Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: betacoronavirus, health care workers, medical mask, N95 respirator

Abstract

Background:

There is no definite conclusion about comparison of better effectiveness between N95 respirators and medical masks in preventing health-care workers (HCWs) from respiratory infectious diseases, so that conflicting results and recommendations regarding the protective effects may cause difficulties for selection and compliance of respiratory personal protective equipment use for HCWs, especially facing with pandemics of corona virus disease 2019.

Methods:

We systematically searched MEDLINE, Embase, PubMed, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang, medRxiv, and Google Scholar from initiation to November 10, 2020 for randomized controlled trials, case-control studies, cohort studies, and cross-sectional studies that reported protective effects of masks or respirators for HCWs against respiratory infectious diseases. We gathered data and pooled differences in protective effects according to different types of masks, pathogens, occupations, concurrent measures, and clinical settings. The study protocol is registered with PROSPERO (registration number: 42020173279).

Results:

We identified 4165 articles, reviewed the full text of 66 articles selected by abstracts. Six randomized clinical trials and 26 observational studies were included finally. By 2 separate conventional meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials of common respiratory viruses and observational studies of pandemic H1N1, pooled effects show no significant difference between N95 respirators and medical masks against common respiratory viruses for laboratory-confirmed respiratory virus infection (risk ratio 0.99, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.86–1.13, I2 = 0.0%), clinical respiratory illness (risk ratio 0.89, 95% CI 0.45–1.09, I2 = 83.7%, P = .002), influenza-like illness (risk ratio 0.75, 95% CI 0.54–1.05, I2 = 0.0%), and pandemic H1N1 for laboratory-confirmed respiratory virus infection (odds ratio 0.92, 95% CI 0.49–1.70, I2 = 0.0%, P = .967). But by network meta-analysis, N95 respirators has a significantly stronger protection for HCWs from betacoronaviruses of severe acute respiratory syndrome, middle east respiratory syndrome, and corona virus disease 2019 (odds ratio 0.43, 95% CI 0.20–0.94).

Conclusions:

Our results provide moderate and very-low quality evidence of no significant difference between N95 respirators and medical masks for common respiratory viruses and pandemic H1N1, respectively. And we found low quality evidence that N95 respirators had a stronger protective effectiveness for HCWs against betacoronaviruses causative diseases compared to medical masks. The evidence of comparison between N95 respirators and medical masks for corona virus disease 2019 is open to question and needs further study.

Key Points

Question Whether N95 respirators have a stronger protection for health care workers against different kind of respiratory viruses in health-related settings compared to medical masks?

Findings In this systematic review and meta-analysis that included randomized clinical trials, no difference between N95 respirators and medical masks was found in the rate of infection of common respiratory viruses, but N95 respirators has a priority when facing with betacoronaviruses including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 according evidences from observational studies.

Meaning Considering the difference in cost and productivity capacity, and the increasing demand with COVID-19 worldwide, selection of use of N95 respirators with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 and medical masks with common respiratory virus is an acceptable option.

1. Introduction

Health-care workers (HCWs) are often exposed to infectious respiratory viruses transmitted by droplet, contact, or airborne mode in the medical workplace.[1] Although N95 respirators have been definitely proven to be more effective compared to medical masks in laboratory airborne and aerosols test where participants’ wearing compliance was nearly perfect,[2] it is still inconclusive the same is true of the medical environment in consideration of the greater discomfort and lower adherence associated with N95 respirator use.[3] After severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS),[4] middle east respiratory syndrome (MERS),[5] and pandemic H1N1 (pH1N1), corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which was caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, aroused attention on respiratory personal protective equipment (rPPE) again.[6]

Although World Health Organization guidelines recommend medical masks for all patient cares with the exception of N95 masks for aerosol-generating procedures, no high-quality evidence existed until 2019. A review exploring respiratory protection practices for prominent hazards in healthcare settings reported only 18% HCWs wearing a respirator for at least 1 hazard.[7] A systematic reviews and meta-analysis[8] suggested higher filtration efficiency of N95 respirators for aerosols and particles than medical mask in laboratory data. But both it and another subsequently published one[9] did not find significant different protective effects against respiratory viruses in clinical settings and put forward a strong possibility of no sufficient data to make a definite conclusion. Three randomized clinical trials (RCTs) included in mentioned meta-analyses presented insignificant superiority of N95 respirators against respiratory viruses with a broad confidence interval (CI) of the risk ratio (RR), which might mean their sample sizes were not adequate and result in the statistical underpower of conclusion of meta-analyses.[10–12] Another high quality conventional meta-analysis (CMA) revealed that face mask use could result in a large reduction in risk of infection, with stronger associations with N95 or similar respirators compared with disposable surgical masks or similar, but it did not directly compared N95 respirators with medical masks.[13] In recent years, several valued clinical trials[14–21] have investigated defending effects of different masks and respirators, making it possible to increase sample sizes and improve the statistical power of meta-analyses to reach a definite conclusion. And given that COVID-19 outbreaking worldwide now, scarcity of rPPE resources, and no authoritative guideline based on high-level evidence published, knowing appropriate selection of rPPE in different clinical setting against various microorganisms is vitally important.

We performed a systematic review and network meta-analysis (NMA) to assess and quantify protective effectiveness of N95 respirator vs medical mask against respiratory infectious viruses.

2. Methods

A detailed protocol was pre-specified, including search strategy, inclusion, exclusion, data extraction, quality assessment and bias evaluation, statistical analysis, and heterogeneity measurements (Document S1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD2/A335). This study is reported in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions,[22] Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis statement[23] and Extension Statement for Reporting Network Meta-Analyses.[24]

2.1. Search strategy

The search strategy includes MEDLINE, Embase, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang data, medRxiv, and Google Scholar from inception to November 10, 2020, with language limited to English and Chinese, for RCTs and observational studies that compared the effectiveness of rPPE. Full search terms and search strategy are provided in the Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD2/A330. Study types of RCT, case-control study, cohort study, and cross-sectional study are filtered manually. All mesh terms and text words are adjusted to corresponding database.

2.2. Study selection

Studies included in this study satisfies inclusion criteria as followings: Populations: HCWs. Exposure: rPPE, mainly including medical masks and N95 respirators. Comparison: HCWs with no rPPE or different rPPE. Outcome: the risk of clinical or laboratory-confirmed respiratory outcomes. Study design: clinical studies including RCT, case-control study, cohort study, and cross-sectional study. Setting: health-related settings including hospital, nursing home, outpatient department, emergency department, and etc.

We excluded studies if studies were editorials, guidelines, reviews, news articles, case series, and case reports. All populations in studies were patients or community populations. Studies did not definitely state which type of rPPE was being investigated or did not report events’ number of each type of rPPE.

Studies reporting on the same trial at 2 different timepoints of publication were regarded as a single trial. In addition, no studies were excluded because of high risk of bias.

RCTs and observational studies were included in 2 separate meta-analyses respectively and we would determine whether to use NMA depending on numbers of studies which did not directly compare effectiveness of N95 respirators with medical masks.

Two reviewers (Jiawen Li, Yu Qiu, and Yulin Zhang), independently and in duplicate, reviewed the titles and abstracts, and selected the studies. If 2 investigators could not resolve the disagreements through consensus, a third author (Yifei Li) would make a decision.

2.3. Data extraction and study quality assessment

Data was extracted using a pre-piloted standardized data-form through PROSPERO. The primary outcome variable in this study was the incidence of laboratory-confirmed respiratory virus infection (LCV). Secondary outcomes included incidence of clinical respiratory illness, and influenza-like illness.[18] Medical masks meet bacterial and particle filtration efficiency standards, but are not certifiable as N95 respirators, which have a filtration efficiency of at least 95% against non-oily particles. Disposable masks remove very small particles from the air you breathe in but do not meet the criteria of medical mask. These particles include mircoorganisms (like viruses, bacteria, and mold) and other kinds of dust. Because of different certification of masks and respirators under public health regulation in different countries and areas, we tacitly approve that the specific rPPE type reported in articles is quantified and equivalent. Surgical mask would be recognized equal to medical mask.

All of the included RCTs and observational studies are browsed in detail for methodology relevant to potential bias. Risk of bias in RCTs was assessed by Cochrane Risk of Bias tool.[25] Risk of bias in observational studies were evaluated by Newcastle-Ottawa scales.[26] Quality of evidence of CMA and NMA is assessed according to the grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation approach.[27,28]

A third author would make a judgement for the discrepancies in quality assessment where the consensus-forming discussions are difficult to make.

2.4. Meta-analysis and assessment of heterogeneity

All outcomes were analyzed on intention-to-treat basis unless missing population covered up more than 10% of total subjects. Cluster RCTs were adjusted for its design effect by the intraclass correlation coefficient.[29] The RR and odds ratio (OR) were selected as units of dichotomous data analysis. Summary measures were pooled by fixed-effects model unless otherwise specified.

We assessed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic and Q-test, and chose random-effects model for I2 >50% and heterogeneity P value <.05.

For NMA, we evaluated global inconsistency by fitting both a consistency and an inconsistency model,[30] and evaluated local inconsistency between direct and indirect estimates by using a node-splitting procedure.[31] We calculated the frequentist analogue of the surface under the cumulative ranking curve for each rPPE.[32]

All analyses were performed using the package Metan and Network Module in Stata statistical software (STATA, STATA15, StataCorp LLC, TX, USA) version 16.0 for Windows.

Unless otherwise specified, a two-sided P value of .05 or less was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

2.5. Publication bias

Publication bias was tested using funnel plots and the Egger test by STATA version 16.0. An asymmetric distribution of data points in the funnel plot and a quantified result of P < .05 in the Egger test indicated the presence of potential publication bias.[33]

2.6. Sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis

We performed sensitivity analysis by omitting 1 study at a time and examining the influence of each study on the pooled estimates of the primary outcome. Meanwhile, we used both random and fixed effects model to examine robustness of pooled outcome.

Pre-specified subgroup analyses included stratification by respiratory infectious diseases, study population, risk of bias, fit-testing, and other matching protective equipment if there were pooled effects with significant heterogeneity and including more than 5 studies.

3. Results

3.1. Studies included

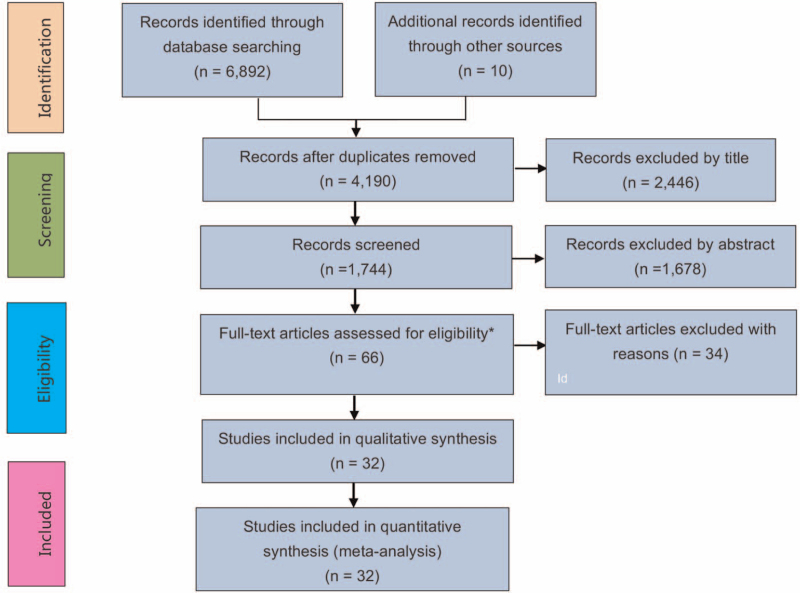

A total of 4165 publications were included for further screening and from these studies, by reviewing the abstract and content, we excluded 3299 irrelevant studies. The remaining 66 studies were reviewed in detail for inclusion and exclusion criteria and 32 met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). There was no discrepancy between reviewers in the studies screening process. This process yielded 6 RCTs and 26 observational studies. Two publications of RCTs[11,12] reported the same trial at 2 different follow-up time points. One RCT[34] was a published abridged format of another subsequent publication,[18] so we only preserved 2[11,18] of them for meta-analysis. The reasons why we excluded 19 observational studies were presented as followings: 7 studies were case series or case reports recognized by reading full texts[35–41]; 3 studies did not report sufficient data to make a 2 × 2 contingency tables (1 arm test or only reporting number of infected participants in each arm) about comparison of different masks, respirators, and control group without use or without continuous use of any type of rPPE[42–44]; 7 studies did not state clearly and definitely the type of rPPE used (e.g., only “facemask” or “mask” mentioned in articles)[45–50]; 5 studies were unable to extract a number of events and participants of each arm of rPPE or their ratio (OR or RR)[43,51–54]; individual patient data from the 32 studies including 6 RCTs and 26 observational studies were abstracted to make systemic reviews and meta-analyses, including trial characteristics, author, publication year, country, populations, interventions, outcomes, and limitations (Tables 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for study identification and selection.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the included RCTs.

| Study | Country | Setting | Intervention 1 | Intervention 2 | Intervention 3 | Study period | Sample size, n | Mena age, years | Women, (%) | Follow-up duration, days | Outcome | N95 fit-testing |

| Loeb (2009) | Canada | Emergency departments, medical units, and pediatric units | N95 respirator | Surgical mask | 9,2008–4,2009 | 422 | 36.1 | 94 | 97.5 | LCV, ILI, physician visits for respiratory illness | Yes | |

| MacIntyre (2011) | China | Emergency departments or respiratory wards | N95 respirator | Medical mask | Control group | 11,2008–1,2009 | 1922 | 33.6 | 90 | 15 | LCV, CRI, ILI, influenza | Yes |

| MacIntyre (2013) | China | Emergency departments or respiratory wards | N95 respirator | Medical mask | 12,2009–2,2010 | 1669 | 33.1 | 85 | 28 | LCV, CRI, ILI, bacteria | Yes | |

| MacIntyre (2015) | Vietnam | Wards in hospital | Medical mask | Cloth mask | Control group | 3,2011–2011,4 | 1607 | 36 | 79 | 29 | LCV, CRI, ILI | No |

| Radonovich (2019) | USA | Primary care facilities, dental clinics, adult and pediatric clinics, dialysis units, emergency departments, emergency transport services | N95 respirator | Medical mask | 9,2011–5,2015 | 5180 | 43 | 85 | 84 | LCV, CRI, ILI, laboratory-confirmed influenza | Yes |

CRI = clinical respiratory illness, ILI = influenza-like illness, LCV = laboratory-confirmed respiratory virus infection, RCTs = randomized clinical trials.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the included observational studies.

| Study | Design | Country | Study period | Outbreak | Setting | Intervention 1 | Intervention 2 | Intervention 3 | Sample size, n | Mean age, years | Women, (%) | Follow-up duration, days | Diagnostic criteria |

| Scale (2003) | CS | Canada | 3,2003 | SARS | ICU | N95 respirator | Medical mask | Control group | 27 | N/A | N/A | 3–8 | WHO's SARS clinical case definitions |

| Seto (2003) | CC | China | March 15–March 24, 2003 | SARS | Not negative-pressure rooms | N95 respirator | Medical mask | Control group, disposable mask | 254 | N/A | 69 | 7 | SARS Definition 1 |

| Ho (2004) | CS | Singapore | April 22–June 5, 2003 | SARS | General medical ward, isolation ward, emergency department and intensive-care unit | N95 respirator | Control group | No | 372 | 34.2 | 77.2 | 15–73 | Positive confirmatory result by both the indirect immunofluorescence assay and the virus neutralization assay |

| Loeb (2004) | CS | Canada | 3,2003–4,2003 | SARS | ICU, emergency room | N95 respirator | Medical mask | Control group | 29 | 41 | 100 | 10 | WHO's SARS clinical case definitions |

| Lau (2004) | CC | China | 3,2003–5,2003 | SARS | SARS inpatient ward | N95 respirator | Medical mask | Control group | 215 | N/A | N/A | 21 | WHO's SARS clinical case definitions |

| Park (2004) | CS | USA | March 15–June 23, 2003 | SARS | Medical ward and emergency department | N95 respirator | Control group | No | 110 | 41 | 75 | 22–28 | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and indirect fluorescent antibody test |

| Peck (2004) | CS | USA | April 14, 2003–? | SARS | Emergency department, airborne-infection (negative-pressure) isolation room | N95 respirator | Control group | No | 41 | 35 | 78.1 | 22+ | Total anti-SARS-CoV serum antibody ELISA and indirect fluorescent antibody test. RT-PCR on nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs and stool and urine specimens |

| Teleman (2004) | CC | Singapore | March 1–30, 2003 | SARS | The national treatment and isolation facility | N95 respirator | Control group | No | 86 | N/A | 94 | N/A | WHO's SARS clinical case definitions |

| Yin (2004) | CC | China | 4,2003–5,2003 | SARS | SARS inpatient ward | Medical mask | Paper mask | Control group | 213 | N/A | 74 | 60+ | N/A |

| Nishiura (2005) | CC | China | 2,2003–4,2003 | SARS | N/A | Medical mask | Control group | No | 145 | N/A | 60 | N/A | Indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| Wild-Smith (2005) | CS | Singapore | March 1–22, 2003 | SARS | SARS inpatient ward | N95 respirator | Control group | No | 89 | 31.6 | 90.6 | N/A | SARS serology (including asymptomatic SARS) |

| Pei (2006) | CC | China | April–June 2004 | SARS | N/A | Cotton mask | Control group | No | 443 | N/A | 77.7 | N/A | WHO's SARS clinical case definitions and SARS-CoV IgG antibody positive in convalescence serum |

| Liu (2009) | CC | China | March 5– May 17, 2003 | SARS | Medical ward, emergency department, outpatient clinic, other location | N95 respirator | Medical mask | No | 477 | 30.8 | 68.3 | June–July 2003 | WHO's SARS clinical case definitions or laboratory confirmation by 1 or more of the following: RT-PCR; culture from throat wash, urine |

| Alraddadi (2016) | CS | Saudi Arabia | May–June 2014 | MERS | Medical intensive care unit and emergency department | N95 respirator | Medical mask | Control group | 250 | 37.2 | 64.4 | Several weeks | A modified version of the HKU5.2 N ELISA |

| Hall (2014) | CS | Saudi Arabia | 6,2012–10,2012 | MERS | N/A | N95 respirator | Medical mask | No | 48 | 30.5 | 60 | 20 | HKU5.2N screening EIA results and confirmed by MERS-CoV immunofluorescence or micro neutralization assay |

| Kim (2016) | CS | South Korea | May 26– June 3, 2015 | MERS | Emergency department | N95 respirator | Medical mask | Control group | 9 | N/A | N/A | 14 | Optical density (OD) values were at or above a 0.28 of MERS CoV-specific IgG with a recombinant nucleocapsid-based ELISA |

| Park (2016) | CC | South Korea | May–June, 2015 | MERS | Hospital isolation or home isolation | Medical mask | Control group | No | 40 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Burke (2020) | CS | USA | January–February 2020 | COVID-19 | Healthcare setting | N95 respirator | Medical mask | Control group | 338 | N/A | 53 | 14 | All 3 separate genetic markers of SARS-CoV-2 in the N1, N2, and N3 regions were positive by rRT-PCR |

| Wang X (2020) | CS | China | January 2– January 22, 2020 | COVID-19 | Respiratory, ICU, infectious disease, hepatobiliary pancreatic surgery, trauma and microsurgery, urology | N95 respirator | Control group | No | 493 | 32.1 | 68.3 | 20 | Chest CT and molecular diagnosis |

| Wang Q (2020) | CS | China | ?– March 1, 2020 | COVID-19 | Neurosurgery departments | N95 respirator | Medical mask | No | 5442 | 60.6 | 50 | N/A | Positive nucleic acid test result on real-time RT-PCR assay of nasal and pharyngeal swab specimens |

| Cheng (2010) | CC | China | 5,2009–8,2009 | H1N1 | Adult pediatric isolation ward | Medical mask | Control group | No | 836 | 29 | 53.7 | 100 | RT-PCR |

| Zhang (2013) | CC | China | 8,2009–1,2010 | H1N1 | High-risk setting of respiratory illness | N95 respirator | Medical mask | Control group, cloth mask | 255 | N/A | 82 | N/A | RT-PCR |

| Chokephaibulkit (2016) | CR | Thailand | 6,2009–8,2009 | H1N1 | Specific wards, isolation wards, semi-open wards, emergency room | N95 respirator | Medical mask | No | 220 | 34 | 93 | 60+ | HI titer >40 |

| Toyokawa (2011) | CR | Japan | 6,2009–7,2009 | H1N1 | Emergency department or wards | N95 respirator | Medical mask | No | 221 | 32 | 73.9 | N/A | RT-PCR |

| Yang (2011) | CR | China | 4,2008–5,2008 | Respiratory infection | Respiratory, emergency, infectious disease, and surgical departments | Medical mask | Cotton mask | No | 400 | 35 | 81 | N/A | Respiratory infection definition |

| Al-Asmary (2007) | CC | Saudi Arabia | 2005 Hajj period | ARTI | Military hospitals | Medical mask | Control group | No | 250 | 37 | 32 | 14 | ARTI definition |

Control group: HCWs group without any consistent use of mask or respirator

SARS definition∗: fever of 38 °C or higher, radiological infiltrates compatible with pneumonia, and 2 of: chills, new cough, malaise, and signs of consolidation. We excluded patients who had known pathogens, radiological evidence of lobar consolidation, or who responded to antibiotics within 48 hours.

ARTI definition∗: at least 1 constitutional symptom (fever, headache, and myalgia) plus at least 1 of the following local symptoms (coryza, sneezing, throat pain, cough with/ without sputum, and difficulty breathing).

Respiratory infection definition∗: defined as having at least 2 of the following symptoms simultaneously: fever, cough, sore throat, nasal congestion, or rhinorrhea.

ARTI = acute respiratory tract infection, CC = case-control study, COVID-19 = corona virus disease 2019, CR = cross-sectional study, CS = cohort study, ELISA = enzyme-linked immuno sorbent assay, HCWs = health-care workers, ICU = intensive care unit, MERS = middle east respiratory syndrome, RT-PCR = real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction, SARS = severe acute respiratory syndrome, SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

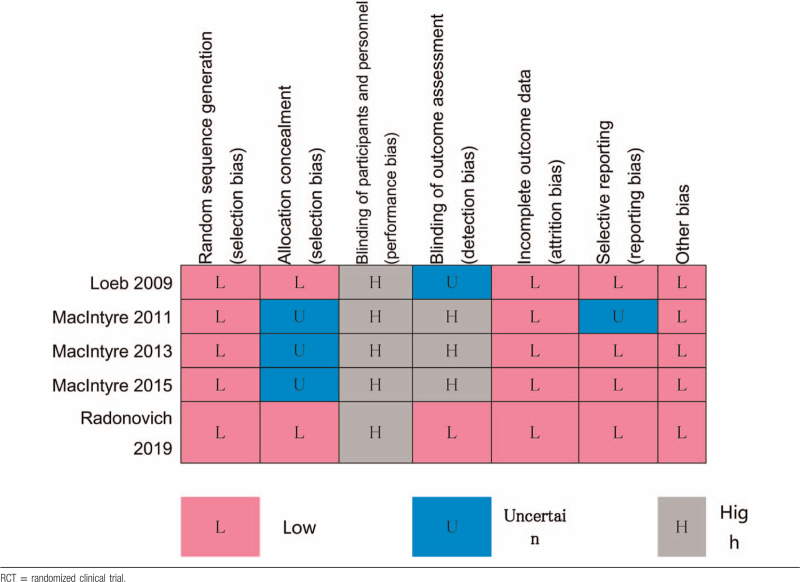

3.2. Risk of bias

The risk of bias for the RCTs are summarized in Table 3. The domain of blinding of participants and personnel are rated as high risk of bias because it is impossible to avoid recognizing the type of rPPE for both subjects and researchers. The risk of bias for observational studies is summarized in Table 4 by Newcastle-Ottawa scales.

Table 3.

Cochrane risk of bias tool risk of bias for each included RCT.

Table 4.

Newcastle-Ottawa scale summary of risk of bias for cohort and case-control studies.

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Exposure/Outcome | Overall rating | |||||

| Cohort | |||||||||

| Alraddadi (2016) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 8 | |

| Scale (2003) | ∗ | ∗ | 2 | ||||||

| Ho (2004) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 8 | |

| Loeb (2004) | ∗ | ∗ | 2 | ||||||

| Peck (2004) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 9 |

| Park (2004) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 3 | |||||

| Wilder-Smith (2005) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 8 | |

| Hall (2014) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 3 | |||||

| Kim (2016) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 6 | ||

| Burke (2020) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 4 | ||||

| Wang X (2020) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 5 | |||

| Wang Q (2020) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 5 | |||

| Case-control | |||||||||

| Seto (2003) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 7 | ||

| Lau (2004) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗∗ | ∗ | 6 | |||

| Liu (2009) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 5 | |||

| Park (2016) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 3 | |||||

| Pei (2006) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 8 | |

| Teleman (2004) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗∗ | ∗ | 6 | |||

| Yin (2004) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 6 | |||

| Nishiura (2005) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 4 | ||||

| Cheng (2010) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 3 | |||||

| Zhang (2013) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗∗ | ∗ | 5 | ||||

| Al-Asmary (2007) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | 3 | |||||

3.3. Common respiratory viruses

Common respiratory viruses include influenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza viruses, and respiratory adenoviruses. Six RCTs[3,10,11,18,55,56] including 8333 health-related workers (median 1064 HCWs, range 32–2668 HCWs, interquartile range [IQR] 43–1669) reported on common respiratory viruses. Across the included trials, the median age of HCWs was 36 years (range 33.1–43.0, IQR 33.6–36.1). Women accounted for 84% (range 72%–94%, IQR 79%–90%). The median follow-up duration across studies was 55 days (range 15–97.5 days, IQR 28–84 days) in HCWs. From comparative studies between medical masks and N95 respirators for HCWs, we obtained data for 3944 (45.3%) participants of whom had been assigned to receive medical masks and 4768 (54.7%) to receive N95 respirators.

Four RCTs[3,10,11,18] directly compared respiratory infection risk in HCWs wearing N95 respirators vs medical masks. Three clusters of RCTs[3,11,18] provided design effect and we adjusted them with individual RCTs for meta-analysis. No study reported missing data of more than 10% included participants so we extracted data from RCTs by intention-to-treat analysis. Definitions of LCV included serology[10,18] and polymerase chain reaction,[3,10,11,18] and serological criteria of infection were not suitable for participants having received vaccine.

No significant difference was detected between HCWs using N95 respirators and those using medical masks in risk of LCV (fixed-model RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.86–1.13, I2 = 0.0%, P = .638), clinical respiratory illness (random-model RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.45–1.09, I2 = 83.7%, P = .002), and influenza-like illness (fixed model RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.54–1.05, I2 = 0.0%) (Fig. 2). Although 1 RCT[18] in 2019 took up a high proportion of pooled effect, as a high-quality large-scale multicenter RCT, it made no harm to the credibility of the prior conclusion in our view.

Figure 2.

Pooled difference of effectiveness of N95 respirators vs surgical masks in protecting health care workers against respiratory infection. The figure showed event and total number of 3 outcome of included studies. Outcomes were (A) laboratory-confirmed respiratory virus infection, (B) clinical respiratory illness, and (C) influenza-like illness. Values less than 1.0 favor N95 respirator. CI = confidence interval, CRI = clinical respiratory illness, D+L = Dersimonian-Laird method of random effects model, ILI = influenza-like illness, LCV = laboratory-confirmed respiratory virus infection, M-H = Mantel-Haenszel method of fixed effects model, MED = medical mask group, N95 = N95 respirator group, RR = risk ratio.

MacIntyre et al[11,56] reported comparative analysis including cloth mask or control group and no protective effectiveness of cloth mask was found. Another RCT[55] did not report the primary and secondary outcomes mentioned above.

We did not conduct subgroup analyses because no heterogeneity of LCV (I2 = 0.0%, P value for Q-test = .638) was detected. Fixed and random effect model come to the same conclusion except for fixed effect model of clinical respiratory illness (I2 = 83.7%, P value for Q-test = .002) because large difference of effect size of 2 RCTs by MacIntyre et al[3] and Radonovich[18] (Fig. 2). No meaningful publication bias and sensitivity analysis could be performed because too few RCTs were included.

In addition, 1 cohort study[57] reported that compared to HCWs who did not wear a medical mask or had poor adherence, HCWs with medical mask and better adherence had a lower rate of respiratory infection. Another case-control study[58] in Saudi Arabia suggested surgical facemasks to protect pilgrims and medical personnel should be discontinued.

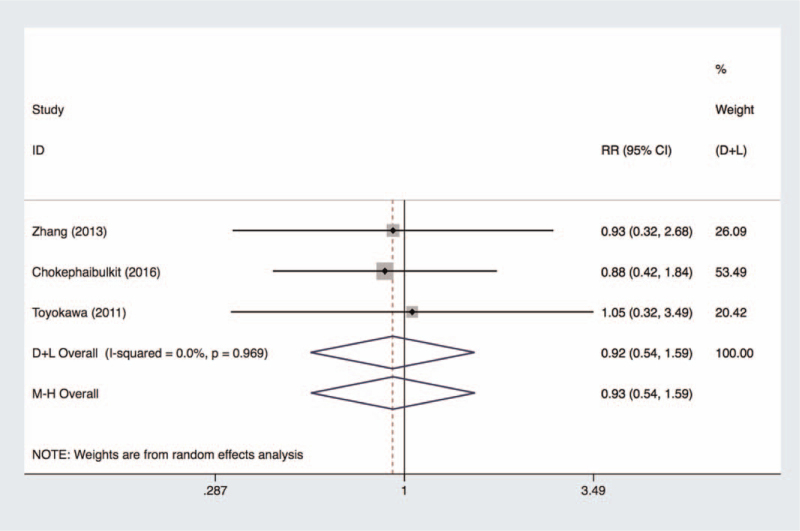

3.3.1. Pandemic H1N1 influenza

Pooled effects of 3 observational studies[59–61] (1488 patients) reported there was no significant difference between N95 respirators and medical masks in protecting HCWs from pH1N1 infection (fixed model, OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.54–1.59, I2 = 0.0%, P = .969) (Fig. 3). Another study[62] reported significant protective effectiveness of medical mask compared to control group without any rPPE. In view of a small number of included studies, we did not make further detection of publication bias.

Figure 3.

Pooled difference of effectiveness of N95 respirators vs surgical masks in protecting health care workers against pH1N1. CI = confidence interval, D+L = Dersimonian-Laird method of random effects model, M-H = Mantel-Haenszel method of fixed effects model, pH1N1 = pandemic H1N1, RR = risk ratio.

3.3.2. Betacoronaviruses

Pandemic and epidemic betacoronaviruses include SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV 2. Of the 24 eligible observational studies related to betacoronaviruses, 13 compared protective effectiveness of rPPE against SARS, including 6 cohort studies[41,63–67] and 7 case-control studies[43,68–73]; 4 against MERS, including 3 cohort studies[74–76] and 1 case-control study[77]; 3 cohort studies against COVID-19,[15,78,79] 4 studies against pH1N1, including 1 cohort studies,[62] 1 case-control studies[61] and 2 cross-sectional studies.[59,60] Trial sample size ranged from 9 to 5442 patients.

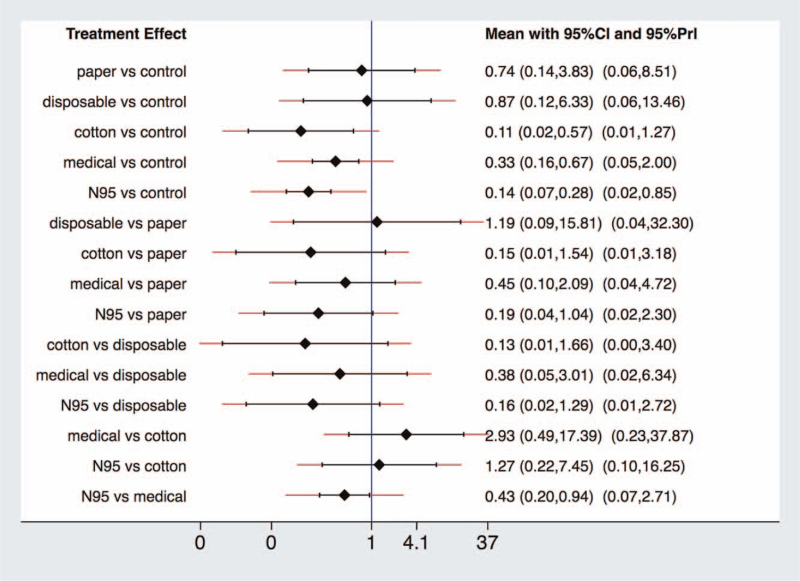

We pooled effects of different rPPE by NMA (Fig. 4) and data for NMA was showed in Table S2, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD2/A331. Fitness between consistency and inconsistency models, node-splitting procedure, looper-specific inconsistency estimates showed there is no significant global (chi2(6) = 7.53, P = .2750), local (Table S3, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD2/A332) and loop (Figure S1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD2/A333) inconsistency. The results provide evidence (Fig. 5) that there is a significant priority of N95 respirators for HCWs to prevent nosocomial infections of coronavirus causative SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 compared to medical masks (OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.20–0.94), but wide prediction interval (95% prediction interval 0.07–2.71) cross null value (1.0) reminded us of potential heterogeneity of included studies referred to N95 respirator vs medical mask. Both of them significantly bring down the secondary attack rate compared with a control group without continuous or any use of rPPE (N95 vs control, OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.07–0.28; medical vs control, OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.16–0.67). Except HCWs without any rPPE, control groups also include convenience samples of inconsistent use of rPPE or following routine infection control policies, which will mitigate the statistical difference. Although not pointing out a specific type of mask, 1 COVID-19 related study reported facemask use, especially N95 respirators or higher level rPPE, can help minimize unprotected, high-risk HCWs exposures and protect the health care workforce.[50]

Figure 4.

The network of comparisons included in the study for overall response. The line width is proportional to the number of trials performed to compare between 2 types of rPPE. rPPE = respiratory personal protective equipment.

Figure 5.

Interval plot. The summary effect estimates (OR) of SARS for each combination of intervention. The red lines show prediction interval of future research. CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio, PrI = prediction interval.

The analyses of paper, disposable, and cotton masks are not valuable because of a limited number of involved studies and participants. The surface under the cumulative ranking curve statistic showed that N95 respirator ranked first, followed by medical mask and control group (Figure S2, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD2/A334).

We adjusted the NMA by covariate of type of betacoronavirus to analyze the heterogeneity. N95 respirators still provide stronger protection than the medical masks (adjust OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.13–0.97).

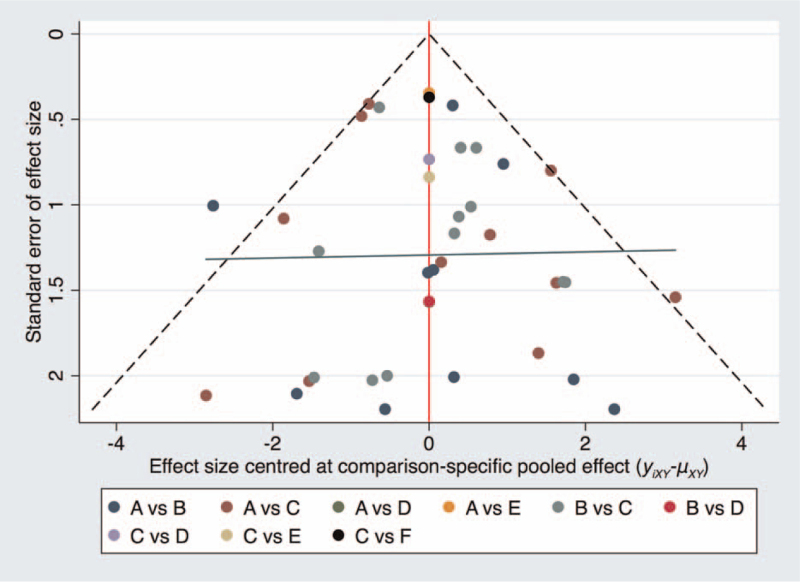

The evaluation of publication bias was performed virtually using a network funnel plot for OR (Fig. 6). As shown in Figure 6, all the included studies were approximately symmetrically distributed around the vertical line, indicating that no significant publication bias or small sample effect exists in this network analysis.

Figure 6.

Comparison-adjusted funnel plot for ORs of SARS. A = medical mask, B = N95 respirator, C = control group, D = disposable mask, E = paper mask, F = cotton mask, SARS = severe acute respiratory syndrome, OR = odds ratio.

3.4. Assessment of quality of evidence

For the pooled effect of CMA of common respiratory viruses of RCTs, and pH1N1 of observational studies, the ratings of importance and quality of evidence which we assessed using the GRADE approach[27] are summarized in Table 5. We did not provide judgment of overall assessment because of impossible blindness of rPPE types for participants and collectors. Cluster-adjusted effective sample sizes and event numbers, and no blinding of researchers, participants, and data collectors increase the risk of bias. No detection of publication bias is made because of a limited number of included studies for each evidence of CMA. Wide CIs and limited number of participants contribute imprecision of evidence.

Table 5.

GRADE quality of evidence summary of conventional MA.

| Quality assessment | No of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

| No of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | N95 respirator | Medical mask | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Laboratory-confirmed respiratory virus infection (follow-up mean 56 days; assessed with: PCR or serological method) | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomized trials | Serious∗,†,‡ | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Serious§ | Strong association | 325/2354 (13.8%) | 332/1871 (17.7%) | RR 0.986 (0.863 to 1.127) | 2 fewer per 1000 (from 24 fewer to 23 more) | □ □ □ □ MODERATE | CRITICAL |

| Clinical respiratory illness (follow-up mean 42 days; assessed with: 2 or more respiratory symptoms, or 1 respiratory symptom and a systemic symptom) | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Randomized trials | Serious∗,†,‡ | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Serious§ | None | 703/2144 (32.8%) | 784/1659 (47.3%) | RR 0.697 (0.446 to 1.088) | 143 fewer per 1000 (from 262 fewer to 42 more) | □ □ □ □ LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Influenza-like illness (follow-up mean 56 days; assessed with: fever ≥38°C and 1 respiratory symptom) | ||||||||||||

| 5 | Randomized trials | Serious∗,†,‡ | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Serious§ | Strong association | 59/2354 (2.5%) | 79/1872 (4.2%) | RR 0.753 (0.541 to 1.046) | 10 fewer per 1000 (from 19 fewer to 2 more) | □ □ □ □ MODERATE | IMPORTANT |

| pH1N1 (follow-up mean 83 days; assessed with: RT-PCR or serology) | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Observational studies | Very serious‡,|| | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Serious§,¶ | None | 26/296 (8.8%) | 14.8% | OR 0.92 (0.49 to 1.70) | 10 fewer per 1000 (from 70 fewer to 80 more) | □ □ □ □ VERY LOW | CRITICAL |

CI = confidence interval, GRADE = grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation approach, OR = odds ratio, pH1N1 = pandemic H1N1, rPPE = respiratory personal protective equipment, RT-PCR = real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction, RR = risk ratio.

Cluster-adjusted effective events and sample sizes.

All studies unblinded to participants and personnel.

Subtle differences of confounders may have existed among the studies, which were not reported, including details of rPPE adherence, fit-testing, continuous adjustments and inappropriate wearing, influenza vaccine, concurrent interventions (e.g., gloves, gowns, safety goggles, and hand hygiene practices), and contamination of provided rPPE during storage and reuse.

Wide confidence interval including null value.

No testing for exposure prior to study.

Limited number of events and insufficient participant numbers to detect a potential difference.

For NMA's pooled effects of betacoronaviruses of observational studies, the evidence is assessed in Table 6 according to network GRADE method.[28] Quality of evidence for indirect estimate rated down for serious imprecision and risk of bias.

Table 6.

Direct, indirect and network meta-analysis estimates of the odds ratios of the effects of different rPPE comparisons.

| Number of included studies | Direct estimate (95%) conventional MA | Direct estimate (95% CI) from node splitting | Quality | Indirect estimate (95% CI) | Quality§ | NMA estimate (95%) | Quality|| |

| 20 | 0.21 (0.12, 0.38) | 0.39 (0.15, 0.99) | Low∗ | 0.59 (0.12, 2.85) | Low† | 0.43 (0.20, 0.94) | Low‡ |

CI = confidence interval, NMA = network meta-analysis, rPPE = respiratory personal protective equipment.

Quality of evidence for direct estimate rated down by 1 level for serious risk of bias.

Quality of evidence for direct estimate rated down by 1 level for serious imprecision.

Quality of evidence for network estimate rated down by 1 level for serious incoherence.

We did not downgrade for intransitivity in any of the indirect comparisons.

All quality of evidence rated up by 1 level for large sample effect.

The ratings of evidence quality of common respiratory viruses of RCTs, pH1N1, and betacoronaviruses of observational studies are moderate, very low, and low, respectively.

4. Discussion

The systematic reviews and meta-analyses are the latest update of rPPE against respiratory viruses and the first NMA of rPPE. It provides important insight into an area of medical practice that is large in scope and far-reaching. Many HCWs are exposed to patients with respiratory infectious diseases, especially COVID-19 now. Given the current interest in a more mindful approach to the use of medical resources and cost containment, understanding whether the use of N95 respirators vs medical masks affect attack rates is important because of the large difference of cost and production capacity between N95 respirators and medical masks.

In CMA of common respiratory viruses, and pH1N1, compared to medical masks, N95 respirators did not provide significantly greater protection with moderate and low-quality evidence, respectively. MacIntyre et al[3,11] reported a superior protective effect of N95 respirators against influenza and other lower incidence outcomes, which was different from the outcome of the other 2 large-scale RCTs.[10,18] Although the evidence from CMA of RCTs is only evaluated as moderate by GRADE approach, 1 included large-scale and multicenter RCT by Radonovich et al[18] reported the same outcome as our CMA, and provided high-quality evidence with scientific and strict clinical trial design and sufficient power.

In NMA of betacoronaviruses, pooled effects provide low-quality evidence of better protective effectiveness of N95 respirators vs medical masks against SARS, MERS, and COVID-19. We also find significantly greater protectiveness of both N95 respirators and medical masks compared to HCWs without consistent use of rPPE.

All of a meta-analysis[8] and six experimental researches[19,20,80–83] published in recent years reported N95 respirators had less filter penetration, less face-seal leakage, and less total inward leakage, compared with medical masks, under the laboratory experimental conditions, which partly explains the reasons of the priority of N95 respirators for betacoronaviruses. Conflicting outcomes of common viruses, pH1N1, and betacoronaviruses of SARS, MERS, and COVID-19, maybe due to different mode of transmission (e.g., whether to spread through aerosols or respiratory droplets) and better compliance for fatal SARS, MERS, and COVID-19, which also meant less face contamination from improper wearing or adjustment of N95 respirators.

Some studies have reported that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 had a household second attack rate between 3% to 10%[84] and reproduction number (R0) range from 2.0 to 2.7,[85] which means its transmission mode was droplet or contact mode rather than airborne transmission.[85,86] Therefore, N95 respirators and other particle filters did not work better than medical masks when facing with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 except for aerosols-generating procedures. However, America's Centres for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the use of respirators where available even for care that does not include aerosols-generating procedures.[87]

Subtle differences and confounders may have existed among the studies analyzed, including details of rPPE adherence, fit-testing, different levels of exposure, continuous adjustments and inappropriate wearing, influenza vaccine, concurrent interventions (e.g., gloves, gowns, safety goggles, and hand hygiene practices), and contamination of provided rPPE during storage and reuse. However, given the consistency of conclusions and low heterogeneity found in the included studies, we did not think that these potential differences affected the outcomes of our meta-analyses or the power of the overall assessment. The specific jobs and clinical departments of HCWs were mentioned by most of included studies, but nearly no individual studies provided sufficient information for a more detailed analysis.

This study has limitations as follows. None of the studies included in the meta-analysis, except 2 RCTs[10,18] published in JAMA, independently audited compliance with the intervention. Intention-to-treat analyses in non-inferiority trials may be biased toward finding no difference and only 2 RCTs[10,18] also conducted an analysis of LCV by per-protocol analysis, which made the same conclusions as to their corresponding intention-to-treat analyses. It is inevitable for HCWs to contact pathogens from community exposures without rPPE. Some included studies’ control group consisted of HCWs following routine policies or wearing rPPE discontinuously, which would underestimate rPPE's effects. Part of asymptomatic carriers have a relatively high false negative rate of the serological tests. It is impossible to avoid bias due to lack of blinding of participants, which contributed to relatively low-GRADE quality assessment. Brands, models, or even the generic type of mask used, were often omitted. The number of studies included in the meta-analysis is limited.

5. Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis showed that N95 respirators are not superior to medical masks in protecting HCWs against common respiratory viruses in clinical settings. But N95 respirators provided significantly stronger protection against betacoroviruses of SARS, MERS, and COVID-19. We recommend HCWs wear N95 respirators in the high-risk areas of betacoronaviruses and medical masks in low-risk areas. In consideration of medical ethics, it is impossible to conduct RCTs of betacoronaviruses for rPPE, more high-quality observational studies with sufficient data are needed to detect a potentially clinically important difference of N95 respirators vs medical masks for COVID-19. Given the high cost and low production capacity of N95 respirators and COVID-19 outbreaking worldwide, these findings could have a significant effect on and implications for current practice standards.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Kaiyu Zhou, Yimin Hua, Yifei Li.

Data curation: Jiawen Li, Yunru He, Peng Yue, Xiaolan Zheng, Lei Liu, Hongyu Liao, Yifei Li.

Formal analysis: Jiawen Li, Yu Qiu, Yulin Zhang, Yunru He, Kaiyu Zhou, Yifei Li.

Funding acquisition: Yimin Hua.

Investigation: Jiawen Li, Yu Qiu, Yulin Zhang, Xue Gong, Yunru He, Kaiyu Zhou, Yifei Li.

Methodology: Jiawen Li, Yu Qiu, Yulin Zhang.

Project administration: Kaiyu Zhou, Yimin Hua, Yifei Li.

Resources: Yulin Zhang, Xue Gong.

Software: Yulin Zhang, Xue Gong, Yifei Li.

Supervision: Kaiyu Zhou, Yimin Hua, Yifei Li.

Validation: Jiawen Li, Yu Qiu, Kaiyu Zhou, Yifei Li.

Visualization: Jiawen Li, Yifei Li.

Writing – original draft: Jiawen Li, Yifei Li.

Writing – review & editing: Kaiyu Zhou, Yimin Hua, Yifei Li.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, CMA = conventional meta-analysis, COVID-19 = corona virus disease 2019, HCWs = health-care workers, IQR = interquartile range, LCV = laboratory-confirmed respiratory virus infection, MERS = middle east respiratory syndrome, NMA = network meta-analysis, OR = odds ratio, pH1N1 = pandemic H1N1, RCTs = randomized clinical trials, rPPE = respiratory personal protective equipment, RR = risk ratio, SARS = severe acute respiratory syndrome.

How to cite this article: Li J, Qiu Y, Zhang Y, Gong X, He Y, Yue P, Zheng X, Liu L, Liao H, Zhou K, Hua Y, Li Y. Protective efficient comparisons among all kinds of respirators and masks for health-care workers against respiratory viruses: a PRISMA-compliant network meta-analysis. Medicine. 2021;100:34(e27026).

JL and YQ contributed equally to this work.

All phase of this study was supported by a National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC1002301). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

IRB approval is not applicable as this is a meta-analysis without any participants involved.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Website (www.md-journal.com).

References

- [1].World Health Organization. Infection prevention and control of epidemic and pandemic-prone acute respiratory infections in health care. 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Noti JD, Lindsley WG, Blachere FM, et al. Detection of infectious influenza virus in cough aerosols generated in a simulated patient examination room. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54:1569–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].MacIntyre CR, Wang Q, Seale H, et al. A randomized clinical trial of three options for N95 respirators and medical masks in health workers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:960–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Peiris JS, Guan Y, Yuen KY. Severe acute respiratory syndrome. Nat Med 2004;10: (Suppl 12): S88–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cheng VC, Lau SK, Woo PC, Yuen KY. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus as an agent of emerging and reemerging infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007;20:660–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Du Z, Wang L, Cauchemez S, et al. Risk for transportation of 2019 novel coronavirus disease from Wuhan to other cities in China. Emerg Infect Dis 2020;26:1049–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wizner K, Nasarwanji M, Fisher E, Steege AL, Boiano JM. Exploring respiratory protection practices for prominent hazards in healthcare settings. J Occup Environ Hyg 2018;15:588–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Smith JD, MacDougall CC, Johnstone J, Copes RA, Schwartz B, Garber GE. Effectiveness of N95 respirators versus surgical masks in protecting health care workers from acute respiratory infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2016;188:567–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Offeddu V, Yung CF, Low MSF, Tam CC. Effectiveness of masks and respirators against respiratory infections in healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:1934–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Loeb M, Dafoe N, Mahony J, et al. Surgical mask vs N95 respirator for preventing influenza among health care workers: a randomized trial. JAMA 2009;302:1865–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].MacIntyre CR, Wang Q, Cauchemez S, et al. A cluster randomized clinical trial comparing fit-tested and non-fit-tested N95 respirators to medical masks to prevent respiratory virus infection in health care workers. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2011;5:170–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].MacIntyre CR, Wang Q, Rahman B, et al. Efficacy of face masks and respirators in preventing upper respiratory tract bacterial colonization and co-infection in hospital healthcare workers. Prev Med 2014;62:01–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet (London, England) 2020;395:1973–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Glatt AE. Health care worker use of N95 respirators vs medical masks did not differ for workplace-acquired influenza. Ann Intern Med 2020;172:JC7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wang X, Pan Z, Cheng Z. Association between 2019-nCoV transmission and N95 respirator use. J Hosp Infect 2020;105:104–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chen X, Chughtai AA, MacIntyre CR. Herd protection effect of N95 respirators in healthcare workers. J Int Med Res 2017;45:1760–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].MacIntyre CR, Chughtai AA, Rahman B, et al. The efficacy of medical masks and respirators against respiratory infection in healthcare workers. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2017;11:511–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Radonovich LJ, Jr, Simberkoff MS, Bessesen MT, et al. N95 respirators vs medical masks for preventing influenza among health care personnel: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;322:824–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Blachere FM, Lindsley WG, McMillen CM, et al. Assessment of influenza virus exposure and recovery from contaminated surgical masks and N95 respirators. J Virol Methods 2018;260:98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Elmashae RBY, Grinshpun SA, Reponen T, Yermakov M, Riddle R. Performance of two respiratory protective devices used by home-attending health care workers (a pilot study). J Occup Environ Hyg 2017;14:D145–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Talbot TR, Babcock HM. Respiratory protection of health care personnel to prevent respiratory viral transmission. JAMA 2019;322:817–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].2019;Higgins JPT, Thomas J. Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 2010;8:336–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:777–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 6). 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schunemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:380–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Puhan MA, Schünemann HJ, Murad MH, et al. A GRADE Working Group approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from network meta-analysis. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 2014;349:g5630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Killip S, Mahfoud Z, Pearce K. What is an intracluster correlation coefficient? Crucial concepts for primary care researchers. Ann Fam Med 2004;2:204–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].White IR, Barrett JK, Jackson D, Higgins JP. Consistency and inconsistency in network meta-analysis: model estimation using multivariate meta-regression. Res Synth Methods 2012;3:111–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dias S, Welton NJ, Caldwell DM, Ades AE. Checking consistency in mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. Stat Med 2010;29:932–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:163–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Deeks JJ, Macaskill P, Irwig L. The performance of tests of publication bias and other sample size effects in systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy was assessed. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:882–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Radonovich LJ, Jr, Bessesen MT, Cummings DA, et al. The Respiratory Protection Effectiveness Clinical Trial (ResPECT): a cluster-randomized comparison of respirator and medical mask effectiveness against respiratory infections in healthcare personnel. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16:243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wise ME, De Perio M, Halpin J, et al. Transmission of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza to healthcare personnel in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52: (Suppl 1): S198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Tambyah PA. Severe acute respiratory syndrome from the trenches, at a Singapore university hospital. Lancet Infect Dis 2004;4:690–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Twu SJ, Chen TJ, Chen CJ, et al. Control measures for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis 2003;9:718–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Dwosh HA, Hong HH, Austgarden D, Herman S, Schabas R. Identification and containment of an outbreak of SARS in a community hospital. CMAJ 2003;168:1415–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ofner M, Lem M, Sarwal S, Vearncombe M, Simor A. Cluster of severe acute respiratory syndrome cases among protected health care workers-Toronto, April 2003. Can Commun Dis Rep 2003;29:93–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ofner-Agostini M, Gravel D, McDonald LC, et al. Cluster of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome among Toronto healthcare workers after implementation of infection control precautions: a case series. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2006;27:473–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Park BJ, Peck AJ, Kuehnert MJ, et al. Lack of SARS transmission among healthcare workers, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2004;10:244–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chen WQ, Ling WH, Lu CY, et al. Which preventive measures might protect health care workers from SARS? BMC Public Health 2009;9:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ma HJ, Wang HW, Fang LQ, et al. A case-control study on the risk factors of severe acute respiratory syndromes among health care workers. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2004;25:741–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Nishiyama A, Wakasugi N, Kirikae T, et al. Risk factors for SARS infection within hospitals in Hanoi, Vietnam. Jpn J Infect Dis 2008;61:388–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Chen YC, Chen PJ, Chang SC, et al. Infection control and SARS transmission among healthcare workers, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis 2004;10:895–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Deng Y, Zhang Y, Wang XL, et al. Pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection factors among healthcare workers - a case-control study. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2010;44:1075–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Jaeger JL, Patel M, Dharan N, et al. Transmission of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus among healthcare personnel-Southern California, 2009. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011;32:1149–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ng TC, Lee N, Hui SC, Lai R, Ip M. Preventing healthcare workers from acquiring influenza. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009;30:292–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Reynolds MG, Anh BH, Thu VH, et al. Factors associated with nosocomial SARS-CoV transmission among healthcare workers in Hanoi, Vietnam, 2003. BMC Public Health 2006;6:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Heinzerling A, Stuckey MJ, Scheuer T, et al. Transmission of COVID-19 to health care personnel during exposures to a hospitalized patient - Solano County, California, February 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:472–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Ki HK, Han SK, Son JS, Park SO. Risk of transmission via medical employees and importance of routine infection-prevention policy in a nosocomial outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS): a descriptive analysis from a tertiary care hospital in South Korea. BMC Pulm Med 2019;30:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kim CJ, Choi WS, Jung Y, et al. Surveillance of the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus (CoV) infection in healthcare workers after contact with confirmed MERS patients: incidence and risk factors of MERS-CoV seropositivity. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016;22:880–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Le DH, Bloom SA, Nguyen QH, et al. Lack of SARS transmission among public hospital workers, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis 2004;10:265–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ryu B, Cho SI, Oh MD, et al. Seroprevalence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in public health workers responding to a MERS outbreak in Seoul, Republic of Korea, in 2015. Western Pac Surveill Response J 2019;10:46–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Jacobs JL, Ohde S, Takahashi O, Tokuda Y, Omata F, Fukui T. Use of surgical face masks to reduce the incidence of the common cold among health care workers in Japan: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Infect Control 2009;37:417–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].MacIntyre CR, Seale H, Dung TC, et al. A cluster randomised trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Yang P, Seale H, MacIntyre CR, et al. Mask-wearing and respiratory infection in healthcare workers in Beijing, China. Braz J Infect Dis 2011;15:102–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Al-Asmary S, Al-Shehri AS, Abou-Zeid A, Abdel-Fattah M, Hifnawy T, El-Said T. Acute respiratory tract infections among Hajj medical mission personnel, Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis 2007;11:268–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Chokephaibulkit K, Assanasen S, Apisarnthanarak A, et al. Seroprevalence of 2009 H1N1 virus infection and self-reported infection control practices among healthcare professionals following the first outbreak in Bangkok, Thailand. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2013;7:359–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Toyokawa T, Sunagawa T, Yahata Y, et al. Seroprevalence of antibodies to pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza virus among health care workers in two general hospitals after first outbreak in Kobe, Japan. J Infect 2011;63:281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Zhang Y, Seale H, Yang P, et al. Factors associated with the transmission of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 among hospital healthcare workers in Beijing, China. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2013;7:466–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Cheng VC, Tai JW, Wong LM, et al. Prevention of nosocomial transmission of swine-origin pandemic influenza virus A/H1N1 by infection control bundle. J Hosp Infect 2010;74:271–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Loeb M, McGeer A, Henry B, et al. SARS among critical care nurses, Toronto. Emerg Infect Dis 2004;10:251–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Scales DC, Green K, Chan AK, et al. Illness in intensive care staff after brief exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis 2003;9:1205–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Wilder-Smith A, Teleman MD, Heng BH, Earnest A, Ling AE, Leo YS. Asymptomatic SARS coronavirus infection among healthcare workers, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis 2005;11:1142–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Ho KY, Singh KS, Habib AG, et al. Mild illness associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: lessons from a prospective seroepidemiologic study of health-care workers in a teaching hospital in Singapore. J Infect Dis 2004;189:642–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Peck AJ, Newbern EC, Feikin DR, et al. Lack of SARS transmission and U.S. SARS case-patient. Emerg Infect Dis 2004;10:217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Seto WH, Tsang D, Yung RW, et al. Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Lancet (London, England) 2003;361:1519–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Yin WW, Gao LD, Lin WS, et al. Effectiveness of personal protective measures in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2004;25:18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Liu W, Tang F, Fang L-Q, et al. Risk factors for SARS infection among hospital healthcare workers in Beijing: a case control study. Trop Med Int Health 2009;14:52–9. [Google Scholar]

- [71].Nishiura H, Kuratsuji T, Quy T, et al. Rapid awareness and transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hanoi French Hospital, Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005;73:17–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Teleman MD, Boudville IC, Heng BH, Zhu D, Leo YS. Factors associated with transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome among health-care workers in Singapore. Epidemiol Infect 2004;132:797–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Pei LY, Gao ZC, Yang Z, et al. Investigation of the influencing factors on severe acute respiratory syndrome among health care workers. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2006;38:271–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Alraddadi BM, Al-Salmi HS, Jacobs-Slifka K, et al. Risk factors for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection among healthcare personnel. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22:1915–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Hall AJ, Tokars JI, Badreddine SA, et al. Health care worker contact with MERS patient, Saudi Arabia. Emerg Infect Dis 2014;20:2148–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Kim T, Jung J, Kim SM, et al. Transmission among healthcare worker contacts with a Middle East respiratory syndrome patient in a single Korean centre. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016;22:e11–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Park JYKB, Chung KH, Hwang YI. Factors associated with transmission of Middle East respiratory syndrome among Korean healthcare workers: infection control via extended healthcare contact management in a secondary outbreak hospital. Respirology (Carlton, Vic) 2016;21: (supple 3): 89.(abstr APSR6-0642).27005372 [Google Scholar]

- [78].Burke RM, Balter S, Barnes E, et al. Enhanced contact investigations for nine early travel-related cases of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States. PLoS One 2020;15:e0238342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Wang Q, Huang X, Bai Y, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 in medical staff members of neurosurgery departments in Hubei province: a multicentre descriptive study. MedRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [80].Bischoff WE, Turner J, Russell G, Blevins M, Missaiel E, Stehle J. How well do N95 respirators protect healthcare providers against aerosolized influenza virus? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2018;40:01–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Hwang SY, Yoon H, Yoon A, et al. N95 filtering facepiece respirators do not reliably afford respiratory protection during chest compression: a simulation study. Am J Emerg Med 2020;38:12–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Lu W, Zhu XC, Zhang XY, Chen YT, Chen WH. Respiratory protection provided by N95 filtering facepiece respirators and disposable medicine masks against airborne bacteria in different working environments. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi 2016;34:643–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Ramirez JA, O'Shaughnessy PT. The effect of simulated air conditions on N95 filtering facepiece respirators performance. J Occup Environ Hyg 2016;13:491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].World Health Organization. Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [85].Wu JT, Leung K, Leung GM. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet (London, England) 2020;395:689–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Conly J, Seto WH, Pittet D, et al. Use of medical face masks versus particulate respirators as a component of personal protective equipment for health care workers in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2020;9:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Healthcare Personnel during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. 2020. [Google Scholar]