Faculty from groups that are underrepresented in medicine encounter unique challenges to advancement within academic medicine. The authors describe a fellowship created for junior underrepresented in medicine academic faculty in Family Medicine focused on promoting writing skills and scholarship.

Supplemental digital content is available in the text.

Key Words: faculty development, family medicine, underrepresented minority faculty

Abstract

Objectives

The diversity of the US physician workforce lags significantly behind the population, and the disparities in academic medicine are even greater, with underrepresented in medicine (URM) physicians accounting for only 6.8% of all US medical school faculty. We describe a “for URM by URM” pilot approach to faculty development for junior URM Family Medicine physicians that targets unique challenges faced by URM faculty.

Methods

A year-long fellowship was created for junior URM academic clinician faculty with funding through the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Project Fund. Seven junior faculty applied and were accepted to participate in the fellowship, which included conference calls and an in-person workshop covering topics related to writing and career advancement.

Results

The workshop included a mix of prepared programming on how to move from idea to project to manuscript, as well as time for spontaneous mentorship and manuscript collaboration. Key themes that emerged included how to address the high cost of the minority tax, the need for individual passion as a pathway to success, and how to overcome imposter syndrome as a hindrance to writing.

Conclusions

The “for URM by URM” approach for faculty development to promote writing skills and scholarship for junior URM Family Medicine physicians can address challenges faced by URM faculty. By using a framework that includes the mentors’ lived experiences and creates a psychological safe space, we can address concerns often overlooked in traditional skills-based faculty development programs.

Key Points

A “for URM (underrepresented in medicine), by URM” approach created a safe space for junior URM faculty to discuss their experiences with navigating the field of academic medicine.

The minority tax and imposter syndrome were identified as barriers to scholarly productivity and career development.

Individual passion for clinical and scholarly topics was identified as a pathway to success in academic medicine.

Groups underrepresented in medicine (URM), including Latinx, Black or African American, and Indigenous people, represent only 6.8% of US medical school faculty,1 compared with one-third of the US population.2 This underrepresentation has led to a dearth of mentorship, sponsorship, advancement, and retention of URM faculty in academic medicine.3–5 URM faculty also experience a range of disparities described as the “minority tax,” including disparities in diversity efforts, isolation, lack of faculty development, and racism. This causes the few URM faculty remaining in academic medicine to suffer a lack of psychological safe space, bias, and discrimination.4

Faculty development programming can address challenges faced by URM faculty when the institutional culture impairs their success; however, skills-based faculty development models may not address the unique needs of URM faculty,1,4,6 limiting the results seen in URM recruitment, retention, or promotion.1,7,8 Existing models of faculty development can be enhanced by using an individualized approach that takes into account participants’ cultures and backgrounds; addressing institutions’ hidden curriculum; acknowledging racism, historical injustices, and inequities experienced by minority populations; and providing a specialty-focused approach.

In this article, we describe a longitudinal, experiential approach for URM faculty development in Family Medicine led by URM mentors. Because of the importance of scholarly activity for faculty advancement in academic medicine,9 we focused our initial intervention on understanding the research process and building professional networks to support scholarship. Using qualitative feedback from program participants, we describe how this URM-led faculty development for URM faculty addressed gaps in scholarship support for junior URM faculty in Family Medicine.

Methods

The project was initiated by a group of senior Family Medicine leaders, including a Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) board member; a foundation trustee and chair of the STFM URM Initiative, a senior associate dean of academic affairs; and an associate vice president of health equity, diversity, and inclusion. Mentors’ experience in supporting URM faculty development include being widely published in the literature on issues involving URM faculty and learners as well as being recognized nationally for work in this space.

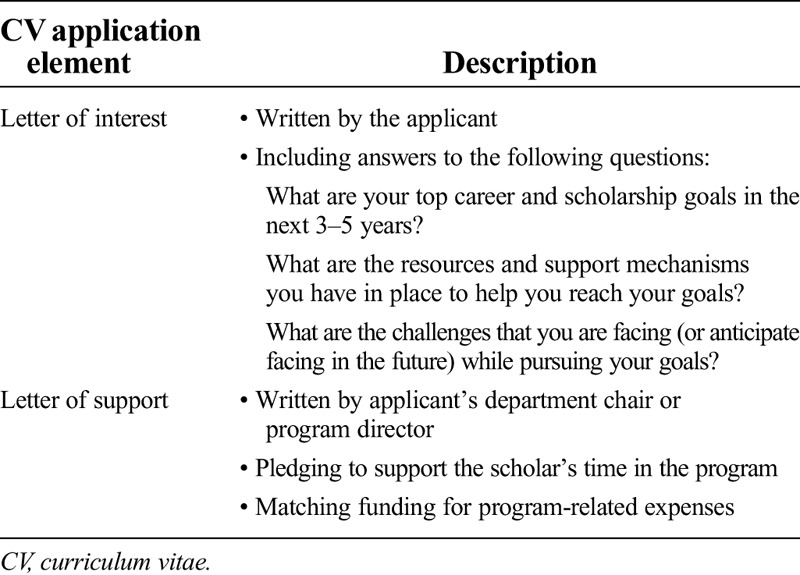

Institutional review board approval was received for this project. Program mentors secured funding for a 1-year longitudinal URM writing fellowship through the STFM Project Fund. Eligible participants (physician faculty at or below the rank of assistant professor) were recruited via a STFM listserv and at the 2019 STFM annual conference. Application requirements (Table 1) encouraged applicants to reflect on their professional journey and share details that would help the mentors meet individual participant needs. All 7 applicants were invited to participate in the inaugural cohort.

Table 1.

Fellowship application requirements

Following an introductory conference call, a 3-day in-person workshop was held at one of the mentors’ institutions. The “for URM by URM” faculty development approach of the workshop was designed to provide a shared URM narrative and create a psychological safe space.10–12 The workshop was conducted away from the fellows’ home institutions in a secluded conference room with little foot traffic, thereby creating a physically safe space. The workshop content, summarized in the Supplemental Digital Content Appendix (http://links.lww.com/SMJ/A238) included learning from leaders in academic medicine, reflecting on personal career goals, and putting collaborative scholarship into practice by drafting a manuscript as a group. At the conclusion of the workshop, attendees completed a Qualtrics survey designed by the mentors to capture the fellows’ thoughts about the experience using open-ended questions. Survey results and notes from the workshop were reviewed by the URM faculty mentors, and key themes were identified through discussion and consensus.

Results

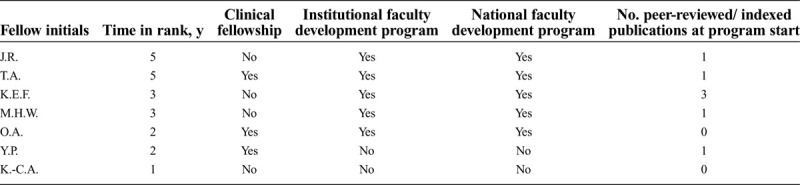

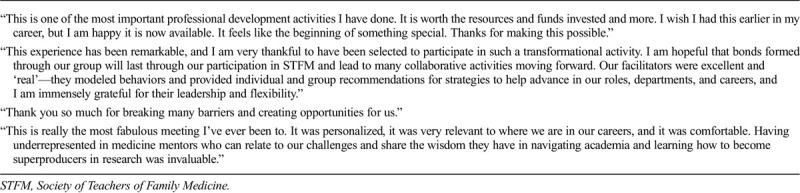

Participants included 6 women and 1 man from 6 institutions, all of whom identified as Black or African American or Latinx. Participants’ professional characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Representative qualitative feedback collected from participants at the end of the workshop is summarized in Table 3. Key themes emerging from the discussion and participant feedback included the high cost of the minority tax, individual passion as a pathway to success, and overcoming imposter syndrome.

Table 2.

Fellow profile

Table 3.

Participant written feedback at the end of the workshop

The High Cost of the Minority Tax

Fellows shared their experiences of being asked to serve on multiple committees, recruit minority clinicians and students, and provide diversity and equity education, with little recognition for these efforts. Clinically, fellows shared pressures to care for racially, ethnically, and linguistically concordant populations, decreasing available time for scholarly work. Mentors validated these experiences and provided the fellows with skills to advocate for themselves when faced with the minority tax.

Individual Passion as a Pathway to Success

Fellows were encouraged to develop a scholarly portfolio that raised awareness of the issues they supported through community and advocacy efforts and that reflected their passions. This requires purposefully accepting or declining new roles to position oneself to become a content expert in the area about which they are most passionate.

Overcoming Imposter Syndrome

Fellows discussed how a lack of peers and mentors to help address barriers facing URM faculty contributes to imposter syndrome, and described finding validation outside work, such as family or friends. The discussion addressed how imposter syndrome can decrease time and confidence for scholarly writing. Fellows were encouraged to be confident in their role and work as academic family physicians.

Discussion

The STFM URM Writing Fellowship integrated mentoring, instruction on academic writing, and networking opportunities,6 incorporating both skills-based training and the lived experience of URM mentors. Leadership by URM faculty created a psychological safe space, characterized by mutual trust and respect, where participants openly discussed the challenges faced by URM faculty, including racism, isolation, and the minority tax.6,10,13 Feedback from participating faculty was overwhelmingly positive, with multiple participants remarking that they felt inspired, energized, and equipped to increase their scholarly productivity and advance their academic careers. Incorporating such URM-to-URM mentorship in future faculty development programs may increase the retention, promotion, and job fulfillment of URM faculty.

URM faculty face the undervaluing of their work and barriers to professional advancement. As such, connecting with mentors who understand the challenges faced by URM faculty is an important strategy for overcoming these barriers and fostering retention and promotion.14 In Family Medicine, offering URM-focused faculty development opportunities has been shown to increase URM representation.15 Our fellowship built upon this approach by beginning with creating a safe psychological space and progressing through the knowledge and skills needed to help participants repeal the minority tax. Moving forward, we plan on collecting follow-up data on participants’ scholarship, career advancement, and fulfillment in academic medicine, as well as exploring opportunities to develop similar programming for other specialties.

Given the prevalent barriers to career advancement among URM faculty in academic medicine, other organizations may wish to consider similar programs to support their faculty. Based on our experience, key requirements for program success include identifying senior faculty mentors with expertise in faculty development, creating a safe space for junior faculty participants to express their concerns, and identifying specific goals to be addressed through the program (eg, increasing scholarship to strengthen participants’ candidacy for promotion and tenure). Partnerships among institutions can pool resources and experience to provide such programs to a greater number of faculty. Whereas URM faculty development programs can help participants overcome a range of barriers, from imposter syndrome to the minority tax, it also is important that senior leaders in academic medicine work toward dismantling these barriers within their institutions and across the medical profession,16 recognizing that these barriers are part of a deficient system and not the characteristics of a URM faculty member.17 Concerted institutional efforts to address barriers to URM faculty advancement and individual or small-group mentorship, such as those described in the present article, can help achieve equitable recruitment, retention, and promotion for future generations of faculty.

Acknowledgments

We applaud the efforts of the Family Medicine department chairs who invested in their URM faculty members, both financially and with support of faculty time. We thank the STFM for its grant support of this faculty development opportunity.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (http://sma.org/smj).

J.R., K.E.F., Y.P., J.E.R., K.M.C., and J.W. have received compensation from the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Project Fund. J.W. is the president of the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine and is a content reviewer for the online journal Bottom Line. The remaining authors did not report any financial relationships or conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Juan Robles, Email: jcrobles20@gmail.com.

Tanya Anim, Email: tanya.anim@leehealth.org.

Maria Harsha Wusu, Email: mwusu@msm.edu.

Krys E. Foster, Email: Krys.Foster@jefferson.edu.

Yury Parra, Email: yury.parra.fm@gmail.com.

Octavia Amaechi, Email: OAmaechi@srhs.com.

Kari-Claudia Allen, Email: Kari-Claudia.Allen@uscmed.sc.edu.

Kendall M. Campbell, Email: campbellke16@ecu.edu.

Dmitry Tumin, Email: tumind18@ecu.edu.

Judy Washington, Email: Judy.Washington@atlantichealth.org.

References

- 1.Guevara JP Adanga E Avakame E, et al. Minority faculty development programs and underrepresented minority faculty representation at US medical schools. JAMA 2013;310:2297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association of American Medical Colleges . Diversity in medicine: facts and figures 2019. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-18-percentage-all-active-physicians-race/ethnicity-2018. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- 3.Fang D Moy E Colburn L, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in faculty promotion in academic medicine. JAMA 2000;284:1085–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ 2015;15:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cropsey KL Masho SW Shiang R, et al. Why do faculty leave? Reasons for attrition of women and minority faculty from a medical school: four-year results. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:1111–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez JE Campbell KM Fogarty JP, et al. Underrepresented minority faculty in academic medicine: a systematic review of URM faculty development. Fam Med 2014;46:100–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nivet MA Taylor VS Butts GC, et al. Diversity in academic medicine no. 1 case for minority faculty development today. Mt Sinai J Med 2008;75:491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adanga E Avakame E Carthon MB, et al. An environmental scan of faculty diversity programs at U.S. medical schools. Acad Med 2012;87:1540–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braxton MM Infante Linares JL Tumin D, et al. Scholarly productivity of faculty in primary care roles related to tenure versus non-tenure tracks. BMC Med Educ 2020;20:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edmondson A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm Sci Q 1999;11:33. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheepers RA van den Goor M Arah OA, et al. Physicians' perceptions of psychological safety and peer performance feedback. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2018;38:250–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aranzamendez G, James D, Toms R. Finding antecedents of psychological safety: a step toward quality improvement. Nurs Forum 2015;50:171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahoney MR Wilson E Odom KL, et al. Minority faculty voices on diversity in academic medicine: perspectives from one school. Acad Med 2008;83:781–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zambrana R Ray R Espino M, et al. “Don’t leave us behind”: the importance of mentoring for underrepresented minority faculty. Am Educ Res J 2015;52:32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rust G Taylor V Herbert-Carter J, et al. The Morehouse faculty development program: evolving methods and 10-year outcomes. Fam Med 2006;38:43–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodríguez JE, Tumin D, Campbell KM. Sharing the power of white privilege to catalyze positive change in academic medicine. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2021;8:539–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez JE, Campbell KM, Adelson WJ. Poor representation of blacks, latinos, and native americans in medicine. Fam Med 2015;47:259–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]