Abstract

Background

Understanding vaccination intention during early vaccination rollout in Canada can help the government's efforts in vaccination education and outreach.

Method

Panel members age 18 and over from the nationally representative Angus Reid Forum were invited to complete an online survey about their experience with COVID-19, including their intention to get vaccinated. Respondents were asked “When a vaccine against the coronavirus becomes available to you, will you get vaccinated or not?” Having no intention to vaccinate was defined as choosing “No – I will not get a coronavirus vaccination” as a response. Odds ratios and predicted probabilities are reported for no vaccine intentionality in demographic groups.

Findings

14,621 panel members completed the survey. Having no intention to vaccinate against COVID-19 is relatively low overall (9%) with substantial variation among demographic groups. Being a resident of Alberta (predicted probability = 15%; OR 0.58 [95%CI 0.14-2.24]), aged 40-59 (predicted probability = 12%; OR 0.87 [0.78-0.97]), identifying as a visible minority (predicted probability = 15%; OR 0.56 [0.37-0.84]), having some college level education or lower (predicted probability = 14%) and living in households of at least five members (predicted probability = 13%; OR 0.82 [0.76-0.88]) are related to lower vaccination intention.

Interpretation

The study identifies population groups with greater and lesser intention to vaccinate in Canada. As the Canadian COVID-19 vaccination effort continues, policymakers may use this information to focus outreach, education, and other efforts on the latter groups, which also have had higher risks for contracting and dying from COVID-19.

Funding

Pfizer Global Medical, Unity Health Foundation, Canadian COVID-19 Immunity Task Force.

Keywords: COVID-19, vaccine intention

Research in Context.

Evidence before this study

Several surveys assessing national-level vaccine hesitancy or acceptance have been published in final or in pre-print form for other countries (France, England, Italy, US). Only two other studies have surveyed vaccination acceptance among the general population in Canada, but their sample sizes are small compared to the Ab-C study. Other Canadian surveys focused on specific populations, such as healthcare workers and ethnic minorities, rather than the general population. We searched PubMed, medRxiv, bioRxiv, arXiv, and medRxiv up to May 5, 2021 for preprints and peer-reviewed articles reporting on COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy or intention, using search terms, such as “vaccine hesitancy COVID,” “covid vaccine,” “covid vaccine acceptance.”

Added value

The Ab-C study is the first nationwide and reasonably representative study of SARS-CoV-2 in Canada, including intention to be vaccinated against COVID during the early phase of vaccination rollout, beginning in late 2020. The study produced estimated probabilities for having no vaccination intention by specific demographic groups. Our findings confirm that most Canadians intend to be vaccinated, with 9% of adult Canadians having no intention to vaccinate. However, vaccination intention is comparatively lower in key demographic groups, including residents of Alberta, individuals without a university degree, and visible minorities.

Implications of all the available evidence

Consistent with earlier understanding, Ab-C documents a relatively high vaccination intention in Canada. However, because children do not currently have priority for vaccination and key demographic groups with higher proportions with no intention to vaccinate tend to cluster in networks, the combination may fuel subsequent local waves . Policymakers may wish to focus their resources on vaccination campaigns targeting the most reluctant groups and to begin vaccinating children as soon as possible.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

Although the Canadian COVID-19 mortality rate is low compared to the United States and some European countries, many parts of Canada experienced a significant third wave in March-May 2021, driven by more infectious variants and lifting of public health measures [[1], [2], [3]].

Canada started vaccinating healthcare workers and nursing home residents in December 2020, and has prioritized the rest of the population by mortality risk factors (e.g., age, comorbidities), and some provinces further prioritized based on risk of disease acquisition (e.g., essential workers, living in highly impacted regions) [4,5]. Although Canada's COVID-19 vaccination efforts had a slow start with less than 4% of the population vaccinated with one dose by the end of February 2021 (compared to 15% in the United States) [6,7], two-thirds of Canadians had received at least 1 dose of a COVID-19 vaccine compared just over half in the United States by mid-June [6,7].

As a part of the ongoing Action to Beat Coronavirus (Ab-C) study [8], we report on levels and predictors of self-reported intention to vaccinate against COVID-19 and identify key groups with low intention to vaccinate at the start of the vaccine rollout in Canada. in a reasonably representative sample of Canadians.

Intentionality toward vaccination is related to, but not synonymous with, vaccine hesitancy. The World Health Organization defines vaccine hesitancy as “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine services” [9] that is influenced by complacency, convenience, and confidence [9,10], which applies in situations where vaccines are already on offer. There are other reasons for refusing or delaying vaccination (e.g., not meeting age eligibility requirements, in quarantine after natural SARS-CoV-2 infection, contraindication to the vaccine), which also affect both intentions and vaccination acceptance when available [11].

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and survey timeline

The Ab-C study is a collaboration between the University of Toronto, Unity Health Toronto, the Centre for Global Health Research, and the Angus Reid Forum (ARF) [12], an established panel of Canadian adults used for online opinion polling. The bilingual (English and French) Ab-C study started in 2020, with an initial online survey in May, including questions about COVID-19 symptoms and SARS-CoV-2 testing history. Respondents were then asked to self-collect a dried blood sample using a mailed kit so that seroprevalence during the first viral wave could be determined [[13], [14], [15]]. A second online survey, coinciding with Canada's vaccination rollout (December 2020 through February 2021) asked about COVID-19 symptoms and SARS-CoV-2 testing since the first survey, and about their intention to be vaccinated, which is the basis of this report [16]. A second dried blood sample was also requested. Ab-C participants receive no monetary compensation, but do receive modest redeemable points from the ARF.

2.2. Representativeness of the survey and sampling

44,270 members were invited to participate in the initial Ab-C survey (May to September 2020), stratified by age, sex, education, region, and census metropolitan area to match national demographic profiles. Of the 19,994 (45%) who responded, all of them were invited again in early 2021 to complete a second 20-item survey, which included a question about vaccination intention. Up to four reminder emails were sent after the initial invitation. 14,621 (73%) respondents completed the second survey.

Ab-C respondents were similar demographically to the 2016 Canadian Census profile, with some exceptions [14,17,18]. First, people 60 years and older were intentionally oversampled to capture a greater share of the population at highest risk of SARS-CoV-2 [[13], [14], [15]]. Second, panel members with higher education levels were overrepresented (23% with a Bachelor's degree or higher in Canada and 43% in the second survey sample). Hence, all subsequent analyses were adjusted for education levels to achieve the same distribution as in the Canadian census [19]. The prevalences of smoking, diabetes, and hypertension were similar to national surveys [[20], [21], [22], [23]], suggesting that the health profile of the cohort was similar to national population distributions.

2.3. Survey questions

Participants were asked “When a vaccine against the coronavirus becomes available to you, will you get vaccinated or not?” The five possible responses were: 1. “No – I will not get a coronavirus vaccination,” 2. “Not sure,” 3. “Yes – I will eventually get a vaccination, but I will wait awhile first,” 4. “Yes – I will get a vaccination as soon as one becomes available to me,” 5. “I have already been vaccinated.” In the analysis, we combined responses 4 and 5 as indicating positive intent, leaving four ordered categories. Having no vaccination intention was defined as choosing “No – I will not get a coronavirus vaccination” as a response. No questions were asked about why respondents chose their responses.

2.4. Analytical method

We calculated odd ratios (ORs) of intention to vaccinate by province, age, sex, education, visible minority, Indigenous ancestry, household size, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, and history of diabetes and hypertension using a survey weighted ordered logit model. The variables were selected to address the inherent differences in disease outcome in demographic groups (e.g., age), healthcare access (e.g., Indigenous ancestry), transmission of diseases in close quarters (e.g., household size), provincial policies, and other common factors that may affect individuals’ health (e.g., smoking status, BMI, history of diabetes and hypertension). To identify high-risk groups, we modeled predicted probabilities (prevalences) of each vaccination intention level by demographic group after obtaining the ORs. These probabilities have been adjusted for educational attainment levels by weighting.

Prior to calculating ORs, parallel line assumptions (also known as the proportional odds assumption, which assumes that the relationship between demographics and different thresholds of the outcome is proportional) [24] were tested for each demographic factor at the 0.05 level within the survey setting, and all variables met this assumption. The overall – multivariable - model also meets the parallel line assumption with an adjusted Wald test. All analyses were done in Stata 16 [25].

2.5. Ethics

The Ab-C study was approved by the IRB of Unity Health Toronto. Informed consent was obtained from all participants through an online form at the beginning of the survey, which could not proceed without consent.

Role of the funding source

The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

3. Results

Between January and March 2021, 14,621 participants out of 20,359 polled responded to the survey. The largest number of respondents were from Ontario (39.4%), followed by British Columbia and Yukon (18.9%), Quebec (15.7%), Alberta (12.6%), Manitoba and Saskatchewan (7%), and the Atlantic provinces (7%). Most participants are below age 70 (30% age 18-39, 35% age 40-59, 24% age 60-69), and 12% age 70 or above. 53% were women and 46% were men, and 34% had some (incomplete) university education and 43% were university graduates. About 14% identified as visible minorities and 9% had Indigenous ancestry. Almost half (43%) of the respondents lived with another person, while others lived alone (18%) or in a household of three (17%), four (15%) or at least five (7%). 32% and 27% had BMI classified as overweight [[25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30]] or obese (>30), respectively. 48% were former or current smokers. Almost 10% of the participants were diagnosed with diabetes and 27% had hypertension.

Among Ab-C participants, 9% had no intention to vaccinate (Table 1). Alberta (16%) and other Prairie provinces (14%) had higher proportions not intending to vaccinate compared to less than 10% in all other provinces. Participants aged 40-59 had the lowest vaccination intention, with 11.6% reporting no intention to vaccinate, compared to less than 10% in all other age groups. Men had greater proportion with no intention to vaccinate (11%) than women (8%), and those with less than college level education (e.g., associate or technical degree) or less had more respondents with no intention to vaccinate (14%) than participants with other levels of education. Other groups with lower intention to vaccinate than average included those identifying themselves as visible minority (12%), Indigenous (15%), and those living in households of five or more people (16%).

Table 1.

Unweighted survey sample characteristics (n = 14,621)

| Canada | Ab-C |

Ab-C respondents who "Will not vaccinate" by demographics |

Test of difference in vaccination intention in groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | row % | p value | |

| Total | 14,621 | 100% | 1355 | 9.3% | ||

| Province | ||||||

| Ontario | 38% | 5,766 | 39.4% | 448 | 7.8% | <0.0001 |

| British Columbia | 13% | 2,761 | 18.9% | 199 | 7.2% | |

| Quebec | 23% | 2,299 | 15.7% | 191 | 8.3% | |

| Alberta | 12% | 1,839 | 12.6% | 301 | 16.4% | |

| Manitoba & Saskatchewan | 7% | 1,027 | 7% | 142 | 13.8% | |

| Atlantic provinces | 7% | 929 | 6.4% | 74 | 8% | |

| Age groups | ||||||

| 18 to 39 years | 49% | 4,270 | 29.2% | 396 | 9.3% | <0.0001 |

| 40 to 59 years | 28% | 5,106 | 34.9% | 590 | 11.6% | |

| 60 to 69 years | 12% | 3,472 | 23.7% | 257 | 7.4% | |

| 70 years or older | 11% | 1,773 | 12.1% | 112 | 6.3% | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 49% | 6,742 | 46.1% | 736 | 10.9% | <0.0001 |

| Female | 51% | 7,777 | 53.2% | 602 | 7.7% | |

| Prefer to self-describe | 0% | 102 | 0.7% | 17 | 16.7% | |

| Education | ||||||

| Some college or lower | 45% | 3,402 | 23.3% | 468 | 13.8% | <0.0001 |

| Some university | 32% | 4,935 | 33.8% | 564 | 11.4% | |

| Bachelor or higher | 23% | 6,284 | 43% | 323 | 5.1% | |

| Visible minority | ||||||

| No | 78% | 12,526 | 85.7% | 1,098 | 8.8% | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 22% | 2,095 | 14.3% | 257 | 12.3% | |

| Indigenous ancestry | ||||||

| Not Indigenous | 95% | 13,317 | 91.1% | 1,164 | 8.7% | <0.0001 |

| Indigenous | 5% | 1,304 | 8.9% | 191 | 14.6% | |

| Household size | ||||||

| One person | 28% | 2,678 | 18.3% | 262 | 9.8% | <0.0001 |

| Two people | 34% | 6,315 | 43.2% | 501 | 7.9% | |

| Three people | 15% | 2,415 | 16.5% | 219 | 9.1% | |

| Four people | 14% | 2,163 | 14.8% | 204 | 9.4% | |

| Five or more people | 8% | 1,050 | 7.2% | 169 | 16.1% | |

| Body Mass Index | ||||||

| Under or normal weight (< 25 kg/m2) | 37% | 4,318 | 29.5% | 396 | 9.2% | 0.162 |

| Overweight (≥ 25 kg/m2 & < 30 kg/m2) | 37% | 4,716 | 32.3% | 447 | 9.5% | |

| Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) | 27% | 3,914 | 26.8% | 337 | 8.6% | |

| Unknown | 1,673 | 11.4% | 175 | 10.5% | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never | 46% | 7,310 | 50% | 632 | 8.6% | 0.016 |

| Former or current | 54% | 7,063 | 48.3% | 693 | 9.8% | |

| Unknown | 0% | 248 | 1.7% | 30 | 12.1% | |

| Diabetic | ||||||

| No | 91% | 13,064 | 89.4% | 1,222 | 9.4% | 0.122 |

| Yes | 9% | 1,424 | 9.7% | 116 | 8.1% | |

| Unknown | 0% | 133 | 0.9% | 17 | 12.8% | |

| Hypertensive | ||||||

| No | 77% | 10,419 | 71.3% | 1,026 | 9.8% | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 23% | 3,980 | 27.2% | 299 | 7.5% | |

| Unknown | 0% | 222 | 1.5% | 30 | 13.5% | |

Notes:

British Columbia includes Yukon. Manitoba & Saskatchewan include Northwest Territories.

The category "Unknown" represents non-responses in the survey.

The category "Prefer to self-describe" is a choice of sex in Angus Reid Forum's member profile.

n – unweighted counts

% - survey weighted percentages

Sources of % of characteristics at the Canadian national-level:

cHealth Reports [22]

dPublic Health Agency of Canada [23]

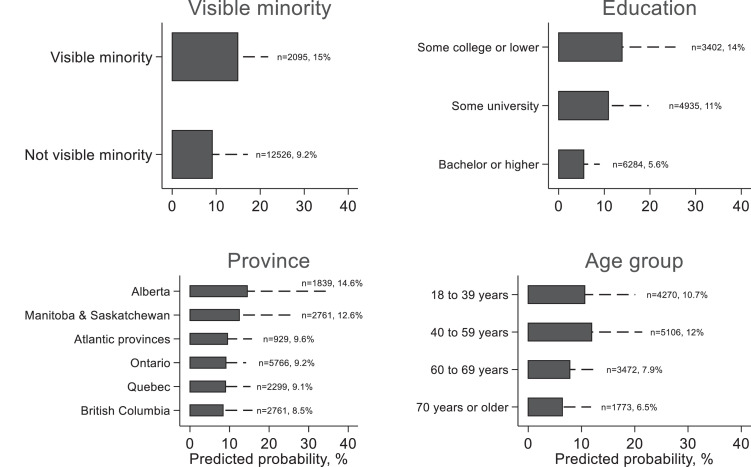

Table 2 presents participants’ weighted ORs of vaccination intention, and Table 3 represents the predicted probabilities to not vaccinate for each demographic group. Compared to the reference groups, the demographics with lower odds of intending to vaccinate included age 40-59 years (OR = 0.87, 0.78 – 0.97, predicted probability = 12%), being a visible minority (OR = 0.56, 0.37 – 0.84, predicted probability = 15%), and belonging to a household of five or more people (OR = 0.82, 0.76 – 0.88, predicted probability = 13%). Being from Alberta and having some college level education or lower also had higher predicted probability of having no intention to vaccinate at 15% and 14%, respectively. Having BMI <25 was also associated with a slightly higher probability of having no intention to vaccinate at 11%, compared to those being overweight (10%) or obese (9%). The predicted probabilities of unwillingness for key demographic groups are displayed in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Results of the weighted ordered logit for intention to vaccinate

| n | Univariate results |

Multivariate results |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted OR | Weighted 95% CI | Weighted OR | Weighted 95% CI | ||

| Province | |||||

| Ontario | 5,766 | Ref | Ref | ||

| British Columbia | 2,761 | 1.00 | (0.66, 1.53) | 1.09 | (0.67, 1.77) |

| Quebec | 2,299 | 1.04 | (0.68, 1.57) | 1.01 | (0.72, 1.43) |

| Alberta | 1,839 | 0.57 | (0.14, 2.24) | 0.58 | (0.17, 2.01) |

| Manitoba & Saskatchewan | 1,027 | 0.63 | (0.17, 2.36) | 0.70 | (0.21, 2.28) |

| Atlantic provinces | 929 | 0.93 | (0.64, 1.35) | 0.95 | (0.52, 1.74) |

| Age groups | |||||

| 18 to 39 years | 4,270 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 40 to 59 years | 5,106 | 0.85* | (0.78, 0.92) | 0.87* | (0.78, 0.97) |

| 60 to 69 years | 3,472 | 1.45* | (1.21, 1.73) | 1.41* | (1.03, 1.92) |

| 70 years or older | 1,773 | 1.94* | (1.86, 2.03) | 1.75* | (1.50, 2.04) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 6,742 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Female | 7,777 | 1.23 | (1.00, 1.51) | 1.23 | (0.97, 1.56) |

| Prefer to self-describe | 102 | 0.50 | (0.21, 1.21) | 0.76 | (0.38, 1.53) |

| Education | |||||

| Some college or lower | 3,402 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Some university | 4,935 | 1.32* | (1.10, 1.58) | 1.33* | (1.10, 1.62) |

| Bachelor or higher | 6,284 | 2.57* | (1.54, 4.29) | 2.83* | (1.96, 4.09) |

| Visible minority | |||||

| No | 12,526 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2,095 | 0.56* | (0.37, 0.84) | 0.56* | (0.37, 0.84) |

| Indigenous ancestry | |||||

| Not Indigenous | 13,317 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Indigenous | 1,304 | 0.71* | (0.54, 0.94) | 0.95 | (0.86, 1.05) |

| Household size | |||||

| One person | 2,678 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Two people | 6,315 | 1.22* | (1.14, 1.31) | 1.28* | (1.09, 1.50) |

| Three people | 2,415 | 1.01 | (0.82, 1.24) | 1.19 | (0.87, 1.62) |

| Four people | 2,163 | 0.96 | (0.79, 1.16) | 1.20 | (0.82, 1.75) |

| Five or more people | 1,050 | 0.62* | (0.49, 0.78) | 0.82* | (0.76, 0.88) |

| Body Mass Index | |||||

| Under or normal weight (< 25 kg/m2) | 4,318 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Overweight (≥ 25 kg/m2 & < 30 kg/m2) | 4,716 | 1.04 | (0.75, 1.43) | 1.11 | (0.75, 1.63) |

| Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) | 3,914 | 1.04 | (0.85, 1.26) | 1.18* | (1.05, 1.34) |

| Unknown | 1,673 | 0.79 | (0.58, 1.07) | 0.93 | (0.59, 1.48) |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never | 7,310 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Former or current | 7,063 | 0.90 | (0.77, 1.07) | 0.99 | (0.85, 1.15) |

| Unknown | 248 | 0.57* | (0.36, 0.90) | 0.83 | (0.57, 1.22) |

| Diabetic | |||||

| No | 13,064 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1,424 | 1.23* | (1.08, 1.39) | 1.11 | (0.85, 1.44) |

| Unknown | 133 | 0.45* | (0.38, 0.53) | 0.77 | (0.32, 1.85) |

| Hypertensive | |||||

| No | 10,419 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 3,980 | 1.32* | (1.25, 1.38) | 1.21* | (1.09, 1.33) |

| Unknown | 222 | 0.50* | (0.26, 0.95) | 0.72 | (0.47, 1.10) |

Notes:

British Columbia includes Yukon. Manitoba and Saskatchewan include Northwest Territories.

The category "Unknown" represents non-responses in the survey.

The category "Prefer to self-describe" is a choice of sex in Angus Reid Forum's member profile.

* p value <0.05

OR – odds ratio

95% CI – confidence interval

Table 3.

Predicted probabilities for vaccination hesitancy from multivariate ordered logit

| Will not vaccinate |

||

|---|---|---|

| Prob | SE | |

| Province | ||

| Ontario | 9.2%* | (1.2%) |

| British Columbia | 8.5%* | (1.7%) |

| Quebec | 9.1%* | (1.4%) |

| Alberta | 14.6% | (4.7%) |

| Manitoba & Saskatchewan | 12.6% | (3.1%) |

| Atlantic provinces | 9.6%* | (1.4%) |

| Age groups | ||

| 18 to 39 years | 10.7%* | (2.2%) |

| 40 to 59 years | 12%* | (2.2%) |

| 60 to 69 years | 7.9%* | (1.2%) |

| 70 years or older | 6.5%* | (1.2%) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 11%* | (2%) |

| Female | 9.1%* | (1.7%) |

| Prefer to self-describe | 13.8% | (3.7%) |

| Education | ||

| Some college or lower | 14%* | (2.7%) |

| Some university | 11%* | (2%) |

| Bachelor or higher | 5.6%* | (0.8%) |

| Visible minority | ||

| No | 9.2%* | (1.8%) |

| Yes | 15%* | (1.6%) |

| Indigenous ancestry | ||

| Not Indigenous | 10%* | (1.8%) |

| Indigenous | 10.4%* | (1.7%) |

| Household size | ||

| One person | 11.3%* | (2.4%) |

| Two people | 9.1%* | (1.7%) |

| Three people | 9.7%* | (1.5%) |

| Four people | 9.7%* | (1.3%) |

| Five or more people | 13.4%* | (2.8%) |

| Body Mass Index | ||

| Under or normal weight (< 25 kg/m2) | 10.7%* | (1.6%) |

| Overweight (≥ 25 kg/m2 & < 30 kg/m2) | 9.8%* | (2.1%) |

| Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) | 9.2%* | (1.6%) |

| Unknown | 11.3%* | (2.3%) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never | 10%* | (1.9%) |

| Former or current | 10.1%* | (1.7%) |

| Unknown | 11.7%* | (2.5%) |

| Diabetic | ||

| No | 10.1%* | (1.8%) |

| Yes | 9.2%* | (2.1%) |

| Unknown | 12.6% | (3.2%) |

| Hypertensive | ||

| No | 10.4%* | (1.8%) |

| Yes | 8.8%* | (1.8%) |

| Unknown | 13.7%* | (1.6%) |

Notes:

British Columbia includes Yukon. Manitoba & Saskatchewan include Northwest Territories.

The category "Unknown" represents non-responses in the survey.

The category "Prefer to self-describe" is a choice of sex in Angus Reid Forum's member profile.

* p value <0.05

Prob – predicted probabilities

SE – standard error

Figure 1.

Probabilities of unwillingness to vaccinate for key demographic groups among participants in the Ab-C study

4. Discussion

This study assessed intention to be vaccinated in the early phase of vaccination rollout in a nationally representative sample of Canadians, identifying differences by age, education, ethnicity, and provincial residence.

The 9% with no intention to vaccinate in our survey of Canadian adults is significantly lower than the 15-35% reported in Latin American countries (64.6% vaccination intention in Paraguay to 85% vaccination intention in Puerto Rico U.S.) in a recent cross-sectional study [26] and the 20% respondents who are unlikely to receive a COVID-19 vaccine in Canada from a population-based study that surveyed 4,948 respondents in British Columbia [27]. Our result that visible minorities are more likely not to vaccinate than others is consistent with the findings of a recent cohort study from the United States and the United Kingdom [28]. Surprisingly, a longitudinal study that examined vaccination attitudes in the United States between March and August 2020 has shown a decline in favorable attitudes, in contrast to an initial assumption that increasing experience with the vaccines would favor increasing acceptance [28]. This finding is a reminder to the public health community that although most people in Canada intend to be vaccinated at some point, 9% of people without intention to vaccinate may still impose a notable hurdle to reaching herd immunity (which potentially has a threshold of at least 70% of the population for SARS-CoV-2 if all restrictions on activities were lifted [29]), especially given that the virus and its variants are expected to become endemic [30] and that people under age 12 are still not eligible for vaccination [31].

Applying the 9% without vaccination intention to Canada as a whole, the approximately 3 million adult Canadians who might not get vaccinated could play an important role in perpetuating viral transmission. This group may interact with the approximate 5 million Canadians below age 12 [32] who are not likely to be vaccinated soon. Moreover, vaccine effectiveness in reducing infection (and perhaps reducing transmission) is about 90% for most of the vaccines available in Canada [33], which suggests that some vaccinated people may also contribute to continuing viral circulation. Within particular sub-groups, such as visible minorities, more people wishing not to vaccinate paired with greater exposure to children might lead to fueling transmission within local networks [34,35]. Thus, encouraging vaccine intention overall (and eventually vaccinating children) is important.

This study has three limitations. First, the online survey did not ask about participants’ attitudes and beliefs towards vaccination generally prior to asking them about their intention to vaccinate against COVID-19, nor did it ask the reasons for their response to the vaccination question. People who have preferences regarding vaccine types may be more willing to wait for a particular vaccine which could affect vaccination intention (36). The next phases of the Ab-C study will include questions to elicit information about the reasons for declining vaccination and to determine whether people followed through on their intentions. Second, this cross-sectional survey cannot detect changes in attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination. Third, although the oversampling of older age groups was only relevant for the initial Ab-C survey, the higher proportions of older age groups persisted in this survey. The survey weights did not adjust for the oversampling of older age groups. The limitation on sampling may affect the generalizability of the results among younger age groups, while the lack of information about attitudes and beliefs about vaccines limits the understanding about why vaccination hesitancy exists. The survey may have underestimated the proportion of the population with no intention to get vaccinated if people felt that the “socially responsible” response was to say they would take a COVID vaccine.

As the Canadian COVID-19 vaccination effort continues, policymakers may want to focus outreach, education, and other efforts on the groups identified with the lowest inclination to get vaccinated, which are also the groups with higher risks for contracting and dying from COVID-19 [36]. Influence from family physicians or Provincial Health Officers may address intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine [27]. As Canada's vaccination campaign continues, with a goal of vaccinating the majority of the population by September 2021 [4], we will periodically re-survey the Ab-C cohort and report on actual vaccination history, which will shed light on the relationship between intentionality and hesitancy.

Contributors

Conceived the idea and developed the study design: PJ. Data collection and analyses: XT, EM, TL. XT, NN, HG and PJ wrote the initial draft, and all authors were involved in commenting on subsequent revisions. PJ is the guarantor.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Data sharing

The Ab-C Data will be publicly available through the Canadian Immunity Task Force data release.

Acknowledgements

We thank the thousands of Canadians who participated in the Ab-C study, as well as all the Ab-C study investigators who contributed to the overall Ab-C study . Funding was provided by an unrestricted grant from Pfizer Global Medical Grants and from Unity Health Toronto and the Canadian COVID-19 Immunity Task Force.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.lana.2021.100055.

Appendix A. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Liu S. “Things are going to get worse”: Canada's 7-day average reaches more than 8,200 COVID-19 cases CTV News [Internet]. 2021 Apr 21 [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/things-are-going-to-get-worse-canada-s-7-day-average-reaches-more-than-8-200-covid-19-cases-1.5396978

- 2.Miller A. Canada is losing the race between vaccines and variants as the 3rd wave worsens CBC News [Internet]. 2021 Apr 8 [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/coronavirus-variants-canada-covid-19-vaccine-third-wave-1.5978394

- 3.Aziz S. Have COVID-19 variants pushed Canada into a third wave of the pandemic? Global News [Internet] 2021 https://globalnews.ca/news/7700045/ontario-third-wave-covid-19-new-variants/ Mar16 [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Government of Canada. Vaccines for COVID-19: Shipments and deliveries Canada.ca [Internet]. 2021 ND [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/prevention-risks/covid-19-vaccine-treatment/vaccine-rollout.html

- 5.Ministry of Health. COVID-19 vaccines for Ontario COVID-19 (coronavirus) in Ontario [Internet]. 2021 ND [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: https://covid-19.ontario.ca/covid-19-vaccines-ontario

- 6.Mathieu E, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Roser M, Hasell J, Appel C, et al. A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations. Nature Human Behaviour. 2021 May 10;5:947–953. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Beltekian D, Mathieu E, Macdonald B, Giattino C, et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccinations - Statistics and research - Our world in data OurWorldInData.org [Internet]. 2021. [cited 2021 Jun 17]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations

- 8.Centre for Global Health Research Angus Reid Forum Inc., Unity Health Toronto, University of Toronto. Ab-C | Action to Beat Coronavirus Abcstudy.ca [Internet] 2020 https://www.abcstudy.ca/ ND [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler R. World Health Organization; Johannesburg: 2016. Vaccine hesitancy: what it means and what we need to know in order to tackle it.https://www.who.int/immunization/research/forums_and_initiatives/1_RButler_VH_Threat_Child_Health_gvirf16.pdf [cited 2021 Jun 17]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butler R, MacDonald NE, Eskola J, Liang X, Chaudhuri M, Dube E, et al. Diagnosing the determinants of vaccine hesitancy in specific subgroups: The guide to tailoring immunization programmes (TIP) Vaccine [Internet] 2015;33(34):4176–4179. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.038. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25896376/ Aug 14 [cited 2021 Jun 17]Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaccine & Immunizations . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2021. Interim clinical considerations for use of COVID-19 vaccines | CDC [Internet]https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html ND [cited 2021 Jun 17]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angus Reid Forum Angus Reid Forum Inc. [Internet]. 2019 ND [cited 2020 Aug 24]. Available from: https://www.angusreidforum.com/en-ca/About

- 13.Action to beat coronavirus/Action pour battre le coronavirus (Ab-C) Study Investigators COVID seroprevalence, symptoms and mortality during the first wave of SARS-CoV-2 in Canada. medRxiv [Internet] 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.03.04.21252540. Mar 5 [cited 2021 Apr 27];2021.03.04.21252540. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu DC, Jha P, Lam T, Brown P, Gelband H, Nagelkerke N, et al. Predictors of self-reported symptoms and testing for COVID-19 in Canada using a nationally representative survey. PLOS ONE [Internet]. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240778. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240778 Oct 21 [cited 2021 Apr 27]Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang X, Gelband H, Lam T, Nagelkerke N, Reid A, Jha P. A national study of self-reported COVID symptoms during the first viral wave in Canada medRxiv [Internet]. 2020 Oct 5 [cited 2021 Apr 27]. p. 2020.10.02.20205930. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.02.20205930

- 16.Government of Canada. COVID-19 vaccination coverage in Canada Canada.ca [Internet]. 2021 ND [cited 2021 Jun 17]. Available from: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/vaccination-coverage/

- 17.Statistics Canada. Estimates of population (2016 Census and administrative data), by age group and sex for July 1st, Canada, provinces, territories, health regions (2018 boundaries) and peer groups Statistics Canada [Internet]. 2020 Jul 30 [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710013401

- 18.Statistics Canada. Census profile, 2016 census Statistics Canada [Internet]. 2019 Jun 18 [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

- 19.Statistics Canada. Education highlight tables, 2016 census - Highest level of educational attainment (general) by selected age groups 15 years and over, both sexes, % distribution 2016, Canada, provinces and territories, 2016 Census –25% Sample data Canada.ca [Internet]. 2017 ND [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/edu-sco/Table.cfm?Lang=E&T=11&Geo=00&SP=1&view=2&age=1&sex=1.

- 20.Statistics Canada. Smoking, 2016 Health Fact Sheets [Internet]. 2017 Sep 7 [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-625-x/2017001/article/54864-eng.htm

- 21.Statistics Canada. Overweight and obese adults, 2018 Health Fact Sheets [Internet]. 2019 Jun 25 [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/82-625-X201900100005

- 22.DeGuire J, Clarke J, Rouleau K, Roy J, Bushnik T. Blood pressure and hypertension. Health Reports [Internet]. 2019;30(2):14–21. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/82-003-X201900200002 Feb 1 [cited 2021 Apr 27]Available from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Public Health Agency of Canada. Chapter 1: Diabetes in Canada: Facts and figures from a public health perspective – Burden. Canada.ca [Internet]. 2011 https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/chronic-diseases/reports-publications/diabetes/diabetes-canada-facts-figures-a-public-health-perspective/chapter-1.html Dec 15 [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guzman-Castillo M, Brailsford S, Luke M, Smith H. A tutorial on selecting and interpreting predictive models for ordinal health-related outcomes. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology [Internet] 2015;15(3–4):223–240. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10742-015-0140-6 Dec 15 [cited 2021 Jun 21]Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 25.StataCorp . StataCorp LLC; College Station, TX: 2019. Stata statistical software: Release 16. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urrunaga-Pastor D, Bendezu-Quispe G, Herrera-Añazco P, Uyen-Cateriano A, Toro-Huamanchumo CJ, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of COVID-19 vaccine intention, perceptions and hesitancy across Latin America and the Caribbean. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease [Internet] 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102059. May 1 [cited 2021 Jun 17];41:102059. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8063600/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogilvie GS, Gordon S, Smith LW, Albert A, Racey CS, Booth A, et al. Intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine: results from a population-based survey in Canada. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2021;21(1):1017. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11098-9. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-11098-9 Dec 29 [cited 2021 Jul 18]Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen LH, Joshi AD, Drew DA, Merino J, Ma W, Lo C-H, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and uptake. medRxiv [Internet] 2021 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33655271 Feb 28 [cited 2021 Jun 17];2021.02.25.21252402. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 29.D'Souza G, Dowdy D. What is herd immunity and how can we achieve it with COVID-19? COVID-19 | School of Public Health Expert Insights [Internet]. 2021 Apr 6 [cited 2021 Jul 19]; Available from: https://www.jhsph.edu/covid-19/articles/achieving-herd-immunity-with-covid19.html

- 30.Pfeffer A. New coronavirus variant could dominate in Ontario by next month, model shows CBC News [Internet]. 2021 Jan 9 [cited 2021 Jun 17]. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/uk-variant-dominant-strain-ontario-february-1.5866296

- 31.Government of Canada. Vaccines for COVID-19 - Canada.ca [Internet]. 2021 ND [cited 2021 Apr 28]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/vaccines.html

- 32.Statistics Canada. Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex Statistics Canada [Internet]. 2020 Sep 29 [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000501

- 33.Olliaro P, Torreele E, Vaillant M. COVID-19 vaccine efficacy and effectiveness—the elephant (not) in the room. The Lancet Microbe [Internet]. 2021 Apr 20 [cited 2021 Apr 27];0 (0). Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2666524721000690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Bilal U, Tabb LP, Barber S, Roux A v Diez. Spatial Inequities in COVID-19 testing, positivity, confirmed cases, and mortality in 3 U.S. cities. Annals of Internal Medicine [Internet] 2021 doi: 10.7326/M20-3936. https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M20-3936 Mar 30 [cited 2021 Apr 27];M20-3936. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong B, Bonczak BJ, Gupta A, Thorpe LE, Kontokosta CE. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America [Internet] 2021. Exposure density and neighborhood disparities in COVID-19 infection risk.https://www.pnas.org/content/118/13/e2021258118 Mar 30 [cited 2021 Apr 27];118 (13). Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Statistics Canada Delivering insights through data for a better Canada COVID-19 in Canada: A one-year update on social and economic impacts. Catalogue no. 11-631-x2021001. [Internet] 2021 www.statcan.gc.ca Mar 11 [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.