Abstract

Background

Brief, stand-up meetings known as huddles may improve clinical care, but knowledge about huddle implementation and effectiveness at the frontlines is fragmented and setting specific. This work provides a comprehensive overview of huddles used in diverse health care settings, examines the empirical support for huddle effectiveness, and identifies knowledge gaps and opportunities for future research.

Methods

A scoping review was completed by searching the databases PubMed, EBSCOhost, ProQuest, and OvidSP for studies published in English from inception to May 31, 2019. Eligible studies described huddles that (1) took place in a clinical or medical setting providing health care patient services, (2) included frontline staff members, (3) were used to improve care quality, and (4) were studied empirically. Two reviewers independently screened abstracts and full texts; seven reviewers independently abstracted data from full texts.

Results

Of 2,185 identified studies, 158 met inclusion criteria. The majority (67.7%) of studies described huddles used to improve team communication, collaboration, and/or coordination. Huddles positively impacted team process outcomes in 67.7% of studies, including improvements in efficiency, process-based functioning, and communication across clinical roles (64.4%); situational awareness and staff perceptions of safety and safety climate (44.6%); and staff satisfaction and engagement (29.7%). Almost half of studies (44.3%) reported huddles positively impacting clinical care outcomes such as patients receiving timely and/or evidence-based assessments and care (31.4%); decreased medical errors and adverse drug events (24.3%); and decreased rates of other negative outcomes (20.0%).

Discussion

Huddles involving frontline staff are an increasingly prevalent practice across diverse health care settings. Huddles are generally interdisciplinary and aimed at improving team communication, collaboration, and/or coordination. Data from the scoping review point to the effectiveness of huddles at improving work and team process outcomes and indicate the positive impact of huddles can extend beyond processes to include improvements in clinical outcomes.

Study Registration

This scoping review was registered with the Open Science Framework on 18 January 2019 (https://osf.io/bdj2x/).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-021-06632-9.

KEY WORDS: communication, cooperative behavior, group processes, patient care teams, quality improvement

INTRODUCTION

Brief, focused, stand-up meetings known as huddles have the potential to improve medical care by enabling collaborative and efficient information exchange and fostering a shared view of current clinical conditions.1 Huddles have been shown to minimize hierarchical barriers to care delivery, enhance frontline staff satisfaction, and improve clinical outcomes.2 In contrast to historically dominant provider-centric medical practice models, huddles operationalize medicine as a cooperative science: all team members (e.g., physicians, nurses, medical assistants, administrative staff, laboratory workers) work together for the patient’s good,3 promoting stronger teamwork and communication4 and situation awareness on the unit floor.1 This increased communication with and among members of the team may also lead to better understanding of the daily work of frontline staff, potentially a key to sustaining quality improvement.5

Ideally, huddles optimize participant engagement, last 10–15 min, focus only on essential patient and procedural information,1,6 and are held on a regular basis;7 in practice, however, huddles take many forms. Some may involve only the patient’s immediate clinical team, meeting as needed at the patient’s bedside.8 Others may involve all clinical and non-clinical staff and be scheduled for the start of each workday or other regular interval.9 Huddle structure may also vary, depending, in part, on the use of any facilitation strategies, scripts, or communication tools such as CUS (“I am concerned! I am uncomfortable! This is a safety issue!”)10 or SBAR (Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation).11 Yet despite understanding some of the myriad variations in huddle structures and processes, knowledge of huddle implementation and effectiveness at the frontlines of health care remains fragmented and is limited to particular settings. In a preliminary search for relevant reviews available through MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and JBI Evidence Synthesis, we found three systematic reviews focusing on the use of huddles: one to promote patient safety in the perioperative setting2 and two focused on their use in inpatient settings.12,13 A more comprehensive understanding of huddle practices and characteristics has the potential to help clinicians and health care administrators across diverse settings understand how this process can help improve patient care.

In contrast to the prior, narrow systematic reviews on huddles in specific settings, this scoping review thus provides a comprehensive overview of the scope and volume of research on the broad category of clinical-setting huddles that involve frontline staff. In keeping with standard indications for conducting a scoping review,14 this review has the following purposes: to describe characteristics of such huddles (e.g., structures, processes), identify empirical support for the effectiveness of huddles for improving health care quality, and highlight knowledge gaps and opportunities for more detailed evidence syntheses and empirical research.

METHODS

We performed this scoping review using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s established method for a scoping review15 and guidance from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR).16 The final protocol was prospectively registered with the Open Science Framework17 on 18 January 2019 (https://osf.io/bdj2x/) and published in the peer-reviewed literature.18

Scope of the Review

We used the PCC (Population, Concept, and Context) framework to define eligibility criteria.16 To be eligible for inclusion, articles had to (1) take place in any clinical or medical setting that provides health care patient services, including inpatient, outpatient, or residential settings; (2) include frontline staff members (i.e., employees with patient contact, including health care providers and non-clinical/administrative staff);19 (3) describe, investigate, or explore the huddling practice as a targeted intervention to improve processes and outcomes broadly related to quality of care (e.g., staff engagement and satisfaction, perceptions of safety culture, adverse drug events, patient length of stay); and (4) provide empirical data. Eligible study designs included qualitative studies; experimental and quasi-experimental studies (e.g., randomized or non-randomized controlled trials, before and after studies, interrupted time-series studies); analytic observational studies (e.g., prospective or retrospective cohort studies, case-control studies); and descriptive cross-sectional studies. Dissertations, gray literature, and conference proceedings that met inclusion criteria were also considered. We excluded study protocols; articles that described huddles as a platform through which other interventions were disseminated; articles that solely focused on adherence to a checklist (e.g., surgical safety checklist); simulation studies, and research summaries lacking original data.

Data Sources and Searches

To be as comprehensive as possible, we performed an initial limited search of PubMed and CINAHL Plus with Full Text, followed by an analysis of each identified article’s title, abstract, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms, and keywords. For our full search, we used all resulting relevant MeSH terms and keywords to search the following databases: PubMed, EBSCOhost (including CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Dentistry & Oral Sciences Source, ERIC, Health Business Elite, Health Policy Reference Center, PsycArticles, PsycBooks, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, PsycINFO, Rehabilitation & Sports Medicine Source, Social Work Reference Center, and SocINDEX with Full Text), ProQuest (including the Family Health Database, Health & Medical Collection, Health Management Database, Nursing & Allied Health Database, Psychology Database, and PTSDpubs), and OvidSP. Appendix 1 lists the full search strategy used for PubMed, CINAHL Plus with Full Text, EBSCOhost, ProQuest, and OvidSP. We augmented the full database search by scanning the reference list of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s (IHI’s) white paper that guides health care practitioners in using daily huddles as part of a quality management system5 for additional articles that we then assessed. Studies published in English from inception to May 31, 2019, were considered for inclusion.

Study Selection

All articles identified during the full database and additional searches were uploaded into EndNote X8.2 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), and duplicates were removed. We conducted an initial screening for inclusion based on titles and abstracts. Two reviewers (C.B.P., C.W.H.) independently conducted the first screening of the abstracts based on the inclusion criteria to identify articles to include for further review. Disagreements on article inclusion were resolved by discussion or with input from two additional reviewers.

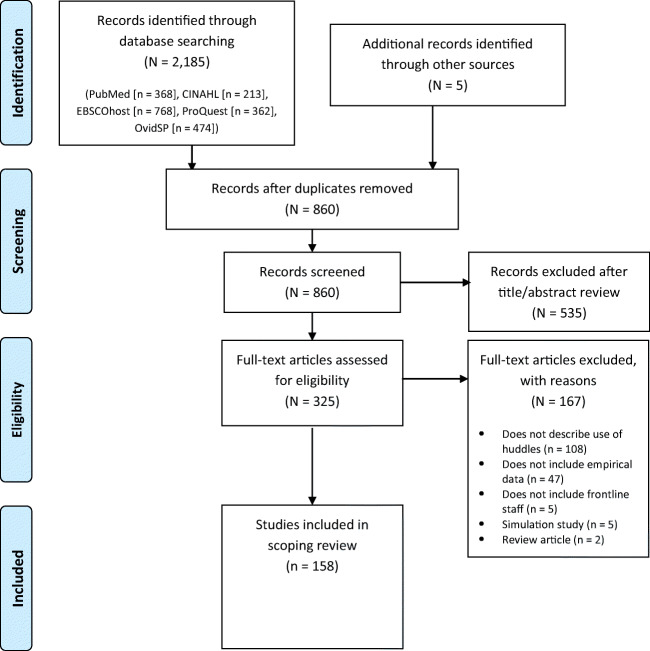

Following this, we reviewed the full text of those articles that met initial screening. Two independent reviewers assessed each article against the inclusion criteria, with disagreements resolved through discussion or with input from a third reviewer. Full-text articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded from the scoping review. Results of the search are presented in a PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).16

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Data Abstraction and Quality Assessment

Seven reviewers independently abstracted relevant data from each full-text article meeting all inclusion criteria. An Excel spreadsheet was used to collect data about, for example, clinical setting, study design, huddle purpose, participating staff, and indicators of huddle effectiveness. The data abstraction tool is available in Appendix 2. To summarize huddle purpose, we began with an adapted list of the four benefits of huddles as outlined by the IHI (engage, update, recognize, and identify)20 and added two additional ones based on our findings (plan, provide) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Huddle Purpose and Outcome Measures (N=158 Articles)

| Huddle purpose*† | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|

| Related to work and team process | Related to clinical care | |

| Engage team members in thinking and talking about their work; improve communication, collaboration, and/or coordination21–24 |

Improved efficiency, process-based functioning and communication across clinical roles 6,8,25–73 Improved situational awareness and staff perceptions of safety6,8,11,26,30,31,35–37,40,45–47,53,55–57,60,62,63,67–69,71,73–86 Increased staff satisfaction and engagement6,8,11,30,33,38,41,47,49,58,60,62,68,69,77,79,85,87–89 More supportive practice climate6,8,11,28,30,40,43,47,49,50,57,58,62,66–69,71,79,84,85,90,91 Enhanced self-efficacy among frontline staff to implement evidence-based practices30,34,38,48,51,54,58,66,71,77,81,87,92–95 |

Increased proportion of patients receiving timely, evidence-based assessment or treatment27,30,41,51,94,97,99–108 Decreased medical errors and adverse events11,25,50,86,109–113 Decreased length of hospital stay30,49,94,114–118 Decreased rate of negative outcomes, such as infections, falls, and pressure ulcers31,89,94,97,119–122 |

| Update team members about safety and quality issues that affect their work, including reviewing prior issues (108, 111, 119, 141, 149, 159) |

Improved efficiency, process-based functioning and communication across clinical roles6,29,32,40,57,72,73,125–127 Improved situational awareness and staff perceptions of safety6,40,57,73,77,83,128,129 Increased staff satisfaction and engagement6,77,87,89,127,128,130 More supportive practice climate6,40,57,127 Enhanced self-efficacy among frontline staff to implement evidence-based practices29,77,87,127,131 |

Increased proportion of patients receiving timely, evidence-based assessment or treatment132,133 Decreased medical errors and adverse events110,111,113,128,134–136 Decreased length of hospital stay118 Decreased rate of negative outcomes, such as infections, falls, and pressure ulcers89,122,125,130,133,137 Increased patient satisfaction123 |

| Plan for future work/improving processes for future work (108, 128, 129, 149, 162) |

Improved efficiency, process-based functioning and communication across clinical roles9,31,34,50,55,57,59,60,66,69,71,140–145 Improved situational awareness and staff perceptions of safety31,55,57,60,69,71,84,145–147 Increased staff satisfaction and engagement59,60,69,130,142,148 More supportive practice climate9,50,57,66,69,71 Enhanced self-efficacy among frontline staff to implement evidence-based practices34,66,71,93,148 |

Increased proportion of patients receiving timely, evidence-based assessment or treatment100,108,132,149 Decreased medical errors and adverse events121,134,135 Decreased length of hospital stay144 Decreased rate of negative outcomes, such as infections, falls, and pressure ulcers31,122,130,150 |

| Recognize work-related issues that can be addressed by training, coaching, and revising tools and methods (119) |

Improved efficiency, process-based functioning and communication across clinical roles40,57,62 Improved situational awareness and staff perceptions of safety40,57,62 Increased staff satisfaction and engagement89 More supportive practice climate40,57,62 Other57 |

Decreased medical errors and adverse events112 Decreased rate of negative outcomes, such as infections, falls, and pressure ulcers89,152 |

| Identify issues requiring immediate attention or escalation to higher-level management for resolution (54, 84, 111, 141) |

Improved efficiency, process-based functioning and communication across clinical roles8,9,25,27,29,30,32,37,39,44,53,55,57,59,63,69,126,144,153–155 Improved situational awareness and staff perceptions of safety8,30,37,53,55,57,63,69,75,84,146,153,156 Increased staff satisfaction and engagement8,30,37,59,63,69,87,156,157 More supportive practice climate8,9,30,57,69,84,154,156 Enhanced self-efficacy among frontline staff to implement evidence-based practices30,87,93,154 |

Increased proportion of patients receiving timely, evidence-based assessment or treatment27,30,149,158–160 Decreased medical errors and adverse events1,25,134,161 Decreased length of hospital stay30,116,144,157,162 Decreased rate of negative outcomes, such as infections, falls, and pressure ulcers122 |

| Provide a framework for running PDSA cycles |

Decreased medical errors and adverse events163 Other164 |

|

*List of huddle purposes adapted from IHI20

†Citations in Huddle Purpose column represent articles that characterized a huddle purpose(s) but did not characterize a specific outcome(s)

Two secondary reviewers (C.B.P., C.W.H.) independently abstracted relevant data from all full-text articles to assess consistency with primary reviewers. As in the study selection process, disagreements between primary and secondary reviewers were resolved through team discussion or in consultation with a third reviewer. We did not perform formal assessments of methodological quality because a scoping review aims to provide an overview of the existing evidence, irrespective of quality.15,16 We did categorize studies by evidence quality (e.g., peer-reviewed, gray literature, presence of a control comparison group), however, to inform future research.

Role of the Funding Source

This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care, through the VA Community Living Centers’ Ongoing National Center for Enhancing Resources and Training. The funder had no role in study design or conduct, data collection, analysis or interpretation, or reporting.

RESULTS

We identified a total of 2,185 publications through electronic database searches and reference lists (Fig. 1). After removal of duplicate publications across databases (N=1,330) and exclusion after initial title and abstract review (N=535), we performed full-text review of 325 studies. Two researchers (a primary and secondary reviewer) independently reviewed each article, with 90% agreement between both reviewers prior to resolution through team discussion or in consultation with a third reviewer. One-hundred fifty-eight studies met inclusion criteria;1,6,8,9,11,21–173 139 (88.0%) were peer-reviewed and 19 (12.0%) were gray literature. Details related to our broad objectives are summarized below. Select details on the included studies are available in Appendix 3.

Year and Location of Studies

The first study meeting eligibility criteria was published in 2004;11 the majority (71.5%; N=113) were published between 2014 and 2019.8,9,21,22,25,27,30–32,34–37,39,41–44,47–49,51,53,56–58,62,63,65,67–70,72,74,76,77,79,81,83,85,87,89,90,92–94,96,97,99–102,104–108,110–113,115–120,122–139,141,142,144,146–150,152–159,161–170,173 Seventy-four percent (N=117) were performed in the USA,1,6,8,9,11,21,23,25,27,28,30,33–35,37–40,42–44,46–53,55–62,64,65,69,71,72,74,76–78,84–89,91,93,96–102,104,106,107,109,112,114–126,128–132,135–147,149–153,155,156,158–161,164–170,172,173 13.9% (N=22) in the UK,22,26,29,31,36,41,54,63,67,70,75,79,83,92,94,105,110,111,113,133,154,162 8.9% (N=14) in Canada,24,32,45,68,73,80,82,90,103,108,127,134,157,171 and 3.2% elsewhere (the Netherlands [N=2],81,163 Thailand [N=1],95 Israel [N=1],66 and Australia [N=1]148).

Clinical Setting

A majority (30.4%; N=48) of all studies described implementation of huddle-based interventions throughout entire hospitals or health care systems.1,6,21,23,25,28,30,37,39,41,42,47,56,57,62,63,71,73,74,83,87,89,91,94,98,104,105,109,114,115,117,123,125,128–131,133,135–137,143,150,160,162,165,169,170 Specific unit-level clinical settings included the following: perioperative settings/operating room (15.2%; N=24),11,24,26,29,38,45,46,52,59,65,66,70,75,76,78–82,84,86,95,103,113 intensive care units (12.7%; N=20),33,44,50,61,77,88,96,108,110,112,121,124,138,140,151,152,159,163,171,172 inpatient medical or surgical departments (13.3%; N=21),35,49,51,54,60,67,85,92,99–101,111,116,118,141,147,154,155,157,168,173 long-term care facilities (6.3%; N=10),31,40,97,120,122,127,132,139,148,166 primary care (6.3%; N=10),43,55,58,64,68,69,93,142,149,164 emergency departments (5.1%; N=8),8,90,145,146,151,153,158,161 and labor and delivery (3.8%; N=6).53,72,119,126,156,167 Two percent or fewer studies were specific to each of the following settings: neurology and stroke (N=3),34,107,144 oncology (N=2),48,98 dental (N=2),22,36 behavioral health (N=2),27,139 pathology (N=1),32 radiology (N=1),9 cystic fibrosis (N=1),102 outpatient echocardiography laboratory (N=1),106 and brain and spinal cord rehabilitation (N=1).134

Study Design

Among peer-reviewed studies, 107 used quantitative methods only and 32 used qualitative or mixed methods. Among studies in the gray literature, 18 used quantitative and 1 used qualitative methods.

Only 9 studies (5.7%), all from the quantitative peer-reviewed literature, used a comparison group design.38,49,87,90,115,121,138,141,162 Nearly half of all studies (N=75) were analytic observational,1,23,26,28,31,34,37,41,46–48,50,51,55,58–61,67,71,72,74–80,83,84,86,89,91,94,96,97,99,101,106,107,109–112,115,117,119,123,125,128–130,132–134,137,140,142,143,146–148,150,153,157–161,163,166–168,170,172 34.2% (N=54) were experimental or quasi-experimental,8,11,27,29,32,33,35,38,42,43,45,49,51–53,56,65,70,73,81,85,87,90,92,95,102–105,108,113,114,116,118,120–122,124–126,131,135,136,138,139,141,144,149,152,155,156,162,165,173 and 9.5% (N=15) were descriptive cross-sectional.9,22,30,36,39,40,57,64,66,93,100,127,151,169,171 Twenty-one percent of studies (N=33) used qualitative methods,6,21,24,25,29–31,37,43,44,54,55,57,58,62–64,66,68,69,77,80,82,87,88,98,127,142,145,148,154,157,164 among which half (N=17) used mixed methods.29–31,37,43,57,58,64,66,68,77,80,87,127,142,148,157

Huddles were the sole intervention in 42.4% of studies (N=67)6,8,9,11,24–26,28–30,36,38,40,42–47,51,52,54,55,57–60,62,63,65–68,74–78,80–86,88,89,95,104,105,109,110,113,116,117,123,125,127,130,134,136,138,140,144,153,164,169 and part of a larger intervention bundle in 57.6% (N=91).1,21–23,27,31–35,37,39,41,48–50,53,56,61,64,69–73,79,87,90–94,96–103,106–108,111,112,114,115,118–122,124,126,128,129,131–133,135,137,139,141–143,145–152,154–163,165–168,170–173

Huddle Purpose

Studies used huddles for multiple purposes (Table 1). The majority (67.7%) of studies (N=107) described huddles as being used to engage team members in thinking and talking about their work and to improve communication, collaboration, and/or coordination.6,8,11,21–124 Roughly equal numbers of studies described huddles used to identify issues requiring immediate attention or escalation to high-level management for resolution (27.2%; N=43);1,8,9,21,25,27,29,30,32,37,39,44,53,55,57,59,63,69,75,84,87,93,98,116,122,126,134,144,146,149,153–162,165,167,171 update team members about safety and quality issues that affect their work, including reviewing prior issues (24.1%; N=38);6,29,32,40,57,72,73,77,83,87,89,110,111,113,118,122,123,125–139,167–171,173 and plan for or improve processes for future work (22.8%; N=36).9,31,34,50,55,57,59,60,66,69,71,93,100,108,121,122,130,132,134,135,140–151,166,168,170,172 Fewer studies described huddles used to recognize work-related issues that may be addressed by training, coaching, or revising tools and methods (4.4%; N=7)40,57,62,89,112,152,169 or to provide a framework for running Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles (1.3%; N=2).163,164

Theories and Tools

More than one-third of the studies (37.3%; N=59) were based on a conceptual rationale,1,6,11,21,23,27,30–32,35,37,42,47,49,53,54,57,58,61–63,66,67,69,70,73,75,78,83,89,90,94,98,107,115,119–121,123,125–128,132,133,135,145–148,156,159,162–164,166,170,172,173 such as a theory (why the subject of interest will have an impact) and/or a framework or model (how a theory is operationalized).174 Among these studies, the most common were high reliability organizational principles (17.6%; N=9),1,6,63,69,70,123,125,128,135 crew resource management (17.6%; N=9),11,54,61,75,78,89,94,98,121 and Lean Six Sigma (15.7%; N=8).27,30,32,49,115,126,163,170

Only 7.6% of studies (N=12) mentioned organizing their huddles using existing tools or communication scripts (e.g., SBAR; Table 2);8,21,23,65,73,94,101,138,145,146,159,166 15.8% (N=25) developed and published their own huddling tools.27,29,36,42,45,46,49–51,56,60,68,78,80,87,89,96,98,104,112,130,134,136,141,153

Table 2.

Common Tools Used to Communicate in or Monitor Frontline Staff Huddles

| Tool | Description |

|---|---|

| CUS (“I am concerned! I am uncomfortable! This is a safety issue!”)10 | The CUS assertive statements help frontline staff speak up or speak out in uncomfortable situations. A script is presented, using “I am concerned,” “I am uncomfortable,” and “This is a safety issue.” |

| SBAR (Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation)11 | The SBAR technique provides a framework for health care team members to discuss a patient’s condition. “S” is a concise statement of the problem, “B” is pertinent and brief information about the situation, “A” is the team member’s analysis and considerations of options, and “R” is the team member’s request or recommendation. |

| Huddle Observation Tool (HOT)175 | The HOT is a participant/non-participant observation tool that may be used to provide objective measures of (1) huddle effectiveness and (2) changes to huddles, situational awareness, and collaborative culture over time. |

Participating Staff

In studies that identified huddle participants’ job categories (N=120), nurses were involved in 88.3% of the studies (N=106);1,6,8,9,11,21,24–26,28–30,34–46,49–51,53–60,62,63,65,66,68–73,75,77–81,83–89,91,95,96,98–100,103,104,110–114,117,119–123,125,127,129,130,133,136,138,140,142–150,152,153,155,157–160,162,164,165,173 physicians in 75.8% (N=91);6,9,11,24,26,28–30,32,35,36,38–46,49–51,53–59,62,63,65,66,68–73,75,78–81,83–87,91,94–96,98–101,103,104,108–114,117–119,121–123,134,136,140–142,145,146,149,152,153,155,157,158,160,162,164,165,172 members of ancillary services (e.g., social workers; pharmacists; technicians; case managers; respiratory, physical, or occupational therapists) in 50.8% (N=61);11,26,28–30,36–40,45,49,50,54,63,65,66,69–71,75,78,80,81,83–85,89,91,94,96,98–101,103,105,109–112,114,117,118,121,122,125,136,142–144,146,149,152,155,157–160,162,164 managers in 23.3% (N=28);1,6,9,21,25,27,30,32,34,40,44,57,63,69,74,88,89,98,117,123,126,136,143,150,162,164,169,172 and other frontline staff (e.g., clerical staff, environmental services) in 13.3% (N=16).9,30,32,37,55,58,63,68,89,94,98,125,136,162,164,169 Many huddles were interdisciplinary in nature, including participants from more than one job category. More than 24% of all studies (N=38) did not specify participants’ job categories. Three percent (N=5) of all studies explicitly included patients and/or their family members and peer supports.27,30,53,57,125

Nurses, usually charge nurses or nurse managers, facilitated the huddles in 40.0% of studies (N=20)1,28–30,43,44,57,60,85,88,89,112,125,129,130,136,138,147,149,150 where information on facilitator job category was included (N=52).1,9,21,22,28–30,33,35,40,43,44,47,51,54,55,57,59,60,68,69,71,83–85,87–89,98–100,108,111,112,117,123,125,127,129,130,135,136,138,145,147,149,150,162,164,169–171 Other huddle facilitators were attending physicians or medical directors (32.0%; N=16), 9,22,28–30,40,54,55,57,71,84,87,98–100,136 unspecified administrative leaders (26.9%; N=14),9,21,30,33,44,47,57,83,88,123,136,150,169,170 physician trainees (13.5%; N=7),1,35,51,55,100,108,117 unspecified members of the health care team (13.5%; N=7)57,59,68,69,127,145,162 or safety team (7.7%; N=4),47,135,136,171 and pharmacists (6.0%; N=3).111,136,164 In 67.1% (N=106) of all studies, information about huddle leaders was lacking.

Among studies that specified the number of huddle participants (N=31),1,8,31,42,45,53,55,58,62,65,68,71,72,82,87,91,100,104,118,127,138,140,142,144,145,148,153,158,163,165,169 a range of 2 to 20 frontline staff members attended huddles. Nearly 77% of the studies (N=121), however, did not specify the number of participants.

Huddles, when duration was specified, lasted anywhere between 2 and 30 min. Most of these huddles were held either once (41.1%; N=53)6,9,26,27,29,34,35,39,40,42,45,47,51,55,60,62,67–69,73,74,77,80,81,85,87,92,93,102,104,108,111,113,114,116–118,123,126,129,131,138,140,142–144,149,155,160,162,169,170,172 or twice (12.7%; N=20) daily,1,23,28,33,37,43,44,58,59,88–90,120,128,133,145,154,156,157,160 24.7% (N=39) before or after an event of interest (e.g., surgery, fall, activation of sepsis alarm),8,22,24,36,49,53,54,64–66,71,72,78,82–84,91,96,100,105,109,112,119,121,122,130,135–137,141,146,150,152,158,161,165,168,173 and 8.9% (N=14) on a weekly basis or more infrequently.30–32,66,110,127,132,134,147,148,163,164,166,171 Nearly 18% of studies (N=28) did not provide this level of detail when describing the huddles.

Effectiveness of Huddles

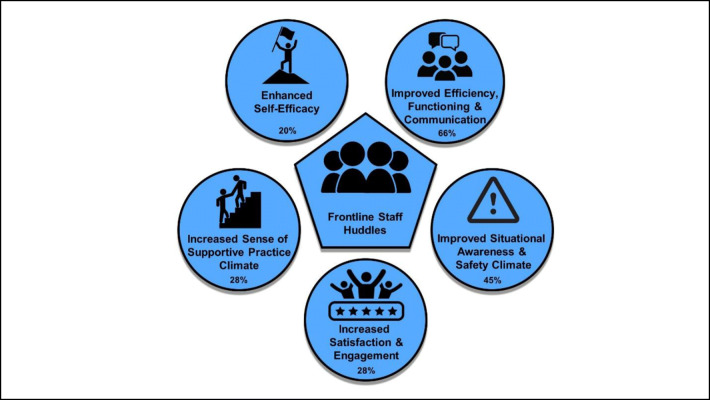

All 9 quantitative studies with a control comparison group reported statistically significant improvements associated with huddles.38,49,87,90,115,121,138,141,162 Of the 123 quantitative studies without a control comparison group, all but 2 reported improvements. Half (N=60) of these studies reported positive findings reaching statistical significance.1,27,29,32,33,35,39,41,45,46,51,52,56,58,61,65,71,72,75,78–81,84,85,91,94,99,101–104,106,109,112,113,116–119,122,125,129,130,134,135,139,142–144,146,148,149,152,155–157,163,165,173 All studies reported at least one outcome, with many reporting multiple process and clinical care outcomes. Of the 63.9% (N=101) studies measuring work and team process outcomes (Table 1), all but 1 reported that the huddle had a statistically significant positive impact on frontline staff.6,8,9,25–99,125–131,140–148,150,153–157 Of these, studies found evidence for improved efficiency, process-based functioning, and communication across clinical roles (64.4%; N=65);6,8,9,25–73,125–127,140–145,153–155 improved situational awareness and staff perceptions of safety and safety climate (44.6%; N=45); 6,8,11,26,30,31,35–37,40,45–47,53,55–57,60,62,63,67–69,71,73–86,128,129,145–147,153,156 increased staff satisfaction and engagement (29.7%; N=30);6,8,11,30,33,37,38,41,47,49,58–60,62,63,68,69,77,79,85,87–89,127,128,130,142,148,156,157 perceptions of a more supportive practice climate (26.7%; N=27); 6,8,9,11,28,30,40,43,47,49,50,57,58,62,66–69,71,79,84,85,90,91,127,154,156 and enhanced self-efficacy among frontline staff to implement evidence-based practices and/or improve care (20.8%; N=21).29,30,34,38,48,51,54,58,66,71,77,81,87,92–95,127,131,148,154 Only 2 qualitative studies (less than 2% of all studies) specifically assessed and reported on unintended negative consequences of the huddling practice, including added pressure on staff time and workload,22 exclusion of clinical trainees, and inadvertent reinforcement of medical hierarchies.24 We summarize the major findings on huddle team process outcomes in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Positive work and team process outcomes associated with frontline huddles (with percent of studies reporting each outcome; N=101). Studies could report more than one outcome; percent totals are over 100.

Seventy studies (44.3%) measured clinical care outcomes1,11,25,27,30,31,34,36,41,49–51,56,63,72,74,86,89,94,97,99–101,104–125,128,130,132–139,141,144,149–152,155,157–164, of which all reported the huddle had a positive clinical impact. Positive clinical care outcomes included the following: increased proportion of patients receiving timely and/or evidence-based assessments or care (31.4%; N=22);27,30,41,51,94,97,99–108,132,133,149,158–160 decreased medical errors and adverse drug events (24.3%; N=17);1,11,25,50,86,109–113,121,128,134–136,161,163 decreased rate of other negative outcomes, e.g., infections, falls, and pressure ulcers (20.0%; N=14);31,89,94,97,119–122,125,130,133,137,150,152 decreased length of hospital stay and improvements to discharge-related measures (15.7%; N=11);30,49,94,114–118,144,157,162 increased patient and family satisfaction (7.1%; N=5);116,117,123,141,149 and decreased costs (2.9%; N=2).116,117

DISCUSSION

We undertook this scoping review to provide a comprehensive overview of huddles used in health care, examine the empirical support for huddle effectiveness, and identify knowledge gaps and opportunities for future studies. Findings from our review show that huddles involving frontline staff are an increasingly prevalent practice across diverse health care settings. Huddles are generally interdisciplinary and aimed at improving team communication, collaboration, and/or coordination. Data from our review point to the effectiveness of huddles at improving work and team process outcomes and indicate the positive impact of huddles can extend beyond processes to include improvements in clinical outcomes.

For a huddle to be clearly distinguished as effective, it must (1) be identifiable as a huddle and (2) be linked to a positive outcome. But identification of a huddle may be difficult. This scoping review included articles that self-identified interventions as huddles or that otherwise described quick, “touch base” meetings of healthcare team members, convened by a designated or situational leader, to enhance or regain situational awareness, discuss critical issues and emerging events, anticipate outcomes and likely contingencies, assign resources, and express concerns.2,7 But study authors’ definitions of huddles varied considerably, owing to heterogeneity of studies’ participants and huddle frequency, duration, and purpose. Some practices were labeled as huddles and therefore included in our review but represent conceptually different practices. Handoffs, meaning predominantly one-way transfers of information,7 stand in contrast to the majority of studies, where huddle information exchange was more collaborative and engaged. Huddle interventions should also ideally be distinguished from rounds, which are typically didactic,176–178 specific to the clinical care and plan for a given patient, and attended primarily by members of that patient’s healthcare team (physicians and nurses). Shift change report, when relevant verbal or written information is passed from one shift of workers (e.g., outgoing nurses) to another (e.g., oncoming nurses) to maintain continuity of care and patient safety,179–181 should also be a distinct category. In addition, some studies did not link targeted objectives to the study intervention, making it impossible to distinguish whether the huddle was related to positive outcomes.23,166–173 These findings point to a need in the literature for improved coherence in studies’ definitions of huddles and tighter links between study huddle interventions and outcomes.

Use of published tools may help promote clarity around the huddling process. The Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE),182 for example, provide guidance on reporting new knowledge about how to improve health care. Another tool is the Huddle Observation Tool,175 a psychometrically sound observational assessment tool that records team processes occurring during a huddle, enables qualitative measures of huddle effectiveness, and facilitates continuous quality improvement of the huddle itself. Systematic use of these tools will promote standardization of the huddling practice; enable greater understanding of local variations in huddling structure, processes, and implementation strategies; and facilitate intra- and inter-study evaluations of huddle effectiveness.

This review also identified a gap in the literature: the lack of conceptual rationales for implementation of huddle-based interventions. This is consistent with other reviews of quality improvement studies in health care183–185 and is despite an extensive menu of relevant theories, models, and frameworks for quality improvement and implementation science. We did not assess whether studies that used an explicit conceptual rationale were of higher quality or were more effective than other studies; however, conceptually grounded interventions are more likely to be widely disseminated.186 Ample resources, e.g., Dissemination & Implementation Models in Health Research & Practice (https://dissemination-implementation.org/), exist to help health care practitioners and researchers select and apply appropriate conceptual approaches for quality improvement. Use of conceptual approaches provides a better sense of how and why an intervention succeeds or fails;174 describes or guides efforts to translate research into practice (i.e., “how-to” process models); and helps evaluate implementation strategies. Greater use of theories, models, and frameworks in future studies on huddles will promote comparison opportunities and, consequently, bring rigor to the growing body of research on the huddling practice.

Many opportunities exist for future research on frontline huddles in healthcare. Researchers should consider experimental study designs comparing a huddle intervention with a control group, as well as quasi-experimental studies assessing the impact of huddles independent of contemporaneous trends or other quality improvement initiatives. This will reduce potential sources of confounding, enhancing the methodological rigor of huddle-based studies. Future research should also specifically evaluate unanticipated consequences associated with the huddling practice, as we only found two studies assessed and reported on negative outcomes. Qualitative research methods, specifically, may enable greater exploration of mechanisms through which huddles may (or may not) impact work and team processes and clinical care outcomes. Finally, implementation studies are needed to facilitate the adoption, scale-up, and maintenance of proven huddle-based interventions in routine healthcare practice.

The potential for reporting (publication) bias represents a limitation of our scoping review. It is possible that practitioners or researchers with positive experiences of or significant findings about huddles submitted more manuscripts for publication and were more successful at being published than those with negative or not significant findings. Heterogeneity of setting, population, study design and methods, and purpose among the large number of studies reviewed also added complexity to our data collection efforts. Nevertheless, it is this same heterogeneity that demonstrates the breadth of clinical settings that have adopted the frontline staff huddling practice and indicates where gaps remain, such as huddle use in non-hospital-based settings (e.g., long-term care) and huddles that incorporate input from non-clinical staff members and patients.

CONCLUSION

A rich and rapidly growing body of empirical research appears to support the use of huddles in diverse clinical contexts for improving work and team processes and the quality of clinical care. This evidence base would greatly benefit from improvements in the conceptualization and design of studies on huddles and an increase in research on theoretically guided huddle-based interventions.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 55 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for Mx. Teddy Bishop’s assistance on the bibliography and for Dr. Daniel Okyere and Ms. Sharon Sloup’s early contributions to this work.

Funding

This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Veterans Health Administration, Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care, through the VA Community Living Centers’ Ongoing National Center for Enhancing Resources and Training. The funding source had no role in the study’s design, conduct, and reporting. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

This work was presented on Jun. 3, 2019, at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting in Washington, DC, and on Oct. 9, 2019, at the American Nurses Credentialing Center National Magnet Conference Research Symposium in Orlando, FL.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Brady PW, Muething S, Kotagal U, et al. Improving situation awareness to reduce unrecognized clinical deterioration and serious safety events. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e298–308. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glymph DC, Olenick M, Barbera S, et al. Healthcare Utilizing Deliberate Discussion Linking Events (HUDDLE): A Systematic Review. Aana j. 2015;83(3):183–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell P, Wynia M, Golden R, et al. Core principles & values of effective team-based health care. 2012. Accessed at Institute of Medicine at http://www.iom.edu/tbc on Dec 10 2018.

- 4.Gittell JH. New directions for relational coordination theory. In: Spreitzer GM, Cameron KS, editors. The Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 400–11. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scoville R, Little K, Rakover J, et al. Sustaining Improvement: IHI White Paper. 2016. Accessed at Institute for Healthcare Improvement at http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/Sustaining-Improvement.aspx on Dec 11 2018.

- 6.Goldenhar LM, Brady PW, Sutcliffe KM, et al. Huddling for high reliability and situation awareness. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(11):899–906. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality. Team STEPPS 2.0. 2006. Accessed at Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality at https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/index.html on Oct 9 2018.

- 8.Martin HA, Ciurzynski SM. Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation-Guided Huddles Improve Communication and Teamwork in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Nurs. 2015;41(6):484–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnelly LF, Cherian SS, Chua KB, et al. The Daily Readiness Huddle: a process to rapidly identify issues and foster improvement through problem-solving accountability. Pediatr Radiol. 2017;47(1):22–30. doi: 10.1007/s00247-016-3712-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. CUS Tool – Improving Communication and Teamwork in the Surgical Environment Module. 2017. Accessed at Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality at http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/hais/tools/ambulatory-surgery/sections/implementation/training-tools/cus-tool.html on Dec 10 2018.

- 11.Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(Suppl 1):i85–90. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan S, Ward M, Vaughan D, et al. Do safety briefings improve patient safety in the acute hospital setting? A systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(10):2085–98. doi: 10.1111/jan.13984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franklin BJ, Gandhi TK, Bates DW, et al. Impact of multidisciplinary team huddles on patient safety: a systematic review and proposed taxonomy. BMJ Qual Saf. Published Online First: 07 April 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ manual: 2017 edition. 2017. Accessed at The Joanna Briggs Institute at https://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/ReviewersManual-2014.pdf on Oct 2 2018.

- 16.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Open Science Framework. 2011. Accessed at https://osf.io on Jan 18 2019.

- 18.Pimentel CB, Hartmann CW, Okyere D, et al. Use of huddles among frontline staff in clinical settings: a scoping review protocol. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(1):146–53. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirchner JE, Parker LE, Bonner LM, et al. Roles of managers, frontline staff and local champions, in implementing quality improvement: stakeholders’ perspectives. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(1):63–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Patient Safety Essentials Toolkit: Huddles. Accessed at http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/Huddles.aspx on May 6 2020.

- 21.Baloh J, Zhu X, Ward MM. Implementing team huddles in small rural hospitals: How does the Kotter model of change apply? J Nurs Manag. 2018;26(5):571–8. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finn DJ, Rajlawat BP, Holt DJ, et al. The development and implementation of a biopsy safety strategy for oral medicine. Br Dent J. 2017;223(9):667–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freitag M, Carroll VS. Handoff communication: using failure modes and effects analysis to improve the transition in care process. Qual Manag Health Care. 2011;20(2):103–9. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0b013e3182136f58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whyte S, Lingard L, Espin S, et al. Paradoxical effects of interprofessional briefings on OR team performance. Cogn Tech Work. 2008;10(4):287–94. [Google Scholar]

- 25.AHC Media LLC. Huddles getting popular, but use them correctly. Healthcare Risk Management; Atlanta. 2014;36(5).

- 26.Ali M, Osborne A, Bethune R, et al. Preoperative Surgical Briefings Do Not Delay Operating Room Start Times and Are Popular With Surgical Team Members. J Patient Saf. 2011;7(3):139–43. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e31822a9fbc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balfour ME, Tanner K, Jurica PJ, et al. Using Lean to Rapidly and Sustainably Transform a Behavioral Health Crisis Program: Impact on Throughput and Safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43(6):275–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berenholtz SM, Schumacher K, Hayanga AJ, et al. Implementing standardized operating room briefings and debriefings at a large regional medical center. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35(8):391–7. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(09)35055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bethune R, Sasirekha G, Sahu A, et al. Use of briefings and debriefings as a tool in improving team work, efficiency, and communication in the operating theatre. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87(1027):331–4. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2009.095802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bourgault AM, Upvall MJ, Graham A. Using Gemba Boards to Facilitate Evidence-Based Practice in Critical Care. Crit Care Nurse. 2018;38(3):e1–e7. doi: 10.4037/ccn2018714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper R. Reducing falls in a care home. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2017;6(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Cromwell S, Chiasson DA, Cassidy D, et al. Improving Autopsy Report Turnaround Times by Implementing Lean Management Principles. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2018;21(1):41–7. doi: 10.1177/1093526617707581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dingley C, Daugherty K, Derieg MK, et al. Advances in Patient Safety Improving Patient Safety Through Provider Communication Strategy Enhancements. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, et al., editors. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol. 3: Performance and Tools) Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Driscoll M, Tobis K, Gurka D, et al. Breaking down the silos to decrease internal diversions and patient flow delays. Nurs Adm Q. 2015;39(1):E1–8. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan A, Baird J, Rogers JE, et al. Parent and Provider Experience and Shared Understanding After a Family-Centered Nighttime Communication Intervention. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(4):389–402. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graham C, Reid S, Lord TC, et al. The evolution of patient safety procedures in an oral surgery department. Br Dent J. 2019;226(1):32–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2019.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris K, Dawson M, Poe T, et al. Nurse communication strategies to improve patient outcomes in a surgical oncology setting. ORL - Head Neck Nurs. 2017;35(4):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henrickson SE, Wadhera RK, Elbardissi AW, et al. Development and pilot evaluation of a preoperative briefing protocol for cardiovascular surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(6):1115–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes Driscoll C, El Metwally D. A daily huddle facilitates patient transports from a neonatal intensive care unit. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2014;3(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Hutcheon RG, Iorlano M, Thomas MK. Clinical status: a daily forum for resident discussion and staff education. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11(9):671–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iwaniszak C, Rees E, Meal R, et al. Improving care of patients with terminal agitation (TA) at end of life at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2018;8:A70. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jain AL, Jones KC, Simon J, et al. The impact of a daily pre-operative surgical huddle on interruptions, delays, and surgeon satisfaction in an orthopedic operating room: a prospective study. Patient Saf Surg. 2015;9:8. doi: 10.1186/s13037-015-0057-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kellish AA, Smith-Miller C, Ashton K, et al. Team Huddle Implementation in a General Pediatric Clinic. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2015;31(6):324–7. doi: 10.1097/NND.0000000000000220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kylor C, Napier T, Rephann A, et al. Implementation of the Safety Huddle. Crit Care Nurse. 2016;36(6):80–2. doi: 10.4037/ccn2016768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lingard L, Regehr G, Orser B, et al. Evaluation of a preoperative checklist and team briefing among surgeons, nurses, and anesthesiologists to reduce failures in communication. Arch Surg. 2008;143(1):12–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2007.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Makary MA, Mukherjee A, Sexton JB, et al. Operating room briefings and wrong-site surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(2):236–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Melton L, Lengerich A, Collins M, et al. Evaluation of Huddles: A Multisite Study. Health Care Manag (Frederick) 2017;36(3):282–7. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0000000000000171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mikan SQ, Wilfong LS, Rhoads M, et al. Improvements in communication and engagement of advance care planning in adults with metastatic cancer through a targeted team approach. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(26_suppl):14. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Molla M, Warren DS, Stewart SL, et al. A Lean Six Sigma Quality Improvement Project Improves Timeliness of Discharge from the Hospital. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018;44(7):401–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neily J, Mills PD, Lee P, et al. Medical team training and coaching in the Veterans Health Administration; assessment and impact on the first 32 facilities in the programme. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(4):360–4. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Newman RE, Bingler MA, Bauer PN, et al. Rates of ICU Transfers After a Scheduled Night-Shift Interprofessional Huddle. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(4):234–42. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nundy S, Mukherjee A, Sexton JB, et al. Impact of preoperative briefings on operating room delays: a preliminary report. Arch Surg. 2008;143(11):1068–72. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.11.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Rourke K, Teel J, Nicholls E, et al. Improving Staff Communication and Transitions of Care Between Obstetric Triage and Labor and Delivery. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2018;47(2):264–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2017.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Papaspyros SC, Javangula KC, Adluri RK, et al. Briefing and debriefing in the cardiac operating room. Analysis of impact on theatre team attitude and patient safety. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010;10(1):43–7. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2009.217356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Picciano A, Winter RO. Benefits of huddle implementation in the family medicine center. Fam Med. 2013;45(7):501–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prager JD, Ruiz AG, Mooney K, et al. Improving operative flow during pediatric airway evaluation: a quality-improvement initiative. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141(3):229–35. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Provost SM, Lanham HJ, Leykum LK, et al. Health care huddles: managing complexity to achieve high reliability. Health Care Manag Rev. 2015;40(1):2–12. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rodriguez HP, Meredith LS, Hamilton AB, et al. Huddle up!: The adoption and use of structured team communication for VA medical home implementation. Health Care Manag Rev. 2015;40(4):286–99. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Setaro J, Connolly M. Safety huddles in the PACU: when a patient self-medicates. J Perianesth Nurs. 2011;26(2):96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shermont H, Mahoney J, Krepcio D, et al. Meeting of the minds. Nurs Manag. 2008;39(8):38–44. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000333723.95980.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shields R, Taub M, Bender J, et al. Board 257 - Program Innovations Abstract Train to Sustain (Submission #1282) Simul Healthc. 2013;8(6):495. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shunk R, Dulay M, Chou CL, et al. Huddle-coaching: a dynamic intervention for trainees and staff to support team-based care. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):244–50. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stapley E, Sharples E, Lachman P, et al. Factors to consider in the introduction of huddles on clinical wards: perceptions of staff on the SAFE programme. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(1):44–9. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzx162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taliani CA, Bricker PL, Adelman AM, et al. Implementing effective care management in the patient-centered medical home. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(12):957–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tibbs SM, Moss J. Promoting teamwork and surgical optimization: combining TeamSTEPPS with a specialty team protocol. AORN J. 2014;100(5):477–88. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2014.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vashdi DR, Bamberger PA, Erez M, et al. Briefing-debriefing: Using a reflexive organizational learning model from the military to enhance the performance of surgical teams. Hum Resour Manag. 2007;46(1):115–42. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Venkataraman A, Conn R, Cotton RL, et al. 117 Enhancing situational awareness through safety huddles – a staff perspective. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102(Suppl 3):A31-A. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Walsh A, Moore A, Everson J, et al. Gathering, strategizing, motivating and celebrating: the team huddle in a teaching general practice. Educ Prim Care. 2018;29(2):94–9. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2018.1423642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weaver RR. Seeking high reliability in primary care: Leadership, tools, and organization. Health Care Manag Rev. 2015;40(3):183–92. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Williams JP, Spernaes I, Duff E, et al. Development and implementation of a theatre booking form and morning briefing meeting to improve emergency theatre efficiency. J Perioper Pract. 2017;27(10):217–23. doi: 10.1177/175045891702701003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wolf FA, Way LW, Stewart L. The efficacy of medical team training: improved team performance and decreased operating room delays: a detailed analysis of 4863 cases. Ann Surg. 2010;252(3):477–83. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f1c091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wood J, Stevenson E. Using Hourly Time-Outs and a Standardized Tool to Promote Team Communication, Medical Record Documentation, and Patient Satisfaction During Second-Stage Labor. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2018;43(4):195–200. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wright JG, Roche A, Khoury AE. Improving on-time surgical starts in an operating room. Can J Surg. 2010;53(3):167–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.AHC Media LLC. Safety huddles produce results if they are controlled and monitored. Healthc Risk Manag. 2016;38(10).

- 75.Allard J, Bleakley A, Hobbs A, et al. Pre-surgery briefings and safety climate in the operating theatre. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(8):711–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.032672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carpenter JE, Bagian JP, Snider RG, et al. Medical Team Training Improves Team Performance: AOA Critical Issues. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(18):1604–10. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.01290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chiafery MC, Hopkins P, Norton SA, et al. Nursing Ethics Huddles to Decrease Moral Distress among Nurses in the Intensive Care Unit. J Clin Ethics. 2018;29(3):217–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gore DC, Powell JM, Baer JG, et al. Crew resource management improved perception of patient safety in the operating room. Am J Med Qual. 2010;25(1):60–3. doi: 10.1177/1062860609351236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hill MR, Roberts MJ, Alderson ML, et al. Safety culture and the 5 steps to safer surgery: an intervention study. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(6):958–62. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Khoshbin A, Lingard L, Wright JG. Evaluation of preoperative and perioperative operating room briefings at the Hospital for Sick Children. Can J Surg. 2009;52(4):309–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Leong K, Hanskamp-Sebregts M, van der Wal RA, et al. Effects of perioperative briefing and debriefing on patient safety: a prospective intervention study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e018367. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lingard L, Whyte S, Espin S, et al. Towards safer interprofessional communication: constructing a model of “utility” from preoperative team briefings. J Interprof Care. 2006;20(5):471–83. doi: 10.1080/13561820600921865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Motuel L, Dodds S, Jones S, et al. Swarm: a quick and efficient response to patient safety incidents. Nurs Times. 2017;113(9):36–8. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Paige JT, Aaron DL, Yang T, et al. Improved operating room teamwork via SAFETY prep: a rural community hospital’s experience. World J Surg. 2009;33(6):1181–7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-9952-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Townsend CS, McNulty M, Grillo-Peck A. Implementing Huddles Improves Care Coordination in an Academic Health Center. Prof Case Manag. 2017;22(1):29–35. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0000000000000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wright MA. KP Northwest Preoperative Briefing Project. Perm J. 2005;9(2):35–9. doi: 10.7812/tpp/04-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bennett NL, Flesch JD, Cronholm P, et al. Bringing Rounds Back to the Patient: A One-Year Evaluation of the Chiefs’ Service Model for Inpatient Teaching. Acad Med. 2017;92(4):528–36. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hyde P. Implementing the “Cardiac Huddle”. Crit Care Nurse. 2008;28(2):144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lubinensky M, Kratzer R, Bergstol J. Huddle up for patient safety. Am Nurse Today 2015;10.

- 90.Ginsburg L, Bain L. The evaluation of a multifaceted intervention to promote “speaking up” and strengthen interprofessional teamwork climate perceptions. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(2):207–17. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2016.1249280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Paige JT, Aaron DL, Yang T, et al. Implementation of a preoperative briefing protocol improves accuracy of teamwork assessment in the operating room. Am Surg. 2008;74(9):817–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Corrado J, Topley K, Cracknell A. Improving the efficacy of elderly patients’ hospital discharge through multi-professional safety briefings and behavioural change. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2015;4(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 93.Gale RC, Asch SM, Taylor T, et al. The most used and most helpful facilitators for patient-centered medical home implementation. Implement Sci. 2015;10:52. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0246-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Stansfield T, Parker R, Masson N, et al. The Endovascular Preprocedural Run Through and Brief: A Simple Intervention to Reduce Radiation Dose and Contrast Load in Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016;50(4):241–6. doi: 10.1177/1538574416644527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Thanapongsathorn W, Jitsopa J, Wongviriyakorn O. Interprofessional preoperative briefing enhances surgical teamwork satisfaction and decrease operative time: a comparative study in abdominal operation. J Med Assoc Thail. 2012;95(Suppl 12):S8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bennett SC, Finer N, Halamek LP, et al. Implementing Delivery Room Checklists and Communication Standards in a Multi-Neonatal ICU Quality Improvement Collaborative. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2016;42(8):369–76. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(16)42052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kazana I, Pencak MM. Implementing a patient-centered walking program for residents in long-term care: A quality improvement project. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2018;30(7):383–91. doi: 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Marshall DA, Manus DA. A team training program using human factors to enhance patient safety. AORN J. 2007;86(6):994–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2007.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shaughnessy EE, White C, Shah SS, et al. Implementation of Postoperative Respiratory Care for Pediatric Orthopedic Patients. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):e505–12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ansryan LZ, Aronow HU, Borenstein JE, et al. Systems Addressing Frail Elder Care: Description of a Successful Model. J Nurs Adm. 2018;48(1):11–7. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Girdwood ST, Sellas M, Courter J, et al. Improving timely transition of parenteral to enteral antibiotics in paediatric patients with pneumonia and cellulitis using quality improvement methods. BMJ Open Qual. 2017;6:A18–A9. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gordon R, Ashley A, Banerjee T, et al. IHI ID 19 Improving family-care team communication during routine CF clinic visits. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(Suppl 1):A24–A7. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lingard L, Regehr G, Cartmill C, et al. Evaluation of a preoperative team briefing: a new communication routine results in improved clinical practice. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(6):475–82. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.032326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.McBeth CL, Durbin-Johnson B, Siegel EO. Interprofessional Huddle: One Children’s Hospital’s Approach to Improving Patient Flow. Pediatr Nurs. 2017;43(2):71–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mott A, Kafka S, Sutherland A. Assessing pharmaceutical care needs of paediatric in-patients: A team based approach. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101(9):e2. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311535.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Parthiban A, Warta A, Marshall JA, et al. Improving Wait Time for Patients in a Pediatric Echocardiography Laboratory - a Quality Improvement Project. Pediatr Qual Saf. 2018;3(3):e083. doi: 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Price T. Abstract TP405: Raising the bar, lowering the target. International Stroke Conference, 2016. ATP405.

- 108.Shivananda S, Gupta S, Thomas S, et al. Impact of a dedicated neonatal stabilization room and process changes on stabilization time. J Perinatol. 2017;37(2):162–7. doi: 10.1038/jp.2016.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Beardsley JR, Schomberg RH, Heatherly SJ, et al. Implementation of a Standardized Discharge Time-out Process to Reduce Prescribing Errors at Discharge. Hosp Pharm. 2013;48(1):39–47. doi: 10.1310/hpj4801-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bell C, Jackson J, Shore H. P3 S.a.f.e. – the positive impact of ‘druggles’ on prescribing standards and patient safety within the neonatal intensive care environment. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(2):e2. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bhavee P, Rachel I, Pramodh V. P28 Reducing medication errors – a tripartite approach. small steps – better outcomes. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(2):e1. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Keiffer S, Marcum G, Harrison S, et al. Reduction of medication errors in a pediatric cardiothoracic intensive care unit. J Nurs Care Qual. 2015;30(3):212–9. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Phadnis J, Templeton-Ward O. Inadequate Preoperative Team Briefings Lead to More Intraoperative Adverse Events. J Patient Saf. 2018;14(2):82–6. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.AHC Media LLC Team huddles improve LOS, core measures. Hosp Case Manag. 2013;21(2):23–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Beck MJ, Okerblom D, Kumar A, et al. Lean intervention improves patient discharge times, improves emergency department throughput and reduces congestion. Hosp Pract. 2016;44(5):252–9. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2016.1254559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chan A, Vadera S. 110 Neurosurgery Morning Huddle Reduces Costs and Increases Patient Satisfaction. Neurosurgery. 2017;64(CN_suppl_1):222–3. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chan AY, Vadera S. Implementation of interdisciplinary neurosurgery morning huddle: cost-effectiveness and increased patient satisfaction. J Neurosurg. 2018;128(1):258–61. doi: 10.3171/2016.11.JNS162328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Patel H, Morduchowicz S, Mourad M. Using a Systematic Framework of Interventions to Improve Early Discharges. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43(4):189–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gams B, Neerland C, Kennedy S. Reducing Primary Cesareans: An Innovative Multipronged Approach to Supporting Physiologic Labor and Vaginal Birth. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2019;33(1):52–60. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Leone RM, Adams RJ. Safety Standards: Implementing Fall Prevention Interventions and Sustaining Lower Fall Rates by Promoting the Culture of Safety on an Inpatient Rehabilitation Unit. Rehabil Nurs. 2016;41(1):26–32. doi: 10.1002/rnj.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Neily J, Mills PD, Young-Xu Y, et al. Association between implementation of a medical team training program and surgical mortality. JAMA. 2010;304(15):1693–700. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zubkoff L, Neily J, Quigley P, et al. Preventing Falls and Fall-Related Injuries in State Veterans Homes: Virtual Breakthrough Series Collaborative. J Nurs Care Qual. 2018;33(4):334–40. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Brass SD, Olney G, Glimp R, et al. Using the Patient Safety Huddle as a Tool for High Reliability. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018;44(4):219–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Storey J, Mustin L, Madsen N, et al. Improving the transfer of medically complex patients from the cardiac intensive care unit to the cardiology inpatient ward. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(11):737–8. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Reiter-Palmon R, Kennel V, Allen JA, et al. Naturalistic Decision Making in After-Action Review Meetings: The Implementation of and Learning from Post-Fall Huddles. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2015;88(2):322–40. doi: 10.1111/joop.12084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Thompson H, Vago T, Bell AM. Labor and Birth Improvements at Mercy Hospital St. Louis. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2015;44(s1):S14-S. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wagner LM, Huijbregts M, Sokoloff LG, et al. Implementation of Mental Health Huddles on Dementia Care Units. Can J Aging. 2014;33(3):235–45. doi: 10.1017/S0714980814000166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Cropper DP, Harb NH, Said PA, et al. Implementation of a patient safety program at a tertiary health system: A longitudinal analysis of interventions and serious safety events. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2018;37(4):17–24. doi: 10.1002/jhrm.21319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Fridman V. The Effectiveness of Nurse-Driven Early Mobility Protocol. Seton Hall University DNP Final Projects. 2017;22.

- 130.Hansell K, Kirby EM. Team Engagement and Improvement Through Huddles. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2015;44(s1):S46–S7. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hebert J. Improving hand hygiene through a multimodal approach. Nurs Manag. 2015;46(11):27–30. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000472766.11354.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Simmons SF, Coelho CS, Sandler A, et al. A System for Managing Staff and Quality of Dementia Care in Assisted Living Facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(8):1632–7. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Sykes L, Sinha S, Hegarty J, et al. Reducing acute kidney injury incidence and progression in a large teaching hospital. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(4):e000308. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2017-000308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Guo M, Tardif G, Bayley M. Medical Safety Huddles in Rehabilitation: A Novel Patient Safety Strategy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(6):1217–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.09.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.McClead RE, Jr, Catt C, Davis JT, et al. An internal quality improvement collaborative significantly reduces hospital-wide medication error related adverse drug events. J Pediatr. 2014;165(6):1222–9.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Morvay S, Lewe D, Stewart B, et al. Medication event huddles: a tool for reducing adverse drug events. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2014;40(1):39–45. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(14)40005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Fetzer M, Humphrey R, Stack-Simone S, et al. Pediatric catheter associated urinary tract infection reduction – an achievable goal. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(11):733–4. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Dewan M, Wolfe H, Lin R, et al. Impact of a Safety Huddle-Based Intervention on Monitor Alarm Rates in Low-Acuity Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Patients. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(8):652–7. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Zubkoff L, Neily J, Quigley P, et al. Virtual Breakthrough Series, Part 2: Improving Fall Prevention Practices in the Veterans Health Administration. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2016;42(11):497–ap12. doi: 10.1016/S1553-7250(16)42092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Cummings B, Kelleher A, Mansoor Z, et al. 127: Reduce pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) rounds inefficiency through a preround huddle. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(12):A25. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Monash B, Najafi N, Mourad M, et al. Standardized Attending Rounds to Improve the Patient Experience: A Pragmatic Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):143–9. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Nagelkerk J, Thompson ME, Bouthillier M, et al. Improving outcomes in adults with diabetes through an interprofessional collaborative practice program. J Interprofessional Care [DOI] [PubMed]

- 143.Resar R, Nolan K, Kaczynski D, et al. Using real-time demand capacity management to improve hospitalwide patient flow. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37(5):217–27. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Tielbur BR, Rice Cella DE, Currie A, et al. Discharge huddle outfitted with mobile technology improves efficiency of transitioning stroke patients into follow-up care. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(1):36–44. doi: 10.1177/1062860613510964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Turner P. Implementation of TeamSTEPPS in the emergency department. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2012;35(3):208–12. doi: 10.1097/CNQ.0b013e3182542c6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Lisbon D, Allin D, Cleek C, et al. Improved Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors After Implementation of TeamSTEPPS Training in an Academic Emergency Department: A Pilot Report. Am J Med Qual. 2016;31(1):86–90. doi: 10.1177/1062860614545123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.O’Connor T. Implementation of a pediatric behavioral staffing algorithm in an acute hospital: a best practice implementation project. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017;15(11):2799–814. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Taylor J, Barker A, Hill H, et al. Improving person-centered mobility care in nursing homes: a feasibility study. Geriatr Nurs. 2015;36(2):98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Biernacki PJ, Champagne MT, Peng S, et al. Transformation of Care: Integrating the Registered Nurse Care Coordinator into the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Popul Health Manag. 2015;18(5):330–6. doi: 10.1089/pop.2014.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Howard K, Huster J, Hlodash G, et al. Improving fall rates using bedside debriefings and reflective emails: One unit’s success story. Medsurg Nurs. 2018;27(6):388–91. [Google Scholar]

- 151.Shapiro J, Venkata A, Ochieng P, et al. 573: The Emergency Department to ICU Quality and Safety Project: Formal Handoff/Huddle to Improve Care. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(12):A140. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Shepherd EG, Kelly TJ, Vinsel JA, et al. Significant Reduction of Central-Line Associated Bloodstream Infections in a Network of Diverse Neonatal Nurseries. J Pediatr. 2015;167(1):41–6.e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Mullan PC, Macias CG, Hsu D, et al. A novel briefing checklist at shift handoff in an emergency department improves situational awareness and safety event identification. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(4):231–8. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Pannick S, Archer S, Johnston MJ, et al. Translating concerns into action: a detailed qualitative evaluation of an interdisciplinary intervention on medical wards. BMJ Open. 2017;7(4):e014401. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Sharma G, Wong D, Arnaoutakis DJ, et al. Systematic identification and management of barriers to vascular surgery patient discharge time of day. J Vasc Surg. 2017;65(1):172–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.07.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Blumenthal E, Carranza L, Sim MS. Improving Safety on Labor and Delivery Through Team Huddles and Teamwork Training [25H] Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:72S–3S. [Google Scholar]

- 157.Hastings SE, Suter E, Bloom J, et al. Introduction of a team-based care model in a general medical unit. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:245. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1507-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Dandoy CE, Hariharan S, Weiss B, et al. Sustained reductions in time to antibiotic delivery in febrile immunocompromised children: results of a quality improvement collaborative. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(2):100–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Pisegna L, Pyka J. An Interdisciplinary Approach to Improving Exclusive Breast Milk Feeding Rate at Discharge. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43:S61–S2. [Google Scholar]

- 160.Weintraub B, Jensen K, Colby K. Improving hospitalwide patient flow at Northwest Community Hospital. Managing Patient Flow in Hospitals: Strategies and Solution, 2nd ed. Oak Brook: Joint Commission Resources. 2010:129-51.

- 161.AHC Media LLC. Two-stage screening tool improves identification of young sepsis patients in ED. ED Manag. 2017;29(12).

- 162.Pannick S, Athanasiou T, Long SJ, et al. Translating staff experience into organisational improvement: the HEADS-UP stepped wedge, cluster controlled, non-randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e014333. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.van der Sluijs AF, van Slobbe-Bijlsma ER, Goossens A, et al. Reducing errors in the administration of medication with infusion pumps in the intensive care department: A lean approach. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312118822629. doi: 10.1177/2050312118822629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Wells T, Rockafellow S, Holler M, et al. Description of pharmacist-led quality improvement huddles in the patient-centered medical home model. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2018;58(6):667–72.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Balamuth F, Alpern ER, Abbadessa MK, et al. Improving Recognition of Pediatric Severe Sepsis in the Emergency Department: Contributions of a Vital Sign-Based Electronic Alert and Bedside Clinician Identification. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(6):759–68.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Cruz LC, Fine JS, Nori S. Barriers to discharge from inpatient rehabilitation: a teamwork approach. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2017;30(2):137–47. doi: 10.1108/IJHCQA-07-2016-0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Hodges KT, Gilbert JH. Rising above risk: Eliminating infant falls. Nurs Manag. 2015;46(12):28–32. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000473504.41357.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Hoke LM, Guarracino D. Beyond Socks, Signs, and Alarms: A Reflective Accountability Model for Fall Prevention. Am J Nurs. 2016;116(1):42–7. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000476167.43671.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Menon S, Singh H, Giardina TD, et al. Safety huddles to proactively identify and address electronic health record safety. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(2):261–7. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Phillips J, Hebish LJ, Mann S, et al. Engaging Frontline Leaders and Staff in Real-Time Improvement. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2016;42(4):170–83. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(16)42021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Plouffe JA. Spacelabs Innovative Project Award winner--2007. Solar system of safety. Dynamics. 2010;21(3):20–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Ryckman FC, Yelton PA, Anneken AM, et al. Redesigning intensive care unit flow using variability management to improve access and safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35(11):535–43. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(09)35073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Tetuan T, Ohm R, Kinzie L, et al. Does Systems Thinking Improve the Perception of Safety Culture and Patient Safety? J Nurs Regul. 2017;8(2):31–9. [Google Scholar]