INTRODUCTION

Outpatient antibiotic prescribing is a major driver of antimicrobial resistance, which causes 35,000 US deaths per year.1 Stewardship initiatives are typically broad-based, but antibiotic-specific initiatives may be warranted if particular antibiotics disproportionately account for inappropriate prescribing.

Previously, we developed a scheme classifying whether each ICD-10-CM diagnosis code “always,” “sometimes,” or “never” justifies antibiotics.2 Using this scheme, we estimated that 23% of antibiotic prescriptions among privately insured Americans in 2016 were for antibiotic-inappropriate conditions.2 However, we did not assess inappropriate prescribing by antibiotic or include the publicly insured. We address these gaps using 2018 commercial and Medicaid claims.

METHODS

We analyzed the 2018 IBM MarketScan Commercial and Multi-State Medicaid Databases. The former includes 27 million enrollees with employer-sponsored insurance; the latter includes 12 million publicly insured enrollees from several states.3 We included non-dual eligible enrollees aged 0–64 years continuously enrolled throughout 2018. The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board exempted this study from review.

We identified pharmacy claims for 39 oral antibiotics included in a national quality measure.4 Following our prior study, we compiled diagnosis codes on medical claims occurring during a look-back period that began three days prior to the antibiotic claim date and ended on this date.2 We assigned claims to one of four categories: (1) “Appropriate” if associated with ≥ 1 “always” diagnosis code during the look-back period; (2) “Potentially appropriate” if associated with ≥ 1 “sometimes” code but no “always” codes; (3) “Inappropriate” if associated only with “never” codes; and (4) “Not associated with a recent diagnosis code” if there were no codes during the look-back period (e.g., non-visit-based prescribing2,5). For example, if the look-back period contained codes for pneumonia (an “always” code) and sinusitis (a “sometimes” code), the claim was classified as appropriate. If only sinusitis was coded, the claim was classified as potentially appropriate.

We calculated the proportion of claims in each category overall, by age (adults aged ≥ 18 years versus children), by age and payer type (public versus private), and by an antibiotic. For adults and children, we calculated the proportion of antibiotic claims and inappropriate claims accounted for by each antibiotic.

RESULTS

The 24,850,477 enrollees included had mean (SD) age of 31 (19) years; were 33% children, 52% female, and 26% publicly insured; and had 18,711,397 antibiotic claims (753 per 1000). Of all enrollees, 9,258,637 (37%) had ≥ 1 antibiotic claim. Of all claims, 14% were appropriate, 38% were potentially appropriate, 22% were inappropriate, and 26% were not associated with a recent diagnosis code (Table 1).

Table 1.

Appropriateness of Antibiotic Claims Among Non-Elderly Adults and Children in 2018

| Antibiotic | # claims | % of all antibiotic claims | % of all inappropriate antibiotic claims | % appropriate | % potentially appropriate | % inappropriate | % not associated with a recent diagnosis code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-elderly adults | |||||||

| Azithromycin | 1,938,177 | 15 | 22 | 6 | 32 | 37 | 25 |

| Amoxicillin | 2,050,660 | 16 | 10 | 7 | 25 | 16 | 52 |

| Doxycycline | 1,279,854 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 36 | 26 | 33 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 1,616,381 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 56 | 17 | 18 |

| Cephalexin | 968,483 | 7 | 9 | 13 | 35 | 28 | 24 |

| TMP-SMX | 967,476 | 7 | 7 | 21 | 32 | 24 | 23 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 704,092 | 5 | 7 | 33 | 13 | 32 | 23 |

| Metronidazole | 673,804 | 5 | 5 | 17 | 30 | 24 | 30 |

| Nitrofurantoin | 631,888 | 5 | 5 | 46 | 5 | 24 | 26 |

| Levofloxacin | 416,089 | 3 | 4 | 21 | 31 | 30 | 18 |

| Other antibiotics | 1,887,062 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 31 | 20 | 39 |

| Subtotal, adults | 13,133,966 | 100a | 100 | 13 | 32 | 24 | 31 |

| Children | |||||||

| Amoxicillin | 2,389,839 | 43 | 35 | 21 | 53 | 14 | 12 |

| Azithromycin | 708,356 | 13 | 25 | 16 | 40 | 33 | 12 |

| Cefdinir | 671,944 | 12 | 11 | 15 | 62 | 15 | 7 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 630,331 | 11 | 9 | 13 | 64 | 14 | 9 |

| TMP-SMX | 278,247 | 5 | 6 | 19 | 43 | 20 | 19 |

| Cephalexin | 236,696 | 4 | 4 | 20 | 52 | 17 | 12 |

| Doxycycline | 147,699 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 35 | 11 | 52 |

| Clindamycin | 110,118 | 2 | 1 | 14 | 51 | 12 | 22 |

| Cefprozil | 60,115 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 58 | 18 | 8 |

| Minocycline | 110,796 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 28 | 9 | 63 |

| Other antibiotics | 232,952 | 5 | 4 | 24 | 23 | 20 | 32 |

| Subtotal, children | 5,577,093 | 100a | 100a | 18 | 51 | 17 | 15 |

| Total, adults and children | 18,706,985 | 100 | 100 | 14 | 38 | 22 | 26 |

The table displays the ten antibiotics accounting for the highest proportions of inappropriate claims in each age group. Among adults, amoxicillin and doxycycline accounted for 10.4% and 10.2% of inappropriate claims. To assess appropriateness, we used our previously developed classification scheme of ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes (available online; reference #2). The scheme was developed using a consensus-based approach among three authors with expertise in claims analysis, internal medicine, and pediatrics

Abbreviations: TMP-SMX trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

aSum of the rows above do not equal 100 due to rounding

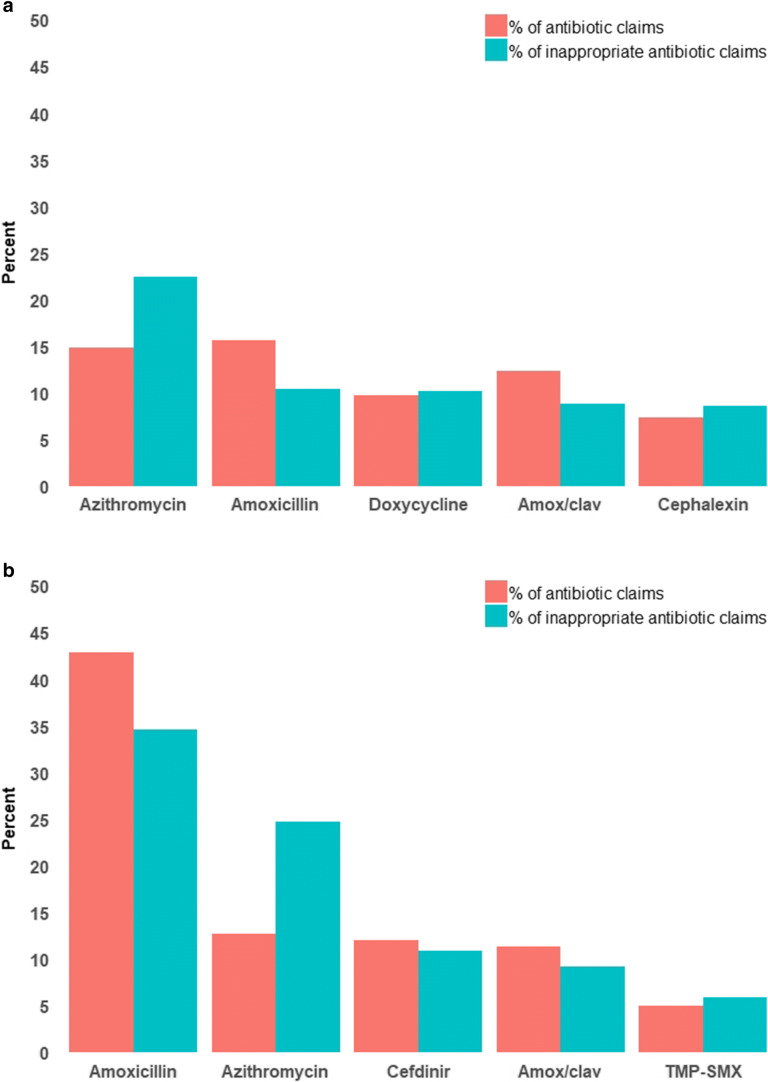

Among adults, 24% of claims were inappropriate (26% vs 24% for publicly and privately insured). Amoxicillin accounted for the highest proportion of claims (16%) and the second highest proportion of inappropriate claims (10%). Azithromycin accounted for the second highest proportion of claims (15%) and the highest proportion of inappropriate claims (22%) (Fig. 1a). 37% of azithromycin claims were inappropriate.

Figure 1.

Percentage of antibiotic claims and inappropriate antibiotic claims accounted for by each antibiotic. a Adults aged 18‐64 years; b Children aged 0‐17 years. The graph includes the five antibiotics accounting for the highest proportion of inappropriate antibiotic claims in each age group. Abbreviations: Amox/clav: amoxicillin/clavulanate; TMP‐SMX: trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Among children, 17% of claims were inappropriate (18% vs 15% for publicly and privately insured). Amoxicillin accounted for the highest proportion of claims (43%) and inappropriate claims (35%). Azithromycin accounted for the second highest proportion of claims (13%) and inappropriate claims (25%) (Fig.1b). 33% of azithromycin claims were inappropriate.

DISCUSSION

We provide the most recent data on outpatient antibiotic appropriateness among privately and publicly insured non-elderly US patients.2,5 In our analysis, 22% of antibiotic claims were inappropriate. Azithromycin had an outsized role in inappropriate prescribing. Among adults, azithromycin accounted for the most inappropriate antibiotic claims despite being the second most commonly prescribed antibiotic. Among children, azithromycin accounted for 25% of inappropriate antibiotic claims, even though it only accounted for 13% of antibiotic claims. In both ages, approximately one-third of azithromycin claims were inappropriate. Findings are consistent with a prior study in which azithromycin was the most commonly prescribed antibiotic for respiratory infections that did not warrant antibiotics.6

Because we relied on diagnosis codes to assess appropriateness, we might have misclassified appropriate prescriptions as inappropriate if diagnoses justifying antibiotics were not coded. Overall, however, results likely underestimate inappropriate prescribing, as 38% of antibiotic claims were only potentially appropriate, and 26% were not associated with diagnosis codes.

Broad-based stewardship initiatives remain important given widespread inappropriate prescribing of all antibiotics. However, azithromycin-focused initiatives may be needed due to its especially high rate of use and inappropriate use.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to Dr. Linder (R01HS024930). Dr. Linder is also supported by other grants and contracts from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS026506; HHSP2332015000201) and by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R33AG057383), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R33AG057395), and The Peterson Center on Healthcare. Dr. Chua is supported by a career development award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant number 1K08DA048110-01).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board exempted this study from review.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Linder reports receiving grants and contracts from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Disclaimer

The funding sources played no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and the decision to approve publication of the finished manuscript.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

This manuscript was presented online at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting on August 7, 2020.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States: 2019. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chua KP, Fischer MA, Linder JA. Appropriateness of outpatient antibiotic prescribing among privately insured US patients: ICD-10-CM based cross sectional study. BMJ. 2019;364:k5092. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.IBM. IBM MarketScan Research Databases for Health Services Researchers. 2019; https://www.ibm.com/downloads/cas/6KNYVVQ2. Accessed February 8, 2020.

- 4.National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS 2018 Final NDC Lists. 2018; https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/hedis-2018-ndc-license/hedis-2018-final-ndc-lists. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- 5.Fischer MA, Mahesri M, Lii J, Linder JA. Non-infection-related and non-visit-based antibiotic prescribing is common among Medicaid patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020;39(2):280–288. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Havers FP, Hicks LA, Chung JR, et al. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections during influenza seasons. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180243. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]