Abstract

Simple Summary

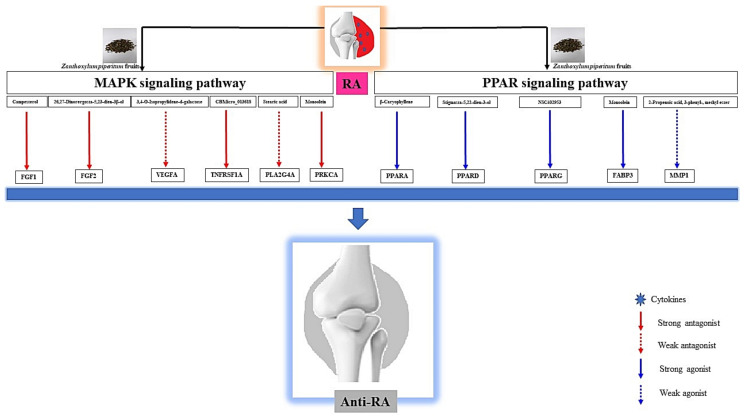

The aim of the study is to investigate the bioactives of Zanthoxylum piperitum fruits on rheumatoid arthritis. The methodology to identify the relationship between signaling pathways, targets, and bioactives is based on network pharmacology. The results show that Zanthoxylum piperitum fruits might alleviate inflammatory symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. Thus, we suggest that Zanthoxylum piperitum fruit is a promising herbal plant to reduce the level of cytokines against rheumatoid arthritis.

Abstract

Zanthoxylum piperitum fruits (ZPFs) have been demonstrated favorable clinical efficacy on rheumatoid arthritis (RA), but its compounds and mechanisms against RA have not been elucidated. This study was to investigate the compounds and mechanisms of ZPFs to alleviate RA via network pharmacology. The compounds from ZPFs were detected by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and screened to select drug-likeness compounds through SwissADME. Targets associated with bioactive compounds or RA were identified utilizing bioinformatics databases. The signaling pathways related to RA were constructed; interactions among targets; and signaling pathways-targets-compounds (STC) were analyzed by RPackage. Finally, a molecular docking test (MDT) was performed to validate affinity between targets and compounds on key signaling pathway(s). GC-MS detected a total of 85 compounds from ZPFs, and drug-likeness properties accepted all compounds. A total of 216 targets associated with compounds 3377 RA targets and 101 targets between them were finally identified. Then, a bubble chart exhibited that inactivation of MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) and activation of PPAR (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor) signaling pathway might be key pathways against RA. Overall, this work suggests that seven compounds from ZPFs and eight targets might be multiple targets on RA and provide integrated pharmacological evidence to support the clinical efficacy of ZPFs on RA.

Keywords: Zanthoxylum piperitum fruits, rheumatoid arthritis, network pharmacology, MAPK signaling pathway, PPAR signaling pathway

1. Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a long-term systemic autoimmune disorder that deteriorates the synovial joints and is associated with gradual disability [1]. RA is a progressive inflammation caused by joint damage and its functional loss around the articular [2,3]. RA can present irrespective of age, diagnosed in around 1% of the population, brings huge social-economic burden [4]. The main factor causing RA is uncontrollable cytokine secretion due to bone damage; however, the etiology of RA is unknown [5,6]. Commonly, the anti-RA drugs administered are disease-modifying arthritis drugs (DMARDs) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in most countries [7]. At present, prolonged administration of these drugs is involved in severe side effects such as upset stomach, nephrotoxicity, and electrolyte imbalance [8,9]. In contrast, an animal test demonstrated that the repeated dose treatment of plant leaf methanolic extraction with anti-RA efficacy did not alter liver and kidney function [10]. It implies that herbal medicine extracts against RA are better clinical safety than unnatural compounds. For a long time, herbal plants treating RA were essential resources due to their excellent clinical efficacy and low adverse effects [11].

Zanthoxylum piperitum (ZP) belongs to the Rutaceae family, which has been chiefly used as a condiment of food in Korea, Japan, and China [12]. It was reported that essential oil in ZP showed a 38% reduction of nitric oxide (NO) related to the occurrence and progression of inflammatory joint disease [13]. Another report demonstrated that the peel of ZP has potent anti-inflammatory activities by suppressing nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and caspase-1 activation in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced RAW264.7 cells [14]. The studies give a hint that ZP might be a herbal medicine to alleviate RA. So far, active compounds and pharmacological mechanisms of ZPFs against RA have not been elucidated. Hence, studies of active compounds and mechanisms of ZPFs against RA should be investigated to prove their therapeutic value.

Network pharmacology is an integrated analytical methodology to understand multiple elements such as compounds, targets and pathways [15]. Network pharmacology can unravel the mechanism of compounds in herbal plants with an integrated concept [16]. Additionally, network pharmacology makes a point of “multiple-targets, multiple-compounds”, instead of “one-target, one-compound” [17]. Therefore, network pharmacology is an optimal method to explicate herbal plant issues. Currently, network pharmacology has been utilized to prove bioactive compounds and mechanisms of herbal plants against complex diseases [18,19].

Hence, network pharmacology was utilized to uncover the pharmacological mechanisms of bioactive compounds of ZPFs against RA. Firstly, compounds of ZPFs methanolic extraction identified from GC-MS filtered out drug-likeness candidates on a physicochemical descriptor tool. Secondly, targets related to filtered compounds were retrieved by public bioinformatic databases, and final overlapping targets calculated between compounds and RA targets retrieved by public disease target databases. Thirdly, a key target on protein–protein interaction (PPI) was identified, and two key signaling pathways of ZPFs against RA were identified by analyzing the final overlapping targets. Then, another key target of signaling pathways related to the occurrence and development of RA was identified by analyzing targets associated with signaling pathways. Finally, a molecular docking test (MDT) was carried out to find po from ZPFs against RA on each target related directly to two key signaling pathways. The workflow diagram is exhibited in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Workflow chart of network pharmacology analysis of ZPFs against RA.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material Collection and Classification

The Zanthoxylum piperitum fruits (ZPFs) were collected from (latitude: 37.628975, longitude: 126.742978), Gyeonggi-do, Korea, in August 2020, and the plant was identified by Dr. Dong Ha Cho, Plant biologist and Professor, Department of Bio-Health Convergence, College of Biomedical Science, Kangwon National University. A voucher number (UUC 270) has been stored at Kenaf Corporation in the Department of Bio-Health Convergence, and the material can be used only for research purposes.

2.2. Plant Preparation, Extraction

The ZPFs were dried in a shady area at room temperature (20–22 °C) for 21 days, and dried ZPFs made powder using an electric blender. Approximately 50 g of ZPFs powder was soaked in 800 mL of 100% methanol (Daejung, Siheung city, Gyeonggi-do, Korea) for 10 days and repeated three times to achieve a high yield rate. The solvent extract was collected, filtered, and evaporated using a vacuum evaporator (IKA- RV8, Staufen city, Germany). The evaporated sample was dried under a boiling water bath (IKA-HB10, Staufen city, Germany) at 40 °C for around 8 h to obtain solid extraction.

2.3. GC-MS Analysis Condition

Agilent 7890A was used to carry out GC-MS analysis. GC was equipped with a DB-5 (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) capillary column. Initially, the instrument was maintained at a temperature of 100 °C for 2.1 min. The temperature was rose to 300 °C at the rate of 25 °C/min and maintained for 20 min. Injection port temperature and helium flow rate were ensured as 250 °C and 1.5 mL/min, respectively. The ionization voltage was 70 eV. The samples injected in split mode at 10:1. The MS scan range was set at 35–900 (m/z). The fragmentation patterns of mass spectra were compared with those stored in the using W8N05ST Library MS database (analyzed 28 April 2021). The percentage of each compound was calculated from the relative peak area of each compound in the chromatogram. The concept of integration was used in the ChemStation integrator algorithms (analyzed 28 April 2021) [20].

2.4. Chemical Compounds Identification and Drug-Likeness Screening

The chemical compounds from ZPFs were identified through GC-MS analysis. The compounds detected by GC-MS confirmed “drug-likeness” physicochemical property via Lipinski’s rule on SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/) (accessed on 14 May 2021). The filtered compounds converted into SMILES (simplified molecular input line entry system) (accessed on 14 May 2021) format through PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) (accessed on 14 May 2021).

2.5. Targets Associated with Compounds from ZPFs or Rheumatoid Arthritis

Targets related to the compounds were identified via both Similarity Ensemble Approach (SEA) (http://sea.bkslab.org/) (accessed on 16 May 2021) [21] and SwissTargetPrediction (STP) (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/) (accessed on 16 May 2021) [22] with “Homo Sapiens” mode, both of which is founded on SMILES (accessed on 14 May 2021). The RA-associated targets on humans were retrieved with DisGeNET (https://www.disgenet.org/) (accessed on 17 May 2021), OMIM (https://www.omim.org/) (accessed on 17 May 2021) and literature. The overlapping targets between compounds of ZPFs and RA-associated targets indicated by VENNY 2.1 (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/) (accessed on 18 May 2021).

2.6. PPI Networks and Bubble Chart

STRING (https://string-db.org/) (accessed on 19 May 2021) [23] was utilized to analyze the PPI network with final overlapping targets. The RPackage was utilized to identify the degree of value. Then, signaling pathways associated with the occurrence and development of RA were visualized on a bubble chart by RPackage; two key signaling pathways with the highest and the lowest rich factor were selected to analyze the relationships against RA.

2.7. Construction of STC Networks

The STC networks were utilized to construct a size plot based on the degree of values. In this size map, green rectangles (nodes) represented signaling pathways; gold triangles (nodes) stood for target proteins, and red circles (nodes) stood for compounds; its size represented degree value. The size of gold triangles represented the amount of connectivity with signaling pathways; the size of red circles represented the amount of connectivity with target proteins. The combined networks were constructed by using RPackage (analyzed 20 May 2021).

2.8. Preparation of Targets for MDT

Firstly, two targets of MAPK signaling pathway, i.e., FGF2 (PDB ID: 1IIL), VEGFA (PDB ID: 3V2A), and one target of PPAR signaling pathway, i.e., PPARG (PDB ID: 3E00), were identified on STRING via RCSB PDB (https://www.rcsb.org/) (accessed on 21 May 2021). The final three targets selected as .pdb format were converted into .pdbqt format via Autodock (http://autodock.scripps.edu/) (accessed on 21 May 2021).

2.9. Preparation of Compounds from ZPFs for MDT

The ligand molecules were converted .sdf from PubChem into .pdb format using Pymol (accessed on 21 May 2021), and the ligand molecules were converted into .pdbqt format through Autodock (accessed on 21 May 2021).

2.10. Preparation of Positive Standard Ligands for MDT

The number of two positive ligands on FGF2 antagonists, i.e., NSC172285 (PubChem ID: 299405), NSC37204 (PubChem ID: 235612), and the number of one positive ligand on VEGFA antagonist, i.e., BAW2881 (PubChem ID: 16004702), the number of three positive ligands on PPARG antagonists, i.e., Pioglitazone (PubChem ID: 4829), Rosiglitazone (PubChem ID: 77999), Lobeglitazone (PubChem ID: 9826451) were selected to verify the docking score.

2.11. Ligand-Protein Docking

The ligand molecules were docked with target proteins utilizing autodock4 by setting up four energy ranges and eight exhaustiveness as default to obtain 10 different poses of ligand molecules [24]. The 2D binding interactions were used with LigPlot+ v.2.2 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/software/LigPlus/) (accessed on 21 May 2021). After docking, ligands of the lowest binding energy (highest affinity) were selected to visualize the ligand–protein interaction in Pymol (Schrödinger, New York, NY, USA).

2.12. Toxicological Properties Prediction by AdmetSAR

Toxicological properties of the key bioactive were established using the admetSAR web-service tool (http://lmmd.ecust.edu.cn/admetsar1/predict/) (accessed on 23 May 2021) because toxicity is an essential factor to develop new drugs. Hence, Ames toxicity, carcinogenic properties, acute oral toxicity, and rat acute toxicity were predicted by admetSAR (East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai, China).

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Compounds from ZPFs

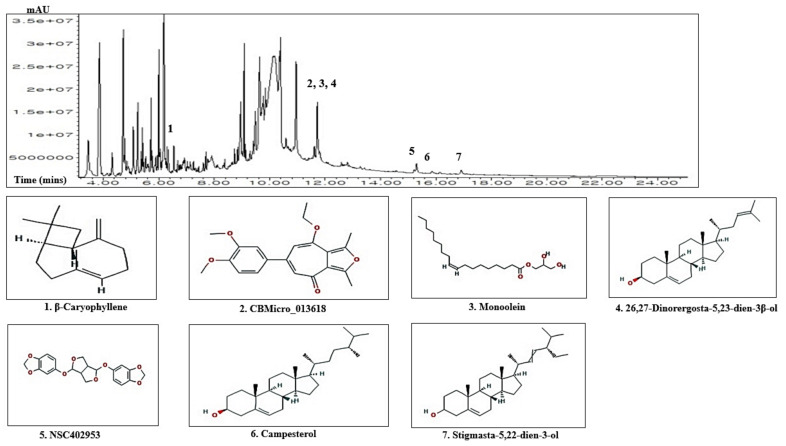

A total of 85 chemical compounds and its seven key chemical compounds in ZPFs were detected by the GC-MS analysis (Figure 2), and the name of compounds, PubChem ID, retention time (mins), and peak area (%) were enlisted in Table 1. Lipinski’s rules accepted all 85 compounds (molecular weight ≤500g/mol; Moriguchi octanol-water partition coefficient ≤4.15; number of nitrogen or oxygen ≤10; number of NH or OH ≤5), and all chemical compounds satisfied with the criteria of “Abbott Bioavailability Score (>0.1)” through SwissADME. The TPSA (topological polar surface area) value of chemical compounds was also accepted (Table 2).

Figure 2.

A typical GC-MS peak of ZPFs methanolic extract and the number of seven key compounds.

Table 1.

A list of 85 chemical compounds identified from ZPFs via GC-MS and profiling of bioactivities.

| No. | Compounds | Pubchem ID | RT (mins) | Area (%) | Pharmacological Activities (Reference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Myrcene | 31253 | 3.462 | 1.49 | Antibacterial, Antioxidant, Fungicide |

| 2 | 3(5)-[[1,2-Dihydroxy-3-propoxy]methyl]-4-hydroxy-1H-pyrazole-5(3)-carboxamide | 135747301 | 3.683 | 0.09 | No reported |

| 3 | β-Phellandrene | 11142 | 3.866 | 4.28 | Fungicide |

| 4 | Hex-3-yne | 13568 | 3.971 | 0.10 | No reported |

| 5 | 3-Hydroxycyclohexanone | 439950 | 4.087 | 0.06 | No reported |

| 6 | Isopropyl hexanoate | 16832 | 4.145 | 0.12 | No reported |

| 7 | Terpinolene | 11463 | 4.250, 4.318 | 0.59 | Fungicide, Antioxidant |

| 8 | Vinylcyclooctane | 93331 | 4.520 | 0.07 | No reported |

| 9 | 2-Tetradecynoic acid | 324386 | 4.587 | 0.10 | No reported |

| 10 | Citronellal | 7794 | 4.721 | 2.75 | Antibacterial, Fungicide |

| 11 | 3-Hydroxy-2,3-dihydromaltol | 119838 | 4.779 | 0.67 | No reported |

| 12 | Pulegol | 92793 | 4.856 | 0.29 | No reported |

| 13 | Octanoic acid | 379 | 4.923 | 0.24 | Candidicide, Fungicide |

| 14 | (E)-4-Undecenal | 5283357 | 4.981 | 0.10 | No reported |

| 15 | 4-Isopropyl-2-cyclohexenone | 92780 | 5.087 | 1.04 | No reported |

| 16 | Citronellol | 8842 | 5.241 | 1.20 | Antibacterial, Candidicide, Sedative |

| 17 | (E)-beta-Ocimene | 5281553 | 5.366 | 0.39 | Insecticide |

| 18 | 3,7-Dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-ol | 4458 | 5.414 | 0.65 | No reported |

| 19 | Spiro[4 .4]nona-1,3-diene, 1,2-dimethyl- | 570800 | 5.452 | 0.21 | No reported |

| 20 | Piperitone | 6987 | 5.529 | 0.41 | Antiasthmatic |

| 21 | Nonanoic acid | 8158 | 5.606 | 0.42 | Perfumery |

| 22 | 8,8-Dimethoxy-2,6-dimethyloct-2-ene | 102507 | 5.721 | 0.98 | No reported |

| 23 | p-Isopropylbenzyl formate | 105515 | 5.760 | 0.40 | No reported |

| 24 | Citronellic acid | 10402 | 5.895 | 0.55 | No reported |

| 25 | α-Terpinene | 7462 | 5.952 | 0.24 | Antispasmodic |

| 26 | 2,6-Octadiene, 2,6-dimethyl- | 5365898 | 6.000 | 1.60 | No reported |

| 27 | Terpinyl propionate | 62328 | 6.048 | 0.43 | No reported |

| 28 | Geranyl acetate | 1549026 | 6.193 | 4.60 | Sedative |

| 29 | 3-Methylcyclohexene | 11573 | 6.250 | 0.21 | No reported |

| 30 | 1,4-Dimethyl-4beta-methoxy-2,5-cyclohexadien-1α-ol | 12561656 | 6.298 | 0.33 | No reported |

| 31 | 2-Propenoic acid, 3-phenyl-, methyl ester | 7644 | 6.346 | 0.49 | No reported |

| 32 | 6-Methylenespiro[4.5]decane | 564762 | 6.471 | 0.07 | No reported |

| 33 | β-Caryophyllene | 5281515 | 6.539 | 0.67 | Antibacterial, Antiinflammation |

| 34 | Bergamotane | 86000267 | 6.625 | 0.09 | No reported |

| 35 | 3-Methyl-4,7-dioxo-oct-2-enal | 5363705 | 6.693 | 0.30 | No reported |

| 36 | 2,6-Dimethyl-3,5,7-octatriene-2-ol, Z,Z- | 5363692 | 6.779 | 0.24 | No reported |

| 37 | 2-Dodecenoic acid | 5282729 | 6.818 | 0.12 | No reported |

| 38 | 1,6,10-Dodecatrien-3-ol, 3,7,11-trimethyl- | 8888 | 6.885 | 0.35 | No reported |

| 39 | 1-Methyldecahydronaphthalene | 34193 | 6.943 | 0.46 | No reported |

| 40 | Cadina-1(10),4-diene | 10223 | 7.029 | 0.34 | No reported |

| 41 | 2-(4-Methylcyclohexyl)prop-2-en-1-ol | 543946 | 7.135 | 0.42 | No reported |

| 42 | Tetradec-13-enal | 522841 | 7.250 | 0.24 | No reported |

| 43 | 9-Octadecenoic acid | 965 | 7.308 | 0.15 | Antiinflammation, Antileukotriene |

| 44 | 1,2-Di-but-2-enyl-cyclohexane | 5367574 | 7.375 | 0.10 | No reported |

| 45 | 4,12,12-trimethyl-9-methylene-5-oxatricyclo[8.2.0.04,6]dodecane | 73555586 | 7.433 | 0.11 | No reported |

| 46 | 3,4-O-Isopropylidene-d-galactose | 54504880 | 7.568 | 0.08 | No reported |

| 47 | 2-Hexenoic acid, 6-cyclohexyl- | 5367614 | 7.616 | 0.22 | No reported |

| 48 | Heptadec-8-ene | 520230 | 7.693 | 0.35 | No reported |

| 49 | Octane | 356 | 7.779 | 0.35 | No reported |

| 50 | Myristic acid | 11005 | 7.827, 8.096 | 0.44 | Anticancer, Antioxidant |

| 51 | D-(-)-Kinic Acid | 1064 | 7.914 | 1.35 | No reported |

| 52 | Nonadecanoic acid | 12591 | 8.135 | 0.35 | No reported |

| 53 | 10-Bromoundecanoic acid | 543401 | 8.337, 8.385 | 0.77 | No reported |

| 54 | Stearic acid | 5281 | 8.520 | 0.23 | Hypocholesterolemic |

| 55 | Cysteamine S-sulfate | 76242 | 8.587, 9.231, 9.298 | 1.27 | No reported |

| 56 | Limonene dioxide | 232703 | 8.635 | 0.23 | No reported |

| 57 | 2,6-Dimethyl-4-nitro-3-phenyl-cyclohexanone | 562366 | 8.664 | 0.26 | No reported |

| 58 | Methyl palmitate | 8181 | 8.731 | 0.46 | No reported |

| 59 | 2,6-Dimethyl-1,3,6-heptatriene | 5368331 | 8.846 | 0.68 | No reported |

| 60 | Palmitic acid | 985 | 8.962, 9.020 | 2.65 | Antioxidant, Pesticide |

| 61 | Neral | 643779 | 9.077 | 1.58 | Antibacterial, Antispasmodic |

| 62 | 2-Methyl-6-methylene-1,7-octadien-3-one | 93231 | 9.125 | 0.75 | No reported |

| 63 | Bis(3-benzyl-2,4-pentanedionato)palladium(II) | 5363840 | 9.423 | 1.03 | No reported |

| 64 | Pentamethylbenzenesulfonyl chloride | 590180 | 9.491, 9.635 | 6.52 | No reported |

| 65 | Myrtenal | 61130 | 9.769 | 3.77 | Antimalarial, Antiplasmodial |

| 66 | N,N-Dimethyl-2-phenylethen-1-amine | 23277871 | 10.154, 10.183 | 20.61 | No reported |

| 67 | Allyl(chloromethyl)dimethylsilane | 556526 | 10.394 | 7.64 | No reported |

| 68 | Cyclohexene, 4-(4-ethylcyclohexyl)-1-pentyl- | 543386 | 10.596 | 1.64 | No reported |

| 69 | 3-Epicycloeucalenol | 543796 | 10.654 | 1.09 | No reported |

| 70 | 2,5-Furandione, 3-dodecenyl- | 5362708 | 10.750 | 0.61 | No reported |

| 71 | 1-cinnamyl-3-methylindole-2-carbaldehyde | N/A | 10.875 | 1.35 | No reported |

| 72 | Glyceryl palmitate | 14900 | 10.962 | 4.82 | No reported |

| 73 | 2-Methyl-Z,Z-3,13-octadecadienol | 5364412 | 11.414 | 0.37 | No reported |

| 74 | Pentadeca-2,3,6,9,12,13-hexaen-8-one, 2,5,5,11,11,14-hexamethyl- | 5370200 | 11.519 | 0.51 | No reported |

| 75 | CBMicro_013618 | 1109374 | 11.616 | 1.04 | No reported |

| 76 | Monoolein | 5283468 | 11.721 | 2.02 | Antioxidant |

| 77 | Cyclohexene, 4-(4-ethylcyclohexyl)-1-pentyl- | 543386 | 11.808, 12.596 | 1.56 | No reported |

| 78 | Cedrane-8,13-diol | 188457 | 12.654 | 0.12 | No reported |

| 79 | 26,27-Dinorergosta-5,23-dien-3β-ol | 22213488 | 12.721 | 0.18 | No reported |

| 80 | Cholest-4-en-3-one, 14-methyl- | 277841 | 13.279 | 0.07 | No reported |

| 81 | (+)-Sesamolin | 585998 | 15.221 | 0.08 | No reported |

| 82 | NSC402953 | 345349 | 15.308 | 0.32 | No reported |

| 83 | Campesterol | 173183 | 15.866 | 0.12 | Antioxidant, Hypocholesterolemic |

| 84 | Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol | 53870683 | 16.144 | 0.06 | Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, Antidiabetic |

| 85 | Clionasterol | 457801 | 16.923 | 0.15 | Anticancer, Antidaibetic, Antioxidant |

Table 2.

Physicochemical properties of chemical compounds for good oral bioavailability and cell membrane permeability.

| No. | Compounds | Lipinski Rules | Lipinski’s Violations | Bioavailability Score | TPSA(Ų) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MW | HBA | HBD | MLog P | |||||

| <500 | <10 | ≤5 | ≤4.15 | ≤1 | > 0.1 | <140 | ||

| 1 | Myrcene | 136.23 | 0 | 0 | 3.56 | 0 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 3(5)-[[1,2-Dihydroxy-3-propoxy]methyl]-4-hydroxy-1H-pyrazole-5(3)-carboxamide | 231.21 | 6 | 5 | −2.70 | 0 | 0.55 | 141.69 |

| 3 | β-Phellandrene | 136.23 | 0 | 0 | 3.27 | 0 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 4 | Hex-3-yne | 82.14 | 0 | 0 | 3.37 | 0 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 5 | 3-Hydroxycyclohexanone | 114.14 | 2 | 1 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.55 | 37.30 |

| 6 | Isopropyl hexanoate | 158.24 | 2 | 0 | 2.28 | 0 | 0.55 | 26.30 |

| 7 | Terpinolene | 136.23 | 0 | 0 | 3.27 | 0 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 8 | Vinylcyclooctane | 138.25 | 0 | 0 | 4.29 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 9 | 2-Tetradecynoic acid | 224.34 | 2 | 1 | 3.58 | 0 | 0.85 | 37.30 |

| 10 | Citronellal | 154.25 | 1 | 0 | 2.59 | 0 | 0.55 | 17.07 |

| 11 | 3-Hydroxy-2,3-dihydromaltol | 144.13 | 4 | 2 | −1.77 | 0 | 0.85 | 66.76 |

| 12 | Pulegol | 154.25 | 1 | 1 | 2.30 | 0 | 0.55 | 20.23 |

| 13 | Octanoic acid | 144.21 | 2 | 1 | 1.96 | 0 | 0.85 | 37.30 |

| 14 | (E)-4-Undecenal | 168.28 | 1 | 0 | 2.88 | 0 | 0.55 | 17.07 |

| 15 | 4-Isopropyl-2-cyclohexenone | 138.21 | 1 | 0 | 1.89 | 0 | 0.55 | 17.07 |

| 16 | Citronellol | 156.27 | 1 | 1 | 2.70 | 0 | 0.55 | 20.23 |

| 17 | (E)--Ocimene | 136.23 | 0 | 0 | 3.56 | 0 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 18 | 3,7-Dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-ol | 154.25 | 1 | 1 | 2.59 | 0 | 0.55 | 20.23 |

| 19 | Spiro[4.4]nona-1,3-diene, 1,2-dimethyl- | 148.24 | 0 | 0 | 3.56 | 0 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 20 | Piperitone | 152.23 | 1 | 0 | 2.20 | 0 | 0.55 | 17.07 |

| 21 | Nonanoic acid | 158.24 | 2 | 1 | 2.28 | 0 | 0.85 | 37.30 |

| 22 | 8,8-Dimethoxy-2,6-dimethyloct-2-ene | 200.32 | 2 | 0 | 2.75 | 0 | 0.55 | 18.46 |

| 23 | p-Isopropylbenzyl formate | 178.23 | 2 | 0 | 2.58 | 0 | 0.55 | 26.30 |

| 24 | Citronellic acid | 170.25 | 2 | 1 | 2.47 | 0 | 0.85 | 37.30 |

| 25 | alpha-Terpinene | 136.23 | 0 | 0 | 3.27 | 0 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 26 | 2,6-Octadiene, 2,6-dimethyl- | 138.25 | 0 | 0 | 3.66 | 0 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 27 | Terpinyl propionate | 210.31 | 2 | 0 | 2.92 | 0 | 0.55 | 26.30 |

| 28 | Geranyl acetate | 196.29 | 2 | 0 | 2.95 | 0 | 0.55 | 26.30 |

| 29 | 3-Methylcyclohexene | 96.17 | 0 | 0 | 3.33 | 0 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 30 | 1,4-Dimethyl-4β-methoxy-2,5-cyclohexadien-1α-ol | 154.21 | 2 | 1 | 0.97 | 0 | 0.55 | 29.46 |

| 31 | 2-Propenoic acid, 3-phenyl-, methyl ester | 162.19 | 2 | 0 | 2.20 | 0 | 0.55 | 26.30 |

| 32 | 6-Methylenespiro[4.5]decane | 150.26 | 0 | 0 | 4.58 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 33 | beta-Caryophyllene | 204.35 | 0 | 0 | 4.63 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 34 | Bergamotane | 208.38 | 0 | 0 | 5.80 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 35 | 3-Methyl-4,7-dioxo-oct-2-enal | 168.19 | 3 | 0 | 0.29 | 0 | 0.55 | 51.21 |

| 36 | 2,6-Dimethyl-3,5,7-octatriene-2-ol, Z,Z- | 152.23 | 1 | 1 | 2.49 | 0 | 0.55 | 20.23 |

| 37 | 2-Dodecenoic acid | 198.30 | 2 | 1 | 3.04 | 0 | 0.85 | 37.30 |

| 38 | 1,6,10-Dodecatrien-3-ol, 3,7,11-trimethyl- | 222.37 | 1 | 1 | 3.86 | 0 | 0.55 | 20.23 |

| 39 | 1-Methyldecahydronaphthalene | 152.28 | 0 | 0 | 4.72 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 40 | Cadina-1(10),4-diene | 204.35 | 1 | 0 | 4.63 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 41 | 2-(4-Methylcyclohexyl)prop-2-en-1-ol | 154.25 | 1 | 1 | 2.30 | 0 | 0.55 | 20.23 |

| 42 | Tetradec-13-enal | 210.36 | 1 | 0 | 3.70 | 0 | 0.55 | 17.07 |

| 43 | 9-Octadecenoic acid | 282.46 | 2 | 1 | 4.57 | 1 | 0.85 | 37.30 |

| 44 | 1,2-Di-but-2-enyl-cyclohexane | 192.34 | 0 | 0 | 4.37 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 45 | 4,12,12-trimethyl-9-methylene-5-oxatricyclo[8.2.0.04,6]dodecane | 220.35 | 1 | 0 | 3.67 | 0 | 0.55 | 12.53 |

| 46 | 3,4-O-Isopropylidene-d-galactose | 220.22 | 6 | 3 | −1.34 | 0 | 0.55 | 88.38 |

| 47 | 2-Hexenoic acid, 6-cyclohexyl- | 196.29 | 2 | 1 | 2.65 | 0 | 0.85 | 37.30 |

| 48 | Heptadec-8-ene | 238.45 | 0 | 0 | 6.54 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 49 | Octane | 114.23 | 0 | 0 | 4.20 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 50 | Myristic acid | 228.37 | 2 | 1 | 3.69 | 0 | 0.85 | 37.30 |

| 51 | D-(-)-Kinic Acid | 192.17 | 6 | 5 | −2.14 | 0 | 0.55 | 118.22 |

| 52 | Nonadecanoic acid | 298.50 | 2 | 1 | 4.91 | 1 | 0.85 | 37.30 |

| 53 | 10-Bromoundecanoic acid | 265.19 | 2 | 1 | 3.29 | 0 | 0.85 | 37.30 |

| 54 | Stearic acid | 284.48 | 2 | 1 | 4.67 | 1 | 0.85 | 37.30 |

| 55 | Cysteamine S-sulfate | 157.21 | 4 | 2 | −1.51 | 0 | 0.55 | 114.07 |

| 56 | Limonene dioxide | 168.23 | 2 | 0 | 1.52 | 0 | 0.55 | 25.06 |

| 57 | 2,6-Dimethyl-4-nitro-3-phenyl-cyclohexanone | 247.29 | 3 | 0 | 1.66 | 0 | 0.55 | 62.89 |

| 58 | Methyl palmitate | 270.45 | 2 | 0 | 4.44 | 1 | 0.55 | 26.30 |

| 59 | 2,6-Dimethyl-1,3,6-heptatriene | 122.21 | 0 | 0 | 3.26 | 0 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 60 | Palmitic acid | 256.42 | 2 | 1 | 4.19 | 1 | 0.85 | 37.30 |

| 61 | Neral | 152.23 | 1 | 0 | 2.49 | 0 | 0.55 | 17.07 |

| 62 | 2-Methyl-6-methylene-1,7-octadien-3-one | 150.22 | 1 | 0 | 2.40 | 0 | 0.55 | 17.07 |

| 63 | Bis(3-benzyl-2,4-pentanedionato)palladium(II) | 486.90 | 4 | 2 | 2.69 | 0 | 0.85 | 74.60 |

| 64 | Pentamethylbenzenesulfonyl chloride | 246.75 | 2 | 0 | 3.04 | 0 | 0.55 | 42.52 |

| 65 | Myrtenal | 150.22 | 1 | 0 | 2.20 | 0 | 0.55 | 17.07 |

| 66 | N,N-Dimethyl-2-phenylethen-1-amine | 147.22 | 0 | 0 | 2.40 | 0 | 0.55 | 3.24 |

| 67 | Allyl(chloromethyl)dimethylsilane | 148.71 | 0 | 0 | 2.81 | 0 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 68 | Cyclohexene, 4-(4-ethylcyclohexyl)-1-pentyl- | 262.47 | 0 | 0 | 6.61 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 69 | 3-Epicycloeucalenol | 426.72 | 1 | 1 | 6.92 | 1 | 0.55 | 20.23 |

| 70 | 2,5-Furandione, 3-dodecenyl- | 266.38 | 3 | 0 | 3.53 | 0 | 0.55 | 43.37 |

| 71 | 1-cinnamyl-3-methylindole-2-carbaldehyde | 275.34 | 1 | 0 | 3.20 | 0 | 0.55 | 22.00 |

| 72 | Glyceryl palmitate | 330.50 | 4 | 2 | 3.18 | 0 | 0.55 | 66.76 |

| 73 | 2-Methyl-Z,Z-3,13-octadecadienol | 280.49 | 1 | 1 | 4.91 | 1 | 0.55 | 20.23 |

| 74 | Pentadeca-2,3,6,9,12,13-hexaen-8-one, 2,5,5,11,11,14-hexamethyl- | 298.46 | 1 | 0 | 4.93 | 1 | 0.55 | 17.07 |

| 75 | CBMicro_013618 | 354.40 | 5 | 0 | 1.66 | 0 | 0.55 | 57.90 |

| 76 | Monoolein | 356.54 | 4 | 2 | 3.52 | 0 | 0.55 | 66.76 |

| 77 | Cyclohexene, 4-(4-ethylcyclohexyl)-1-pentyl- | 262.47 | 0 | 0 | 6.61 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| 78 | Cedrane-8,13-diol | 238.37 | 2 | 2 | 2.88 | 0 | 0.55 | 40.46 |

| 79 | 26,27-Dinorergosta-5,23-dien-3β-ol | 370.61 | 1 | 1 | 6.03 | 1 | 0.55 | 20.23 |

| 80 | Cholest-4-en-3-one, 14-methyl- | 398.66 | 1 | 0 | 6.43 | 1 | 0.55 | 17.07 |

| 81 | (+)-Sesamolin | 370.35 | 7 | 0 | 1.85 | 0 | 0.55 | 64.61 |

| 82 | NSC402953 | 386.35 | 8 | 0 | 1.74 | 0 | 0.55 | 73.84 |

| 83 | Campesterol | 400.68 | 1 | 1 | 6.54 | 1 | 0.55 | 20.23 |

| 84 | Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol | 412.69 | 1 | 1 | 6.62 | 1 | 0.55 | 20.23 |

| 85 | Clionasterol | 414.71 | 1 | 1 | 6.73 | 1 | 0.55 | 20.23 |

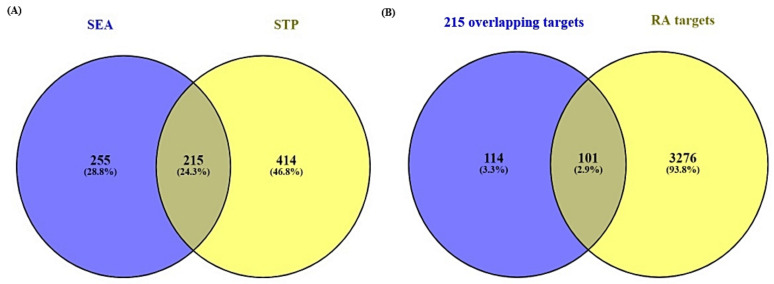

3.2. Overlapping Targets between SEA and STP Related to Chemical Compounds

A total of 470 targets from Similarity Ensemble Approach (SEA) and 629 targets from SwissTargetPrediction (STP) were associated with 85 chemical compounds (Supplementary Table S1). The Venn diagram showed that 215 targets overlapped between the two public databases (Supplementary Table S1) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) The number of 215 overlapping targets between SEA (470 targets) and STP (629 targets). (B) The number of 101 final overlapping targets between 215 overlapping targets from two databases (SEA and STP) and RA associated with targets (3377 targets).

3.3. Overlapping Targets between RA-Related Genes and the Final 101 Overlapping Targets

A total of 3377 targets associated with RA were selected by retrieving from DisGeNET, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) databases and literature (Supplementary Table S2). Venn diagram’s result displayed 101 overlapping targets that were selected between 3377 targets related to RA and the 215 overlapping targets (Figure 3B) (Supplementary Table S3).

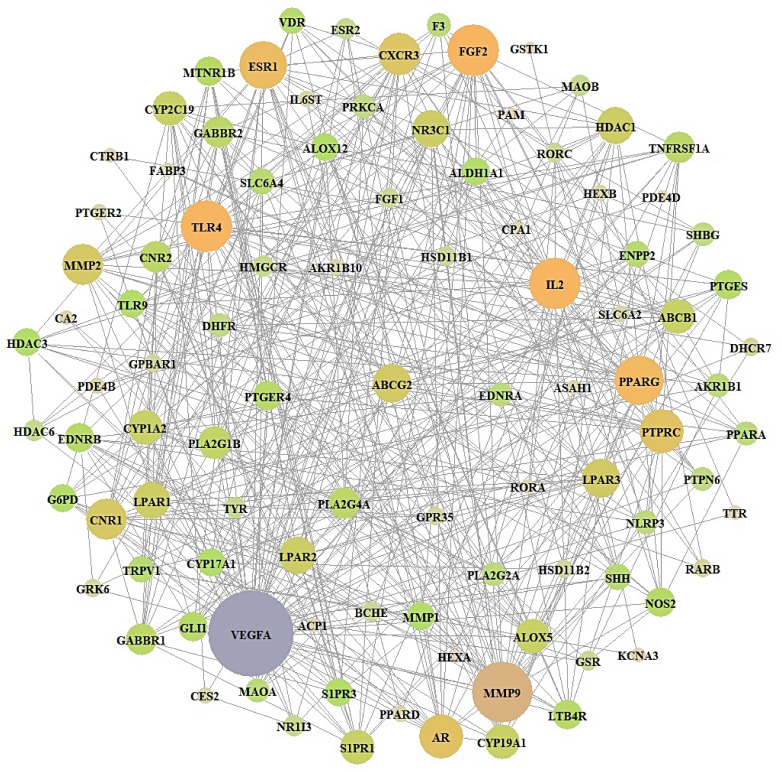

3.4. Acquisition of a Key Target from PPI Networks

From STRING analysis, 99 out of 101 overlapping targets were directly associated with RA occurrence and development, indicating 99 nodes and 469 edges (Figure 4). The two removed targets (CA1 and CA3) had no connectivity to the overlapping 101 targets. In PPI networks, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGFA) was the highest degree (42) and is considered a key target (Table 3).

Figure 4.

PPI networks (99 nodes, 469 edges). The size of the circle: degree of values.

Table 3.

The degree value of target in PPI.

| No. | Target | Degree of Value | No. | Target | Degree of Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VEGFA | 42 | 51 | ENPP2 | 9 |

| 2 | MMP9 | 28 | 52 | PPARA | 8 |

| 3 | TLR4 | 23 | 53 | PLA2G2A | 8 |

| 4 | IL2 | 23 | 54 | NLRP3 | 8 |

| 5 | FGF2 | 23 | 55 | MAOA | 8 |

| 6 | PPARG | 22 | 56 | F3 | 8 |

| 7 | ESR1 | 21 | 57 | EDNRA | 8 |

| 8 | PTPRC | 19 | 58 | AKR1B1 | 8 |

| 9 | AR | 19 | 59 | SHBG | 7 |

| 10 | CXCR3 | 18 | 60 | PTPN6 | 7 |

| 11 | MMP2 | 17 | 61 | PRKCA | 7 |

| 12 | CNR1 | 17 | 62 | DHFR | 7 |

| 13 | LPAR3 | 16 | 63 | TYR | 6 |

| 14 | ABCG2 | 16 | 64 | NR1I3 | 6 |

| 15 | NR3C1 | 15 | 65 | MAOB | 6 |

| 16 | LPAR2 | 15 | 66 | HMGCR | 6 |

| 17 | LPAR1 | 15 | 67 | HDAC6 | 6 |

| 18 | HDAC1 | 15 | 68 | ESR2 | 6 |

| 19 | ABCB1 | 14 | 69 | RORC | 5 |

| 20 | S1PR1 | 14 | 70 | HSD11B1 | 5 |

| 21 | CYP2C19 | 14 | 71 | GSR | 5 |

| 22 | CYP1A2 | 14 | 72 | FGF1 | 5 |

| 23 | CYP19A1 | 14 | 73 | BCHE | 5 |

| 24 | ALOX5 | 14 | 74 | RARB | 4 |

| 25 | ABCB1 | 14 | 75 | HSD11B2 | 4 |

| 26 | PLA2G1B | 13 | 76 | GRK6 | 4 |

| 27 | TNFRSF1A | 12 | 77 | GPR35 | 4 |

| 28 | PLA2G4A | 12 | 78 | GPBAR1 | 4 |

| 29 | GABBR2 | 12 | 79 | DHCR7 | 4 |

| 30 | GABBR1 | 12 | 80 | PTGER2 | 3 |

| 31 | CNR2 | 12 | 81 | PPARD | 3 |

| 32 | PTGES | 11 | 82 | PDE4B | 3 |

| 33 | PTGER4 | 11 | 83 | IL6ST | 3 |

| 34 | NOS2 | 11 | 84 | HEXB | 3 |

| 35 | MTNR1B | 11 | 85 | CES2 | 3 |

| 36 | LTB4R | 11 | 86 | AKR1B10 | 3 |

| 37 | GLI1 | 11 | 87 | TTR | 2 |

| 38 | EDNRB | 11 | 88 | RORA | 2 |

| 39 | TLR9 | 10 | 89 | KCNA3 | 2 |

| 40 | S1PR3 | 10 | 90 | FABP3 | 2 |

| 41 | MMP1 | 10 | 91 | CTRB1 | 2 |

| 42 | HDAC3 | 10 | 92 | CPA1 | 2 |

| 43 | G6PD | 10 | 93 | CA2 | 2 |

| 44 | CYP17A1 | 10 | 94 | ASAH1 | 2 |

| 45 | ALOX12 | 10 | 95 | ACP1 | 2 |

| 46 | ALDH1A1 | 10 | 96 | PDE4D | 1 |

| 47 | VDR | 9 | 97 | PAM | 1 |

| 48 | TRPV1 | 9 | 98 | HEXA | 1 |

| 49 | SLC6A4 | 9 | 99 | GSTK1 | 1 |

| 50 | SHH | 9 |

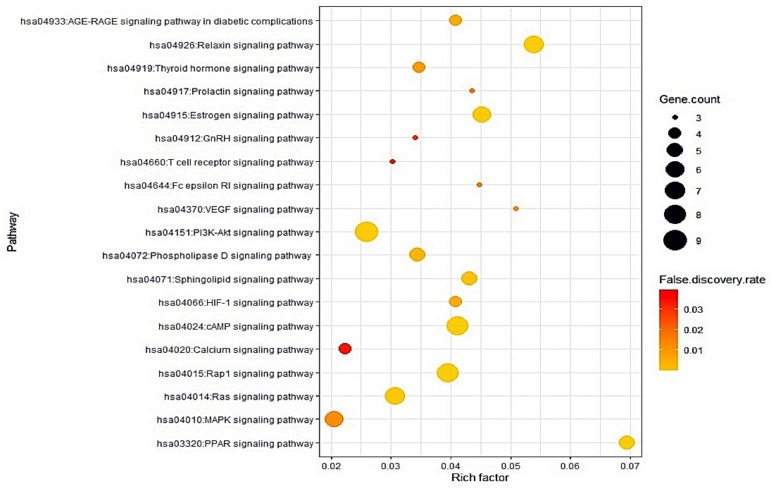

3.5. Identification of Two Key Signaling Pathways from a Bubble Chart

The results of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis unveiled that 19 signaling pathways were connected with 40 out of 101 targets (false discovery rate <0.05). The 19 signaling pathways were directly related to RA, indicating that these 19 signaling pathways might be significant pathways of ZPFs against RA. The description of 19 signaling pathways were shown in Table 4. Additionally, a bubble chart indicated that inactivation of MAPK signaling pathway and activation of PPAR signaling pathway might be key signaling pathways of ZPFs to alleviate RA (Figure 5). Specifically, MAPK signaling pathway is associated with VEGFA (a hub target) in holistic PPI networks while PPAR signaling pathway is not related to VEGFA.

Table 4.

Targets in 19 signaling pathways associated with RA.

| KEGG ID & Description | Target Genes | False Discovery Rate |

|---|---|---|

| hsa04933:AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications | PRKCA,MMP2,VEGFA,F3 | 0.01010 |

| hsa04926:Relaxin signaling pathway | PRKCA,VEGFA,EDNRB,MMP1,MMP2,MMP9, NOS2 | 0.00018 |

| hsa04919:Thyroid hormone signaling pathway | PRKCA,ESR1,HDAC1,HDAC3 | 0.01460 |

| hsa04917:Prolactin signaling pathway | ESR1,ESR2,CYP17A1 | 0.02200 |

| hsa04915:Estrogen signaling pathway | GABBR1,GABBR2,MMP2,MMP9,ESR1,ESR2 | 0.00110 |

| hsa04912:GnRH signaling pathway | PRKCA,MMP2,PLA2G4A | 0.03510 |

| hsa04660:T cell receptor signaling pathway | IL2,PTPRC,PTPN6 | 0.03950 |

| hsa04644:Fc epsilon RI signaling pathway | PRKCA,ALOX5,PLA2G4A | 0.02070 |

| hsa04370:VEGF signaling pathway | VEGFA,PRKCA,PLA2G4A | 0.01690 |

| hsa04151:PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | PRKCA,VEGFA,IL2,TLR4,FGF1,FGF2,LPAR1,LPAR2,LPAR3 | 0.00110 |

| hsa04072:Phospholipase D signaling pathway | PRKCA,MMP2,LPAR1,LPAR2,LPAR3 | 0.00660 |

| hsa04071:Sphingolipid signaling pathway | PRKCA,S1PR1,S1PR3,ASAH1,TNFRSF1A | 0.00340 |

| hsa04066:HIF-1 signaling pathway | PRKCA,VEGFA,TLR4,NOS2 | 0.01010 |

| hsa04024:cAMP signaling pathway | PPARA,EDNRA,PDE4B,PDE4D,GABBR1,GABBR2,PTGER2,GLI1 | 0.00023 |

| hsa04020:Calcium signaling pathway | PRKCA,NOS2,EDNRB,EDNRA | 0.03850 |

| hsa04015:Rap1 signaling pathway | PRKCA,VEGFA,FGF1,FGF2,CNR1,LPAR1,LPAR2,LPAR3 | 0.00025 |

| hsa04014:Ras signaling pathway | PRKCA,VEGFA,FGF1,FGF2,PLA2G2A,PLA2G1B | 0.00200 |

| hsa04010:MAPK signaling pathway | PRKCA,VEGFA,FGF1,FGF2,TNFRSF1A,PLA2G4A | 0.01810 |

| hsa03320:PPAR signaling pathway | PPARA,PPARD,PPARG,FABP3,MMP1 | 0.00070 |

Figure 5.

Bubble chart of 19 signaling pathways associated with cancer.

3.6. Construction of Signaling Pathway-Target-Compound Network

The signaling pathway–target–compound (STC) network is displayed in Figure 6. There were 19 pathways, 40 targets, and 63 compounds (122 nodes, 488 edges). The nodes stood for the total number of relationships between signaling pathways, targets, and compounds. The edges represented the relationship of three elements (19 pathways, 40 targets, and 63 compounds). The STC network suggested that the uppermost target is Protein Kinase C Alpha (PRKCA) with 14 degrees among 19 signaling pathways (Table 5).

Figure 6.

STC networks (122 nodes, 488 edges). Green rectangle: signaling pathway; gold triangle: targets; red circle: compounds.

Table 5.

The degree value of target in STC.

| No. | Target | Degree of Value | No. | Target | Degree of Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PRKCA | 14 | 21 | TLR4 | 2 |

| 2 | VEGFA | 8 | 22 | IL2 | 2 |

| 3 | MMP2 | 5 | 23 | PPARD | 1 |

| 4 | PLA2G4A | 4 | 24 | PPARG | 1 |

| 5 | FGF2 | 4 | 25 | FABP3 | 1 |

| 6 | FGF1 | 4 | 26 | ALOX5 | 1 |

| 7 | NOS2 | 3 | 27 | CYP17A1 | 1 |

| 8 | ESR1 | 3 | 28 | S1PR1 | 1 |

| 9 | LPAR1 | 3 | 29 | S1PR3 | 1 |

| 10 | LPAR2 | 3 | 30 | ASAH1 | 1 |

| 11 | LPAR3 | 3 | 31 | GLI1 | 1 |

| 12 | PPARA | 2 | 32 | PTGER2 | 1 |

| 13 | MMP1 | 2 | 33 | F3 | 1 |

| 14 | EDNRB | 2 | 34 | CNR1 | 1 |

| 15 | MMP9 | 2 | 35 | HDAC1 | 1 |

| 16 | GABBR2 | 2 | 36 | HDAC3 | 1 |

| 17 | GABBR1 | 2 | 37 | PLA2G2A | 1 |

| 18 | ESR2 | 2 | 38 | PLA2G1B | 1 |

| 19 | TNFRSF1A | 2 | 39 | PTPRC | 1 |

| 20 | EDNRA | 2 | 40 | PTPN6 | 1 |

3.7. KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis

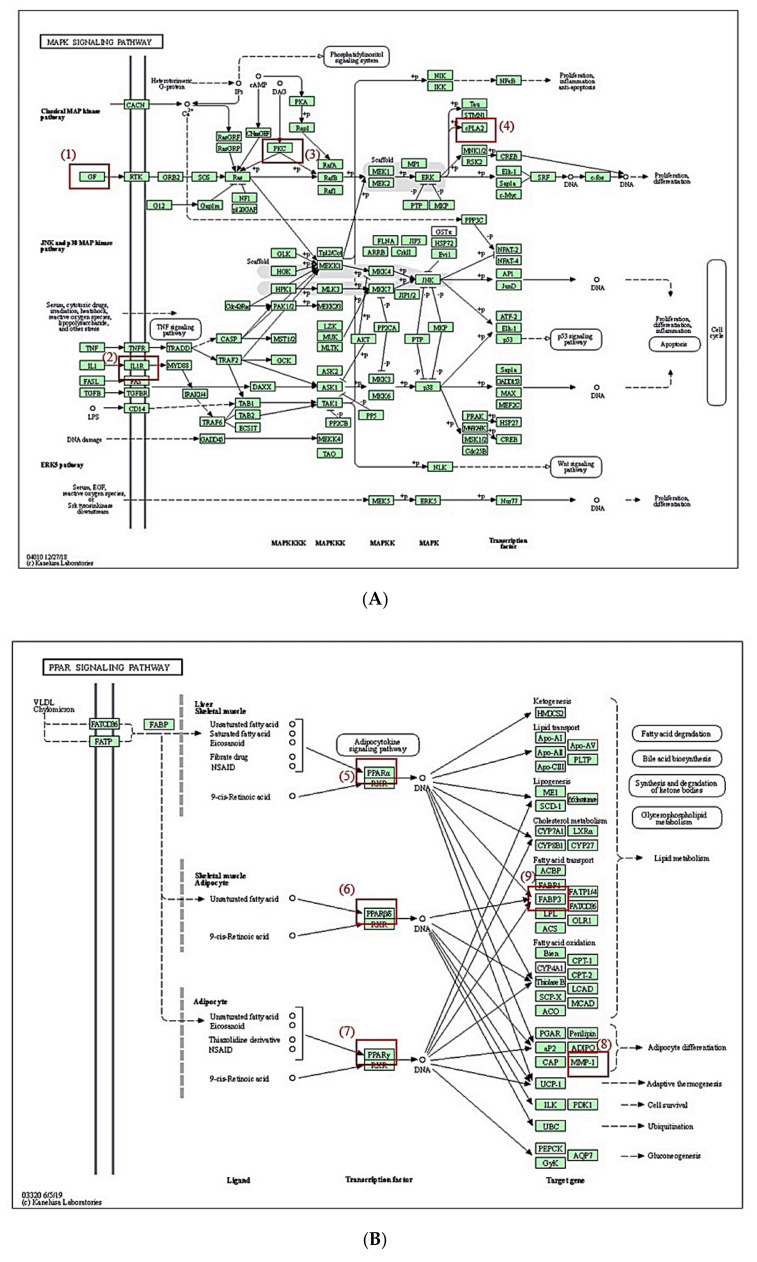

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis [25] reveals that 19 signaling pathways are associated with the occurrence and development of RA. Out of 19 signaling pathways, MAPK signaling pathway and PPAR signaling pathway were most significantly related to RA (Figure 7). The red rectangles indicated core targets on the two signaling pathways. One of the MAPK signaling pathways, PRKCA (a species of PKC), is an excellent immunomodulatory target, which is linked to the onset of inflammatory arthritis, including RA [26]. It was subsequently shown that inactivation of PRKCA results in the inhibition of c-fos; eventually, the cascade leads to the amelioration of RA in an animal model [27]. One of the PPAR signaling pathways, FABP3, is located in the upstream region to regulate lipid metabolism. It was reported that defective lipid metabolism was observed in RA patients who are persistent to proinflammatory responses [28].

Figure 7.

KEGG pathway enrichment map. (A) MAPK signaling pathway. (B) PPAR signaling pathway. Red rectangles represent key targets: (1) FGF1, FGF2, VEGFA; (2) TNFRSF1A; (3) PRKCA; (4) PLA2G4A; (5) PPARA; (6) PPARD; (7) PPARG; (8) MMP1; (9) FABP3.

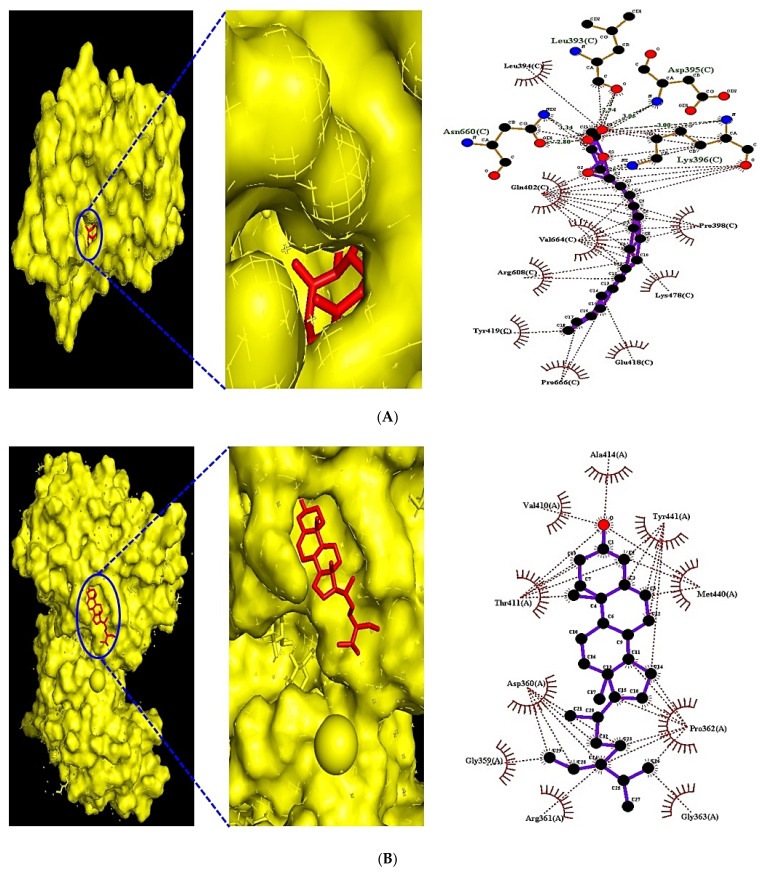

3.8. MDT of 6 Targets and 23 Chemical Compounds Associated with MAPK Signaling Pathway

From both SEA and STP databases, it was uncovered that FGF1 is associated with two chemical compounds, FGF2 with four chemical compounds, VEGFA with five chemical compounds, TNFRSF1A with two chemical compounds, PRKCA with 16 chemical compounds, and PLA2G4A with four chemical compounds. Out of 33 chemical compounds, 10 chemical compounds overlapped, and finally, 23 chemical compounds were identified on the MAPK signaling pathway.

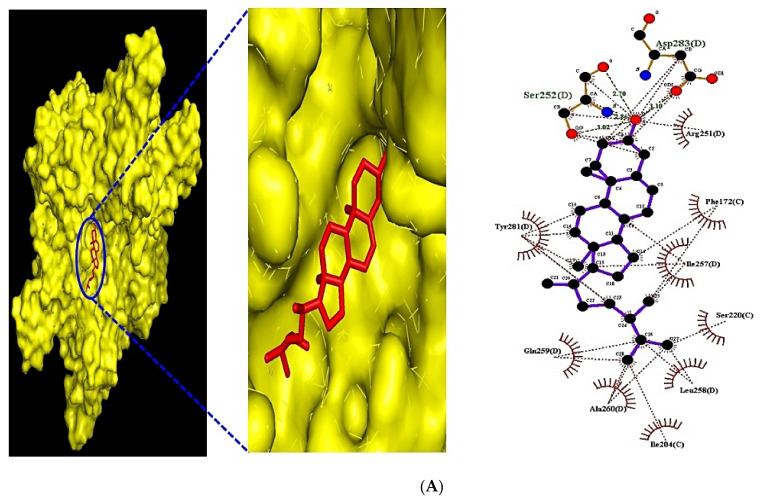

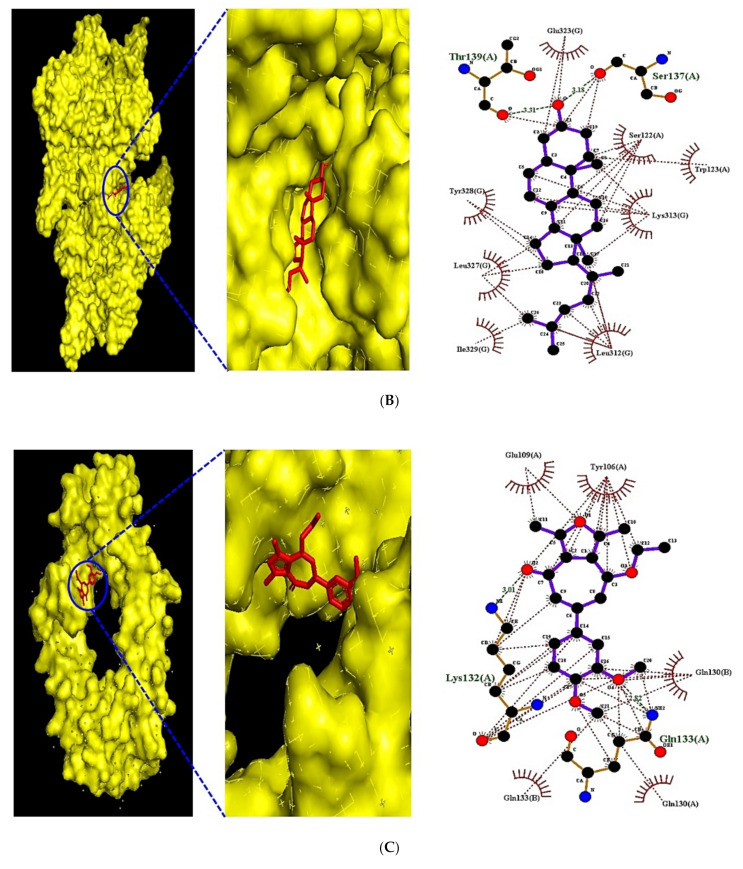

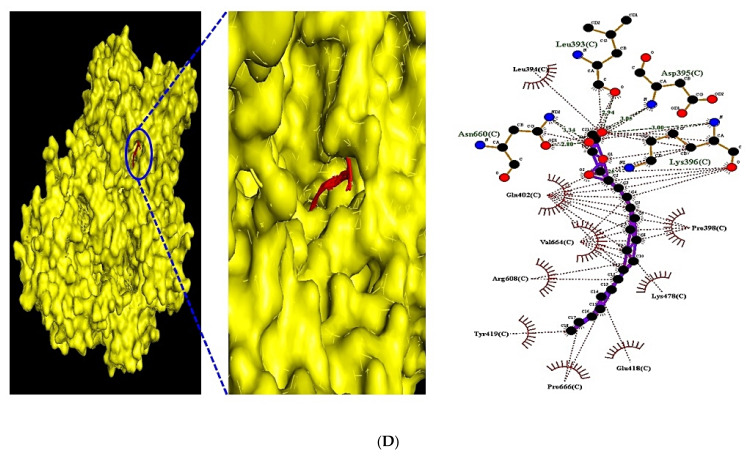

The MDT performed to evaluate affinity between target and ligand displayed the greatest affinity complex, depicted in Figure 8. In detail, campesterol (−8.4 kcal/mol) docked on the FGF1 target (PDB ID: 3OJ2) had the greatest affinity; however, it had a lower affinity than suramin sodium (−19.1 kcal) as a positive control. The 26,27-Dinorergosta-5,23-dien-3β-ol (−8.0 kcal/mol) docked on FGF2 target (PDB ID: 1IIL) had the highest affinity; its affinity was lower than NSC172285 (−14.7 kcal/mol) as a positive control. The 3,4-O-Isopropylidene-d-galactose (−5.3 kcal/mol) docked on VEGFA (PDB ID: 3V2A) had the highest affinity; however, the affinity score was invalid (> −6.0 kcal/mol) [29]. The CBMicro_013618 docked on TNFRSF1A (PDB ID: INCF) had the greatest affinity. Moreover, its score was better than Enamin_004209 (−5.3 kcal/mol) as a positive control. The berberine (−6.6 kcal/mol) as a positive control had a higher affinity than the stearic acid (−4.5 kcal/mol) docked on PLA2G4A (PDB ID: 1BCI). The monoolein (−6.7 kcal/mol) had the greatest affinity on PRKCA (PDB ID: 3IW4). Furthermore, its affinity score was greater than sphingosine (−5.5 kcal/mol) as a positive control. The detailed docking information is listed in Table 6.

Figure 8.

(A) MDT of campesterol (PubChem ID: 173183) on FGF1 (PDB ID: 3OJ2). (B) MDT of 26,27-Dinorergosta-5,23-dien-3β-ol (PubChem ID: 22213488) on FGF2 (PDB ID: 1IIL). (C) MDT of CBMicro_013618 (PubChem ID: 1109374) on TNFRSF1A (PDB ID: 1NCF). (D) MDT of monoolein (PubChem ID: 5283468) on PRKCA (PDB ID: 1NCF).

Table 6.

Binding energy of ligands and positive controls on MAPK signaling pathway.

| Grid Box | Hydrogen Bond Interactions | Hydrophobic Interactions |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Ligand | PubChem ID | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) |

Center | Dimension | Amino Acid Residue | Amino Acid Residue |

| FGF1 (PDB ID:3OJ2) |

(★) Campesterol | 173183 | −8.4 | x 9.051 | x 40 | Asp283, Ser252 | Arg251,Phe172, Ile257 |

| y 22.527 | y 40 | Ser220, Leu258, Ile204 | |||||

| z −0.061 | z 40 | Ala260, Gln259, Tyr281 | |||||

| 3,4-O-Isopropylidene-d-galactose | 54504880 | −6.1 | x 9.051 | x 40 | Arg255, Thr174, Phe172 | Asn350, Asn173, Ala349 | |

| y 22.527 | y 40 | Asn107, Gln348 | |||||

| z −0.061 | z 40 | ||||||

| Positive control | (a) Suramin sodium | 8514 | −19.1 | x 9.051 | x 40 | Ser282, Lys27 | Arg203, Ile204, Ala260 |

| y 22.527 | y 40 | Gln259, Leu258, Tyr281 | |||||

| z −0.061 | z 40 | Asn22, Tyr23, Asp283 | |||||

| Val249, Pro149, Glu250 | |||||||

| His254, Ser252, Ile257 | |||||||

| Phe172, Val222, Ser220 | |||||||

| FGF2 (PDB ID:1IIL) | (★) 26,27-Dinorergosta-5,23-dien-3β-ol | 22213488 | −8.0 | x 26.785 | x 40 | Thr139, Ser137 | Glu323, Ser122, Trp123 |

| y 14.360 | y 40 | Lys313, Leu312, Ile329 | |||||

| z −1.182 | z 40 | Leu327, Tyr328 | |||||

| Campesterol | 173183 | −7.9 | x 26.785 | x 40 | Ser137 | Thr139, Glu323, Lys313 | |

| y 14.360 | y 40 | Asp336, Tyr328, Ile329 | |||||

| z −1.182 | z 40 | Leu312, Leu327, Ser122 | |||||

| Trp123, Thr319 | |||||||

| Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol | 53870683 | −7.8 | x 26.785 | x 40 | Tyr340, Asp336 | Ile329, Leu312, Ser122 | |

| y 14.360 | y 40 | Trp123, Ser137, Thr319 | |||||

| z −1.182 | z 40 | Glu323, Asn318, Lys313 | |||||

| Leu327 | |||||||

| 3,4-O-Isopropylidene-d-galactose | 54504880 | −5.6 | x 26.785 | x 40 | Glu323, Trp123, Ser137 | Ser122 | |

| y 14.360 | y 40 | Thr139, Lys313 | |||||

| z −1.182 | z 40 | ||||||

| Positive control | (b) NSC172285 | 299405 | −14.7 | x 26.785 | x 40 | Tyr207 | Val209, Asp99, Lys119 |

| y 14.360 | y 40 | Lys199, Gln200, Glu201 | |||||

| z −1.182 | z 40 | ||||||

| (b) NSC37204 | 235612 | −9.5 | x 26.785 | x 40 | Thr358, Arg210, Thr121 | Val209, Asn265, Lys119 | |

| y 14.360 | y 40 | Arg118, Glu201 | Asp99, Gln200, Trp356 | ||||

| z −1.182 | z 40 | ||||||

| VEGFA (PDB ID: 3V2A) | (★) 3,4-O-Isopropylidene-d-galactose | 54504880 | −5.3 | x 38.009 | x 40 | Gly312, Ser310 | Gly255, Glu44, Ser311 |

| y −10.962 | y 40 | Ile256, Asp257, Lys84 | |||||

| z 12.171 | z 40 | Pro85 | |||||

| Glyceryl palmitate | 14900 | −5.2 | x 38.009 | x 40 | Pro40, Asp276 | Arg275, Phe36, Lys286 | |

| y −10.962 | y 40 | Lys48, Asn253, Ile46 | |||||

| z 12.171 | z 40 | ||||||

| Monoolein | 5283468 | −5.1 | x 38.009 | x 40 | Asp276, Pro40 | Arg275, Asp34, Asn253 | |

| y −10.962 | y 40 | Lys48, Phe47, Ile46 | |||||

| z 12.171 | z 40 | Phe36, Lys286 | |||||

| Methyl palmitate | 8181 | −4.0 | x 38.009 | x 40 | n/a | Pro40, Arg275, Phe36 | |

| y −10.962 | y 40 | Ile46, Asn253, Lys286 | |||||

| z 12.171 | z 40 | Asp276 | |||||

| Isopropyl hexanoate | 16832 | −3.9 | x 38.009 | x 40 | n/a | Pro85, Ser310, Gly312 | |

| y −10.962 | y 40 | Glu44, Ser311, Gly255 | |||||

| z 12.171 | z 40 | Gln87, Lys84, Asp257 | |||||

| Positive control | (c) BAW2881 | 16004702 | −7.6 | x 38.009 | x 40 | n/a | Lys286, Asp34, Ser50 |

| y −10.962 | y 40 | Asp276, Pro40, Phe36 | |||||

| z 12.171 | z 40 | Ile46 | |||||

| TNFRSF1A (PDB ID: 1NCF) | (★) CBMicro_013618 | 1109374 | −6.8 | x 21.259 | x 40 | Lys132, Gln133 | Glu109, Tyr106, Gln130 |

| y 14.648 | y 40 | Gln133 | |||||

| z 34.77 | z 40 | ||||||

| 2-Propenoic acid, 3-phenyl-, methyl ester | 7644 | −5.0 | x 21.259 | x 40 | Lys35 | Ala62, Glu64, His34 | |

| y 14.648 | y 40 | Lys35, Glu64 | |||||

| z 34.77 | z 40 | ||||||

| Positive control | (d) Enamine_004209 | 2340496 | −5.3 | x 21.259 | x 40 | Glu109, Cys96, Tyr106 | Asn110, Ph112, Val95 |

| y 14.648 | y 40 | Gln82, Ser74, Thr94 | |||||

| z 34.77 | z 40 | Arg77, Arg132 | |||||

| PLA2G4A (PDB ID: 1BCI) | (★) Stearic acid | 5281 | −4.5 | x −0.058 | x 40 | Gly33, Lys32 | Pro42, Val30, Ile67 |

| y 0.077 | y 40 | Val127, Thr31, Gln126 | |||||

| z 0.285 | z 40 | ||||||

| Methyl palmitate | 8181 | −3.9 | x −0.058 | x 40 | Lys58 | Phe77, Pro54, Thr53 | |

| y 0.077 | y 40 | Leu79, Tyr16, Glu76 | |||||

| z 0.285 | z 40 | Ile78 | |||||

| Palmitic acid | 985 | −3.8 | x −0.058 | x 40 | Thr53 | Leu79, Phe77, Ile78 | |

| y 0.077 | y 40 | Tyr16, Glu76, Pro54 | |||||

| z 0.285 | z 40 | ||||||

| Myristic acid | 11005 | −3.3 | x −0.058 | x 40 | n/a | Asp55, Pro54, Tyr16 | |

| y 0.077 | y 40 | Phe77, Ile78, Thr53 | |||||

| z 0.285 | z 40 | ||||||

| Positive control | (e) Berberine | 2353 | −6.6 | x −0.058 | x 40 | n/a | Arg59, Asp99, Asn95 |

| y 0.077 | y 40 | His62, Phe63, Asn64 | |||||

| z 0.285 | z 40 | Arg61, Ala94, Tyr45 | |||||

| PRKCA (PDB ID: 3IW4) | (★) Monoolein | 5283468 | −6.7 | x −14.059 | x 40 | Asn660, Leu393, Asp395 | Pro398, Lys478, Glu418 |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Lys396 | Pro666, Tyr419, Arg608 | ||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | Val664, Gln402 | |||||

| Glyceryl palmitate | 14900 | −6.6 | x −14.059 | x 40 | Asp395, Lys396, Leu393 | Leu394, Gln402, Lys478 | |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Asn660 | Arg608, Pro666, Ile667 | ||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | Val664, Pro398, Pro397 | |||||

| Stearic acid | 5281 | −6.3 | x −14.059 | x 40 | Lys396, Leu393 | Pro397, Pro398, Lys478 | |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Arg608, Ile667, Pro666 | |||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | His665, Val664, Gln402 | |||||

| Asn660, Leu394 | |||||||

| Nonadecanoic acid | 12591 | −6.2 | x −14.059 | x 40 | Leu393, Lys396 | Asn660, Pro397, Pro398 | |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Lys478, Pro666, Arg608 | |||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | Glu418, Val664, Gln402 | |||||

| Leu394 | |||||||

| 1,6,10-Dodecatrien-3-ol, 3,7,11-trimethyl- | 8888 | −6.2 | x −14.059 | x 40 | Lys372, Gln408, Gln650 | Val410, Thr409, Gly540 | |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Ile645, Asp539, Asp503 | |||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | Phe538, Glu543 | |||||

| 2,5-Furandione, 3-dodecenyl- | 5362708 | −6.1 | x −14.059 | x 40 | Lys396, Asp395 | Asn660, Gln402, Pro397 | |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Pro398, Glu552, Gln662 | |||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | Val664, Leu394 | |||||

| 2,6-Dimethyl-3,5,7-octatriene-2-ol, Z,Z- | 5363692 | −5.3 | x −14.059 | x 40 | Gly540 | Val410, Ile645, Asp503 | |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Pro502, Glu543, Gln650 | |||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | Leu546, Asp542 | |||||

| 2-Dodecenoic acid | 5282729 | −5.1 | x −14.059 | x 40 | Lys396, Asn660, Leu393 | Leu394, Gln662, Glu552 | |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Val664, Gln402 | |||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | ||||||

| 9-Octadecenoic acid | 965 | −5.0 | x −14.059 | x 40 | Leu393, Lys396 | Asn660, Glu552, Gln548 | |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | His553, Ser549, Gln662 | |||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | Val664, Gln402, Leu394 | |||||

| Octanoic acid | 379 | −5.0 | x −14.059 | x 40 | Asn660, Lys396, Gln402 | Pro397, Lys478, Pro398 | |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Val664, Glu552, Arg608 | |||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | ||||||

| Methyl palmitate | 8181 | −5.0 | x −14.059 | x 40 | n/a | Gln377, Asn647, Asp373 | |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Ile648, Asp649, Asn468 | |||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | Lys465, Phe350, Asp467 | |||||

| Ile376 | |||||||

| Palmitic acid | 985 | −5.0 | x −14.059 | x 40 | Leu393, Asp395, Lys396 | Pro397, Pro398, Val664 | |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Glu552, His553, Ser549 | |||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | Gln548,Gln662, Gln402 | |||||

| Leu394, Asn660 | |||||||

| (E)-4-Undecenal | 5283357 | −4.8 | x −14.059 | x 40 | n/a | Gln642, Pro536, Ile645 | |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Gly540, Val410, Gln650 | |||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | Glu543, Asp542, Asp503 | |||||

| Leu546 | |||||||

| Myristic acid | 11005 | −4.8 | x −14.059 | x 40 | Lys396, Gln402 | Asp395, Leu393, Leu394 | |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Pro398, Val664, Gln662 | |||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | Asn660 | |||||

| Nonanoic acid | 8158 | −4.7 | x −14.059 | x 40 | Leu393, Lys396 | Leu394, Asn660, Pro397 | |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Gln402, Gln662, Val664 | |||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | ||||||

| Heptadec-8-ene | 520230 | −4.6 | x −14.059 | x 40 | n/a | Asn647, Asp424, Met426 | |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Gln377,Ile376, Phe350 | |||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | Asp467, Asp373 | |||||

| Positive control | (f) Sphingosine | 5280335 | −5.5 | x −14.059 | x 40 | Asn660, Gln662, Lys396 | Pro397, Gln402, Val664 |

| y 38.224 | y 40 | Gln548, Glu552, His553 | |||||

| z 32.319 | z 40 | Leu394, Ser549, Asp395 | |||||

(★) Compound with the greatest affinity on each target; (a) FGF1 antagonist; (b) FGF2 antagonist; (c) VEGFA antagonist; (d) TNFRSF1A antagonist; (e) PLA2G4A antagonist; (f) PRKCA antagonist.

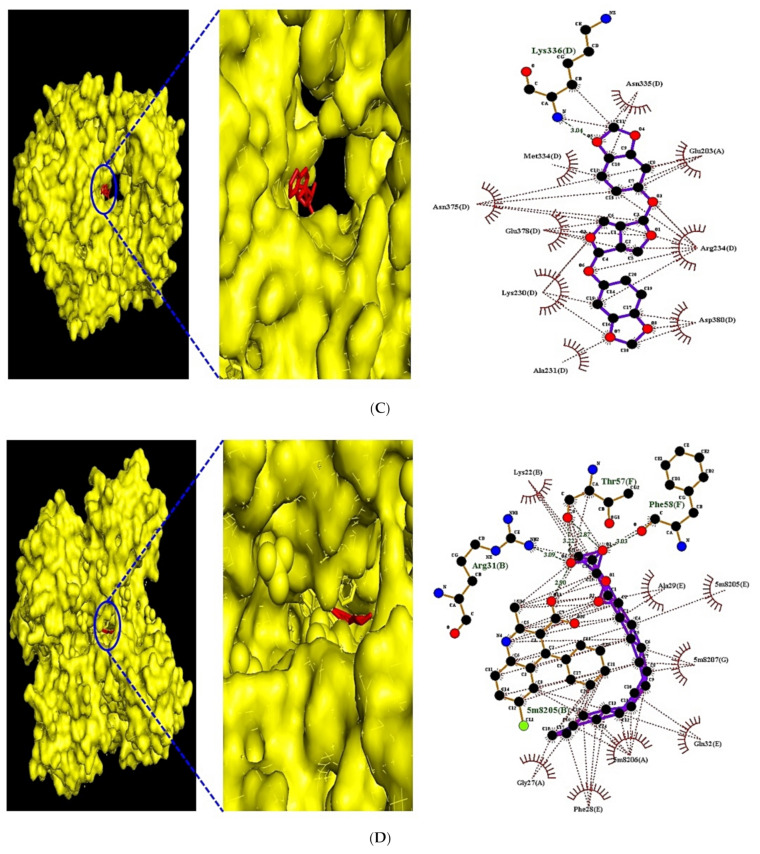

3.9. MDT of 5 Targets and 43 Chemical Compounds Associated with PPAR Signaling Pathway

From both SEA and STP databases, it was revealed that Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha (PPARA) is related to 32 chemical compounds, Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Delta (PPARD) to 18 chemical compounds, Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma (PPARG) to 17 chemical compounds, FABP3 to 26 chemical compounds, and MMP to five chemical compounds. The MDT performed to obtain affinity between targets and ligands exhibited the highest affinity complex, as displayed in Figure 9. Noticeably, β-Caryophyllene (−8.6 kcal/mol) docked on PPARA (PDB ID: 3SP6) had the greatest affinity, which had a higher score than Clofibrate (−6.4 kcal/mol), Gemfibrozil (−6.3 kcal/mol), Ciprofibrate (−5.4 kcal/mol), Bezafibrate (−5.8 kcal/mol), and Fenofibrate (−5.4 kcal/mol) as five positive controls. Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol (−8.6 kcal/mol) docked on PPARD (PDB ID: 5U3Q) had the greatest affinity, which had a better score than Cardarine (−8.5 kcal/mol) as a positive control. NSC402953 (−8.2 kcal/mol) docked on PPARG (PDB ID: 3E00) had the highest affinity, which had better than Pioglitazone (−7.7 kcal/mol), Rosiglitazone (−7.4 kcal/mol), and Lobeglitazone (−7.3 kcal/mol) as three positive controls. Monoolein (−8.9 kcal/mol) docked on FABP3 (PDB ID: 5HZ9) had the greatest affinity; specifically, there was no positive control on FABP3 (PDB ID: 5HZ9). 2-Propenoic acid, 3-phenyl-, methyl ester (−5.0 kcal/mol) docked on MMP1 (PDB ID: 1SU3) had the highest affinity, which had lower affinity than Batimastat (−6.7 kcal/mol), and Ilomastat (−6.5 kcal/mol) as two positive controls. The detailed docking information is listed in Table 7.

Figure 9.

(A) MDT of β-Caryophyllene (PubChem ID: 5281515) on PPARA (PDB ID: 3SP6). (B) MDT of Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol (PubChem ID: 53870683) on PPARD (PDB ID: 5U3Q). (C) MDT of NSC402953 (PubChem ID:345349) on PPARG (PDB ID: 3E00). (D) MDT of monoolein (PubChem ID: 5283468) on FABP3 (PDB ID: 5HZ9).

Table 7.

Binding energy of ligands and positive controls on PPAR signaling pathway.

| Grid Box | Hydrogen Bond Interactions |

Hydrophobic Interactions |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Ligand | PubChem ID | Binding Energy(kcal/mol) | Center | Dimension | Amino Acid Residue | Amino Acid Residue |

| PPARA (PDB ID: 3SP6) | (★) β-Caryophyllene | 5281515 | −8.6 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Leu321, Leu331, Gly335 |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Val324, Met220, Tyr334 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Ala333, Thr279, Asn219 | |||||

| Thr283 | |||||||

| Cadina-1(10),4-diene | 10223 | −7.4 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Met220, Leu331, Val324 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Thr279, Thr283, Leu321 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Ile317, Met320 | |||||

| 26,27-Dinorergosta-5,23-dien-3beta-ol | 22213488 | −7.0 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Lys345 | Glu356, Asp353, Pro357 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Leu443, His440, Glu439 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Leu436, Lys358, Asp360 | |||||

| Clionasterol | 457801 | −6.7 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Lys345 | Asp360, Pro357, Glu439 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | His440, Leu443, Asp353 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Glu356 | |||||

| Cyclohexene, 4-(4-ethylcyclohexyl)-1-pentyl- | 543386 | −6.6 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Met320, Phe218, Met220 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Thr279, Val332, Ala333 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Tyr334, Thr283, Asn219 | |||||

| Spiro[4.4]nona-1,3-diene, 1,2-dimethyl- | 570800 | −6.5 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Leu321, Leu331, Val324 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Met320, Asn219, Thr283 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Thr279, Met220 | |||||

| 1-Methyldecahydronaphthalene | 34193 | −6.4 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Met320, Val324, Met220 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Asn219, Thr279, Thr283 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Leu321 | |||||

| 1,3,4,5-Tetrahydroxycyclohexanecarboxylic acid | 1064 | −6.3 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Ile317, Glu286, Asn219 | Met320, Met220, Leu321 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Thr283 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol | 53870683 | −6.3 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Arg465, Glu462, Ser688 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Val306, Asn303, Thr307 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Tyr311, Gly390, Pro389 | |||||

| Lys310, Asp466 | |||||||

| Terpinolene | 11463 | −6.2 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Thr279, Tyr334, Val324 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Met220, Met320, Leu321 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Thr283, Asn219 | |||||

| β-Phellandrene | 11142 | −6.0 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Leu331, Val324, Leu321 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Ile317, Thr283, Met320 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Thr279 | |||||

| Citronellic acid | 10402 | −5.9 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Thr283, Glu286, Met220 | Met320, Asn219, Tyr334 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Gly335, Leu321, Val324 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Ile317 | |||||

| Stearic acid | 5281 | −5.7 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Phe361, Asp432, Leu436 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Glu439, His440, Leu443 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Asp353, Gln442, Ile446 | |||||

| Pro357, Lys358 | |||||||

| Monoolein | 5283468 | −5.7 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Asn261, Lys257 | Leu258, His274, Cys275 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Ala333, Val255, Cys278 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| 2,6-Octadiene, 2,6-dimethyl- | 5365898 | −5.7 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Met320, Phe218, Leu331 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Val324, Met220, Leu321 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| Citronellol | 8842 | −5.5 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Thr283 | Leu331, Val324, Ile317 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Leu321, Met320, Thr279 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| Myrcene | 31253 | −5.5 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Val332, Val324, Ile317 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Leu321, Met220, Thr283 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Met320, Leu331 | |||||

| (E)-β-Ocimene | 5281553 | −5.5 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Thr283, Ile317, Met320 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Tyr334, Val332, Val324 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Gly335, Leu331, Thr279 | |||||

| Leu321 | |||||||

| Citronellal | 7794 | −5.2 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Thr283 | Leu321, Met220, Met320 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Val324, Asn219, Thr279 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Ile317 | |||||

| Heptadec-8-ene | 520230 | −5.2 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Leu321, Ile317, Thr283 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Thr279, Val255, Ala333 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Tyr334, Leu331, Val332 | |||||

| Val324 | |||||||

| Myristic acid | 11005 | −5.2 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Tyr334, Ala333,Thr279 | Val332, Met220, Met320 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Ile317, Leu321, Thr283 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Asn219 | |||||

| Nonanoic acid | 8158 | −5.1 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Ala333 | Leu331, Leu321, Val332 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Ile317, Thr283, Met320 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Val324, Thr279 | |||||

| 10-Bromoundecanoic acid | 543401 | −5.1 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Met320, Val324, Leu321 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Thr279, Leu331, Val332 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Asn219, Tyr334, Met220 | |||||

| 2-Methyl-Z,Z-3,13-octadecadienol | 5364412 | −5.0 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Leu254, Ala333, Cys275 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Tyr334, Ile317, Met320 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Thr283, Leu321, Leu331 | |||||

| Val324, Ala250, Thr279 | |||||||

| Ile241, Val255 | |||||||

| Octanoic acid | 379 | −5.0 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Asn219, Thr283, Met220 | Phe218, Leu321, Val324 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Glu286 | Leu331, Met320 | ||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| Nonadecanoic acid | 12591 | −4.9 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Asn336, Leu254, Ala333 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Ala250, Cys275, Val255 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Tyr334 | |||||

| 3-Hydroxycyclohexanone | 439950 | −4.9 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Met220 | Met320, Phe218, Asn219 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Glu286 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| Palmitic acid | 985 | −4.9 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Glu251, Val332, Ile241 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Ala333, Thr279, Val255 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Tyr334, Leu258, Cys275 | |||||

| Ala250, Leu254 | |||||||

| 3-Methylcyclohexene | 11573 | −4.6 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Met320, Ile317, Leu321 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Thr279, Thr283 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| 9-Octadecenoic acid | 965 | −4.4 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Glu251, Ala250, Leu254 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Val255, Ile241, Ala333 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Asn336, Tyr334, Cys275 | |||||

| 2-Tetradecynoic acid | 324386 | −4.1 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Thr307 | Glu462, Ser688, Gln691 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Tyr311, Lys310, Asn303 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Val306 | |||||

| Methyl palmitate | 8181 | −3.7 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Tyr311, Gln691, Pro389 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Lys310, Thr307, Asn303 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Val306, Ser688, Glu462 | |||||

| Positive control | (a) Clofibrate | 2796 | −6.4 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Thr283 | Ala333, Tyr334, Asn219 |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Met320, Leu321, Met220 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Phe218, Val332, Val324 | |||||

| Thr279 | |||||||

| (a) Gemfibrozil | 3463 | −6.3 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Tyr468 | Tyr464, Lys448, Leu456 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Arg465, Gln442, Ala441 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| (a) Ciprofibrate | 2763 | −5.4 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Ala333, Thr279 | Lys257, Cys278, Tyr334 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Cys275, Val255, Leu258 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| (a) Bezafibrate | 39042 | −5.8 | x 8.006 | x 40 | Thr307, Ser688 | Asn303, Glu462, Val306 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Leu690, Lys310, Gly390 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| (a) Fenofibrate | 3339 | −5.4 | x 8.006 | x 40 | n/a | Gln435, Ala431, Asp360 | |

| y −0.459 | y 40 | Pro357, Leu436, Glu439 | |||||

| z 23.392 | z 40 | Lys364, Phe361, Asp432 | |||||

| PPARD (PDB ID:5U3Q) | (★) Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol | 53870683 | −8.6 | x 39.265 | x 40 | n/a | Ala414, Tyr441, Met440 |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Pro362, Gly363, Arg361 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | Gly359, Asp360, Thr411 | |||||

| Val410 | |||||||

| Clionasterol | 457801 | −7.3 | x 39.265 | x 40 | Met440 | Ala414, Tyr441, Tyr284 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Pro362, Arg361, Asp360 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | Val410, Thr411 | |||||

| 26,27-Dinorergosta-5,23-dien-3beta-ol | 22213488 | −7.3 | x 39.265 | x 40 | n/a | Lys188, Glu262, Lys265 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Ser266, Ser271 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| Stearic acid | 5281 | −6.8 | x 39.265 | x 40 | n/a | Glu288, Tyr284, Asp439 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Asp360, Val367, Gly359 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | Leu364, Gly363, Arg361 | |||||

| Pro362, Met440, Thr411 | |||||||

| Tyr441 | |||||||

| 1,3,4,5-Tetrahydroxycyclohexanecarboxylic acid | 1064 | −6.6 | x 39.265 | x 40 | Tyr441, Glu288 | Ala414, Thr411, Val410 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Tyr284, Arg361, Arg407 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | Met440 | |||||

| Nonadecanoic acid | 12591 | −5.8 | x 39.265 | x 40 | Asp360 | Pro362, Tyr441, Met440 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Val410, Glu288, Arg407 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | Thr411, Arg361, Tyr284 | |||||

| Citronellal | 7794 | −5.7 | x 39.265 | x 40 | n/a | Asn307, Ala306, Thr252 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Trp228, Arg248, Val305 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | Gln230, Lys229 | |||||

| Nonanoic acid | 8158 | −5.7 | x 39.265 | x 40 | Thr256 | Glu255, Asn307, Lys229 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Trp228, Ala306, Thr252 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | Glu259, Asn191 | |||||

| Citronellic acid | 10402 | −5.3 | x 39.265 | x 40 | n/a | Arg361, Tyr441, Thr411 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Met440, Tyr284 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| Myristic acid | 11005 | −5.2 | x 39.265 | x 40 | Tyr441 | Ala414, Glu288, Pro362 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Arg361, Asp439, Tyr284 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | Arg407, Thr411, Met440 | |||||

| Val410 | |||||||

| Octanoic acid | 379 | −5.1 | x 39.265 | x 40 | Lys229, Gln230, Arg248 | Cys251, Trp228, Val305 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Ala306, Thr252 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| 9-Octadecenoic acid | 965 | −5.0 | x 39.265 | x 40 | n/a | Met440, Thr411, Tyr441 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Pro362, Tyr284, Arg361 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | Val410 | |||||

| 3-Hydroxycyclohexanone | 439950 | −5.0 | x 39.265 | x 40 | Arg407, Thr411 | Val410, Met440, Tyr441 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | ||||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| Citronellol | 8842 | −4.8 | x 39.265 | x 40 | Arg361 | Asp439, Met440, Tyr441 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Tyr284, Val410 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| Palmitic acid | 985 | −4.6 | x 39.265 | x 40 | n/a | Tyr441, Pro362, Arg361 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Val410, Tyr284, Glu288 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | Met440, Thr411, Ala414 | |||||

| Arg407 | |||||||

| 10-Bromoundecanoic acid | 543401 | −4.6 | x 39.265 | x 40 | Arg361, Tyr284 | Tyr441, Met440, Pro362 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Thr411, Glu288 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | ||||||

| Methyl palmitate | 8181 | −4.5 | x 39.265 | x 40 | n/a | Thr411, Tyr441, Pro362 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Met440, Arg361, Tyr284 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | Glu288 | |||||

| Positive control | |||||||

| (b) Cardarine | 9803963 | −8.5 | x 39.265 | x 40 | Ser271, Ser272 | Lys265, Glu262, Ser266 | |

| y −18.736 | y 40 | Lys265, Ser271, Pro268 | |||||

| z 119.392 | z 40 | Ser269 | |||||

| PPARG (PDB ID: 3E00) | (★) NSC402953 | 345349 | −8.2 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Lys336 | Asn335, Glu203, Arg234 |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Asp380, Ala231, Lys230 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Glu378, Asn375, Met334 | |||||

| 26,27-Dinorergosta-5,23-dien-3beta-ol | 22213488 | −8.0 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Asn375 | Val372, Asn335, Val205 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Val163, Glu207, Glu208 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | ||||||

| Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol | 53870683 | −7.8 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Asn375 | Arg202, Glu203, Lys336 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Val163, Arg164, Gln206 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Lys165, Glu208, Glu207 | |||||

| Val372, Asn335 | |||||||

| Clionasterol | 457801 | −7.7 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Asn375 | Asn335, Val372, Lys336 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Val163, Arg164, Glu208 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Asp166, Glu207, Arg202 | |||||

| Glu203 | |||||||

| Terpinyl propionate | 62328 | −6.6 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Glu343 | Leu340, Ile341, Leu333 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Leu228, Met329, Arg288 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | ||||||

| Nonadecanoic acid | 12591 | −5.9 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Glu351 | Lys354, Thr168, Tyr189 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Tyr169, Thr162, Leu167 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Tyr192, Arg202, Arg350 | |||||

| Asp337, Lys336, Gln193 | |||||||

| Stearic acid | 5281 | −5.9 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Ser342, Cys285 | Ile341, Phe226, Ile296 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Glu295, Ala292, Met329 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Leu333, Leu228, Arg288 | |||||

| Citronellic acid | 10402 | −5.2 | x 2.075 | x 40 | n/a | Glu295, Arg288, Ala292 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Leu228, Leu333, Met329 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | ||||||

| Palmitic acid | 985 | −5.1 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Glu291, Arg288 | Glu343, Leu333, Leu228 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Met229, Ala292, Ile326 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Glu295 | |||||

| Myristic acid | 11005 | −5.1 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Glu343 | Arg288, Ser342, Leu333 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Met329, Leu228, Glu295 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Pro227, Ala292 | |||||

| Nonanoic acid | 8158 | −5.0 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Lys354 | Arg350, Glu351, Tyr169 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Tyr192, Tyr189, Leu167 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Gln193, Asp337, Lys336 | |||||

| Citronellal | 7794 | −4.9 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Gln193 | Tyr189, Arg202, Leu167 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Thr162, Tyr192, Asp337 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Lys336, Arg350, Lys354 | |||||

| Glu351 | |||||||

| (E)-4-Undecenal | 5283357 | −4.9 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Tyr169 | Leu167, Tyr192, Lys336 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Arg350, Glu351, Asp337 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Gln193, Lys354, Tyr189 | |||||

| Octanoic acid | 379 | −4.7 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Arg202, Leu167 | Asp337, Thr168, Tyr192 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Tyr169, Gln193, Tyr189 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Glu351, Lys336 | |||||

| 9-Octadecenoic acid | 965 | −4.1 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Arg164, Glu208 | Glu207, Glu203, Asp166 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Lys336, Arg202, Val372 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Asn375, Val163 | |||||

| Methyl palmitate | 8181 | −3.8 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Glu291, Arg288 | Glu343, Leu333, Leu330 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Leu228, Met329, Ala292 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Ile326, Glu295 | |||||

| Positive control | (c) Pioglitazone | 4829 | −7.7 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Arg288 | Ile326, Leu333, Met329 |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Ala292, Ile341, Cys285 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Ser342, Glu343, Glu295 | |||||

| Leu228 | |||||||

| (c) Rosiglitazone | 77999 | −7.4 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Tyr169 | Glu351, Tyr189, Gln193 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Thr168, Leu167, Glu369 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Lys373, Val372, Arg350 | |||||

| Lys336, Tyr192, Asp337 | |||||||

| (c) Lobeglitazone | 9826451 | −7.3 | x 2.075 | x 40 | Arg234 | Val372, Asn375, Met334 | |

| y 31.910 | y 40 | Val163, Lys230, Glu203 | |||||

| z 18.503 | z 40 | Lys157, Val205, Arg164 | |||||

| Arg202, Asp166, Lys336 | |||||||

| FABP3 (PDB ID: 5HZ9) | (★) Monoolein | 5283468 | −8.9 | x −1.215 | x 40 | Arg31, Thr57, Phe58 | Ala29, Gln32, Phe28 |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Gly27 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| Glyceryl palmitate | 14900 | −8.7 | x −1.215 | x 40 | Arg31 | Thr57, Phe58, Ala29 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Gln32, Phe28, Lys22 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| Nonadecanoic acid | 12591 | −8.3 | x −1.215 | x 40 | Lys22 | Ala29, Gln32, Phe28 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Gly27, Gly25 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| Stearic acid | 5281 | −8.3 | x −1.215 | x 40 | n/a | Gly27, Asp78, Thr122 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Phe58, Ala29, Phe28 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | Lys22, Lys59, Asp77 | |||||

| Thr30 | |||||||

| 2-Dodecen-1-ylsuccinic anhydride | 5362708 | −7.8 | x −1.215 | x 40 | Thr30, Gly27 | Gly25, Gln32, Ala29 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Phe28 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| Heptadec-8-ene | 520230 | −7.6 | x −1.215 | x 40 | n/a | Phe28, Met36, Thr57 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Val33, Ala29, Gln32 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| 2-Methyl-Z,Z-3,13-octadecadienol | 5364412 | −7.4 | x −1.215 | x 40 | n/a | Lys22, Gly25, Gly27 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Gln32, Phe28, Ala29 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| 2-Tetradecynoic acid | 324386 | −7.4 | x −1.215 | x 40 | Arg31, Lys22 | Phe58, Ala29, Gln32 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Phe28, Thr57, Lys59 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| Methyl palmitate | 8181 | −7.1 | x −1.215 | x 40 | n/a | Phe28, Gly27, Gly25 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Gln32, Ala29 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| 9-Octadecenoic acid | 637517 | −7.1 | x −1.215 | x 40 | n/a | Ala29, Gly25, Phe28 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Gly27, Gly25, Gln32 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| Myristic acid | 11005 | −6.9 | x −1.215 | x 40 | Phe58 | Ala29, Phe28, Gly27 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Lys22 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| 2-Dodecenoic acid | 5282729 | −6.8 | x −1.215 | x 40 | Arg31 | Lys59, Phe58, Thr57 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Ala29, Gln32, Phe28 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | Lys22 | |||||

| Citronellic acid | 10402 | −6.6 | x −1.215 | x 40 | Phe58 | Lys22, Met36, Ala29 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Thr57 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| Palmitic acid | 985 | −6.5 | x −1.215 | x 40 | n/a | Val33, Thr57, Lys22 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Phe58, Ala29, Gln32 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| (E)-4-Undecenal | 5283357 | −6.5 | x −1.215 | x 40 | n/a | Gln32, Ala29, Gly25 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Gly27, Phe28 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| Isopropyl hexanoate | 16832 | −6.4 | x −1.215 | x 40 | n/a | Ala29, Phe28, Val33 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | ||||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| Octane | 356 | −6.1 | x −1.215 | x 40 | n/a | Phe28 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | ||||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| 10-Bromoundecanoic acid | 543401 | −6.1 | x −1.215 | x 40 | n/a | Thr57, Ala29, Gln32 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Phe28, Lys22, Thr57 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| Nonanoic acid | 8158 | −6.0 | x −1.215 | x 40 | n/a | Gln32, Phe28 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | ||||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| Octanoic acid | 379 | −5.8 | x −1.215 | x 40 | n/a | Gln32, Val33, Gly25 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Gly27, Phe28, Ala29 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| 1,3,4,5-Tetrahydroxycyclohexanecarboxylic acid | 1064 | −5.6 | x −1.215 | x 40 | Asn307, Ala306, Lys229 | Val305, Thr252, Trp228 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | ||||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| Citronellol | 8842 | −5.4 | x −1.215 | x 40 | n/a | Ala306, Glu255, Asn307 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Thr252, Trp228, Arg248 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | Gln230, Lys229 | |||||

| 3-Hydroxycyclohexanone | 439950 | −5.3 | x −1.215 | x 40 | Thr54, Arg107, His94 | Thr61, Leu52, Ile63 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Glu73, Leu105 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| Neral | 643779 | −5.0 | x −1.215 | x 40 | n/a | Arg361, Thr411, Tyr441 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Met440 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| Citronellal | 7794 | −4.9 | x −1.215 | x 40 | n/a | Thr411, Met440, Pro362 | |

| y 46.730 | y 40 | Asp360, Val410, Tyr284 | |||||

| z −15.099 | z 40 | ||||||

| MMP1 (PDB ID: 1SU3) | (★) 2-Propenoic acid, 3-phenyl-, methyl ester | 7644 | −5.0 | x 34.394 | x 40 | Arg399, Tyr411, Tyr397 | Asp418, Phe436, Tyr390 |

| y −44.313 | y 40 | Phe419, Phe447, Pro449 | |||||

| z 37.396 | z 40 | Lys413 | |||||

| Geranyl acetate | 1549026 | −4.5 | x 34.394 | x 40 | Tyr411 | Arg399, Asp418, Pro449 | |

| y −44.313 | y 40 | Phe447, Lys452, Phe419 | |||||

| z 37.396 | z 40 | Tyr390, Tyr397 | |||||

| 2-Dodecenoic acid | 5282729 | −4.3 | x 34.394 | x 40 | Tyr397, Tyr411 | Lys413, Tyr390, Pro449 | |

| y −44.313 | y 40 | Phe419, Phe447, Asp418 | |||||

| z 37.396 | z 40 | ||||||

| Citronellal | 7794 | −4.0 | x 34.394 | x 40 | Arg399 | Phe419, Asp418, Tyr397 | |

| y −44.313 | y 40 | Phe436, Tyr390, Glu383 | |||||

| z 37.396 | z 40 | Pro449 | |||||

| (E)-4-Undecenal | 5283357 | −3.6 | x 34.394 | x 40 | n/a | Lys452, Asp418, Pro449 | |

| y −44.313 | y 40 | Phe436, Phe419, Phe447 | |||||

| z 37.396 | z 40 | Tyr390, Tyr397 | |||||

| Positive control | (d) Batimastat | 5362422 | −6.7 | x 34.394 | x 40 | Thr112, His113, Lys396 | Pro146, Glu110, Arg108 |

| y −44.313 | y 40 | Thr373 | Pro371, Trp398, Pro412 | ||||

| z 37.396 | z 40 | Val393 | |||||

| (d) Ilomastat | 132519 | −6.5 | x 34.394 | x 40 | His113 | Thr145, Ser142, Thr148 | |

| y −44.313 | y 40 | Leu147, Lys413, His417 | |||||

| z 37.396 | z 40 | Met414, Pro412, Gln264 | |||||

| Pro146 | |||||||

(★) Compound with the greatest affinity on each target; (a) PPARA agonist; (b) PPARD agonist; (c) PPARG agonist; (d) MMP agonist.

3.10. Identification of the Uppermost Seven Targets and Eight Compounds from Two Key Signaling Pathways against RA

Campesterol on FGF1, 26,27-Dinorergosta-5,23-dien-3β-ol on FGF2, CBMicro_013618 on TNFRSF1A, and monoolein on PRKCA on MAPK signaling pathway had significant valid affinity score to develop new promising ligands. Additionally, β-Caryophyllene on PPARA, Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol on PPARD, NSC0402953 on PPARG, and monoolein on FABP3 had an important valid score on the PPAR signaling pathway.

3.11. Toxicological Properties of 8 Compounds

Additionally, toxicological properties of Campesterol; 26,27-Dinorergosta-5,23-dien-3β-ol; CBMicro_013618; monoolein; β-Caryophyllene; Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol; and NSC0402953 were predicted by admetSAR online tool. Our result indicated that chemical compounds did not disclose Ames toxicity, carcinogenic properties, acute oral toxicity, and rat acute toxicity properties (Table 8).

Table 8.

Toxicological properties of seven key compounds in the MDT.

| Parameters | Compound Name | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campesterol | 26,27-Dinorergosta-5,23-dien-3β-ol | CBMicro_013618 | Monoolein | β-Caryophyllene | Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol | NSC0402953 | |

| Ames toxicity | NAT | NAT | NAT | NAT | NAT | NAT | NAT |

| Carcinogens | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| Acute oral toxicity | I | I | III | IV | III | I | III |

| Rat acute toxicity | 2.8078 | 2.8078 | 2.5735 | 1.0526 | 1.4345 | 2.6561 | 1.9796 |

AT: Ames toxic; NAT: Non-ames toxic; NC: Non-carcinogenic; category I means (50mg/kg≤ LD50); category II means (50mg/kg > LD50 < 500mg/kg); category III means (500mg/kg > LD50 < 5000mg/kg); category IV means (LD50 > 5000mg/kg).

4. Discussion

PPI network showed that the therapeutic efficacy of ZPFs on RA was associated with 99 targets. The KEGG pathway analysis enrichment of 99 targets revealed that 19 signaling pathways were related closely to the occurrence and progression of RA, suggesting that these signaling pathways might be remedial mechanisms of ZPFs to alleviate RA. The relationships of the 19 signaling pathways with RA are briefly discussed as follows. PPAR signaling pathway: the activation of PPAR is a good strategy to alleviate RA, which can suppress the inflammatory activity of NF-κB in fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLSs) [30]. Relaxin signaling pathway: the combined relaxin with estrogen exerts anti-inflammatory effects by dampening neutrophil function [31]. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) signaling pathway: VEGF expression level in RA patients increased significantly, compared with healthy groups; moreover, patients under RA for an extended period exerted higher VEGF expression level in serum [32]. Estrogen signaling pathway: the estrogen treatment might have an inhibitory effect on RA symptoms or delay in the onset of disease, and estrogen has anti-inflammatory activity in an animal test of RA [33]. Fc epsilon RI signaling pathway: Fc epsilon RI signaling pathway is associated with inflammatory etiology, antigen-induced autoimmune reaction, and control of lipid metabolic pathway, and damage in human joint [34]. Prolactin signaling pathway: Prolactin collaborates with other proinflammatory factors to stimulate macrophages through prolactin receptors which might be a potential therapeutic target in RA [35]. Sphingolipid signaling pathway: Sphingolipid expression level in RA elevated in the serum sample, consistent with known roles of sphingolipids related to inflammation [36]. Cyclic AMP (cAMP) signaling pathway: stimuli-induced cAMP production can exert proinflammatory effects in RA [37]. It implies that the activation of the cAMP level might drive inflammatory responses. AGE-RAGE (the receptor for advanced glycation end products) signaling pathway in diabetic complications: the expression of RAGE increased in RA patients, and IL-17 and IL-1β triggered RAGE production [37]. It suggests that the inhibition of RAGE might be a good target for RA treatment. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1(HIF-1) signaling pathway: synovial hypoxia is characterized by RA patients, leading to inflammation, cartilage destruction, and oxidative impairment [38]. Ras-associated protein-1 (RAP1) signaling pathway: The downregulation of RAP1 in RA induces ongoing inflammation due to the overproduction of free radicals [39]. Thyroid hormone signaling pathway: joint damages in thyroid gland abnormalities are due to hypothyroidism, and thyroid hormone plays a vital role in antioxidant modulation, as indicated by in vivo and in vitro tests [40,41]. Phospholipase D signaling pathway: phospholipase D1 (PLD1) is a mediator to induce proinflammatory cytokines with a reduction of the regulatory T (Treg) cell and recruitment of Th17 cell in collagen-induced arthritis mice [42]. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) signaling pathway: GnRH is a potent substance to alleviate inflammation in RA patients with a high level of GnRH [43]. Ras signaling pathway: T cells in RA patients show the Ras signalling pathway’s overactivation-related deeply to inflammation [44]. T cell receptor signaling pathway: T cell recruitment to the inflammatory sites can induce chronic inflammation and autoimmunity [45]. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase—Akt (PI3K-Akt) signaling pathway: a report demonstrated that PI3K-Akt signaling pathway was excessively activated, aggravating in overexpression Bcl-2, Mcl-1, and FLIP to result in unbalanced apoptosis of synovial cells, which is associated with occurrence and progression of RA [46,47]. Calcium signaling pathway: it was reported that the cytoplasmic calcium concentration in RA naïve CD4+ T cells is increased significantly [48]. It implies that the calcium signaling pathway is involved intensely in inflammatory responses.

MAPK signaling pathway: a study demonstrated that andrographolide with anti-inflammatory activities has potent anti-RA efficacy, inhibiting MAPK pathway [49]. This report is consistent with our result via network pharmacology analysis.