Abstract

Recent advancements in molecular recognition have provided additional diagnostic and treatment approaches for multiple diseases, including autoimmune disorders and cancers. Research investigating how the composition of biological fluids is altered during disease progression, including differences in the expression of the small molecules, proteins, RNAs, and other components present in patient tears, saliva, blood, urine, or other fluids, has provided a wealth of potential candidates for early disease screening; however, adoption of biomarker screening into clinical settings has been challenged by the need for more robust, low-cost, and high-throughput assays. This review examines current approaches in molecular recognition and biosensing for the quantification of biomarkers for disease screening and diagnostic outcomes.

Keywords: Biosensing, molecular recognition, hydrogels, localized surface plasmon resonance, differential sensing

Graphical Abstract

1.1. Introduction

Biosensors are analytical devices that incorporate sensing of a biological analyte and are used in clinical settings for detection of disease indicators in biological fluids for disease monitoring and drug discovery. The key components of a biosensor are the recognition element (often referred to as a receptor), which interacts with the analyte or substrate of interest, and the signal transducing component, which then transmits a molecular recognition event (through interaction between the analyte and receptor) as a detectable signal (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Components of a standard biosensor and their relation to an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). a.) Biosensors are primarily composed of a receptor and signal transducing agent. The analyte interacts with the receptor either covalently or non-covalently, to produce a recognition event. This is then converted to a measurable response by the transducer to obtain a signal for the user to read and interpret. b.) The most common biosensor used in research and clinical settings is the ELISA. The sandwich ELISA is the most prevalent, and in this case, the receptor is a capture antibody which is highly specific to interact with the target protein (antigen). Another enzyme-labeled antibody is added which facilitates detection of the analyte. A reaction between the substrate and enzyme produces a measurable color change which correlates to antigen concentrations. This figure was created using BioRender.com.

Several important properties of biosensors, such as their sensitivity, selectivity, reproducibility, and affordability, must be taken into consideration during device development.[1] Sensitivity can be defined in multiple ways; therefore, it is important to clearly state the terminology (such as, “limit of blank” or “limit of detection”) and methods used to obtain device sensitivity.[2,3] A sensor is considered to be selective only if it reacts with the target analyte and not with other components in a mixture. The reproducibility of biosensor components, as well as of the resulting signal, are critical aspects to take into consideration for device fabrication and outcome interpretation. Lastly, affordability is important for the translation of the developed screening and diagnostic biosensors to targeted audiences and into clinical settings.

1.2. Strategies for Identifying Biomarkers

Molecular recognition approaches for disease diagnostic and screening applications have largely been enabled by advances in the identification of small molecules, genes, and proteins that allow researchers to observe how the presence of the disease indicators alters the natural abundance and structure of these markers.[4] However, the complexity of biological fluids, which consist of many high abundant compounds and proteins with similar structures and properties to potential analytes, can make identification of biomarkers difficult, especially for potential markers that are only present in low concentrations. This problem is further compounded by many low abundant markers experiencing even lower orders of magnitude changes in concentration between healthy and diseased patients that can mask disease-related deviations when compared to natural variations in baseline concentrations between patients. While small molecule markers are more amenable to traditional analysis, the complex relationships between the sequence and structure of proteins and nucleic acids make identification more challenging, although it also offers a promising opportunity for disease biomarker discovery. Mass spectroscopy remains the dominant technique for protein identification, thanks to the development of techniques including matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization and electrospray ionization, which allow for minimal fragmentation of macromolecules during ionization.[5,6] Furthermore, the increased use of on-line fractionation techniques [7] for protein separation, as opposed to two-dimensional gel electrophoresis which can be time consuming and challenging to reproduce, has enabled high-throughput screening of biological fluids. For DNA and RNA markers, two of the main methods for investigating potential biomarkers are microarray profiling [8], which uses an array of known base sequences to measure differences in gene expression between the sample and reference, and DNA and RNA sequencing [9,10], which provides a more comprehensive overview of the nucleotide composition. As a result of the increasing number of studies on the chemical, proteomic, and transcriptomic changes caused by various diseases, there is a growing library of potential biomarkers and thus, therapeutics which have been developed as a result of advancements related to the screening and monitoring of disease specific compounds.[11,12]

1.3. Developments in Molecular Recognition

In developing sensors that are capable of recognizing the target analyte, the choice of molecular recognition approach is dictated not only by the chemical properties of the analyte, but those of the competing compounds in the biological sample.[13] As a result, it is important to choose the molecular recognition approach that is best suited for the level of accuracy required by the assay. When developing diagnostic tests, which are intended to provide a confirmation of the suspected diagnosis, the need to minimize unwanted interactions with other molecules in the sample that could lead to false positives necessitates molecular recognition approaches that are able to achieve high-specificity, such as antibody-antigen pairings or enzymes with high affinity for the target biomarker or substrate. In contrast, screening tests are intended to provide a low-cost and rapid assay that can be administered to a larger patient population in order to detect diseases in the earliest stages.[14] Because any potential positive results from a screening test will be followed up by subsequent diagnostic tests, lower levels of sensitivity are acceptable, which permits the use of rational material design strategies for receptor recognition that can offer the use of lower-cost materials with non-stringent storage requirements at the expense of higher rates of false positives.

Researchers have studied many classes of materials as potential semi-selective recognition elements, which is illustrated in Table I. For pseudo-biological materials, aptamers [15,16] have been widely explored as alternatives to natural antibodies and allow for more control over chain length and sequence. These materials can also be combined with synthetic receptor designs, such as hydrogels which offer high-tunability of the network properties that enable the creation of a wide array of structures, functionalities, and mesh size.[17,18] Additionally, while hydrogels alone offer less selective targeting of disease biomarkers compared to natural structures, the combination of size exclusion, charge exclusion, and non-covalent interactions can enable detection in cases where there are few competing agents.[19] Furthermore, molecularly-imprinted polymers [20–22] that use the target biomarker as a template during the assembly of the hydrogel have been studied as a method of replicating the higher affinity of natural receptors. For small molecules, metal-organic frameworks [23–25] have similarly been designed to control the affinity of the target biomarker through pore size and non-covalent interactions. Through these strategies, researchers are creating biosensors that are increasingly able to reach the levels of selectivity and accuracy expected with conventional screening and diagnostic tests.

Table I:

Summary of current research approaches in molecular recognition and biosensing

| Disease | Biomarker | Biological Sample | Molecular Recognition Approach | Signal Transducing Agent | Biosensing Approach | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease | Amyloid-β Tau protein | Cerebral spinal fluid Blood | Antibody | FITC-labeled antibody | Optical, florescence | [41] |

| Carcinoid tumors | 5-hydroxytryptamine 5-hydroxyindole-3-acetic acid | Plasma | Metal–organic framework | Lanthanide metal-organic framework | Optical, fluorescence | [23] |

| Breast cancer | Cancer antigen 15-3 HER2-ECD | Serum | Molecularly-imprinted polymer | Voltmeter | Electrochemical | [20,42] |

| Lung cancer | Hexanal | Breath | Molecularly-imprinted polymer Carbon nanotubes | Voltmeter | Electrochemical | [22] |

| Lung cancer | Hexanal | Breath | Molecularly-imprinted polymer | Quartz-crystal microbalance | Gravimetric | [21] |

| Parkinson’s disease/Alzheimer’s disease | Glutamic acid | Plasma | Metal-organic framework | Lanthanide metal-organic framework | Optical, fluorescence | [24] |

| Acute myocardial infraction | Creatine kinase | Serum | Metal-organic framework | Lanthanide metal-organic framework | Optical, fluorescence | [25] |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | Lactoferrin Lysozyme | Tears | Polymer | Gold nanoshell | Optical, localized surface plasmon resonance | [19] |

| Diabetes | Glucose | Saliva | Polymer | Quartz-crystal microbalance | Gravimetric | [43] |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Amyloid-β Tau protein | Blood | Antibody | Gold nanospheres/nanorods | Optical, localized surface plasmon resonance | [44] |

| Breast cancer | Cancer antigen 15-3 | Serum | Amino acid | Gold nanocluster | Optical, fluorescence | [45] |

| Hyperuricemia | Uric acid | Serum | Enzyme | Zinc oxide/Lithium tantalate thin film | Acoustic | [46] |

| Diabetes | Glucose | Saliva | Enzyme | Potentiostat | Electrochemical | [47] |

1.4. Conventional Biosensing Approaches

1.4.1. Optical Biosensors

The most commonly used biosensors are those based on colorimetric detection methods such as the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). Colorimetric biosensors often utilize enzymes to convert a substrate molecule into a product with a change in color. While there are many different types of ELISAs (direct, indirect, sandwich, or inhibition), antibodies are utilized as the molecular recognition agents in all cases, and are labeled with an enzyme (i.e., horse radish peroxidase). The enzyme catalyzes a change in the molecular substrate, resulting in a detectable color change (Figure 1b). The use of ELISAs offers high selectivity and sensitivity and possesses advantages that pertain to the easy-to-use, low-cost equipment required (e.g., plate readers, smart phones, etc.). However, the disadvantage of ELISAs lie in the need for high-cost biomacromolecules (i.e., antibodies and enzymes). While the use of antibodies results in high specificities, alternative molecular recognition agents for ELISA-type assays are continually being investigated (i.e., recognitive polymers).[26]

Furthermore, the unique optical properties of gold nanoparticles have enabled their use as signal transducing materials for a variety of biosensors such as optical, electrochemical, piezoelectric, and colorimetric biosensors.[27] Gold possesses exceptional spectral properties because of the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) exhibited by gold nanoparticles, which occurs when the material is excited by incident light of a wavelength which is larger than that of the size of the particle.[28] The resulting LSPR absorption peak is dependent on the nanoparticle size, shape, composition, and the refractive index of the surrounding medium.[28] The specific dependence of the LSPR wavelength on the local refractive index makes LSPR a useful tool in sensing applications. These gold nanoparticle-based biosensors employ nanomaterials which are either immobilized for signal amplification or in suspension, which provides an opportunity for label-free detection of analytes. Furthermore, gold nanoparticles are often used in colorimetric assays as the materials display different colors depending on their aggregation state, size, and shape.[27] The projected color changes upon gold nanoparticle aggregation or dispersion of aggregates is what enables colorimetric detection using these materials as signal transducers. Colorimetric assays using gold nanoparticles have been utilized to detect a variety of analytes that include proteins, enzymes, small molecules, and DNA sequences.[29,30]

1.4.2. Fluorescence Biosensors

Another common class of biosensors is based on fluorescence, which transmit signals due to a change in fluorescence lifetime, fluorescence anisotropy, or fluorescence intensity. These properties are highly sensitive to changes in the local environment, making fluorophores (compounds that emit light in response to photoexcitation) excellent tools for biosensing.

Examples of fluorescence-based techniques include fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) and fluorescence quenching. FRET occurs when the wavelength of light emitted by a donor fluorophore is absorbed by an acceptor molecule.[31] For use in biosensing, one of the fluorophores can be immobilized on the receptor and the other on the ligand. When a binding event occurs (although distant dependent), a signal will be generated. Fluorescence quenching differs from FRET by having a molecule or material that quenches the light emitted by the donor (in place of another fluorophore) as the acceptor or quencher. Static quenching is utilized for sensing applications due to the formation of a molecular complex by a fluorophore and quencher, which is then used to transduce binding events.

1.4.3. Turbidimetric Biosensors

The use of particles to enhance light scattering which occurs upon the formation of antibody-antigen immunocomplexes was established in the 1950’s.[32] Diagnostic tests based on this concept are referred to as “particle enhanced turbidimetric (immuno)assays” (PETAs) where receptors (i.e., antibodies) are immobilized on the surface of latex spheres (i.e., polystyrene). Upon introduction of the target antigen, the multivalent binding of the antibody-antigen complexes results in particle aggregation (also agglutination). This affects the turbidity of the solution by increasing the light scattering due to increased particle size. In addition to scattering, changes in absorbance and/or interference can also contribute to changes in turbidity.[33]

Originally, these methods provided a “yes/no” outcome depending on the presence or absence of the target analyte. However, using spectrophotometers to detect changes in light scattering (as opposed to the naked eye) enables these tests to provide quantitative results based on changes in analyte concentration.[34]

1.5. Evaluation of Biosensor Performance

Because the potential applications of a biosensor are dependent on how well the sensor compares to existing “gold standards,” the performance of the biosensor and how its molecular recognition is evaluated by the limit of detection, biomarker selectivity, and effective concentration range are extremely important when choosing the molecular recognition and transducing approaches that will be most effective for the intended application. For evaluating the selectivity of target biomarkers to the recognition element, many studies rely on comparisons of the signal response between the analyte and other similar proteins, molecules, or DNA/RNA sequences selected to be representative of potential competing species in the actual sample. However, while these results are certainly important when assessing the performance of the sensor, they often fail to give a complete picture of the binding affinity to the molecular recognition element. Techniques such as quartz crystal microbalance [35,36] and surface plasmon resonance [37,38] can offer greater insight into the selectivity and binding constants for the analyte and receptor over competing species. Additionally, the objective of many diagnostic approaches focuses on achieving lower limits of detection in order to better identify low-abundance species; however, other considerations including the rate of false negatives, working range, and reproducibility are also important when choosing an approach for future clinical applications and reporting those values where applicable would be of great benefit to studies of biosensor performance.

Another focus for future investigation is differential sensing, which uses a sensor array with cross-reactive receptors to differentiate analytes upon analyte-receptor interactions. The signal output pattern generated is linked to either a specific, or mixture, of analyte(s) using multivariate analysis tools such as linear discriminant analysis and principal component analysis.[33] Implementation of differential sensing routines enable the use of receptors with lower selectivity (reducing receptor cost and stability requirements) compared to those commonly used in medical diagnostic practices. In addition, the output patterns obtained can be used to analyze biomarker concentrations, as well as the consistency of one biological sample to the next.[39]

1.6. Conclusions and Future Outlook

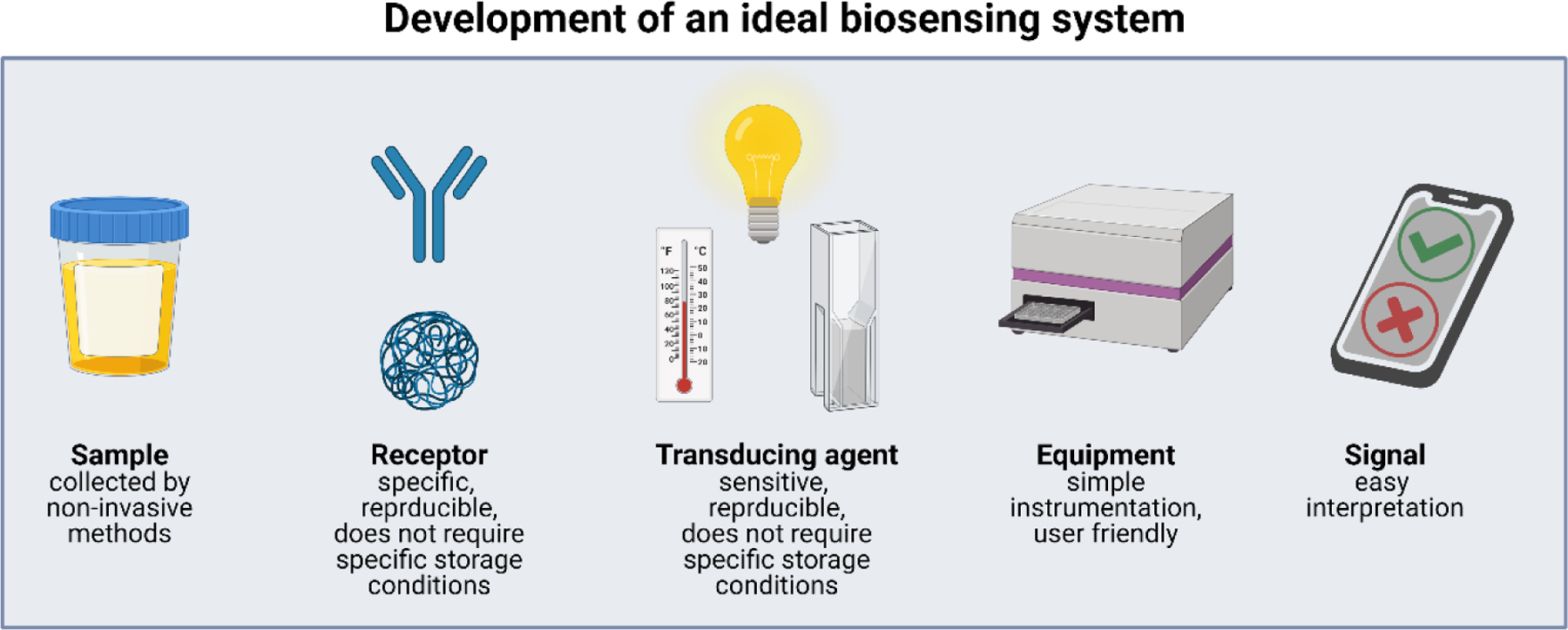

As researchers look to translate innovative biosensors toward clinical adoption, it is important to pay attention to designs that will offer the greatest advantages over existing technologies. In response to the treatment delays and often increased costs associated with sending samples to a laboratory for analysis, there is a growing push for point-of-care screening and diagnostic tools that can be administered during the patient’s initial visit and interpreted without the need for expensive equipment. Such approaches favor molecular recognition strategies and transducing methods that have minimal sample processing requirements, such as being able to read the biomarkers directly from the biological fluid, and produce a response that can be read as a clear positive or negative, rather than requiring additional training to interpret the readout (Figure 2). Additionally, tests that have a long shelf-life and simple storage requirements are more desirable, especially for situations where they may be administered in remote locations or low resource settings. Furthermore, additional studies into tests that can screen for multiple biomarkers from a single sample will greatly reduce constraints such as throughput limitations and small sample volumes that can be associated with single assays.[40] Advancements in both molecular recognition and sensor design are well-suited to addressing these challenges and making early disease detection and treatment options more accessible to patients, improving their quality of life.

Figure 2.

Key design considerations for the development of an ideal biosensor. A patient sample should be obtained non-invasively with minimal manipulation prior to interaction with the receptor. Receptors should be specific to analyte(s), reproducible (no batch-to-batch variability), and used “off the shelf”. Transducing agents should also be sensitive, specific, reproducible, stable and have no specific storage requirement. Measurements should be obtained using minimal equipment, and the results obtained should be easy to interpret. All of these steps could be performed by minimally trained personnel. This sensing platform has the potential to be used for point-of-care diagnostics and could be conducted in remote areas. This figure was created using BioRender.com.

Current research in the field has excelled in creating innovate biosensing techniques through the use of novel transducing elements. However, more work investigating molecular recognition strategies (especially through the use of synthetic receptors) is needed to enhance biosensing platforms. Additionally, further development of multiplex, differential, and semi-selective sensors that can measure multiple markers in a single, high-throughput assay are necessary in order for the benefits of biomarker screening assays to justify their use in place of current gold-standard tests, which can become cost prohibitive in cases where dozens of individual markers must be monitored. New approaches for the recognition of biomarkers in complex biological fluids is one area that can result in great impact on the future adoption of early disease screening through lowering costs, reducing the storage limitations, and enabling the simultaneous profiling of multiple markers at once.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01EB022025. In addition, N.A.P. acknowledges support from the Cockrell Family Chair Foundation, the office of the Dean of the Cockrell School of Engineering at the University of Texas at Austin (UT) for the Institute for Biomaterials, Drug Delivery, and Regenerative Medicine, and the UT-Portugal Collaborative Research Program. During this work, A.C.M was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1610403). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests. Given their roles as guest co-editors, Nicholas A. Peppas and Marissa E. Wechsler had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and have no access to information regarding its peer-review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to José del R. Millán. Given his role as an Editorial Board Member, Nicholas A. Peppas had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and had no access to information regarding its peer-review.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Hammond JL, Bhalla N, Rafiee SD, Estrela P: Localized surface plasmon resonance as a biosensing platform for developing countries. Biosensors 2014, 4:172–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armbruster DA, Pry T: Limit of blank, limit of detection and limit of quantitation. Clin Biochem Rev 2008, 29Suppl 1:S49–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Methods Committee A, Evans WH, Lord DW, RipleyandDr R Wood BD, J Wilson as Secretary with J: Recommendations for the definition, estimation and use of the detection limit. Analyst 1987, 112:199–204. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prince HE: Biomarkers for diagnosing and monitoring autoimmune diseases. Biomarkers 2005, 10Suppl 1:44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geyer PE, Holdt LM, Teupser D, Mann M: Revisiting biomarker discovery by plasma proteomics. Mol Syst Biol 2017, 13:942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Aneed A, Cohen A, Banoub J: Mass spectrometry, review of the basics: Electrospray, MALDI, and commonly used mass analyzers. Appl Spectrosc Rev 2009, 44:210–230. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas SL, Thacker JB, Schug KA, Maráková K: Sample preparation and fractionation techniques for intact proteins for mass spectrometric analysis. J Sep Sci 2021, 44:211–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang S, Zeng X, Ding T, Guo L, Li Y, Ou S, Yuan H: Microarray profile of circular RNAs identifies hsa-circ-0014130 as a new circular RNA biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu H, Wang C, Song H, Xu Y, Ji G: RNA-Seq profiling of circular RNAs in human colorectal Cancer liver metastasis and the potential biomarkers. Mol Cancer 2019, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J, Dean DC, Hornicek FJ, Shi H, Duan Z: RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) and its application in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2019, 152:194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castagnola M, Scarano E, Passali GC, Messana I, Cabras T, Iavarone F, Cintio G Di, Fiorita A, Corso E De, Paludetti G: Salivary biomarkers and proteomics: Future diagnostic and clinical utilities. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2017, 37:94–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanash SM, Pitteri SJ, Faca VM: Mining the plasma proteome for cancer biomarkers. Nature 2008, 452:571–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Culver HR, Clegg JR, Peppas NA: Analyte-Responsive Hydrogels: Intelligent Materials for Biosensing and Drug Delivery. Acc Chem Res 2017, 50:170–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis G, Sheringham J, Lopez Bernal J, Crayford T: Mastering Public Health. CRC Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saraf N, Woods ER, Peppler M, Seal S: Highly selective aptamer based organic electrochemical biosensor with pico-level detection. Biosens Bioelectron 2018, 117:40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Figueroa-Miranda G, Wu C, Willbold D, Offenhäusser A, Mayer D: Electrochemical dual-aptamer biosensors based on nanostructured multielectrode arrays for the detection of neuronal biomarkers. Nanoscale 2020, 12:16501–16513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seliktar D: Designing Cell-Compatible Hydrogels. 2012, 336:1124–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reuther JF, Dahlhauser SD, Anslyn EV.: Tunable Orthogonal Reversible Covalent (TORC) Bonds: Dynamic Chemical Control over Molecular Assembly. Angew Chemie - Int Ed 2019, 58:74–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Culver HR, Wechsler ME, Peppas NA: Label-Free Detection of Tear Biomarkers Using Hydrogel-Coated Gold Nanoshells in a Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance-Based Biosensor. ACS Nano 2018, 12:9342–9354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This paper uses hydrogel-coated gold nanoshells for semiselective detection of tear proteins in solution.

- 20.Pacheco JG, Rebelo P, Freitas M, Nouws HPA, Delerue-Matos C: Breast cancer biomarker (HER2-ECD) detection using a molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensor. Sensors Actuators, B Chem 2018, 273:1008–1014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L, Wu Y, Li G, Xu H, Gao J, Zhang Q: Superhydrophobic n-octadecylsiloxane (PODS)-functionalized PDA-PEI film as efficient water-resistant sensor for ppb-level hexanal detection. Chem Eng J 2020, 399:125755. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janfaza S, Banan Nojavani M, Nikkhah M, Alizadeh T, Esfandiar A, Ganjali MR: A selective chemiresistive sensor for the cancer-related volatile organic compound hexanal by using molecularly imprinted polymers and multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Microchim Acta 2019, 186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu S, Lin Y, Liu J, Shi W, Yang G, Cheng P: Rapid Detection of the Biomarkers for Carcinoid Tumors by a Water Stable Luminescent Lanthanide Metal–Organic Framework Sensor. Adv Funct Mater 2018, 28:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia T, Wan Y, Yan X, Hu L, Wu Z, Zhang J: The ratiometric detection of the biomarker Ap5A for dry eye disease and physiological temperature using a rare trinuclear lanthanide metal-organic framework. Dalt Trans 2021, 50:2792–2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Zhou S, Lu S, Tu D, Zheng W, Liu Y, Li R, Chen X: Lanthanide Metal-Organic Framework Nanoprobes for the in Vitro Detection of Cardiac Disease Markers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019, 11:43989–43995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fodey T, Leonard P, O’Mahony J, O’Kennedy R, Danaher M: Developments in the production of biological and synthetic binders for immunoassay and sensor-based detection of small molecules. TrAC - Trends Anal Chem 2011, 30:254–269. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aldewachi H, Chalati T, Woodroofe MN, Bricklebank N, Sharrack B, Gardiner P: Gold nanoparticle-based colorimetric biosensors. Nanoscale 2018, 10:18–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo L, Jackman JA, Yang HH, Chen P, Cho NJ, Kim DH: Strategies for enhancing the sensitivity of plasmonic nanosensors. Nano Today 2015, 10:213–239. [Google Scholar]; ** This paper reviews strategies for improving the sensitivity of plasmonic nanosensors catagorized by: (1) sensing based on target-induced local refractive index changes, (2) colorimetric sensing based on LSPR coupling, and (3) amplification of detection sensitivity based on nanoparticle growth.

- 29.Monteiro JP, Predabon SM, da Silva CTP, Radovanovic E, Girotto EM: Plasmonic device based on a PAAm hydrogel/gold nanoparticles composite. J Appl Polym Sci 2015, 132:n/a-n/a. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inci F, Tokel O, Wang S, Gurkan UA, Tasoglu S, Kuritzkes DR, Demirci U: Nanoplasmonic quantitative detection of intact viruses from unprocessed whole blood. ACS Nano 2013, 7:4733–4745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu L, He F, Yu Y, Wang Y: Application of FRET Biosensors in Mechanobiology and Mechanopharmacological Screening. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020, 8:595497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singer JM, Plotz CM: The latex fixation test: I. Application to the serologic diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med 1956, 21:888–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Culver HR, Sharma I, Wechsler ME, Anslyn EV, Peppas NA: Charged poly(: N - isopropylacrylamide) nanogels for use as differential protein receptors in a turbidimetric sensor array. Analyst 2017, 142:3183–3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ortega-Vinuesa JL, Molina-Bolívar JA, Peula JM, Hidalgo-Álvarez R: A comparative study of optical techniques applied to particle-enhanced assays of C-reactive protein. J Immunol Methods 1997, 205:151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clegg JR, Ludolph CM, Peppas NA: QCM-D assay for quantifying the swelling, biodegradation, and protein adsorption of intelligent nanogels. J Appl Polym Sci 2020, 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abellán-Flos M, Timmer BJJ, Altun S, Aastrup T, Vincent SP, Ramström O: QCM sensing of multivalent interactions between lectins and well-defined glycosylated nanoplatforms. Biosens Bioelectron 2019, 139:111328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qu JH, Dillen A, Saeys W, Lammertyn J, Spasic D: Advancements in SPR biosensing technology: An overview of recent trends in smart layers design, multiplexing concepts, continuous monitoring and in vivo sensing. Anal Chim Acta 2020, 1104:10–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shpacovitch V, Hergenröder R: Surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based biosensors as instruments with high versatility and sensitivity. Sensors (Switzerland) 2020, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diehl KL, Anslyn EV.: Array sensing using optical methods for detection of chemical and biological hazards. Chem Soc Rev 2013, 42:8596–8611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.You L, Zha D, Anslyn EV.: Recent Advances in Supramolecular Analytical Chemistry Using Optical Sensing. Chem Rev 2015, 115:7840–7892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This paper reviews how supramolecular analytical chemistry achieves molecular recognition through the dynamic exchange of synthetic chemical structures which create assemblies that result in signal modulations upon the addition of analytes for differential sensing applications.

- 41.Budde B, Schartner J, Tönges L, Kötting C, Nabers A, Gerwert K: Reversible immuno-infrared sensor for the detection of Alzheimer’s disease related biomarkers. ACS Sensors 2019, 4:1851–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pacheco JG, Silva MSV, Freitas M, Nouws HPA, Delerue-Matos C: Molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensor for the point-of-care detection of a breast cancer biomarker (CA 15–3). Sensors Actuators, B Chem 2018, 256:905–912. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dou Q, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Wang S, Hu D, Zhao Z, Liu H, Dai Q: Ultrasensitive Poly(boric acid) Hydrogel-Coated Quartz Crystal Microbalance Sensor by Using UV Pressing-Assisted Polymerization for Saliva Glucose Monitoring. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12:34190–34197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim H, Lee JU, Song S, Kim S, Sim SJ: A shape-code nanoplasmonic biosensor for multiplex detection of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Biosens Bioelectron 2018, 101:96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This paper demonstrates multi-target detection in a single assay using the differences in the plasmonic properties of various nanoshapes.

- 45.Xu S, Gao T, Feng X, Fan X, Liu G, Mao Y, Yu X, Lin J, Luo X: Near infrared fluorescent dual ligand functionalized Au NCs based multidimensional sensor array for pattern recognition of multiple proteins and serum discrimination. Biosens Bioelectron 2017, 97:203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rana L, Gupta R, Tomar M, Gupta V: Highly sensitive Love wave acoustic biosensor for uric acid. Sensors Actuators, B Chem 2018, 261:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arakawa T, Tomoto K, Nitta H, Toma K, Takeuchi S, Sekita T, Minakuchi S, Mitsubayashi K: A Wearable Cellulose Acetate-Coated Mouthguard Biosensor for in Vivo Salivary Glucose Measurement. Anal Chem 2020, 92:12201–12207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]