Abstract

Using various mutants, we investigated to date the roles of the Fe-histidine (F8) bonds in cooperative O2 binding of human hemoglobin (Hb) and differences in roles between α- and β-subunits in the α2β2 tetramer. An Hb variant with a mutation in the heme cavity exhibited an unexpected feature. When the β mutant rHb (βH92G), in which the proximal histidine (His F8) of the β-subunit is replaced by glycine (Gly), was subjected to ion-exchange chromatography (Q Sepharose column) and eluted with an NaCl concentration gradient in the presence of imidazole, yielded two large peaks, whereas the corresponding α-mutant, rHb (αH87G), gave a single peak similar to Hb A. The β-mutant rHb proteins under each peak had identical isoelectric points according to isoelectric focusing electrophoresis. Proteins under each peak were further characterized by Sephadex G-75 gel filtration, far-UV CD, 1H NMR, and resonance Raman spectroscopy. We found that rHb (βH92G) exists as a mixture of αβ-dimers and α2β2 tetramers, and that hemes are released from β-subunits in a fraction of the dimers. An approximate amount of released hemes were estimated to be as large as 30% with Raman relative intensities. It is stressed that Q Sepharose columns can distinguish differences in structural flexibility of proteins having identical isoelectric points by altering the exit rates from the porous beads. Thus, the role of Fe-His (F8) bonds in stabilizing the Hb tetramer first described by Barrick et al. was confirmed in this study. In addition, it was found in this study that a specific Fe-His bond in the β-subunit minimizes globin structural flexibility.

Significance

Using various mutants, we revealed to date the roles of the Fe-histidine (His F8) bonds in cooperativity of human hemoglobin and differences in roles between α- and β-subunits in the α2β2 tetramer. In this study, we found another roles of the Fe-His (F8) bond of β-subunit in particular. This finding is important to understand the flexibility and its concomitant stability of the tetramer structure. Another unexpected finding in this study is that an ion-exchange column (Q Sepharose column) in chromatography can distinguish the flexibility of proteins having identical isoelectric points. This has general significance for people who use Q Sepharose column in separation of proteins.

Introduction

Human adult hemoglobin (Hb A) transports O2 effectively from the lungs to tissues through cooperative O2 binding. Hb A is composed of two α- (141 residues) and two β-subunits (146 residues) that form α2β2 tetramers (1,2). Under physiological conditions, Hb A exists as an equilibrium of (αβ) dimers and α2β2 tetramers, with the equilibrium heavily favoring tetramers. Each subunit has one protoheme (Fe-protoporphyrin-IX complex). Histidine 8 in the F helix (His F8) (see Fig. 1) contributes to the coordinated binding of Fe in heme (3,4), and is called the proximal His. Hereafter, we call this bond the “Fe-His bond.” An O2 molecule binds to the distal coordination site of heme Fe. The binding of O2 to the tetramers is cooperative, and the most accepted explanations for binding and release behavior are the MWC (concerted) (5) and KNF (sequential) models (6). Much effort has been devoted to elucidating the mechanism of cooperativity, and some reviews and original articles are still periodically republished (7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19).

Figure 1.

Relationships between heme and helix F (blue ribbon) of the β-subunits in Hb A (right) and rHb (βH92G) (left). As normal β-subunits of Hb A have Fe-His bonds, there is a covalent linkage between the Im ring of β92His and helix F. Although the β-subunits of rHb (βH92G) have Fe-Im (Im) bonds, there is no covalent linkage between the Im ring and helix F. The molecular structure of Hb A is taken from PDB: 2DN2 (20), and that of rHb (βH92G) is shown by in silico mutagenesis of PDB: 2DN2 (20). To see this figure in color, go online.

The Fe-His bond is the only coordinate covalent bond between heme and globin. This bond has been examined by NMR (21) and Raman (22) spectroscopy studies in investigations of cooperativity. We have characterized the T and R states according to the MWC model by observing the Fe-His stretching Raman band of deoxy Hb (23,24). We previously examined the Hb cavity mutant (in which HisF8 is replaced with glycine (Gly)) in the presence of imidazole (Im), and discussed the differing effects of the Fe-His bonds of the α- and β-subunits on cooperativity. The absence of the Fe-His bond in the α-subunit inhibits the quaternary structure change from T to R upon O2-binding. Its absence in the β-subunit simply enhances the O2 affinity of the α-subunit (8). Subsequent to these studies, we learned that Barrick et al. (25) investigated the same cavity mutants and found the β-mutant, rHb (βH92G) to be dimers on the basis of a sedimentation coefficient of 2.81 for CO-bound rHb (βH92G). In our previous study, we noticed that the rHb (βH92G) eluate contained a mixture of several proteins, but analyzed functional features only for the tetramer component after separation. The corresponding α-mutant, rHb (αH87G), was uniformly α2β2 tetramers. Here, we report that Q Sepharose (an anion exchange resin) recognized structural differences between the α2β2 tetramers and the αβ-dimers despite their identical isoelectric points (pIs).

Materials and methods

Preparation and purification of hemoglobin variants

Hb A was purified from human hemolysate by preparative isoelectric focusing (26). Human hemolysate was prepared from concentrated erythrocytes (a gift from the Japanese Red Cross Kanto-Koshinetsu Block Blood Center). A natural mutant Hb Hirose (βW37S) was prepared from 30% glycerol containing erythrocytes frozen at −80°C according to a previously described method (26).

Recombinant Hb A was prepared according to a previously described method (8). Both rHb (αH87G) and rHb (βH92G) were prepared and purified by Q Sepharose column chromatography (ion-exchange chromatography) according to a previously described method (8). Both rHb (βW37H) and rHb (αY42L) were prepared according to a previously described method (27,28). The two-step rHb purification process using Q Sepharose column chromatography is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

rHb purification using a two-step Q Sepharose column chromatography protocol. Left: Q1 column equilibrated at pH 7.4. Hb does not bind, but E. coli-derived proteins and DNA fragments do. Right: Q2 column equilibrated at pH 8.3. rHb and Hb A typically bind, but other proteins such as lysozyme do not. The rHb and Hb A bound to the Q2 column are eluted with an increasing concentration gradient of NaCl. The NaCl solution for eluting samples of rHb (αH87G) and rHb (βH92G) contains 10 mM Im. The Q1 eluate is loaded onto the Q2 column. To see this figure in color, go online.

Q Sepharose chromatography

Q Sepharose is composed of porous, cross-linked 6% agarose beads, in which each pore wall is coated with quaternary ammonium (Q) strong cations. Anionic proteins were captured in each pore. Pore size corresponds to a globular protein with an exclusion limit of Mw = 4 × 106 Da. Because the size of Hb is 6 × 104 Da, several Hb molecules, and nonheme Escherichia coli-derived proteins can be captured in a single pore simultaneously. When the column was equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.4 (Q1 column), nucleic acids, most bacterial proteins, and the lysozyme added to lyse bacterial cell walls bind to the resin, but rHb passes through the column. When the column was run at a higher pH (pH 8.3, Q2 column), rHb and other proteins with similar pIs were captured.

CD measurements

CD spectra of Hbs were measured in the far-UV region at 25°C with a Jasco J-820 spectropolarimeter. Samples contained 6 μM hemoglobin (based on heme concentration) in 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The sample cells had a 2-mm pathlength. For the cavity mutant rHb (βH92G), 1 or 2 mM Im solution was added, and the CD spectrum of a buffer plus Im blank solution was subtracted from the observed CD spectra. The scan speed was 20 nm/min, and 20 scans were averaged. Molar CD (Δε) was calculated per heme and is given in M−1 cm−1.

Resonance Raman measurements

Resonance Raman (RR) spectra of Hbs were obtained by producing an excitation wavelength of 441.6 nm with an He/Cd laser (model CD4805R; Kimmon Koha), and dispersing with a 1-m single polychromator (model MC-100DG; Ritsu Oyo Kogaku) using the first-order diffraction of a grating with 1200 grooves/nm, and detecting with a UV-coated, liquid-nitrogen-cooled CCD detector (LN/CCD-1100-PB/VISAR/1; Roper Scientific). All hemoglobin samples were adjusted to a heme concentration of 200 μM in 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7). Samples of rHb (βH92G) also contained 10 mM Im. Deoxy Hb A and deoxy rHb (βH92G) were prepared by adding a small amount of sodium dithionite (1 mg/mL) to the oxy form after replacing the air inside the sample cell with N2.

All measurements were performed at room temperature with a cell spinning at 1800 rpm. The laser power at the sample point was 3 mW. To confirm the sample integrity after RR measurements, we obtained a visible absorption spectrum for each sample. Absorption spectra were recorded using a Hitachi U-3310 spectrophotometer. When spectral changes occurred after the RR measurements, the Raman spectra were discarded.

1H NMR measurements

1H NMR spectra were measured using a Bruker AVANCE 400 and 600 FT NMR spectrometer operating at 1H frequencies of 400 and 600 MHz, respectively. Measurements were recorded at 308 K for rHb (βH92G) and Hb A and between 278 and 318 K for rHb (αH87G). Concentrations of Hb A, rHb (αH87G), and rHb (βH92G) were 1, 3, and 0.3 mM, respectively, based on heme concentrations. In addition, rHb (αH87G) and rHb (βH92G) contained 10 mM Im. To obtain the azide form, a solution containing 10 heme equivalents of sodium azide was added to comparable metHb solutions. All Hb samples were measured at pH 8.0, or pD 8.0, in 0.02 M phosphate buffer. Details of 1H NMR experiments have been previously described (29).

Simulation of difference Raman spectra

The Raman spectra shown later will mainly consist of three bands; Cβ-Cc-Cd-bending mode, δ(CβCcCd), Fe-His-stretching mode, νFe-His, and Fe-Im-stretching modes, νFe-Im. Here, we postulate that their spectra are the same between α- and β-subunits. When the β-subunits in α2β2 tetramer are mutated and have the Im-coordinated heme instead of the His-coordinated heme, tetramer spectrum (T0) consists of 4δ + 2Im + 2His, where δ, Im, and His denote Raman intensities of δ(CβCcCd), νFe-Im, and νFe-His bands, respectively. The αβ-dimer spectrum (D0) is assumed to be 2δ + Im + His. If a proportion x of β-subunits in the αβ-dimers loses its heme before observation but α contains complete natural heme, the observed spectrum of dimer (2 × Dx) arises from a (2 − x) proportion of the δ(CβCcCd) band, a (1 − x) proportion of the νFe-Im, band, and the full νFe-His band. Thus, the practical spectrum of the αβ-dimer should be 2 × Dx = 2(2 − x) × δ + 2(1 − x) × Im + 2 × His.

We try to determine the value of x from the calculation of the tetramer – 2 × dimer difference spectrum. If a compound such as (NH4)2SO4 giving rise to an intensity standard was contained in the solution, we would be able to normalize spectra of 2 × dimer and tetramer based on the intensity of the standard band. Unfortunately, because no such intensity standard was included in this experiment, we normalized the spectra of the dimers and tetramers with the intensity of the δ(CβCcCd) mode of the porphyrin macrocycle. This band is assumed to be common to the dimers and tetramers as well as to the α- and β-subunits.

When x portion of hemes of β-subunits are depleted, the observed δ(CβCcCd) band for dimer should be weaker than in the case in which there were no depletion of heme, by (4 – 2x)/4. This would be taken into consideration when we compare the observed dimer spectrum with that of tetramer with the intensity adjustment of the dimer δ(CβCcCd) band to be the same as that of tetramer.

Results

Q Sepharose chromatography

Fig. 3 shows the elution patterns of rHb (αH87G) and rHb (βH92G) from the Q2 Sepharose column. The elution pattern of rHb (αH87G) was a single peak, whereas that of rHb (βH92G) was frequently two or more peaks. In the figure, rHb (βH92G) eluted as two peaks (Q2-I and Q2-II). To date, rHb (βH92G) has never been eluted as a single peak. The NaCl concentration at which the rHb (αH87G) peak appears is almost the same as that for native Hb A (upper panel in Fig. S1) and rHb A (Fig. S1, lower panel) and its elution always produces a single peak. The elution patterns of rHb (βH92G) are different from those of native Hb A (derived from human erythrocytes), rHb A, and rHb (αH87G). Two peaks (Q2-I and Q2-II) always appear, and additional peaks appear occasionally. The fraction numbers of the two peaks are slightly different from those of rHb (αH87G), despite the fact that all of these proteins are thought to have an identical electric charge. The amounts of Q2-I and Q2-II are nearly equal. Therefore, we examined the characteristics of rHb (βH92G) under the two main peaks relative to those of rHb (αH87G).

Figure 3.

Elution patterns of rHb (αH87G) and rHb (βH92G) in Q2 Sepharose column chromatography. The black dotted line in each elution pattern shows the NaCl concentration gradient (0–0.16 M). The column (1.5 × 17 cm) was equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.3) containing 10 mM Im. After the Q2 column was loaded with the Q1 eluate and washed with equilibration buffer, bound Hb was eluted with a linear gradient (total 300 mL) from 0 to 0.16 M NaCl in equilibration buffer. To see this figure in color, go online.

First, the protein pIs were examined. Isoelectric focusing patterns of Q2-I and Q2-II were studied on an ampholine plate gel (pH 3.5–9.5) using Hb A and Mb as references. As shown in Fig. 4, Q2-I and Q2-II focused in almost the same position, suggesting that the two fractions separated by Q2 Sepharose have the same pI. In a recently published study, a mutant rHb (mutation at β37Trp) showed a similar elution profile to that of Hb A, although it is known to have a different pI from Hb A (26). Therefore, Q Sepharose used under present equilibrium conditions (pH 8.3) does not separate proteins exclusively by pI, but by other features as well.

Figure 4.

Isoelectric focusing profiles on an ampholine plate gel (pH 3.5–9.5) of peak fractions from Q2 Sepharose column chromatography of rHb (βH92G) compared with Mb and Hb A. Samples of Q2-0, Q2-I, and Q2-II were taken from labeled peak fractions in Fig. 3. Horse heart myoglobin was used for Mb. Hb A was loaded in both outside lanes of the gel to assess whether or not electrophoresis ran correctly.

Second, molecular masses were examined. The Sephadex G-75 gel filtration elution profile of rHb (αH87G) is shown in Fig. 5 A. T, D, and M denote the expected positions for tetramers, dimers, and monomers, respectively. It is clear that rHb (αH87G) is in the tetramer form. The Sephadex G-75 gel filtration patterns of the eluates corresponding to the two main peaks (Q2-I and Q2-II in Fig. 3) of rHb (βH92G) eluted from Q2 Sepharose are depicted in Fig. 5 B. Their elution profiles were compared with those of Hb Hirose (βTrp37 → Ser) and Hb A. Peaks of Hb Hirose and Hb A correspond to positions of dimers (26) and tetramers, respectively. Thus, the Q2-II and Q2-I fractions of rHb (βH92G) were eluted mainly at tetramer and dimer positions, respectively, although both are mixtures of tetramers and dimers.

Figure 5.

G-75 gel filtration results. (A) Elution pattern of rHb (αH87G) (peak fraction from the Q2 column) from a Sephadex G-75 gel filtration column. T, D, and M indicate expected positions of tetramers, dimers, and monomer, respectively. The position of tetramers (T) is inferred from elution of Hb A. That of dimers (D) is from Hb Hirose (βTrp37 → Ser) (26), and that of monomer (M) is from sperm whale myoglobin. Void volume was determined with blue dextran. The Sephadex G-75 column was 1.5 × 115 cm and equilibrated with 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 10 mM Im at 4°C. One-milliliter samples of 150 μM protein (based on heme concentration) were applied to the column. (B) Sephadex G-75 gel filtration column elution patterns of Q2-II (left) and Q2-I (right) fractions of rHb (βH92G) (red) in 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 10 mM Im. The patterns for Hb A (dotted orange) and Hb Hirose (dotted blue) are displayed for comparison. To see this figure in color, go online.

To address whether the separation of Q2-I from Q2-II by Q2 Sepharose was due to different multimeric states (dimer versus tetramer), and to examine whether the elution peak of the Q2-I fraction of rHb (βH92G) overlaps with unknown contaminating proteins derived from E. coli, we examined the Q2 Sepharose elution profile of two other mutant Hbs, rHb (βW37H) and rHb (αY42L), which are known to exclusively form dimers and tetramers, respectively (27,28). The results are shown in Fig. S2. Both mutants eluted in a single peak at a position similar to rHb A (red in Fig. S2) when monitored with visible light at 576 nm. However, when monitored with UV absorption at 280 nm, rHb (αY42L) gave several peaks near column numbers 45 and 55 (black curve in Fig. S2 B). rHb (βH92G) would exhibit similar patterns when monitored by UV absorbance. These peaks are thought to arise from contaminating proteins derived from E. coli cells. These E. coli proteins do not bind hemes, so they produce no observable peak at 576 nm.

In contrast to rHb (αH87G), rHb (βH92G) eluted in two peaks detectable at 576 nm (Fig. 3). Although it is highly possible that the Q2-I of rHb (βH92G) elutes a small amount of nonheme proteins around fraction number 45, this is irrelevant to the separation of Q2-II from Q2-I. The Q2-II fraction contained very little E. coli protein, as inferred by similar molar CD (Δε) values at 222 nm (α-helix content) of Hb A and Q2-II (Fig. 6 B).

Figure 6.

(A) Far-UV CD spectra of Hb A (red) and rHb (αH87G) (blue). Molar CD (Δε), calculated per heme, is given in M−1 cm−1. (B) Far-UV CD spectra of Q2-I (blue) and Q2-II fractions (green) of rHb (βH92G) and Hb A (red) with 1 (left) or 2 (right) mM Im. To see this figure in color, go online.

To further characterize the properties of the rHb (βH92G) dimers, we investigated the effect of inositol hexaphosphate (IHP), which generally strengthens tetramerization of αβ to α2β2 in human Hb A. Elution patterns from the Sephadex G-75 gel filtration column are shown for rHb (βH92G) dimer (Q2-I) and Hb Hirose (Fig. S3). The addition of IHP to Hb Hirose caused an equilibrium shift from dimers to tetramers (26). With rHb (βH92G), addition of IHP induced only a slight increase in the tetramers. A strong dimer peak remained. Hb Hirose has an Fe-His bond in its β-subunits, whereas rHb (βH92G) lacks this bond in its β-subunits. These results suggest that the Fe-His bond in the β-subunit is required for the tetramerizing effect of IHP.

Spectroscopy

Far-UV CD spectra

Protein structures were examined using far-UV CD spectroscopy. Fig. 6 A shows far-UV CD spectra of Hb A (red) and rHb (αH87G) (blue). Fig. 6 B shows the spectra of rHb (βH92G) in the presence of 1 (left) and 2 (right) mM Im. The far-UV CD spectrum between 210 and 240 nm reflects protein secondary structures. In particular, a large negative CD band at 222 nm is characteristic of the α-helix, although absorption of Im itself in the far-UV region hindered protein measurements by CD below 210 nm.

In Fig. 6 A, the absolute value of molar CD (Δε) at 222 nm for rHb (αH87G) is almost the same as that for Hb A, meaning that the α-helical content of rHb (αH87G) is almost the same as that of native Hb A. This feature was unaltered by the addition of Im. In Fig. 6 B, however, the absolute value of molar CD (Δε) at 222 nm for the Q2-II fraction of rHb (βH92G) (green) is slightly larger than that of Hb A (red) (27% with 1 mM Im, 5% with 2 mM Im). Im binding to heme probably stabilizes the native protein structure in the mutated β-globin. These results indicate that the secondary structure of native hemoglobin is more easily perturbed in rHb (βH92G) than in rHb (αH87G). This implies that the tertiary structure is less rigid in the rHb (βH92G).

The Δε-value at 222 nm for the Q2-I fraction of rHb (βH92G) (blue) is approximately twice that of Hb A, indicating that larger amounts of α-helix are contained in proteins in the Q2-I fraction of rHb (βH92G). Note that the molar CD value per heme is based on the heme concentration. Possible reasons for this difference in molar CD values are 1) proteins derived from E. coli may be contaminating, 2) appreciable amounts of heme are released from rHb (βH92G), or 3) a combination of 1) and 2).

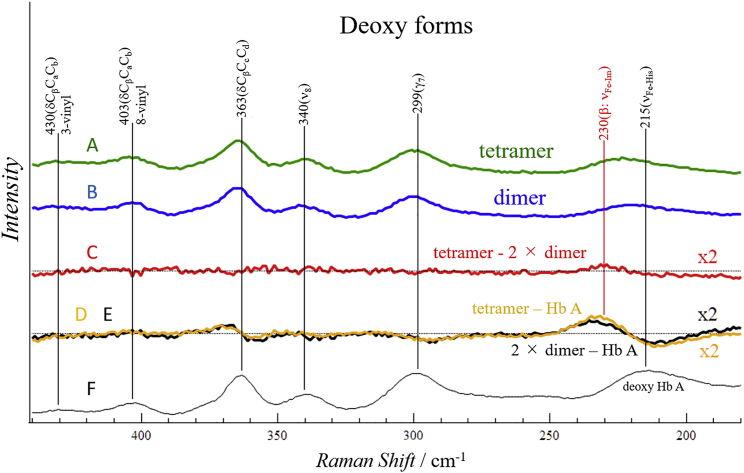

RR spectra of tetrameric and dimeric rHb (βH92G)

The RR spectra of deoxy rHb (βH92G) in Q2-II (mainly tetramer) and Q2-I (mainly dimer) with an excitation wavelength of 441.6 nm are shown in (A) and (B), respectively, in Fig. 7. Upon excitation at 441.6 nm, many vibrational modes of heme in deoxy Hb are strongly enhanced in intensity. The RR spectra of tetrameric (α2β2) and dimeric (αβ) rHb (βH92G) in the deoxy state are very similar. Only the band shape near Fe-His-stretching (νFe-His) and Fe-Im-stretching bands (νFe-Im) differ somewhat from each other. We calculated the difference between spectra (tetramer – 2 × dimer) by normalizing the spectra using the band from the porphyrin skeleton at 365 cm−1 (δCβCcCd) (red curve (C)). In principle, the spectra should cancel, thus producing no peak. Nevertheless, the difference spectrum gave a positive peak at 230 cm−1. As we previously estimated the νFe-Im (β-subunit) and νFe-His (α-subunit) frequencies of rHb (βH92G) tetramers by an established deconvolution method (8); the positive peak at 230 cm−1 and a weak negative peak at 215 cm−1 are attributed to νFe-Im (β-subunit) and νFe-His (α-subunit), respectively.

Figure 7.

RR spectra of rHb (βH92G) and Hb A: (A) tetramer (α2β2) of rHb (βH92G); (B) 2 × dimer (αβ) of rHb (βH92G); (C) difference spectrum = tetramer − 2 × dimer; (D and E) and difference spectra, orange (D) = tetramer – Hb A, black (E) = 2 × dimer – Hb A. (F) Hb A in deoxy form in 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7). To see this figure in color, go online.

To confirm the presence of the difference peak, we calculated two other difference spectra: 2 × Dimer – Hb A and tetramer – Hb A, as depicted in black (E) and orange (D) in Fig. 7. Note that the β-subunit contains a native His-bound heme in Hb A but an Im-bound heme in the mutants. As expected, the difference spectra gave a positive peak for νFe-Im and a negative peak for νFe-His. This feature is common to the dimers and tetramers. Contrary to this expectation, the intensities of the positive peaks are slightly different, whereas those of the negative peaks are similar. The intensity of the positive peak of dimer was slightly weaker than that of the tetramer. This is thought to be due to the appreciable depletion of hemes from the β-subunits of αβ-dimers. The difference in area intensities between curves (D) and (E) in the 250–200 cm−1 region corresponds to the amount of released hemes, and it is quantitatively estimated with simulation method described in the Materials and methods section.

Estimation of heme depletion

The difference Raman spectra (D) and (E) in Fig. 7 gave appreciable peaks at frequencies below 300 cm−1, which were attributed to partial depletion of hemes from the β-subunits of dimers. The amount of depletion is estimated through the spectral simulations described in the Materials and methods section.

A part of the observed spectra (i.e., spectra in the δ(CβCcCd), νFe-Im, and νFe-His regions) of tetrameric and dimeric rHb (βH92G) shown in Fig. 7 are reproduced in (A) and (B) in Fig. 8, respectively, in which the spectrum of the porphyrin macrocycle is represented by a single band at 365 cm−1. The tetramer – dimer difference spectrum (A and B, which are shown in red in Fig. 7) is reproduced as spectrum (C) in Fig. 8. Because an intensity standard compound was not contained in the solution, the spectra (A) and (B) are normalized based on the intensity of the δ(CβCcCd) mode of the porphyrin macrocycle at 365 cm−1. This band is assumed to be common to the dimers and tetramers as well as to the α- and β-subunits. The observed spectrum of the tetramers has previously been simulated with Gaussian band-shape functions, and the bands in the 250–150 cm−1 region were deconvoluted into component bands (8). The simulated spectrum and its component bands, νFe-Im, and νFe-His, and their sum are depicted as spectra (D) in Fig. 8.

Figure 8.

Simulation of RR spectra to estimate the fraction of heme released. The δ(CβCcCd) band of the porphyrin macrocycle at 365 cm−1, and the νFe-Im and νFe-His bands around 230–210 cm−1 in the observed spectra of tetramer and dimer from Fig. 7 are reproduced in (A) and (B), respectively. Intensities of δ(CβCcCd) relative to νFe-Im and νFe-His bands in the spectra of the tetramer and dimer are the same as those in Fig. 7. (C) The difference spectrum, tetramer – 2 × dimer, (same as the red curve in Fig. 7). (D) The simulated spectrum of α2β2 tetramer of cavity mutants reported in (8). In this figure, however, only the peak frequency of the β-subunit is shifted from 223 to 225 cm−1 with no change in intensity. (E) The calculated spectra of dimer (Dx; broken line) and the tetramer-dimer difference spectra (Δ; solid line) for the assumed values x = 0.3 (E1) and x = 0.5 (E2). To see this figure in color, go online.

As noted earlier, the observed δ(CβCcCd) band for dimer is weaker than in the case in which there were no depletion of heme, by (4 − 2x)/4. In the representation of observed spectra in Fig. 8, we adjusted the intensity of the dimer δ(CβCcCd), band to be the same as that of tetramer by multiplying the observed dimer spectrum by 4/(4 − 2x). As a result, a normalized spectrum-representing dimer is 4 × Dx/(4 − 2x) = 4δ + 4[(2 − 2x)/(4 − 2x)] × Im + [8/(4 − 2x)] × His. The difference spectrum (Δ) between tetramer and normalized dimer (4 × Dx/(4 − 2x)) becomes, Δ = (tetramer (T0)) – 4 × Dx/(4 − 2x) = [4x/(4 − 2x)] × (Im – His). The difference spectrum is expected to give no peak for the δ(CβCcCd) band, and weak intensities for the νFe-Im and νFe-His bands because of their cancellation. Thus, the normalized dimer spectra (Dx) and difference spectra (Δ) were calculated for typical values of x and were depicted with dashed and solid lines, respectively, for E1 (x = 0.3), and E2 (x = 0.5) in Fig. 8. The x-value that yields a Δ closest to that of spectrum (C), and a 2 × Dx value closest to that of spectrum (B) corresponds to the amount of heme depleted from β-subunits of the dimer. Although the calculated Dx and Δ spectra are not very sensitive to x, we concluded that x is larger than 0.3 and smaller than 0.5. Contrary to our expectation, this simulation was not strongly successful quantitatively, possibly because the assumed band shapes of νFe-Im and νFe-His bands differ in reality between dimer and tetramer.

1H NMR spectra of rHb (αH87G) and tetrameric rHb (βH92G)

Fig. 9 shows the paramagnetically shifted 1H NMR spectra in the 9- to 30-ppm region of the azide (N3−) adduct of metHb A (black) and the ferric form of tetrameric rHb (βH92G) (red). In Hb A, the heme methyl proton signals at positions 2, 12, and 18 in both α- and β-subunits were observed separately. The observed heme methyl proton signals in Hb A indicate that most hemes exist in the normal orientation. Signals from heme in reversed orientation usually appear at different positions (30). The exact normal/reversed heme ratios in α- and β-subunits of Hb A are reported to be 0.98/0.02 and 0.9/0.1, respectively (30). The 1H NMR spectrum of rHb (βH92G) (Fig. 9, upper spectrum) gave 12-Me (α), 2-Me (α), and 18-Me (α) signals at chemical shifts almost identical to those of the α-subunits in the spectrum of Hb A, suggesting that the heme electronic structures of the α-subunits in rHb (βH92G) and Hb A are highly similar. However, the normal α-subunits of rHb (βH92G) gave several additional signals because of hemes with reversed orientation.

Figure 9.

1H NMR spectra of the azide forms of tetrameric ferric rHb (βH92G) (upper spectrum) and metHb A (lower spectrum) at 308 K (pH 8.0) in 20 mM phosphate buffer containing 10 mM Im. The H2O/D2O ratio is 9:1. To see this figure in color, go online.

In tetrameric rHb (βH92G), the percentage of heme with reversed orientation in normal α-subunits was temperature dependent: it was as large as 30% at 308 K, and dropped to 20% at 298 K (29), as estimated from the ratio (1:2.4) of signal intensities of reversed and normal hemes in the upper spectrum. This means that the occurrence of segmental motions within the protein allowed the release and recapture of heme by α-globin. This would be expected to occur more frequently at higher temperatures. This level of freedom of the heme orientation would also be present in the rHb (βH92G) dimers. Therefore, the occurrence of large amplitude-segmental motions is considered characteristic of the rHb (βH92G) globin. Unfortunately, we failed to identify the heme methyl signals of the Im-bound heme in the mutated β-subunit.

The bandwidth (Δv1/2) of heme methyl signals is determined by the T2 relaxation time (= 1/(πΔv1/2)). The observed widths for Hb A are ∼0.3 ppm. Because a 600-MHz apparatus is used, the real width is ∼180 Hz, which corresponds to T2 = 2 ms if a sample is a simple organic compound. Because the heme methyl signals are paramagnetically shifted by the Fe3+ ion of heme, the width becomes broader than it would be in a nonmagnetic organic compound. Usually, T2 is shorter than T1, which is ∼1 s in ferric hemes. The T1-value would be the same in Hb A and in the mutant. We stress that the widths of the rHb (βH92G) heme methyl signals are broader than that of Hb A. This further broadening is presumably due to the inhomogeneity of the magnetic field generated by nearby protein protons at distance r, the magnitude of which is proportional to 1/r6. This inhomogeneous broadening implies the occurrence of magnetic perturbations by the segmental motions of globin upon reversion of heme (in the order of milliseconds).

Fig. S4 shows temperature dependence between 278 and 318 K of paramagnetically shifted 1H NMR spectra of azide (N3−)-bound normal β-heme of rHb (αH87G) in the 10- to 38-ppm region. The behaviors of the heme methyl protons of rHb (αH87G) are different from those of Hb A and rHb (βH92G). From 318 to 298 K, the proton signals of the position 18, 2, and 12 heme methyl groups associated with the β-subunits are observed at chemical-shift values that correspond with normal heme orientation. Below 298 K, other signals marked by “T” appeared, and their intensities increased with further temperature reduction. At 278 K, T peaks are observed at 30.9, 25.1, 21.7, and 18.8 ppm. At 278 K, the peaks at 30.5, 24.9, and 21.0 ppm at 293 K shifted down field to 30.9, 25.1, and 21.7 ppm, but the 18.7 ppm peak seen at 293 K shifted up field to 17.8 ppm.

According to Neya and Morishima (31), a few additional signals, different from those observed for stripped metHbA-azide, appeared upon addition of IHP to the metHbA-azide solution. These were assigned to signals associated with the T-quaternary structure (31). These additional signals were located at 31, 27, 21, and 18 ppm at 294 K (31). The peaks at 31 and 27 ppm shifted downfield, but the 18-ppm signal shifted upfield as the temperature was lowered. The chemical-shift values of the additional peaks are very close to those of the “T”-marked signals in Fig. S4: 30.5, 24.9, 21.0, and 18.7 ppm at 293 K. Furthermore, their intensities in rHb (αH87G) increased as the temperature was lowered. The additional signals observed in the metHb A-azide adduct with IHP addition exhibited the same tendency, and cannot be assigned to signals from reversed heme (31). Accordingly, we assigned the T-marked signals of rHb (αH87G) to heme methyl protons in the azide-bound normal hemes of β-subunits in the T-quaternary structure. Note that the quaternary structure of the tetramers, that is, the atomic dispositions of the intersubunit hydrogen bonds, is retained in rHb (αH87G). This means that the disconnection between helix F and heme in the abnormal α-subunits of rHb (αH87G) stabilizes the T-quaternary structure more than the R-quaternary structure not only in Fe2+-heme but also in Fe3+-heme. In fact, the oxygen affinity of the β-subunits of rHb (αH87G), in which the Fe-His bond is present only in the β-subunit, is low (P50 = 60 mmHg) (8).

Discussion

Chromatography

Protein pIs depend on amino acid composition (32). Because the globins eluted as Q2-I and Q2-II are composed of the same amino acids, they would be expected to have a common pI value. The pI value of HbA was 6.9 (7.0 for Mb) and the pI values of rHbs are between 7.0 and 7.5. Accordingly, all human Hbs do not bind to Q Sepharose at pH 7.4 (Q1 column) but do bind at pH 8.3 (Q2 column). Bound rHbs were eluted from the Q2 column with a linear gradient of NaCl. A minor difference in the pI of rHb apparently does not affect affinity under these column conditions because rHbs are eluted at the same NaCl concentration even if they incorporate mutations that change their pI. Nevertheless, rHb (βH92G) was separated into two fractions by this column, despite the fact that each fraction has the same pI. The positions of both fractions are slightly different from those of rHb (αH87G), which is very similar to that of Hb A.

The rHb variants βW37H and αY42L eluted from the Q2 Sepharose column in a single peak around fraction 70 when monitored with visible light, as demonstrated in Fig. S2, A and B, although they are different with regard to the tetramer-dimer equilibrium (27,28). Thus, differences in shape and mass alone between dimers and tetramers do not result in separation by Q2 Sepharose. The results of UV monitoring of the same sample (Fig. S2 B) demonstrate that a small amount of E. coli nonheme proteins is also released by similar concentrations of NaCl, particularly at fractions 50 and 80, where Q2-I and Q2-II of rHb (βH92G) eluted. However, this contamination with nonheme proteins is irrelevant to the separation of Q2-II from Q2-I. Q2 Sepharose is sensitive to cations on protein surfaces, but the βH92G mutation is present only in the inner cavity of globin, so it is not expected to produce a change in the surface charge distribution between the dimers and the tetramers.

The elution patterns from an ion-exchange column depend on the retention force (electrostatic force) at the capture position in a pore, and the rate at which released proteins exit the pore. As mentioned earlier, the pore size of this Q Sepharose corresponds to a globular protein with an Mw = 4 × 106 Da. Several Hb molecules together with E. coli-derived nonheme proteins can be captured in a single pore. As a result, the loaded pores are physically crowded. When the ionic strength of the eluting solvent equals the retention force, all captured proteins are released simultaneously from the captured position and move to exit the pore. The rate of exit depends on the resistance created by crowding within the pore. If exit rates differ, they would produce different peaks in the elution pattern. It would be easier for proteins to find a pathway if their structures are rapidly changing rather than remaining rigid. The NMR spectra shown in Figs. 9 and S4 indicate the presence of appreciable differences in the conformation dynamics of rHb (αH87G) and rHb (βH92G). Therefore, we attribute the difference in their elution patterns to a difference in their exit rates from the Sepharose pores based on different levels of malleability in their protein structures.

If the absence of the Fe-His bond in the β-subunit allows large amplitude-segmental motions within the protein and induces some differences in the dynamical properties of rHb (βH92G) globins, it would be understandable that rHb (βH92G) globins would have altered flexibility. With increased flexibility, it would be easier for these proteins than for rigid Hb A to find a pathway from their captured position to the exit of a pore in a porous material. This difference in protein structural dynamics may result in a large change in the tetramer-dimer equilibrium. The absence of the Fe-His bond in the α-subunit does not yield such a change, indicating a great functional difference between the Fe-His bonds of α- and β-subunits. The occurrence of heme release is understandable when the segmental motions of globin take place more in dimers than in tetramers. Consequently, the separation of Q2-II and Q2-I peaks in Fig. 3 is attributed to a difference in flexibility between the proteins under Q2-II and Q2-I peaks.

The difference between behaviors of rHb(αH87G) and rHb(βH92G) in Q Sepharose chromatography is ascribed to the peculiar properties of rHb(βH92G). Barrick et al. (25) also noted that the sedimentation coefficient of the CO-bound form of rHb (βH92G) is 2.81, significantly smaller than 4.05 of normal value, and therefore regarded CO-rHb (βH92G) as mainly αβ-dimers. However, they did not treat it as a heterogenic sample in the analysis of spectroscopic data, although we isolated the tetramer in our previous study (8).

Effects of the Fe-His bond on the equilibrium between tetramers and dimers

As shown in Fig. 1, Hb A and rHb (βH92G) differ in the presence or absence of a covalent connection between heme and globin (protein) in the β-subunit, respectively. In a previous study (8), we demonstrated that the Fe-His bond in the β-subunits caused a decrease in the O2 affinity of the α-subunits of Hb A, and that the presence of the Fe-His bond in the β-subunits enabled Hb A to display cooperative O2 binding. Here, we propose another role for the Fe-His bond in the β-subunits of Hb A.

The absence of the Fe-His bond in the β-subunit causes a large shift in the tetramer-dimer equilibrium. Loss of the same bond in the α-subunit does not cause the same shift. The constants for dissociation of Hb A tetramers to dimers are 1 × 10−12 and 3.2 × 10−6 M for deoxy and oxy forms, respectively (33). Thus, the tetramer population dominates in both deoxy and oxy forms, even at low protein concentrations. In several naturally occurring mutants, β92His is mutated to another amino acid. These include Hb M Hyde Park (β92His → Tyr) (34,35), Hb St. Etienne (β92His → Gln) (36,37), Hb J Altgeld Gardens (β92His → Asp) (38), Hb Newcastle (β92His → Pro) (39), and Hb Mozhaisk (β92His → Arg) (40). These β92His-mutated Hbs are known to be structurally unstable. Although Hb M Hyde Park has an Fe-Tyr (O atom in Tyr) bond instead of an Fe-His bond, the other four β92His-mutant Hbs probably do not have a strong coordinating bond, such as the Fe-His bond between the heme iron and a residue of helix F.

This study shows that one effect of the β92His → Gly mutation is appreciable depletion of heme from the β-subunit in dimeric Hb. This heme depletion has also been reported in other β92His mutant Hbs (36,39,40). SemiHb, in which one kind of subunit has a heme and the other kind of subunit has no heme, also lacks the globin-heme connection. In α-semiHb [= α(Fe2+)β(apo)], α-subunits have heme and β-subunits do not. Thus, in α-semiHb, β-globin is not covalently linked with heme, as is the case for rHb (βH92G). This Hb remains dimeric irrespective of the absence or presence of IHP (41); β-semiHb [= α(apo)β(Fe2+)] behaves similarly.

Fig. S3 shows that the effect of IHP depends on whether the Fe-His bond of the β-subunit is present or absent. IHP usually promotes tetramerization of dimeric Hbs carrying mutations in the α1β2 contact region, as in Hb Hirose (26) and Hb Kansas (42,43). However, IHP is not effective at tetramerization of Hbs lacking a coordinating bond between the heme iron and HisF8 in the β-subunit, as in rHb (βH92G) and α-semiHb (41). Accordingly, dimers of rHb (βH92G) may be more stable due to the absence of the Fe-His bond in the β-subunits.

Different roles for the Fe-His bonds of the α- and β-subunits in tetrameric hemoglobin

In the 1H NMR spectra shown in Figs. 9 and S4, the behaviors of the heme methyl protons of rHb (βH92G) are different from those of rHb (αH87G). Loss of the Fe-His bond in the α-subunit of rHb (αH87G) does not influence heme orientation in normal β-subunits. In contrast, loss of the Fe-His bond in the β-subunit of rHb (βH92G) increased the percentage of reverse-oriented heme in normal α-subunits from 2% in Hb A (30), to over 30% at 308 K (20% at 298 K (29)). This suggests that the absence of Fe-His bonds in β-subunits influences heme orientation in normal α-subunits.

For heme orientation reversal to occur, a heme must leave and reenter the heme binding pocket. At the moment of the heme exit (and entrance), the mouth of the heme pocket should open. This requires the occurrence of large amplitude-segmental motions. In fact, the bandwidths of the NMR signals of rHb (βH92G) are broader than that of Hb A (Fig. 9). Although the widths of Hb A are mainly determined by the distance between heme methyl groups and the Fe3+ ion of heme, such distances remain unaltered in rHb (βH92G) and Hb A. Further broadening in rHb (βH92G) would be induced by the inhomogeneity of the magnetic field generated by protons surrounding the heme methyl groups. Large amplitude-segmental motions can underlie inhomogeneous broadening of the NMR signals of rHb (βH92G). Consistent with this hypothesis, the amount of reversed hemes increased at higher temperatures.

In contrast, in the NMR spectra of rHb (αH87G) shown in Fig. S4, the NMR signals from reversed hemes are not present. Moreover, the NMR signals assigned to the T-quaternary structure appeared at lower temperatures. This indicates the formation of α1-β2 intersubunit hydrogen bonding at lower temperatures. To enable such a phenomenon, the structure of this tetramer must remain similar to Hb A. In fact, the elution pattern from Q2 Sepharose of rHb (αH87G) in Fig. 3 is similar to that of Hb A.

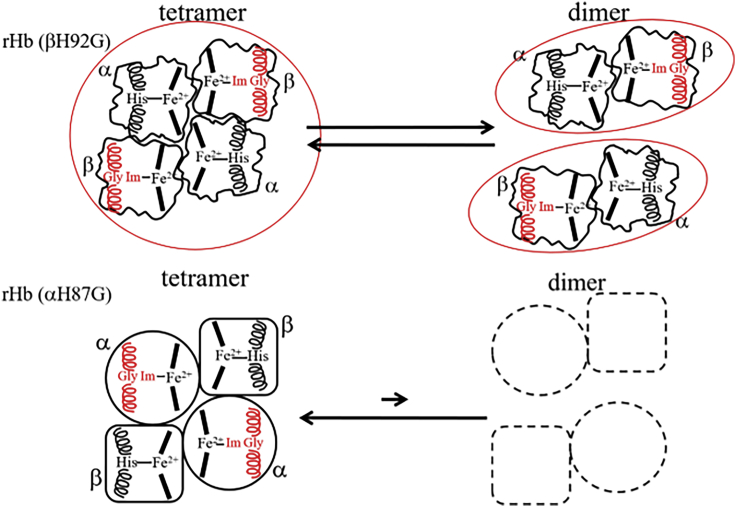

The tetramer structure of rHb (βH92G) is loose because of the occurrence of large amplitude-segmental motions. Although in both tetramer and dimer forms, intersubunit interactions in rHb (βH92G) are much weaker than in rHb (αH87G). This feature is illustrated in Fig. 10. The absence of the Fe-His bond in the β-subunit makes the entire tetrameric rHb (βH92G) hemoglobin more flexible, and the Q2 Sepharose column recognizes this malleability of protein structure in addition to the protein’s pI. As a result, the rHb (βH92G) tetramers and dimers were eluted at concentrations of NaCl different from that of Hb A. The Fe-His bond of the β-subunit alters the malleability of the whole molecule, but that of the α-subunit has no such role.

Figure 10.

Schematic illustration of the apparent tetramer-dimer equilibria of rHb (βH92G) and rHb (αH87G). Solid and broken lines denote major and minor species present, respectively. The F helices associated with Im-bound hemes in mutated globins, and His-bound hemes in native globins are represented in red and black, respectively. The globins of rHb (αH87G) adopt ordinary higher order structures similar to Hb A, but those of rHb (βH92G) adopt dynamic structures involving large amplitude-segmental motions. As a result, they dissociate more readily into dimers. The Q Sepharose column recognizes differences among the three species and separates them despite their shared pI. To see this figure in color, go online.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that rHb (αH87G) behaves similarly to HbA, but that rHb (βH92G) remains a mixture of tetramers and dimers, and an ion-exchange column (Q2 Sepharose) distinguishes slight differences in the flexibility of protein structures between tetramers (α2β2) and dimers (αβ) despite their equal pIs. The absence of Fe-His bonds in the β-subunit alters the dynamic features of the globin structure, thus shifting the dimer-tetramer equilibrium toward the dimers and allowing appreciable release of heme from the β-subunits in dimeric rHb (βH92G).

Author contributions

S.N., T.K., and M.N. conceived and designed the experiments. S.N. and M.N. performed the experiments. S.N., T.K., and M.N. analyzed the data. S.N. and M.N. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. S.N., T.K., and M.N. wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the late professor Takashi Ogura, University of Hyogo, for the use of his apparatus for RR measurements of Hb A and rHb (βH92G), and to emeritus professor Yukifumi Nagai, Fukui Medical University, for a helpful discussion on purification of recombinant hemoglobins. We thank the Japanese Red Cross Kanto-Koshinetsu Block Blood Center for the gift of concentrated erythrocytes to advance this human hemoglobin study as well as the OPEN FACILITY, Research Facility Center for Science and Technology, University of Tsukuba, for measurement of 1H NMR spectra using a Bruker AVANCE 600 FT NMR spectrometer. We thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology for Scientific Research (C) awarded to S.N. (20K03877, 17K05606), and (B) awarded to T.K. (24350086). A research grant to M.N. was supported by the Research Center for Micro-Nano Technology, Hosei University.

Editor: Wendy Shaw

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2021.05.014.

Contributor Information

Shigenori Nagatomo, Email: nagatomo@chem.tsukuba.ac.jp.

Teizo Kitagawa, Email: teizok@wb3.so-net.ne.jp.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Perutz M.F. Regulation of oxygen affinity of hemoglobin: influence of structure of the globin on the heme iron. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1979;48:327–386. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.001551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imai K. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1982. Allosteric Effects in Haemoglobin. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perutz M.F. Stereochemistry of cooperative effects in haemoglobin. Nature. 1970;228:726–739. doi: 10.1038/228726a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin J., Chothia C. Haemoglobin: the structural changes related to ligand binding and its allosteric mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 1979;129:175–220. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90277-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monod J., Wyman J., Changeux J.P. On the nature of allosteric transitions: a plausible model. J. Mol. Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koshland D.E., Jr., Némethy G., Filmer D. Comparison of experimental binding data and theoretical models in proteins containing subunits. Biochemistry. 1966;5:365–385. doi: 10.1021/bi00865a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan Y., Tam M.F., Ho C. New look at hemoglobin allostery. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:1702–1724. doi: 10.1021/cr500495x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagatomo S., Nagai Y., Nagai M. An origin of cooperative oxygen binding of human adult hemoglobin: different roles of the α and β subunits in the α2β2 tetramer. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang S., Mizuno M., Mizutani Y. Effect of the N-terminal residues on the quaternary dynamics of human adult hemoglobin. Chem. Phys. 2016;469:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esquerra R.M., Bibi B.M., Goldbeck R.A. Role of heme pocket water in allosteric regulation of ligand reactivity in human hemoglobin. Biochemistry. 2016;55:4005–4017. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagatomo S., Okumura M., Nagai M. Interrelationship among Fe-His bond strengths, oxygen affinities, and intersubunit hydrogen bonding changes upon ligand binding in the β subunit of human hemoglobin: the alkaline Bohr effect. Biochemistry. 2017;56:1261–1273. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b01118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagatomo S., Saito K., Nagai M. Heterogeneity between two α subunits of α2β2 human hemoglobin and O2 binding properties: Raman, 1H nuclear magnetic resonance, and terahertz spectra. Biochemistry. 2017;56:6125–6136. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujiwara S., Chatake T., Shibayama N. Ligation-dependent picosecond dynamics in human hemoglobin as revealed by quasielastic neutron scattering. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:8069–8077. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b05182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shibayama N., Ohki M., Park S.-Y. Direct observation of conformational population shifts in crystalline human hemoglobin. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:18258–18269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.781146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato-Tomita A., Shibayama N. Size and shape controlled crystallization of hemoglobin for advanced crystallography. Crystals (Basel) 2017;7:282. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagai M., Mizusawa N., Nagatomo S. A role of heme side-chains of human hemoglobin in its function revealed by circular dichroism and resonance Raman spectroscopy. Biophys. Rev. 2018;10:271–284. doi: 10.1007/s12551-017-0364-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang S., Mizuno M., Mizutani Y. Tertiary dynamics of human adult hemoglobin fixed in R and T quaternary structures. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018;20:3363–3372. doi: 10.1039/c7cp06287g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shibayama N. Allosteric transitions in hemoglobin revisited. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2020;1864:129335. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pezzella M., El Hage K., Karplus M. Water dynamics around proteins: T- and R-states of hemoglobin and melittin. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2020;124:6540–6554. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c04320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park S.-Y., Yokoyama T., Tame J.R.H. 1.25 A resolution crystal structures of human haemoglobin in the oxy, deoxy and carbonmonoxy forms. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;360:690–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho C. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance studies on hemoglobin: cooperative interactions and partially ligated intermediates. Adv. Protein Chem. 1992;43:153–312. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60555-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitagawa T. In: Biological Applications of Raman Spectroscopy. Spiro T.G., editor. Volume 3. Wiley; 1988. The heme protein structure and the iron histidine stretching mode; pp. 97–131. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitagawa T., Nagai K., Tsubaki M. Assignment of the Fe-Nε(His F8) stretching band in the resonance Raman spectra of deoxy myoglobin. FEBS Lett. 1979;104:376–378. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)80856-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagai K., Kitagawa T. Differences in Fe(II)-Nε(His-F8) stretching frequencies between deoxyhemoglobins in the two alternative quaternary structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:2033–2037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.4.2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrick D., Ho N.T., Ho C. Distal ligand reactivity and quaternary structure studies of proximally detached hemoglobins. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3780–3795. doi: 10.1021/bi002165q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagai M., Kaminaka S., Kitagawa T. Ultraviolet resonance Raman studies of quaternary structure of hemoglobin using a tryptophan β37 mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:1636–1642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arisaka F., Nagai Y., Nagai M. Dimer-tetramer association equilibria of human adult hemoglobin and its mutants as observed by analytical ultracentrifugation. Methods. 2011;54:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aki-Jin Y., Nagai Y., Nagai M. Changes of near-UV circular dichroism spectra of human hemoglobin upon the R → T quaternary structure transition. ACS Symp. Ser. 2007;963:297–311. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagai M., Nagai Y., Nagatomo S. Heme orientation of cavity mutant hemoglobins (His F8 → Gly) in either α or β subunits: circular dichroism, 1H NMR, and resonance Raman studies. Chirality. 2016;28:585–592. doi: 10.1002/chir.22620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto Y., La Mar G.N. 1H NMR study of dynamics and thermodynamics of heme rotational disorder in native and reconstituted hemoglobin A. Biochemistry. 1986;25:5288–5297. doi: 10.1021/bi00366a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neya S., Morishima I. Interaction of methemoglobin with inositol hexaphosphate. Presence of the T state in human adult methemoglobin in the low spin state. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:793–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjellqvist B., Hughes G.J., Hochstrasser D. The focusing positions of polypeptides in immobilized pH gradients can be predicted from their amino acid sequences. Electrophoresis. 1993;14:1023–1031. doi: 10.1002/elps.11501401163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atha D.H., Riggs A. Tetramer-dimer dissociation in homoglobin and the Bohr effect. J. Biol. Chem. 1976;251:5537–5543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayashi A., Suzuki T., Morimoto H. Some observations on the physicochemical properties of hemoglobin M-Hyde Park. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1968;125:895–901. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90528-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishikura K., Sugita Y., Yoneyama Y. Ethylisocyanide equilibria of hemoglobins M Iwate, M Boston, M Hyde Park, M Saskatoon, and M Milwaukee-I in half-ferric and fully reduced states. J. Biol. Chem. 1975;250:6679–6685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beuzard Y., Courvalin J.C.L., Gibaud A. Structural studies of hemoglobin Saint Etienne β92(F8)His → Gln: a new abnormal hemoglobin with loss of β proximal histidine and absence of heme on the β chains. FEBS Lett. 1972;27:76–80. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(72)80413-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aksoy M., Erdem S., Müftüoğlu A. Hemoglobin Istanbul: substitution of glutamine for histidine in a proximal histidine (F8(92) ) J. Clin. Invest. 1972;51:2380–2387. doi: 10.1172/JCI107050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams J.G., III, Przywara K.P., Shamsuddin M. Hemoglobin J Altgeld Gardens. A hemoglobin variant with a substitution of the proximal histidine of the β-chain. Hemoglobin. 1978;2:403–415. doi: 10.3109/03630267809007075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Finney R., Casey R., Walker W. Hb Newcastle: β92 (F8) His → Pro. FEBS Lett. 1975;60:435–438. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80766-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spivak V.A., Molchanova T.P., Tokarev Y.N. A new abnormal hemoglobin: Hb Mozhaisk beta 92(F8)His leads to Arg. Hemoglobin. 1982;6:169–181. doi: 10.3109/03630268209002292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuneshige A., Kanaori K., Yonetani T. Semihemoglobins, high oxygen affinity dimeric forms of human hemoglobin respond efficiently to allosteric effectors without forming tetramers. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:48959–48967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonaventura J., Riggs A. Hemoglobin Kansas, a human hemoglobin with a neutral amino acid substitution and an abnormal oxygen equilibrium. J. Biol. Chem. 1968;243:980–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salhany J.M., Ogawa S., Shulman R.G. Correlation between quaternary structure and ligand dissociation kinetics for fully liganded hemoglobin. Biochemistry. 1975;14:2180–2190. doi: 10.1021/bi00681a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.