Abstract

Background

Sharing outpatient notes with patients may bring clinically important benefits, but notes may sometimes cause patients to feel judged or offended, and thereby reduce trust.

Objective

As part of a larger survey examining the effects of open notes, we sought to understand how many patients feel judged or offended due to something they read in outpatient notes, and why.

Design

We analyzed responses from a large Internet survey of adult patients who used secure patient portals and had at least 1 visit note available in a 12-month period at 2 large academic medical systems in Boston and Seattle, and in a rural integrated health system in Pennsylvania.

Participants

Adult ambulatory patients with portal accounts in health systems that offered open notes for up to 7 years.

Approach

(1) Quantitative analysis of 2 dichotomous questions, and (2) qualitative thematic analysis of free-text responses on what patients found judgmental or offensive.

Key Results

Among 22,959 patient respondents who had read at least one note and answered the 2 questions, 2,411 (10.5%) reported feeling judged and/or offended by something they read in their note(s). Patients who reported poor health, unemployment, or inability to work were more likely to feel judged or offended. Among the 2,411 patients who felt judged and/or offended, 2,137 (84.5%) wrote about what prompted their feelings. Three thematic domains emerged: (1) errors and surprises, (2) labeling, and (3) disrespect.

Conclusions

One in 10 respondents reported feeling judged/offended by something they read in an outpatient note due to the perception that it contained errors, surprises, labeling, or evidence of disrespect. The content and tone may be particularly important to patients in poor health. Enhanced clinician awareness of the patient perspective may promote an improved medical lexicon, reduce the transmission of bias to other clinicians, and reinforce healing relationships.

KEY WORDS: bias, language, health information transparency, patient-doctor relationship, trust

BACKGROUND

Health systems are increasingly offering patients ready electronic access to clinician notes, and patients strongly support such practice beneficial, citing many potentially important clinical benefits.1–8 However, by offering patients a window into how clinicians view them and their conditions, such notes may also cause patients to feel judged or offended, and thereby reduce trust.4,9 Many clinicians worry about such potential consequences.6,10,11 With the goal of helping to inform and guide the practice of sharing notes, we analyzed data from a large survey of patients at 3 healthcare organizations and explored what patients may find judgmental or offensive in their notes. The experience of feeling offended, by definition, suggests an expectation was not met. Our analysis draws from a growing body of literature which describes the various dimensions of trust and respect in the clinician-patient relationship and provides a contextual framework for what patients may expect from clinicians.12–18

METHODS

Data Collection

We examined responses from a 2017 web-based survey of patients who had been seen in hospital offices and community practices at 3 health systems: Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), an academic health system in the Boston area; University of Washington Medicine (UW) in Seattle, an academic health system in Seattle that included a safety net hospital and practices; and Geisinger, a rural integrated health system in Pennsylvania. These organizations began sharing notes with patients in primary care in 2010 and have since expanded note sharing across ambulatory care specialties. Eligible patients were 18 years or older and had at least 1 ambulatory visit note available on the patient internet portal in the previous 12 months. Walker et al. have published detailed descriptions of the methods used in this survey.6

Patients who reported having read at least 1 note were asked 2 yes/no questions: “Have you ever felt offended by something you read in a visit note?” and “Have you ever felt judged by something you read in a note?” If patients answered affirmatively, they were prompted to answer two open-ended questions: “Please explain what offended you,” and “Please explain what made you feel judged.” Focusing on the responses to these 4 items, we conducted a mixed methods analysis.

Analysis of the Dichotomous Questions

We analyzed responses from patients who answered both yes/no questions and whose report of having read a note in the past year was confirmed by portal tracking data.6 We used descriptive statistics to assess sociodemographic characteristics of patients who did and did not report feeling judged and/or offended, and because we expected even small differences to be significantly different due to the total number of respondents, we selected differences of 5% or more as a threshold for reporting here. Analyses were done using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.).

Thematic Analysis

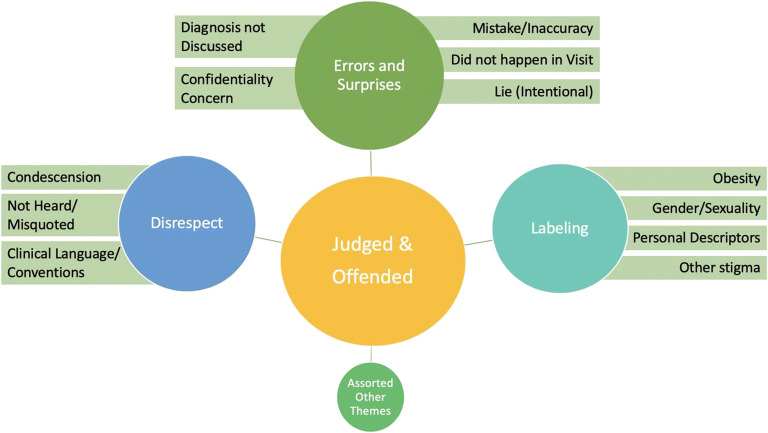

We used a 3-step process to analyze the free-text responses. Two authors (LF and CD) together reviewed the first 100 responses to each, initially identifying 7 themes. We found in this first pass that many patients did not distinguish between offended and judged, e.g., many comments in response to the second question, “Did you feel judged?,” included the words “see above,” referring to their free-text response to the preceding question, “Were you offended?”. Therefore, we combined free-text comments to both “judged” and “offended” for the remainder of the analysis. Second, one author (LF) and 2 other coders reviewed 150 additional randomly selected responses to refine the themes and together identified final categories for coding. We classified free-text responses into 12 codes that we grouped into 3 overarching domains: errors and surprises, labeling, and disrespect (Fig. 1). Finally, the same 3 coders analyzed all responses independently and assigned 1 code that best characterized the dominant or primary theme of each free-text response. They classified as “not applicable” responses that were uninterpretable or not directly applicable to a note, e.g., “no comment” or responses that clearly referred only to the appointment itself, rather than to the note. If at least 2 of 3 reviewers agreed on a code, then that code was assigned, and the fourth coder (CD) adjudicated responses when all 3 thematic codes were disparate. We used Fleiss’ kappa for m raters to measure inter-rater reliability. We used REDCap software19,20 hosted at BIDMC to organize free-text responses and subsequent coding.

Figure 1.

Framework for thematic analysis: overarching domains and specific codes.

RESULTS

Results of Quantitative Analysis

We contacted 136,815 patients and received 29,656 responses, a response rate of 21.7%. Among the 22,959 patients who had read at least 1 note and answered both judged and offended yes/no questions, 2,411 (10.5%) reported ever feeling judged and/or offended by something they read. Among these, 608 (25.2%) felt judged, 748 (31.0%) felt offended, and 1,055 (43.8%) felt both judged and offended.

Using a difference of 5 percentage points between demographic groups as a threshold for meaningful differences, we found the following patterns: Those patients who (a) described their race as other, (b) rated their health fair/poor, (c) reported being unable to work, or (d) reported having read 4 or more notes were more likely than their counterparts to feel judged/offended. In contrast, patients who reported they were (a) Asian, (b) retired, or (c) male, were less likely than their relevant comparison groups to report feeling so (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Who Did and Did Not Feel Judged or Offended

| Demographic | Felt judged and/or offended N = 2411 | Felt neither judged nor offended N = 20548 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | N(%) | N(%) | P value |

| 18–24 | 84(10.8) | 692(89.2) | < 0.0001 |

| 25–44 | 573(11.2) | 4543(88.8) | |

| 45–64 | 1095(11.5) | 8428(88.5) | |

| 65 + | 659(8.7) | 6885(91.3) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1832(12.6) | 12658(87.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Male | 579(6.8) | 7890(93.2) | |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 57(4.9) | 1118(95.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Black | 68(11.9) | 502(88.1) | |

| White | 1835(10) | 16465(90) | |

| Other | 129(17.7) | 600(82.3) | |

| Multiple races | 110(14) | 676(86) | |

| Missing | 212(15.2) | 1187(84.8) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 92(11.3) | 724(88.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Non-Hispanic | 2130(10.2) | 18724(89.8) | |

| Missing | 189(14.7) | 1100(85.3) | |

| General health | |||

| Excellent, very good, or good | 1653(9) | 16783(91) | < 0.0001 |

| Fair or poor | 597(17.6) | 2791(82.4) | |

| Missing | 161(14.2) | 974(85.8) | |

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 113(7.8) | 1343(92.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Some college or technical school | 491(10.2) | 4323(89.8) | |

| 4-year college degree or some graduate school | 759(10.2) | 6705(89.8) | |

| Masters or doctoral degree | 889(10.9) | 7255(89.1) | |

| Missing | 159(14.7) | 922(85.3) | |

| Employment | |||

| Employed or self-employed | 1203(9.6) | 11288(90.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Homemaker | 72(11.8) | 536(88.2) | |

| Unemployed | 104(14.7) | 604(85.3) | |

| Retired | 585(8.6) | 6242(91.4) | |

| Unable to work | 268(22.8) | 905(77.2) | |

| Missing | 179(15.5) | 973(84.5) | |

| Language usually spoken at home | |||

| English | 2074(10.4) | 17891(89.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Spanish | 9(12) | 66(88) | |

| Other | 24(5.4) | 424(94.6) | |

| Multiple languages | 129(10.5) | 1094(89.5) | |

| Missing | 175(14) | 1073(86) | |

| Number of notes read | |||

| 1 | 105(6.2) | 1593(93.8) | < 0.0001 |

| 2 or 3 | 721(8.1) | 8137(91.9) | |

| 4 or more | 1489(13) | 9934(87) | |

| Don’t know/not sure | 96(9.8) | 884(90.2) | |

| Length of time reading notes | |||

| A week or less | 36(6.9) | 482(93.1) | < 0.0001 |

| More than a week, less than a year | 471(8.4) | 5120(91.6) | |

| A year or more | 1904(11.3) | 14946(88.7) | |

| Are you a healthcare professional? | |||

| Yes | 388(12.1) | 2816(87.9) | < 0.0001 |

| No | 1849(10) | 16721(90) | |

| Missing | 174(14.7) | 1011(85.3) | |

ap values from the chi-square test for independence

Results of Thematic Analysis

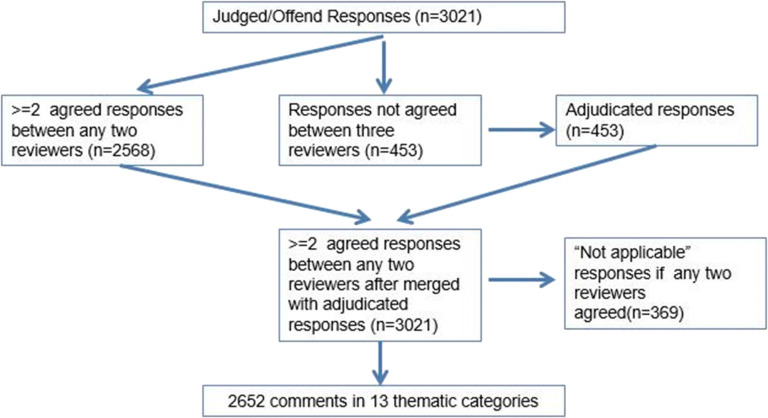

Of the 2,411 patients who said they felt judged and/or offended, 2,137 (84.5%) wrote free-text comments (Fig. 2). The median word count for responses was 18. There was moderate agreement among the 3 reviewers who assigned the 12 primary thematic codes to free-text responses (Fleiss’ Kappa: 0.469 p value < 0.001, indicating moderate agreement among the three raters). Of the 3021 responses reviewed, at least 2 out of 3 reviewers agreed on the thematic code for 2,652 (88.0%), and the 4th reviewer assigned codes to 453 comments in which there was no agreement. Table 2 displays representative comments from the thematic categories within the 3 domains.

Figure 2.

Overview of thematic analysis process.

Table 2.

Frequency and Proportion of Responses Reflecting Themes and Excerpts from Free-Text Responses

| Themes |

n of patients (N = 2034) |

Examples* (edited for length and spelling) |

|---|---|---|

| Errors and surprises | 715(35.2) | |

| Mistake/inaccuracy | 466 | • A note in my file that was put together using boilerplate cut-and-paste and includes several errors, including some of my conditions, family history, and my age and sex. It suggested a level of carelessness in record-keeping. There needs to be an easier way for the patient to request changes and I am really surprised at how much there is that is wrong. |

| • There are so many things that are incorrectly stated in the notes and I feel like I am saddled with them forever. | ||

| Did not happen in visit | 96 | • The doctor reports having made a number of statements and recommendations that he did not make. |

| Confidentiality concern | 81 | • I felt there was too much personal information written about me that I would prefer not be on there. It made me uncomfortable and it was not necessary in the context of my visit. |

| Diagnoses not discussed | 44 | • I read about a diagnosis we hadn’t discussed. If it’s important enough to go into my file, it’s important enough to tell me. |

| • The diagnosis on the notes was that I was suffering from depression but the doctor did not even mention that to me on the visit, that is what makes me keep reading the notes, to know what the dr, really think about me but did not said to me, that was very disappointing. | ||

| Lie (intentionality suggested) | 28 | • I wasn’t offended. It was actually betrayal. I felt that the MD had painted a much different picture than what they had written in my chart |

| Labeling | 661 | |

| Personal descriptors | 262 | • Provider called me ‘elderly’!!! Insolent pup!!! |

| • A description of my demeanor that I don't agree with and could have explained if I was asked about it. | ||

| Obesity | 194 | • Note said I wasn't doing everything I could to lose weight which was untrue and very upsetting to see my Dr thought of me like that. |

| • I was described as obese. Perhaps that is true according to some chart. ... I was quite taken aback and embarrassed by that description. ... After this I stopped reading notes. It wasn’t worth it to me to possibly feel bad about myself. | ||

| • I was described as overweight but it actually inspired me to lose weight | ||

| Stigma (other than above) | 171 | • While the note included something I had said during the appointment, it made it feel like if another provider read it out of context, there could have been judgement placed on what I said and how I expressed it during the appointment |

| Gender and sexuality | 34 | • Comments around my being gay |

| • Wrong gender | ||

| Disrespect | 653 | |

| Not heard/misquoted | 299 | • Pertinent info was left off–I often felt the need to offer MY interpretation of the visit–and there should be a place for this. Some of the notes presented me in a more negative light because my expressed rational concerns about taking some meds were not noted. |

| • ‘Offended’ may be too strong, but I was put off by a description of a discussion that I felt did not adequately represent my point of view, and differed from my interpretation of what I thought I had heard the doctor say. This was, however, very helpful to me... | ||

| Clinical language and conventions | 251 | • Use of the verb ‘denies’ as in: ‘Denies arms tingling, numbness or weakness.’ I did not deny these things. I said I didn’t feel them. Completely different. Language matters |

| • It’s simply the language that doctors are taught to use. Patient reports are considered ‘subjective’ and therefore cast as slightly unreliable. | ||

| Condescension | 103 | • It feels condescending, even when the comment is positive, when a doctor judges your personal character based on 5 minutes in an exam room. I feel like I’m reading my high school report card...assumptions being made, maybe based on race, gender, weight, etc. |

| Other | 403 | |

| • Too hard to explain. |

Errors and Surprises

This thematic domain included descriptions of finding inaccuracies in the record and instances when the note negatively surprised the patient. For example, patients reported feeling judged/offended due to documentation of physical examinations or discussions that the patient believed had not occurred. Some respondents referred to what they perceived as a deliberate lie, misrepresentation, or omission within the record. Many were surprised and judged/offended to find diagnostic terminology that had not been discussed with them. Others were surprised and troubled by how much personal information was contained within their notes. Several felt confidentiality was breached because they found unexpected documentation of something they felt was privately shared with the clinician. Some respondents were offended by diagnoses listed in the note that the clinician had not discussed or shared explicitly at the visit. Finally, patients reacted strongly to finding mental health diagnoses in the note that had not been discussed at the visit.

Labeling

Patients reported feeling judgment/offense when they felt they were labeled by clinicians. Descriptions of obesity were a frequent cause of feeling negatively labeled, as were other personal descriptors such as “elderly,” ”anxious,” “well-groomed,” or descriptions of patients’ emotional demeanor. Annotations about physical examinations were also cited as sources of feeling judged—particularly when related to general appearance, to dermatological or gynecological concerns, or to overall physical strength or ability. There was concern about possible transmission of bias: Several patients worried that some value-laden labels could render their concerns to be discounted by other clinicians in the future. Positive patient descriptions, such as “pleasant” or “delightful,” were deemed by some as unnecessary, as they suggested that their personality was being judged. Some patients also felt labeled by the way some notes described gender, sexuality, depression, anxiety, or their use of cigarettes, alcohol, or other substances.

Disrespect

Some patients felt disrespected when they perceived their perspective was not recorded, was misunderstood, was represented incorrectly, or was not valued. Respondents reacted negatively to language used by convention by clinicians, such as “patient claims” or “patient denies,” and particularly to phrasing that appeared to distort, dismiss, or question the validity of the patient’s perspective. Patients considered some notes “condescending,” although the specific content in the note that brought them to this conclusion was not always described. Many felt blamed for their health conditions or felt their symptoms were disbelieved, particularly when the symptom was painful. Some terms were misunderstood: the ICD 10 diagnosis, “Dizziness and Giddiness,” for example, was confusing—several understood the word “giddy” to be mocking or critical. Similarly, the neurological condition “pseudo-claudication” was interpreted by one patient as evidence that the clinician thought the patient’s symptoms were “fake” (Table 3). Some experienced terms such as “former-smoker” as blaming. Miscellaneous comments varied widely. For example, patients disliked statements regarding the amount of time spent in counseling and coordination of care, at times interpreting such boiler-plate sentences required for billing purposes as evidence of clinician impatience.

Table 3.

| Chief complaint | Primary concern/reason for visit instead of complaint |

| Obesity | Document the patient’s BMI. When needed, document obesity as a condition the patient has, not as an adjective. |

| Diabetes | Document diabetes as a condition or diagnosis, not as an adjective (diabetic) |

| Diabetes management | High A1c or hyperglycemia, rather than uncontrolled diabetes; A1C level is above X goal |

| Adherence | Has difficulty with treatment plan, rather than non-compliant: describe the behavior; e.g., she takes the medication only twice a week. She worries about relying too much on a medicine. |

| Drug use disorders | Use alcohol or substance use disorder, rather than describing patient as alcoholic, IVDU, addict; Urine tox was negative or contained no other drugs, rather than was clean or dirty |

| History | Does not or has not instead of denies (history of present illness is subjective/reported by its nature) |

| Gender | Ask and document gender identity and pronouns to match patient’s expressed identity |

| Age | Consider stating age, rather than describing patient as elderly |

| Difference in approach | Describe the difference and the patient’s reason: patient declines or chooses not to, or prefers not to for X reason, rather than refuses |

| Race/ethnicity | Adopt a consistent approach, rather than one that documents race/ethnicity only when the patient is not Caucasian |

| Sickle cell disease | Patient with Sickle Cell Disease, rather than sickler |

| General | Quotation marks may occasionally suggest skepticism |

DISCUSSION

In this large survey of patients who read visit notes, 1 in 10 respondents reported feeling judged and/or offended by something they read in their notes after finding perceived errors, surprises, labeling, or disrespect. Patients reacted negatively to clinical documentation that they thought did not accurately capture the visit, did not represent their perspective, or discounted their concerns. Patients who were unemployed or unable to work, and those with worse self-rated health, were more likely to report feeling judged or offended. Some “mistakes” and “inaccuracies” were perceived by their very nature as judgmental/offensive, perhaps because they suggested to patients a lack of attention or care. Conversely, notations that suggested disrespect/inattention to the patient’s concern were often described as inaccurate.

The finding that women, patients with poor self-rated health, and those unable to work felt more judged/offended should be studied further, but is not completely unexpected. Women patients and patients who are chronically ill and unable to work may feel, and may in fact be, more stigmatized generally; they might be more vigilant about how they are described in our notes. Cinicians may have more negative implicit attitudes about chronically ill patients and may sometimes consciously or unconsciously blame patients for their conditions in their language.16 Our finding reinforces the importance of actively considering whether language might be perceived as stigmatizing, particularly when writing about patients in poor health or about any patient who may frequently experience bias.

Implicit bias related to race, disability, and obesity play a role in clinician perception and assessment of patients,6,14,15,23,24 and we might expect this bias to reveal itself in clinicians’ notes. Patients may perceive indications of bias in the medical relationship through the note. Our survey did not ask specifically about discrimination, stereotyping, or issues of racial, ethnic, gender, or linguistic bias, and these were rarely cited explicitly as reasons for feeling offended/judged by participants, but several patients referred to “assumptions” which could be related to stereotyping, though the brief comments did not allow us to explore this. It is notable that patients who described their race as “other” had higher reports of feeling judged/offended. The finding that Asian patients were less likely in this survey to feel judged or offended merits further study to understand in more detail which Asian groups were represented, and to explore their experiences and expectations of the clinician-patient relationship and of notes specifically. Similarly, the finding that men, and patients who spoke a language other than English or Spanish at home, felt less offended/judged could be further explored. The experience and perception of what constitutes respectful or disrespectful language may vary among different cultural and social contexts.17 Few respondents had less than a high school education. Though we found slightly lower rates of reporting feeling judged or offended among such patients, this finding did not meet our 5% difference threshold.1 Respondents who described themselves as healthcare professionals (Are you a healthcare professional?) reported feeling judged/offended at rates similar to those who were not.

Standard medical language and conventions related to how notes are typically worded may sound “loaded” or condescending to some patients, although some patients forgave these expressions as language clinicians “are taught to use.” The theme of overweight/obesity, and choices related to documenting this topic, was commonly cited as a reason for why patients felt judged/offended. Patients in our study frequently objected to being described as obese, particularly when no discussion about weight had occurred in the visit. Guidelines suggest that obesity should be discussed empathically and noted as a medical condition or illness, rather than as a term characterizing the patient’s identity (e.g., patient with overweight/obesity instead of obese).13,25

Patients sometimes expressed surprise, dismay, and offense regarding the clinician’s decision to include certain details that patients had apparently thought they had shared “in confidence” in their visit. Without an explicit discussion of documentation practices, patients may assume that certain details will not be included in a note. Indeed, patients and clinicians may at times have strikingly different definitions of confidentiality: clinicians typically think that confidentiality means that information will only be shared with those involved in the patient’s care, and that documentation in the electronic medical record (EMR) of such information is within the domain of confidentiality.26 In contrast, patients may understand confidentiality to mean literally “off the record…” This study highlights the need for greater deliberation on the meaning of privacy in EMRs, and more frequent discussion between patient and clinician on the appropriate documentation of sensitive details.26

Further research is needed in order to understand in more detail what specific note content patients experience as positive and affirming, and what they find negative, worrisome, or confusing. When patients read clinical notes, their evaluation of the note is likely influenced by in-person interactions and the preexisting relationship with the clinician, which was not evaluated in this survey, an area worthy of further study. Might a positive interaction “protect” against the patient’s perception of judgment/disrespect in the notes, whereas a negative one prompt increased patient vigilance while reading the note? Might a “good” note improve the patient’s trust?

Medical schools and residency programs are only just beginning to teach learners how to support transparency in documentation; very few give learners specific patient-centered guidance for how to write about sensitive issues. Medical students, residents, and clinicians generally may benefit from increased education and feedback regarding the effects of shared notes, given that traditional recommendations regarding progress notes (e.g., “SOAP” notes) and clinic notes were developed without the expectation or perspectives of patients reading them.27–29

LIMITATIONS

Our survey respondents do not fully mirror the diversity of the US population, limiting the generalizability of our findings. In particular, the educational attainment of survey respondents is higher than that of the US population as a whole. Fewer patients from low income, lower education, minority, or limited English proficiency are active portal users,23,24 limiting our understanding of the note-reading experience of these populations. Our response rate of 21.7% was low, but in the expected range for an online survey and similar to the response rate in a recent Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Provider and Systems survey.30 Finally, there were some demographic differences between responders and non-responders,6 and while these differences were small, it is possible that survey respondents were more engaged and able to use open notes.

Survey free-text responses were generally short, and the precise reasons for why patients felt judged/offended were not always clear and the nature of the survey did not allow for follow-up with in-depth interviews, which may be of interest in future research. Our survey questions asked whether patients “ever” found a note judgmental/offensive; therefore, we cannot state precisely how many notes each patient found judgmental/offensive. Responses about feeling judged/offended were not attached to a specific note, and therefore we cannot correlate note content with responses.

IMPLICATIONS

This study reinforces the finding that that words do matter.11–13,18,31 Patients want their concerns documented carefully and respectfully and do not want to feel labeled or surprised by what they find in a note. Patients want clinicians to be honest and competent and to act in the patient’s best interest, qualities linked to trust in clinicians.4,14,15 The explanations for why patients felt judged/offended suggest that some of these expectations were not fully met from the patient’s perspective. We suggest that visit notes should reflect the content of the visit and record a patient’s perspective respectfully. Attention to these issues is especially important when writing notes about patients who are in poor health, who are unable to work, or who may frequently experience bias, and also critical when the patient and clinician disagree. Transparently acknowledging both perspectives (clinician’s and patients’) within a note and at the visit, without dismissing a patient’s concerns or symptoms, may help build trust. Asking oneself “how would I feel if this were written about me?” and “how might this sound if read by this patient?” may prompt clinicians to choose strength-based language that promotes mutual engagement.32 Others have made helpful suggestions for how we might improve the way we write about obesity, diabetes, sexual activity, and opiate and other drug use (Table 3).32–35 It may also be time to rethink the routine use of terms such as “refused,” “complains,” “admits,” and “non-compliant” among others. Increased awareness of the patient’s perspective on notes may prompt our medical lexicon to become less judgmental, reduce the transmission of bias to other clinicians, and reinforce healing therapeutic relationships.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Topister Bonyo for the help in coding, and Tobie Atlas, M.Ed., for her insightful comments on the earlier drafts of this article. The authors are also grateful to the patients for their input and responses and to all the colleagues on the OpenNotes team.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Peterson Center on Healthcare, and the Cambia Health Foundation.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Disclaimer

The funders had no role in designing or conducting the study, analyzing the data, preparing the manuscript, or deciding to submit this manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors had financial support for the submitted work from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Peterson Center on Healthcare, and the Cambia Health Foundation.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

SGIM National Meeting 2018, What's in a Note. Workshop Presentation

Words Matter. Harvard Medical School Academy, Poster Presentation

Words Matter:Insight from a Survey, OpenNotes Grand Rounds Webinar, 2019

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bell SK, Gerard M, Fossa A, Delbanco T, Folcarelli PH, Sands KE, et al. A patient feedback reporting tool for OpenNotes: implications for patient-clinician safety and quality partnerships. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 [cited 2019 Mar 27];26:312–22. 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Kleinman A. Medical sensibility: whose feelings count? Lancet. 2013;381(9881):1893–4. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673613611460. Accessed 9 July 2020

- 3.Gerard M, Fossa A, Folcarelli PH, Walker J, Bell SK. What patients value about reading visit notes: A qualitative inquiry of patient experiences with their health information. J Med Internet Res. 2017 [cited 2019 Mar 26];19(7):e237. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28710055. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Bell SK, Folcarelli P, Fossa A, Gerard M, Harper M, Leveille S, et al. Tackling Ambulatory Safety Risks Through Patient Engagement: What 10,000 Patients and Families Say About Safety-Related Knowledge, Behaviors, and Attitudes After Reading Visit Notes. J Patient Saf. 2018;00(00):1–9. Available from: http://links.lww.com/JPS/A152. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Gerard M, Chimowitz H, Fossa A, Bourgeois F, Fernandez L, Bell SK. The Importance of Visit Notes on Patient Portals for Engaging Less Educated and Nonwhite Patients: Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(5):e191. Available from: http://www.jmir.org/2018/5/e191/. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Walker J, Leveille S, Bell S, Chimowitz H, Dong Z, Elmore JG, et al. OpenNotes After 7 Years: Patient Experiences With Ongoing Access to Their Clinicians’ Outpatient Visit Notes. J Med Internet Res. 2019 6 [cited 2019 May 6];21(5):e13876. Available from: https://www.jmir.org/2019/5/e13876/. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Mishra V, Hoyt R, Wolver S, Yoshihashi A, Banas C. Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Patients’ Perceptions of the Patient Portal Experience with OpenNotes. Appl Clin Inform. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 14];10(01):010–8. Available from: http://www.thieme-connect.de/DOI/DOI?10.1055/s-0038-1676588. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Nazi KM, Turvey CL, Klein DM, Hogan TP, Woods SS. VA OpenNotes: exploring the experiences of early patient adopters with access to clinical notes. J Am Med Informatics Assoc [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2018 Feb 16];22(2):380–9. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jamia/article-lookup/doi/10.1136/amiajnl-2014-003144. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Bell SK, Mejilla R, Anselmo M, Darer JD, Elmore JG, Leveille S, et al. When doctors share visit notes with patients: a study of patient and doctor perceptions of documentation errors, safety opportunities and the patient-doctor relationship. BMJ Qual Saf [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Aug 6];26:1–9. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Desroches CM, Leveille S, Bell SK, Dong ZJ, Elmore JG, Fernandez L, et al. The Views and Experiences of Clinicians Sharing Medical Record Notes With Patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):1–12. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goddu AP, O’Conor KJ, Lanzkron S, Saheed MO, Saha S, Peek ME, et al. Do Words Matter? Stigmatizing Language and the Transmission of Bias in the Medical Record. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 May 26 [cited 2018 Jul 26];33(5):685–91. Available from: https://link-springer-com.libezproxy2.syr.edu/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs11606-017-4289-2.pdf. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Gudzune KA, Bennett WL, Cooper LA, Bleich SN. Patients who feel judged about their weight have lower trust in their primary care providers. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97(1):128–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanford FC, Kyle TK. Respectful Language and Care in Childhood Obesity. JAMA Pediatr. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Birkhäuer J, Gaab J, Kossowsky J, Hasler S, Krummenacher P, Werner C, et al. Trust in the health care professional and health outcome: A meta-analysis. Nater UM, editor. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0170988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Wilk AS, Platt JE. Measuring physicians’ trust: A scoping review with implications for public policy. Soc Sci Med. 2016 [cited 2019 Feb 15];165:75–81. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277953616304002. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Fitzgerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Beach MC, Branyon E, Saha S. Diverse patient perspectives on respect in healthcare: A qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100(11):2076–80. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0738399117302653. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Grob R, Darien G, Meyers D. Why Physicians Should Trust in Patients. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2019.

- 19.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95(December 2018):103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)-A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kidia K. Tweetorial 4 New Interns [Internet]. Twitter.com. 2020. Available from: https://twitter.com/kkidia/status/1275460547883008000. Accessed 9 July 2020

- 22.Power-Hays A, McGann PT. When Actions Speak Louder Than Words - Racism and Sickle Cell Disease. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2020;1969–73. Available from: nejm.org. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Lyles C, Schillinger D, Sarkar U. Connecting the dots: Health information technology expansion and health disparities. PLoS Med. 2015 [cited 2017 Dec 13];12(7). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4501812/pdf/pmed.1001852.pdf. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Lyles CR, Sarkar U. Health Literacy, Vulnerable Patients, and Health Information Technology Use: Where Do We Go from Here? J Gen Intern Med. 2015 [cited 2018 Jan 25];30(3):271–2. Available from: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs11606-014-3166-5.pdf. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Durrer Schutz D, Busetto L, Dicker D, Farpour-Lambert N, Pryke R, Toplak H, et al. European Practical and Patient-Centred Guidelines for Adult Obesity Management in Primary Care. Obes Facts. 2019;12(1):40–66. doi: 10.1159/000496183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen N, Bernier T, Sequeira L, Strauss J, Silver MP, Carter-Langford A, et al. Understanding the patient privacy perspective on health information exchange: A systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2019;125(October 2018):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crotty BH, Anselmo M, Clarke D, Elmore JG, Famiglio LM, Fossa A, et al. Open Notes in Teaching Clinics: A Multisite Survey of Residents to Identify Anticipated Attitudes and Guidance for Programs. J Grad Med Educ 2018;10(3):292–300. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29946386%0A, http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC6008043%0A, http://www.jgme.org/doi/10.4300/JGME-D-17-00486.1. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Niedermier VE. Teaching Electronic Health Record Documentation to Medical Students. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(1):135. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28261413. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Gagliardi JP, Turner DA. The Electronic Health Record and Education: Rethinking Optimization. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):325–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27413432. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.NORC. Methodology Report: 2014-2015 Nationwide CAHPS Surveys of Adults Enrolled in Medicaid between October and December 2013 [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/downloads/performance-measurement/methodology-report.pdf. Accessed 9 July 2020

- 31.Porter AS, Callaghan JO, Englund KA, Lorenz RR, Kodish E. Problems with the problem list: challenges of transparency in an era of patient curation. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2020;0(0):1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Dickinson JK, Guzman SJ, Maryniuk MD, O’Brian CA, Kadohiro JK, Jackson RA, et al. The use of language in diabetes care and education. Diabetes Care. 2017 [cited 2020 Jul 14];40(12):1790–9. Available from: 10.2337/dci17-0041. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.National Health Service England. Language Matters: Language and Diabetes. 2018 [cited 2020 Jul 14]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/language-matters.pdf

- 34.Moore MD, Ali S, Burnich-Line D, Gonzales W, Stanton MV. Stigma, Opioids, and Public Health Messaging: The Need to Disentangle Behavior From Identity. Am J Public Health. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 14];110(6):807–10. Available from: http://ajph.aphapublications.org/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Marcus JL, Snowden JM. Words Matter: Putting an End to “unsafe” and “risky” Sex. Vol. 47, Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 14]. p. 1–3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6953392/. Accessed 9 July 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available.