Abstract

Today’s working population is expected to experience a longer and healthier life than previous generations did. This, combined with a currently shrinking workforce, means the participation of older adults in the labor market is expected to positively contribute to national economic and social development. Policymakers have therefore implemented a series of reforms to motivate and encourage both employers and employees to embrace the prospect of an aging workforce and to respond to the associated challenges of such a demographic change in the workplace. This paper aims to provide an overview of recent policy initiatives in this context and to identify the role of technology in major international initiatives in overcoming the key challenges faced by developed countries. We have conducted a scoping review to obtain large volumes of peer-reviewed and gray literature. Our findings suggest that the stakeholders (researchers, government agencies, employers, and communities) are not only aware of the current issues relating to the aging population but also understand the importance of policies in terms of retaining older people in the workforce. In particular, our results indicate that technology, in both the public and private sectors, can be leveraged as a tool to facilitate older adults’ participation in the workforce.

Keywords: Aging workforce, Challenges, Policy initiatives, Potential impact, Technological contribution

Introduction

The ongoing growth in today’s aging population has been identified as one of the most significant social and economic issues of the twenty-first century to date and is likely to have financial and social implications for the sustainability of public welfare systems throughout the world. Despite the popular image of the wealthy baby boomer, many individuals face increasing financial hardship as they grow older (Hoffman & Jackson, 2013; Radović-Marković, 2013), often accompanied by anxiety about running out of money in their pension funds. Furthermore, as the baby boomers of this country have entered retirement, there has been a concurrent drop in taxable incomes, which in turn has negatively affected government revenues. As the older population continues to grow, so too does the burden on the shrinking working population, which plays a significant role in providing the social and economic support that contributes to the well-being of the older population in their later years (Lindh, 2004; Navaneetham & Dharmalingam, 2012; Schuring et al., 2013). This dependency ratio is expected to significantly influence the welfare system from a multidimensional perspective (e.g., community, family and institution) (Lindh, 2004; Navaneetham & Dharmalingam, 2012; Hoffman & Jackson, 2013; Radović-Marković, 2013; Schuring et al., 2013).

The well-being of an older person is determined by their social and economic status, and so encouraging older people to maintain a long working life is likely to be an effective way of improving their financial security (Carmichael & Ercolani, 2015; Finch, 2014; Schuring et al., 2013). Furthermore, thanks to advancements in both science and technology, 60 is no longer considered “old,” and there are more options to remain active in the workforce beyond this age (Ng & Feldmann, 2008, 2012; Radović-Marković, 2013). Retaining older workers in the workforce is therefore essential not only in overall economic terms—that is, full employment—but also in terms of equipping older adults financially for their later years. Aging workers are also an incredibly rich resource, given their valuable skill sets, experience, and commitment, and their ongoing involvement in the workforce is expected to increase overall national productivity (Carmichael & Ercolani, 2015). However, the reality of retaining senior workers in the workforce can be difficult because they are often challenged by health issues and out-of-date technological knowledge (Nagarajan et al., 2019).

Taking into consideration the impact and opportunity of an aging population on economic development, the ultimate plan of many government agencies is to retain older workers in the labor force. However, motivating older people to remain in the workforce for longer than they may have anticipated appears to be a complex task (Axelrad et al., 2013). Hence, implementing strategies such as creating an age-friendly work environment, offering ongoing training, exploiting task automation, using ergonomics to improve working conditions, and offering a flexible work environment, including promoting teleworking and frequent rest breaks, could motivate the older population to remain in the workforce (Nagarajan et al., 2019; Radović-Marković, 2013).

Considering the challenges of retaining aging workers in the workforce, this study aims to: i) analyze the policy initiatives regarding retention of the aging workforce, ii) discuss the potential impact of the policies in terms of social, economic, and scientific factors, and iii) examine the role of technology and innovation in addressing the challenges faced by aging workers.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: “The Demographic Transition” contains a discussion of the current demographic crisis, the implications of an aging population, and the challenges of retaining older workers in the workforce. “Methodological Consideration” describes the methodology employed for this study, “Analysis of the Result” discusses in detail the policy initiatives, their potential impact on economic, social, and scientific factors, “Recent Developments in the Workforce for Older Workers” studies recent developments in the workforce for older workers, and “Opportunities for Applying Technology and Innovation to Meet the Needs of an Aging Workforce” identifies opportunities for applying technology and innovation to meet the needs of an aging workforce. In “Conclusion and Future Work” we present our conclusions and discuss our plans for future work.

The Demographic Transition

Overview

The current demographic transition means the world has older people than ever before. This unprecedented and ongoing proportional increase in the aging population across the globe is therefore receiving considerable attention from researchers and policymakers, who have identified a drop in fertility rates and consistent increases in life expectancy as the prime reasons for this rise in the aging population.

The Significance of the Demographic Transition

Globally, age profiles are undergoing a unique transformation due to rising life expectancies and falling fertility rates (Brooks, 2003). The resultant imbalance in the age structure means a large part of the working-age population in Canada will be aged 65 years (and over) between 2010 and 2030 (Beach, 2008). As a result, like most developed countries, Canada most probably faces a labor crisis (Fougère et al., 2009; Sharpe, 2011).

The influence of aging on labor market participation is an economic concern, as the production levels of a country are intrinsically dependent on the involvement of workers in the workforce (Siliverstovs et al., 2011). The consistent increase in the aging population in comparison to the working-age population is likely to reduce the labor supply—leading not only to a rise in labor costs but also a fall in overall production (Lisenkova et al., 2012). Therefore, the impact will be more profound for a country that is highly dependent on labor-intensive sectors (Lisenkova et al., 2012). For instance, Maestas et al. (2016) predicted that a 10% rise in the population aged 60 and over will reduce the growth rate per capita of the USA by 5.5%. They further explained that two-thirds of this reduction in economic growth would be due to a drop in the growth of labor productivity, and the other third would be the result of slower growth in the labor force. Hence, it is evident that the rising aging population is likely to affect the dynamics of the labor market and will eventually decrease the economic growth of a country.

The growing aging population is expected to influence governments’ budget planning. For instance, despite investing in financial capital for economic development, governments will have to concentrate more on allocating revenue to meet the various needs of the senior population (Lisenkova et al., 2012). Eiras and Niepelt (2012) and Lisenkova et al. (2012) note that the significant rise in the aging population would see increases in government spending on social security rather than on education and infrastructure investment. For instance, in Canada, the average annual per capita health care cost for those age 65 and above was $11,625—almost 4.4 times the cost per capita for people in the 15–64 age group (Jackson et al., 2017). A change of this nature in a government’s spending priorities can cause a nation to experience an interruption in its economic progress. For instance, with its growing older population and shrinking working population, Germany’s pay-as-you-go system is no longer considered an effective pension plan approach (Muller, 2018). In fact, to overcome the pension crisis, the German Health minister, Jens Spahn, has suggested that people without children should consider paying more toward care and pension insurance than those with children (Muller, 2018).

According to Dick (2012), the number of retirees in the German labor force has doubled in the past decade, with nearly 17 million retirees being forced to participate in the workforce due to inadequate pension funds. Thus, it is clear that, despite the government’s policy to increase the retirement age to overcome labor shortages, the financial constraints faced by the older population influence their decision to remain in the workforce.

However, researchers believe that without defining and addressing the challenges faced by older workers, any policy that increases the retirement age will be ineffective in overcoming the economic development consequences of an aging population (Nagarajan et al., 2019). Therefore, in the following subsection, we identify and discuss the challenges of retaining older workers in the workforce.

The Challenges of Retaining Older Workers in the Workforce

Retaining older workers in the workforce and simultaneously protecting their well-being is seen as a major challenge. The senior population is, of course, as heterogeneous as the workplace, and so initiating policies such as raising the retirement age is likely to increase the level of challenges, as each sector has different work environments and preferences (Axelrad et al., 2013).

According to Lazear (1979), the mandatory retirement age process is designed around “a date at which the contract is terminated and the worker is no longer entitled to receive a wage greater than his VMP [value of marginal product]” (Lazear, 1979, p. 1283). Thus, current reforms to retirement policy—in this example, retaining aging workers in the workforce—mean a company is expected to pay a wage “greater than VMP.” The 2009 ASPA (Activating Senior Potential in Ageing Europe) survey, in the Netherlands, revealed that 75% of employers expect their labor costs to increase because of the growing aging workforce (Conen et al., 2011). Van Dalen et al. (2010) discovered that both employers and employees of Dutch companies and organizations rate the productivity of older workers as substantially lower than that of younger workers. Hence, employers equate having aging workers in an organization with a rise in costs (e.g., more sick leave) and drop in productivity (e.g., because of a reluctance to learn new technologies) (Van Dalen et al., 2010; Conen et al., 2011; Nagarajan et al., 2019) and so would not favor hiring aging workers over other options. According to Conen et al. (2011), 33% of employers in Germany prefer to have their existing staff work longer hours rather than hire older workers.

For their part, aging workers have expressed a belief that their physical fitness, cognitive status, and knowledge of new technology are obstacles to their ongoing participation in the workforce (Nagarajan et al., 2019). This belief is reinforced by various external actors (Lisenkova et al., 2012), and many employers feel that older workers will raise production costs rather than contribute positively (Mahlberg et al, 2013; Rocha, 2017; van Ours & Stoeldraijer, 2010). For instance, in Austria, the productivity level of aging workers in the manufacturing, financial, transport, and communication sectors was lower than that of their younger colleagues (Mahlberg et al., 2013). However, despite the potential fall in the productivity stemming from the hiring of aging workers, some employers are still willing to hire older adults, albeit for less money than the older adults may have expected (van Ours & Stoeldraijer, 2010). In the Netherlands, for example, the majority of the older population is struggling to get back into the job market because they consider the wages they are being offered to be too low (van Ours & Stoeldraijer, 2010). The employers have a different perspective: given the older workers’ health status and potential obsolescence of their knowledge and skills, they believe that the wages being demanded by older candidates do not reflect their capability (van Ours & Stoeldraijer, 2010). Long spells of unemployment among older workers have a twofold effect: they are likely to weaken the morale of older workers, conscious of their potential skills deficit, seeking employment (Klehe et al., 2012) and organizations may find it difficult to find older adults whose skills are both in demand and up to date (Klehe et al., 2012). Hence, the most challenging tasks for the policymakers will be to understand the obstacles faced by employers in re-hiring retirees, identifying adequate and suitable training plans for the older generation to overcome skill obsolescence, and finding the right candidates for the job.

Low birth rates have resulted in fewer young employees, and will continue to do so for the next few decades. Many organizations have therefore been forced to hire or retain older employees, a trend that will continue (Dychtwald et al., 2004). However, researchers note that the increase in the older working population will mean an increase in the variation in age between co-workers (Boehm et al., 2011). The resultant wider generation gap in the workforce is expected to result in increased tensions and disputes between older and younger workers, which will affect overall productivity (Nagarajan et al., 2019). For instance, a recent representative survey carried out in the UK revealed that 2,235 people aged 50 years and over had experienced age discrimination in their workplace (Department of Work & Pensions, 2015).

Most organizations are facing challenges in adhering to government policy and employing workers older than the previously mandated retirement age, and one of the recurring problems is how to integrate a wide range of age groups in an organization (Boehm et al., 2011). If employers are to retain older workers in order to overcome labor shortages, they need to understand how different generations operate in organizations. Thus, a major challenge for any organization planning to employ older workers will be how to design and promote an age-friendly work environment for senior workers while considering the needs of younger workers as well (Nagarajan et al., 2019). Employers who are willing to hire older workers often also encounter challenges from human resources staff in terms of how to educate younger supervisors/managers about the importance of supporting older workers by providing equal opportunities to older workers as a way to counteract the generation gap in the workforce (Armstrong-Stassen & Schlosser, 2011).

Skill obsolescence is often identified as the main reason for the decline in performance of older workers, and the majority of older workers receive less encouragement from their generally younger supervisors to participate in training to improve their skills (Ravichandran et al., 2015). Consequently, most aging workers’ difficulty in adopting new technical skills can be traced to having had fewer opportunities to access training. This gives rise to the challenge of educating younger supervisors about what comprises an “age-friendly work environment” and the significance of giving older workers access to skills training.

It appears that, even though policymakers, employers, and young workers acknowledge the potential of older workers to contribute to economic development and encourage their participation in the labor market, the older workers’ willingness to adapt to changes in the workforce is often questioned. According to Liang and Luo (2017), most of the older adults in their study faced difficulties in adapting to changes and consistently stuck to their past practices and values, which were often considered out of date.

Methodological Consideration

An aging population is likely to influence every aspect of life in a country, including demands on the healthcare system, governmental financial planning, education, economic progress, labor market stability, socio-cultural conditions, and family life. For this particular research study, our focus is on the labor market aspect, and specifically the role of institutions in assisting the older population in the workforce and the potential role of technology in assisting older workers.

There are systematic narrative review methods (e.g., scoping review, bibliometrics, environmental scanning, and traditional literature review) available to capture and extract key information from published works—however, each of these review methods is conducted for a different purpose. For instance, bibliometrics is used to analyze and quantify peer-reviewed articles statistically, whereas a traditional literature review is used to review published articles from accredited scholars and researchers (Nagarajan et al., 2019). Since bibliometrics and a traditional literature analysis both exclude gray literature1 and gray literature is essential for our study as it includes policy documents and organizational reports, neither of these two approaches was considered appropriate for our study. A scoping review appeared to be a more appropriate method for our purposes, as this method both reviews published articles from accredited scholars and researchers and includes gray literature. Scoping reviews conducted to analyze the policy initiatives aimed at addressing the aging workforce issues, discuss the potential impact of the policies on the development of social, economic, and scientific, and finally, examine the role of technology in addressing aging workers’ challenges. To further explore the challenges of an aging workforce and the related policy implementation, we conducted the scoping review to obtain large volumes of peer-reviewed and gray literature to: i) identify the factors that influence the older population’s decision to remain in the workforce, ii) policy initiatives, and iii) discuss the potential role of technology in supporting an older workforce.

To retrieve peer-reviewed articles, we used the Elsevier SciVerse Scopus database. There are three main databases available for extracting peer-reviewed articles—ISI Web of Science (WOS), Google Scholar (GS), and Scopus (Nagarajan et al., 2015)—but the consistency, availability of information, and frequent updates of search results (Adriaanse & Rensleigh, 2013; Falagas et al., 2008; Norris & Oppenheim, 2007) of Scopus made it our preferred option. To search the database, we used the following keywords in the “keywords”, “article title”, and “abstract” fields: “older workers”, “older workers AND technology”, “older workers AND productivity”, or “ageing population AND employment”. We focused our search on the period 2008–2018, and limited it to articles written in English, in the domains of the social sciences and the humanities. We decided to use the term “older workers” as a keyword because it is the most frequently used term to describe older employees (Nagarajan et al., 2019). All the articles were assessed by a review of their titles, abstract, and main content. This yielded 113 articles that we could use for our study (see Appendix: A1); 224 articles were excluded since their focus was not related to our study (e.g., migration, female labour participation).

Gray literature is vital because it includes policy documents and organizational reports (Nagarajan et al., 2019), both of which are important for a study related to the aging workforce. Our gray literature search focused on obtaining information on policy initiatives by both governments and non-governmental organizations. We used the keywords “policy guide for older workers”, “older workers and challenges”, and “technology and older workers” as the search criteria in the Google search database. Our search result yielded 60 data sets (see Appendix: A2) on policy initiatives by several developed countries, and from international organizations.

In addition to peer-reviewed journals and gray literature, we expanded our analysis by using data collected from several Canadian research teams with expertise in the field of aging-related policy: the STAR Institute (Science and Technology for Aging Research),2 New Brunswick AGE-WELL NCE (Aging Gracefully across Environments using Technology to Support Wellness, Engagement and Long Life NCE Inc.),3 and The Advancing Policies and Practices in Technology and Aging (APPTA).4

Analysis of the Result

General Considerations

As discussed above, our research focused primarily on conducting a review of the policy initiatives aimed at sustaining older workers in the labor market and identifying the potential role of technology in implementing such policies. For this study, we reviewed academic journals and policy documents, as the main aim of our research is to examine the effectiveness of the policy initiatives, conduct case studies by examining the extent of the policy implementation in real-life scenarios, and identify the potential role of technology to help older workers perform well.

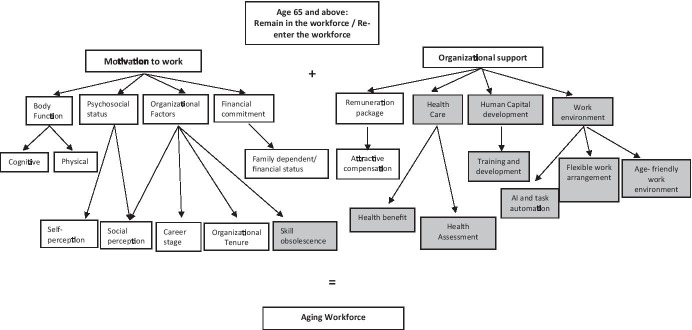

Taking into consideration the role of individuals and external factors, we intend to analyze the importance of policy implementation in sustaining older workers in the workforce. Based on the review of the 115 peer-reviewed articles we collected, we have identified possible factors (both individual and organizational) that are expected to influence the decision of an older population to remain in/re-enter the workforce (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Factors influence the decision of the older population to remain in the workforce (The grey shades refer to the potential integration of technology in the ageing workforce). Source: Authors own design based on the review of 115 articles via the Scopus database (Data was accessed on January 6, 2018)

In general, the review of the literature has identified that the choice of an older population to remain in the workforce depends on their motivation level and organizational support (See Fig. 1). From the reviewed literature we have further noted that the following factors play a vital role in motivating the older population to remain in the workforce: i) physical function, ii) psychosocial status, iii) organizational perceptions, and iv) financial commitments. For instance, the deteriorating health status of an older population is likely to dissuade them from participating in the labor market (Hertel & Zacher, 2018). Additionally, co-workers’ and employers’ perceptions of the older workers’ performance often influence older workers’ decisions about whether to remain in the workforce (Rego et al., 2017), and financial commitments, including a necessity to support themselves and their dependent family members, also exert an influence on any decision to remain in the workforce.

Much extant literature has discussed that the motivation level of older workers is often weakened by less supportive institutions (Axelrad et al., 2013; Ravichandran et al., 2015; Rego et al., 2017). Thus, beyond an individual’s decision making around remaining in the workforce, external factors such as a government’s policy implementation, organizations’ policies, working partners’ collaboration, family members’ support, and community encouragement all play an important role in the decision-making process. In terms of organizational support, factors such as remuneration packages, health care, human capital development, and work environment all play an important role. As skill obsolescence is one of the main influences on the continued participation of older workers, ongoing training and education are often seen as a way to engage the older population with technology (Armstrong-Stassen & Schlosser, 2011; Ravichandran et al., 2015). Figure 1 further explains that technology makes a higher contribution in assisting an organization in supporting older workers to remain in the workforce. Since technology is a key part of the work life of an individual (health care support, human capital development support, and work environment support), it is also necessary to introduce elements of innovation and technology diffusion policy to support an older workforce. Hence, the following section discusses in detail policy initiatives and the potential contribution of technology in retaining older workers in the workforce.

Policies That Promote the Participation of Older Workers

Most countries with an aging population, along with the OECD, World Bank, World Health Organization, and United Nations, focus on planning and implementing policies to prolong people’s working life. Since the current number of people aged 65 and over in the labor market is unprecedented, extending the working life of this age group is viewed as the most pressing challenge for policymakers around the world.

According to Laun et al. (2019), policy reform measures implemented in Norway, such as i) increasing the minimum retirement age, ii) increasing income taxes, iii) reducing retirement benefits, and iv) reducing retirement and disability benefits, have counteracted a labor shortage and contributed to national fiscal sustainability. They also resulted in a reduction in disability benefits claims by aging workers. In order to abide by the reform policies, employers frequently implemented flexible working hours and provided lifelong training to retain older workers, despite the increased costs of doing so. To take another example, in Denmark, 92% of employers support retirement reforms and allow part-time retirement or bridge employment (Conen et al., 2011).

The following subsection analyzes the policies upon which various initiatives are based and the extent to which both government and organizations implemented the retirement reforms.

Policy Initiatives

Developed countries are actively involved in drafting policy plans to ensure the ongoing participation of older workers in the labor force (Nagarajan et al., 2019; Gerontological Society of America (GSA), 2018; Eurofound, 2017; OECD, 2015). Following publication of the Live Longer, Work Longer report (OECD, 2006), the OECD’s Employment, Labour and Social Affairs Committee set out a policy guideline in December 2015 to encourage employment at an older age (OECD, 2015). Other international organizations, such as the Gerontological Society of America (GSA), European Foundation (Eurofound), and Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF), have also recommended a set of policies on sustaining on aging workers. Table 2 summarizes the policy recommendations and the proposed strategies for their implementation.

Table. 2.

Summarizing the recent development in the workforce for older workers

| Region/ Country/ | Institution/ Department | Topic / Key focus area | Strategic / initiatives | Outcome | Contribution of technology | Policies implementation | Type of Policy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Australia Human Rights Commissions | Reduce the occurrence of chronic health conditions faced by the workforce |

● Public education campaign to reinforce the importance of healthy aging ● Facilitating good health in the workplace ● Organizational support and workplace adjustments |

● Expand the employment assistance fund to include training for managers and co-workers about employees with chronic health conditions |

● ICTs (Education and training) ● Medical tool |

1. Health and safety 2. Age friendly Work environment |

Public policies |

| Japan |

MHI (Mitsubishi Heavy Industries) Experts SPECTRA |

Extend the participation of experienced, knowledgeable, and skilled workers | ● Established a new company specifically for workers of retirement age and above (MHI Executive Experts) |

● Older employees support a range of engineering, procurement, and construction projects ● Older employees share their knowledge and train new recruits to help the next generation of specialists |

● At initial stage (the use of technology is not visible) | 1. Age friendly Work environment | Organizational policies |

| Germany | BMW Dingolfing, Southern Bavaria | Retain the skilled workforce in the production plant | ● Production plant specifically equipped to meet the needs of aging workers | ● The older workers perform better than the younger workers on another line at the same factory |

● Movable instruction screen with larger letters ● Magnifying glasses ● Customized workstations to allow workers to shift positions |

1. Workplace accommodation | Organizational policies |

| United States | Xerox, US | Identify steps to overcome musculoskeletal disorders | ● Developing a new ergonomic training program for aging workers | 19% decline in musculoskeletal disorders issues among older workers in 2008 |

● Office: Adjustable chairs and keyboard trays ● Manufacturing: Ergonomically designed tools ● Service: Periodic reviews of service technicians’ tools to ensure they are ergonomically sound |

1. Workplace accommodation | Organizational policies |

| Sweden | Swedish Steel (SSAB)Tunnplåt | Focus on health and wellbeing of older workers |

● Improvements in work environment and individual health check-ups for employees ● Age-dependent ability for a shift work |

Many older employees were able to work up to the regular retirement age |

● Spectacles supplied for specialized work ● Conference rooms with hearing loops ● Special device for packaging steel coils and sheets |

1. Health and safety 2. Age friendly Work environment 3. Workplace accommodation |

Organizational policies |

| Canada | Employment and Social Development Canada |

Increase the employability of unemployed older workers |

● Provide employment assistance and employability improvement for individuals aged between 55 and 64 |

● Participants age between 55 and 64 expressed satisfaction with the programs ● Older workers secured employment in retail, sales, services, health, and tourism sectors |

● Computer training | 1. Training and skill development | Public policies |

| Norway | Siemens AS | Increase internal mobility among workers | ● Provide constructive management mobility program | ● Drop in early retirement numbers | ● Computer training | 1. Training and skill development | Organizational policies |

| Sweden | Uppsala University Hospital | Provides education plan for older workers |

● Lifelong learning culture nurtured ● Education in healthcare sciences ● Changing organizational structure |

● The mean age of employees has increased in three years ● Decline in the early retirement |

● ICTs (Education and training) |

1. Health and safety 2. Training and skill development |

Organizational policies |

| Denmark |

Realkredit Danmark (Finance Institution) |

● Recruit employees aged 50 and over |

● Hire employees aged 50 + in direct customer service ● Recruit by matching the age profile of the customer with potential employees |

● The newly hired employees aged 50 and above were more competent and demonstrated a strong ability to solve problems in unfamiliar tasks | ● ICT (Education and training) | 1. Training and skill development | Organizational policies |

| US /Canada | Weyerhaeuser | ● Retain baby boomers in the workforce |

● Provide professional learning and development opportunities to employees at all levels ● Provide opportunities for growth through stretch assignments and cross-business exposure |

● Drop in the retirement numbers | ● ICTs (Education and training) | 1. Training and skill development | Organizational policies |

| Canada | The Bethany Care Society | Retaining and hiring older workers |

● Offer older employees more flexible work arrangements ● Offer attractive benefit packages (18 sick days, 3 weeks’ vacation, 3 flex days per year) ● Hire retired managers ● Train older staff in using new technology |

● Rise in new hires aged 50 and above | ● Technology training for older workers |

1. Age friendly Work environment 2. Training and skill development 3. Financial incentives |

Organizational policies |

| Germany | Deutsche Bahn | Retaining workers and reduce early retirement rate | ● Offer more flexible work arrangements | ● improvements in retention of older workers | ● “Digital marketplace” that helps workers to change shifts with their co-workers | 1. Flexible work arrangements | Organizational policies |

| Canada | Seven Oaks General Hospital | Reduce early retirement rate |

● Reduced work week ● Gradual retirement ● Voluntary, part-time work ● Job sharing ● Flexible work hours ● Telework ● Special leave |

● Noticeable improvements in retention of older workers | ● Teleworking |

1. Flexible work arrangements 2. Financial incentives |

Organizational policies |

The analysis conducted based on the policy documents and the case study of the firm and organizations that working on helping the older workers (Source: Appendix A2, Gray literature)

The government agencies aim to create additional supports to help to retain and re-hire older workers in the workforce (Gerontological Society of America (GSA), 2018; Eurofound, 2017). For example, the USA, Germany, Denmark, France, and Canada have focused on helping the unemployed older population via prolonged job searches (Gerontological Society of America (GSA), 2018; Eurofound, 2017; OECD, 2015). Moreover, initiatives to promote self-employment are often offered as an alternative option for the older population to contribute to the socio-economic development of a country (Marchant, 2013) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Recommendation of the OECD on Aging and Employment Policies

| Policy Recommendations | Strategies for Implementation |

|---|---|

| Incentives to continue working | i. Pension plan that encourages and rewards later retirement |

| ii. Allowing a combination of pension and work income | |

| iii. Restrict early retirement for workers in good health | |

| iv. Monitor the use of welfare benefits | |

| Encourage employers to retain and rehire older workers | i. Address age discrimination in the workplace |

| ii. Implement employment protection for older workers | |

| iii. New ways that further restrict mandatory retirement | |

| iv. Employers to identify mechanisms that help the older workers | |

| v. Employers should learn strategies to nurture an age-diverse workforce | |

| Employment opportunities for older adults | i. Encourage skill development |

| ii. Employment assistance for older adults to find a job | |

| iii. Improve working condition |

In addition to encouraging older adults to participate in the workforce, governments and employers should consider promoting flexible workplace practices to encourage older workers with physical challenges to stay in the workforce (OECD, 2015; Eurofound, 2017; Gerontological Society of America (GSA), 2018). Organizations that adopt age-friendly employment practices are likely to attract an older population and find themselves able to choose from a wider pool of talent (Martin et al., 2014). Creating proper incentive plans for workers to continue working at an older age is an essential strategy for sustaining older workers in the workforce, and communicating the value and benefits of this could encourage older workers to stay in the workforce even after retirement age. The 19th wave of the Retirement Confidence Survey (RCS) conducted in 2009 to examine the views and attitudes of working-age people and retirees in the USA reveals that 72% of the workers interviewed have expressed an interest in working after they retire (Helman et al., 2009). Thus, policies such as expanding the employee benefits program for workers over the age of 65 and providing generous health benefits and special leave, for example, would further encourage older workers to remain in the workforce.

Health and workplace safety will be a primary concern of employers hiring or retaining older workers, since older workers are more prone to workplace injuries compared to their younger counterparts (Nilsson, 2016; Wegman & McGee, 2004). Thus, strategies such as i) identifying health assessment tools that could potentially assist in monitoring the well-being of senior workers, ii) offering frequent health screenings to monitor the health of workers and encourage healthy work habits, and iii) promoting active living, healthy eating, stress management, and work-life balance initiatives are expected to play a role in maintaining the health and safety of older workers. Moreover, an ergonomic approach to avoid workplace injuries and illness has been found to be an effective way to encourage older adults’ participation in the workforce (Case et al., 2015; Fritzsche et al., 2014) (Table 2).

Taking into consideration the physical health of older workers and the challenges they face in their current work, policy initiatives such as flexible work options that focus on remote working, part-time employment, phased retirement, and bridge jobs could allow older workers to continue working past retirement age and ultimately provide financially stability in their later life (OECD, 2015). For instance, a number of British companies are practicing a flexible retirement policy by providing employees with an option to switch to a part-time position or to retire and return as a contract worker (Employers Forum on Age & IFF Research, 2006). Moreover, with ongoing advances in technology, the idea of a flexible work environment is increasingly achievable. For example, Patrickson (2002) noted that in Australia there are more employment opportunities for older workers in teleworking. However, determining the potential role of technology in helping senior workers in the workforce (e.g., workstation design and artificial intelligence) will be challenging in a multi-generational workplace. Haeger and Lingham (2014) stressed that, in the coming years, it is expected that there will be five generations “co-existing” in the workplace, and the differences in technological knowledge between each generation of workers is likely to create conflict between them. It is therefore necessary to identify and propose possible strategies for utilizing technology without creating age discrimination in the workplace.

Another policy initiative is to strengthen the employability of older workers through human capital development (Nagarajan et al., 2019; OECD, 2015), as training programs often provide the opportunity for older workers to shift into a career that accommodates their physical and mental health conditions. Employers could outline prospective training and development programs that could address potential skills gaps related to technology within workforces and subsequently motivate senior workers to remain active. Policymakers could also concentrate on promoting training and development programs for the older population to better prepare them for a job placement in which they will perform well. The educational attainment of a worker is associated with a positive effect on their well-being—for instance, Venti and Wise (2014) have noted that men with a college degree stay longer in the workforce and less likely to claim social security benefits than men without a college degree.

Assessing the Potential Outcome of the Policy Initiatives

The policy initiatives that encourage the older population to remain in the workforce have been made mainly in response to the looming challenges of an aging population. Hence the implementation of policies such as raising the retirement age, encouraging older workers to remain in the workforce, and creating senior citizen education programs to improve human capital development with a view to benefitting the country via social, economic, and scientific development. The following subsection discusses the potential impact of the policy initiatives on the social, economic, and scientific development of a country.

The Potential Social Outcome

Encouraging the older population to participate in the workforce by overcoming age discrimination is expected to counteract the problem of loneliness, as much of the retired population faces social isolation (Shiovitz-Ezra et al., 2018). Furthermore, engaging in an intergenerational work environment is likely to be an effective way to break down barriers between different age groups, and engaging the older population in the workforce can mitigate depression in old age as a result of living alone (Bilinska et al., 2016).

Being in a working environment also boosts self-esteem and confidence among the senior population, and subsequently encourages them to live their later life independently, partly because they will experience less anxiety about their financial status. According to Aisa et al. (2015), the continuous participation of older workers in the workforce is expected to decrease the dependency ratio. Moreover, training and learning opportunities provided at a workplace can help a person to develop a professional identity and take charge of their life, with the freedom to plan, choose, and decide on their needs, wants, and preferences (Ravichandran et al., 2015). Older workers’ active participation in the workforce promotes self-care and self-management of their health conditions. Hence, their involvement in the workforce helps to maintain their physical and mental health.

Older workers play an essential role in the workforce and bring a wealth of experience to their communities and their networks. Raising the retirement age is therefore likely to reduce the dependency of seniors on their family members and communities. Staying in the workforce also puts them in a position to support their dependent children and older parents with care needs in addition to letting them prepare for their own later life. Retaining senior workers in the workforce would allow employers to preserve their skills and facilitate a smooth knowledge transfer process between one generation of workers and the next. A smooth knowledge transition opens up the possibility that the involvement of the older population in the workforce will provide an opportunity for millennials to grow up with faith in a better tomorrow.

The Potential Economic Impact

Economists often see the policy initiatives to encourage older workers in the labor market as a key approach to overcoming labor shortages and solving governmental budget deficits. For instance, retaining aging workers is likely to increase the overall productivity of a country, and the seniors’ subsequent contribution to the gross domestic product will also increase.

Sustaining aging workers in the workplace is expected to reduce demand for spending on seniors-related programs such as health care spending and pension (Carmichael & Ercolani, 2015; Finch, 2014). The ongoing participation of aging workers is expected to increase the growth rate of per capita income, which will consequently contribute to increasing revenue at a national level.

Aging workers are likely to experience increased security not only because of their income stream, but also because being in a working environment often educates them about managing their funds effectively (Alexandria, 2014). Their ongoing earning capacity allows them to fulfill their present needs as a consumer while also saving funds to prepare for their later life. From an employer’s perspective, experienced aging workers will require less supervision, which will help to reduce production costs. Hence, hiring and retaining experienced aging workers in the workforce can result in a higher quality of work for a reduced cost (Alexandria, 2014).

The Potential Science Impacts

The current unprecedented increase in life expectancy requires innovative approaches to improve and enrich the lives of the senior population. As such, the primary task of researchers will be to identify ways for an individual to enjoy their extended senior years (Haeger & Lingham, 2014). Implementing policies to encourage the older population to stay in the workforce for longer provides an opportunity for researchers to explore more broadly and in more depth the challenges of an aging workforce and the use of science and technology as tools to develop innovative ways to help older workers perform well. Research institutions all over the world (e.g., AGE-WELL and STAR institute from Canada, JRF from the UK, GSA from the USA, and GLO from Germany) are actively involved in research related to aging and disseminate their findings about seniors’ participation in the workforce.

The policy initiatives to retain older adults in the workforce allow research institutions to i) discover the challenges of implementing an age-friendly work environment, ii) identify mechanisms that contribute to an age-friendly work environment, iii) focus on developing an age-friendly assessment tool to examine the performance of aging workers, iv) investigate the efficiency of training on the performance of senior workers, v) reform the training methodology according to aging workers’ needs, and vi) prepare aging workers to work with artificial intelligence.

Furthermore, in the context of older workers’ health, the research institutions are particularly interested in identifying the potential use of technology in assisting older workers to perform well in the labor market. For instance, they are focusing on identifying technological tools, designing simplified technology, and developing a technological tool that is practical in a multi-generational workplace. Considering the important role of technology in helping older workers, the following section discusses recent developments in the workforce for older workers.

Recent Developments in the Workforce for Older Workers

An increase in life expectancy and decline in the fertility rate have increased the proportion of older workers in the workforce. Older workers are often valued for their in-depth knowledge and experience in their particular fields, and they can continue to participate in the workforce by using technology and improving their education levels via training and skills development. A growing aging population has implications for socio-economic development, and many developed countries and various organizations have responded by developing policies to retain older workers to address labor shortages and acknowledging the role of technology in realizing these policies. Researchers, government agencies, employers, and communities are all aware of the twinned issue of labor shortages and the need to retain older workers in the workforce.

To start the discussion on opportunities for developing new technology-based products and services for the aging workforce, it is useful to start analyzing the current achievement of companies and organizations in integrating technology in the workforce to meet the needs of an aging workforce. Table 2 summarizes the role of the stakeholders and their initiatives in incorporating technology as a tool to improve the productivity of older workers in the labor market. The changes made in the workforce for older workers demonstrate that the majority of the stakeholders significantly depend on technology when it comes to assisting older workers.

Figure 1, the summary of the case study (see Table 2) evidence that the majority of organizations are highly relying on technology in their efforts to motivate and improve the productivity of the older workforce. Additionally, Table 2 demonstrates that at the present time, companies and organizations are focusing on utilizing technology for human capital development and promoting an age-friendly work environment (e.g., teleworking, automation and ergonomic tools). For example, BMW is specifically focused on equipping older workers with technological tools and Australia’s Human Rights Commission is focused on using technology for education and training. Table 2 also demonstrates that technology plays a vital role in the successful implementation of policy plans and in sustaining older workers’ participation in the workforce.

Opportunities for Applying Technology and Innovation to Meet the Needs of an Aging Workforce

As life expectancies have risen in the past two decades, so too has the proportion of older workers in the labor force. For example, in the USA, nearly four out of ten baby boomers have remained actively engaged in the workforce beyond retirement age (Quinn, 2016). However, to actively engage in today’s work environment, older workers are expected to interact with a variety of technologies (Czaja & Sharit, 2016), and the technological evolution of the workplace is expected to open up opportunities for older workers to perform well there. Technology plays a significant role in supporting government initiatives to sustain older workers in the workforce (Haeger & Lingham, 2014). On-the-job training and knowledge of technological skills obtained by the older adults are expected to lessen the issue of productivity that is associated with age-related challenges (Sarti & Torre, 2018; Schloegel et al., 2016; Zimmer et al., 2015).

The potential of technology to help create an age-friendly work environment is undeniable (Haeger & Lingham, 2014). For instance, it could play a key role in designing a workplace that takes into consideration the needs of both older and younger workers (Nagarajan et al., 2019). However, the scope of the role of technology and innovation in designing a workspace that accommodates the needs and preferences of older workers varies by sector. Older workers in the service sector with a musculoskeletal disorder (MSD), for example, often value an ergonomic office chair and adjustable desk, as these may minimize their physical discomfort. A side benefit of designing a workspace specifically for an aging worker is that it may reduce workers’ compensation claims related to musculoskeletal disorders. For older workers in the manufacturing sectors, technology plays a vital role in preventing falls and injuries in the workplace. For example, installing movable instruction screens with larger lettering, better ergonomic back supports for mobile tool-trolleys, well-designed tilt tables, and shelving installed at safe heights (neither too high nor too low) are all expected to reduce physical demands and protect senior workers from falls and injuries.

For an older adult, prolonged employment participation depends on their particular circumstances (e.g., their financial status, health condition, or family situation). An option such as blended work (e.g. flexible working schedules) is likely to help the older population remain in the workforce (Damman, 2016), and technology training and remote working settings would allow older adults with mobility issues in particular to stay in the workforce.

Exploiting the potential of artificial intelligence and automating tasks that consist of multiple steps may also help aging workers perform their job well. Older workers tend to have shorter reach distances and less flexibility, and harnessing the potential of artificial intelligence to assist them in accomplishing tasks that are physically demanding or dangerous, and rendered more so because of older workers’ physical limitations, could contribute to creating a safe working environment (Camillo, 2012). Another option is to promote teleworking so that organizations continue to benefit from the skills and knowledge of older employees. Working from home and communicating with the workplace electronically would circumvent any issues around transportation and mobility experienced by older workers.

Designing and making available portable and wearable electronic devices and apps that monitor older adults’ physical activities and health in the workplace would be an effective strategy to protect the health and safety of older workers in the workforce. For instance, a wearable sensor that detects when aging workers perform their task in a way that is likely to cause injury would alert a worker to the potential hazard and give them time to adjust their physical approach to their task. A system that diagnoses mild cognitive impairment at work and devices that slow cognitive decline in older workers would also improve performance.

The most common challenges faced by older adults in the workforce who were required to use technology were that they felt uncomfortable doing so and often found it difficult to learn how to use it (Haeger & Lingham, 2014). Many employers use the perception of older adults as reluctant adopters of technology, ostensibly reinforced by their own assessments of themselves, as a reason for not hiring older workers (Haeger & Lingham, 2014). However, with a growing aging workforce, older adults appear to be the fastest-growing age group in terms of welcoming technology into their daily life (Quinn, 2016). In fact, according to Quinn (2016), a total of 49 million older adults in the USA are estimated to use an average of 24 different apps in a given month. Hence, initiatives to promote online training programs to increase the employability of older workers in technology-based sectors seem like a very realistic option.

Conclusion and Future Work

Labor shortages are a global phenomenon as the post-war "baby boomer" generation retires. As a result, many industrialists are struggling to improve the productivity level of their companies. However, at the present time, age 65 is often referred to as the new 55, and the older population is seen as potentially active contributors to economic well-being. Knowing that people who live longer often stay healthier, the aging population is no longer viewed as a burden on society. Moreover, with technological developments, including automation and artificial intelligence, a worker’s job performance is no longer immediately related to their age. Our analysis confirmed that companies and organizations are relying heavily on technology to re-hire and retain the older workers in accordance with government policy on the retirement age. In fact, for some employers, technology is considered as a tool to counteract age discrimination in the workplace.

In order to retain older workers, technology components were very much implemented to improve overall productivity and act as a motivating factor for the older population to remain in the workforce. However, in the long term, technology and the preference of employers for automation and artificial intelligence are likely to take jobs away from the older population (Nagarajan et al., 2019). Hence, in the future, it will be essential to revisit the policy initiatives and propose strategies to govern the influence of automation and artificial intelligence in this respect.

Even though our study provides an in-depth analysis of policies related to older workers and the role of technology in realizing policy initiatives, we feel it has limitations and offers opportunities for future investigation. The speed at which the aging population is growing in developing and less developed countries is a robust indicator that an aging population is no longer an issue for primarily developed countries. (Nagarajan et al., 2017). The current demographic transition is likely to manifest as a global trend in the twenty-first century. In that context, the main limitation of this study is that, for the analysis, we did not take into account policy implementations in middle- and low-income countries. Furthermore, while obtaining international policy initiatives, we limited our search base to sources written in English.

As COVID-19 continued to rise, remote working was increasingly seen as the only option for many people who wished to remain in the workforce. Given seniors’ particular vulnerability to this virus, aging workers may be reluctant to return to their workplaces and prefer to work remotely for the foreseeable future. Hence, for future work, we are planning to analyze the extent to which governments and organizations will accommodate older workers’ preference to work remotely and to perform well in doing so.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank researchers from the STAR Institute, AGE-WELL NCE and APPTA teams for providing their collected information from the experts in the field of policy aging for this research work.

Biographies

N Renuga Nagarajan

is the Researcher of the STAR Institute, and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Public Policy at Adler University. Her research interest focused on “economic growth,” “policy analysis,” “labour market, aging population and aging workforce”. She has published a number of scientific papers for peer-reviewed journals.

Andrew Sixsmith

is the Director of the STAR Institute, and a Professor in the Department of Gerontology at Simon Fraser University. He is the Scientific Director of AGE-WELL NCE, Canada’s research and innovation network on aging and technology. His research interests include technology for independent living, theories and methods in aging and understanding the innovation process. His work has involved him in a leadership and advisory role in numerous major international projects and initiatives with academic, government and industry partners. He is past President of the International Society of Gerontechnology. Dr. Sixsmith has authored three books and published over 160 peer-reviewed papers and book chapters.

Appendix

A1. Reviewed Articles

Hertel G and Zacher H (2018) Managing the aging workforce. In: Ones DS, Anderson N, Viswesvaran C and HK Sinangil (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of Industrial, Work & Organization Psychology (pp.396–428). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sarti D and Torre T (2018) Generation X and knowledge work: The impact of ICT. What are the implications for HRM? Lecture Notes in Information Systems and Organisation 23: 227–240.

Lissitsa S, Chachashvili-Bolotin S and Bokek-Cohen Y (2017) Digital skills and extrinsic rewards in late career. Technology in Society 51: 46–55.

Kowalski THP and Loretto W (2017) Well-being and HRM in the changing workplace. International Journal of Human Resource Management 28: 2229–2255.

Rego A, Vitória A, Cunha MPE, Tupinambá A and Leal S (2017) I Developing and validating an instrument for measuring managers’ attitudes toward older workers. International Journal of Human Resource Management 28: 1866–1899.

Kroon AC, Vliegenthart R and van Selm M (2017) Between accommodating and activating: framing policy reforms in response to workforce aging across Europe. International Journal of Press/Politics 22: 333–356.

Ryan C, Bergin M and Wells JS (2017) Valuable yet Vulnerable—A review of the challenges encountered by older nurses in the workplace. International Journal of Nursing Studies 72: 42–52.

Gerpott FH, Lehmann-Willenbrock N, Voelpel SC (2017) A phase model of intergenerational learning in organizations. Academy of Management Learning and Education 16: 193–216.

Mahesa RR, Vinodkumar MN and Neethu V (2017) Modeling the influence of individual and employment factors on musculoskeletal disorders in fabrication industry. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing and Service Industries 27: 116–125.

Rocha R (2017) Aging, productivity and wages: Is an aging workforce a burden to firms? Espacios 38: 21–33.

Schinner M, Valdez AC, Noll E, Schaar AK, Letmathe P and Ziefle M (2017) Industrie 4.0’ and an aging workforce – a discussion from a psychological and a managerial perspective. In: Zhou J, Salvendy G (Eds) Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Applications, Services and Contexts. ITAP 2017. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 10,298: 537–556.

Earl C, Taylor P, Roberts C, Huynh P and Davis S (2017) The workforce demographic shift and the changing nature of work: Implications for policy, productivity, and participation. Advanced Series in Management 17: 3–34.

Sammarra A, Profili S, Maimone F and Gabrielli G (2017) Enhancing knowledge sharing in age-diverse organizations: The role of HRM practices. Advanced Series in Management 17: 161–187.

Wendsche J, Ghadiri A, Bengsch A and Wegge J (2017a) Antecedents and outcomes of nurses' rest break organization: A scoping review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 75, 65–80.

Wendsche J, Hacker W and Wegge J (2017b) Understaffing and registered nurses turnover: The moderating role of regular rest breaks. German Journal of Human Resource Management 31, 238–259.

Bilinska P, Wegge J and Kliegel M (2016) Caring for the elderly but not for the own old employees? Organizational age climate, age stereotypes and turnover intentions in young and old nurses. Journal of Personnel Psychology 15, 95–105.

Kulik CT, Perera S and Cregan C (2016) Engage me: The mature-age worker and stereotype threat. Academy of Management Journal 59: 2132–2156.

Palm K (2016) A case of phased retirement in Sweden. In Ordoñez de Pablos P andTennyson R (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Human Resources Strategies for the New Millennial Workforce, PP 351–370.

Schloegel U, Stegmann S, Maedche A and van Dick R (2016) Reducing age stereotypes in software development: The effects of awareness- and cooperation-based diversity interventions. Journal of Systems and Software 121: 1–15.

Wanberg CR, Kanfer R, Hamann DJ and Zhang Z (2016) Age and reemployment success after job loss: An integrative model and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 142: 400–426.

Hollis-Sawyer L and Dykema-Engblade A (2016) Women and Positive Aging: An International Perspective. Women and Positive Aging: An International Perspective, PP 1–352.

Poulston J and Jenkins A (2016) Barriers to the employment of older hotel workers in New Zealand. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism 15: 45–68.

Hennekam S (2016) Employability and performance: a comparison of baby boomers and veterans in The Netherlands. Employee Relations 38: 927–945.

Loichinger E and Skirbekk V (2016) International variation in ageing and economic dependency: A cohort perspective. Comparative Population Studies 41: 121–144.

Nilsson K (2016) Conceptualisation of ageing in relation to factors of importance for extending working life—A review. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 44: 490–505.

Ng ES and Parry E (2016) Multigenerational research in human resource management. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management 34:1–41.

Gonzalez I and Morer P (2016) Ergonomics for the inclusion of older workers in the knowledge workforce and a guidance tool for designers. Applied Ergonomics 53: 131–142.

Wendsche J, Lohmann-Haislah A and Wegge, J. (2016) The impact of supplementary short rest breaks on task performance—A meta-analysis, Sozialpoiltik.CH, 2, 1–24.

Yang T, Shen YM, Zhu M, Liu Y, Deng J, Chen Q and See LC (2015) Effects of co-worker and supervisor support on job stress and presenteeism in an aging workforce: A structural equation modelling approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 13: 1–15.

Carmichael F and Ercolani MG (2015) Age-training gaps across the European Union: How and why they vary across member states. Journal of the Economics of Ageing 6: 163–175.

Cahill KE, Giandrea MD and Quinn JF (2015) Chapter 13—Evolving Patterns of Work and Retirement. In Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences: Eighth Edition, PP 271–291.

Park J and Kim S (2015) The differentiating effects of workforce aging on exploitative and exploratory innovation: The moderating role of workforce diversity. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 32: 481–503.

Boenzi F, Digiesi S, Mossa G, Mummolo G and Romano VA (2015) Modelling workforce aging in job rotation problems. IFAC-PapersOnLine 48: 604–609.

Zimmer JC, Tams S, Craig K, Thatcher J and Pak R (2015) The role of user age in task performance: examining curvilinear and interaction effects of user age, expertise, and interface design on mistake making. Journal of Business Economics 85: 323–348.

Matt SB, Fleming SE and Maheady DC (2015) Creating Disability Inclusive Work Environments for Our Aging Nursing Workforce. Journal of Nursing Administration 45: 325 – 330.

Yen SH, Lim HE and Campbell JK (2015) Age and productivity of academics: A case study of a public university in Malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Economic Studies 52: 97–116.

Case K, Hussain A, Marshall R, Summerskill S and Gyi D (2015) Digital Human Modelling and the Ageing Workforce. Procedia Manufacturing 3: 3694–3701.

Duffield C, Graham E, Donoghue J, Griffiths R, Bichel-Findlay J and Dimitrelis S (2015) Why older nurses leave the workforce and the implications of them staying. Journal of Clinical Nursing 24: 824–831.

Boenzi F, Mossa G, Mummolo G and Romano VA (2015) Workforce aging in production systems: Modeling and performance evaluation. Procedia Engineering 100: 1108–1115.

Ravichandran S, Cichy KE, Powers M and Kirby K (2015) Exploring the training needs of older workers in the foodservice industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management 44: 157–164.

Besen E, Matz-Costa C, James JB and Pitt-Catsouphes M (2015) Factors buffering against the effects of job demands: How does age matter? Journal of Applied Gerontology 34: 73–101.

Bieling G, Stock RM and Dorozalla F (2015) Coping with demographic change in job markets: How age diversity management contributes to organisational performance. Zeitschrift fur Personalforschung 29: 5–30.

Jeske D and Roßnagel CS (2015) Learning capability and performance in later working life: Towards a contextual view. Education and Training 57: 378–391.

Froehlich DE, Beausaert SAJ and Segers MSR (2015) Age, employability and the role of learning activities and their motivational antecedents: a conceptual model. International Journal of Human Resource Management 26: 2087–2101.

Wegge, J., Shemla, M., and Haslam, S. A. (2014), Health promotion through leadership. German Journal of Research in Human Resource Management 28, 1–2.

Fritzsche L, Wegge J, Schmauder M, Kliegel M and Schmidt, KH (2014) Good ergonomics and team diversity reduce absenteeism and errors in car manufacturing. Ergonomics 57: 148–161.

Eichhorst W, Boeri T, De Coen A, Galasso V, Kendzia M and Steiber N (2014) How to combine the entry of young people in the labour market with the retention of older workers? IZA Journal of European Labor Studies 3: 1–23.

Parker M, Acland A, Armstrong HJ, Bellingham JR, Bland J, Bodmer HC, Burall S, Castell S, Chilvers J, Cleevely DD, Cope D, Costanzo L, Dolan JA, Doubleday R, Feng WY, Godfray HCJ, Good DA, Grant J, Green N, Groen AJ, Guilliams TT, Gupta S, Hall AC, Heathfield A, Hotopp U, Kass G, Leeder T, Lickorish FA, Lueshi LM, Magee C, Mata T, McBride T, McCarthy N, Mercer A, Neilson R, Ouchikh J, Oughton EJ. Oxenham D, Pallett H, Palmer J, Patmore J, Petts J, Pinkerton J, Ploszek R, Pratt A, Rocks SA, Stansfield N, Surkovic E, Tyler CP, Watkinson AR, Wentworth J, Willis R, Wollner PKA, Worts K and Sutherland WJ (2014) Identifying the science and technology dimensions of emerging public policy issues through horizon scanning. PLoS One 9: e96480.

Boenzi F, Mossa G, Mummolo G and Romano VA (2014) Evaluating the effects of workforce aging in human-based production systems: A state of the art. Proceedings of the XIX Summer School Francesco Turco (Conference Paper) Senigallia, Italy September 9–12.

Brooke EM (2014) Ageing workforces: Lagging in the G20 race. Australasian Journal on Ageing 33: 215–219.

Yeh WY (2014) Age differences in physical and mental health conditions and workplace health promotion needs among workers: An example of accommodation and catering industry employees. Gerontechnology 13: 313 -313.

Tikkanen T (2014) Lifelong learning and skills development in the context of innovation performance: In: Schmidt-Hertha B, Krašovec SJ and Formosa M (Eds) Learning across Generations in Europe. Research on the Education and Learning of Adults, SensePublishers, Rotterdam, PP 95–120.

Guerrazzi M (2014) Workforce ageing and the training propensity of Italian firms Cross-sectional evidence from the INDACO survey. European Journal of Training and Development 38: 803–821.

Martin G, Dymock D, Billett S and Johnson G (2014) In the name of meritocracy: Managers' perceptions of policies and practices for training older workers. Ageing and Society 34: 992–1018.

Killam W and Weber B (2014) Career adaptation wheel to address issues faced by older workers. Adultspan Journal 13: 68–78.

Maikala RV, Cavuoto LA, Maynard WS, Fox RR, Lin JH, Liu J and Lavallière M (2014) Aging, obesity and beyond: Implications for healthy work environment. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 58th annual meeting. PP 1648 – 1652.

Graham E, Donoghue J, Duffield C, Griffiths R, Bichel-Findlay J and Dimitrelis S (2014) Why do older RNs keep working? Journal of Nursing Administration 44: 591–597.

Hashim J and Wok S (2014) Competence, performance and trainability of older workers of higher educational institutions in Malaysia. Employee Relations 36: 82–106.

Tams S, Grover V and Thatcher J (2014) Modern information technology in an old workforce: Toward a strategic research agenda. Journal of Strategic Information Systems 23: 284–304.

Liebermann S, Wegge J and Müller A (2013a) Drivers of the expectation of remaining in the same job until retirement age: A working life span demands-resource model. European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology 22, 347–361.

Liebermann S, Wegge J, Jungmann F and Schmidt KH (2013b) Age diversity and individual team member health: The moderating role of age and age stereotypes. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 86, 184–202.

Axelrad H, Luski I and Miki M (2013) Difficulties of integrating older workers into the labor market: Exploring the Israeli labor market. International Journal of Social Economics 40: 1058–1076.

Reynolds F, Farrow A and Blank A (2013) Working beyond 65: A qualitative study of perceived hazards and discomforts at work. Work 46: 313–323.

Karpinska K, Henkens K and Schippers J (2013) Retention of older workers: Impact of Managers' age norms and stereotypes. European Sociological Review 29: 1323–1335.

Marchant T (2013) Keep going: career perspectives on ageing and masculinity of self-employed tradesmen in Australia. Construction Management and Economics 31: 845–860.

Wells-Lepley M, Swanberg J, Williams L, Nakai Y and Grosch JW (2013) The Voices of Kentucky Employers: Benefits, Challenges, and Promising Practices for an Aging Workforce. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 11: 255–271.

Göbel C and Zwick T (2013) Are personnel measures effective in increasing productivity of old workers? Labour Economics 22: 80–93.

Bosch N and ter Weel B (2013) Labour-Market Outcomes of Older Workers in the Netherlands: Measuring Job Prospects Using the Occupational Age Structure. Economist (Netherlands) 161: 199–218.

Fuertes V, Egdell V and McQuaid R (2013) Extending working lives: Age management in SMEs. Employee Relations 35: 272–293.

Poulston J and Jenkins A (2013) The Persistent Paradigm: Older Worker Stereotypes in the New Zealand Hotel Industry. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism 12: 1–25.

Hsu YS (2013) Training older workers: A review. In Field J, Burke RJ and Cooper CL,The SAGE handbook of aging, work and society, PP 283–299.

Schlick CM, Frieling E and Wegge J (2013) Age-differentiated work systems, Berlin: Springer.

Wang M, Olson DA and Shultz KS (2012) Mid and late career issues: An integrative perspective. Mid and Late Career Issues: An Integrative Perspective New York: Routledge, PP 1- 240.

Hedge JW and Borman WC (2012) Work and Aging. The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging, PP 1–744.

Elias SM, Smith WL and Barney CE (2012) Age as a moderator of attitude towards technology in the workplace: Work motivation and overall job satisfaction. Behaviour and Information Technology 31: 453–467.

Dymock D, Billett S, Klieve H, Johnson GC and Martin G (2012) Mature age 'white collar' workers' training and employability. International Journal of Lifelong Education 31: 171–186.

Greller MM (2012) Workforce Planning with an Aging Workforce, in Hedge JW and Borman WC (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, PP 365–379.

Gutman A (2012) Age-Based Laws, Rules, and Regulations in the United States, in Hedge JW and Borman WC (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, PP 606 – 628.

Sharit J and Czaja SJ (2012) Job Design and Redesign for Older Workers. in Hedge JW and Borman WC (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, PP 545–482.

Allen TD and Shockley KM (2012) Older Workers and Work-Family Issues. in Hedge JW and Borman WC (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, PP 520–537.

Thompson LF and Mayhorn CB (2012) Aging Workers and Technology. in Hedge JW and Borman WC (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, PP 341- 364.

Rizzuto TE, Cherry KE and LeDoux JA (2012) The Aging Process and Cognitive Capabilities. in Hedge JW and Borman WC (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, PP 236 – 255.

Göbel C and Zwick T (2012) Age and Productivity: Sector Differences. Economist 160: 35–57.

Cho YJ and Lewis GB (2012) Turnover Intention and Turnover Behavior: Implications for Retaining Federal Employees. Review of Public Personnel Administration 32: 4- 23.

Williams van Rooij S (2012) Training older workers: Lessons learned, unlearned, and relearned from the field of instructional design. Human Resource Management 51: 281–298.

Ng TWH and Feldman DC (2012) Evaluating six common stereotypes about older workers with meta-analytical data. Personnel Psychology 65, 821–858.

Cleveland JN and Lim AS (2012) Employee age and performance in organizations. In Shultz KS and Adams GA (Eds.) Aging and Work in The 21st Century, PP 109–137.

Bowen CE, Noack MG and Staudinger UM (2011) Aging in the Work Context. In Schaie KW and Willis SL (Eds.) Handbook of the Psychology of Aging, PP 263–277.

Roßnagel CS, Baron S, Kudielka BM and Schömann K (2011) A competence perspective on lifelong workplace learning. In Margaret PC (Eds.) Handbook of Lifelong Learning Developments. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Frosch K, Göbel C and Zwick T (2011) Separating wheat and chaff: age-specific staffing strategies and innovative performance at the firm level [Den Weizen von der Spreu trennen – Altersbezogene Personalpolitik und Innovationen auf der Betriebsebene]. Journal for Labour Market Research 44: 321–338.

Meyer J (2011) Workforce age and technology adoption in small and medium-sized service firms. Small Business Economics 37: 305–324.

Rizzuto TE (2011) Age and technology innovation in the workplace: Does work context matter? Computers in Human Behavior 27: 1612–1620.

Peltokorpi V (2011) Performance-related reward systems (PRRS) in Japan: Practices and preferences in Nordic subsidiaries. International Journal of Human Resource Management 22: 2507–2521.

Kaarst-Brown ML and Birkland JLH (2011) Researching the older it professional: Methodological challenges and opportunities. SIGMIS CPR 2011—Proceedings of the 2011 ACM SIGMIS Computer Personnel Research Conference, PP 113 -118.

Van Ours JC and Stoeldraijer L (2011) Age, wage and productivity in Dutch manufacturing. Economist 159: 113–137.

Cataldi A, Kampelmann S and Rycx F (2011) Productivity-Wage gaps among age groups: Does the ICT environment matter? Economist 159:193–221.

Marshall VW (2011) A life course perspective on information technology work. Journal of Applied Gerontology 30: 185–198.

Armstrong-Stassen M and Schlosser F (2011) Perceived organizational membership and the retention of older workers. Journal of Organizational Behavior 32: 319–344.

Schacht S and Maedche A (2010) On enterprise information systems addressing the demographic change. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, Volume 3, ISAS, Funchal, Madeira, Portugal.

Žnidaršič J (2010) Age management in Slovenian enterprises: The viewpoint of older employees. Zbornik Radova Ekonomskog Fakultet au Rijeci 28: 271–301.

Zülch G and Becker M (2010) Impact of ageing workforces on long-term efficiency of manufacturing systems. Journal of Simulation 4: 260–267.

Hofäcker D (2010) Older workers in a globalizing world: An international comparison of retirement and late-career patterns in western industrialized countries. Older Workers in a Globalizing World: An International Comparison of Retirement and Late-Career Patterns in Western Industrialized Countries, PP 1–317.

Roßnagel CS, Baron S, Kudielka BM and Schömann K (2010) A competence perspective on lifelong workplace learning. Professions – Training, Education and demographics, PP 1 – 56.

Taylor P, Jorgensen B and Watson E (2010) Population ageing in a globalizing labour market: Implications for older workers. China Journal of Social Work 3: 259–272.

Graham EM and Duffield C (2010) An ageing nursing workforce. Australian Health Review 34: 44–48.

Clark RL, Ogawa N, Kondo M and Matsukura R (2010) Population decline, labor force stability, and the future of the Japanese economy.European. Journal of Population 26: 207–227.

Shultz KS, Wang M, Crimmins EM and Fisher GG (2010) Age differences in the demand-control model of work stress: An examination of data from 15 European countries. Journal of Applied Gerontology 29: 21–47.