Abstract

The relationship between the dimensions of pressure-unfolded states of proteins compared with those at ambient pressure is controversial; resolving this issue is related directly to the mechanisms of pressure denaturation. Moreover, a significant pressure dependence of the compactness of unfolded states would complicate the interpretation of folding parameters from pressure perturbation and make comparison to those obtained using alternative perturbation approaches difficult. Here, we determined the compactness of the pressure-unfolded state of a small, cooperatively folding model protein, CTL9-I98A, as a function of temperature. This protein undergoes both thermal unfolding and cold denaturation, and the temperature dependence of the compactness at atmospheric pressure is known. High-pressure small angle x-ray scattering studies, yielding the radius of gyration and high-pressure diffusion ordered spectroscopy NMR experiments, yielding the hydrodynamic radius were carried out as a function of temperature at 250 MPa, a pressure at which the protein is unfolded. The radius of gyration values obtained at any given temperature at 250 MPa were similar to those reported previously at ambient pressure, and the trends with temperature are similar as well, although the pressure-unfolded state appears to undergo more pronounced expansion at high temperature than the unfolded state at atmospheric pressure. At 250 MPa, the compaction of the unfolded chain was maximal between 25 and 30°C, and the chain expanded upon both cooling and heating. These results reveal that the pressure-unfolded state of this protein is very similar to that observed at ambient pressure, demonstrating that pressure perturbation represents a powerful approach for observing the unfolded states of proteins under otherwise near-native conditions.

Significance

A complete understanding of protein un/folding requires knowledge of the characteristics of both the reactant (folded state) and the product (unfolded state) of the unfolding reaction. Contrary to prior conclusions based on theoretical and experimental studies, we demonstrate using high-pressure small angle x-ray scattering and NMR diffusion ordered spectroscopy that the unfolded state of a protein at high pressure and across a broad range of temperatures is not more compact than its unfolded state at ambient pressure. Our results demonstrate that the mechanism of pressure-induced unfolding is not to push water inside the protein, but rather to stabilize an extended state that has lost the internal voids of the folded state.

Introduction

High hydrostatic pressure is increasingly used to explore protein conformational landscapes and dynamics (1, 2, 3). It has been useful in increasing the population of low-lying excited states (4, 5, 6) as well as for characterizing unfolding pathways (7,8). Pressure perturbation offers a complementary approach to other perturbation methods, yielding unique insights into the volumetric properties of protein conformational ensembles. Although energetically equivalent to unfolded states obtained using chemical denaturants or temperature, in cases in which they have been compared (e.g., (9)), pressure-unfolded states have long been thought to be more compact than those obtained using alternative perturbations. Understanding the nature of the pressure-induced unfolded state is important given that pressure offers an alternative to populating the unfolded state in the absence of high denaturant or at extremes of temperature or pH. The nature of the unfolded state at high pressure is still controversial; some studies demonstrate an equivalence with other unfolded states, whereas other studies reach the opposite conclusion. Resolving this apparent contradiction is important as it relates to the mechanism of pressure-induced unfolding and impacts the comparison of unfolding by pressure and other perturbations.

There are conflicting reports on the nature of the pressure-unfolded state. We have previously noted that the fully unfolded state of staphylococcal nuclease populated under pressure is energetically and structurally indistinguishable from that observed in chemical denaturation studies, as evidenced by fluorescence, small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, and multidimensional NMR (9,10). Other examples of equivalence are provided by a high-pressure study of T4 lysozyme (11) and a recent high pressure NMR DOSY study of ubiquitin, which revealed that the radius of gyration (Rg) and hydrodynamic radius (Rh) of the pressure-unfolded states, respectively, were like staphylococcal nuclease, close to values expected for a random coil in good solvent (12). A hydrogen/deuterium exchange study under pressure showed that the energetic hierarchy of subdomain unfolding in apocytochrome b562 was equivalent in chemical and pressure denaturation (13). However, differences between apparent pressure unfolded as opposed to temperature or denaturant unfolded proteins have been reported (e.g., (14)). Theoretical (15,16) and experimental (17, 18, 19) studies have suggested that pressure denatures proteins by pushing water molecules into internal cavities, resulting in an overall decrease in molar volume. This has led to the notion in the field of pressure denaturation that the pressure-unfolded state is less “unfolded” than unfolded states induced by other perturbations and corresponds to a somewhat expanded, water-containing globular structure. In support of the above-mentioned mechanism, we note that intermediates in protein folding have been reported in which it has been proposed that cavities are hydrated (e.g., (19,20)) under pressure, although the semantic distinction remains subtle between disruption of structure and chain hydration versus filling of cavities by water in such intermediates. Water-filled cavities have been observed under conditions (crystal (17) or confinement in reverse micelles (21)) in which unfolding transitions are suppressed.

The notion that pressure-unfolded states are more compact than those observed at high temperature or denaturant concentration arose as well from the fact that pressure can lead to unfolding of certain regions of proteins, leaving the others folded. As pointed out by Silva and Weber many years ago, “The conformation appearing at the higher pressures is commonly designated as ‘pressure denatured,’ although knowledge of its properties are still too meager to decide on its relation to protein denatured by heat or by addition of chemicals such as urea or guanidine” (22). As more residue-specific NMR-based high pressure unfolding studies have appeared, it has become clear that the ensembles observed at high pressure can correspond to folding intermediates rather than completely unfolded states. In these intermediates, certain regions of the protein are unfolded, whereas others remain in their native conformation (e.g., (4,5,23,24)). Such intermediates are observed more frequently in pressure denaturation studies than in chemical or temperature denaturation studies because the internal voids that are primarily responsible for pressure destabilization (10,11) are heterogeneously distributed throughout the protein’s structure. Hence, pressure effects are often more local than temperature denaturation, tending to differentially destabilize protein domains and subdomains beyond their underlying energetic differences. These pressure-induced intermediate states appear to be globally more compact compared with fully unfolded states because some parts of the protein retain their native structures (5,25). They have sometimes been mistaken (depending upon the observables) as corresponding to the fully unfolded state at high pressure. We note that electrostriction of ionizable residues that are exposed to solvent upon unfolding can also contribute significantly to the magnitude of volume changes of unfolding (see Fig. 5 in (26)). However, internal unsolvated ionizable residues are relatively rare, and in this case, CTL9 has none.

Förster resonance energy transfer measurements and SAXS studies have suggested that protein unfolded states at ambient pressure expand with decreasing temperature (27, 28, 30). For example, low temperature expansion at atmospheric pressure of the unfolded state has been observed by SAXS and NMR diffusion measurements (DOSY) for the destabilized I98A variant of the C-terminal domain of the ribosomal protein L9 (CTL9) (31,32), which undergoes cooperative thermal unfolding and cold denaturation at nonfreezing temperatures (Fig. 1; (32,34)). Unfolded states also appear to expand when heated; however, the magnitude of the effect appears to be less than observed for cooling (29, 30, 31). Thus, the temperature dependence of the dimensions of the unfolded states, as defined by the radius of gyration (Rg), is not monotonic. This complex behavior likely results from a convolution of the temperature dependence of the hydrophobic effect and the temperature dependence of solvation of polar and charged residues (29).

Figure 1.

Ribbon representation of the CTL9-I98A protein. The position of residue 98 is shown in the backbone in red. The central cavity, enlarged because of the mutation, was calculated using Hollow (33) and is shown in purple spheres.

The degree of structural equivalence between pressure-unfolded states and unfolded states under native conditions at ambient pressure remains unclear. In part, this stems from the difficulty of characterizing unfolded states under native conditions. CTL9-I98A provides an excellent experimental system to address this issue. CTL9 is a single domain mixed α−β-protein, which folds cooperatively at atmospheric pressure in an apparent two-state fashion through a compact folding transition state (31,35, 36, 37). The I98A mutation destabilizes the domain so that both cold denaturation and thermal denaturation is observed at experimentally accessible temperatures, and the temperature of maximal stability is near 30°C (28,31,32,34). The native state of the mutant adopts the same fold as wild-type and is a compact cooperatively folded structure, rather than a molten globule or other partially folded state. The cold unfolding transition of CTL9-I98A appears to be cooperative at atmospheric pressure as judged by studies employing multiple spectroscopic probes to follow the cold unfolding (34). Based on our prior investigations of the temperature dependence of the NMR-detected, pressure-induced unfolding of CTL9-I98A (35) as well as the compaction of its unfolded state as a function of temperature under native conditions (31,32), this protein was chosen to examine the temperature dependence of compaction at high pressure. The I98A mutation in CTL9 creates a large cavity in the hydrophobic core of the protein, destabilizing the native state and rendering this variant more sensitive to pressure (lower stability and larger change in volume) than the wild-type. Previous high pressure) NMR studies revealed that, at pressures above 200 MPa, the native structure of the protein is disrupted uniformly across the entire chain (38). However, these high pressure NMR results provided no information about the degree of compaction of the pressure-denatured state, nor did they reveal how it might be influenced by temperature. To test the similarity of the pressure-unfolded state of CTL9-I98A compared with its ambient pressure counterpart, we carried out high pressure SAXS and NMR diffusion measurements from 5 to 50°C at 250 MPa (where the unfolded state is overwhelmingly predominant (38)) and compared the results to prior characterization of the unfolded state of the same protein at atmospheric pressure (5).

Materials and methods

Protein purification

CTL9-I98A was produced and purified as previously described (31). Samples for both high-pressure SAXS and high-pressure NMR were prepared in 10 mM MOPS buffer at pH 8 with 150 mM NaCl. MOPS exhibits a low temperature and pressure coefficient for its pKa.

HP SAXS

High pressure SAXS data were collected at the BioSAXS beamline of the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source, using a recently modified high pressure SAXS cell (39). Samples contained 15 mg/mL CTL9-I98A protein in 10 mM MOPS buffer at pH 8 with 150 mM NaCl. Data were collected at a constant pressure of 250 MPa and temperatures 5–50°C. Rg was calculated from the data using Guinier analysis in the software RAW (40), and the q-values at each temperature were adjusted within the Guinier range (<1.3) to obtain random residuals. In the P(r) analyses using GNOM (41), the qmax was cutoff at 0.2 to reduce noise. Dmax-values were chosen to minimize the χ2 and yield reasonable descent to the r axis. GNOM also returns an automatically calculated Rg from Guinier analysis, which was nearly identical to those obtained by user input.

HP DOSY NMR

DOSY NMR experiments were carried out at high pressure with dioxane as an internal standard as previously described (42). Samples contained 4 mg/mL CTL9-I98A protein in 10 mM MOPS buffer with 150 mM NaCl in 100% D2O (pD 8). Data were collected at a constant pressure of 250 MPa and temperatures 5–50°C. The standard stebpgp1s19 pulse sequence was used, the pulsed field gradient duration was 6.4 ms, the diffusion period was 100 ms, and the variable gradient strength was 34.05 T/cm. For the gradient, 32 scans were collected for each of 64 linear incremental steps from 2 to 95% of the gradient strength, with a recycle delay of 5 s. Data were analyzed within the “T1/T2 relaxation” module in Bruker’s Topspin software.

RESULTS

To compare the compactness of the pressure-unfolded state of CTL9-I98A to the unfolded state observed at atmospheric pressure, we turned to high pressure SAXS using a recently modified high pressure SAXS cell (39). SAXS profiles of CTL9-I98A at atmospheric pressure at the high concentrations (15 mg/mL) required for high pressure SAXS revealed aggregation of the protein. However, Guinier analysis (Fig. 2 A; Fig. S1) of the SAXS profile of CTL9-I98A at 250 MPa and 5°C revealed that, as expected, the aggregates were disrupted by pressure. This highlights another advantage of high pressure studies, namely that aggregation is often less of an issue. The Rg obtained from Guinier analysis at 5°C and 250 MPa was found to be 27.9 ± 0.8 Å, in good agreement with the Rg-value (27.3 ± 0.7 Å) previously determined for the unfolded state of CTL9-I98A at 5°C and atmospheric pressure (31). This value is slightly smaller than the Rg measured for the same protein at 25°C and 6 M guanidinium hydrochloride (29 Å, which is consistent with a random coil polymer in good solvent) but is much larger than the Rg-value of the folded state at atmospheric pressure observed between 5 and 50°C (15.0 ± 0.2 Å) (31).

Figure 2.

High-pressure SAXS for CTL9-I98A. (A) Guinier plot at 5°C, (B) Rg from P(r) analysis versus temperature, and (C) Rg from Guinier analysis versus temperature. Error bars represent standard deviation calculated from the uncertainty of the fits of the Guinier and P(r) data.

Upon heating CTL9-I98A from 5 to 50°C at 250 MPa, the Rg-value obtained from both Guinier (Fig. S1) and pair distribution (P(r)) analysis (Fig. 3) decreased to between 25 and 26 Å at 20–25°C and then increased somewhat with further heating (Fig. 2, B and C; Table 1). The trend at low temperatures is consistent with our previously reported expansion of the unfolded chain at low temperatures at atmospheric pressure (31,32). These results suggest an expansion at high temperature and high pressure as well, although it is less pronounced than that observed at low temperature and high pressure. The actual values of the Rg for the unfolded state at high pressure, regardless of whether they were obtained by Guinier or pair distribution analysis, are somewhat larger than those obtained for the unfolded state at atmospheric pressure (Table 1). This may result from slightly greater disruption of residual structure at high pressure. Alternatively, the uncertainty associated with the deconvolution procedure used at atmospheric pressure (31) to disentangle the contribution from the folded population could account for at least some of the difference.

Figure 3.

Pair distribution analysis of high-pressure SAXS for CTL9-I98A. (A) 5°C, (B) 25°C, and (C) 50°C. Top is P(r) plot, middle is I(q) data (blue dots) and fit (red line), and bottom is residuals from the fit.

Table 1.

Comparison of Rg-values for CTL9-I98A unfolded state at 0.1 and 250 MPa

| Temperature (°C) | Rg unfolded state at 0.1 MPa (Å) (31) | Rg unfolded state at 250 MPa (Guinier) (Å) | Rg unfolded state at 250 MPa (P(r)) (Å) | Rg unfolded state at 0.1 MPa and 6 M GuHCl (31) (Å) (26) | Rh unfolded state at 250 MPa (Å) | Rh unfolded state at 0.1 MPa (pH 6.6) (Å) DOSY (42) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 27.3 ± 1.7 | 27.9 ± 0.8 | 28.5 ± 0.4 | 28.9 ± 1.3 | 25.8 ± 0.5 | 23.1 (4°C) |

| 10 | 25.0 ± 1.5 | 26.9 ± 0.9 | 27.2 ± 0.5 | – | 24.5 ± 0.2 | 21.7 (12°C) |

| 15 | 24.3 ± 1.4 | 25.6 ± 0.9 | 27.4 ± 0.7 | – | 24.0 ± 0.2 | – |

| 20 | 23.0 ± 1.0 | 25.0 ± 0.6 | 26.9 ± 0.3 | – | 23.7 ± 0.2 | – |

| 25 | 22.8 ± 1.0 | 25.2 ± 0.7 | 26.1 ± 0.2 | – | 22.9 ± 0.3 | – |

| 30 | 21.9 ± 0.9 | 25.9 ± 0.7 | 26.1 ± 0.4 | 30 ± 0.9 | 22.8 ± 0.3 | – |

| 35 | 21.9 ± 0.8 | 26.4 ± 0.6 | 27.1 ± 0.4 | – | 24.0 ± 0.3 | – |

| 40 | 22.4 ± 1.0 | 26.0 ± 0.6 | 26.8 ± 0.4 | – | 25.2 ± 0.5 | – |

| 45 | 22.5 ± 0.9 | 25.1 ± 0.6 | 26.3 ± 0.5 | – | 25.4 ± 0.4 | – |

| 50 | 21.2 ± 1.1 | 26.9 ± 0.7 | 26.8 ± 0.4 | 29.9 ± 1.1 (55°C) | 25.3 ± 0.5 | – |

Uncertainties represent apparent SDs.

P(r) profiles and normalized Kratky plots at all temperatures (Figs. 3 and 4) were consistent with an unfolded chain, although the fitted slopes of the Kratky plots at high q were above the limiting value of 0.6 for a Gaussian chain in good solvent. This is likely due to the uncertainties arising from the difficulty of background subtraction at high q-values in which scattering intensity is quite low, especially for such a small protein. Low contrast, always an issue in SAXS experiments, is exacerbated in high-pressure SAXS because the density of the solvent increases with pressure. Despite these technical issues, the Kratky plots, P(r) plots, and Rg-values from Guinier and P(r) analysis are clearly consistent with the notion that CTL9-I98A populates predominantly the unfolded state ensemble at all temperatures and 250 MPa. Rg values obtained using the molecular form factor method (43) (Fig. S2) were also in reasonable agreement with those obtained from Guinier and P(r) analysis, despite the limited quality of the plots. However, given the technical issues discussed above, no detailed analysis of the unfolded state ensemble characteristics from the Kratky plots is warranted. Although it is possible that even higher pressures could lead to further expansion of the unfolded chain, we have found in the past that the unfolded state Rg-value is invariant with pressure (5,9,25,44). Likewise, the hydrated radius for the intrinsically disordered protein α-synuclein is pressure independent (45).

Figure 4.

Normalized Kratky plots from the high-pressure SAXS for CTL9-I98A. (A) 5°C (green) and 25°C (orange). (B) 25°C (orange) and 50°C (blue).

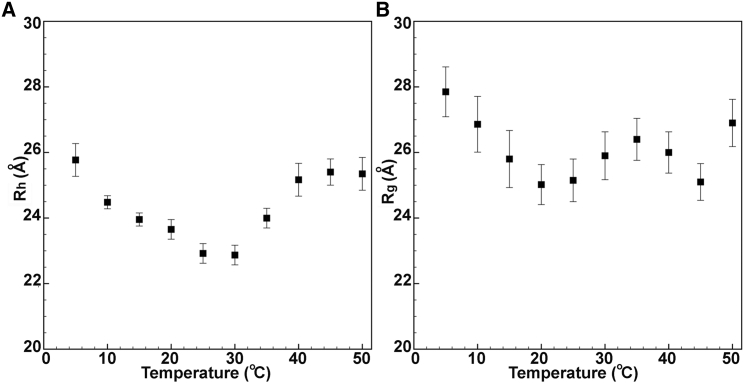

We sought to confirm the results of the high-pressure SAXS studies of the temperature dependence of the compactness of the unfolded state of CTL9-I98A using an orthogonal approach: high-pressure pulsed field gradient diffusion NMR measurements (DOSY) (46). DOSY measurements provide access to molecular translational diffusion and the Rh via the Stokes-Einstein equation (47). Although absolute values for unfolded chains cannot be deduced from this relation, it is possible to obtain an apparent, effective Rh of the unfolded state ensemble from DOSY decay rates (dprot) based on comparison to that (dref), of an internal standard of known radius (Rhprot = (dref/dprot)Rhref) (48). The temperature dependence of Rh of pressure-unfolded CTL9-I98A (Fig. 5 A) exhibited both a low- and high-temperature expansion, consistent with the results from high-pressure SAXS (Fig. 5 B; Table 1). The average value for the Rg/Rh ratio at 250 MPa over all temperatures was 1.09 ± 0.03, in good agreement with the empirical value (1.06) for unfolded proteins at atmospheric pressure (48). Note that this is much larger than the Rg/Rh ratio for globular proteins (0.775). We note as well that at low temperature, in which comparable measurements of unfolded state Rh-values were obtained at ambient pressure, the high-pressure Rh-values are slightly larger, similar to what we observed when comparing the Rg-values at high and ambient pressure.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the temperature dependence of Rh- and Rg-values for CTL9-I98A. (A) Rh-values obtained from analysis of the high-pressure NMR DOSY experiment versus temperature, and (B) Rg-values obtained from Guinier analysis of the high-pressure SAXS data versus temperature. Error bars correspond to the standard deviation calculated from the uncertainty of the fits of the DOSY and SAXS data.

Discussion

These experiments demonstrate first, that at all temperatures, the high-pressure unfolded state appears to be actually less, rather than more, compact than the unfolded state at ambient pressure, indicating that residual interactions in the unfolded state ensemble are actually slightly more disrupted at high pressure. We note that differences in the Rg-values may arise in part from the uncertainty associated with the deconvolution procedure used previously for atmospheric pressure studies (31). The difficulty arose because at atmospheric pressure, the ensemble comprises a combination of the folded and unfolded states. We note that the high-pressure DOSY values are slightly larger than those measured at atmospheric pressure and low temperature (31) as well (Table 1). Because the folded and unfolded state peaks are distinguishable in the NMR experiment, the prior DOSY measurements at atmospheric pressure did not suffer from deconvolution uncertainties, supporting the notion that the high-pressure unfolded state is slightly less compact than that observed at atmospheric pressure. Second, the compaction of the pressure-unfolded state of CTL9-I98A exhibits an expansion at low temperatures, like the unfolded state at atmospheric pressure. The expansion observed at low temperature is likely due to a decrease in hydrophobic interactions in the denatured state ensemble at lower temperature, as previously discussed (31). Third, the high-pressure unfolded state appears somewhat more compact than that observed at high denaturant concentration, especially at higher temperatures. Finally, these experiments suggest expansion of the unfolded state of the protein at high pressure with increasing temperature above 30°C. This high temperature expansion of the pressure-unfolded state is less pronounced than that observed at low temperature and may arise from increased electrostatic repulsion as the hydration layer becomes less tightly bound with increasing temperature.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no prior reported studies of the temperature dependence of the dimensions of the high-pressure unfolded state of a protein. These observations strongly support the notion that in the absence of intermediate states that exhibit a combination of folded and unfolded regions, the structural properties of pressure-unfolded states of proteins do not differ substantially from those of unfolded states at atmospheric pressure and are, if anything, more, rather than less, expanded than their atmospheric state counterparts. More studies of the compactness of the pressure-unfolded states are needed to test the generality of the observations reported here, but the extremely similar temperature-dependent profiles of compaction versus temperature for atmospheric and high pressure are striking. The results argue that pressure offers a minimally invasive, highly reversible means to populate unfolded states over a range of temperatures (or other solvent conditions), thus allowing their fundamental conformational preferences and dynamics to be interrogated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Qingqiu Huang for assistance in synchrotron data collection.

The work was supported by an award from the National Science Foundation MCB 1514575 to C.A.R. and National Institutes of Health grant GM 078114 to D.P.R. This work is based upon research conducted at the Center for High Energy X-ray Sciences, which is supported by the National Science Foundation under award DMR-1829070, and the Macromolecular Diffraction at Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source facility, which is supported by award 1-P30-GM124166-01A1 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health, and by New York State’s Empire State Development Corporation.

Editor: Scott Showalter.

Footnotes

Junjie Zou’s present address is Shenzhen Jingtai Technology Co., Ltd. (XtalPi), Longhua District, Shenzhen 518000, China.

Balasubramanian Harish’s present address is Department of Physical Chemistry, Technical University of Dortmund, 44227 Dortmund, Germany.

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2021.04.031.

Author contributions

B.H. acquired the data, analyzed the SAXS and NMR data, and wrote the manuscript. R.E.G. assisted in high pressure SAXS data acquisition and analysis. J.Z. prepared the samples. J.W. assisted in high pressure SAXS data acquisition. D.P.R. conceived the study and wrote the manuscript. C.A.R. conceived the study, directed the study, analyzed high SAXS data, and wrote the manuscript.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Roche J., Royer C.A., Roumestand C. Exploring protein conformational landscapes using high-pressure NMR. Methods Enzymol. 2019;614:293–320. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu Y., Kasinath V., Wand A.J. Coupled motion in proteins revealed by pressure perturbation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:8543–8550. doi: 10.1021/ja3004655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roche J., Louis J.M., Best R.B. Pressure-induced structural transition of mature HIV-1 protease from a combined NMR/MD simulation approach. Proteins. 2015;83:2117–2123. doi: 10.1002/prot.24931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fossat M.J., Dao T.P., Royer C.A. High-resolution mapping of a repeat protein folding free energy landscape. Biophys. J. 2016;111:2368–2376. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jenkins K.A., Fossat M.J., Royer C.A. The consequences of cavity creation on the folding landscape of a repeat protein depend upon context. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E8153–E8161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1807379115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akasaka K. Exploring the entire conformational space of proteins by high-pressure NMR. Pure Appl. Chem. 2003;75:927–936. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roche J., Dellarole M., Roumestand C. Exploring the protein folding pathway with high-pressure nmr: steady-state and kinetics studies. Subcell. Biochem. 2015;72:261–278. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9918-8_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roche J., Dellarole M., Royer C.A. Effect of internal cavities on folding rates and routes revealed by real-time pressure-jump NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:14610–14618. doi: 10.1021/ja406682e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panick G., Vidugiris G.J., Royer C.A. Exploring the temperature-pressure phase diagram of staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4157–4164. doi: 10.1021/bi982608e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roche J., Caro J.A., Royer C.A. Cavities determine the pressure unfolding of proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:6945–6950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200915109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ando N., Barstow B., Gruner S.M. Structural and thermodynamic characterization of T4 lysozyme mutants and the contribution of internal cavities to pressure denaturation. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11097–11109. doi: 10.1021/bi801287m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramanujam V., Alderson T.R., Bax A. Protein structural changes characterized by high-pressure, pulsed field gradient diffusion NMR spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 2020;312:106701. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2020.106701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuentes E.J., Wand A.J. Local stability and dynamics of apocytochrome b562 examined by the dependence of hydrogen exchange on hydrostatic pressure. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9877–9883. doi: 10.1021/bi980894o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panick G., Malessa R., Winter R. Differences between the pressure- and temperature-induced denaturation and aggregation of β-lactoglobulin A, B, and AB monitored by FT-IR spectroscopy and small-angle X-ray scattering. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6512–6519. doi: 10.1021/bi982825f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hummer G., Garde S., Pratt L.R. The pressure dependence of hydrophobic interactions is consistent with the observed pressure denaturation of proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:1552–1555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hummer G., Garde S., Pratt L.R. An information theory model of hydrophobic interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:8951–8955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins M.D., Hummer G., Gruner S.M. Cooperative water filling of a nonpolar protein cavity observed by high-pressure crystallography and simulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:16668–16671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508224102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Oliveira G.A.P., Silva J.L. A hypothesis to reconcile the physical and chemical unfolding of proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E2775–E2784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500352112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puthenpurackal Narayanan S., Maeno A., Akasaka K. Extensively hydrated but folded: a novel state of globular proteins stabilized at high pressure and low temperature. Biophys. J. 2012;102:L8–L10. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamatari Y.O., Smith L.J., Akasaka K. Cavity hydration as a gateway to unfolding: an NMR study of hen lysozyme at high pressure and low temperature. Biophys. Chem. 2011;156:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nucci N.V., Valentine K.G., Wand A.J. High-resolution NMR spectroscopy of encapsulated proteins dissolved in low-viscosity fluids. J. Magn. Reson. 2014;241:137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva J.L., Weber G. Pressure stability of proteins. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1993;44:89–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pc.44.100193.000513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li T.M., Hook J.W., III, Weber G. Plurality of pressure-denatured forms in chymotrypsinogen and lysozyme. Biochemistry. 1976;15:5571–5580. doi: 10.1021/bi00670a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tugarinov V., Libich D.S., Clore G.M. The energetics of a three-state protein folding system probed by high-pressure relaxation dispersion NMR spectroscopy. Angew Chem. Int.Engl. 2015;54:11157–11161. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y., Berghaus M., Royer C.A. High-pressure NMR and SAXS reveals how capping modulates folding cooperativity of the pp32 leucine-rich repeat protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2018;430:1336–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roche J., Royer C.A. Lessons from pressure denaturation of proteins. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2018;15:20180244. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2018.0244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nettels D., Müller-Späth S., Schuler B. Single-molecule spectroscopy of the temperature-induced collapse of unfolded proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:20740–20745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900622106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Privalov P.L., Gill S.J. Stability of protein structure and hydrophobic interaction. Adv. Protein Chem. 1988;39:191–234. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wuttke R., Hofmann H., Schuler B. Temperature-dependent solvation modulates the dimensions of disordered proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:5213–5218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313006111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adrover M., Martorell G., Pastore A. The role of hydration in protein stability: comparison of the cold and heat unfolded states of Yfh1. J. Mol. Biol. 2012;417:413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stenzoski N.E., Luan B., Raleigh D.P. The unfolded state of the C-terminal domain of L9 expands at low but not at elevated temperatures. Biophys. J. 2018;115:655–663. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stenzoski N.E., Zou J., Raleigh D.P. The cold-unfolded state is expanded but contains long- and medium-range contacts and is poorly described by homopolymer models. Biochemistry. 2020;59:3290–3299. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho B.K., Gruswitz F. HOLLOW: generating accurate representations of channel and interior surfaces in molecular structures. BMC Struct. Biol. 2008;8:49. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luan B., Shan B., Raleigh D.P. Cooperative cold denaturation: the case of the C-terminal domain of ribosomal protein L9. Biochemistry. 2013;52:2402–2409. doi: 10.1021/bi3016789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato S., Raleigh D.P. pH-dependent stability and folding kinetics of a protein with an unusual α-β topology: the C-terminal domain of the ribosomal protein L9. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;318:571–582. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Y., Gupta R., Raleigh D.P. Mutational analysis of the folding transition state of the C-terminal domain of ribosomal protein L9: a protein with an unusual beta-sheet topology. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1013–1021. doi: 10.1021/bi061516j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y., Horng J.C., Raleigh D.P. pH dependent thermodynamic and amide exchange studies of the C-terminal domain of the ribosomal protein L9: implications for unfolded state structure. Biochemistry. 2006;45:8499–8506. doi: 10.1021/bi052534o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang S., Zhang Y., Royer C.A. Pressure-temperature analysis of the stability of the CTL9 domain reveals hidden intermediates. Biophys. J. 2019;116:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rai D.K., Gillilan R.E., Gruner S.M. High-pressure small-angle X-ray scattering cell for biological solutions and soft materials. J. Appl. Cryst. 2021;54:111–122. doi: 10.1107/S1600576720014752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hopkins J.B., Gillilan R.E., Skou S. BioXTAS RAW: improvements to a free open-source program for small-angle X-ray scattering data reduction and analysis. J. Appl. Cryst. 2017;50:1545–1553. doi: 10.1107/S1600576717011438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Semenyuk A.V., Svergun D.I. GNOM. A program package for small-angle scattering data processing. J. Appl. Cryst. 1991;24:537–540. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y., Shan B., Raleigh D.P. The cold denatured state is compact but expands at low temperatures: hydrodynamic properties of the cold denatured state of the C-terminal domain of L9. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;368:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riback J.A., Bowman M.A., Sosnick T.R. Innovative scattering analysis shows that hydrophobic disordered proteins are expanded in water. Science. 2017;358:238–241. doi: 10.1126/science.aan5774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panick G., Malessa R., Royer C.A. Structural characterization of the pressure-denatured state and unfolding/refolding kinetics of staphylococcal nuclease by synchrotron small-angle X-ray scattering and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;275:389–402. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roche J., Ying J., Bax A. Impact of hydrostatic pressure on an intrinsically disordered protein: a high-pressure NMR study of α-synuclein. ChemBioChem. 2013;14:1754–1761. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao M., Harish B., Winter R. Temperature and pressure limits of guanosine monophosphate self-assemblies. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:9864. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10689-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Price W. NMR Studies of Translational Motion: Principles and Applications, Cambridge Molecular Science. Cambridge University Press; 2010. Theory of NMR diffusion and flow measurements; pp. 69–119. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilkins D.K., Grimshaw S.B., Smith L.J. Hydrodynamic radii of native and denatured proteins measured by pulse field gradient NMR techniques. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16424–16431. doi: 10.1021/bi991765q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.