Abstract

BACKGROUND:

To investigate the clinical characteristics and risk factors of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative patients with Talaromyces marneffei (T. marneffei) infection.

METHODS:

We retrospectively collected the clinical information of HIV-negative patients with T. marneffei infection from January 1, 2010 to June 30, 2019, and analyzed the related risk factors of poor prognosis.

RESULTS:

Twenty-five cases aging 22 to 79 years were included. Manifestations of T. marneffei infection included fever, cough, dyspnea, chest pain or distress, lymphadenopathy, ear, nose, and throat (ENT) and/or skin lesions, bone or joint pain, edema and pain in the lower extremities, digestive symptoms, icterus, malaise, and hoarseness. Two cases had no comorbidity, while 23 cases suffered from autoimmune disease, pulmonary disease, cancer, and other chronic diseases. Sixteen cases had a medication history of glucocorticoids, chemotherapy or immunosuppressors. Pulmonary lesions included interstitial infiltration, nodules, atelectasis, cavitary lesions, pleural effusion or hydropneumothorax, bronchiectasis, pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary edema, and consolidation. The incidence of osteolytic lesions was 20%. Eight patients received antifungal monotherapy, and 11 patients received combined antifungal agents. Fifteen patients survived and ten patients were dead. The Cox regression analysis showed that reduced eosinophil counts, higher levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), lactic dehydrogenase (LDH), myoglobin (Mb), procalcitonin (PCT), and galactomannan were related to poor prognosis (hazard ratio [HR]>1, P<0.05).

CONCLUSIONS:

Bone destruction is common in HIV-negative patients with T. marneffei infection. Defective cell-mediated immunity, active infection, multiple system, and organ damage can be the risk factors of poor prognosis.

Keywords: Talaromyces marneffei, Human immunodeficiency virus, Bone destruction, Risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Talaromyces marneffei (T. marneffei), formerly known as Penicillium marneffei, is an opportunistic pathogen prevalent in Southeast Asia, especially in Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, Cambodia, Malaysia, China, and India.[1-4] T. marneffei infection has been previously considered as a life-threatening disseminated fungal infection exclusively in HIV-positive patients.[5,6] However, the use of antiretroviral therapy and other control measures for the HIV infection have changed the epidemiology of T. marneffei infection, with an increasing number of infected cases reported in HIV-negative patients who were in other congenital or acquired immunocompromising conditions.[7] Higher mortality in HIV-negative patients with T. marneffei infection than in HIV-positive patients has been reported, which is possibly caused by delayed diagnosis.[5,8] In this study, we aim to analyze the characteristics and clinical outcomes of HIV-negative patients with T. marneffei infection in our hospital from Southern China to discover some risk factors for this opportunistic and lethal infection.

METHODS

Study population

HIV-negative patients with culture-documented T. marneffei infection in our hospital from January 1, 2010 to June 30, 2019 were reviewed. Only patients with adequate clinical information and specimens available for analysis were included.

Diagnostic criteria for T. marneffei

Patients with positive cultures of T. marneffei from blood, marrow, stool, urine, lymph node, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), sputum, or secretions from skin lesions were diagnozed to have T. marneffei infection. Blood cultures were performed with the BacT/ALERT 3D system (BioMérieux®, Marcy l’Etoile, France). The specimens were incubated for seven days before being reported as negative. Positive fungal cultures were confirmed by Gram staining of a smear of the blood culture broth, followed by subculture onto Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) without cycloheximide with incubation at 25 °C and 37 °C in room air. T. marneffei was identified by the following criteria: (1) demonstration of thermal dimorphism by showing conversion from the yeast-like form at 37 °C to the mold-like form at 25 °C;[9] (2) production of diffusible red pigment from the mold form when it is cultured at 25 °C on SDA; (3) the microscopic morphology of the mycelia including the presence of conidiophore-bearing biverticillate penicilli, with each penicillus being composed of four to five metulae with smooth-walled conidia.[7] Clinical specimens other than blood were examined microscopically both by Gram staining and after digestion with 20% KOH, for the presence of fungal elements. The specimens were then cultured on SDA at 25 °C and 37 °C.

Data collection

Clinical information on age, gender, comorbidities, medication history, symptoms, mean diagnosis time from admission, laboratory results, imaging manifestations, antibiotic therapies, and clinical outcomes was collected and analyzed. If the death occurred within two weeks after diagnosis or if persistent positive fungal cultures were found at the time of death, then a causal relation between T. marneffei infection and the death was considered.

Statistical analysis

All patients were divided into the survival group and the death group according to their clinical outcome. Data were presented in numbers (%), mean±standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed values, median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed values. We used the Mann-Whitney U-test, Student’s t-test or Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate to compare the demographic data and clinical characteristics between the survival group and the death group. Univariable analysis and multivariable analysis of risk factors for all-cause mortality were used for logistic regression analysis. Variables with a P-value <0.10 from the univariable analysis were then tested in multivariable models using forward stepwise procedures. Analysis was performed through IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 16 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, USA). A P-value of <0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Demographic data and clinical characteristics

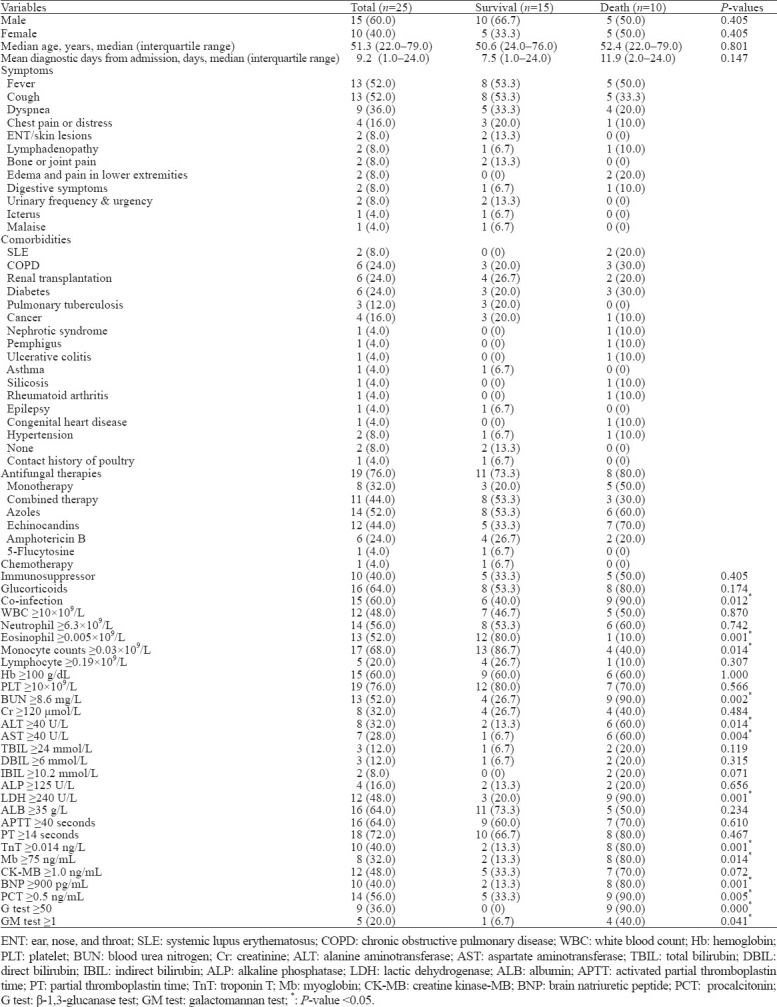

Twenty-five HIV-negative patients with T. marneffei infection, aging 22.0–79.0 years, were included in our study. The median age was 51.3 years. The ratio of male and female was 15:10. Demographic data and clinical characteristics of T. marneffei-infected patients are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of T. marneffei-infected patients, n (%)

Laboratory findings

The culture-positive specimens (n=32) were obtained from sputum (53%), blood (19%), urine (9%), lymph node (6%), BALF (6%), skin (3%), and central venous catheter tip (3%). Ten (40%) patients had no concurrent infection, while 15 (60%) patients were co-infected with fungi such as Candida Glabrata (n=1), Candida albicans (n=2), Aspergillus (n=3), Trichosporon asahii (n=1), and bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n=1), Burkholderia cepacia (n=4), Haemophilus influenzae (n=2), Streptococcus pneumoniae (n=1), Acinetobacter bauman (n=1), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (n=2), Staphylococcus (n=1), Staphylococcus aureus (n=1), Staphylococcus haemolyticus (n=1), Klebsiella pneumonia (n=2), Enterobacter cloacae (n=1), Enterococcus faecium (n=1), Escherichia coli (n=1), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (n=1), and Mycobacterium kansasii (n=1).

Imaging results

The chest computed tomography (CT) manifestations in 19 patients with pulmonary lesions were as follows: interstitial infiltration (63.1%), nodules (26.3%), atelectasis (21.0%), cavitary lesions (21.0%), pleural effusion or hydropneumothorax (15.7%), bronchiectasis (15.7%), pulmonary fibrosis (15.7%), pulmonary edema (10.5%), consolidation (5.2%). Though some patients in our study were co-infected with Aspergillus, no patient showed any typical signs of aspergillosis. Six patients had no lung involvement.

Osteolytic lesions were found in 5 (20%) patients whose lumbar vertebrae, thoracic vertebrae, humerus, ribs, axial bone and pelvis were involved. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) showed generalized lymphadenopathy, active bone metabolism, and bone destruction.

Therapy of T. marneffei infection

Nineteen (76%) patients received antifungal therapy. Eight patients were treated with monotherapy, while 11 patients were treated with combined antifungal agents. Used antifungal agents included amphotericin B, voriconazole, itraconazole, caspofungin, micafungin, and 5-flucytosine. In consideration of contamination, 6 (24%) T. marneffei-positive patients were not given antifungal treatment. They were treated with antibiotics for bacterial infection.

Clinical outcomes

In our study, 15 (60%) patients survived at discharge, and 10 (40%) patients were dead. The mean diagnostic time from admission in surviving patients was 7.5 days, while it was 11.9 days in dead patients. Comparing these two groups, we found statistically significant differences (P<0.05) in the percentage of co-infection, eosinophil counts, monocyte counts, the levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), lactic dehydrogenase (LDH), troponin T (TnT), myoglobin (Mb), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), procalcitonin (PCT), β-1,3-glucanase, and galactomannan. The univariate Cox regression showed that the diagnostic time, reduced eosinophil and monocyte counts, higher levels of BUN, ALT, AST, LDH, TnT, Mb, BNP, PCT, β-1,3-glucanase, and galactomannan were related to poor prognosis (95% confidence interval [CI], P<0.05). The multivariate Cox regression showed that reduced eosinophil counts, higher levels of BUN, ALT, AST, LDH, Mb, PCT, and galactomannan were related to poor prognosis (hazard ratio [HR]>1, P<0.05).

DISCUSSION

The current study found that the HIV-negative patients with disseminated T. marneffei infection manifested similar symptoms to those reported in the literature.[8] As one of the intracellular pathogens, T. marneffei proliferates in macrophages and disseminates via the reticuloendothelial system.[10] The infection is characterized by fungal invasion of multiple systems, especially blood, bone marrow, skin, lungs, and reticuloendothelial tissues, which was also found in our study.

About 20% of included patients had bone damage in the spine, pelvis, humerus, and ribs. Here we should mention that T. marneffei infection combined with osteolytic bone destruction is not rare.[8,11-13] A previous study reported that the osteolytic lesions often occurred in long bones and flat bones, such as femur, humerus, tibia, clavicle, ribs, skull, scapula, vertebrae, and ilium.[14] They can be multiple lesions, accompanied by obvious bone pain, and prone to pathological fractures.[15] HIV-positive patients often have leukopenia, positive blood cultures, fever, splenomegaly, and umbilical skin lesions, but HIV-negative individuals are more likely to have increased leukocytes (higher CD4+ cell counts), negative blood cultures, dyspnea, and bone destruction.[2,4,7] Kudeken et al[16,17] reported that the osteolysis could be caused by the effect of leukocyte hydrolase in the lesion, and was closely related to strong autoimmune response induced by leukocyte and high antibody titers. The rare occurrence of osteolysis in HIV-positive patients may be due to insufficient quantity and deficient function of leukocyte. Bone imaging often manifests multifocal radioactive concentration, which can be easily misdiagnosed as metastases, suppurative osteomyelitis, multiple myeloma, and bone tuberculosis. Talaromycosis involving bone destruction often indicates more severe levels of the disease and a higher recurrence rate. Thus, patients should be treated with prolonged antifungal therapy along with regular monitoring of blood routine tests and bone imaging, avoiding the possibility of relapse.[18]

The host defense against T. marneffei infection depends on effective cell-mediated immunity with the activation of macrophages by T-lymphocyte-derived cytokines, especially those from the T helper type 1 (Th1) response, such as interleukin-12 (IL-12), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). A polarized Th1 response prevents immune evasion by T. marneffei in invaded mononuclear phagocytes and induces macrophage killing of intracellular T. marneffei via the L-arginine-dependent nitric oxide pathway.[1,8] These reports suggest that patients with deficient cell-mediated immune status can be susceptible to T. marneffei. In our study, most HIV-negative patients with talaromycosis had comorbidities like diabetes that damaged the immune function, and chronic pulmonary diseases (tuberculosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and silicosis) that impaired the integrity of original tissue structure. Besides, those who suffered from autoimmune diseases, organ transplantation and cancer needed to be treated with glucocorticoids, immunosuppressors or chemotherapies, which weakened their immune function. With the increased incidence of autoimmune diseases and the use of immunotherapy (anti-CD20 or anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibodies) in endemic regions of T. marneffei,[19] it would be important for clinicians to remain on high alert and perform continuous surveillance for the cell-mediated immune status and the opportunistic infections in those susceptible patients.

Through the primary analysis, we found statistically significant differences between the surviving group and the death group in co-infection and the levels of some biochemical biomarkers. These results showed that HIV-negative patients with T. marneffei infection could have higher mortality when combined with other infections, lower counts of eosinophils and monocytes, and higher levels of BUN, ALT, AST, LDH, TnT, Mb, BNP, PCT, β-1,3-glucanase and galactomannan, indicating defective immunity, active infection, multiple system and organ damage. In comparison, one study found that underlying disease, lower CD4+ cell percentage, and T lymphocyte cell percentage were associated with overall survival.[20] Wang et al[21] mentioned that multiple system and organ damage was one main cause of poor prognosis for HIV-negative patients. We subsequently performed the Cox regression analysis to discover the risk factors of patients’ poor prognosis. Both the univariate and multivariate analysis showed reduced eosinophil counts, higher levels of BUN, ALT, AST, LDH, Mb, PCT and galactomannan significantly associated with poor prognosis. Combining our previous findings, we suggested that defective cell-mediated immunity, active infection, multiple system, and organ damage could be the risk factors of poor prognosis.

In terms of antifungal therapy, the mortality of patients under monotherapy was 62.5% (5/8). Monotherapy included voriconazole or echinocandins. Meanwhile, the mortality of patients under combined therapy was 27.3% (3/11). One of the dead patients was treated with micafungin and caspofungin. An in vitro study found that the azoles had high activity against T. marneffei (except for fluconazole), amphotericin B showed intermediate antifungal activity, while echinocandins were intermediate to resistance.[22] International guidelines recommend amphotericin B as the first-line initial antifungal treatment for talaromycosis in HIV-infected patients, along with the itraconazole as maintenance treatment and prophylaxis.[23,24] However, the standard recommendation regarding the appropriate duration of treatment and prophylaxis of T. marneffei in HIV-negative patients is still unavailable. So the therapeutic protocol can vary significantly in different hospitals.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, we had limited results due to the small population. Secondly, the duration and dose of antifungal treatment were not mentioned clearly so that we could not observe and compare the effects of different antifungal agents on hospitality mortality. And we did not detect the CD4+ cell counts of studied patients for immune status evaluation. We expect that further large-scale multicenter clinical studies will compare relevant effects of antifungal agents, discover further risk factors of T. marneffei infection or develop a reliable diagnostic tool for early identification.

CONCLUSIONS

Bone destruction is a common manifestation of HIV-negative patients with T. marneffei infection. Defective cell-mediated immunity, active infection, multiple system, and organ damage can be the risk factors of poor prognosis.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81801948).

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of our hospital. Informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of this study.

Conflicts of interests: All authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Contributors: HYW and WJL contributed equally to this work. JX and PHG conceived the project and designed the study. HYW, WJL and BL analyzed and interpreted the data. HYW and WJL drafted the primary draft of the manuscript. LYW, AQJ, WDC, PHG, and JX revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors have revised and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors confirm that the manuscript has not been published before and it represents honest work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vanittanakom N, Cooper CR Jr, Fisher MC, Sirisanthana T. Penicillium marneffei infection and recent advances in the epidemiology and molecular biology aspects. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(1):95–110. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.1.95-110.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawila R, Chaiwarith R, Supparatpinyo K. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of Penicilliosis marneffei among patients with and without HIV infection in Northern Thailand:a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:464. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsson M, Nguyen LH, Wertheim HF, Dao TT, Taylor W, Horby P, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of Penicillium marneffei infection among HIV-infected patients in northern Vietnam. AIDS Res Ther. 2012;9(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li HR, Cai SX, Chen YS, Yu ME, Xu NL, Xie BS, et al. Comparison of Talaromyces marneffei infection in human immunodeficiency virus-positive and human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients from Fujian, China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2016;129(9):1059–65. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.180520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pang W, Shang P, Li Q, Xu J, Bi L, Zhong J, et al. Prevalence of opportunistic infections and causes of death among hospitalized HIV-infected patients in Sichuan, China. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2018;244(3):231–42. doi: 10.1620/tjem.244.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang J, Meng S, Huang S, Ruan Y, Lu X, Li JZ, et al. Effects of Talaromyces marneffei infection on mortality of HIV/AIDS patients in southern China:a retrospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25(2):233–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao C, Xi L, Chaturvedi V. Talaromycosis (penicilliosis) due to Talaromyces (Penicillium) marneffei:insights into the clinical trends of a major fungal disease 60 years after the discovery of the pathogen. Mycopathologia. 2019;184(6):709–20. doi: 10.1007/s11046-019-00410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan JF, Lau SK, Yuen KY, Woo PC. Talaromyces (Penicillium) marneffei infection in non-HIV-infected patients. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016;5:e19. doi: 10.1038/emi.2016.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Lin Z, Shi X, Mo L, Li W, Mo W, et al. Retrospective analysis of 15 cases of Penicillium marneffei infection in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients. Microb Pathog. 2017;105:321–5. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pongpom M, Vanittanakom P, Nimmanee P, Cooper CR, Jr, Vanittanakom N. Adaptation to macrophage killing by Talaromyces marneffei. Future Sci OA. 2017;3(3):FSO215. doi: 10.4155/fsoa-2017-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiu Y, Zhang J, Liu G, Zhong X, Deng J, He Z, et al. Retrospective analysis of 14 cases of disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection with osteolytic lesions. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:47. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0782-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ge Y, Xu ZJ, Hu YT, Huang M. Successful voriconazole treatment of Talaromyces marneffei infection in an HIV-negative patient with osteolytic lesions. J Infect Chemother. 2019;25(3):204–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan YF, Woo KC. Penicillium marneffei osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72(3):500–3. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B3.2341456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pun TS, Fang D. A case of Penicillium marneffei osteomyelitis involving the axial skeleton. Hong Kong Med J. 2000;6(2):231–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang JQ, Yang ML, Zhong XN, He ZY, Liu GN, Deng JM, et al. A comparative analysis of the clinical and laboratory characteristics in disseminated Penicilliosis marneffei in patients with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2008;31(10):740–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kudeken N, Kawakami K, Saito A. Cytokine-induced fungicidal activity of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes against Penicillium marneffei. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999;26(2):115–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kudeken N, Kawakami K, Saito A. Mechanisms of the in vitro fungicidal effects of human neutrophils against Penicillium marneffei induced by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;119(3):472–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang X, Si L, Li Y, Zhang J, Deng J, Bai J, et al. Talaromyces marneffei infection relapse presenting as osteolytic destruction followed by suspected nontuberculous mycobacterium infection during 6 years of follow-up:a case update. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;93:208–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan JF, Chan TS, Gill H, Lam FY, Trendell-Smith NJ, Sridhar S, et al. Disseminated infections with Talaromyces marneffei in non-AIDS patients given monoclonal antibodies against CD20 and kinase inhibitors. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(7):1101–6. doi: 10.3201/eid2107.150138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu Y, Liao HF, Zhang JQ, Zhong XN, Tan CM, Lu DC. Differences in clinical characteristics and prognosis of Penicilliosis among HIV-negative patients with or without underlying disease in Southern China:a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:525. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1243-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang YG, Cheng JM, Ding HB, Lin X, Chen GH, Zhou M, et al. Study on the clinical features and prognosis of Penicilliosis Marneffei without human immunodeficiency virus infection. Mycopathologia. 2018;183(3):551–8. doi: 10.1007/s11046-017-0236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lei HL, Li LH, Chen WS, Song WN, He Y, Hu FY, et al. Susceptibility profile of echinocandins, azoles, and amphotericin B against yeast phase of Talaromyces marneffei isolated from HIV-infected patients in Guangdong, China. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;37(6):1099–102. doi: 10.1007/s10096-018-3222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan JE, Benson C, Holmes KK, Brooks JT, Pau A, Masur H. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents:recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58(RR-4):1–207. quiz CE1-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Supparatpinyo K, Perriens J, Nelson KE, Sirisanthana T. A controlled trial of itraconazole to prevent relapse of Penicillium marneffei infection in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(24):1739–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812103392403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]