Abstract

Background:

The National Planning Policy Framework advocates the promotion of ‘healthy communities’. Controlling availability and accessibility of hot food takeaways is a strategy which the planning system may use to promote healthier environments. Under certain circumstances, for example, local authorities can reject applications for new hot food takeaways. However, these decisions are often subject to appeal. The National Planning Inspectorate decide appeals – by upholding or dismissing cases. The aim of this research is to explore and examine the National Planning Inspectorate’s decision-making.

Methods:

The appeals database finder was searched to identify hot food takeaway appeal cases. Thematic analysis of appeals data was carried out. Narrative synthesis provided an overview of the appeals process and explored factors that were seen to impact on the National Planning Inspectorate’s decision-making processes.

Results:

The database search identified 52 appeals cases. Results suggest there is little research in this area and the appeals process is opaque. There appears to be minimal evidence to support associations between the food environment and health and a lack of policy guidance to inform local planning decisions. Furthermore, this research has identified non-evidence-based factors that influence the National Planning Inspectorate’s decisions.

Conclusion:

Results from this research will provide public health officers, policy planners and development control planners with applied public health research knowledge from which they can draw upon to make sound decisions in evaluating evidence to ensure they are successfully equipped to deal with and defend hot food takeaway appeal cases.

Keywords: public health policy, public health, obesity, health policy, environment

Introduction

Literature review

Links between planning and health

In recent years, there has been a significant move to reunite planning and health in England.1 This has been closely associated with two key changes at a national level. In terms of planning, the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) makes explicit the need to promote healthy communities, including issues such as ‘access to healthier food’.2,3 Furthermore, the Health and Care Act transferred responsibility for public health to upper-tier local authorities.

The UK planning system, however, is designed to reconcile the many, often conflicting, interests that are inherent in the development of land. As such, control of development is not as central to planning in the UK as might be assumed, and key principles of negotiation, mediation and discretion come into play. At local-level, plans, generically termed the ‘Development Plan’ for the area, comprising the Local Plan, any neighbourhood plans and other spatial strategies, are required to be in general conformity with the NPPF. The suite of plan documents guide development but are not a ‘blueprint’ for what will and will not happen. Moreover, while there is primacy of the Development Plan, other ‘material considerations’ will be taken into account in all planning decision-making.

Evidence that urban planning is implicated in contemporary health problems has existed for some time. In relation to obesity, for example, the Foresight report Tackling obesities, future choices4 highlighted the emerging evidence around the built and food environments.5 Moving forward, guidance and Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) documentation is now emerging which hopes to provide practical support for local authorities who wish to use the planning system to address public health issues such as obesity.6

Neighbourhood food environments and hot food takeaways

The environments in which we spend our daily lives influence what, when and where we choose to eat. This can be further broken down into five issues of availability, accessibility, affordability, acceptability and accommodation.7 Clearly some of these issues are out with the scope of the planning system, but availability and accessibility are issues, which at least to some extent, the system has control over. Access and availability of food for both home and out-of-home consumption might be defined as the neighbourhood food environment, a combination of retail outlets (from small shops to supermarkets) as well as cafes, takeaways and restaurants.8 In England, food outlets fall into different categories in terms of urban planning (see below); however, only hot food takeaways (HFTs) have their own specific category; therefore, the review of evidence focuses on this category of outlet. One issue that is important to consider is total exposure to fast-food availability, in other words the environments where we work, or go to school and those we travel through in our daily lives as well as where we live.7,9

Evidence suggests that individuals do not make informed decisions regarding the healthfulness of food.10 There are a complex synergy of determinants which surround food choice, of which the environment and proximity to HFTs are contributing factors.11 Residing within areas which are abundant in HFT outlets increases the likelihood of individuals accessing unhealthy food.12,13 In addition, those who make purchases from HFTs are also more likely to do so on a frequent basis.11,14–16 Overcoming obstacles, such as distance to make HFT purchases, is becoming more common, particularly in young adults. Recent studies carried out with secondary school-aged children in both London and Newcastle upon Tyne indicated that young people reported travelling significant distances within school lunch breaks to obtain an HFT meal from their preferred establishment.14–16 Taxi and bus rides were stated as a means to facilitate consumption of such purchases and illustrate the lengths some will go to, in order to acquire the food they desire, irrespective of health consequences.

Reviews of takeaway fast-food access have been somewhat equivocal, with some studies finding a significant relationship between access and diet, while others have failed to do so.11,17,18

One aspect that seems to attract broad consensus among researchers is around takeaway food, nutrition and social deprivation. Food served within takeaways tends to be nutritionally poor and energy dense.19 Research has also shown that takeaway outlets cluster in areas of social deprivation20,21 and of concern the trend of socioeconomic disparity and in takeaway food outlet density seems to be increasing.20 Moreover, research on socioeconomic status (SES) and fast-food consumption suggests that there is an exaggerated impact on lower SES groups from exposure to fast-food outlets. In this study, lower SES groups consumed more fast food, tended to have higher body weight and were more likely to be obese.22

Analysis of cross-sectional data from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey (2008–1012) explored the frequency and socio-demographic correlates of eating meals out and takeaway meals at home. Results indicated that one-fifth to one-quarter of individuals ate meals that were prepared out of home on a weekly basis. Moreover, the proportion of participants eating both meals out and takeaway meals at home at least weekly increased considerably in young adults (aged 19–29 years). In addition, in adults, affluence was positively correlated with consumption. However, similar correlations were seen for children living in less affluent areas.23

Regulation of HFTs (A5) through SPD and policy

The Town and Country Planning (Use Classes) Order 1987 (as amended) places various uses of land and buildings into ‘use classes’; this is in order to control change between one use and another or to control particular uses in specific areas. Shops, including food shops, are class A1 and this covers everything from small independent corner shops and sandwich shops, through to the largest 24-h supermarket outlets. A3 restaurants and cafes also cover a wide range of establishments from an independent vegan wholefood café, to a multinational fast-food chain, as long as a significant provision for on-site consumption is provided. This topic is returned to in the ‘Limitations’ section.

The Order is amended periodically and a specific ‘A5’ HFT was introduced in 2005. Control of use classes in specific areas may be part of the planning policy, as part of the Local Plan, or as guidance produced as SPDs which either include issues too detailed to go into the core policy or where rapid response is required to an emerging issue. Policy carries more weight in planning decision-making than guidance, but an issue such as controlling fast-food outlets might require both. The earliest SPD aimed at controlling fast-food proliferation was focused on nuisance and antisocial behaviour associated with HFTs (Waltham Forest); however, in 2010, the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham produced their SPD ‘Saturation Point’ which gave weight to health impacts and evidenced public health and nutrition research.24 A recent census of all of England’s local government areas (n = 325) found that 164 (50.5%) areas had a policy that focused on takeaway food outlets, while 56 (34.1%) focused on health.25

Planning appeals

Planning policies and/or guidance that aim to restrict the opening of new HFTs can be used by local planning officers to reject new planning applications for this use. In doing so, they consider whether their case is robust enough to argue at appeal. Applicants have a right to appeal the local authority decision and do so by lodging an appeal with the National Planning Inspectorate (https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/planning-inspectorate/about) (PINS); in these cases, they are referred to as the appellant. Many appeals involving HFTs are decided under a process known as ‘written representations’; in other words, the inspector will gather all the evidence together in the form of written statements from the appellant, the local planning authority (LPA) and anyone else who has an interest in the appeal. Each party has the opportunity to comment on each other’s statements, without making any verbal submissions. However, a hearing or inquiry may also be held. Hearings are relatively informal, essentially a round table discussion led by the inspector, where people can put their case across and respond to the inspector’s questions. A hearing is a much more formal process where parties present their case and witnesses are questioned by the inspector and the other parties as to the evidence that they have presented.

Inspectors decide appeals on a case-by-case basis. Procedure is tightly prescribed, so in reaching their decision, they should consider any material submitted to the LPA regarding the case; all the appeal documents; any relevant legislation and policies, including changes to legislation; any new Government policy or guidance; and any new or emerging development plan policies since the LPA’s decision was issued; finally, they may include any other matters that they consider material to the appeal. Appeals will either be upheld, in which case the inspector finds in favour of the appellant and overturns the original local authority decision, or dismissed, in which case the inspector finds in favour of the local authority. It should be noted that planning appeals encompass a vast array of matters, for example, environmental issues, highway safety, design and health to name but a few diverse topics. At present, Planning Inspectors are not required to hold any special qualifications and/or receive instruction in relation to any of these specialist subjects, and it might be questioned, therefore, whether there is adequate training. While inspectors will have a vast amount of experience to draw on, given the relatively recent increased emphasis on health, their knowledge of this field in relation to planning may be quite limited.

While we are aware nationally of a number of appeals around HFTs, and the appeals procedure is clearly prescribed,22 there has been little systematic research in relation to decision-making in this area.

Aims

The aim of this research was to explore the appeals process further by examining influences, including barriers and facilitators to the inspectorate’s decision to either uphold or dismiss cases.

Methods

In May 2018, a 1-day seminar was held examining the control of proliferation of A5 uses by the planning system. This included a half-day workshop for planning and public health practitioners, who had either already produced guidance/policy on this topic or were in the process of doing so. Some of the practitioners had experience of HFT appeals which was particularly valuable to the study. Findings from the discussions in this workshop are not presented in this article, but contributed to the design of this study.

Data from the appeals database were analysed using a thematic content analysis approach, building on our discussions with practitioners.26 This aimed to identify commonalities and differences in the data, prior to focusing on relationships between different parts of the data, thereby seeking to draw descriptive and/or explanatory conclusions clustered around analytical themes. Interpretation of the data into analytical themes allowed for relationships between themes to be identified and proved useful in determining whether or not themes were barriers or facilitators to the National Planning Inspectorate’s decision-making processes. Narrative synthesis of evidence generated will be discussed to provide an overview of the appeals process and explore factors that may potentially impact on decisions made.

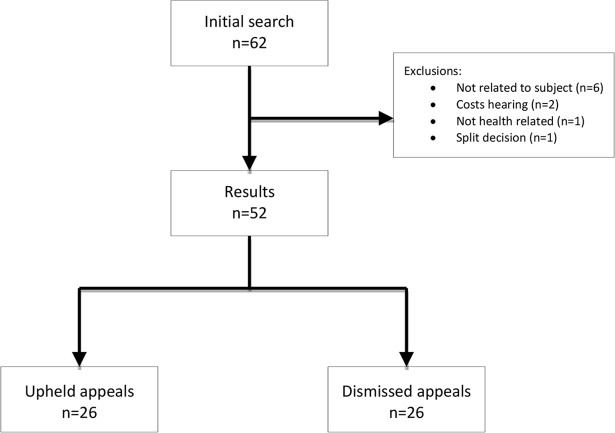

In June 2018, the database Appeals Finder (https://www.gov.uk/appeal-planning-inspectorate) was searched for planning appeals related to obesity, health and fast food. Appeals Finder indexes over 160,000 planning appeal decisions from all of England and Wales from 2010 onwards. We searched using the keywords ‘A5’ AND ‘food’ AND ‘obesity’ which generated 62 results. After assessing the titles and brief detail of each result, 52 results were retained for further assessment (Figure 1). All documents linked to the 52 results were saved. Textual information in terms of evidence that may impact on the decision-making processes within each case was obtained from the database and examined for recurring themes using a framework approach.26

Figure 1.

Results from Appeals Finder database search.

Results

Appeals cases

Of the 52 appeals cases, 26 were upheld (local decision over-turned and Planning Inspector (PI) found in favour of the business) and 26 dismissed (i.e. permission not given to the HFT). Of those that were dismissed, 23 were independent stores and 3 were multinational chain retailers. Similarly, of those that were upheld, 22 related to independent stores and 4 were multinational chain retailers.

Regions with the most appeal cases were London (n = 17) and the North East of England (n = 10). In London, 35% of cases were dismissed (i.e. permission not given to the HFT) as opposed to 60% in the North East. The majority of inspectors (>94%) were male. A total of 23 different named inspectors were responsible for making the 26 upheld decisions with three of those being assigned to two cases and the remainder only one. Similarly, there were 24 different named inspectors who were responsible for the 26 dismissed cases with two being assigned two cases and the remainder only one. Six of the inspectors were involved in both upheld and dismissed cases. There were a number of themes identified as having an impact on the appeals decision-making process and many were common to both upheld and dismissed appeals.

Finding 1: appeals upheld (i.e. planning permission granted to HFT)

Non-evidence-based decisions

It is to be expected that the quasi-legal procedure of appeals would be based on evidence, very much as case in law. Overall, however, while PINS would argue that inspectors make difficult decisions based on professional judgement, as outlined below, some decisions at least seemed to be largely based on un-evidenced statements, rather than being supported by any current academic/health evidence and/or policy.

In many appeals upheld, inspectors stated that the ‘evidence’ provided to them regarding HFTs and health impacts, such as obesity prevalence, was insufficient to guide their decision-making:

There is also little substantive evidence before me that would lead me to conclude that the location of the proposal would have a direct correlation with childhood obesity. (ID 20)

As outlined in the introduction, evidence between fast-food consumption and childhood obesity does exist, but in this case, the evidence presented in the statement from the LPA was not deemed substantive. However, the precise reason that evidence was deemed deficient, in this case and in other similar cases, is generally unclear. For example,

Accordingly, I conclude that the principle of the use would be acceptable … while any conflict with the SPD would not warrant a refusal of the proposal. (ID 11)

Despite the existence of an SPD, clearly little weight is afforded to it, but again why is unclear.

Another issue was that there appeared to be a disconnect between what inspectors believed to be enforceable, as opposed to what practitioners suggested in the seminar is realistically achievable once an appeal has been upheld and granted. For example, there are instances of upheld appeals with inspectorate recommendations that the HFT establishments should consider opening hours that do not make unhealthy foods easily accessible to children attending local schools. These are clearly to inform planning conditions imposed on the permission; however, the extent to which they are enforceable may be questioned. LPA enforcement is often under severe pressure. Moreover, unlike a structure that is built without planning permission, for example, opening hours are arguably much trickier to monitor:

Takeaway permission granted – however conditions applied to opening hours ‘The X Collegiate, which educates teenagers of secondary school age, is well within the 400m threshold identified for the purposes of conditioning opening hours to prevent ready attraction of children of secondary school age at lunch-time’. (ID 50)

Again, while PINS would undoubtedly point to the vast experience and knowledge that inspectors bring to appeals cases, there was evidence of less than ideal practice in some cases. For example, the reasoning and text to support two quite different appeals that were upheld within one region, one day apart, consisted of an identical concluding statement by the inspector. The appropriateness of such ‘cut and pasting’ when decisions are supposed to be individually considered might be questioned. It could suggest a lack of assessment rigour or point to an under-resourced system under strain where the odd corner is taken by hard-pressed professionals. Whatever the reason, it does call into question the overall integrity of the decision-making process.

Impact on health

A number of decisions relating to cases upheld were made based on the assertion that the impact of HFTs on obesity was minimal and therefore had little impact on health:

Very little substantiated or objective evidence has been presented to show conclusively that the presence of the proposed restaurant [large retail chain restaurant] and takeaway would be ‘likely to influence behaviour harmful to health or the promotion of healthy lifestyles’. (ID 56)

Some of these decisions had a somewhat dismissive tone about the association between HFTs and obesity. For example, statements from inspectors indicated that they believed the planning department was not responsible for decisions that would have an impact on health issues such as obesity, which would certainly seem to run counter to the spirit of the NPPF. Others ranked the importance of obesity below other issues that were provided as justifiable reasons for case dismissal, for example, noise, rubbish, car parking:

Although proposals for new takeaway facilities can legitimately be refused on grounds of amenity, car parking, noise and loss of retail facilities, etc., it is acknowledged that questions of obesity and unhealthy living are insufficient on their own to refuse planning permission. (ID 1)

In this case it is unclear whether the inspector’s position is based on the evidence presented in the appeal, or whether they believe this to be the case more generally.

Other inspectors stated that the addition of one more takeaway would not be influential enough to have an impact on health in general, inequalities, obesity and the creation of healthier neighbourhoods:

The Council raises a concern about allowing a further hot food takeaway outlet in respect of the health implications relating to obesity levels within the local community. However, I have received insufficient evidence that the addition of this single outlet would be a material exacerbating factor, particularly as there is a wide choice of food retail outlets in the area available to local residents.

Further cases suggested there was no evidence that takeaways encourage unhealthy eating (ID15), two cases that the location of the HFT did not directly correlate or was linked directly to childhood obesity (ID20 and ID54) and a further three cases which stated there was no evidence to suggest a direct link between HFT provision and childhood obesity (ID26, ID45 and ID46). With all of the above issues, there is a wealth of evidence available, but it may not be in a form that is easily translated to individual cases:

The site is located near to several schools and rates of childhood obesity are particularly high in X (location). However, there is no detailed evidence before me to demonstrate a causal link between this issue and the provision of takeaway establishments. (ID 45)

Although it was acknowledged that an unhealthy diet could potentially affect health, this was sometimes outweighed by other factors which were deemed equally or more important such as providing a variety of food options:

The concern is that an unbalanced diet, perhaps combined with insufficient exercise, over-reliant for example on meals with high fat and salt content, will be unhealthy, even dangerous, over a period of time. This consideration needs to be balanced against the desirable ability for individuals, including adults, to have a range and choice of eating options which might include occasional take-away meals, saving them time and causing them no harm. (ID 29)

In this case, one might seriously question what evidence the inspector is basing their decision on. How do they support their assertion that the desirability of having a range of eating options, including takeaways, outweighs the possible harm they may cause? As far as the authors are aware, there is no robust evidence to support this claim.

Parental control

The issue of parental control and responsibility was also cited several times as being an important factor when discussing accessibility of HFTs to children. When assessing the location, distance and ease of access of takeaways to school children and its’ impact on health, several inspectors felt that parents should be held wholly responsible. This was particularly true for cases involving younger children attending local primary schools as it was assumed that these children walked to and from school accompanied by their parents. It was also felt that it was the parent’s responsibility to influence and steer their child’s food choice:

Any potential effect on the health of school children is a material consideration. However, I am mindful that children of primary school age would mostly be accompanied by an adult, who are able to guide food choices. (ID 47)

The assumption of parental responsibility also held true in cases where children were free to leave school premises at lunchtime although there was no evidence given to support this:

Whilst I note the evidence that the primary school does allow children to leave the premises at lunchtimes, I consider that primary school children would usually be accompanied by and be under the supervision and responsibility of parents or carers when travelling to and from school. Therefore, at these times, the primary school children would be under the responsibility of adults and would not have unfettered access to the takeaway. (ID 5)

Again, in these cases, there is no robust evidence to support the assertions made by the inspectors. For example, in the UK, there is no minimum legal age for child to walk to school unaccompanied and younger children may be accompanied by an older sibling (the most at-risk group to HFT exposure) rather than a parent.

Economic argument

Having a blanket ban on HFTs, even within areas that have an obesity prevalence rate higher than 10%, was perceived to be detrimental to the local economy by some planning inspectors. In some cases, inspectors perceived that HFTs supported other local businesses and provided additional employment opportunities for local people:

I find the harm to the emerging policy insufficient to outweigh the requirements of the Framework to support a growing economy and the positive, albeit small, contribution the proposal would make to local job creation. (ID 31)

Others felt that the positive local economic impact that the proposed HFT would offer prevailed over any detrimental concerns such as excessive proliferation of HFT establishments and financial impact on other businesses:

Whilst I acknowledge that there are other fast food retailers in the area and a perceived lack of need for similar uses, the appellant is content that the proposed businesses are viable and this matter does not outweigh the support for the scheme that I have found. Nor does the potential for increased competition with other businesses given that the development would contribute to the local economy. (ID 37)

Here, once again the evidence that inspectors are using to support the economic case is somewhat unclear. In terms of alcohol sales, for example, some analysis has shown that benefits to the local economy are outweighed by additional cost to local health service provision, but as far as the authors are aware, no such similar cost–benefit analysis has been carried out on HFTs.

Opening hours

The suggestion of HFTs considering time restrictions on opening hours, so they do not fall within school start, finish and break times, was made in four cases. In these cases, inspectors believed that if opening hours were limited, this would solve the problem of children visiting and purchasing unhealthy food from these establishments. They made assumptions that restrictions on opening hours would be easily enforceable and could be applied for various times such as in school holiday and term time:

Takeaway permission granted but with restrictions on hours – consider a condition restricting term time opening of the proposal to be necessary to prevent potential harm arising from children’s access to unhealthy foods. (ID 17)

However, as already stated, the practicalities of enforcement at a time when many LPA services are under pressure are unclear.

Disputing facts

Finally, factual evidence which had been included in LPA statements, and therefore should have provided robust grounds for dismissal, was disputed by the PI in a number of cases. For some, this related to the distance that the schools were located from the proposed HFT, concentration of HFT outlets within the local area and the weight, relevance and availability of local policy and/or guidance:

My attention has been drawn to the links between takeaway food and poor health generally and child obesity in particular. However, I do not consider such matters would constitute a reason to dismiss the appeal in the absence of definitive Government planning guidance and development plan policies on the issue. (ID 43)

In another example, information provided by the appellant was considered when making decisions in relation to proximity of the HFT to the local school when assessing health impacts:

It has been identified that some pupils of the local school are likely to pass by the site and I note concerns that the development would encourage unhealthy eating habits and contribute to child obesity. However, the school is around 800m from the site according to the appellant and the development would not be located in the immediate environs of the school where pupils would be encouraged to visit on a regular basis. The fact that some pupils may choose to frequent the proposed businesses would not significantly impact on local health. (ID 37)

Here, what the inspector’s decision seems to hinge on the appellant’s statement is that 800 m was too far for children to access the HFT. However, Brighton and Hove’s impact study ‘HFTs near schools’ found that pupils regularly travelled farther than 800 m during lunchtimes to visit their favourite hot food outlets and also observed that fast-food purchase was linked to other unhealthy behaviour such as smoking.27 Therefore, not only is the decision based on an assumption that is un-evidenced, but it is also factually incorrect.

Finding 2: appeals dismissed (i.e. the local decision is maintained, and planning permission for HFT is denied)

Decisions made that resulted in a case being dismissed (i.e. denial of permission to become an HFT) were based on a number of factors. However, these factors were often based on reasons other than health such as impact on neighbours’ living conditions, noise pollution and highway safety. The weight given to the Development Plan appeared somewhat unclear with a number of inspectors disregarding policies and/or guidance documents when making decisions.

Disregarding childhood obesity

Some inspectors felt that the issue of pupils accessing HFTs and any link with childhood obesity was simply irrelevant to the case given that, in their opinion, it would only be accessible to a small number of pupils. A disregard of adherence to local policies in relation to health was evident. Some inspectors felt that the issue of population health was not deemed as being sufficient enough to warrant a dismissal:

… while the proposal’s proximity to the schools and its effect on healthy eating and the well-being of children are material considerations, I conclude that the number of pupils from these schools that would use the premises during the school day would not be significant. Consequently, in this respect the proposal would not conflict with Policy 13 of the Core Strategy. so not related to obesity or unhealthy eating. (ID2)

Although the proposal might conflict with national policies concerning the promotion of healthy lifestyles and reduction of childhood obesity, this does not justify dismissal of the appeal on these grounds. (ID7)

The reasoning behind these views was unclear.

Economics

Appellants frequently highlighted the economic benefit their business would bring to the local high street by increasing custom for other establishments and providing employment. However, economic reasons, although considered were dismissed by inspectors in favour of what they believed to be more significant issues such as highway restrictions and breach of policy:

However, neither these matters, nor the employment and career opportunities which would be created, outweigh the harm identified. I have considered all other matters raised, but they do not alter my decision. (ID 33)

Drawing these threads together, whilst there would be some economic benefit derived from the proposal this, on its own, is not sufficient to outweigh the conflict with a very recently adopted local plan policy. (ID 9)

Support of local policy and planning

Approximately 40% (n = 10) of cases were dismissed on the basis that the proposed business would violate local policy and planning. Acknowledgement of obesity and health was evident in some (n = 8) cases and this was provided as the primary reason for dismissal:

… The appeal proposal would however lead to a proliferation of takeaways in the local area, which, given their close proximity and easy walking distance to these schools, would be likely to attract custom from children and undermine the Council’s efforts in creating and developing healthy communities. (ID 36)

However, the significance of obesity given to cases was variable and it was clearly stated in others that obesity was not an adequate enough reason:

Takeaway permission denied – however ‘The effects of takeaway food on child obesity would not constitute a reason to dismiss the appeal’. (ID 49)

In some cases, childhood obesity was cited as ‘adding weight’ to the dismissal and not a prioritising or deciding factor:

The objective of the SPD, to establish healthy eating habits and reduce childhood obesity, is an important one and whilst not a main issue, the proposal’s failure to comply with it adds weight to my decision. (ID 8)

Inspectors also recognised that, although appellants claimed that they would make adjustments to their business, for example, making pledges to create a healthier menu that there would be no way of enforcing and/or monitoring this:

The appellant states that it is his intention to offer a healthy alternative to the existing takeaways in the area. However, I agree with the Council that this is not a factor that can be controlled. I therefore conclude that the proposed change of use would undermine the Council’s objectives to improve community health. (ID 38)

Discussion

In a number of cases presented, it is clear that the NPPF and local policy guidance were influential in the inspectors’ decision-making and indeed, in some cases, a determining factor.

Yet, the over-riding finding was that inspectors considered that they had insufficient evidence concerning HFTs and health impacts to base their decision-making on, though why the evidence was found wanting was generally unclear. It is worth considering the issue of evidence from the inspector’s perspective. Although the kind of evidence presented at each appeal follows a similar pattern, its quality and quantity may vary considerably from case to case. Inspectors place a great deal of weight on robust evidence at local level; the availability of any such evidence to an individual local authority varies considerably. Generally, for example, much health evidence is produced at the national level and its applicability to specific cases limited. Therefore, a clearer framework for interpreting macro-national level data at the micro-local level would be highly desirable.

While it is appreciated that inspectors have an extremely difficult job balancing a vast array of issues in appeal cases, the general lack of engagement with health issues in decision-making was concerning. However, this does mirror previous work exploring planners and public health practitioners’ views on addressing obesity.28 This research identified a range of barriers that prevent planners from engaging with obesity prevention. These include having an insufficient understanding of the causes of obesity and the importance of addressing obesity through multiagency approaches. It was concluded that planners could and should be better engaged in the obesity prevention agenda;28 this necessitates proper resourcing, and in many LPAs, services have faced severe cutbacks and are struggling to meet even statutory requirements.

One key issue that inspectors could easily be aware of is that evidence suggests individuals do not always make or are not always able to make informed healthy food choices and that those who reside within the vicinity of a significant number of HFTs are more likely to consume them on a frequent basis than those who do not.12 For reasons that are not entirely understood, poorer, less educated individuals are more susceptible to consume to excessive levels, which in turn may exacerbate health inequalities.12,29 It would also be helpful if inspectors were aware of the lengths that some individuals, particularly older children will do to access HFTs. Moreover, there is no evidence that greater choice of HFTs is in any way beneficial to local communities. The less establishments there are will help control access and, in turn, the potential detrimental effects on health. It might be suggested that such key points could be covered in a relatively concise briefing note, for example.

There is also an issue of transparency in decision-making. No doubt, the inspectors would argue that all decisions were based on professional opinion, drawing on the evidence presented, and making a judgement on the weight to give each aspect of the case. However, in trying to undertake a dispassionate review based on the paperwork alone, it was often quite difficult to understand the inspector’s reasoning. For example, in some cases, completely un-evidenced (and even factually incorrect) statements made by appellants were given credence. While in other cases LPA guidance and policy, which would have at least undergone scrutiny in its preparation, was dismissed as unimportant. This is clearly an issue which is beyond the immediate topic of A5 use and runs to the heart of appeal decision-making. However, decisions in A5 appeal have the potential to adversely impact the health and wellbeing of individuals and communities. This would not be the case with every type of planning appeal. It could be argued that, in such cases, only those matters that have robust evidence to support them should be taken into account in reaching a decision to uphold or dismiss an appeal. The onus, therefore, on all parties, should be to provide compelling evidence to support their case. It would also be useful to local authorities in particular to receive more direction in cases where their evidence base falls short, to assist them in preparing cases in the future.

The issue of planning conditions and opening hours is another topic that addresses matters beyond A5 use, given that other types of establishment may have open hours imposed on them. We have no evidence that planning conditions to control A5 premises are ineffectual. We are also unaware of any research on this topic. However, there is clearly a concern among planning practitioners that controlling opening hours through enforcement is not necessarily a straightforward task. One practitioner also pointed out that small independent HFTs often change hands on a regular basis and that enforcement officers may well find themselves constantly playing catch-up as to who they were taking enforcement action against.

That childhood obesity in particular is a topic of extraordinary importance can surely not be questioned. The damage to young developing bodies can be significant and it is proven that health problems can track through into later life, even if individuals subsequently lose weight.30 Childhood obesity is a societal problem and it is everyone’s responsibility to do their part to address it.31 Planning is no exception and that planning has a role to play in obesity prevention is long established.4 However, it must be acknowledged that this is a relatively new role for planning and it is a challenging one.28 Elements that are coming in to play, such as the use-classes system, were devised in very different times, shaped by different sets of dynamics. If the challenge of delivering healthy communities is promoted by the NPPF, some aspects of the planning system could require major overhaul, but these changes may take considerable time. Meanwhile, it is beholden on all involved to try and make the best of the current situation, and within this we include academia, especially in provision of an appropriate and timely evidence base. In local authorities, it is suggested that programmes such as the National Health Service (NHS) Healthy New Towns approaches32 be used to provide insight in helping to identify policy drivers which could strengthen existing planning policies. A Health in All Policies approach as advocated by World Health Organization (WHO) and the UK Local Government Association should be adopted to ensure that all decisions made consider all relevant health implications.33,34 In addition, this will encourage an all-encompassing move within planning and health from a silo to a system-wide approach.

In terms of appeals, local authorities with the most robust, locally informed evidence bases have the greatest chance of success in having their decisions upheld. In England, local authorities are more likely to have planning policies around health and HFTs if they have a high number of HFTs and higher rates of childhood obesity.35

This is a rapidly evolving field of health/built environment evidence. All planners accredited by the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) must complete 50 h of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) during a 2-year period. Reviewing a 4-month period of RTPI-promoted CPD (May–October 2019) revealed that among the many and varied events, only one addressed health issues;36 though it should be pointed out that the campaigning organisation Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA) has been far more proactive in this regard.37 In addition, there are local authorities who have shown that using policy guidance in support of cases is resulting in positive outcomes. For example, in Gateshead (North East of England), a recent (March 2020) appeal for a multinational fast-food outlet was dismissed based on the local SPD restriction of HFTs, with inspectorate highlighting the potential impact of such establishments in areas that already have high levels of obesity. It is important to note that there is strong proactive involvement of researchers in this region which may also be a contributing factor in addressing the issue. In adopting such approaches and learning from good practice and collaborative efforts of local authorities, the ability to harness evidence effectively in appeals decision-making can be achieved.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations relating to this research which must be considered. First, information obtained from the database Appeals Finder was collected from 2010 and therefore additional and potentially relevant data which may have arisen in cases prior to this will not have been captured. Similarly, only information entered into the database Appeals Finder was considered, yet there is a chance that data could have been omitted for various unknown reasons.

Although various attempts were made by the authors to speak to PINS, this proved to be unsuccessful. In order to provide context and added depth to the data derived from the appeals finder, it would have been preferable to discuss individual cases with PINS. This would have resulted in a better understanding of decisions and highlighted any possible barriers and/or facilitators that they may have encountered. This is one of the key limitations of this research and it is suggested that future work includes working closely with local authorities and, in particular, PINS to understand this process.

Finally, an issue that was brought to the attention of the research team by planning practitioners is the blurring between use-class orders, which may undermine policy attempts to control unhealthy food access. For example, many of the large multinational fast-food chains operate premises as A3 restaurants and cafes, by providing seating areas, even when from a business point of view these are largely unwarranted. Planning processes seek to root our ‘back door’ A5 applications, but the distinction is not always clear. Similarly, A1 convenience stores, bakers and so on may sell a small selection of hot takeaway food products, again blurring the A1/A5 boundary. These are significant challenges and will be addressed in future work.

Conclusion

The importance of health and, in particular, the threat of obesity and associated complications needs to be included and made mandatory within all planning and policy documentation. All material considerations need to be taken into account and assessed on a case-by-case basis, while remaining mindful of the consequences on population health. Decisions need to be evidence based and official government planning policy and guidance are easily accessible and available to help steer judgements on any decisions that may impact health. Importantly, consideration of all evidence needs to be weighed up collectively rather than being based on mere assumptions or opinion, and health in all policies should be consistently encouraged and prioritised.

Acknowledgments

This research did not require ethical approval as the data analysed were obtained from the appeals database finder which is freely accessible information: http://www.gov.uk/appeal-planning-inspectorate

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors contributed equally to this work.

Conflict of Interest: The author(s) declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Teesside University Seedcorn funding.

ORCID iDs: Claire L O’Malley  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5004-4568

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5004-4568

Tim G Townshend  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6080-2238

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6080-2238

Contributor Information

CL O’Malley, School of Health & Life Sciences, Teesside University, Middlesbrough, UK; Fuse, UKCRC Centre for Translational Research in Public Health, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

AA Lake, School of Health & Life Sciences, Teesside University, Middlesbrough, TS1 3BA, UK; Fuse, UKCRC Centre for Translational Research in Public Health, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

TG Townshend, School of Architecture, Planning & Landscape, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; Fuse, UKCRC Centre for Translational Research in Public Health, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

HJ Moore, School of Social Sciences, Humanities & Law, Teesside University, Middlesbrough, UK; Fuse, UKCRC Centre for Translational Research in Public Health, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

References

- 1.Ross AC, Chang M. Reuniting health with planning’ healthier homes, healthier communities. London: Town and Country Planning Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government. National Planning Policy Framework. February2019. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/810197/NPPF_Feb_2019_revised.pdf

- 3.Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government. National planning policy framework. London: Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.UK Government’s Foresight Programme. Tackling Obesities: Future Choices – Project Report, 2007. Available online at: https://www.safefood.eu/SafeFood/media/SafeFoodLibrary/Documents/Professional/All-island%20Obesity%20Action%20Forum/foresight-report-full_1.pdf

- 5.Lake A, Townshend T. Obesogenic environments: exploring the built and food environments. J R Soc Promot Health 2006;126(6):262–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Public Health England. Using the planning system to promote healthy weight environments Guidance and supplementary planning document template for local authority public health and planning teams. London: Department of Health and Social Care; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lake AA, Townshend TG, Burgoine T. Obesogenic environments in public health nutrition. In: Butriss J, Welch A, Kearney J, et al. (eds). Public health nutrition: The nutrition society textbook series. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2017, pp. 327–338. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lake AA. Neighbourhood food environments: food choice, foodscapes and planning for health. Proc Nutr Soc 2018;77(3):239–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Townshend TG, Lake AA. Relationships between ‘Wellness Centre’ use, the surrounding built environment and obesogenic behaviours, Sunderland, UK. J Urban Des 2011;16(3):351–67. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dover RVH, Lambert EV. ‘Choice Set’ for health behavior in choice-constrained settings to frame research and inform policy: examples of food consumption, obesity and food security. Int J Equity Health 2016;15:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janssen HG, Davies IG, Richardson LD, et al. Determinants of takeaway and fast food consumption: a narrative review. Nutr Res Rev 2018;31(1):16–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgoine T, Forouhi NG, Griffin SJ, et al. Associations between exposure to takeaway food outlets, takeaway food consumption, and body weight in Cambridgeshire, UK: population based, cross sectional study. BMJ 2014;348:g1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mason KE, Pearce N, Cummins S. Associations between fast food and physical activity environments and adiposity in mid-life: cross-sectional, observational evidence from UK Biobank. Lancet Public Health 2018;3(1):e24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.London Borough of Brent. Takeaway Use Among School Students, 2014. Available online at: https://www.brent.gov.uk/media/16403699/d26-takeaway-use-brent-school-students.pdf

- 15.Tyrrell RL, Greenhalgh F, Hodgson S, et al. Food environments of young people: linking individual behaviour to environmental context. J Public Health 2016;39(1):95–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyrrell RL, Townshend TG, Adamson AJ, et al. ‘I’m not trusted in the kitchen’: food environments and food behaviours of young people attending school and college. J Public Health 2016;38(2):289–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caspi C, Sorensen G, Subramanian S, et al. The local food environment and diet: a systematic review. Health Place 2012;18(5):1172–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cobb LK, Appel LJ, Franco M, et al. The relationship of the local food environment with obesity: a systematic review of methods, study quality, and results. Obesity 2015;23(7):1331–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lachat C, Nago E, Verstraeten R, et al. Eating out of home and its association with dietary intake: a systematic review of the evidence. Obes Rev 2012;13(4):329–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maguire ER, Burgoine T, Monsivais P. Area deprivation and the food environment over time: a repeated cross-sectional study on takeaway outlet density and supermarket presence in Norfolk, UK, 1990-2008. Health Place 2015;33:142–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macdonald L, Cummins S, Macintyre S. Neighbourhood fast food environment and area deprivation-substitution or concentration? Appetite 2007;49:251–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burgoine T, Forouhi NG, Griffin SJ, et al. Does neighborhood fast-food outlet exposure amplify inequalities in diet and obesity? A cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;103(6):1540–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams J, Goffe L, Brown T, et al. Frequency and socio-demographic correlates of eating meals out and take-away meals at home: cross-sectional analysis of the UK national diet and nutrition survey, waves 1–4 (2008–12). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015;12:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lake AA, Townshend TG, Burgoine T. Obesogenic neighbourhood food environments. In: Butriss J, Welch A, Kearney J, et al. (eds). Public health nutrition. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2017, pp. 327–38. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keeble M, Burgoine T, White M, et al. How does local government use the planning system to regulate hot food takeaway outlets? A census of current practice in England using document review. Health Place 2019;57:171–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brighton and Hove Local Authority. Hot-food Takeaways Near Schools: An Impact Study on Takeaways Near Secondary Schools in Brighton and Hove 2011. Available online at: https://www.brighton-hove.gov.uk/sites/brighton-hove.gov.uk/files/downloads/ldf/Healthy_eating_Study-25-01-12.pdf

- 28.Lake AA, Henderson EJ, Townshend TG. Exploring planners’ and public health practitioners’ views on addressing obesity: lessons from local government in England. Cit Health 2017;1(2):185–93. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burgoine T, Monsivais P. Characterising food environment exposure at home, at work, and along commuting journeys using data on adults in the UK. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Craigie AM, Lake AA, Kelly SA, et al. Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: a systematic review. Maturitas 2011;70(3):266–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.HM Government. Childhood obesity: A plan for action. London: HM Government; 2016, p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- 32.NHS England. Healthy New Towns, 2015. Available online at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/innovation/healthy-new-towns/

- 33.Local Government Association. Health in All Policies: A Manual for Local Government, 2016. Available online at: https://www.local.gov.uk/health-all-policies-manual-local-government

- 34.World Health Organisation. Health in All Policies Framework for Country Action, 2014. Available online at: https://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/140120HPRHiAPFramework.pdf?ua=1.%20

- 35.Keeble M, Adams J, White M, et al. Correlates of English local government use of the planning system to regulate hot food takeaway outlets: a cross-sectional analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2019;16(1):127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Royal Town and Planning Institute. CPD Requirements, 2019. Available online at: https://www.rtpi.org.uk/education-and-careers/cpd-for-rtpi-members/cpd-requirements/

- 37.Town and County Planning Association. The State of the Union: Reuniting Health with Planning in Promoting Healthy Communities, 2019. Available online at: https://www.tcpa.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=cb4a5270-475e-42d3-bc72-d912563d4084