Abstract

Verticillium wilt, primarily induced by the soil-borne fungus Verticillium dahliae, is a serious threat to cotton fiber production. There are a large number of really interesting new gene (RING) domain-containing E3 ubiquitin ligases in Arabidopsis, of which three (At2g39720 (AtRHC2A), At3g46620 (AtRDUF1), and At5g59550 (AtRDUF2)) have a domain of unknown function (DUF) 1117 domain in their C-terminal regions. This study aimed to detect and characterize the RDUF members in cotton, to gain an insight into their roles in cotton’s adaptation to environmental stressors. In this study, a total of 6, 7, 14, and 14 RDUF (RING-DUF1117) genes were detected in Gossypium arboretum, G. raimondii, G. hirsutum, and G. barbadense, respectively. These RDUF genes were classified into three groups. The genes in each group were highly conserved based on gene structure and domain analysis. Gene duplication analysis revealed that segmental duplication occurred during cotton evolution. Expression analysis revealed that the GhRDUF genes were widely expressed during cotton growth and under abiotic stresses. Many cis-elements related to hormone response and environment stressors were identified in GhRDUF promoters. The predicted target miRNAs and transcription factors implied that GhRDUFs might be regulated by gra-miR482c, as well as by transcription factors, including MYB, C2H2, and Dof. The GhRDUF genes responded to cold, drought, and salt stress and were sensitive to jasmonic acid, salicylic acid, and ethylene signals. Meanwhile, GhRDUF4D expression levels were enhanced after V. dahliae infection. Subsequently, GhRDUF4D was verified by overexpression in Arabidopsis and virus-induced gene silencing treatment in upland cotton. We observed that V. dahliae resistance was significantly enhanced in transgenic Arabidopsis, and weakened in GhRDUF4D silenced plants. This study conducted a comprehensive analysis of the RDUF genes in Gossypium, hereby providing basic information for further functional studies.

Keywords: E3 ubiquitin ligase, DUF1117, upland cotton, GhRDUF4D, Verticillium dahliae

1. Introduction

Cotton (Gossypium) is well-known as the most important natural fiber. The cultivated tetraploids upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum, AD1) and sea island cotton (G. barbadense, AD2) have resulted from hybridization and genome doubling from the diploid ancestors of G. herbaceum (A1) or G. arboreum (A2) and G. raimondii (D5) [1,2,3]. More than 90% of cultivated cotton crops comprise upland cotton, owing to its high fiber production volumes and high tolerance to various environmental conditions. Verticillium wilt is primarily caused by the soil-borne fungus V. dahliae, and is a serious disease that poses a significant threat to the fiber industry. Because of cotton’s limited germplasm diversity, V. dahliae-resistant cotton varieties are difficult to obtain via traditional breeding practices [4]. Efforts have been made to determine the molecular basis for Verticillium wilt tolerance in cotton. A set of V. dahliae-responsive genes have been identified that primarily involve the jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), and ethylene (ET) signaling pathways [5,6,7,8]. Moreover, the function of several individual genes, including GhPMEI3 [9], GhLAC15 [10], GhGhARPL18A-6 [11], GbSOBIR [12], and GhGPA [13], have been investigated in cotton for protection from Verticillium wilt. These studies have contributed to our understanding of the complex innate defense mechanisms against V. dahliae infection in cotton.

The ubiquitin-26S proteasome system plays a major role in protein degradation, an important regulatory mechanism that mediates cell responses to intracellular signals and adaptation to environmental conditions [14,15]. The ubiquitination cascade is catalyzed by the ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2), and ubiquitin protein ligase (E3) [16,17,18]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, there are 2 E1 enzymes, 37 E2 enzymes, and more than 1400 predicted E3 ubiquitin ligases [19]. The large number of E3 ligases is primarily responsible for substrate specificity [14]. The E3 ligases can be grouped into four defined classes, according to the presence of HECT (homologous to E6-associated protein carboxyl terminus), U-box, really interesting new gene (RING), or cullin–RING ligases [14,20,21]. The RING domain is a cysteine (Cys)-rich region containing 40–60 amino acids. It spatially contains eight conserved Cys and histidine (His) residues as metal ligands, which can chelate two zinc ions to transfer ubiquitin to target proteins [19]. In addition, the RING domains were found to be essential for catalyzing the E3 ligase activity of RING-containing proteins [22].

RING domains are divided into two canonical types, C3HC4 (RING-HC) and C3H2C3 (RING-H2), in terms of a Cys or His amino acid residue at the metal ligand position five [23,24]. In addition, other modified types of RING domains containing E3 ligases have been found in A. thaliana, Oryza sativa, Ostreococus tauri, and Brassica rapa [19,25,26,27,28]. The majority of RING-containing proteins have been actively examined in in vitro ubiquitination assays [25]. The biological function of RING-containing proteins is to participate in anther development, secretory pathways, plant defense, and pathogen response [25,27]. For example, SDIR1, a RING-type E3 ligase, modulates salt and drought stress responses in Arabidopsis [29,30]. Furthermore, a study has shown that the rice C3HC4 protein improves resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 in transgenic A. thaliana [31]. The reduced expression of the rice E3 enzyme XB3 compromised the avirulent breed of Xanthomonas oryzae pv oryzae resistance [32]. OsRFPH2-10, a RING-H2 finger E3 ubiquitin ligase, is involved in antiviral defense in the early stages of rice dwarf virus infection [33].

A large number of RING domain-containing E3 ubiquitin ligases have been identified in Arabidopsis [25]. Among them, At3g46620 (AtRDUF1), At5g59550 (AtRDUF2), and At2g39720 (AtRHC2A) have a domain of unknown function (DUF) 1117 domain. AtRDUF1, AtRDUF2, and AtRHC2A are RING-H2 type RING finger family proteins [25]. AtRDUF1 has been reported to positively regulate salt stress [34], whereas the suppression of AtRDUF1 and AtRDUF2 reduces tolerance to abscisic acid (ABA)-mediated drought stress in Arabidopsis [35]. Furthermore, AtRDUF1 and AtRDUF2 respond to chitin, a plant defense elicitor, with 7.9- and 9.0-fold increased expression 30 min after induction, respectively [36]. These studies indicate that the RDUF genes are involved in biotic and abiotic plant adaptations to the environment. To investigate the potential role of the RDUF genes in Gossypium, we characterized the RDUF gene family in four cotton species: G. arboretum, G. raimondii, G. hirsutum, and G. barbadense. In addition, we investigated GhRDUF4D ectopic expression in Arabidopsis and the virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) approach in upland cotton. This study sheds light on GhRDUF4D’s role against V. dahliae infection in cotton, and will help in understanding the function of RDUF genes in plant immunity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterization of RDUF Gene Members in Gossypium

The genome datasets of G. hirsutum acc. TM-1 (AD1, ZJU_v2.1) [2], G. barbadense acc. Hai7124 (AD2, ZJU_v1.1) [2], and its assumed ancestors of G. arboreum Shixiya 1 (A2, CRI_v1.0) [37] and G. raimondii (D5, JGI_v2.1) [38] were downloaded from the CottonGen website [39]. The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) program BLASTp was used to detect candidate RDUF genes using the Arabidopsis RDUF amino acid (aa) sequences of AtRDUF1 (AT3G46620), AtRDUF2 (AT5G59550), and AtRHC2A (AT2G39720) as queries. Then, the Pfam RDUF1117 domain (PF06547) was used for the examination of RDUF members via a HMMER search. The RDUF genes were named based on their chromosomal location. Genes in tetraploid cotton were named as per the homologous relationship of each subgenome, with “A” and “D” indicating the homologous genes in At and Dt subgenomes, respectively. In addition, the theoretical molecular weight (MW) and isoelectric point (pI) were estimated by ExPASy [40], and the subcellular localization was evaluated by TargetP-2.0 Server (available online: http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP/ accessed on 30 December 2020). To detect cis-elements in the RDUF promoter regions, the 2 kb upstream regions of the start codon of the RDUF genes were submitted to the PlantCARE database [41].

2.2. Phylogenetic, Gene Structure and Conserved Domain, and Motif Analysis

A maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was built using the bootstrap test method with 1000 replicates [42], and then the tree was visualized via the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) online tool [43]. Subsequently, gene structure and the conserved domain of the RDUF proteins were detected and displayed using the Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS, v2.0) [44], SMART [45], and TBtools (v1.0983) [46] softwares. Moreover, the conserved motifs in the RDUF proteins were identified using the MEME program [47], and the functional annotations were confirmed using the InterProScan website.

2.3. Chromosomal Location, Gene Synteny, and RNA-Seq Dataset Analysis

The chromosomal localization of the RDUF genes were determined and displayed using the Mapchart 2.2 software [48], based on the downloaded genomic datasets. MCScanX [49] software was used for gene synteny analysis, whereas Circos (v0.69) [50] software was used for graphical depiction. The expression profiles of GhRDUFs were analyzed from publicly released RNA-Seq datasets in silico, with the BioProject accession number PRJNA490626 [2]. Transcript levels were calculated with HISAT and StringTie softwares [51], in the form of fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) values.

2.4. Transcription Factors (TFs) and miRNAs in Targeting GhRDUF Genes

TFs involved in the regulation of the GhRDUF genes were predicted using PlantRegMap [52]. The cDNA of the GhRDUF homologs were submitted to the psRNATarget website to search for potential miRNAs [53]. Then, Cytoscape (v3.7.2) was used to display the regulatory relationships between the predicted TFs, miRNAs, and the targeted GhRDUF genes [54].

2.5. Cotton Seedlings under Hormone Treatments

G. hirsutum cv. Zhongzhimian No. 2 were stored in our laboratory and used for gene expression analysis in response to plant hormone treatments. The cotton seedlings were cultivated in Hoagland liquid medium. The seedlings were sprayed uniformly at the three-leaf stage with 2 mM methyl salicylic acid (MeSA), 100 μM methyl jasmonate (MeJA), or ethylene (ET) released from 5 mM ethephon. The leaves from three cotton seedlings were collected at each time points of 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h after spraying with MeSA, MeJA, and ET, respectively, and then immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for total RNA extraction.

2.6. GFP Vector Construction and Fluorescent Visualization

The full-length cDNA of GhRDUF4D without the termination codon was cloned into the pCAMBIA2300-GFP vector, via the ClonExpress® MultiS One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The precursor sequence (gra-miR482c) and its mutant (gra-miR482c-mut) was biosynthesized by BGI Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China), and then inserted into the pBI121 vector. After transformation into the A. tumefaciens strain GV3101, the transient expression assay was performed on tobacco leaves using an MMA solution (10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM N-morpholino ethanesulfonic acid and 200 mM acetosyringone), to validate the interactional relationships between gra-miR482c and GhRDUF4D using an in vivo plant imaging system (NightSHADE LB 985, Berthold, Germany).

2.7. Overexpression Vector Construction and Screening of Transgenic Arabidopsis

The full cDNA length of GhRDUF4D was cloned to confirm its sequence. The ClonExpress® MultiS One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) was used to construct GhRDUF4D to the pCAMBIA2300 vector under the control of a CaMV35S promoter, the recombinant vector was named as 35S::GhRDUF4D in the present study. The 35S::GhRDUF4D construction was introduced into the A. tumefaciens strain GV3101, and then transformed into A. thaliana using the floral-dip method. Positive transgenic Arabidopsis were confirmed using the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods. The specific primers used in this study are provided in Supplementary Table S1. The T0–T3 seeds were screened in MS medium containing antibiotics. The T3 transgenic Arabidopsis lines with the correct segregation ratio were used for the V. dahliae resistance analysis.

2.8. VIGS Vector Construction and Assays Performing

Based on the expression module, GhRDUF4D was selected for functional analysis using the virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) approach. In brief, the 300 bp fragment of GhRDUF4D was cloned from the root tissue of G. hirsutum cv. Zhongzhimian No. 2. Then, ClonExpress® MultiS One Step Cloning Kits (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) were used to link the tobacco rattle virus (TRV) vector (pYL156) with the Xba I and BamH I restriction sites, the recombined vector was named as TRV::GhRDUF4D in this study. Next, the recombined vector TRV::GhRDUF4D, the pYL156 empty vector TRV::00, the marker vector TRV::CLA1 (Cloroplastos alterados 1), and the auxiliary vector pLY192 were introduced into the A. tumefaciens strain GV3101. Subsequently, a single colony of the strain was resuspended in an MMA solution to an OD600 of 1.0. Finally, the suspension of TRV::00 and TRV::GhRDUF4D were infected onto the cotyledons of the cotton seedlings. When the photobleaching phenotype was presented in the marker construct of TRV::CLA1, the true leaves were collected from each treatment to detect GhRDUF4D expression using RT-qPCR. Subsequently, the GhRDUF4D silenced plants and the control were subjected to V. dahliae inoculation.

2.9. V. dahliae Infection and Disease Evaluation

The highly aggressive, defoliating V. dahliae strain, Vd991, was used for inoculation. In brief, the spore suspensions of Vd991 were prepared at concentrations of 1 × 107 spore mL−1 with sterile water. The cotton and Arabidopsis plant roots were then incubated with the conidial suspension for 10 min. The roots of Arabidopsis seedlings planted on MS medium were treated with 2 μL of 5 × 103 spore mL−1 conidial suspension for infection. The disease index test was calculated as previously described [5]. Cotton stems were cut from each line at the same position, using a microscope to determine vascular wilt symptoms. The fungal biomass was detected according to the method described by Liu et al. [55]. In brief, total DNA was extracted from cotton seedling stems at 3 weeks post-inoculation, and then the specific primers were employed to detect fungal DNA using quantitative PCR (Table S1). The V. dahliae recovery assay was performed as per Zhang et al. [11]. The significant differences for disease index and fungal biomass analysis were determined using the Student’s t test.

2.10. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Analysis and Callose

ROS was detected using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining. Leaves from TRV::0 and TRV::GhRDUF4D cotton plants from 12 h after inoculation were suspended in DAB staining solution (1 mg/mL, pH = 7.5) in darkness for 8 h. Then, leaves were decolorized in 95% ethanol and absolute ethanol in boiling water, until the green color faded. Next, 70% glycerin was added to soak the leaves; they were then observed under a stereomicroscope. At least three plants were sampled for each treatment.

Callose depositions were observed using aniline blue staining. Leaf samples at 7 days post-inoculation (dpi) were first destained in a fixative solution (3:1 ethanol/acetic acid) for 3 h, and then soaked in 70% and 50% ethanol for 2 h. Afterwards, the leaves were transferred into water for 12 h and destained in NaOH solution (10%, w/v) for 2 h. Finally, the leaves were stained with 0.01% (w/v) aniline blue for 3 h, and visualized using fluorescence microscopy.

2.11. RT-qPCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated using RNA extraction kits (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). cDNA was reverse-transcribed using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Specific primers were designed via the Primer6 software and are listed in Table S1. RT-qPCR analysis was performed as per Zhao et al. [56]. The housekeeping genes, GhUBQ7 in cotton and AtSAND in Arabidopsis, were used as internal references. The relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. The assays were performed in triplicate. The significant differences were determined using the Student’s t test.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis of RDUF Family Genes

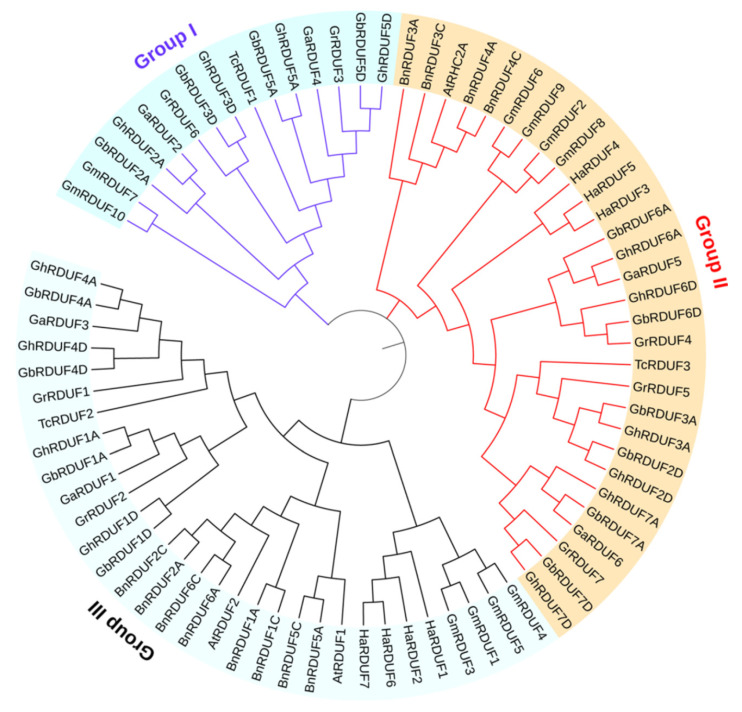

The Pfam family of DUF1117 (PF06547) was used as a query to search for RDUF. At the same time, the AtRDUF amino acid (aa) sequences of AtRDUF1 (AT3G46620), AtRDUF2 (AT5G59550), and AtRHC2A (AT2G39720) in Arabidopsis were used for the BLASTp search in the Gossypium protein database. We detected 6, 7, 14, and 14 RDUF genes in the A2, D5, AD1, and AD2 genomes, respectively. We observed that the RDUF gene number in the tetraploid G. hirsutum and G. barbadense was probably twice than that observed in the diploid cottons (G. arboreum and G. raimondii), suggesting hybridization and whole genome duplication (WGD) events. Meanwhile, 3 TcRDUF genes in cacao (Theobroma cacao), 10 GmRDUF genes in soybean (Glycine max), 12 BnRDUF genes in oilseed (Brassica napus), and 7 HaRDUF genes in sunflower (Helianthus annuus) were also detected. The phylogenetic tree showed that the 76 RDUF proteins were categorized into 3 groups: Group I, Group II, and Group III (Figure 1). In addition, we also found that the RDUF family proteins were clustered closely in the different species, indicating that RDUF proteins evolved independently after separation from other species. Another phylogenetic tree containing monocotyledonous crop RDUFs was built, including three OsRDUF proteins from Oryza sativa, five ZmRDUF proteins from Zea mays, and eight TaRDUF proteins from Triticum aestivum (Table S2). The RDUFs in monocotyledonous crops were clustered far from those found in dicotyledonous crops (Figure S1, in green clade), suggesting that the RDUFs in monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous crops likely evolved independently. The RDUF-protein phylogenetic trees from the four cotton species were also analyzed. We found that the RDUF members in all four species were categorized into three groups (Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of the RDUF protein family. At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Bn, Brassica napus; Ga, G. arboretum; Gr, G. raimondii; Gh, G. hirsutum; Gb, G. barbadense; Gm, Glycine max; Ha, Helianthus annuus; Tc, Theobroma cacao.

Data from the 41 RDUFs in Gossypium were also investigated. The coding sequence (CDS) length of the 41 RDUF genes ranged from 953 bp (GrRDUF4) to 1312 bp (GbRDUF7A). Most of the RDUF genes did not contain an intron, but GaRDUF3, GrRDUF4, GbRDUF2D, and GbRDUF7A had two exons each. The amino acid sequences of the RDUF proteins were also characterized. The MW ranged from 34.13 kDa (GbRDUF3A) to 46.92 kDa (GbRDUF7A), and the pI ranged from 5.17 (GbRDUF4A) to 9.27 (GaRDUF4). Subcellular location analysis showed that 23 of the 41 RDUF proteins were predicted to be located in the nucleus, and 13 RDUF proteins were predicted to be located in the chloroplasts (Table 1).

Table 1.

Identification of the RDUF genes in G. arboretum, G. raimondii, G. hirsutum, and G. barbadense. Abbreviations: chlo, chloroplast; cyto, cytoplasm; mito, mitochondrion; nucl, nucleus.

| Name | Gene Locus ID | Nucleic Acid | Amino Acid | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | CDS (bp) | Exons | Size (aa) | Mw (Da) | pI | Formula | Subcellular Location | ||

| GaRDUF1 | Ga01G2247.1 | Chr01: 104114537-104114537 | 1095 | 1 | 364 | 40,145.64 | 6.72 | C1709H2699N529O553S20 | cyto: 5, nucl: 3, chlo: 2 |

| GaRDUF2 | Ga04G0720.1 | Chr04: 15879489-15880598 | 1110 | 1 | 369 | 41,080.80 | 8.36 | C1780H2753N547O545S17 | nucl: 8, mito: 4, chlo: 1 |

| GaRDUF3 | Ga07G1079.1 | Chr07: 15730492-15731585 | 1023 | 2 | 340 | 38,340.47 | 5.96 | C1655H2554N498O525S16 | chlo: 6, mito: 4, nucl: 2 |

| GaRDUF4 | Ga09G1752.1 | Chr09: 75411415-75412479 | 1065 | 1 | 354 | 39,662.52 | 9.27 | C1720H2690N536O517S16 | nucl: 7, chlo: 3, mito: 3 |

| GaRDUF5 | Ga10G0274.1 | Chr10: 3699993-3701000 | 1008 | 1 | 335 | 36,635.1 | 6.15 | C1588H2470N474O489S19 | chlo: 10, nucl: 2, cyto: 1 |

| GaRDUF6 | Ga13G0217.1 | Chr13: 2143604-2144689 | 1086 | 1 | 361 | 39,945.89 | 7.03 | C1729H2687N519O529S23 | nucl: 14 |

| GrRDUF1 | Gorai.001G111900.1 | Chr01: 13043565-13045611 | 1099 | 1 | 361 | 40,055.51 | 5.77 | C1728H2685N513O552S18 | chlo: 5, mito: 5, nucl: 1 |

| GrRDUF2 | Gorai.003G129300.1 | Chr03: 38196500-38198583 | 1114 | 1 | 366 | 40,318.81 | 6.72 | C1716H2710N530O557S20 | nucl: 4, cyto: 3, mito: 3 |

| GrRDUF3 | Gorai.006G171100.1 | Chr06: 43050323-43052612 | 1078 | 1 | 354 | 39,714.48 | 9.02 | C1718H2682N534O522S17 | nucl: 10, chlo: 2, mito: 2 |

| GrRDUF4 | Gorai.011G267000.1 | Chr11: 59881340-59882767 | 953 | 2 | 313 | 34,156.21 | 8.39 | C1485H2298N448O453S15 | chlo: 9, nucl: 2, mito: 2 |

| GrRDUF5 | Gorai.012G071400.1 | Chr12: 10539979-10541968 | 1011 | 1 | 332 | 36,698.02 | 7.59 | C1580H2471N491O488S17 | nucl: 8, mito: 3, chlo: 2 |

| GrRDUF6 | Gorai.012G105100.1 | Chr12: 23596133-23598256 | 1123 | 1 | 369 | 41,122.88 | 8.36 | C1783H2759N547O545S17 | nucl: 8, mito: 4, chlo: 2 |

| GrRDUF7 | Gorai.013G021800.1 | Chr13: 1532332-1533783 | 1102 | 1 | 362 | 40,120.10 | 8.02 | C1733H2701N527O529S23 | nucl: 14 |

| GhRDUF1A | GH_A03G0566 | A03: 8775627-8776721 | 1116 | 1 | 364 | 40,144.7 | 6.72 | C1711H2704N528O552S20 | cyto: 5, nucl: 3, chlo: 2 |

| GhRDUF2A | GH_A04G1023 | A04: 72823528-72824637 | 1132 | 1 | 369 | 41,114.82 | 8.36 | C1783H2751N547O545S17 | nucl: 9, mito: 4, chlo: 1 |

| GhRDUF3A | GH_A05G3679 | A05: 96863898-96864839 | 960 | 1 | 313 | 34,110.2 | 7.59 | C1470H2308N450O457S16 | nucl: 7, mito: 4, chlo: 2 |

| GhRDUF4A | GH_A07G1092 | A07: 16689279-16690247 | 988 | 1 | 322 | 36,130.2 | 5.25 | C1566H2418N456O497S17 | chlo: 6, mito: 4, nucl: 2 |

| GhRDUF5A | GH_A09G1709 | A09: 74061366-74062430 | 1086 | 1 | 354 | 39,765.64 | 9.25 | C1727H2695N537O517S16 | mito: 7, nucl: 3.5, chlo: 3 |

| GhRDUF6A | GH_A10G2448 | A10: 111936421-111937428 | 1028 | 1 | 335 | 36,635.1 | 6.15 | C1588H2470N474O489S19 | chlo: 10, nucl: 2, cyto: 1 |

| GhRDUF7A | GH_A13G0199 | A13: 2147580-2148665 | 1107 | 1 | 361 | 39,948.85 | 7.03 | C1727H2684N520O530S23 | nucl: 14 |

| GhRDUF1D | GH_D03G1398 | D03: 45757090-45758175 | 1107 | 1 | 361 | 39,809.38 | 6.72 | C1696H2687N525O546S20 | cyto: 4, chlo: 3, nucl: 3 |

| GhRDUF2D | GH_D04G0664 | D04: 11134024-11135037 | 1034 | 1 | 337 | 37,207.58 | 8.34 | C1602H2506N498O495S17 | nucl: 9, mito: 3, chlo: 2 |

| GhRDUF3D | GH_D04G1354 | D04: 44739659-44740768 | 1132 | 1 | 369 | 41,202.03 | 8.56 | C1788H2768N550O543S17 | nucl: 9, mito: 3, chlo: 2 |

| GhRDUF4D | GH_D07G1077 | D07: 13116176-13117261 | 1107 | 1 | 361 | 40,221.74 | 5.82 | C1737H2699N515O553S18 | chlo: 6, mito: 4, nucl: 2 |

| GhRDUF5D | GH_D09G1658 | D09: 43682720-43683784 | 1086 | 1 | 354 | 39,723.49 | 8.89 | C1720H2681N533O522S17 | nucl: 9, mito: 3, chlo: 1 |

| GhRDUF6D | GH_D10G2556 | D10: 64049541-64050551 | 1031 | 1 | 336 | 36,686.15 | 6.89 | C1590H2471N477O488S19 | chlo: 8, nucl: 3, mito: 2 |

| GhRDUF7D | GH_D13G0196 | D13: 1703107-1704195 | 1110 | 1 | 362 | 40,142.16 | 8.02 | C1735H2703N529O527S23 | nucl: 14 |

| GbRDUF1A | GB_A03G0554 | A03: 8482495-8483589 | 1116 | 1 | 364 | 40,144.7 | 6.72 | C1711H2704N528O552S20 | cyto: 5, nucl: 3, chlo: 2 |

| GbRDUF2A | GB_A04G1063 | A04: 67240547-67241656 | 1132 | 1 | 369 | 41,080.8 | 8.36 | C1780H2753N547O545S17 | nucl: 8, mito: 4, chlo: 1 |

| GbRDUF3A | GB_A05G3770 | A05: 94125157-94126098 | 960 | 1 | 313 | 34,134.26 | 7.57 | C1474H2312N448O457S16 | nucl: 6, mito: 5, chlo: 2 |

| GbRDUF4A | GB_A07G1079 | A07: 17016234-17017202 | 988 | 1 | 322 | 36,188.24 | 5.17 | C1568H2420N456O499S17 | chlo: 6, mito: 4, nucl: 2 |

| GbRDUF5A | GB_A09G1832 | A09: 70138025-70139089 | 1086 | 1 | 354 | 39,716.57 | 9.27 | C1722H2692N538O517S16 | mito: 7, nucl: 3.5, chlo: 3 |

| GbRDUF6A | GB_A10G2617 | A10: 108379933-108380940 | 1028 | 1 | 335 | 36,587.06 | 6.15 | C1584H2470N474O489S19 | chlo: 9, nucl: 2, mito: 2 |

| GbRDUF7A | GB_A13G0200 | A13: 2045827-2048345 | 1312 | 2 | 428 | 46,919.93 | 8.38 | C2038H3185N603O622S26 | nucl: 14 |

| GbRDUF1D | GB_D03G1418 | D03: 45690505-45691611 | 1129 | 1 | 368 | 40,430.98 | 6.72 | C1719H2726N532O559S20 | nucl: 4, chlo: 3, cyto: 3 |

| GbRDUF2D | GB_D04G0687 | D04: 10848147-10850667 | 1049 | 2 | 342 | 37,749.2 | 8.05 | C1625H2541N503O503S18 | nucl: 9, mito: 3, chlo: 2 |

| GbRDUF3D | GB_D04G1434 | D04: 45218042-45219151 | 1132 | 1 | 369 | 41,132.92 | 8.36 | C1785H2761N547O544S17 | nucl: 8, mito: 4, chlo: 2 |

| GbRDUF4D | GB_D07G1081 | D07: 13412269-13413354 | 1107 | 1 | 361 | 40,182.70 | 5.89 | C1734H2698N516O552S18 | chlo: 5, mito: 5, nucl: 1 |

| GbRDUF5D | GB_D09G1672 | D09: 45246636-45247700 | 1086 | 1 | 354 | 39,735.54 | 8.89 | C1722H2685N533O521S17 | nucl: 9, mito: 3, chlo: 2 |

| GbRDUF6D | GB_D10G2571 | D10: 63188105-63189115 | 1031 | 1 | 336 | 36,658.1 | 6.46 | C1589H2467N475O489S19 | chlo: 8, mito: 3, nucl: 2 |

| GbRDUF7D | GB_D13G0189 | D13: 1578513-1579601 | 1110 | 1 | 362 | 40,112.13 | 8.03 | C1734H2701N529O526S23 | nucl: 14 |

3.2. Chromosomal Localization and Gene Synteny Analysis of RDUF Genes

To reveal the homolog relationships between the RDUF genes in Gossypium, gene localization on chromosomes as well as gene synteny analysis were performed. The results showed that the RDUF genes in diploid cotton species were distributed on six chromosomes, with two GrRDUF genes localized on chr12 in G. raimondii. In tetraploid cotton species, we observed that seven RDUF genes of the At subgenome were distributed on seven chromosomes, with each RDUF gene located on one chromosome. The seven RDUF genes of the Dt subgenome were located on six chromosomes, with RDUF2D and RDUF3D located on the D04 chromosome (Figure S3). Gene localization analysis revealed that most of the RDUF loci were highly symmetric between the At and Dt subgenomes. RDUF gene localization in the At subgenomic chromosomes consistently agreed with their homologs in the Dt subgenomic chromosomes. Nevertheless, RDUF2A and RDUF3A were located on the A03 and A04 chromosomes, respectively, but their homologs, RDUF2D and RDUF3D, were all located on the D04 chromosome.

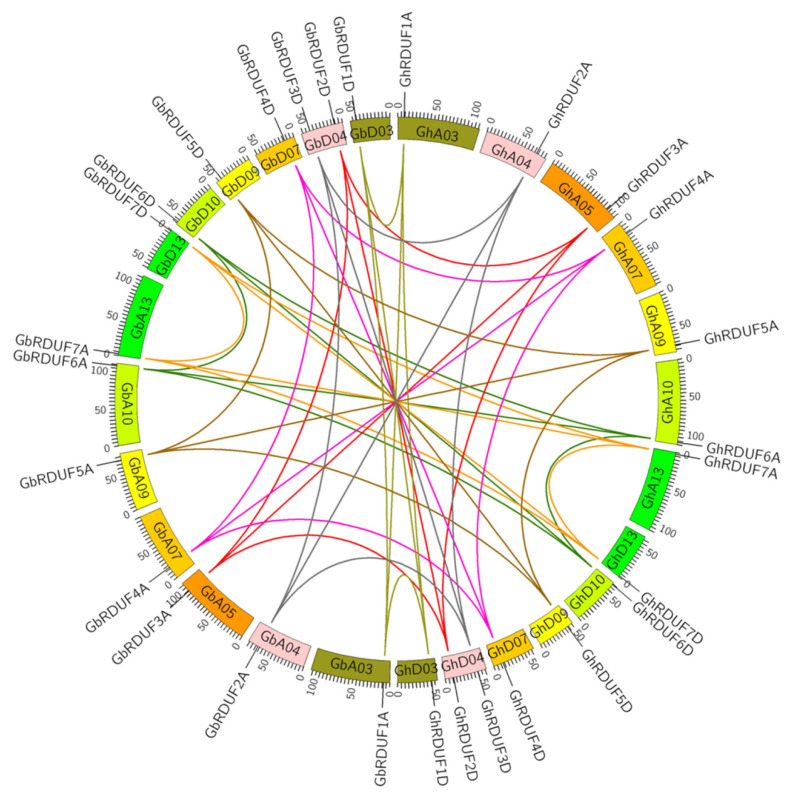

Gene synteny analysis was performed to understand the relationships of the RDUF genes between G. hirsutum and G. barbadense. We observed that homologous genes in or between each cotton genome were highly syntenic. The RDUF genes in G. hirsutum were consistent with their orthologs in G. barbadense (Figure 2). We also investigated whether GhRDUF1A/D and GhRDUF4A/D; GhRDFU2A/3D and GhRDUF5A/D; and GhRDUF3A/2D, GhRDUF6A/D and GhRDUF7A/D might be duplicated genes (Figure S4). The RDUF genes in the diploid cotton species (G. arboreum and G. raimondii) were twice more than those in cacao, reflecting that at least one WGD event occurred after cotton diverged from cacao. To explore the different selective constrains on the RDUF genes, the Ka/Ks ratios for the duplicated genes were calculated (Table S3). The majority of the Ka/Ks values of the RDUF gene pairs were <1, suggesting that the RDUF genes primarily experienced purified selection. Furthermore, 3 RDUF gene pairs exhibited neutral selection, whereas 13 RDUF duplicate gene pairs might have experienced positive selection in the 4 cotton species.

Figure 2.

Synteny relationship between RDUF genes in G. hirsutum and G. barbadense. The relationship is presented using Circos software. The homologous chromosomes in At and Dt subgenomes are displayed in the same color. The synteny relationships between the RDUF genes are identified by different colors. Bottle green lines, ortholog or paralog genes of RDUF6A/D; light brown lines, ortholog or paralog genes of RDUF1A/D; dark brown lines, ortholog or paralog genes of RDUF5A/D; red lines, ortholog or paralog genes of RDUF3A/2D; orange lines, ortholog or paralog genes of RDUF7A/D; pink lines, ortholog or paralog genes of RDUF4A/D; and gray lines, ortholog or paralog genes of RDUF2A/3D.

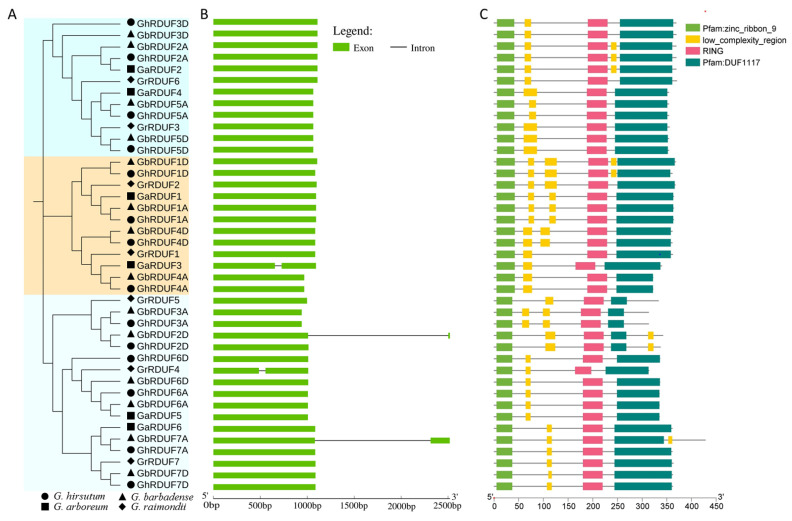

3.3. Conserved Structure and Domains in GhRDUF Proteins

A total of 41 RDUF proteins were used to understand phylogenetic relationships and gene structures. They were classified into three groups, in agreement with those in each cotton species (Figure 3A). The RDUF proteins in the A genome and At subgenome, as well as their orthologs in the D genome and the Dt subgenome tended to consistently form one clade, indicating that the tetraploid cottons might have originated from a hybridization and WGD event of the two diploid cottons. Gene structure analysis displayed that most of the RDUF genes contained only one exon (Figure 3B). Consistently, RDUF members with similar structures were grouped in the same clade.

Figure 3.

Gene structure and conserved domains in RDUF members in Gossypium. (A) Phylogenetic tree of RDUF proteins in four cotton species. (B) Gene structure of exons and introns in RDUF genes. (C) The conserved domains in RDUF proteins.

The conserved domains were analyzed to understand the function of RDUF proteins in cotton. All the RDUF proteins in the four cotton species contained the zinc_ribbon_9 domain at the C-terminal, the RDUF117 domain at the N-terminal, the RING domain, and a low_complexity_region domain. Characteristically, the GrRDUF5, GbRDUF3A, GhRDUF3A, GbRDUF2D, and GhRDUF2D proteins contained an abbreviated RDUF117 domain. GbRDUF2D and GhRDUF2D contained the low_complexity_region domain at the N-terminal. GbRDUF2A, GhRDUF2A, GaRDUF2, GhRDUF1D, and GbRDUF1D possessed the low_complexity_region domain between the RING and the RDUF117 domain (Figure 3C). Subsequently, the conserved motifs were detected using the MEME website. All 41 RDUF proteins contained motif_3, motif_5, motif_6, and motif_7. Most of the RDUF proteins contained motif 2, except for GaRDUF3. GrRDUF4 did not contain motif 1, whereas the RDUF3A/2D clade was without motif_4. GrRDUF4 and GrRDUF7 did not have motif_8, and the RDUF1A/D clade was without motif_9. However, only the RDUF6A/D clade had motif_10 (Figure S5). The motif functions were annotated in the Pfam software, with motif_1 belonging to the RING finger domain, motif_3 and motif_6 belonging to the zinc-ribbon domain, and motif_4 belonging to the RDUF1117 domain (Table S4). In addition, the amino acid sequences of the 14 GhRDUF proteins and their homolog alignments were recorded using the Clustalx software. These results showed that the sequences of the conserved domains were highly similar. The conserved metal ligand positions and zinc (Zn2+) coordinating amino acids were also investigated. We observed that all 14 GhRDUF proteins contained a His at metal ligand positions four and five, suggesting that the GhRDUF proteins belong to the RING-H2 type (Figure S6).

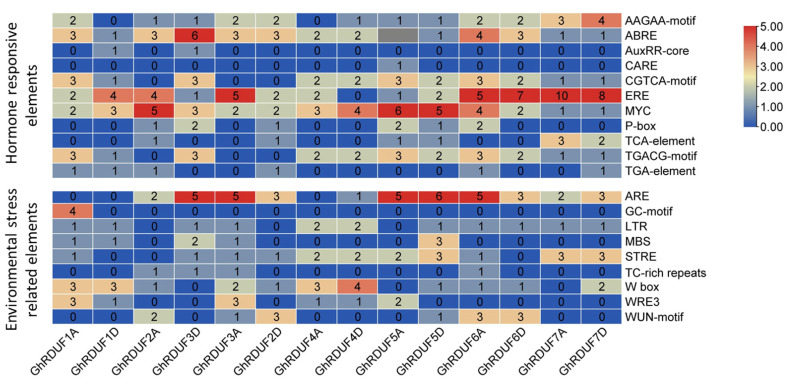

3.4. Cis-Elements in the GhRDUFs Promoter and the Targeting TFs

Globally, over 90% of cotton crops are upland cotton, owing to its higher fiber production and environmental adaptation. The promoters of the 14 GhRDUF genes were submitted in the PlantCARE database to investigate the cis-elements. In total, 75 cis-elements were predicted to exist in the GhRDUF promoter regions, with more cis-elements implicated in the light response, including Box 4, G-Box, and MRE elements (Table S5). The participation of cis-elements in the environmental and hormone stress responses are highlighted in Figure 4. Among the 11 hormone response elements predicted in the GhRDUF promoters, ERE (cis-acting ethylene responsive element), MYC (cis-acting element involved in MeJA stress), and ABRE (cis-acting element involved in abscisic acid response) elements were the most abundant, indicating that the GhRDUF genes may primarily respond to ET, MeJA, and ABA stress. Nine environmental stress-related elements were identified. The majority of them were involved in anaerobic induction (ARE), plant defense signaling (W-box), and stress responses (STRE). In particular, more W-box cis-elements were found in the GhRDUF4D promoter region, implying that GhRDUF4D participates in cotton’s response to disease.

Figure 4.

Cis-elements in GhRDUF promoter regions. Hormone response elements: AAGAA-motif, abscisic acid responsive element; ABRE, abscisic acid responsiveness element; CGTCA-motif, MeJA-responsiveness cis-acting regulatory element; AuxRR-core, auxin responsiveness cis-acting regulatory element; MYC, MeJA-responsive cis-acting regulatory element; ERE, ethylene responsive element; P-box, gibberellin-responsive element; TGACG-motif, MeJA-responsiveness element; TCA-element, salicylic acid responsiveness element; TGA-element, auxin-responsive element. Environmental stress-related elements: GC-motif, anoxic specific inducibility enhancer-like element; ARE, anaerobic induction element; LTR, low-temperature responsiveness element; MBS, MYB binding site involved in drought-inducibility; TC-rich repeats, defense and stress responsiveness cis-element; STRE, stress response element; WUN-motif, wound-responsive element; W-box, plant defense signaling cis-acting element; and WRE3, wound inducibility.

Cis-elements bind TFs to regulate the precise initiation of gene transcription. Thus, the targeting TFs of GhRDUFs were predicted using the PlantRegMap server, with a total of 188 relationships identified, including 35 TF families and 14 GhRDUF genes (Figure S7). It appears that GhRDUF1 homologous genes are regulated by additional TFs, such as those of ERF, Dof, and MYB. Meanwhile, many GhRDUF genes were regulated by the stress TFs of MYB, C2H2, and Dof, indicating that GhRDUF might regulate STREs.

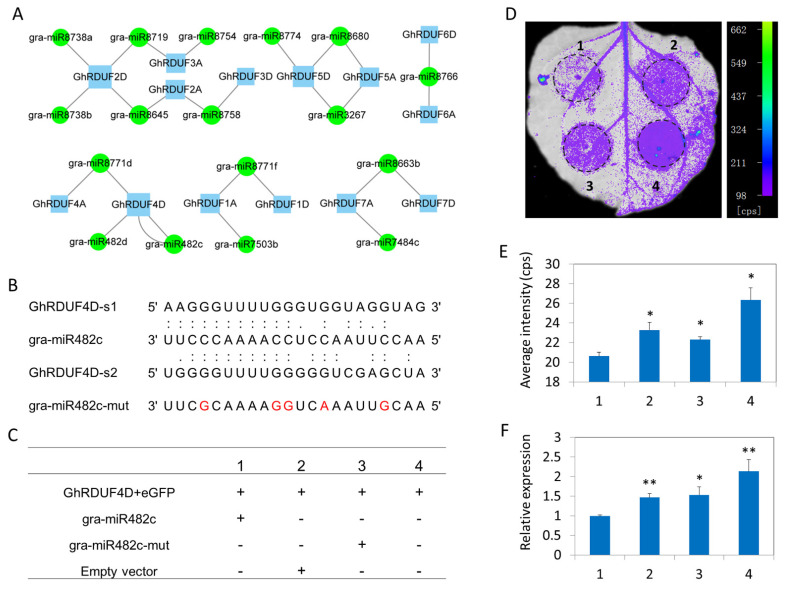

3.5. GhRDUF Targeting miRNAs Predict the Regulatory Network of GhRDUF4D and gra-miR482c

miRNAs have been widely investigated for their role in the regulation of plant development, as well as in the abiotic and biotic stress responses. In this study, 17 putative miRNAs targeting 14 GhRDUF genes were predicted by the psRNATarget website, including 27 interaction relationships. We observed that GhRDUF2D was the most targeted, and that it interacted with four miRNAs. Most of the homologous GhRDUF genes were regulated by the same miRNAs, indicating that they have similar functions. We highlighted that GhRDUF4D is possibly regulated simultaneously by gra-miR482c and gra-miR482d. Furthermore, gra-miR482c regulated GhRDUF4D expression with two binding sites, implying a strong regulatory relationship (Figure 5A). The regulatory network between GhRDUF4D and gra-miR482c was thus examined using a transient transformation assay. The five point mutations (gra-miR482c-mut) of gra-miR482 were used as the control (Figure 5B). Different vector groups were infiltrated in tobacco leaves and photographed under an ultraviolet light 3 days after infiltration (Figure 5C). We observed that the average fluorescent intensity in the GhRDUF4D-GFP and gra-miR482c precursor group was significantly impaired, compared with the control (Figure 5D,E). Moreover, the coexpression of the GhRDUF4D-GFP and gra-miR482c precursors generated an apparent reduction in the expression level of GFP (Figure 5F). These results indicated that gra-miR482c mediates the degradation of GhRDUF4D.

Figure 5.

miRNAs targeting the GhRDUF genes, and the regulatory network of GhRDUF4D and gra-miR482c. (A) Network of miRNAs and the target GhRDUFs. The predicted regulation miRNAs are shown on a green background in circles, the target GhRDUF genes are marked with blue rectangles. The regulation and targeting level are shown with varying degrees. (B) The base-pairing interaction between gra-miR482c and GhRDUF4D, and the sequence of mutant gra-miR482c. The five point mutations in gra-miR482c-mut are marked in red. (C) Vector groups in transient expression assays for each lane. (D) Co-infiltrated tobacco leaves photographed under ultraviolet light. The same areas marked by circular dotted lines were used for fluorescence intensity and gene expression analyses. (E) The average fluorescence intensity in each lane. (F) Relative expression levels of GFP in each lane. Mean ± standard error (SE), n = 3. “*” and “**” indicate that the data were significantly different at the p values of <0.05 and <0.01, respectively.

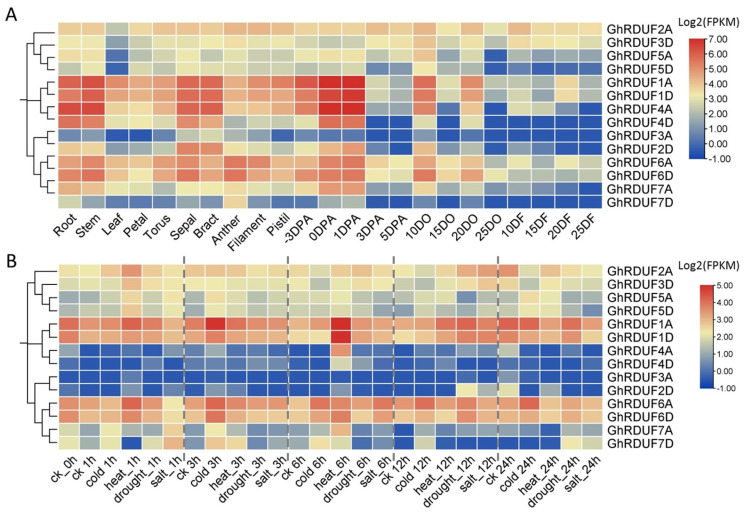

3.6. Expression Profiling of GhRDUF Genes in Upland Cotton

Gene expression models are important for gene function analysis. The public expression datasets in upland cotton were used for gene expression analysis, including the different tissues, ovule, and fiber development stages [2]. Most of the homologous genes showed similar expression patterns. GhRDUF3A and GhRDUF7D genes were barely expressed in upland cotton, whereas GhRDUF1A/D, GhRDUF4A/D, and GhRDUF6A/D homologous genes were abundantly expressed in the root, stem, sepal, bract, early developing ovules (−3, 0, and 1 DPA), and the 10 and 20 DPA ovules. These results indicate that these genes are involved in cotton reproduction and vegetable development. Meanwhile, GhRDUF1A/D was preferentially expressed in 20 DPA fibers, suggesting its role in the secondary wall thickening of fiber (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Expression patterns of GhRDUF genes in upland cotton development and under abiotic stresses. (A) Expression profiles of GhRDUF genes in cotton tissues and during development. DO and DF indicate the DPA ovule and fiber, respectively. (B) Expression profiles of GhRDUF genes under abiotic stresses. FPKM in log2 scale was used for heat map visualization.

The expression profiles of the GhRDUF genes under abiotic stress were also investigated, including in cold, heat, drought, and salt conditions. Extensive expression changes were detected under these stresses. The expression of the GhRDUF2A/3D genes was induced after 1 h of heat stress, and at 12 h under drought and salt stress. There was an impaired expression after 6, 12, and 24 h of cold stress. GhRDUF5A/D genes were upregulated at 1 h of heat and cold stress, at 3 and 12 h of cold stress, and at 24 h of cold and heat stress. GhRDUF1A/D genes were significantly elevated after 3 h of cold stress, and at 6 h under heat stress. In particular, GhRDUF4A/D genes were downregulated at 6 h under heat stress. GhRDUF6A/D genes responded to cold stress at 3, 6, 12, and 24 h. GhRDUF7A/D genes were abundantly expressed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 h when exposed to cold conditions (Figure 6B). The expression patterns of GhRDUF genes under abiotic stress were consistent with the many environment response elements that were predicted in the promoter region (Figure 4C).

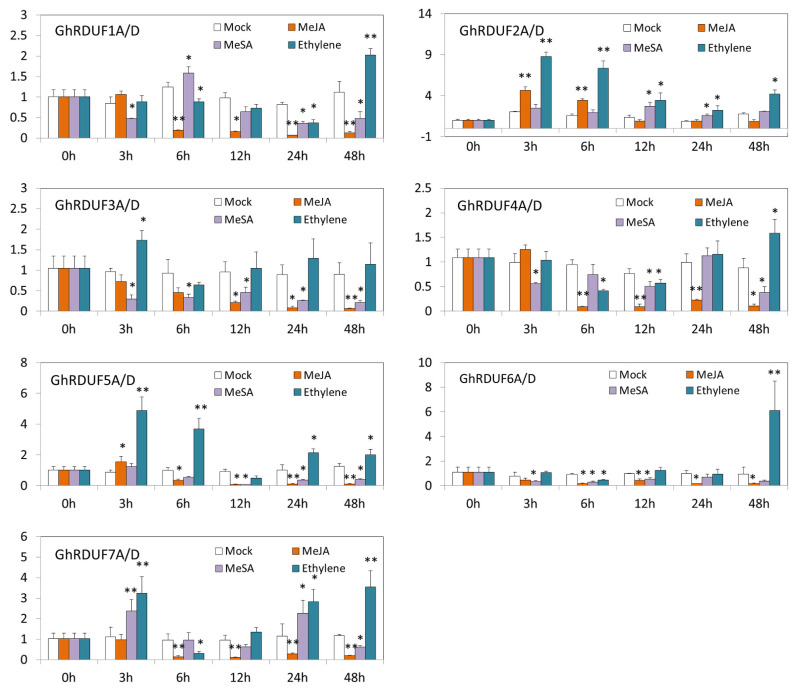

Plant hormone signals play a pivotal role in plant autoimmunity, particularly MeJA, MeSA, and ethylene. The response of the GhRDUF genes to these three hormones was investigated in this study. We observed that the highest expression of the GhRDUF genes was induced under the ethylene treatment (Figure 7). The transcript levels of GhRDUF1A/D, GhRDUF4A/D, and GhRDUF6A/D were upregulated 48 h after ethylene spraying. Many GhRDUF genes had impaired expression when exposed to the MeJA and MeSA conditions. For example, the expression levels of GhRDUF1A/D, GhRDUF3A/D, GhRDUF4A/D, and GhRDUF6A/D were weakened under the MeJA and MeSA treatments. Other GhRDUF genes showed intricate expression patterns. For example, GhRDUF2A/D was elevated under MeJA and MeSA treatments at many time points, GhRDUF5A/D was abundantly expressed under MeJA treatment at 3 h, and GhRDUF7A/D was expressed under MeSA treatment at 3 and 24 h.

Figure 7.

Expression profiles of GhRDUF genes under plant hormone treatments. Mean ± SE, n = 3. “*” and “**” indicate that the data were significantly different at the p values of <0.05 and <0.01, respectively.

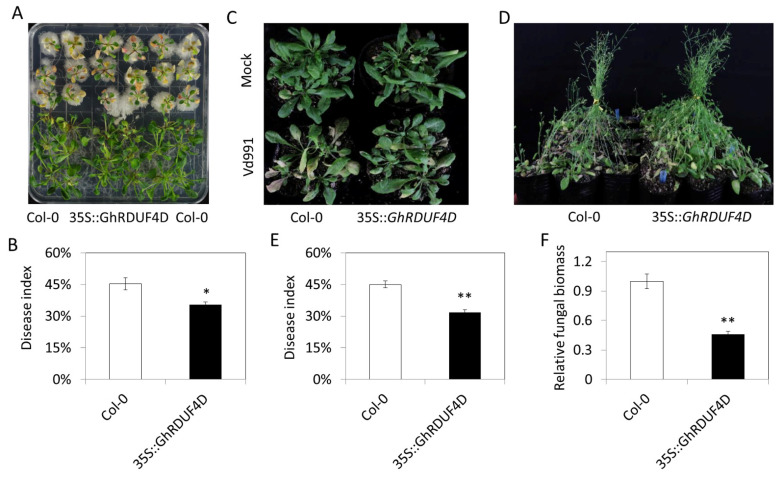

3.7. Overexpression of GhRDUF4D Enhanced the V. dahliae Resistance in Arabidopsis

The expression level of the homologous genes GhRDUF1A/D, GhRDUF4A/D, and GhRDUF7A/D were upregulated after V. dahliae infection based on RNA-Seq data, which GhRDUF4D was significantly increased at 12 and 24 h after V. dahliae infection (Figure S8A) [11]. RT-qPCR revealed that GhRDUF4D expression was increased at 24 and 48 h after V. dahliae infection (Figure S8B). Thus, GhRDUF4D was selected to validate the function by overexpression in Arabidopsis. We observed that GhRDUF4D transgenic plants were more resistant to V. dahliae infection than the control (Figure 8A,C,D). The statistical disease index result showed that V. dahliae resistance in GhRDUF4D transgenic Arabidopsis was improved significantly, not only in MS medium but also in the soil (Figure 8B,E). The relative fungal biomass was reduced in GhRDUF4D overexpressed Arabidopsis (Figure 8F). These results indicate that V. dahliae resistance was improved by the overexpression of GhRDUF4D in Arabidopsis.

Figure 8.

Overexpression of GhRDUF4D conferred V. dahliae resistance in Arabidopsis. (A) Col-0 and OE::GhRDUF4D plants inoculated with Vd991 in MS medium plate; (B) statistical analysis of disease index in plants in MS medium; (C,D) pathogenetic phenotypes of Col-0 and OE::GhRDUF4D plants at 10 and 20 dpi; (E,F) statistical analysis of the disease index and relative fungal biomass in plants in the soil. Mean ± SE, n = 3. “*” and “**” indicate that the data were significantly different at the p values of <0.05 and <0.01, respectively.

3.8. Knockdown of GhRDUF4D Compromise V. dahliae Resistance in Upland Cotton

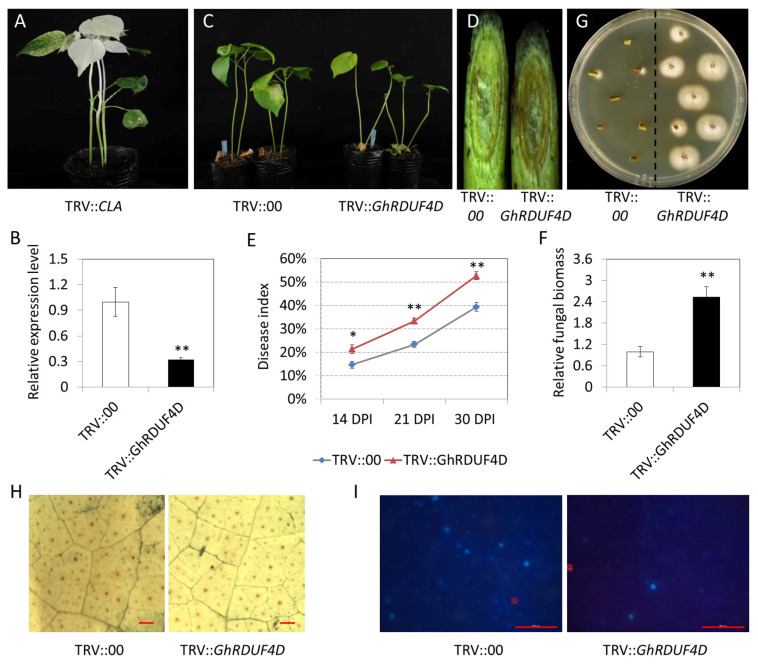

To investigate the biofunction of GhRDUF4D in the relationship between upland cotton and V. dahliae, the VIGS approach based on TRV was used to knockdown GhRDUF4D transcription levels in upland cotton. When the true leaves of the cotton seedlings were inoculated with TRV::CLA1, Agrobacteria revealed a photobleaching phenotype (Figure 9A), and the expression of GhRDUF4D was downregulated in TRV::GhRDUF4D plants (Figure 9B). The seedlings were inoculated with V991 upon reaching the three-leaf stage. The results showed that the upland cotton seedlings with GhRDUF4D downregulation were more susceptible to V. dahliae than the control (TRV::00). Indeed, GhRDUF4D-silenced plants displayed more wilting and yellow leaves, and a deeper vascular discoloration in stem tissues (Figure 9C,D). The quantification of the disease index in GhRDUF4D downregulated seedlings was higher than that of the control (Figure 9E). Fungal DNA abundance detection and fungal recovery assays displayed that greater amounts of V. dahliae had colonized the stem tissue of GhRDUF4D-silenced plants than the control (Figure 9F,G).

Figure 9.

Downregulation of GhRDUF4D weakened upland cotton resistance to V. dahliae. (A) Photobleaching of the phenotype by inoculation TRV::CLA; (B) pathogenetic phenotypes of TRV::0 and TRV::GhRDUF4D cotton plants; (C) observation of the diagonal plane of stem vascular bundle; (D) the V. dahliae recovery assays of TRV::0 and TRV::GhRDUF4D stems; (E) relative expression level of GhRDUF4D in TRV::0 and TRV::GhRDUF4D cotton plants; (F) dynamic disease index of TRV::0 and TRV::GhRDUF4D cotton plants after Vd991 infection; (G) relative fungal biomass of TRV::0 and TRV::GhRDUF4D cotton plants; and (H,I) ROS and callose deposition observation in TRV::0 and TRV::GhRDUF4D cotton leaves, bar = 200μm. Mean ± SE, n = 3. “*” and “**” indicate that the data were significantly different at the p values of <0.05 and <0.01, respectively.

ROS is regarded as an indicator of disease resistance. Thus, the ROS levels of TRV::00 and TRV::GhRDUF4D cotton leaves were stained with DAB at 12 h after V. dahliae inoculation. The results showed that ROS accumulation in TRV::GhRDUF4D plants was significantly less than that of the TRV::00 plants (Figure 9H). Callose deposition was evaluated by aniline blue staining. Compared with the control, the density of callose depositions was reduced, with more dead cells observed in GhRDUF4D-silenced cotton leaves (Figure 9I). These results indicate that the reduced expression of GhRDUF4D compromises V. dahliae resistance in upland cotton, reflecting the positive role of GhDUF4D in plant responses to pathogenic fungal infection.

4. Discussion

4.1. Evolution and Functional Diversification of GhRDUF Genes

The RING-containing proteins ubiquitously function in light signaling, phosphate homeostasis [57], anther development [58], plant defense, and pathogen response [25,29,30,31,32,33]. We analyzed the evolution and expression of GhRDUF members in cotton plants to investigate the potential role of the RDUF genes. In addition, phylogenetic trees were constructed to determine the evolutionary relationship of RDUF proteins in plants. Gene duplication plays a major role in plant genome evolution. Based on our findings, the GhRDUF genes were duplicated frequently during cotton evolution. Only one RDUF gene was detected in each group of Arabidopsis thaliana and Theobroma cacao, however, two or three members were identified in diploid cottons (G. arboretum and G. raimondii). Of these, both the RDUF2A/3D and RDUF5A/D clades, and the RDUF1A/D and RDUF4A/D clades duplicated only once, whereas the RDUF3A/2D, RDUF6A/D, and RDUF7A/D clades duplicated twice during cotton evolution. Based on their chromosomal localization, the RDUF genes may have undergone segmental duplication in cotton evolution (Figure 3 and Figure S2). These results indicate that the GhRDUF genes duplicated after the cotton genus diverged from cacao.

The duplicated gene pairs possibly underwent three alternative fates during evolution, including nonfunctionalization, neofunctionalization, and subfunctionalization [56]. Thus, we investigated the expression patterns of the GhRDUF duplicated genes. The diverse expression patterns indicated that the GhRDUF genes have experienced functional diversification. We observed that the GhRDUF2A/3D genes were abundant during cotton growth and development, but its duplicated gene GhRDUF5A/D was barely expressed in the developing ovules or fibers (Figure 6). The GhRDUF2A/3D and GhRDUF7A/D genes had reduced expression levels in different cotton tissues and the developing ovules and fibers, whereas its duplicated gene GhRDUF6A/D had increased expression in many tissues and developing ovules. These results imply that the duplicated GhRDUF genes may have experienced neofunctionalization and subfunctionalization during the evolution of upland cotton.

4.2. RDUF Function in Plants Adapting to Abiotic Stress

RING-containing proteins are key players in plant adaptation to abiotic stress. Many U-box E3 ubiquitin ligases participate in stress management, including TaPUB1 in salt stress [59], CaPUB1 in cold and drought stress [60], and AtPUB48 in thermotolerance response [61]. The RING-type E3 ligase, SDIR1, modulates the salt and drought stress responses via ABA signaling in Arabidopsis [29,30]. The RING-H2 type E3 ligase, OsSIRH2-14, degrades the salt-related protein OsHKT2;1 via the ubiquitin/26S proteasome and enhances salinity tolerance in rice [62]. The function of RING-DUF1117-containing proteins has rarely been reported. Expression analysis revealed that AtRDUF1 is more abundant during cold, heat, and salt stress [63]. AtRDUF1 positively regulates salt stress, and the suppression of AtRDUF1 and AtRDUF2 reduces the plant’s tolerance to ABA-mediated drought stress in Arabidopsis [34,35]. These results indicate that RDUF is involved in the abiotic stress response. Thus, we analyzed the potential role of GhRDUFs in upland cotton’s adaptation to abiotic stress. We detected many cis-elements involved in environmental adaptation in GhRDUF promoter regions: more than four ARE cis-elements were detected in GhRDUF3A/D, GhRDUF5A/D, and GhRDUF6A promoter regions; three STRE elements were found in GhRDUF5D and GhRDUF7A/D promoters; and three WUN-motif elements were found in GhRDUF2D and GhRDUF7A/D promoter regions (Figure 4). The TF-gene regulatory network showed that many stress-related TFs are predicted to regulate GhRDUFs expression, including MYB, C2H2, and Dof (Figure S7). It has been previously reported that ThMYB8 enhanced salt stress tolerance in Tamarix hispida and Arabidopsis [64], a C2H2-type ZFP gene, PeSTZ1, enhances freezing tolerance in Poplar [65], and MdDof54 promotes drought resistance in apples [66]. Thus, we investigated the expression patterns of the GhRDUF genes in response to cold, heat, drought, and salt stress. The GhRDUF7A/D homologous genes responded to cold and heat stress at 3 and 6 h, respectively, and showed increased expression under drought and salt stresses at 24 h, with three STRE elements detected in its promoter regions. In addition, the expression level of GhRDUF3D was upregulated at 1, 6, and 12 h when exposed to drought conditions, and two MBS elements were present in its promoter. These results suggest that the GhRDUF genes participate in cotton’s adaptation to abiotic stress.

4.3. GhRDUF4D Participates in Resistance to V. dahliae

Hormones play a vital role in plant resistance to microorganisms, including pathogenic fungi. JA, SA, and ET are the primary hormones involved in plant inner immunity [6,7,8]. Many cis-elements involved in hormones were detected in the GhRDUF promoter regions (Figure 4). In this study, the expression levels of many GhRDUF genes were increased during hormonal responses (Figure 7). The expression of the GhRDUF2A/D homologous genes was elevated at 3 and 6 h under MeJA conditions, and induced at 12 and 24 h under MeSA conditions. In addition, we observed a decrease in the expression of GhRDUF4A/D, with respect to the MeJA and MeSA responses at many time points (Figure 7). RING-containing proteins have been widely reported to play a substantial role in plant disease resistance [67]. ATL9, a RING zinc finger protein which expression levels are induced by chitin, as well as the RING domain, are important for the resistant phenotype of ATL9 [68,69]. XB3 contains a RING finger motif and displays E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Reduced XB3 expression is involved in resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae pv oryzae [32]. The overexpression of OsPUB41, a rice E3 ubiquitin ligase, enhanced tolerance to Xoo and Rhizoctonia solani infections in rice and Arabidopsis [70]. The mRNA level of RING-H2 type BRH1 had induced rapidly by the pathogen elicitor chitin [71]. The transcript level of another RING-H2 protein, ATL2, was induced after incubation with pathogen elicitors [72]. OsRFPH2-10, a RING-H2 finger E3 ubiquitin ligase, plays a role in the antiviral defense of rice against the rice dwarf virus infection [33]. In cotton, resistance to V. dahliae was shown to improve by the inhibiting of the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of GhPUB17 [73]; however, the role of RING-RDUF1117 in biotic stress remains unclear. In the present study, we observed that the gene expression levels of GhRDUF1A/D, GhRDUF4A/D, and GhRDUF7A/D were elevated upon V. dahliae infection (Figure S7). Consistently, more W-box elements were detected in the GhRDUF1A/D and GhRDUF4A/D promoter regions, particularly in the GhRDUF4D promoter (Figure 4). This result suggests that GhRDUF4D is involved in cotton’s defense to pathogen infection. To verify this speculation, overexpression and the VIGS approach were used to investigate the role of GhRDUF4D under V. dahliae infection. The results revealed that Arabidopsis plants that overexpress GhRDUF4D were more resistant to V. dahliae, and that GhRDUF4D downregulation in cotton plants made them more sensitive to V. dahliae infection, compared with the control.

miRNA regulates target genes in plant development and aids in the plant’s adaptation to the environment. In recent years, miRNAs have been characterized as key players in plants’ responses to pathogens. Because NBS-LRR proteins have been associated with effector-triggered immunity, there is a good correlation between species with large numbers of NBS-LRR genes and those with miR482 superfamily members [74,75]. This result suggests that miR482 plays an important role in plant immunity. Studies have reported that miR482 suppressed Phytophthora and V. dahliae resistance in tomatoes and potatoes [76,77,78]. In cotton, it has been reported that miR482 regulates NBS-LRR defense genes during fungal pathogen infection [79]. In the present study, GhRDUF4D was predicted to be regulated by two miR482 (gra-miR482b and gra-miR482c). Furthermore, gra-miR482c regulated GhRDUF4D at two binding sites, suggesting that GhRDUF4D is regulated by miR482. Hence, a transient transformation assay was performed to examine the regulatory network of GhRDUF4D and gra-miR482c in tobacco leaves. The fluorescent intensity and GFP expression level in GhRDUF4D-GFP and gra-miR482c lanes displayed an apparent reduction compared with the GhRDUF4D-GFP and gra-miR482c-mut lanes (Figure 5). These results indicate that GhRDUF4D might be regulated by gra-miR482c in vivo.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we detected and analyzed RDUF family members in cotton, and elucidated their roles in the biotic and abiotic stress responses. We found that the GhRDUF genes were mostly involved in the stress response, whereas the GhRDUF4D genes were involved in resistance to V. dahliae infections. The findings of this study contribute to the understanding of the RDUF genes in the development of resistant varieties. Moreover, GhRDUF4D might be a vital candidate gene applied for genetic transformation in cotton, or might be a marker gene used for V. dahliae resistance variety selection for cotton breeders.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biom11081145/s1, Figure S1: Phylogenetic tree of RDUF protein family. At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Bn, Brassica napus; Ga, G. arboretum; Gr, G. rai-mondii; Gh, G. hirsutum; Gb, G. barbadense; Gm, Glycine max; Ha, Helianthus annuus; Os, Oryza sativa; Ta, Triticum aes-tivum; Tc, Theobroma cacao; Zm, Zea mays, Figure S2: Phylogenetic tree of RDUF family proteins in G. arboretum, G. raimondii, G. hirsutum, and G. barbadense, respectively, Figure S3: Gene location of RDUFs in G. arboretum, G. raimondii, G. hirsutum, and G. barbadense, Figure S4: The synteny relationship of RDUF genes in G. hirsutum, Figure S5: The conserved motifs identified in RDUF proteins; (A) phylogenetic tree of RDUF proteins; (B) the top ten conserved motifs in RDUF proteins; (C) logos of the ten conserved motifs in RDUF proteins, Figure S6: Amino acid sequences alignment of GhRDUF proteins. The conserved domains were circled by a rectangle with a dotted line; the eight metal ligands were highlighted by a red triangle, Figure S7: The predicted target TFs of GhRDUF genes. The predicted regulation TFs were identified with a yellow background in a circle, the target GhRDUF genes were marked with a blue background in a square. The interaction levels were displayed with different degrees, Figure S8: Expression of GhRDUF4D was induced upon V. dahliae infection. (A) Expression patterns of GhRDUF genes in RNA-Seq data. (B) Expression patterns of GhRDUF4D by the RT-qPCR approach, Figure S9: RT-PCR and RT-qPCR analysis of transgenic Arabidopsis; (A) verification of the transgenic Arabidopsis by reverse transcription PCR. M, DNA Marker 2K plus; #1,#2,#3,#4, transgenic Arabidopsis lines; Col-0, wild type; (B) real-time quantification PCR analysis of the relative expression level of GhRDUF4D in single copy insertion lines. Table S1: Primers used in the present study, Table S2: Identification and nomenclature of RDUF members in other species, Table S3: Ka/Ks ratio of ortholog or paralog gene pairs, Table S4: Annotation of the conserved motifs in RDUF proteins, Table S5: cis-elements predicted in 14 GhRDUF promoter regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-P.Z. and J.-L.S.; formal analysis, Y.-X.H.; investigation, Y.-P.Z., J.-L.S., W.-J.L., N.W. and C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-P.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.-X.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31901578), the Postdoctoral Starting Research Fund of Henan Province (No. 201903001), and State Key Laboratory of Cotton Biology Open Fund (CB2020A14).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Li F., Fan G., Lu C., Xiao G., Zou C., Kohel R.J., Ma Z., Shang H., Ma X., Wu J., et al. Genome sequence of cultivated Upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum TM-1) provides insights into genome evolution. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:524–530. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu Y., Chen J., Fang L., Zhang Z., Ma W., Niu Y., Ju L., Deng J., Zhao T., Lian J., et al. Gossypium barbadense and Gossypium hirsutum genomes provide insights into the origin and evolution of allotetraploid cotton. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:739–748. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0371-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang G., Wu Z., Percy R.G., Bai M., Li Y., Frelichowski J.E., Hu J., Wang K., Yu J.Z., Zhu Y. Genome sequence of Gossypium herbaceum and genome updates of Gossypium arboreum and Gossypium hirsutum provide insights into cotton A-genome evolution. Nat. Genet. 2020;52:516–524. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0607-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang C.L., Liang S., Wang H.Y., Han L.B., Wang F.X., Cheng H.Q., Wu X.M., Qu Z.L., Wu J.H., Xia G.X. Cotton major latex protein 28 functions as a positive regulator of the ethylene responsive factor 6 in defense against Verticillium dahliae. Mol. Plant. 2015;8:399–411. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu Q., Zhu L., Zhang X., Guan Q., Xiao S., Min L., Zhang X. GhCPK33 negatively regulates defense against Verticillium dahliae by phosphorylating GhOPR3. Plant Physiol. 2018;178:876–889. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaban M., Miao Y., Ullah A., Khan A.Q., Menghwar H., Khan A.H., Ahmed M.M., Tabassum M.A., Zhu L. Physiological and molecular mechanism of defense in cotton against Verticillium dahliae. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018;125:193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J., Hu H.L., Wang X.N., Yang Y.H., Zhang C.J., Zhu H.Q., Shi L., Tang C.M., Zhao M.W. Dynamic infection of Verticillium dahliae in upland cotton. Plant Biol. 2020;22:90–105. doi: 10.1111/plb.13037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long L., Xu F.C., Zhao J.R., Li B., Xu L., Gao W. GbMPK3 overexpression increases cotton sensitivity to Verticillium dahliae by regulating salicylic acid signaling. Plant Sci. 2020;292:110374. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.110374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu N., Sun Y., Pei Y., Zhang X., Wang P., Li X., Li F., Hou Y. A pectin methylesterase inhibitor enhances resistance to Verticillium wilt. Plant Physiol. 2018;176:2202–2220. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y., Wu L., Wang X., Chen B., Zhao J., Cui J., Li Z., Yang J., Wu L., Wu J., et al. The cotton laccase gene GhLAC15 enhances Verticillium wilt resistance via an increase in defence-induced lignification and lignin components in the cell walls of plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2019;20:309–322. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y., Jin Y., Gong Q., Li Z., Zhao L., Han X., Zhou J., Li F., Yang Z. Mechanismal analysis of resistance to Verticillium dahliae in upland cotton conferred by overexpression of RPL18A-6 (Ribosomal Protein L18A-6) Ind. Crop. Prod. 2019;141:111742. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Y., Sun L., Wassan G.M., He X., Shaban M., Zhang L., Zhu L., Zhang X. GbSOBIR1 confers Verticillium wilt resistance by phosphorylating the transcriptional factor GbbHLH171 in Gossypium barbadense. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019;17:152–163. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen B., Zhang Y., Yang J., Zhang M., Ma Q., Wang X., Ma Z. The G-protein a subunit GhGPA positively regulates Gossypium hirsutum resistance to Verticillium dahliae via induction of SA and JA signaling pathways and ROS accumulation. Crop J. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2020.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smalle J., Vierstra R.D. The ubiquitin 26S proteasome proteolytic pathway. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004;55:555–590. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraft E., Stone S.L., Ma L., Su N., Gao Y., Lau O.S., Deng X.W., Callis J. Genome analysis and functional characterization of the E2 and RING-type E3 ligase ubiquitination enzymes of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:1597–1611. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.067983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glickman M.H., Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: Destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:373–428. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dye B.T., Schulman B.A. Structural mechanisms underlying posttranslational modification by ubiquitin-like proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2007;36:131–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter T. The age of crosstalk: Phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and beyond. Mol. Cell. 2007;28:730–738. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosarev P., Mayer K.F., Hardtke C.S. Evaluation and classification of RING-finger domains encoded by the Arabidopsis genome. Genome Biol. 2002;3:research0016. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-4-research0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freemont P.S. The RING finger: A novel protein sequence motif related to the zinc finger. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1993;684:174–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb32280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Callis J. The ubiquitination machinery of the ubiquitin system. Arabidopsis B. 2014;12:e0174. doi: 10.1199/tab.0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lorick K.L., Jensen J.P., Fang S., Ong A.M., Hatakeyama S., Weissman A.M. RING fingers mediate ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2)-dependent ubiquitination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:11364–11369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freemont P.S., Hanson I.M., Trowsdale J. A novel cysteine-rich sequence motif. Cell. 1991;64:483–484. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90229-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lovering R., Hanson I.M., Borden K.L., Martin S., O’Reilly N.J., Evan G.I., Rahman D., Pappin D.J., Trowsdale J., Freemont P.S. Identification and preliminary characterization of a protein motif related to the zinc finger. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:2112–2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone S.L., Hauksdóttir H., Troy A., Herschleb J., Kraft E., Callis J. Functional analysis of the RING-type ubiquitin ligase family of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;137:13–30. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.052423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang D., Guo Y., Wu C., Yang G., Li Y., Zheng C. Genome-wide analysis of CCCH zinc finger family in Arabidopsis and rice. BMC Genom. 2008;9:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao Y., Li M.Y., Zhao J., Zhang Y.C., Xie Q.J., Chen D.H. Genome-wide analysis of RING finger proteins in the smallest free-living photosynthetic eukaryote Ostreococus tauri. Mar. Genomics. 2016;26:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.margen.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alam I., Yang Y.Q., Wang Y., Zhu M.L., Wang H.B., Chalhoub B., Lu Y.H. Genome-wide identification, evolution and expression analysis of RING finger protein genes in Brassica rapa. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:40690. doi: 10.1038/srep40690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y., Yang C., Li Y., Zheng N., Chen H., Zhao Q., Gao T., Guo H., Xie Q. SDIR1 is a RING finger E3 ligase that positively regulates stress-responsive abscisic acid signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:1912–1929. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang H., Cui F., Wu Y., Lou L., Liu L., Tian M., Ning Y., Shu K., Tang S., Xie Q. The RING finger ubiquitin E3 ligase SDIR1 targets SDIR1-INTERACTING PROTEIN1 for degradation to modulate the salt stress response and ABA signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2015;27:214–227. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.134163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheung M.Y., Zeng N.Y., Tong S.W., Li F.W., Zhao K.J., Zhang Q., Sun S.S., Lam H.M. Expression of a RING-HC protein from rice improves resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2007;58:4147–4159. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y.S., Pi L.Y., Chen X., Chakrabarty P.K., Jiang J., De Leon A.L., Liu G.Z., Li L., Benny U., Oard J., et al. Rice XA21 binding protein 3 is a ubiquitin ligase required for full Xa21-mediated disease resistance. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3635–3646. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.046730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu L., Jin L., Huang X., Geng Y., Li F., Qin Q., Wang R., Ji S., Zhao S., Xie Q.I., et al. OsRFPH2-10, a ring-H2 finger E3 ubiquitin ligase, is involved in rice antiviral defense in the early stages of rice dwarf virus infection. Mol. Plant. 2014;7:1057–1060. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssu007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J., Han Y., Zhao Q., Li C., Xie Q., Chong K., Xu Y. The E3 ligase AtRDUF1 positively regulates salt stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e71078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim S.J., Ryu M.Y., Kim W.T. Suppression of Arabidopsis RING-DUF1117 E3 ubiquitin ligases, AtRDUF1 and AtRDUF2, reduces tolerance to ABA-mediated drought stress. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;420:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.02.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Libault M., Wan J., Czechowski T., Udvardi M., Stacey G. Identification of 118 Arabidopsis transcription factor and 30 ubiquitin-ligase genes responding to chitin, a plant-defense elicitor. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2007;20:900–911. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-8-0900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Du X., Huang G., He S., Yang Z., Sun G., Ma X., Li N., Zhang X., Sun J., Liu M., et al. Resequencing of 243 diploid cotton accessions based on an updated A genome identifies the genetic basis of key agronomic traits. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:796–802. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paterson A.H., Wendel J.F., Gundlach H., Guo H., Jenkins J., Jin D., Llewellyn D., Showmaker K.C., Shu S., Udall J., et al. Repeated polyploidization of Gossypium genomes and the evolution of spinnable cotton fibres. Nature. 2012;492:423–427. doi: 10.1038/nature11798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu J., Jung S., Cheng C.H., Ficklin S.P., Lee T., Zheng P., Jones D., Percy R.G., Main D. CottonGen: A genomics, genetics and breeding database for cotton research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D1229–D1236. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Duvaud S., Wilkins M.R., Appel R.D., Bairoch A. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy server. In: Walker J.M., editor. The Proteomics Protocols Handbook. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ, USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lescot M., Déhais P., Thijs G., Marchal K., Moreau Y., Van de Peer Y., Rouzé P., Rombauts S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Letunic I., Bork P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v4: Recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W256–W259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu B., Jin J., Guo A.Y., Zhang H., Luo J., Gao G. GSDS 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1296–1297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Letunic I., Bork P. 20 years of the SMART protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D493–D496. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen C., Chen H., Zhang Y., Thomas H.R., Frank M.H., He Y., Xia R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant. 2020;13:1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bailey T.L., Boden M., Buske F.A., Frith M., Grant C.E., Clementi L., Ren J., Li W.W., Noble W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Voorrips R.E. MapChart: Software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 2002;93:77–78. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y., Tang H., Debarry J.D., Tan X., Li J., Wang X., Lee T.H., Jin H., Marler B., Guo H., et al. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krzywinski M., Schein J., Birol I., Connors J., Gascoyne R., Horsman D., Jones S.J., Marra M.A. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pertea M., Kim D., Pertea G.M., Leek J.T., Salzberg S.L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 2016;11:1650–1667. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tian F., Yang D.C., Meng Y.Q., Jin J., Gao G. PlantRegMap: Charting functional regulatory maps in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D1104–D1113. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dai X., Zhuang Z., Zhao P.X. psRNATarget: A plant small RNA target analysis server (2017 release) Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W49–W54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N.S., Wang J.T., Ramage D., Amin N., Schwikowski B., Ideker T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu S., Sun R., Zhang X., Feng Z., Wei F., Zhao L., Zhang Y., Zhu L., Feng H., Zhu H. Genome-wide analysis of OPR family genes in cotton identified a role for GhOPR9 in Verticillium dahliae resistance. Genes. 2020;11:1134. doi: 10.3390/genes11101134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao Y., Guo A., Wang Y., Hua J. Evolution of PEPC gene family in Gossypium reveals functional diversification and GhPEPC genes responding to abiotic stresses. Gene. 2019;698:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2019.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruan W., Guo M., Wang X., Guo Z., Xu Z., Xu L., Zhao H., Sun H., Yan C., Yi K. Two RING-finger ubiquitin E3 ligases regulate the degradation of SPX4, an internal phosphate sensor, for phosphate homeostasis and signaling in rice. Mol. Plant. 2019;12:1060–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cao H., Li X., Wang Z., Ding M., Sun Y., Dong F., Chen F., Liu L., Doughty J., Li Y., et al. Histone H2B monoubiquitination mediated by HISTONE MONOUBIQUITINATION1 and HISTONE MONOUBIQUITINATION2 is involved in anther development by regulating tapetum degradation-related genes in rice. Plant Physiol. 2015;168:1389–1405. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.256578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang W., Wang W., Wu Y., Li Q., Zhang G., Shi R., Yang J., Wang Y., Wang W. The involvement of wheat U-box E3 ubiquitin ligase TaPUB1 in salt stress tolerance. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020;62:631–651. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Min H.J., Jung Y.J., Kang B.G., Kim W.T. CaPUB1, a hot pepper U-box E3 ubiquitin ligase, confers enhanced cold stress tolerance and decreased drought stress tolerance in transgenic rice (Oryza sativa L.) Mol. Cells. 2016;39:250–257. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2016.2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peng L., Wan X., Huang K., Pei L., Xiong J., Li X., Wang J. AtPUB48 E3 ligase plays a crucial role in the thermotolerance of Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019;509:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.12.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Park Y.C., Lim S.D., Moon J.C., Jang C.S. A rice really interesting new gene H2-type E3 ligase, OsSIRH2-14, enhances salinity tolerance via ubiquitin/26S proteasome-mediated degradation of salt-related proteins. Plant Cell Environ. 2019;42:3061–3076. doi: 10.1111/pce.13619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Inzé A., Vanderauwera S., Hoeberichts F.A., Vandorpe M., Van Gaever T., Van Breusegem F. A subcellular localization compendium of hydrogen peroxide-induced proteins. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35:308–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu Z.Y., Li X.P., Zhang T.Q., Wang Y.Y., Wang C., Gao C.Q. Overexpression of ThMYB8 mediates salt stress tolerance by directly activating stress-responsive gene expression. Plant Sci. 2021;302:110668. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.He F., Li H.G., Wang J.J., Su Y., Wang H.L., Feng C.H., Yang Y., Niu M.X., Liu C., Yin W., et al. PeSTZ1, a C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factor from Populus euphratica, enhances freezing tolerance through modulation of ROS scavenging by directly regulating PeAPX2. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019;17:2169–2183. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen P., Yan M., Li L., He J., Zhou S., Li Z., Niu C., Bao C., Zhi F., Ma F., et al. The apple DNA-binding one zinc-finger protein MdDof54 promotes drought resistance. Hortic. Res. 2020;7:195. doi: 10.1038/s41438-020-00419-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ning Y., Wang R., Shi X., Zhou X., Wang G.L. A layered defense strategy mediated by rice E3 ubiquitin ligases against diverse pathogens. Mol. Plant. 2016;9:1096–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berrocal-Lobo M., Stone S., Yang X., Antico J., Callis J., Ramonell K.M., Somerville S. ATL9, a RING zinc finger protein with E3 ubiquitin ligase activity implicated in chitin- and NADPH oxidase-mediated defense responses. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e14426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Deng F., Guo T., Lefebvre M., Scaglione S., Antico C.J., Jing T., Yang X., Shan W., Ramonell K.M. Expression and regulation of ATL9, an E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in plant defense. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0188458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kachewar N.R., Gupta V., Ranjan A., Patel H.K., Sonti R.V. Overexpression of OsPUB41, a Rice E3 ubiquitin ligase induced by cell wall degrading enzymes, enhances immune responses in rice and Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:530. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-2079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Molnár G., Bancoş S., Nagy F., Szekeres M. Characterisation of BRH1, a brassinosteroid-responsive RING-H2 gene from Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2002;215:127–133. doi: 10.1007/s00425-001-0723-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Serrano M., Guzmán P. Isolation and gene expression analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana mutants with constitutive expression of ATL2, an early elicitor-response RING-H2 zinc-finger gene. Genetics. 2004;167:919–929. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.028043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Qin T., Liu S., Zhang Z., Sun L., He X., Lindsey K., Zhu L., Zhang X. GhCyP3 improves the resistance of cotton to Verticillium dahliae by inhibiting the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of GhPUB17. Plant Mol. Biol. 2019;99:379–393. doi: 10.1007/s11103-019-00824-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.González V.M., Müller S., Baulcombe D., Puigdomènech P. Evolution of NBS-LRR gene copies among dicot plants and its regulation by members of the miR482/2118 superfamily of miRNAs. Mol. Plant. 2015;8:329–331. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Canto-Pastor A., Santos B.A.M.C., Valli A.A., Summers W., Schornack S., Baulcombe D.C. Enhanced resistance to bacterial and oomycete pathogens by short tandem target mimic RNAs in tomato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:2755–2760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1814380116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang L., Mu X., Liu C., Cai J., Shi K., Zhu W., Yang Q. Overexpression of potato miR482e enhanced plant sensitivity to Verticillium dahliae infection. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2015;57:1078–1088. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.de Vries S., Kukuk A., von Dahlen J.K., Schnake A., Kloesges T., Rose L.E. Expression profiling across wild and cultivated tomatoes supports the relevance of early miR482/2118 suppression for Phytophthora resistance. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2018;285:20172560. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]