Abstract

Cell migration on 2D substrates is typically characterized by lamellipodia at the leading edge, mature focal adhesions, and spread morphologies. These observations result from adherent cell migration studies on stiff, elastic substrates, as most cells do not migrate on soft, elastic substrates. However, many biological tissues are soft and viscoelastic, exhibiting stress relaxation over time in response to a deformation. Here, we systematically investigate the impact of substrate stress relaxation on cell migration on soft substrates. We find that cells migrate minimally on substrates with an elastic modulus of 2 kPa that are elastic or exhibit slow stress relaxation but migrate robustly on 2 kPa substrates that exhibit fast stress relaxation. Strikingly, migrating cells were not spread and did not extend lamellipodial protrusions, but were instead rounded, with filopodia protrusions extending at the leading edge, and exhibited small nascent adhesions. Computational models of cell migration based on a motor-clutch framework predict the observed impact of substrate stress relaxation on cell migration and filopodia dynamics. Our findings establish substrate stress relaxation as a key requirement for robust cell migration on soft substrates and uncover a mode of 2D cell migration marked by round morphologies, filopodia protrusions, and weak adhesions.

One/two-sentence summary:

The impact of substrate stress relaxation on cell motility has now been investigated. While cells do not typically migrate on soft elastic substrates, it is now shown that cells migrate robustly on soft viscoelastic substrates with fast stress relaxation using a migration mode marked by rounded cell morphologies and filopodia protrusions extending at the leading edge.

Introduction

Cell migration plays a key role in development, homeostasis, immune cell trafficking, wound healing, and cancer metastasis1. Cell migration is often studied on 2D substrates where adherent cell migration is characterized by lamellipodial protrusion at the leading edge and is mediated by Rac, a growing dendritic actin network, highly spread morphologies, focal adhesions, high traction strains, and myosin contractility at the trailing edge1–3. Only when adherent cells are confined, as for cells migrating through dense 3D matrices, microchannels, or micron-scale spacings between flat substrates, has it been found that cells can migrate adopting rounded morphologies3–7. This contrasts the behavior of immune cells, such as neutrophils or dendritic cells, which can migrate with rounded morphologies and weak adhesions at much higher speeds8–10. While there are various modes of migration found under confinement, on 2D substrates, lamellipodia-mediated migration has been found to be almost universal for adherent cells. However, there is growing recognition that filopodia, thin actin-rich protrusions, couple with lamellipodia to play a key role in cell migration in certain contexts11,12. Filopodia have been implicated in substrate tethering, mechanosensing, and generation of guidance cues11–13.

Studies over the past four decades have elucidated molecular details of cell migration on 2D substrates and found that biophysical cues, including cell adhesion ligand density and stiffness of cell culture substrates, regulate cell migration2,14. Cell migration speed peaks at intermediate ligand density and is impaired if ligand density is too low or too high2,15. Further, cells exhibit increased migration speeds with increased stiffness, or display a biphasic response with respect to stiffness, with maximum migration speeds occurring at intermediate stiffnesses16,17. Mirroring the finding of how stiffness impacts cell migration, are findings on how substrate stiffness impacts lamellipodial and filopodial protrusions. Recent studies showed that the stability of lamellipodia protrusions increases with stiffness18. Furthermore, while the number of filopodia protrusions extending from a cell has been found to decrease with increase in stiffness, the number of stable filopodia increase with stiffness13,19,20. The motor-clutch model was proposed as a framework to describe how the cell’s intrinsic and extrinsic mechanical cues modulate key aspects of cell migration, adhesion dynamics and force transmission to the substrate. The stochastic model of the motor-clutch hypothesis developed by Chan and Odde mathematically describes the experimentally observed response of cell migration to substrate stiffness17,21. These and other 2D migration studies typically study cell migration on glass surfaces or on elastic substrates with elastic moduli in the tens of kPa range17,22, as cells on softer, elastic substrates are rounded, and are unable to robustly migrate16.

While stiff, elastic substrates are commonly used to study cell migration, many biological tissues are soft, with elastic moduli closer to 1 kPa23, and are viscoelastic, exhibiting stress relaxation over time in response to a deformation24. Stiffness relates to the initial resistance of the material to deformation, while stress relaxation describes how that resistance relaxes over time. Soft biological tissues exhibit stress relaxation half times ranging from ~10 to 1,000 s24,25. Recent studies have implicated substrate viscoelasticity as a mediator of diverse cellular behaviors including cell spreading26–29, stem cell differentiation24,29, cell proliferation29,30, and cartilage matrix formation31. Substrate stress relaxation also impacts the type and extent of substrate adhesions formed, with the relation dependent on cell and substrate type26,27,29,32. However, the impact of substrate stress relaxation on cell migration, lamellipodial protrusions, and filopodia remain unclear. Here, we systematically investigate the role of substrate stress relaxation on cell migration on soft, viscoelastic substrates. We find that faster substrate stress relaxation enhances cell migration and increases filopodia length and lifetime. Further, we demonstrate that cells utilize a mode of migration, mediated by filopodia but not lamellipodia, to migrate on soft, viscoelastic substrates.

Results

Faster substrate stress relaxation enhances cell migration

We utilized viscoelastic substrates with independently tunable stress relaxation for 2D cell migration studies. These substrates consist of interpenetrating networks (IPNs) of alginate and reconstituted basement membrane matrix (rBM)4,28. Alginate, an inert block copolymer displays limited susceptibility to degradation by proteolysis by mammalian enzymes, and is crosslinked into a network with calcium. rBM matrix contains cell adhesion ligands relevant to the basement membrane, and was chosen because cancer cells migrating in vivo and in vitro have been shown to migrate along and interact with basement membrane-rich interfaces33,34. By varying the amount of ionic calcium crosslinker and molecular weight of the alginate4,24,28, the mechanical properties of the IPNs were varied to obtain IPNs with a range of stress relaxation behaviors but similar initial elastic moduli of ~2 kPa (Fig. 1a,b, Supplementary Figure 1). This enabled an unambiguous attribution of any differences observed in cell migration to differences in stress relaxation, not stiffness or cell adhesion ligand density. Additionally, polyacrylamide (PA) gels coated with rBM were used as model elastic substrates for comparison35. Stress relaxation for IPNs was quantified by the time it takes for the normalized stress to reduce to one-half its peak value (t1/2). The t1/2 values were ~100 s, ~240 s and ~2,200 s for IPNs, which were termed fast-relaxing, medium-relaxing, slow-relaxing respectively based on the relation of these relaxation times to those in soft tissues (Fig. 1c). Elastic polyacrylamide (PA) gels exhibited negligible stress relaxation (Fig. 1c). Note that while these viscoelastic IPNs also exhibit mechanical plasticity4, hydrogel deformation was mostly reversible and elastic over timescales relevant to cell migration on the 2D substrates.

Fig. 1.

Substrate stress relaxation regulates cell migration on soft substrates. a, Young’s modulus of three different formulations of alginate-rBM IPNs (fast, med., and slow) and a polyacrylamide (PA) gel. Data compared to fast, Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons; ns=not statistically significant, ns p>0.9999; n = 20, 5, 9, 4 independent samples (fast, med., slow, elastic). b, Representative stress relaxation tests of different IPNs. c, Time for the normalized stress in the IPN to reduce to one-half (t1/2) its original value in stress relaxation tests. Data compared to fast-relaxing hydrogel, Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons; ns=not significant p=0.0653, ***p=0.0001; n = 15, 4, 6, 4 independent samples (fast, med., slow, elastic). The elastic gel does not show any stress relaxation. a,c, Data are presented as mean values +/− SEM. d, Time series of images of HT-1080 cells on the indicated IPNs. The far-right panel are the trajectories of ~80 randomly selected migrating cells for each condition. Scale bars are 20 μm, 100 μm (cells, trajectories) and time indicated in hours:min. e-l, Mean squared displacement (MSD), and cell migration speed for HT-1080, MDA-MB-231, and MCF-10A human cancer cell lines cultured on viscoelastic substrates or elastic substrates. e,g,i,k, MSD~tα. f, Data compared to fast-relaxing hydrogel, Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons, ****p<0.0001; n = 2,309, 1,263, 1,809 (fast, med., slow) cells examined over 3 independent samples. h, Data compared to 2kPa elastic, Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons, **p=0.0086, ****p<0.0001; n = 471, 611, 3,651 (fast, med., slow) cells examined over 2 independent samples. j, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, ****p<0.0001; n = 4,651, 4,501 (fast, slow) cells examined over 2 independent samples. l, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, ****p<0.0001; n = 1,561, 1,115 (fast, slow) cells examined over 2 independent samples. All statistical tests two-sided.

We investigated the impact of substrate stress relaxation on cell migration. Live-cell confocal microscopy was used to follow the migration of human HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cells, MDA-MB1–231 breast cancer cells, and MCF-10A mammary epithelial cells – cell lines widely used in cell migration studies – on fast, medium, slow-relaxing IPNs as well as elastic PA gels and glass substrates. Sample migrating cells and migration tracks show that faster stress relaxation enhances cell migration (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Movie 1 and 2). Quantification of mean square displacement (MSD) and speed for HT-1080 cells indicates that cells migrate further and faster on fast and medium-relaxing substrates compared to slow-relaxing substrates (Figs. 1e,f). For example, over 1 hour, HT-1080 cells migrate 10 times further on fast-relaxing substrates relative to cells on slow-relaxing substrates. For comparison, HT-1080 cells migrate minimally on elastic PA substrates with a modulus of 2 kPa, but much with higher speeds and distances on ~40 kPa and glass substrates (Fig. 1g,h). While cells migrate to a slightly greater extent on 2 kPa elastic substrates relative to 2 kPa substrates that are slow-relaxing, ligand presentation and density likely differs between IPNs and PA gels. Intracellular calcium imaging indicates that these differences are not due to different calcium amounts used in hydrogel formulation (Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Table 1). As with the HT-1080s, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-10A cells moved farther, and faster on fast-relaxing IPNs compared to slow-relaxing IPNs (Fig. 1). Together, these data show that faster stress relaxation enhances cell migration on soft substrates.

Lamellipodia-independent migration on fast-relaxing substrates

Next, we investigated whether the migration mode observed on soft, fast-relaxing substrates matched the canonical lamellipodia-mediated migration mode previously described on glass and stiff elastic substrates. As such, we first examined cell morphology, since 2D cell migration on glass or stiff elastic substrates is tightly linked to spread morphologies. HT-1080 cells were much more rounded, with greater circularity, and less spread on fast and slow-relaxing IPNs. The observed cortical actin structure was markedly different from the actin rich stress fibers and dense meshwork of actin at the leading edge observed in cells on glass substrates (Fig. 2a). Further, the fan-shaped architecture observed on glass, characteristic of lamellipodia, is absent on viscoelastic substrates (Fig. 2a,b). Quantification of circularity and 2D cell spread area show strong differences in these parameters between cells on viscoelastic substrates versus elastic substrates (Fig. 2c–e). One possible explanation for these differences could be that cells on fast-relaxing IPNs are generally less spread but become more spread only when they migrate. However, analysis of instantaneous speed and circularity indicates that migrating cells on viscoelastic substrates were more circular relative to migrating cells on elastic substrates and lamellipodia was observed on spread cells on glass substrate (Supplementary Figure 3). To summarize, these data indicate that cells use rounded morphologies to migrate on soft, viscoelastic substrates without the use of lamellipodia, which adherent cells almost always use to migrate on glass or stiff and elastic substrates.

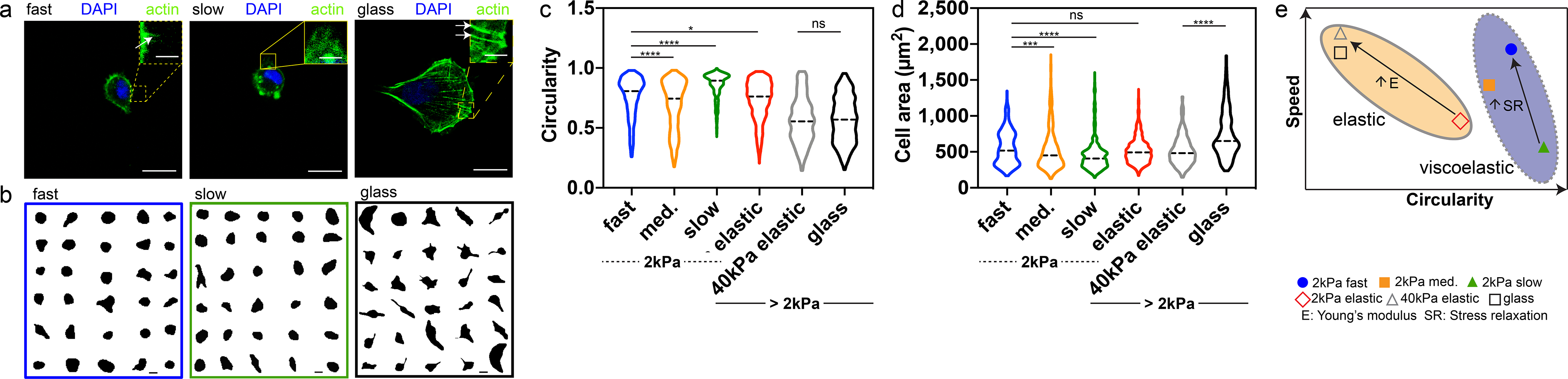

Fig. 2.

Cells migrate on viscoelastic substrates with rounded morphologies. a, HT-1080 cells on fast-relaxing, slow-relaxing, and glass substrates. Actin is in green and nucleus (DAPI) is in blue. Scale bar 20 μm. Inset scale bar 5 μm b, Cell outline of randomly selected HT-1080 cells on fast-relaxing, slow-relaxing and glass substrates. Scale bar 20 μm. c, Circularity of HT-1080 cells on viscoelastic (fast, medium, and slow-relaxing) and elastic (2kPa polyacrylamide, 40kPa polyacrylamide, and glass) substrates. Data compared to fast-relaxing hydrogel, Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons, ns=not statistically significant, ns p>0.9999, *p=0.0131, ****p<0.0001; n = 630, 1,119, 630, 715 (fast, med., slow, glass) cells over 3 independent samples. n = 788, 376 (elastic, 40kPa elastic) cells examined over 1 independent sample. d, Spreading areas of HT-1080 cells on viscoelastic (fast, medium, and slow-relaxing) and elastic (elastic, 40kPa elastic, and glass) substrates. Data compared to fast-relaxing hydrogel, Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons, ns indicates not statistically significant ns>0.9999, ***p=0.0002 ****p<0.0001; n = 630, 1,119, 630, 715 cells (fast, med., slow, glass) over 3 independent samples. n = 788, 376 (elastic, 40kPa elastic) cells examined over 1 independent sample. All statistical tests two-sided. e, Schematic showing instantaneous speed vs circularity for HT-1080 cells on viscoelastic substrates (purple oval with dotted boundary) versus elastic substrates (tan oval with solid boundary). Filled blue circle: fast-relaxing gel, filled orange square: medium-relaxing gel, filled triangle: slow-relaxing gel, open red diamond: 2kPa elastic gel, open silver triangle: 40kPa elastic gel, open black square: glass. SR: stress relaxation. E: Young’s Modulus.

Migration mediated by filopodia protrusions

Since morphological analysis suggested a lamellipodia-independent mode of migration, we sought to determine what other cellular processes might mediate migration on soft, viscoelastic substrates. Cells migrating on fast-relaxing IPNs frequently displayed long, thin, protrusions, reminiscent of filopodia whereas lamellipodia were observed on glass (Fig. 3a,b). Cells on substrates with slow relaxation occasionally extended individual protrusions, while cells on fast-relaxing IPNs extended an average of 6 protrusions every 10 minutes (Fig. 3c). Importantly, pharmacological inhibition of fascin and formin, two key proteins involved in filopodia formation20,21, diminishes the number of protrusions, suggesting these protrusions to be filopodia (Fig. 3d)12,13. Immunofluorescence (IF) staining revealed characteristic localization of myosin-X and VASP at the tip of long actin-rich protrusions (Fig. 3e,f), features unique to filopodia13,36, further supporting the notion that the protrusions are filopodia. Faster substrate stress relaxation increases the number of myosin-X puncta observed at cell periphery, some of which are associated with actin protrusions (Fig. 3g). Not only are these protrusions lost upon inhibition of fascin and formin, but migration is also reduced indicating that filopodia protrusions are important for cell migration (Fig. 3d,h). In addition, siRNA knockdowns of fascin1 and myosin-X substantially diminished cell migration, further confirming the role of filopodia on cell migration (Fig. 3i,j). Taken together, these results demonstrate the role of filopodia in mediating cell migration on soft, viscoelastic substrates.

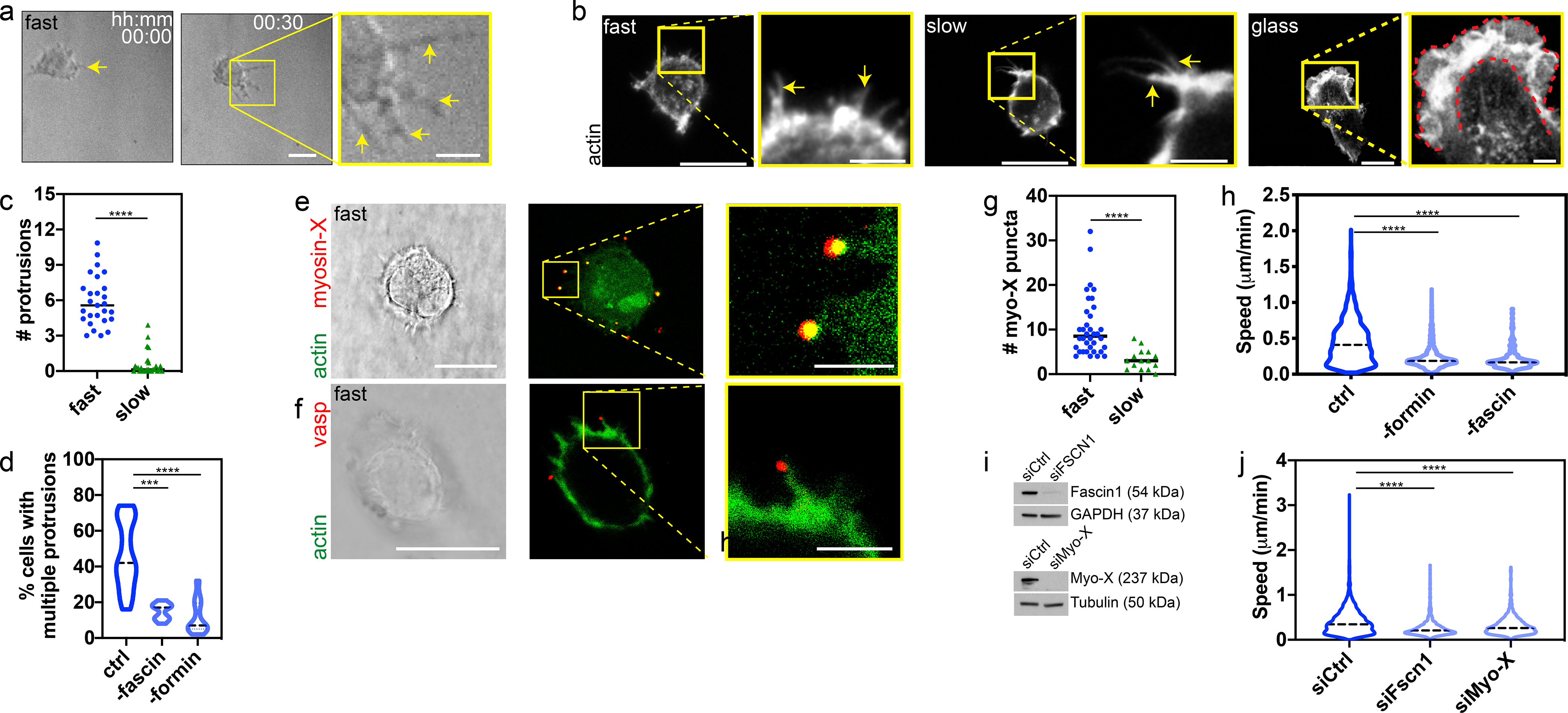

Fig. 3.

Filopodia protrusions mediate migration on soft, fast-relaxing substrates. a, Migrating HT-1080 cell displays multiple protrusions (yellow arrows) at leading edge. Time, hours:min. b, HT-1080 cell displays filopodia protrusions (yellow arrows) on fast and slow-relaxing substrates. Lamellipodia (red outline) observed on spread cell on glass. c, Number of protrusions from HT-1080 cells on fast and slow-relaxing viscoelastic substrates. Kolmogorov-Smirnov, ****p<0.0001; n = 27 cells each examined over 2 independent samples. d, Percentage of HT-1080 cells with protrusions without inhibitor (ctrl=control), and inhibition of fascin (30 μM fascin-G2) and formin (20 μM SMIFH2). Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons, ***p=0.0003 ****p<0.0001; n = 22, 11, 13 (ctrl, -fascin, -formin) cells examined over 3 independent samples (2 for fascin). e,f, Actin, myosin-X, and vasp staining for HT-1080 cells on fast-relaxing substrates. g, Number of peripheral puncta of myosin-X for HT-1080 cells on fast and slow-relaxing substrates. Kolmogorov-Smirnov, ****p<0.0001; n = 36, 15 (fast, slow) cells examined over 2 independent samples. h, HT-1080 cell migration speed without inhibitor, and after inhibition of fascin (30 μM fascin-G2) and formin (20 μM SMIFH2). Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons, ****p<0.0001; n = 2,309, 1,302, 171 (ctrl, -formin, -fascin) cells examined over 3, 2, 1 independent samples. i, Western blot for siRNA knockdown of fascin1 and myosin-X. siCtrl: siRNA empty control, siFscn1: siRNA of fascin1, siMyo-X: siRNA of myosin-X. GAPDH and tubulin are respective loading controls. j, HT-1080 cell migration speed with knockdown of fascin1, and myosin-X. Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons, ****p<0.0001; n = 1,892, 937, 1,237 (siCtrl, siFscn1, siMyo-X) cells examined over 2 independent samples. d,h,j, All data are for cells on fast-relaxing substrates. Comparisons made to fast-relaxing hydrogel without perturbation. All statistical tests two-sided. Images, scale bar: 20 μm, zoom-in/inset: 5 μm.

Migration mediated by nascent adhesions

Next, we sought to elucidate the impact of substrate stress relaxation on cell-substrate adhesions and force generation, as these typically underlie adherent cell migration on 2D substrates. Paxillin, a universal component of nascent and mature adhesions and essential for adhesion dependent cell migration, was first examined37. Cells on fast and slow-relaxing substrates displayed only dot-like, peripheral, paxillin structures, indicative of nascent adhesions (Fig. 4a). Cells formed higher numbers of paxillin adhesions on fast-relaxing substrates relative to slow-relaxing substrates (Fig. 4b). For comparison, cells on glass substrates displayed large and elongated paxillin structures, reminiscent of mature focal adhesions, in addition to nascent adhesions, with ~10 times more paxillin adhesions compared to cells on fast relaxing substrates (Fig. 4a,b). These analyses indicate that fewer, weak, paxillin adhesions are associated with cell migration on fast-relaxing substrates. As adhesions connect actomyosin-based contraction to substrates for force generation, we investigated actin and myosin structures on fast-relaxing substrates. Actin is localized to cell periphery, and substantially fewer phosphorylated myosin rich puncta are observed, mostly localized proximal to cell membrane, on fast-relaxing substrates relative to glass substrates (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Adhesion and traction force mediate migration on fast-relaxing substrates. a,b, Immunofluorescence of paxillin. Paxillin puncta number, area on fast, slow-relaxing, and glass substrates. Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons, ns=not statistically significant, ns p=0.6074, *p=0.0115, ****p<0.0001. For #, data averaged for n = 57, 60, 11 (fast, slow, glass) cells. For area, data averaged for n = 346, 19, 644 (fast, slow, glass) adhesions. Samples examined over 1 independent sample. c, Immunofluorescence staining of actin and phosphorylated myosin (pMyo) on fast-relaxing and glass substrates. d,e, Maximum traction stress during migration for viscoelastic and elastic gels. Kolmogorov-Smirnov, ns p=0.5943; ****p<0.0001; n = 20, 20, 10, 7 (fast, slow, 2kPa elastic, 40kPa elastic) cells each over 1 independent sample. f, Representative substrate displacement for HT-1080 cell (white outline) migrating (left to right). Arrows indicate direction of substrate displacement. g, HT-1080 cell migration speed on fast-relaxing substrate with and without addition of 5 μg/ml β1-integrin blocking or 2 μg/ml TS2/16 activating antibodies (ctrl=control). Kolmogorov-Smirnov, ****p<0.0001; n = 2309, 430, 825 (ctrl, -β1, +β1) cells examined over 2 independent samples, 3 for ctrl. h, HT-1080 cell migration speed on fast-relaxing substrate with and without inhibition of actin polymerization with latrunculin A (100nM), Rac1 (70 μM NSC 23766), and Arp2/3 (50 μM CK 666). Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons, *p=0.0133, 0.0148, ****p<0.0001; n = 2,309, 1,913, 1,233, 1,996 (ctrl, -Arp2/3, -Rac1, +Lat. A) cells examined over 3 independent experiments, 4 for -Arp2/3. i, HT-1080 cell migration speed on fast-relaxing substrate with and without addition of ROCK inhibitor (50 μM Y-27632) and MLCK inhibitor (25 μM ML-7). Kolmogorov-Smirnov, ****p<0.0001; n = 2,309, 1,649, 1,661 (ctrl, -ROCK, -MLCK) cells examined over 3 independent samples, 5 for -ROCK. b,d,g,h,i, Data compared to fast-relaxing hydrogel. All statistical tests two-sided. Images, scale bar: 20 μm, zoom-in/inset: 5 μm.

In addition, we elucidated the nature of traction stresses associated with cell migration on the fast-relaxing substrates. Fluorescent beads were embedded into the gels to monitor traction strains associated with migration. An upper bound on traction stresses can be estimated by assuming the substrates to be elastic and converting traction strains to stresses as in traction force microscopy. As would be anticipated by fewer adhesions on slow-relaxing substrates relative to fast-relaxing substrates, the upper bound on traction stresses are correspondingly lower (Fig. 4d). An upper bound on maximum traction stresses on viscoelastic substrates is estimated to be ~100 Pa, which is comparable to the median value for maximum traction stresses observed on elastic substrates (Fig. 4e). Cell migration on fast-relaxing IPNs is saltatory, with cell translocation punctuated by periods where the cell deforms the substrate (Fig. 4f). During translocation, cells push on the substrate and the highest substrate displacement is observed at the leading edge of translocating cells. Following translocation, beads return to their initial positions indicating that substrate deformations during migration are elastic and that substrate remodeling is negligible (Supplementary Movie 3). Together these indicate that migration on soft, fast-relaxing IPNs requires nascent adhesions and contractility, and is associated with protrusive deformations at the leading edge.

Further, we investigated the role of integrins, actin network activity, and actomyosin based contractility in cell migration on fast relaxing substrates. β1-integrin inhibition and overactivation, using blocking or activating antibodies, substantially diminished cell migration speeds (Fig. 4g), suggesting that integrin engagement is important for cell migration. Next, modulation of actin network activity through inhibition of actin polymerization with latrunculin A, restricting nucleation of growing actin filaments as branches by inhibiting the Arp2/3 complex, or inhibition of Rac1, a Rho GTPase that orchestrates actin network growth, led to reduction in cell motility (Fig. 4h). Further, inhibition of myosin activity diminished cell motility (Fig. 4i). These perturbation studies confirm the role of integrin-based adhesions, actin polymerization, and actomyosin contractility in mediating cell migration on fast relaxing substrates.

Motor-clutch models reproduce experimentally observed impact of stress relaxation

Next, we investigated whether the motor-clutch model could explain experimental results using two motor-clutch based simulations. First, a two-dimensional cell migration simulator (CMS) was implemented to test cell migration differences between fast and slow-relaxing viscoelastic substrates, and between different stiffness values for elastic substrates (Fig. 5a, see Supplementary Information). The CMS is composed of multiple modules to represent cell protrusions, and each module is described by the motor-clutch model21,38. The CMS incorporates mass conservation for actin, myosin, and clutches as well as allows actin filaments to spontaneously form and grow in length. This model predicts that cell migration speed reaches a maximum value at an optimal stiffness on purely elastic substrates17. In the current work, the CMS was used to simulate viscoelastic substrates using a standard linear viscoelastic solid (SLS) model with fixed initial and long-term moduli. The number of motors and clutches adjusted between elastic and viscoelastic substrates since the maximum traction stresses are higher on elastic substrates. CMS speed was found to increase with faster substrate stress relaxation and increased stiffness. These trends are in agreement with experimental findings (Fig. 5b,c). In addition, simulation results are in agreement with the observed impact of stress relaxation on cell morphology and cell area (Supplementary Figure 4). Furthermore, CMS results shows cell migration is reduced upon inhibition of adhesion, actin polymerization, and myosin activity, all consistent with experimental findings (Fig. 5d–f). To summarize, the CMS results show close agreement with observed experimental trends for migration speed as a function of stress relaxation on viscoelastic substrates and stiffness on elastic substrates, as well as the impact of inhibition of adhesion, actin polymerization, and actomyosin contraction.

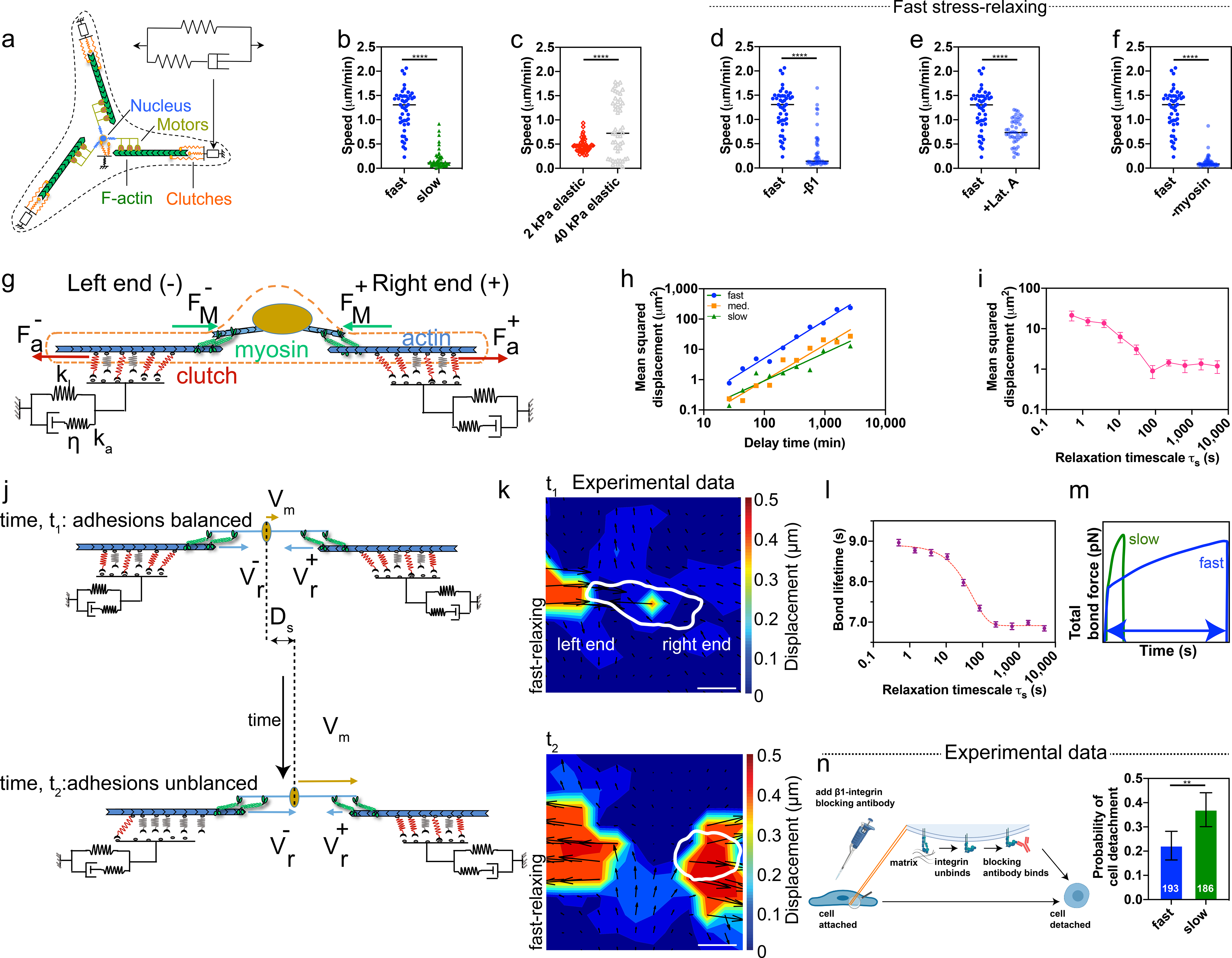

Fig. 5.

Simulations capture impact of substrate stress relaxation on cell migration. a, Schematic of 2D cell migration simulator on viscoelastic substrates. b,c, Predicted cell migration speeds from simulator. Kolmogorov-Smirnov, two-sided, ****p<0.0001; n = 47, 49, 51, 49 (fast, slow, 2 kPa elastic, 40 kPa elastic) cells over 4 independent simulations. d,e,f, Reducing number of clutches, nc (“-β1”), actin polymerization rate, krate by half (“+Lat. A”), and number of motors, nm (“-myosin”), in simulation decreases migration speed. nc = 750, 150 (fast, -β1)), nm = 1,000, 750 (fast, -myosin). Kolmogorov-Smirnov, two-sided, ****p<0.0001; n = 47 (fast), 48 (-β1, +Lat. A), 54 (-myosin) cells over 2 independent simulations. g, Schematic of 1D motor-clutch model of cell on a viscoelastic substrate. h, Simulated MSD plotted versus time with respect to fast, medium and slow stress-relaxing cases. Dotted lines are fits. Data from 10 independent simulations. i, Simulated MSD as a function of relaxation timescale τs. Red line is a fit to results; n = 20 cells examined over 20 independent simulations. j, Schematic of 1D simulation finding of balance of adhesions in stationary cell (top) and unbalanced adhesions in migrating cell (bottom). k, Traction strain map when cell releases tug on matrix. Cell migration: left to right. Scale bar: 20 μm. l, Bond lifetime τf (time elapsed between initial attachment of a single bond to its breakage) plotted versus τs. Data are presented as mean values +/− SEM; n = 20 cells examined over 20 independent simulations. m, Total bond force versus time for fast and slow stress-relaxing cases. n, Probability of cell detachment for adhesion release experiment. Bars indicate mean probabilities, error bars indicate 95% confidence interval. Fisher’s exact test, two-sided, **p = 0.0017; n = 193, 186 (fast, slow) cells examined over 2 independent experiments.

Next, we applied a distinct one-dimensional motor-clutch based model to obtain mechanistic insight into the impact of varying levels of substrate stress relaxation on cell migration27. A consequence of stress relaxation is a decrease from the initial moduli to a lower long-term moduli. The relaxation timescale parameter in the SLS model was varied, while fixing the initial and long-term moduli, in 1D Monte Carlo simulations of migration (Fig. 5g). As a first step, we validated that the simulation replicated key experimental findings. Simulations predicted that faster relaxation increases migration distance and mean square displacement (MSD), and that the MSDs follow a power-law relation with time, all matching the experimental findings (Figs. 5h,i). These simulations reveal insights into the molecular mechanisms by which substrate viscoelasticity impacts cell migration. Initially, opposite ends of the cell share the same number of bound clutches (Fig. 5j–k, Supplementary Figure 5). However, the stochastic bond (clutch) dynamics cause an asymmetry in the bound clutch number between the left and right ends. At the end with less bound clutches (left end in Fig. 5j), each bond now transmits higher tensile force, and hence, has a higher probability of breaking due to the force-dependent unbinding of the clutches. As each bond breaks, even more force is carried by each clutch. Subsequently, the entire stretch of adhesions on this side breaks catastrophically, leading to an increased retrograde flow velocity (Fig. 5j). The unbound end retracts quickly, leading to cell migration towards the right end. Interestingly, this sequence of events is consistent with the traction strain measurements from experiments, as translocation of the cell to the right end is accompanied by a release of tractions on the left end (Fig. 5k). Additionally, simulations predict that cell-matrix bond lifetime should increase with faster substrate stress relaxation (Fig. 5l). Bonds experience a lower force loading rate on substrates with fast stress relaxation, leading to longer bond lifetimes prior to rupture (Fig. 5m). This prediction was tested experimentally by introducing β1-integrin blocking into the media after cells had adhered to the substrates. As β1-integrins unbind from the matrix ligands, based on their bond lifetimes, the blocking antibody can attach to and block the available integrins, making these integrins unavailable to participate in further integrin-ECM bonding. The greater the intrinsic off-rate (shorter lifetime) the higher the likelihood of ß1-integrin blocking, and consequently, the higher the probability of cell detachment. Over a 10-hour window, a higher probability of cell detachment on slow-relaxing gels compared to on fast-relaxing gels is measured, indicating a higher bond lifetime for cells on the fast-relaxing gels (Fig. 5n). In summary, the observed stiffness and bond dynamics are similar to previous observations of the motor-clutch hypothesis, further implicating this hypothesis in our observations21.

Motor-clutch model predicts filopodia dynamics

After finding that the motor-clutch model can predict the impact of stress relaxation on cell migration, we sought to assess the validity of the model by testing whether predictions of the model regarding filopodia dynamics were borne out by experimental observations. Filopodia protrusions were observed to be highly dynamic on both fast and slow-relaxing substrates (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Movie 4 and 5). The one-dimensional motor-clutch model predicted that faster substrate stress relaxation increases both filopodia length and lifetime, as well as a correlation between both of these variables (Figs. 6b–d, Supplementary Figure 6). All three of these predictions were validated experimentally (Fig. 6e–g). Further, the range of values obtained for filopodia length and lifetime are similar to what has been previously reported for filopodia20,39,40. Overall, experimental and simulation data demonstrate that substrate stress relaxation mediates filopodia behavior and migration phenotype (Fig. 6h). Thus, these data indicate that substrate viscoelasticity impacts cell migration through regulation of motor-clutch dynamics and filopodia lifetimes.

Fig. 6.

Substrate stress relaxation regulates filopodia dynamics. a, HT-1080 siR-actin labeled cells on fast and slow-relaxing substrates. Scale bar is 10 μm. Scale bar of time sequence of region of interest is 5 μm. b,c,d, Motor-clutch simulations of filopodia length and lifetime for fast and slow-relaxing substrates. Data compared to fast-relaxing hydrogel, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, two-sided, ****p<0.0001; n = 57, 68 (fast, slow) cells examined over 20 independent simulations. e,f,g, Quantification of filopodia length and lifetime for fast and slow-relaxing substrates from experiments with siR-actin labeled HT-1080 cells. Data compared to fast-relaxing hydrogel, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, two-sided, for filopodia length and lifetime, ***p=0.0006, ****p<0.0001; n = 41, 34 (fast, slow) cells examined over 2 independent samples. All statistical tests two-sided. d,g, r is Pearson correlation coefficient. h, Schematic highlights effect of substrate stress relaxation on cell migration in current work. White region: non-motile cells; blue region: motile cells. Cell-substrate bonds experience a faster loading rate on slow relaxing substrates relative to fast relaxing substrates resulting in a shorter lifetime and fewer bonds. The short bond lifetime causes smaller adhesion and reduced filopodia lifetime, allowing cells to change migration direction more frequently. This reduces the persistence of cell migration and impairs migration.

Outlook

Here, we find that substrate stress relaxation is a key modulator of adherent cell migration on soft, viscoelastic substrates. Our results demonstrate that faster substrate stress relaxation promotes increased migration distance and speed on soft substrates that are viscoelastic (Fig. 6h). These results are consistent for HT-1080 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells, two cancer cell lines that are broadly used for cell migration studies, as well as for non-tumorigenic MCF-10A epithelial cells. However, it is possible some adherent cells exhibit migration phenotypes different from what we observe here. Robustly migrating cells on fast stress-relaxing IPNs are rounded and characterized by paxillin adhesions, and long, thin filopodia protrusions at the leading edge. Furthermore, faster substrate relaxation increases filopodia number, adhesions, filopodia length and lifetime, allowing filopodia to grow in length. Filopodia, in turn, regulate cell migration. These observations establish that, when presented with the appropriate biophysical cues, cells can display different migration modes beyond the canonical mode of 2D cell migration, which is characterized by high tractions, focal adhesions and lamellipodia. Taken together, our results demonstrate that substrate stress relaxation is a fundamental substrate mechanical property that regulates cell migration and filopodial protrusions.

Our study of cell migration on soft, viscoelastic substrates was motivated by the emerging recognition that many soft tissues exhibit substantial viscoelasticity24,41. Viscous characteristics of biological tissues, as characterized by the loss modulus, are typically around 10% of their elastic characteristics, as characterized by the storage modulus26,42. Similarly, stress relaxation tests, in which the stress is measured in response to a constant strain and where stress corresponds to the resistance to deformation, show that many biological soft tissues relax stress on time scales of a few seconds to tens of minutes43. For instance, rat brain, rat liver, and rat skin have been reported to have characteristic stress relaxation half times of ~1s, ~50s, and ~650s respectively, while human breast cancer tissue has a stress relaxation half time ~10s43. Though, these times can vary depending on the modality of measurement and level of strain imposed42. Importantly, alterations in tissue viscoelasticity are associated with the progression of human pathologies like cancer and fibrosis4,26,44. A recent study found that associated with the transformation of healthy pancreas to pancreatic cancer is a decrease in characteristic decay time from ~93s to 66s41. Our study implicates that such alterations in stress relaxation may impact processes involving cell migration in these contexts.

In contrast to the lamellipodia-mediated migration typically observed for cells on 2D stiff, elastic substrates, cell migration on viscoelastic substrates is lamellipodia-independent, and instead mediated by filopodia. Lamellipodia are characterized by branched actin networks whereas filopodia protrusions consist of long, unbranched actin filaments in a thin protrusion. Lamellipodia are often described as cellular structures that drive cell migration as they are typically observed during cell migration on stiff elastic substrates. While filopodia have been implicated in cell-substrate adhesion and mechanosensing, their role in cell migration is not fully understood. Here, we find that filopodia are essential for migration on soft viscoelastic substrates, with filopodia protrusions extending in the direction of migration, and inhibition of filopodia also blocking cell migration. Increase in filopodia length with substrate stress relaxation likely increases the probabilities of cell-substrate adhesion and consequently greater traction force to support cell migration.

Computational simulations utilizing the motor-clutch model of force transmission agree with experimental observations and suggest additional mechanistic insights. Our 1D simulations predict that clutch lifetime increases with faster substrate relaxation, allowing cells to migrate in a given direction for a longer time. On slow-relaxing substrates, cell-substrate bonds experience a fast loading rate, even at times that are well below the stress relaxation half times for the materials. Consequently, these bonds, on average, fail more quickly resulting in a shorter lifetime. However, with sufficiently fast stress relaxation, individual bonds have a longer lifetime resulting in a higher likelihood of formation of nascent adhesions, which consist of multiple bonds. Nascent adhesions in turn stabilize filopodia and allow them to extend much further and over longer times. Whereas, at higher loading rates, the shorter bond lifetime results in a small filopodia lifetime, which limits how long the filopodia grows and allows cells to change migration direction more frequently. This reduces persistence of cell migration and reduces the amount of sustained traction forces cells can generate to support migration. Furthermore, the increased bond lifetime on fast-relaxing substrate could promote cell spreading, which leads to greater spread area which we observe. This finding is consistent with a previous study that demonstrated that increased integrin bond lifetime allows cells to spread on soft substrates18. Another explanation invokes the previous finding that at optimal substrate stiffness, the force-loading rate on the clutch is comparable to integrin-extracellular matrix (ECM) bond lifetime21. This results in increased number of engaged clutches on average and subsequently efficient traction force transmission to the substrate to drive cell migration. Higher (or lower) substrate stiffness than the optimal substrate stiffness leads to inefficient force transmission and thus impaired cell migration. In our 2D CMS simulations, the optimal migration of cells on elastic substrates is at higher stiffness. For cells on viscoelastic substrates, the optimal migration occurs at the lower stiffness. For fast-relaxing substrates, the stiffness experienced by the cell decrease with time faster (Supplementary Figure 7), potentially shifting the cell closer to the optimal stiffness and enhancing migration. Taken together, these results suggest that substrate viscoelasticity regulates bond lifetimes and/or the number of engaged clutches, which in turn mediates cell migration.

Robustly migrating cells on fast-relaxing IPNs are rounded, reminiscent of amoeboid migration45. However, these rounded cells lack blebs, a feature of amoeboid migration, and instead display filopodia protrusions. It is likely the case that the rounded cells we observe are different from conventional amoeboid migration observed in 3D migration models where cells are mechanically confined45. The limited number of nascent adhesions formed does mirror the few weak adhesions observed in migration of leukocytes, lymphocytes, dendritic cells, and neutrophils on 2D substrates10,46. However, these immune cells migrate at much greater speeds and filopodia have not been implicated in their migration, suggesting that the migration modes are distinct. Our results are contrary to previous reports that rounded, weakly adhesive cells are not detected in 2D migration models46. Surprisingly, we find that rounded cancer cells on soft, fast-relaxing IPNs can migrate faster on average than those cells on glass. On the whole, our findings implicate substrate stress relaxation as an important substrate variable to be included in 2D cell migration models.

Although, the present study was conducted in 2D, the key findings provide a platform to further investigate labile adhesions and filopodia extensions observed in physiologically relevant 3D environments. Specifically, the migration model described here might provide a platform to study several aspects of cancer progression in vivo. For instance, there is strong evidence that filopodia may play a key role in cancer invasion and metastasis36,47, suggesting the potential relevance of this mode of migration in vivo. In this regard, our findings have some relevance. Our results raise the possibility that, in vivo, longer filopodia facilitate invasion of surrounding tissue19. Furthermore, the increase in filopodia number might enhance cell migration and greater exploration of the environment. In addition, in vivo evidence implicates formin and fascin, key mediators of filopodia formation, in a variety of cancers36. Also, Mena, a protein implicated in filopodia formation has oncogenic potential and contributes to chemoresistance and extravasation48–50. Therefore, these results provide a fresh perspective on filopodia regulation that might be critical to cancer progression.

Methods

Cell culture and reagents.

Human breast cancer adenocarcinoma cells MDA-MB-231 (ATCC), and human fibrosarcoma cells HT-1080 (ATCC) were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone), and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Life Technologies). MCF-10A cells obtained from the ATCC were cultured in DMEM/F12 50/50 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 5% horse serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 20 ng/ml EGF (Peprotech, Inc.), 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma), 100 ng/ml cholera toxin (Sigma), 10 μg/ml insulin (Sigma), and 100 U/ml Pen/Strep (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as previously described51. Cells were cultured in a standard humidified incubator at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were maintained at sub-confluency and passaged every 2–3 days.

RNA interference experiments.

Pooled siRNAs targeting human Fascin1 and Myosin X, and a non-targeting control were obtained from Dharmacon. HT-1080 cells were transfected with DharmaFECT 1 according to manufacturer instructions. Briefly, 150,000 cells were seeded into each well of a 6-well plate and transfected with 10nM of siRNA in OptiMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 48hrs post transfection, cells were processed for live cell imaging or western blot analysis.

Western blotting.

HT-1080 cells were lysed in 25mM Tris pH 7.4, 100mM NaCl, 1%TritonX-100, 1mM EDTA with Halt Protease Inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific), concentrations were measured with Pierce 660nm Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and then boiled in SDS sample buffer. Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to Immobilon-FL membranes, and processed with chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Millipore). Raw western blot data provided in Supplementary Figure 8.

Hydrogel preparation.

Low molecular weight (MW) ultra-pure sodium alginate (Provona UP VLVG, NovaMatrix) was used for fast-relaxing substrates, with MW of <75 kDa, according to the manufacturer. Sodium alginate rich in guluronic acid blocks and with a high-MW (FMC Biopolymer, Protanal LF 20/40, High-MW, 280 kDa) was prepared for slow-relaxing substrates. High-MW alginate was irradiated 8 Mrad (8 × 106 rad) by a cobalt source to produce medium MW (70 kDa) alginate24. Alginate was dialyzed against deionized water for 3–4 days (MW cutoff of 3500 Da), treated with activated charcoal, sterile-filtered, lyophilized, and then reconstituted to 3.5 wt% in serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco). The use of low/medium/high molecular weight alginate resulted in fast/medium/slow-relaxing IPNs.

Hydrogel formation and cell seeding.

For each viscoelastic gel, alginate was delivered to a 1.5 mL eppendorf tube (polymers tube) and put on ice. Reconstituted basement membrane, rBM, (purchased from Corning), also on ice, was added to the alginate and carefully mixed 30 times with a pipette, being careful not to generate bubbles. For experiments with fiducial marker beads, 0.2 μm fluorescent dark-red microspheres were added at 100x dilution (ThermoFisher). Extra DMEM was added such that all substrates had a final concentration of 10 mg/mL alginate and 4.4 mg/mL rBM. This was mixed 30 times with a pipette. The mixture was kept on ice.

Next, different calcium sulfate concentrations were added to a 1 mL Luer lock syringe (Cole-Parmer), and kept on ice, to ensure that the initial Young’s modulus is kept constant for fast, medium, slow-relaxing substrates. The mixture of the polymers was transferred to a separate 1 mL Luer lock syringe (polymers syringe) and put on ice. The calcium sulfate solution was shaken to mix the calcium sulfate evenly, and it was then coupled to the polymers syringe with a female-female Luer lock (Cole-Parmer), taking care not to introduce bubbles or air in the mixture. Finally, the two solutions were rapidly mixed together with 30 pumps on the syringe handles and instantly deposited into a well in an 8-well Lab-Tek dish (Thermo Scientific) that had been pre-coated with rBM. The Lab-Tek dish was then transferred to a 37 °C incubator and allowed to gel for 1 h before media with cells was added to the well.

Polyacrylamide (PA) gels were made and functionalized according to a previous method35. First, 18 mm circular coverslips were cleaned with 1N ethanol and coated with sigmacote to make hydrophobic. A prepolymer solution was prepared containing acrylamide, N,N′-methylene-bis-acrylamide and degassed for 1 hour (fluorescent beads were added if used). The well where gels were to be deposited was activated with 3-methacryloxypropyl-trimethoxysilane for 5 minutes. This was done right before prepolymer was to be mixed with crosslinking reagents. Prior to gel formation, the prepolymer solution was mixed with 1/100 volume of 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS), and 1/1000 volume of N,N,N′,N′-Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED). 80 μl of the polymer mixture was deposited onto a 6-well plate with glass bottom and a cover slip was gently placed on top. When polymerization was completed, polyacrylamide gels were carefully separated from the coverslip. The final concentration of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide was varied to control substrate stiffness. For 2 kPa hydrogels, 4% /0.1% were used. For ~40 kPa hydrogels, 8% /0.264% were used. To enable cell adhesion to the PA gel, rBM was conjugated to the gel surface using sulfosuccinimidyl 6-(4′-azido-2′-nitrophenylamino)hexanoate (sulfo-SANPAH) as a protein-substrate linker. PA gels were incubated in 1 mg/ml sulfo-SANPAH in sterile water, activated with UV light (wavelength 365 nm, intensity 15W for 3.5 minutes, washed in calcium containing PBS (cPBS), and then incubated in 0.2 mg/ml rBM in cDPBS overnight. Excess protein was washed off with cPBS before use. All hydrogel formulations are described in Supplementary Table 1.

For 2D migration assays, cells were washed with PBS, trypsinized using 0.05% trypsin/EDTA, resuspended in growth media containing octadecyl rhodamine B chloride (R18, ThermoFisher, 1:1000 dilution of 10mg/ml stock), centrifuged, and re-suspended in growth media. The concentration of cells was determined using a Vi-Cell Coulter counter (Beckman Coulter) after passing through a 40 μM filter (Fisher Scientific) to obtain single cell suspensions. Cells were seeded on gels 1 h after gels were made. The final concentration of cells was 4,500 cells/cm2 in each well.

Mechanical characterization of IPNs.

Rheology testing was done with a stress-controlled AR2000EX rheometer (TA instruments). IPNs for rheology testing were deposited directly onto the bottom Peltier plate. A 25 mm flat plate was then slowly lowered to contact the gel, forming a 25 mm disk gel. Mineral oil (Sigma) was applied to the edges of the gel to prevent dehydration. For modulus measurement, a time sweep was performed at 1 rad/s, 37 °C, and 1% strain for 3 h after which the storage and loss moduli had equilibrated. Young’s modulus (E) was calculated, assuming a Poisson’s ratio (ν) of 0.5, from the equation:

| (1) |

where complex modulus, G*, was calculated from the measured storage (G’) and loss moduli (G”) using:

| (2) |

For stress relaxation experiments, the time sweep was followed by applying a constant strain of 5% to the gel, at 37 °C, and the resulting stress was recorded over the course of 3 h. For plasticity measurements, the time sweep was followed by a creep-recovery test where a 100 Pa stress was applied to the gel and the resulting strain was measured over 1 h. The sample was then unloaded (0 Pa) and the strain was measured over an additional 2 h. The stress relaxation and creep-recovery results establish that the gels behave like viscoelastic solids.

Immunofluorescence for fixed cells.

For immunofluorescence (IF) analysis, cells were seeded on gels as previously described. After 24 h, media were removed from the gels. 3 drops of low-melting temperature agarose was added to each well to prevent gel floating due to subsequent steps. The gels were washed once with serum-free DMEM then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in serum-free DMEM, at room temperature, for 20 min. The gels were then washed, three times, with calcium containing PBS (cPBS) for 10 min each time. After this, cells were permeabilized with a permeabilizing solution for 15 min, and washed two times with cPBS, 5 min each time. Blocking solution was then added to minimize non-specific staining. The final steps were addition of the primary antibody overnight at room temperature, wash two times with cPBS, addition of the secondary antibody at room temperature for 1.5 h, and a final cPBS wash. ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Life Technologies) was added right before imaging to minimize photobleaching. Images were acquired with a Leica 25x objective.

The following primary antibodies were used: anti-paxillin antibody Y113 (1:500, Abcam ab32084), anti-focal adhesion kinase (1:500, ThermoFisher 700255), anti-myosin light chain, phosphor-specific S19 (1:250, EMD Millipore AB3381), anti-myosin-X (1:250, Novus Biologicals 22430002), anti-VASP (1:100, Origene TA502647). Matching secondary antibodies purchased from Life Technologies were used. Alexa Fluor 488 phallodin was used to label actin (1:80, Life Technologies), and DAPI was used to label the nucleus (1:500, Sigma).

Confocal microscopy.

All microscope imaging was done with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica SP8) fitted with temperature/incubator control, suitable for live-imaging (37°C, 5% CO2). In live-cell time-lapse imaging, R18 membrane labeled cells were tracked with a 10x NA = 0.4 air objective for 24 hours. A 25x NA = 0.95 water-matched objective was used for experiments with fluorescent beads, immunofluorescence imaging and for siR-actin labeled cells experiments for filopodia analysis. For live-cell time lapse imaging, 60 μm stack images were acquired every 10 minutes and imaging parameters were adjusted to minimize photobleaching and avoid cell death. Whereas for siR-actin imaging for filopodia analysis, 15 μm stack images were acquired every 1 minute after it was determined that this imaging frequency did not cause cell death. Gels were inverted to obtain high resolution filopodia and lamellipodia images. Briefly, HT-1080 cells were seeded on fast and slow-relaxing gels and allowed to spread overnight in a 4-well Lab-Tek chamber (Thermo Scientific) with removable wells. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated with siR-actin for 5 hours. Next, the Lab-Tek wells were removed, and a rectangular coverslip was gently placed over the gel. The assembly was flipped, and cells were imaged through the coverslip using a 25x NA = 0.95 water-immersion objective.

Morphometric and traction stress analysis.

To quantify cell circularity and cell area, confocal images from R18 labeled cells were analyzed in ImageJ to calculate circularity and cell area. Circularity, mathematically calculated as 4π*area*(perimeter)−2, ranges from 0 to 1 with a value of 1 being a perfect circle. For speed vs circularity plots, randomly selected cells were manually tracked. The corresponding instantaneous speed and circularity was determined using ImageJ’s default algorithm. In cell migration simulation, cell aspect ratio is defined as the ratio of longest axis to shortest axis, and cell area is determined as the area of the ellipse that best fits the cross section of the cell.

For matrix displacement analysis, bead displacement obtained from confocal imaging was converted to matrix displacement fields following established protocols4,52. Briefly, isolated, single cells that produced observable beads displacement were used for the analysis. Cell and bead channel images, from a single z-plane, were corrected for drift using the StackReg ImageJ plugin. Next, the particle image velocimetry (PIV) ImageJ plugin was used to perform a PIV analysis on the beads data. PIV algorithm maximizes the cross-correlation between relaxed and strained images. A 2-pass PIV with a 128 × 64 pixel size was used on all images for the PIV analysis. The resulting analysis produced the position and vector field of the beads displacement. Custom MATLAB code was used to visualize the vector fields and heat maps.

Imaris cell tracking algorithm.

For migration studies, the centroids of R18-labeled cells were tracked using the spots detection functionality in Imaris (Bitplane). Poorly segmented cells and cell debris were excluded from the analysis and drift correction was implemented where appropriate. A custom MATLAB script was used to reconstruct cell migration trajectory.

Inhibition studies.

Pharmacological inhibitors were added to cell media 10 minutes before time-lapse microscopy experiments. The concentrations used for the inhibitors are: 100 nM Latrunculin A (Tocris Bioscience, actin polymerization inhibitor), 70 μM NSC 23766 (Tocris Bioscience, Rac 1 inhibitor), 50 μM CK 666 (Sigma, Arp 2/3 inhibitor), 20 μM ML141 (Tocris, Cdc 42 GTPase inhibitor), 20 μM SMIFH2 (Sigma, formin inhibitor), 30 μM fascin-G2 (Xcess Biosciences Inc., fascin inhibitor), 50 μM Y-27632 (Sigma, ROCK inhibitor) 25 μM ML-7 (Tocris, myosin light chain kinase inhibitor), 2 μg/ml CD29 Monoclonal Antibody TS2/16 (Life Technologies, β1-integrin activator), and 5 μg/ml monoclonal β1-integrin-blocking antibody (Abcam, P5D2). For HT-1080 cell detachment studies, cells were seeded on fast and slow-relaxing gels and allowed to spread overnight. 10 μg/ml monoclonal β1-integrin-blocking antibody was added to media and live-cell imaging started. Images were acquired every 2 minutes for 12 hours.

Calcium imaging.

To quantify the relative level of intracellular calcium depending on the substrate type, ratio-metric calcium imaging was applied with two intracellular calcium indicators -- Fluo-3 AM (20 μM, ThermoFisher Scientific) and Fura-red AM (33 μM, ThermoFisher Scientific)53. HT-1080 cells were incubated in both dyes for 1 hr and washed twice with DPBS. Live-cell confocal microscopy was used to measure the intensity of calcium indicators in cells. Both calcium indicators were excited at 488nm and respectively detected at 515–580 nm (Fluo-3) and >610nm (Fura-red) to measure the fluorescent intensities. The relative level of intracellular calcium was measured as the intensity ratio of Fluo-3 to Fura-red.

Statistics and reproducibility.

All measurements were performed on 1–3 biological replicates from separate experiments. Exact sample size and exact statistical test performed for each experiment is indicated in appropriate figure legends. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, California). For all violin plots, broken lines are median values. For scatter plots, solid lines are median values. P-values reported were corrected for multiple comparisons, where appropriate. Additional information about statistical tests is provided in Supplementary Table 2. All immunofluorescence and live-actin experiments images were performed over 3 independent experiments.

Cell migration simulation based on motor-clutch framework

The primary components of the mechano-sensing apparatus in cells are actin-myosin (motor) and cell-ECM adhesion (clutch), also known as the motor-clutch module, whose dynamics have successfully explained stiffness sensing of cells on elastic substrates17,21. In the motor clutch module, myosin motors pull the F-actin towards cell center and form an actin retrograde flow. This retrograde flow is resisted by adhesion molecules, which can randomly bind and unbind between actin bundles and ECM. At the cell leading edge, the polymerization of actin filaments, countered by retrograde flow, pushes the cell membrane forward, further resulting in the protrusion of the cell. To account for the viscoelasticity of ECM, a standard linear viscoelastic solid (SLS) model that contain three elements: long-term modulus, additional modulus, and viscosity, is applied. For a cell to migrate, the symmetry or velocity balance between cell’s ends has to be broken by the stochastic dynamics of clutches. Hence, two or more motor-clutch modules can be connected, and their forces are balanced at the cell center.

We first applied the 2D cell migration simulator (CMS), which is composed of multiple motor-clutch modules to test cell migration differences on soft fast and slow-relaxing viscoelastic substrates, and soft and stiff elastic substrates (Supplementary Notes). To further study the symmetry breaking associated with cell migration and gain mechanistic insights, we simplified into two connected motor-clutch modules in a one-dimensional model (Supplementary Notes). The dynamics of each motor-clutch module can also be used to characterize filopodia dynamics21. Filopodia lifetime is defined as the time elapsed from the initial attachment of clutches to the catastrophic breakage of the entire clutch cluster which leads to filopodia retraction. Simulation parameters are in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4. CMS simulations were carried out with custom C++ code, and one-dimensional simulations were carried out in MATLAB. Details on the formulations and algorithms used can be found in Supplementary Notes.

Data availability.

All data relevant to this manuscript are available upon request.

Code availability.

All analyses codes relevant to this manuscript have been deposited in the DOI-minting repository Zenodo54. Simulation codes are available upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We acknowledge Dr. Ryan Stowers (University of California, Santa Barbara) and the Chaudhuri lab for helpful discussion and Marc Levenston (Stanford University) for use of mechanical testing equipment. We also acknowledge the Stanford Cell Sciences Imaging Facility for Imaris software access and for technical assistance with Imaris. Fig. 5n was schematic created with BioRender.com. K.A. acknowledges financial support from the Stanford ChEM-H Chemistry/Biology Interface Predoctoral Training Program and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32GM120007, and a National Science Foundation Graduate Student fellowship. D.G. was funded in part by National Institutes Health Fellowship Award Number GM116328. This work was supported by an American Cancer Society grant (RSG-16–028-01) and National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute Grant (R37 CA214136) for O.C., NIH NCI grant U54 CA210190 for D.J.O., and the NSF Center for Engineering Mechanobiology (CMMI-154857) through grants NSF MRSEC/DMR-1720530 R01CA232256, National Cancer Institute Awards U01CA202177, NIH U54-CA193417 and R01EB017753 for V.B.S.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References:

- 1.Ridley AJ et al. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science 302, 1704–1709, doi: 10.1126/science.1092053 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauffenburger DA & Horwitz AF Cell migration: a physically integrated molecular process. Cell 84, 359–369 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shafqat-Abbasi H et al. An analysis toolbox to explore mesenchymal migration heterogeneity reveals adaptive switching between distinct modes. Elife 5, e11384, doi: 10.7554/eLife.11384 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wisdom KM et al. Matrix mechanical plasticity regulates cancer cell migration through confining microenvironments. Nat Commun 9, 4144, doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06641-z (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf K et al. Physical limits of cell migration: control by ECM space and nuclear deformation and tuning by proteolysis and traction force. J Cell Biol 201, 1069–1084, doi: 10.1083/jcb.201210152 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haston WS, Shields JM & Wilkinson PC Lymphocyte locomotion and attachment on two-dimensional surfaces and in three-dimensional matrices. J Cell Biol 92, 747–752, doi: 10.1083/jcb.92.3.747 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamada KM & Sixt M Mechanisms of 3D cell migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20, 738–752, doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0172-9 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reversat A et al. Cellular locomotion using environmental topography. Nature, doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2283-z (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hons M et al. Chemokines and integrins independently tune actin flow and substrate friction during intranodal migration of T cells. Nat Immunol 19, 606–616, doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0109-z (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedl P & Wolf K Plasticity of cell migration: a multiscale tuning model. J Cell Biol 188, 11–19, doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909003 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xue F, Janzen DM & Knecht DA Contribution of Filopodia to Cell Migration: A Mechanical Link between Protrusion and Contraction. Int J Cell Biol 2010, 507821, doi: 10.1155/2010/507821 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacquemet G, Hamidi H & Ivaska J Filopodia in cell adhesion, 3D migration and cancer cell invasion. Curr Opin Cell Biol 36, 23–31, doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.06.007 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacquemet G et al. Filopodome Mapping Identifies p130Cas as a Mechanosensitive Regulator of Filopodia Stability. Curr. Biol 29, 202–216 e207, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.11.053 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charras G & Sahai E Physical influences of the extracellular environment on cell migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15, 813–824, doi: 10.1038/nrm3897 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim DH & Wirtz D Predicting how cells spread and migrate: focal adhesion size does matter. Cell Adh Migr 7, 293–296, doi: 10.4161/cam.24804 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pathak A & Kumar S Independent regulation of tumor cell migration by matrix stiffness and confinement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 10334–10339, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118073109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bangasser BL et al. Shifting the optimal stiffness for cell migration. Nat Commun 8, 15313, doi: 10.1038/ncomms15313 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oakes PW et al. Lamellipodium is a myosin-independent mechanosensor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 115, 2646–2651, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715869115 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liou YR et al. Substrate stiffness regulates filopodial activities in lung cancer cells. PLoS One 9, e89767, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089767 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong S, Guo WH & Wang YL Fibroblasts probe substrate rigidity with filopodia extensions before occupying an area. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, 17176–17181, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412285111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan CE & Odde DJ Traction dynamics of filopodia on compliant substrates. Science 322, 1687–1691, doi: 10.1126/science.1163595 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lo CM, Wang HB, Dembo M & Wang YL Cell movement is guided by the rigidity of the substrate. Biophys J 79, 144–152, doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76279-5 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levental I, Georges PC & Janmey PA Soft biological materials and their impact on cell function. Soft Matter 3, 299–306, doi: 10.1039/B610522J (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaudhuri O et al. Hydrogels with tunable stress relaxation regulate stem cell fate and activity. Nat Mater 15, 326–334, doi: 10.1038/nmat4489 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nam S et al. Cell cycle progression in confining microenvironments is regulated by a growth-responsive TRPV4-PI3K/Akt-p27(Kip1) signaling axis. Science Advances 5, doi:ARTN eaaw6171 10.1126/sciadv.aaw6171 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charrier EE, Pogoda K, Wells RG & Janmey PA Control of cell morphology and differentiation by substrates with independently tunable elasticity and viscous dissipation. Nat Commun 9, 449, doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02906-9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gong Z et al. Matching material and cellular timescales maximizes cell spreading on viscoelastic substrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 115, E2686–E2695, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716620115 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaudhuri O et al. Extracellular matrix stiffness and composition jointly regulate the induction of malignant phenotypes in mammary epithelium. Nat Mater 13, 970–978, doi: 10.1038/nmat4009 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cameron AR, Frith JE & Cooper-White JJ The influence of substrate creep on mesenchymal stem cell behaviour and phenotype. Biomaterials 32, 5979–5993, doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.003 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nam S & Chaudhuri O Mitotic cells generate protrusive extracellular forces to divide in three-dimensional microenvironments. Nat Phys 14, 621–628, doi: 10.1038/s41567-018-0092-1 (2018). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee HP, Gu L, Mooney DJ, Levenston ME & Chaudhuri O Mechanical confinement regulates cartilage matrix formation by chondrocytes. Nat Mater 16, 1243–1251, doi: 10.1038/nmat4993 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaudhuri O et al. Substrate stress relaxation regulates cell spreading. Nat Commun 6, 6364, doi: 10.1038/ncomms7365 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelley LC, Lohmer LL, Hagedorn EJ & Sherwood DR Traversing the basement membrane in vivo: a diversity of strategies. J Cell Biol 204, 291–302, doi: 10.1083/jcb.201311112 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen MB, Whisler JA, Jeon JS & Kamm RD Mechanisms of tumor cell extravasation in an in vitro microvascular network platform. Integr Biol (Camb) 5, 1262–1271, doi: 10.1039/c3ib40149a (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tse JR & Engler AJ Preparation of hydrogel substrates with tunable mechanical properties. Curr Protoc Cell Biol Chapter 10, Unit 10 16, doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb1016s47 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arjonen A, Kaukonen R & Ivaska J Filopodia and adhesion in cancer cell motility. Cell Adh Migr 5, 421–430, doi: 10.4161/cam.5.5.17723 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaidel-Bar R, Milo R, Kam Z & Geiger B A paxillin tyrosine phosphorylation switch regulates the assembly and form of cell-matrix adhesions. J Cell Sci 120, 137–148, doi: 10.1242/jcs.03314 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bangasser BL, Rosenfeld SS & Odde DJ Determinants of maximal force transmission in a motor-clutch model of cell traction in a compliant microenvironment. Biophys J 105, 581–592, doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.06.027 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heckman CA & Plummer HK Filopodia as sensors. Cell Signal 25, 2298–2311, doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.07.006 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albuschies J & Vogel V The role of filopodia in the recognition of nanotopographies. Sci Rep 3, 1658, doi: 10.1038/srep01658 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubiano A et al. Viscoelastic properties of human pancreatic tumors and in vitro constructs to mimic mechanical properties. Acta Biomater 67, 331–340, doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.11.037 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaudhuri O, Cooper-White J, Janmey PA, Mooney DJ & Shenoy VB Effects of extracellular matrix viscoelasticity on cellular behaviour. Nature 584, 535–546, doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2612-2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nam S et al. Cell cycle progression in confining microenvironments is regulated by a growth-responsive TRPV4-PI3K/Akt-p27(Kip1) signaling axis. Sci Adv 5, eaaw6171, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw6171 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sinkus R et al. High-resolution tensor MR elastography for breast tumour detection. Phys Med Biol 45, 1649–1664 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu YJ et al. Confinement and low adhesion induce fast amoeboid migration of slow mesenchymal cells. Cell 160, 659–672, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.007 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedl P & Wolf K Tumour-cell invasion and migration: diversity and escape mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer 3, 362–374, doi: 10.1038/nrc1075 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacquemet G et al. L-type calcium channels regulate filopodia stability and cancer cell invasion downstream of integrin signalling. Nat Commun 7, 13297, doi: 10.1038/ncomms13297 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu K et al. Mammalian-enabled (MENA) protein enhances oncogenic potential and cancer stem cell-like phenotype in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. FEBS Open Bio 7, 1144–1153, doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12254 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oudin MJ et al. MENA Confers Resistance to Paclitaxel in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 16, 143–155, doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0413 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harney AS et al. Real-Time Imaging Reveals Local, Transient Vascular Permeability, and Tumor Cell Intravasation Stimulated by TIE2hi Macrophage-Derived VEGFA. Cancer Discov 5, 932–943, doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0012 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee JY et al. YAP-independent mechanotransduction drives breast cancer progression. Nat Commun 10, 1848, doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09755-0 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poincloux R et al. Contractility of the cell rear drives invasion of breast tumor cells in 3D Matrigel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 108, 1943–1948, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010396108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee HP, Stowers R & Chaudhuri O Volume expansion and TRPV4 activation regulate stem cell fate in three-dimensional microenvironments. Nat Commun 10, 529, doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08465-x (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adebowale K Gong Z, Hou JC, Wisdom KM, Garbett D, Lee HP, Nam S, Meyer T, Odde DJ, Shenoy VB,Chaudhuri O (2021). Zenodo DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4562343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to this manuscript are available upon request.