. Magnifi: magnification. ** p < 0.01 vs. ND-fed mice, # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 vs. HFD-fed mice. (B) MTT assay showing the effect of G. cambogia (20–80 μg/mL) on cell viability. HepG2 cells were treated with the indicated concentration of G. cambogia and digitonin (100 μg/mL, positive control) for 24 h (n = 5 per group). (C) oil red O assay and representative images showing the effect of G. cambogia (20–80 μg/mL) on free fatty acid (1 mM FFA)-induced lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells. FFA-induced HepG2 cells were treated with G. cambogia and EGCG (50 μM, positive control) for 24 h (n = 5 per group). Scale bar: 50 μm. Magnifi: magnification. ** p < 0.01 vs. Con, # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 vs. FFA. Effect of G. cambogia (20–80 μg/mL) on (D) C/EBPα and PPARγ expression and (E) transcript levels of FASN, FABP4, and SCD in FFA-treated HepG2 cells (d, n = 4 per group; e, n = 5 per group). Effect of G. cambogia on (F) C/EBPα and PPARγ expression and (G) Fasn, Fabp4, and Scd transcript levels of liver tissues from ND-fed, HFD-fed, and HFD-fed mice administered a high dose of G. cambogia (400 mg/kg) (n = 6 per group). (H) Correlations between Fasn transcript and C/EBPα and PPARγ protein levels in liver tissues (n = 6 per group). Each point represents one sample. Data are mean ± S.D.

To examine the underlying mechanism, we used the HepG2 cell line for an in vitro study. Compared to digitonin (100 μg/mL, positive control for cytotoxicity), G. cambogia (20–80 μg/mL) did not show any cytotoxic effects for 24 h in HepG2 cells (Figure 1B). In addition, G. cambogia significantly reduced free fatty acid (1 mM FFA, composed of oleate and palmitate)-induced lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells for 24 and 48 h, similar to EGCG (50 μM) as a known substance to have an anti-steatosis effect (Figure 1C and Figure S2A) [47].

Since hepatic lipid accumulation is regulated by lipogenesis-related molecules, we examined the levels of C/EBPα and PPARγ, two major transcription factors of lipogenesis, in FFA-treated HepG2 cells. As shown in Figure 1D, FFA treatment increased C/EBPα and PPARγ expression indicating de novo lipogenesis. However, G. cambogia significantly decreased FFA-induced alterations in the C/EBPα and PPARγ expression. Then we measured the effect of G. cambogia on the lipogenic gene transcription activated by C/EBPα and PPARγ. FFA treatment increased the levels of fatty acid synthase (FASN), fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4), and stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) transcripts, and G. cambogia significantly reduced the transcription of these genes (Figure 1E). As in the results of in vitro experiments, G. cambogia significantly reduced the protein levels of C/EBPα and PPARγ (Figure 1F) and the transcript levels of Fasn, Fabp4, and Scd (Figure 1G) in liver tissues of HFD-fed mice. As shown in Figure 1H, significant positive correlations were observed between Fasn transcript and C/EBPα and PPARγ proteins, indicating that increased C/EBPα and PPARγ by HFD were inhibited by G. cambogia, which regulated lipogenic genes such as Fasn. These results provide critical insight into the inhibitory effect of G. cambogia on NAFLD via suppressing hepatic steatosis.

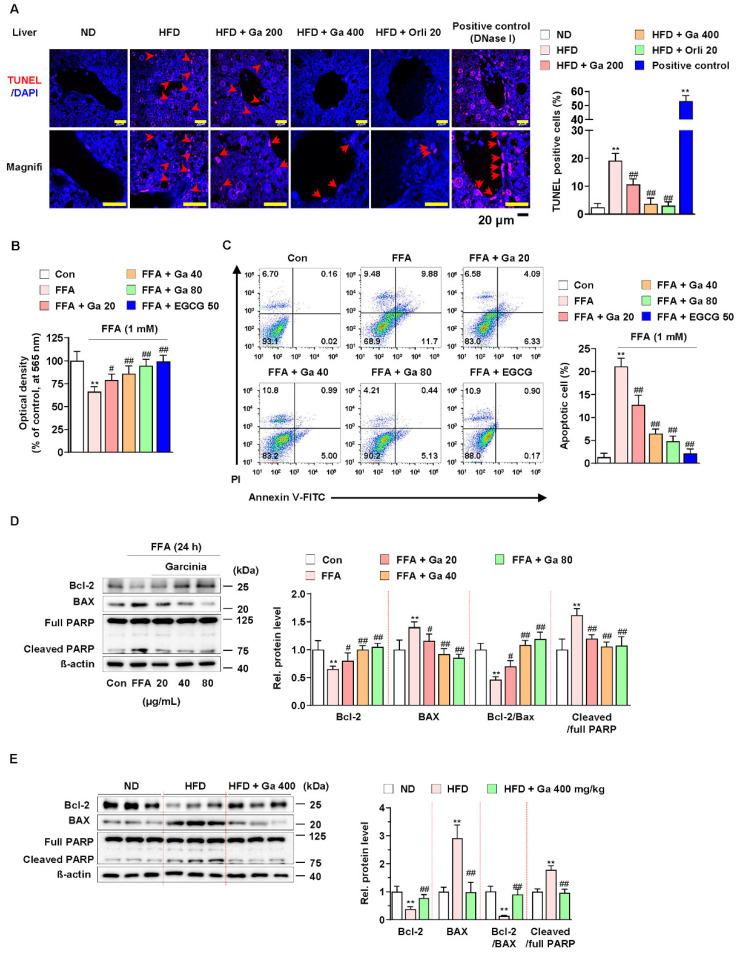

3.2. Garcinia cambogia Suppressed FFA-Induced Apoptosis in the Liver

Excessive FFAs in the liver by consuming HFD cause apoptosis and triglyceride accumulation [48]. In addition, hepatocellular apoptosis plays a major role in the early mechanism underlying the progression of liver diseases, including NAFLD [49]. Thus, we examined whether G. cambogia regulates FFA-induced apoptosis. As shown in Figure 2A, G. cambogia administration significantly decreased the rate of HFD-induced apoptosis, as measured by TUNEL in liver tissues. In addition, FFA treatment reduced HepG2 cell viability; however, treatment with either G. cambogia (20–80 μg/mL) or EGCG (50 μM) improved cell viability, which had been reduced by FFA for 24 and 48 h (Figure 2B and Figure S2B). Moreover, G. cambogia and EGCG (positive control of anti-apoptosis effect [50]) inhibited FFA-induced cell apoptosis, indicating that the improvement of cell viability by G. cambogia was due, at least in part, to suppression of apoptosis (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Effect of Garcinia cambogia on HFD-induced apoptosis in the liver. (A) Representative images of TUNEL staining and quantification data for the number of TUNEL-positive cells in HFD-induced liver tissues. Positive control: DNase I (30 U) treated group. Scale bar: 20 μm. (n = 6 per group). Magnifi: magnification. ** p < 0.01 vs. ND-fed mice, ## p < 0.01 vs. HFD-fed mice. (B) MTT assay showing the effect of G. cambogia on FFA-induced cell viability. Cells were treated with G. cambogia (20–80 μg/mL) and EGCG (50 μM) for 24 h (n = 5 per group). ** p < 0.01 vs. Con, # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 vs. FFA. (C) Effect of G. cambogia on apoptosis in FFA-treated HepG2 cells. Cells were treated with G. cambogia (20–80 μg/mL) and EGCG (50 μM) for 24 h (n = 4 per group). The numbers of negatively and positively stained cells are expressed as percentages of the total number of cells. (D) Effect of G. cambogia on Bcl-2 and BAX expression and PARP cleavage in FFA-treated HepG2 cells (n = 4 per group). (E) Effect of G. cambogia on Bcl-2 and BAX expression and PARP cleavage of liver tissues from ND-fed, HFD-fed, and HFD-fed mice administered a high dose of G. cambogia (400 mg/kg) (n = 6 per group). Data are mean ± S.D.

Since apoptosis is regulated by proapoptotic and antiapoptotic molecules such as Bcl-2 family members related to mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequent caspase-3 activation and cleavage of PARP [51,52,53], we examined the effect of G. cambogia on the alteration of apoptosis-related molecules in FFA-treated HepG2 cells. FFA treatment significantly decreased the expression of Bcl2 apoptosis regulator (Bcl-2) and increased the expression of Bcl-2-associated X protein (BAX), thereby suppressing the Bcl-2/BAX ratio, and increased the levels of caspase-3 activity and cleaved PARP indicating the induction of apoptosis (Figure S3A and Figure 2D). These results were similar in experiments observed in the liver tissues of HFD-fed mice (Figure S3B and Figure 2E). In both in vitro and in vivo experiments, G. cambogia (20–80 μg/mL) treatment increased the Bcl-2/Bax ratio and inhibited caspase-3 activation and PARP cleavage, indicating that G. cambogia suppresses apoptosis-related apoptosis pathways. Taken together, these results suggest that G. cambogia alleviates HFD- and FFA-induced apoptosis to inhibit the progression of NAFLD.

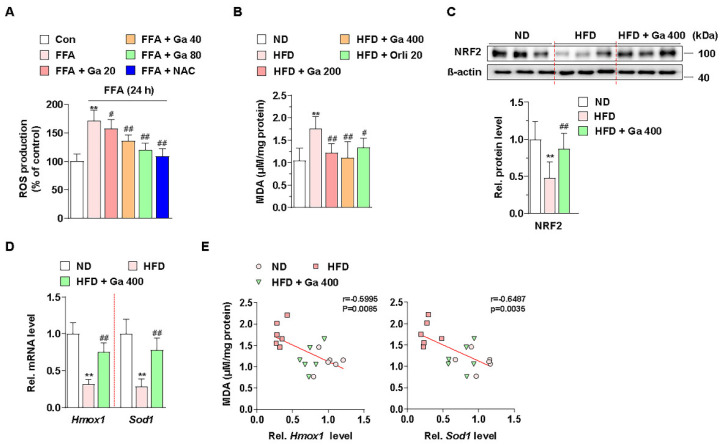

3.3. Garcinia cambogia Inhibits HFD- and FFA-Induced ROS Production via NRF2 Activation

Excessive accumulation of FFAs by energy imbalance in the liver produces ROS, and high levels of ROS can induce lipid accumulation via failure of lipid metabolism and liver damage via apoptosis [48]. Thus, we examined whether G. cambogia regulates FFA-induced ROS production. Intracellular ROS levels were increased by FFA in HepG2 cells, and both G. cambogia (20–80 μg/mL) and NAC (5 mM, positive control for the antioxidant effect [54]) significantly reduced FFA-induced ROS production for 24 and 48 h (Figure 3A and Figure S2C). In addition, the serum level of MDA, as a marker of oxidative stress and antioxidant status [55,56], was increased in HFD-fed mice, but G. cambogia administration alleviated the increase in the MDA level, indicating G. cambogia-mediated antioxidant effect (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Effect of Garcinia cambogia on HFD- and FFA-induced ROS production, and NRF2 and downstream gene activation. (A) Effect of G. cambogia on ROS level in FFA-treated HepG2 cells. Cells were treated with G. cambogia (20–80 μg/mL) or NAC (5 mM, positive control of antioxidant) for 24 h. ROS production was measured using H2DCFDA (n = 5 per group). ** p < 0.01 vs. Con, # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 vs. FFA. (B) Effect of G. cambogia on malondialdehyde (MDA, indicating the intensity of lipid peroxidation) level of serum in HFD-fed mice (n = 7 per group). Effect of G. cambogia on (C) NRF2 expression and (D) Hmox1 and Sod1 transcript levels of liver tissues from ND-fed, HFD-fed, and HFD-fed mice administered a high dose of G. cambogia (400 mg/kg) (n = 6 per group). (E) Correlations between MDA level and Hmox1 and Sod1 transcript levels in liver tissues (n = 6 per group). Each point represents one sample. ** p < 0.01 vs. ND-fed mice, # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 vs. HFD-fed mice. Data are mean ± S.D.

Cellular ROS are regulated by endogenous antioxidant defense systems such as enzymatic antioxidants like heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) [57]. In addition, NRF2, one of the major transcription factors of the antioxidant defense system, regulates HMOX1 and SOD transcription for ROS homeostasis [58]. Thus, we examined whether G. cambogia regulates NRF2 levels in HFD-fed mice and FFA-treated HepG2 cells. As a result of measuring NRF2 expression level in the livers of HFD-fed mice, we found that G. cambogia reduced HFD-induced inhibition of NRF2 expression (Figure 3C). In addition, Hmox1 and Sod1 gene expression, which had been inhibited by HFD, were recovered by G. cambogia (Figure 3D). Furthermore, significant negative correlations between MDA protein and Hmox1 and Sod1 transcripts were observed, indicating that increased MDA by HFD was inhibited by G. cambogia-induced alterations of the antioxidant defense system (Figure 3E). Taken together, G. cambogia activates the intracellular antioxidant defense system by increasing the expressions of NRF2 and downstream genes to reduce ROS production.

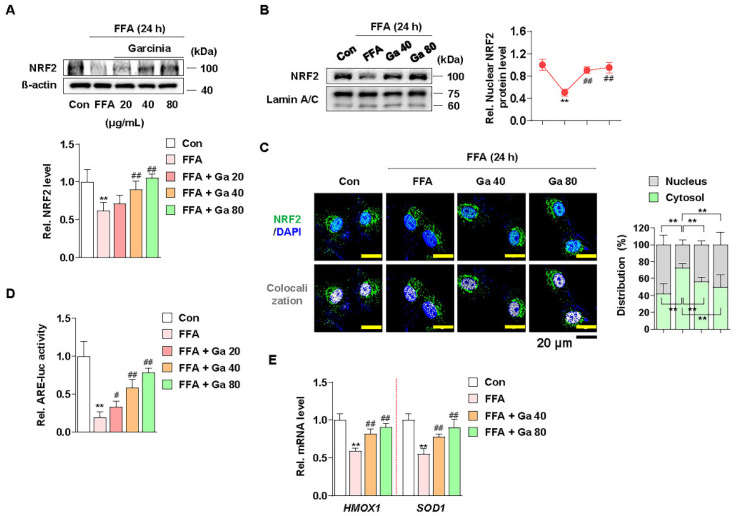

3.4. Increased NRF2 Nuclear Expression and ARE Activation by Garcinia cambogia Regulates Antioxidant Gene Expression in FFA-Treated HepG2 Cells

NRF2 functions as a transcription factor in the nucleus by ARE promoter activation and subsequent modulation of antioxidant gene expression [59]. Thus, we examined whether G. cambogia affected the nuclear expression of NRF2 and ARE promoter activity and in FFA-treated HepG2 cells. Similar to the in vivo results, FFA significantly reduced the expression of NRF2, and G. cambogia restored FFA-induced inhibition of NRF2 expression (Figure 4A). Moreover, G. cambogia increased the expression of NRF2 in the nucleus (Figure 4B,C), which could influence the expression of downstream genes. In addition, G. cambogia increased FFA-induced reduction of ARE activity (Figure 4D). As expected, G. cambogia restored FFA-induced reduction of HMOX1 and SOD1 gene expressions (Figure 4E). Taken together, these results suggest that G. cambogia activates the NRF2-ARE signaling pathway to inhibit FFA-induced abnormal ROS production.

Figure 4.

Effect of Garcinia cambogia on NRF2-ARE activation in FFA-induced HepG2 cells. (A) Effect of G. cambogia (20–80 μg/mL) on NRF2 expression in FFA-treated HepG2 cells (n = 4 per group). (B) Effect of G. cambogia on NRF2 nuclear expression in FFA-treated HepG2 cells. Cells were treated with G. cambogia (40 and 80 μg/mL) for 12 h, and cells were fractionated into nucleus compartment as described in the Methods section (n = 4 per group). (C) Representative immunofluorescence images of NRF2 in FFA-treated HepG2 cells. Colocalized FITC (i.e., NRF2) and DAPI (i.e., nuclei) were quantified using ImageJ software, and relative intensities in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were expressed as a histogram. Scale bars: 20 μm (n = 5 per group). (D) Effect of G. cambogia on ARE promoter activity in FFA-treated HepG2 cells. ARE-luc vector-transfected HepG2 cells were cotreated FFA and G. cambogia (20–80 μg/mL) for 12 h and detected ARE promoter activity (n = 6 per group). (E) Effect of G. cambogia (20–80 μg/mL) on the transcript levels of HMOX1 and SOD1 in FFA-treated HepG2 cells (n = 5 per group). ** p < 0.01 vs. Con, # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 vs. FFA. Data are mean ± S.D.

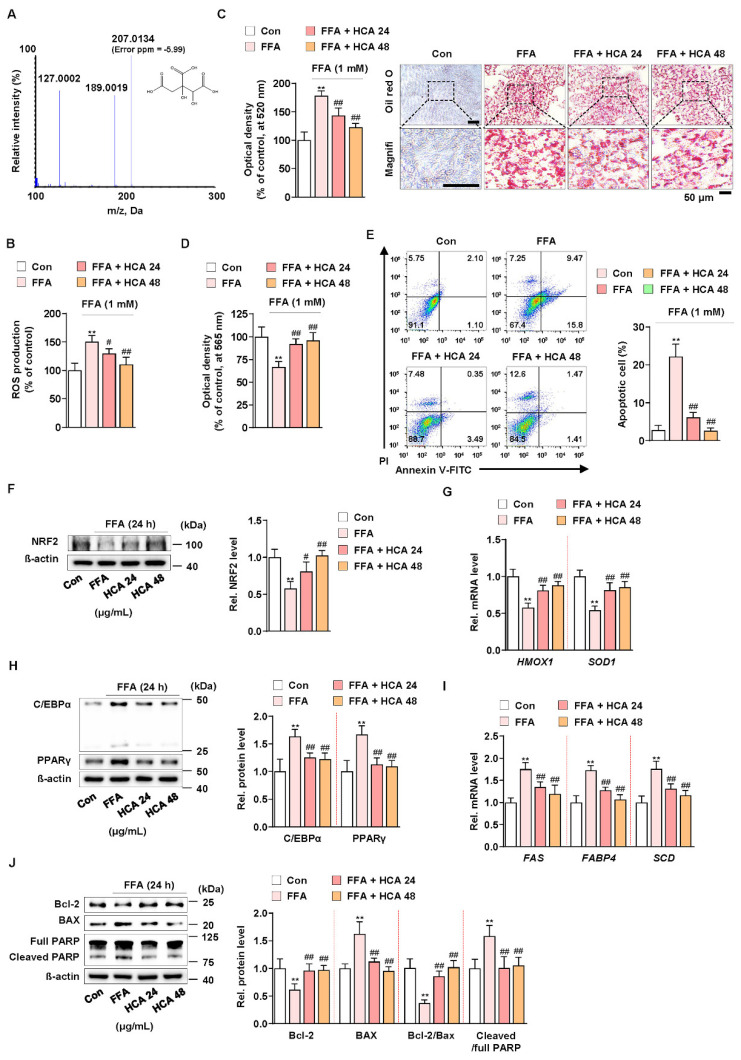

3.5. Hydroxycitric Acid Contributed to Suppress FFA-Induced ROS Production, Lipid Accumulation, and Apoptosis

A recent study reported that hydroxycitric acid (HCA) reduced oleic acid-induced steatosis and oxidative stress in primary chicken hepatocytes [60]. In addition, it is known that G. cambogia contains from 20 to 60% hydroxycitric acid (HCA) as a main component [24]. The HCA content of G. cambogia used in this experiment was analyzed using liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS), and HCA content was 59.55 ± 2.66% (Figure 5A). To verify whether the same action of G. cambogia as shown so far is actually the same in HCA, the effect of HCA (24 and 48 μg/mL) at concentrations equivalent to those of G. cambogia (40 and 80 μg/mL) on FFA-induced ROS production, lipid accumulation, and apoptosis was examined in FFA-treated HepG2 cells. HCA significantly inhibited FFA-induced ROS production and lipid accumulation (Figure 5B,C). In addition, HCA attenuated FFA-induced reduction of cell viability and induction of apoptosis (Figure 5D,E). Similar to the effect of G. cambogia, HCA ameliorated FFA-induced decrease of NRF2 expression and HMOX1 and SOD1 transcription, indicating an antioxidant effect of HCA (Figure 5F,G). Furthermore, HCA regulated lipogenesis- and apoptosis-related signaling pathways. As shown in Figure 5H, HCA inhibited FFA-induced upregulation of C/EBPα and PPARγ expression, FAS, FABP4, and SCD transcription to suppress lipogenesis (Figure 5H,I). In addition, HCA significantly altered the FFA-induced Bcl-2/BAX ratio, caspase-3 activity, and PARP cleavage to reduce apoptosis (Figure 5J and Figure S3C). These results indicated that the underlying effects of G. cambogia are due, at least in part, to HCA.

Figure 5.

Effect of hydroxycitric acid on FFA-induced ROS production, lipid accumulation, and apoptosis in HepG2 cells. (A) MS/MS spectrum of hydroxycitric acid [M − H]−. The parent ion was the deprotonated [M − H]− ion at m/z 207.0 and the most abundant ion in product ion scan mode. (B) ROS measurement using H2DCFDA in FFA-treated HepG2 cells treated with HCA (24 and 48 μg/mL) (n = 5 per group). (C) Oil red O assay and representative images showing the effect of HCA (24 and 48 μg/mL) on FFA-induced lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells. Cells were treated with HCA (24 and 48 μg/mL) for 24 h (n = 5 per group). Scale bar: 50 μm. Magnifi: magnification. (D) MTT assay showing the effect of HCA (24 and 48 μg/mL) on FFA-induced cell viability. Cells were treated with HCA (24 and 48 μg/mL) for 24 h (n = 5 per group). (E) Effect of HCA (24 and 48 μg/mL) on apoptosis in FFA-treated HepG2 cells. Cells were treated with HCA (24 and 48 μg/mL) for 24 h (n = 4 per group). The numbers of negatively and positively stained cells are expressed as percentages of the total number of cells. Effect of HCA (24 and 48 μg/mL) on the levels of (F) NRF2 expression, (G) HMOX1 and SOD1 transcriptions, (H) C/EBPα and PPARγ expression, (I) FAS, FABP4 and SCD transcriptions, and (J) Bcl-2 and BAX expression and PARP cleavage in FFA-treated HepG2 cells (n = 4 per group in f, h, and j; n = 5 per group in G,I). ** p < 0.01 vs. Con, # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 vs. FFA. Data are mean ± S.D.

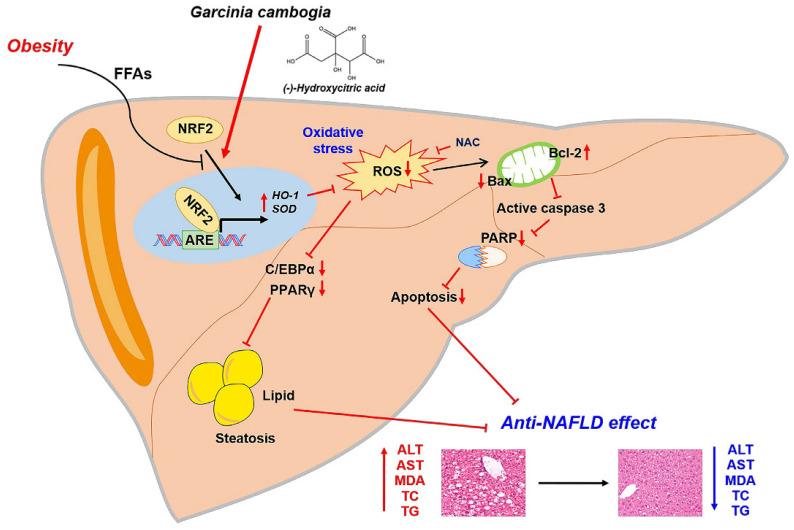

Taken together, our results support the conclusion that NRF2 activation by G. cambogia and HCA contributed to the antioxidant effect also affects NAFLD progression through hepatic steatosis and apoptosis inhibition (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Proposed mechanism of the protective effect of G. cambogia against NAFLD. G. cambogia inhibited HFD-induced NAFLD by activating the NRF2-ARE-mediated antioxidant defense system, leading to inhibition of hepatic steatosis and apoptosis in the liver.

4. Discussion

To date, there are no effective pharmacological therapies for NAFLD; thus, therapeutic approaches to manage NAFLD by dietary supplementation, for example, silymarin [61], berberine [19], and resveratrol [62], are considered. Although G. cambogia, a natural product used as a weight-loss supplement in many countries, has been reported to have an anti-NAFLD effect [28], the underlying mechanism is poorly understood.

In the present study, we demonstrated for the first time that (1) G. cambogia suppressed hepatic steatosis and apoptosis in the liver of HFD-fed mice and in FFA-treated HepG2 cells; (2) G. cambogia inhibited HFD- and FFA-induced upregulation of C/EBPα and PPARγ expression, and FASN, FABP4, and SCD transcription to regulate lipogenesis; (3) G. cambogia reduced the HFD- and FFA-induced alterations of the Bcl-2/BAX ratio and PARP cleavage to regulate apoptosis; and (4) these normalizations were due to the antioxidant effect of G. cambogia and HCA through NRF2-ARE pathway activation. These findings are summarized in Figure 6.

The effect of G. cambogia and HCA, its main constituent, on lipogenesis has been reported in several studies in animal models [24,25,63]. It was recently published that the regulatory effect of HCA on lipid accumulation in cultured primary chicken hepatocytes reduces the acetyl-CoA supply, which is mainly achieved via inhibition of ATP-citrate lyase and acceleration of energy metabolism [63]. In addition, HCA reduced steatosis and oxidative stress by regulating the AMPK-mediated signaling pathway [60]. However, our study focused on the antioxidant effect of G. cambogia and HCA via NRF2-ARE activation, and it modulated lipogenesis and apoptosis to ameliorate NAFLD.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated in cells by several factors, such as stressor responses and environmental factors [64]. Excessive accumulation of free fatty acids (FFAs) due to western diets, including high-fat, is one of the important factors. ROS overproduction induces lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and lipogenic protein activation to increase fat accumulation in the liver [12]. In addition, excessive ROS activates hepatic C/EBPα and PPARγ, key transcription factors that control many lipogenic genes, such as FASN, FABP4, and SCD, to promote NAFLD progression [65,66]. Our study firstly revealed that G. cambogia and HCA inhibited HFD- and FFA-induced C/EBPα and PPARγ activation by reducing intracellular ROS levels and leading to suppression of lipogenic gene transcription and hepatic steatosis (Figure 1, Figure 3A,B and Figure 5).

Increased ROS levels have been indicated to enhance the expression of apoptosis-related proteins [48]. In addition, apoptosis is a prominent feature of NAFLD progression and liver disease [67]. Since ROS causes mitochondrial dysfunction and alterations in Bcl-2 family proteins such as Bcl-2 and BAX, which are major regulators of apoptotic processes and lead to collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential [68], we examined the effect of G. cambogia on Bcl-2 and BAX expression and PARP cleavage. This study revealed that G. cambogia and HCA significantly attenuated the HFD- and FFA-induced decrease in the Bcl-2/BAX ratio and induction of PARP cleavage, indicating suppression of ROS-mediated apoptosis (Figure 2 and Figure 5E,J).

G. cambogia contains many components, including alkaloids, flavonoids, phenolic compounds, saponins, tannins, carbohydrates, and proteins [24]. To date, few single compounds have been isolated from G. cambogia. HCA, garcinol, and guttiferone K isolated from the extract showed protective antioxidant effects against lipid and protein oxidation/glycation and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [69,70,71]. In addition, advanced glycation end products (AGE) can be a potential biomarker of the NAFLD stage since AGE showed good criteria for dividing patients with minimal steatosis (BARD score 0–1) vs. moderate steatosis (BARD score 2–4) [72]. Furthermore, a high intake of fat and carbohydrates can induce ER stress, and dysfunction of ER develops metabolically-driven NAFLD progress [73,74]. Although this study revealed that HCA had therapeutic effects by suppressing lipid accumulation and apoptosis in liver cells, other components may be effective to NAFLD since recent clinical trials suggest that protein oxidation/glycation and ER stress are involved in liver fibrosis in NAFLD [75,76]. Thus, further studies are needed to investigate additional anti-NAFLD effects and the underlying mechanism of the G. cambogia and its components.

Finally, it has been reported that G. cambogia is associated with hepatotoxicity, including lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress genes [77]. However, this assertion is controversial because our study showed that G. cambogia administration suppressed the HFD-induced increases in ALT and AST levels (Table 1), and G. cambogia inhibited HFD- and FFA-induced oxidative stress via upregulating antioxidative barriers. In addition, HCA, the main constituent, does not promote liver toxicity or inflammation [78].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that G. cambogia inhibits HFD-induced NAFLD by suppressing hepatic steatosis and apoptosis through the regulation of lipogenesis- and apoptosis-related signaling pathways. These effects are due to the antioxidant effect of G. cambogia and HCA by activating the NRF2-ARE pathway. Our findings provide new insight into the mechanism by which G. cambogia suppresses NAFLD progression.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antiox10081226/s1, Figure S1: G. cambogia attenuates the HFD-induced NAFLD without organ toxicity, Figure S2: Effect of Garcinia cambogia on FFA-induced hepatic steatosis, cell viability and ROS production in HepG2 cells for 48 h, Figure S3: Effect of Garcinia cambogia and HCA on HFD- and FFA-induced caspase 3 activation, Table S1: Primers for real-time PCR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-H.H.; methodology, J.-H.H. and M.-H.P.; validation, M.-H.P. and C.-S.M.; formal analysis, M.-H.P. and C.-S.M.; investigation, J.-H.H. and M.-H.P.; resources, J.-H.H. and C.-S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-H.H.; writing—review and editing, J.-H.H. and C.-S.M.; supervision, J.-H.H. and C.-S.M.; funding acquisition, J.-H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea grant funded by the Korean government (grant number 2019R1C1C1010698).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal procedures in this study complied with the recommendations and guidelines for the use of experimental animals established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chungnam National University (2019012A-CNU-190).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hill J.O., Wyatt H.R., Peters J.C. Energy balance and obesity. Circulation. 2012;126:126–132. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.087213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paschos P., Paletas K. Non alcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome. Hippokratia. 2009;13:9–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Younossi Z.M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease—A global public health perspective. J. Hepatol. 2019;70:531–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fabbrini E., Sullivan S., Klein S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Biochemical, metabolic, and clinical implications. Hepatology. 2010;51:679–689. doi: 10.1002/hep.23280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parthasarathy G., Revelo X., Malhi H. Pathogenesis of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: An Overview. Hepatol. Commun. 2020;4:478–492. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Z., Yu Y., Cai J., Li H. Emerging Molecular Targets for Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2019;30:903–914. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rolo A.P., Teodoro J.S., Palmeira C.M. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012;52:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bugianesi E., McCullough A.J., Marchesini G. Insulin resistance: A metabolic pathway to chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;42:987–1000. doi: 10.1002/hep.20920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cichoz-Lach H., Michalak A. Oxidative stress as a crucial factor in liver diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8082–8091. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buzzetti E., Pinzani M., Tsochatzis E.A. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Metab. Clin. Exp. 2016;65:1038–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman S.L., Neuschwander-Tetri B.A., Rinella M., Sanyal A.J. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Med. 2018;24:908–922. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0104-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arroyave-Ospina J.C., Wu Z., Geng Y., Moshage H. Role of Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Implications for Prevention and Therapy. Antioxidants. 2021;10:174. doi: 10.3390/antiox10020174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sekiya M., Hiraishi A., Touyama M., Sakamoto K. Oxidative stress induced lipid accumulation via SREBP1c activation in HepG2 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;375:602–607. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin Y., Tan Y., Chen L., Liu Y., Ren Z. Reactive Oxygen Species Induces Lipid Droplet Accumulation in HepG2 Cells by Increasing Perilipin 2 Expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:3445. doi: 10.3390/ijms19113445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi Y., Abdelmegeed M.A., Song B.J. Preventive effects of dietary walnuts on high-fat-induced hepatic fat accumulation, oxidative stress and apoptosis in mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016;38:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeong H.S., Kim K.H., Lee I.S., Park J.Y., Kim Y., Kim K.S., Jang H.J. Ginkgolide A ameliorates non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases on high fat diet mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017;88:625–634. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geng C., Xu H.F., Zhang Y.L., Gao Y., Li M.X., Liu X.Y., Gao M.Y., Wang X.J., Liu X.J., Fang F.D., et al. Retinoic acid ameliorates high-fat diet-induced liver steatosis through sirt1. Sci. China Life Sci. 2017;60:1234–1241. doi: 10.1007/s11427-016-9027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drygalski K., Siewko K., Chomentowski A., Odrzygozdz C., Zalewska A., Kretowski A., Maciejczyk M. Phloroglucinol Strengthens the Antioxidant Barrier and Reduces Oxidative/Nitrosative Stress in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021;2021:8872702. doi: 10.1155/2021/8872702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Y., Yuan X., Zhang F., Han Y., Chang X., Xu X., Li Y., Gao X. Berberine ameliorates fatty acid-induced oxidative stress in human hepatoma cells. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:11340. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11860-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snezhkina A.V., Kudryavtseva A.V., Kardymon O.L., Savvateeva M.V., Melnikova N.V., Krasnov G.S., Dmitriev A.A. ROS Generation and Antioxidant Defense Systems in Normal and Malignant Cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019;2019:6175804. doi: 10.1155/2019/6175804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma Q. Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013;53:401–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011112-140320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma R.S., Harrison D.J., Kisielewski D., Cassidy D.M., McNeilly A.D., Gallagher J.R., Walsh S.V., Honda T., McCrimmon R.J., Dinkova-Kostova A.T., et al. Experimental Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Liver Fibrosis Are Ameliorated by Pharmacologic Activation of Nrf2 (NF-E2 p45-Related Factor 2) Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;5:367–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramadori P., Drescher H., Erschfeld S., Schumacher F., Berger C., Fragoulis A., Schenkel J., Kensler T.W., Wruck C.J., Trautwein C., et al. Hepatocyte-specific Keap1 deletion reduces liver steatosis but not inflammation during non-alcoholic steatohepatitis development. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016;91:114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Semwal R.B., Semwal D.K., Vermaak I., Viljoen A. A comprehensive scientific overview of Garcinia cambogia. Fitoterapia. 2015;102:134–148. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bilal T., Gursel F.E., Ates A., Altiner A. Effect of Garcinia cambogia extract on body weight gain, feed intake and feed conversion ratio, and serum non-esterified fatty acids and C-reactive protein levels in rats fed with atherogenic diet. Iran J. Vet. Res. 2012;13:330–333. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim K.Y., Lee H.N., Kim Y.J., Park T. Garcinia cambogia extract ameliorates visceral adiposity in C57BL/6J mice fed on a high-fat diet. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2008;72:1772–1780. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han J.H., Jang K.W., Park M.H., Myung C.S. Garcinia cambogia suppresses adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells by inhibiting p90RSK and Stat3 activation during mitotic clonal expansion. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021;236:1822–1839. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cha J.Y., Nepali S., Lee H.Y., Hwang S.W., Choi S.Y., Yeon J.M., Song B.J., Kim D.K., Lee Y.M. Chrysanthemum indicum L. ethanol extract reduces high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018;15:5070–5076. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han J.H., Jang K.W., Myung C.S. Garcinia cambogia attenuates adipogenesis by affecting CEBPB and SQSTM1/p62-mediated selective autophagic degradation of KLF3 through RPS6KA1 and STAT3 suppression. Autophagy. 2021:1–22. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2021.1936356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Percie du Sert N., Hurst V., Ahluwalia A., Alam S., Avey M.T., Baker M., Browne W.J., Clark A., Cuthill I.C., Dirnagl U., et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020;177:3617–3624. doi: 10.1111/bph.15193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ballinger A. Orlistat in the treatment of obesity. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2000;1:841–847. doi: 10.1517/14656566.1.4.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ye J., Wu Y., Li F., Wu T., Shao C., Lin Y., Wang W., Feng S., Zhong B. Effect of orlistat on liver fat content in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with obesity: Assessment using magnetic resonance imaging-derived proton density fat fraction. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284819879047. doi: 10.1177/1756284819879047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrison S.A., Fecht W., Brunt E.M., Neuschwander-Tetri B.A. Orlistat for overweight subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A randomized, prospective trial. Hepatology. 2009;49:80–86. doi: 10.1002/hep.22575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heymsfield S.B., Allison D.B., Vasselli J.R., Pietrobelli A., Greenfield D., Nunez C. Garcinia cambogia (hydroxycitric acid) as a potential antiobesity agent: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1596–1600. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nair A.B., Jacob S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2016;7:27–31. doi: 10.4103/0976-0105.177703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma B.R., Kim H.J., Kim M.S., Park C.M., Rhyu D.Y. Caulerpa okamurae extract inhibits adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and prevents high-fat diet-induced obesity in C57BL/6 mice. Nutr. Res. 2017;47:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rahman M.M., Kim M.J., Kim J.H., Kim S.H., Go H.K., Kweon M.H., Kim D.H. Desalted Salicornia europaea powder and its active constituent, trans-ferulic acid, exert anti-obesity effects by suppressing adipogenic-related factors. Pharm. Biol. 2018;56:183–191. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2018.1436073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drent M.L., Larsson I., William-Olsson T., Quaade F., Czubayko F., von Bergmann K., Strobel W., Sjostrom L., van der Veen E.A. Orlistat (Ro 18-0647), a lipase inhibitor, in the treatment of human obesity: A multiple dose study. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1995;19:221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ji W., Zhao M., Wang M., Yan W., Liu Y., Ren S., Lu J., Wang B., Chen L. Effects of canagliflozin on weight loss in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0179960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rovero Costa M., Leite Garcia J., Cristina Vagula de Almeida Silva C., Junio Togneri Ferron A., Valentini Francisqueti-Ferron F., Kurokawa Hasimoto F., Schmitt Gregolin C., Henrique Salome de Campos D., Roberto de Andrade C., Dos Anjos Ferreira A.L., et al. Lycopene Modulates Pathophysiological Processes of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Obese Rats. Antioxidants. 2019;8:276. doi: 10.3390/antiox8080276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liang W., Menke A.L., Driessen A., Koek G.H., Lindeman J.H., Stoop R., Havekes L.M., Kleemann R., van den Hoek A.M. Establishment of a general NAFLD scoring system for rodent models and comparison to human liver pathology. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e115922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ricchi M., Odoardi M.R., Carulli L., Anzivino C., Ballestri S., Pinetti A., Fantoni L.I., Marra F., Bertolotti M., Banni S., et al. Differential effect of oleic and palmitic acid on lipid accumulation and apoptosis in cultured hepatocytes. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009;24:830–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eid S.Y., El-Readi M.Z., Wink M. Digitonin synergistically enhances the cytotoxicity of plant secondary metabolites in cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 2012;19:1307–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Andrade K.Q., Moura F.A., dos Santos J.M., de Araujo O.R., de Farias Santos J.C., Goulart M.O. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Hepatic Diseases: Therapeutic Possibilities of N-Acetylcysteine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:30269–30308. doi: 10.3390/ijms161226225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dimauro I., Pearson T., Caporossi D., Jackson M.J. A simple protocol for the subcellular fractionation of skeletal muscle cells and tissue. BMC Res. Notes. 2012;5:513. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bedogni G., Bellentani S., Miglioli L., Masutti F., Passalacqua M., Castiglione A., Tiribelli C. The Fatty Liver Index: A simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-6-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Du Y., Paglicawan L., Soomro S., Abunofal O., Baig S., Vanarsa K., Hicks J., Mohan C. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Dampens Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver by Modulating Liver Function, Lipid Profile and Macrophage Polarization. Nutrients. 2021;13:599. doi: 10.3390/nu13020599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen Z., Tian R., She Z., Cai J., Li H. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020;152:116–141. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cao L., Quan X.B., Zeng W.J., Yang X.O., Wang M.J. Mechanism of Hepatocyte Apoptosis. J. Cell Death. 2016;9:19–29. doi: 10.4137/JCD.S39824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu D., Liu Z., Wang Y., Zhang Q., Li J., Zhong P., Xie Z., Ji A., Li Y. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Alleviates High-Fat Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease via Inhibition of Apoptosis and Promotion of Autophagy through the ROS/MAPK Signaling Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021;2021:5599997. doi: 10.1155/2021/5599997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Portt L., Norman G., Clapp C., Greenwood M., Greenwood M.T. Anti-apoptosis and cell survival: A review. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1813:238–259. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kanda T., Matsuoka S., Yamazaki M., Shibata T., Nirei K., Takahashi H., Kaneko T., Fujisawa M., Higuchi T., Nakamura H., et al. Apoptosis and non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2661–2672. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i25.2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gross A., McDonnell J.M., Korsmeyer S.J. BCL-2 family members and the mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1899–1911. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dludla P.V., Nkambule B.B., Mazibuko-Mbeje S.E., Nyambuya T.M., Marcheggiani F., Cirilli I., Ziqubu K., Shabalala S.C., Johnson R., Louw J., et al. N-Acetyl Cysteine Targets Hepatic Lipid Accumulation to Curb Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in NAFLD: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Literature. Antioxidants. 2020;9:1283. doi: 10.3390/antiox9121283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maurya R.P., Prajapat M.K., Singh V.P., Roy M., Todi R., Bosak S., Singh S.K., Chaudhary S., Kumar A., Morekar S.R. Serum Malondialdehyde as a Biomarker of Oxidative Stress in Patients with Primary Ocular Carcinoma: Impact on Response to Chemotherapy. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2021;15:871–879. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S287747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boaz M., Matas Z., Biro A., Katzir Z., Green M., Fainaru M., Smetana S. Serum malondialdehyde and prevalent cardiovascular disease in hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1078–1083. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ray P.D., Huang B.W., Tsuji Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell. Signal. 2012;24:981–990. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu D., Xu M., Jeong S., Qian Y., Wu H., Xia Q., Kong X. The Role of Nrf2 in Liver Disease: Novel Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:1428. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raghunath A., Sundarraj K., Nagarajan R., Arfuso F., Bian J., Kumar A.P., Sethi G., Perumal E. Antioxidant response elements: Discovery, classes, regulation and potential applications. Redox. Biol. 2018;17:297–314. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li L., Chu X., Yao Y., Cao J., Li Q., Ma H. (−)-Hydroxycitric Acid Alleviates Oleic Acid-Induced Steatosis, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation in Primary Chicken Hepatocytes by Regulating AMP-Activated Protein Kinase-Mediated Reactive Oxygen Species Levels. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020;68:11229–11241. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c04648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Surai P.F. Silymarin as a Natural Antioxidant: An Overview of the Current Evidence and Perspectives. Antioxidants. 2015;4:204–247. doi: 10.3390/antiox4010204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fogacci F., Banach M., Cicero A.F.G. Resveratrol effect on patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A matter of dose and treatment length. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018;20:1798–1799. doi: 10.1111/dom.13324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li L., Peng M., Ge C., Yu L., Ma H. (-)-Hydroxycitric Acid Reduced Lipid Droplets Accumulation Via Decreasing Acetyl-Coa Supply and Accelerating Energy Metabolism in Cultured Primary Chicken Hepatocytes. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2017;43:812–831. doi: 10.1159/000481564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Checa J., Aran J.M. Reactive Oxygen Species: Drivers of Physiological and Pathological Processes. J. Inflamm. Res. 2020;13:1057–1073. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S275595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee Y.K., Park J.E., Lee M., Hardwick J.P. Hepatic lipid homeostasis by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma 2. Liver Res. 2018;2:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.livres.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matsusue K., Gavrilova O., Lambert G., Brewer H.B., Jr., Ward J.M., Inoue Y., LeRoith D., Gonzalez F.J. Hepatic CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha mediates induction of lipogenesis and regulation of glucose homeostasis in leptin-deficient mice. Mol. Endocrinol. 2004;18:2751–2764. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang K. Molecular mechanisms of hepatic apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reed J.C., Jurgensmeier J.M., Matsuyama S. Bcl-2 family proteins and mitochondria. Bba-Bioenergetics. 1998;1366:127–137. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(98)00108-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nisha V.M., Priyanka A., Anusree S.S., Raghu K.G. (-)-Hydroxycitric acid attenuates endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated alterations in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by protecting mitochondria and downregulating inflammatory markers. Free Radic. Res. 2014;48:1386–1396. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2014.959514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yamaguchi F., Ariga T., Yoshimura Y., Nakazawa H. Antioxidative and anti-glycation activity of garcinol from Garcinia indica fruit rind. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000;48:180–185. doi: 10.1021/jf990845y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kolodziejczyk J., Masullo M., Olas B., Piacente S., Wachowicz B. Effects of garcinol and guttiferone K isolated from Garcinia cambogia on oxidative/nitrative modifications in blood platelets and plasma. Platelets. 2009;20:487–492. doi: 10.3109/09537100903165182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Swiderska M., Maciejczyk M., Zalewska A., Pogorzelska J., Flisiak R., Chabowski A. Oxidative stress biomarkers in the serum and plasma of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Can plasma AGE be a marker of NAFLD? Oxidative stress biomarkers in NAFLD patients. Free Radic. Res. 2019;53:841–850. doi: 10.1080/10715762.2019.1635691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhou X., Fouda S., Li D., Zhang K., Ye J.M. Involvement of the Autophagy-ER Stress Axis in High Fat/Carbohydrate Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutrients. 2020;12:2626. doi: 10.3390/nu12092626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lebeaupin C., Vallee D., Hazari Y., Hetz C., Chevet E., Bailly-Maitre B. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling and the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2018;69:927–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Delli Bovi A.P., Marciano F., Mandato C., Siano M.A., Savoia M., Vajro P. Oxidative Stress in Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. An Updated Mini Review. Front. Med. 2021;8:595371. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.595371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fernando D.H., Forbes J.M., Angus P.W., Herath C.B. Development and Progression of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: The Role of Advanced Glycation End Products. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:5037. doi: 10.3390/ijms20205037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim Y.J., Choi M.S., Park Y.B., Kim S.R., Lee M.K., Jung U.J. Garcinia Cambogia attenuates diet-induced adiposity but exacerbates hepatic collagen accumulation and inflammation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4689–4701. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i29.4689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Clouatre D.L., Preuss H.G. Hydroxycitric acid does not promote inflammation or liver toxicity. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8160–8162. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i44.8160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material.