Abstract

Background

People who inject drugs (PWID) living with HIV experience inadequate access to antiretroviral treatment (ART) and medication for opioid use disorders (MOUD). HPTN 074 showed that an integrated intervention increased ART use and viral suppression over 52 weeks. To examine durability of ART, MOUD, and HIV viral suppression, participants could re-enroll for an extended follow-up period, during which standard-of-care (SOC) participants in need of support were offered the intervention.

Methods

Participants were recruited from Ukraine, Indonesia and Vietnam and randomly allocated 3:1 to SOC or intervention. Eligibility criteria included: HIV-positive; active injection drug use; 18-60 years of age; ≥1 HIV-uninfected injection partner; and viral load ≥1,000 copies/mL. Re-enrollment was offered to all available intervention and SOC arm participants, and SOC participants in need of support (off-ART or off-MOUD) were offered the intervention.

Results

The intervention continuation group re-enrolled 89 participants, and from week 52 to 104, viral suppression (<40 copies/mL) declined from 41% to 29% (estimated 9.4% decrease per year, 95% CI -17.0%; -1.8%). The in need of support group re-enrolled 94 participants and had increased ART (re-enrollment: 55%, week 26: 69%) and MOUD (re-enrollment: 16%, week 26: 25%) use, and viral suppression (re-enrollment: 40%, week 26: 49%).

Conclusions

Viral suppression declined in year 2 for those who initially received the HPTN 074 intervention and improved maintenance support is warranted. Viral suppression and MOUD increased among in need participants who received intervention during the study extension. Continued efforts are needed for widespread implementation of this scalable, integrated intervention.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, HIV infection, injection drug use, methadone/therapeutic use, viral load

HPTN 074 was an intervention for HIV and opioid use disorder treatment among people who inject drugs living with HIV. In the study extension, viral suppression declined for initial intervention group, yet viral suppression improved for those new to intervention.

High incidence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections is concentrated among people who inject drugs (PWID) in many locations globally, including Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and parts of Southeast Asia [1–3]. Injection practices, such as serial use and sharing of drug preparation and injection equipment, magnify risks for acquiring and transmitting HIV within injection networks [4, 5]. Injection networks can facilitate ongoing HIV transmission as they typically involve multiple injection partners, varied injection practices, and condomless sex [6–10]. Furthermore, PWID have limited access to HIV care and medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) due, in part, to persistent stigma and punitive legal systems [11–13].

The HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 074 study was a randomized, controlled vanguard study that took place among PWID in Kyiv, Ukraine; Thai Nguyen, Vietnam; and Jakarta, Indonesia [14]. The trial enrolled PWID living with HIV (index participants) and randomized index-partner groups to either in-country standard of care (SOC) or a flexible integrated intervention that included supported referral for antiretroviral therapy (ART) and MOUD. The intervention was grounded in maintenance theory and social cognitive and diffusion of innovation meta-theories of behavior change [15]. At 52 weeks of follow-up, index participants receiving the intervention were substantially more likely to self-report increased ART and participation in MOUD and were significantly more likely to achieve HIV viral suppression [14].

Index participants were invited to reenroll for an up to 52-week study extension designed to assess longer-term treatment-effect durability. Due to the effect of the invention in the primary trial, SOC arm participants who were in need of support were offered the flexible, integrated systems navigation and psychosocial counseling intervention and were followed for 26 weeks. Index participants who at the time of trial completion remained out of care for HIV and substance use treatment represent a critical population needing a tailored intervention to overcome unique risk structures impeding care and treatment [16]. Evidence on the durability and replication of a flexible intervention will directly inform widespread implementation of this intervention in other populations of PWID globally.

Here we report results from this nonrandomized extension to the trial, including the durability of the integrated intervention on ART use, MOUD use, and viral suppression. We also report intervention uptake and outcomes among those who, at the time of the primary trial completion, remained out of care and were offered the integrated intervention.

METHODS

Study Setting and Population

HPTN 074 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02935296) was conducted in 3 locations: Kyiv, Ukraine; Thai Nguyen, Vietnam; and Jakarta, Indonesia. Study site selection for HPTN 074 was based on ongoing HIV epidemics among PWID with high HIV prevalence or incidence and MOUD availability at the time of study conception [16]. All participants who were HIV infected at the original trial enrollment (“indexes”) were eligible to reenroll in the extension.

HPTN 074 Trial Design and Procedures

The HPTN 074 study design was described previously [14]. In brief, participants were randomly allocated 3:1 to SOC vs intervention. Eligibility criteria included HIV infection at screening according to local HIV test procedures; active injection drug use; 18–60 years of age; ≥1 HIV-uninfected injection partner; viral load ≥1000 copies/mL (based on local testing); no plan to move from the study region for at least 1 year following enrollment; ability and willingness to provide informed consent; and willingness to participate in randomly allocated intervention activities. People with the appearance of psychological disturbance or cognitive impairment that would restrict their ability to understand study procedures, or with any other condition that would make participation unsafe, were excluded per protocol criteria and as determined by a study investigator. Despite the potential for coinfection with hepatitis C virus among the study population, the focus of this study and intervention activities was for PWID living with HIV needing HIV and MOUD treatment. Therefore, participants were eligible regardless of their hepatitis C virus status.

In addition to a standard harm reduction package in line with in-country guidelines and the World Health Organization package of care for PWID [1, 17], participants in the integrated intervention received (1) systems navigation to facilitate engagement, retention, and adherence in HIV care and MOUD and to negotiate the logistics and, if necessary, cost of any required laboratory testing (eg, tuberculosis testing) and transportation; (2) psychosocial counseling using motivational interviewing, problem solving, skills building, and goal setting to facilitate initiation of ART and MOUD, and if started, medication adherence; (3) and ART initiation regardless of CD4 cell count, guaranteed by each Ministry of Health at study onset [14, 15]. At a minimum, systems navigators met with participants twice either in-person or by telephone. Based on the needs of the participant, successive sessions were conducted in-person, by telephone, or with text messages. Participants also received at least 2 psychosocial counseling sessions and were offered additional booster sessions, approximately 1 month and 3 months after enrollment.

Study Extension Procedures

Participants randomly allocated to the intervention arm at trial baseline continued to receive systems navigation and psychosocial counseling as needed during the extension follow-up. In need of support (off-ART or off-MOUD) participants from the trial SOC arm were offered the integrated intervention in the extension period provided they (1) did not report both current ART and MOUD use at the last primary study visit or (2) were identified by site staff as not being on ART or MOUD, or in need of support for ART or MOUD treatment, at the time of extension reenrollment. The integrated intervention was offered in the same format used during the trial period. SOC arm participants who reported current ART and MOUD use continued in care per national guidelines and were not offered the intervention package (continuation in SOC group). Similar to the study initiation, methadone was the predominate MOUD available during the extension period. Buprenorphine was available on a very limited basis in Ukraine and Indonesia but unavailable in Vietnam.

Data Collection

Primary data collection, as described elsewhere [14], consisted of interviews at screening, enrollment, 1 month postenrollment, and quarterly until the exit visit. Primary trial follow-up of HIV-infected participants lasted 12–24 months and follow-up duration varied by enrollment date. The full extension period consisted of a reenrollment visit and at least 2 extension quarterly visits, with extension reenrollment occurring as soon as feasible following completion of the primary study. The trial closed to follow-up on 30 June 2017. Reenrollment was permitted at any time during the extension period from 24 August 2017 to 30 June 2018.

Generally, extension procedures were the same as described in the trial. Blood and urine samples were collected at each visit and stored. Throughout, viral load testing was completed retrospectively at the HPTN Laboratory Center (Baltimore, Maryland). Self-reported ART and MOUD use was collected by study staff who were trained to interview participants using nonjudgmental techniques.

Statistical Analyses

The primary measures of interest were remaining alive with current ART, MOUD, and viral suppression. ART and MOUD were measured based on self-report, and viral suppression was assessed via laboratory testing at 2 thresholds: <40 copies/mL and <1000 copies/mL.

ART, MOUD, and viral suppression outcome durability in the intervention continuation group was estimated over weeks 52 to 104 from enrollment in the primary trial (ie, year 2) using longitudinal linear-binomial models, pooled over the 3 sites, with year calculated as (study week – 52) ÷ 52. Longitudinal models used an exchangeable working correlation structure. Deceased participants were considered to be not on ART, not on MOUD, and not virally suppressed. Outcomes for the in need of support group who received the intervention during the extension were assessed at 26 weeks from reenrollment. Two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used with no adjustment for multiple testing; the prespecified statistical significance level was .05. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS/STAT 14.2, Cary, North Carolina) and R version 3.5.3.

Patient Consent Statement

The study protocol was approved by the following institutional review boards: Ukrainian Institute on Public Health Policy (Ukraine); Ethical Review Board for Biomedical Research Hanoi School of Public Health (Vietnam); Ethics Committee of Faculty of Medicine, University of Indonesia/Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital (Indonesia); and the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board. All study participants provided written informed consent in their local languages, or English, if preferred. Each index was informed that his/her recruited HIV-uninfected partner(s) would become aware of the index’s HIV infection during the consent process.

RESULTS

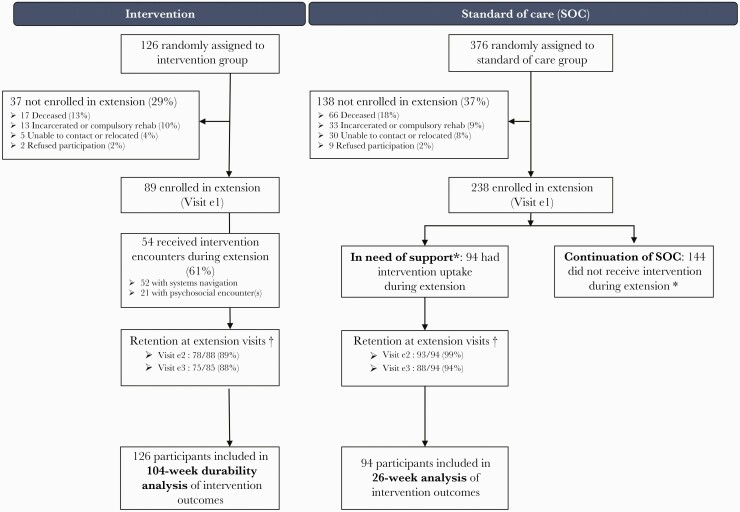

Overall, 502 HIV-infected PWID were enrolled and eligible in HPTN 074 (Figure 1), with 194 in Vietnam (39%), 187 in Ukraine (37%), and 121 in Indonesia (24%). Participants were randomly assigned to the SOC arm (376/502 [75%]) or intervention arm (126/502 [25%]). The HPTN 074 study extension ran from 4 September 2017 to 7 July 2018. A total of 327 participants (65%) consented and were reenrolled, including 89 indexes in the intervention continuation group, 94 indexes in the in need of support group, and 144 continuation in the SOC group. Among those in the intervention continuation group, 89% and 88% completed extension visits at weeks 13 and 26, respectively. Among the in need of support group, 99% completed extension visit at week 13, and 94% completed extension visit at week 26.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram. Enrollment and reenrollment participation, with primary trial intervention group on left and standard of care (SOC) group on right. *Participants originally randomized to SOC were recommended to receive intervention during the extension if they reported being off antiretroviral therapy and/or off medication for opioid use disorder at their last main study follow-up before the extension, or by site personnel discretion during the extension. †Retention denominator excludes participants who were deceased and nonrequired visits where the study closed before the participant’s targeted visit date. The denominator includes participants who missed the visit or exited study prematurely due to incarceration or compulsory rehabilitation, refusal to participate, unable to contact, or participant relocation. Extension visit e1 was the time of enrollment in the extension. Visit e1 is the extension enrollment. Visit e2 is extension week 13. Visit e3 is extension week 26.

Baseline demographics were comparable across those who reenrolled and did not reenroll (Table 1). The majority of those who reenrolled from the intervention group and in need of support group were male, aged 30–39, and unemployed in the past 3 months at baseline for the primary trial enrollment.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics at the Time of Primary Trial Enrollment (N = 502)

| Characteristic | Overall | Intervention Reenrolled | Intervention Not Reenrolled | SOC Reenrolled | SOC Not Reenrolled | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 502) | (n = 89) | (n = 37) | (n = 238) | (n = 138) | ||||||

| Self-identified gender | ||||||||||

| Female | 75 | (15) | 13 | (15) | 3 | (8) | 47 | (20) | 12 | (9) |

| Male | 427 | (85) | 76 | (85) | 34 | (92) | 191 | (80) | 126 | (91) |

| Age, y | ||||||||||

| 18–19 | 1 | (<1) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (<1) |

| 20–29 | 81 | (16) | 12 | (13) | 9 | (24) | 37 | (16) | 23 | (17) |

| 30–39 | 328 | (65) | 60 | (67) | 25 | (68) | 159 | (67) | 84 | (61) |

| ≥40 | 92 | (18) | 17 | (19) | 3 | (8) | 42 | (18) | 30 | (22) |

| Highest education level | ||||||||||

| No schooling | 4 | (<1) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (3) | 1 | (<1) | 2 | (1) |

| At least some primary school | 55 | (11) | 6 | (7) | 6 | (16) | 20 | (8) | 23 | (17) |

| At least some secondary school | 256 | (51) | 41 | (46) | 20 | (54) | 120 | (50) | 75 | (54) |

| At least some technical training | 122 | (24) | 27 | (30) | 6 | (16) | 67 | (28) | 22 | (16) |

| At least some college or university | 65 | (13) | 15 | (17) | 4 | (11) | 30 | (13) | 16 | (12) |

| Relationship status | ||||||||||

| Married | 171 | (34) | 35 | (39) | 10 | (27) | 75 | (32) | 51 | (37) |

| Living with sexual partner, not married | 75 | (15) | 14 | (16) | 3 | (8) | 44 | (18) | 14 | (10) |

| Separated, divorced, widowed | 104 | (21) | 16 | (18) | 8 | (22) | 43 | (18) | 37 | (27) |

| Single | 152 | (30) | 24 | (27) | 16 | (43) | 76 | (32) | 36 | (26) |

| Unemployed (within past 3 mo) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 305 | (61) | 56 | (63) | 22 | (59) | 145 | (61) | 82 | (59) |

| No | 197 | (39) | 33 | (37) | 15 | (41) | 93 | (39) | 56 | (41) |

| Employment statusa | ||||||||||

| Employed full-time | 149 | (30) | 22 | (25) | 14 | (38) | 67 | (28) | 46 | (33) |

| Employed part-time | 134 | (27) | 25 | (28) | 9 | (24) | 58 | (24) | 42 | (30) |

| Unemployed, seeking work | 152 | (30) | 30 | (34) | 10 | (27) | 75 | (32) | 37 | (27) |

| Unemployed, not seeking work | 63 | (13) | 10 | (11) | 4 | (11) | 37 | (16) | 12 | (9) |

| Retired | 3 | (<1) | 1 | (1) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (<1) | 1 | (<1) |

| ART status (self-reported) | ||||||||||

| Currently on ART | 54 | (11) | 10 | (11) | 5 | (14) | 24 | (10) | 15 | (11) |

| Previously on ART | 46 | (9) | 8 | (9) | 1 | (3) | 27 | (11) | 10 | (7) |

| ART naive | 402 | (80) | 71 | (80) | 31 | (84) | 187 | (79) | 113 | (82) |

| On MOUD (self-reported) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 109 | (22) | 20 | (22) | 8 | (22) | 55 | (23) | 26 | (19) |

| No | 393 | (78) | 69 | (78) | 29 | (78) | 183 | (77) | 112 | (81) |

| Time since HIV diagnosis, y, median (IQR) | 1.4 | (0.07–6.4) | 3.0 | (0.13–8.5) | 0.10 | (0.06–5.5) | 1.1 | (0.06–5.9) | 0.60 | (0.08–5.9) |

| HIV-1 RNA, log10 copies/mL, median (IQR) | 4.6 | (4.0–5.0) | 4.6 | (3.9–4.9) | 4.8 | (4.4–5.0) | 4.5 | (3.9–4.9) | 4.7 | (4.1–5.1) |

| CD4 count, cells/μL, median (IQR) | 293 | (166–463) | 321 | (211–507) | 256 | (139–451) | 311 | (178–477) | 269 | (143–406) |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; MOUD, medication for opioid use disorder; SOC, standard of care.

aOne participant refused to answer (intervention reenrolled arm)

At reenrollment, 75% of those in the intervention continuation group reported currently being on ART and 43% reported being on MOUD (Table 2). The median duration of time since diagnosis was 5.0 years (interquartile range [IQR], 2.3–10.4 years). 43% were virally suppressed with <40 copies/mL. Among those in need of support group, 45% reported being ART naive or previously on ART, and 84% reported not being on MOUD. The median duration of time since diagnosis was 2.4 years (IQR, 2.0–6.4 years), and 60% were not virally suppressed with ≥40 copies/mL.

Table 2.

Antiretroviral Therapy, Medication for Opioid Use Disorder, Time Since HIV Diagnosis, and Viral Load at the Time of Study Extension Reenrollment

| Characteristic | Intervention Arm Reenrolled (Continuation) | SOC Arm Reenrolled and Started on Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 89) | (n = 94) | |||

| ART status (self-report) | ||||

| Currently on ART | 67 | (75) | 52 | (55) |

| Previously on ART | 17 | (19) | 13 | (14) |

| ART naive | 5 | (6) | 29 | (31) |

| Currently on MOUD (self-reported) | ||||

| Yes | 38 | (43) | 15 | (16) |

| No | 51 | (57) | 79 | (84) |

| Time since HIV diagnosis, y, median (IQR) | 5.0 | (2.3–10.4) | 2.4 | (2.0–6.4) |

| HIV-1 RNA | ||||

| Below 40 copies/mL | 38 | (43) | 38 | (40) |

| 40 to <1000 copies/mL | 8 | (9) | 9 | (10) |

| ≥1000 copies/mL | 43 | (48) | 47 | (50) |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; MOUD, medication for opioid use disorder; SOC, standard of care.

Intervention Continuation Group

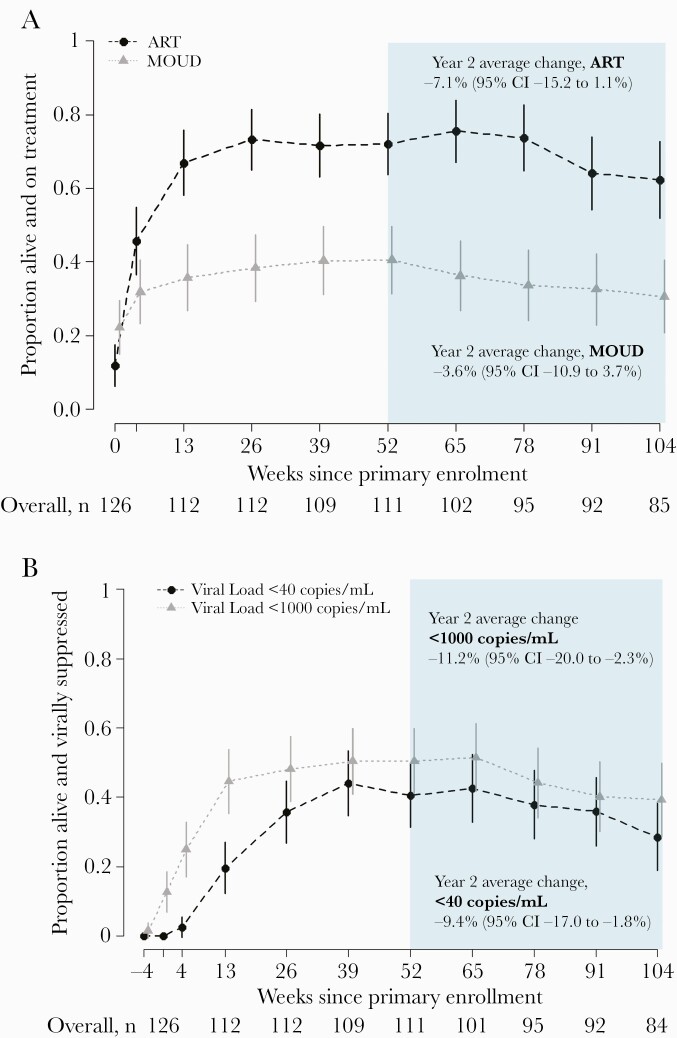

At week 52, 72% (80/111) were alive and reported being on ART, while 62% (53/85) were alive and reported being on ART at week 104. From week 52 to 104, the probability of ART among those alive decreased by an estimated 7.1% (95% CI, –15.2% to 1.1%) (Figure 2A). Similarly, MOUD decreased by an estimated 3.6% (95% CI, –10.9% to 3.7%) with 41% (45/111) alive and reporting MOUD at week 52 and 31% (26/85) on MOUD at week 104. From week 52 to 104, probability of viral suppression <40 copies/mL declined from 41% (45/111) to 29% (24/84) with an estimated 9.4% decrease per year (95% CI, –17.0% to –1.8%) (Figure 2B). Viral suppression also decreased over year 2 using the alternative threshold of <1000 copies/mL.

Figure 2.

Proportion of intervention continuation participants on treatment (A) and virally suppressed (B) by study week (n = 126). Weeks since primary study enrollment is displayed on the x-axis, with year 2 of follow-up in the shaded region. The proportion of participants who were alive and on treatment is shown on the y-axis with a corresponding 95% confidence interval at each follow-up. Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval; MOUD, medication for opioid use disorder.

In Need of Support Group

Approximately 81% (76/94) of the participants in the in need of support group completed their first systems navigator encounter, which occurred a median of 110 days (IQR, 84–184 days) after reenrollment. Nearly all (93%) of the encounters occurred in person with the majority lasting 15 minutes or less (84%) and focusing on HIV care (53%) or ART management (24%). The median time to completing the first psychosocial counseling session was 87 days (IQR, 65–159 days). Half of the first sessions lasted 16–30 minutes, while 43% lasted more than 30 minutes. During follow-up, the median number of completed psychosocial sessions was 3 (IQR, 2–4).

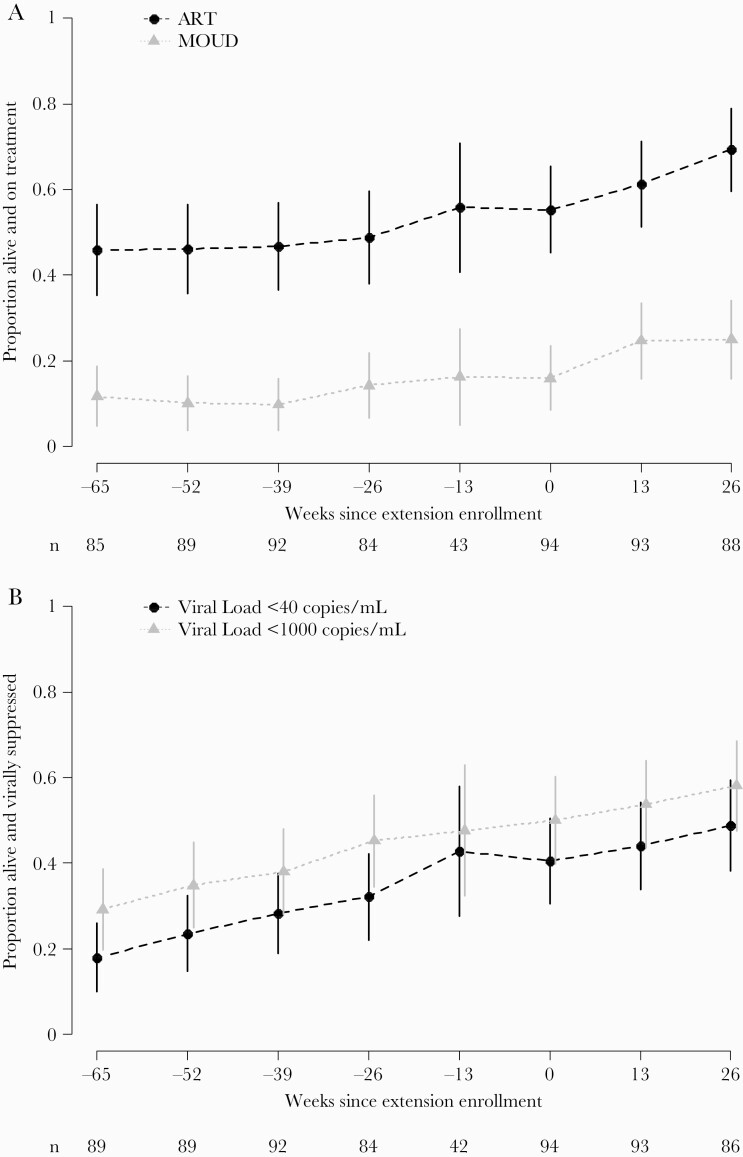

Overall, the proportion of participants in need of support who were alive and reported being on ART increased over time, from 55% (52/94) at reenrollment to 69% (61/88) at week 26 (Figure 3A). Reported MOUD also increased among participants in need of support. At reenrollment, 16% (15/94) were alive and reported MOUD, and at week 26, 25% (22/88) reported MOUD. At reenrollment, 40% (38/94) were alive and virally suppressed (<40 copies/mL) (Figure 3B). At 26 weeks, 49% (42/86) were alive and virally suppressed. Viral suppression also increased over time using the alternative threshold of <1000 copies/mL.

Figure 3.

Proportion of in need of support participants on treatment (A) and virally suppressed (B) by study week (n = 94). Standard of care (SOC) randomization arm participants who enrolled in the extension and received the intervention during the extension. Weeks since extension enrollment is displayed on the x-axis, and week –65 to week –13 outcomes occurred during the primary SOC study period before the extension. The proportion of participants who were alive and on treatment is shown on the y-axis with a corresponding 95% confidence interval at each follow-up. By definition, participants were alive at the time of their extension enrollment (week 0) and typically, these participants were off antiretroviral therapy (ART) or off medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) at extension enrollment. The sample size at the visit prior to the extension (–13 weeks) reflects the time gap between the end of the primary study and the opening of extension enrollment.

DISCUSSION

HPTN 074 was a flexible integrated intervention that included supported referral for ART and substance use treatment for PWID living with HIV. The primary purpose of this extension was to evaluate the durability of the intervention on ART and MOUD continuation and HIV viral suppression. As part of the extension, those who continued from the randomized intervention arm had declining ART and MOUD use, as well as viral suppression over the second year of follow-up. PWID in need of support for ART or MOUD treatment who subsequently received the intervention during extension reported uptake in ART and MOUD, as well as increasing proportions achieving viral suppression over time. This suggests that the flexible integrated intervention can be reproduced, leading to improved PWID health outcomes.

Additional support may be critical for PWID to maintain, and potentially continuously increase, ART and MOUD use and viral suppression. The intervention was designed for scalability to provide immediate systems navigation and psychosocial counseling support for PWID [15]. Booster sessions were offered within 1 month and 3 months after the initial session. Referrals were provided for PWID in need of additional counseling. There were no substantial changes in policy regarding access to ART or MOUD in any of the 3 countries between the initiation of the study and the end of the extension period. Participants also spent time out-of-study between the primary trial and extension period; therefore, they may not have been receiving maintenance support for ART and MOUD due to sustained structural barriers to care [18].

PWID face numerous barriers to HIV care and substance treatment at multiple levels, and barriers may change over time [18]. Delayed supplemental systems navigation boosters may help address newly developed barriers to HIV care and substance use treatment. Likewise, psychosocial counseling boosters may be warranted to leverage motivational interviewing, problem solving, skills building, and goal setting for maintaining ART and MOUD long-term. Further emphasis on MOUD uptake and maintenance may also be critical for improving ART use over time for PWID.

In addition to systems navigation and flexible counseling, developmental modalities of ART, such as long-acting injectables (LAIs), could play a complementary role in sustaining viral suppression for PWID. Phase 2 and 3 trials for monthly and every 2 months LAI ART have been completed and show efficacy for the management of HIV [19, 20]. PWID could benefit from LAI ART by overcoming treatment fatigue and stigma from daily medication and facilitating confidentiality by receiving injections within a clinical site rather than daily medication at home [11, 21]. Indeed, studies, such as AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5359 (the LATITUDE study), are underway to evaluate the use of LAI ART people who face adherence barriers, including PWID [22]. Acceptability and potential uptake of LAI ART for PWID should be further explored, particularly to provide insights into implementation challenges as LAI ART becomes available.

HIV drug resistance may have impacted the ability of ART to suppress viral replication among participants in HPTN 074. As previously reported, approximately 10% of PWID living with HIV at baseline in HPTN 074 had HIV drug resistance and were less likely to be virally suppressed at 52 weeks of follow-up, regardless of study arm [23]. HIV care for study participants was provided at local care centers where routine drug resistance testing is unavailable. It is likely that despite reported ART use, ART failure may have resulted in suboptimal viral suppression among our study population [11, 24]. The prevalence of drug resistance among PWID in our sample is likely higher than the general PWID population as PWID who were unsuccessful on ART were specifically recruited. Nonetheless, programs are needed for maintenance support for enhanced HIV care among PWID living with HIV.

Our integrated intervention directly linked PWID in need of support, who were unable to benefit from in-country standard of care, to HIV and substance use treatment. PWID in need of support had increases in self-reported ART and MOUD over time, as well as viral suppression. In the primary trial, HPTN 074 provided direct evidence of improved ART use, MOUD, and viral suppression; 36% of PWID receiving the intervention were alive and virally suppressed at week 26, compared to 49% of PWID receiving the intervention in the extension period [14]. Our tailored integrated intervention was again able to overcome the unique risk structures hindering care and treatment for this critical population [16].

Increases in reported MOUD use were rapid, though still suboptimal, for PWID in need of support. Our integrated intervention was designed to enhance ART and MOUD uptake with ART initiation and adherence as the main priority [15]. The intervention sessions did include supplementary materials on substance use treatment, harm reduction, and MOUD initiation. The immediate uptake of MOUD within our sample is encouraging as PWID in these regions face a myriad of barriers to MOUD access [25, 26]. MOUD programs in Indonesia, Ukraine, and Vietnam are insufficient, with limited treatment slots, complicated admission requirements, and considerable travel distances to clinics [18]. Structural interventions, in addition to individually tailored approaches, may ease access barriers to MOUD and should also be explored. A flexible integrated intervention uniquely tailored to address barriers to both HIV and substance use treatment may further increase and sustain MOUD use among PWID, despite ongoing structural treatment challenges.

ART and MOUD use were self-reported by PWID participants. While trial staff were extensively trained on nonjudgmental techniques to reduce the potential for social desirable responses, the intervention was designed to improve ART and MOUD initiation and adherence [14, 15]. Participants may have overstated their ART and MOUD use, but the validity of these self-reported results are bolstered by participants’ viral load measurements.

This study is limited by its nonexperimental design. Continuing the primary experimental design would have provided estimates one the long-term effects of the HPTN 074 intervention. However, the primary trial demonstrated significant benefits for PWID living with HIV. The intervention efficacy from the primary trial provided an opportunity to offer all participants access to the intervention and provide insights for future widespread implementation.

In conclusion, the HPTN 074 extension showed waning durability of the intervention effects during the second year following enrollment in the primary trial, suggesting that PWID living with HIV need maintenance support with an emphasis on MOUD uptake and incorporating routine drug resistance testing, as an approach for sustaining viral suppression. Nonetheless, the HPTN 074 flexible integrated intervention can be reproduced and delivered to PWID in need of support for HIV and MOUD across a variety of limited-resource settings. PWID who needed support and were out of HIV or substance use treatment benefited from the intervention, resulting in MOUD uptake and increases in ART use and viral suppression. Continued efforts are needed for widespread implementation of this scalable, integrated intervention for PWID globally.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We would like to thank Dr Myron Cohen for his assistance in the earliest stages of this study, including its conceptualization and securing HPTN funding; Dr Wafaa El-Sadr for her support throughout the study; Katherine Davenny for her advocacy and assistance in the entire study process; and Laura McKinstry, Ilana Trumble, and Amber Guo for their contributions to data management and analysis. We appreciate the critical role of FHI 360 in study implementation and Bonnie Dye and Jonathan Lucas, in particular. We thank Teerada Sripaipan for her support throughout the study. We also acknowledge Dr Bui Duc Duong of the Vietnam Administration of HIV/AIDS Control and Dr Nguyen Duc Vuong, Director of Pho Yen Health Center, for his role in implementing the study in Vietnam. Finally, we wish to thank all of the HPTN Protocol Team, the site staff in Indonesia, Vietnam, and Ukraine for their dedication to the study, and the participants for their willingness to share their experiences through the study.

Author contributions. C. A. L., D. S. M., W. C. M., and I. F. H. conceived the study. K. E. L., K. R. M., B. S. H., S. M. R., C. A. L., D. S. M., V. F. G., M. G. H., S. H. E., D. N. B., W. C. M., and I. F. H. assisted with study design. K. E. L., B. S. H., T. V. H., K. D., Z. D., S. M. R., C. A. L., D. S. M., V. F. G., S. Dv., E. M. P.-M., P. R., M. G. H., E. L. H., S. H. E., H. S., V. A. C., S. Dj., B. D. D., T. K., D. N. B., W. C. M., and I. F. H. developed the protocol and assisted with study implementation or oversight. K. E. L., C. A. L., D. S. M., V. F. G., and T. K. developed the intervention. K. R. M., B. S. H., B. S.-S., S. A. R., and M. G. H. conducted data analyses. K. E. L., K. R. M., B. S. H., B. S.-S., and I. F. H. drafted the manuscript. All authors edited, reviewed, and approved the final manuscript.

Disclaimer. The funder of this study reviewed and approved the protocol and protocol revisions. The sponsor participated in study design and reviewed the final report but had no role in data collection or data analysis. The corresponding author had access to all study data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the NIH (award numbers UM1AI068619 [HPTN Leadership and Operations Center], UM1AI068617 [HPTN Statistical and Data Management Center], and UM1AI068613 [HPTN Laboratory Center]) and by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI50410).

Potential conflicts of interest. This study was supported by the NIH, from which multiple investigators have received grants or support (K. E. L., K. R. M., B. S. H., T. V. H., C. A. L., D. S. M., V. F. G., S. A. R., E. M. P.-M., P. R., M. G. H., S. H. E., W. C. M., I. F. H.). D. N. B. is an employee of NIH. K. R. M. has received grants from Merck, Gilead, and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics; S. H. E. has received support from Abbott Diagnostics/Molecular; all of these activities were outside the scope of the current work. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Beyrer C, Malinowska-Sempruch K, Kamarulzaman A, et al. . Time to act: a call for comprehensive responses to HIV in people who use drugs. Lancet 2010; 376:551–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeHovitz J, Uuskula A, El-Bassel N. The HIV epidemic in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2014; 11:168–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Stanaway J, et al. . Estimating the burden of disease attributable to injecting drug use as a risk factor for HIV, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B: findings from the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:1385–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stimson G.Drug injecting and HIV infection. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booth RE, Kwiatkowski CF, Brewster JT, et al. . Predictors of HIV sero-status among drug injectors at three Ukraine sites. AIDS 2006; 20:2217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latkin C, Mandell W, Vlahov D, et al. . People and places: behavioral settings and personal network characteristics as correlates of needle sharing. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Human Retrovirol 1996; 13:273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latkin CA, Sherman S, Knowlton A. HIV prevention among drug users: outcome of a network-oriented peer outreach intervention. Health Psychol 2003; 22:332–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vlahov D, Safaien M, Lai S, et al. . Sexual and drug risk-related behaviours after initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users. AIDS 2001; 15:2311–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azim T, Bontell I, Strathdee SA. Women, drugs and HIV. Int J Drug Policy 2015; 26:S16–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ompad DC, Wang J, Dumchev K, et al. . Patterns of harm reduction service utilization and HIV incidence among people who inject drugs in Ukraine: a two-part latent profile analysis. Int J Drug Policy 2017; 43:7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Go VF, Hershow RB, Kiriazova T, et al. . Client and provider perspectives on antiretroviral treatment uptake and adherence among people who inject drugs in Indonesia, Ukraine and Vietnam: HPTN 074. AIDS Behav 2018; 23:1084–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boltaev AA, El-Bassel N, Deryabina AP, et al. . Scaling up HIV prevention efforts targeting people who inject drugs in Central Asia: a review of key challenges and ways forward. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013; 132:S41–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heimer R, Usacheva N, Barbour R, et al. . Engagement in HIV care and its correlates among people who inject drugs in St Petersburg, Russian Federation and Kohtla-Jarve, Estonia. Addiction 2017; 112:1421–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller WC, Hoffman IF, Hanscom B, et al. . A scalable intervention to increase antiretroviral therapy and medication-assisted treatment and reduce mortality and HIV transmission among people who inject drugs: a randomized, controlled vanguard trial (HPTN 074). Lancet 2018; 392:P747–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lancaster KE, Miller WC, Kiriazova T, et al. . Designing an individually tailored multilevel intervention to increase engagement in HIV and substance use treatment among people who inject drugs with HIV: HPTN 074. AIDS Educ Prevent 2019; 31:95–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lancaster KE, Hoffman IF, Hanscom B, et al. . Regional differences between people who inject drugs in an HIV prevention trial integrating treatment and prevention (HPTN 074): a baseline analysis. J Int AIDS Soc 2018; 21:e25195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. WHO, UNODC, UNAIDS technical guide for countries to set targets for universal access to HIV prevention, treatment and care for injecting drug users. Geneva, Switzerland, WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiriazova T, Go VF, Hershow RB, et al. . Perspectives of clients and providers on factors influencing opioid agonist treatment uptake among HIV-positive people who use drugs in Indonesia, Ukraine, and Vietnam: HPTN 074 study. Harm Reduct J 2020; 17:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margolis DA, Gonzalez-Garcia J, Stellbrink HJ, et al. . Long-acting intramuscular cabotegravir and rilpivirine in adults with HIV-1 infection (LATTE-2): 96-week results of a randomised, open-label, phase 2b, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2017; 390:1499–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orkin C, Oka S, Philibert P, et al. . Long-acting cabotegravir plus rilpivirine for treatment in adults with HIV-1 infection: 96-week results of the randomised, open-label, phase 3 FLAIR study. Lancet HIV 2021; 8:e185–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Philbin MM, Parish C, Bergen S, et al. . A qualitative exploration of women’s interest in long-acting injectable antiretroviral therapy across six cities in the women’s interagency HIV study: intersections with current and past injectable medication and substance use. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2021; 35:23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.AIDS Clinical Trial Group (ACTG). A5359: the LATITUDE study. Available at: https://actgnetwork.org/studies/a5359-the-latitude-study/. Accessed 12 May 2021.

- 23.Palumbo PJ, Zhang Y, Fogel JM, et al. . HIV drug resistance in persons who inject drugs enrolled in an HIV prevention trial in Indonesia, Ukraine, and Vietnam: HPTN 074. PLoS One 2019; 14:e0223829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sohn AH, Srikantiah P, Sungkanuparph S, Zhang F. Transmitted HIV drug resistance in Asia. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2013; 8:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bojko MJ, Mazhnaya A, Makarenko I, et al. . “Bureaucracy & beliefs”: assessing the barriers to accessing opioid substitution therapy by people who inject drugs in Ukraine. Drugs (Abingdon, Engl) 2015; 22:255–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tran BX, Vu PB, Nguyen LH, et al. . Drug addiction stigma in relation to methadone maintenance treatment by different service delivery models in Vietnam. BMC Public Health 2016; 16:238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]